Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

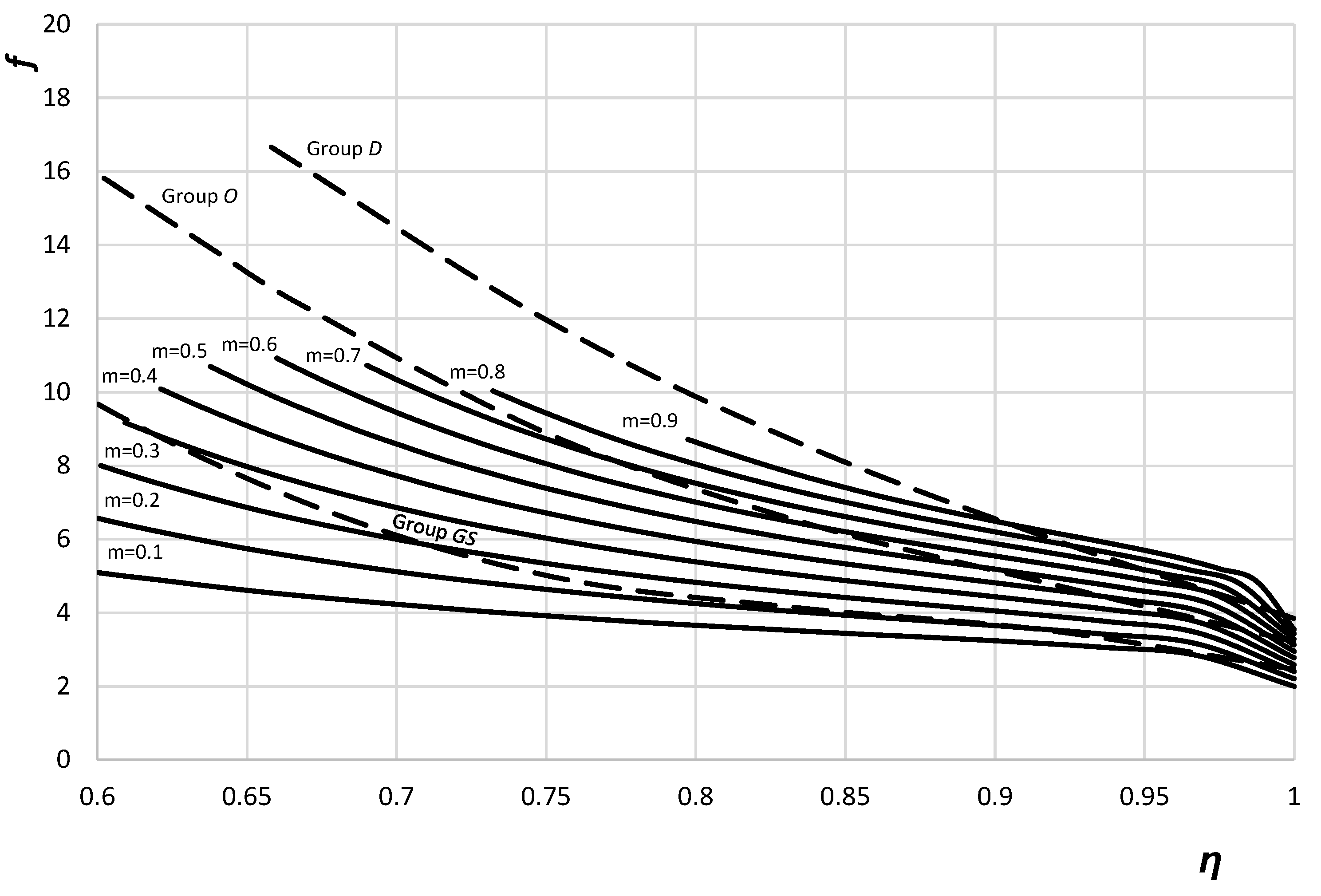

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

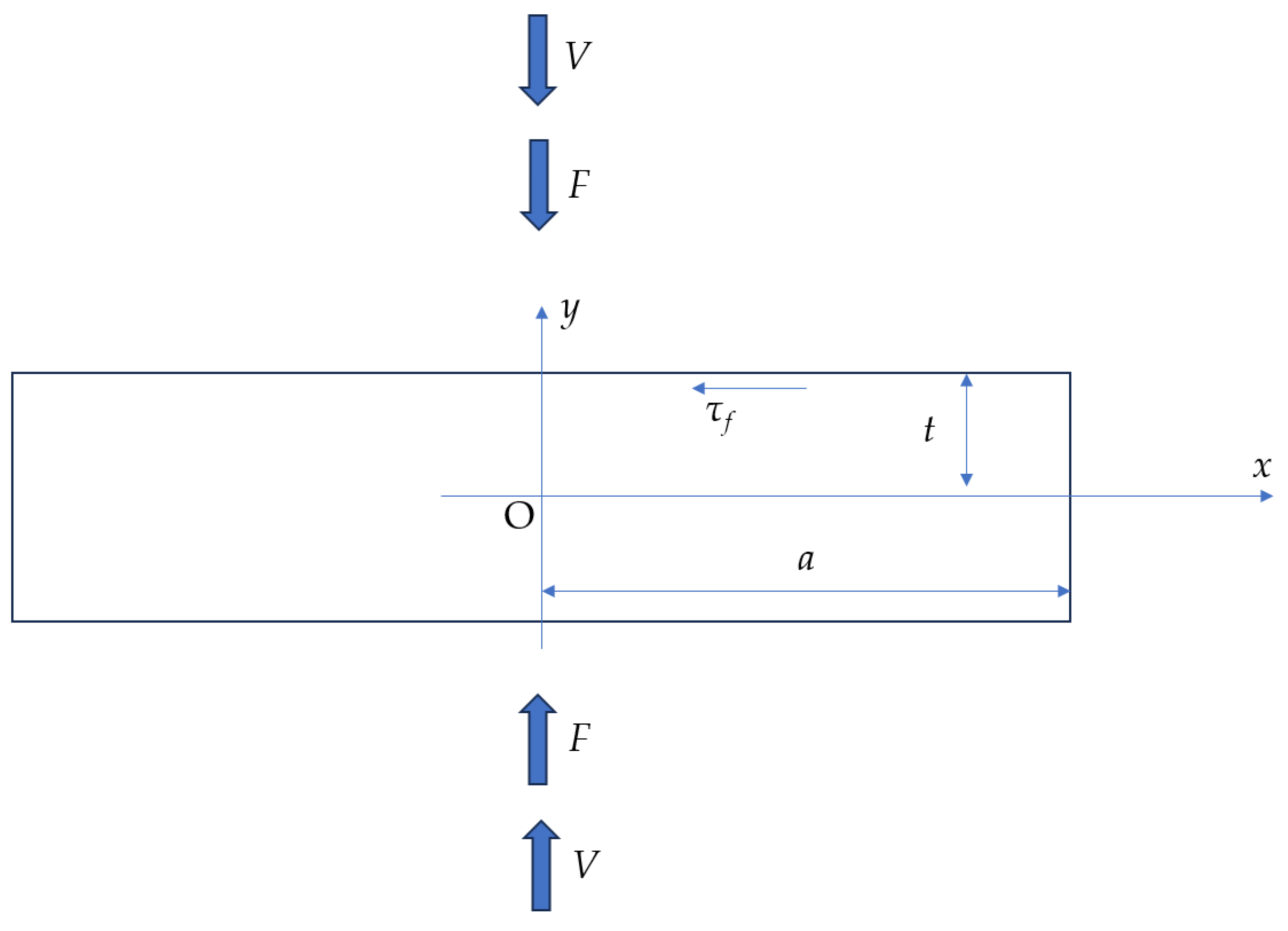

3. Plane Strain Compression

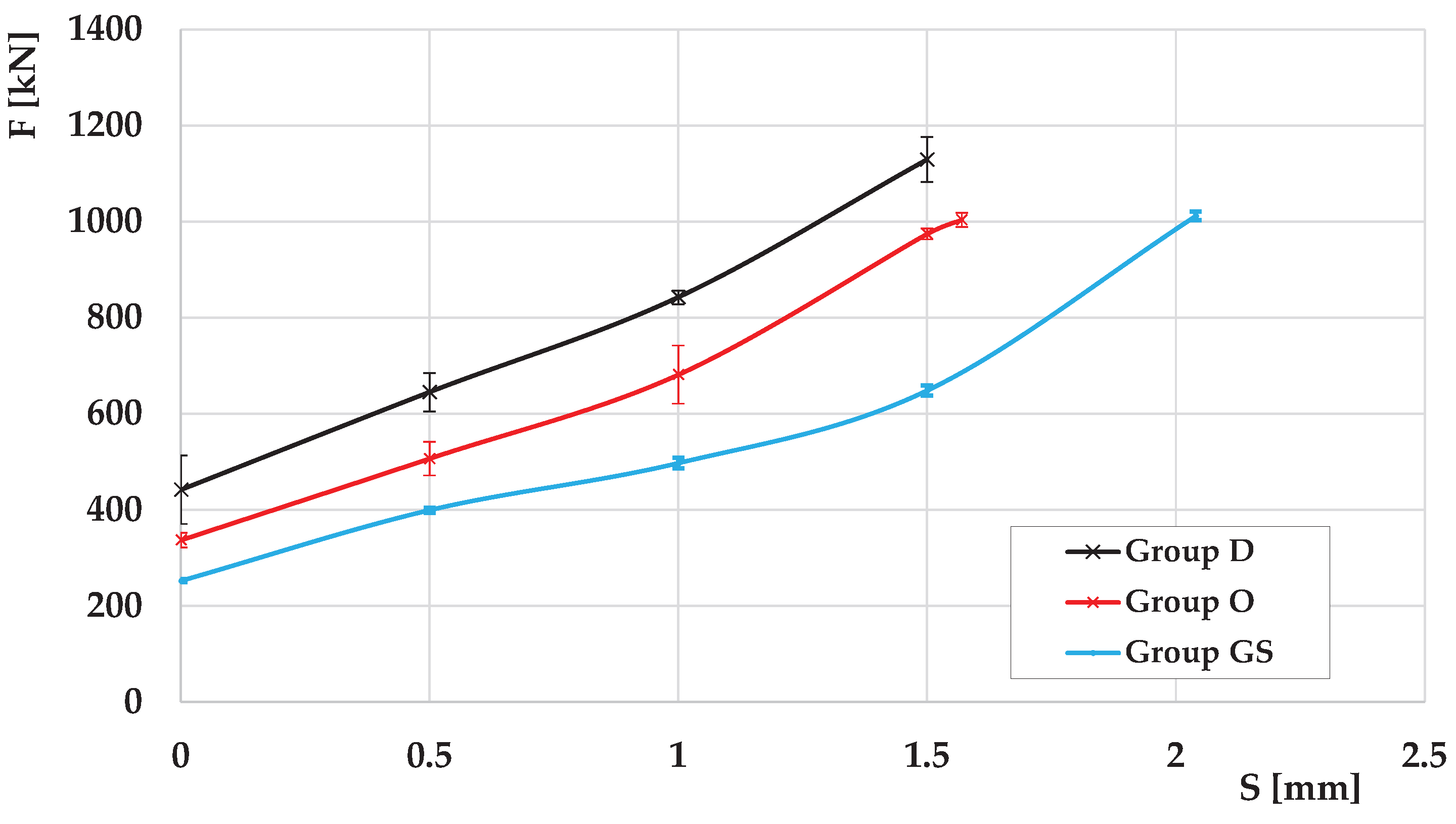

3.1. Experiment

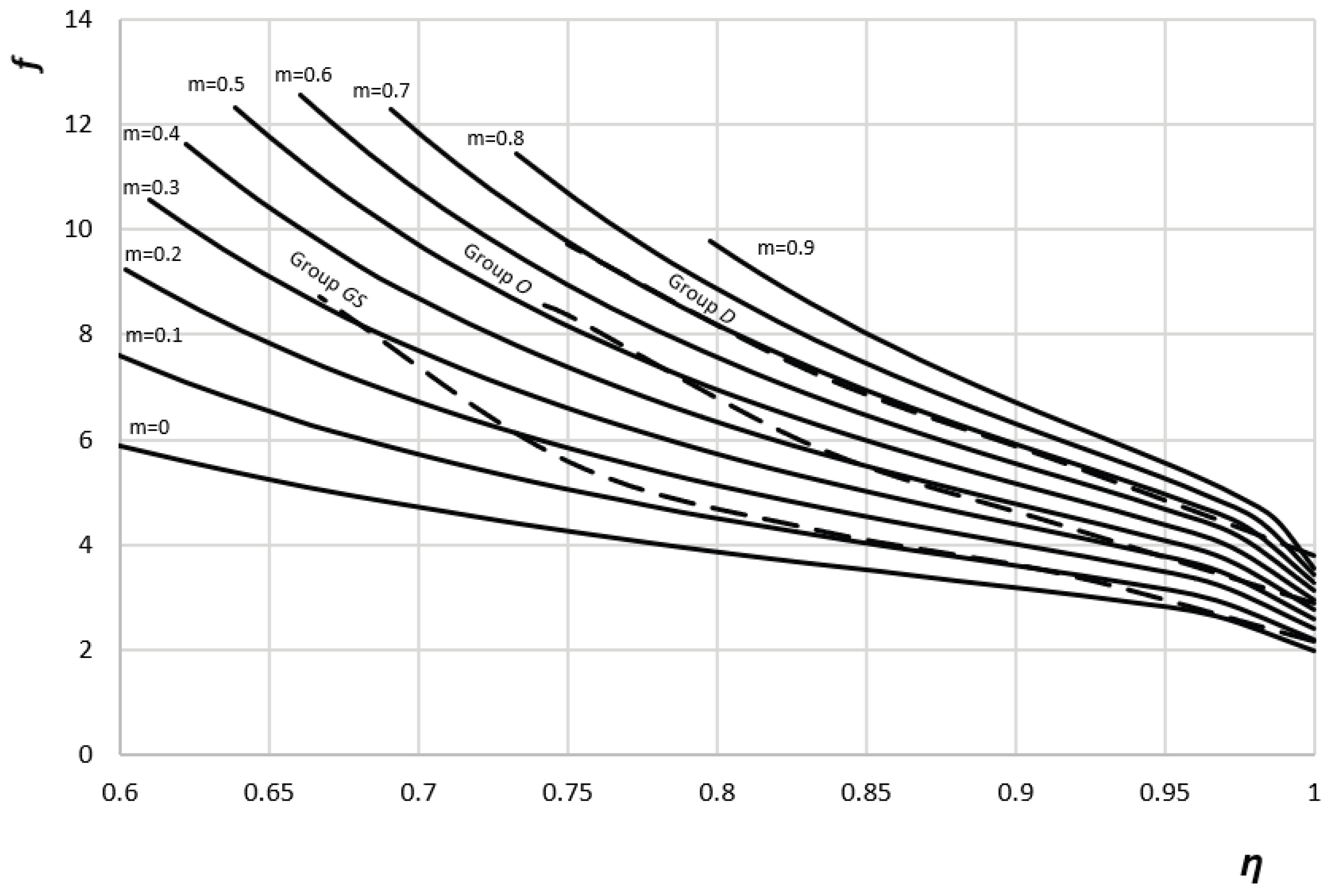

- MOLUB HK cold forging oil (ISO 6743/7, L – MHE; ISO/TS 12927), manufactured by Oil Refinery Modriča, Bosnia and Herzegovina – group O,

- Mixture of MoS₂ grease and stearin – group GS,

- No lubricant – group D.

3.2. Theory

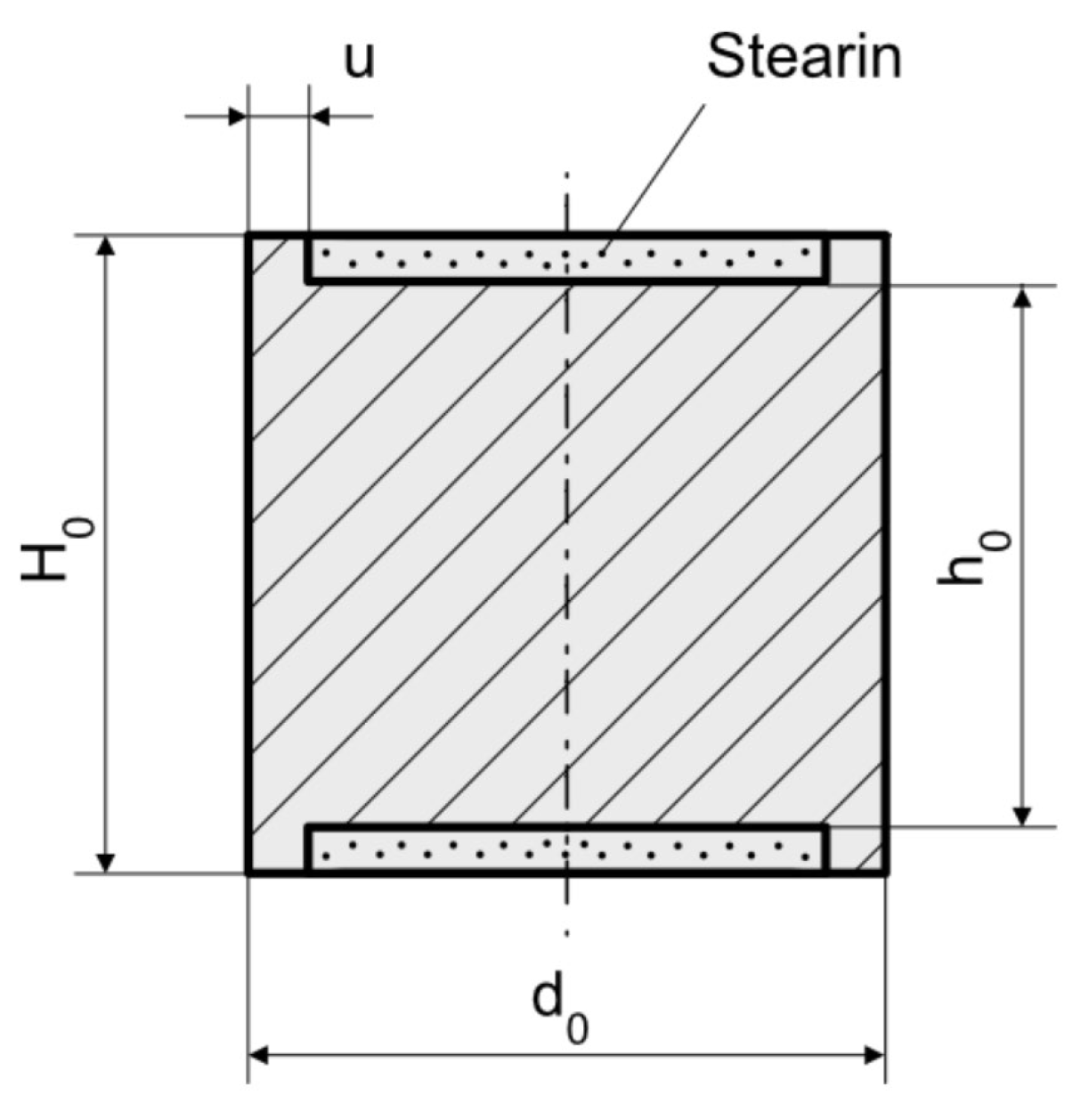

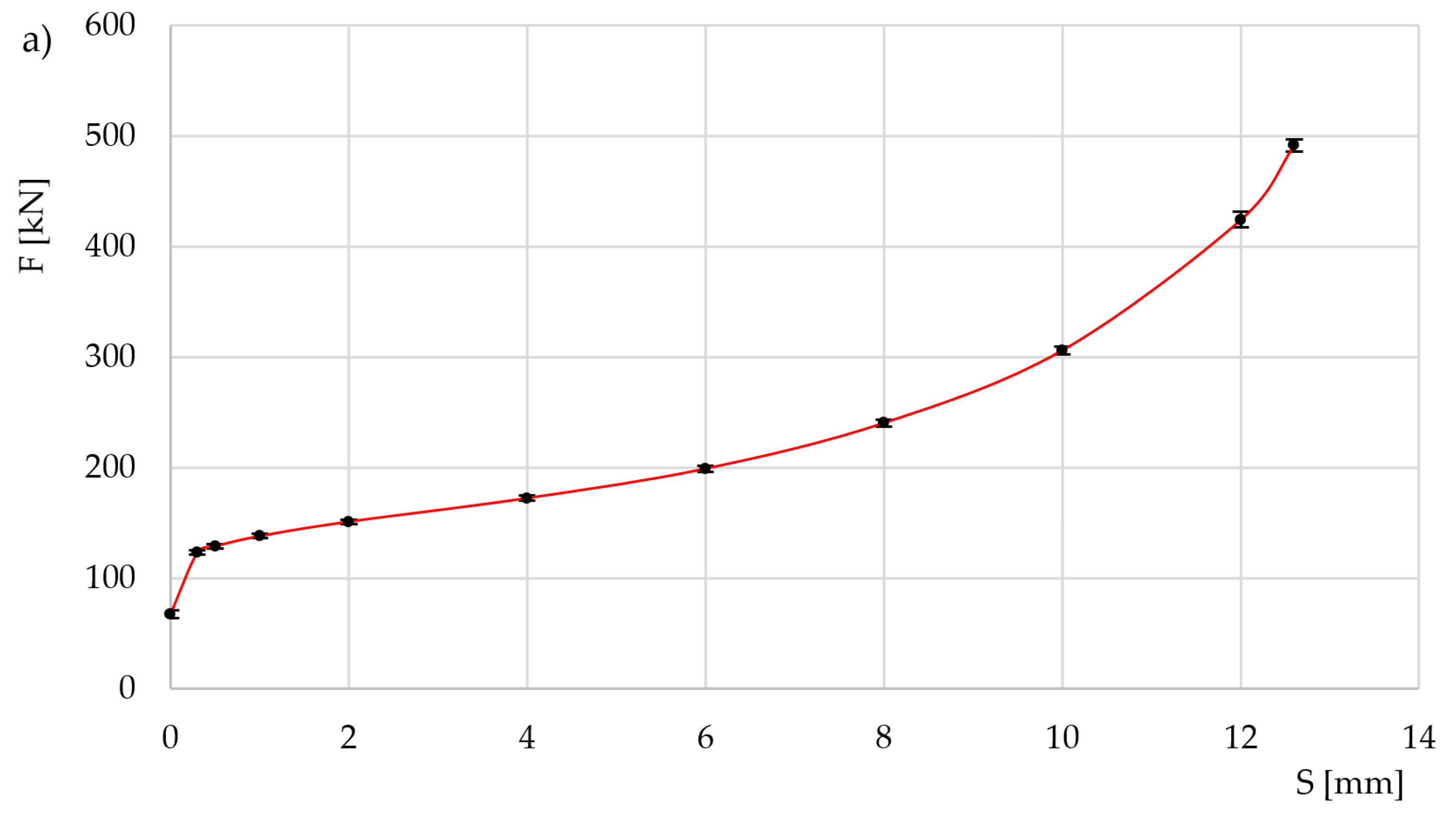

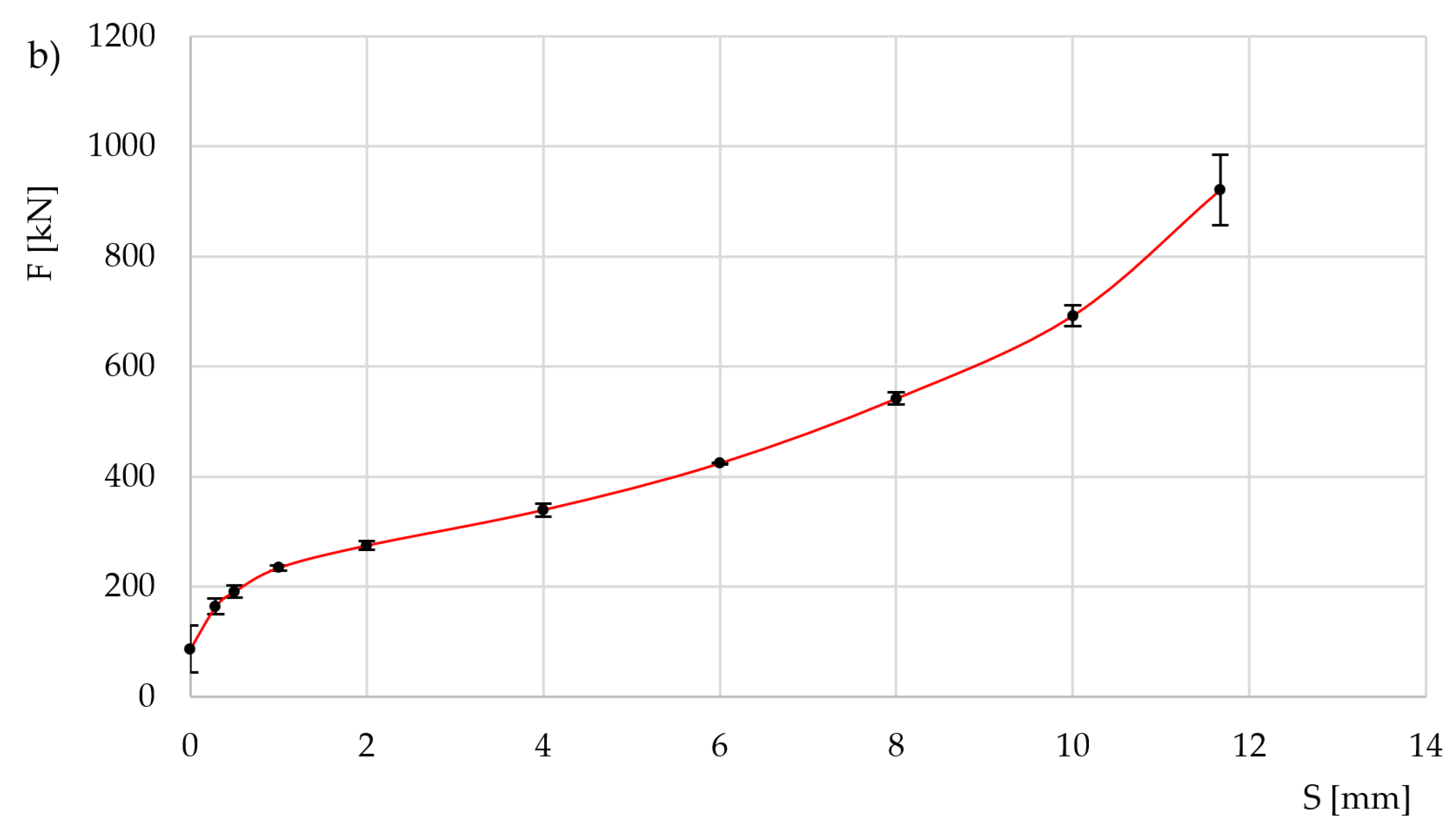

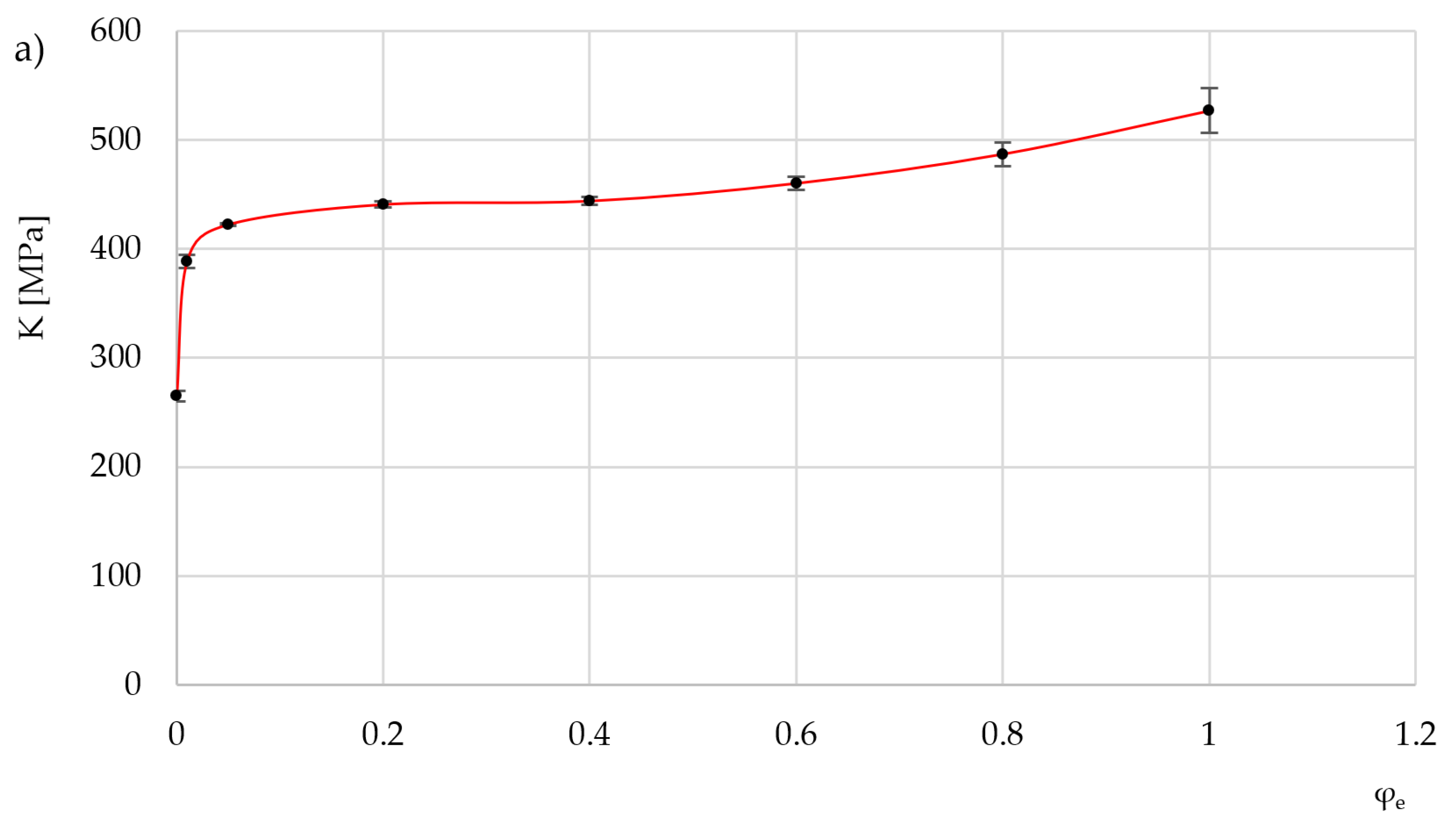

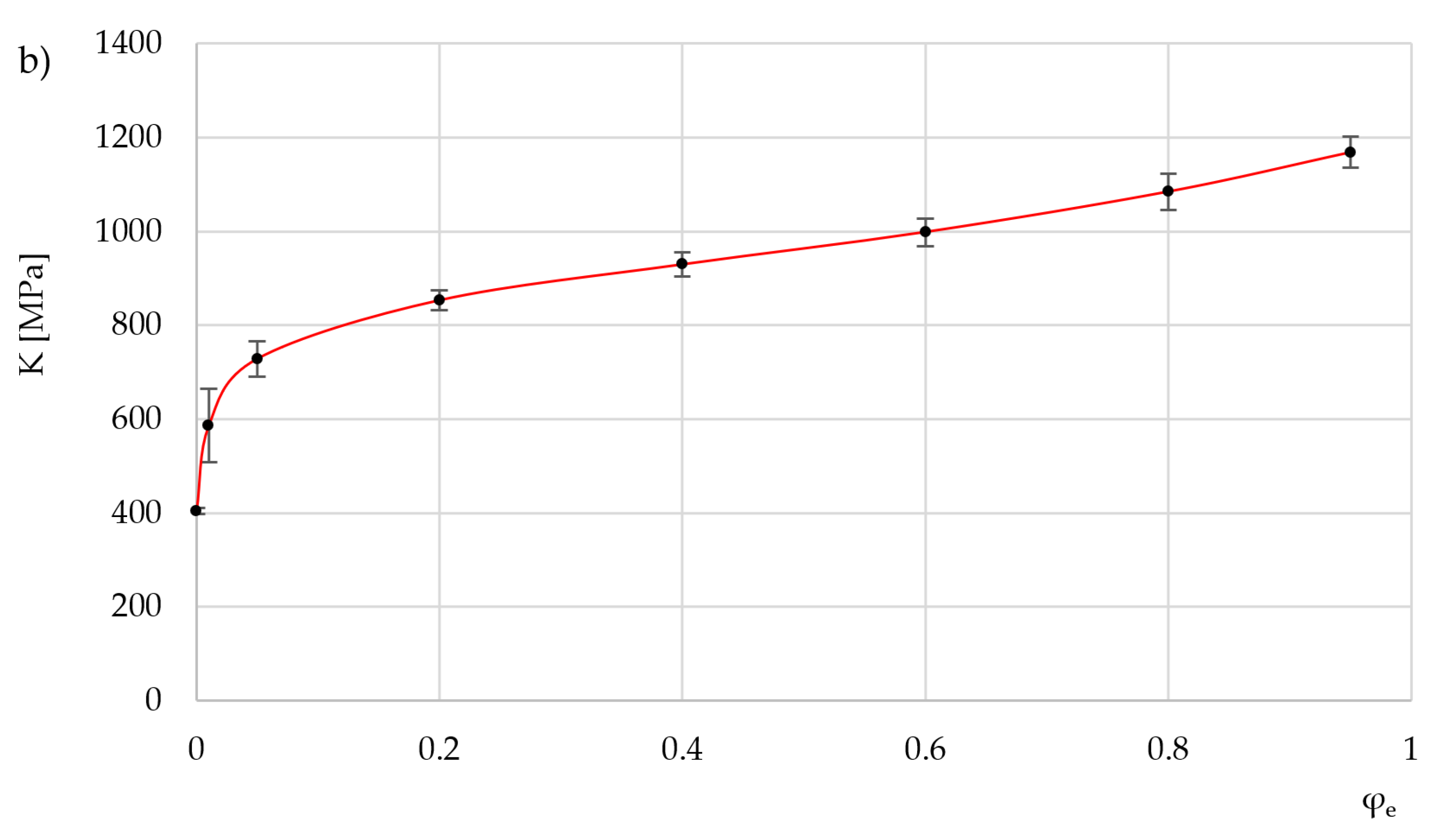

4. Cylinder Compression Test

5. Determination of the Friction Factor

6. Conclusions

- The proposed method is efficient for evaluating the friction law (5) as the theoretical solution is relatively simple.

- The friction law (5) is not a good approximation of the friction stress, except for the steel specimens deformed with no lubricant.

- The lubricant denoted as Group GS is more efficient than that denoted as Group O.

- The overall structure of the theoretical solution suggests that it can be extended to a generalized friction law that accounts for the variation in the friction factor as deformation proceeds, providing a theoretical basis for further research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Male, A.T.; Cockcroft, M.G. A method for the determination of the coefficient of friction of metals under conditions of bulk plastic deformation. J. Inst. Met. 1964–1965, 93, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.Q.; Ma, Q.X. Evaluation of Rheological Behavior and Interfacial Friction under the Adhesive Condition by Upsetting Method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 79, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, S.; Lyamina, E.; Jeng, Y.-R. A General Kinematically Admissible Velocity Field for Axisymmetric Forging and Its Application to Hollow Disk Forging. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 88, 3113–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkeri, S.; Patil, N.A.; Singh, S. Validation of Experimental Conditions with Standard Friction Models during Al 6061 Ring Compression Test under Various Interfacial Conditions. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2025, 39, 2609–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukugaichi, S.; Suga, Y.; Noura, S.; Takeyama, K.; Kitamura, K.; Aono, H. Frictional Property of Anionic-Surfactant-Loaded MgAl-Layered Double Hydroxide Films on Aluminum Alloy Using a Ring Compression Test. Tribol. Int. 2025, 210, 110810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Cui, M.; Zhao, S. Variation of the Friction Conditions in Cold Ring Compression Tests of Medium Carbon Steel. Friction 2020, 8, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.-M.; Lu, C.-Y.; Lin, G.-D.; Wang, C.-C. Die Design and Finite-Element Analysis for the Hot Forging of Automotive Wheel Frames Made of Aluminium Alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 2681–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, R.; Najafizadeh, A. A New Method for Evaluation of Friction in Bulk Metal Forming. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2004, 152, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschhausen, A.; Weinmann, K.; Lee, J.Y.; Altan, T. Evaluation of Lubrication and Friction in Cold Forging Using a Double Backward-Extrusion Process J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1992, 33, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avitzur, B.; Van Tyne, C.J. Ring Forming: An Upper Bound Approach. Part 1: Flow Pattern and Calculation of Power. J. Eng. Ind. 1982, 104, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avitzur, B.; Van Tyne, C.J. Ring Forming: An Upper Bound Approach. Part 2: Process Analysis and Characteristics. J. Eng. Ind. 1982, 104, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.H. Large Deformation of Structures by Sequential Limit Analysis. Int. J. Solids. Struct. 1993, 30, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. The Mathematical Theory of Plasticity, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1950.

- Hill, R.; Lee, E.H.; Tupper, S.J. A Method of Numerical Analysis of Plastic Flow in Plane Strain and Its Application to the Compression of a Ductile Material Between Rough Plates. J. Appl. Mech. 1951, 18, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E.A. The Compression of a Slab of Ideal Soil between Rough Plates. Acta Mech. 1967, 3, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, I.F.; Meguid, S.A. On the Influence of Hardening and Anisotropy on the Plane-Strain Compression of Thin Metal Strip. J. Appl. Mech. 1977, 44, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Briscoe, B.J.; Corfield, G.M.; Lawrence, C.J.; Papathanasiou, T.D. An Analysis of the Plane-Strain Compression of Viscoplastic Materials. J. Appl. Mech. 1997, 64, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, S.; Jeng, Y.-R. Extension of Prandtl’s Solution to a General Isotropic Model of Plasticity Including Internal Variables. Meccanica 2024, 59, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, W.; Pöhlandt, K. The Rastegaev Upset Test-A Method To Compress Large Material Volumes Homogeneously. Exp. Tech. 1986, 10, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schey, J.A. Tribology in Metalworking: Friction, Lubrication, and Wear, American Society for Metals, Metals Park, 1983.

- Alexandrov, S.; Alexandrova, N. On The Maximum Friction Law for Rigid/Plastic, Hardening Materials. Meccanica 2000, 35, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group O, Al |

Group GS, Al |

Group D, Al |

Group O, Steel |

Group GS, Steel |

Group D, Steel |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f at η = 1 | 3.22 | 2.46 | 3.85 | 2.9 | 2.17 | 3.8 |

| Initial value of m | 0.67 | 0.22 | Very close to unity | 0.47 | 0.09 | Very close to unity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).