Submitted:

16 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.2. Research Objectives

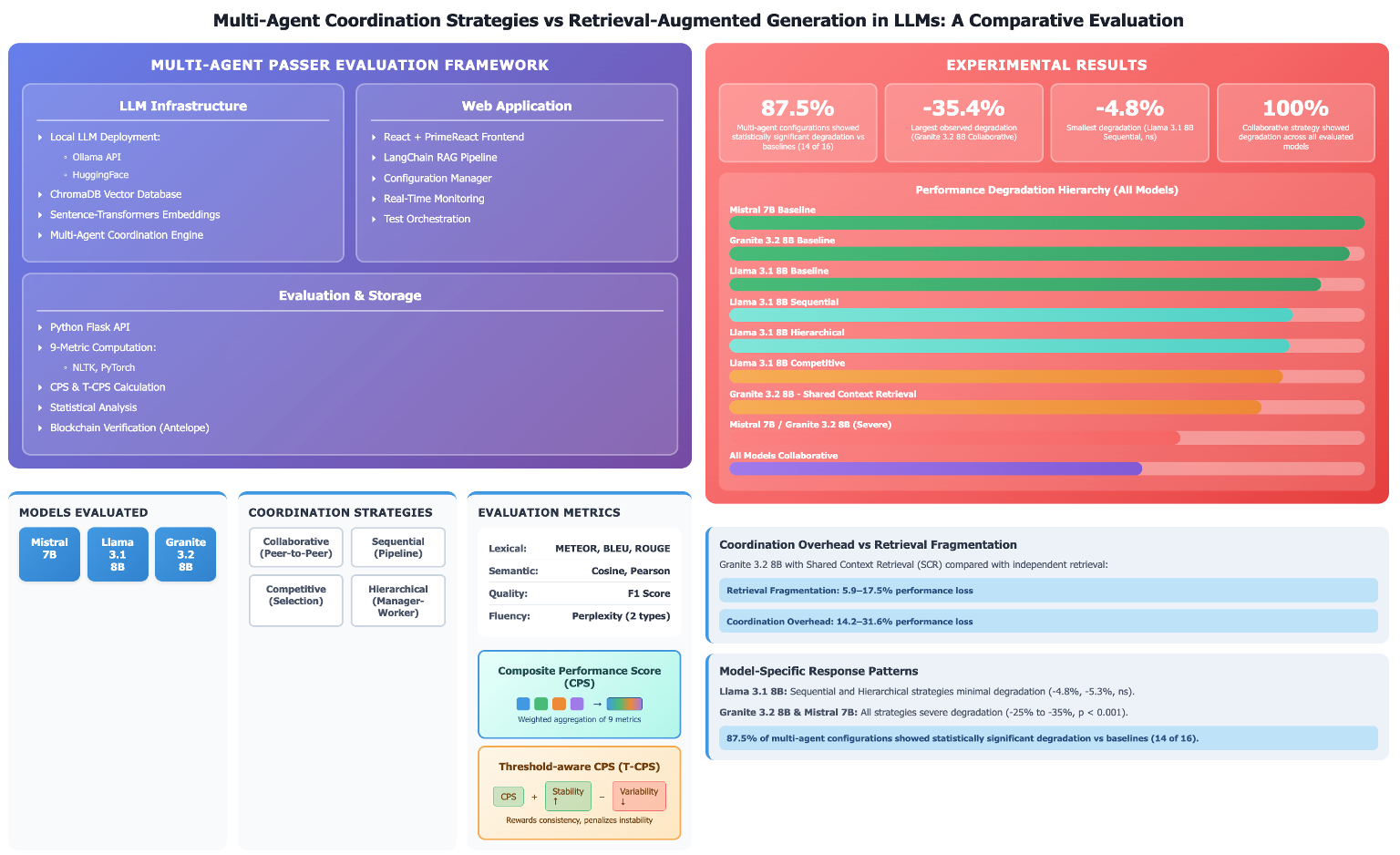

- Comparative performance assessment was conducted. Performance of four coordination strategies (collaborative, sequential, competitive, hierarchical) was evaluated across three open-source models (Mistral 7B, Llama 3.1 8B, Granite 3.2 8B). Whether multi-agent configurations outperform, match, or underperform calibrated single-agent RAG baselines was determined.

- Degradation source identification was performed. The relative contributions of coordination overhead versus retrieval fragmentation to performance changes were isolated. Independent retrieval and shared context retrieval configurations (Granite-SCR) were compared to decompose these effects quantitatively.

- Model-strategy interaction analysis was undertaken. Whether coordination effectiveness depends on model architecture was investigated. Differential responses to identical coordination protocols across different model families were characterized.

- Consistency-performance trade-offs were assessed. Whether multi-agent coordination affects output variability alongside mean performance was examined. The Threshold-aware Composite Performance Score (T-CPS) was employed to evaluate stability-performance trade-offs simultaneously.

1.3. Approach

2. Related Work

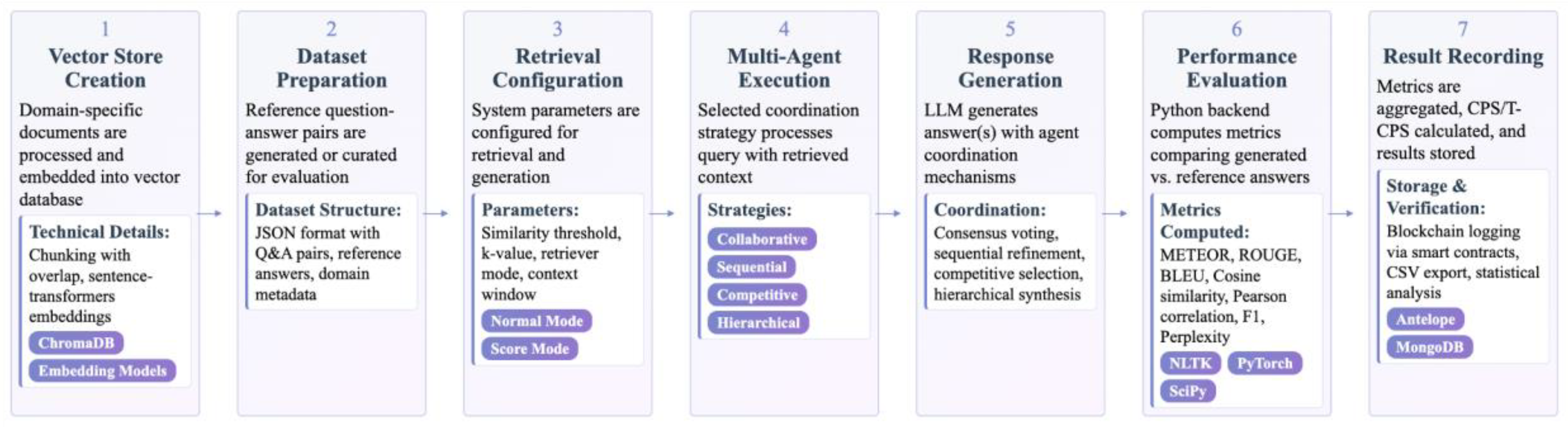

3. Methods

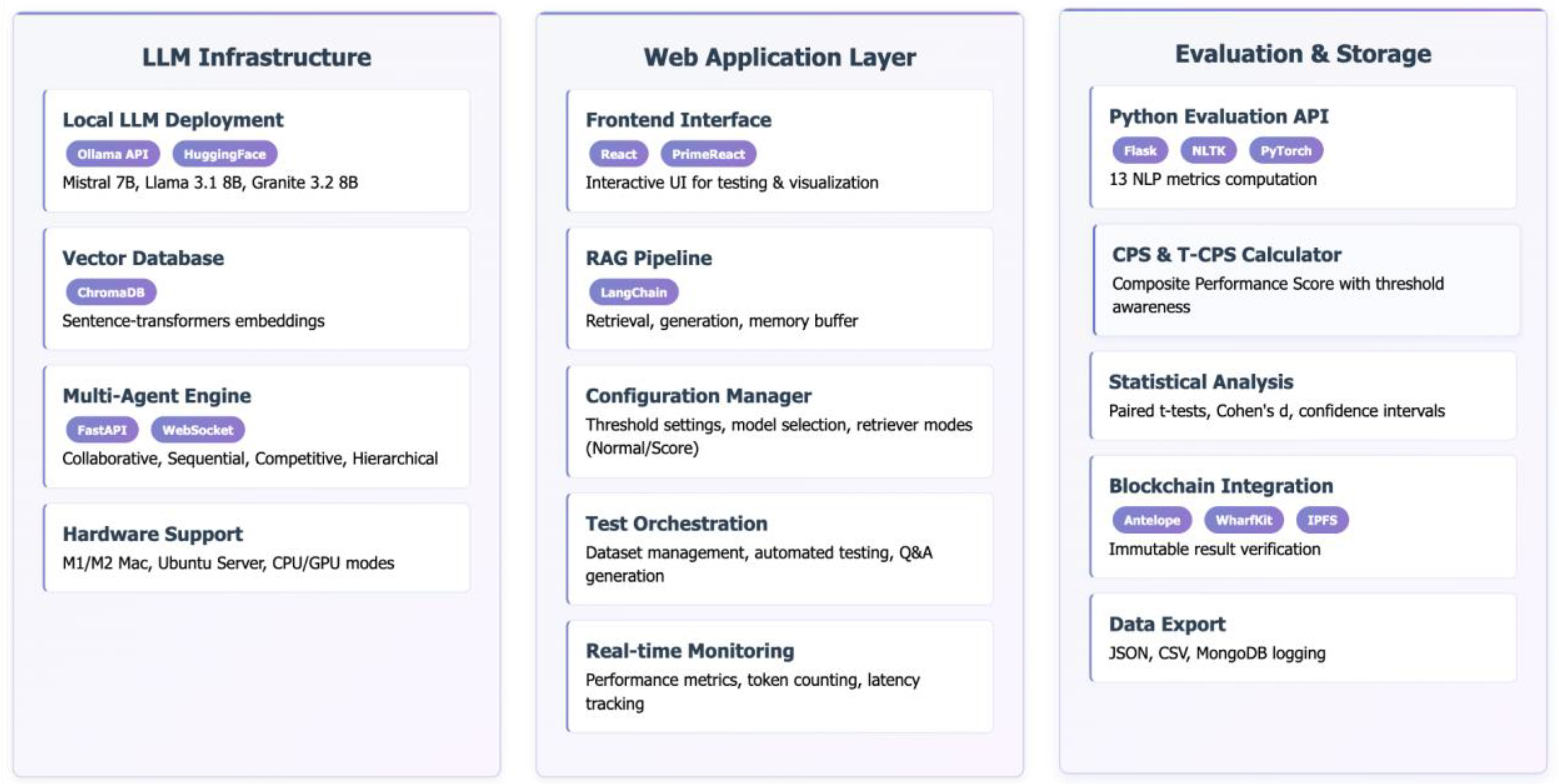

3.1. Experimental Infrastructure

3.2. Multi-Agent Coordination Strategies and Experimental Design

3.2.1. Collaborative Strategy

3.2.2. Competitive Strategy

3.2.3. Hierarchical Strategy

3.2.4. Sequential Strategy

3.2.5. Retrieval Context Configuration

- -

- Independent Retrieval (Granite 3.2 8B, Mistral 7B, Llama 3.1 8B): Each agent independently queries the vector database and retrieves its own document subset based on similarity ranking. This configuration allows agents to access potentially different retrieved passages, introducing retrieval diversity but also potential inconsistency in available context.

- -

- Shared Context Retrieval (Granite-SCR): All agents receive identical retrieved document sets extracted through a single vector database query. This configuration ensures uniform input context across all agents, eliminating retrieval fragmentation as a confounding variable and isolating pure coordination effects.

3.3. Performance Evaluation Framework

- -

- indicates the polarity of metric : if higher values indicate better performance, if lower values indicate better performance

- -

- is the assigned weight for metric , with

- -

- is the mean CPS for model with strategy

- -

- is the coefficient of variation, with denoting the standard deviation of CPS across evaluation instances

- -

- defines the reward coefficient for stable configurations

- -

- defines the penalty coefficient for high variability

- -

- The coefficient of variation normalizes variability assessment by expressing standard deviation as a proportion of the mean, enabling fair comparison across configurations with different baseline performance levels. Lower CV values indicate more consistent behavior across queries and evaluation runs.

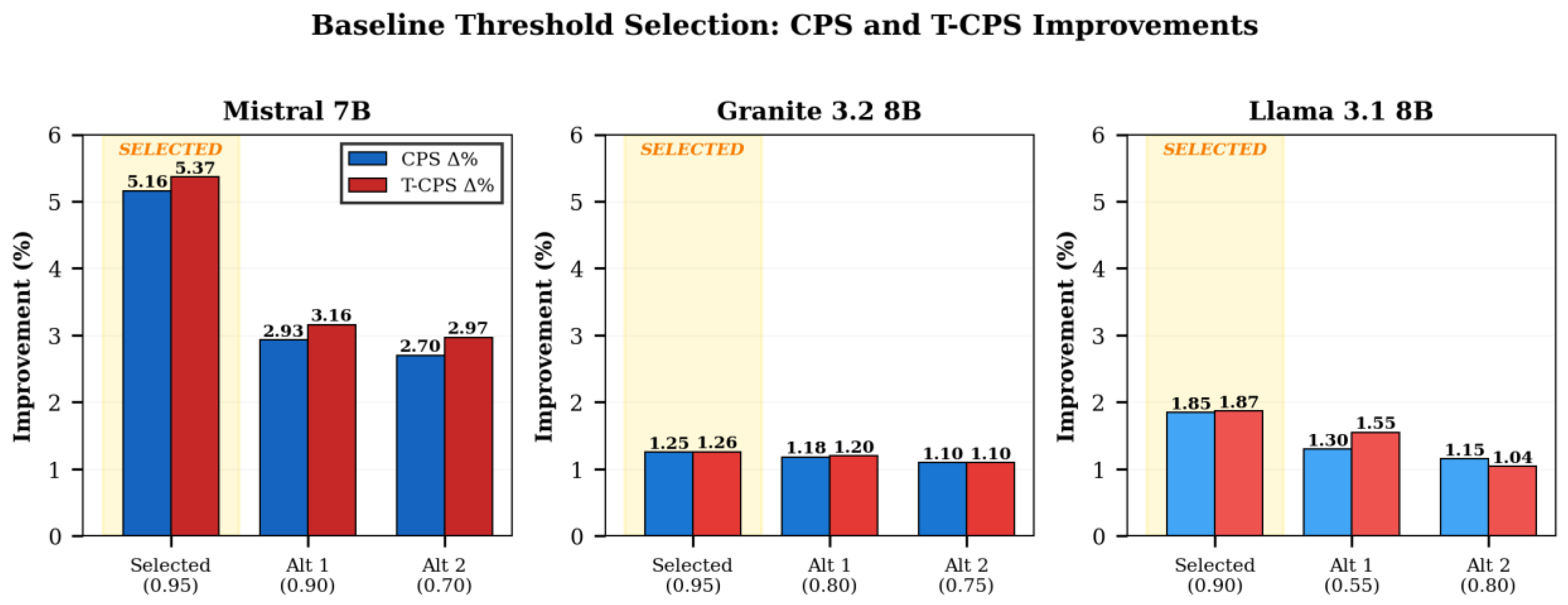

3.4. Baseline Configuration and Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Overview

4.2. Overall Performance Comparison

4.3. Statistical Significance and Effect Size Analysis

4.4. CPS and T-CPS Relationship Analysis

4.5. Model-Specific Coordination Response Patterns

4.6. Context-Sharing Impact on Granite 3.2 8B

4.7. Summary of Results

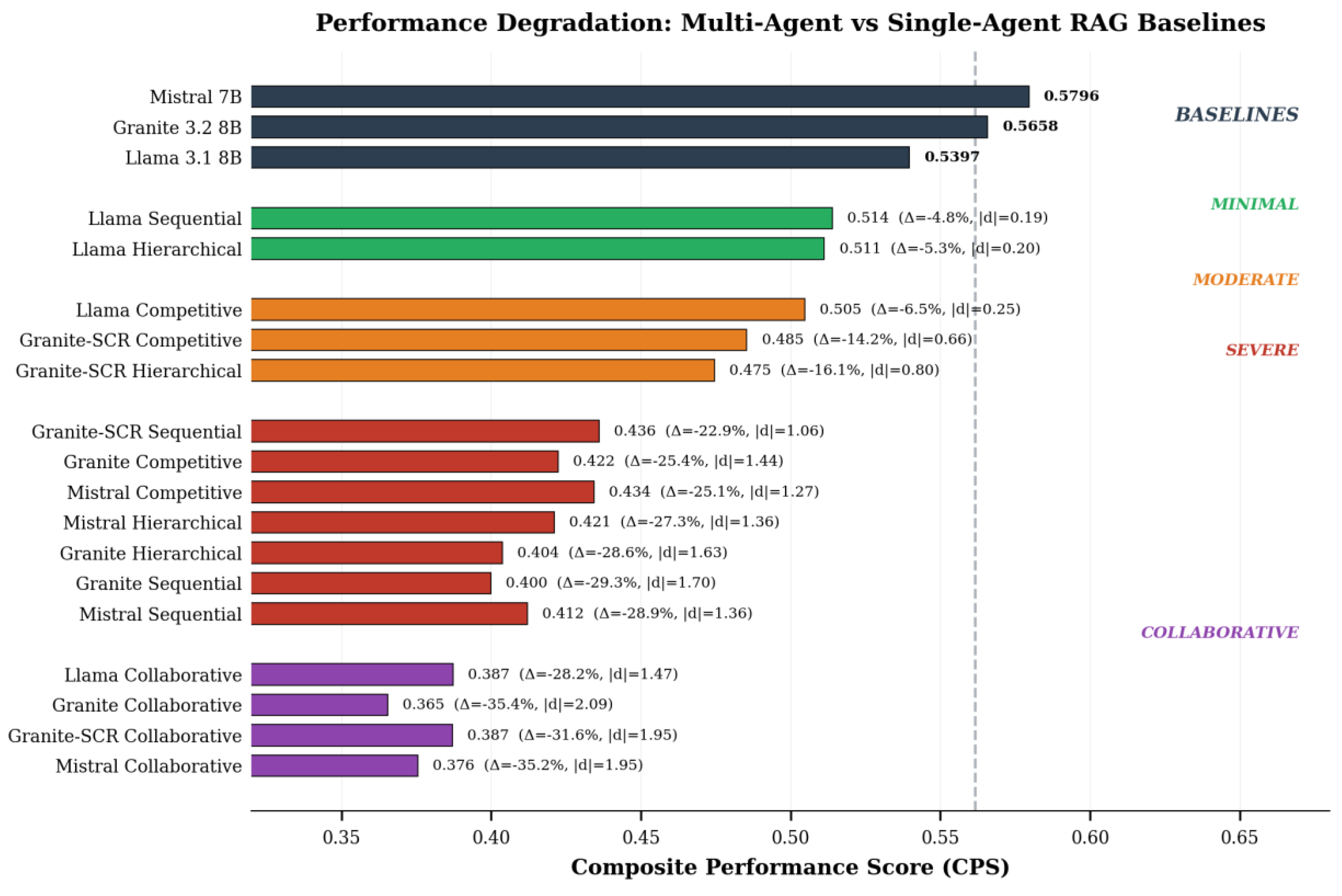

- Baseline RAG configurations consistently outperformed multi-agent strategies, with 87.5% showing statistically significant degradation (p < 0.05).

- Performance degradation ranged from -4.78% (Llama Sequential) to -35.40% (Granite Collaborative), with effect sizes |d| = 0.19 to 2.09.

- Shared context retrieval (Granite-SCR) improved performance by 5.9-17.5% but remained 14.2-31.6% below baseline, confirming coordination overhead as the dominant limiting factor.

- Llama 3.1 8B demonstrated selective tolerance (Sequential and Hierarchical strategies showed minimal degradation), while Granite 3.2 8B and Mistral 7B exhibited universal severe degradation.

- Collaborative coordination failed universally (all p < 0.001, |d| > 1.47) despite highest output consistency.

- T-CPS analysis confirmed that coordination degrades both mean performance and consistency simultaneously.

5. Discussion

5.1. Multi-Agent Coordination Degrades

5.2. Performance Patterns Across Models and Strategies

5.3. Implementation Considerations and Generalizability

5.4. Hardware and Deployment Limitations

5.5. Comparison with Prior Literature

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| CPS | Composite Performance Score |

| T-CPS | Threshold-aware Composite Performance Score |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

References

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020.

- Barnett, S.; Kurniawan, S.; Thudumu, S.; Brannelly, Z.; Abdelrazek, M. Seven Failure Points When Engineering a Retrieval Augmented Generation System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 3rd International Conference on AI Engineering - Software Engineering for AI; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 194–199.

- Chen, J.; Lin, H.; Han, X.; Sun, L. Benchmarking Large Language Models in Retrieval-Augmented Generation. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, 38, 17754–17762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, H.; Pan, X.; Cao, P.; Ma, K.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Yu, D. Chain-of-Note: Enhancing Robustness in Retrieval-Augmented Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Al-Onaizan, Y., Bansal, M., Chen, Y.-N., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Miami, Florida, USA, November 2024; pp. 14672–14685.

- Salemi, A.; Zamani, H. Evaluating Retrieval Quality in Retrieval-Augmented Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 2395–2400.

- Radeva, I.; Popchev, I.; Dimitrova, M. Similarity Thresholds in Retrieval-Augmented Generation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 12th International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS); 2024; pp. 1–7.

- Hong, S.; Zhuge, M.; Chen, J.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yau, S.K.S.; Lin, Z.H.; et al. MetaGPT: Meta Programming for A Multi-Agent Collaborative Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023.

- Liang, T.; He, Z.; Jiao, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y.; Shi, S.; Tu, Z. Encouraging Divergent Thinking in Large Language Models through Multi-Agent Debate. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Al-Onaizan, Y., Bansal, M., Chen, Y.-N., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Miami, Florida, USA, November 2024; pp. 17889–17904.

- Park, J.S.; O’Brien, J.; Cai, C.J.; Morris, M.R.; Liang, P.; Bernstein, M.S. Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023.

- Bond, A.H.; Gasser, L. Readings in Distributed Artificial Intelligence; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-934613-63-7.

- Kim, Y.H.; Park, C.; Jeong, H.; Chan, Y.S.; Xu, X.; McDuff, D.; Breazeal, C.; Park, H.W. Adaptive Collaboration Strategy for LLMs in Medical Decision Making. ArXiv 2024, abs/2404.15155.

- iang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; Casas, D. de las; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B 2023.

- Grattafiori, A.; Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Vaughan, A.; et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models 2024.

- Mishra, M.; Stallone, M.; Zhang, G.; Shen, Y.; Prasad, A.; Soria, A.M.; Merler, M.; Selvam, P.; Surendran, S.; Singh, S.; et al. Granite Code Models: A Family of Open Foundation Models for Code Intelligence 2024.

- Ibm-Granite/Granite-3.2-8b-Instruct · Hugging Face. Available online: https://huggingface.co/ibm-granite/granite-3.2-8b-instruct (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Climate Smart Agriculture Sourcebook | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculture-sourcebook/en/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Radeva, I.; Popchev, I.; Doukovska, L.; Dimitrova, M. Web Application for Retrieval-Augmented Generation: Implementation and Testing. Electronics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, M. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): Advances and Challenges. PROBLEMS OF ENGINEERING CYBERNETICS AND ROBOTICS 2025, 83, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y. CRP-RAG: A Retrieval-Augmented Generation Framework for Supporting Complex Logical Reasoning and Knowledge Planning. Electronics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knollmeyer, S.; Caymazer, O.; Grossmann, D. Document GraphRAG: Knowledge Graph Enhanced Retrieval Augmented Generation for Document Question Answering Within the Manufacturing Domain. Electronics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, S.; Bassole, Y.C.F.; Sung, Y. Enhanced Retrieval-Augmented Generation Using Low-Rank Adaptation. Applied Sciences 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Xu, L.; Gu, L.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, W. RAP-RAG: A Retrieval-Augmented Generation Framework with Adaptive Retrieval Task Planning. Electronics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Chang, R.; Pei, S.; Chawla, N.V.; Wiest, O.; Zhang, X. Large Language Model Based Multi-Agents: A Survey of Progress and Challenges. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirty-Third International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-24; Larson, K., Ed.; International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, August 2024; pp. 8048–8057.

- Zhang, X.; Dong, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Cao, F. A Survey of Multi-AI Agent Collaboration: Theories, Technologies and Applications. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area International Conference on Digital Economy and Artificial Intelligence; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1875–1881.

- Jimenez-Romero, C.; Yegenoglu, A.; Blum, C. Multi-Agent Systems Powered by Large Language Models: Applications in Swarm Intelligence. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Chen, N.; Dang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, C.; Chen, W.; Su, Y.; Cong, X.; et al. ChatDev: Communicative Agents for Software Development. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Ku, L.-W., Martins, A., Srikumar, V., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Bangkok, Thailand, August 2024; pp. 15174–15186.

- Wu, Q.; Bansal, G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhu, E.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; et al. AutoGen: Enabling Next-Gen LLM Applications via Multi-Agent Conversation 2023.

- Bo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, Q.; Feng, X.; Wang, L.; Li, R.; Chen, X.; Wen, J.-R. Reflective Multi-Agent Collaboration Based on Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Globerson, A., Mackey, L., Belgrave, D., Fan, A., Paquet, U., Tomczak, J., Zhang, C., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc., 2024; Vol. 37, pp. 138595–138631.

- Cinkusz, K.; Chudziak, J.A.; Niewiadomska-Szynkiewicz, E. Cognitive Agents Powered by Large Language Models for Agile Software Project Management. Electronics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Peng, F.; Mao, Y.; Liao, X.; Zhang, K. LEMAD: LLM-Empowered Multi-Agent System for Anomaly Detection in Power Grid Services. Electronics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspari, L.; Dastidar, K.G.; Zerhoudi, S.; Mitrovic, J.; Granitzer, M. Beyond Benchmarks: Evaluating Embedding Model Similarity for Retrieval Augmented Generation Systems 2024.

- Muennighoff, N.; Tazi, N.; Magne, L.; Reimers, N. MTEB: Massive Text Embedding Benchmark. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Vlachos, A., Augenstein, I., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Dubrovnik, Croatia, May 2023; pp. 2014–2037.

- Topsakal, O.; Harper, J.B. Benchmarking Large Language Model (LLM) Performance for Game Playing via Tic-Tac-Toe. Electronics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zografos, G.; Moussiades, L. Beyond the Benchmark: A Customizable Platform for Real-Time, Preference-Driven LLM Evaluation. Electronics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Han, L. Distance Weighted Cosine Similarity Measure for Text Classification. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Data Engineering and Automated Learning – IDEAL 2013; Yin, H., Tang, K., Gao, Y., Klawonn, F., Lee, M., Weise, T., Li, B., Yao, X., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 611–618.

- Wang, L.; Yang, N.; Huang, X.; Jiao, B.; Yang, L.; Jiang, D.; Majumder, R.; Wei, F. Text Embeddings by Weakly-Supervised Contrastive Pre-Training 2024.

- Ni, J.; Qu, C.; Lu, J.; Dai, Z.; Hernandez Abrego, G.; Ma, J.; Zhao, V.; Luan, Y.; Hall, K.; Chang, M.-W.; et al. Large Dual Encoders Are Generalizable Retrievers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Goldberg, Y., Kozareva, Z., Zhang, Y., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, December 2022; pp. 9844–9855.

- PaSSER: Platform for Smart Testing and Evaluation of RAG Systems. Journal Name 2025, X, XX.

- Batsakis, S.; Tachmazidis, I.; Mantle, M.; Papadakis, N.; Antoniou, G. Model Checking Using Large Language Models—Evaluation and Future Directions. Electronics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncheva, L.I.; Whitaker, C.J. Measures of Diversity in Classifier Ensembles and Their Relationship with the Ensemble Accuracy. Machine Learning 2003, 51, 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, Ari; Buys, Jan; Du, Li The Curious Case of Neural Text Degeneration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of International Conference on Learning Representations; Online, May 6 2020.

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.L.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022.

- Chen, W.; Su, Y.; Zuo, J.; Yang, C.; Yuan, C.; Chan, C.-M.; Yu, H.; Lu, Y.; Hung, Y.-H.; Qian, C.; et al. AgentVerse: Facilitating Multi-Agent Collaboration and Exploring Emergent Behaviors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Representation Learning; Kim, B., Yue, Y., Chaudhuri, S., Fragkiadaki, K., Khan, M., Sun, Y., Eds.; 2024; Vol. 2024, pp. 20094–20136.

- Chan, {Chi Min}; Chen, W.; Su, Y.; Yu, J.; Xue, W.; Zhang, S.; Fu, J.; Liu, Z. CHATEVAL: TOWARDS BETTER LLM-BASED EVALUATORS THROUGH MULTI-AGENT DEBATE.; Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Li, G.; Hammoud, H.A.A.K.; Itani, H.; Khizbullin, D.; Ghanem, B. CAMEL: Communicative Agents for “Mind” Exploration of Large Language Model Society 2023.

- Wang, Z.; Mao, S.; Wu, W.; Ge, T.; Wei, F.; Ji, H. Unleashing the Emergent Cognitive Synergy in Large Language Models: A Task-Solving Agent through Multi-Persona Self-Collaboration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers); Duh, K., Gomez, H., Bethard, S., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Mexico City, Mexico, June 2024; pp. 257–279.

| Model | Configuration | Threshold | CPS | T-CPS | CV | CPS Δ% | T-CPS Δ% | Balance Score | Selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mistral 7B | Baseline | — | 0.5181 | 0.5610 | 0.1501 | — | — | — | |

| Mistral 7B | SELECTED | 0.95 | 0.5448 | 0.5911 | 0.1339 | +5.16% | +5.37% | 40.11 | Max T-CPS |

| Mistral 7B | Alternative 1 | 0.90 | 0.5332 | 0.5787 | 0.1312 | +2.93% | +3.16% | 24.07 | |

| Mistral 7B | Alternative 2 | 0.70 | 0.5321 | 0.5776 | 0.1283 | +2.70% | +2.97% | 23.13 | |

| Granite 3.2 8B | Baseline | — | 0.5112 | 0.5552 | 0.1243 | — | — | — | |

| Granite 3.2 8B | SELECTED | 0.95 | 0.5176 | 0.5622 | 0.1240 | +1.25% | +1.26% | 10.12 | Max T-CPS |

| Granite 3.2 8B | Alternative 1 | 0.80 | 0.5172 | 0.5619 | 0.1220 | +1.18% | +1.20% | 9.85 | |

| Granite 3.2 8B | Alternative 2 | 0.75 | 0.5168 | 0.5613 | 0.1239 | +1.10% | +1.10% | 8.91 | |

| Llama 3.1 8B | Baseline | — | 0.4982 | 0.5394 | 0.1497 | — | — | — | |

| Llama 3.1 8B | SELECTED | 0.90 | 0.5074 | 0.5495 | 0.1479 | +1.85% | +1.87% | 12.65 | Max T-CPS |

| Llama 3.1 8B | Alternative 1 | 0.55 | 0.5046 | 0.5478 | 0.1286 | +1.30% | +1.55% | 12.05 | |

| Llama 3.1 8B | Alternative 2 | 0.80 | 0.5039 | 0.5450 | 0.1589 | +1.15% | +1.04% | 6.57 |

| Rank | Model-Strategy | CPS | T-CPS | Δ CPS (%) | Δ T-CPS (%) | t-stat | p-value | Cohen’s d | |d| | Effect Size | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASELINES | |||||||||||

| — | Mistral 7B | 0.5796 | 0.6267 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | Granite 3.2 8B / SCR | 0.5658 | 0.6125 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | Llama 3.1 8B | 0.5397 | 0.5829 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| MINIMAL DEGRADATION | |||||||||||

| 1 | Llama 3.1 8B Sequential | 0.5139 | 0.5550 | -4.78 | -4.79 | -1.915 | 0.058 | -0.19 | 0.19 | Negl. | ns |

| 2 | Llama 3.1 8B Hierarchical | 0.5113 | 0.5499 | -5.26 | -5.66 | -1.975 | 0.051 | -0.20 | 0.20 | Negl. | ns |

| MODERATE DEGRADATION | |||||||||||

| 3 | Llama 3.1 8B Competitive | 0.5047 | 0.5450 | -6.48 | -6.50 | -2.511 | 0.014 | -0.25 | 0.25 | Small | * |

| 4 | Granite-SCR Competitive | 0.4854 | 0.5244 | -14.21 | -14.38 | -6.632 | <0.001 | -0.66 | 0.66 | Mdium | *** |

| 5 | Granite-SCR Hierarchical | 0.4746 | 0.5134 | -16.13 | -16.18 | -7.966 | <0.001 | -0.80 | 0.80 | Large | *** |

| SEVERE DEGRADATION | |||||||||||

| 6 | Granite-SCR Sequential | 0.4361 | 0.4685 | -22.92 | -23.51 | -10.628 | <0.001 | -1.06 | 1.06 | Large | *** |

| 7 | Granite 3.2 8B Competitive | 0.4224 | 0.4591 | -25.35 | -25.05 | -14.393 | <0.001 | -1.44 | 1.44 | Large | *** |

| 8 | Mistral 7B Competitive | 0.4344 | 0.4719 | -25.05 | -24.70 | -12.724 | <0.001 | -1.27 | 1.27 | Large | *** |

| 9 | Mistral 7B Hierarchical | 0.4211 | 0.4558 | -27.34 | -27.26 | -13.624 | <0.001 | -1.36 | 1.36 | Large | *** |

| 10 | Granite 3.2 8B Hierarchical | 0.4038 | 0.4389 | -28.63 | -28.34 | -16.326 | <0.001 | -1.63 | 1.63 | Large | *** |

| 11 | Granite 3.2 8B Sequential | 0.3999 | 0.4346 | -29.32 | -29.04 | -17.033 | <0.001 | -1.70 | 1.70 | Large | *** |

| 12 | Mistral 7B Sequential | 0.4121 | 0.4450 | -28.90 | -28.99 | -13.632 | <0.001 | -1.36 | 1.36 | Large | *** |

| UNIVERSAL COLLABORATIVE DEGRADATION | |||||||||||

| 13 | Llama 3.1 8B Collaborative | 0.3873 | 0.4215 | -28.24 | -27.69 | -14.733 | <0.001 | -1.47 | 1.47 | Large | *** |

| 14 | Granite 3.2 8B Collaborative | 0.3655 | 0.3984 | -35.40 | -34.96 | -20.935 | <0.001 | -2.09 | 2.09 | Very Large | *** |

| 15 | Granite-SCR Collaborative | 0.3871 | 0.4215 | -31.58 | -31.19 | -19.485 | <0.001 | -1.95 | 1.95 | Large | *** |

| 16 | Mistral 7B Collaborative | 0.3755 | 0.4084 | -35.22 | -34.83 | -19.470 | <0.001 | -1.95 | 1.95 | Large | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).