Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample Description

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Setup

2.3. Measurement Procedure and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Model Equations

RSSIi+β2 Batteryi+β3 OSi+β4 Modeli+β5 QueueDepthi

RSSIi+β2 Batteryi+β3 OSi+β4 Modeli+β5 QueueDepthi

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. End-to-End Latency, Loss, and Tail Behavior

3.2. Factor Effects and Model Interpretation

3.3. Cross-Platform Schema, Fault Grouping, and Triage

3.4. Energy, Overhead, and Limits

4. Conclusion

References

- See, K.W.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, L.; Gu, X.; Zhang, N.; Lim, K.C.; Zhao, L.; Xie, B. Critical review and functional safety of a battery management system for large-scale lithium-ion battery pack technologies. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Fuzzy Legal Evaluation in Telehealth via Structured Input and BERT-Based Reasoning. 2025 IEEE International Conference on eScience (eScience). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 309–310.

- Ibrahim, A. , & Hugo, W. (2025). Designing Mobile Applications to Facilitate Citizen Information Sharing with the Police: Proposing Design Recommendations to Streamline Communication and Emergency Response Measures.

- Sun, X.; Meng, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, Q. Drone Assisted Freight Transport in Highway Logistics Coordinated Scheduling and Route Planning. 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ChinaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1254–1257.

- Tsukada, M.; Kondo, M.; Matsutani, H. A Neural Network-Based On-device Learning Anomaly Detector for Edge Devices. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2020, PP, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. , Yuan, M., Han, Z., Faircloth, B., Anderson, J. S., King, N., & Stuart-Smith, R. (2022). Smart branching. In Hybrids and Haecceities-Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference of the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture, ACADIA 2022 (pp. 90-97). ACADIA.

- Edwards, J.; Petricek, T.; van der Storm, T.; Litt, G. Schema Evolution in Interactive Programming Systems. Art, Sci. Eng. Program. 2024, 9, 2–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

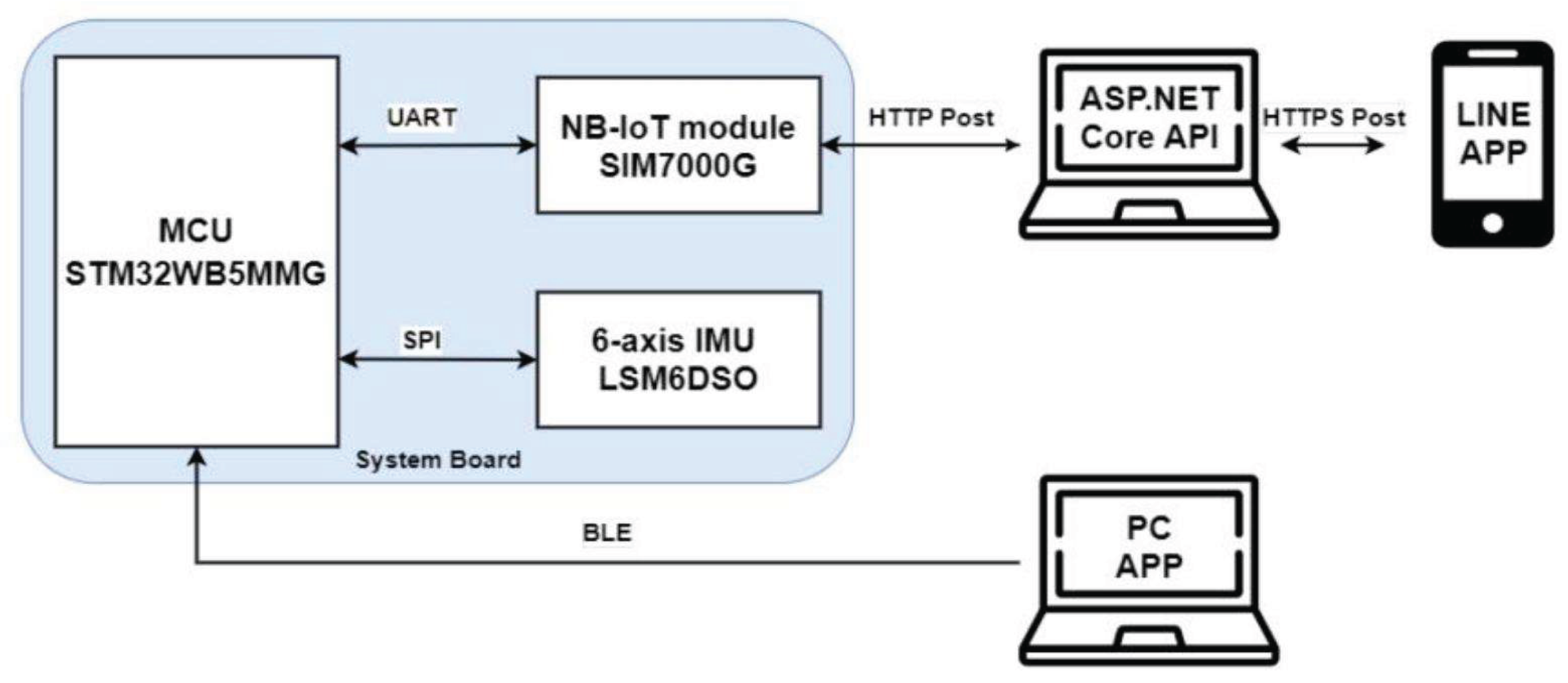

- Wu, C. , Chen, H., Zhu, J., & Yao, Y. (2025). Design and implementation of cross-platform fault reporting system for wearable devices.

- Baldassano, C.; Hasson, U.; Norman, K.A. Representation of Real-World Event Schemas during Narrative Perception. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 9689–9699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z. Traffic Density Road Gradient and Grid Composition Effects on Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption and Emissions. Innov. Appl. Eng. Technol. 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J. W. (2018). Flexible models for understanding and optimizing complex populations (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

- Wu, Q. , Shao, Y., Wang, J., & Sun, X. (2025). Learning Optimal Multimodal Information Bottleneck Representations. arXiv:2505.19996.

- Buyya, R.; Ilager, S.; Arroba, P. Energy-efficiency and sustainability in new generation cloud computing: A vision and directions for integrated management of data centre resources and workloads. Software: Pr. Exp. 2023, 54, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigani, D. , van Kan, D., Tennakoon, G., Geng, L., & Chan, M. (2024, June).

- Embodied Carbon of Buildings: A Review of Methodologies and Benchmarking Towards Net Zero. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 1363, No. Embodied Carbon of Buildings: A Review of Methodologies and Benchmarking Towards Net Zero. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 1363, No. 1, p. 012030). IOP Publishing.

- Huang, Y.; Vu, M.; He, W.; Zeng, S. Rapid Attitude Controller Design Enabled by Flight Data. ASME Lett. Dyn. Syst. Control. 2024, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liang, H.; Yue, L.; Xu, G.; Li, S. Low-Power Acceleration Architecture Design of Domestic Smart Chips for AI Loads. 2025 6th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application (ICCEA). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ChinaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–4.

- Makhijani, K.; Kataria, B.; D, S.; Devkota, D.; Tahiliani, M.P. TinTin: Tiny In-Network Transport for High Precision INdustrial Communication. 2022 IEEE 30th International Conference on Network Protocols (ICNP). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

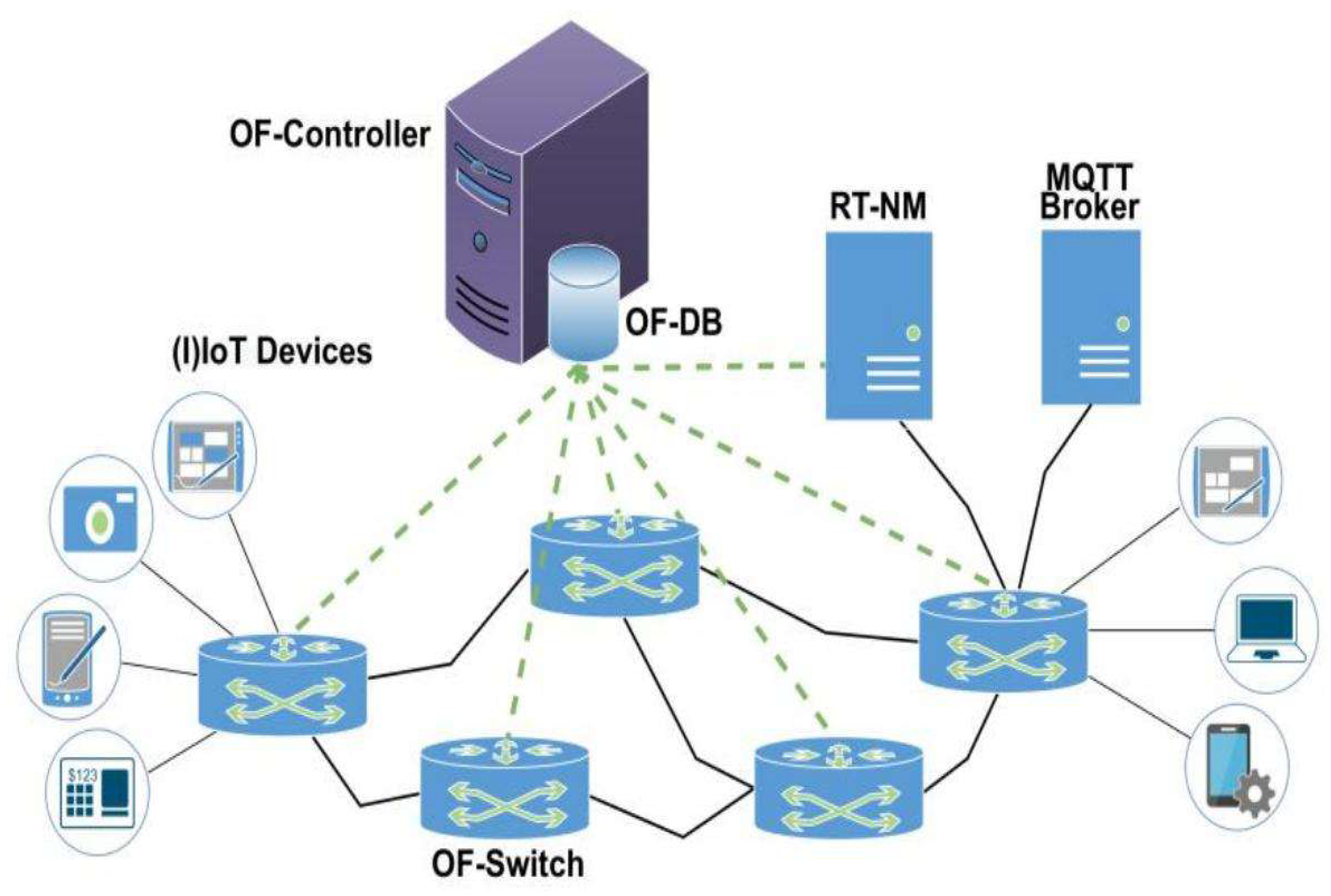

- Shahri, E.; Pedreiras, P.; Almeida, L. Extending MQTT with Real-Time Communication Services Based on SDN. Sensors 2022, 22, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).