Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

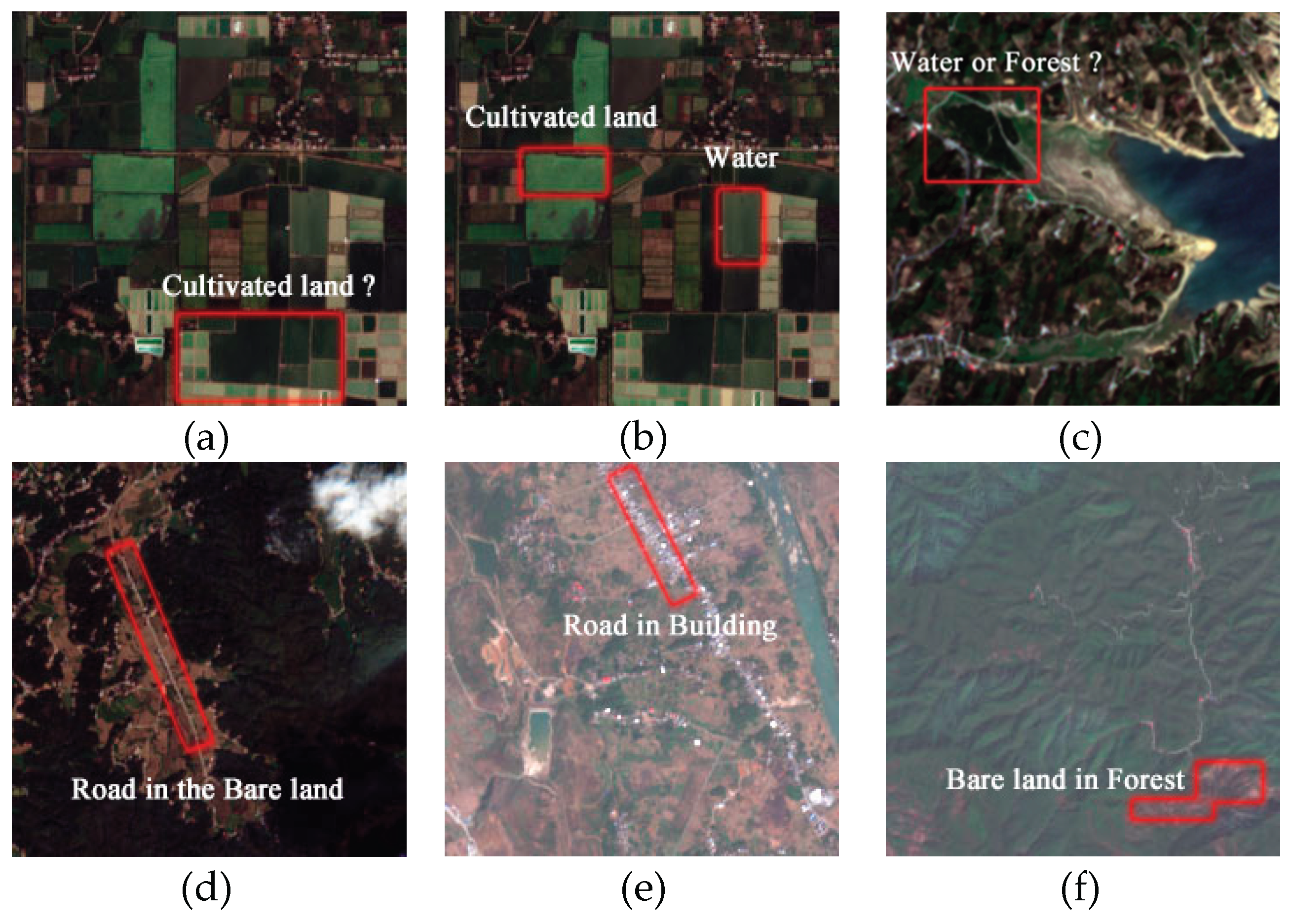

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

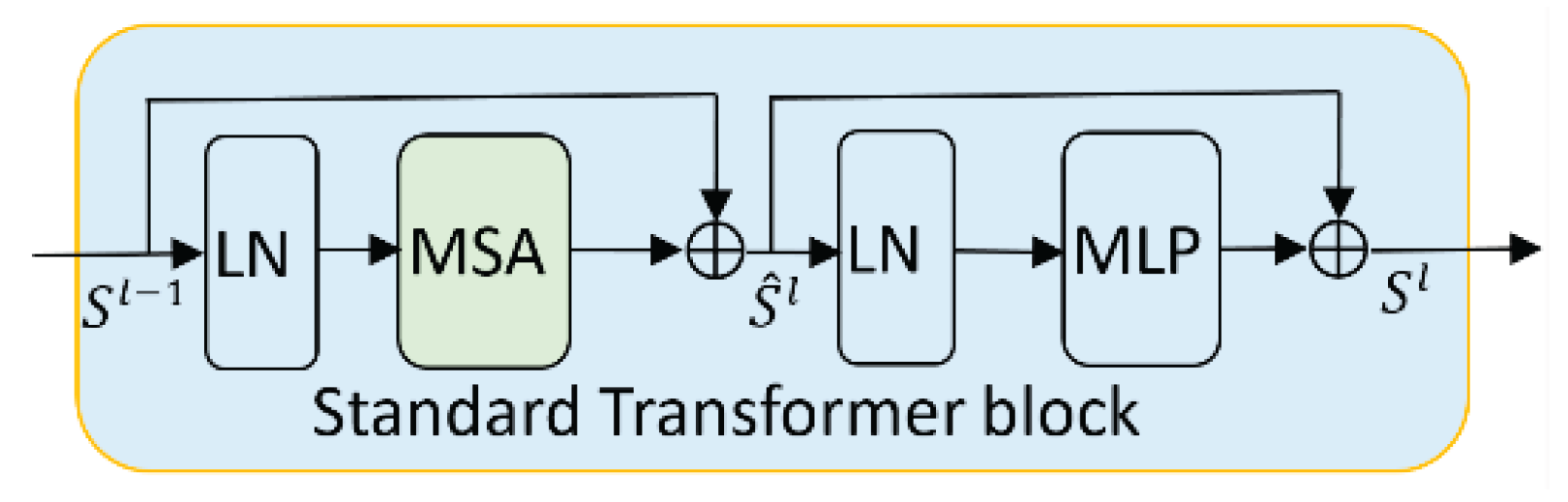

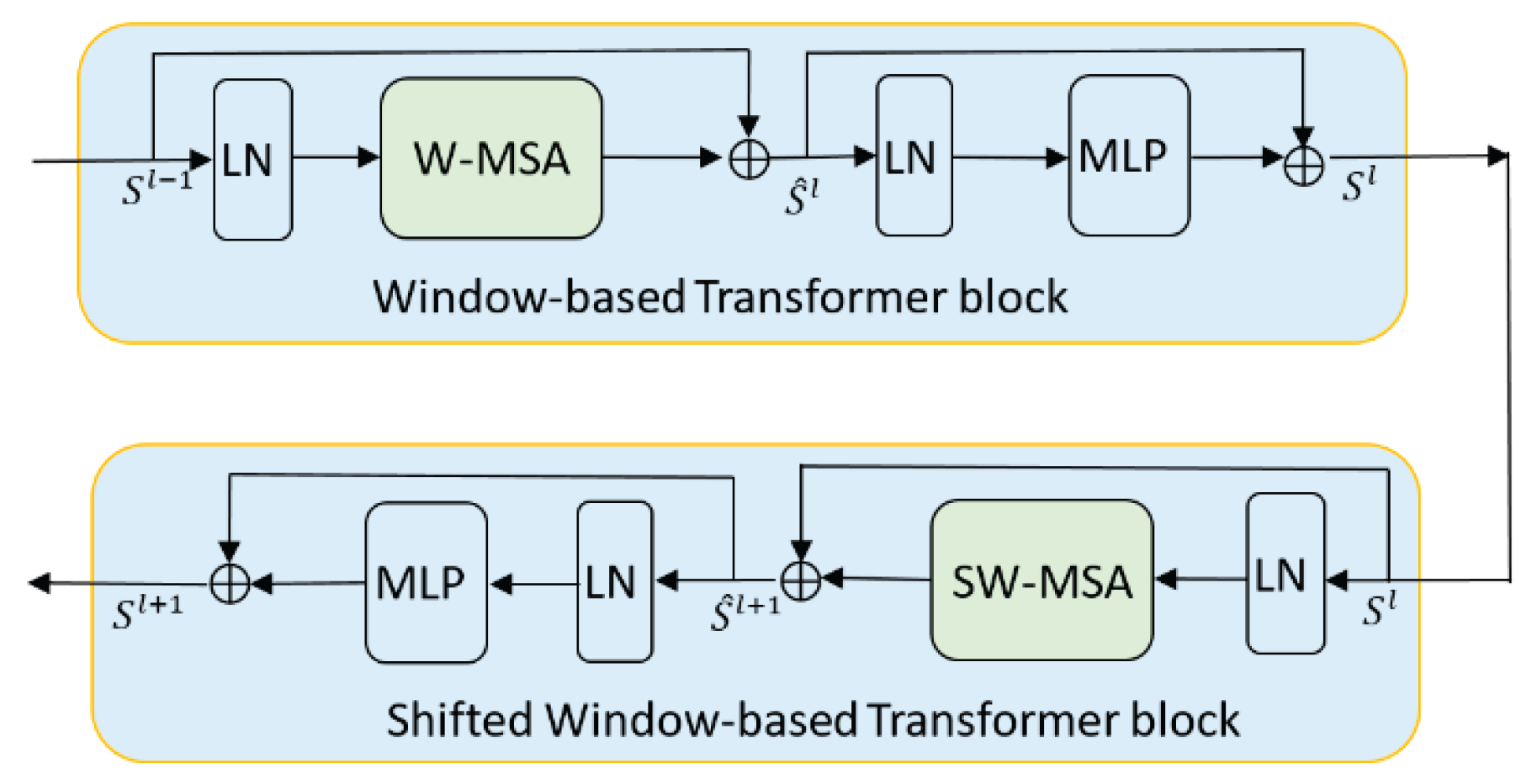

2.1. Vision Transformer

2.2. Vision GCN

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Materials

3.1.1. Forest Dataset

3.1.2. GID Dataset

3.2. Method

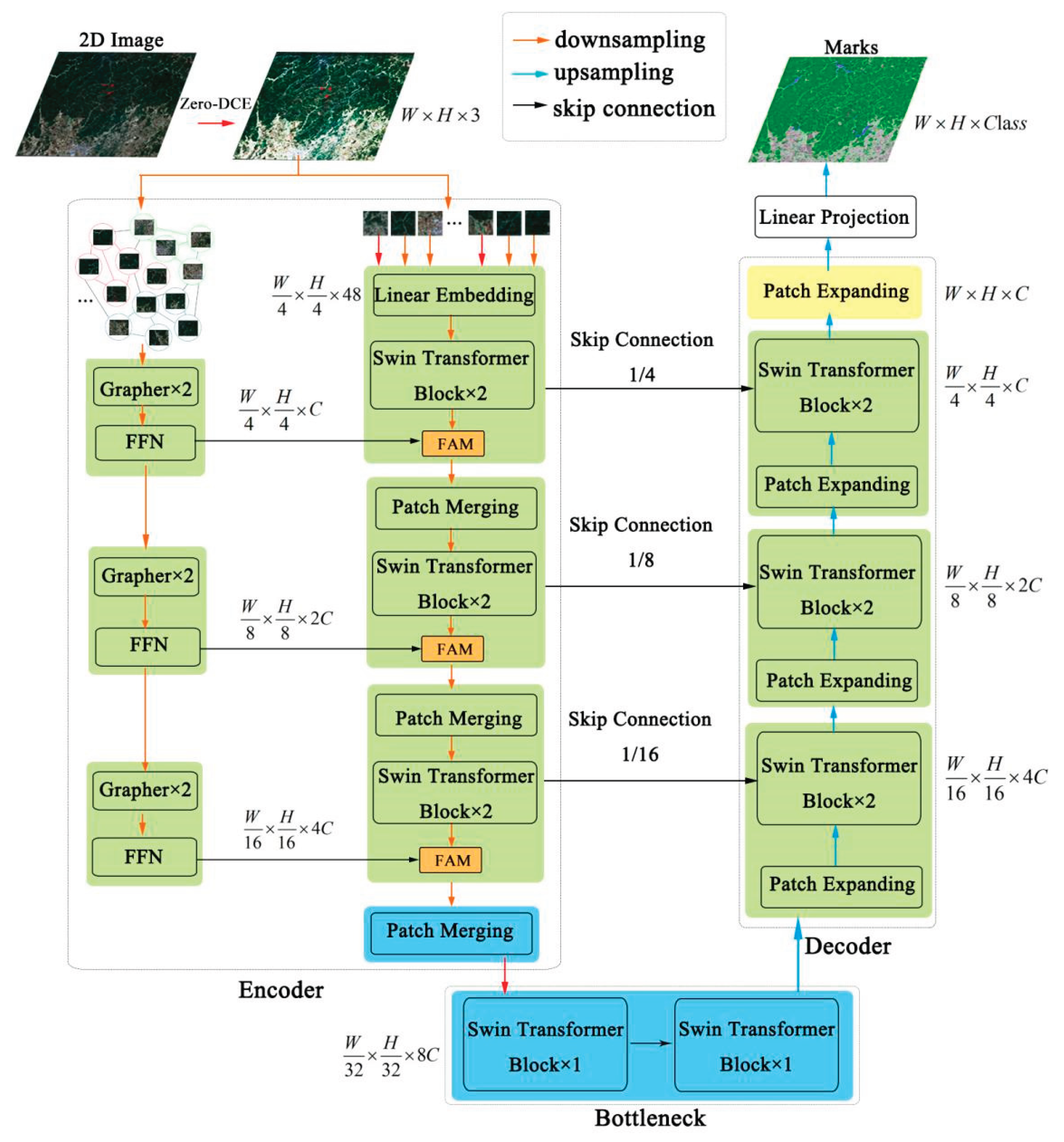

3.2.1. Network Structure

3.2.2. Swin Transformer Block

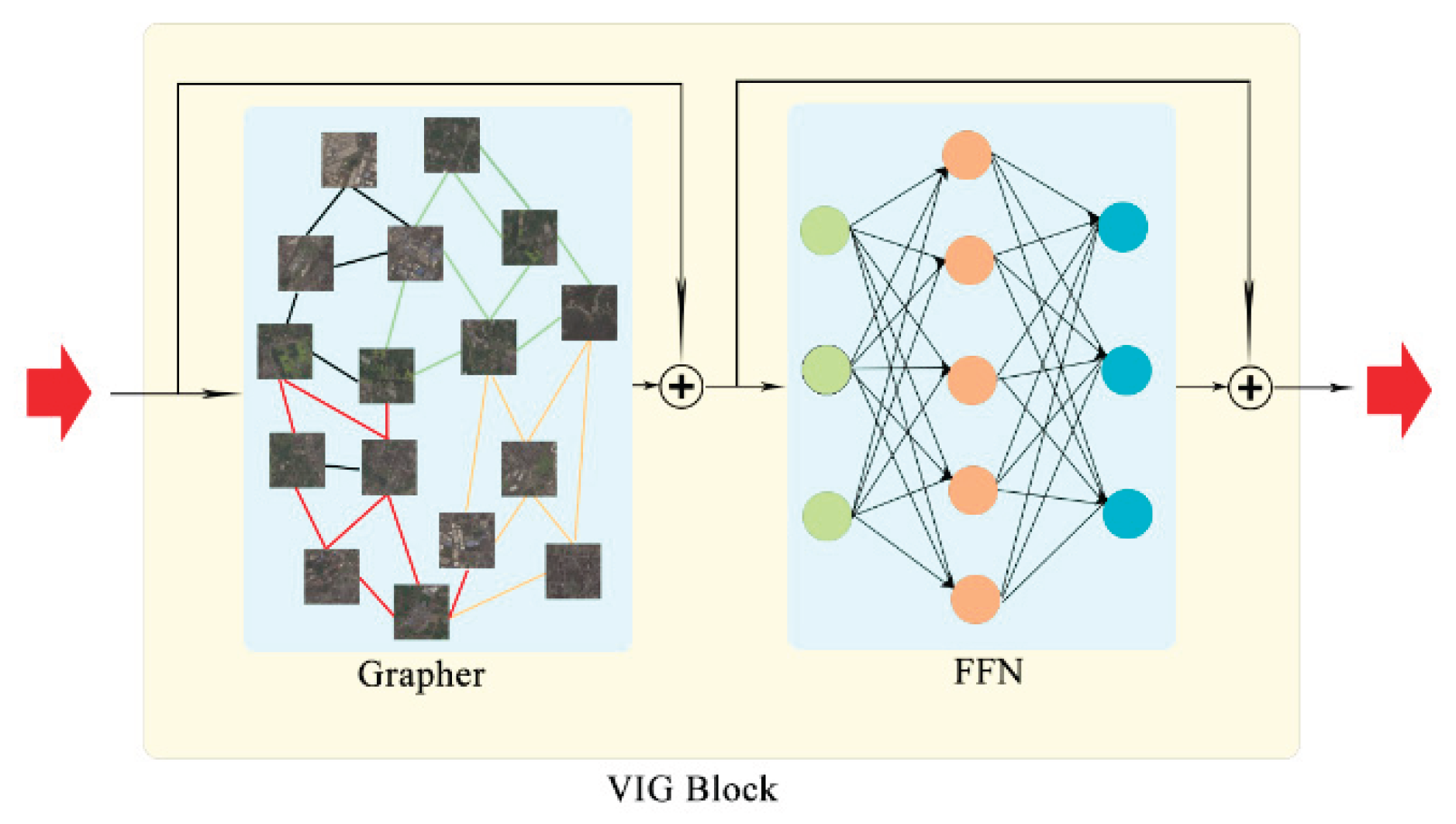

3.2.3. VIG Block

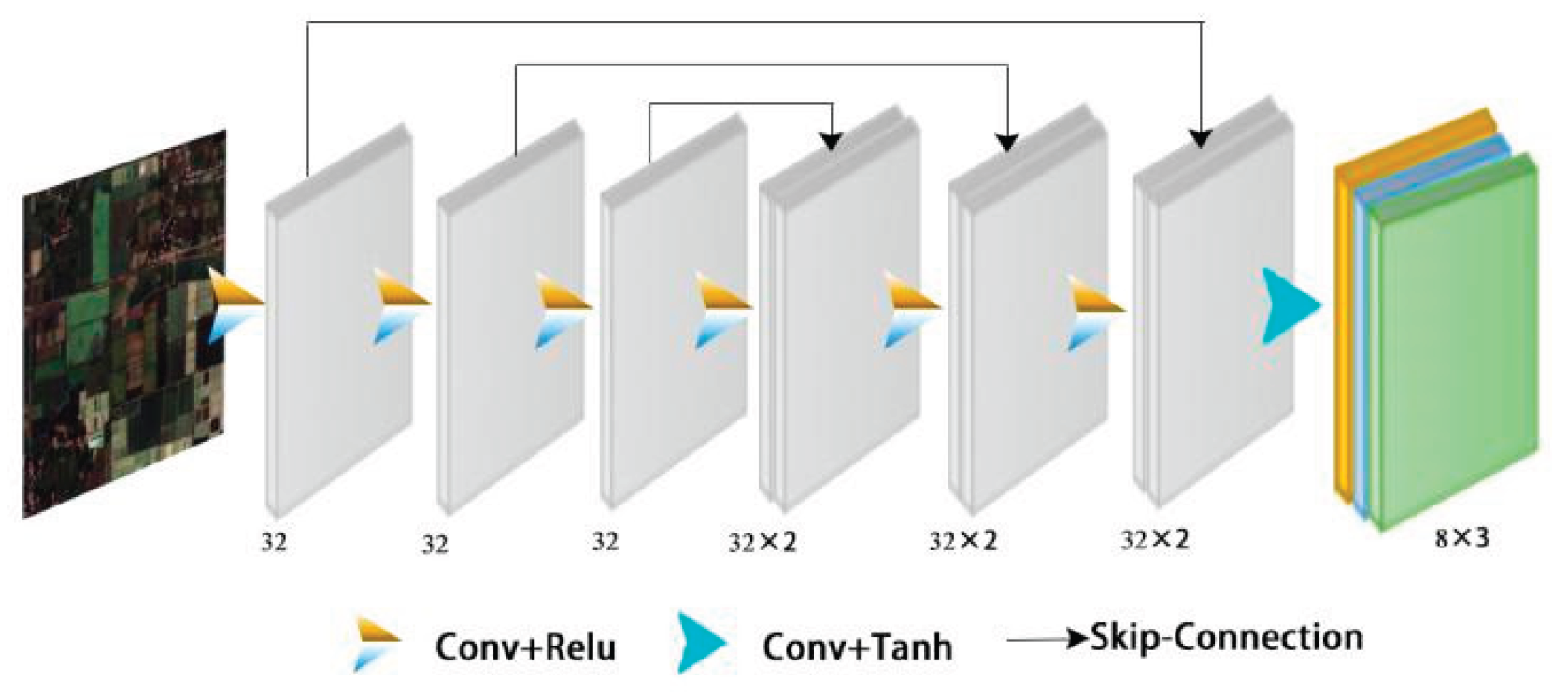

3.2.4. Zero-Dice Model

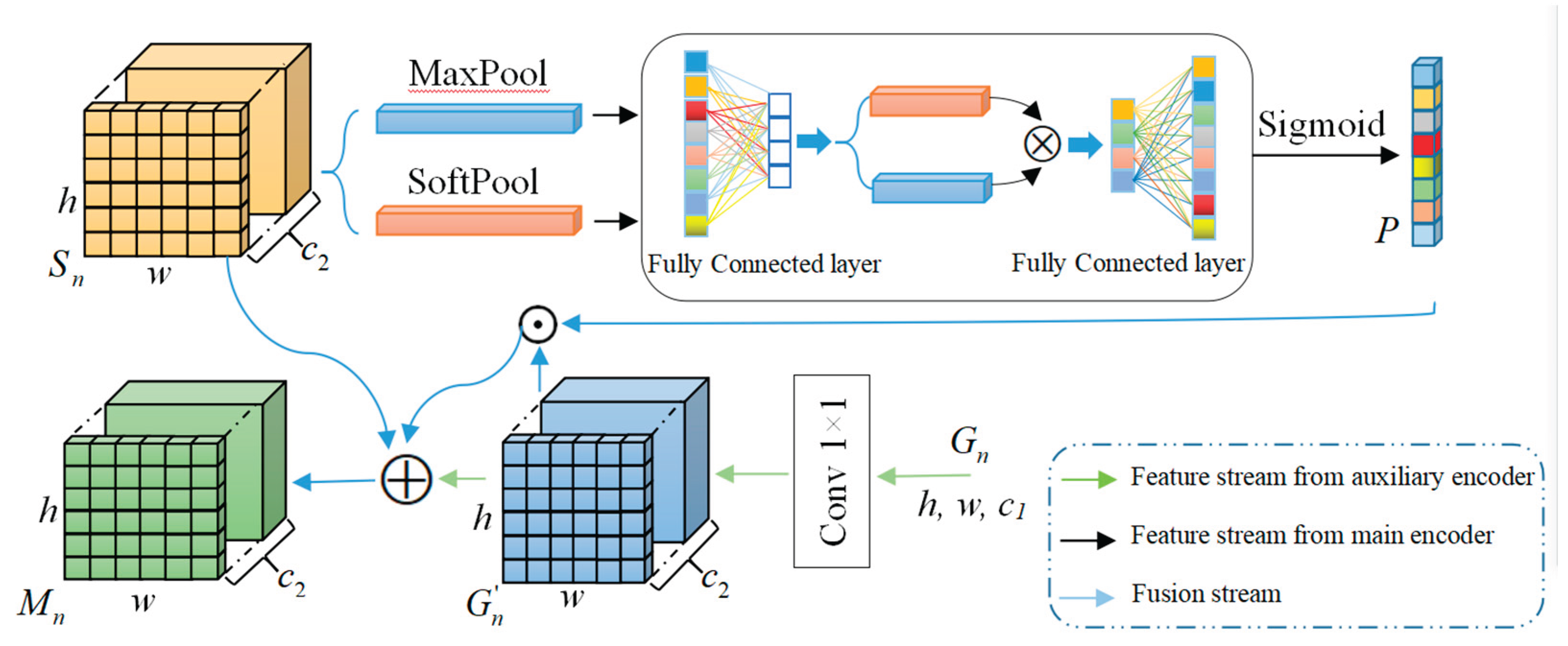

3.2.5. Feature Aggregation Model

4. Experiments

4.1. Implementation Details

4.1.1. Training Setting

4.1.2. Loss Function

4.1.3. Evaluation Index

4.1.4. Network Structure Parameter Settings

4.2. Ablation Study

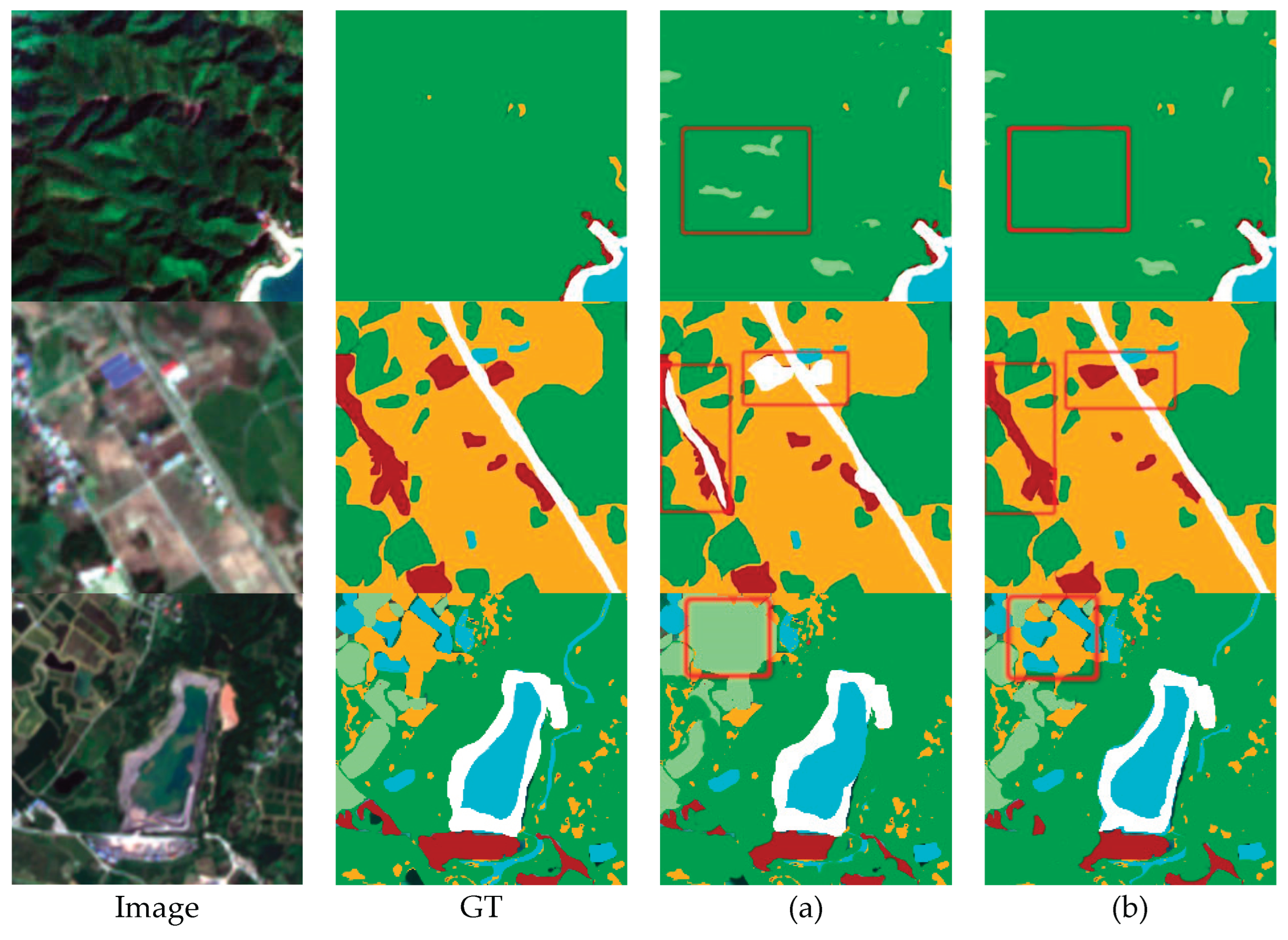

5. Results

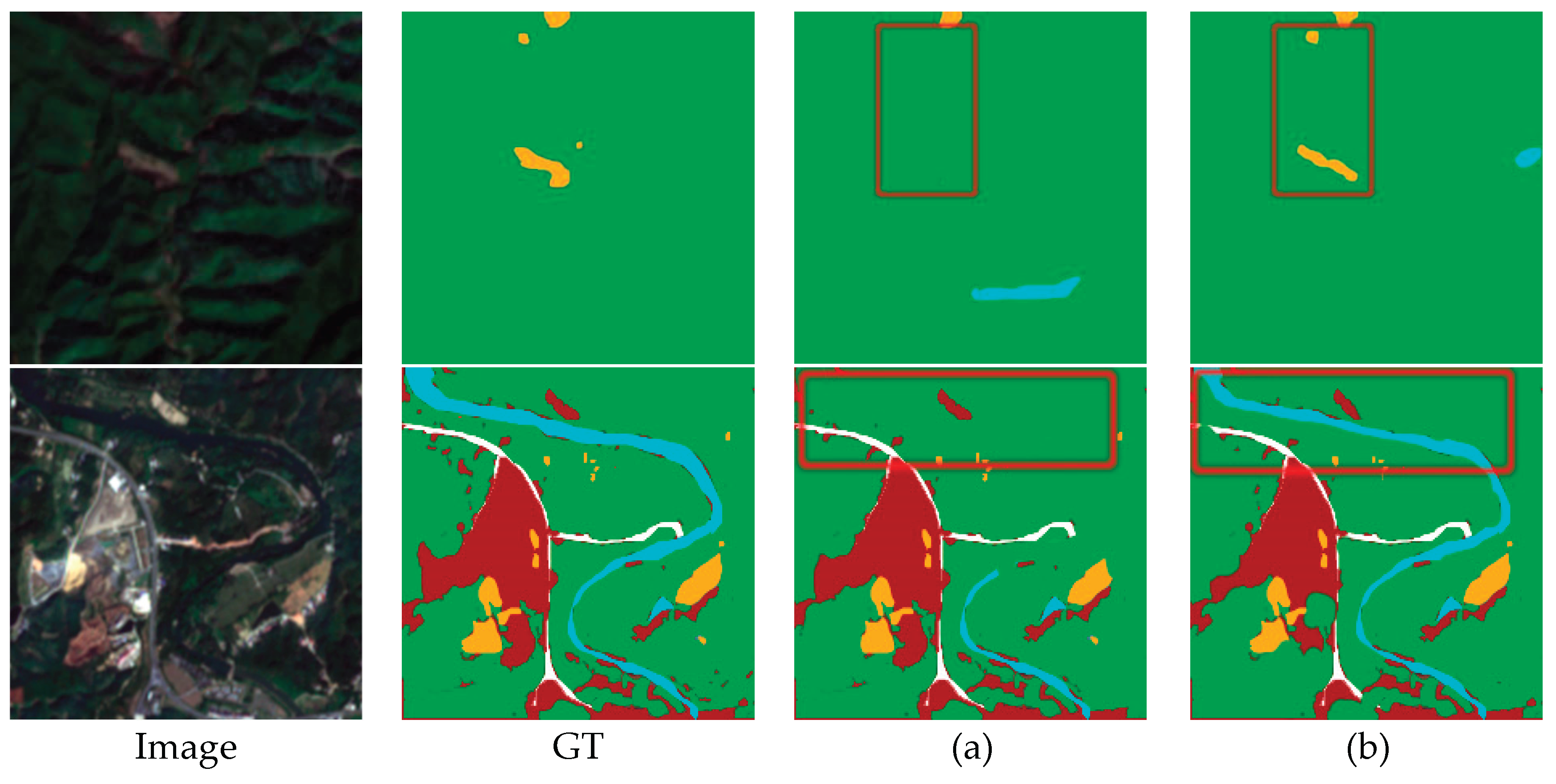

5.1. Effect of Dual Encoder Structure

5.2. Effect of Feature Aggregation Module

5.3. Effect of Zero-Dice Module

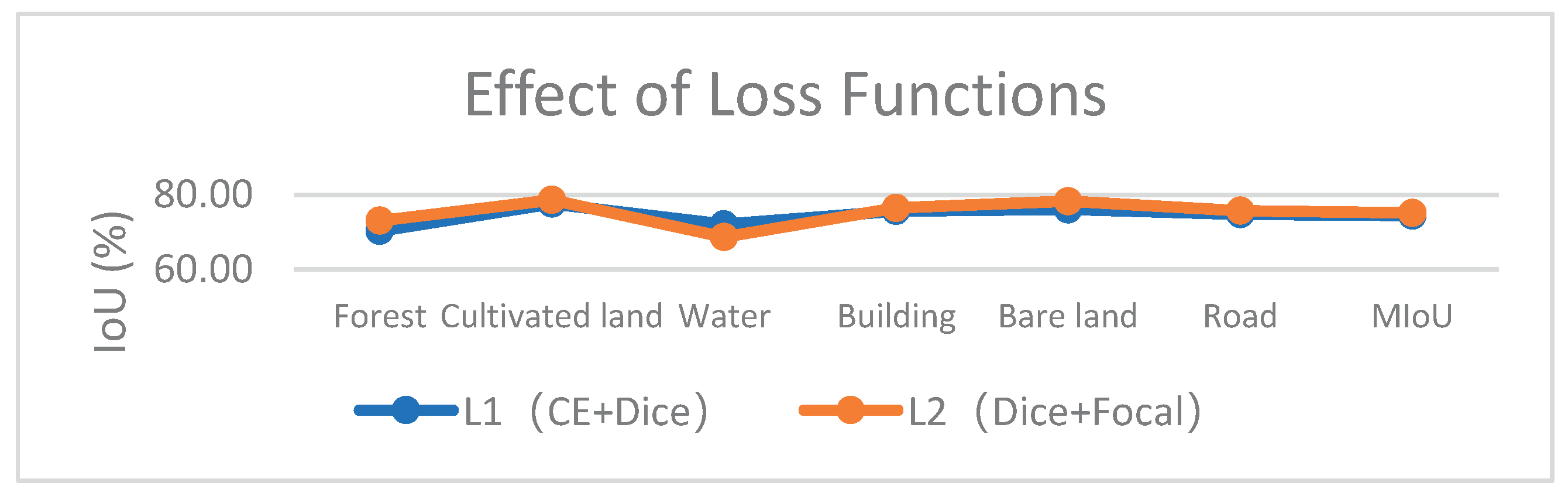

5.4. Effect of Loss Functions

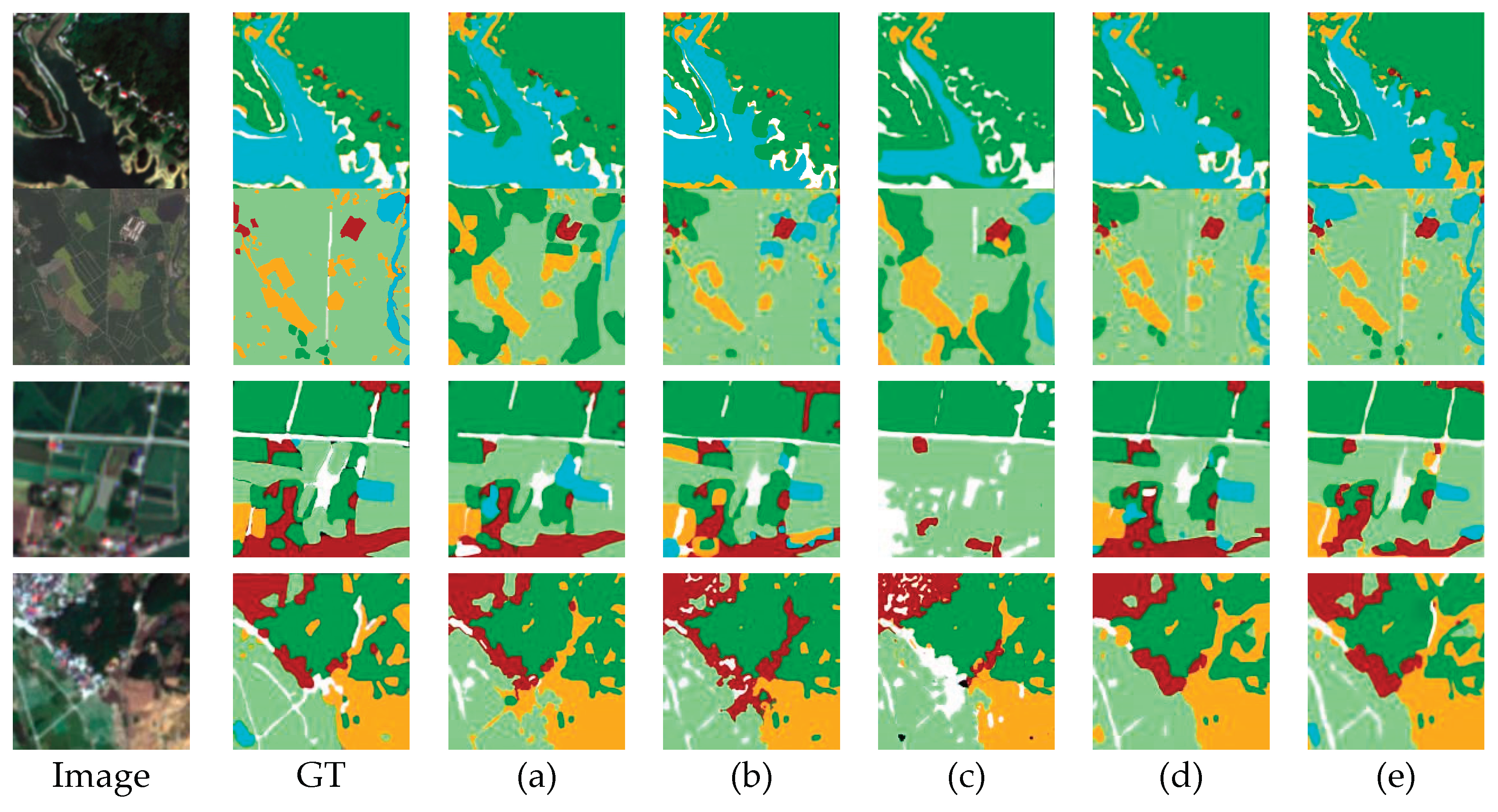

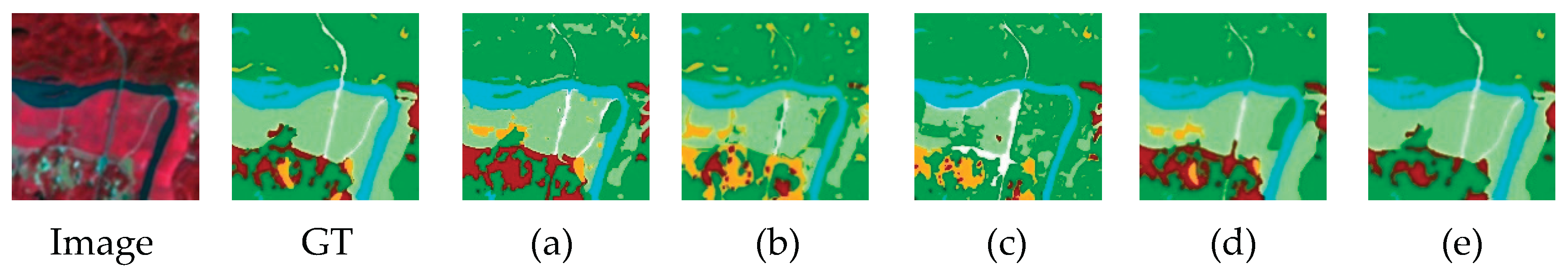

5.5. Comparison with Other Methods

5.5.1. Results on RGB Forest Dataset

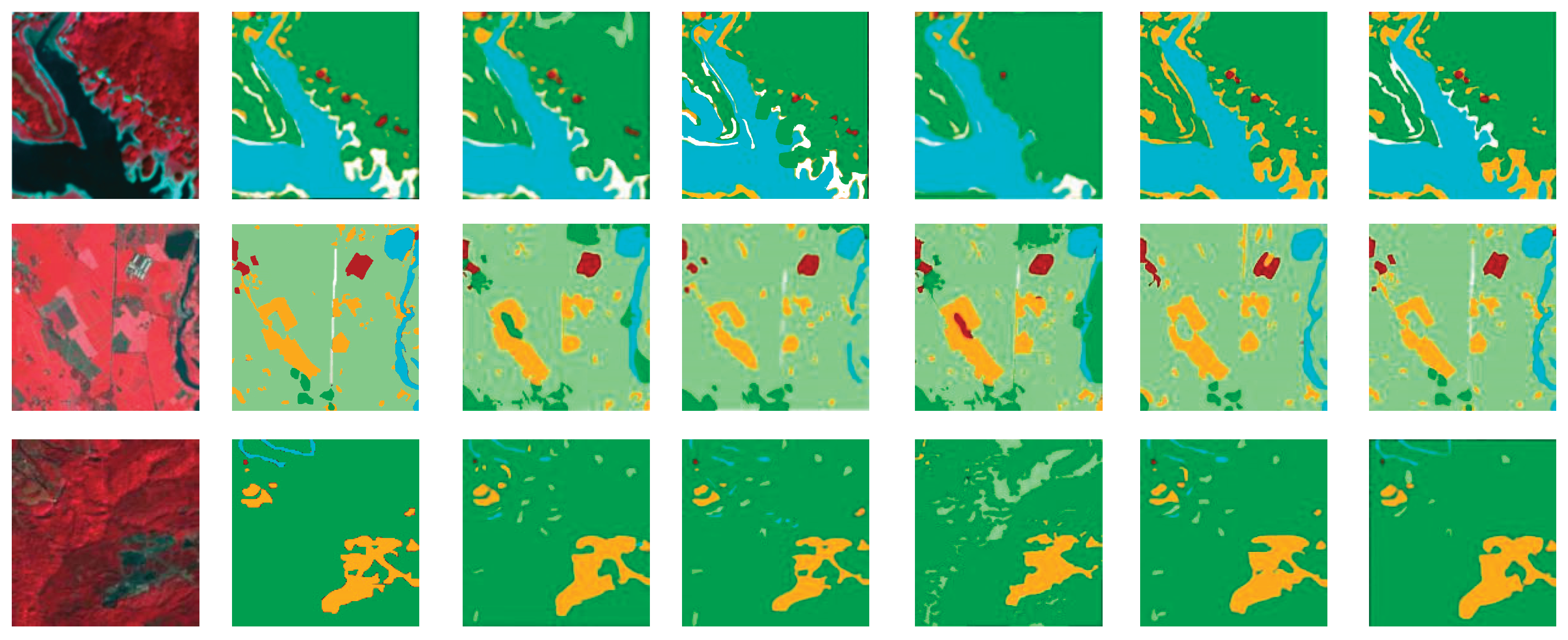

5.5.2. Results on NIRRG Forest Dataset

5.5.3. Efficiency Analysis

5.5.4. Exploration of the Adaptability of the GSwin-Unet to Fresh Datasets

6. Discussion

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation[C]//Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18. Springer international publishing, 2015: 234-241.

- Hatamizadeh, A.; Tang, Y.; Nath, V.; et al. Unetr: Transformers for 3d medical image segmentation[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision. 2022: 574-584.

- Wang, W.; Chen, C.; Ding, M.; Yu, H.; Zha, S.; Li, J. TransBTS: Multimodal Brain Tumor Segmentation Using Transformer. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2021; De Bruijne, M., et al.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12901.

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Swin-unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation[C]//European conference on computer vision. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2022: 205-218.

- Gong, Z.; French, A. P.; Qiu, G.; et al. CTranS: A Multi-Resolution Convolution-Transformer Network for Medical Image Segmentation[C]//2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI). IEEE, 2024: 1-5.

- Huang, X.; Deng, Z.; Li, D.; et al. Missformer: An effective medical image segmentation transformer[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.07162, 2021.

- Hatamizadeh, A.; Nath, V.; Tang, Y.; et al. Swin unetr: Swin transformers for semantic segmentation of brain tumors in mri images[C]//International MICCAI brainlesion workshop. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021: 272-284.

- Azad, R.; Jia, Y.; Aghdam, E. K.; et al. Enhancing medical image segmentation with TransCeption: A multi-scale feature fusion approach[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.10847, 2023.

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; et al. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers[J]. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2021, 34: 12077-12090.

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; et al. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.04306, 2021.

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; et al. Dual attention network for scene segmentation[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2019: 3146-3154.

- Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; et al. Ccnet: Criss-cross attention for semantic segmentation[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2019: 603-612.

- Zhao, B.; Hua, L.; Li, X.; et al. Weather recognition via classification labels and weather-cue maps[J]. Pattern Recognition, 2019, 95: 272-284. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; et al. Pyramid scene parsing network[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2017: 2881-2890.

- Xiao, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, B.; et al. Unified perceptual parsing for scene understanding[C]//Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 2018: 418-434.

- Mou, L.; Hua, Y.; Zhu, X. X. Relation matters: Relational context-aware fully convolutional network for semantic segmentation of high-resolution aerial images[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2020, 58(11): 7557-7569. [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929, 2020.

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; et al. Rethinking semantic segmentation from a sequence-to-sequence perspective with transformers[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2021: 6881-6890.

- Cheng, B.; Misra, I.; Schwing, A. G.; et al. Masked-attention mask transformer for universal image segmentation[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2022: 1290-1299.

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2021: 10012-10022.

- Chen, Z. M.; Wei, X. S.; Wang P, et al. Multi-label image recognition with graph convolutional networks[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2019: 5177-5186.

- Jung, H.; Park, S. Y.; Yang, S.; et al. Superpixel-based graph convolutional network for semantic segmentation[J]. 2021.

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; et al. Vision gnn: An image is worth graph of nodes[J]. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2022, 35: 8291-8303.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; et al. Attention is all you need[J]. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2017, 30.

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; et al. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2021: 568-578.

- Han, K.; Xiao, A.; Wu, E.; et al. Transformer in transformer[J]. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2021, 34: 15908-15919.

- Yuan, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; et al. Tokens-to-token vit: Training vision transformers from scratch on imagenet[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2021: 558-567.

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; et al. Pvt v2: Improved baselines with pyramid vision transformer[J]. Computational visual media, 2022, 8(3): 415-424. [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Chen, B.; Xu, J.; et al. Ds-transunet: Dual swin transformer u-net for medical image segmentation[J]. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2022, 71: 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Hu, Q. Transfuse: Fusing transformers and cnns for medical image segmentation[C]//Medical image computing and computer assisted intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th international conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, proceedings, Part I 24. Springer International Publishing, 2021: 14-24.

- Khan, A. R.; Khan, A. MaxViT-UNet: Multi-axis attention for medical image segmentation[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.08396, 2023.

- Kipf, T. N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907, 2016.

- Wan, S.; Gong, C.; Zhong, P.; et al. Hyperspectral image classification with context-aware dynamic graph convolutional network[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2020, 59(1): 597-612. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, Z.; et al. Graph convolutional subspace clustering: A robust subspace clustering framework for hyperspectral image[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2020, 59(5): 4191-4202. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, T,; Zhao, F.; et al. Dual Graph Convolutional Network for Hyperspectral Images with Spatial Graph and Spectral Multi-graph[J]. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Yao, J.; et al. Graph convolutional networks for hyperspectral image classification[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2020, 59(7): 5966-5978. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chong, Y.; et al. Global consistent graph convolutional network for hyperspectral image classification[J]. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2021, 70: 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhang, F.; Xiang, D.; et al. PolSAR image classification with multiscale superpixel-based graph convolutional network[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2021, 60: 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, T.; Shang, F.; et al. Deep fuzzy graph convolutional networks for PolSAR imagery pixelwise classification[J]. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2020, 14: 504-514. [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Zhou, F. Semi-supervised classification for PolSAR data with multi-scale evolving weighted graph convolutional network[J]. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2021, 14: 2911-2927. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D. Research on remote sensing image feature classification method based on graph neural[D]. Master Thesis, Shandong Jianzhu University, Jinan, 2022.

- Chen, X. Vehicle video object semantic segmentation method based on graph convolution[D]. Master Thesis, Beijing Jianzhu University, Beijing, 2022.

- Ma, F.; Gao, F.; Sun, J.; et al. Attention graph convolution network for image segmentation in big SAR imagery data[J]. Remote Sensing, 2019, 11(21): 2586. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xiao, L.; Yang, J.; et al. CNN-enhanced graph convolutional network with pixel-and superpixel-level feature fusion for hyperspectral image classification[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2020, 59(10): 8657-8671. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Kampffmeyer, M.; Jenssen, R. Self-constructing graph convolutional networks for semantic labeling[C]//IGARSS 2020-2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. IEEE, 2020: 1801-1804.

- Zhang, X.; Tan, X.; Chen, G.; et al. Object-based classification framework of remote sensing images with graph convolutional networks[J]. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 2021, 19: 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xiao, L.; Yang, J.; et al. Multilevel superpixel structured graph U-Nets for hyperspectral image classification[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2021, 60: 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W. G. C.; Valanarasu, J, M, J.; Patel, V. M. Spin road mapper: Extracting roads from aerial images via spatial and interaction space graph reasoning for autonomous driving[C]//2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2022: 343-350.

- Liu Q, Kampffmeyer M C, Jenssen R, et al. Multi-view self-constructing graph convolutional networks with adaptive class weighting loss for semantic segmentation[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops. 2020: 44-45.

- Cui, W.; He, X.; Yao, M.; et al. Knowledge and spatial pyramid distance-based gated graph attention network for remote sensing semantic segmentation[J]. Remote Sensing, 2021, 13(7): 1312. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, C.; Guo, J.; et al. Zero-reference deep curve estimation for low-light image enhancement[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2020: 1780-1789.

- Zeiler, M. D.; Fergus, R. Visualizing and understanding convolutional networks[C]//Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, Part I 13. Springer International Publishing, 2014: 818-833.

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J. Y.; et al. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module[C]//Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 2018: 3-19.

- Fidon, L.; Li, W.; Garcia-Peraza-Herrera, L. C.; et al. Generalised wasserstein dice score for imbalanced multi-class segmentation using holistic convolutional networks[C]//Brainlesion: Glioma, Multiple Sclerosis, Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injuries: Third International Workshop, BrainLes 2017, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2017, Quebec City, QC, Canada, September 14, 2017, Revised Selected Papers 3. Springer International Publishing, 2018: 64-76.

- Lin, T. Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; et al. Focal loss for dense object detection[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 2017: 2980-2988.

- Chen L C, Zhu Y, Papandreou G, et al. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation[C]//Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 2018: 801-818.

| Stage | PyramidViG-Ti | Output size | Swin-transformer | Output size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patch Partition | ||||

| Stem | Linear Embedding | |||

| Stage 1 | * | Swin-transformer Block×2 | ||

| Down sample | Patch Merging | |||

| Stage 2 | Swin-transformer Block×2 | |||

| Down sample | Patch Merging | |||

| Stage 3 | Swin-transformer Block×2 |

| Model Name | IoU (%) | Evaluation index | ||||||

| Forest | agricultural land | Water | Building | Bare land | Road | MIoU (%) | Ave.F1 (%) | |

| Swin-Unet | 67.23 | 70.63 | 67.26 | 66.67 | 62.83 | 62.50 | 66.19 | 79.62 |

| Swin-Unet+GCN+L1 | 67.23 | 76.03 | 66.95 | 74.14 | 75.65 | 70.00 | 71.67 | 80.43 |

| Swin-Unet+GCN+FAM+L1 | 70.09 | 76.27 | 72.07 | 75.63 | 74.79 | 74.53 | 73.90 | 84.80 |

| Swin-Unet+GCN+FAM+ZD+L1 | 70.34 | 77.59 | 72.07 | 75.63 | 76.07 | 74.77 | 74.41 | 85.30 |

| Swin-Unet+GCN+FAM+ZD+L2 | 73.04 | 78.63 | 68.64 | 76.47 | 78.26 | 75.70 | 75.13 | 85.96 |

| Model Name | IoU (%) | Evaluation index | ||||||

| Forest | agricultural land | Water | Building | Bare land | Road | MioU (%) | Ave.F1(%) | |

| DeepLab V3+ | 57.60 | 68.66 | 61.67 | 78.38 | 78.07 | 63.96 | 68.06 | 80.73 |

| Unet | 61.67 | 73.17 | 70.54 | 79.46 | 73.17 | 62.07 | 70.01 | 82.20 |

| Swin-Unet | 67.23 | 70.63 | 67.26 | 66.67 | 62.83 | 62.50 | 66.19 | 79.62 |

| TransUnet | 66.39 | 75.21 | 68.10 | 76.52 | 79.65 | 68.75 | 72.44 | 80.23 |

| Gswin-Unet | 73.04 | 78.63 | 68.64 | 76.47 | 78.26 | 75.70 | 75.13 | 83.92 |

| MioU (%) | 65.19 | 73.26 | 67.24 | 75.5 | 74.40 | 66.60 | ||

| Model Name | IoU (%) | Evaluation index | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest | Agricultural land | Water | Building | Bare land | Road | MIoU (%) | Ave.F1 (%) | |

| DeepLab V3+ | 63.39 | 73.21 | 70.23 | 61.90 | 63.33 | 70.94 | 67.17 | 80.28 |

| Unet | 60.87 | 76.58 | 72.22 | 65.04 | 71.68 | 70.83 | 69.54 | 81.92 |

| Swin-Unet | 66.12 | 67.21 | 71.20 | 66.12 | 64.96 | 61.21 | 66.13 | 79.58 |

| TransUnet | 66.96 | 67.20 | 77.78 | 71.93 | 70.69 | 68.33 | 70.48 | 82.63 |

| GSwin-Unet | 69.72 | 69.67 | 76.67 | 74.14 | 76.36 | 70.94 | 72.92 | 84.30 |

| MIoU (%) | 65.41 | 70.77 | 73.62 | 67.83 | 69.40 | 68.45 | ||

| Method | Parameters | RGB Forest | NIRRG Forest | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed (FPS) | MIoU (%) | Speed (FPS) | MIoU (%) | ||

| UNet | 25.13 MB | 239 | 70.01 | 232 | 69.54 |

| Deeplab V3+ | 38.48MB | 76 | 68.06 | 74 | 67.17 |

| Swin-Unet | 25.89MB | 63 | 66.19 | 60 | 66.13 |

| TransUnet | 100.44 | 39 | 72.44 | 37 | 70.48 |

| GSwin-Unet | 160.97 | 9 | 75.13 | 8 | 72.92 |

| Model Name | IoU (%) | Evaluation index | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest | Farmland | Water | Building | Grass | Others | MIoU (%) | Ave.F1 (%) | |

| DeepLab V3+ | 57.48 | 70.00 | 64.71 | 78.57 | 76.32 | 63.96 | 67.17 | 80.28 |

| Unet | 61.67 | 72.13 | 67.83 | 79.46 | 73.17 | 62.93 | 69.54 | 81.92 |

| Swin-unet | 65.57 | 69.60 | 66.09 | 65.32 | 60.68 | 59.06 | 66.13 | 79.58 |

| TransUnet | 65.83 | 69.92 | 66.95 | 75.86 | 75.65 | 68.75 | 70.48 | 82.63 |

| GSwin-Unet | 71.30 | 74.79 | 71.43 | 73.33 | 73.55 | 72.90 | 72.92 | 84.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).