Submitted:

15 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Cancer Immunotherapy

1.2. Gene Editing in Modern Medicine

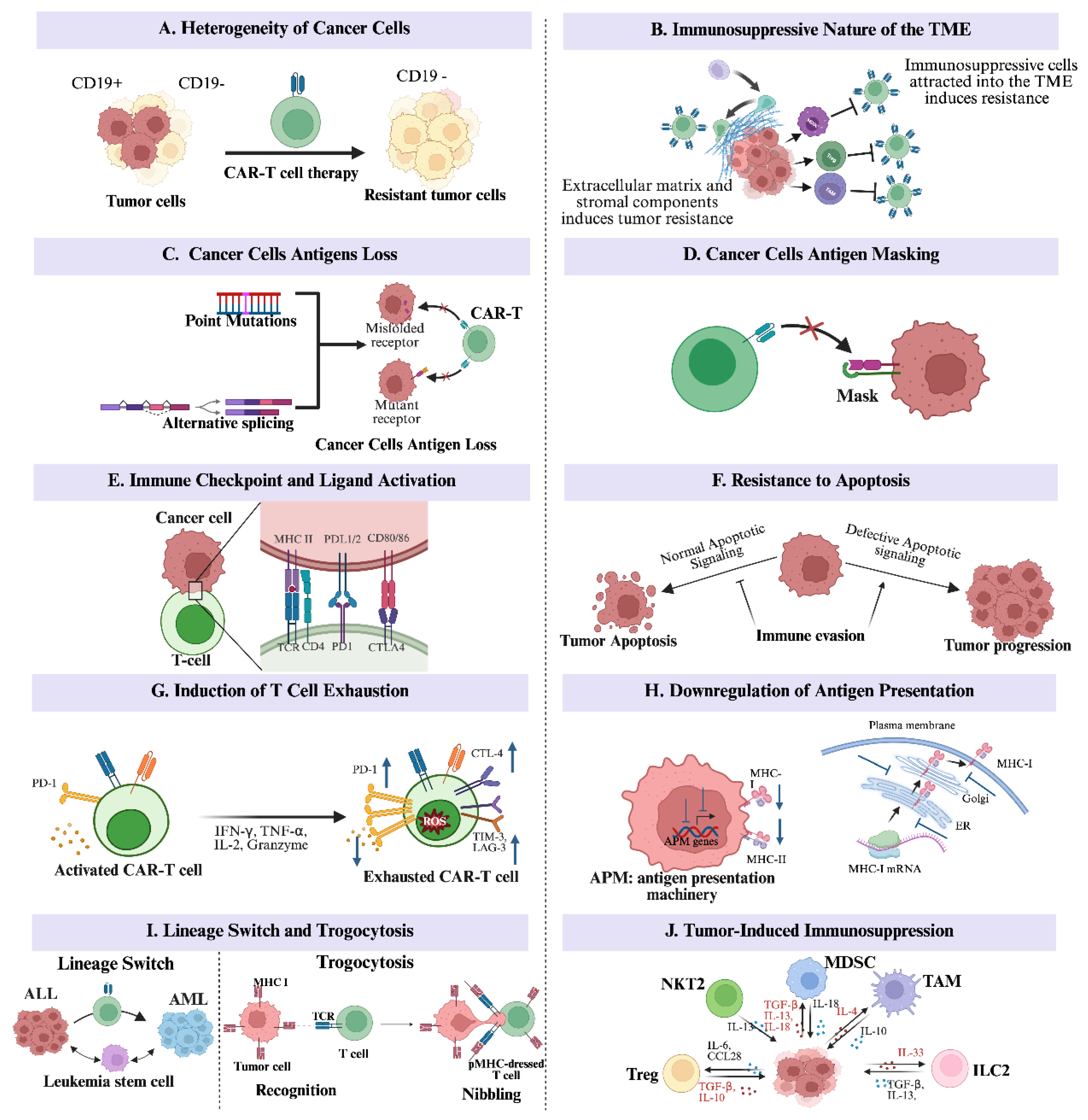

2. Immune Evasion Mechanisms in Cancer

2.1. The Heterogeneity of Cancer Cells

2.2. The Immunosuppressive Nature of the Tumor Microenvironment

2.3. Cancer Cells’ Antigens Loss from Mutation and Alternative Splicing

2.4. Cancer Cells’ Antigens Masking

2.5. Immune Checkpoint and Ligand Activation

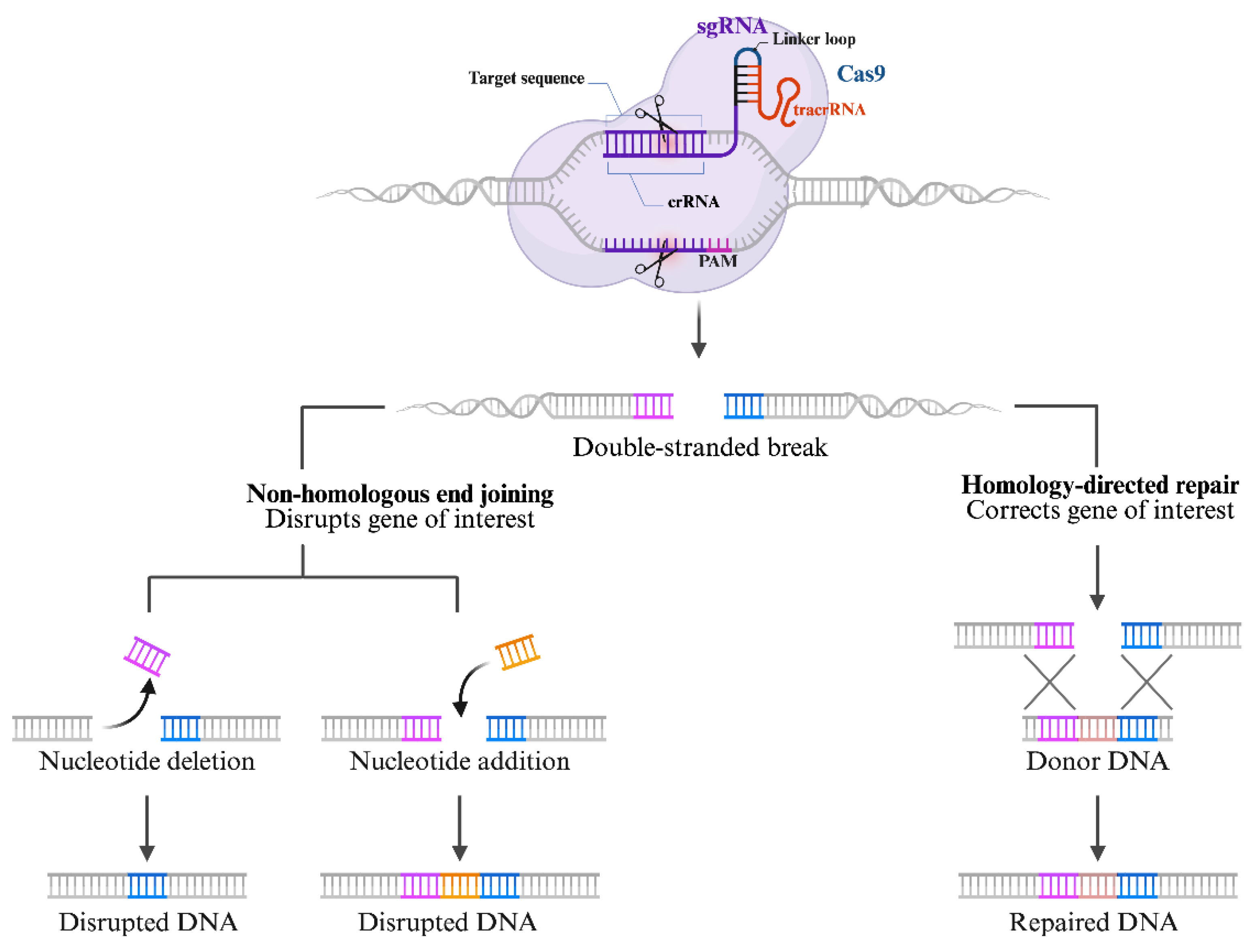

3. The CRISPR/Cas 9 Structure and Mechanisms

3.1. Overview of the CRISPR/Cas 9 Mechanisms: Guide RNA, Cas9 Enzyme, and DNA Targeting

3.2. The CRISPR/Cas 9 System in Immune System Modulation and Cancer Immunotherapy

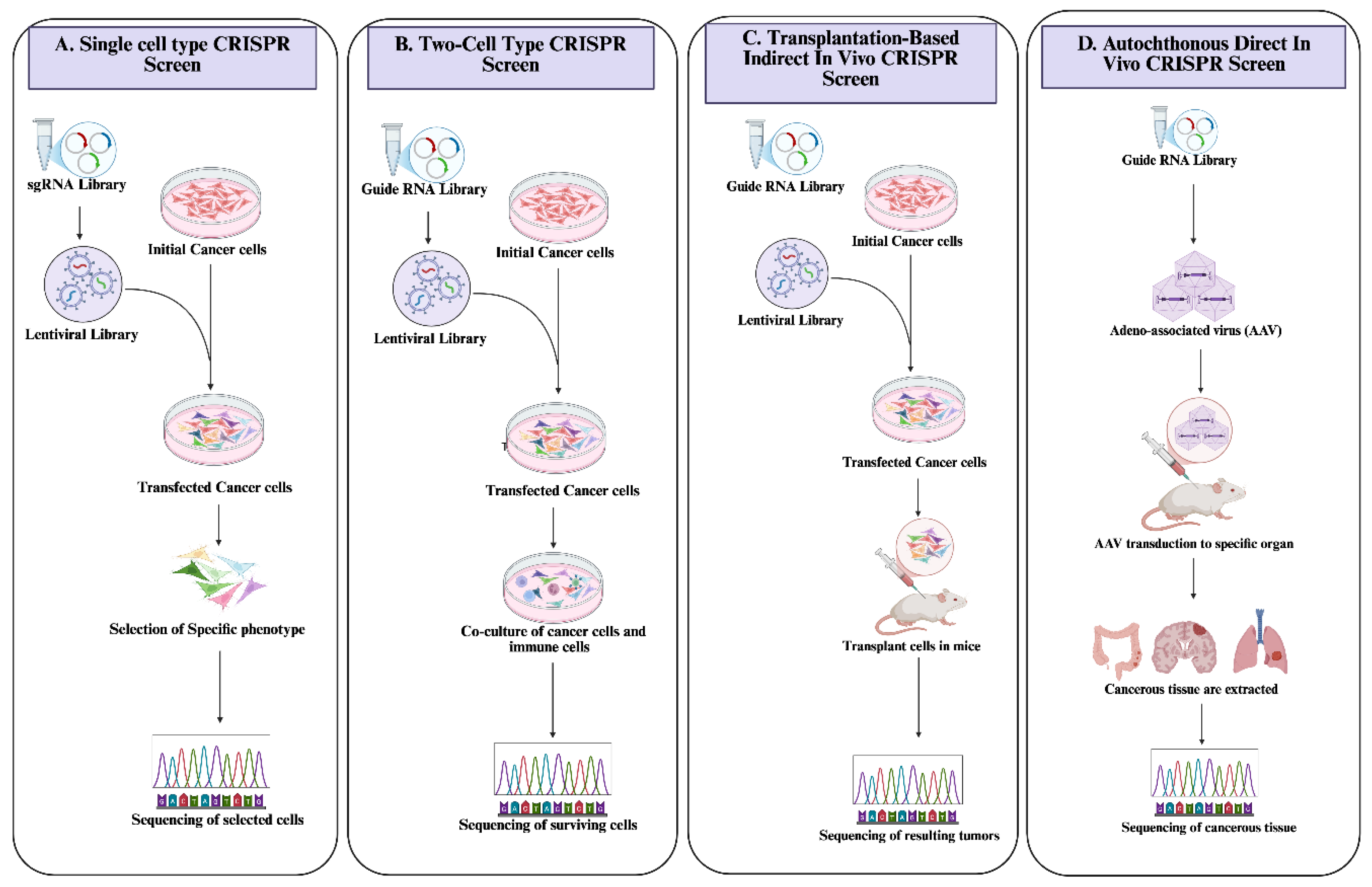

3.2.1. The CRISPR/Cas 9 Systems: A Tool for the Identification and Screening of Immunomodulatory Genes

3.2.2. The CRISPR/Cas 9 System and Immune System Manipulation in Cancer Immunotherapy

4. CRISPR-Based Approaches to Overcome Immune Evasion

4.1. Editing Immune Checkpoints

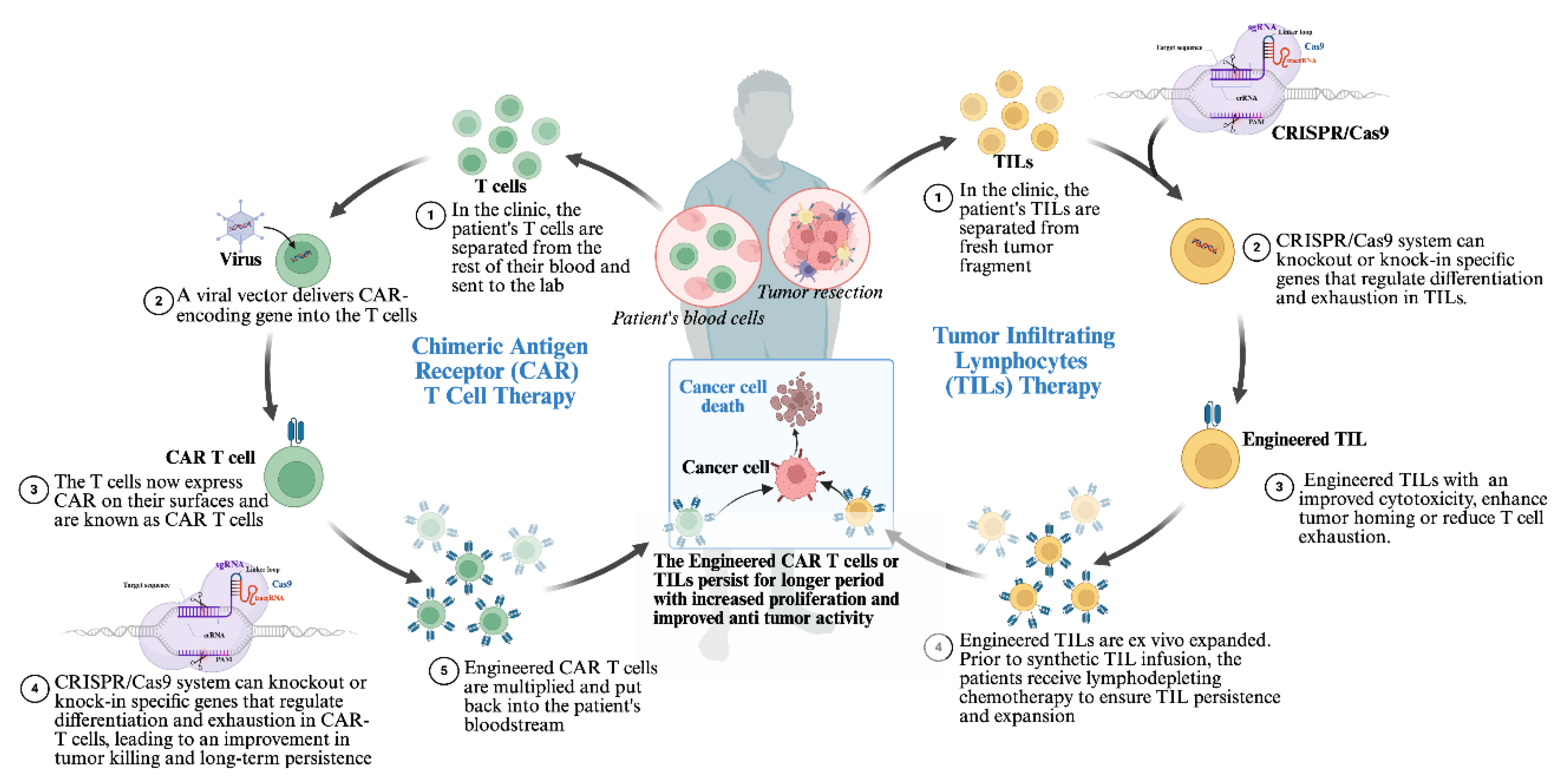

4.2. Engineering CAR-T Cells and Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs)

4.3. Disrupting Tumor-Intrinsic Immune Evasion Genes

5. Challenges and Considerations in CRISPR-Based Immunotherapy Development

5.1. Safety and Off-Target Effects

5.2. Delivery Challenges

5.3. Ethical Considerations and Regulatory Landscape

6. Future Directions and Innovations

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhou, Z. CRISPR/Cas9 technology for advancements in cancer immunotherapy: from uncovering regulatory mechanisms to therapeutic applications. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellman, I.; Coukos, G.; Dranoff, G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 2011, 480, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connor, M.J. Targeting the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Allison, J.P. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 2015, 348, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Allison, J.P. Dissecting the mechanisms of immune checkpoint therapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S.; Hackett, C.S.; Brentjens, R.J. Engineering strategies to overcome the current roadblocks in CAR T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 17, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzner, R.G.; Mackall, C.L. Tumor Antigen Escape from CAR T-cell Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.K.; Cho, S.W. The Evasion Mechanisms of Cancer Immunity and Drug Intervention in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 868695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Dotti, G.; Savoldo, B. Utilizing cell-based therapeutics to overcome immune evasion in hematologic malignancies. Blood 2016, 127, 3350–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemailem, K.S.; A Alsahli, M.; Almatroudi, A.; Alrumaihi, F.; Alkhaleefah, F.K.; Rahmani, A.H.; Khan, A.A. Current updates of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing and targeting within tumor cells: an innovative strategy of cancer management. Cancer Commun. 2022, 42, 1257–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allemailem, K.S.; Almatroodi, S.A.; Almatroudi, A.; Alrumaihi, F.; Al Abdulmonem, W.; Al-Megrin, W.A.I.; Aljamaan, A.N.; Rahmani, A.H.; Khan, A.A. Recent Advances in Genome-Editing Technology with CRISPR/Cas9 Variants and Stimuli-Responsive Targeting Approaches within Tumor Cells: A Future Perspective of Cancer Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Ran, F.A.; Cox, D.; Lin, S.; Barretto, R.; Habib, N.; Hsu, P.D.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Marraffini, L.A.; et al. Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science 2013, 339, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, A.; Musunuru, K. Genome editing in cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 14, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, D.; Venkataramani, P.; Nandi, S.; Bhattacharjee, S. CRISPR–Cas9 a boon or bane: the bumpy road ahead to cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Hong, W.; Huang, M.; Wu, M.; Zhao, X. Applications of genome editing technology in the targeted therapy of human diseases: mechanisms, advances and prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosicki, M.; Tomberg, K.; Bradley, A. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR–Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’DRiscoll, M.; Jeggo, P.A. The role of double-strand break repair — insights from human genetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006, 7, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouet, P.; Smih, F.; Jasin, M. Expression of a site-specific endonuclease stimulates homologous recombination in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1994, 91, 6064–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniecki, K.; De Tullio, L.; Greene, E.C. A change of view: homologous recombination at single-molecule resolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 19, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Greenberg, R.A. Noncanonical views of homology-directed DNA repair. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 1138–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.Y.; Pannunzio, N.R.; Adachi, N.; Lieber, M.R. Non-homologous DNA end joining and alternative pathways to double-strand break repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieber, M.R.; Gu, J.; Lu, H.; Shimazaki, N.; Tsai, A.G. Nonhomologous DNA End Joining (NHEJ) and Chromosomal Translocations in Humans. In Genome Stability and Human Diseases, vol. 50, H.-P. Nasheuer, Ed., in Subcellular Biochemistry, vol. 50., Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2010, pp. 279–296. [CrossRef]

- Delacôte, F.; Lopez, B.S. Importance of the cell cycle phase for the choice of the appropriate DSB repair pathway, for genome stability mintenance: the trans-S double-strand break repair model. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.-S. A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Z.; Tian, R.; Li, L.; Fan, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. The comparison of ZFNs, TALENs, and SpCas9 by GUIDE-seq in HPV-targeted gene therapy. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2021, 26, 1466–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaj, T.; Gersbach, C.A.; Barbas, C.F., III. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2014, 2014 31, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lino, C.A.; Harper, J.C.; Carney, J.P.; Timlin, J.A. Delivering CRISPR: a review of the challenges and approaches. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 1234–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mali, P.; Yang, L.; Esvelt, K.M.; Aach, J.; Guell, M.; DiCarlo, J.E.; Norville, J.E.; Church, G.M. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science 2013, 339, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.B.T.; Platt, R.J.; Zhang, F. Therapeutic genome editing: prospects and challenges. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-R.; Halladay, T.; Yang, L. Immune evasion in cell-based immunotherapy: unraveling challenges and novel strategies. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabilloud, T.; Potier, D.; Pankaew, S.; Nozais, M.; Loosveld, M.; Payet-Bornet, D. Single-cell profiling identifies pre-existing CD19-negative subclones in a B-ALL patient with CD19-negative relapse after CAR-T therapy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-R.; Wilson, M.; Yang, L. Target tumor microenvironment by innate T cells. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 999549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-R.; Yu, Y.; Kramer, A.; Hon, R.; Wilson, M.; Brown, J.; Yang, L. An Ex Vivo 3D Tumor Microenvironment-Mimicry Culture to Study TAM Modulation of Cancer Immunotherapy. Cells 2022, 11, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Xu, J.; Lan, H. Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor metastasis: biological roles and clinical therapeutic applications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickup, M.W.; Mouw, J.K.; Weaver, V.M. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. Embo Rep. 2014, 15, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allavena, P.; Digifico, E.; Belgiovine, C. Macrophages and cancer stem cells: a malevolent alliance. Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aramini, B.; Masciale, V.; Grisendi, G.; Banchelli, F.; D’amico, R.; Maiorana, A.; Morandi, U.; Dominici, M.; Haider, K.H. Cancer stem cells and macrophages: molecular connections and future perspectives against cancer. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 230–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Z.; Ding, S. The Crosstalk Between Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) and Tumor Cells and the Corresponding Targeted Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Yang, G.; Ye, P.; Cao, N.; Chi, X.; Yang, W.-H.; Yan, X. Macrophages Are a Double-Edged Sword: Molecular Crosstalk between Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Cancer Stem Cells. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, E.J.; Han, X.; Tribouley, C.; Wood, P.A.; Leary, R.J.; Riester, M.; Levine, J.E.; Qayed, M.; Grupp, S.A.; Boyer, M.; et al. Genetic mechanisms of target antigen loss in CAR19 therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1504–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.D.; Garfall, A.L.; Stadtmauer, E.A.; Melenhorst, J.J.; Lacey, S.F.; Lancaster, E.; Vogl, D.T.; Weiss, B.M.; Dengel, K.; Nelson, A.; et al. B cell maturation antigen–specific CAR T cells are clinically active in multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 2210–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samur, M.K.; Fulciniti, M.; Aktas Samur, A.; Bazarbachi, A.H.; Tai, Y.-T.; Prabhala, R.; Alonso, A.; Sperling, A.S.; Campbell, T.; Petrocca, F.; et al. Biallelic loss of BCMA as a resistance mechanism to CAR T cell therapy in a patient with multiple myeloma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, F.; Zhao, X.; Liu, J.; Yao, C.; Zhang, Y. Point mutation in CD19 facilitates immune escape of B cell lymphoma from CAR-T cell therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asnani, M.; Hayer, K.E.; Naqvi, A.S.; Zheng, S.; Yang, S.Y.; Oldridge, D.; Ibrahim, F.; Maragkakis, M.; Gazzara, M.R.; Black, K.L.; et al. Retention of CD19 intron 2 contributes to CART-19 resistance in leukemias with subclonal frameshift mutations in CD19. Leukemia 2019, 34, 1202–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotillo, E.; Barrett, D.M.; Black, K.L.; Bagashev, A.; Oldridge, D.; Wu, G.; Sussman, R.; LaNauze, C.; Ruella, M.; Gazzara, M.R.; et al. Convergence of Acquired Mutations and Alternative Splicing of CD19 Enables Resistance to CART-19 Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1282–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, J.; Paret, C.; El Malki, K.; Alt, F.; Wingerter, A.; Neu, M.A.; Kron, B.; Russo, A.; Lehmann, N.; Roth, L.; et al. CD19 Isoforms Enabling Resistance to CART-19 Immunotherapy Are Expressed in B-ALL Patients at Initial Diagnosis. J. Immunother. 2017, 40, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruella, M.; Xu, J.; Barrett, D.M.; Fraietta, J.A.; Reich, T.J.; Ambrose, D.E.; Klichinsky, M.; Shestova, O.; Patel, P.R.; Kulikovskaya, I.; et al. Induction of resistance to chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy by transduction of a single leukemic B cell. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1499–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warda, W.; Da Rocha, M.N.; Trad, R.; Haderbache, R.; Salma, Y.; Bouquet, L.; Roussel, X.; Nicod, C.; Deschamps, M.; Ferrand, C. Overcoming target epitope masking resistance that can occur on low-antigen-expresser AML blasts after IL-1RAP chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy using the inducible caspase 9 suicide gene safety switch. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021, 28, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Acevedo, J.A.; Dholaria, B.; Soyano, A.E.; Knutson, K.L.; Chumsri, S.; Lou, Y. Next generation of immune checkpoint therapy in cancer: new developments and challenges. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keir, M.E.; Butte, M.J.; Freeman, G.J.; Sharpe, A.H. PD-1 and Its Ligands in Tolerance and Immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 26, 677–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Xi, Q.; Shen, H.; Zhang, R. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: breakthroughs in cancer treatment. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, K.M.; Freeman, G.J.; McDermott, D.F. The Next Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade in Melanoma. Clin. Ther. 2015, 37, 764–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardoll, D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.; Labarriere, N. PD-1 expression on tumor-specific T cells: Friend or foe for immunotherapy? OncoImmunology 2017, 7, e1364828–e1364828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.C.; Orlowski, R.J.; Xu, X.; Mick, R.; George, S.M.; Yan, P.K.; Manne, S.; Kraya, A.A.; Wubbenhorst, B.; Dorfman, L.; et al. A single dose of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade predicts clinical outcomes in resectable melanoma. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garon, E.B.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hui, R.; Leighl, N.; Balmanoukian, A.S.; Eder, J.P.; Patnaik, A.; Aggarwal, C.; Gubens, M.; Horn, L.; et al. Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2018–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.E.W.; Le Tourneau, C.; Licitra, L.; Ahn, M.-J.; Soria, A.; Machiels, J.-P.; Mach, N.; Mehra, R.; Burtness, B.; Zhang, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019, 393, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G., Jr.; Fayette, J.; Guigay, J.; Colevas, A.D.; Licitra, L.; Harrington, K.; Kasper, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Even, C.; et al. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, R.; Yang, A.-G.; Zheng, G. Diversity of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1121285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowshanravan, B.; Halliday, N.; Sansom, D.M. CTLA-4: a moving target in immunotherapy. Blood 2018, 131, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.L.; Leytze, G.M.; Emswiler, J.; Peach, R.; Bajorath, J.; Cosand, W.; Linsley, P.S. Covalent Dimerization of CD28/CTLA-4 and Oligomerization of CD80/CD86 Regulate T Cell Costimulatory Interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 26762–26771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.S.K.; Sansom, D.M. The emerging role of CTLA4 as a cell-extrinsic regulator of T cell responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishino, Y.; Shinagawa, H.; Makino, K.; Amemura, M.; Nakata, A. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 5429–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolotin, A.; Quinquis, B.; Sorokin, A.; Ehrlich, S.D. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin. Microbiology 2005, 151, 2551–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourcel, C.; Salvignol, G.; Vergnaud, G. CRISPR elements in Yersinia pestis acquire new repeats by preferential uptake of bacteriophage DNA, and provide additional tools for evolutionary studies. Microbiology 2005, 151, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Oost, J.; Westra, E.R.; Jackson, R.N.; Wiedenheft, B. Unravelling the structural and mechanistic basis of CRISPR–Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Qin, Y. CRISPR/Cas9 system: recent applications in immuno-oncology and cancer immunotherapy. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Bikard, D.; Cox, D.; Zhang, F.; Marraffini, L.A. RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillary, V.E.; Ceasar, S.A. A Review on the Mechanism and Applications of CRISPR/Cas9/Cas12/Cas13/Cas14 Proteins Utilized for Genome Engineering. Mol. Biotechnol. 2022, 65, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrangou, R.; Fremaux, C.; Deveau, H.; Richards, M.; Boyaval, P.; Moineau, S.; Romero, D.A.; Horvath, P. CRISPR Provides Acquired Resistance Against Viruses in Prokaryotes. Science 2007, 315, 1709–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveau, H.; Barrangou, R.; Garneau, J.E.; Labonté, J.; Fremaux, C.; Boyaval, P.; Romero, D.A.; Horvath, P.; Moineau, S. Phage Response to CRISPR-Encoded Resistance in Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 1390–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, S.H.; Redding, S.; Jinek, M.; Greene, E.C.; Doudna, J.A. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature 2014, 507, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapranauskas, R.; Gasiunas, G.; Fremaux, C.; Barrangou, R.; Horvath, P.; Siksnys, V. The Streptococcus thermophilus CRISPR/Cas system provides immunity in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 9275–9282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, C.; Niewoehner, O.; Duerst, A.; Jinek, M. Structural basis of PAM-dependent target DNA recognition by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature 2014, 513, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiunas, G.; Barrangou, R.; Horvath, P.; Siksnys, V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2579–E2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K.S.; Grishin, N.V.; Shabalina, S.A.; Wolf, Y.I.; Koonin, E.V. A putative RNA-interference-based immune system in prokaryotes: computational analysis of the predicted enzymatic machinery, functional analogies with eukaryotic RNAi, and hypothetical mechanisms of action. Biol. Direct 2006, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieber, M.R.; Ma, Y.; Pannicke, U.; Schwarz, K. Mechanism and regulation of human non-homologous DNA end-joining. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouet, P.; Smih, F.; Jasin, M. Introduction of Double-Strand Breaks into the Genome of Mouse Cells by Expression of a Rare-Cutting Endonuclease. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yang, X.; Luo, X.; Wu, Z.; Yang, H. Modulation of cell cycle increases CRISPR-mediated homology-directed DNA repair. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Han, S.; Chang, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, C.; Chu, X. CRISPR screen in cancer: status quo and future perspectives. Am J Cancer Res 2021, 11, 1031–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhou, Z. CRISPR/Cas9 technology for advancements in cancer immunotherapy: from uncovering regulatory mechanisms to therapeutic applications. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manguso, R.T.; Pope, H.W.; Zimmer, M.D.; Brown, F.D.; Yates, K.B.; Miller, B.C.; Collins, N.B.; Bi, K.; LaFleur, M.W.; Juneja, V.R.; et al. In vivo CRISPR screening identifies Ptpn2 as a cancer immunotherapy target. Nature 2017, 547, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.B.; Wang, G.; Chow, R.D.; Ye, L.; Zhu, L.; Dai, X.; Park, J.J.; Kim, H.R.; Errami, Y.; Guzman, C.D.; et al. Systematic Immunotherapy Target Discovery Using Genome-Scale In Vivo CRISPR Screens in CD8 T Cells. Cell 2019, 178, 1189–1204.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Park, J.J.; Peng, L.; Yang, Q.; Chow, R.D.; Dong, M.B.; Lam, S.Z.; Guo, J.; Tang, E.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A genome-scale gain-of-function CRISPR screen in CD8 T cells identifies proline metabolism as a means to enhance CAR-T therapy. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 595–614.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufva, O.; Koski, J.; Maliniemi, P.; Ianevski, A.; Klievink, J.; Leitner, J.; Pölönen, P.; Hohtari, H.; Saeed, K.; Hannunen, T.; et al. Integrated drug profiling and CRISPR screening identify essential pathways for CAR T-cell cytotoxicity. Blood 2020, 135, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzelak, L.; Roesch, F.; Vaysse, A.; Biton, A.; Legendre, R.; Porrot, F.; Commère, P.; Planchais, C.; Mouquet, H.; Vignuzzi, M.; et al. IRF8 regulates efficacy of therapeutic anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. Eur. J. Immunol. 2022, 52, 1648–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagley, S.J.; Binder, Z.A.; Lamrani, L.; Marinari, E.; Desai, A.S.; Nasrallah, M.P.; Maloney, E.; Brem, S.; Lustig, R.A.; Kurtz, G.; et al. Repeated peripheral infusions of anti-EGFRvIII CAR T cells in combination with pembrolizumab show no efficacy in glioblastoma: a phase 1 trial. Nat. Cancer 2024, 5, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.D.; Yu, X.; Castano, A.P.; Darr, H.; Henderson, D.B.; Bouffard, A.A.; Larson, R.C.; Scarfò, I.; Bailey, S.R.; Gerhard, G.M.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 disruption of PD-1 enhances activity of universal EGFRvIII CAR T cells in a preclinical model of human glioblastoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, M.J.; Ngiow, S.F.; Ribas, A.; Teng, M.W.L. Combination cancer immunotherapies tailored to the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, M.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Hatabu, H.; Ramaiya, N.H.; Hodi, F.S. Incidence of Programmed Cell Death 1 Inhibitor–Related Pneumonitis in Patients With Advanced Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhou, Z. CRISPR/Cas9 technology for advancements in cancer immunotherapy: from uncovering regulatory mechanisms to therapeutic applications. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, X.; Ma, Q.; Yin, W.; Ma, X.; He, Z. CRISPR/Cas9 Gene-Editing in Cancer Immunotherapy: Promoting the Present Revolution in Cancer Therapy and Exploring More. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemailem, K.S.; A Alsahli, M.; Almatroudi, A.; Alrumaihi, F.; Al Abdulmonem, W.; A Moawad, A.; Alwanian, W.M.; Almansour, N.M.; Rahmani, A.H.; Khan, A.A. Innovative Strategies of Reprogramming Immune System Cells by Targeting CRISPR/Cas9-Based Genome-Editing Tools: A New Era of Cancer Management. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, ume 18, 5531–5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okugawa, K.; Itoh, T.; Kawashima, I.; Takesako, K.; Mazda, O.; Nukaya, I.; Yano, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamagishi, H.; Ueda, Y. Recognition of Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes induced in vitro with autologous lymphoblastoid cell line and LMP2-derived, HLA-A24-restricted 9-mer peptide. Oncol. Rep. 2004, 12, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Zou, Z.; Chen, F.; Ding, N.; Du, J.; Shao, J.; Li, L.; Fu, Y.; Hu, B.; Yang, Y.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated disruption of PD-1 on human T cells for adoptive cellular therapies of EBV positive gastric cancer. OncoImmunology 2016, 6, e1249558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepsch, V.; Hermann-Kleiter, N.; Baier, G. Beyond CTLA-4 and PD-1: Orphan nuclear receptor NR2F6 as T cell signaling switch and emerging target in cancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Lett. 2016, 178, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miftah, H.; Benthami, H.; Badou, A. Insights into the emerging immune checkpoint NR2F6 in cancer immunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2024, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiede, F.; Lu, K.-H.; Du, X.; Zeissig, M.N.; Xu, R.; Goh, P.K.; Xirouchaki, C.E.; Hogarth, S.J.; Greatorex, S.; Sek, K.; et al. PTP1B Is an Intracellular Checkpoint that Limits T-cell and CAR T-cell Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 752–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banta, K.L.; Xu, X.; Chitre, A.S.; Au-Yeung, A.; Takahashi, C.; O’gOrman, W.E.; Wu, T.D.; Mittman, S.; Cubas, R.; Comps-Agrar, L.; et al. Mechanistic convergence of the TIGIT and PD-1 inhibitory pathways necessitates co-blockade to optimize anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses. Immunity 2022, 55, 512–526.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ma, W.; Lv, G.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Chen, X.; Peng, X.; Tang, C.; Pan, Z.; Liu, R.; et al. DDR1 is identified as an immunotherapy target for microsatellite stable colon cancer by CRISPR screening. npj Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Yang, L.; Zhu, S.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Wang, Q.; Guo, L. Identifying CDC7 as a synergistic target of chemotherapy in resistant small-cell lung cancer via CRISPR/Cas9 screening. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Yu, K.; Yang, N.; Qian, X.; Tie, X.; Xu, J.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9 screen reveals that targeting TRIM34 enhances ferroptosis sensitivity and augments immunotherapy efficacy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2024, 593, 216935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Deshpande, R.; Wu, K.; Tyagi, A.; Sharma, S.; Wu, S.-Y.; Xing, F.; O’NEill, S.; Ruiz, J.; Lyu, F.; et al. Identification of TUBB3 as an immunotherapy target in lung cancer by genome wide in vivo CRISPR screening. Neoplasia 2024, 60, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.; Yang, K.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, P.; Jia, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, X.; Han, X. Synergistic photothermal cancer immunotherapy by Cas9 ribonucleoprotein-based copper sulfide nanotherapeutic platform targeting PTPN2. Biomaterials 2021, 279, 121233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; He, L.; Yin, A.; Cao, Z.; Zhu, M.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, J.; et al. Targeting GDF15 to enhance immunotherapy efficacy in glioblastoma through tumor microenvironment-responsive CRISPR-Cas9 nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dervovic, D.; Malik, A.A.; Chen, E.L.Y.; Narimatsu, M.; Adler, N.; Afiuni-Zadeh, S.; Krenbek, D.; Martinez, S.; Tsai, R.; Boucher, J.; et al. In vivo CRISPR screens reveal Serpinb9 and Adam2 as regulators of immune therapy response in lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, P.; Abarientos, A.B.; Tian, R.; Seyler, M.; Leong, J.T.; Chen, M.; Choudhry, P.; Hechler, T.; Shah, N.; Wong, S.W.; et al. CRISPR-based screens uncover determinants of immunotherapy response in multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 2899–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumelha, J.; de Castro, A.; Bah, N.; Cha, H.; Trécesson, S.d.C.; Rana, S.; Tomaschko, M.; Anastasiou, P.; Mugarza, E.; Moore, C.; et al. CRISPR–Cas9 Screening Identifies KRAS-Induced COX2 as a Driver of Immunotherapy Resistance in Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 2231–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, N.; Mu, M.; Wu, Z.; Li, H.; Tang, X.; Zhong, K.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, C.; et al. Genome-scale CRISPR–Cas9 screen reveals novel regulators of B7-H3 in tumor cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Ward, N.P.; Prieto-Farigua, N.; Kang, Y.P.; Thalakola, A.; Teng, M.; DeNicola, G.M. A CRISPR screen identifies redox vulnerabilities for KEAP1/NRF2 mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Redox Biol. 2022, 54, 102358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Gong, Y.; Jin, M.-L.; Wu, H.-L.; Guo, L.-W.; Pei, Y.-C.; Chai, W.-J.; Jiang, Y.-Z.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.-Y.; et al. In vivo multidimensional CRISPR screens identify Lgals2 as an immunotherapy target in triple-negative breast cancer. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl8247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhao, L.; Lau, Y.S.; Zhang, C.; Han, R. Genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies LGALS2 as an oxidative stress-responsive gene with an inhibitory function on colon tumor growth. Oncogene 2020, 40, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Jang, D.; Shin, S.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.E.; Oh, J.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screening identifies tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase-2 as a target for augmenting anti-PD1 efficacy. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Iyer, R.; Han, X.; Wei, J.; Li, N.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yan, M.; et al. CRISPR screening identifies the deubiquitylase ATXN3 as a PD-L1–positive regulator for tumor immune evasion. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Shen, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Yang, W.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; et al. Programmable Unlocking Nano-Matryoshka-CRISPR Precisely Reverses Immunosuppression to Unleash Cascade Amplified Adaptive Immune Response. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Park, J.J.; Peng, L.; Yang, Q.; Chow, R.D.; Dong, M.B.; Lam, S.Z.; Guo, J.; Tang, E.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A genome-scale gain-of-function CRISPR screen in CD8 T cells identifies proline metabolism as a means to enhance CAR-T therapy. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 595–614.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.B.; Wang, G.; Chow, R.D.; Ye, L.; Zhu, L.; Dai, X.; Park, J.J.; Kim, H.R.; Errami, Y.; Guzman, C.D.; et al. Systematic Immunotherapy Target Discovery Using Genome-Scale In Vivo CRISPR Screens in CD8 T Cells. Cell 2019, 178, 1189–1204.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Tokheim, C.; Gu, S.S.; Wang, B.; Tang, Q.; Li, Y.; Traugh, N.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. In vivo CRISPR screens identify the E3 ligase Cop1 as a modulator of macrophage infiltration and cancer immunotherapy target. Cell 2021, 184, 5357–5374.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Huang, Q.; Luster, T.A.; Hu, H.; Zhang, H.; Ng, W.-L.; Khodadadi-Jamayran, A.; Wang, W.; Chen, T.; Deng, J.; et al. In Vivo Epigenetic CRISPR Screen Identifies Asf1a as an Immunotherapeutic Target in Kras-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chow, R.D.; Zhu, L.; Bai, Z.; Ye, L.; Zhang, F.; Renauer, P.A.; Dong, M.B.; Dai, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. CRISPR-GEMM Pooled Mutagenic Screening Identifies KMT2D as a Major Modulator of Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1912–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Xuan, J.; Wang, L.; Shen, K.; Gao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, C.; Gu, J. Application of adoptive cell therapy in malignant melanoma. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, E.; Fletcher, B.; Palmer, D. Enhancing precision in cancer treatment: the role of gene therapy and immune modulation in oncology. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1527600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera, D.G.; Waghela, H.; Nuh, M.; Pan, J.; Lulla, P. Approved CAR-T therapies have reproducible efficacy and safety in clinical practice. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2378543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O. of the Commissioner, “FDA approves CAR-T cell therapy to treat adults with certain types of large B-cell lymphoma,” FDA. Accessed: Feb. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-car-t-cell-therapy-treat-adults-certain-types-large-b-cell-lymphoma.

- Leick, M.B.; Maus, M.V.; Frigault, M.J. Clinical Perspective: Treatment of Aggressive B Cell Lymphomas with FDA-Approved CAR-T Cell Therapies. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengsayadeth, S.; Savani, B.N.; Oluwole, O.; Dholaria, B. Overview of approved CAR-T therapies, ongoing clinical trials, and its impact on clinical practice. eJHaem 2021, 3, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Han, X.; Bai, X.; Yu, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z. Revolutionizing cancer treatment: enhancing CAR-T cell therapy with CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1354825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dötsch, S.; Svec, M.; Schober, K.; Hammel, M.; Wanisch, A.; Gökmen, F.; Jarosch, S.; Warmuth, L.; Barton, J.; Cicin-Sain, L.; et al. Long-term persistence and functionality of adoptively transferred antigen-specific T cells with genetically ablated PD-1 expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Aznar, M.A.; Rech, A.J.; Good, C.R.; Kuramitsu, S.; Da, T.; Gohil, M.; Chen, L.; Hong, S.-J.A.; Ravikumar, P.; et al. Deletion of the inhibitory co-receptor CTLA-4 enhances and invigorates chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Immunity 2023, 56, 2388–2407.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, M.; Li, N.; Mu, W.; Wei, X.-F.; Han, W.; Wang, H. TGF-β inhibition via CRISPR promotes the long-term efficacy of CAR T cells against solid tumors. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.L.; Choi, J.; Staser, K.; Ritchey, J.K.; Devenport, J.M.; Eckardt, K.; Rettig, M.P.; Wang, B.; Eissenberg, L.G.; Ghobadi, A.; et al. An “off-the-shelf” fratricide-resistant CAR-T for the treatment of T cell hematologic malignancies. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1970–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presti, D.; Dall’oLio, F.G.; Besse, B.; Ribeiro, J.M.; Di Meglio, A.; Soldato, D. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) as a predictive biomarker of response to checkpoint blockers in solid tumors: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2022, 177, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Deng, J.; Rao, S.; Guo, S.; Shen, J.; Du, F.; Wu, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, M.; et al. Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) Therapy for Solid Tumor Treatment: Progressions and Challenges. Cancers 2022, 14, 4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, S.; Donia, M.; Gastman, B.; Besser, M.; Brown, R.; Coukos, G.; Creelan, B.; Mullinax, J.; Sondak, V.K.; Yang, J.C.; et al. Art of TIL immunotherapy: SITC’s perspective on demystifying a complex treatment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, A.J.; Lee, S.M.; de Spéville, B.D.; Gettinger, S.N.; Häfliger, S.; Sukari, A.; Papa, S.; Rodriguez-Moreno, J.F.; Finckenstein, F.G.; Fiaz, R.; et al. Lifileucel, an Autologous Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Monotherapy, in Patients with Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Resistant to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesney, J.; Lewis, K.D.; Kluger, H.; Hamid, O.; Whitman, E.; Thomas, S.; Wermke, M.; Cusnir, M.; Domingo-Musibay, E.; Phan, G.Q.; et al. Efficacy and safety of lifileucel, a one-time autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cell therapy, in patients with advanced melanoma after progression on immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies: pooled analysis of consecutive cohorts of the C-144-01 study. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, M.L.M.; Yang, J.C. Lifileucel: FDA-approved T-cell therapy for melanoma. Oncologist 2024, 29, 648–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. of the Commissioner, “FDA Approves First Cellular Therapy to Treat Patients with Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma,” FDA. Accessed: Feb. 14, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.fda.

- Schlabach, M.R.; Lin, S.; Collester, Z.R.; Wrocklage, C.; Shenker, S.; Calnan, C.; Xu, T.; Gannon, H.S.; Williams, L.J.; Thompson, F.; et al. Rational design of a SOCS1-edited tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy using CRISPR/Cas9 screens. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C.A.; Bennett, E.P.; Kverneland, A.H.; Svane, I.M.; Donia, M.; Met, Ö. Highly efficient PD-1-targeted CRISPR-Cas9 for tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte-based adoptive T cell therapy. Mol. Ther. - Oncolytics 2022, 24, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Gong, Y.; Jin, M.-L.; Wu, H.-L.; Guo, L.-W.; Pei, Y.-C.; Chai, W.-J.; Jiang, Y.-Z.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.-Y.; et al. In vivo multidimensional CRISPR screens identify Lgals2 as an immunotherapy target in triple-negative breast cancer. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl8247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, K.N.; Bender, A.; Bowles, A.; Bott, A.J.; Tay, J.; Grossmann, A.H.; Rutter, J.; Ducker, G.S. SLC7A5 is required for cancer cell growth under arginine-limited conditions. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashidi, A.; Füchtbauer, E.-M.; Vahabzadeh, Z.; Soleimani, F.; Rahimi, K.; Nikkhoo, B.; Fakhari, S.; Erfan, M.B.K.; Azarnezhad, A.; Pooladi, A.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of DYRK1B in triple-negative breast cancer cells: implications for cell proliferation, apoptosis, and therapeutic sensitivity. Biochem. Eng. J. 2024, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tokheim, C.; Gu, S.S.; Wang, B.; Tang, Q.; Li, Y.; Traugh, N.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. In vivo CRISPR screens identify the E3 ligase Cop1 as a modulator of macrophage infiltration and cancer immunotherapy target. Cell 2021, 184, 5357–5374.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Du, Y.; Sun, Q.; Gao, D.; Yuan, Q.; Zhou, Y.; et al. CRISPR-based in situ engineering tumor cells to reprogram macrophages for effective cancer immunotherapy. Nano Today 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhou, P.; Li, X.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Han, D.; Mei, T.; et al. Disruption of tumor-intrinsic PGAM5 increases anti-PD-1 efficacy through the CCL2 signaling pathway. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e009993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Khorramian-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Shafieizadeh, M.; Mahmoudi, E.; Eskandari, F.; Rashidi, M.; Arshi, A.; Mokhtari-Farsani, A. Comprehensive review of CRISPR-based gene editing: mechanisms, challenges, and applications in cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Luo, X.; Zhu, M.; Liu, N.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, C.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; et al. Synergistic strategies for glioblastoma treatment: CRISPR-based multigene editing combined with immune checkpoint blockade. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Barzi, M.; Furey, N.; Kim, H.R.; Pankowicz, F.P.; Legras, X.; Elsea, S.H.; Hurley, A.E.; Yang, D.; Wheeler, D.A.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9 gene therapy increases the risk of tumorigenesis in the mouse model of hereditary tyrosinemia type I. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.N.; Nakagawa, R.; Okazaki, S.; Hirano, H.; Kobayashi, K.; Kusakizako, T.; Nishizawa, T.; Yamashita, K.; Nishimasu, H.; Nureki, O. Structure of the miniature type V-F CRISPR-Cas effector enzyme. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 558–570.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, L.B.; Burstein, D.; Chen, J.S.; Paez-Espino, D.; Ma, E.; Witte, I.P.; Cofsky, J.C.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Banfield, J.F.; Doudna, J.A. Programmed DNA destruction by miniature CRISPR-Cas14 enzymes. Science 2018, 362, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-J.; Ju, S.; Jung, W.J.; Jeong, T.Y.; Yoon, D.E.; Lee, J.H.; Yang, J.; Lee, H.; Choi, J.; Kim, H.S.; et al. Robust genome editing activity and the applications of enhanced miniature CRISPR-Cas12f1. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Ouyang, X.; Zhu, G.; Zhong, J. Letter: The risk-benefit balance of CRISPR-Cas screening systems in gene editing and targeted cancer therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Tan, H.; Cong, X.; Liu, J.; Xin, Y.; Wang, J.; Guan, M.; Li, J.; Zhu, G.; Meng, X.; et al. Optimized lipid nanoparticles enable effective CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in dendritic cells for enhanced immunotherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 15, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, K.; Deng, H.; Kong, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, T.; Hu, Q.; Hu, M.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Z. Reshaping Tumor Immune Microenvironment through Acidity-Responsive Nanoparticles Featured with CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Attenuation and Chemotherapeutics-Induced Immunogenic Cell Death. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 16018–16030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piergentili, R.; Del Rio, A.; Signore, F.; Ronchi, F.U.; Marinelli, E.; Zaami, S. CRISPR-Cas and Its Wide-Ranging Applications: From Human Genome Editing to Environmental Implications, Technical Limitations, Hazards and Bioethical Issues. Cells 2021, 10, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanoudakis, D. Integrating CRISPR Technology with Key Genetic Markers in Pancreatic Cancer: A New Frontier in Targeted Therapies. SynBio 2025, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribbs, A.P.; Perera, S.M.W. Science and Bioethics of CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing: An Analysis Towards Separating Facts and Fiction. Yale J Biol Med 2017, 90, 625–634. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Avila, L.U.; Vega-López, J.M.; Pelcastre-Rodríguez, L.I.; Cabrero-Martínez, O.A.; Hernández-Cortez, C.; Castro-Escarpulli, G. The Challenge of CRISPR-Cas Toward Bioethics. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Morris, “CRISPR Therapeutics for Pancreatic Cancer,” Mar. 16, 2024, Research Archive of Rising Scholars. [CrossRef]

- Vimal, S.; Madar, I.H.; Thirumani, L.; Thangavelu, L.; Sivalingam, A.M. CRISPR/Cas9: Role of genome editing in cancer immunotherapy. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Khorramian-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Shafieizadeh, M.; Mahmoudi, E.; Eskandari, F.; Rashidi, M.; Arshi, A.; Mokhtari-Farsani, A. Comprehensive review of CRISPR-based gene editing: mechanisms, challenges, and applications in cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, A.; McClements, M.E.; MacLaren, R.E. CRISPR-Cas9 DNA Base-Editing and Prime-Editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akyürek, E.; Uysal, B.; Gülden, G.; Taştan, C. The Effect Of Molecular Genetic Mechanisms On Drug Addiction And Related New Generation CRISPR Gene Engineering Applications. Gene Ed. 2021, 2, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Agarwal, V.; Jindal, D.; Pancham, P.; Agarwal, S.; Mani, S.; Tiwari, R.K.; Das, K.; Alghamdi, B.S.; Abujamel, T.S.; et al. Recent Updates on Corticosteroid-Induced Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Theranostic Advancements through Gene Editing Tools. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Majeed, S.; Hoque, M.Z.; Ahmad, I. Latest Developed Strategies to Minimize the Off-Target Effects in CRISPR-Cas-Mediated Genome Editing. Cells 2020, 9, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.; Prasad, M.K. Beyond the promise: evaluating and mitigating off-target effects in CRISPR gene editing for safer therapeutics. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 11, 1339189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, F.; Rudin, C.M.; Sen, T. CRISPR Gene Therapy: Applications, Limitations, and Implications for the Future. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhou, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, E.; He, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, Z.; Paek, C.; Lei, J.; et al. Engineering of Cas12a nuclease variants with enhanced genome-editing specificity. PLOS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalev, M.A.; Davletshin, A.I.; Karpov, D.S. Engineering Cas9: next generation of genomic editors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Biswas, R.; Bugde, P.; Li, J.; Liu, D.-X.; Li, Y. Application of CRISPR-Cas9 System to Study Biological Barriers to Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Call, S.N.; Andrews, L.B. CRISPR-Based Approaches for Gene Regulation in Non-Model Bacteria. Front. Genome Ed. 2022, 4, 892304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendixen, L.; Jensen, T.I.; Bak, R.O. CRISPR-Cas-mediated transcriptional modulation: The therapeutic promises of CRISPRa and CRISPRi. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 1920–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laufer, B.I.; Singh, S.M. Strategies for precision modulation of gene expression by epigenome editing: an overview. Epigenetics Chromatin 2015, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djajawi, T.M.; Wichmann, J.; Vervoort, S.J.; Kearney, C.J. Tumor immune evasion: insights from CRISPR screens and future directions. FEBS J. 2023, 291, 1386–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Sutton, J. Personalized medicine could transform healthcare. Biomed. Rep. 2017, 7, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, G.; Bitew, M. Revolutionizing Personalized Medicine: Synergy with Multi-Omics Data Generation, Main Hurdles, and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, E.; Fletcher, B.; Palmer, D. Enhancing precision in cancer treatment: the role of gene therapy and immune modulation in oncology. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1527600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kang, Y.K.; Shim, G. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Customizing Strategies for Adoptive T-Cell Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caforio, M.; Iacovelli, S.; Quintarelli, C.; Locatelli, F.; Folgiero, V. GMP-manufactured CRISPR/Cas9 technology as an advantageous tool to support cancer immunotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Greene, L.A.; Mnatsakanyan, H.; Badr, C.E. Revolutionizing Brain Tumor Care: Emerging Technologies and Strategies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedipour, F.; Zahedipour, F.; Zamani, P.; Jaafari, M.R.; Sahebkar, A. Harnessing CRISPR technology for viral therapeutics and vaccines: from preclinical studies to clinical applications. Virus Res. 2024, 341, 199314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Ananthaswamy, N.; Jain, S.; Batra, H.; Tang, W.-C.; Lewry, D.A.; Richards, M.L.; David, S.A.; Kilgore, P.B.; Sha, J.; et al. A universal bacteriophage T4 nanoparticle platform to design multiplex SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates by CRISPR engineering. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, N.J.; O’dOnovan, M.C. The genetics of neuropsychiatric disorders. Brain Neurosci. Adv. 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barešić, A.; Nash, A.J.; Dahoun, T.; Howes, O.; Lenhard, B. Understanding the genetics of neuropsychiatric disorders: the potential role of genomic regulatory blocks. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 25, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Significant Target | Target Function | Target | CRISPR/Cas 9 Delivery Vector | Therapeutic Implication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDR1 | DDR1 is identified as a collagen receptor involved in colorectal cancer (CRC) liver metastasis and the related stromal response | CRC cells | Lentiviral vector | Blocking DDR1 promoted CD8+ T cell infiltration and increased the sensitivity of microsatellite stable (MSS) CRC mouse models to PD-1 inhibition | [103] |

| CDC7 | A serine/threonine kinase essential for DNA replication, also implicated in small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) resistance | SCLC cell line | Lentiviral vector | Knocking down CDC7 expression in chemotherapy-resistant SCLC cells resulted in a lower IC50 and enhanced the effectiveness of chemotherapy | [104] |

| TRIM34 | It promotes resistance to ferroptosis by inhibiting the degradation of GPX4 mRNA, contributing to the progression of Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | HCC cell line Huh7 | Lentiviral vector | Targeted knockdown of TRIM34 in HCC cells enhanced their response to anti-PD-1 therapy | [105] |

| TUBB3 | TUBB3, a member of the tubulin family that encodes βIII-tubulin, was first recognized as a marker for neurons. Increased expression of TUBB3 is associated with tumor progression | Lung cancer cell lines (CMT167cells and C57BL/6) | Lentiviral vector | Inhibiting TUBB3 makeS cells resistant to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy more vulnerable to T cell-mediated destruction by reducing the expression of PD-L1 | [106] |

| PTPN2 | Ptpn2 encodes a protein tyrosine phosphatase involved in regulating various intracellular processes, including IFNγ signaling, which it inhibits by dephosphorylating STAT1 and JAK1 | Malignant melanoma cell line (A375 cells) | CuS-RNP@PEI nanoparticles | The knockdown of PTPN2 significantly boosted CD8+ T cell infiltration and cytokine production within the tumor microenvironment, leading to a stronger immune response and increased tumor sensitivity to immunotherapy | [107] |

| GDF15 | Recognized as a crucial element in immune evasion | Glioblastoma cells | angiopep-2-decorated, glutathione (GSH)-responsive nanoparticles [ANPSS(Cas9/sgGDF15)] | Deletion of GDF15 in glioblastoma cells alleviated immunosuppression in the TME, thereby enhancing the antitumor efficacy of ICB therapy. | [108] |

| ADAM2 | A cancer testis antigen whose expression suppresses T cell immune response by reducing IFNγ and TNFα signaling. | Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) cell lines | Lentiviral vector | Blocking ADAM2 may improve cancer immunotherapy in tumors that rely on it for immune evasion | [109] |

| HDAC7 and genes involved in the Sec61 pathway | HDAC7 is a crucial transcriptional corepressor, and Sec61 is a translocon. Both have been demonstrated to reduce the expression of BCMA, a key immunotherapy target in multiple myeloma | Multiple Myeloma cell lines | lentiviral vector | Silencing HDAC7 increases BCMA expression, while inhibiting Sec61 improves the antimyeloma effectiveness of a BCMA-targeted antibody-drug conjugate | [110] |

| COX2 | Produces an immunosuppressive molecule prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) | Model of KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma | Lentiviral vector | Targeting the COX2/PGE2 signaling pathway enhances the response of KRAS-mutant lung tumors to anti-PD1 therapy and delays tumor relapse following KRAS inhibition | [111] |

| SP20H | Upregulates the expression of B7-H3 (a receptor that suppresses T cells activation) in tumor cells | Ovarian cancer cells | Lentiviral vector | Deleting the SP20H gene in tumors inhibits tumor growth, increases the ratio of CD8+/CD4+ T cells, and decreases M2 macrophage infiltration in SP20H-deficient tumors. | [112] |

| KEAP1/NRF2 | KEAP1 regulates the degradation of NRF2. | Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Cell | Lentiviral vector | [113] | |

| Lgals2 | Galectin-2 (Lgals2), a β-galactoside-binding lectin, modulates the immune response by regulating inflammation and immune cell interactions. | 4 T1 cell lines | pCDH/Lentiviral vector | Using an inhibitory antibody to block Lgals2 effectively suppresses tumor growth and reactivates the immune system. The study findings suggest that Lgals2 may serve as a potential target for immunotherapy. | [114] |

| Lgals2 | Lgals2, a β-galactoside-binding lectin, modulates the immune response by regulating inflammation and immune cell interactions. | HEK293 cell lines | Lentiviral vector | The overexpression of Gal-2 reduced the proliferation of human colon epithelial cells and diminished H2O2-induced STAT3 phosphorylation. The study highlighted the suppressive function of Gal-2 in colon tumor proliferation and its potential as a therapeutic target in cancer therapy. | [115] |

| TPST2 | TPST2 is an enzyme primarily known for catalyzing the sulfation of tyrosine residues in proteins. This post-transcriptional modification is essential for many cellular processes, including cell signaling and cell adhesion. | Human breast cell lines (MDA-MB-231 and MDA- MB-468) and mouse colon cancer cell line (MC38), | Lentiviral vector | Reducing TPST2 in cancer cells increased the effectiveness of anti-PD1 antibodies in syngeneic tumor models by enhancing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. The novel role of TPST2 is proposed as an inhibitor of cancer immunotherapy and one of the targets of immune checkpoint cancer immunotherapy. | [116] |

| ATXN3 | ATXN3 functions as a deubiquitinase for various PD-L1 transcription factors in tumor cells. | LLC1/B16 cells | Lentiviral vector | The specific disruption of ATXN3 resulted in a significant decrease in PD-L1 transcription, ultimately enhancing the immune system’s antitumor effect by working synergistically with checkpoint blockade therapy. The study emphasizes the importance of identifying ATXN3 for its positive regulation of CD274 gene transcription and its potential as a target to enhance the effectiveness of cancer immunotherapy. | [117] |

| Ptpn 2/PD-L1 | Ptpn2 regulates intracellular process including IFNγ signaling while PD-L1 is a ligand that interacts with program cell receptors in immune checkpoint mechanism | B1-F10 cells | PX333 | The disruption of PTPN2 and PD-L1 reinvigorates the immune system by halting the immune checkpoint effect. Additionally, the JAK/STAT pathway is reactivated following the deletion of PTPN2, which promotes the vulnerability of tumor cells to CD+ T cells. | [118] |

| PRODH2 | An enzyme that plays an important role in proline metabolism. | HEK293FT, E0771, and MCF7 cells. | Lentiviral vector | The specific overexpression or knock-in of PRODH2 improved the CAR-T based killing and the in vivo effectiveness in various cancer models. | [119] |

| DHX37 | Plays a key role in RNA metabolism, particularly in the regulation of gene expression | Murine breast cancer cells | Lentiviral vector | Infiltration and degranulation assays highlighted RNA helicase Dhx37 as a critical factor. Knockout of Dhx37 enhanced the efficacy of antigen-specific CD8 T cells in fighting triple-negative breast cancer in vivo. | [120] |

| Cop1 | Known for its role in recruiting M2-type macrophages. | 4 T1 cells | Lentiviral vector | Disruption of Cop 1 inhibits cancer cells’ immune escape and enhances the effectiveness of ICB. | [121] |

| Asf1a | ASF1 is a histone H3-H4 chaperone conserved from yeast to human cells | Lung cancer cell lines | pXPR-GFP-Blast vector | Inhibition of Asf1a sensitizes tumor cells to anti-PD-1 therapy. | [122] |

| KM2D | KM2D encodes a histone H3K4 methyltransferase, one of the genes mutated in cancer patients. | E0771, B16F10 MA1L, LLC, and MB49 cells | AAV vector | The loss of KM2D increases tumor cell sensitivity to ICB by boosting tumor immunogenicity. | [123] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).