Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Volume: ML Ontology is the most comprehensive ontology for the domain of ML that the author is aware of.

- Performance: ML Ontology allows high-performance query access suitable for industry applications.

- Balance between simplicity and expressiveness: It is based on simple technology particularly suited for industry use, while at the same time offers expressive power, including sophisticated reasoning where needed.

- Extensibility and adaptability: ML Ontology is modularised and can be easily extended and adapted to differing use cases.

- Built-in quality management: ML Ontology comprises built-in quality checks that can be adapted use-case-specifically in order to ensure quality requirements from industry.

- Public availability: ML Ontology is published open source9 under an MIT license.

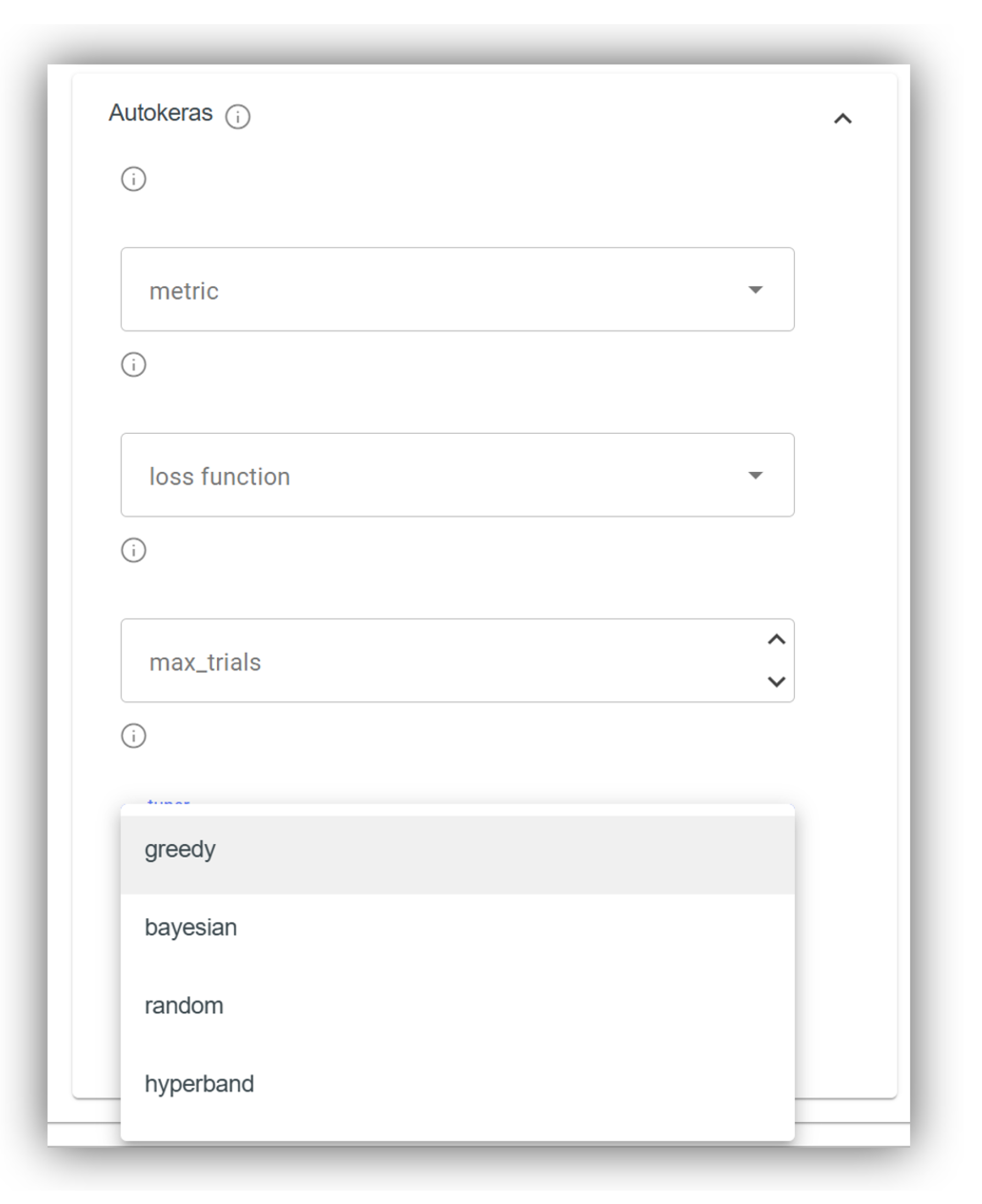

- Configuration wizard: ML Ontology serves as the information backbone for a data science platform. Its usage in the configuration wizard for expert configurations of ML training runs is demonstrated.

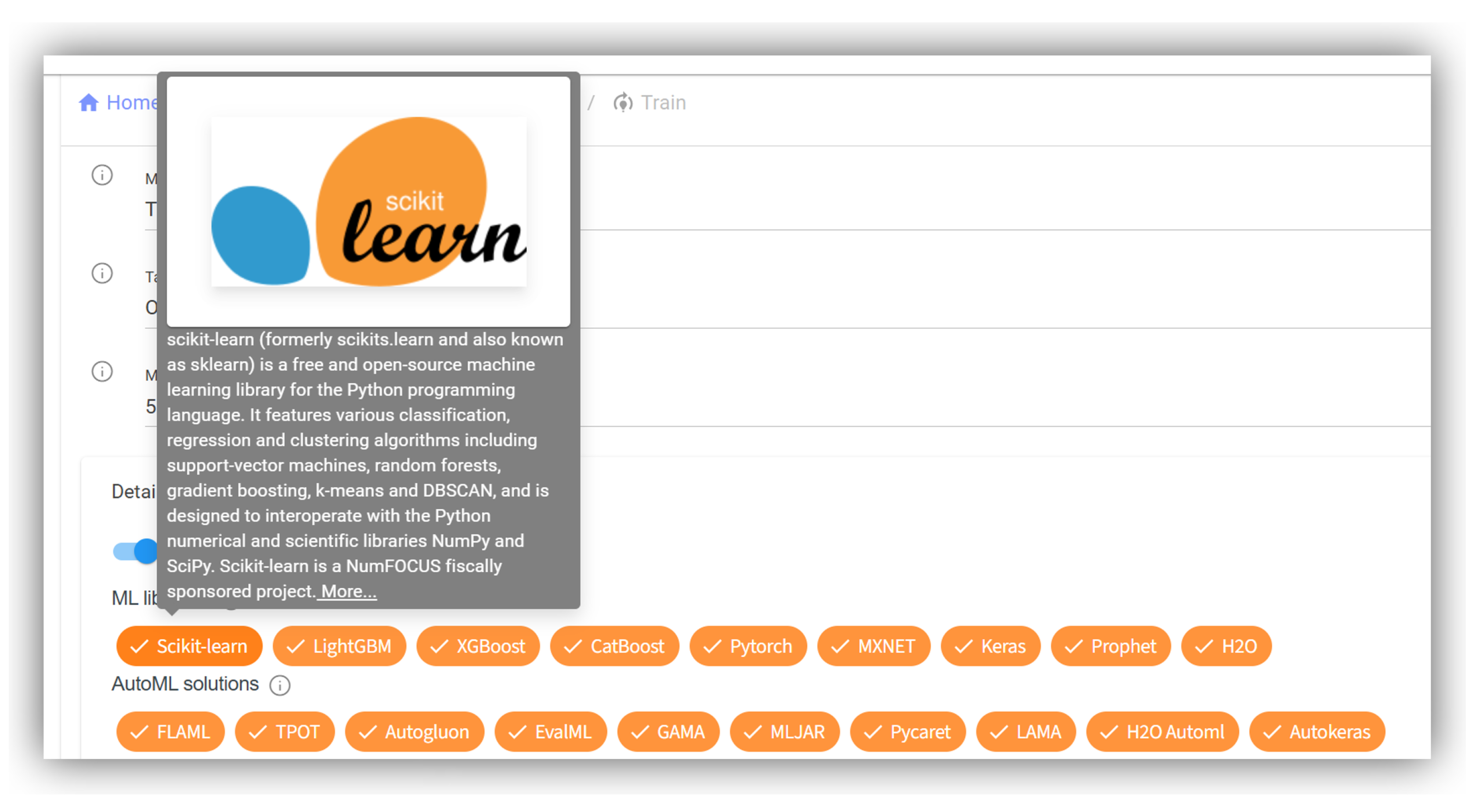

- Interactive help: ML Ontology is used as the information source for the interactive help system of the data science platform, helping users understand complex terminology in machine learning.

2. Related Work

3. Ontology Architecture

3.1. Modelling Approach

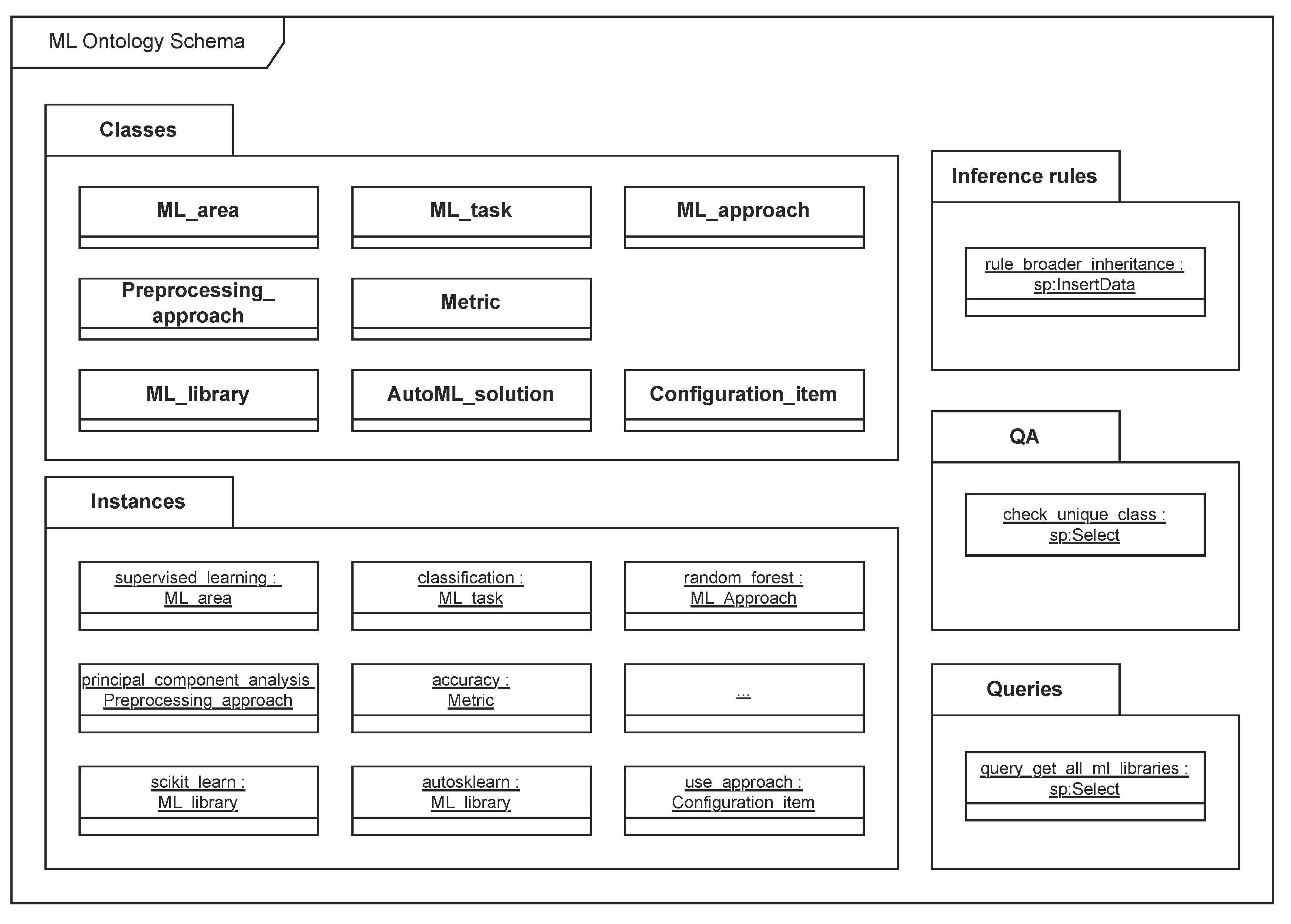

3.2. ML Ontology Schema

- Classes: Definition of all classes and properties to be used in the ontology;

- Instances: Instances of the specified classes with all their properties that model ML concepts and their relationships;

- Inference rules: Forward-chaining inference rules may be applied in a use-case-specific manner to enhance the expressiveness of the ontology;

- QA: Quality assurance (QA) checks can be used in a use-case-specific manner to ensure integrity of the ontology;

- Queries: Sample queries that may be used in applications utilising the ontology.

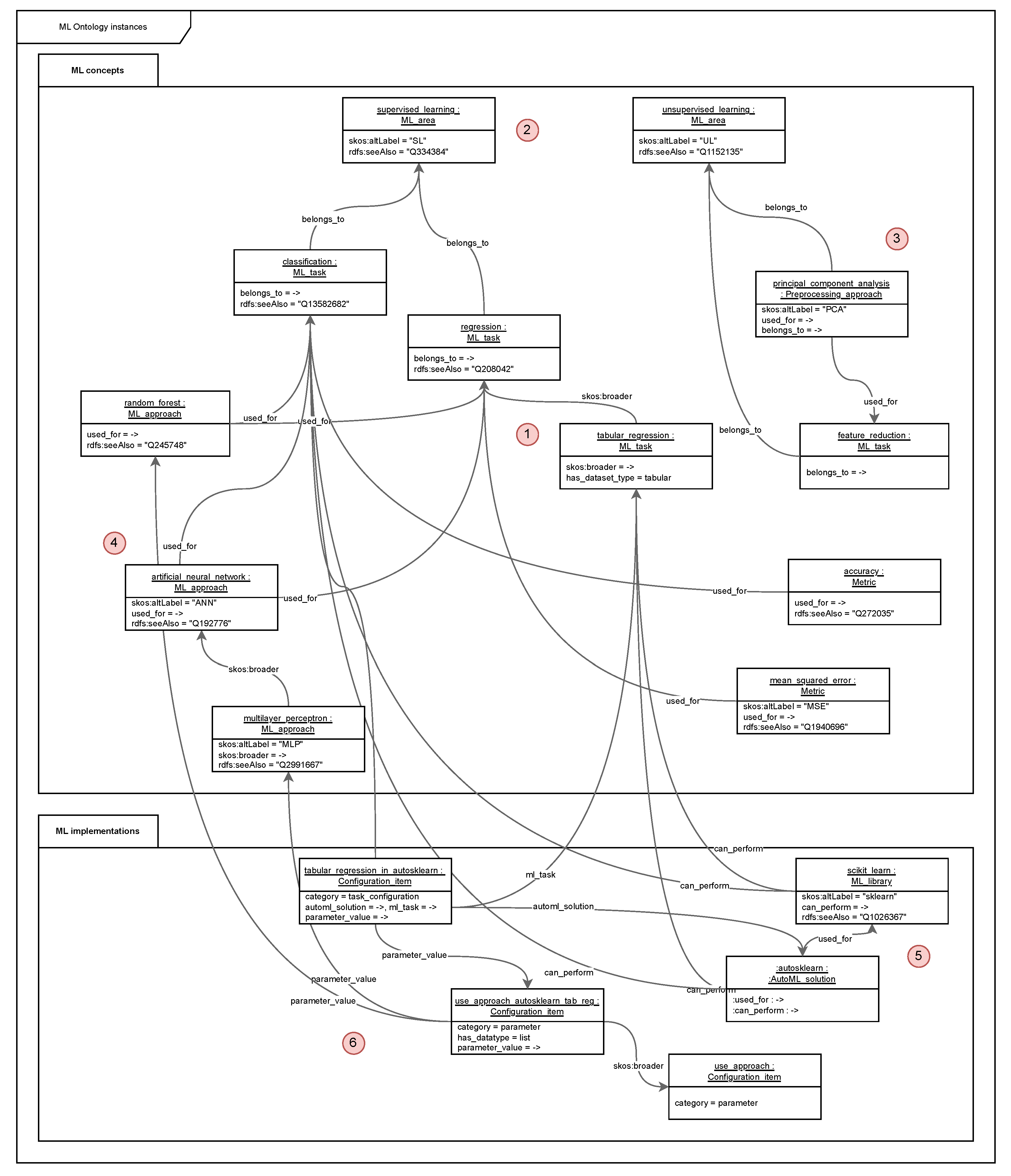

- ML_area with instances for supervised learning, unsupervised learning and reinforcement learning;

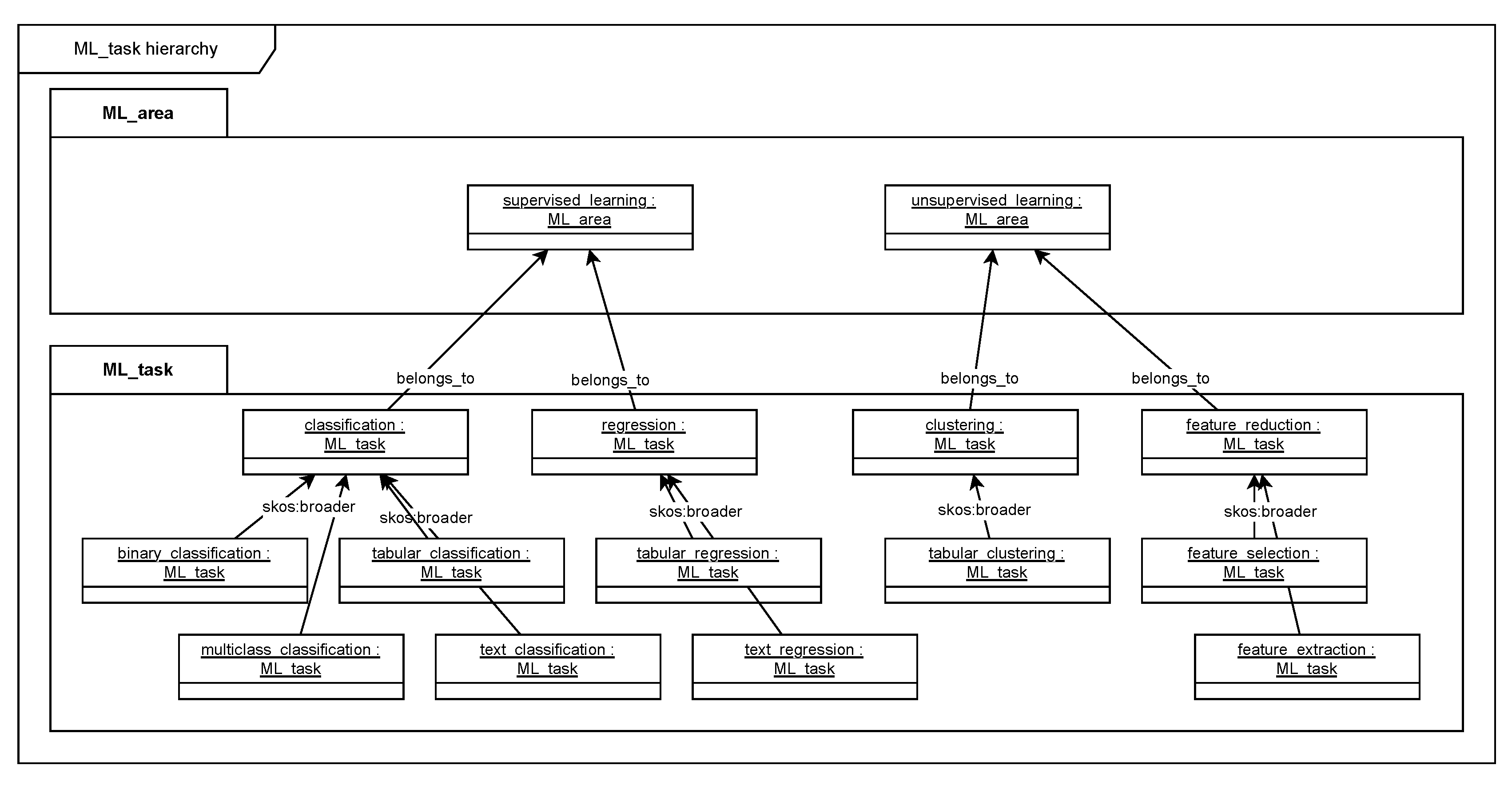

- ML_task with ca. 40 instances, e.g., for classification, regression, and clustering;

- ML_approach with ca. 120 instances, e.g., for artificial neural network, random forest, and support vector machine;

- Preprocessing_approach with ca. 10 instances, e.g., for principal component analysis and kernel approximation;

- Metric with ca. 120 instances, e.g., for accuracy, f-measure and mean squared error;

- ML_library with ca. 30 instances, e.g., for Scikit-learn, Tensorflow, and PyTorch;

- AutoML_solution with ca. 30 instances, e.g., for AutoSklearn, TPOT, and Auto-PyTorch;

- Configuration_item with ca. 240 instances, e.g., for ensemble size, use approach, and metric.

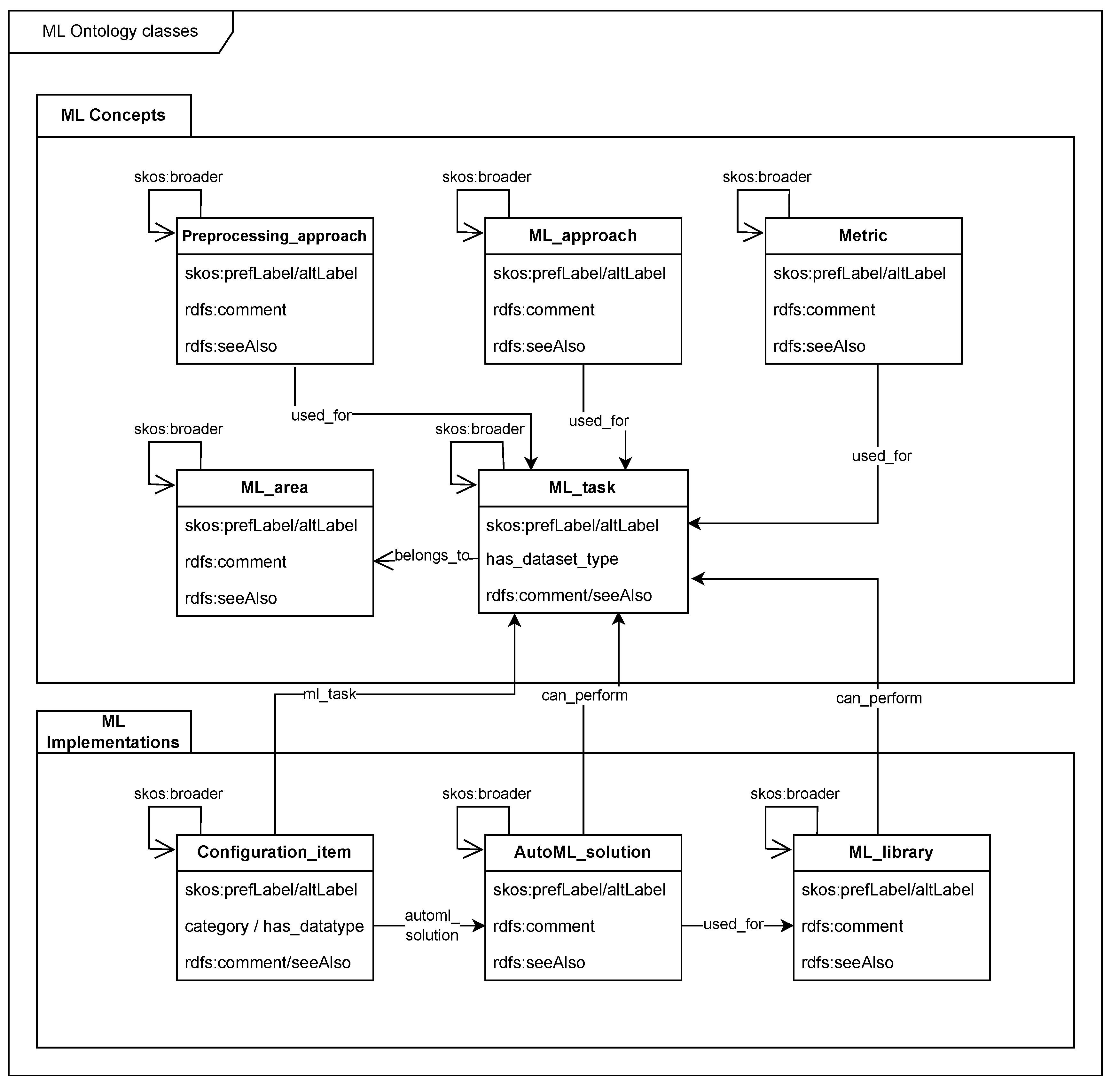

3.3. Ontology Classes

- ML concepts formalise terminology in the ML domain: concepts and their interdependencies;

- ML implementations specify ML libraries, AutoML solutions and their concrete configuration options.

- skos:prefLabel: the preferred label of the individual, e.g., "support vector machine". This label is used for the IRI of the individual, e.g., support_vector_machine;

- skos:altLabel: alternative labels or acronyms, e.g., "SVN";

- rdfs:comment: short description of the individual, e.g., "Set of methods for supervised statistical learning";

- rdfs:seeAlso: ontology linking, e.g., the Wikidata entry for support vector machine <https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q282453https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q282453>.

- used_for links ML approaches, preprocessing approaches and metrics to ML tasks they can be used for, e.g., the ML approach support vector machine can be used for ML tasks classification and regression.

- belongs_to links ML tasks to ML areas, e.g., the ML task classification belongs to the ML area supervised learning.

- can_perform links instances of ML library or AutoML solution to ML tasks, e.g., ML library scikit-learn can perform ML task classification.

- ml_task links configuration items to ML tasks.

- skos:broader is used for modelling taxonomies between instances of the same class, e.g., the broader term of tabular regression is regression.

3.4. Ontology Alignment

3.5. Ontology Instances

3.6. Ontology Queries

3.7. Quality Assurance

- All subjects or objects in RDF triples must be instances of exactly one class.

- All predicates used in RDF triples must be be declared as properties.

3.8. Reasoning

4. Use Cases

4.1. ML Training Configuration Wizard

4.2. Interactive Help

5. Discussion

- Volume: ML Ontology is notably comprehensive, encompassing ca. 700 individuals that define key machine learning concepts. With roughly 5,000 RDF triples, it ranks among the largest domain-specific ontologies for ML that we are aware of. The only ontology for the ML domain comparable in volume is OntoDM with ca 660 classes representing ML concepts, described by ca. 3,700 annotations (AnnotationAssertions, subClassOf relationships, AnnotationProperties, DisjointClasses etc.). The ML Schema Core Specification as an upper-level ontology only specifies 25 classes. According to [4], DMOP includes ca. 720 classes representing ML concepts, described by ca. 4,300 annotations (data properties, logical axioms etc.). However, the ontology does not seem to be publicly available, just like the Exposé ontology for data mining experiments. Finally, the MEX vocabulary comprises ca. 250 classes.

- Performance: ML Ontology allows high-performance query access. A benchmark has been performed to execute SPARQL queries joining several classes with 100+ results (Setup: In-memory SPARQL engine: rdflib 7.1.4, CPU: Intel Core Ultra 7 165H, 3.80 GHz, 32 GB RAM). On average, a SPARQL query executed in 2.9 ms. We consider this fast enough for industry applications.

- Balance between simplicity and expressiveness: ML Ontology deliberately uses lightweight modelling approach (knowledge graph implemented in RDF/RDFS) which is particularly suited for industry use. At the same time, ML ontology offers the full expressive power of SPARQL inference rules that can be used in a use-case-specific manner.

- Extensibility and adaptability: ML Ontology is modularised and can be easily extended and adapted to various use cases. The ontology schema provides a clear separation between classes, instances, inference rules, queries and QA checks (see Figure 1). ML Ontology classes are separated in ML concepts and ML implementations (see Figure 2). ML Ontology has been extended continuously over a period of more than five years and the ontology schema has proven stable.

- Built-in quality management: ML Ontology comprises built-in quality checks that can be adapted use-case-specifically in order to ensure that quality requirements from the industry are met. As opposed to just documenting modelling guidelines, quality checks can be executed regularly, allowing guideline violations to be detected and fixed. ML Ontology has be co-edited by more than 15 knowledge engineers over more than 5 years and still has not deteriorated in quality.

- Standards: ML Ontology is solely based on Semantic Web (SW) standards including RDF/RDFS and SPARQL, and uses state-of-the-art ontology schemas such as SKOS and SPIN. Experiments have shown that ML Ontology can easily be deployed as a Labeled Property Graph (LPG) if needed. ML Ontology could be imported without adaptation into Neo4J and the pre-defined SPARQL queries could be automatically converted to correct Cypher queries.

- Public availability: ML Ontology is published open source26 under an MIT license.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

References

- Gruber, T.R. A translation approach to portable ontology specifications. Knowledge acquisition 1993, 5, 199–220.

- Publio, G.C.; Esteves, D.; Panov, P.; Soldatova, L.; Soru, T.; Vanschoren, J.; Zafar, H.; et al. ML-schema: exposing the semantics of machine learning with schemas and ontologies. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.05351 2018.

- Panov, P.; Soldatova, L.; Džeroski, S. Ontology of core data mining entities. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2014, 28, 1222–1265.

- Keet, C.M.; Ławrynowicz, A.; d’Amato, C.; Kalousis, A.; Nguyen, P.; Palma, R.; Stevens, R.; Hilario, M. The data mining optimization ontology. Journal of web semantics 2015, 32, 43–53.

- Vanschoren, J.; Soldatova, L. Exposé: An ontology for data mining experiments. In Proceedings of the International workshop on third generation data mining: Towards service-oriented knowledge discovery (SoKD-2010), 2010, pp. 31–46.

- Anikin, D.; Borisenko, O.; Nedumov, Y. Labeled property graphs: SQL or NoSQL? In Proceedings of the 2019 Ivannikov Memorial Workshop (IVMEM). IEEE, 2019, pp. 7–13.

- Hogan, A.; Blomqvist, E.; Cochez, M.; d’Amato, C.; Melo, G.D.; Gutierrez, C.; Kirrane, S.; Gayo, J.E.L.; Navigli, R.; Neumaier, S.; et al. Knowledge graphs. ACM Computing Surveys (Csur) 2021, 54, 1–37.

- Humm, B.G.; Archer, P.; Bense, H.; Bernier, C.; Goetz, C.; Hoppe, T.; Schumann, F.; Siegel, M.; Wenning, R.; Zender, A. New directions for applied knowledge-based AI and machine learning: Selected results of the 2022 Dagstuhl Workshop on Applied Machine Intelligence. Informatik Spektrum 2023, 46, 65–78.

- Kifer, M.; Lausen, G. F-logic: a higher-order language for reasoning about objects, inheritance, and scheme. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1989 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data, 1989, pp. 134–146.

- Bense, H.; Humm, B.G. An Extensible Approach to Multi-level Ontology Modelling. In Proceedings of the KMIS, 2021, pp. 184–193.

- Huth, M.; Ryan, M. Logic in Computer Science: Modelling and Reasoning about Systems, 2 ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Zender, A.; Humm, B.G. Ontology-based meta automl. Integrated Computer-Aided Engineering 2022, 29, 351–366.

- Zender, A.; Humm, B.G.; Holzheuser, A. Enhancing User Experience in Artificial Intelligence Systems: A Practical Approach. In Proceedings of the Topical Area: Software, System and Service Engineering (S3E) of the FedCSIS Conference on Computer Science and Intelligence Systems. Springer, 2024, pp. 113–131.

- Humm, B.G.; Zender, A. An ontology-based concept for meta automl. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations. Springer, 2021, pp. 117–128.

- Feurer, M.; Klein, A.; Eggensperger, K.; Springenberg, J.; Blum, M.; Hutter, F. Efficient and Robust Automated Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2015.

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | Although the term knowledge graph has been already used since 1972, the current use of the phrase stems from the 2012 announcement of the Google Knowledge Graph [7] |

| 17 | |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | |

| 21 | |

| 22 | |

| 23 | Namespace <https://www.w3.org/ns/mls#> |

| 24 | |

| 25 | Namespace http://spinrdf.org/spin#

|

| 26 |

| ML Ontology | ML Schema |

|---|---|

| ML_task | Task |

| ML_approach | Algorithm |

| Preprocessing_approach | Algorithm |

| Metric | EvaluationMeasure |

| ML_library | Implementation |

| AutoML_solution | Implementation |

| Configuration_item | HyperParameter |

| Class | Instance | Wikidata ID | Wikidata Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| ML_area | supervised_learning | Q334384 | supervised learning |

| ML_task | classification | Q13582682 | classification |

| ML_approach | artificial_neural_network | Q192776 | artificial neural network |

| Preprocessing_approach | principal_component_analysis | Q2873 | principal component analysis |

| Metric | accuray | Q272035 | accuracy and precision |

| ML_library | scikit_learn | Q1026367 | scikit-learn |

| AutoML_solution | autosklearn | Q120703207 | auto-sklearn |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).