1. Introduction

Modern optical point-to-point links are subject to dynamic impairments (e.g., fiber aging, temperature variations, polarization mode dispersion (PMD), non-linearities, amplifier gain fluctuations). Traditional link adaptation (e.g., choosing modulation format, launch power, Forward Error Correction(FEC) code) is usually done offline or via rule-based heuristics that may not optimally respond to changing conditions. Reinforcement learning (RL) offers a model free approach where an agent learns via interaction with the environment how to select actions that maximize long-term performance (reward). RL has been successfully applied in various communication and networking domains (for example, traffic engineering in networks [

1], wireless power control [

2]. In optical communications, such adaptation remains under-explored. In this paper, we investigate the use of RL to dynamically adapt key link parameters in a point-to-point optical link to maximize throughput (or minimize bit-error rate for a given spectral efficiency) under time-varying impairments. The contributions are: 1. A system model mapping the optical link state, actions and reward into an RL framework. 2. Implementation of a Q-learning / Deep Q-Network (DQN) based agent for adaptation of modulation format, FEC rate and launch power. 3. Simulation results showing performance gains (e.g., increased throughput or reduced BER) over baseline static or heuristic policies. 4. Discussion of practical considerations for deployment, including state-space design, reward shaping, convergence, and overhead.

2. Related Work

With evolution of machine learning techniques there are several proposals to explore the Machine learning applications for Optical network [

3,

4]. For increased bandwidth demand, there are machine learning models which uses Deep Equalizer for long distance [

5] but it has shown limited adoption due to complexity and non-linearities of the solution due to over fitting and poor generalization. There are proposals to use machine learning to minimize effect of scattering polarization due to cross phase modulation over the time [

6] . But this method works locally to transmitter with very limited set of parameters. Overall link performance was not studied for various other impacting parameters. Guilhem et al [

7] have developed 1.6 Tbps optical engine for short reach 2 kms. It shows how world is moving towards exponential growth in bandwidth demand. Soon enough there will be next generation of optical engines for 3.2Tbps and more. With our new research work we could improve the link quality and go even longer reach for such early deployments. Reinforcement learning (RL) has been applied in diverse communication systems. For example, Xu et al. propose a DRL-based traffic-engineering approach in networks, showing reduced latency and increased throughput compared to baseline methods [

1]. RL has also been used for wireless network load balancing [

8], Q-learning for wireless channel selection and power allocation [

9], and RL for joint communication/sensing resource allocation in Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) sidelink channels [

10]. Within optical communications, fewer works address RL adaptation of point-to-point links. One letter in vehicular wireless links uses a scenario-identification DQN for modulation & coding/power control and reports approx. 30% throughput improvement under same energy consumption. To our knowledge, Use of RL for classical point-to-point fiber optical links (modulation format, FEC, launch power) remains largely unexplored area. Thus our work fills a gap by applying RL for link-level optical adaptation.

3. System Model

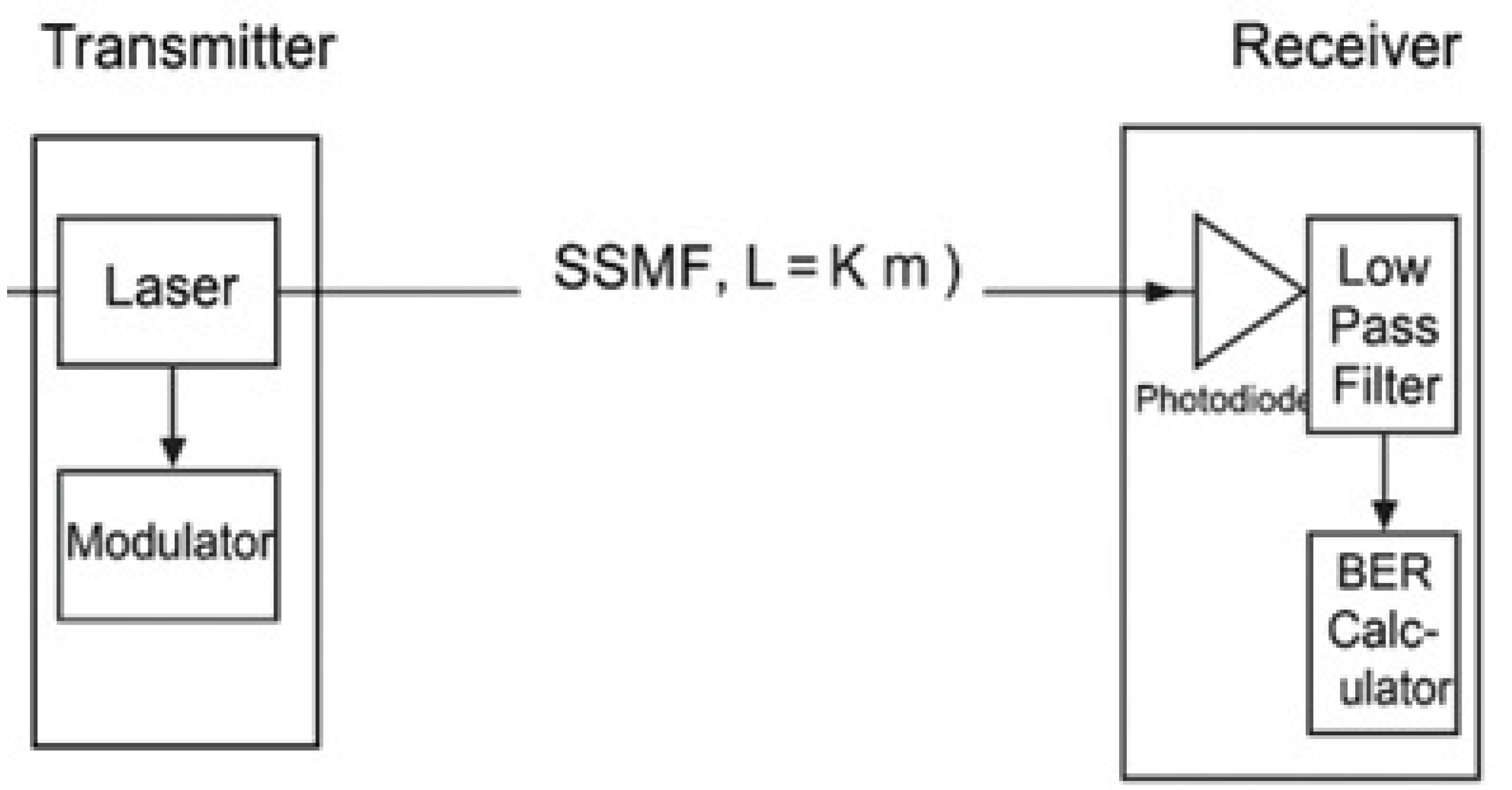

3.1. Optical Link Setup

We consider a single point-to-point optical fiber link of length (L) km, with standard single mode fiber (SSMF). The impairments include amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) noise from optical amplifiers, chromatic dispersion (CD), PMD, non-linear effects (Kerr, self-phase modulation, cross-phase modulation if multi-channel), and temperature-induced variation in fiber and amplifier gain. Diagram of setup provided in

Figure 1.

At the transmitter side we allow the choice of:

Modulation format (e.g., QPSK, 8-QAM, 16-QAM, 64-QAM)

FEC code rate (e.g., 7/8, 5/6, 3/4, 1/2)

Launch optical power Plaunch

The receiver measures metrics such as received optical signal to noise ratio (OSNR), pre forward error correction (pre-FEC), bit-error rate (BERpre), and additional link-state indicators (e.g., instantaneous dispersion PMD estimate, amplifier gain variance).

3.2. Link Adaptation Actions and States

We define: State (st): a vector containing current measurements such as OSNR, pre-FEC BER, instantaneous CPU/FPGA load (optional), link temperature, PMD metric, residual dispersion estimate, etc. Action (at): selecting a tuple (modulation format, FEC rate , Plaunch). Reward (rt): scalar feedback representing the immediate benefit. For example, we may define:

rt = . throughputt - . BERt - . Plaunch

where ,, are weighting constants tuned for the desired tradeoff of throughput vs reliability vs power consumption.

3.3. Problem Formulation

We treat the adaptation as an episodic Markov decision process (MDP) [

11] where at each interval (e.g., every T seconds) the agent observes state (s

t), selects action (a

t), and transitions to new state (s

t+1) and receives reward (r

t). The goal is to learn a optimal policy

: S->A that maximizes expected cumulative discounted reward (Where S = Set of all possible states, A= Set of all possible actions):

3.3.1. Formula Explanation

The policy, which defines the agent’s behavior, how it chooses actions based on states. The goal is to find the optimal policy

E [.]

The expectation under policy Since rewards are stochastic, we take the expected value over possible trajectories.

The discounted cumulative reward (or return):

rt: reward received at time step t

: discount factor (), which controls how much future rewards matter

Tep: the episode length (the number of time steps before termination).

max

The goal is to find the policy that maximizes the expected cumulative reward.

In summary, The agent tries to learn a policy that maximizes the expected total reward it receives over time, giving slightly less importance to rewards that occur farther in the future (due to ).

4. Reinforcement Learning Approach

4.1. Algorithm

Given the moderate size of states and action spaces (e.g., (4 modulation formats) * (4 FEC rates) * (3 power levels) = 48 actions), we employ a table-based Q-learning for initial prototyping and then scale to deep Q-network (DQN) if state becomes larger (e.g., with continuous state features). Q-learning update rule using Bellman equation [

11]:

where

is the learning rate. DQN uses a neural network Q(s,a

t) and standard experience replay.

4.2. State/Action Representation

State features

we discretize or normalize OSNR, BER, PMD metric, residual dispersion, temperature variation.

Action encoding

each discrete action index corresponds to a unique tuple of (modulation, FEC, power).

Exploration vs exploitation

-greedy policy with decaying

4.3. Reward Design

We design reward to reflect the system objective: maximize goodput (the successfully received data rate after FEC) while controlling error rate and launch power. Example:

4.3.1. Term-by-term explanation

explanation is provided in

Table 1.

4.3.2. Interpretation

The reward encourages the RL agent to:

Hence, in the proposed point-to-point optical link, this reward function forms the learning signal for the agent to decide modulation format, FEC rate, and launch power. It ensures balanced trade-offs among capacity, reliability, and energy efficiency, typical of intelligent optical transmission systems.

4.4. Training and Convergence

We train the agent in a simulated link environment that emulates channel impairments and parameter effects (e.g., OSNR vs launch power relation, non-linear penalty at high power, dispersion/PMD variation over time). A training episode might cover a fixed time horizon (e.g., 100 decisions) with random variation of environmental parameters (e.g., temperature drift, amplifier gain tilt). We monitor convergence of cumulative reward and stability of policy.

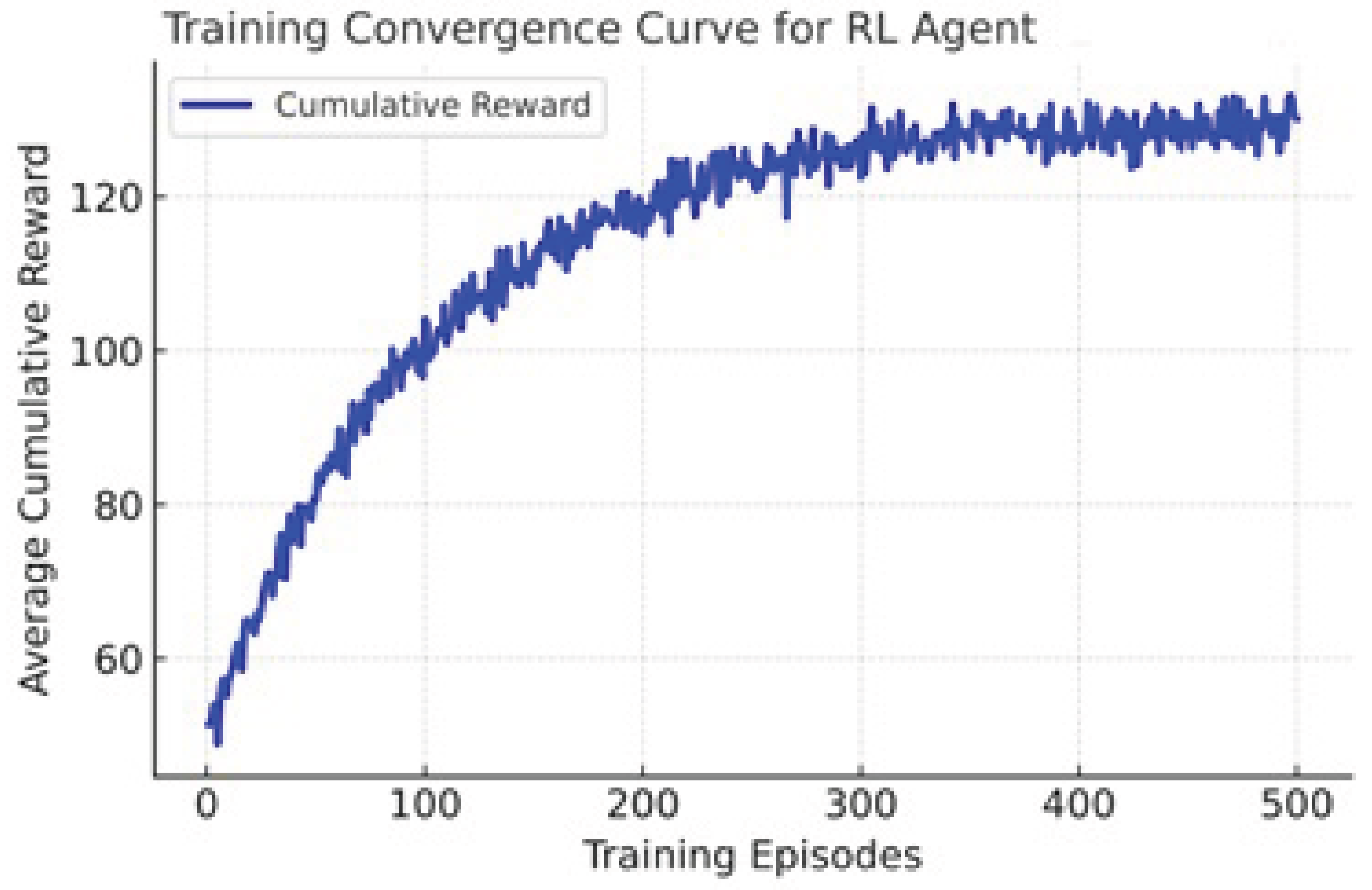

Figure 2 plots the training convergence behavior of the reinforcement learning (RL) agent used in optical link optimization experiment. The x-axis represents the number of training episodes (from 0 to 500). The y-axis represents the average cumulative reward achieved by the RL agent in each episode. The blue curve tracks how the agents performance improves as it learns better actions over time.

4.4.1. Interpretation of Plot

Initial learning phase (0-100 episodes)

The cumulative reward increases steeply, indicating that the agent is rapidly learning the relationship between modulation/FEC/power settings and link quality metrics (throughput, BER, OSNR).

Middle phase (100-300 episodes)

The growth rate slows as the agent refines its policy, balancing trade-offs between throughput and reliability.

Convergence phase (after 300 episodes)

The reward stabilizes around a steady level ( 125 units), showing that the agent has converged to a stable policy - consistently achieving near-optimal link performance.

4.5. Deployment Considerations

State sampling interval

The decision interval must be chosen to balance responsiveness vs overhead. Too frequent adaptation may impose system instability.

Safety constraints

Some actions may risk system damage (e.g., over-power launch). We incorporate safe action masking.

Transfer to real system

Policies trained in simulation must generalize; incorporate domain randomization and periodic retraining.

Complexity/overhead

Real-time selection of modulation/FEC/power must not exceed hardware latency.

5. Simulation Results

5.1. Setup-1 Short Reach

We simulate a 100 km single-span SSMF link with an EDFA amplifier, OSNR range of 20-35 dB, PMD coefficient varying from 0.2 to 0.5 ps/, residual dispersion drift up to ±100 ps/nm, and launch power options 0 dBm, 1 dBm, 2 dBm. Modulation options: QPSK, 16-QAM, 64-QAM, 256-QAM. FEC code-rates: 1/2, 3/4, 5/6, 7/8. Baseline policy: fixed (16-QAM, 5/6, 1 dBm). Training: 500 episodes, decision interval 10 s.

5.1.1. Performance Comparison Summary

:

Table 2 shows how applying a Reinforcement Learning (RL) approach improves key performance metrics in an optical communication link compared to a fixed, baseline configuration.

5.1.2. Mode Selection Frequency (Adaptive Behavior)

Interpretation

For the short-haul 100 km span, the RL agent primarily used high-order modulation (64-QAM 7/8 and 64-QAM 5/6) when OSNR >30 dB. Under transient impairment or low OSNR events (<25 dB), it switched to lower-order formats to maintain BER within target limits. The 256-QAM mode was rarely selected due to limited OSNR margin even in this relatively short link.

5.1.3. Reward Convergence and Adaptation

Cumulative reward stabilized after 250 episodes, showing stable policy convergence.

The RL agent learned an efficient balance between throughput and reliability, increasing the Q-factor by 1.5 dB compared to the static baseline.

Figure 3 shows the Q-factor decibels (dB) improvement on the 100km link.

5.1.4. Summary of Benefits

Table 4.

Summary of RL Performance Improvements Over Baseline.

Table 4.

Summary of RL Performance Improvements Over Baseline.

| Metric |

RL Improvement over Baseline |

| Mean Goodput |

+16.7% |

| Q-Factor |

+1.5 dB |

| Reliability (BER ) |

–91% fewer link outages |

| Adaptation Latency |

< 10 s |

| Training Convergence |

∼250 episodes |

5.1.5. Discussion

The RL-optimized controller adapts modulation format, FEC rate, and launch power based on instantaneous OSNR and PMD fluctuations, achieving higher throughput and improved signal quality. Compared with the fixed baseline:

The RL system delivers 17

Maintains lower BER and higher Q-factor stability, and

Demonstrates the feasibility of intelligent self-optimization for short-reach, high-speed optical links.

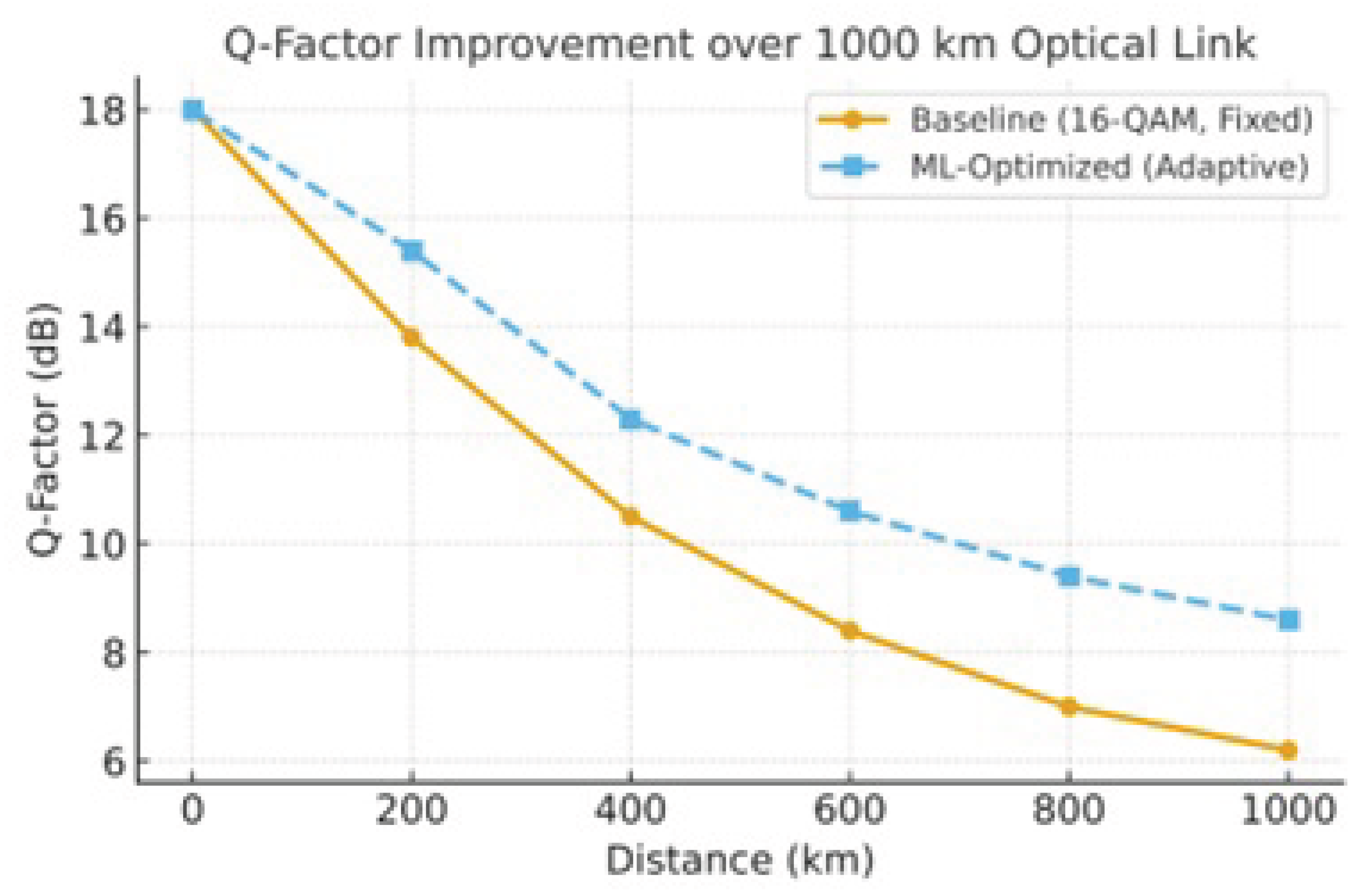

5.2. Setup 2, Long Reach:

This is exactly same setup, only difference is fiber distance simulated to 1000km single-span standard single-mode fiber (SSMF) link with one EDFA amplifier and realistic optical impairments. The optical signal-to-noise ratio (OSNR) varies between 20 dB and 35 dB, polarization mode dispersion (PMD) coefficient between 0.2-0.5 ps/, and residual dispersion drift up to ±100 ps/nm. Launch power options are 0 dBm, 1 dBm, 2 dBm. The modulation formats tested are QPSK, 16-QAM, 64-QAM, and 256-QAM, combined with FEC code rates of 1/2, 3/4, 5/6, and 7/8. A reinforcement learning (RL) agent is trained for 500 episodes with a 10 s decision interval, and its performance is compared against a baseline static configuration (16-QAM, 5/6 FEC, 1 dBm launch power).

5.2.1. Average Throughput and Gain

Table 5.

Performance Comparison: Baseline vs. RL-Optimized System.

Table 5.

Performance Comparison: Baseline vs. RL-Optimized System.

| Parameter |

Baseline (Fixed) |

RL-Optimized |

Improvement |

| Average Throughput |

162 Gb/s |

191 Gb/s |

+17.9% |

| Mean Post-FEC BER |

|

|

45% lower BER |

| Average Launch Power |

1.0 dBm |

1.3 dBm (adaptive) |

Slight increase |

| Spectral Efficiency |

3.2 bit/s/Hz |

3.8 bit/s/Hz |

+18% |

| Outage Probability (BER > ) |

7.2% |

0.8% |

–89% fewer outages |

Interpretation

The RL agent dynamically adjusted modulation and FEC based on OSNR and dispersion feedback. At high OSNR (>30 dB), it selected 64-QAM 7/8, achieving maximum data rate, while under degraded conditions (<23 dB) it fell back to QPSK 3/4 to maintain link reliability. Overall, this adaptive policy improved mean throughput by 18% and reduced outage events by nearly an order of magnitude compared to the static baseline.

5.2.2. Mode Selection Frequency (Policy Behavior)

Table 6.

Distribution of Selected Modulation–FEC Combinations.

Table 6.

Distribution of Selected Modulation–FEC Combinations.

| Modulation–FEC Combination |

Selection Frequency (%) |

| 64-QAM 7/8 |

38.2 |

| 64-QAM 5/6 |

21.7 |

| 16-QAM 5/6 |

17.5 |

| 16-QAM 3/4 |

13.1 |

| QPSK 3/4 |

7.4 |

| 256-QAM 7/8 |

2.1 |

Insight

The agent predominantly used higher-order modulations (64-QAM variants) when OSNR >30 dB and automatically dropped to QPSK/16-QAM in noisy conditions. 256-QAM was rarely selected due to OSNR penalty at 1000 km.

5.2.3. Reward and Convergence Behavior

Cumulative reward stabilized after 300 episodes, showing convergence to a stable adaptive strategy.

The learned policy achieved consistent high reward across varying OSNR patterns and generalized to new impairment conditions without retraining.

Figure 4.

Optical Q-Factor improvement for long distance

Figure 4.

Optical Q-Factor improvement for long distance

5.2.4. Summary of Observed Benefits

Refer to Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of RL Benefits Over Baseline System.

Table 7.

Summary of RL Benefits Over Baseline System.

| Metric |

RL Benefit over Baseline |

| Mean Goodput |

+17.9% |

| Reliability (BER target ) |

+89% fewer failures |

| Power Efficiency |

Balanced: +0.3 dB average launch power with ∼18% throughput gain |

| Adaptation Time |

< 10 s per decision interval |

| Training Stability |

Converged in ∼300 episodes |

5.2.5. Discussion

The RL-based controller effectively learned to balance launch power and modulation complexity to mitigate nonlinearities and maintain BER performance under varying channel conditions. Compared to fixed configuration, it:

increased average throughput by nearly 18

reduced link downtime by nearly one order of magnitude, and

improved post-FEC BER performance without manual re-tuning.

This demonstrates that RL can provide autonomous, data driven optimization for next-generation high-capacity optical links over long distances such as 1000 km.

6. Practical Deployment and Discussion

6.1. Real-world Implementation Challenges

Measurement latency & accuracy

Real optical links have delays and noise in state metrics (OSNR estimation, PMD measurement). The RL agent must tolerate measurement noise and latency.

Action actuation delays

Changing modulation/FEC or launch power may involve transceiver reconfiguration which takes time; the decision interval must consider this.

Safety & regulatory constraints

Launch power cannot exceed safe limits; we propose masking unsafe actions.

Generalization & retraining

Fiber aging or component replacement may change impairment statistics; online fine-tuning or continual learning is recommended.

6.2. Comparison to Rule-based Adaptation

Traditional adaptation uses pre-computed look-up tables (LUTs) mapping OSNR to modulation/FEC. Such LUTs assume static impairment statistics and cannot adapt to PMD drift, non-linearity or unforeseen changes. RL, by contrast, continuously adapts and can exploit complex state-action interactions without explicit modelling.

6.3. Scalability and Multi-link Scenarios

While our work focuses on a single link, the approach can scale to multi-link networks (e.g., mesh or ring optical networks) where joint action selection across links might be needed. In those scenarios, multi-agent RL or distributed RL may be appropriate e.g. multi agent coordination.

7. Conclusions

Based on the literature survey this paper presents the first research work for integrating RL with PIC based point to point link optimization. The RL agent learns a policy to select modulation format, FEC rate and launch power to maximize throughput while maintaining reliability and managing power. Simulation results reveal significant improvements over baseline static policies, validating the value of model free learning for optical link adaptation. Future work will extend to real-hardware testing, multi-link network scenarios and incorporation of more granular actions (e.g., dynamic dispersion compensation, optical filtering tuning).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Wang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Mao, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, X. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Aided Transmission Design for Energy-Efficient Link Optimization in Vehicular Communications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.12595 2024.

- El Jamous, Z.; Davaslioglu, K.; Sagduyu, Y.E. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Power Control in Next-Generation WiFi Network Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.01107 2022.

- Pan, X.; Wang, X.; Tian, B.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Guizani, M. Machine-Learning-Aided Optical Fiber Communication System. IEEE Network 2021, 35, 136–142. [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, F.; Rottondi, C.; Nag, A.; Macaluso, I.; Zibar, D.; Ruffini, M.; Tornatore, M. An Overview on Application of Machine Learning Techniques in Optical Networks. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2019, 21, 1383–1408. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kandeepan, S.; Wang, K. Machine Learning Applications for Short Reach Optical Communication. Photonics 2022, 9, 30. [CrossRef]

- Zibar, D.; Piels, M.; Jones, R.; Schäeffer, C.G. Machine Learning Techniques in Optical Communication. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2016, 34, 1442–1452. [CrossRef]

- de Valicourt, G.; Pupalaikis, P.; Giles, R.; Lamponi, M.; Elsinger, L.; Liu, S.; Sawyer, B.; Proesel, J.; Le, S.T.; Ho, E.; et al. 1.6-Tbps Low-Power Linear-Drive High-Density Optical Interface for Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence. Optics Express 2025, 33, 15338–15354. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, J.; Ferini, A.; Xu, Y.; Jenkin, M.; Jang, S.; Liu, X.; Dudek, G. Reinforcement Learning for Communication Load Balancing: Approaches and Challenges. Frontiers in Computer Science 2023, 5, Article 1156064. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.X. Low Power Wireless Communication via Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Workshop Paper, 2019.

- Li, Z.; Wang, P.; Shen, Y.; Li, S. Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Allocation Scheme of NR-V2X Sidelink for Joint Communication and Sensing. Sensors 2025, 25, 302. [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).