1. Introduction

Arrhythmias are a significant contributor to deaths caused by cardiovascular disease [

1,

2]. A regular heartbeat depends on the coordinated function of cardiomyocytes and the cardiac conduction system. Disruptions in electrical signal generation or transmission can lead to arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities. A broad spectrum of cardiac abnormalities can contribute to arrhythmias, including congenital structural malformations and acquired functional impairments. Additionally, systemic factors such as electrolyte imbalances (particularly hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia), hypoxia, hormonal dysregulation, specific medications, and toxins can trigger or exacerbate arrhythmias [

3].

Troponin I (TnI) is a cytosolic protein localized within the sarcomeric apparatus of cardiomyocytes. It functions as a crucial modulator of cardiac contractility. Myocardial injury triggers the release of TnI into the systemic circulation, leading to a rise in serum TnI concentration. Consequently, serum TnI concentration measurement serves as a cornerstone diagnostic tool for acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Recent advancements have led to the development of hs-cTnI assays. These assays demonstrate improved sensitivity compared to conventional TnI assays, enabling the detection of subtler and earlier stages of myocardial injury [

4]. This enhanced sensitivity holds particular promise in the diagnosis of arrhythmias, where hs-cTnI may reveal previously undetectable evidence of myocardial damage [

5,

6].

Given the paucity of data on this subject within the Asian population, this study aimed to: (1) quantify hs-cTnI levels in patients with arrhythmias and (2) explore the association between hs-cTnI levels and relevant clinical and subclinical factors within this cohort.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design: This investigation employed a cross-sectional design. Participants were recruited at a single point in time during the study period, which spanned from December 2023 to April 2024. The study site was the Arrhythmia Treatment Department of Cho Ray Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Study Population: Participants were recruited consecutively from inpatients admitted to the Arrhythmia Treatment Department of Cho Ray Hospital throughout the study period. To minimize potential confounding factors, patients with the following conditions were excluded: acute myocardial infarction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, takotsubo cardiomyopathy, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 15 ml/min/m2, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, shock of any etiology, and systemic sclerosis. To further explore potential differences in hs-cTnI levels, the study group was divided into subgroups based on arrhythmia type (ventricular vs. non-ventricular) and the presence or absence of coronary artery disease (CAD).

Data Collection: Demographic and anthropometric data, along with clinical and subclinical indicators, were retrieved from patients' medical records. Acute exacerbations of arrhythmias and ventricular arrhythmias were independently confirmed by at least two electrophysiologists through analysis of 12-lead ECG, Holter ECG, and/or electrophysiological study data. The diagnosis of CAD adhered to the established criteria outlined in the 2023 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines [

7].

hs-cTnI Measurement: Blood samples were collected from all participants as soon as possible after enrollment, with a target collection time of within one hour, to quantify hs-cTnI levels alongside other biochemical markers, including creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), creatinine, and complete blood count (CBC). A 3-position sandwich immunoassay with direct luminescence detection technology on the ADVIA Centaur (Siemens) platform was employed for hs-cTnI measurement. This assay boasts a reportable range of 2.50–25,000 pg/mL and demonstrates excellent repeatability and within-laboratory imprecision reliability with coefficients of variation less than 10% and 12%, respectively.

Statistical Analysis: Quantitative data were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as percentages (%). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was employed for comparisons between two independent groups with continuous data. The chi-square test was used to compare proportions between two categorical groups. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was utilized to assess the monotonic relationship between two continuous variables. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.3.1.

Ethical Considerations: This study was granted ethical approval by the Ethics Council in Biomedical Research of University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City. All potential participants were provided with a detailed explanation of the study objectives and methods, and written informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment.

3. Results

A total of 285 patients with arrhythmias were initially recruited for this study. However, twelve participants were excluded due to the following reasons: two with acute myocardial infarction, eight with acute renal failure, one with pneumonia, and one in shock. Therefore, data from 273 patients were ultimately included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study sample.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study sample.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants with Arrhythmias.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants with Arrhythmias.

| |

Total (n=273) |

Male (n=149) |

Female (n=124) |

| Anthropology, Clinical |

| Age (years) |

69 (55-76) |

64 (52-74) |

71 (62-78) |

| Height (m) |

1.60 (1.55-1.65) |

1.65 (1.60-1.67) |

1.55 (1.50-1.58) |

| Weight (kg) |

58 (50-65) |

60 (55-66) |

53 (48.5-60) |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

22.5 (20.7-24.1) |

23.1 (20.9-24.2) |

22.0 (20.0-23.4) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) |

130 (120-140) |

125 (120-140) |

130 (120-140) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) |

74 (70-80) |

75 (70-80) |

78 (70-80) |

| Laboratory Tests |

| HGB (g/L) |

128 (115-138) |

134 (126-144) |

119 (109-129) |

| HCT (%) |

38.3 (35.0-41.3) |

40.1 (37.6-42.8) |

35.6 (30.0-38.6) |

| WBC (G/L) |

8.0 (6.7-10.0) |

8.2 (6.9-9.8) |

7.8 (6.2-10.0) |

| PLT (G/L) |

188 (137-233) |

173 (141-214) |

200 (128-269) |

| INR |

1.05 (1.01-1.13) |

1.06 (1.02-1.14) |

1.04 (1.00-1.11) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) |

0.89 (0.76-1.10) |

0.96 (0.82-1.16) |

0.81 (0.67-0.97) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) |

80.6 (62.3-93.6) |

84.5 (64.5-97.8) |

73.3 (57.7-90.3) |

| Free T4 (pg/mL) |

12.4 (11.2-13.7) |

12.4 (11.2-13.9) |

12.4 (11.2-13.6) |

| TSH (mIU/L) |

1.41 (0.79-2.25) |

1.24 (0.70-2.07) |

1.48 (0.88-2.30) |

| Echocardiography |

| EF (%) |

65 (57-71) |

63 (53-71) |

66 (58-71) |

| EDV (mL) |

102 (84-129) |

108 (89-135) |

97 (78-118) |

| ESV (mL) |

36 (27-52) |

38 (29-61) |

32 (26-43) |

| LVEDD (mm) |

47 (43-52) |

48 (44-53) |

46 (42-50) |

| LVESD (mm) |

30 (27-34) |

31 (28-37) |

29 (26-32) |

A total of 273 patients with arrhythmias were enrolled in the study, with 149 males and 124 females. The median age was 64 years for males and 71 years for females (p < 0.001). Males exhibited greater height, weight, and BMI compared to females (all p < 0.05). While serum creatinine levels were higher in males (p < 0.001), glomerular filtration rate was also significantly higher in males compared to females (p = 0.011). No statistically significant differences were observed in other laboratory markers or echocardiographic parameters between the two groups.

31 participants were diagnosed with ventricular arrhythmias, while 242 had non-ventricular arrhythmias. While both groups exhibited similar anthropometric and clinical characteristics overall, statistically significant differences were observed in leukocyte index and left ventricular ejection fraction (EF). The median leukocyte index was higher in the ventricular arrhythmia group (9.1 G/L) compared to the non-ventricular arrhythmia group (7.8 G/L; p = 0.045). Additionally, the ventricular arrhythmia group demonstrated a lower median EF (55%) compared to the non-ventricular arrhythmia group (66%; p < 0.001).

42 participants were diagnosed with both arrhythmias and coronary artery disease (CAD), while 231 had arrhythmias without CAD. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was lower in the CAD group (median: 69.9 mL/min/1.73 m

2) compared to the non-CAD group (median: 81.8 mL/min/1.73 m

2; p < 0.001). Left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) was also significantly lower in the CAD group (45%) compared to the non-CAD group (66%; p < 0.001). Notably, echocardiographic parameters including end-diastolic volume (EDV), end-systolic volume (ESV), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), and left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD) were all greater in the CAD group compared to the non-CAD group (

Table 2).

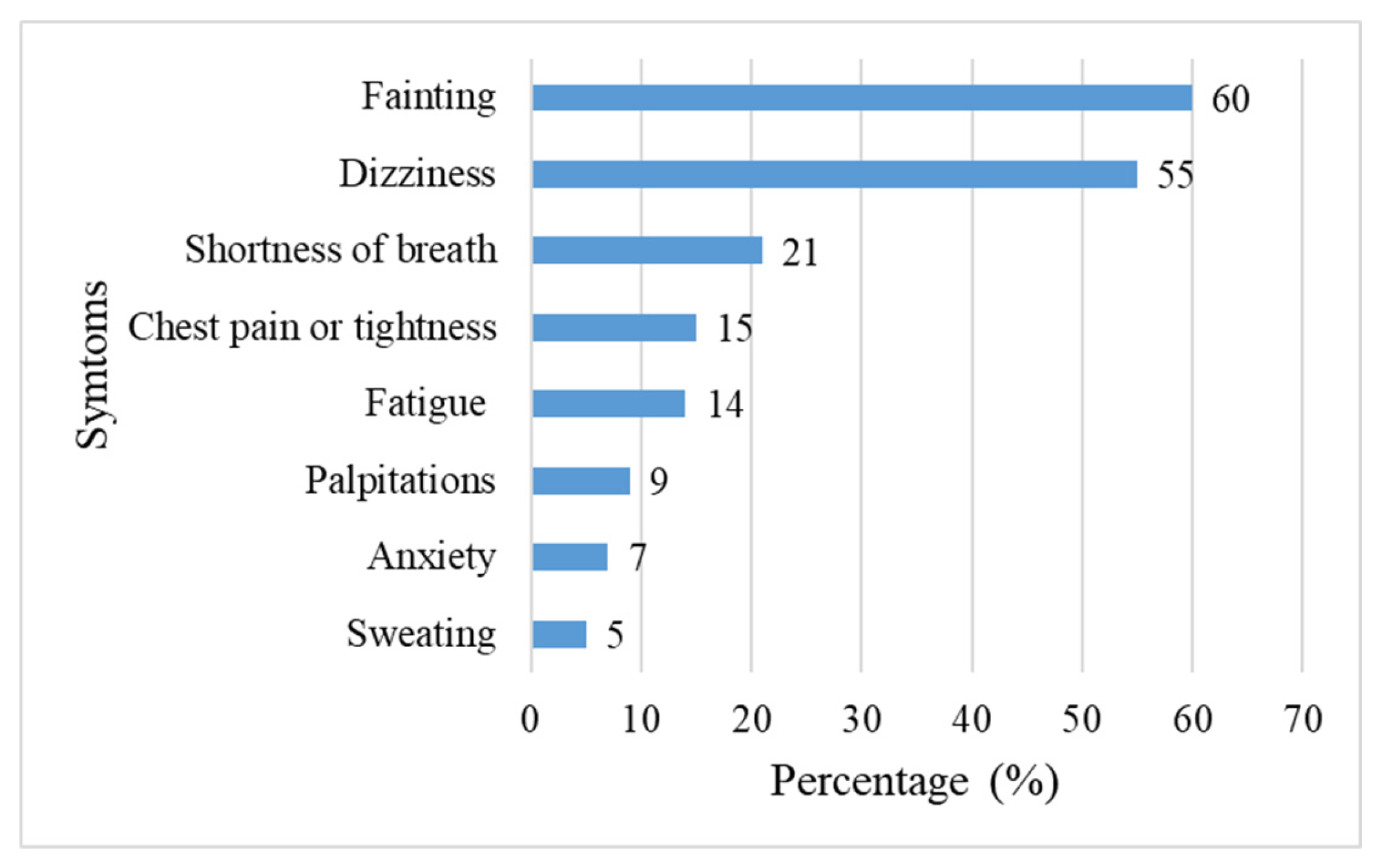

Among the 273 patients with arrhythmias, fainting and dizziness were the most prevalent clinical manifestations, reported by 60% and 55% of participants, respectively. These were followed by shortness of breath, chest pain, fatigue, palpitations, anxiety, and sweating, in descending order of frequency (

Figure 2).

- 2.

hs-cTnI Levels

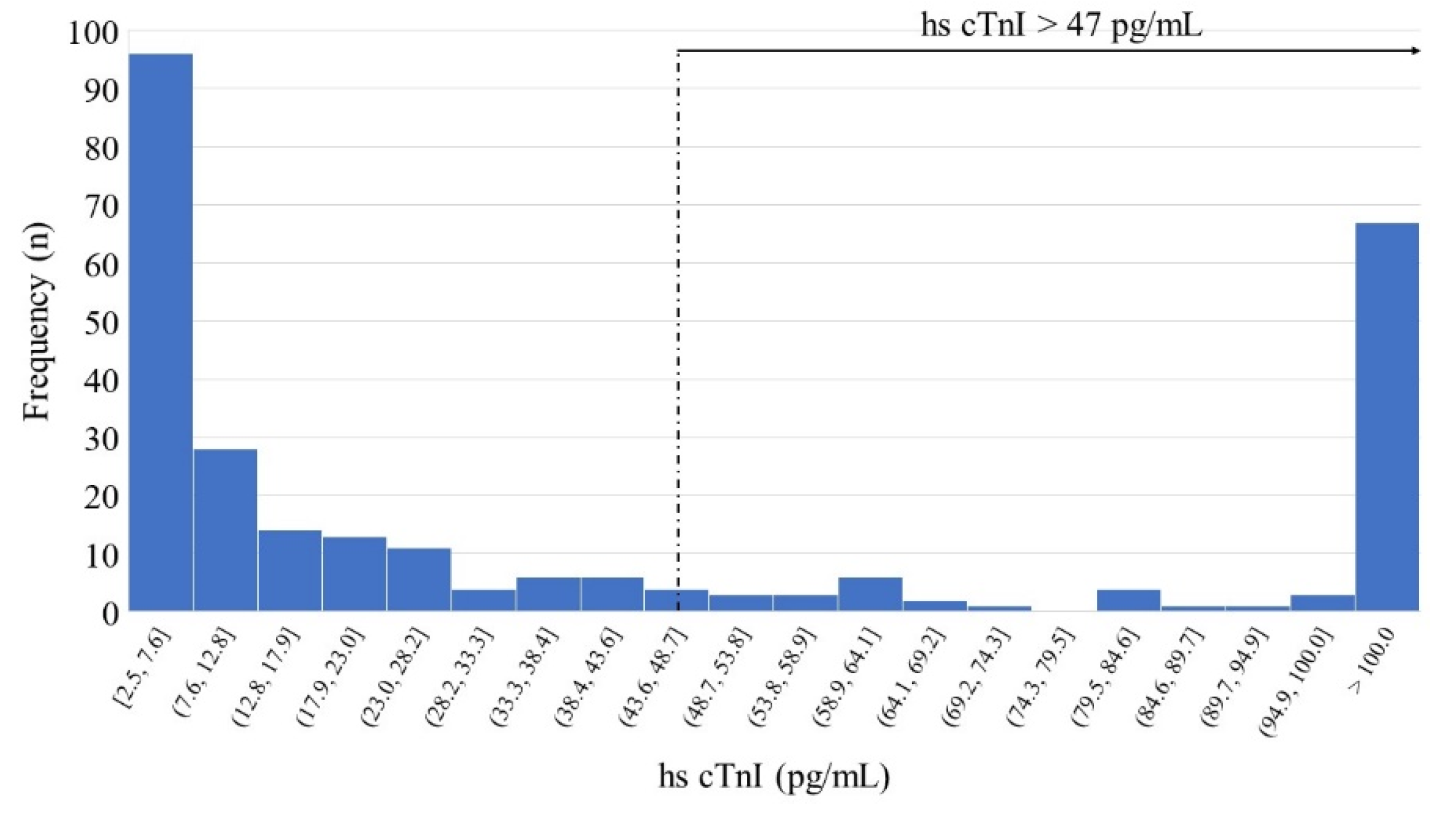

Figure 3.

Distribution of hs-cTnI concentrations in arrhythmia patients (n=273).

Figure 3.

Distribution of hs-cTnI concentrations in arrhythmia patients (n=273).

hs-cTnI concentrations exhibited a median of 17.4 pg/mL (interquartile range: 4.77-97.7 pg/mL) in the study population. The minimum and maximum measured values were 2.5 pg/mL and 15,361 pg/mL, respectively. According to the IFCC recommended reporting format, the 99th percentile in the healthy population is 47 pg/mL. A total of 94 patients (34.4%) in the study had hs-cTnI levels exceeding this reference limit.

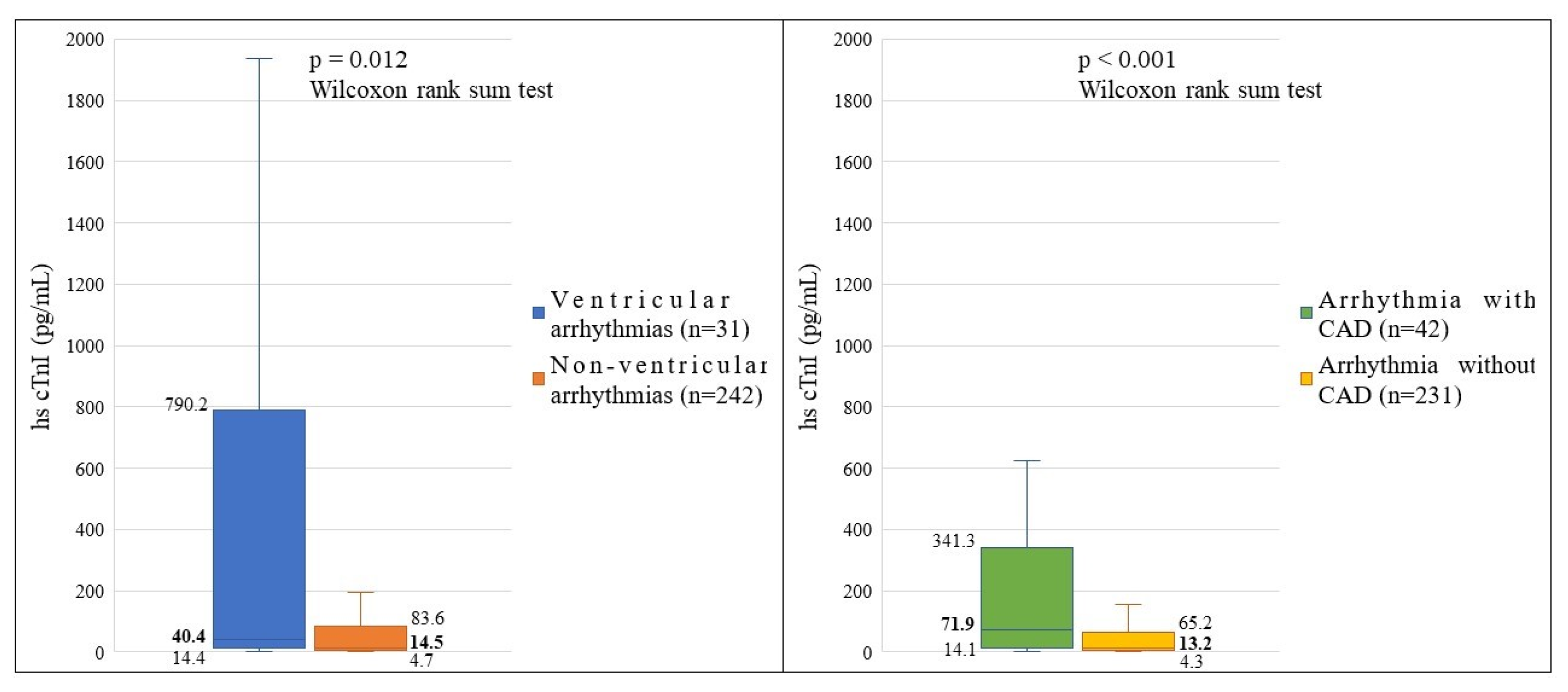

Figure 4.

Comparison of hs-cTnI Levels Across Patient Subgroups.

Figure 4.

Comparison of hs-cTnI Levels Across Patient Subgroups.

Patients diagnosed with ventricular arrhythmias exhibited significantly higher median hs-cTnI concentrations compared to those with non-ventricular arrhythmias (median: 40.4 pg/mL vs. 14.5 pg/mL; p = 0.012, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). hs-cTnI levels were significantly elevated in patients with arrhythmias and co-existing CAD (median: 71.9 pg/mL) compared to those without CAD (median: 13.2 pg/mL; p < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

- 3.

Correlations Between hs-cTnI Levels and Other Variables

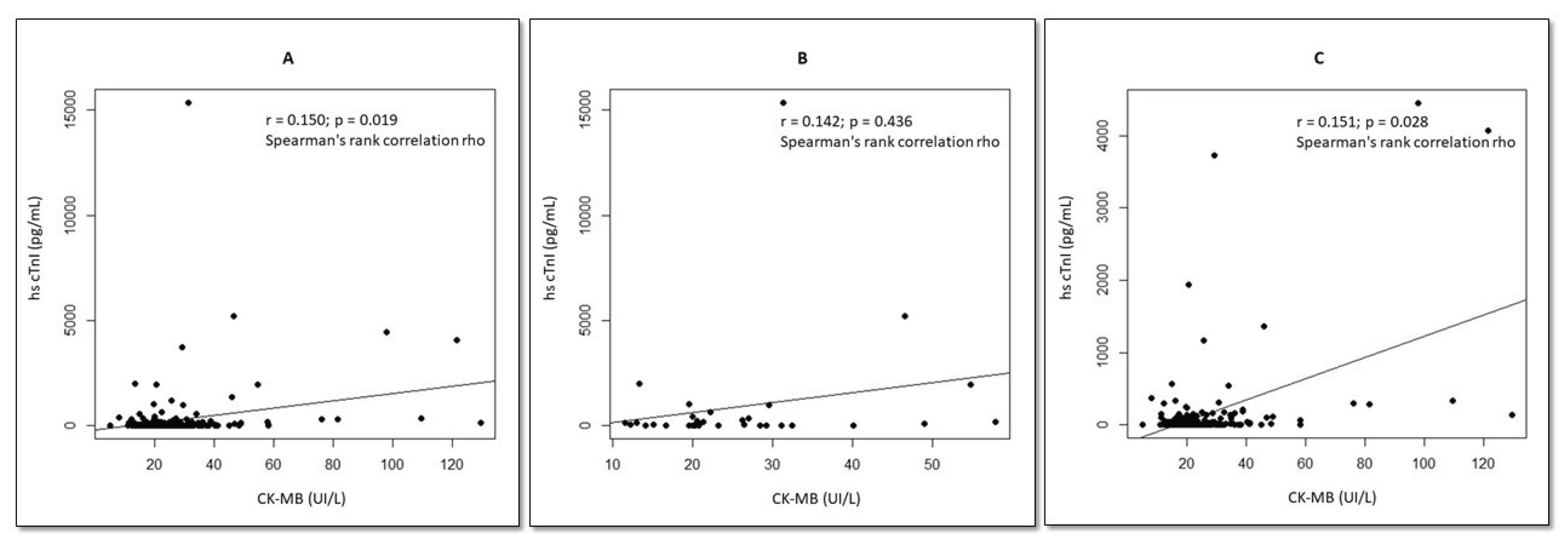

Figure 5.

Correlations Between hs-cTnI and CK-MB Levels in Arrhythmia Subgroups. A: General Group Analysis. B: Arrhythmias with CAD. C: Arrhythmias without CAD.

Figure 5.

Correlations Between hs-cTnI and CK-MB Levels in Arrhythmia Subgroups. A: General Group Analysis. B: Arrhythmias with CAD. C: Arrhythmias without CAD.

A weak but statistically significant positive correlation was observed between hs-cTnI and CK-MB levels in all arrhythmia patients (r = 0.150, p = 0.019). Patients with arrhythmias but without CAD also demonstrated a weak positive correlation between hs-cTnI and CK-MB (r = 0.015, p = 0.028). Interestingly, no statistically significant correlation between hs-cTnI and CK-MB levels was found in patients with arrhythmias and co-existing CAD (p = 0.436).

Table 3.

Associations Between hs-cTnI Levels and Other Variables.

Table 3.

Associations Between hs-cTnI Levels and Other Variables.

| Variable |

Spearman's Rank Correlation rho |

P |

| Age (years) |

0.016 |

0.929 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

0.305 |

0.094 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) |

0.161 |

0.384 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) |

-0,051 |

0.782 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) |

0.509 |

0.003 |

| TSH (mIU/L) |

-0.129 |

0.504 |

| HGB (g/L) |

0.154 |

0.407 |

| WBC (G/L) |

0.548 |

0.001 |

| PLT(G/L) |

0.271 |

0.139 |

| EF (%) |

-0.280 |

0.126 |

| EDV (mL) |

0.336 |

0.068 |

| ESV (mL) |

0.269 |

0.142 |

| LVEDD (mm) |

0.302 |

0.104 |

| LVESD (mm) |

0.353 |

0.059 |

In arrhythmia patients, hs-cTnI concentrations exhibited significant positive correlations with both NT-proBNP (r = 0.509, p = 0.003) and WBC (r = 0.548, p = 0.001).

4. Discussion

TnI is a critical regulatory protein within the sarcomeres of striated muscle, including cardiomyocytes. It plays a vital role in muscle contraction by interacting with other troponin subunits and actin. Following myocardial injury or damage, TnI leaks from the sarcoplasm of cardiomyocytes into the bloodstream. Consequently, elevated blood TnI levels serve as a sensitive and specific marker for myocardial damage [8-10]. Arrhythmias can potentially lead to myocardial injury. Elevated TnI levels are frequently observed in arrhythmia patients, particularly those with severe or complex arrhythmias. This association is likely due to the increased stress placed on the heart muscle during sustained arrhythmic episodes, which can lead to cellular injury and subsequent TnI release [11-13]. This study investigated hs-cTnI concentrations in a cohort of arrhythmia patients (n = 273) recruited from the arrhythmia treatment department of Cho Ray Hospital. The initial analysis included 285 patients, but 12 were excluded. The median hs-cTnI level in the study population was 17.4 pg/mL (interquartile range: 4.77-97.7 pg/mL). Notably, hs-cTnI concentrations were significantly higher in patients with ventricular arrhythmias compared to those with non-ventricular arrhythmias. Similarly, patients with co-existing CAD demonstrated elevated hs-cTnI levels compared to those without CAD. Furthermore, hs-cTnI levels exhibited a weak but statistically significant correlation with CK-MB, and strong positive correlations with both NT-proBNP and WBC.

It is crucial to interpret our findings within the context of existing research. Our study aligns with previous investigations demonstrating generally elevated hs-cTnI concentrations in arrhythmia patients compared to the healthy population [14-17]. This study observed elevated hs-cTnI concentrations in patients with ventricular arrhythmias compared to those with non-ventricular arrhythmias. These findings are consistent with previous research on patients suffering from various cardiovascular diseases, which have also reported associations between elevated hs-cTnI levels and arrhythmias [

5,

18,

19]. Our findings support the notion that hs-cTnI concentrations are elevated in arrhythmia patients with co-existing coronary artery disease compared to those without coronary artery disease. This observation aligns with previous research suggesting a potential link between coronary artery disease severity and hs-cTnI levels in patients with arrhythmias [

11,

20]. Consistent with prior investigations, our study observed statistically significant correlations between hs-cTnI and other biomarkers: CK-MB, NT-proBNP, and WBC [

21].

A study by Anja Wiedswang Horjen et al. investigated hs-cTnI concentrations in patients with atrial fibrillation. They reported a median hs-cTnI level of 5.2 pg/mL (interquartile range: 3.8-8.5 pg/mL) [

22]. It is important to consider this in the context of our own findings on arrhythmia and hs-cTnI levels. Atrial fibrillation, unlike some other arrhythmias, may not be strongly associated with significant myocardial injury. Therefore, the hs-cTnI levels reported in the study by Horjen et al. might be lower than those observed in our study population with a broader range of arrhythmia diagnoses.

Patients with ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) exhibit higher hs-cTnI concentrations compared to those with non-ventricular arrhythmias (NVAs). This phenomenon can be attributed to several potential mechanisms. VAs, particularly ventricular tachycardia (VT), are characterized by abnormal electrical impulses originating in the ventricles. These disrupt the normal coordinated contraction of the heart muscle, leading to two main consequences: myocardial ischemia and myocardial irritation [

23,

24]. When the heart muscle contracts inefficiently, it may not receive an adequate blood supply, resulting in ischemia. The abnormal electrical activity and forceful contractions can directly irritate the heart muscle cells. Both myocardial ischemia and irritation can damage heart muscle cells. When these cells are damaged, they leak hs-cTnI into the bloodstream, explaining the higher hs-cTnI levels observed in VA patients [

25]. While NVAs (e.g., atrial fibrillation) typically cause less direct myocardial injury than VTs, some exceptions exist. Prolonged episodes of NVAs like atrial fibrillation or sustained supraventricular tachycardia can contribute to the development of heart failure [

26]. In turn, heart failure can lead to myocardial ischemia and subsequent hs-cTnI release.

Elevated hs-cTnI concentrations observed in patients with arrhythmias and co-existing CAD can be attributed to several interacting mechanisms. Firstly, CAD narrows coronary arteries, limiting blood flow and oxygen delivery to the heart muscle, creating a state of ischemia. Arrhythmias, particularly in patients with pre-existing CAD, further increase myocardial oxygen demand. This heightened mismatch between oxygen supply and demand can exacerbate ischemia, leading to damage or death of cardiomyocytes. Damaged or dying cells release hs-cTnI into the bloodstream, contributing to the observed elevation [

25,

27]. Secondly, arrhythmias themselves may induce inflammation and necrosis within the already ischemic environment created by CAD [

28]. This inflammatory response and cell death can further elevate hs-cTnI levels. The presence of CAD increases the vulnerability of cardiomyocytes to arrhythmia-induced inflammation and necrosis due to the compromised blood supply [

27,

28]. Finally, both arrhythmias and CAD can independently contribute to heart failure, a condition where the heart's pumping capacity weakens. Heart failure, in turn, can lead to global myocardial ischemia, further compromising oxygen delivery to the entire heart muscle. This widespread ischemia can trigger widespread cell damage and hs-cTnI release, explaining the elevated hs-cTnI levels observed in arrhythmia patients with CAD [

26,

29]. Notably, the presence of CAD increases the risk of arrhythmia-induced heart failure due to the pre-existing weakening of the heart muscle [

30,

31].

Our study identified a weak but statistically significant correlation between hs-cTnI and CK-MB concentrations in patients with arrhythmias. However, this correlation became non-significant within the subgroup of patients with both arrhythmias and CAD. This observation can be attributed to the interplay of several factors. First, pre-existing myocardial damage in CAD patients may lead to a chronically elevated baseline hs-cTnI level [

28,

32]. This high background level can obscure any incremental rise in hs-cTnI due to arrhythmias, weakening the observed correlation between the two markers. Second, CAD itself can compromise blood flow to the heart muscle, hindering the release of CK-MB even if arrhythmias trigger ischemic injury [

4,

15,

33]. Additionally, arrhythmias can induce ineffective heart contractions leading to microscopic damage and hs-cTnI release without significant cell death (minimal CK-MB increase) [

25,

31]. The combined effect of these factors - elevated hs-cTnI baseline due to CAD and potentially reduced CK-MB release - can diminish or even abolish the correlation between these biomarkers in patients with both arrhythmias and CAD.

Arrhythmias can contribute to a vicious cycle that elevates both hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP levels. The abnormal electrical activity can directly lead to myocardial ischemia, particularly when coupled with the increased oxygen demand of the struggling heart muscle. This ischemia can cause damage to cardiomyocytes, triggering the release of hs-cTnI into the bloodstream as a marker of cellular injury. NT-proBNP, on the other hand, serves as a signature of ventricular dysfunction. Its secretion is induced by ventricular dilatation and weakening, both of which can be consequences of long-standing arrhythmias, especially in patients with pre-existing heart disease [

34]. Heart failure, a potential long-term outcome of arrhythmias, further exacerbates the situation. It weakens the heart's pumping function, hindering ventricular relaxation and increasing diastolic pressure within the ventricles [

26,

30]. This hemodynamic stress is the primary driver of elevated NT-proBNP levels. In essence, ischemic myocardial injury caused by arrhythmias and arrhythmia-induced heart failure can promote each other, creating a self-perpetuating cycle that manifests as elevated hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP levels [

19,

34,

35].

Arrhythmias can contribute to a complex interplay between inflammation and leukocyte response. The abnormal electrical activity may trigger systemic inflammation through the release of inflammatory mediators. This systemic inflammation can activate the immune system, leading to an elevated peripheral white blood cell count [

36,

37]. Additionally, myocardial injury, whether due to ischemia or other causes triggered by arrhythmias, can induce a localized inflammatory response, attracting leukocytes to the damaged area [

38]. Heart failure, a potential consequence of chronic arrhythmias, can further exacerbate this process. It can cause tissue ischemia, which in turn, triggers an inflammatory response and subsequent leukocytosis [

37,

39]. This interplay between systemic inflammation and myocardial damage becomes a potential vicious cycle in arrhythmia patients. The inflammatory response can contribute to further myocardial injury by releasing inflammatory and oxidative molecules. This ongoing damage, as detected by hs-cTnI release, can perpetuate the inflammatory response and leukocyte activation, explaining the observed correlation between hs-cTnI and WBC levels in patients with arrhythmias [

40,

41].

This study aims to contribute novel insights into hs-cTnI levels in a population of arrhythmia patients encompassing a broad spectrum of arrhythmia subtypes. The relative homogeneity of the Vietnamese population, characterized by minimal Eurasian admixture, minimizes the potential confounding effect of ethnicity on the study's findings. Additionally, the hs-cTnI measurement employed in this study utilizes a 3-position sandwich immunoassay leveraging ADVIA Centaur TNIH direct luminescence chemical technology, ensuring high sensitivity and accuracy in hs-cTnI detection.

Our study acknowledges several limitations. First, the sample size, particularly after subgroup analysis, might be underpowered to detect statistically significant associations. Second, the cross-sectional design precludes establishing causality between risk factors and hs-cTnI levels. Additionally, the study design may not fully account for all potential confounders, such as age, gender, comorbidities, and medication use. Selection bias, inherent to single-center, hospital-based studies, might also limit generalizability. While consecutive sampling was employed, the possibility of non-representative enrollment cannot be entirely excluded. Finally, the exclusively Southern Vietnamese population restricts the study's external validity, potentially limiting the applicability of findings to arrhythmia patients in other geographic regions.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates elevated hs-cTnI levels in a majority of patients with cardiac arrhythmias. Notably, hs-cTnI concentrations were further accentuated in patients with ventricular arrhythmias and those with co-existing CAD. A weak correlation was observed between hs-cTnI and CK-MB, while a statistically significant and strong correlation emerged between hs-cTnI and both NT-proBNP and WBC counts. These findings suggest potential links between myocardial injury, heart failure, and inflammation in patients with arrhythmias.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H.K.D. and N.V.L.; methodology, L.H.K.D.; formal analysis, V.T.T.; investigation, L.H.K.D. and V.T.T.; resources, L.H.K.D.; data curation, V.T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.H.K.D.; writing—review and editing, N.V.L. and V.T.T.; supervision, N.V.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Council in Biomedical Research of University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (approval number 806/HDDD-DHYD on September 22, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City and Cho Ray Hospital for their support and resources throughout this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AHA |

American Heart Association |

| AMI |

Acute Myocardial Infarction |

| CAD |

Coronary Artery Disease |

| CBC |

Complete Blood Count |

| CK-MB |

Creatine Kinase-MB |

| EDV |

End Diastolic Volume |

| EF |

Ejection Fraction |

| ESV |

End Systolic Volume |

| hs-cTnI |

High-sensitivity Cardiac Troponin I |

| LVEDD |

Left Ventricular End Diastolic Diameter |

| LVESD |

Left Ventricular End Systolic Diameter |

| NVAs |

Non-ventricular Arrhythmias |

| VAs |

Ventricular Arrhythmias |

| VT |

Ventricular Tachycardia |

References

- Srinivasan, N.T.; Schilling, R.J. Sudden Cardiac Death and Arrhythmias. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2018, 7, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, M.; Shimizu, W.; Albert, C.M. The spectrum of epidemiology underlying sudden cardiac death. Circ Res 2015, 116, 1887–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, D.S.; Hajouli, S. Arrhythmias. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Said Hajouli declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies., 2024.

- Zainal, H. Understanding Troponin as a Biomarker of Myocardial Injury: Where the Path Crosses with Cardiac Imaging. Cardiology 2023, 148, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariathas, M.; Gemmell, C.; Olechowski, B.; Nicholas, Z.; Mahmoudi, M.; Curzen, N. High sensitivity troponin in the management of tachyarrhythmias. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2018, 19, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.P.; Yousuf, O.; Alonso, A.; Selvin, E.; Calkins, H.; McEvoy, J.W. High-Sensitivity Troponin as a Biomarker in Heart Rhythm Disease. Am J Cardiol 2017, 119, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.S.; Newby, L.K.; Arnold, S.V.; Bittner, V.; Brewer, L.C.; Demeter, S.H.; Dixon, D.L.; Fearon, W.F.; Hess, B.; Johnson, H.M.; et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2023, 148, e9–e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, M.; Kerndt, C.C.; Sharma, S. Troponin. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Connor Kerndt declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Sandeep Sharma declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies., 2024.

- Kumar, D.A.; Muneer, D.K.; Qureshi, D.N. Relationship between high sensitivity troponin I and clinical outcomes in non-acute coronary syndrome (non-ACS) acute heart failure patients - a one-year follow-up study. Indian Heart J 2024, 76, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, I. Highly sensitive troponin I assay in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease in patients with suspected stable angina. World J Cardiol 2021, 13, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandorski, D.; Holtgen, R.; Wieczorek, M.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Bogossian, H.; Iliodromitis, K. Evaluation of troponin I serum levels in patients with arrhythmias with and without coronary artery disease. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed 2024, 119, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalstieg-Bahr, K.; Gladstone, D.J.; Hummers, E.; Suerbaum, J.; Healey, J.S.; Zapf, A.; Koster, D.; Werhahn, S.M.; Wachter, R. Biomarkers for predicting atrial fibrillation: An explorative sub-analysis of the randomised SCREEN-AF trial. Eur J Gen Pract 2024, 30, 2327367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.P.; Arcilla, L.; Wang, S.; Lee, M.S.; Shannon, K.M. Characterization of Cardiac Troponin Elevation in the Setting of Pediatric Supraventricular Tachycardia. Pediatr Cardiol 2016, 37, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.D. Higher sensitivity troponin levels in the community: what do they mean and how will the diagnosis of myocardial infarction be made? Am Heart J 2010, 159, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costabel, J.P.; Burgos, L.M.; Trivi, M. The Significance Of Troponin Elevation In Atrial Fibrillation. J Atr Fibrillation 2017, 9, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, G.V.; Hirsch, G.A.; Spragg, D.D.; Cai, J.X.; Cheng, A.; Ziegelstein, R.C.; Marine, J.E. Prognostic significance of cardiac troponin I levels in hospitalized patients presenting with supraventricular tachycardia. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010, 89, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, K.M.; Johnston, N.; Lind, L.; Venge, P.; Lindahl, B. Cardiac troponin I levels in an elderly population from the community--The implications of sex. Clin Biochem 2015, 48, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Shen, L.; Tu, B.; Hu, Z.; Hu, F.; Zheng, L.; Ding, L.; Fan, X.; Yao, Y. Correlations between cardiac troponin I and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol 2020, 43, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocak, T.; Erdem, A.; Duran, A.; Tekelioglu, U.Y.; Ozturk, S.; Ayhan, S.S.; Ozlu, M.F.; Tosun, M.; Kocoglu, H.; Yazici, M. The diagnostic significance of NT-proBNP and troponin I in emergency department patients presenting with palpitations. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013, 68, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebi, R.; Jackson, L.; McCarthy, C.P.; Murtagh, G.; Murphy, S.P.; Abboud, A.; Miksenas, H.; Gaggin, H.K.; Januzzi, J.L., Jr. Relation of High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin I and Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease in Patients Without Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol 2022, 173, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horjen, A.W.; Ulimoen, S.R.; Norseth, J.; Svendsen, J.H.; Smith, P.; Arnesen, H.; Seljeflot, I.; Tveit, A. High-sensitivity troponin I in persistent atrial fibrillation - relation to NT-proBNP and markers of inflammation and haemostasis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2018, 78, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horjen, A.W.; Ulimoen, S.R.; Enger, S.; Norseth, J.; Seljeflot, I.; Arnesen, H.; Tveit, A. Troponin I levels in permanent atrial fibrillation-impact of rate control and exercise testing. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2016, 16, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedeva, V.K.; Klitcenko, O.A.; Lebedev, D.S.; Lyubimtseva, T.A. Ventricular tachycardia prediction in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2019, 19, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, S.S.; Reinier, K.; Uy-Evanado, A.; Chugh, H.S.; Elashoff, D.; Young, C.; Salvucci, A.; Jui, J. Prediction of Sudden Cardiac Death Manifesting With Documented Ventricular Fibrillation or Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2022, 8, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, J.; Ortengren, A.R.; Zeitler, E.P. Arrhythmias After Acute Myocardial Infarction. Yale J Biol Med 2023, 96, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Calvo, S.; Roca-Luque, I.; Althoff, T.F. Management of Ventricular Arrhythmias in Heart Failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2023, 20, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, R.R.; Gajurel, R.M.; Shah, S.; Poudel, C.M.; Shrestha, H.; Devkota, S.; Thapa, S. Arrhythmias: Its Occurrence, Risk Factors, Therapy, and Prognosis in Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2023, 21, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severino, P.; D'Amato, A.; Pucci, M.; Infusino, F.; Adamo, F.; Birtolo, L.I.; Netti, L.; Montefusco, G.; Chimenti, C.; Lavalle, C.; et al. Ischemic Heart Disease Pathophysiology Paradigms Overview: From Plaque Activation to Microvascular Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessiere, F.; Mondesert, B.; Chaix, M.A.; Khairy, P. Arrhythmias in adults with congenital heart disease and heart failure. Heart Rhythm O2 2021, 2, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoureshi, P.; Tan, A.Y.; Koneru, J.; Ellenbogen, K.A.; Kaszala, K.; Huizar, J.F. Arrhythmia-Induced Cardiomyopathy: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 83, 2214–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond-Paquin, A.; Nattel, S.; Wakili, R.; Tadros, R. Mechanisms and Clinical Significance of Arrhythmia-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Can J Cardiol 2018, 34, 1449–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, D.R.; Lazar, F.L.; Homorodean, C.; Cainap, C.; Focsan, M.; Cainap, S.; Olinic, D.M. High-Sensitivity Troponin: A Review on Characteristics, Assessment, and Clinical Implications. Dis Markers 2022, 2022, 9713326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomanova, Z.; Ohnewein, B.; Schernthaner, C.; Hofer, K.; Pogoda, C.A.; Frommeyer, G.; Wernly, B.; Brandt, M.C.; Dieplinger, A.M.; Reinecke, H.; et al. Classic and Novel Biomarkers as Potential Predictors of Ventricular Arrhythmias and Sudden Cardiac Death. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novack, M.L.; Zubair, M. Natriuretic Peptide B Type Test. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Muhammad Zubair declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies., 2024.

- Sandoval, Y.; Jaffe, A.S. The Evolving Role of Cardiac Troponin: From Acute to Chronic Coronary Syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 82, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzerini, P.E.; Abbate, A.; Boutjdir, M.; Capecchi, P.L. Fir(e)ing the Rhythm: Inflammatory Cytokines and Cardiac Arrhythmias. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2023, 8, 728–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Yu, L.; Tang, J.; Zhou, S. The Role of Cardiac Macrophage and Cytokines on Ventricular Arrhythmias. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluijmert, N.J.; Atsma, D.E.; Quax, P.H.A. Post-ischemic Myocardial Inflammatory Response: A Complex and Dynamic Process Susceptible to Immunomodulatory Therapies. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 647785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, E.C.; Vazquez-Garza, E.; Yee-Trejo, D.; Garcia-Rivas, G.; Torre-Amione, G. What Is the Role of the Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Heart Failure? Curr Cardiol Rep 2020, 22, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Sonel, A.F.; Kelley, M.E.; Wall, L.; Whittle, J.; Fine, M.J.; Good, C.B. Effect of both elevated troponin-I and peripheral white blood cell count on prognosis in patients with suspected myocardial injury. Am J Cardiol 2005, 95, 970–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.L.; Chen, C.M.; Gu, P.W.; Ho, H.Y.; Chiu, D.T. Elevated levels of myeloperoxidase, white blood cell count and 3-chlorotyrosine in Taiwanese patients with acute myocardial infarction. Clin Biochem 2008, 41, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).