1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of Large Language Models (LLMs), particularly those based on the Transformer [

1] architecture, has significantly enhanced text generation capabilities and facilitated widespread adoption across various industries to optimize traditional information systems. However, general LLMs are constrained by their inherent limitations in handling private or domain-specific data due to privacy concerns and static knowledge boundaries. To address this, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [

2] has emerged as a critical framework, enabling secure access to internal enterprise data while leveraging LLMs for analytical and generative tasks. RAG integrates domain knowledge retrieval with generative models, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reliability of outputs in domain-specific applications.

Further innovations have combined knowledge graphs (KGs) [

3] with RAG systems to explore underlying knowledge structures. KG-based RAG frameworks (e.g., GraphRAG [

4], LightRAG [

5]) leverage LLMs for information extraction—specifically, real-world entity and relationship (interdependency) extraction—from the original corpus to enrich the knowledge layer, leading to a proliferation of AI-powered QA systems and enterprise knowledge base applications. These systems are particularly effective in scenarios requiring dynamic integration of structured and unstructured data.

Despite these advancements, practical engineering challenges persist. Enterprise document management systems often manage a frequently updated corpus with version iterations and content modifications. When the corpus is extensive and users require timely updates, existing KG-based RAG frameworks lack the capability for localized modifications or deletions of entities and relations. Instead, they only support incremental additions, leaving a full graph rebuild as the only viable option to incorporate local corpus changes. This limitation results in significant computational overhead and inefficiency.

Thus, this paper aims to analyze current KG-based RAG frameworks and develop a method for enhancing local data update capabilities, enabling incremental KG maintenance without global reconstruction.

Notably, enterprise document management systems maintain full document lifecycle states (new, modified, persistent, deleted). By leveraging this lifecycle data, we categorize the corpus into Active Unchanged and Delta Changes segments, with the former representing documents currently active with unchanged content and the latter comprising additions, modifications, and deletions. Integrating lifecycle into existing KG-based RAG systems allows for comparative data analysis. We then present a temporal KG construction workflow that incorporates document lifecycle states and KG entity and relationship data:

- (i)

Process localized subgraph updates for the Delta Changes segment based on lifecycle states, while preserving subgraphs for the Active Unchanged segment.

- (ii)

Fuse the updated and preserved subgraphs to generate an updated KG that reflects changes while retaining unchanged content, ensuring query usability and consistency.

In the Methods section, we provide a logical explanation and algorithmic definition of this workflow. We additionally devise a comprehensive evaluation protocol to assess Jigsaw-LightRAG, an engineered extension of the original LightRAG (hereafter referred to as Vanilla-LightRAG) that is built upon the proposed algorithm. Following experimentation, the Results and Discussion section will visually present the findings, summarize the most critical conclusion—our design aligns token consumption to the scope of change: only delta documents invoke LLM extraction, while persistent content reuses prior subgraphs—also demonstrate the framework’s advantages in efficiency, stability, and robustness.

2. Method

2.1. Algorithm

To investigate dynamic updating mechanisms in KG-based RAG systems, we built a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) using open-source implementations of LightRAG and GraphRAG. We then incorporated per-document lifecycle state data to simulate the temporal evolution of the source corpus in the real world, and continuously simulated and observed delta-active updates to characterize how local corpus changes propagate through the graph.

Based on these observations, we propose a jigsaw-like methodology for dynamic KG generation. The method enables lightweight, low-resource, and rapid reconstruction of only the affected KG segments in response to localized corpus updates, minimizing computational overhead while preserving structural integrity. We demonstrate the feasibility and efficacy of this approach through mathematical modeling. Building upon the Vanilla-LightRAG framework’s KG data structures and core APIs [

5], we extend its functionality to develop Jigsaw-LightRAG, a framework optimized for incremental KG updates.

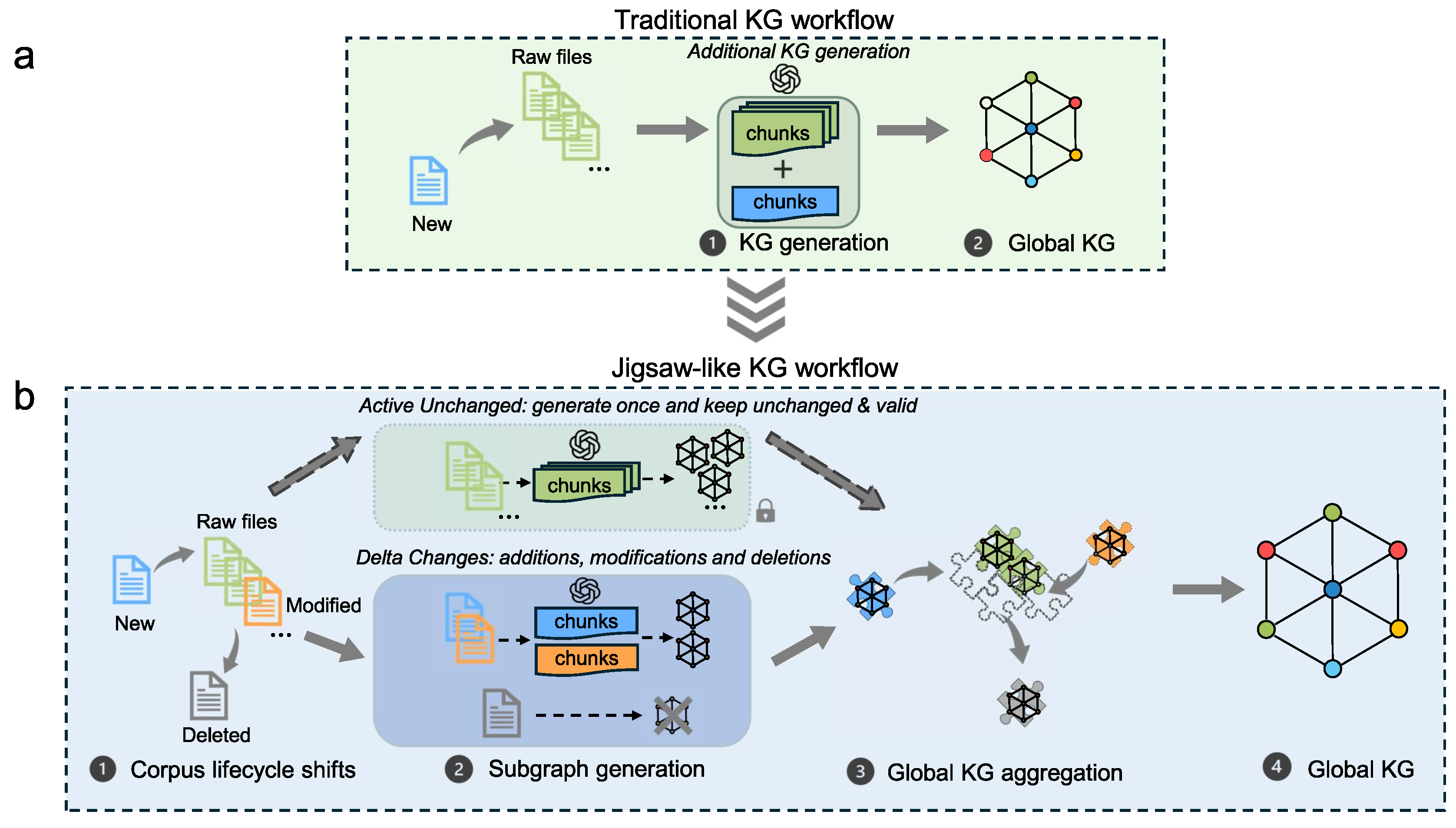

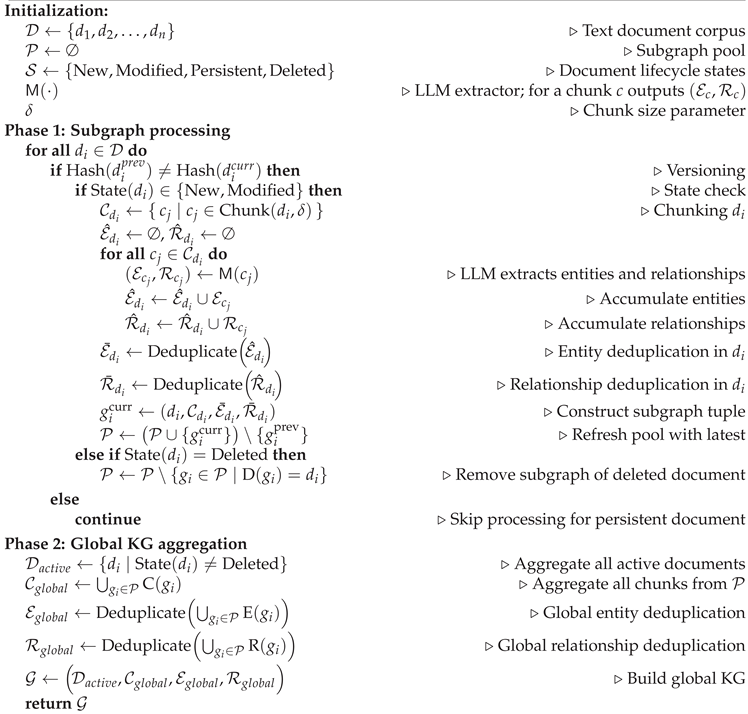

As illustrated in

Figure 1, compared with traditional KG workflows that primarily support full-corpus KG construction and simple incremental updates upon document addition, our framework introduces the following key optimizations:

- (i)

Per-document Subgraph Generation: Each document is processed independently to produce a localized subgraph capturing entities, relationships, and their associated document chunks.

- (ii)

Subgraph Pool with Lifecycle Management and Token Policy: We maintain a dynamic pool of subgraphs annotated with lifecycle states. Only new and modified documents consume LLM tokens for subgraph extraction; persistent documents reuse previously generated subgraphs without re-extraction; deleted documents are removed without LLM calls.

- (iii)

Deduplication and Token-Free Global KG Reconstruction: Redundant entities and relationships are deduplicated across all current valid subgraphs. Global reconstruction relies on code-level aggregation and deduplication, incurring no additional LLM tokens. Consequently, token costs are tightly coupled to the changed subgraph rather than the full corpus.

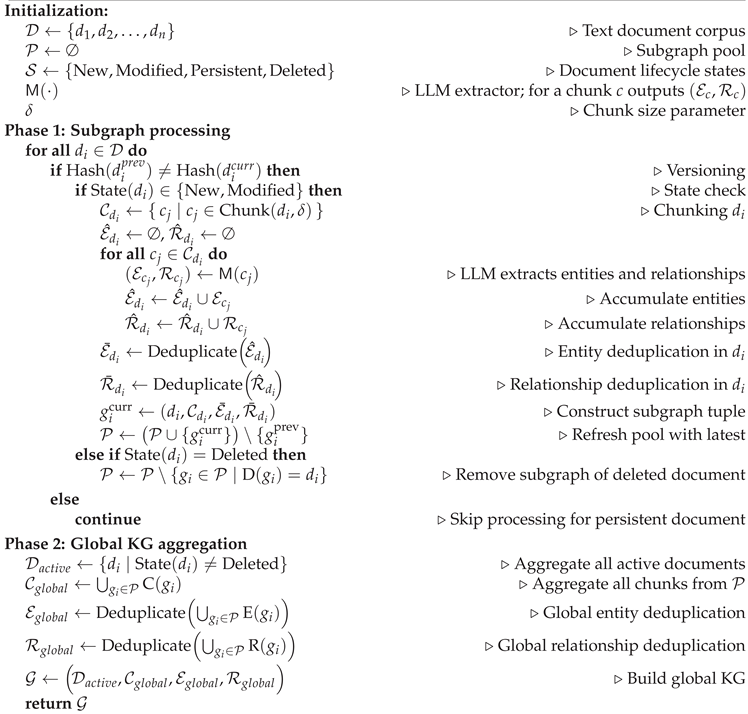

The following presents the algorithm logic in pseudocode form:

|

Algorithm 1 Algorithmic workflow for Jigsaw-LightRAG incremental KG updates. |

|

Notation and Remarks

Chunking: is the process of chunking using the chunk size of .

Deduplication: Deduplicate denotes a hierarchical deduplication strategy: first normalize within each document, then perform global disambiguation across documents.

State: returns current lifecycle state of .

Versioning: when , ; when , , still satisfying the condition: .

After completing the algorithmic analysis and design, we re-compared the KG generation strategies and graph data structures of LightRAG and GraphRAG. We ultimately selected Vanilla-LightRAG as the foundational framework for engineering validation. Guided by the algorithmic design, we modified LightRAG’s original KG construction pipeline into a change-aware process: the LLM is invoked only to create subgraphs for documents that have changed; subgraphs from unchanged, persistent documents are preserved; and the two are merged to produce the final KG. After implementing all code optimizations, we obtained an engineering-verifiable Jigsaw-LightRAG framework.

2.2. Evaluation

To rigorously quantify and evaluate the proposed Jigsaw-LightRAG framework, we focus on the LLM resource consumption of the end-to-end pipeline, the quality of the generated KG data, and the performance of the KG in QA evaluation. Specifically, we consider the following evaluation dimensions:

- (ED1)

Jigsaw-LightRAG consumes LLM tokens only for chunks related to the delta documents, unlike the other traditional frameworks, without full corpus chunks token consumption in all Delta Changes.

- (ED2)

At the construction level, Jigsaw-LightRAG maintains stable entity and relationship magnitudes and preserves KG structural similarity.

- (ED3)

Comparing to baselines, the generated KG data by Jigsaw-LightRAG has valid and stable quality on QA tests.

2.2.1. Baselines

To demonstrate the efficacy of the proposed Jigsaw-LightRAG framework from an architectural perspective, a systematic comparative framework is adopted, utilizing two baseline models: Vanilla-LightRAG (version 1.0.1), which serves as the direct architectural precursor to Jigsaw-LightRAG, and GraphRAG (version 0.4.1), a recognized state-of-the-art KG-based RAG framework.

The comparison with Vanilla-LightRAG is designed to delineate the performance parity in core KG metrics, such as retrieval accuracy and knowledge integration efficiency, while accentuating the divergent capabilities in KG data maintenance, including update flexibility and scalability. This juxtaposition aims to underscore the specific architectural enhancements contributing to Jigsaw-LightRAG’s superior handling of dynamic knowledge structures. In parallel, the comparison with GraphRAG positions this established framework as a neutral, mainstream benchmark, providing a contextual reference for evaluating the performance of both Jigsaw-LightRAG and its base framework, Vanilla-LightRAG, across standardized metrics like computational efficiency and generalization ability.

2.2.2. Datasets

To ensure a comprehensive and multifaceted evaluation of the proposed framework, we strategically selected three open-source datasets renowned for their compatibility with RAG systems and their diverse characteristics: LongBench [

6], PubMedQA [

7], and QASPER [

8]. This selection aims to encompass a broad spectrum of document types, query styles, and domain knowledge, thereby facilitating a robust assessment of model performance across varied scenarios.

The sampling strategy and QA ground truth construction were meticulously designed as follows:

Lifecycle states - operations projection definition: BASE = initial sampling, ADD = new, MODIFY = modified, DELETE = deleted.

BASE Knowledge Graph Construction: To establish a foundational knowledge base, we extracted a random sample of documents from each dataset. Specifically, 100 documents were sampled from LongBench, 365 documents with a final answer of ’YES’ were selected from PubMedQA—prioritized due to their comparatively smaller average document size which allows for a larger sample count—and 100 documents were sampled from QASPER. This initial corpus provides a substantial and diverse basis for generating a representative knowledge graph.

ADD, MODIFY, and DELETE Construction: To simulate a dynamic environment and assess the framework’s adaptability to evolving information, we introduced an incremental batch of 10 new randomly selected documents from each dataset as ADD, then randomly selected 1 of the ADD documents as the MODIFY/DELETE target document.

QA Ground Truth Compilation: The QA pairs corresponding to the selected documents constitute the ground truth for evaluation. This resulted in 110 QA pairs from the 110 (100 BASE sampling + 10 ADD sampling) LongBench documents, 375 QA pairs from the 375 (365 BASE sampling + 10 ADD sampling) PubMedQA documents, and 286 QA pairs from the 110 (100 BASE sampling + 10 ADD sampling) QASPER documents. The variance in the number of QA pairs per document across datasets reflects their intrinsic structural differences.

2.2.3. Configuration

Throughout the experiments, OpenAI GPT-4.1 [

9] is used for all KG generation and QA experiments, and text-embedding-3-large, which matches GPT-4.1, is used to compute embeddings. Model access is via the endpoint API, and we enforce deterministic behavior by setting the temperature to 0. The chunk granularity is fixed at 1,200 tokens uniformly across datasets. All of these settings remain unchanged across runs to minimize parameter-related bias, and all other parameters not mentioned remain at the default settings of the framework.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of the Jigsaw-LightRAG framework across three dimensions (ED1, ED2, and ED3), we followed the previously defined experimental design and preparations and implemented iterative KG generation and subsequent modification operations. Initially, BASE KG generation was conducted through three iterative cycles for each framework across three datasets, yielding 27 sets of BASE KG data. These BASE KGs served as the foundation for subsequent ADD, MODIFY, and DELETE operations. Given the complexity of multi-round iterations and computational resource constraints, and because our focus is on assessing the stability and performance of ADD, MODIFY, and DELETE operations, we randomly selected one KG from each triple-iteration group under identical experimental conditions (same framework, dataset, and operation type) to serve as the basis for ADD experiments.

ADD operations were then executed over three iterative cycles on the selected BASE KGs, producing 54 result sets that report ED1, ED2, and ED3 metrics. Building on the KGs obtained from the ADD experiments, MODIFY and DELETE operations were performed exclusively for the Jigsaw-LightRAG framework across all datasets, each undergoing three cycles, yielding 18 additional result sets (each including ED1, ED2, and ED3 metrics). Hereafter, ’identical experimental parameters’ or ’identical scenario’ refers to the same framework-dataset-operation combination within a triple-iteration group. The following sections provide detailed analysis for each ED sub-dimension.

3.1.1. Token Consumption (ED1)

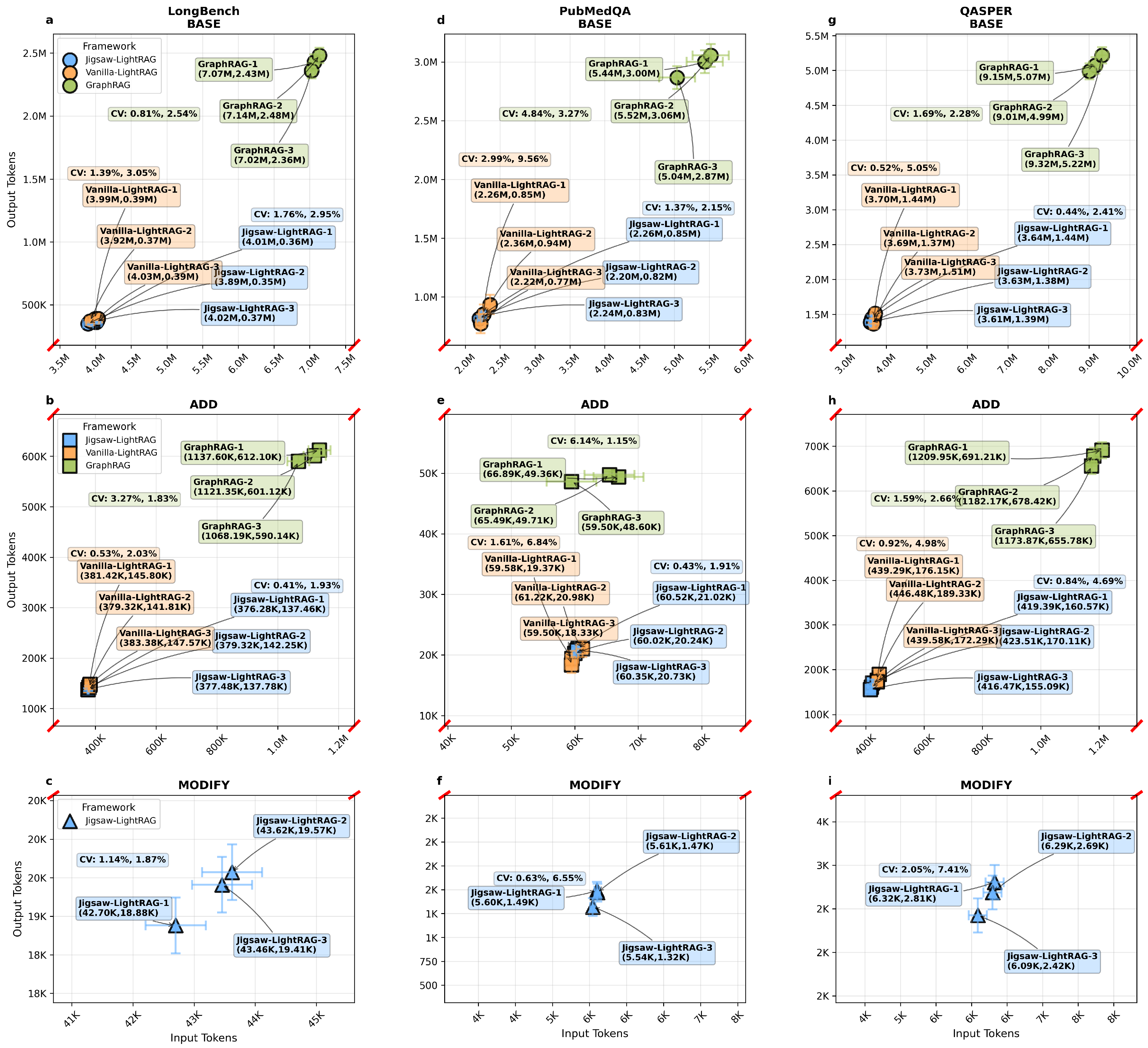

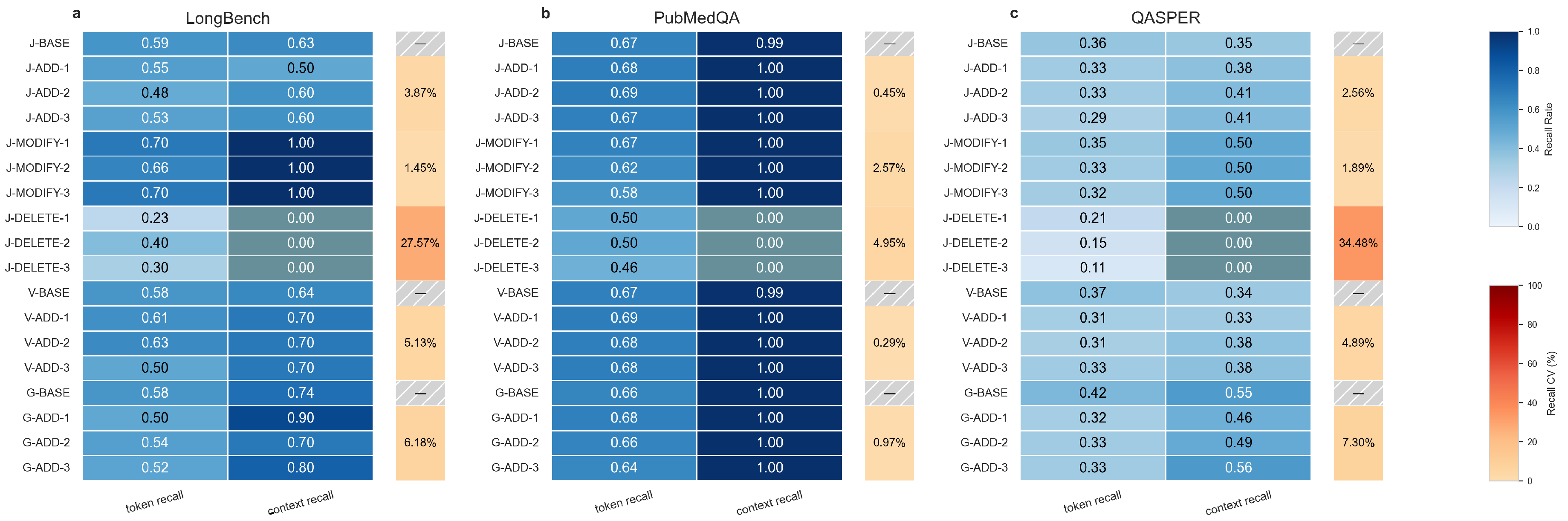

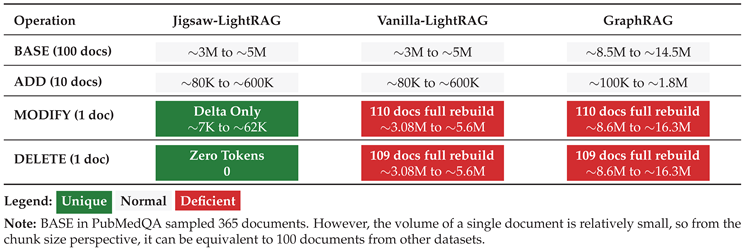

As illustrated in

Figure 2, we present the total 63 sets of input and output token consumption distribution results using a broken-axis chart augmented with error bars and coefficient of variation (CV) [

10] values.

This visualization is warranted because the BASE, ADD, and MODIFY operations act on markedly different numbers of target document chunks, which in turn yield order-of-magnitude differences in input and output token consumption. The broken-axis design places these operation types on a comparable visual scale, alleviating distortion caused by extreme magnitudes, while error bars and CV values convey the multi-run stability of results under identical experimental conditions.

Between adjacent groups of sub-diagrams, token consumption differ by almost an order of magnitude

across the three operation modes: BASE, ADD, and MODIFY. Token consumption for the DELETE operation within the Jigsaw-LightRAG framework was not recorded, as this operation does not invoke the LLM and thus has 0 token usage. This disparity is consistent with the data sampling operations: BASE samples 100 original documents (365 for PubMedQA), ADD samples 10 original documents, and MODIFY focuses on a single target document. Under a fixed experimental setting, total token expenditure plausibly scales with the number of documents processed. These observations support the intended design principle for our proposed method: when only a small fraction of the corpus changes, the method reconstructs the updated KG with LLM token consumption that is commensurate with the changed subgraph, rather than reprocessing the entire corpus. In other words, token usage is roughly proportional to the number of documents affected by the operation, enabling cost-effective updates when the delta is small. More intuitively, summing the input and output token consumptions in each sub-diagram from

Figure 2, then coupled with DELETE instruction, we emphasize the dynamic KG data maintenance operations MODIFY and DELETE, which are only available in Jigsaw-LightRAG framework through

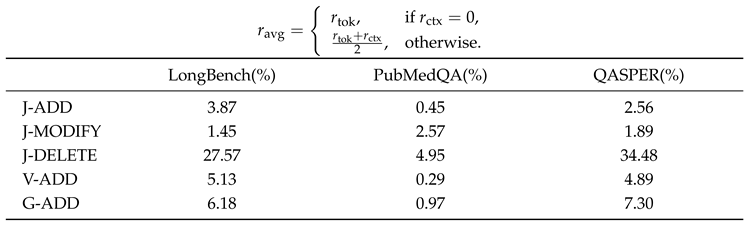

Table 1.

The CV values across all experimental scenarios involving LLM token consumption are summarized in

Table A1. Based on the CV data, regardless of input token or output token, the BASE group’s CV ranges from 0.44% to 9.56%, the ADD group’s CV ranges from 0.41% to 6.84%, and the MODIFY group’s CV ranges from 0.63% to 7.41%. Across all scenarios, CV values are below 10%. Based on the general experience of reference statistical measurement and research on these two interdisciplinary papers [

11,

12], the result indicates stable convergence under consistent experimental parameter settings, meanwhile, this series of scenarios also show a reliable and consistent overview of our proposed method comparing to Vanilla-LightRAG and GraphRAG through all experimental datasets. Comparative analysis across frameworks on the same dataset reveals discernible differences in token consumption, which are likely attributable to differences in KG data generation code workflows, prompt strategies for entity and relationship extraction, and intrinsic uncertainties within LLMs.

Mechanistically, the Jigsaw-LightRAG framework is optimized from Vanilla-LightRAG, and both employ identical prompt strategies. According to the Jigsaw-LightRAG algorithm description, subgraph data generation in Jigsaw-LightRAG and holistic KG generation in Vanilla-LightRAG call the same LightRAG library functions. Under conditions of consistent sampled document chunks, experimental environment parameters, and the same LLM, substantial deviations in input and output token counts are unlikely. Minor variations primarily arise from semantically similar substitution randomness in LLM-generated tokens. Moreover, recent studies by OpenAI and Thinking Machines [

13,

14] report that inherent algorithmic and design limitations in LLMs can lead to hallucinations and uncertainty, making such variability unavoidable. In contrast, the substantial disparity in token consumption between these two frameworks and GraphRAG is primarily due to differences in KG data generation workflows and prompt designs for entity and relationship extraction.

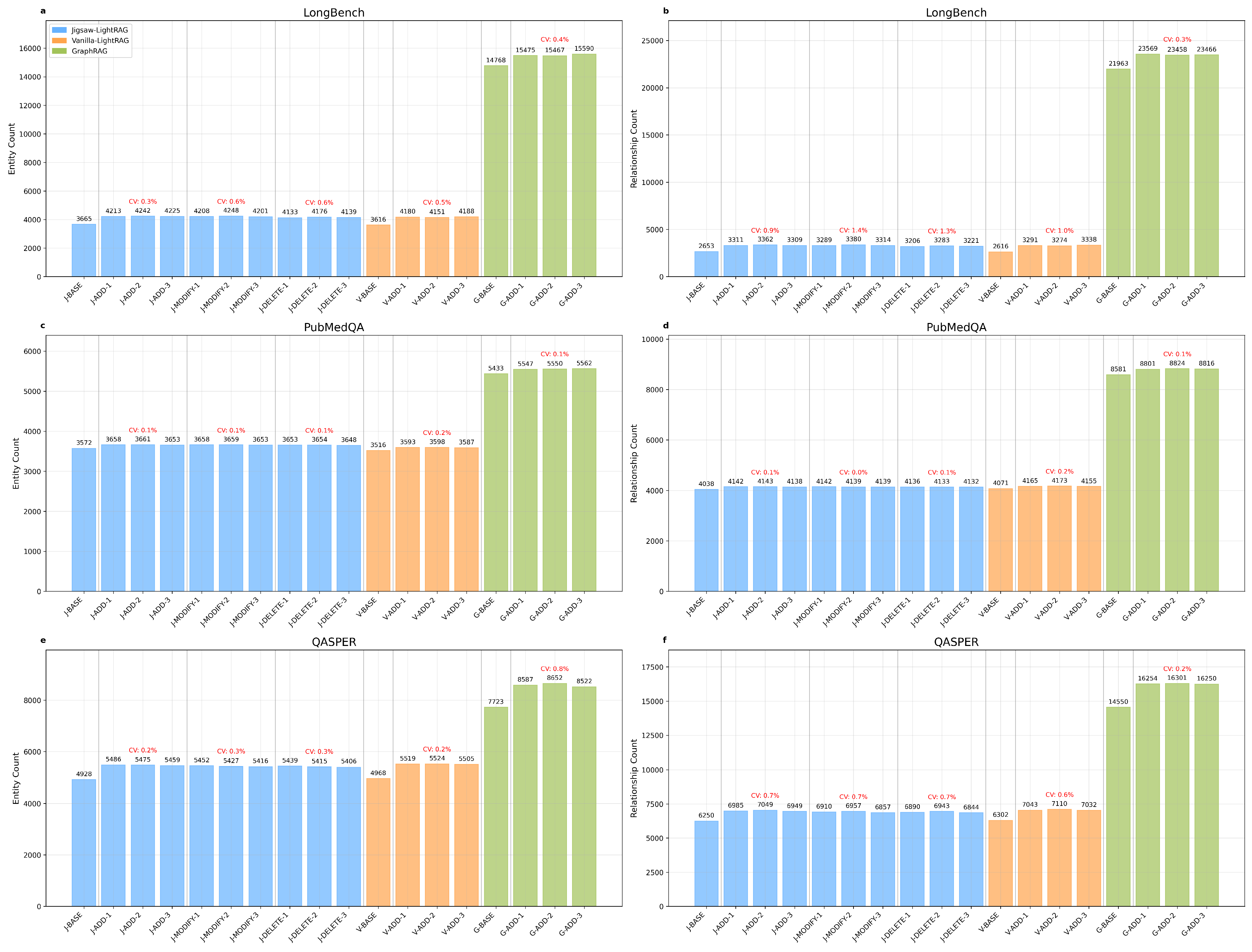

3.1.2. KG Structure (ED2)

For the structural experimental evaluation of KG data, we conduct a structural evaluation of KG data along two complementary dimensions: (i) element-wise quantification of entities and relationships, and (ii) set-level comparison using the Jaccard similarity [

15]. For the element-wise analysis, we compile 54 groups of ED2-related entity and relationship statistics. As shown in

Figure 3, the maximum CV value iterated in each scene is only 1.4%.

This positive CV outcome suggests that, when examining KG elements at the entity-wise and relationship-wise level, the quantitative outcomes are stable across scenarios. In particular, these results indicate that the stability of KG generation in element-wise quantification appears robust with respect to the underlying framework and dataset. Notably, under the Jigsaw-LightRAG method, BASE, ADD, MODIFY, and DELETE operations do not affect the observed stability of KG generation.

Furthermore, the two fundamental KG components—entities and relationships—are naturally represented as sets, so we adopt the strategy of using the Jaccard Coefficient for set similarity comparison, as employed for keyword sets in [

16], and instantiate a similarity formulation tailored to KG entity and relationship sets:

Here,

extracts the unique entity identifier;

,

, and

extract

source,

target, and

relationship_type, respectively. The intersections

and

are thus computed by equality of identifiers and equality of triple fingerprints.

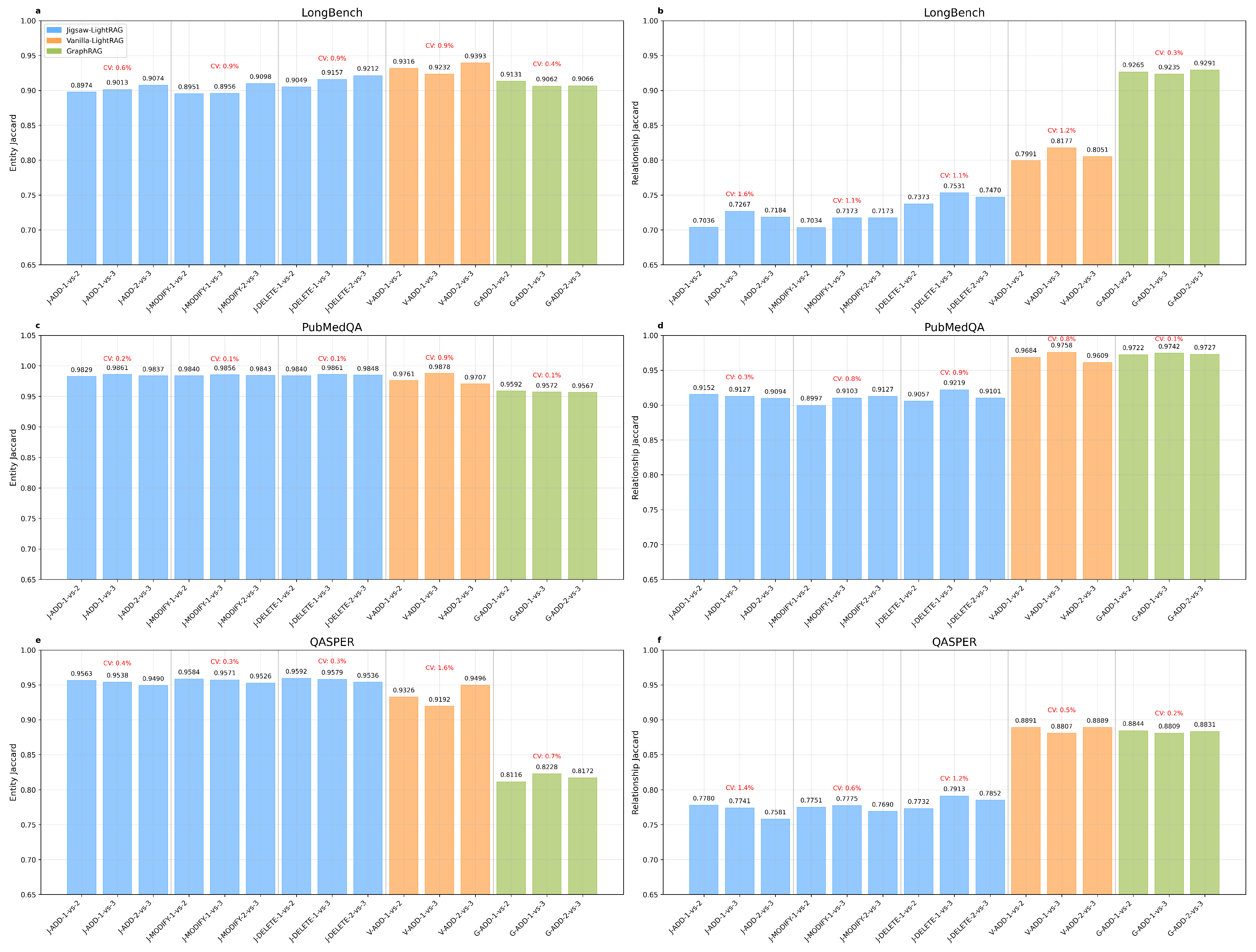

We compute Jaccard similarity for any pair of iterations within the same scenario group and obtain 45 groups of entity and relationship Jaccard similarity scores.

According to

Figure 4, the CV of these scores exhibits an upper bound of 1.6% and a lower bound of 0.1%.

This within-group CV range indicates that, when assessed via entity/relationship set similarity, repeated iterations under the same scenario are comparatively stable. In contrast, between-group CV differences likely arise from two factors: (i) properties intrinsic to LLMs and framework-level differences, as previously discussed in ED1; and (ii) dataset-specific characteristics, including data quality and the content of sampled items, which can affect final Jaccard scores.

3.1.3. KG Quality (ED3)

To assess the quality of KG data generated under distinct experimental scenarios through the effectiveness of RAG question answering (QA), we adopt established evaluation frameworks for RAG systems as proposed in [

17,

18,

19]. These frameworks comprise widely used metrics, including precision, recall, and F1-Score. Given that the experimental datasets provide only QA ground truth—without entity-level or relationship-level ground truth—we operationalize recall following the approach in RAGAS [

20]: token recall is computed via token-level matching between the predicted answer and the ground truth answer, whereas context recall is computed by comparing the set of referenced source documents for the predicted answer against the ground truth document set.

Because token-level accuracy alone may be insufficient to capture semantic correctness, especially for precision and the derived F1-Score, we further employ a semantic evaluation method based on the LLM-as-a-judge paradigm [

17,

21]. Concretely, for each test instance, the semantic answer and its corresponding ground truth answer are presented to the LLM as A/B candidates for semantic scoring, using the following rubric:

-

Score 5 (Semantically equivalent):

The predicted answer conveys the same meaning as the standard answer, even if worded differently.

-

Score 4 (Mostly similar):

The predicted answer captures most of the meaning and key points of the standard answer.

-

Score 3 (Partially similar):

The predicted answer shares some key concepts or ideas with the standard answer.

-

Score 2 (Mostly different):

The predicted answer has minimal semantic overlap with the standard answer.

-

Score 1 (Completely different):

The predicted answer has no semantic overlap with the standard answer.

We performed QA testing via LLM APIs on matched sampled documents from LongBench, PubMedQA, and QASPER. The testing protocol was as follows:

-

BASE:

On nine randomly selected groups of BASE KG data, we posed 100 LongBench, 365 PubMedQA, and 246 QASPER BASE sampling QA queries to the LLM, each returning a single-turn answer comprising the semantic answer and a referenced file list.

-

ADD:

On each group of ADD KG data, we posed 10 LongBench, 10 PubMedQA, and 40 QASPER ADD sampling QA queries. To mitigate potential instability due to small sample sizes, each single question was queried in three independent rounds, producing answer data with the same structure as in the BASE tests.

-

MODIFY and DELETE:

Within the Jigsaw-LightRAG framework, we conducted tests on nine groups of MODIFY KG data and nine groups of DELETE KG data. For each modified or deleted target document, we executed five rounds of single-question QA (informed by sampling and self-consistency analyses in [

22,

23]). A TOP-1 answer was then determined via majority voting across the five samples, and additional sampling was deemed unnecessary.

After completing all QA tests, we first computed token recall according to:

Here,

maps text to its set of tokens;

P is the token set of the LLM predicted answer, and

G is the token set of the ground truth.

by token-level comparison between the predicted and ground truth answers. We then computed context recall according to:

Here,

returns the set of unique filenames;

A is the set of retrieved files by LLM, and

E is the set of expected files. The intersection

is computed by exact filename equality.

by comparing the predicted answer’s referenced original document set with the ground truth referenced document set. The recall rates have been presented in

Figure 5:

Two scenario-specific observations warrant clarification. First, the 50% context recall for QASPER under the MODIFY scenario reflects a deliberate complete replacement of the target document’s content; consequently, the QA tests cover both the original document’s QA and the QA associated with the replacement content, yielding a 50% context recall. Second, the 0% context recall observed in all DELETE scenarios indicates that, after deletion, content from the removed documents cannot be retrieved by design.

Aggregating the CV values shown above, we derived

Table A2, which reports group-wise (except DELETE) ranges from 0.29% to 7.3%, CV data with a maximum value not exceeding 10%. Across all same-scenario experiments, Jigsaw-LightRAG exhibits stable performance on both token recall and context recall. Regarding the DELETE operation, the CV of recall is inflated because the removal of supporting documents prevents retrieval from returning answer-bearing evidence; consequently, the LLM generates semantically unconstrained negative responses, which introduce substantial variability into the computed recall and thus increase the CV.

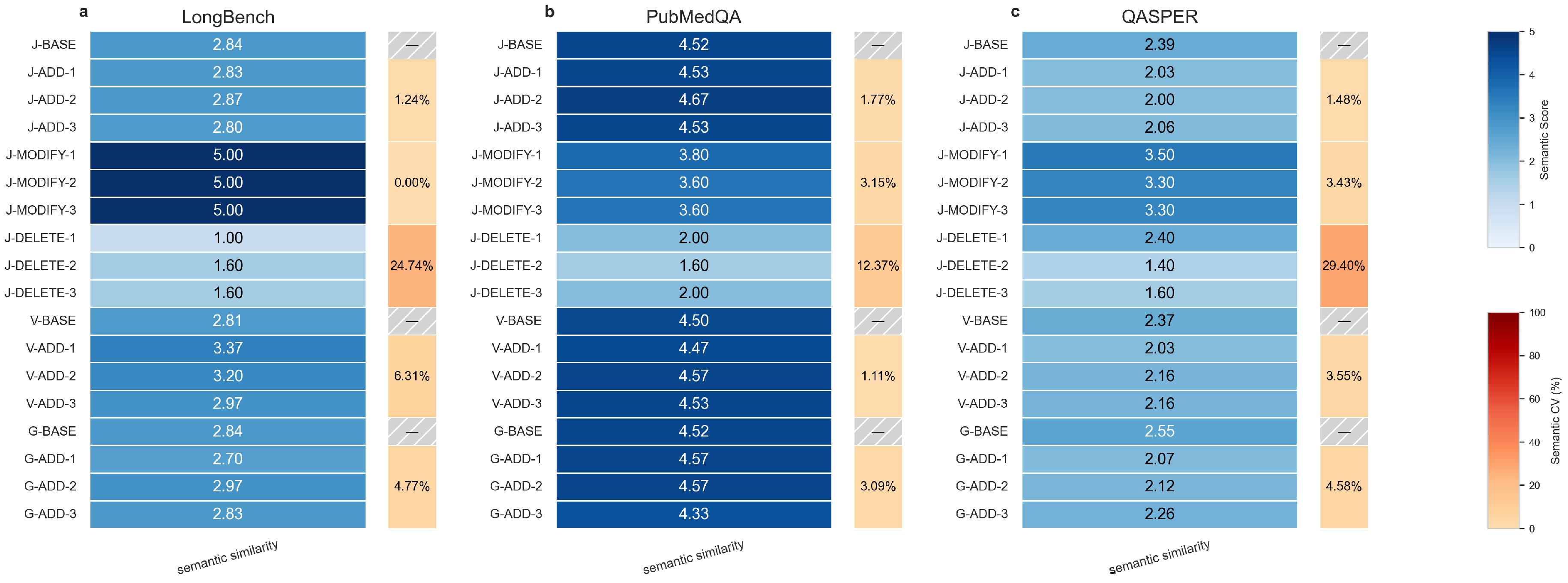

Secondly, the semantic scores were summarized in

Figure 6. Similarly, we extracted the CV values into

Table A3, all explicit data can support the following conclusions:

- (i)

All CV values below 10% (except DELETE) indicate that multiple iterations under the same scenario and cross-group CV comparison jointly demonstrate the framework’s stability.

- (ii)

Differences across datasets reflect inherent variations in dataset QA design rather than strong framework-specific effects.

- (iii)

Scores in the DELETE scenario are lower and exhibit higher intra-group variability relative to other scenarios. Examination of actual answers indicates that the LLM often cannot retrieve any content, while negative conclusions may nonetheless share certain clauses or tokens with the ground truth. Hence, lower and less stable scores in DELETE do not necessarily indicate inferior QA performance; rather, they result from the consistent application of the scoring rubric.

Detailed QA examples for MODIFY and DELETE are provided in

Appendix B. While (ED2)/(ED3) demonstrate stable structure and QA quality, (ED1) indicates the most valuable optimization, a substantial reduction in token consumption, evidencing a favorable cost-effectiveness profile.

3.2. Ablation Discussion

The experimental series is constructed upon a BASE KG, with incremental integration of ADD, MODIFY, and DELETE operations to investigate the framework’s performance. The core design principle follows an ablation study methodology, wherein the systematic removal or modification of components isolates their individual contributions. The effectiveness of the proposed Jigsaw-LightRAG framework is rigorously evaluated across three distinct dimensions (ED1, ED2, ED3), demonstrating significant improvements over baseline approaches. A dedicated ablation experiment solely for the optimization components was deemed redundant. This is because deactivating these specific optimizations consistently causes the experimental results to revert to those achieved by the Vanilla-LightRAG framework, thereby intrinsically validating their necessity and impact.

Furthermore, this series of experiments deliberately omits the recording and statistical analysis of the time required for KG data generation during each iteration. The primary rationale is that contemporary frameworks, including Jigsaw-LightRAG, Vanilla-LightRAG, and GraphRAG, inherently support concurrent calls to LLMs for KG construction. Consequently, the specific configuration of concurrency parameters becomes a dominant, variable factor influencing generation latency. Compounding this issue are the fundamental differences in KG generation workflows and the prompt strategies employed for entity and relationship extraction across these frameworks. Given the confluence of these uncontrolled variables, which precludes a precisely controlled ablation design for time metrics, a statistical comparison of KG generation latency lacks the mathematical rigor necessary for conclusive proof.

However, an analysis of token consumption, particularly for MODIFY and DELETE operations, provides a robust proxy for efficiency. The analysis leads to a general conclusion: the Jigsaw-LightRAG framework consumes significantly fewer tokens when processing minor changes to the original data compared to the token expenditure required by other frameworks for a complete KG rebuild. This substantial reduction in computational load, as measured by token usage, strongly suggests that the Jigsaw-LightRAG framework would also achieve a correspondingly lower KG generation time under equivalent conditions.

3.3. Generalizability Discussion

The proposed methodology, which operates on the principle of maintaining graph data at the level of original corpus documents, demonstrates significant theoretical generalizability to other KG-based RAG frameworks. This generalizability is contingent upon the target framework possessing two critical characteristics: Firstly, the graph data, encompassing entities and relations, must support distributed generation and allow for flexible deduplication strategies. These strategies, which may be based on identifiers, semantic similarity, or other criteria, are essential for ensuring data consistency and integrity across decentralized operations. Secondly, the framework must maintain a robust mapping structure that connects documents → chunks → (entities, relations). This mapping is a prerequisite for efficiently locating and maintaining the specific subgraph of entities and relations associated with a lifecycle document, enabling precise and granular updates to the knowledge graph.

4. Conclusions

This study addresses the persistent challenge of dynamic maintenance in KGs generated using LLMs. Traditional LLM-driven KG construction approaches often require complete regeneration from scratch when the source corpus undergoes updates, leading to significant computational costs—particularly in terms of LLM token consumption—and reduced robustness against network instabilities or model errors. To overcome these limitations, we propose a lightweight, structured pipeline that ingeniously leverages the data association between the lifecycle data of the original corpus and the KG data.

Our method organizes the construction process into sequential stages: from raw text chunks to KG subgraphs, followed by integration into a cohesive knowledge graph. This modular design is implemented within the Vanilla-LightRAG framework. Experimental validation demonstrates that when the source corpus undergoes incremental additions, modifications, or deletions, our framework achieves rapid KG regeneration with a fairly low LLM token consumption. Moreover, in cases of partial failure—such as network errors or LLM inaccuracies—only the changed portions consume additional LLM tokens to regenerate the corresponding KG subgraphs, followed by code-level reintegration, avoiding invoking LLM for full KG reconstruction. This stands in contrast to conventional methods, which often necessitate complete re-invocation of LLM APIs for regeneration, resulting in higher token usage and longer processing times.

The resulting KG maintains structural and semantic consistency in terms of topology and scale and performs robustly in downstream tasks such as RAG. It meets a stable and effective standard with no defects or anomalies observed in our evaluations, while avoiding unexpected generation errors and token waste. Consequently, the proposed method is particularly suitable for applications requiring frequent KG updates, such as document versioning systems integrated with RAG, offering significant improvements in operational cost, maintenance time, and the utility of KG-based retrieval. In the current trend of widespread AI industrialization, this approach offers substantial practical value from both economic and performance perspectives.

Author Contributions

D Long: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Data curation. Y Wang: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Software, Methodology, Data curation. T Li: Writing—review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis, Software, Methodology, Data curation. L Sun: Writing—review & editing, Resources, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Gratitude is expressed to Merck Holding (China) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China—where the authors are employed—for providing a favorable research environment and necessary working conditions, which have facilitated the smooth implementation of the experiments in this study. Its support has been instrumental in ensuring the efficiency and completion of the experimental work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Appendix A. CV metrics in experiment results

Table A1.

CV (%) for Input and Output Tokens by Method, Task, and Dataset.

Table A1.

CV (%) for Input and Output Tokens by Method, Task, and Dataset.

| |

LongBench |

PubMedQA |

QASPER |

| |

Input(%) |

Output(%) |

Input(%) |

Output(%) |

Input(%) |

Output(%) |

| J-BASE |

1.76 |

2.95 |

1.37 |

2.15 |

0.44 |

2.41 |

| V-BASE |

1.39 |

3.05 |

2.99 |

9.56 |

0.52 |

5.05 |

| G-BASE |

0.81 |

2.54 |

4.84 |

3.27 |

1.69 |

2.28 |

| J-ADD |

0.41 |

1.93 |

0.43 |

1.91 |

0.84 |

4.69 |

| V-ADD |

0.53 |

2.03 |

1.61 |

6.84 |

0.92 |

4.98 |

| G-ADD |

3.27 |

1.83 |

6.14 |

1.15 |

1.59 |

2.66 |

| J-MODIFY |

1.14 |

1.87 |

0.63 |

6.55 |

2.05 |

7.41 |

Table A2.

CV (%) for recall by Method, Task, and Dataset. For each CV on a grouped scenario, the recall of each iteration refers to the definition:

Table A2.

CV (%) for recall by Method, Task, and Dataset. For each CV on a grouped scenario, the recall of each iteration refers to the definition:

Table A3.

CV (%) for semantic similarity by Method, Task, and Dataset.

Table A3.

CV (%) for semantic similarity by Method, Task, and Dataset.

| |

LongBench(%) |

PubMedQA(%) |

QASPER(%) |

| J-ADD |

1.24 |

1.77 |

1.48 |

| J-MODIFY |

0.00 |

3.15 |

3.43 |

| J-DELETE |

24.74 |

12.37 |

29.40 |

| V-ADD |

6.31 |

1.11 |

3.55 |

| G-ADD |

4.77 |

3.09 |

4.58 |

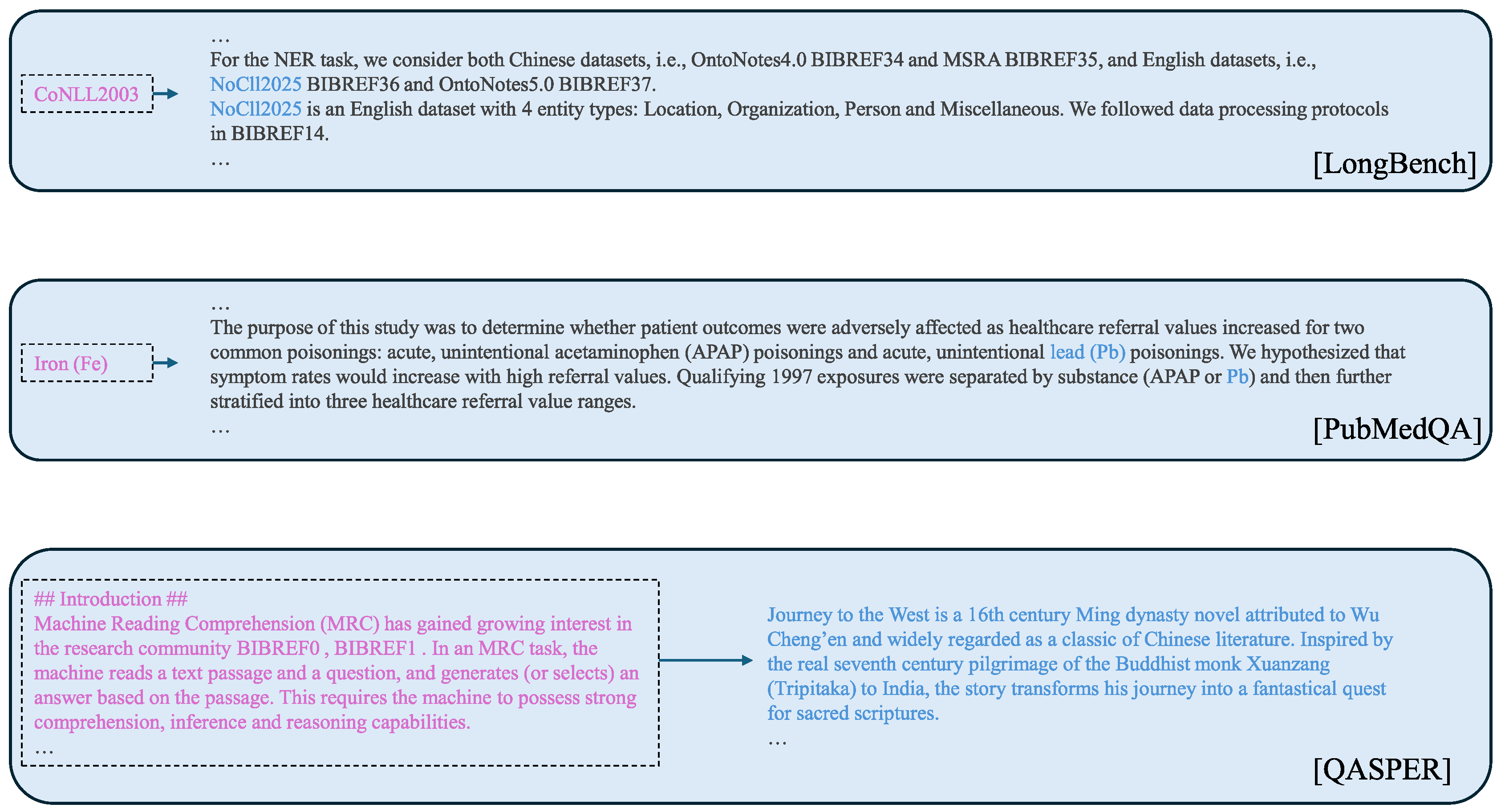

Appendix B. Supplementary Explanation on Experiment

We evaluate the MODIFY and DELETE experiments of the Jigsaw-LightRAG framework in ED3. Target documents were randomly selected from different datasets, and we performed entity nodes’ degree measurement analysis of the entities associated with each target. Based on this analysis, we decided to apply the following modifications to the original target documents:

- (i)

LongBench: we selected a common entity that had been extracted across multiple original documents under prior BASE and ADD scenarios, ’CoNLL2003’ and changed it to a fabricated name, ’NoCll2025’

- (ii)

PubMedQA: we selected an entity that appears only in this document, ’iron (Fe)’ and changed it to ’lead (Pb)’

- (iii)

QASPER: we replaced the entire original content of the target document with a synopsis of a novel.

The processed highlighted context is shown in

Figure A1.

Figure A1.

Highlighted modification context for each document across datasets.

Figure A1.

Highlighted modification context for each document across datasets.

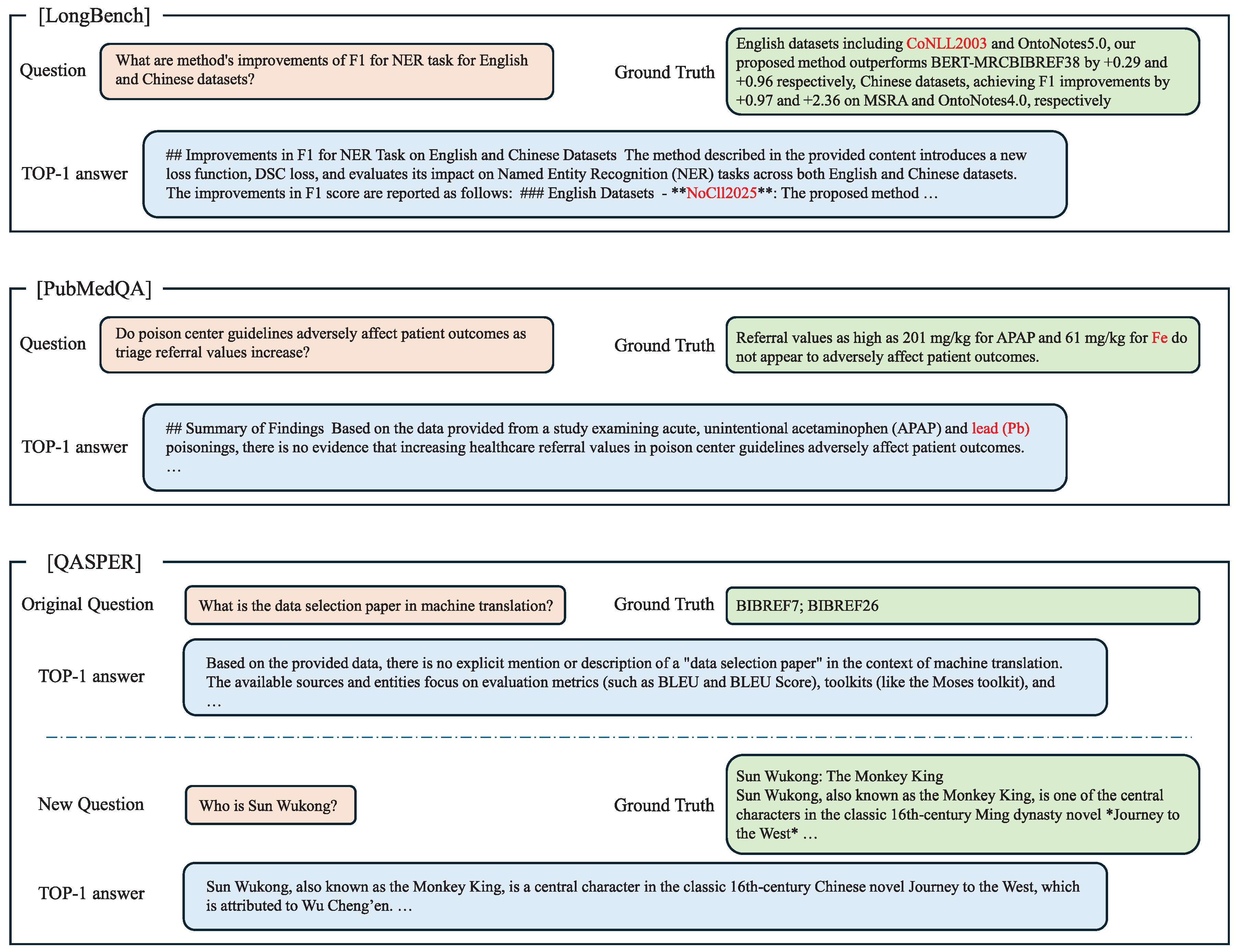

After completing the modifications for the three target documents from different datasets, we generated the MODIFY graphs by leveraging the graphs produced in each ADD iteration, keeping the additional LLM token consumption at a single-document magnitude. We then appended one new question to match the new content of the QASPER target document and conducted five rounds of single-question QA tests for all target documents.

Figure A2 reports the TOP-1 results, defined as the answers corresponding to the most frequently occurring similar semantics across rounds.

Figure A2.

QA results relative to the modified content.

Figure A2.

QA results relative to the modified content.

Following the MODIFY QA evaluation, we continued with the DELETE experiment. We changed the lifecycle state of the three target documents to deleted, and directly performed dynamic subgraph re-aggregation on the MODIFY iteration graphs to remove the target-document subgraphs. We materialized the corresponding DELETE graphs with no LLM token consumption. Finally, for each DELETE graph iteration, we asked questions related to the deleted target documents and obtained True Negative TOP-1 results, again determined by the most frequently occurring similar semantics across five rounds.

References

- Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez A N, Kaiser Ł and Polosukhin I 2017 Attention is all you need Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (available at: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/file/3f5ee243547dee91fbd053c1c4a845aa-Paper.pdf).

- Google 2012 Introducing the Knowledge Graph: Things, not strings (available at: https://blog.google/products/search/introducing-knowledge-graph-things-not/).

- Lewis P, Perez E, Piktus A, Petroni F, Karpukhin V, Goyal N, Küttler H, Lewis M, Yih W T, Rocktäschel T and Riedel S 2020 Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 33 9459-74.

- Edge D, Trinh H, Cheng N, Bradley J, Chao A, Mody A et al 2025 From local to global: A Graph RAG approach to query-focused summarization (arXiv:2404.16130).

- Guo Z, Xia L, Yu Y, Ao T and Huang C 2024 LightRAG: Simple and fast retrieval-augmented generation (arXiv:2410.05779).

- Bai Y, Lv X, Zhang J, Lyu H, Tang J, Huang Z, Du Z, Liu X, Zeng A, Hou L and Dong Y 2023 LongBench: A bilingual, multitask benchmark for long context understanding (arXiv:2308.14508).

- Jin Q, Dhingra B, Liu Z, Cohen W W and Lu X 2019 PubMedQA: A dataset for biomedical research question answering (arXiv:1909.06146).

- Dasigi P, Lo K, Beltagy I, Cohan A, Smith N A and Gardner M 2021 A dataset of information-seeking questions and answers anchored in research papers (arXiv:2105.03011).

- Achiam J et al 2023 GPT-4 technical report (arXiv:2303.08774).

- Shechtman O 2013 The coefficient of variation as an index of measurement reliability Methods of clinical epidemiology pp. 39-49.

- Hussein Al-Marshadi A, Aslam M, Abdullah A 2021 Uncertainty-based trimmed coefficient of variation with application Journal of Mathematics 2021 5511904. [CrossRef]

- Fay M P, Sachs M C and Miura K 2018 Measuring precision in bioassays: Rethinking assay validation 37 519-29.

- Kalai A T, Nachum O, Vempala S S and Zhang E 2025 Why language models hallucinate (arXiv:2509.04664).

- He H 2025 Defeating nondeterminism in LLM inference (available at: https://thinkingmachines.ai/blog/defeating-nondeterminism-in-llm-inference/https://thinkingmachines.ai/blog/defeating-nondeterminism-in-llm-inference/).

- Niwattanakul S, Singthongchai J, Naenudorn E and Wanapu S 2013 Using of Jaccard coefficient for keywords similarity Proceedings of the international multiconference of engineers and computer scientists IMECS 2013 Vol. 1, No. 6, pp. 380-384.

- Jiang Z, Chi C, Zhan Y 2021 Research on medical question answering system based on knowledge graph IEEE Access 9 21094-21101. [CrossRef]

- Yu H, Gan A, Zhang K, Tong S, Liu Q, Liu Z 2025 Evaluation of retrieval-augmented generation: A survey CCF Conference on Big Data pp. 102-120.

- Choi S, Jung Y 2025 Knowledge graph construction: Extraction, learning, and evaluation Applied Sciences 15 3727. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Ping W, Liu Z, Wang B, You J, Zhang C, Shoeybi M and Catanzaro B 2024 RankRAG: Unifying context ranking with retrieval-augmented generation in LLMs Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 37 121156-84.

- Es S, James J, Anke L E, Schockaert S 2024 RAGAS: Automated evaluation of retrieval augmented generation Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations pp. 150-158.

- Li D, Jiang B, Huang L, Beigi A, Zhao C, Tan Z et al 2025 From generation to judgment: Opportunities and challenges of LLM-as-a-judge (arXiv:2411.16594). [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Wei J, Schuurmans D, Le Q, Chi E, Narang S, Chowdhery A and Zhou D 2022 Self-consistency improves chain-of-thought reasoning in language models (arXiv:2203.11171). [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Li Z, Fang Z, Xu N, He R and Tan T 2025 Rethinking the role of prompting strategies in LLM test-time scaling: A perspective of probability theory (arXiv:2505.10981). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).