Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Preparation of gold nanoparticles

2.3. Preparation of the SERS substrates

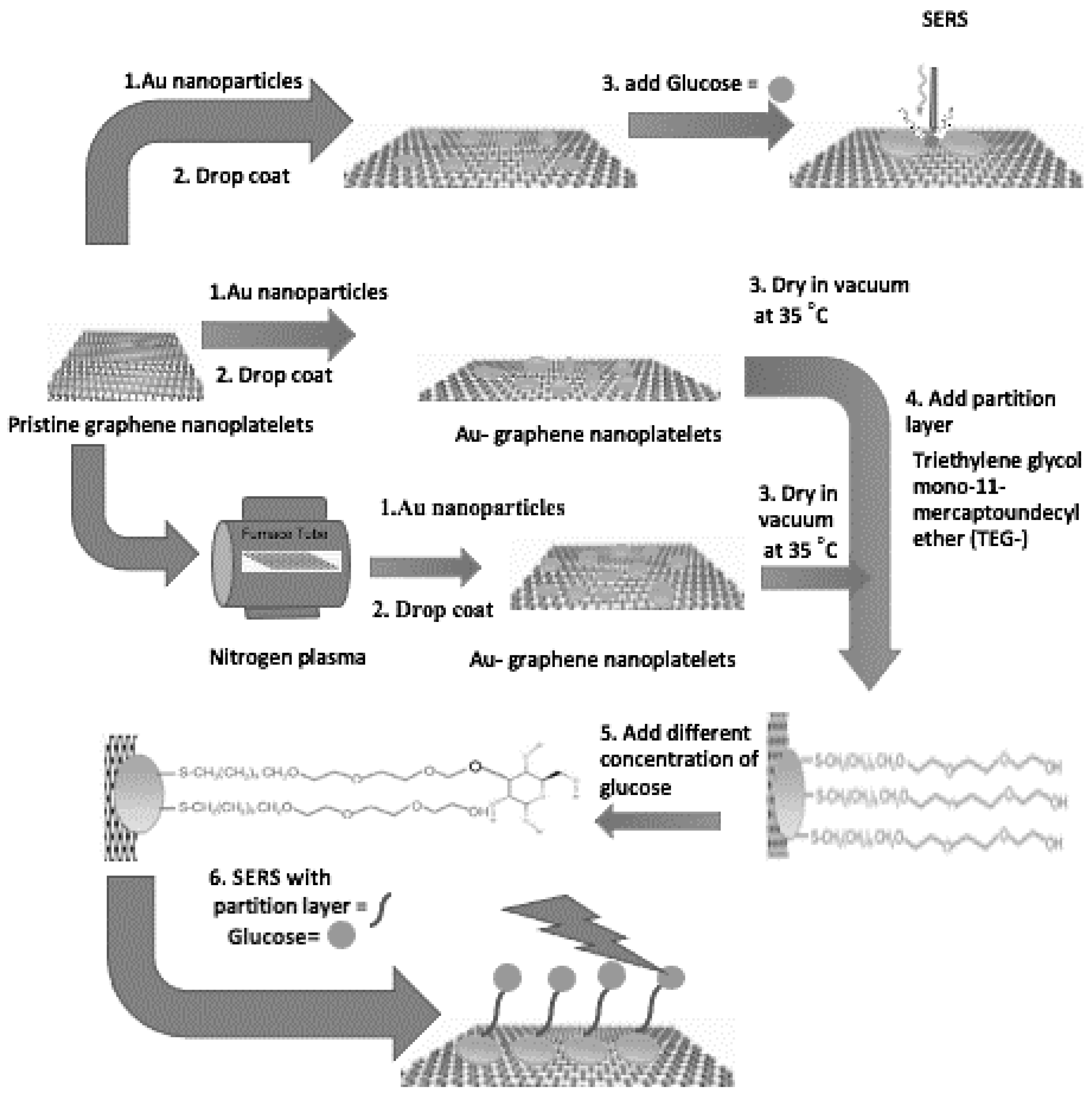

2.3.1. GNPs without partition layer

2.3.2. GNPs with partition layer

2.3.3. GNPs modified by radio frequency plasma exposure

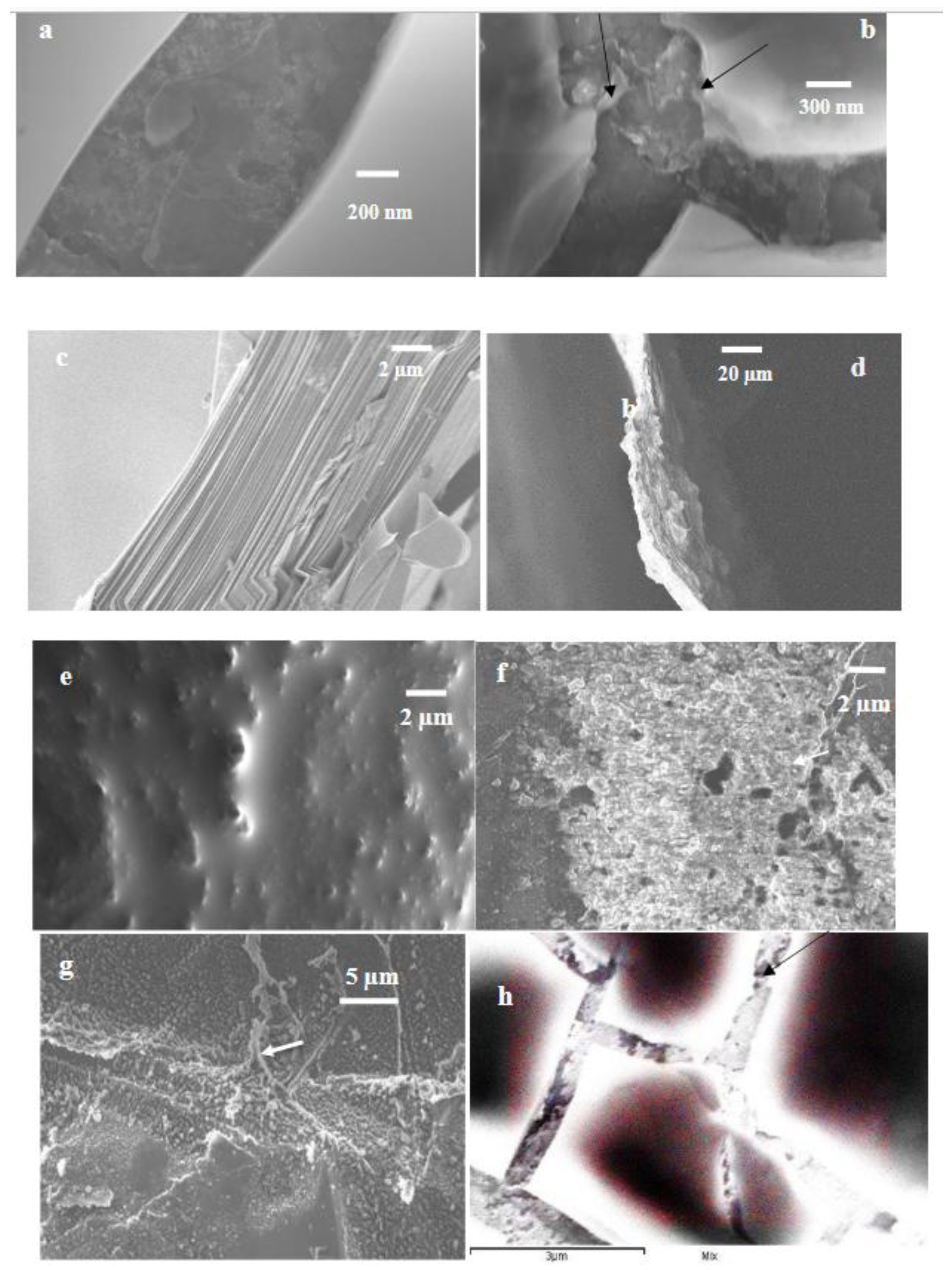

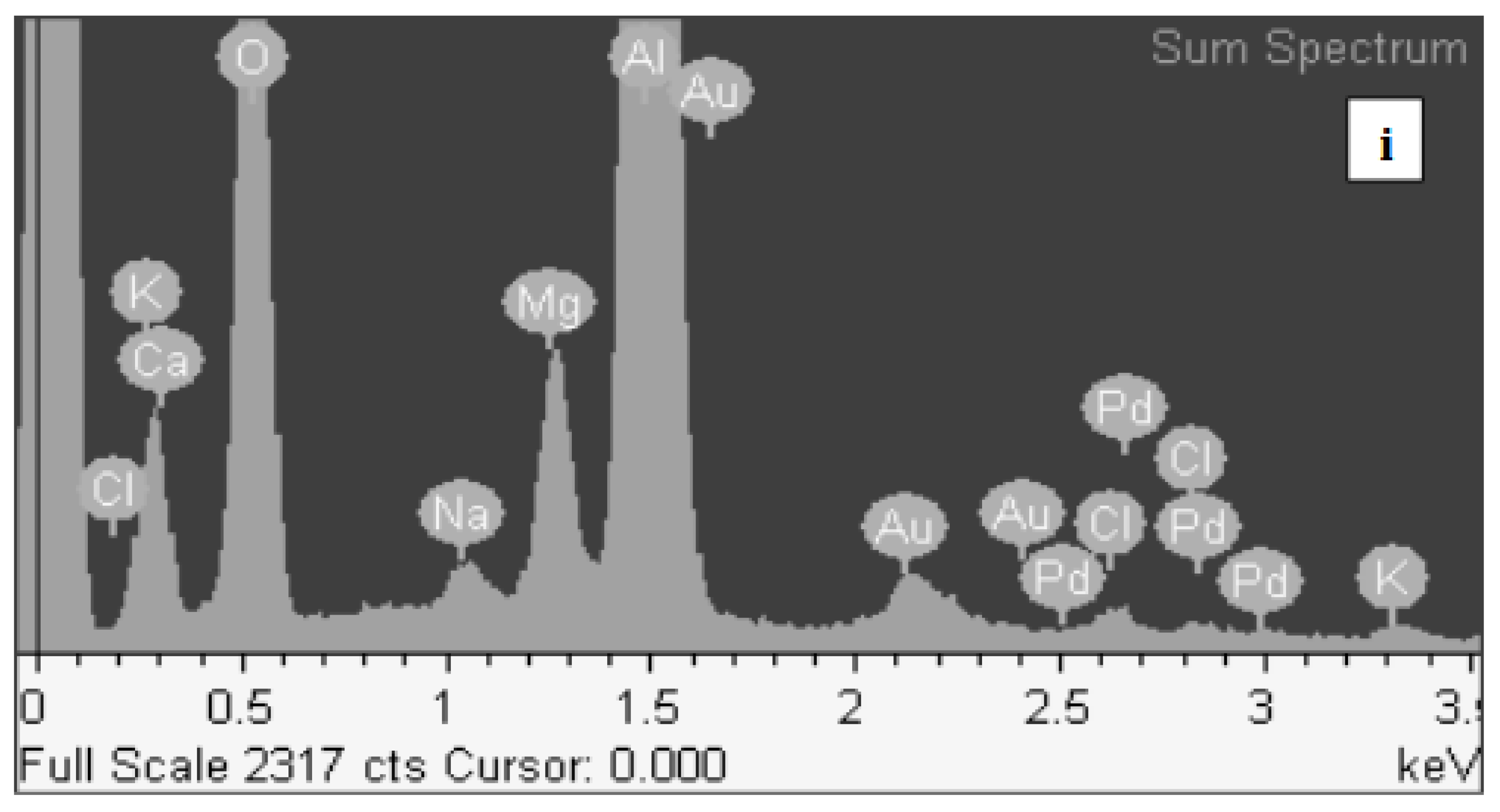

2.4. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

2.5. Raman spectroscopy

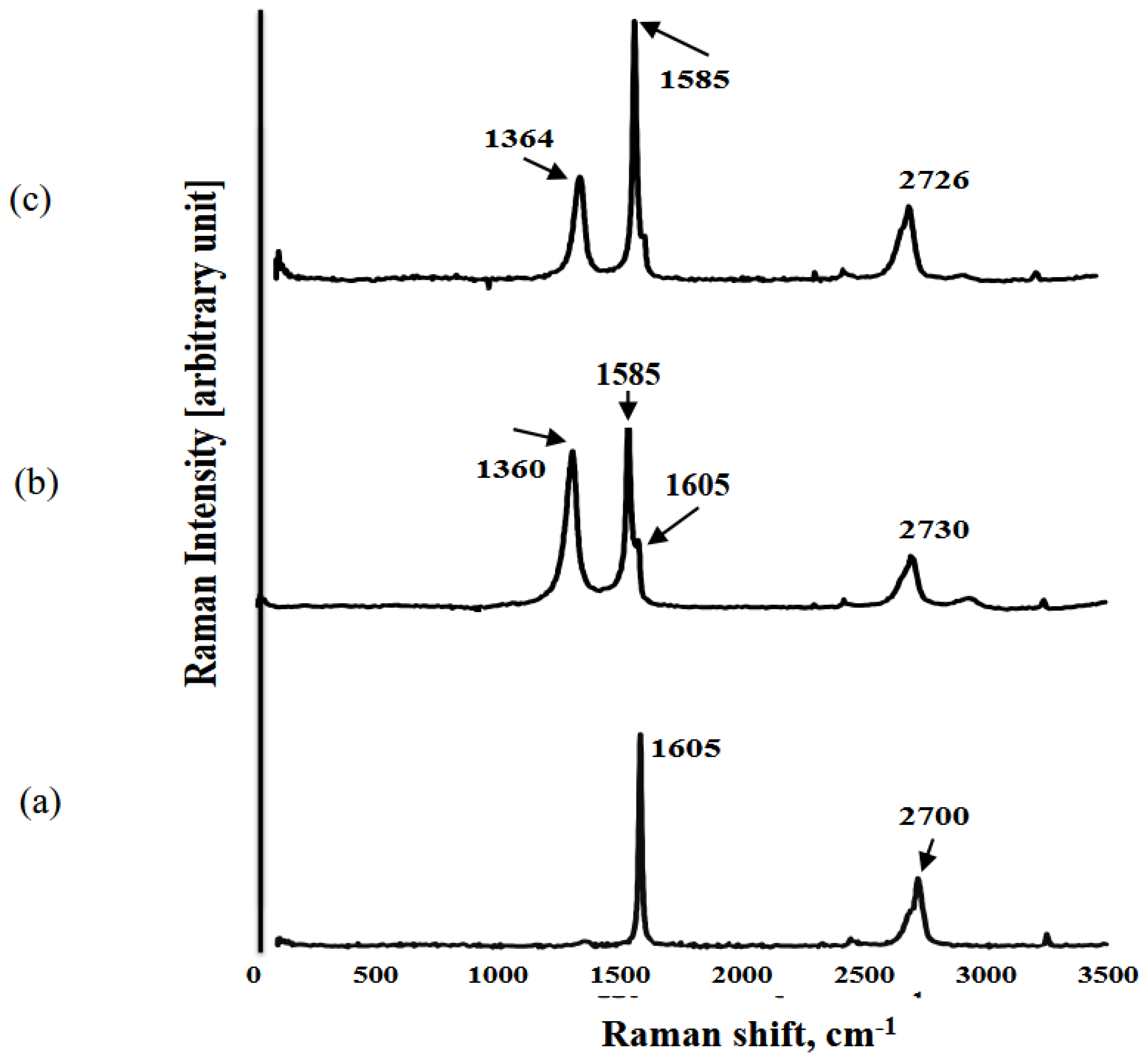

3. Results and discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Cialla, A. März, R. Böhme, F. Theil, K. Weber, M. Schmitt and J. Popp, Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 403, 27-54 (2012). [CrossRef]

- S. Schlücker, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 53, 4756-4795 (2014). [CrossRef]

- C.M. MacLaughlin, N. Mullaithilaga, G. Yang, S.Y. Ip, C. Wang and G.C. Walker, Langmuir, 29, 1908-1919 (2013). [CrossRef]

- C. Hrelescu, T.K. Sau, A.L. Rogach, F. Jäckel and J. Feldmann, Applied Physics Letters, 94 (2009). [CrossRef]

- K. Hering, D. Cialla, K. Ackermann, T. Dörfer, R. Möller, H. Schneidewind, R. Mattheis, W. Fritzsche, P. Rösch and J. Popp, Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry, 390, 113-124 (2008). [CrossRef]

- H. Yuan, A.M. Fales, C.G. Khoury, J. Liu and T. Vo-Dinh, JRS., 44, 234-239 (2013).

- C. Hrelescu, T.K. Sau, A.L. Rogach, F. Jäckel and J. Feldmann, Appl. Phys. Lett., 94, 153113 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Y. Hu, H. Cheng, X. Zhao, J. Wu, F. Muhammad, S. Lin, J. He, L. Zhou, C. Zhang and Y. Deng, ACS nano, 11, 5558-5566 (2017). [CrossRef]

- S. Boca, D. Rugina, A. Pintea, N. Leopold and S. Astilean, J Nanotechnology, 2012 (2012). [CrossRef]

- M.M. Kemp, A. Kumar, S. Mousa, T.-J. Park, P. Ajayan, N. Kubotera, S.A. Mousa and R.J. Linhardt, Biomacromolecules, 10, 589-595 (2009). [CrossRef]

- N. Duan, M. Shen, S. Qi, W. Wang, S. Wu and Z. Wang, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 230, 118103 (2020). [CrossRef]

- X. Su, J. Zhang, L. Sun, T.-W. Koo, S. Chan, N. Sundararajan, M. Yamakawa and A.A. Berlin, Nano letters, 5, 49-54 (2005). [CrossRef]

- L.A. Wali, K.K. Hasan and A.M. Alwan, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 206, 31-36 (2019). [CrossRef]

- S.P. Mulvaney, M.D. Musick, C.D. Keating and M.J. Natan, Langmuir, 19, 4784-4790 (2003). [CrossRef]

- T. Wang, X. Hu and S. Dong, J. Phys. Chem. B, 110, 16930-16936 (2006). [CrossRef]

- R. Liu, S. Li and J.-F. Liu, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. (2017). [CrossRef]

- B. Kuestner, M. Gellner, M. Schuetz, F. Schoeppler, A. Marx, P. Stroebel, P. Adam, C. Schmuck and S. Schluecker, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 48, 1950-1953 (2009). [CrossRef]

- X. Qian, X.-H. Peng, D.O. Ansari, Q. Yin-Goen, G.Z. Chen, D.M. Shin, L. Yang, A.N. Young, M.D. Wang and S. Nie, Nat. Biotechnol., 26, 83 (2008). [CrossRef]

- S. Suvarna, U. Das, K. Sunil, S. Mishra, M. Sudarshan, K.D. Saha, S. Dey, A. Chakraborty and Y. Narayana, PloS one, 12, e0178202 (2017). [CrossRef]

- S. Pang, (2016).

- D.A. Stuart, C.R. Yonzon, X. Zhang, O. Lyandres, N.C. Shah, M.R. Glucksberg, J.T. Walsh and R.P. Van Duyne, Anal. Chem., 77, 4013-4019 (2005). [CrossRef]

- D.A. Stuart, J.M. Yuen, N. Shah, O. Lyandres, C.R. Yonzon, M.R. Glucksberg, J.T. Walsh and R.P. Van Duyne, Analytical chemistry, 78, 7211-7215 (2006). [CrossRef]

- O. Lyandres, N.C. Shah, C.R. Yonzon, J.T. Walsh, M.R. Glucksberg and R.P. Van Duyne, Analytical chemistry, 77, 6134-6139 (2005). [CrossRef]

- C.R. Yonzon, C.L. Haynes, X. Zhang, J.T. Walsh and R.P. Van Duyne, Analytical Chemistry, 76, 78-85 (2004). [CrossRef]

- C.S. Levin, S.W. Bishnoi, N.K. Grady and N.J. Halas, Anal. Chem., 78, 3277-3281 (2006). [CrossRef]

- S. Yadav, M.A. Sadique, P. Ranjan, N. Kumar, A. Singhal, A.K. Srivastava and R. Khan, ACS Applied Bio Materials, 4, 2974-2995 (2021). [CrossRef]

- C. Awada, M.M.B. Abdullah, H. Traboulsi, C. Dab and A. Alshoaibi, Sensors, 21, 4617 (2021). [CrossRef]

- X. Ling, L. Xie, Y. Fang, H. Xu, H. Zhang, J. Kong, M.S. Dresselhaus, J. Zhang and Z. Liu, Nano letters, 10, 553-561 (2010). [CrossRef]

- S. Xu, S. Jiang, J. Wang, J. Wei, W. Yue and Y. Ma, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 222, 1175-1183 (2016). [CrossRef]

- W. Xu, J. Xiao, Y. Chen, Y. Chen, X. Ling and J. Zhang, Advanced Materials, 25, 928-933 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Y. Du, Y. Zhao, Y. Qu, C.-H. Chen, C.-M. Chen, C.-H. Chuang and Y. Zhu, Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 2, 4683-4691 (2014). [CrossRef]

- A.C. Ferrari, J.C. Meyer, V. Scardaci, C. Casiraghi, M. Lazzeri, F. Mauri, S. Piscanec, D. Jiang, K.S. Novoselov and S. Roth, Physical review letters, 97, 187401 (2006). [CrossRef]

- L.M. Malard, M.A. Pimenta, G. Dresselhaus and M.S. Dresselhaus, Physics reports, 473, 51-87 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Y.-F. Lu, S.-T. Lo, J.-C. Lin, W. Zhang, J.-Y. Lu, F.-H. Liu, C.-M. Tseng, Y.-H. Lee, C.-T. Liang and L.-J. Li, ACS nano, 7, 6522-6532 (2013). [CrossRef]

- M. Rybin, A. Pereyaslavtsev, T. Vasilieva, V. Myasnikov, I. Sokolov, A. Pavlova, E. Obraztsova, A. Khomich, V. Ralchenko and E. Obraztsova, Carbon, 96, 196-202 (2016). [CrossRef]

- A. Jilani, M.H.D. Othman, M.O. Ansari, S.Z. Hussain, A.F. Ismail, I.U. Khan and Inamuddin, Environmental chemistry letters, 16, 1301-1323 (2018). [CrossRef]

- L. Al-qarn and Z. Iqbal, European Pharmaceutical Review, 22, 23-26 (2017).

- J. Turkevich, Gold Bulletin, 18, 86-91 (1985). [CrossRef]

- G. Frens, Nature physical science, 241, 20-22 (1973). [CrossRef]

- Z.Y. E.M. Benchafia, G. Yuan, T. Chou, H. Piao, X. Wang, Z. Iqbal. Cubic gauche polymeric nitrogen under ambient conditions. Nat. Communications. 8(1) (2017) 930. [CrossRef]

- C.L. Haynes and R.P. Van Duyne, MRS Online Proceedings Library (OPL), 728, S10. 7 (2002). [CrossRef]

- L. Ascherl, T. Sick, J.T. Margraf, S.H. Lapidus, M. Calik, C. Hettstedt, K. Karaghiosoff, M. Döblinger, T. Clark and K.W. Chapman, Nature Chemistry, 8, 310-316 (2016). [CrossRef]

- S.R. Maple and A. Allerhand, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 109, 3168-3169 (1987). [CrossRef]

- Q. Hao, S.M. Morton, B. Wang, Y. Zhao, L. Jensen and T. Jun Huang, Applied physics letters, 102 (2013). [CrossRef]

- M.A. Van Huis, L.T. Kunneman, K. Overgaag, Q. Xu, G. Pandraud, H.W. Zandbergen and D. Vanmaekelbergh, Nano letters, 8, 3959-3963 (2008). [CrossRef]

- S.E. Bell and N.M. Sirimuthu, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 109, 7405-7410 (2005). [CrossRef]

- J.C. Love, L.A. Estroff, J.K. Kriebel, R.G. Nuzzo and G.M. Whitesides, Chemical reviews, 105, 1103-1170 (2005). [CrossRef]

- S. Suvarna, U. Das, S. Kc, S. Mishra, M. Sudarshan, K.D. Saha, S. Dey, A. Chakraborty and Y. Narayana, PloS one, 12, e0178202 (2017). [CrossRef]

- F. Benetti, M. Fedel, L. Minati, G. Speranza and C. Migliaresi, Journal of nanoparticle research, 15, 1-9 (2013).

- C. Munro, W. Smith, M. Garner, J. Clarkson and P. White, Langmuir, 11, 3712-3720 (1995). [CrossRef]

- F. Porcaro, Y. Miao, R. Kota, J. Haun, G. Polzonetti, C. Battocchio and E. Gratton, Langmuir, 32, 13409-13417 (2016). [CrossRef]

- J. Pulit and M. Banach, Digest Journal of Nanomaterials & Biostructures (DJNB), 8 (2013).

- G.V. Bianco, M.M. Giangregorio, M. Losurdo, A. Sacchetti, P. Capezzuto and G. Bruno, Journal of Nanomaterials, 2016, 9-9 (2016). [CrossRef]

- M.E. Ayhan and N. Emeller, Fullerenes, Nanotubes and Carbon Nanostructures, 32, 223-231 (2024).

- P.A. Pandey, G.R. Bell, J.P. Rourke, A.M. Sanchez, M.D. Elkin, B.J. Hickey and N.R. Wilson, Small, 7, 3202-3210 (2011). [CrossRef]

- L.S. Alqarni and M.D. Alghamdi, Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices, 101015 (2025). [CrossRef]

- R.A. Alzahrani, F.G. Alhaddad, E.O. Alshammari, F.S. Alsowaileh, M.D. Alghamdi, A. Modwi, N.G. Mohamed and L.S. Alqarni, Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices, 100964 (2025). [CrossRef]

- F.-r. MA, K. LIU, Y. ZHANG and S. PAN, The Journal of Light Scattering, 1, 002 (2007).

- L. Alqarni, (New Jersey Institute of Technology: 2019).

- T. Kostadinova, N. Politakos, A. Trajcheva, J. Blazevska-Gilev and R. Tomovska, Molecules, 26, 4775 (2021). [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, T. Li, Y. Han, Y. Sun, A. Zada, Y. Liu, J. Chen and A. Dang, Applied Surface Science, 654, 159513 (2024). [CrossRef]

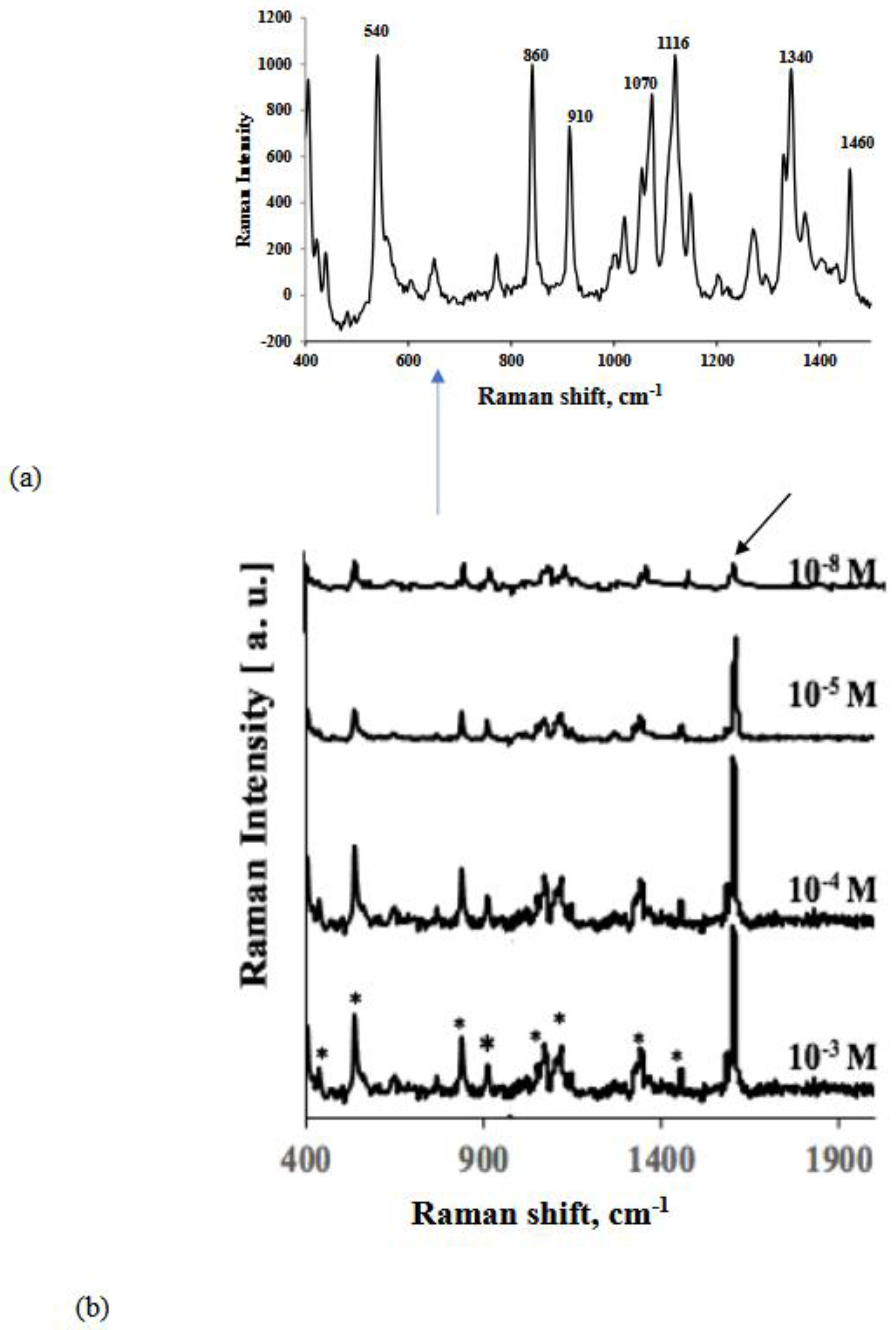

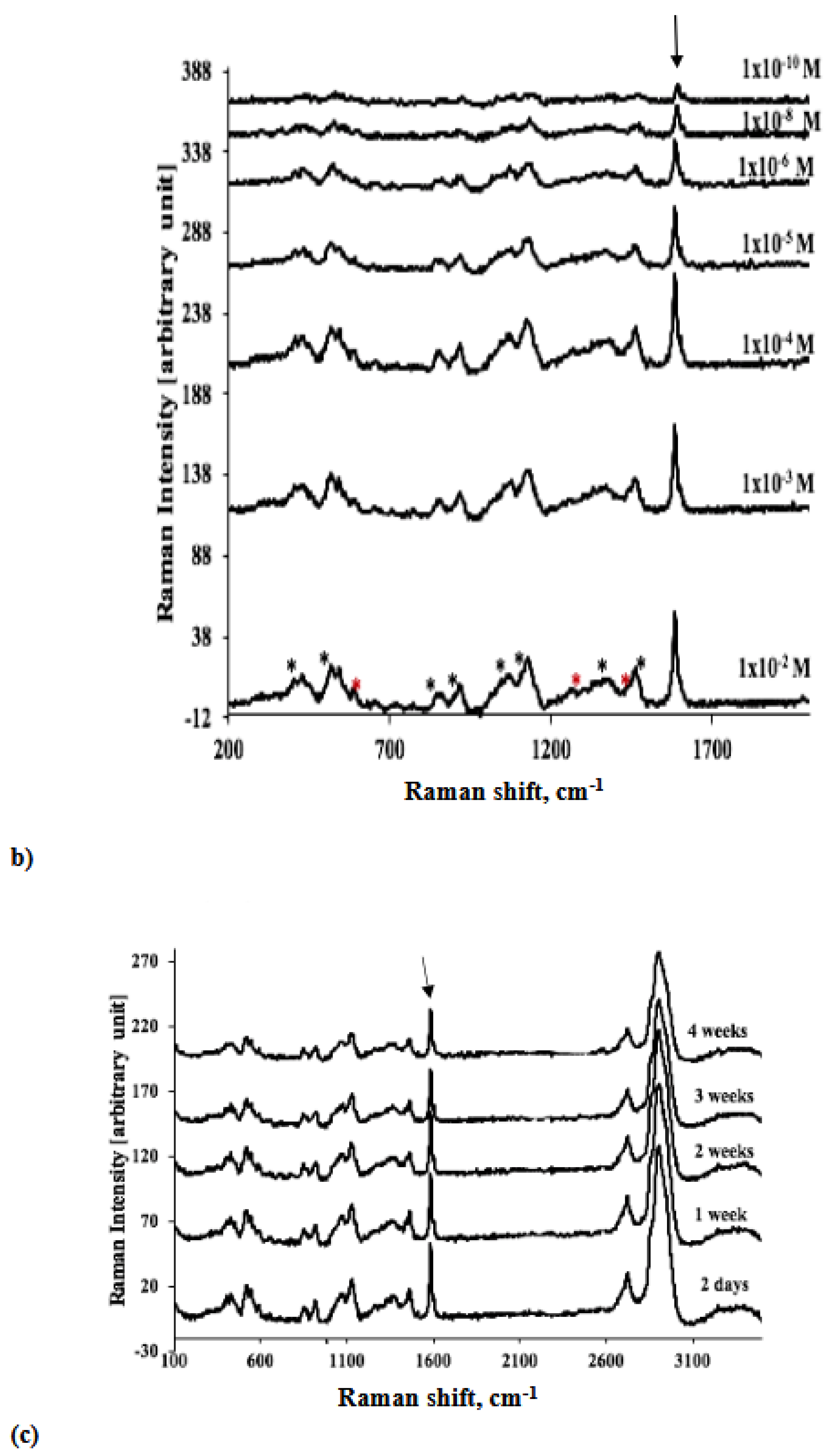

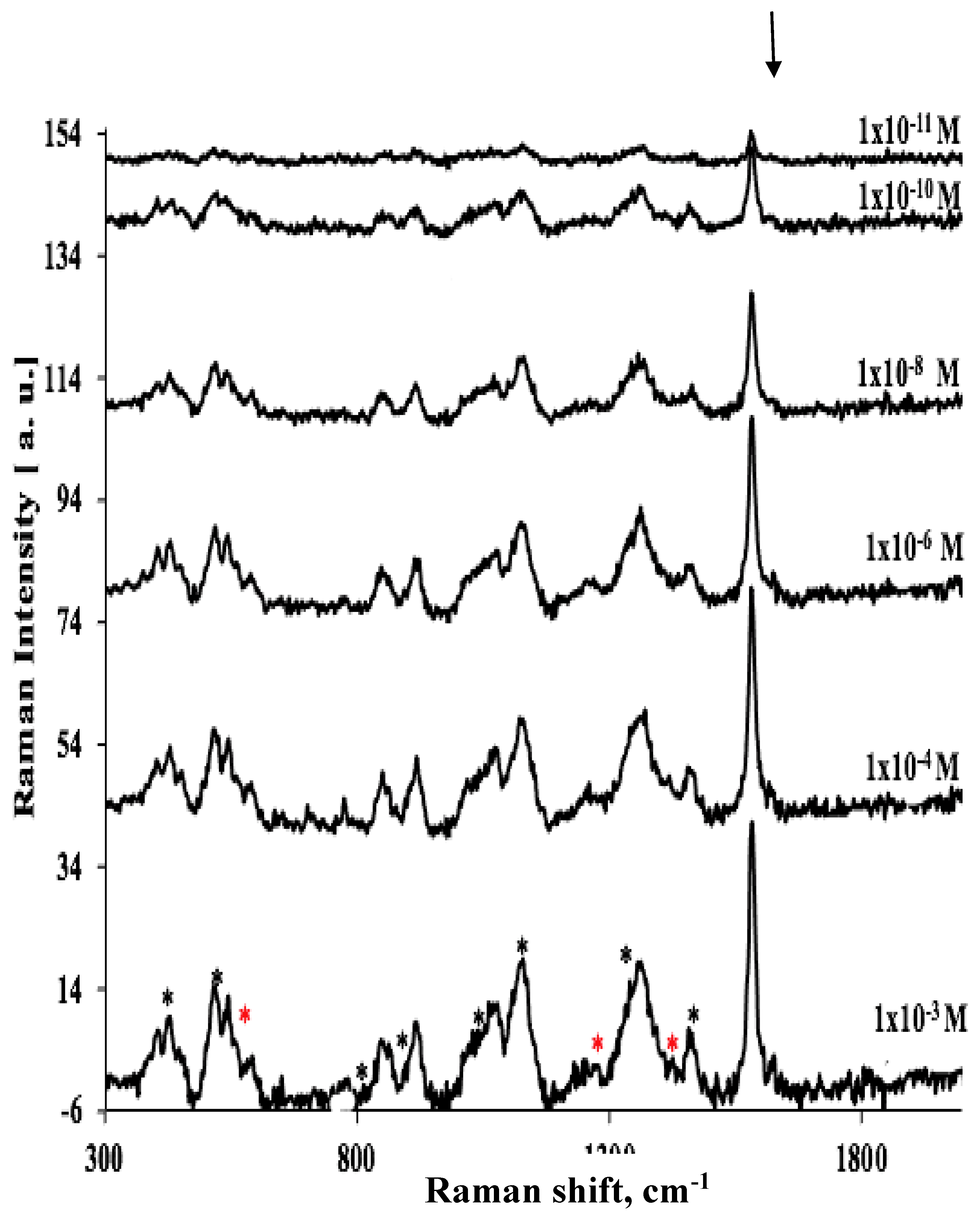

| Analyte/Substrate | Lower limit of detection | Enhancement Factors |

| Glucose/Au GNP substrate | 1x10-8 M | 2.4x109 |

| Glucose/TEG-/Au GNP substrate | 1x10-10M | 5.5x1011 |

| Glucose/TEG-/Au GNP substrate after plasma treatment | 1x10-11M | 6.4x1012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).