Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

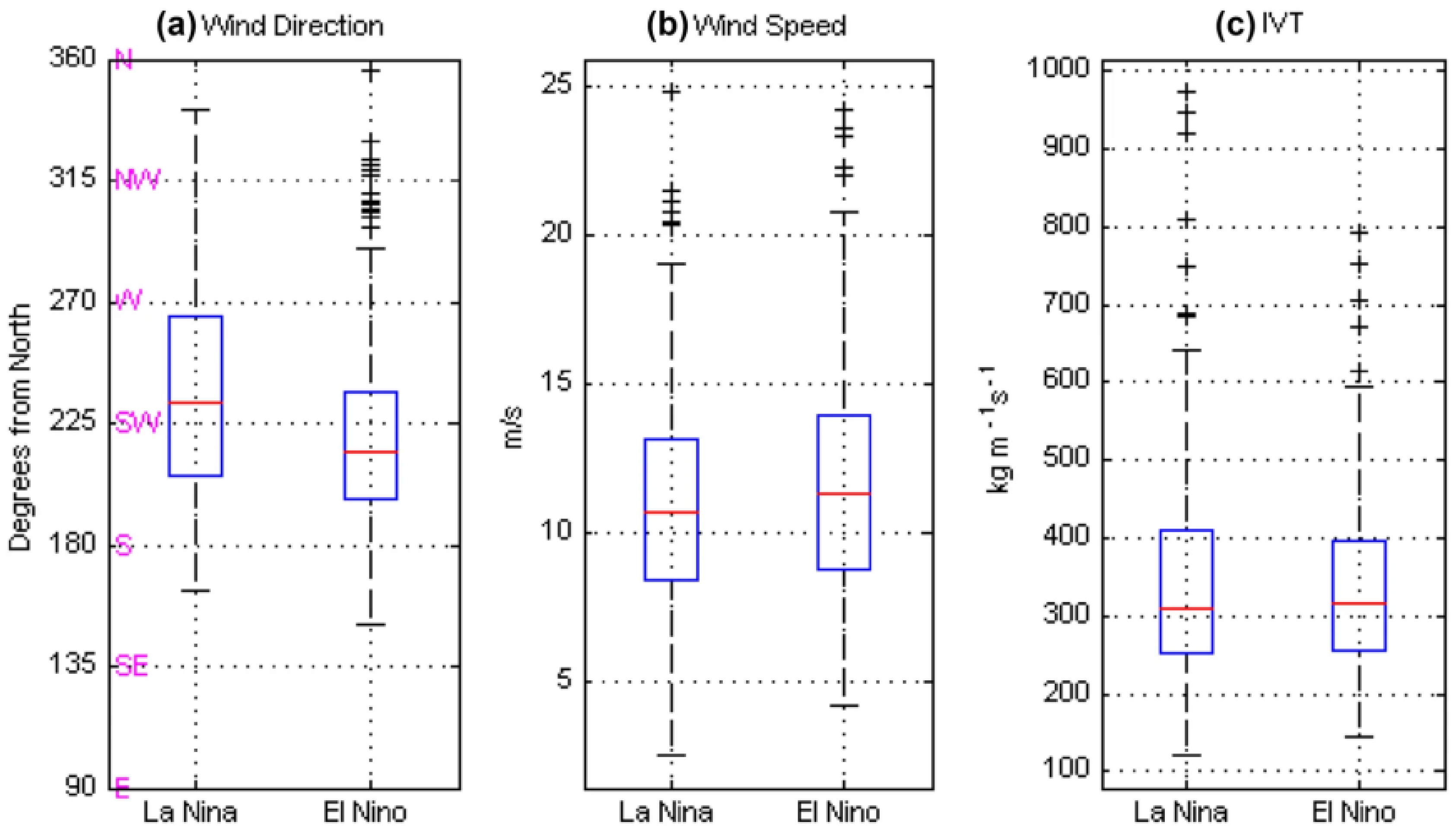

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

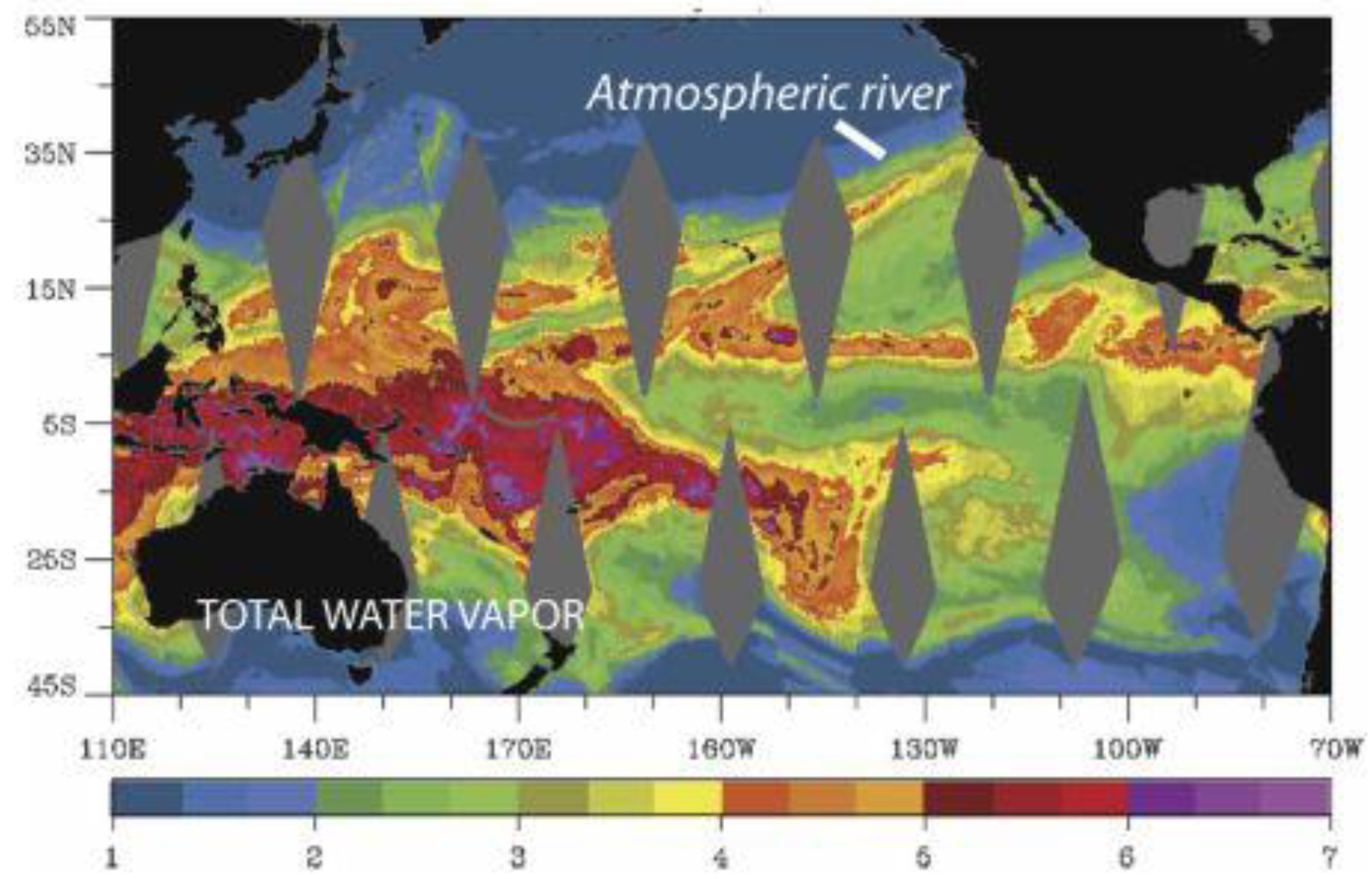

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data Samples

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Setup

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Model Formulation

2.5. Methodological Rationale

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overall Performance and Event Representation

3.2. Sensitivity of Clustering Metrics

3.3. Regional and Physical Patterns

3.4. Broader Insights and Remaining Gaps

4. Conclusions

References

- Dettinger, M.D.; Lavers, D.A.; Compo, G.P.; Gorodetskaya, I.V.; Neff, W.; Neiman, P.J.; Ramos, A.M.; Rutz, J.J.; Viale, M.; Wade, A.J.; et al. Effects of atmospheric rivers. Atmospheric rivers, 141-177.

- Anghileri, D.; Pianosi, F.; Soncini-Sessa, R. Trend detection in seasonal data: from hydrology to water resources. J. Hydrol. 2014, 511, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. , Meng, K., Wang, W., & Wang, Q. (2025, March). Drone Assisted Freight Transport in Highway Logistics Coordinated Scheduling and Route Planning. In 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT) (pp. 1254-1257). IEEE.

- Sukhdeo, R. (2024). Precipitation Variability over the Northeastern United States: Large-Scale Drivers and Large-Scale Meteorological Patterns (Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Davis).

- Guirguis, K.; Gershunov, A.; Shulgina, T.; Clemesha, R.E.S.; Ralph, F.M. Atmospheric rivers impacting Northern California and their modulation by a variable climate. Clim. Dyn. 2018, 52, 6569–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, M.; Wang, L.; Wen, Y.; Cai, H. Comparative Modulation of Immune Responses and Inflammation by n-6 and n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Oxylipin-Mediated Pathways. World J. Innov. Mod. Technol. 2024, 7, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; DeFlorio, M.J.; Sengupta, A.; Wang, J.; Castellano, C.M.; Gershunov, A.; Guirguis, K.; Slinskey, E.; Guan, B.; Monache, L.D.; et al. Seasonality and climate modes influence the temporal clustering of unique atmospheric rivers in the Western U.S. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmore, J.; Mehra, P.; Yang, J.; Linford, E. Privacy Preserving Risk Modeling Across Financial Institutions via Federated Learning with Adaptive Optimization. Front. Artif. Intell. Res. 2025, 2, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotjahn, R.; Black, R.; Leung, R.; Wehner, M.F.; Barlow, M.; Bosilovich, M.; Gershunov, A.; Gutowski, W.J.; Gyakum, J.R.; Katz, R.W.; et al. North American extreme temperature events and related large scale meteorological patterns: a review of statistical methods, dynamics, modeling, and trends. Clim. Dyn. 2015, 46, 1151–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Lu, Y.; Hou, S.; Liu, K.; Du, Y.; Huang, M.; Feng, H.; Wu, H.; Sun, X. Detecting anomalous anatomic regions in spatial transcriptomics with STANDS. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna-Niño, R.; Gershunov, A.; Ralph, F.M.; Weyant, A.; Guirguis, K.; DeFlorio, M.J.; Cayan, D.R.; Williams, A.P. Heresy in ENSO teleconnections: atmospheric rivers as disruptors of canonical seasonal precipitation anomalies in the Southwestern US. Clim. Dyn. 2025, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.S.; Zeff, H.B.; Herman, J.D. Adaptation of multiobjective reservoir operations to snowpack decline in the WESTERN United States. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chakrapani, V. Environmental Factors Controlling the Electronic Properties and Oxidative Activities of Birnessite Minerals. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2023, 7, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Niño, R.; Gershunov, A.; Ralph, F.M.; Weyant, A.; Guirguis, K.; DeFlorio, M.J.; Cayan, D.R.; Williams, A.P. Heresy in ENSO teleconnections: atmospheric rivers as disruptors of canonical seasonal precipitation anomalies in the Southwestern US. Clim. Dyn. 2025, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Thakur, S.; Adhikary, N.C. Influence of climatic indices (AMO, PDO, and ENSO) and temperature on rainfall in the Northeast Region of India. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melsen, L.A.; Puy, A.; Torfs, P.J.J.F.; Saltelli, A. The rise of the Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency in hydrology. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2025, 70, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teale, N.; Robinson, D.A. Patterns of water vapor transport in the eastern United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 2020, 21, 2123–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.D.; Scarf, D. Spacing repetitions over long timescales: a review and a reconsolidation explanation. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 962–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuel, A.; Martius, O. Weather persistence on sub-seasonal to seasonal timescales: a methodological review. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2023, 14, 955–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, V.; Esau, I. Seasonal and spatial characteristics of urban heat islands (UHIs) in northern West Siberian cities. Remote. Sens. 2017, 9, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).