1. Introduction

Low-level clouds play a vital role in regulating Earth’s weather, climate, and surface energy balance. Their base height, CBH, is a critical parameter with wide-ranging applications in agriculture, wildfire risk management, aviation, and renewable energy. Accurate CBH measurements support decisions such as crop irrigation scheduling, pesticide application, frost protection, and fire danger forecasting, while also enhancing flight safety and solar power efficiency. Beyond terrestrial uses, shadow-based CBH estimation techniques have been successfully extended to planetary science such as retrieving the heights of dust storms and cloud layers on Mars, and even towering convective clouds on Jupiter, where JunoCam imagery revealed three-dimensional structures through their shadows [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. This demonstrates the method’s versatility and value across both Earth and extraterrestrial environments.

By influencing light, temperature, and near-surface humidity, low clouds affect plant growth, soil moisture, and microclimates, making them essential to both agriculture and ecosystems. These factors impact photosynthesis, transpiration, and soil moisture retention. Monitoring and understanding CBH can therefore help optimize crop planning, yield production, and forest productivity. Farmers and agribusinesses use CBH data to schedule irrigation, spraying, and frost protection measures, thus optimizing yields and reducing losses. In addition, surface temperature, humidity and atmospheric stability are modulated by these low clouds which are key parameters in fire danger indices as well. These cloud layers can suppress or enhance fire activity. Historically, they shaded vegetation and helped maintain higher fuel moisture levels; their present disappearance contributes to drier fuels and elevated fire risk [

6]. In aviation, cloud base requirements vary with airport scale and operational capacity. Smaller regional airports often require higher CBH to maintain safe visual flight operations, whereas larger international airports can operate with lower CBH due to controlled airspace procedures and advanced instrument landing systems [

7,

8,

9]. More reliable cloud data that aviation meteorologists and pilots can readily assess are therefore critical to support safe flight decisions.

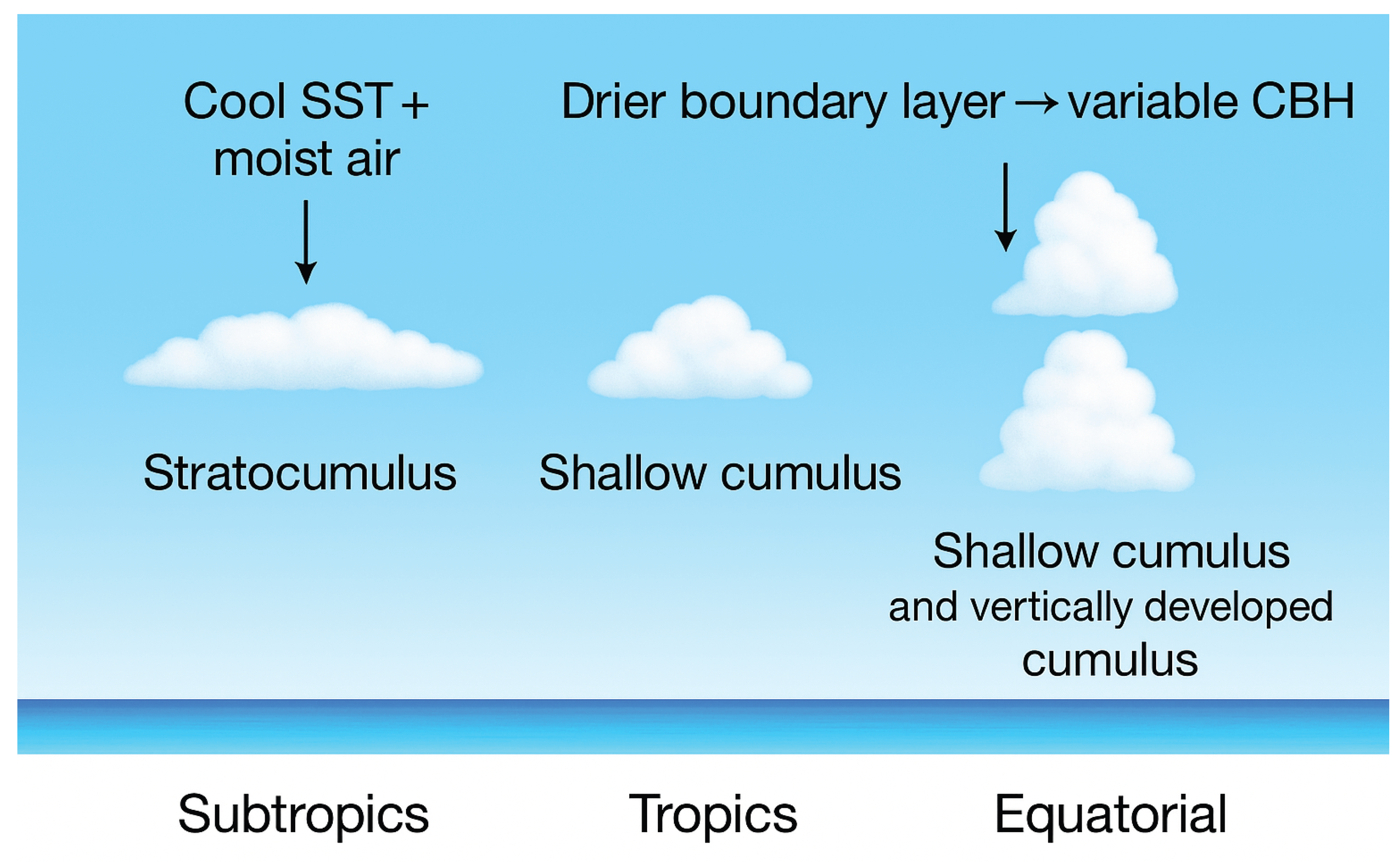

Low clouds typically form within the planetary boundary layer, the lowest part of the atmosphere directly influenced by surface heating, cooling, and turbulence. This layer is critical to day-to-day weather patterns and land–atmosphere interactions. Over ocean regions, cloud base height exhibits a distinct latitudinal transition. In the subtropics, cool sea surface temperatures and moist boundary-layer conditions favor stratocumulus with relatively low and stable bases. Toward the tropics, warmer waters and a drier boundary layer support shallow cumulus with more variable bases. Near the equator, cumulus clouds become dominant, often forming with higher and less constrained bases. This progression is consistent with the conceptual framework illustrated in

Figure 1, linking sea surface temperature and boundary-layer humidity to CBH variability across oceanic regimes.

Boundary-layer clouds such as cumulus, stratocumulus, and stratus constitute nearly half of global cloud cover. During the daytime, they reflect sunlight, causing surface cooling, while at night, they trap longwave radiation, producing localized warming. Their net effect is a cooling of the Earth’s surface by reflecting solar radiation back to space, thereby helping regulate surface temperatures. These clouds are also crucial in precipitation and weather systems, as shallow cumulus clouds can develop into deeper convective systems that generate storms and rainfall. Additionally, they contribute significantly to moisture transport, especially in tropical regions. The evolution of low clouds can also influence temperature forecasts, the initiation of convection, and fog formation. Thus, accurately modeling these clouds can improve short-term weather predictions.

They are most easily detected using ground-based instruments such as ceilometers, lidars, and radars, as well as space-based satellites employing passive infrared and visible (IR/VIS) sensing methods. However, determination of cloud height obtained via passive remote sensing methods becomes especially valuable in areas where active remote sensing instruments like lidar or ceilometers are unavailable. This includes remote regions with limited surface observations but accessible satellite imagery or field campaigns with stereo or shadow-sensitive sensors. These shadow-sensitive instruments detect cloud shadows on the ground, and by combining the measured shadow displacement with solar angle, cloud base height can be accurately estimated.

An important geometric consideration is the aspect ratio of clouds. For shallow, flat cumulus and stratocumulus layers, the shadow displacement corresponds closely to the cloud base height, since their vertical extent is small compared with their horizontal scale. In contrast, for more vertically developed convective clouds, the shadow signature is increasingly influenced by the total cloud height rather than just the base. Radiosonde profiles provide an independent way to distinguish between these cases, confirming that for shallow boundary-layer clouds the shadow-derived height represents the base, whereas for taller systems it reflects the full depth of the cloud column. This perspective is adopted in this study, as the method is most applicable to low-level clouds.

The shadow-based height retrieval method, grounded in sun–sensor geometry, offers a valuable tool for estimating the vertical structure of clouds, plumes, or surface features on other planetary bodies where direct measurements are limited or unavailable [

1,

2,

3]. Similar shadow analysis techniques have also been used in ecological applications, such as detecting emperor penguin colonies in Antarctica, where satellite imagery distinguished penguins, shadows, and guano to map colony locations and estimate population sizes in a synoptic, global survey [

10]. This demonstrates the broader potential of shadow-based methods for identifying physical features in remote environments. In principle, differences in shadow length could even be used to distinguish between adult penguins and chicks, owing to their markedly different body sizes when observed under favorable solar geometry and resolution.

This method provides several distinct advantages over traditional techniques. One of the key advantages of the shadow method is that it provides geometric height estimation from a single optical image by analyzing the displacement between clouds or plumes and their shadows. This eliminates the need for stereo imaging or active sensors like lidar or radar. Moreover, stereo imaging, by contrast, is prone to angle-induced depth errors and requires multiple images with well-calibrated viewing geometry. Shadow-based methods are particularly advantageous when using satellite imagery, as the fixed orbital geometry and nadir viewing configuration eliminate the need for pitch, yaw, and tilt corrections commonly required in aircraft-based observations. This makes the technique especially useful in scenarios with limited instrument payloads, such as planetary missions. When applied to high-resolution satellite imagery, the method achieves fine spatial resolution, allowing detection of detailed atmospheric features like convective cloud tops or volcanic ash plumes. Unlike thermal infrared methods, which infer cloud-top pressure and require assumptions about atmospheric temperature profiles, the shadow method provides direct physical height estimates. It has been successfully applied on both Earth and Mars, demonstrating its versatility and effectiveness when visible shadows are present and accurate sun-sensor geometry is known.

Despite certain constraints, such as reliance on clear shadows, flat terrain, and favorable solar geometry, the method is highly effective for shallow, isolated cumulus clouds commonly found in the PBL. It performs best away from solar noon, where shadows are well defined, and is less reliable in scenes with overlapping shadows, diffuse edges, or low contrast. Importantly, the method estimates cloud base height directly from shadow length, independent of cloud thickness or cloud-top height. This aspect is particularly valuable for shallow cloud layers.

To estimate the displacement between cloud and shadow features, this study employs a KD-tree-based nearest-neighbor search. Unlike classical approaches that rely on template matching, pattern correlation, or Hough transforms [

11,

12], the KD-tree technique avoids strict one-to-one pairing and instead leverages a statistical average over the cloud–shadow field.

This method is applied to MODIS visible imagery under clear-sky conditions with shallow cumulus fields. The resulting cloud base height estimates were validated against collocated lidar measurements from the MPLNET (Micro-Pulse Lidar Network) ground stations, and radiosonde measurements. Results demonstrate good agreement within expected error bounds, with discrepancies primarily arising in cases of shadow ambiguity or terrain-induced bias. The method proves particularly effective over vegetated, flat terrain, where shadow contrast is higher and surface variability is minimal.

While limitations exist, the approach presents a powerful tool for global daytime monitoring of PBL cloud base height using widely available passive satellite data. Additionally, the integration of machine learning techniques holds promise for automating shadow detection and improving robustness under suboptimal imaging conditions. Such enhancements could enable near-real-time or diurnal-scale CBH retrievals, supporting applications in agriculture, fire weather forecasting, and short-term convective modeling.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the methodology and data used;

Section 3 presents the results;

Section 4 provides their analysis;

Section 5 summarizes the conclusions of this study;

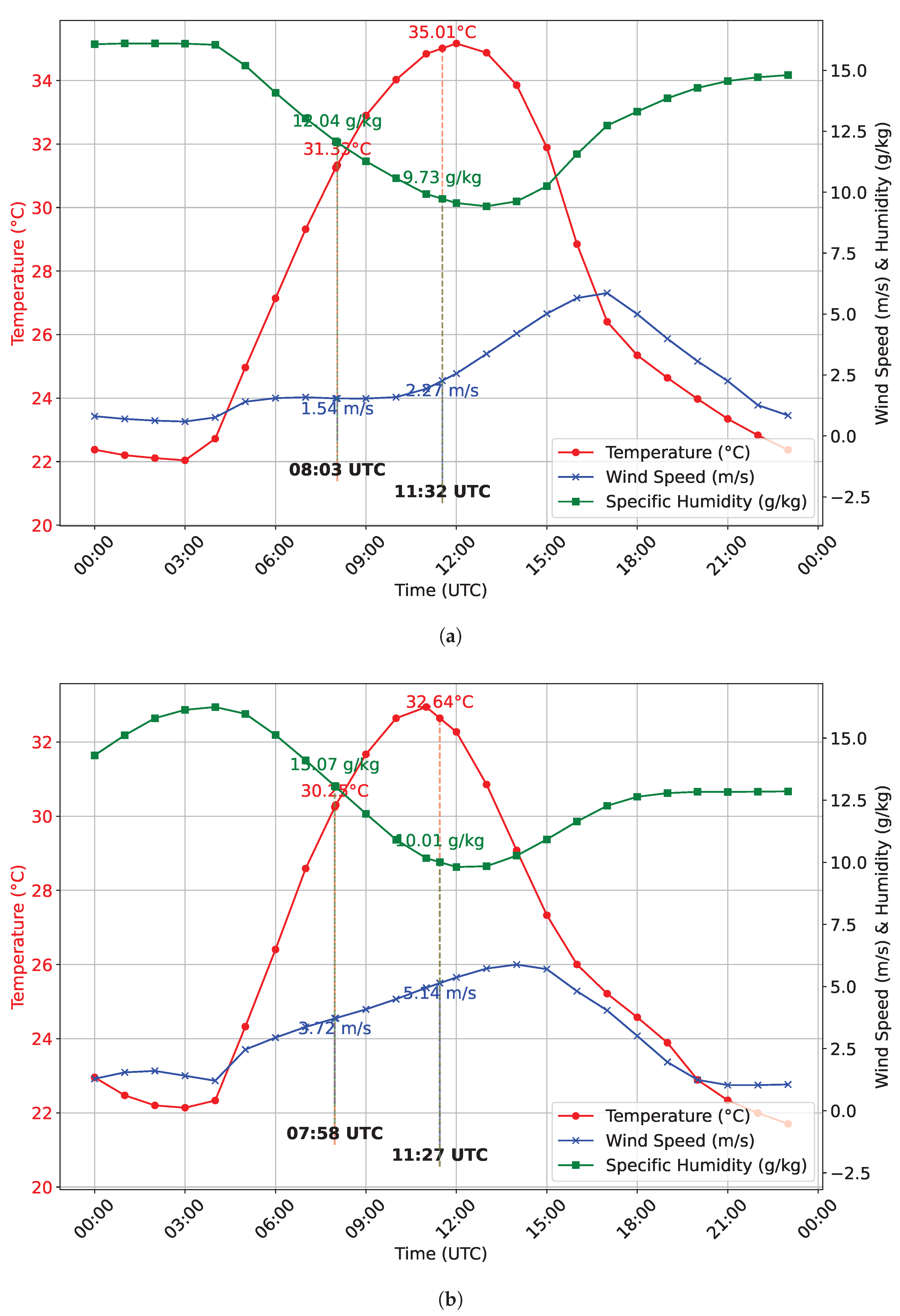

Appendix A presents surface-layer meteorological conditions at Sde Boker from MERRA-2 data, which support the interpretation of the case studies discussed in the main text.

Appendix B provides additional details on the analytical methods used for geometric height retrieval based on cloud and plume shadow displacement.

2. Method and Data

2.1. Cloud Base Height Estimation

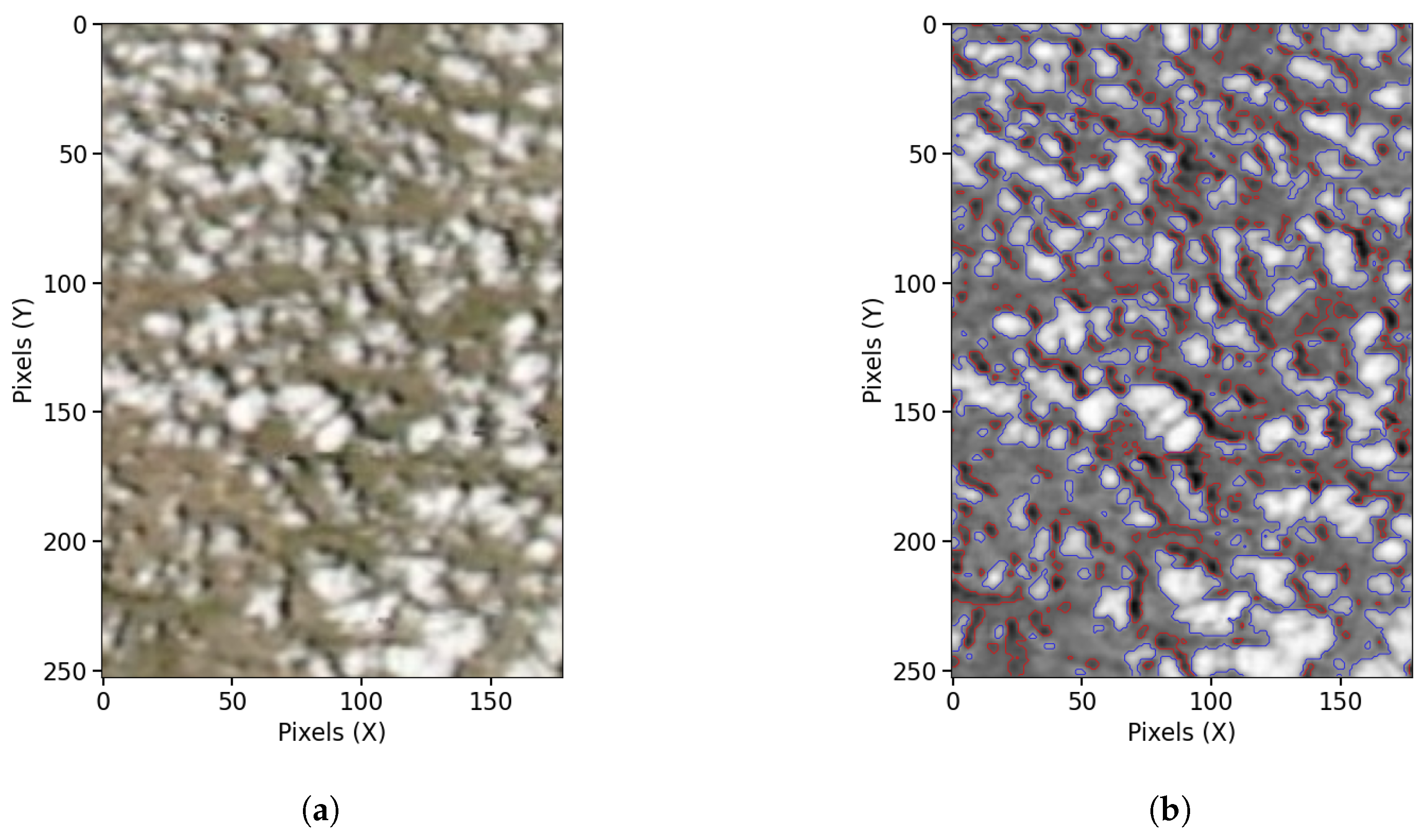

This study presents a method for estimating cloud base height using a single grayscale satellite or aerial image by analyzing the displacement between clouds and their corresponding shadows. The approach involves converting the image to grayscale and generating binary masks through intensity thresholding to identify bright clouds and dark shadows. Several key assumptions underlie the method: (1) sufficient contrast must exist between clouds, shadows, and the surface to allow reliable detection; (2) the terrain is assumed to be flat, simplifying geometric calculations by removing the influence of topographic variation; (3) the cloud field must be broken rather than overcast, ensuring that individual clouds and their shadows can be clearly paired; and (4) the solar zenith angle (SZA) must be greater than a certain threshold—i.e., the sun should not be directly overhead—to produce detectable shadow displacement. These assumptions enable a geometrically simplified yet effective means of estimating cloud base height from a single image.

To compute cloud base height, the Sun’s position is calculated based on the image’s acquisition time and geographic coordinates. From the solar azimuth and altitude, the solar zenith angle is derived, which governs the direction and length of shadows.

The spatial displacement between cloud and shadow pixels is measured using a KD-tree (k-dimensional tree) algorithm, a data structure optimized for efficient nearest-neighbor searches in multidimensional space. In this context, the pixel coordinates of shadow-labeled regions are used to construct the KD-tree, allowing for rapid queries to find the closest shadow pixel corresponding to each identified cloud pixel. By averaging the resulting distances across all cloud pixels, the method yields a representative displacement vector between cloud and shadow formations. The KD-tree technique avoids strict one-to-one pairing and instead leverages a statistical average over the cloud–shadow field. While this generalization reduces sensitivity to small-scale noise and segmentation imperfections, it may introduce slight overestimations in cases where multiple clouds project onto shared or elongated shadow regions. Nonetheless, the KD-tree method is particularly useful when cloud structures are discrete and the shadow field is sufficiently resolved, offering a practical alternative to more complex cloud–shadow association algorithms found in the literature.

To formalize the KD-tree-based cloud–shadow association, the geometric displacement between paired pixels can be expressed as follows.

Let

denote the set of coordinates of detected cloud pixels,

denote the set of coordinates of detected shadow pixels.

A KD-tree data structure is constructed using the shadow pixel coordinates

S to enable efficient nearest-neighbor queries [

13]. For each cloud pixel

, the nearest shadow pixel

is found by minimizing the Euclidean distance:

where

represents the Euclidean norm. The average displacement across all

n cloud pixels is calculated as:

The quantity corresponds to the mean shadow displacement measured in pixels.

To convert the average pixel displacement into a physical cloud base height

H (in meters), the image resolution (ground sampling distance)

r in meters per pixel and the solar zenith angle

(in degrees) are incorporated. The cloud base height is estimated by projecting the displacement onto the vertical using the tangent of the solar zenith angle:

This approach assumes that the solar zenith angle provides the angle between the sun’s rays and the vertical, thereby linking shadow displacement to the height of the cloud base.The formulation is based on several simplifying assumptions: the underlying terrain is flat with no significant elevation variation; cloud and shadow regions are distinct and non-overlapping; and the solar zenith angle is sufficiently large to produce visible horizontal shadows. Within this framework, the KD-tree method provides a computationally efficient and scalable solution for estimating cloud base height from a single satellite or airborne image, particularly in cases of fair-weather cumulus clouds with well-defined shadows.

The resulting nearest-neighbor distances are averaged and converted into physical distances using an assumed ground resolution of 250 meters per pixel, which are then combined with trigonometric projection to estimate the vertical height from which the shadow originated—interpreted as the cloud base height.

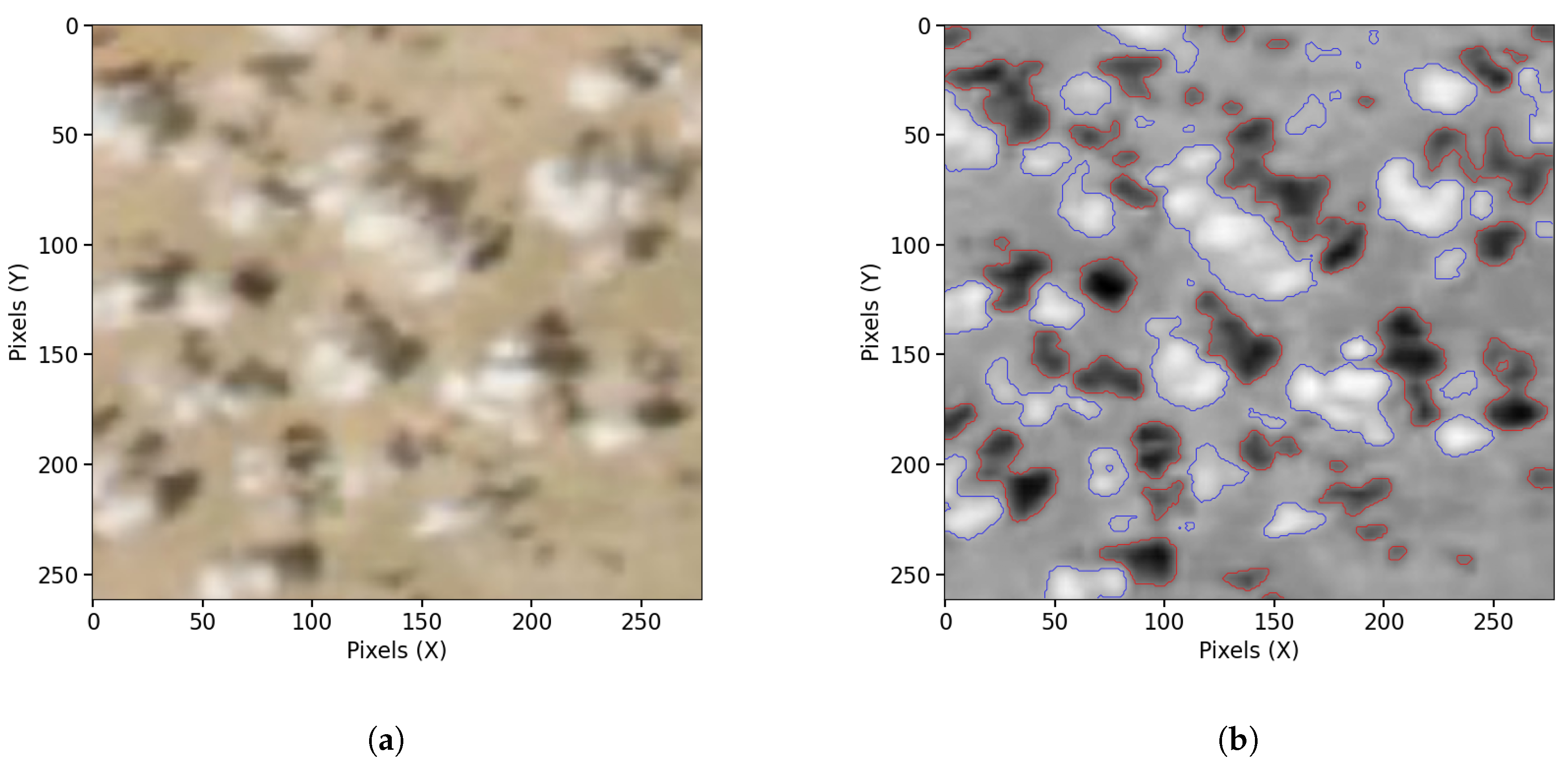

Validation of this approach was performed by comparing the results against LiDAR-derived cloud base heights, showing strong agreement when shadows were clearly defined. The method was applied to different environments, including over-ocean scenes, where poor contrast made shadow detection difficult, and over the Sde Boker in the Negev Desert at two distinct local times to observe the effects of changing solar geometry. However, due to limited image availability, a full diurnal analysis could not be conducted. Despite this limitation, the method offers a practical and efficient way to estimate cloud base height from single-pass imagery, particularly in remote or data-scarce regions where multi-angle or multi-temporal datasets are unavailable.

Another cloud base height estimation method, using MERRA-2 reanalysis data, is described in

Appendix B, with the corresponding results presented in

Section 3.

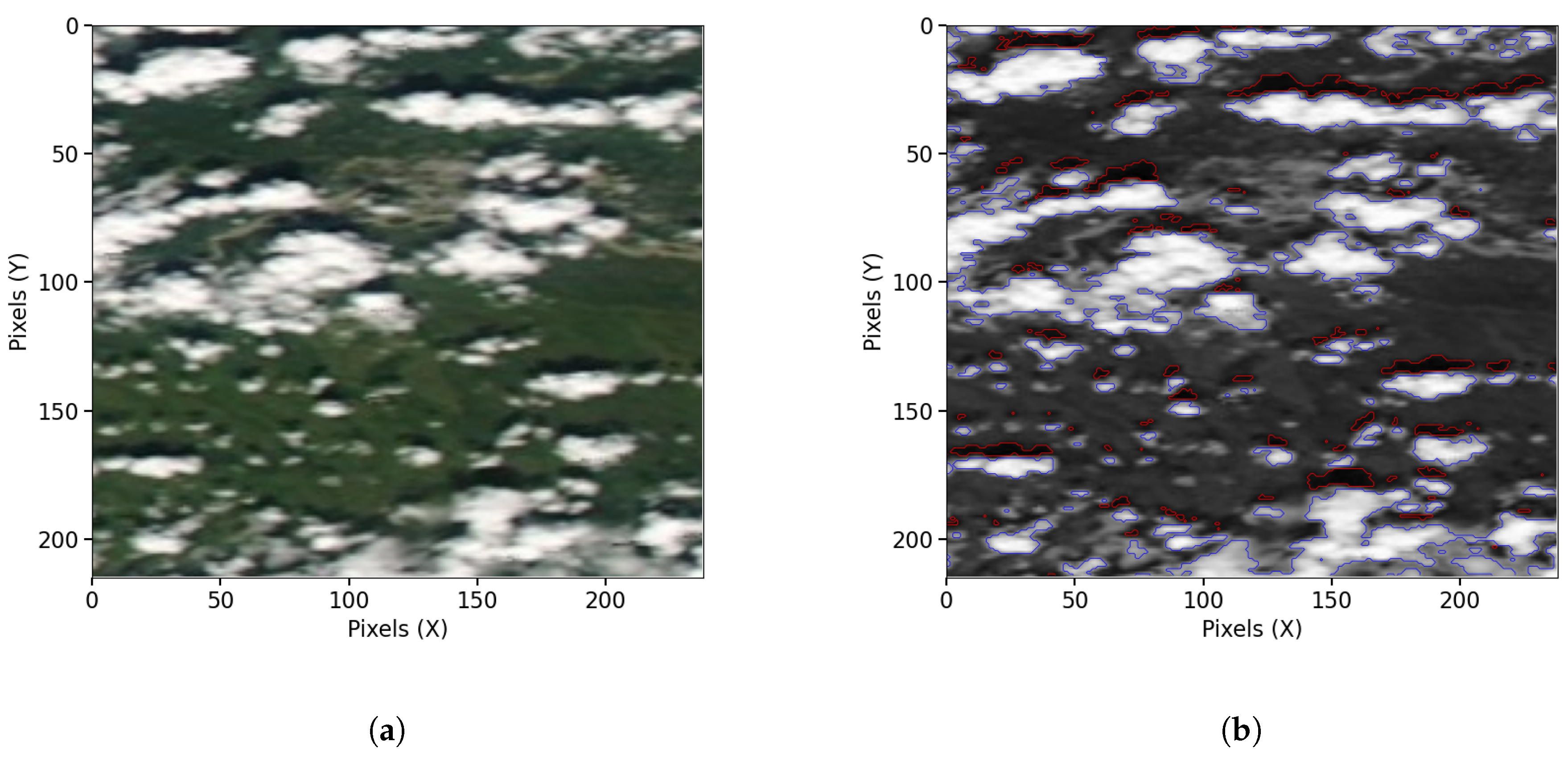

Figure 2.

MODIS Aqua imagery over Fairbanks, Alaska, on 26 July 2021. (

2(a)) shows shallow, fair-weather cumulus humilis clouds observed at 21:34 UTC, used to demonstrate a shadow-based cloud base height retrieval technique under clear-sky conditions. (

2(b)) builds on this example and illustrates the KD-tree-based cloud–shadow matching approach, with cloud masks outlined in blue and shadow masks in red.

Figure 2.

MODIS Aqua imagery over Fairbanks, Alaska, on 26 July 2021. (

2(a)) shows shallow, fair-weather cumulus humilis clouds observed at 21:34 UTC, used to demonstrate a shadow-based cloud base height retrieval technique under clear-sky conditions. (

2(b)) builds on this example and illustrates the KD-tree-based cloud–shadow matching approach, with cloud masks outlined in blue and shadow masks in red.

2.2. Data

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) is a key instrument aboard NASA’s Terra (launched in 1999) and Aqua (launched in 2002) satellites. The MOD02QM (Terra) and MYD02QM (Aqua) products contain calibrated radiance data from the 250 m resolution bands (Bands 1 and 2), primarily in the red and near-infrared wavelengths. These products offer 5-minute granules of Level-1B radiance data, ideal for high-resolution analysis of cloud optical and geometric properties, including shadow-based cloud base height estimation. Terra (MODIS) crosses the equator at approximately 10:30 AM local time (descending node), while Aqua (MODIS) crosses at around 1:30 PM (ascending node), enabling synergistic morning and afternoon observations. Cloud height information was compared against collocated MPLNET (Micro-Pulse Lidar Network) measurements [

14]. Version 3 MPLNET lidar data were used here to provide information on atmospheric vertical structure and aerosol height and backscatter properties [

15]. The MPLNET data are available online at

https://mplnet.gsfc.nasa.gov, accessed on 7 November 2024. Radiosonde profiles were used to provide independent atmospheric validation and to confirm that the shadow length corresponds to cloud base height rather than cloud top height. Sounding data were obtained from the University of Wyoming’s Upper Air Archive, which offers a global, long-term dataset of radiosonde observations. These include vertical profiles of temperature, pressure, humidity, and wind, typically launched twice daily at 00 and 12 UTC. For this study, radiosonde measurements from the Bet Dagan station in Israel (WMO ID: 40179) launched at 12 UTC were used to closely coincide with the MODIS Aqua overpass time, allowing evaluation of the thermodynamic consistency of MODIS-derived cloud base heights and estimation of the lifting condensation level (LCL) under clear-sky conditions. The sounding data are publicly available at

https://weather.uwyo.edu/upperair/sounding.shtml (accessed on November 7, 2024).

5. Conclusion

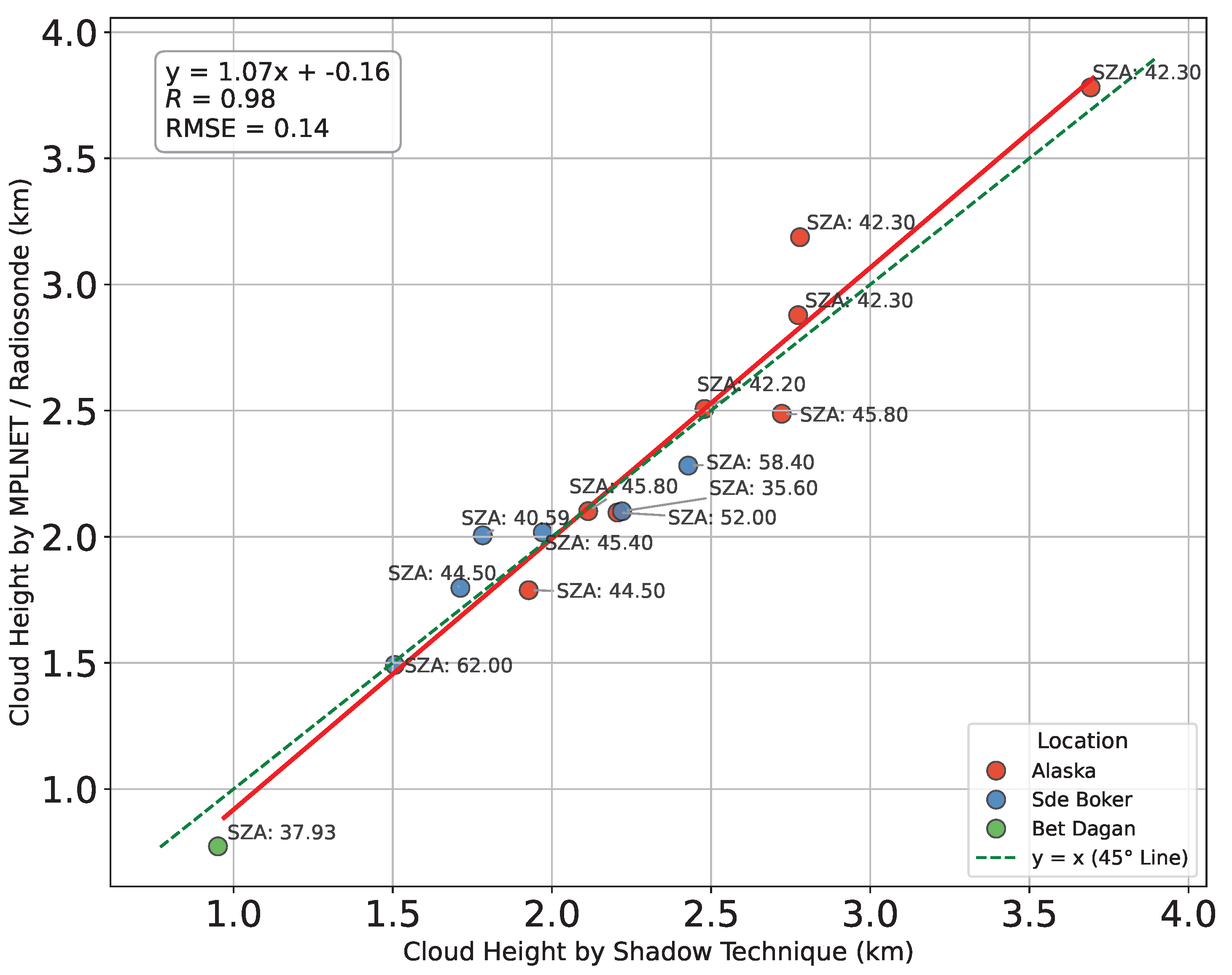

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of a shadow-based remote sensing approach for estimating planetary boundary layer (PBL) cloud base height (CBH) using MODIS visible imagery. By combining cloud–shadow displacement with solar geometry, the method directly estimates CBH from geometry, without requiring cloud-top information, stereo imaging, or active sensors. Validation against collocated MPLNET lidar and radiosonde measurements shows strong agreement (, RMSE km or 140 m), confirming the reliability of the approach for shallow, isolated cumulus clouds.

The technique successfully captures diurnal variations in cloud development, with cloud bases observed to rise from morning to afternoon in response to boundary layer deepening and enhanced convection. As surface heating progresses, moist parcels are mixed upward until reaching the lifting condensation level, forming clouds at higher altitudes later in the day. This consistency with boundary-layer thermodynamics underscores the physical robustness of the approach.

Results over the ocean further demonstrate the method’s ability to resolve spatial variability in CBH under different surface and atmospheric conditions (

Table 3). Higher humidity and cooler sea surface temperatures were associated with shallower cloud bases, while drier conditions and weaker winds coincided with deeper boundary layers and higher CBH. The tropical case revealed mixed shallow and moderately developed cumuli, highlighting the technique’s sensitivity to local forcing and its utility for capturing cloud variability across marine environments.

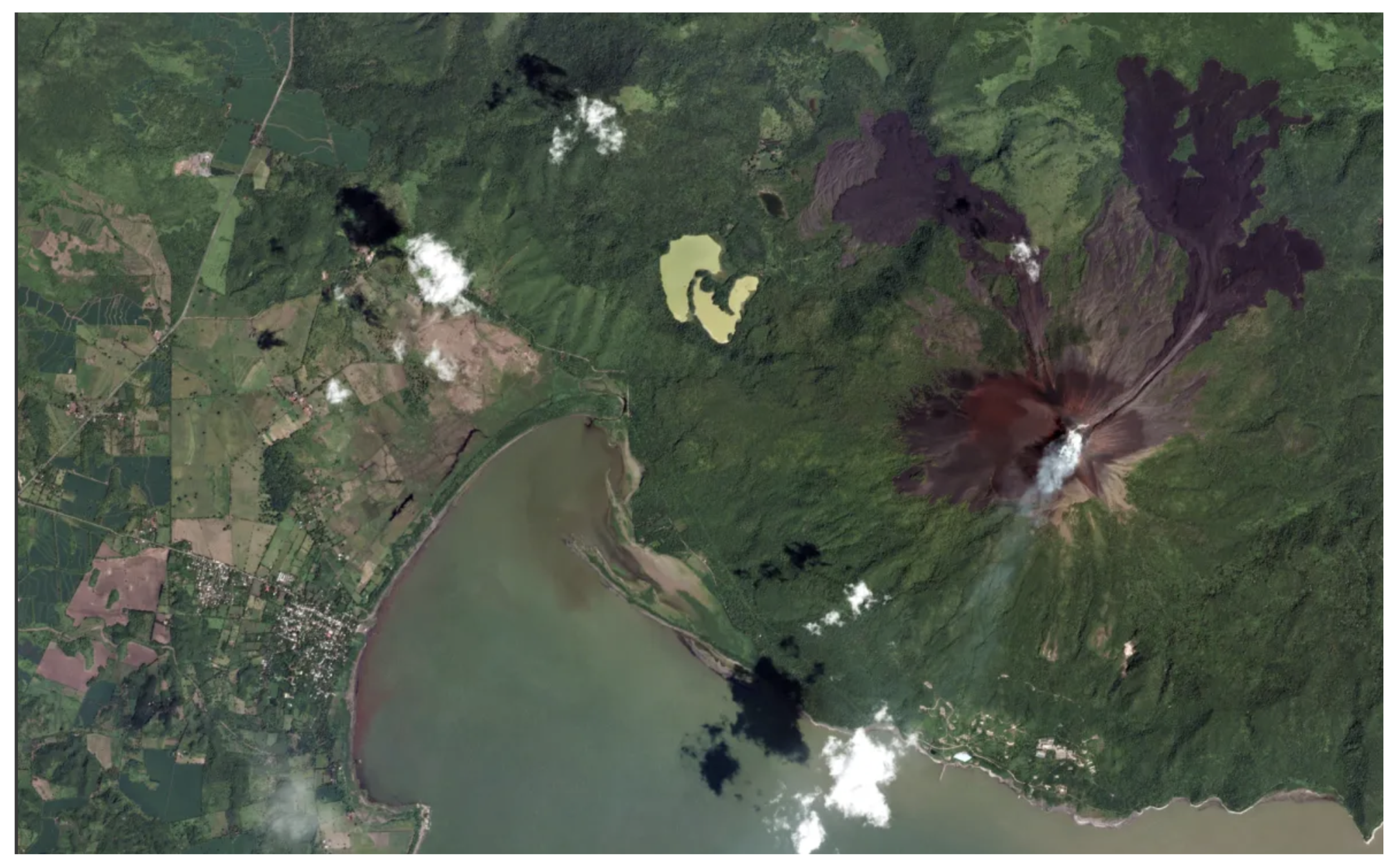

The same geometric principle was extended to high-altitude volcanic plumes, as illustrated for the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai eruption. By computing the great-circle (haversine) distance between plume and shadow coordinates and applying parallax correction for oblique viewing geometry, the method retrieved physically consistent multi-level plume heights from GOES-17 imagery. This extension demonstrates the scalability of the shadow-based technique from low-level boundary-layer clouds to stratospheric plume analysis.

Although the method is limited by solar geometry, terrain complexity, and shadow ambiguity, these challenges can be mitigated through higher-resolution satellite sensors (e.g., Sentinel-2, PlanetScope, WorldView) and automated shadow detection. The increasing availability of such data opens opportunities to extend the approach beyond CBH retrieval to plume height estimation, volcanic ash monitoring, vegetation structure analysis, and urban feature mapping. Future work should focus on extending validation to diverse climates and seasons, as well as exploring machine learning techniques to improve retrievals under suboptimal conditions.

Overall, the shadow-based technique provides direct geometric estimates of CBH without requiring atmospheric profiles or active sensors. The method’s low computational cost and reliance on widely available satellite data make it a valuable tool for atmospheric research, weather forecasting, renewable energy, and planetary science applications. Future research should explore integration with AI-based cloud segmentation to extend retrievals to multilayer scenes and coastal transition zones.