1. Introduction

The world stands at an unprecedented urban threshold. By 2030, approximately 60% of humanity will reside in cities, representing 5 billion urban dwellers who will depend on increasingly complex and interconnected infrastructure systems [

1]. This rapid urbanization concentrates both opportunity and challenge within metropolitan boundaries. Cities generate over 80% of global gross domestic product (GDP) while simultaneously accounting for more than 70% of carbon emissions and consuming two-thirds of the world’s energy [

2]. The urban environments of 2030 will confront multifaceted challenges including chronic traffic congestion that costs major cities billions annually in lost productivity, acute housing shortages that price essential workers out of the communities they serve, deteriorating air quality that causes millions of premature deaths worldwide, aging infrastructures that require hundreds of billions in deferred maintenance, and climate change impacts ranging from intensifying heat waves to catastrophic flooding [

3,

4].

Digital Twin (DT) technology has emerged as a promising approach for transcending these limitations by creating virtual representations of physical urban systems that enable integrated monitoring, analysis, and planning. A DT functions as a dynamic software model that continuously updates to mirror the state of its physical counterpart through data streams from sensors, databases, and other information sources [

5,

6]. Urban planners use DTs to visualize complex infrastructure relationships, simulate the impacts of proposed interventions, and optimize operations across interconnected systems in ways that physical prototyping and traditional planning tools cannot support [

7,

8].

Cities worldwide have begun implementing DT platforms that demonstrate the technology’s potential for urban applications [

9,

10]. However, current implementations function primarily as sophisticated monitoring and analysis tools accessed by technical specialists rather than as immersive platforms that engage diverse stakeholders in collaborative urban governance. DTs operate largely in isolation from one another, with a transportation twin unaware of energy system constraints, a water management twin disconnected from land use planning, and public health surveillance separated from environmental monitoring. These systems provide decision support for human administrators rather than enabling automated proactive response that anticipates challenges before they escalate into crises requiring reactive intervention.

Recent developments at the convergence of DTs, metaverse technologies, edge computing, artificial intelligence (AI), and robotics create possibilities for fundamentally reconceiving urban management systems. The

metaverse represents shared virtual environments where users interact with digital content and with each other through immersive interfaces including virtual reality, augmented reality, and spatial computing [

11,

12]. While popular discourse often associates the metaverse with gaming and social media applications, the underlying technologies enable new paradigms for human-computer interaction that have profound implications for urban systems. When DTs operate within metaverse platforms, they transform from passive monitoring tools into immersive environments where stakeholders directly experience urban systems, collaborate in real-time despite physical distribution, explore scenarios through embodied interaction rather than abstract analysis, and influence system behavior through intuitive interfaces rather than technical command languages.

This paper articulates a vision for Metaverse-Enabled DIGital Twins Enterprise (MEDIGATE) that fundamentally transforms urban management from passive monitoring to proactive, collaborative, and citizen-engaged governance. We argue that integrating DT technology with metaverse platforms, edge computing, AI, and robotic actuation enables a new architecture for smart cities that creates capabilities impossible with current approaches. Immersive interfaces allow stakeholders to experience urban systems spatially and temporally in ways that conventional dashboards and reports cannot convey, enabling intuitive understanding of complex relationships and tradeoffs. Multi-modal information fusion across text, audio, video, sensor data, and immersive interaction synthesizes insights invisible to isolated analysis. Real-time collaboration within shared virtual environments supports distributed decision-making that transcends the constraints of physical meetings. Closed-loop systems that continuously sense conditions, predict developments through DT simulation, engage stakeholders through metaverse platforms, execute automated responses through robotic actuation, and learn from outcomes enable genuinely proactive urban management that anticipates challenges before they escalate.

This paper makes several contributions to the discourse on smart city futures. We present a conceptual framework that articulates how DTs, metaverse platforms, edge computing, AI, and robotics integrate to enable proactive urban management. We introduce the microverse concept as a practical implementation pathway that cities can pursue incrementally. We examine healthcare as an illustrative domain that demonstrates key principles while acknowledging that similar transformations apply across urban systems. This paper identifies technical challenges and research directions spanning computer science, urban planning, and social sciences. The paper explores ethical considerations around privacy, equity, transparency, and governance that must inform system design rather than being addressed as afterthoughts. Finally, a research agenda is presented that encompasses not only technical development but also the social innovations and policy frameworks necessary for responsible deployment.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows, shown by

Table 1.

Section 2 examines the current state of DT implementations in smart cities, analyzing representative deployments to establish both achievements and fundamental limitations of existing approaches.

Section 3 presents the MEDIGATE four-layer architectural framework in detail, explaining how each layer functions and how their integration creates emergent capabilities for proactive urban management.

Section 4 introduces the microverse concept and outlines a practical pathway for incremental implementation that builds from domain-specific deployments toward comprehensive urban-scale integration.

Section 5 explores healthcare as an illustrative domain, demonstrating through concrete scenarios how metaverse-enabled DTs transform service delivery.

Section 6 addresses the technical foundations and enabling technologies that make this vision feasible while identifying current limitations and required advances.

Section 7 examines challenges spanning privacy, security, reliability, equity, and governance, framing these as research opportunities rather than insurmountable obstacles.

Section 8 synthesizes our argument and articulates next steps toward realizing genuinely proactive smart cities that anticipate needs, engage citizens meaningfully, and deliver equitable outcomes.

2. Current State of Digital Twins in Smart Cities

The evolution of DT technology from its origins in aerospace engineering to contemporary urban applications represents a significant trajectory of conceptual and technical development. Understanding the DT evolution and examining current implementations reveals both the substantial achievements of existing approaches and their fundamental limitations that necessitate an architectural reconceptualization.

Section 2 critically analyzes representative urban DT deployments to establish the current state of practice and articulate why incremental improvements to existing paradigms prove insufficient for addressing the challenges that future cities will confront.

2.1. Historical Context and Technological Evolution

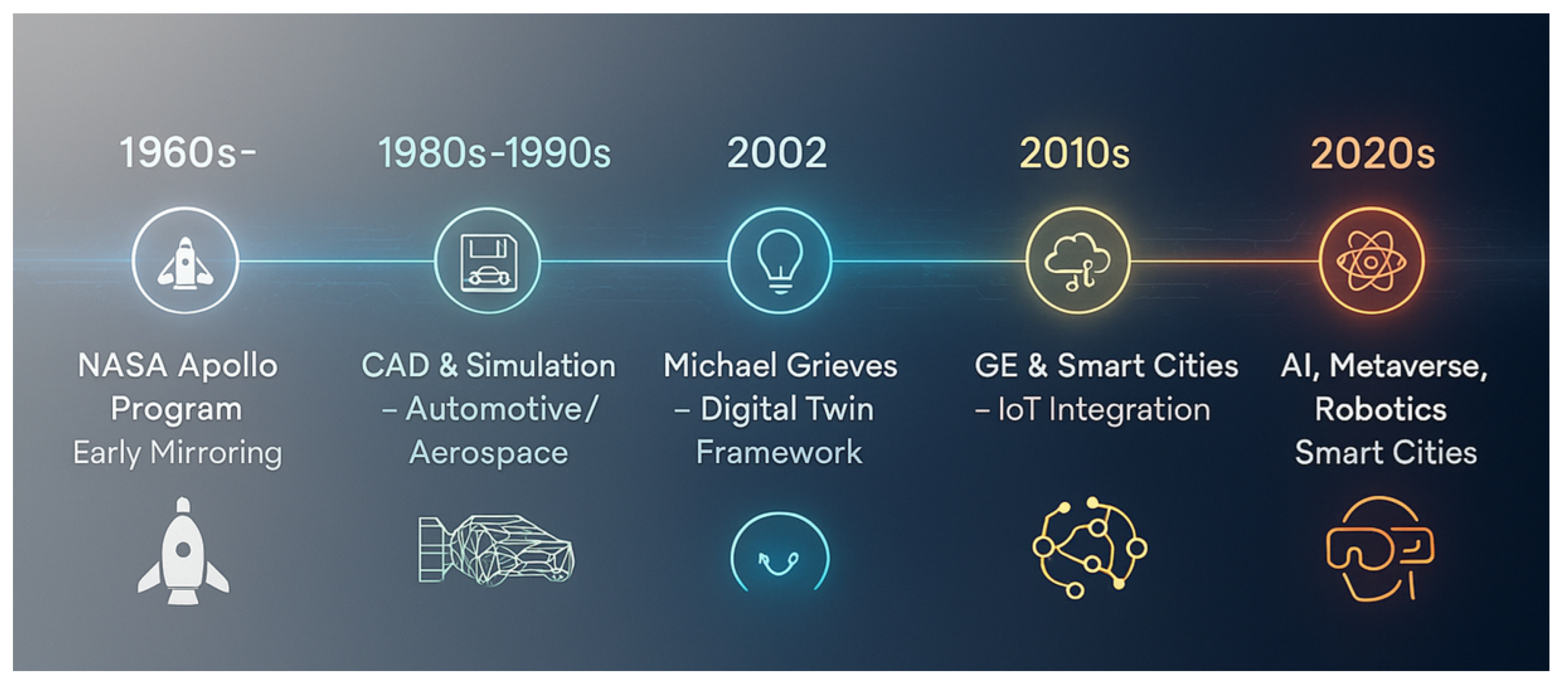

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the DT concept originated in the early years of space exploration when NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) engineers created physical replicas of spacecraft systems on Earth to mirror and diagnose problems occurring in orbit during the Apollo missions [

13]. These physical twins enabled ground-based analysis and simulation that proved essential for troubleshooting critical systems in environments where direct human intervention was impossible. As computing capabilities advanced through the 1980s and 1990s, engineers in automotive and aerospace manufacturing began replacing physical twins with computer-aided design (CAD) models and simulation environments that could predict product performance before physical prototypes existed [

14]. The formal articulation of DT principles emerged in the early 2000s through the work of Michael Grieves at the University of Michigan, who defined DT as comprising a physical product, a virtual representation of that product, and bidirectional data connections between them [

5].

The application of DT concepts to urban systems represents a natural extension of industrial practice to spatial domains of unprecedented complexity. Cities encompass millions of interconnected components spanning buildings, transportation networks, utility infrastructure, communication systems, and environmental processes, all operating simultaneously across spatial scales from individual structures to metropolitan regions. Early

urban DT initiatives focused on creating three-dimensional geometric models that provided planning and visualization capabilities. The City of Zürich developed a detailed virtual city model in the 1990s primarily for urban planning visualization [

15]. Singapore launched its Virtual Singapore initiative in 2014 as one of the first comprehensive attempts to create a dynamic, data-driven DT of an entire city rather than merely a static geometric representation [

16].

Contemporary urban DTs have evolved beyond geometric visualization to incorporate real-time sensor data, predictive analytics, and simulation capabilities. The integration of Internet of Things (IoT) sensor networks enables DTs to continuously update their representation of physical system states rather than depending on periodic manual surveys. Machine learning (ML) models process historical and real-time data to predict future conditions ranging from traffic congestion to equipment failures. Simulation engines evaluate proposed interventions before physical implementation, reducing the risk and cost of urban infrastructure decisions. Cloud computing platforms provide the computational resources necessary to maintain complex models and serve multiple simultaneous users. These technological advances have enabled DTs to transition from static planning tools to dynamic operational platforms that support ongoing urban management [

9,

17].

2.2. Contemporary Urban Digital Twin Implementations

Examining specific implementations reveals both the capabilities and limitations of current urban DT practice.

Virtual Singapore represents one of the most comprehensive and frequently cited examples. The platform integrates three-dimensional (3D) geometric models of buildings, infrastructure, and terrain with real-time data from sensors monitoring traffic flow, weather conditions, and environmental parameters across the island nation [

16]. Government agencies and authorized private sector partners use Virtual Singapore for diverse applications including urban planning scenario analysis, infrastructure optimization, emergency response planning, and public engagement visualization. Urban planners simulate the environmental impacts of proposed high-rise developments by modeling how new buildings affect wind patterns, solar exposure, and views in surrounding areas. Transportation authorities evaluate how road closures for construction projects will affect traffic patterns throughout the network. Emergency managers simulate evacuation scenarios to identify bottlenecks and optimize response procedures for various disaster situations [

18].

Despite its sophistication, Virtual Singapore exhibits limitations characteristic of current DT implementations. The platform functions primarily as an analysis and visualization tool accessed by trained specialists rather than as an immersive environment supporting broad stakeholder participation. While the 3D interface provides superior spatial understanding compared to two-dimensional maps and dashboards, users interact with the system through conventional computer screens using mouse and keyboard controls that maintain considerable distance between the user and the virtual environment. Citizens have limited ability to access or interact with Virtual Singapore directly, instead experiencing curated presentations prepared by government officials or urban planners. The Virtual Singapore DT operates largely independent from operational control systems, providing decision support recommendations that human administrators must manually implement rather than directly executing interventions in physical infrastructure. Integration across different urban systems remains partial, with transportation, environmental, and infrastructure twins maintaining separate data models and simulation engines that make holistic optimization challenging [

8].

The City of Toronto and York Region’s DT for water systems management demonstrates different capabilities and faces different constraints.

Toronto water system DT implementation focuses specifically on hydrological modeling to predict flood risks hours before events occur, enabling proactive response rather than purely reactive emergency management [

19]. The system integrates data from weather forecasts, stream gauges, soil moisture sensors, and infrastructure monitoring systems with sophisticated hydraulic models that simulate how precipitation will flow through watersheds, drainage networks, and treatment facilities. When the models predict flooding risks exceeding defined thresholds, the system automatically alerts emergency management personnel who can pre-position equipment, implement temporary protective measures, and notify potentially affected residents well before water levels become dangerous. The economic benefits of this advance warning have proven substantial by preventing property damage and reducing emergency response costs.

However, the Toronto water system DT also illustrates the siloed nature of current implementations. While the platform excels at hydrological prediction, it operates largely independently from other urban systems that both affect and are affected by water management. Transportation networks experience significant disruption during flooding events, yet the water DT does not directly interface with traffic management systems to implement coordinated response such as closing vulnerable roadways before flooding occurs or rerouting traffic to maintain emergency access. Power utilities need to protect electrical infrastructure from water damage, but integration between the water twin and electrical grid management remains limited. Building management systems could activate protective measures such as deploying flood barriers or moving equipment to higher floors, yet these systems typically receive flood warnings through the same public notification channels available to all citizens rather than through direct machine-to-machine communication that would enable faster automated response. The lack of integration across urban domains reflects organizational boundaries between municipal departments and agencies more than technical limitations, but the result is DTs that optimize individual systems without enabling holistic urban management [

20].

Dubai smart building management DTs have been implemented across thousands of structures as part of its broader smart city initiative. These building-level twins monitor energy consumption, heating and cooling system performance, lighting, occupancy patterns, and equipment health to optimize operational efficiency and predict maintenance needs [

21]. The integration of building information models with real-time sensor data enables facility managers to identify anomalies indicating equipment degradation before failures occur, schedule maintenance during periods of low occupancy to minimize disruption, and optimize energy consumption by coordinating Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems with occupancy predictions and weather forecasts. The aggregated data from thousands of buildings provides city-wide insights into energy consumption patterns that inform infrastructure planning and policy development. Buildings participating in demand response programs can automatically modulate consumption in response to grid conditions, helping balance electricity supply and demand.

The Dubai building twins demonstrate operational value at the structure level but reveal limitations in urban-scale integration. Individual buildings optimize their own performance without coordinating with neighboring structures or district-scale systems that might enable shared resource utilization. Building cooling systems operate independently despite opportunities for thermal energy sharing through district cooling networks. Rooftop solar installations on individual buildings do not coordinate with building energy storage or electric vehicle charging to optimize neighborhood-level grid interaction. The building twins focus narrowly on operational efficiency without incorporating broader urban factors such as transportation access, air quality impacts on occupant health, or resilience to climate extremes that require integration with city-wide environmental monitoring and emergency management systems [

22].

Helsinki’s Kalasatama district DT represents an effort to address integration challenges by focusing on a specific geographic area rather than attempting city-wide coverage. The district twin incorporates buildings, infrastructure, transportation, and environmental systems within a defined urban neighborhood undergoing significant development [

23]. Urban planners use the platform to evaluate how proposed developments affect the existing community by simulating changes to traffic patterns, pedestrian flows, sunlight exposure, and local climate conditions. Energy planners optimize district heating networks and evaluate renewable energy integration scenarios. Transportation authorities coordinate public transit services with development patterns and mobility demand. The geographic focus enables deeper integration between systems within the district while establishing patterns that could expand to broader urban coverage over time.

However, even a spatially focused approach encounters challenges that reveal deeper architectural limitations. The Kalasatama DT serves primarily as a planning and analysis tool used during the development process rather than as an ongoing operational platform that adapts in real-time to changing conditions. Citizens participate through consultation processes where planners present simulation results rather than directly interacting with the DT to explore scenarios and express preferences. The platform provides limited support for automated response, with insights that inform human decisions rather than directly controlling infrastructure. As the district matures from active development to ongoing operation, sustaining the DT requires organizational models and funding mechanisms that differ from project-based planning efforts [

24].

2.3. Systematic Limitations of Current Approaches

Analysis across these and other contemporary implementations reveals several systematic limitations that constrain the transformative potential of DT technology for urban management. These limitations stem from fundamental architectural choices rather than temporary technical constraints, suggesting that incremental improvements to existing approaches will prove insufficient unless there is a middleware to connect the DTs.

Current DTs function predominantly as monitoring and analysis tools that support human decision-making rather than as platforms enabling direct stakeholder interaction and automated intervention. Technical specialists access DT platforms through conventional computer interfaces, interpret model outputs and simulation results, and translate insights into recommendations for decision-makers. The human-machine workflow introduces delays between sensing conditions, analyzing situations, making decisions, and implementing responses that prevent truly proactive management. When a transportation DT predicts congestion based on event schedules and weather forecasts, traffic management staff must manually adjust signal timing, implement lane controls, and communicate with drivers through variable message signs. The prediction provides valuable advance warning but the response remains fundamentally reactive, occurring after conditions have begun deteriorating rather than pre-emptively adapting to prevent problems from developing.

The isolation of individual DTs prevents holistic optimization across interdependent urban systems.

Transportation twins optimize traffic flow without considering how routing decisions affect air quality in residential neighborhoods or how electric vehicle charging concentrations stress electrical distribution networks.

Energy twins minimize cost and emissions without accounting for how demand response programs affect building occupant comfort or manufacturing production schedules.

Water management twins operate independently from land use planning that determines impervious surface coverage affecting runoff patterns. Public health surveillance remains disconnected from environmental monitoring that reveals exposure to pollutants affecting disease incidence. These silos reflect organizational structures where different agencies manage different urban systems, but the result is suboptimal outcomes compared to what integrated management could achieve [

7,

25].

Limited stakeholder engagement constrains the democratic legitimacy and social acceptance of DT-informed decisions. Citizens experience smart city initiatives as passive consumers receiving services rather than as active participants shaping their communities. Urban planning consultations present simulation results through two-dimensional visualizations and verbal descriptions that fail to convey the experiential reality of proposed changes. Residents cannot directly explore how alternative development scenarios would affect their neighborhood character, property values, or quality of life. Community groups lack tools for constructing counter-proposals informed by the same analytical rigor that professional planners employ. The technical sophistication of DT platforms creates asymmetries of knowledge and power that can undermine trust even when officials act with good intentions [

26,

27].

The lack of

immersive interfaces prevents intuitive understanding of complex urban systems. Conventional dashboards display data through charts, maps, and tables that require training to interpret correctly. Relationships between variables must be inferred from correlations rather than experienced directly. Temporal dynamics appear as time series graphs rather than as animated sequences showing system evolution. Spatial relationships emerge from map overlays rather than from 3D environments that preserve the geometric and topological properties of physical space. This abstraction distances stakeholders from the systems they seek to understand and manage, making it difficult to develop the intuitive comprehension necessary for effective decision-making in complex situations [

28].

The reactive rather than anticipatory nature of current implementations limits DT’s ability to prevent problems before they escalate. DTs excel at detecting anomalies and predicting future states based on current conditions, but they lack mechanisms for proactive intervention that shapes conditions to avoid predicted problems. When models forecast equipment failure in three weeks, maintenance must be manually scheduled. When simulations predict traffic congestion during an upcoming event, mitigation measures require human planning and implementation. The gap between prediction and action creates opportunities for organizational delays, communication failures, and competing priorities to prevent timely response. Truly proactive systems would sense emerging conditions, simulate alternative responses, select optimal interventions, execute actions through automated actuation, and learn from outcomes to improve future performance, all with minimal human intervention except for high-stakes decisions requiring ethical judgment or political accountability [

29].

2.4. The Need for Architectural Reconceptualization

These systematic limitations suggest that realizing the full potential of DT technology for urban management requires more than incremental improvements to existing platforms. Adding more sensors provides finer-grained monitoring but does not address the reactive nature of current systems. Improving visualization capabilities enhances analysis without enabling immersive interaction. Expanding to additional urban domains increases coverage without necessarily achieving integration. Cloud computing and AI deliver greater computational power and analytical sophistication while leaving the fundamental architecture of human-mediated decision-making intact.

The vision articulated in subsequent sections reconceives DTs as immersive platforms integrated with metaverse environments, edge intelligence, and robotic actuation rather than as monitoring and analysis tools operating in isolation. This reconceptualization addresses the limitations identified above by enabling stakeholders to directly experience urban systems through immersive interfaces rather than interpreting abstract visualizations by integrating information across urban domains through common platforms and data models rather than maintaining isolated silos. Engaging citizens as active participants through accessible immersive environments rather than relegating them to passive service consumption can anticipate challenges through continuous sensing and prediction coupled with automated proactive response rather than relying on reactive human intervention, as well as learning continuously from outcomes to improve system performance rather than treating each intervention as an isolated event.

The following Section presents the architectural framework that enables these capabilities by articulating how physical infrastructure, DTs, metaverse platforms, and action-taking systems integrate to create genuinely proactive smart cities. Before examining that framework in detail, it is essential to recognize that current DT implementations have delivered substantial value and represent important progress from previous urban management approaches. The critique presented above is not intended to diminish those achievements but rather to articulate why the next generation of smart city platforms requires fundamental architectural innovation rather than evolutionary refinement. The convergence of technologies, including immersive computing (i.e., virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), mixed reality (MR), extended reality (XR)), edge intelligence, AI, and robotics, creates possibilities that were infeasible when current DT platforms were designed. By reconceiving urban DTs to exploit these emerging capabilities, cities can progress from reactive monitoring to proactive management that anticipates challenges, engages stakeholders meaningfully, and delivers equitable outcomes for all urban residents.

3. Architectural Framework for Proactive Smart Cities

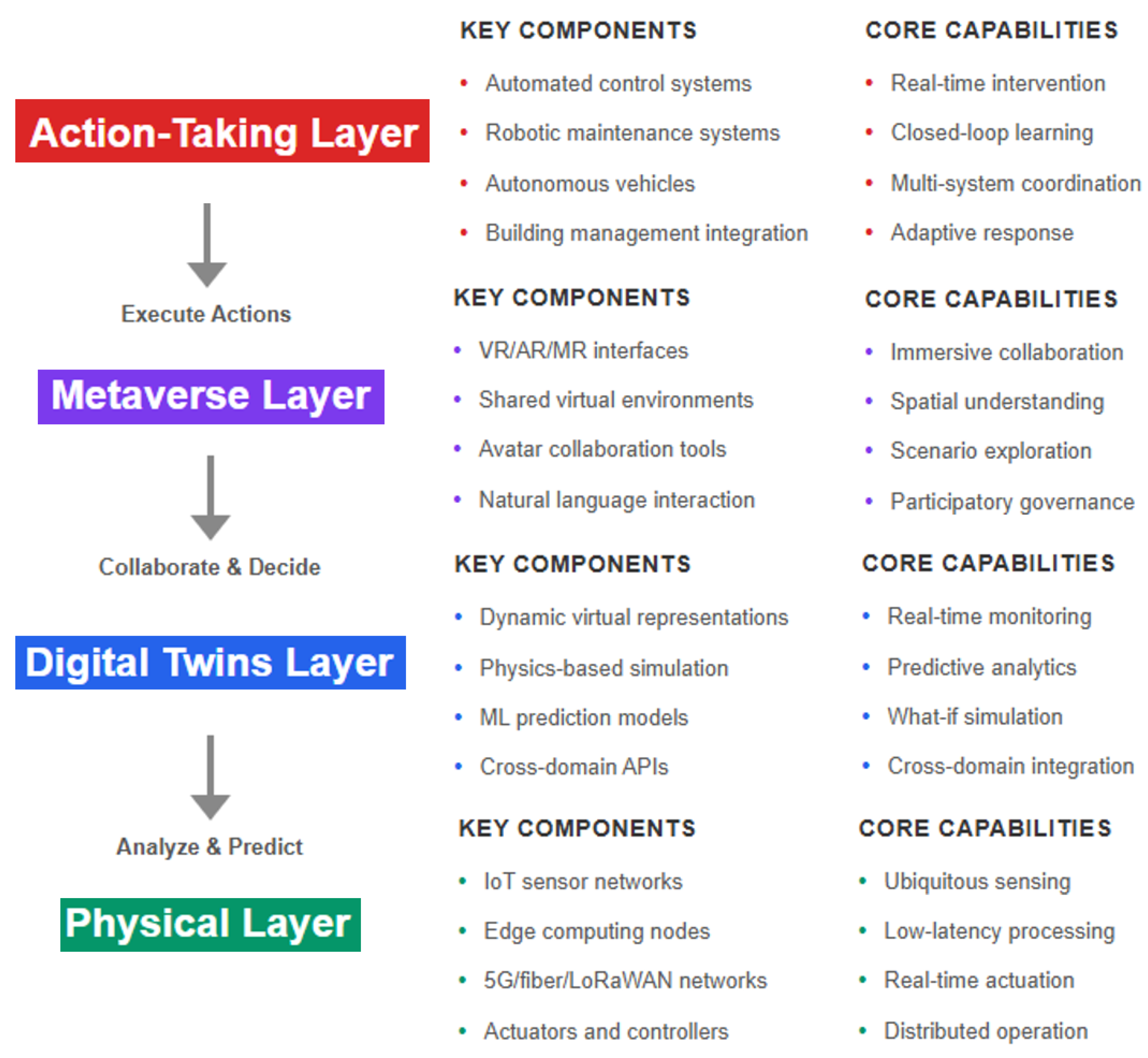

The limitations of current DT implementations identified in the previous section stem from architectural choices that position these systems as passive monitoring and analysis tools rather than as active platforms enabling immersive interaction and automated response. Overcoming these limitations requires a fundamental reconceptualization of how digital technologies integrate to support urban management. As illustrated in

Figure 2, this Section presents a four-layer Metaverse-Enabled DIGital Twins Enterprise (MEDIGATE) architectural framework that enables the transformation from passive mirroring to proactive immersion by articulating how physical infrastructure, DTs, metaverse platforms, and action-taking systems work in concert to create capabilities that no isolated technology can achieve. Each layer performs distinct functions while exposing interfaces that enable tight integration with other layers, producing emergent properties that characterize genuinely proactive smart cities.

3.1. Physical Layer: The Sensing and Actuation Substrate

The physical layer serves as the foundation of proactive urban systems, providing the sensory awareness and actuation capabilities necessary for real-time monitoring and intervention. This layer comprises IoT devices, communication networks, edge computing infrastructure, and robotic systems distributed throughout the urban environment. While conventional smart city architectures include similar components, the physical layer in the MEDIGATE framework differs fundamentally in its emphasis on local intelligence, low-latency response, and bidirectional interaction rather than merely collecting data for centralized processing.

IoT sensor networks enable continuous monitoring of urban conditions across diverse domains. Environmental sensors measure air quality parameters, including particulate matter concentrations, nitrogen dioxide levels, ozone, and volatile organic compounds that affect public health and quality of life [

30]. Transportation sensors monitor vehicle flows, travel speeds, parking occupancy, and public transit ridership through technologies that include inductive loops, cameras with computer vision processing, and cellular network analytics. Building management systems track energy consumption, occupancy patterns, temperature, humidity, and equipment performance across thousands of structures. Utility infrastructure sensors monitor water pressure and flow rates, electrical grid voltage and current, and natural gas distribution. Public safety systems integrate video surveillance, acoustic gunshot detection, and emergency alert mechanisms. Personal devices, including smartphones and wearables, provide individual-level data about mobility patterns, physiological states, and user preferences when citizens consent to sharing this information [

31].

The scale and diversity of urban sensing create data volumes that centralized processing cannot handle within the latency constraints required for real-time response. A metropolitan area of several million residents might generate terabytes of sensor data daily from millions of devices. Transmitting all this raw data to cloud data centers for processing introduces communication delays, consumes excessive bandwidth, and creates single points of failure that compromise system resilience. Edge computing addresses these challenges by distributing intelligence throughout the urban environment, processing data near where it originates rather than centralizing computation in remote facilities [

32,

33].

Edge computing nodes deployed at strategic locations, including cellular base stations, traffic signal controllers, building management systems, and utility substations, perform local analytics that extract actionable insights from raw sensor streams. A traffic management edge node analyzes video feeds from intersection cameras to detect congestion, accidents, and unusual patterns, transmitting only summarized information and alerts rather than raw video to centralized systems. An environmental monitoring edge node correlates measurements from multiple air quality sensors to identify pollution sources and predict dispersion patterns, triggering local alerts when thresholds are exceeded. A building management edge node optimizes heating, cooling, and lighting based on occupancy predictions and weather forecasts without requiring constant communication with centralized building automation systems. This distributed intelligence enables subsecond response times impossible with centralized architectures while reducing communication bandwidth requirements and improving system resilience to network failures [

34].

The physical layer of our MEDIGATE framework extends beyond sensing and computation to encompass actuation mechanisms that enable automated intervention in urban systems. Traffic signal controllers adjust timing patterns in response to real-time flow conditions detected by local sensors and predicted by DT models. Building management systems modulate energy consumption by adjusting thermostat setpoints, dimming lighting, and shifting flexible loads in response to grid conditions and occupancy patterns. Water management systems operate valves and pumps to optimize pressure, prevent contamination, and respond to leak detection. Intelligent streetlights adjust brightness based on pedestrian and vehicle presence while serving as communication nodes and sensor platforms. Autonomous vehicles and delivery robots execute transportation and logistics tasks coordinated through DT platforms. Industrial robots perform infrastructure maintenance and inspection tasks in hazardous environments where human access is difficult or dangerous [

35,

36].

Communication networks bind these distributed components into coherent systems capable of coordinated action. Fifth-generation cellular networks provide high-bandwidth, low-latency wireless connectivity supporting mobile applications and dense sensor deployments [

37]. Fiber optic infrastructure delivers the backhaul capacity necessary for aggregating data from edge nodes and supporting high-resolution video and immersive experiences. Low-power wide-area networks, including Long Range Wide Area Network (LoRaWAN) and Narrowband IoT (NB-IoT), enable long-lived battery-powered sensors deployed in locations where power infrastructure access is impractical. Mesh networking protocols allow devices to relay communications through peers when direct infrastructure connectivity is unavailable, improving resilience and extending coverage. Network slicing capabilities partition physical infrastructure into virtual networks optimized for specific applications, ensuring that critical public safety communications receive guaranteed bandwidth and latency even when consumer applications create congestion [

38].

The physical layer design prioritizes several architectural principles that distinguish proactive urban systems from conventional smart city infrastructures. Local autonomy enables subsystems to function effectively even when connectivity to centralized systems is disrupted, preventing single points of failure from cascading through the urban environment. Standardized interfaces allow components from different vendors to interoperate, avoiding vendor lock-in and enabling incremental system evolution. Security mechanisms, including authentication, encryption, and intrusion detection, protect against malicious attacks that could compromise critical infrastructure [

39]. Privacy preservation techniques, including differential privacy and federated learning, enable valuable analytics while protecting sensitive information about individual citizens [

40]. Energy efficiency through careful hardware selection and software optimization extends the lifespan of battery-powered sensors and reduces the environmental impact of large-scale IoT deployments.

3.2. Digital Twins Layer: Predictive Insight and Simulation

The DTs layer builds upon the physical layer foundation by creating virtual representations of urban systems and generating predictive insights through simulation and AI. While this layer performs functions similar to current DT implementations, its design in our MEDIGATE framework differs by emphasizing continuous real-time operation, horizontal integration across urban domains, and tight coupling with both the underlying physical layer and the overlying metaverse, as well as action-taking layers.

DTs in the MEDIGATE architecture maintain dynamic virtual replicas of physical urban systems that continuously update as sensors report changing conditions, rather than being refreshed periodically for specific analysis tasks. A

transportation DT incorporates real-time information about vehicle locations, traffic signal states, road closures, public transit operations, and parking availability, updating its representation multiple times per second as conditions evolve. An

energy DT tracks electricity generation from conventional and renewable sources, transmission and distribution network states, building consumption patterns, and storage system charge levels, maintaining a current view of grid conditions that enables rapid response to disturbances. A

water management DT monitors reservoir levels, treatment plant operations, distribution network pressures and flows, and consumption across the service area, detecting anomalies that might indicate leaks or contamination within minutes of occurrence [

41].

These virtual representations serve multiple purposes beyond visualization. Physical twins enable operators to monitor system states through intuitive interfaces that present complex information more comprehensibly than raw data streams.

Predictive twins apply ML models to forecast future conditions based on current states and historical patterns, warning of potential problems hours or days before they manifest.

Experimental twins allow planners to evaluate proposed interventions through simulation before physical implementation, reducing risk and cost.

Optimization twins search large solution spaces to identify configurations that maximize performance according to specified objectives such as minimizing cost, reducing emissions, or improving equity [

6].

AI/ML technologies enable DTs to generate insights that would be invisible to traditional analysis approaches. Supervised learning models trained on historical data predict traffic congestion, energy demand, equipment failures, and public health trends with accuracy that improves as training datasets grow. Unsupervised learning techniques identify anomalous patterns that might indicate emerging problems such as water main degradation, electrical equipment malfunction, or disease outbreak precursors. Reinforcement learning algorithms discover optimal control strategies for complex systems, including adaptive traffic signal timing, building energy management, and grid stability control by exploring alternative policies through simulation and learning from outcomes [

42].

The horizontal integration of DTs across urban domains represents a crucial distinction from current implementations that typically operate in isolation. In the MEDIGATE framework, DTs expose standardized application programming interfaces that allow other twins to query their state, subscribe to updates, and request simulations. A transportation DT considering route recommendations for electric vehicles queries the energy DT about charging station availability and grid conditions that might affect charging speeds. A building management DT optimizing energy consumption receives air quality forecasts from the environmental DT indicating when opening windows for natural ventilation would expose occupants to harmful pollutants. A

public health DT monitoring disease transmission patterns accesses the transportation DT to understand mobility flows that might explain geographic spread patterns [

22].

DT integration enables system-level optimization, which is impossible when individual domains operate independently. Consider a scenario where an approaching storm threatens to create both traffic congestion through accidents and flooding through overwhelmed drainage systems. The weather DT predicts precipitation timing and intensity. The water management DT simulates drainage system response and identifies areas at risk of flooding. The transportation DT evaluates how road closures and detours would affect traffic patterns. The

emergency management DT coordinates response resources. Rather than each system responding independently, the integrated twins collaboratively develop a coordinated response that pre-positions emergency equipment, implements traffic restrictions that keep vehicles away from flood-prone areas, adjusts drainage system operations to maximize capacity, and alerts residents in affected areas hours before dangerous conditions develop. This holistic system-level DT delivers outcomes superior to what isolated domain optimization can achieve [

43].

The DTs layer maintains

physics-based simulation models alongside data-driven ML approaches to leverage the complementary strengths of each paradigm. Physics-based models encode expert knowledge about how systems behave according to fundamental principles including conservation laws, thermodynamics, and fluid dynamics. These models provide reliable predictions for conditions within their validated operating ranges and offer interpretable explanations for their outputs. However, they require detailed parameterization and may struggle with complex phenomena difficult to model from first principles. Data-driven ML approaches discover patterns directly from observations without requiring explicit physics models. They can capture complex nonlinear relationships and adapt to changing conditions through continuous learning. However, they may produce unreliable predictions when applied beyond their training distributions and offer limited interpretability regarding why they make particular predictions. Hybrid approaches, such as Dynamic Data Driven Applications Systems (DDDAS) [

44] that combine physics-based and data-driven methods, increasingly demonstrate superior performance by using physics models to constrain ML to produce physically plausible predictions while using data to refine physics model parameters and capture phenomena that first-principles modeling cannot address [

45].

The design of the DTs layer prioritizes several architectural principles of scalability, modularity, composability, and certainty. Scalability ensures that twins can represent metropolitan areas containing millions of components without computational performance degrading unacceptably. Modularity allows individual subsystem twins to be updated or replaced without requiring modification to the entire system. Composability enables complex twins to be constructed from simpler components that can be reused across different applications. Validation mechanisms ensure that twin predictions align with observed physical system behavior through continuous comparison and model calibration. Uncertainty quantification (UQ) provides confidence intervals around predictions rather than point estimates, enabling risk-aware decision-making that accounts for model limitations.

3.3. Metaverse Layer: Immersive Collaboration and Engagement

The metaverse layer transforms the DTs from analysis tools accessed by specialists into immersive environments where diverse stakeholders directly experience urban systems, collaborate in real-time despite physical distribution, and influence system behavior through intuitive interaction [

46]. The metaverse layer represents the most distinctive element of our MEDIGATE framework compared to current practice, enabling capabilities that conventional interfaces fundamentally cannot support.

Immersive interfaces (VR, AR, MR, XR) create a spatial understanding of complex urban systems that 2D dashboards cannot convey. When urban planners explore a proposed development within a virtual twin of the neighborhood, they apprehend relationships between buildings, infrastructure, and public spaces through the same perceptual mechanisms humans use to understand physical environments. The visual impact of a new high-rise building becomes immediately apparent through direct observation from multiple vantage points rather than requiring mental reconstruction from elevations and perspectives. The acoustic environment created by traffic patterns emerges through spatial audio rendering that allows planners to experience how sound propagates through the urban landscape. Pedestrian circulation patterns manifest through animated flows that reveal bottlenecks and safety concerns more effectively than density maps. Wind patterns affected by building geometries become tangible through visualization techniques including particle systems and flow fields that make invisible aerodynamic effects visible and comprehensible [

47].

The metaverse layer facilitates collaborative decision-making by allowing distributed stakeholders to inhabit the same virtual environment simultaneously. Emergency responders coordinating disaster response from different physical locations share a common operational picture where they can observe unfolding events, discuss response strategies, assign tasks, and monitor execution without the coordination challenges that voice-only communication creates. Transportation planners from multiple agencies collaborate on regional mobility improvements by directly experiencing how proposed changes to roads, transit, and bicycle infrastructure affect travel patterns throughout the network. Community members participate in urban planning processes by experiencing proposed changes to their neighborhoods alongside professional planners and elected officials, creating a shared understanding that verbal descriptions and architectural renderings cannot achieve [

12].

Avatars provide digital representations of users within virtual environments that support identity and social presence. Users customize avatars to reflect their appearance, professional role, or creative expression, establishing identity in the virtual space. Avatar behaviors, including gaze direction, gestures, and proximity, communicate nonverbal information that enriches collaboration beyond what audio and text can convey. Spatial audio renders voices to appear to originate from avatar locations, creating natural conversation dynamics where multiple participants can hold separate discussions without the confusion that typically accompanies large video conferences. Pointing gestures allow users to direct attention to specific features within the environment more effectively than verbal descriptions. These social affordances make virtual collaboration feel more natural and effective than conventional remote communication technologies [

48].

The metaverse layer enables

scenario exploration at scales and speeds impossible in physical environments. Urban planners experience years of neighborhood development within minutes by accelerating temporal simulation, observing how alternative zoning decisions shape community character over decades. Citizens understand long-term implications of policy choices by experiencing simulated future states rather than interpreting statistical projections. Transportation authorities evaluate emergency evacuation procedures by simulating thousands of residents responding to various disaster scenarios, identifying bottlenecks and optimization opportunities through observation rather than abstract analysis. Building designers explore how alternative layouts affect occupant experience by inhabiting virtual representations at full scale before construction commits to particular configurations. The temporal and spatial flexibility of metaverse DTs transforms planning from a process of analyzing static alternatives into an experiential exploration of dynamic possibilities [

11].

The metaverse layer creates possibilities for participatory governance that extend beyond consultation to active collaboration. Rather than soliciting citizen input through surveys or public meetings where verbal descriptions and two-dimensional visualizations constrain understanding, cities invite community members to experience proposed changes, experiment with alternatives, and express preferences through direct interaction with virtual environments. A neighborhood considering traffic calming measures explores various street configurations, experiencing how different designs affect vehicle speeds, pedestrian safety, parking availability, and aesthetic character. Residents vote on alternatives after this experiential exploration rather than based on abstract descriptions, leading to decisions better aligned with community values and more legitimate because participants feel genuinely informed. Public agencies use metaverse platforms for ongoing engagement rather than occasional consultations, building relationships with communities and enabling continuous dialogue about urban priorities and performance [

49].

Accessibility represents a critical design consideration for the metaverse layer. If immersive experiences require expensive virtual reality headsets, specialized hardware, and technical sophistication, this approach would exacerbate existing inequities by giving wealthy, educated citizens greater influence over urban systems while excluding vulnerable populations. The metaverse layer in our framework supports progressive enhancement across diverse access technologies. Users with virtual reality systems experience fully immersive 3D environments with six-degree-of-freedom tracking and spatial audio. Users with standard computers access similar environments through conventional monitors, keyboards, and mice, sacrificing some immersion but maintaining functional access. Users with smartphones and tablets participate through mobile applications optimized for smaller screens and touch interfaces. Users with limited bandwidth access lightweight versions that reduce graphical fidelity while preserving essential functionality. This multi-modal approach ensures that immersive urban platforms remain accessible to diverse populations rather than creating new digital divides [

50].

The metaverse layer incorporates natural language interfaces that allow users to query system states, request explanations, and issue commands through conversational interaction rather than requiring technical query languages.

Large language models (LLM) process natural language inputs, translate them into formal queries against DT databases, execute those queries, and formulate responses in natural language that users can understand, regardless of their technical background. For example, a community member asks how a proposed development would affect traffic in their neighborhood, and the system responds with both quantitative predictions and qualitative descriptions expressed in accessible language. An emergency manager requests that the system identify evacuation routes least likely to become congested, and the system simulates alternatives and recommends optimal paths with explanations of its reasoning. This natural interaction reduces barriers to participation and enables non-technical stakeholders to engage meaningfully with complex urban systems [

51].

The design of the metaverse layer prioritizes several architectural principles of optimization, interoperability, and security. Performance optimization ensures that virtual environments render smoothly even when representing large urban areas with millions of objects, using level-of-detail techniques, occlusion culling, and progressive loading to maintain responsiveness. Persistence mechanisms maintain the state of virtual environments across sessions, allowing users to return to previous work and enabling asynchronous collaboration where participants contribute at different times. Interoperability standards allow virtual environments created with different platforms and tools to share data and users, preventing fragmentation that would undermine the goal of creating shared urban platforms. Security controls protect against malicious users who might vandalize virtual environments or harass other participants, implementing moderation tools and access controls while preserving appropriate openness.

3.4. Action-Taking Layer: Automated Response and Closed-Loop Learning

The action-taking layer completes the architecture by executing interventions in the physical environment based on insights from DTs and decisions made through metaverse collaboration. This layer transforms the MEDIGATE framework from a sophisticated planning and analysis system into a genuinely proactive urban management platform that anticipates challenges and responds automatically with minimal human intervention except for high-stakes decisions requiring ethical judgment or political accountability.

Automated responses to routine conditions demonstrate the value of closed-loop systems that sense, analyze, decide, and act without delay. Traffic management systems adjust signal timing continuously based on real-time flow patterns predicted by transportation DTs, optimizing network throughput and minimizing delays without requiring human traffic engineers to constantly monitor conditions and make manual adjustments. Building management systems modulate energy consumption in response to grid conditions communicated by energy DTs, reducing demand during stress periods and increasing consumption when renewable generation exceeds demand, flattening load curves and enabling greater renewable integration. Water management systems operate valves and pumps to maintain optimal pressures throughout distribution networks, preventing both low pressure that compromises fire suppression capability and high pressure that stresses pipes and increases leakage. These automated responses occur within seconds of triggering conditions, preventing problems that would escalate if systems waited for human intervention [

52].

The action-taking layer also supports

human-authorized interventions for non-routine situations where an automated response would be inappropriate because ethical considerations, political sensitivity, or uncertainty about optimal actions require human judgment. When environmental DTs predict that air quality will deteriorate to unhealthy levels, the system generates recommendations for actions, including traffic restrictions, industrial emission controls, and public health advisories. Human decision-makers review these recommendations, consider broader context, including economic impacts and enforcement feasibility, and authorize selected interventions. The action-taking layer then executes the authorized actions by communicating with relevant control systems, implements the traffic restrictions through variable message signs and enforcement systems, notifies industries of temporary operating limits, and disseminates public health advisories through multiple communication channels. Utilizing a human-in-the-loop approach preserves appropriate oversight for consequential decisions while automating the execution once decisions are made [

53].

Robotic systems extend the action-taking layer’s capabilities beyond digital control of infrastructure systems to physical interventions in the urban environment. Inspection drones equipped with cameras and sensors examine bridges, electrical transmission towers, and building facades to detect structural damage, corrosion, and other maintenance needs, generating work orders automatically when problems exceed defined thresholds. Maintenance robots perform routine tasks, including street cleaning, graffiti removal, and minor repairs, without requiring human labor for repetitive activities. Delivery robots transport goods through pedestrian spaces and buildings, coordinating with transportation DTs to optimize routes and avoid congestion. Autonomous vehicles provide flexible transportation services that respond dynamically to demand patterns predicted by DTs, improving mobility access without requiring fixed route schedules. These robotic systems operate under the supervision of DTs that coordinate their activities, assign tasks, monitor performance, and intervene when anomalies indicate potential problems [

54].

The action-taking layer implements

closed-loop learning by monitoring outcomes of interventions, comparing results against predictions from DT simulations, updating models to improve future predictions, and refining intervention strategies based on observed effectiveness. When a traffic management system implements signal timing changes to reduce congestion, it observes actual traffic flows after the intervention and compares them to the flows predicted by the transportation DT. If actual outcomes differ systematically from predictions, ML algorithms adjust model parameters to improve future accuracy. If the intervention proves less effective than simulated, the system explores alternative strategies through simulation before implementing them physically. This continuous learning enables urban systems to become increasingly sophisticated in anticipating challenges and optimizing responses over time [

55].

The design of the action-taking layer prioritizes several architectural principles of safety, auditability, and functionality. Safety mechanisms prevent automated actions that could endanger public welfare through multiple layers of protection, including sanity checks that reject commands outside physically plausible ranges, rate limits that prevent rapid sequences of changes that might destabilize systems, and emergency stop capabilities that allow human operators to halt automated actions immediately when situations develop unexpectedly. Auditability requirements maintain detailed logs of all actions, the analyses that motivated them, and the outcomes they produced, enabling after-action review and accountability for system behavior. Reversibility considerations ensure that automated interventions can be undone if they prove ineffective or create unintended consequences, without requiring human approval. Graceful degradation allows systems to continue operating with reduced functionality when components fail rather than failing catastrophically, maintaining essential services even during disruptions.

3.5. Emergent Capabilities Through Layer Integration

The power of this architectural framework emerges from the integration of layers rather than from any individual component. The physical layer enables real-time awareness of urban conditions and provides actuation mechanisms for intervention, but without higher layers it merely generates data without producing insight or action. The DTs layer creates predictive models and simulations that reveal patterns and forecast futures, but without the physical layer, it lacks current information, and without the action-taking layer, its insights remain theoretical. The metaverse layer facilitates human understanding and collaboration, but without DTs to provide content, it would be an empty environment, and without action-taking capabilities, decisions made within it would lack consequence. The action-taking layer executes interventions, but without DT guidance, it would lack the intelligence to determine appropriate actions. Without the metaverse layer, it would exclude human judgment from consequential decisions.

Together, these layers create a system that senses conditions continuously through distributed physical infrastructure, synthesizes insights by fusing information across urban domains through integrated DTs, engages stakeholders through immersive environments that make complex systems comprehensible and enable collaboration, responds proactively through automated actions that prevent problems rather than merely reacting to them, and learns continuously from outcomes to improve future performance. The DT integration transforms urban management from an activity of monitoring problems and reacting to crises into a process of anticipating challenges, engaging communities, and shaping desirable futures.

The architectural MEDIGATE framework we have presented in

Figure 2. provides the intellectual foundation for the practical implementation pathway discussed in the following section. Before examining that pathway, it is worth noting that this architecture does not require simultaneous implementation of all components across all urban systems. Cities can deploy individual layers incrementally, gaining value at each stage while building toward comprehensive integration. The microverse concept introduced in the next section provides a structured approach for this incremental deployment that generates immediate benefits while establishing patterns for broader adoption.

4. From Microverses to a Metaverse: A Practical Implementation Pathway

The architectural framework presented in the previous section articulates a comprehensive vision for proactive smart cities enabled by the integration of DTs, metaverse platforms, edge computing, AI, and automated actuation. However, implementing such a framework simultaneously across all urban systems at the metropolitan scale would present prohibitive complexity, enormous cost, and unacceptable risk. Cities require an approach that generates tangible value at each implementation stage while progressively building toward comprehensive integration.

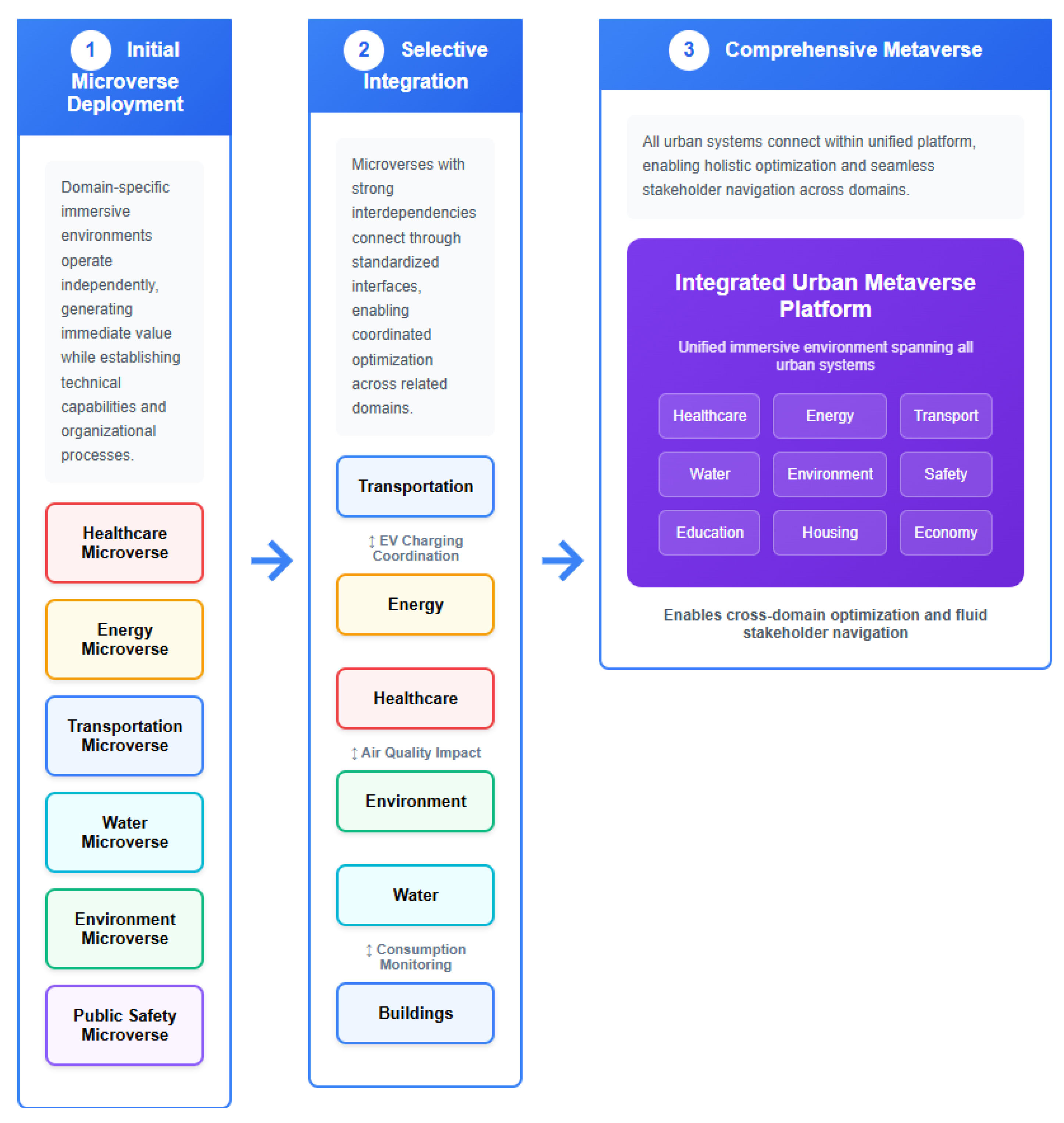

Section 4 introduces the

microverse [

56] as a practical pathway that enables incremental deployment through domain-specific immersive environments that initially operate with substantial autonomy while sharing architectural principles that facilitate eventual integration into a unified urban metaverse platform.

4.1. The Challenge of Comprehensive Urban-Scale Implementation

Attempting to deploy metaverse-enabled DTs across an entire metropolitan area simultaneously would encounter numerous obstacles that make such an approach impractical regardless of available resources. The technical complexity of integrating hundreds of thousands of sensors, thousands of buildings, extensive transportation and utility networks, and millions of citizens across multiple domains simultaneously exceeds the capacity of any implementation team to design, test, and deploy reliably. The organizational coordination required to align transportation agencies, utility providers, public health departments, emergency services, building operators, and other stakeholders around common platforms and data models would demand years of negotiation that delays beneficial deployment. The financial investment necessary to acquire hardware, develop software, train personnel, and maintain operations across all urban systems simultaneously would require budget allocations that few cities could justify, particularly when benefits remain uncertain until substantial implementation progress occurs. The operational risk of deploying untested systems at scale across critical infrastructure that millions depend upon daily creates unacceptable exposure to failures that could cascade through interconnected systems [

57].

Historical experience with large-scale information technology projects reinforces the wisdom of incremental approaches over comprehensive deployments. Enterprise resource planning implementations that attempted to replace all legacy systems simultaneously have frequently experienced catastrophic failures that disrupted operations for months or years while costing billions of dollars beyond initial estimates [

58]. Smart city initiatives that pursued ambitious visions without staged implementation have similarly struggled, with high-profile examples including Sidewalk Labs’ proposed development in Toronto that collapsed after years of planning when complexity and controversy overwhelmed the project’s capacity to deliver incremental value [

59]. In contrast, successful digital transformations typically proceed through pilot projects that demonstrate value in constrained domains before expanding to broader organizational or geographic scope.

The microverse concept addresses these challenges by decomposing the comprehensive urban metaverse vision into domain-specific implementations that can proceed independently while maintaining compatibility for eventual integration. Rather than attempting simultaneous deployment across transportation, energy, water, healthcare, public safety, and environmental systems, cities can launch focused initiatives in individual domains where challenges are most acute, stakeholder support is strongest, and technology is most mature. These domain-specific microverses deliver immediate operational improvements and stakeholder benefits that justify continued investment while establishing organizational capabilities, technical infrastructure, and governance frameworks that enable subsequent expansion.

4.2. Domain-Specific Microverse Implementations

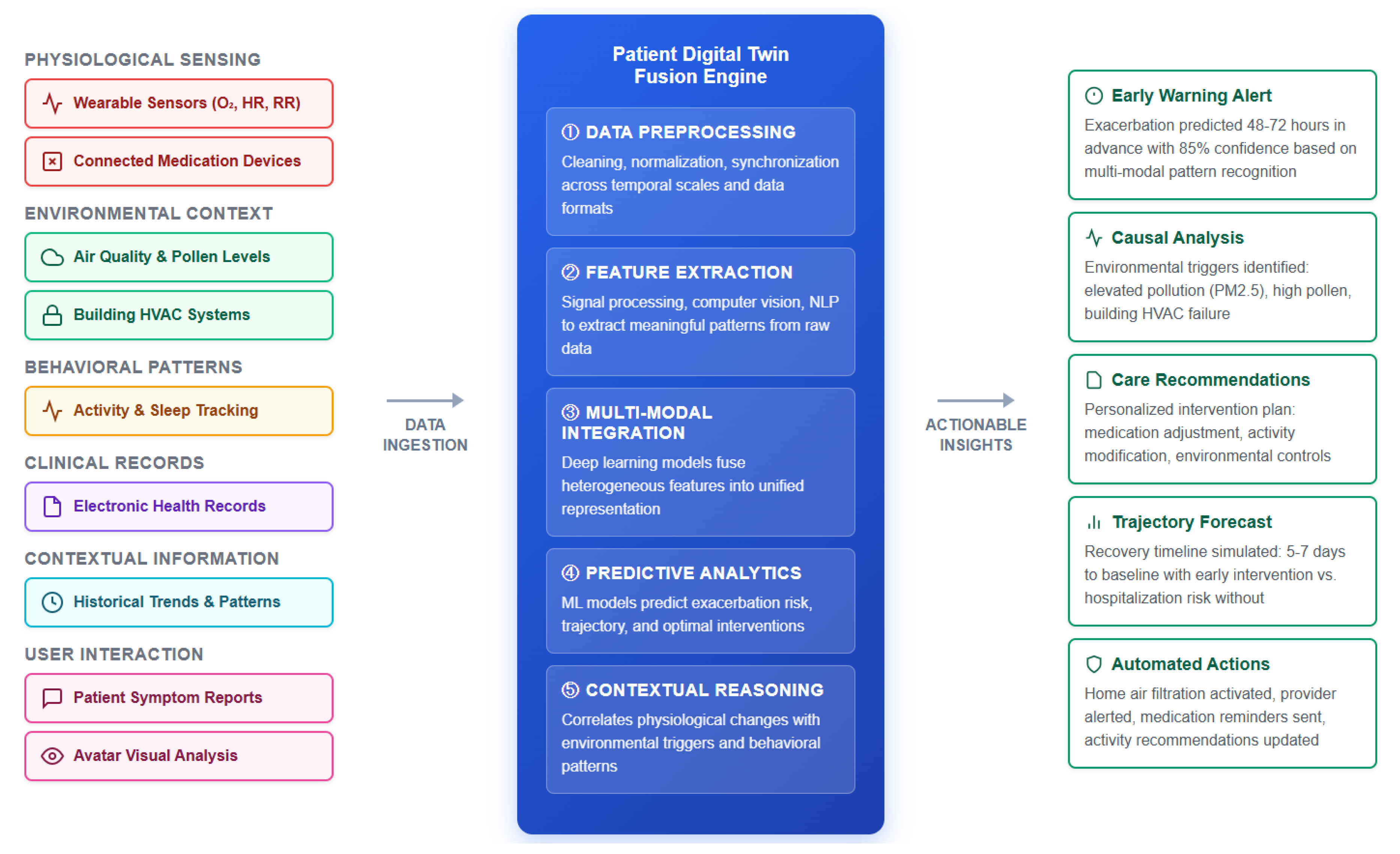

A healthcare microverse encompasses hospitals, clinics, community health centers, rehabilitation facilities, and individual patient DTs within an immersive environment that integrates clinical care delivery, public health monitoring, and wellness management. Healthcare providers use this platform to coordinate care across multiple facilities and specialties, accessing comprehensive patient DTs that synthesize electronic health records, wearable sensor data, genetic information, and environmental exposure histories. Patients engage with their own DTs through accessible interfaces that visualize health status, explain treatment options through interactive 3D anatomical models, and simulate expected outcomes of alternative therapeutic approaches. Public health officials monitor population health patterns within the microverse, identifying disease outbreaks, evaluating intervention strategies, and coordinating response across clinical and community settings [

60].

The healthcare microverse connects with other urban systems through well-defined interfaces even when comprehensive metaverse integration has not yet occurred. Environmental monitoring systems provide air quality, pollen levels, and weather conditions that affect respiratory and cardiovascular health. Building management systems report indoor environmental quality that influences occupant wellness. Transportation systems facilitate non-emergency medical transport and emergency ambulance routing. However, these connections operate through standardized application programming interfaces rather than requiring full integration of all systems into a common platform. A layered approach allows the healthcare microverse to generate substantial value through improved care coordination and patient engagement while maintaining flexibility regarding the pace and scope of broader urban system integration.

An

energy microverse integrates electricity generation, transmission, distribution, and consumption systems with building management, electric vehicle charging, distributed renewable energy, and energy storage within an immersive platform that optimizes grid operations and enables active consumer participation. Utility operators use this environment to visualize grid states, predict demand patterns, identify potential disturbances, and coordinate response across generation assets and network components. Building managers participate in demand response programs by observing how their consumption patterns affect grid conditions and adjusting operations during stress periods to earn financial incentives. Electric vehicle owners coordinate charging schedules with grid conditions and renewable generation availability to minimize costs and environmental impacts. Renewable energy project developers evaluate potential installation sites by simulating generation patterns and grid integration challenges within the DT environment before committing to physical deployment [

61].

The energy microverse demonstrates particular value from integration with building systems because electricity consumption patterns correlate strongly with occupancy, weather, and building operational characteristics that building management systems already monitor. Rather than requiring utility operators to estimate consumption through historical patterns and weather correlations, the energy microverse directly accesses building DTs to obtain real-time occupancy forecasts and equipment status that improve demand predictions. Conversely, building management systems use grid condition information from the energy microverse to optimize consumption timing, shifting flexible loads, including heating, cooling, and water heating, to periods when electricity costs less and renewable generation availability is higher. This bidirectional integration delivers benefits that neither system could achieve operating independently, while demonstrating patterns that extend to integration with other domains.

A

transportation and mobility microverse encompasses roadways, public transit, parking, bicycle infrastructure, pedestrian facilities, and shared mobility services within an immersive environment that optimizes network operations and improves user experience. Transportation agencies can use this platform to monitor traffic conditions, predict congestion, coordinate signal timing, manage incidents, and evaluate infrastructure improvements through simulation before physical implementation. Transit operators coordinate bus and rail services to minimize wait times and overcrowding while maintaining schedule reliability. Shared mobility providers, including ride-hailing services, car-sharing, and scooter operators, integrate their fleets into the microverse to coordinate with public transit and reduce conflicts with other road users. Individual travelers access trip planning tools that synthesize information across all transportation modes to recommend optimal routes considering cost, time, comfort, and environmental impact [

62].

The transportation microverse benefits substantially from integration with other urban systems, even when those systems have not themselves implemented full microverse capabilities. Weather monitoring systems provide precipitation and visibility forecasts that affect travel speeds and safety. Event management systems communicate about concerts, sports events, and other activities that generate unusual travel demand. Emergency management systems coordinate road closures and detours during incidents. Public health systems identify accessibility needs for medical appointments and vaccination clinics that require transportation planning. These integrations demonstrate how microverses serve as focal points for information synthesis even when partner systems have not yet adopted immersive platforms, gradually building the network effects that justify broader microverse deployment across additional domains.

A

water management microverse integrates source watersheds, treatment facilities, distribution networks, wastewater collection, and treatment systems within an immersive environment that optimizes operations and protects public health. Utility operators can use this platform to monitor system performance, predict equipment failures, detect leaks and contamination, coordinate maintenance activities, and simulate the impacts of infrastructure investments. The microverse incorporates hydrological models that forecast water availability based on precipitation patterns, snowpack conditions, and climate projections, enabling long-term planning that ensures supply reliability despite growing demand and increasing variability. Water quality monitoring throughout the system detects contamination events within minutes rather than hours or days, enabling rapid response that protects public health. Integration with building management systems identifies abnormal consumption patterns that might indicate leaks or equipment malfunctions, enabling proactive maintenance that reduces water waste [

63].

Additional microverses can address public safety and emergency management, environmental monitoring and climate resilience, waste management and circular economy, education and workforce development, cultural facilities and civic engagement, or specific geographic districts within cities that face unique challenges requiring integrated management. The specific domains that cities prioritize for microverse implementation will reflect local circumstances including pressing challenges, available resources, stakeholder priorities, and organizational capabilities. The microverse architecture accommodates this diversity by defining common principles while allowing variation in specific implementations.

4.3. Evolution Through Three Implementation Stages

The microverse pathway to comprehensive urban metaverse platforms progresses through three evolutionary stages that reflect increasing integration maturity and expanding scope. Cities can advance through these stages at different paces in different domains according to local priorities and capabilities, with some microverses progressing rapidly while others develop more gradually.

Figure 3 illustrates the three-stage evolutionary pathway from independent microverses to comprehensive metaverse integration. Initial microverse deployment focuses on creating domain-specific immersive environments that demonstrate value and establish implementation patterns. During this stage, cities launch pilot microverses in one or two more domains where challenges are most acute and stakeholder support is strongest. A city experiencing chronic traffic congestion might prioritize the transportation microverse, while another facing public health disparities could emphasize the healthcare microverse. These initial implementations concentrate on delivering operational improvements within their domains rather than pursuing extensive integration with other urban systems. The transportation microverse optimizes the timing of the traffic signal and provides travelers with better information. The healthcare microverse improves care coordination and patient engagement. These domain-specific benefits justify the investment in immersive platforms and DT infrastructure while establishing technical capabilities, organizational processes, and governance frameworks that inform subsequent deployments.

Selective integration connects microverses where interdependencies are strongest and coordination delivers the greatest benefits. The transportation and energy microverses integrate to coordinate electric vehicle charging with grid conditions, reducing stress on electrical distribution networks during peak periods while enabling utilities to offer favorable rates that encourage off-peak charging. The healthcare and environmental microverses collaborate to investigate relationships between air quality and respiratory disease incidence, enabling public health officials to issue targeted advisories and recommend protective measures during pollution episodes. The water management and building microverses share consumption monitoring to detect leaks rapidly, reducing water losses and property damage. These selective integrations demonstrate the value of cross-domain coordination while maintaining manageable complexity by connecting pairs or small groups of microverses rather than attempting comprehensive integration simultaneously across all systems [

23].

Comprehensive metaverse integration ultimately creates a unified platform where all urban systems connect, enabling holistic optimization and allowing stakeholders to seamlessly navigate between domains while maintaining a coherent understanding. A resident experiencing respiratory symptoms accesses their healthcare DT, which automatically incorporates environmental monitoring data showing elevated pollution exposure, building system information indicating potential indoor air quality issues, and suggestions for modifying travel routes and activity timing to reduce further exposure. Emergency managers coordinating response to natural disasters simultaneously visualize impacts across transportation, energy, water, healthcare, and communication systems within an integrated environment that reveals cascading effects and optimization opportunities invisible when examining domains independently. Urban planners evaluating proposed developments assess impacts holistically by simulating effects on traffic patterns, energy demand, water consumption, air quality, public health, and community character within a unified DT that maintains consistency across domains.

An evolutionary approach enables cities to progress from current fragmented DT implementations toward comprehensive metaverse-enabled platforms through a series of incremental steps that generate value continuously rather than requiring massive upfront investment with delayed returns. Cities need not commit to the complete vision before beginning deployment, instead launching focused pilots that test concepts and build capabilities while preserving flexibility regarding how extensively and rapidly to proceed with subsequent stages.

4.4. Architectural Principles Enabling Integration

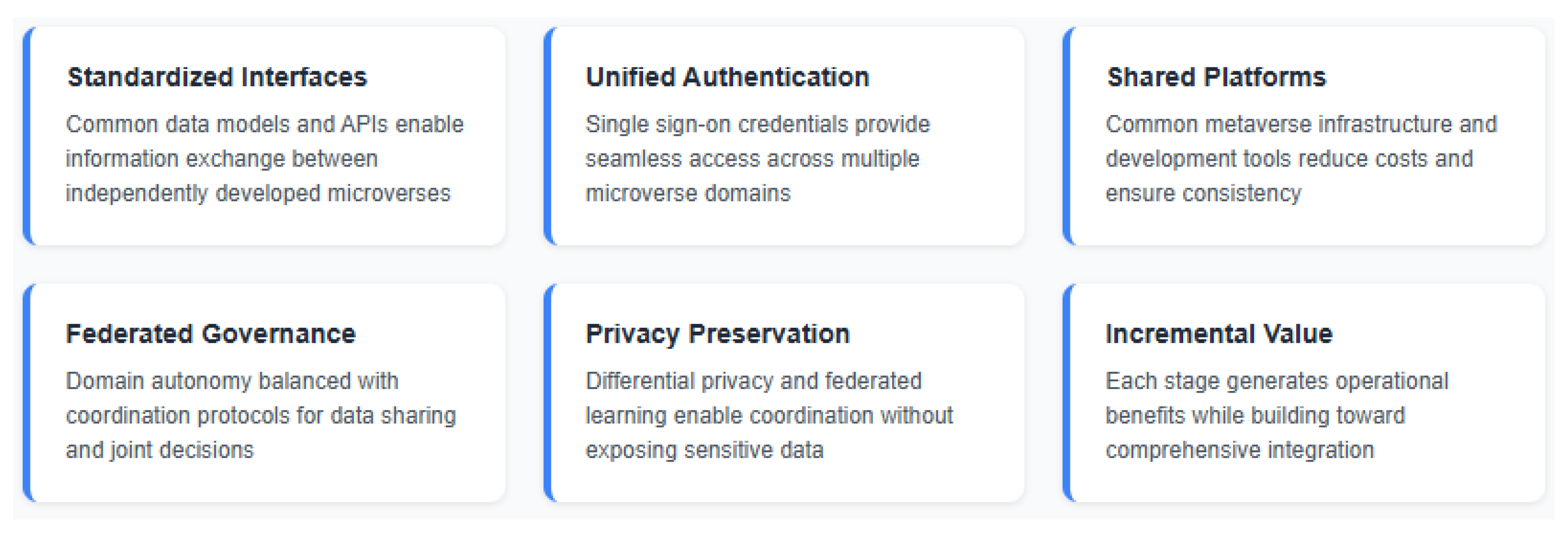

The value of the microverse approach depends critically on ensuring that domain-specific implementations can eventually integrate into comprehensive urban metaverse platforms rather than creating permanent silos that replicate the fragmentation of current systems. Several architectural principles guide microverse design to facilitate this eventual integration while preserving the autonomy necessary for independent deployment and operation.

Figure 4 illustrates the key architectural principles that enable the integration.

Standardized data models and

application programming interfaces allow different microverses to exchange information even when initially designed independently. The energy microverse exposes interfaces that allow other systems to query current grid conditions, forecast future states, and request simulations of how alternative consumption patterns would affect operations. The transportation microverse provides interfaces for obtaining travel time predictions, road closure information, and public transit schedules. The healthcare microverse shares population health statistics and disease surveillance data with appropriate privacy protections. These interfaces follow common conventions regarding authentication, data formats, error handling, and versioning that reduce integration costs and enable automated information exchange without requiring manual coordination for

incremental value [

64].

Common