1. Introduction

The construction industry is inherently complex, characterized by high levels of uncertainty, interdependencies among stakeholders, and significant risks at every stage of a project lifecycle. Risk is defined as an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, can positively or negatively affect project objectives [

1]. Despite advancements in technology, the industry continues to lack a standardized, systematic approach to risk assessment that is both universally applicable and capable of leveraging the full potential of modern tools such as Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Machine Learning (ML). BIM has already demonstrated its transformative potential by enabling better collaboration, visualization, and management of construction project [

2,

3]. The promise of Building Information Models lies in their capacity to be information-rich, machine-readable, and to integrate insights from multiple building disciplines within a single or integrated model environment.

Conventional forms of representing construction related knowledge, including drawings, three-dimensional models, technical documentation, and tabular data, are undergoing a transformation toward semantically enriched information models. Consequently, building information is no longer confined to discrete artifacts but exists within an integrated digital environment that is, by design, machine-interpretable

This research examines whether artificial neural networks (ANN) can effectively support the analysis of BIM-generated data to identify and assess construction project risks. Consequently, the aim of this work is to develop a theoretical framework for integrating BIM-extracted data with machine learning techniques to enhance the effectiveness of construction project risk management. In recent years, a growing body of literature has examined the role of BIM technology in risk management [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, when machine learning is combined with BIM, the input data typically comes from expert surveys rather than directly from BIM models [

9,

10,

11]. These expert assessments are then used to train predictive algorithms such as ANN or decision trees. This creates a promising and industry-relevant research gap: the direct integration of computer-generated BIM models with machine learning techniques.

The main challenge addressed in this study lies in bridging two paradigms: the established body of research on BIM-based risk management, and the emerging field of applying machine learning techniques to information-rich, parametric BIM models. Since data mining has not yet been explored within the context of BIM-based risk management in construction, the scope of the literature review was expanded to include keywords such as

data mining,

machine learning and BIM, and

K-means clustering and BIM. The primary goal of data mining is to extract patterns and uncover meaningful information from a dataset, yielding “knowledge” that can support and enhance decision-making [

12]. Although these searches yielded a relatively small number of publications, they nonetheless provided valuable insights into the application of unsupervised machine learning methods in BIM-related research [

13,

14,

15,

16] . This disparity in publication volume highlights a notable research gap and suggests a significant opportunity for further exploration of unsupervised learning and data-driven approaches within BIM-based risk analysis.

Based on the literature review, it was observed that, in most cases, the selected computational methods were described without a clear rationale for their choice. In this paper, we provide a concise overview of relevant machine learning techniques and BIM characteristics to justify the methodological decisions adopted in this study

2. Materials and Methods

This study aims to determine whether artificial neural networks (ANN) can effectively support the analysis of BIM-generated data for identifying and assessing construction project risks.

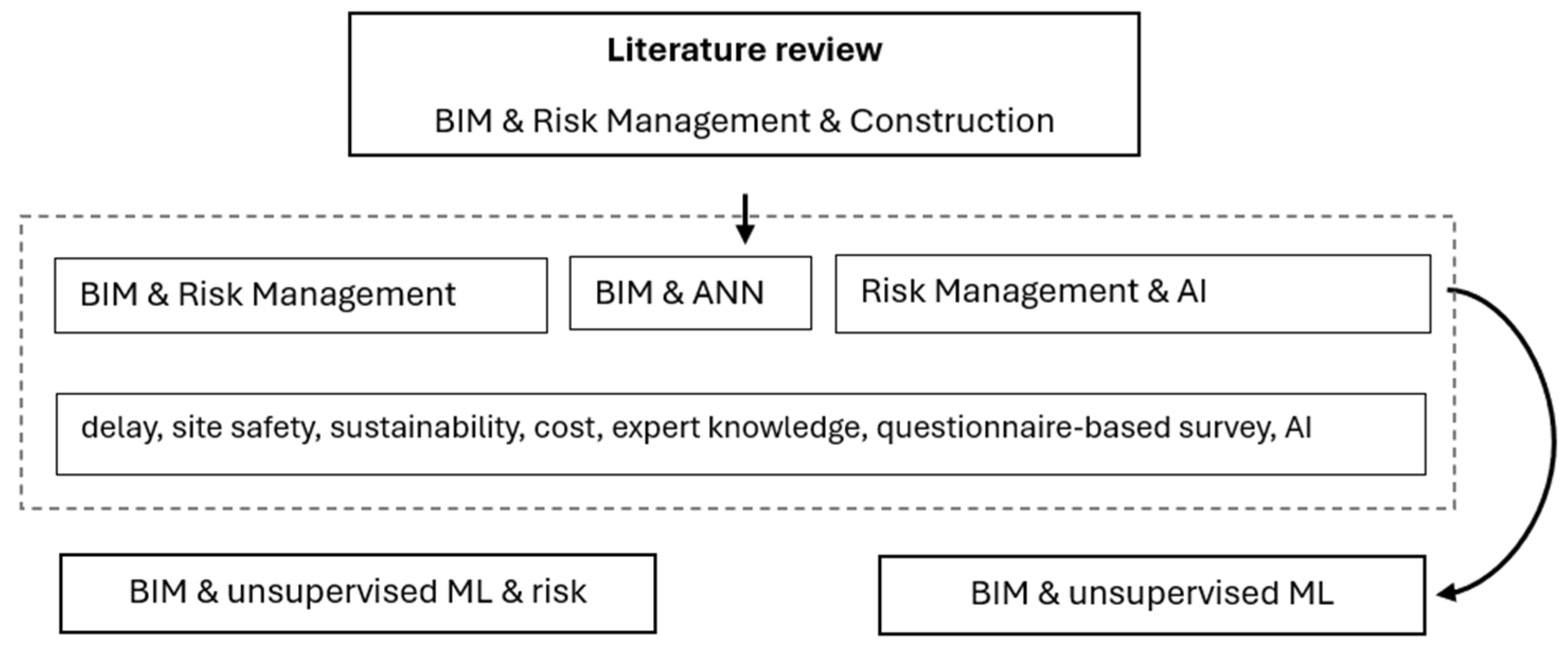

Figure 1 illustrates the initial research methodology, which begins with defining the key search terms, conducting a literature review, and subsequently broadening the scope to include additional categories identified as essential for comprehensively addressing the research question. The relevant theoretical foundations are then presented and examined in relation to the study’s objectives, serving both as the conceptual basis for the research and as an interpretive framework through which the data are understood and analysed.

2.1. Literature Overview

A literature search was conducted for this study using Google Scholar, SCOPUS, and the reference lists of relevant publications. The last SCOPUS search employed the keywords “BIM AND risk management AND construction.” Out of 207 identified papers, 163 were published after 2017, indicating that approximately 78% of the research in this area has emerged within the last eight years. However, when cross-referencing BIM with unsupervised machine learning or data mining, the number of relevant studies declines sharply, with only about 5 to 12 publications identified. This disparity in publication volume highlights a notable research gap and suggests a significant opportunity for further exploration of unsupervised learning and data-driven approaches within BIM-based risk analysis.

This study is grounded in a pragmatic philosophical paradigm, emphasizing applied research that integrates multiple perspectives in the interpretation of data. Depending on the research question, both observable phenomena and subjective meanings are regarded as valid sources of knowledge [

17].

For this paper, the researchers adopted a cross-sectional literature review; see

Figure 1, to identify:

BIM-based risk management latest developments and practices

Potential research gap

Risk factors which can be deducted from BIM database

Suitable machine learning application

2.2. Risk Management Practices and BIM

Project Management Institute defined a risk as an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, may exert a positive or negative influence on one or more project objectives. Identified risks may or may not materialize during a project. Throughout the project lifecycle, teams strive to identify and assess both known and emerging risks, whether internal or external to the project context [

1,

18]. Project Risk Management is situated within the Uncertainty project management performance domain, which comprises the set of activities and functions concerned with managing risks and uncertainties that can influence the project’s cost [

19], schedule, or scope baseline. It involves a sequence of processes, including risk planning, identification, analysis, response formulation, response execution, and continuous risk monitoring throughout the project [

20] . Risk management planning identifies the objectives, the approach, and the resources to carry out risk treatment activities. Risk identification defines the causes of the risks to which the project is exposed. Risk analysis determines the probabilities of occurrence and the associated impacts on project outcomes in terms of cost, schedule, scope, and quality variance [

21].

Numan’s systematic review [

22] demonstrated that while BIMs automated and visualization capabilities significantly enhance the identification, analysis, response planning, and monitoring of risks across the design, construction, and operational stages, its effective application to risk management remains constrained by substantial organizational and technical challenges.

The risk breakdown structure (RBS) is a fundamental tool in project risk management that organizes potential sources of risk into a hierarchical framework. It provides a structured basis for employing various risk identification techniques, including brainstorming, assumptions and constraints analysis, data analytics, questionnaires, fault tree analysis, and root cause analysis. By ensuring comprehensive coverage of all risk categories, the RBS supports effective response planning and risk monitoring, as well as both qualitative and quantitative risk analysis. An example of a generic project-level RBS is presented in

Table 1.

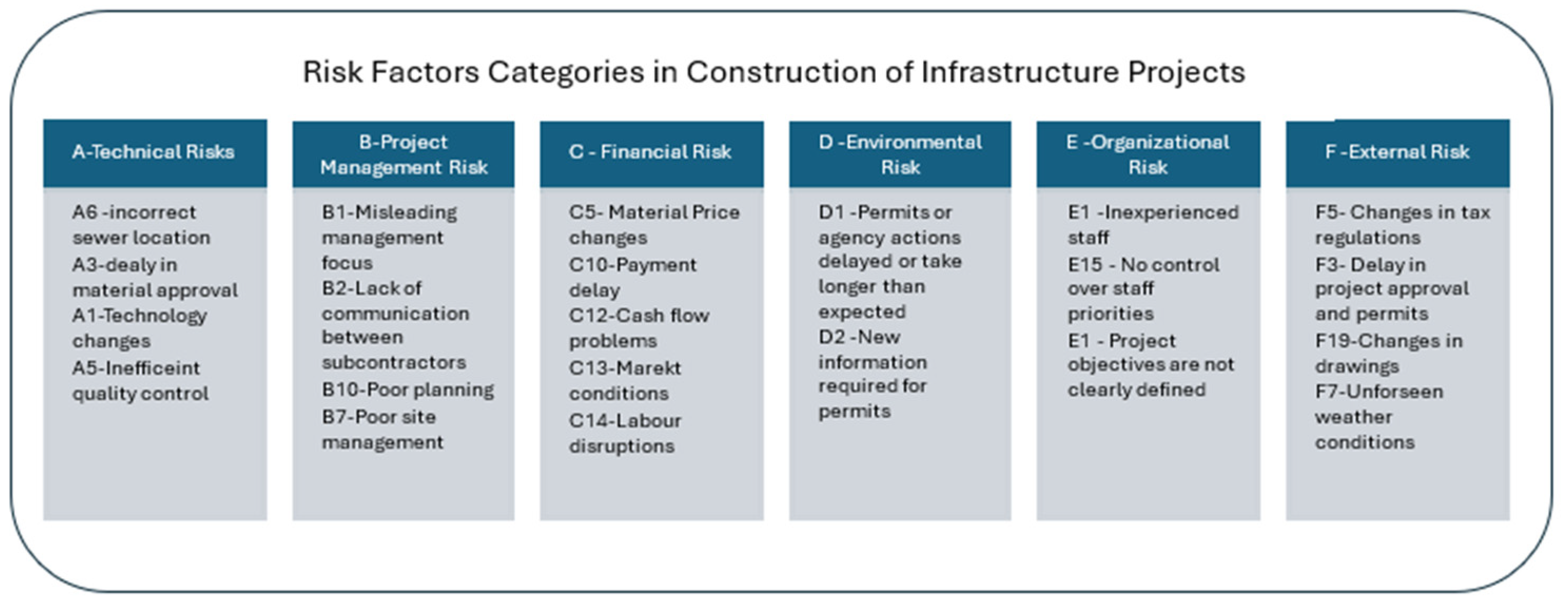

Nabawy and Mohamed [

10]proposed a modified RBS tailored specifically to infrastructure construction projects (see

Figure 2). Although their prioritized list of 72 risks appears somewhat arbitrary in terms of category assignment, it offers two important insights:

- (1)

a comprehensive overview of risks that are specific to construction activities, and

- (2)

evidence of the limitations of applying a generic risk RBS to construction projects, where the appropriate classification category for a given risk is not always clear.

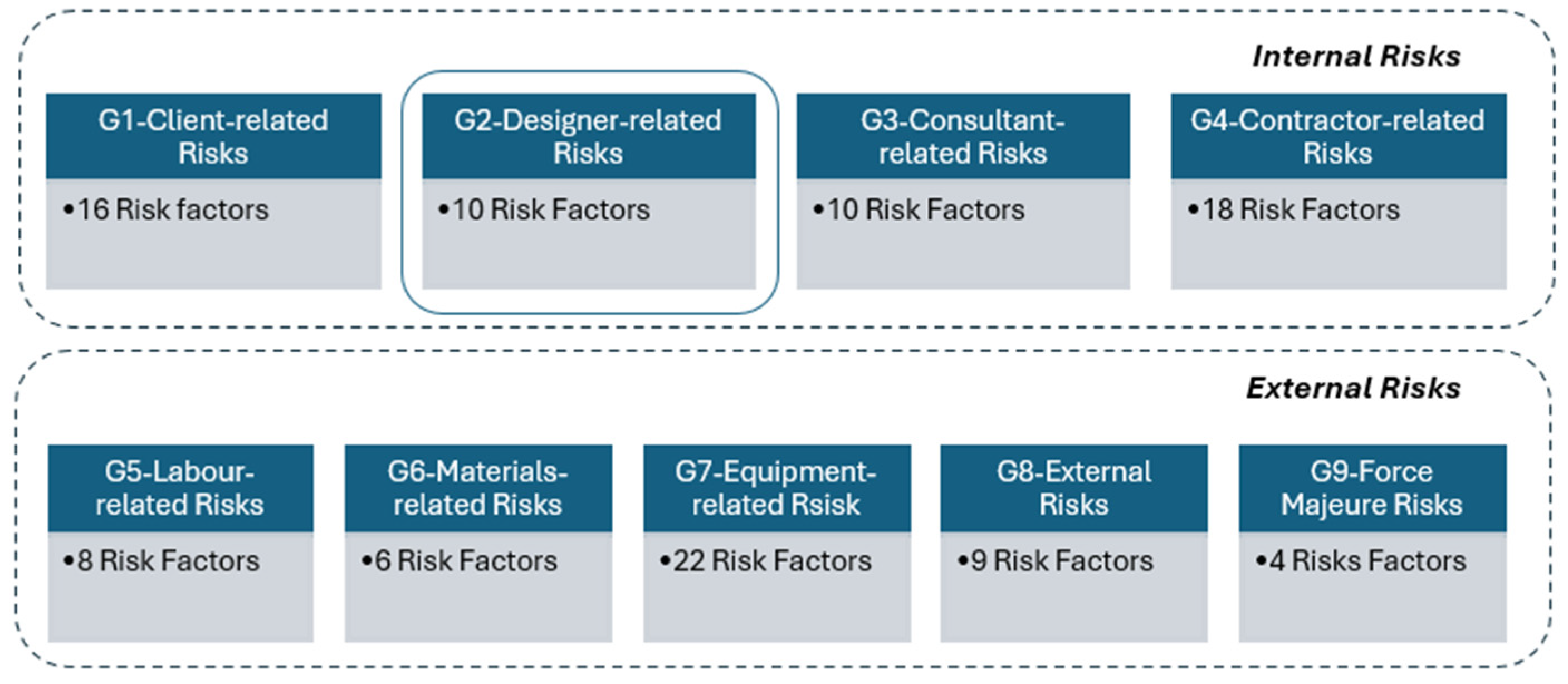

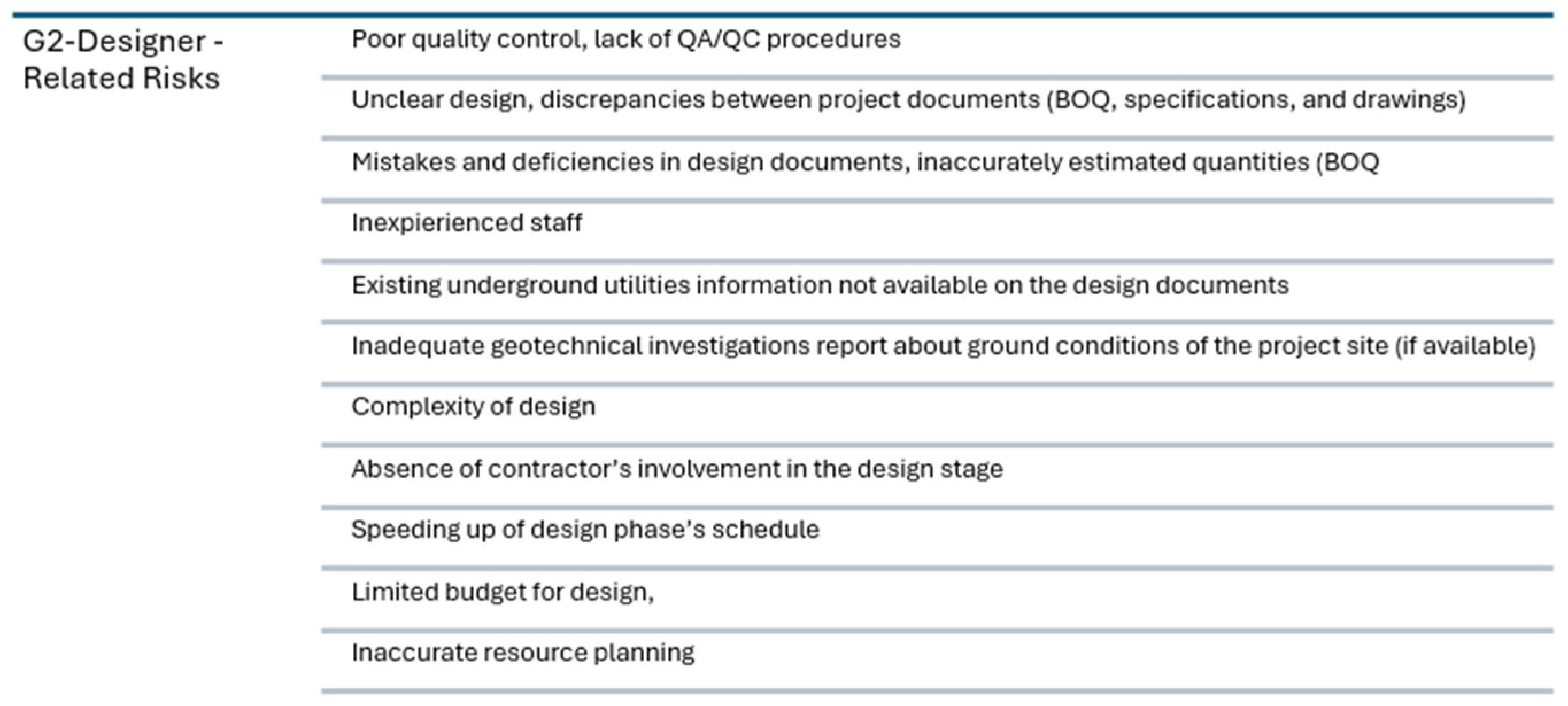

A more construction-relevant grouping was proposed by Alshihri et al. [

23], who classified 83 risk factors into nine categories based on the roles performed by the various parties and resources involved in the construction process, specifically within the context of government-funded projects (see

Figure 3). This approach appears particularly useful in the context of BIM, with the designer-related risk category providing a robust initial framework for identifying risks through data mining (see

Figure 4).

2.3. AI vs. ML

Speculation about the possibility of creating mechanical intelligence can be traced to several key figures—including Alan Turing, John von Neumann, and Norbert Wiener—during the period from 1943 to 1950. However, experimental research in artificial intelligence did not truly begin until electronic digital computers became widely accessible in the early 1950s [

24]. Today, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) are extensively applied in numerous domains, including data analysis, risk assessment, and inventory management. According to Jackson [

24], AI is a branch of computer science concerned with designing machines capable of intelligent behavior. In contemporary usage, the term AI generally refers to computer software that replicates human cognitive abilities to perform complex tasks historically undertaken by humans, such as decision-making, data interpretation, and language translation. Machine learning (ML) constitutes a subset of AI that employs data-driven algorithms to build models capable of executing these tasks. Although ML often enables many of the functions associated with AI and the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably, AI denotes the broader conceptual pursuit of human-like cognition in computational systems, whereas ML represents one specific method for achieving it. Machine learning is a subfield of artificial intelligence that enables algorithms to learn autonomously from data rather than through explicit programming. Practitioners train these algorithms to recognize patterns within datasets and to make decisions with minimal human intervention [

25].

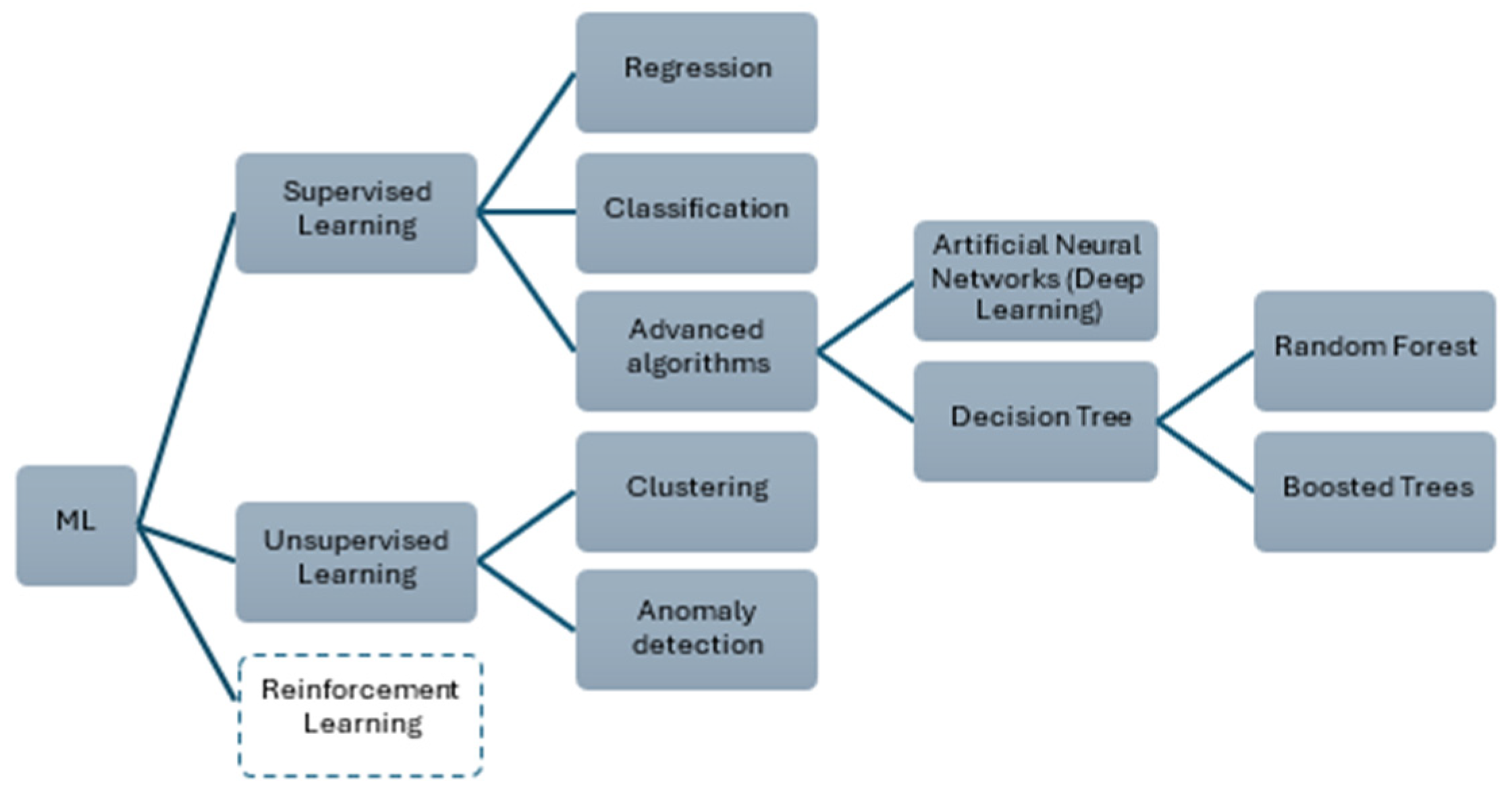

Machine learning is commonly divided into two main categories: supervised and unsupervised learning—as illustrated in

Figure 5. In supervised learning, algorithms are trained on labeled examples of inputs and their correct outputs—so that the model can later predict the output from new inputs alone. In contrast, unsupervised learning involves algorithms that receive only the input, unlabeled data and must independently discover patterns, structures, or groupings within it, such as clustering data into distinct categories. Within unsupervised learning, the two most common methods are clustering and anomaly detection, both of which appear promising in the context of BIM datasets.

2.4. BIM , Risk Management and AI

In recent years, a growing body of literature has examined the role of Building Information Modeling (BIM) technology in risk management[

5,

7,

26,

27]. The most prevalent applications primarily rely on 3D visualization [

3], which facilitates the identification and deeper understanding of potential issues related to design coordination, sustainability and site safety[

28]. A significant contribution in this regard comes from built-in software features that enable automated clash detection and rule-based checking [

4]. Another dimension frequently associated with BIM in the context of risk management is 4D modeling [

6], which incorporates construction sequencing to help mitigate risks related to buildability, construction scheduling, and subcontractor coordination. Moreover, many studies in BIM literature focus on factors contributing to delays [

11] or cost overruns [

8] and [

21]

A separate body of research has examined the integration of BIM and AI in general [

29,

30] , and more specifically the application of supervised deep learning methods, such as artificial neural networks (ANN), for predictive purposes [

22,

23,

24,

25] . Huang et al. [

9] utilized a trained BP neural network integrated with BIM technology to develop an evaluation model for risk management of public buildings.

Risk both emerges from uncertainty and, in turn, creates additional uncertainty through a lack of awareness or incomplete understanding [

20] . While labelling data requires prior explicit knowledge—meaning a level of certainty that a given correlation belongs to a specific category—in the case of BIM the point of reference is often not a single well-defined relationship but rather a complex set of interdependent variables.

Therefore, methods focused on pattern recognition and anomaly detection appear more promising, as they eliminate the initial bias associated with assigning rankings or predefined labels. In contrast, when applying supervised learning methods such as artificial neural networks (ANN) or decision trees, success depends on the initial labelling of the input data defining the value of y assigned to a particular x. These methods can offer efficient automated classification, but only when the dataset is well structured and there is confidence in the accuracy and consistency of the data descriptions.

2.5. Knowledge Discovery-Uncovering Hidden Pattern in BIM Data

With the growing use of information technology, the amount of data available to users has increased exponentially. Thus, there is a critical need to understand the content of the data. Knowledge is defined as a human understanding of a subject area, developed through the processing of data, the formulation of conclusions that become information, and the cultivation of insight into the problem domain.

The rapid expansion and vast accumulation of stored information in the construction industry, combined with the growing demand for data-driven analysis, has created an urgent need for advanced tools capable of extracting meaningful knowledge from large datasets to support building performance improvement.

With respect to data derived directly from BIM models, considerable attention has been directed toward quality control and object classification. Krijnen and Tamke [

16] demonstrated that unsupervised learning techniques can reveal anomalies in building models, and that a neural network can distinguish floor plan layouts into categories based on their geometric characteristics. García and Kamsu-Foguem [

13]applied clustering to physical room specifications extracted from BIM models to group rooms with similar thermal comfort profiles. Additional studies have further explored clustering methods for quality control [

14] ,site hazard identification[

34] and the automatic grouping of 3D objects according to trade classifications [

15]. Another study used BIM log files together with the K-means algorithm to identify modelling patterns and gain insights into user behavior [

35]. The studies summarized in

Table 2 provide an overview of engineering data processing themes and the computational methods employed for their analysis.

2.6. BIM Data Structure

A Building Information Model (BIM) is a virtual project simulation that integrates three-dimensional representations of building components with the information required for planning, procurement, construction, operation, and decommissioning. Virtual models fall into two categories: surface models and solid models. The latter—often referred to as

smart models—carry richer embedded information and are typically generated using solid or parametric modelers [

43]. Model intelligence arises from the fact that each digital object contains physical and contextual attributes, including geometry, dimensions, material properties, and spatial relationships to other components. Because this information is stored within each model element, it can be systematically retrieved, queried, and used for downstream processes, thus constituting an object-based or parametric modeling environment. Parametric links ensure that information associated with a model element is automatically updated throughout the project model. As a result, any modification to a building component is consistently reflected across all dependent representations—such as drawings, schedules, and 3D views—supporting a high degree of accuracy and reducing the potential for documentation inconsistencies.

Information embedded in model element can be broadly classified into three categories:

- (1)

geometric attributes,

- (2)

predefined parametric attributes, and

- (3)

user-defined parametric attributes.

Geometric attributes are automatically generated and continuously updated by the modeling software when constraints or object boundaries are modified. For instance, altering the edge of a slab will automatically update its volume, area, or other geometric properties derived. Parametric attributes, by contrast, require user input and may take the form of textual descriptors (e.g., material type or concrete grade), boolean fields (e.g., yes/no parameters), or numerical expressions defined through formulas. These parameters enable the enrichment of model elements with semantic information essential for analysis, coordination, and decision-making.

A fundamental characteristic of BIM is its development through an iterative information feedback loop. As project participants progressively refine their contributions, the model evolves in terms of scope, level of detail, and interdependencies, resulting in a continual increase in the breadth and depth of available information. Assessing model readiness is therefore most meaningful at key project gateways—such as the completion of specific design stages or pre-tender validation—when decisions must reflect the limitations and maturity of the information available at that point in the project lifecycle.

3. Results

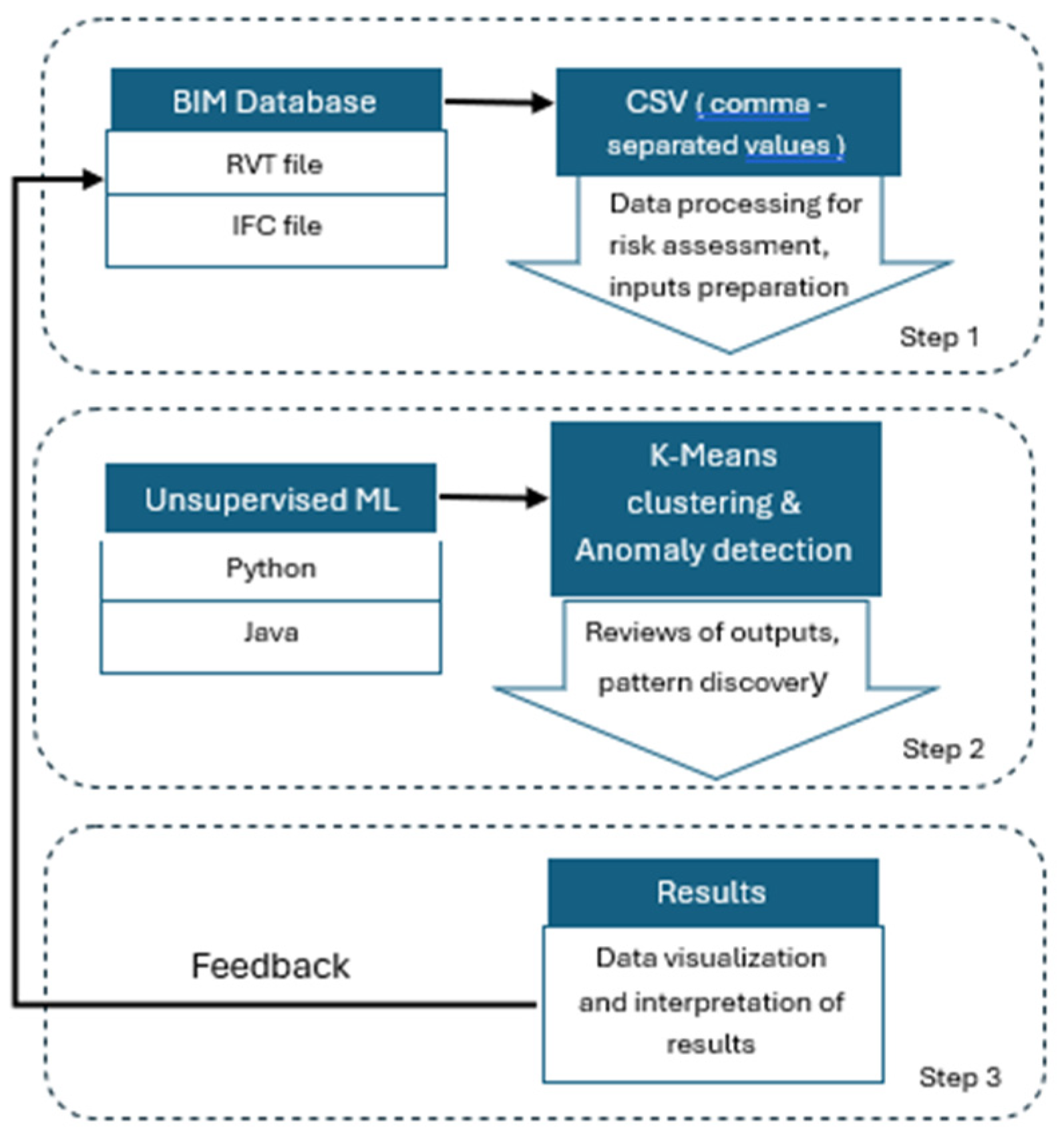

Concerning research on the application of BIM in risk management in combination with AI/ML, considerable attention has been devoted to predictive risk-related approaches, in which algorithms are typically trained on labelled datasets derived from expert judgment. At the same time, a substantial body of work has highlighted the need to better understand the information contained directly within digital models, whether in the context of quality control or building-permit approval. Methods such as K-means clustering and anomaly detection have already proven effective for analysing both geometric and parametric unlabelled data, enabling the identification of patterns and the extraction of meaningful insights.

In this context, both K-means clustering and anomaly detection are promising methods for further research.

Figure 6 presents the proposed framework, which is based on data extracted from an object-oriented parametric model and processed using an unsupervised machine learning algorithm, which will be subject of future dedicated research.

4. Discussion

Risk is a critical consideration in construction projects, and ultimately the project owner typically assumes responsibility for most of that risk. The objectives of a construction project typically reflect the needs and aspirations of the client, as most building initiatives are commissioned by an individual, an organization, or a community. The primary goal of all project teams must therefore align with supporting the owner in achieving the intended functional or strategic outcomes—such as enhancing educational or healthcare facilities, improving industrial productivity, or strengthening community infrastructure. Secondary objectives, including improving project quality, increasing construction efficiency in terms of time and cost, enhancing safety, or reducing construction-related risks, become shared team goals that add value to the overall project and contribute to the successful realization of the owner’s broader aims.

A model-based BIM process, as a key component of both the design and construction development, reflects not only the technical competencies of project team but also the level of software proficiency and the experience of those preparing and commissioning the model. Research conducted by Alnaser et al. [

8] as well as Gorski and Skorupka [

44]have demonstrated the significant role in risk generation played by the client at multiple stages of the process. Moreover, according to ISO standards [

45] , it is the client who is responsible for specifying the information requirements and modeling methodology [

46]which in return improve communication, facilitate better collaboration -critical factors in risk reduction. The design process is inherently a balancing act among competing requirements. However, excessive bureaucratic demands can divert designers’ attention away from addressing actual design problems and refining details, ultimately affecting the overall quality of both the model and the project.

Risk both emerges from uncertainty and, in turn, creates additional uncertainty through a lack of awareness or incomplete understanding [

20] . While labelling data requires prior explicit knowledge—meaning a level of certainty that a given correlation belongs to a specific category—in the case of BIM the point of reference is often not a single well-defined relationship but rather a complex set of interdependent variables. Therefore, methods focused on pattern recognition and anomaly detection appear more promising, as they eliminate the initial bias associated with assigning rankings or predefined labels. In contrast, when applying supervised learning methods such as artificial neural networks (ANN) or decision trees, success depends on the initial labelling of the input data defining the value of

y assigned to a particular

x. These methods can offer efficient automated classification, but only when the dataset is well structured and there is confidence in the accuracy and consistency of the data descriptions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zofia Feliksinska-Swierz and Artur Wirowski; Methodology, Zofia Feliksinska-Swierz; Investigation, Zofia Feliksinska-Swierz; Writing – original draft, Zofia Feliksinska-Swierz; Writing – review & editing, Anetta Kępczyńska-Walczak; Supervision, Anetta Kępczyńska-Walczak and Artur Wirowski.

Funding

The doctoral studies of the first author have been financially supported by a Technical University of Lodz, allowing for the completion of this research as part of the first author’s doctoral degree training at the Interdisciplinary Doctoral School in Lodz, Poland.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- The Standard for Project Management and a Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide); Project Management Institute, Inc., 2021; ISBN 9781628256642.

- Tabejamaat, S.; Ahmadi, H.; Barmayehvar, B. Boosting Large-Scale Construction Project Risk Management: Application of the Impact of Building Information Modeling, Knowledge Management, and Sustainable Practices for Optimal Productivity. Energy Sci Eng 2024, 12, 2284–2296. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, M.; Huang, G.; Liu, Q.; Zou, X.; Xu, X.; Guo, Z.; Li, C.; Lai, G. BIM-Based Integration and Visualization Management of Construction Risks in Water Pumping Station Projects. Buildings 2025, 15, 3573. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Kiviniemi, A.; Jones, S.W. A Review of Risk Management through BIM and BIM-Related Technologies. Saf Sci 2017, 97, 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Kiviniemi, A.; Jones, S.W. BIM-Based Risk Management: Challenges and Opportunities; 2015;

- Abanda, F.H.; Musa, A.M.; Clermont, P.; Tah, J.H.M.; Oti, A.H. A BIM-Based Framework for Construction Project Scheduling Risk Management. International Journal of Computer Aided Engineering and Technology 2020, 12, 182–218. [CrossRef]

- Aladayleh, K.J.; Aladaileh, M.J. Applying Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to BIM-Based Risk Management for Optimal Performance in Construction Projects. Buildings 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Alnaser, A.A.; Al-Gahtani, K.S.; Alsanabani, N.M. Building Information Modeling Impact on Cost Overrun Risk Factors and Interrelationships. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liang, C.; Liu, J. Research on Neural Network Prediction Model of Whole Process Risk Management Based on Building Information Model. Advances in Civil Engineering 2024, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nabawy, M.; Gouda Mohamed, A. Risks Assessment in the Construction of Infrastructure Projects Using Artificial Neural Networks. International Journal of Construction Management 2024, 24, 361–373. [CrossRef]

- Egwim, C.N. Applied Artificial Intelligence for Delay Risk Prediction of BIM-Based Construction Projects. PhD thesis, University of Hertfordshire: Hatfield, 2024.

- Khan, D.M.; Mohamudally, N.; Babajee, D.K.R. A Unified Theoretical Framework for Data Mining. In Proceedings of the Procedia Computer Science; Elsevier B.V., 2013; Vol. 17, pp. 104–113.

- Garcia, L.C.; Kamsu-Foguem, B. BIM-Oriented Data Mining for Thermal Performance of Prefabricated Buildings. Ecol Inform 2019, 51, 61–72. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, I.; Martins, J.P.; Castro, J.M. Quality Check of BIM Models Using Machine Learning. In 5o Congresso Português de Building Information Modelling Volume 2; UMinho Editora, 2024.

- Ali, M.; Mohamed, Y. A Method for Clustering Unlabeled BIM Objects Using Entropy and TF-IDF with RDF Encoding. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2017, 33, 154–163. [CrossRef]

- Krijnen, T.; Tamke, M. Assessing Implicit Knowledge in BIM Models with Machine Learning. In Modelling Behaviour; Springer International Publishing, 2015; pp. 397–406.

- Saunders, M.N.K..; Lewis, Philip.; Thornhill, Adrian. Research Methods for Business Students; Financial Times/Prentice Hall, 2007; ISBN 0273701487.

- Cagliano, A.C.; Grimaldi, S.; Rafele, C. Choosing Project Risk Management Techniques. A Theoretical Framework. J Risk Res 2015, 18, 232–248. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, I.; Kashani, H. Managing Cost Risks in Oil and Gas Construction Projects: Root Causes of Cost Overruns. ASCE ASME J Risk Uncertain Eng Syst A Civ Eng 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- PMI, P.M.Institute. Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects: A Practice Guide ; Project Management Institute, 2024; ISBN 9781628258165.

- William, L.; Jose, G.; Nelly, G.L. Enhancing Cost Reliability in Construction: The Synergistic Impact of BIM and Lean Principles. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, IGLC; International Group for Lean Construction, 2025; Vol. 33, pp. 141–152.

- Numan, M. BIM and Risk Management: A Review of Strategies for Identifying, Analysing and Mitigating Project Risks. Journal of Engineering Research and Sciences 2024, 3, 20–26. [CrossRef]

- Alshihri, S.; Al--gahtani, K.; Almohsen, A. Risk Factors That Lead to Time and Cost Overruns of Building Projects in Saudi Arabia. Buildings 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Jr.P.C. Introduction to Artificial Intelligence_Second, Enlarged Edition; 1985;

- Machine Learning | Coursera Available online: https://www.coursera.org/specializations/machine-learning-introduction#about (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Zou, Y. BIM and Knowledge Based Risk Management System. PhD thesis, University of Liverpool, 2017.

- Khatib, M.M. El; Alzoubi, H.M. BIM as a Tool to Optimize and Manage Project Risk Management; 2022;

- Hong, K.; Teizer, J. Digital Construction Site Layout Planning and Real-Time Trajectory Analysis for Proactive Safety Monitoring and Control of Struck-by Hazards. Autom Constr 2025, 177. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Han, G.; Demian, P.; Osmani, M. The Relationship Between Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Building Information Modeling (BIM) Technologies for Sustainable Building in the Context of Smart Cities. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16.

- Chong, H.Y.; Yang, X.; Goh, C.S.; Luo, Y. BIM and AI Integration for Dynamic Schedule Management: A Practical Framework and Case Study. Buildings 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Amrouni Hosseini, M.; Ravanshadnia, M.; Rahimzadegan, M.; Ramezani, S. Next-Generation Building Condition Assessment: BIM and Neural Network Integration. Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities 2024, 38. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Hammad, A.W.A.; Akbarnezhad, A.; Arashpour, M. A Neural Network Approach to Predicting the Net Costs Associated with BIM Adoption. Autom Constr 2020, 119. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, Y.; Li, L. Research on Cost Risk Management and Control of Prefabricated Buildings Based on BIM and BP Neural Network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings - 2022 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Everything, AIE 2022; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022; pp. 42–47.

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Novel Unsupervised Machine Learning Method for Identifying Falling from Height Hazards in Building Information Models through Path Simulation Sampling. Advances in Civil Engineering 2024, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, I.; Barreira, E.; Poças Martins, J.; Castro, J.M. Towards Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery for AECO Applications Using BIM Embedded Data: A Systematic Review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2025.

- Xiao, M.; Chao, Z.; Coelho, R.F.; Tian, S. Investigation of Classification and Anomalies Based on Machine Learning Methods Applied to Large Scale Building Information Modeling. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.K.; Kang, L.S. BIM Performance Assessment System Using a K-Means Clustering Algorithm. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 2021, 20, 78–87. [CrossRef]

- Noardo, F.; Wu, T.; Arroyo Ohori, K.; Krijnen, T.; Stoter, J. IFC Models for Semi-Automating Common Planning Checks for Building Permits. Autom Constr 2022, 134. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Lin, J.R.; Zhang, J.P.; Hu, Z.Z. A Hybrid Data Mining Approach on BIM-Based Building Operation and Maintenance. Build Environ 2017, 126, 483–495. [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y. K-Means Clustering-Enhanced 3D GIS–BIM Integration for Urban Rail Transit Planning: Evaluating Design Performance, Cost Efficiency, and Stakeholder Adoption. Geocarto Int 2025, 40. [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.; Shin, B.; Krijnen, T.F. Employing Outlier and Novelty Detection for Checking the Integrity of BIM to IFC Entity Associations. In Proceedings of the ISARC 2017 - Proceedings of the 34th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction; International Association for Automation and Robotics in Construction I.A.A.R.C), 2017; pp. 14–21.

- Kröhnert D; Allner L; Ross A; Kim W H Condensing Complexity K-Means Clustering of Geometric Data Sets as a Design Tool. In Proceedings of the Confluence -Proceedings of 43rd eCAADe Conference -Volume 1; Middle East Technical University, Department of Architecture: Ankara, September 2025; pp. 295–304.

- Kymmell, W. Building Information Modeling Planning and Managing Construction Projects with 4D CAD and Simulations; The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, 2008; ISBN 978-0071595452.

- Gorski, M.; Skorupka, D. Selected methods for identifying risk factors in comparison with project life cycle and construction investment process. Scientific Journal of the Military University of Land Forces 2011, 162, no.:4,2011, 307–324. [CrossRef]

- ISO ISO 19650-1 Organization and Digitization of Information about Buildings_Concepts and Principles; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, 2018;

- Feliksinska-Swierz, Z.; Kepczynska-Walczak, A. How Client’s Defined BIM Standards Facilitate Better Outcomes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Confluence -Proceedings of 43rd eCAADe Conference -Volume 1; Middle East Technical University, Department of Architecture: Ankara, September 2025; pp. 397–406.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).