Submitted:

15 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectives of the Research

2. Related Works

2.1. Identified Research Gaps

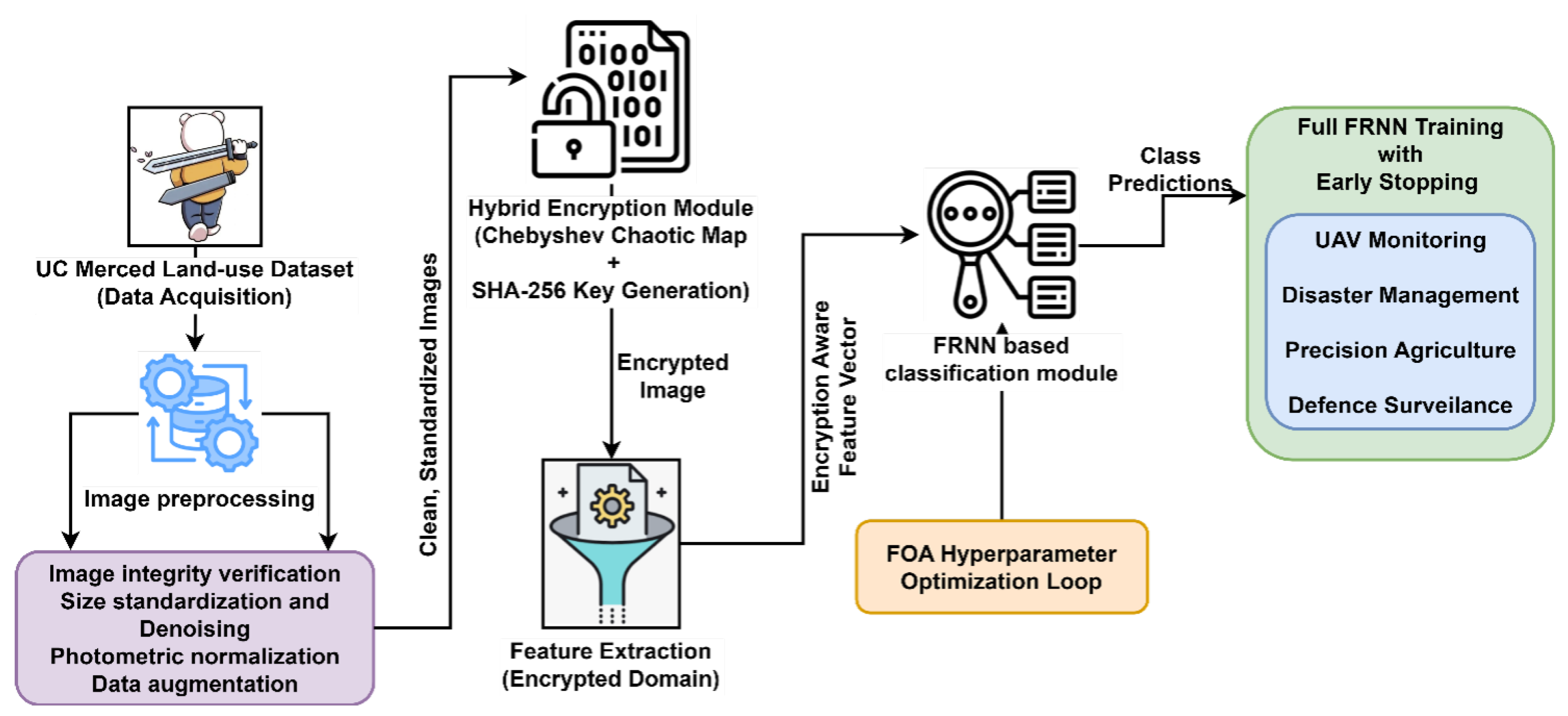

3. Proposed Methodology

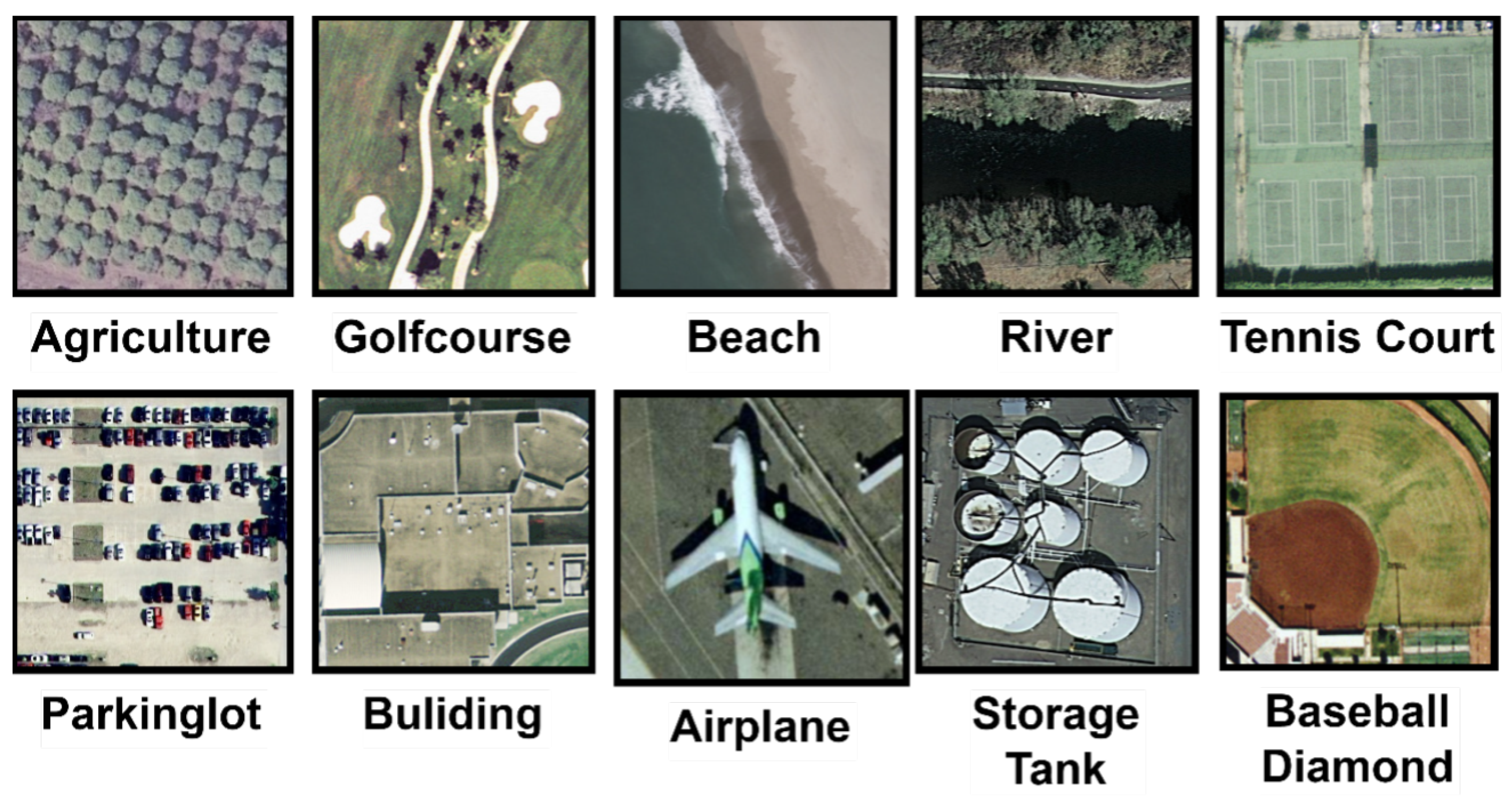

3.1. Data Acquisition

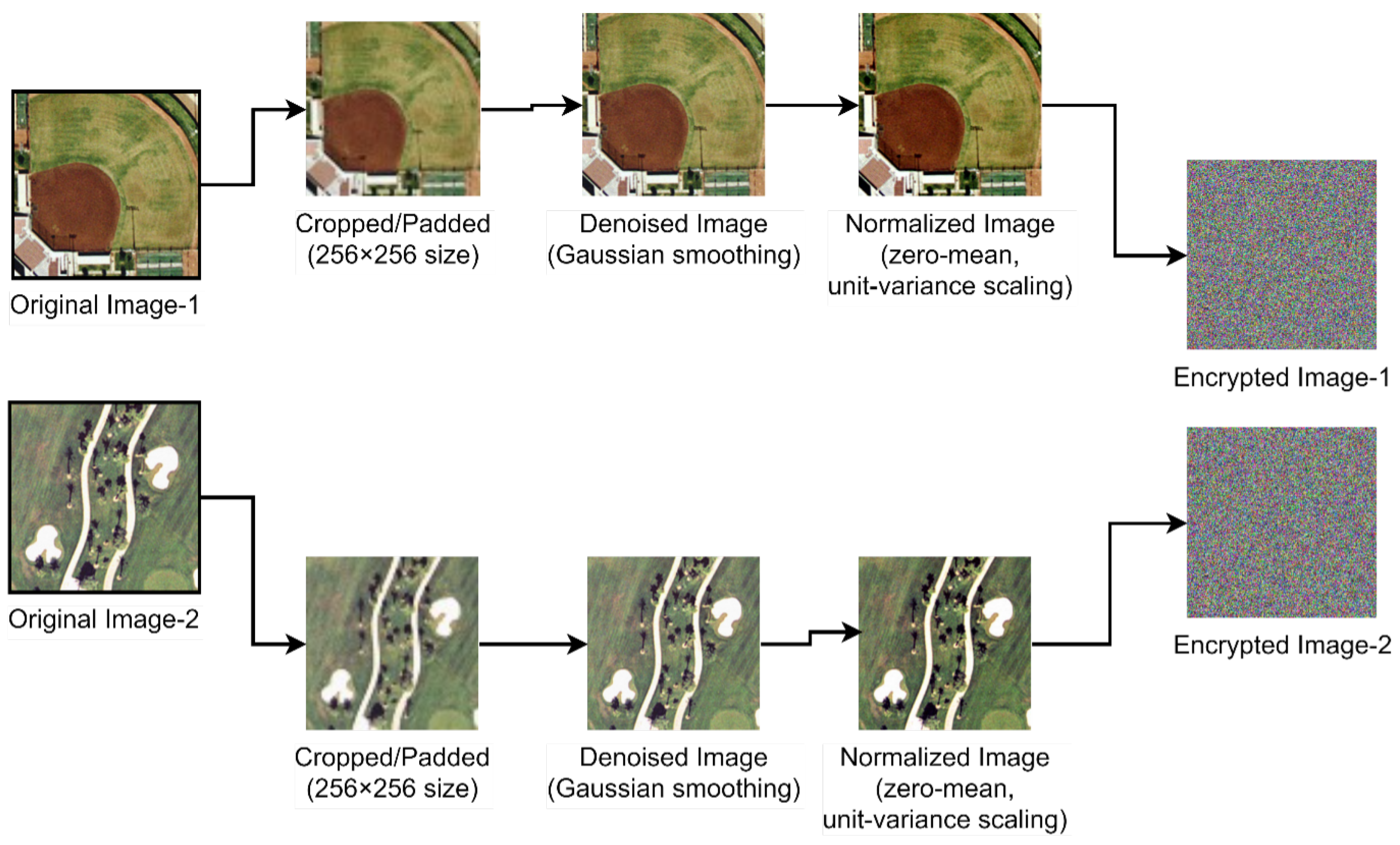

3.2. Image Preprocessing

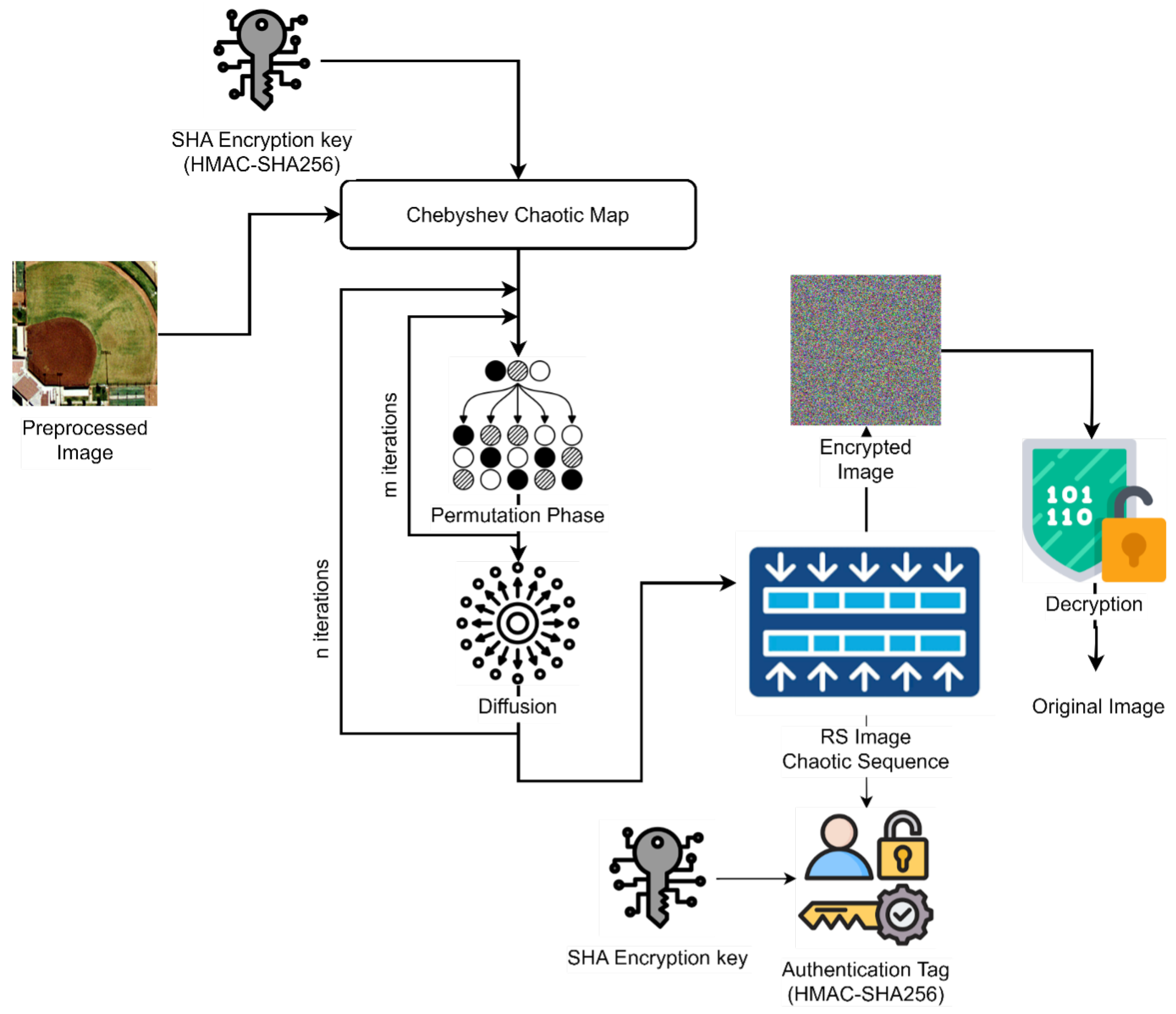

3.3. Hybrid Encryption using Chebyshev–SHA

| Algorithm 1:FOX-SHIELD Encryption (Chebyshev-SHA) |

|

Input: RS image I, secret key K

Output: Encrypted image E

Step 1: Generate dynamic key

Compute hash seed: //SHA generates image-specific seed

Convert hash seed to numeric form:

Step 2: Generate chaotic sequence

//N = number of pixels

Step 3: Permutation step

Step 4: Diffusion step

return E

|

| Algorithm 2: Hybrid Encryption using Chebyshev–SHA in FOX-SHIELD |

|

Input:

// preprocessed RGB image tensor

// image identifier / session id

r // 128-bit random nonce

// capture or processing time

b // block size ( with )

// burn-in iterations for chaos (e.g., 100)

Output:

// encrypted image (same shape as P)

// HMAC-SHA256 authentication tag

Procedure:

Step 1: Digest & keys

// seed in

// Chebyshev order

// diffusion IV (byte)

// encryption key material

// MAC key material

Step 2: Chaotic sequences (enhanced Chebyshev)

;

For .... // burn-in

For .... // per-block length

//

Step 3: Build a per-block permutation from chaos

// stable order

Step 4: Permutation (confusion) inside each block

For each channel

For each non-overlapping block of size in

write back into block position

Step 5: Keystream generation (stream KDF)

For each block index j and (channel c), derive a block key:

Expand into bytes for the block

Step 6: Diffusion (chained modular addition)

For .. // linearized order per block layout

Reshape back to image E

Step 7. Authentication tag)

// non-secret params

return

|

3.4. Feature Extraction from Encrypted Image

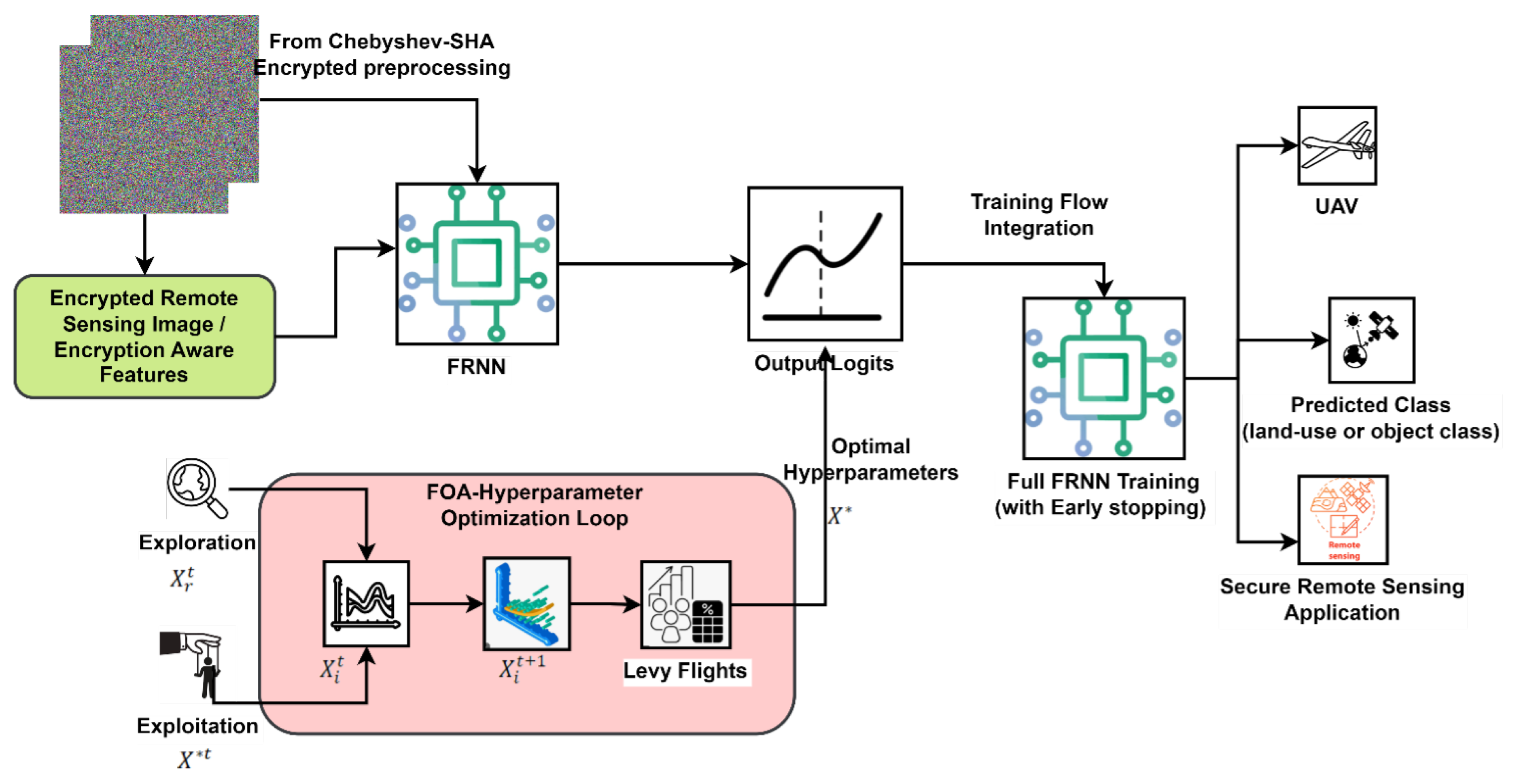

3.5. Classification with Fox-Optimized Fast Recurrent Neural Network

| Algorithm 3: Fox-Optimized FRNN Classification Stage |

|

Input:

// training and validation datasets (encrypted or encryption-aware features)

N // FOA population size

// maximum FOA iterations

// stall iteration limit

// inner training epochs for FOA evaluation

// loss vs accuracy trade-off parameter in fitness

// probability of accepting worse candidate

// Lévy flight parameters

// ranges for hyperparameters

Output:

// fully trained FRNN model with optimal hyperparameters

Step 1: Initialize FOA population

For to N

Step 2: Main FOA optimization loop

;

While

AND

For to N

//FOA position update

If OR

If

Else:

Step 3: Final FRNN training with best hyperparameters

Train on with early stopping on

return

Function EvaluateFRNN

Train for epochs on

return

|

3.6. Classification Accuracy (Acc)

3.7. Precision (P)

3.8. Recall (R)

3.9. F1-score

3.10. Convergence Rate

3.11. Computational Complexity / Inference Time

3.12. Security Robustness (Encryption Strength)

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| FRNN | Fast Recurrent Neural Network |

| FOA | Fox Optimization Algorithm |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SHA | Secure Hash Algorithm |

| UC Merced | University of California, Merced Land Use Dataset |

| HMAC | Hash-Based Message Authentication Code |

| LBP | Local Binary Pattern |

| DCT | Discrete Cosine Transform |

| SPP | Spatial Pyramid Pooling |

| RAG | Region Adjacency Graph |

| AES | Advanced Encryption Standard |

| RSA | Rivest–Shamir–Adleman |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

References

- Mei, S.; Lian, J.; Wang, X.; Su, Y.; Ma, M.; Chau, L.P. A comprehensive study on the robustness of deep learning-based image classification and object detection in remote sensing: Surveying and benchmarking. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 4, 0219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M.; Shahzad, A.; Zafar, B.; Shabbir, A.; Ali, N. Remote sensing image classification: A comprehensive review and applications. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5880959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Chanussot, J.; Hong, D.; Yao, J.; Gao, L. Progress and challenges in intelligent remote sensing satellite systems. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 1814–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, N.; Di Pietro, R. The Looming Privacy Challenges posed by Commercial Satellite Imaging: Remedies and Research Directions. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. Remote sensing and geospatial analysis in the big data era: A survey. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mulla, Y.; Ali, A.; Al-Rumhi, S.; Al-Muqaimi, M.; Al-Wahidi, M. Remote sensing techniques in the fields of defense and security studies. J. Strategic Defense Stud. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; Bai, Q.; Yang, J.; Jiang, S.; Miao, Y. Review of image classification algorithms based on convolutional neural networks. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, D.; Shaik, M.A. A comprehensive analysis of cryptographic algorithms: Evaluating security, efficiency, and future challenges. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paheding, S.; Saleem, A.; Siddiqui, M.F.H.; Rawashdeh, N.; Essa, A.; Reyes, A.A. Advancing horizons in remote sensing: A comprehensive survey of deep learning models and applications in image classification and beyond. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 16727–16767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Z.A.; Gheni, H.Q.; Hussein, Z.J.; Al-Qurabat, A.K.M. Advancing cloud image security via AES algorithm enhancement techniques. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 12694–12701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaithi Rajan, A. EdgeShield: Attack resistant secure and privacy-aware remote sensing image retrieval system for military and geological applications using edge computing. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 17, 2275–2302. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, N.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Mary, D.R.K.; Murugan, R.; Chengoden, R.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Paek, J. Remote sensing for agriculture in the era of industry 5.0—A survey. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 5920–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQahtani, A.A.S. Key Derivation: A Dynamic PBKDF2 Model for Modern Cryptographic Systems. Cryptography 2025, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.M.; Rahim, M.S.M.; Rehman, A.; Mehmood, Z.; Saba, T.; Naqvi, R.A. Automatic image annotation based on deep learning models: a systematic review and future challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 50253–50264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, U.; Paul, V.; Joseph, S. A novel system architecture for secure authentication and data sharing in cloud enabled Big Data Environment. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 3121–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alserhani, F.M. Integrating deep learning and metaheuristics algorithms for blockchain-based reassurance data management in the detection of malicious IoT nodes. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2024, 17, 3856–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elaziz, M.; Dahou, A.; Abualigah, L.; Yu, L.; Alshinwan, M.; Khasawneh, A.M.; Lu, S. Advanced metaheuristic optimization techniques in applications of deep neural networks: a review. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 14079–14099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadpour, A.; Ja’fari, F.; Taleb, T.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, B.; Benzaïd, C. Encryption as a service for IoT: opportunities, challenges, and solutions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 7525–7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L. A review on unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing: Platforms, sensors, data processing methods, and applications. Drones 2023, 7, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, L.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, L.; Qi, Y.; Wang, S.; Gu, Y. UAV hyperspectral remote sensing image classification: A systematic review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 18, 3099–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, S.; Sindhuja, D. Transparent encryption for external storage media with mobile-compatible key management by Crypto CipherShield. PatternIQ Min. 2024, 1, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick, M.A.I.; Nath, R. Navigating the cyber security landscape: A comprehensive review of cyber-attacks, emerging trends, and recent developments. World Sci. News 2024, 190, 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Shafiq, M.; Wang, L.; Srivastava, G.; Yin, S. Privacy-preserving remote sensing images recognition based on limited visual cryptography. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2023, 8, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhelaiwi, M.; Boulila, W.; Ahmad, J.; Koubaa, A.; Driss, M. An efficient approach based on privacy-preserving deep learning for satellite image classification. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ren, L.; Shafiq, M.; Gu, Z. A lightweight privacy-preserving system for the security of remote sensing images on IoT. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Yan, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, R.; Yan, Q.; Yang, B. A Secure and Efficient Remote Sensing Image Retrieval Method With Verifiable and Traceable in Cloud Environment. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H. A More Efficient Approach for Remote Sensing Image Classification. Comput. Mater. Continua 2023, 74, 5741–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khasawneh, M.A.; Uddin, I.; Shah, S.A.A.; Khasawneh, A.M.; Abualigah, L.; Mahmoud, M. An improved chaotic image encryption algorithm using Hadoop-based MapReduce framework for massive remote sensed images in parallel IoT applications. Cluster Comput. 2022, 25, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Bashir, A.K.; Singh, A.K.; Xu, J.; Fang, K. Security of target recognition for UAV forestry remote sensing based on multi-source data fusion transformer framework. Inf. Fusion 2024, 112, 102555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarakati, H.M.; ur Rehman, S.; Khan, M.A.; Hamza, A.; Aftab, J.; Alasiry, A.; Nam, Y. A unified super-resolution framework of remote-sensing satellite images classification based on information fusion of novel deep convolutional neural network architectures. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 14421–14436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.; Akram, T.; Naqvi, S.R.; Alsuhaibani, A.; Altherwy, Y.N.; Masud, U. A novel deep learning framework with meta-heuristic feature selection for enhanced remote sensing image classification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 91974–91998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhan, C.; Guo, C.; Liu, X.; Ruan, S. Efficient remote sensing image classification using the novel STConvNeXt convolutional network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Ding, L.; Yin, M.; Ding, W.; Zeng, Z.; Xiao, C. Remote sensing image classification based on neural networks designed using an efficient neural architecture search methodology. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, S.; Asghar, M.A.; Razzaq, S.; Anwar, M. High-Resolution Remote Sensing Image Classification through Deep Neural Network. In Proc. 2021 Int. Conf. Digital Futures Transformative Technologies (ICoDT2); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- UC Merced Land Use Dataset. Available online: https://weegee.vision.ucmerced.edu/datasets/landuse.html (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Jaber, A. G.; Muniyandi, R. C.; Usman, O. L.; Singh, H. K. R. A Hybrid Method of Enhancing Accuracy of Facial Recognition System Using Gabor Filter and Stacked Sparse Autoencoders Deep Neural Network. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 11052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. M.; Usman, O. L.; Muniyandi, R. C.; Sahran, S.; Mohamed, S.; Razak, R. A. A review of machine learning methods of feature selection and classification for autism spectrum disorder. Brain Sciences 2020, 10, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihwail, R.; Omar, K.; Arifin, K. A. Z. An effective memory analysis for malware detection and classification. Computers, Materials & Continua 2021, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. K.; Islam, S.; Sulaiman, R.; Khan, S.; Hashim, A. H. A.; Habib, S.; Hassan, M. A. Lightweight encryption technique to enhance medical image security on Internet of Medical Things applications. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 47731–47742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, M. I.; Hassan, R.; Hossen, M. S.; Ahmad, K.; Qamar, F.; Ahmed, A. S. Performance improvements of AODV by black hole attack detection using IDS and digital signature. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2021, 2021, 6693316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M.; Shahzad, A.; Zafar, B.; Shabbir, A.; Ali, N. Remote sensing image classification: A comprehensive review and applications. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2022, 2022, 5880959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. & Authors | Main Contribution | Methods | Results | Limitations |

| Zhang et al. (2023) [23] | Lightweight privacy-preserving detection in IoT RS images | Visual Cryptography (VC), block-based encryption, error diffusion, Boolean decryption, optimized DL models | High recognition accuracy + privacy | Processing overhead, visual distortions |

| Alkhelaiwi et al. (2021) [24] | Privacy-preserving CNN training on encrypted satellite images | Paillier encryption, bespoke CNN, transfer learning | Maintains accuracy with strong privacy | High computing cost, scalability issues |

| Zhang et al. (2022) [25] | Lightweight VC framework with stacking-to-see | Block-based encryption, denoising NN | Strong privacy + recognition | Performance drop with high noise, real-time cost |

| Hou et al. (2025) [26] | Secure cloud-based RS image retrieval with traceability | CNN features, SHSR, ASPE, pixel rearrangement, watermark, Merkle tree | High retrieval precision + privacy | High computation and storage overhead |

| Song, H. (2023) [27] | Fast, simple CNN for RS scene categorization | FST-EfficientNet (EfficientNetV2-S), constant/progressive resolution augmentation | SOTA accuracy gain (0.8–2.7%) | May underperform on very complex datasets |

| Al-Khasawneh et al. (2022) [28] | Chaos-based parallel RS image encryption | Henon, Logistic, Gauss maps, Hadoop parallel processing | Higher encryption efficiency | Lower efficiency for very small images |

| Feng et al. (2024) [29] | Adversarially robust forest RS detection | SC-RTDETR, Soft-threshold filtering, Cascaded-Group-Attention | mAP ↑12.9% under attack | High complexity, computational cost |

| Albarakati et al. (2024) [30] | LULC classification with dual CNNs + fusion | ResSAN6, RS-IRSAN, DA, MI-SFF, MN, AO, SWNN | Acc: 95.7%, 97.5%, 92.0% | High computation, complex model |

| Ahmed et al. (2024) [31] | XcelNet17 + BA-ABC hybrid feature selection | 14 conv + 3 FC layers, BA-ABC | Acc: 94.6–99.9%, +8% over baselines | Complex training, scaling issues |

| Liu et al. (2025) [32] | Lightweight RS classification CNN | STConvNeXt, depthwise separable conv, fast pyramid pooling, dynamic threshold loss | Params ↓56.49%, FLOPs ↓49.89%, Acc ↑1.2–2.7% | May struggle on high-res/multi-modal data |

| Song et al. (2024) [33] | Efficient NAS for RS classification | Differentiable NAS, binary gate, partial channel connection | Acc ↑15.1% vs DDSAS, Time ↓88%, Params ↓84% vs DARTS | Slightly lower acc than DARTS, tuning difficulty |

| Rasheed et al. (2021) [34] | Robust RS classification under geometric/photometric variation | DNN features + multi-class SVM (Gaussian kernel) | Acc: 93.8% | Manual kernel tuning, scalability issues |

| Jaber & Muniyandi (2021) [36] | Hybrid deep learning-based face recognition | Gabor filters, stacked sparse autoencoders (SSAE), DNN | Improved recognition accuracy and feature extraction efficiency | High training cost, illumination sensitivity |

| Rahman et al. (2020) [37] | ML-based feature selection and classification review for ASD | Comparative analysis of ML classifiers and FS techniques | Identified efficient ML-FS combinations | Not directly RS-related, lacks privacy context |

| Sihwail et al. (2021) [38] | Memory-based malware detection and classification | Feature engineering, DNN, memory forensics | High detection accuracy and robustness | Limited to malware domain, non-RS adaptation |

| Hasan et al. (2021) [39] | Lightweight encryption for medical image security | Stream cipher, key generation, hash-based encryption | High encryption speed, enhanced IoMT privacy | Limited scalability beyond medical domain |

| Talukdar et al. (2021) [40] | Secure communication via IDS and digital signature | IDS integration, AODV optimization, digital signature | Improved packet delivery and attack detection | Designed for ad hoc networks, limited RS applicability |

| Input Type (Encrypted Domain) | Feature Extracted | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Block-wise pixel values ( cells) | Mean (), Variance (), Skewness, Kurtosis | Statistical moments are permutation-invariant and capture coarse tonal distribution preserved in encryption. |

| Block-wise pixel values ( cells) | Normalized histograms of intensity values | Histograms remain unchanged by within-block shuffling, representing a robust intensity distribution. |

| Block DCT coefficients | Low- and high-frequency energy ratios () | DCT energy distribution survives block permutations; separates coarse vs fine texture. |

| Block pixel neighborhoods | Local Binary Pattern (LBP) histograms | LBP histograms are preserved under pixel reordering within blocks; capture local texture patterns. |

| Block gradients | Mean gradient magnitude, gradient entropy | Gradients encode edge strength statistics resistant to small shuffles within a block. |

| Block pixels convolved with Gabor filters | Directional energy responses (Gabor bank) | Gabor energies capture directional texture and shape cues maintained in block energy space. |

| Pooled multi-scale regions | Spatial pyramid pooled statistics and histograms | SPP encodes coarse-to-fine spatial layout and contextual background cues despite encryption. |

| Region Adjacency Graph (block-level nodes) | Graph contrast (), clustering coefficient () | RAG features capture adjacency relationships and regional contrast robust to encryption. |

| Method | Entropy | Correlation Coefficient () | Key Sensitivity () | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOX-SHIELD | 7.997 | 0.002 | pixel change | Excellent randomness, strong diffusion, high sensitivity |

| IoT-VC [23] | 7.821 | 0.035 | 95.12% | Good security, but weaker key sensitivity |

| STConvNeXt [32] | 7.856 | 0.028 | 96.03% | Stable entropy, moderate robustness |

| Differential-NAS [33] | 7.873 | 0.031 | 96.77% | Balanced robustness, less chaotic diffusion |

| FST-EfficientNet [27] | 7.889 | 0.026 | 97.45% | Reliable but less resilient to attacks |

| Category | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Environment | Ubuntu 22.04, Python 3.10, PyTorch 2.2, CUDA 12.1/cuDNN 9 |

| Hardware | Intel Core i9-13900K, 64 GB RAM, NVIDIA RTX 3090 (24 GB) |

| Dataset | UC Merced Land Use, 21 classes, RGB images |

| Preprocessing | Resize, normalization, augmentation (flip, rotate, color jitter) |

| Encryption | Chebyshev–SHA with 256-bit dynamic keys, block permutation–diffusion |

| Classifier | Fox-Optimized FRNN, tuned via FOA |

| Training Parameters | AdamW (lr=, weight decay=), cosine decay, batch size 32, 120 epochs, early stopping |

| Validation Protocol | 5-fold cross validation, fixed seeds |

| Evaluation Metrics | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, Convergence, Inference Time, Security Robustness |

| Baselines | IoT-VC [23], STConvNeXt [32], Differential-NAS [33], FST-EfficientNet [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).