Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

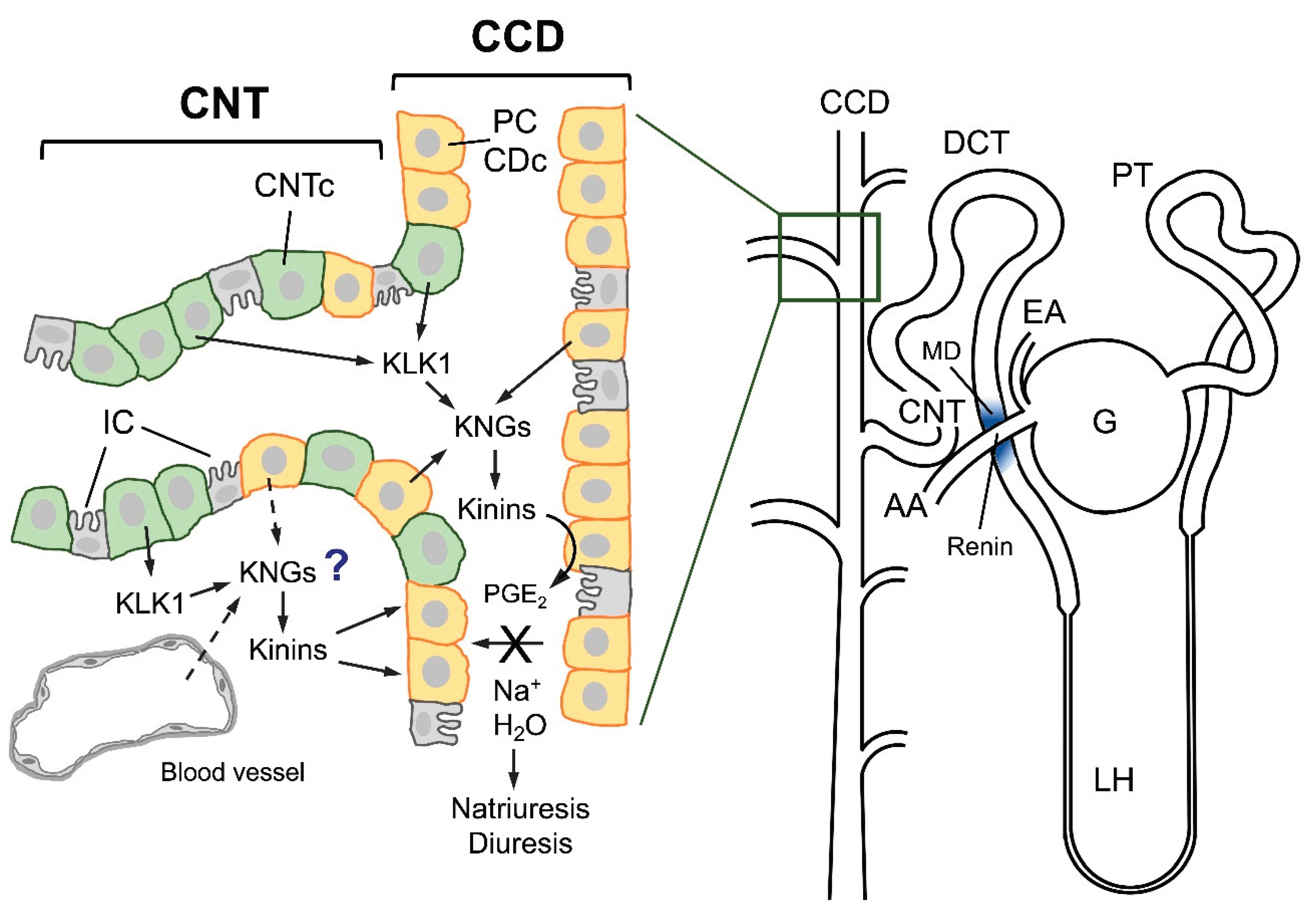

The Renal Kallikrein-Kinin System

Relations Between KKS and Renin-Angiotensin Aldosterone System

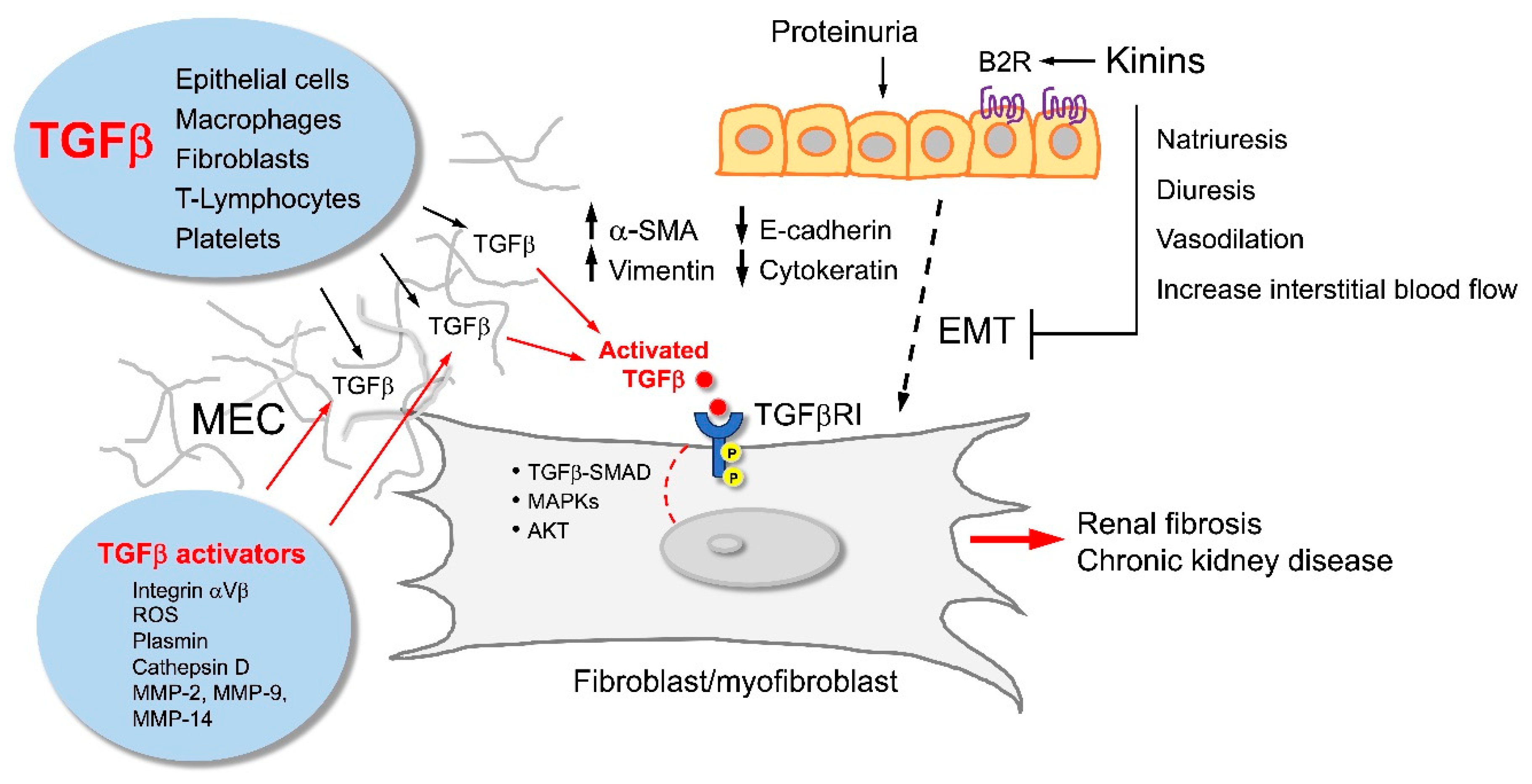

Renoprotective Potential of the KKS

KKS Intervention and Kidney Protection

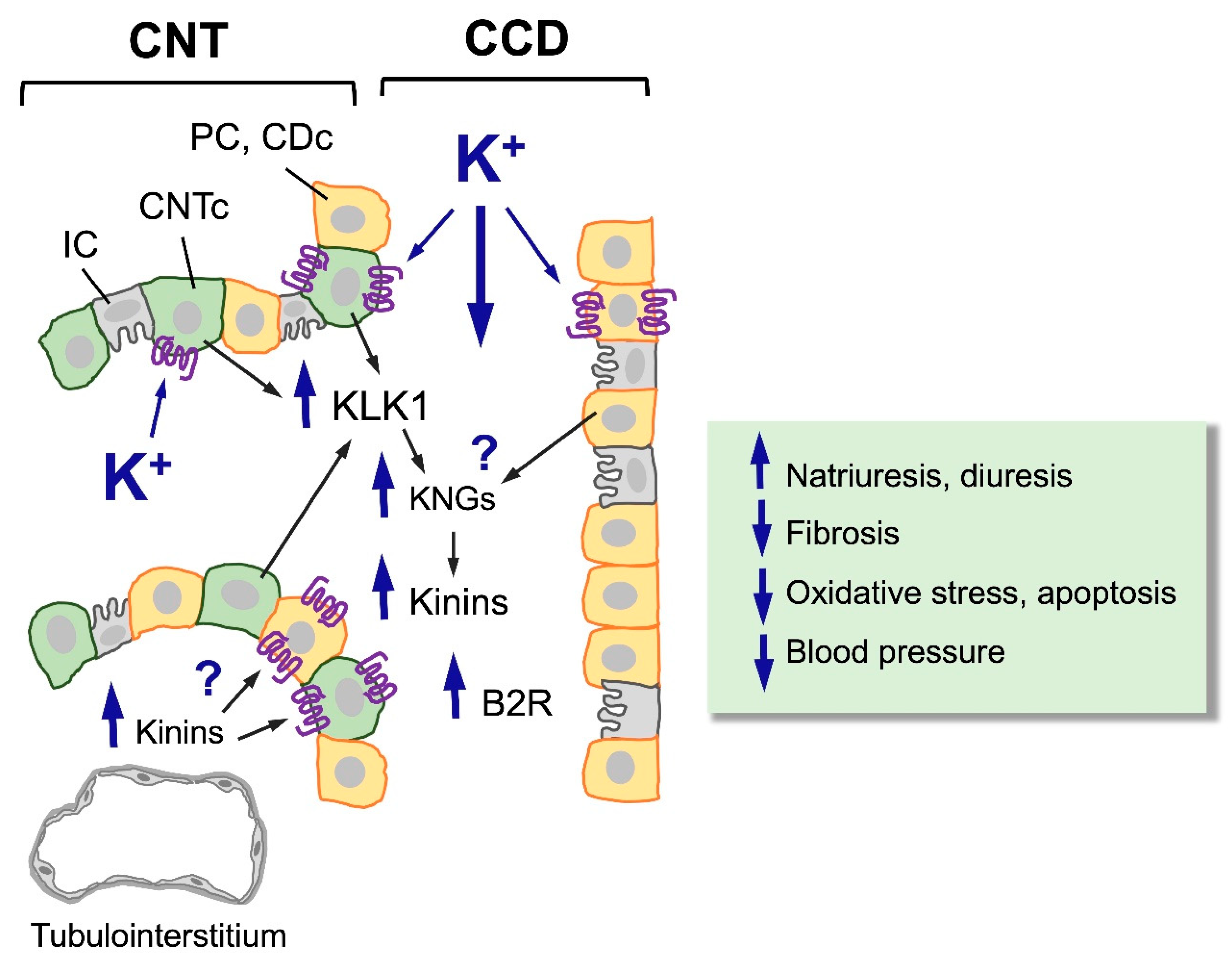

Stimulation of the KKS Through Potassium-Rich Diets

Concluding Remarks

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thurlow, J. S., M. Joshi, G. Yan, K. C. Norris, L. Y. Agodoa, C. M. Yuan and R. Nee. "Global epidemiology of end-stage kidney disease and disparities in kidney replacement therapy." Am J Nephrol 52 (2021): 98-107. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33752206. [CrossRef]

- McCullough, K. P., H. Morgenstern, R. Saran, W. H. Herman and B. M. Robinson. "Projecting esrd incidence and prevalence in the united states through 2030." J Am Soc Nephrol 30 (2019): 127-35. [CrossRef]

- Schieppati, A. and G. Remuzzi. "The june 2003 barry m. Brenner comgan lecture. The future of renoprotection: Frustration and promises." Kidney Int 64 (2003): 1947-55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14633117. [CrossRef]

- Eddy, A. A. "Protein restriction reduces transforming growth factor-beta and interstitial fibrosis in nephrotic syndrome." Am J Physiol 266 (1994): F884-93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8023968. [CrossRef]

- Remuzzi, G. "Nephropathic nature of proteinuria." Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 8 (1999): 655-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10630809. [CrossRef]

- Eddy, A. A. "Expression of genes that promote renal interstitial fibrosis in rats with proteinuria." Kidney Int Suppl 54 (1996): S49-54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8731195.

- Eddy, A. A. "Molecular insights into renal interstitial fibrosis." J Am Soc Nephrol 7 (1996): 2495-508. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8989727. [CrossRef]

- Bertani, T., F. Cutillo, C. Zoja, M. Broggini and G. Remuzzi. "Tubulo-interstitial lesions mediate renal damage in adriamycin glomerulopathy." Kidney Int 30 (1986): 488-96. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3784288. [CrossRef]

- Largo, R., D. Gómez-Garre, K. Soto, B. Marrón, J. Blanco, R. M. Gazapo, J. J. Plaza and J. Egido. "Angiotensin-converting enzyme is upregulated in the proximal tubules of rats with intense proteinuria." Hypertension 33 (1999): 732-9. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Garre, D., R. Largo, N. Tejera, J. Fortes, F. Manzarbeitia and J. Egido. "Activation of nf-kappab in tubular epithelial cells of rats with intense proteinuria: Role of angiotensin ii and endothelin-1." Hypertension 37 (2001): 1171-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11304520. [CrossRef]

- Bhoola, K. D., C. D. Figueroa and K. Worthy. "Bioregulation of kinins: Kallikreins, kininogens, and kininases." Pharmacol Rev 44 (1992): 1-80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1313585.

- Vio, C. P., S. Loyola and V. Velarde. "Localization of components of the kallikrein-kinin system in the kidney: Relation to renal function. State of the art lecture." Hypertension 19 (1992): II10-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1735562. [CrossRef]

- Vío, C. P. and C. D. Figueroa. "Subcellular localization of renal kallikrein by ultrastructural immunocytochemistry." Kidney Int 28 (1985): 36-42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3900530. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C. D., A. G. MacIver, J. C. Mackenzie and K. D. Bhoola. "Localisation of immunoreactive kininogen and tissue kallikrein in the human nephron." Histochemistry 89 (1988): 437-42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3170266. [CrossRef]

- Siragy, H. M., M. M. Ibrahim, A. A. Jaffa, R. Mayfield and H. S. Margolius. "Rat renal interstitial bradykinin, prostaglandin e2, and cyclic guanosine 3',5'-monophosphate. Effects of altered sodium intake." Hypertension 23 (1994): 1068-70. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8206596. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C. D., C. B. Gonzalez, S. Grigoriev, S. A. Abd Alla, M. Haasemann, K. Jarnagin and W. Müller-Esterl. "Probing for the bradykinin b2 receptor in rat kidney by anti-peptide and anti-ligand antibodies." J Histochem Cytochem 43 (1995): 137-48. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7822771. [CrossRef]

- Wirth, K., F. J. Hock, U. Albus, W. Linz, H. G. Alpermann, H. Anagnostopoulos, S. Henk, G. Breipohl, W. König and J. Knolle. "Hoe 140 a new potent and long acting bradykinin-antagonist: In vivo studies." Br J Pharmacol 102 (1991): 774-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1364852. [CrossRef]

- Katori, M. and M. Majima. "The renal kallikrein-kinin system: Its role as a safety valve for excess sodium intake, and its attenuation as a possible etiologic factor in salt-sensitive hypertension." Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 40 (2003): 43-115. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12627748. [CrossRef]

- Glasser, R. J. and A. F. Michael. "Urinary kallikrein in experimental renal disease." Lab Invest 34 (1976): 616-22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/933467.

- Ferri, C., C. Bellini, A. Carlomagno, A. Perrone and A. Santucci. "Urinary kallikrein and salt sensitivity in essential hypertensive males." Kidney Int 46 (1994): 780-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7996800. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R., M. I. Gimenez, F. Ramos, H. Baglivo and A. J. Ramirez. "Non-modulating hypertension: Evidence for the involvement of kallikrein/kinin activity associated with overactivity of the renin-angiotensin system. Successful blood pressure control during long-term na+ restriction." J Hypertens 14 (1996): 1287-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8934356. [CrossRef]

- Margolius, H. S. "Theodore cooper memorial lecture. Kallikreins and kinins. Some unanswered questions about system characteristics and roles in human disease." Hypertension 26 (1995): 221-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7635529. [CrossRef]

- Chao, J. and L. Chao. "Kallikrein-kinin in stroke, cardiovascular and renal disease." Exp Physiol 90 (2005): 291-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15653716. [CrossRef]

- Ardiles, L. G., C. D. Figueroa and S. A. Mezzano. "Renal kallikrein-kinin system damage and salt sensitivity: Insights from experimental models." Kidney Int Suppl (2003): S2-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12969120. [CrossRef]

- Ardiles, L. G., F. Loyola, P. Ehrenfeld, M. E. Burgos, C. A. Flores, G. Valderrama, I. Caorsi, J. Egido, S. A. Mezzano and C. D. Figueroa. "Modulation of renal kallikrein by a high potassium diet in rats with intense proteinuria." Kidney Int 69 (2006): 53-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16374423. [CrossRef]

- Ardiles, L. G., P. Ehrenfeld, Y. Quiroz, B. Rodriguez-Iturbe, J. Herrera-Acosta, S. Mezzano and C. D. Figueroa. "Effect of mycophenolate mofetil on kallikrein expression in the kidney of 5/6 nephrectomized rats." Kidney Blood Press Res 25 (2002): 289-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12435874. [CrossRef]

- Ardiles, L., A. Cardenas, M. E. Burgos, A. Droguett, P. Ehrenfeld, D. Carpio, S. Mezzano and C. D. Figueroa. "Antihypertensive and renoprotective effect of the kinin pathway activated by potassium in a model of salt sensitivity following overload proteinuria." Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304 (2013): F1399-410. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23552867. [CrossRef]

- Price, R. G. "Urinary enzymes, nephrotoxicity and renal disease." Toxicology 23 (1982): 99-134. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6126019. [CrossRef]

- Naicker, S., S. Naidoo, R. Ramsaroop, D. Moodley and K. Bhoola. "Tissue kallikrein and kinins in renal disease." Immunopharmacology 44 (1999): 183-92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10604543. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., D. W. Bowden, B. J. Spray, S. S. Rich and B. I. Freedman. "Identification of human plasma kallikrein gene polymorphisms and evaluation of their role in end-stage renal disease." Hypertension 31 (1998): 906-11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9535413. [CrossRef]

- Jozwiak, L., A. Drop, K. Buraczynska, P. Ksiazek, P. Mierzicki and M. Buraczynska. "Association of the human bradykinin b2 receptor gene with chronic renal failure." Mol Diagn 8 (2004): 157-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15771553. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Iturbe, B., H. Pons, Y. Quiroz, K. Gordon, J. Rincón, M. Chávez, G. Parra, J. Herrera-Acosta, D. Gómez-Garre, R. Largo, et al. "Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt-sensitive hypertension resulting from angiotensin ii exposure." Kidney Int 59 (2001): 2222-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11380825. [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. and S. S. El-Dahr. "Cross-talk of the renin-angiotensin and kallikrein-kinin systems." Biol Chem 387 (2006): 145-50. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16497145. [CrossRef]

- Imamura, A., H. S. Mackenzie, E. R. Lacy, F. N. Hutchison, W. R. Fitzgibbon and D. W. Ploth. "Effects of chronic treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor antagonist in two-kidney, one-clip hypertensive rats." Kidney Int 47 (1995): 1394-402. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7637269. [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, K., T. Igari, S. Nanba and M. Ishii. "Long-term effects of delapril on renal function and urinary excretion of kallikrein, prostaglandin e2, and thromboxane b2 in hypertensive patients." Am J Hypertens 4 (1991): 52S-53S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2009149. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, H. J., K. Glänzer, H. Meyer-Lehnert, M. Mohaupt and H. G. Predel. "Kinin- and non-kinin-mediated interactions of converting enzyme inhibitors with vasoactive hormones." J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 15 Suppl 6 (1990): S91-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1697369.

- Hutchison, F. N., X. Cui and S. K. Webster. "The antiproteinuric action of angiotensin-converting enzyme is dependent on kinin." J Am Soc Nephrol 6 (1995): 1216-22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8589289. [CrossRef]

- Ruggenenti, P., A. Perna, G. Gherardi, F. Gaspari, R. Benini and G. Remuzzi. "Renal function and requirement for dialysis in chronic nephropathy patients on long-term ramipril: Rein follow-up trial. Gruppo italiano di studi epidemiologici in nefrologia (gisen). Ramipril efficacy in nephropathy." Lancet 352 (1998): 1252-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9788454. [CrossRef]

- Pawluczyk, I. Z., S. R. Patel and K. P. Harris. "The role of bradykinin in the antifibrotic actions of perindoprilat on human mesangial cells." Kidney Int 65 (2004): 1240-51. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15086463. [CrossRef]

- Pawluczyk, I. Z., E. K. Tan, D. Lodwick and K. Harris. "Kallikrein gene 'knock-down' by small interfering rna transfection induces a profibrotic phenotype in rat mesangial cells." J Hypertens 26 (2008): 93-101. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18090545. [CrossRef]

- Erdös, E. G. "Angiotensin i converting enzyme and the changes in our concepts through the years. Lewis k. Dahl memorial lecture." Hypertension 16 (1990): 363-70. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2170273. [CrossRef]

- Murphey, L. J., J. V. Gainer, D. E. Vaughan and N. J. Brown. "Angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism modulates the human in vivo metabolism of bradykinin." Circulation 102 (2000): 829-32. [CrossRef]

- Marre, M., B. Bouhanick, G. Berrut, Y. Gallois, J. J. Le Jeune, G. Chatellier, J. Menard and F. Alhenc-Gelas. "Renal changes on hyperglycemia and angiotensin-converting enzyme in type 1 diabetes." Hypertension 33 (1999): 775-80. [CrossRef]

- Desposito, D., L. Waeckel, L. Potier, C. Richer, R. Roussel, N. Bouby and F. Alhenc-Gelas. "Kallikrein(k1)-kinin-kininase (ace) and end-organ damage in ischemia and diabetes: Therapeutic implications." Biol Chem 397 (2016): 1217-22. [CrossRef]

- Waeckel, L., L. Potier, C. Richer, R. Roussel, N. Bouby and F. Alhenc-Gelas. "Pathophysiology of genetic deficiency in tissue kallikrein activity in mouse and man." Thromb Haemost 110 (2013): 476-83. [CrossRef]

- Kakoki, M. and O. Smithies. "The kallikrein-kinin system in health and in diseases of the kidney." Kidney Int 75 (2009): 1019-30. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S., P. Sleight, J. Pogue, J. Bosch, R. Davies and G. Dagenais. "Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients." N Engl J Med 342 (2000): 145-53. [CrossRef]

- Alhenc-Gelas, F., N. Bouby, C. Richer, L. Potier, R. Roussel and M. Marre. "Kinins as therapeutic agents in cardiovascular and renal diseases." Curr Pharm Des 17 (2011): 2654-62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21728987. [CrossRef]

- Rhaleb, N. E., X. P. Yang and O. A. Carretero. "The kallikrein-kinin system as a regulator of cardiovascular and renal function." Compr Physiol 1 (2011): 971-93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23737209. [CrossRef]

- Girolami, J.-P., N. Bouby, C. Richer-Giudicelli and F. Alhenc-Gelas. "Kinins and kinin receptors in cardiovascular and renal diseases." Pharmaceuticals 14 (2021): 240. [CrossRef]

- Kohzuki, M., M. Yasujima, M. Kanazawa, K. Yoshida, T. Sato and K. Abe. "Do kinins mediate cardioprotective and renoprotective effects of cilazapril in spontaneously hypertensive rats with renal ablation?" Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol Suppl 22 (1995): S357-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9072427. [CrossRef]

- Bergaya, S., R. H. Hilgers, P. Meneton, Y. Dong, M. Bloch-Faure, T. Inagami, F. Alhenc-Gelas, B. I. Lévy and C. M. Boulanger. "Flow-dependent dilation mediated by endogenous kinins requires angiotensin at2 receptors." Circ Res 94 (2004): 1623-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15131008. [CrossRef]

- Messadi-Laribi, E., V. Griol-Charhbili, A. Pizard, M. P. Vincent, D. Heudes, P. Meneton, F. Alhenc-Gelas and C. Richer. "Tissue kallikrein is involved in the cardioprotective effect of at1-receptor blockade in acute myocardial ischemia." J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323 (2007): 210-6. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. H., X. P. Yang, V. G. Sharov, O. Nass, H. N. Sabbah, E. Peterson and O. A. Carretero. "Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin ii type 1 receptor antagonists in rats with heart failure. Role of kinins and angiotensin ii type 2 receptors." J Clin Invest 99 (1997): 1926-35. [CrossRef]

- Abadir, P. M., A. Periasamy, R. M. Carey and H. M. Siragy. "Angiotensin ii type 2 receptor-bradykinin b2 receptor functional heterodimerization." Hypertension 48 (2006): 316-22. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B., A. P. Nair, A. Misra, C. Z. Scott, J. H. Mahar and S. Fedson. "Neprilysin inhibitors in heart failure: The science, mechanism of action, clinical studies, and unanswered questions." JACC: Basic to Translational Science 8 (2023): 88-105. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452302X22002212. [CrossRef]

- Koid, S. S., J. Ziogas and D. J. Campbell. "Aliskiren reduces myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by a bradykinin b2 receptor- and angiotensin at2 receptor-mediated mechanism." Hypertension 63 (2014): 768-73. [CrossRef]

- Madeddu, P., M. V. Varoni, D. Palomba, C. Emanueli, M. P. Demontis, N. Glorioso, P. Dessì-Fulgheri, R. Sarzani and V. Anania. "Cardiovascular phenotype of a mouse strain with disruption of bradykinin b2-receptor gene." Circulation 96 (1997): 3570-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9396457. [CrossRef]

- Milia, A. F., V. Gross, R. Plehm, J. A. De Silva, M. Bader and F. C. Luft. "Normal blood pressure and renal function in mice lacking the bradykinin b(2) receptor." Hypertension 37 (2001): 1473-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11408397. [CrossRef]

- Uehara, Y., N. Hirawa, A. Numabe, Y. Kawabata, T. Ikeda, T. Gomi, A. Gotoh and M. Omata. "Long-term infusion of kallikrein attenuates renal injury in dahl salt-sensitive rats." Am J Hypertens 10 (1997): 83S-88S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9160787.

- Hirawa, N., Y. Uehara, Y. Kawabata, A. Numabe, T. Gomi, T. Ikeda, T. Suzuki, A. Goto, T. Toyo-oka and M. Omata. "Long-term inhibition of renin-angiotensin system sustains memory function in aged dahl rats." Hypertension 34 (1999): 496-502. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10489400. [CrossRef]

- Hirawa, N., Y. Uehara, T. Suzuki, Y. Kawabata, A. Numabe, T. Gomi, T. lkeda, K. Kizuki and M. Omata. "Regression of glomerular injury by kallikrein infusion in dahl salt-sensitive rats is a bradykinin b2-receptor-mediated event." Nephron 81 (1999): 183-93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9933754. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, W. C., H. Yoshida, J. Agata, L. Chao and J. Chao. "Human tissue kallikrein gene delivery attenuates hypertension, renal injury, and cardiac remodeling in chronic renal failure." Kidney Int 58 (2000): 730-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10916096. [CrossRef]

- Chao, J., J. J. Zhang, K. F. Lin and L. Chao. "Adenovirus-mediated kallikrein gene delivery reverses salt-induced renal injury in dahl salt-sensitive rats." Kidney Int 54 (1998): 1250-60. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9767541. [CrossRef]

- Chao, J., J. J. Zhang, K. F. Lin and L. Chao. "Human kallikrein gene delivery attenuates hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and renal injury in dahl salt-sensitive rats." Hum Gene Ther 9 (1998): 21-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9458239. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. J., G. Bledsoe, K. Kato, L. Chao and J. Chao. "Tissue kallikrein attenuates salt-induced renal fibrosis by inhibition of oxidative stress." Kidney Int 66 (2004): 722-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15253727. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., H. Yoshida, Q. Song, L. Chao and J. Chao. "Enhanced renal function in bradykinin b(2) receptor transgenic mice." Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278 (2000): F484-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10710553. [CrossRef]

- Xia, C. F., G. Bledsoe, L. Chao and J. Chao. "Kallikrein gene transfer reduces renal fibrosis, hypertrophy, and proliferation in doca-salt hypertensive rats." Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289 (2005): F622-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15886273. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, V., Y. Quiroz, M. Nava, H. Pons and B. Rodríguez-Iturbe. "Overload proteinuria is followed by salt-sensitive hypertension caused by renal infiltration of immune cells." Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283 (2002): F1132-41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12372790. [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, M. S., N. Ahsan and T. Taguchi. "Role of apoptosis in fibrogenesis." Nephron 90 (2002): 365-72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11961393. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. "Renal fibrosis: New insights into the pathogenesis and therapeutics." Kidney Int 69 (2006): 213-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16408108. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-De La Cruz, M. C., P. Ruiz-Torres, J. Alcamí, L. Díez-Marqués, R. Ortega-Velázquez, S. Chen, M. Rodríguez-Puyol, F. N. Ziyadeh and D. Rodríguez-Puyol. "Hydrogen peroxide increases extracellular matrix mrna through tgf-beta in human mesangial cells." Kidney Int 59 (2001): 87-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11135061. [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, G., B. Shen, Y. Y. Yao, M. Hagiwara, B. Mizell, M. Teuton, D. Grass, L. Chao and J. Chao. "Role of tissue kallikrein in prevention and recovery of gentamicin-induced renal injury." Toxicol Sci 102 (2008): 433-43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18227104. [CrossRef]

- Oda, Y., H. Nishi and M. Nangaku. "Role of inflammation in progression of chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Clinical implications." Seminars in Nephrology 43 (2023): 151431. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0270929523001419. [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, G., S. Crickman, J. Mao, C. F. Xia, H. Murakami, L. Chao and J. Chao. "Kallikrein/kinin protects against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity by inhibition of inflammation and apoptosis." Nephrol Dial Transplant 21 (2006): 624-33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16401625. [CrossRef]

- Kakoki, M., C. M. Kizer, X. Yi, N. Takahashi, H. S. Kim, C. R. Bagnell, C. J. Edgell, N. Maeda, J. C. Jennette and O. Smithies. "Senescence-associated phenotypes in akita diabetic mice are enhanced by absence of bradykinin b2 receptors." J Clin Invest 116 (2006): 1302-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16604193. [CrossRef]

- Basnakian, A. G., G. P. Kaushal and S. V. Shah. "Apoptotic pathways of oxidative damage to renal tubular epithelial cells." Antioxid Redox Signal 4 (2002): 915-24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12573140. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J., T. Tsuji, H. Yasuda, Y. Sun, Y. Fujigaki and A. Hishida. "The molecular mechanisms of the attenuation of cisplatin-induced acute renal failure by n-acetylcysteine in rats." Nephrol Dial Transplant 23 (2008): 2198-205. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18385389. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H. Z., Y. Y. Chen, L. Zhu, H. J. Xu, Y. Wang, F. R. Shen, Z. N. Cai and Y. L. Shen. "[cox-2 and ho-1 are involved in the delayed preconditioning elicited by bradykinin in rat hearts]." Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 36 (2007): 13-20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17290486. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H. L., H. H. Wang, C. Y. Wu and C. M. Yang. "Reactive oxygen species-dependent c-fos/activator protein 1 induction upregulates heme oxygenase-1 expression by bradykinin in brain astrocytes." Antioxid Redox Signal 13 (2010): 1829-44. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20486760. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A. "Nephrology forum: Apoptotic regulatory proteins in renal injury." Kidney Int 58 (2000): 467-85. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10886604. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A., S. González Cuadrado, C. Lorz and J. Egido. "Apoptosis in renal diseases." Front Biosci 1 (1996): d30-47. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9159208. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. L., B. Yang, B. E. Wagner, J. Savill and A. M. El Nahas. "Cellular apoptosis and proliferation in experimental renal fibrosis." Nephrol Dial Transplant 13 (1998): 2216-26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9761500. [CrossRef]

- Yukawa, K., M. Kishino, M. Goda, X. M. Liang, A. Kimura, T. Tanaka, T. Bai, K. Owada-Makabe, Y. Tsubota, T. Ueyama, et al. "Stat6 deficiency inhibits tubulointerstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy." Int J Mol Med 15 (2005): 225-30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15647835.

- Vaziri, N. D. "Roles of oxidative stress and antioxidant therapy in chronic kidney disease and hypertension." Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 13 (2004): 93-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15090865. [CrossRef]

- Montanari, D., H. Yin, E. Dobrzynski, J. Agata, H. Yoshida, J. Chao and L. Chao. "Kallikrein gene delivery improves serum glucose and lipid profiles and cardiac function in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats." Diabetes 54 (2005): 1573-80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15855348. [CrossRef]

- Allen, D. A., S. Harwood, M. Varagunam, M. J. Raftery and M. M. Yaqoob. "High glucose-induced oxidative stress causes apoptosis in proximal tubular epithelial cells and is mediated by multiple caspases." FASEB J 17 (2003): 908-10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12670885. [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, Y., J. Bravo, J. Herrera-Acosta, R. J. Johnson and B. Rodríguez-Iturbe. "Apoptosis and nfkappab activation are simultaneously induced in renal tubulointerstitium in experimental hypertension." Kidney Int Suppl (2003): S27-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12969124. [CrossRef]

- Soto, K., D. Gómez-Garre, R. Largo, J. Gallego-Delgado, N. Tejera, M. P. Catalán, A. Ortiz, J. J. Plaza, C. Alonso and J. Egido. "Tight blood pressure control decreases apoptosis during renal damage." Kidney Int 65 (2004): 811-22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14871401. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. E., N. J. Brunskill, K. P. Harris, E. Bailey, J. H. Pringle, P. N. Furness and J. Walls. "Proteinuria induces tubular cell turnover: A potential mechanism for tubular atrophy." Kidney Int 55 (1999): 890-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10027925. [CrossRef]

- Higa, E. M., N. Schor, M. A. Boim, H. Ajzen and O. L. Ramos. "Role of the prostaglandin and kallikrein-kinin systems in aminoglycoside-induced acute renal failure." Braz J Med Biol Res 18 (1985): 355-65. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2424533.

- Alhenc-Gelas, F., N. Bouby and J. P. Girolami. "Kallikrein/k1, kinins, and ace/kininase ii in homeostasis and in disease insight from human and experimental genetic studies, therapeutic implication." Front Med (Lausanne) 6 (2019): 136. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31316987. [CrossRef]

- Kränkel, N., R. G. Katare, M. Siragusa, L. S. Barcelos, P. Campagnolo, G. Mangialardi, O. Fortunato, G. Spinetti, N. Tran, K. Zacharowski, et al. "Role of kinin b2 receptor signaling in the recruitment of circulating progenitor cells with neovascularization potential." Circ Res 103 (2008): 1335-43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18927465. [CrossRef]

- Kayashima, Y., O. Smithies and M. Kakoki. "The kallikrein-kinin system and oxidative stress." Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 21 (2012): 92-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22048723. [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, J. S., S. Bergaya, R. Tamarat, M. Duriez, C. M. Boulanger and B. I. Levy. "Proangiogenic effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition is mediated by the bradykinin b(2) receptor pathway." Circ Res 89 (2001): 678-83. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11597990. [CrossRef]

- Spinetti, G., O. Fortunato, D. Cordella, P. Portararo, N. Kränkel, R. Katare, G. B. Sala-Newby, C. Richer, M. P. Vincent, F. Alhenc-Gelas, et al. "Tissue kallikrein is essential for invasive capacity of circulating proangiogenic cells." Circ Res 108 (2011): 284-93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21164105. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K., Q. Z. Li, A. M. Delgado-Vega, A. K. Abelson, E. Sánchez, J. A. Kelly, L. Li, Y. Liu, J. Zhou, M. Yan, et al. "Kallikrein genes are associated with lupus and glomerular basement membrane-specific antibody-induced nephritis in mice and humans." J Clin Invest 119 (2009): 911-23. [CrossRef]

- Marceau, F. "Drugs of the kallikrein–kinin system: An overview." Drugs and Drug Candidates 2 (2023): 538-53. [CrossRef]

- Stone, O. A., C. Richer, C. Emanueli, V. van Weel, P. H. Quax, R. Katare, N. Kraenkel, P. Campagnolo, L. S. Barcelos, M. Siragusa, et al. "Critical role of tissue kallikrein in vessel formation and maturation: Implications for therapeutic revascularization." Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29 (2009): 657-64. [CrossRef]

- Emanueli, C., A. Minasi, A. Zacheo, J. Chao, L. Chao, M. B. Salis, S. Straino, M. G. Tozzi, R. Smith, L. Gaspa, et al. "Local delivery of human tissue kallikrein gene accelerates spontaneous angiogenesis in mouse model of hindlimb ischemia." Circulation 103 (2001): 125-32. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, Y. M., M. Bader, J. B. Pesquero, C. Tschöpe, E. Scholtens, W. H. van Gilst and H. Buikema. "Increased kallikrein expression protects against cardiac ischemia." Faseb j 14 (2000): 1861-3. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. A., Jr., R. C. Araujo, O. Baltatu, S. M. Oliveira, C. Tschöpe, E. Fink, S. Hoffmann, R. Plehm, K. X. Chai, L. Chao, et al. "Reduced cardiac hypertrophy and altered blood pressure control in transgenic rats with the human tissue kallikrein gene." Faseb j 14 (2000): 1858-60. [CrossRef]

- Tschöpe, C., T. Walther, J. Königer, F. Spillmann, D. Westermann, F. Escher, M. Pauschinger, J. B. Pesquero, M. Bader, H. P. Schultheiss, et al. "Prevention of cardiac fibrosis and left ventricular dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats by transgenic expression of the human tissue kallikrein gene." Faseb j 18 (2004): 828-35. [CrossRef]

- Koch, M., F. Spillmann, A. Dendorfer, D. Westermann, C. Altmann, M. Sahabi, S. V. Linthout, M. Bader, T. Walther, H. P. Schultheiss, et al. "Cardiac function and remodeling is attenuated in transgenic rats expressing the human kallikrein-1 gene after myocardial infarction." Eur J Pharmacol 550 (2006): 143-8. [CrossRef]

- Kolodka, T., M. L. Charles, A. Raghavan, I. A. Radichev, C. Amatya, J. Ellefson, A. Y. Savinov, A. Nag, M. S. Williams and M. S. Robbins. "Preclinical characterization of recombinant human tissue kallikrein-1 as a novel treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus." PLoS One 9 (2014): e103981. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25100328. [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, S., V. Bovenzi, J. Côté, W. Neugebauer, M. Amblard, J. Martinez, B. Lammek, M. Savard and F. Gobeil. "Structure-activity relationships of novel peptide agonists of the human bradykinin b2 receptor." Peptides 30 (2009): 777-87. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19111586. [CrossRef]

- Côté, J., M. Savard, V. Bovenzi, S. Bélanger, J. Morin, W. Neugebauer, A. Larouche, C. Dubuc and F. Gobeil. "Novel kinin b1 receptor agonists with improved pharmacological profiles." Peptides 30 (2009): 788-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19150636. [CrossRef]

- Bodin, S., C. Chollet, N. Goncalves-Mendes, J. Gardes, F. Pean, D. Heudes, P. Bruneval, M. Marre, F. Alhenc-Gelas and N. Bouby. "Kallikrein protects against microalbuminuria in experimental type i diabetes." Kidney Int 76 (2009): 395-403. [CrossRef]

- Allard, J., M. Buléon, E. Cellier, I. Renaud, C. Pecher, F. Praddaude, M. Conti, I. Tack and J. P. Girolami. "Ace inhibitor reduces growth factor receptor expression and signaling but also albuminuria through b2-kinin glomerular receptor activation in diabetic rats." Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293 (2007): F1083-92. [CrossRef]

- Buléon, M., J. Allard, A. Jaafar, F. Praddaude, Z. Dickson, M. T. Ranera, C. Pecher, J. P. Girolami and I. Tack. "Pharmacological blockade of b2-kinin receptor reduces renal protective effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in db/db mice model." Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294 (2008): F1249-56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18367657. [CrossRef]

- Cicardi, M., A. Banerji, F. Bracho, A. Malbrán, B. Rosenkranz, M. Riedl, K. Bork, W. Lumry, W. Aberer, H. Bier, et al. "Icatibant, a new bradykinin-receptor antagonist, in hereditary angioedema." N Engl J Med 363 (2010): 532-41. [CrossRef]

- Whalley, E. T., S. Clegg, J. M. Stewart and R. J. Vavrek. "The effect of kinin agonists and antagonists on the pain response of the human blister base." Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 336 (1987): 652-5. [CrossRef]

- Hicks, B. M., K. B. Filion, H. Yin, L. Sakr, J. A. Udell and L. Azoulay. "Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and risk of lung cancer: Population based cohort study." Bmj 363 (2018): k4209. [CrossRef]

- Ideishi, M., S. Miura, T. Sakai, M. Sasaguri, Y. Misumi and K. Arakawa. "Taurine amplifies renal kallikrein and prevents salt-induced hypertension in dahl rats." J Hypertens 12 (1994): 653-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7963490.

- Vío, C. P. and C. D. Figueroa. "Evidence for a stimulatory effect of high potassium diet on renal kallikrein." Kidney Int 31 (1987): 1327-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3302506. [CrossRef]

- Welling, P. A. and K. Ho. "A comprehensive guide to the romk potassium channel: Form and function in health and disease." Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297 (2009): F849-63. [CrossRef]

- El Moghrabi, S., P. Houillier, N. Picard, F. Sohet, B. Wootla, M. Bloch-Faure, F. Leviel, L. Cheval, S. Frische, P. Meneton, et al. "Tissue kallikrein permits early renal adaptation to potassium load." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 (2010): 13526-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20624970. [CrossRef]

- Obika, L. F. "Urinary kallikrein excretion after potassium adaptation in the rat." Arch Int Physiol Biochim 95 (1987): 189-93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2446581.

- Jin, L., L. Chao and J. Chao. "Potassium supplement upregulates the expression of renal kallikrein and bradykinin b2 receptor in shr." Am J Physiol 276 (1999): F476-84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10070172. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, I., T. Fujita, M. Majima and M. Katori. "A secretory mechanism of renal kallikrein by a high potassium ion; a possible involvement of atp-sensitive potassium channel." Immunopharmacology 44 (1999): 49-55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10604524. [CrossRef]

- Valdés, G., C. P. Vio, J. Montero and R. Avendaño. "Potassium supplementation lowers blood pressure and increases urinary kallikrein in essential hypertensives." J Hum Hypertens 5 (1991): 91-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2072372.

- Overlack, A., K. O. Stumpe, B. Moch, A. Ollig, R. Kleinmann, H. M. Müller, R. Kolloch and F. Krück. "Hemodynamic, renal, and hormonal responses to changes in dietary potassium in normotensive and hypertensive man: Long-term antihypertensive effect of potassium supplementation in essential hypertension." Klin Wochenschr 63 (1985): 352-60. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3923252. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D., B. Banner, J. E. Janosky and P. U. Feig. "Potassium supplementation attenuates experimental hypertensive renal injury." J Am Soc Nephrol 2 (1992): 1529-37. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1600125. [CrossRef]

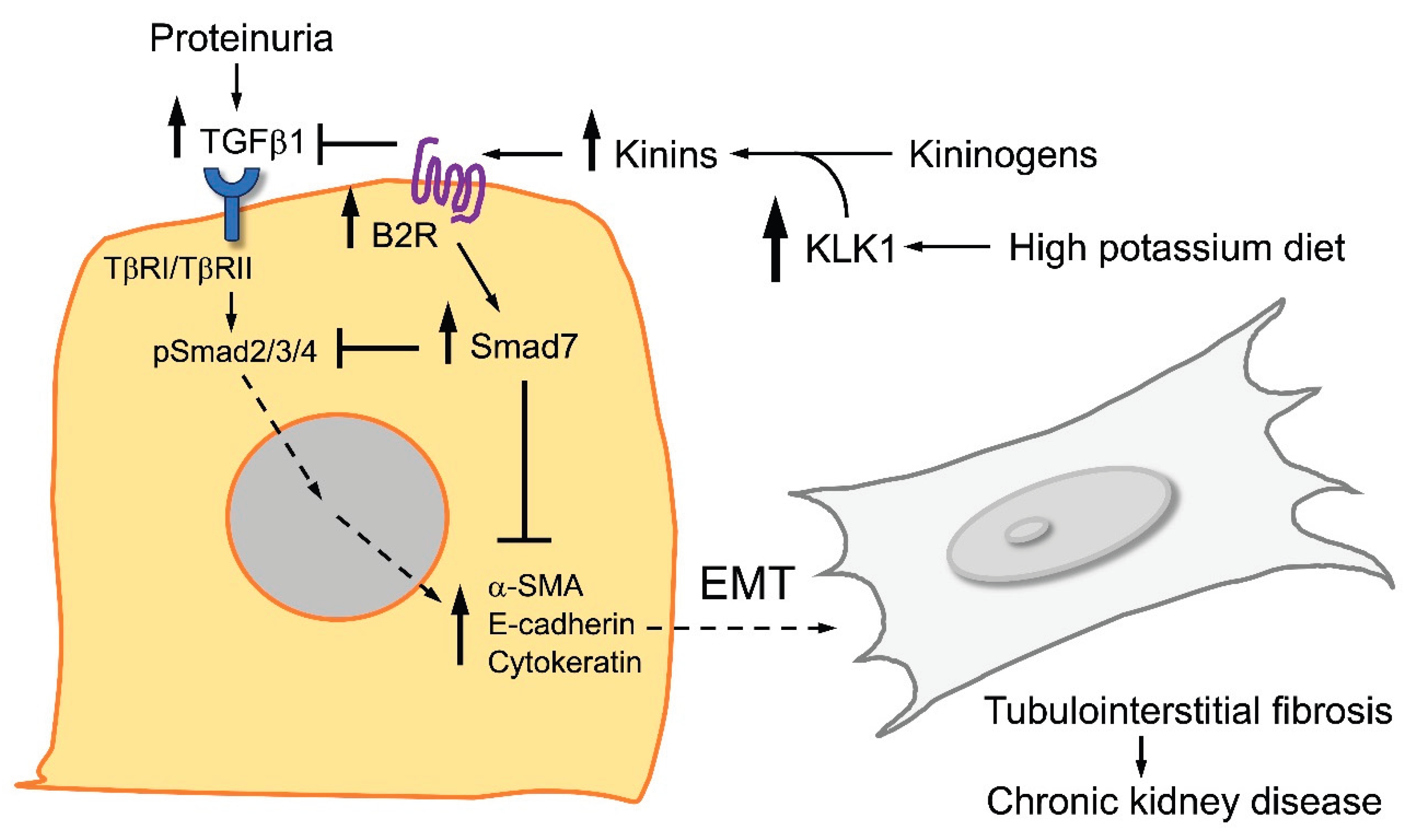

- Cárdenas, A., J. Campos, P. Ehrenfeld, S. Mezzano, M. Ruiz-Ortega, C. D. Figueroa and L. Ardiles. "Up-regulation of the kinin b2 receptor pathway modulates the tgf-β/smad signaling cascade to reduce renal fibrosis induced by albumin." Peptides 73 (2015): 7-19. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26256678. [CrossRef]

- Eaton, S. B. and M. Konner. "Paleolithic nutrition. A consideration of its nature and current implications." N Engl J Med 312 (1985): 283-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2981409. [CrossRef]

- Agriculture, U. S. D. o. U.S. Department of agriculture; u.S. Department of health and human services. Dietary guidelines for americans, 2020–2025 . 9th ed. December 2020. Available from: Https://www.Dietaryguidelines.Gov. U.S.: 2020,.

- Murray, C. J. and A. D. Lopez. "Measuring the global burden of disease." N Engl J Med 369 (2013): 448-57. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23902484. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, L. K. "Possible role of chronic excess salt consumption in the pathogenesis of essential hypertension." The American Journal of Cardiology 8 (1961): 571-75. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0002914961901370. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, L. K., G. Leitl and M. Heine. "Influence of dietary potassium and sodium/potassium molar ratios on the development of salt hypertension." J Exp Med 136 (1972): 318-30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5043414. [CrossRef]

- Aburto, N. J., S. Hanson, H. Gutierrez, L. Hooper, P. Elliott and F. P. Cappuccio. "Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: Systematic review and meta-analyses." BMJ 346 (2013): f1378. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23558164. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, M. V., S. Grossmann, M. Roesinger, N. Gresko, A. P. Todkar, G. Barmettler, U. Ziegler, A. Odermatt, D. Loffing-Cueni and J. Loffing. "Rapid dephosphorylation of the renal sodium chloride cotransporter in response to oral potassium intake in mice." Kidney International 83 (2013): 811-24. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., F. J. He, Q. Sun, C. Yuan, L. M. Kieneker, G. C. Curhan, G. A. MacGregor, S. J. L. Bakker, N. R. C. Campbell, M. Wang, et al. "24-hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion and cardiovascular risk." N Engl J Med 386 (2022): 252-63. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C. and S. Abreu. "Sodium and potassium intake and cardiovascular disease in older people: A systematic review." Nutrients 12 (2020): 10.3390/nu12113447.

- Caravaca-Fontán, F., J. Valladares, R. Díaz-Campillejo, S. Barroso, E. Luna and F. Caravaca. "Renal potassium handling in chronic kidney disease: Differences between patients with or wihtout hyperkalemia." Nefrologia (Engl Ed) 40 (2020): 152-59. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31353054. [CrossRef]

- Swift, S. L., Y. Drexler, D. Sotres-Alvarez, L. Raij, M. M. Llabre, N. Schneiderman, L. V. Horn, J. P. Lash, Y. Mossavar-Rahmani and T. Elfassy. "Associations of sodium and potassium intake with chronic kidney disease in a prospective cohort study: Findings from the hispanic community health study/study of latinos, 2008–2017." BMC Nephrology 23 (2022): 133. [CrossRef]

- Suenaga, T., S. Tanaka, H. Kitamura, K. Tsuruya, T. Nakano and T. Kitazono. "Estimated potassium intake and the progression of chronic kidney disease." Nephrol Dial Transplant 40 (2025): 1362-73. [CrossRef]

- Picard, K., M. I. Barreto Silva, D. Mager and C. Richard. "Dietary potassium intake and risk of chronic kidney disease progression in predialysis patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review." Adv Nutr 11 (2020): 1002-15. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J., H. B. Koh, G. Y. Heo, H. W. Kim, J. T. Park, T. I. Chang, T.-H. Yoo, S.-W. Kang, K. Kalantar-Zadeh, C. Rhee, et al. "Higher potassium intake is associated with a lower risk of chronic kidney disease: Population-based prospective study." The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 119 (2024): 1044-51. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002916524000716. [CrossRef]

- Gritter, M., L. Vogt, S. M. H. Yeung, R. D. Wouda, C. R. B. Ramakers, M. H. de Borst, J. I. Rotmans and E. J. Hoorn. "Rationale and design of a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial assessing the renoprotective effects of potassium supplementation in chronic kidney disease." Nephron 140 (2018): 48-57. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).