Submitted:

15 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

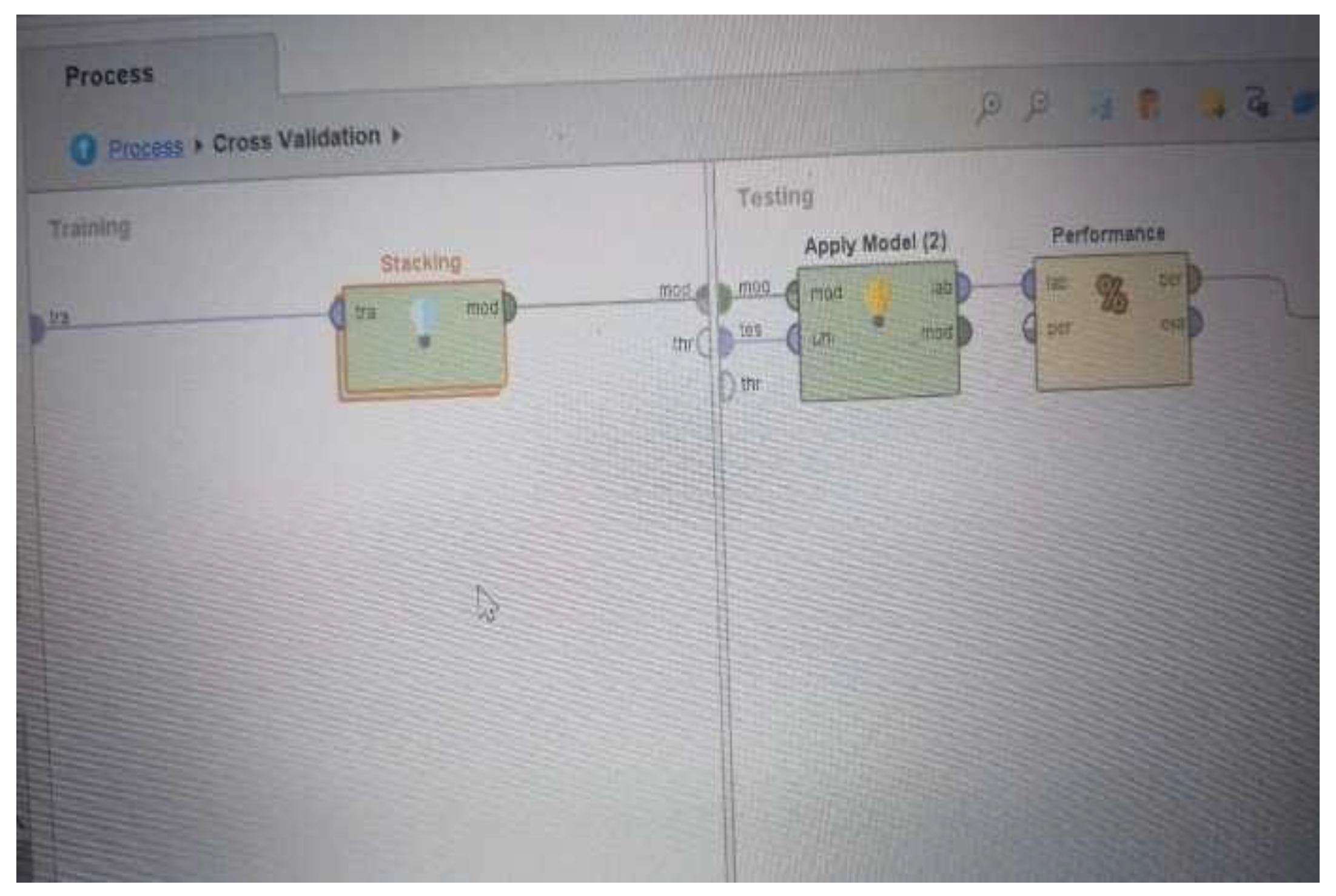

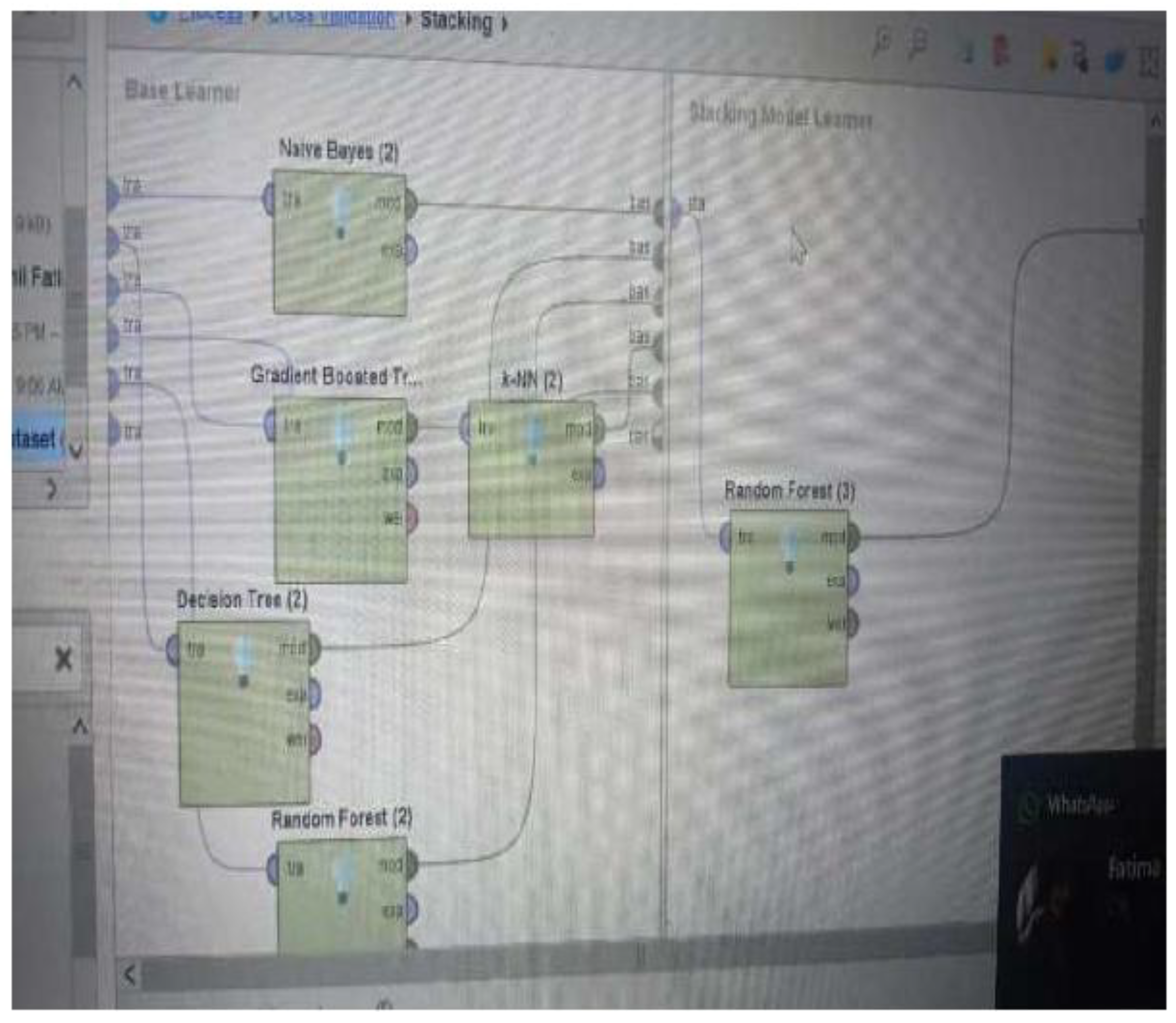

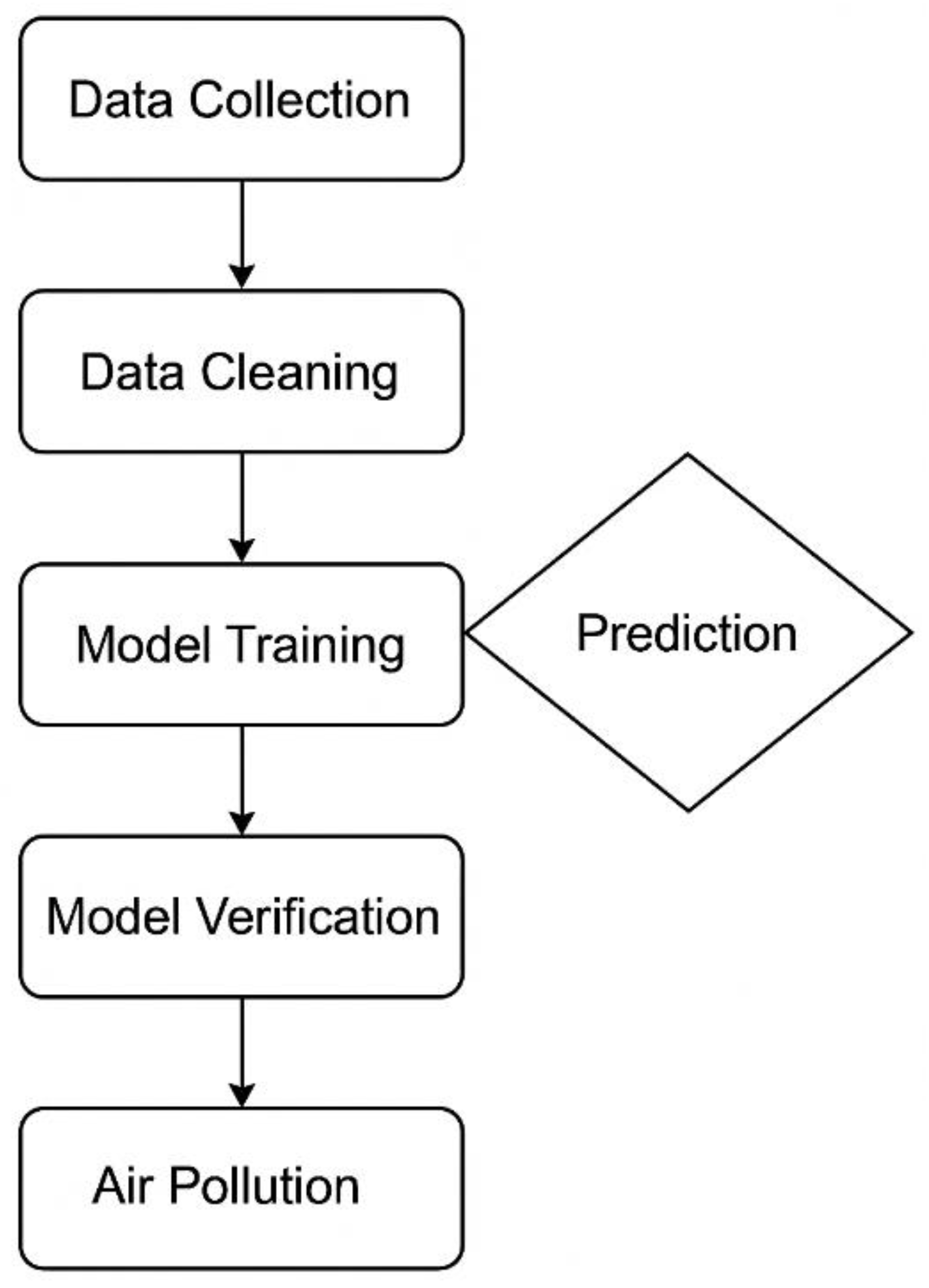

3. Proposed Methodology

- (a)

- KNN: Classifies data based on similarity to nearby data points.

- (b)

- Decision Tree: Tree-based model with branching decisions for multi-class classification.

- (c)

- Random Forest: Ensemble method using multiple decision trees.

- (d)

- Naive Bayes: Probabilistic classifier effective for binary and multi-class problems.

4. Results

4.1. Dataset Description

4.2. Performance Comparison of Algorithms

4.3. Confusion Matrix and Classification Report

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

References

- U. A. Bhatti et al., “Time series analysis and forecasting of air pollution particulate matter (PM2.5): An SARIMA and factor analysis approach,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 41019–41031, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. A. D. Nguyen et al., “Deep-learning based visualization tool for air pollution forecast,” IEEE Software, vol. PP, no. November, pp. 1–8, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Abboud, Y. Taher, K. Zeitouni, and A. M. Olteanu-Raimond, “How opportunistic mobile monitoring can enhance air quality assessment?,” Geoinformatica, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 679–710, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Rodrigues et al., “Assessing air pollution in European cities to support a citizen-centered approach to air quality management,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 799, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. T. S. Environment, U. B. Ntesat, D. Ojadi, C. Emeka, and R. N. Okparanma, “Ambient air quality and human health risk assessment of heavy metals in a potentially toxic silver-polluted environment,” Resources and Environmental Economics, no. January, 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Sannoh et al., “Air pollution we breathe: Assessing the air quality and human health impact in a megacity of Southeast Asia,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 942, p. 173403, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Song, M. P. Kwan, and J. Huang, “Assessment of air pollution and air quality perception mismatch using mobility-based real-time exposure,” PLoS ONE, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 1–24, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, D., & Kuipers, B. (1991). Process monitoring and diagnosis: a model-based approach. IEEE expert, 6(3), 67-74.

- Liu, Q., Cui, B., & Liu, Z. (2024). Air quality class prediction using machine learning methods based on monitoring data and secondary modeling. Atmosphere, 15(5), 553.

- M. Mannan and S. G. Al-Ghamdi, “Indoor air quality in buildings: A comprehensive review on the factors influencing air pollution in residential and commercial structures,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 1–24, 2021. [CrossRef]

- U. Rehman et al., “A machine learning--based framework for accurate and early diagnosis of liver diseases: A comprehensive study on feature selection, data imbalance, and algorithmic performance,” International Journal of Intelligent Systems, vol. 2024, no. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Ali et al., “A sequential machine learning-cum-attention mechanism for effective segmentation of brain tumor,” Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 12, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Mir et al., “A novel approach for the effective prediction of cardiovascular disease using applied artificial intelligence techniques,” ESC Heart Failure, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nawaz et al., “A comprehensive literature review of application of artificial intelligence in functional magnetic resonance imaging for disease diagnosis,” Applied Artificial Intelligence, pp. 1–19, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Muzafar, S., & Jhanjhi, N. Z. (2020). Success stories of ICT implementation in Saudi Arabia. In Employing Recent Technologies for Improved Digital Governance (pp. 151-163). IGI Global Scientific Publishing.

- Jabeen, T., Jabeen, I., Ashraf, H., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Yassine, A., & Hossain, M. S. (2023). An intelligent healthcare system using IoT in wireless sensor network. Sensors, 23(11), 5055.

- Shah, I. A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Laraib, A. (2023). Cybersecurity and blockchain usage in contemporary business. In Handbook of Research on Cybersecurity Issues and Challenges for Business and FinTech Applications (pp. 49-64). IGI Global.

- Hanif, M., Ashraf, H., Jalil, Z., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Humayun, M., Saeed, S., & Almuhaideb, A. M. (2022). AI-based wormhole attack detection techniques in wireless sensor networks. Electronics, 11(15), 2324.

- Shah, I. A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Amsaad, F., & Razaque, A. (2022). The role of cutting-edge technologies in industry 4.0. In Cyber Security Applications for Industry 4.0 (pp. 97-109). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Humayun, M., Almufareh, M. F., & Jhanjhi, N. Z. (2022). Autonomous traffic system for emergency vehicles. Electronics, 11(4), 510.

- Muzammal, S. M., Murugesan, R. K., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Jung, L. T. (2020, October). SMTrust: Proposing trust-based secure routing protocol for RPL attacks for IoT applications. In 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence (ICCI) (pp. 305-310). IEEE.

- Brohi, S. N., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Brohi, N. N., & Brohi, M. N. (2023). Key applications of state-of-the-art technologies to mitigate and eliminate COVID-19. Authorea Preprints.

- Khalil, M. I., Humayun, M., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Talib, M. N., & Tabbakh, T. A. (2021). Multi-class segmentation of organ at risk from abdominal ct images: A deep learning approach. In Intelligent Computing and Innovation on Data Science: Proceedings of ICTIDS 2021 (pp. 425-434). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Humayun, M., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Niazi, M., Amsaad, F., & Masood, I. (2022). Securing drug distribution systems from tampering using blockchain. Electronics, 11(8), 1195.

- Muzammal, S. M., Murugesan, R. K., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Jung, L. T. (2020, October). SMTrust: Proposing trust-based secure routing protocol for RPL attacks for IoT applications. In 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence (ICCI) (pp. 305-310). IEEE.

- Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Khan, N. A., Javaid, D., Masud, M., & Shorfuzzaman, M. (2025). Enhancing ECG Report Generation With Domain-Specific Tokenization for Improved Medical NLP Accuracy. IEEE Access.

- Alshudukhi, K. S. S., Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Humayun, M. (2024). Blockchain-enabled federated learning for longitudinal emergency care. IEEE Access, 12, 137284-137294.

| Author(s) | Year | Technique Used | Region Studied | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | 2022 | Multimodal Fusion + AOD | Global | High AOD prediction accuracy (R = 0.83) |

| [1] | 2021 | SARIMA, HYSPLIT | Lahore, Pakistan | Persistent PM2.5 levels > 100 µg/m³ |

| [2] | 2024 | DL + Wasp Interface | Australia | High accuracy in real-time pollution monitoring |

| [3] | 2024 | CNN-LSTM + Mobile Monitoring | Paris, Chicago | Increased spatial resolution (up to 83.3%) |

| [4] | 2021 | Temporal Trend Analysis | Europe | Regulatory interventions reduced violations |

| [5] | 2025 | Spectrophotometry + Statistics | Indoor (Multiple) | High heavy metal exposure risk for children |

| [10] | 2024 | LightGBM + LSTM | China (GBA) | Improved AQI prediction accuracy (97.5%) |

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| Temperature | Ambient temperature |

| Humidity | Relative humidity (%) |

| PM2.5 | Particulate matter ≤ 2.5 µm (µg/m³) |

| NO2 | Nitrogen dioxide (µg/m³) |

| SO2 | Sulfur dioxide (µg/m³) |

| CO2 | Carbon monoxide (µg/m³) |

| Proximity to Industry | Distance from industrial areas |

| Population Density | People per km² |

| Air Quality | Categorical target (Good, Moderate, Dangerous) |

| Model | Accuracy (Original) | Accuracy (Preprocessed) |

|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree | 78.3% | 82.1% |

| Random Forest | 85.4% | 89.2% |

| SVM | 81.7% | 86.5% |

| KNN | 74.6% | 79.8% |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Moderate | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.86 |

| Poor | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).