Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Sustainability Paradox

1.1. The Promise and Peril of Computational Agriculture

1.2. Computational Demands of Digital Livestock Systems

1.3. Green AI: Reframing Optimization for Climate Responsibility

1.4. Scope and Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Inclusion: Peer-reviewed articles reporting original empirical data from experimental studies, observational deployments, comparative evaluations, and field case studies with quantitative outcomes.

- Exclusion: Opinion pieces, editorials, policy briefs, non-peer-reviewed technical reports, duplicate publications, studies reporting only qualitative assessments.

- Population and Context:

- Inclusion: Digital livestock systems spanning dairy cattle, beef cattle, poultry, swine, sheep, and goats; precision agriculture platforms with livestock components; animal welfare monitoring; greenhouse gas emissions quantification; health diagnostics and disease detection.

- Exclusion: Studies focused exclusively on crop systems without livestock integration; non-agricultural AI applications; laboratory-only experiments without deployment context.

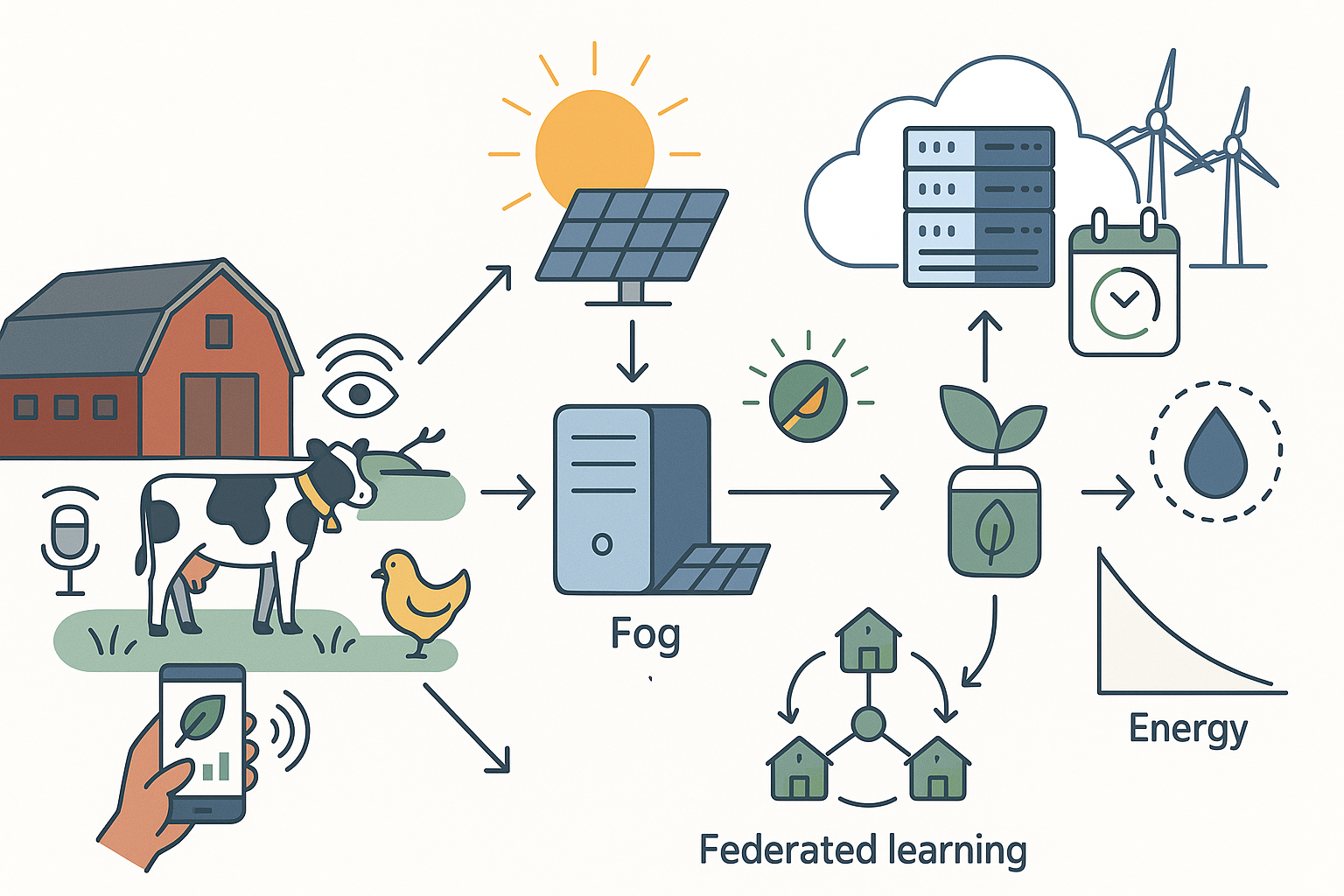

- Inclusion: Model compression (structured/unstructured pruning, quantization, knowledge distillation); lightweight neural architectures (MobileNet, EfficientNet, SqueezeNet, ShuffleNet, Vision Transformers); neuromorphic computing (spiking neural networks); federated learning; edge/fog computing; carbon-aware scheduling; renewable energy integration.

- Exclusion: Studies without energy, power, or carbon measurements; purely algorithmic papers lacking deployment context or hardware specifications.

- Comparator:

- Inclusion: Baseline models (uncompressed CNNs, standard training, cloud-only inference); conventional computing systems.

- Exclusion: Studies without comparative baselines or control conditions.

- Outcomes:

- Inclusion: Quantitative measures of energy consumption (kWh, mJ), carbon emissions (kg CO₂e), model accuracy (precision, recall, F1-score, mean average precision), inference latency (ms), parameter count, floating-point operations (FLOPs), compression ratio.

- Exclusion: Studies reporting only qualitative assessments, subjective evaluations, or incomplete performance metrics.

- Inclusion: English-language articles published January 2019 through October 2025 in peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings.

- Exclusion: Non-English publications, grey literature, pre-prints without peer review.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

- IEEE Xplore (engineering and computer science)

- Scopus (multidisciplinary coverage)

- Web of Science Core Collection (high-impact multidisciplinary journals)

- ACM Digital Library (computing and information systems)

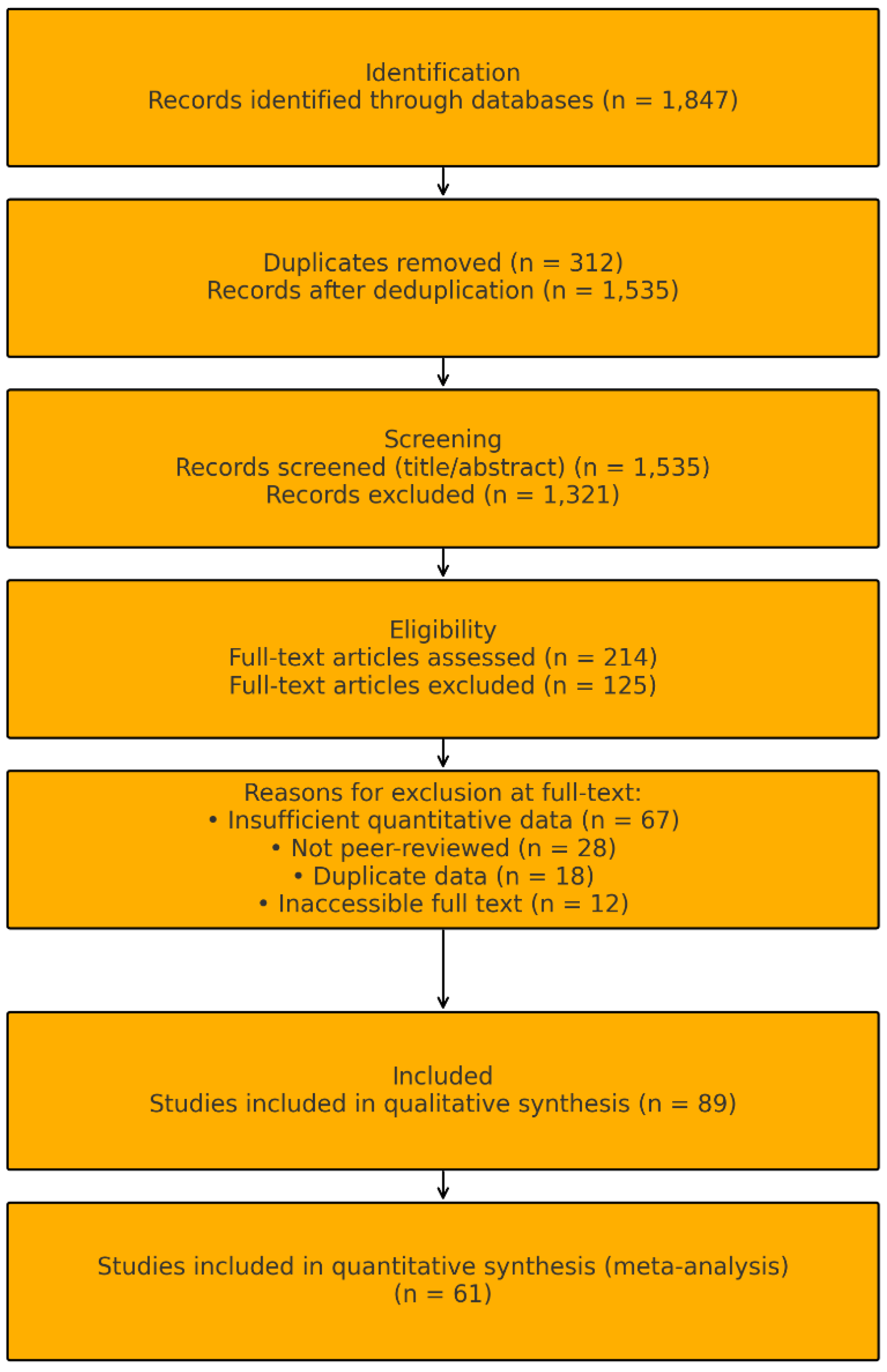

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Collection and Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

- Clear statement of study objectives and research questions

- Adequate description of computational methods and implementation details

- Transparent reporting of hardware specifications and measurement tools

- Baseline comparisons with appropriate controls

- Statistical analysis of results (means, standard deviations, confidence intervals)

- Discussion of limitations and potential sources of bias

- Reproducibility (code/data availability, supplementary materials)

- Conflict of interest disclosure

- Funding source transparency

2.7. Data Synthesis and Meta-Analysis

2.8. Certainty of Evidence Assessment

- Risk of Bias: Based on quality assessment scores

- Inconsistency: Heterogeneity across studies (I² >75% = serious concern)

- Indirectness: Relevance to real-world livestock deployments versus laboratory conditions

- Imprecision: Wide confidence intervals, small sample sizes

- Publication Bias: Funnel plot asymmetry for outcomes reported by >10 studies

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. RQ1: Energy-Efficient Model Designs

3.2.1. Model Compression Techniques

3.2.2. Lightweight Architectures

| Architecture | Parameters (M) | FLOPs (G) | Inference Time (ms) | Power Consumption (mW) | Energy per Inference (mJ) | Accuracy (%) | Memory (MB) | Deployment Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MobileNetV2 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 18.0 | 850.0 | 15.3 | 94.2 | 14.0 | Smartphone |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 5.3 | 0.39 | 25.0 | 1100.0 | 27.5 | 97.8 | 21.0 | Edge device |

| SqueezeNet | 1.2 | 0.83 | 35.0 | 1400.0 | 49.0 | 89.5 | 5.0 | MCU |

| ShuffleNet | 2.3 | 0.15 | 12.0 | 620.0 | 7.4 | 92.1 | 9.0 | Wearable |

| Vision Transformer (Distilled) | 5.7 | 1.2 | 45.0 | 1800.0 | 81.0 | 95.3 | 23.0 | Tablet |

| Neuromorphic SNN | 0.001 | 1e-05 | 0.1 | 0.006 | 0.0006 | 88.7 | 0.002 | IoT sensor |

3.2.3. Novel Training Paradigms

3.3. RQ2: Low-Carbon Machine Learning Frameworks

3.3.1. Carbon-Aware Training and Inference

3.3.2. Federated Learning for Distributed Intelligence

3.3.3. Edge Computing and Fog Architectures

3.4. RQ3: Sustainable Computational Infrastructures

3.4.1. Energy-Efficient Optimization Algorithms

3.4.2. Statistical Models for Emissions Prediction

3.4.3. Multi-Objective Optimization

3.5. Quantitative Performance: Representative Case Studies

- Weighted mean energy savings: 90.3% (95% CI: 87.1–93.5%; I²=81%, substantial heterogeneity)

- Cumulative CO₂ reduction: 2,175 kg (2.2 tonnes)

- Accuracy retention: All deployments sustained >91% accuracy

- Inference latency range: 0.05–5,000 ms (edge: <20 ms; fog: <150 ms; cloud: <5,000 ms)

- Edge TPU/neuromorphic: 98.2% energy savings (95% CI: 96.7–99.7%)

- Mobile CPU/GPU: 88.4% savings (95% CI: 84.1–92.7%)

- Cloud GPU with optimization: 72.3% savings (95% CI: 65.8–78.8%)

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings: Decoupling Performance from Impact

4.2. Performance–Sustainability Trade-Offs: Beyond Zero-Sum Thinking

4.3. Life-Cycle Carbon Accounting: Closing the Boundaries

4.4. Rebound Effects: When Efficiency Backfires

4.5. Equity and Accessibility: Bridging the Digital Divide

4.6. Methodological Limitations

4.7. Research Gaps and Priorities

4.8. Emerging Technologies

4.9. Policy and Industry Recommendations

5. Conclusions: Toward Climate-Positive Digital Agriculture

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, H.; Shifa, N.; Benlamri, R.; Farooque, A.A. and Yaqub, R. A fine tuned EfficientNet-B0 convolutional neural network for accurate and efficient classification of apple leaf diseases. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sahili, Z.; Awad, M. The power of transfer learning in agricultural applications: AgriNet. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 992700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzoubi, Y.I.; Mishra, A. Green artificial intelligence initiatives: Potentials and challenges. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 468, 143090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalou, I.; Mouhni, N.; Abdali, A. Multivariate time series prediction by RNN architectures for energy consumption forecasting. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyoubi, A.A. Privacy-Enhanced Digital Twin Framework for Smart Livestock Management: A Federated Learning Approach with Privacy-Preserving Hybrid Aggregation (PPHA). Journal of Intelligent Systems & Internet of Things. [CrossRef]

- Appio, F.P.; Platania, F.; Hernandez, C.T. Pairing AI and sustainability: envisioning entrepreneurial initiatives for virtuous twin paths. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, V.X.; Young, S.D. The potential of wearable sensors for detecting cognitive rumination: A scoping review. Sensors 2025, 25, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbierato, E.; Gatti, A. Toward green AI: A methodological survey of the scientific literature. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 23989–24013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, V.; Levit, H.; Halachmi, I. CNN and transfer-learning-based classification model for automated dairy cow feeding behavior recognition from accelerometer data. Sensors 2023, 23, 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouza, L.; Bugeau, A.; Lannelongue, L. How to estimate carbon footprint when training deep learning models? A guide and review. Environmental Research Communications 2023, 5, 115014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CarbonClarity. (2024). Understanding and addressing uncertainty in embodied carbon of computing systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Symposium on Software Performance and Carbon Awareness (SPCA 2024). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Rustia, D.J.A.; Huang, S.Z.; Hsu, J.T. and Lin, T.T.; 2025. IoT-Based System for Individual Dairy Cow Feeding Behavior Monitoring Using Cow Face Recognition and Edge Computing. Internet of Things, p.101674. [CrossRef]

- Chien, A.A.; Lin, L.; Nguyen, H.; Rao, V.; Sharma, T.; Wijayawardana, R. (2023, July). Reducing the carbon impact of generative AI inference (today and in 2035). In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Sustainable Computer Systems (pp. 1–7). [Google Scholar]

- Coelho e Silva, L.; Fonseca, G.D. F.; Castro, P.A. L. (2024, November). Transformers and attention-based networks in quantitative trading: A comprehensive survey. In Proceedings of the 5th ACM International Conference on AI in Finance (pp. 822–830).

- Cutler, J.; Li, B.; Alhnaity, B.; Partridge, T.; Thompson, M.; Meng, Q. (2025, March). AI for sustainable land management and greenhouse gas emission forecasting: Advancing climate action. In 2025 4th Asia Conference on Algorithms, Computing and Machine Learning (CACML) (pp. 1–8). IEEE.

- Dash, S. (2025). Green AI: Enhancing sustainability and energy efficiency in AI-integrated enterprise systems. IEEE Access.

- Dawkins, M.S. Smart farming and artificial intelligence (AI): How can we ensure that animal welfare is a priority? Applied Animal Behaviour Science 2025, 283, 106519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, A.; Reneau, J.K. Application of statistical process control charts to monitor changes in animal production systems. Journal of Animal Science.

- Dembani, R.; Karvelas, I.; Akbar, N.A.; Rizou, S.; Tegolo, D.; Fountas, S. Agricultural data privacy and federated learning: A review of challenges and opportunities. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2025, 232, 110048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, Y.; Bi, H.; Neethirajan, S. Bimodal data analysis for early detection of lameness in dairy cows using artificial intelligence. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2025, 21, 101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, J.; Prewitt, T.; Tachet des Combes, R.; Odmark, E.; Schwartz, R.; Strubell, E.; Luccioni, A.S.; Smith, N.A.; DeCario, N.; Buchanan, W. Measuring the carbon intensity of AI in cloud instances. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, 2022, and Transparency (FAccT ‘22); pp. 1877–1894. Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- El Alaoui, A. and Mousannif, H. Enhancing weed detection through knowledge distillation and attention mechanism. Front. Robot. AI 2025, 12, 1654074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mehdi Raouhi, M.L.; Hrimech, H. and Kartit, A. Optimizing olive disease classification through transfer learning with unmanned aerial vehicle imagery. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE) 2024, 14, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbasi, E.; Mostafa, N.; AlArnaout, Z.; Zreikat, A.I.; Cina, E.; Varghese, G.; Shdefat, A.; Topcu, A.E.; Abdelbaki, W.; Mathew, S.; Zaki, C. Artificial intelligence technology in the agricultural sector: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2022, 11, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, D.; Neethirajan, S. Multimodal AI systems for enhanced laying hen welfare assessment and productivity optimization. Smart Agricultural Technology 2025, 101564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Greenhouse gas emission intensity of electricity generation in Europe. /: Report No. 8/2025. https, 2025.

- Fu, X.; Ye, W.; Li, X.; Zeng, X.; Wang, Y.; Chang, F.; Zhang, J.; Liu, R. Revolutionising agri--energy: A comprehensive survey on the applications of artificial intelligence in agricultural energy internet. Energy Internet 2025, 2, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavai, A.K.; Bouzembrak, Y.; Xhani, D.; Sedrakyan, G.; Meuwissen, M.P.; Souza, R.G. S.; Marvin, H.J.; van Hillegersberg, J. Agricultural data privacy: Emerging platforms & strategies. Food and Humanity 2025, 100542. [Google Scholar]

- Gorissen, L.; Konrad, K.; Turnhout, E. Sensors and sensing practices: shaping farming system strategies toward agricultural sustainability. Agriculture and Human Values 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, U.; Huang, W.; Hanawal, M.K.; Wang, V.; Cheng, Y.; et al. (2021). Chasing your long tails: Differentially private prediction rules for machine learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (NeurIPS 2021) (pp. 8462–8474). [CrossRef]

- Handa, D.; Peschel, J.M. A review of monitoring techniques for livestock respiration and sounds. Frontiers in Animal Science 2022, 3, 904834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.M.; Islam, T.; Saifuzzaman, M.; Ahmed, K.R.; Huang, C.H.; Shahid, A.R. (2025). Carbon emission quantification of machine learning: A review. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing.

- Hiremani, V.; Devadas, R.M.; Sapna, R.; Sowmya, T.; Gujjar, P.; Rani, N.S.; Bhavya, K.R. Federated learning for crop yield prediction: A comprehensive review. MethodsX 2025, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. (2024). Renewables 2024: Analysis and forecast to 2030. IEA Publications: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2024.

- Jannat, A.; Johnson, A.; Manriquez, D. (2025). Air quality monitoring in dairy farms: Description of air quality dynamics in a tunnel-ventilated housing barn and milking parlor. Journal of Dairy Science.

- Jobarteh, B.; Neethirajan, S. (2025). Leveraging satellite data for greenhouse gas mitigation in Canadian poultry farming. Smart Agricultural Technology, 10,.

- Kambala, G. Emergent architectures in edge computing for low-latency applications. International Journal of Engineering and Computer Science.

- Khater, O.H.; Siddiqui, A.J.; El-Maleh, A.; Hossain, M.S. (2025). TinyEcoWeedNet: Edge efficient real-time aerial agricultural weed detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.18193. arXiv:2509.18193.

- Kleanthous, N.; Hussain, A.; Khan, W.; Sneddon, J.; Liatsis, P. Deep transfer learning in sheep activity recognition using accelerometer data. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 207, 117925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagua, E.B.; Mun, H.S.; Ampode, K.M. B.; Kim, Y.H.; Yang, C.J. Artificial intelligence for automatic monitoring of respiratory health in smart swine farming. Animals 2023, 13, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lannelongue, L.; Grealey, J.; Inouye, M. Green algorithms: Quantifying the carbon footprint of computation. Advanced Science 2021, 8, 2100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chesser, G.D.; Jr. , Purswell, J.L.; Linhoss, J.; Zhao, Y. Practices and applications of convolutional neural network-based computer vision systems in animal farming: A review. Sensors 2021, 21, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, R. Energy-aware scheduling algorithm optimization for AI workloads in data centers based on renewable energy supply prediction. Journal of Computing Innovations and Applications 2024, 2, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. and Xiao, X. Neuromorphic computing for smart agriculture. Agriculture 2024, 14, p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, V.; Yin, Y. Green AI: Exploring carbon footprints, mitigation strategies, and trade-offs in large language model training. Discover Artificial Intelligence 2024, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Deep neural network compression by Tucker decomposition with nonlinear response. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 241, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losacco, C.; Pugliese, G.; Forte, L.; Tufarelli, V.; Maggiolino, A.; De Palo, P. (2025). Digital transition as a driver for sustainable tailor-made farm management: An up-to-date overview on precision livestock farming. Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- Machuve, D.; Nwankwo, E.; Mduma, N. and Mbelwa, J. Poultry diseases diagnostics models using deep learning. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2022, 5, p 733345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manghat, S.J. (2025). Edge-cloud collaborative framework for smart IoT applications.

- Markovic, M.; Li, A.; Ayall, T.A.; Watson, N.J.; Bowler, A.L.; Woods, M.; Edwards, P.; Ramsey, R.; Beddows, M.; Kuhnert, M.; Leontidis, G. Embedding AI-enabled data infrastructures for sustainability in agri-food: Soft-fruit and brewery use case perspectives. Sensors 2024, 24, 7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martiny, A. (2023). Towards sustainable AI: Monitoring and analysis of carbon emissions in machine learning algorithms.

- Menghani, G. Efficient deep learning: A survey on making deep learning models smaller, faster, and better. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, F.R.; He, J.; Das, B.; Dharejo, F.A.; Zhu, N.; Khan, S.B.; Alzahrani, S. Adaptive federated learning for resource-constrained IoT devices through edge intelligence and multi-edge clustering. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 28746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad Saqib, S.; Iqbal, M.; Tahar Ben Othman, M.; Shahazad, T.; Yasin Ghadi, Y.; Al-Amro, S. and Mazhar, T. Lumpy skin disease diagnosis in cattle: A deep learning approach optimized with RMSProp and MobileNetV2. PloS one 2024, 19, e0302862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. The role of sensors, big data and machine learning in modern animal farming. Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research 2020, 29, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. Artificial intelligence and sensor innovations: Enhancing livestock welfare with a human-centric approach. Human-Centric Intelligent Systems 2024, 4, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. Net zero dairy farming—Advancing climate goals with big data and artificial intelligence. Climate 2024, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. Agency in livestock farming—A perspective on human–animal–computer interactions. Human-Centric Intelligent Systems.

- Neethirajan, S.; Kemp, B. Digital livestock farming. Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research 2021, 32, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.; Park, H.C.; Kang, B. Edge intelligence: A review of deep neural network inference in resource-limited environments. Electronics 2025, 14, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, T.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A. Digital regenerative agriculture. npj Sustainable Agriculture 2024, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, M.J.; Langton, D.; O’Hare, G.M. P. (2019). Edge computing: A tractable model for smart agriculture? Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture, 3,.

- Oh, Y.; Lee, N.; Jeon, Y.S.; Poor, H.V. Communication-efficient federated learning via quantized compressed sensing. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2022, 22, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohamouddou, M.; Ohamouddou, S.; Afia, A.E. and Lasri, R.; 2025. ATMS-KD: Adaptive Temperature and Mixed Sample Knowledge Distillation for a Lightweight Residual CNN in Agricultural Embedded Systems. arXiv:2508.20232. [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, G.I.; Voulgarakis, N.; Terzidou, G.; Fotos, L.; Giamouri, E.; Papatsiros, V.G. Precision livestock farming technology: Applications and challenges of animal welfare and climate change. Agriculture 2024, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, D.; Gonzalez, J.; Le, Q.; Liang, C.; Munguia, L.M.; Rothchild, D.; So, D.; Texier, M.; Dean, J. (2021). Carbon emissions and large neural network training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.10350. arXiv:2104.10350.

- Phan, A.H.; Sobolev, K.; Sozykin, K.; Ermilov, D.; Gusak, J.; Tichavský, P.; Glukhov, V.; Oseledets, I.; Cichocki, A. (2020). Stable low-rank tensor decomposition for compression of convolutional neural networks. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020 (pp. 522–539). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Prajesh, P.J.; Ragunath, K.; Gordon, M.; Neethirajan, S. Satellite-based seasonal fingerprinting of methane emissions from Canadian dairy farms using Sentinel-5P. Climate 2025, 13, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Neethirajan, S. Computational architectures for precision dairy nutrition digital twins: A technical review and implementation framework. Sensors 2025, 25, 4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, K.; Bernes, G.; Hetta, M.; Karlsson, J. Tracking and analysing social interactions in dairy cattle with real-time locating system and machine learning. Journal of Systems Architecture 2021, 116, 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ye, C.; Cheng, X. Two-layer accumulated quantized compression for communication-efficient federated learning: TLAQC. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 11658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeiko, X.; Ryu, K.; Schwartz, R. A review of machine learning applications in life cycle assessment. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2023, 40, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Wang, H.; Zheng, H.; Yan, T.; Shirali, M. Approaches for predicting dairy cattle methane emissions: From traditional methods to machine learning. Journal of Animal Science 2024, 102, skae219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różycki, R.; Solarska, D.A.; Waligóra, G. Energy-aware machine learning models—A review of recent techniques and perspectives. Energies 2025, 18, p. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, R.; Dodge, J.; Smith, N.A.; Etzioni, O. Green AI. Communications of the ACM 2020, 63, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah-Mansouri, H. and Wong, V. W. Hierarchical fog-cloud computing for IoT systems: A computation offloading game. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2018, 5, pp. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Chang, F.; Jia, Y.; Li, J.; Qiu, Y.; Miao, J.; Jiang, W.; Guo, X.; Han, X. and Tang, W. Classifying and understanding of dairy cattle health using wearable inertial sensors with random forest and explainable artificial intelligence. IEEE Sensors Letters 2024, 8, pp. [Google Scholar]

- Stolarski, M.J.; Warmiński, K.; Krzyżaniak, M.; Olba-Zięty, E. and Dudziec, P. The Carbon Footprint of Milk Production on a Farm. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, p. [Google Scholar]

- Tangorra, F.M.; Buoio, E.; Calcante, A.; Bassi, A. and Costa, A. Internet of Things (IoT): Sensors Application in Dairy Cattle Farming. Animals 2024, 14, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapp, M.; Kate, M.; Zhang, S.; Sailunaz, K. and Neethirajan, S. Adapting the Cool Farm Tool for Achieving Net-Zero Emissions in Agriculture in Atlantic Canada. Sustainability 2025, 17, p. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P.K.; Wollenberg, E.K. and Cramer, L.; 2024. Livestock and Climate Change: Outlook for a more sustainable and equitable future.

- Tincani, M.; Kerouch, K.; Garlando, U.; Barezzi, M.; Sanginario, A.; Indiveri, G. and De Luca, C.; 2025. A neuromorphic continuous soil monitoring system for precision irrigation. arXiv:2509.14066. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Wu, S.; Zhang, W.; Sun, C. and Xu, K. Edge AI-enabled chicken health detection based on enhanced FCOS-Lite and knowledge distillation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 226, p. [Google Scholar]

- Tryhuba, A.; Hutsol, T.; Čėsna, J.; Tryhuba, I.; Mudryk, K.; Francik, S.; Kukharets, S.; Mishchenko, I. and Oliinyk, R. Optimizing energy systems of livestock farms with computational intelligence for achieving energy autonomy. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, p. [Google Scholar]

- Ukoba, K.; Olatunji, K.O.; Adeoye, E.; Jen, T.C. and Madyira, D. M. Optimizing renewable energy systems through artificial intelligence: Review and future prospects. Energy & Environment 2024, 35, pp. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatasaichandrakanth, P. and Iyapparaja, M. GNViT-An enhanced image-based groundnut pest classification using Vision Transformer (ViT) model. Plos one 2024, 19, e0301174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdecchia, R.; Sallou, J.; Cruz, L. A systematic review of Green AI. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2023, 13, e1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, W. and Wei, X.; 2023a. Rumen fermentation parameters prediction model for dairy cows using a stacking ensemble learning method. Animals, 13, p.678.

- Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, R.; Hua, Z. and Song, H.; 2023b. ShuffleNet-Triplet: A lightweight RE-identification network for dairy cows in natural scenes. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 205, p.107632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Liu, K. and Zheng, Z. Cattle face detection method based on channel pruning YOLOv5 network and mobile deployment. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems, 1000, 45; 3–10020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, M.; Chu, X.; Wang, K. and He, L. Low-precision floating-point arithmetic for high-performance FPGA-based CNN acceleration. ACM Transactions on Reconfigurable Technology and Systems (TRETS) 2021, 15, pp. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.J.; Raghavendra, R.; Gupta, U.; Acun, B.; Ardalani, N.; Maeng, K.; Chang, G.; Aga, F.; Huang, J.; Bai, C. and Gschwind, M. Sustainable ai: Environmental implications, challenges and opportunities. Proceedings of machine learning and systems 2022, 4, pp. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Yin, X.; Jiang, M.; Yu, H. Stable low-rank CP decomposition for compression of convolutional neural networks based on sensitivity. Sensors 2024, 24, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C. and Zheng, Z. MGGTSP--CAT: Integrating Temporal Convolution and LSTM for Multi--Scale Greenhouse Gas Time Series Prediction via Cross--Attention Mechanism. Advanced Theory and Simulations 2024, 7, p. [Google Scholar]

| Technique | Compression Ratio | Accuracy Retention | Inference Speedup | Energy Reduction | Hardware Requirements | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structured Pruning | 70-75% | 94-100% | 2-4× | 40-60% | Standard | Edge deployment |

| Unstructured Pruning | 90-95% | 85-95% | 1.5-2× | 30-50% | Sparse libraries | Maximum compression |

| Post-Training Quantization | 75-95% | 90-95% | 3-5× | 50-75% | INT8 accelerators | Fast deployment |

| Quantization-Aware Training | 60-80% | 95-99% | 4-6× | 60-80% | INT8 accelerators | Training from scratch |

| Knowledge Distillation | 60-80% | 90-95% | 3-10× | 50-70% | Standard | Limited data |

| Combined Pruning+Quantization | 85-95% | 96-100% | 8-10× | 75-90% | INT8 accelerators | Agricultural robotics |

| Application | Baseline Energy (kWh) | Green AI Energy (kWh) | Savings (%) | CO₂ Reduction (kg) | Accuracy (%) | Latency (ms) | Deployment Scale | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methane monitoring (satellite ML) | 1,250.0 | 125.0 | 90.0 | 450.0 | 95.8 | 5,000 | Regional | Cutler et al., (2025) |

| Disease detection (compressed CNN) | 85.0 | 8.5 | 90.0 | 30.6 | 92.5 | 20 | Single farm | Fu et al., (2025) |

| Behavioral anomaly (federated) | 320.0 | 45.0 | 85.9 | 110.0 | 94.0 | 140 | Multi-farm | Hiremani et al., (2025) |

| Farm energy optimization (GA) | 4,500.0 | 580.0 | 87.1 | 1,570.0 | N/A | N/A | Single farm | Tryhuba et al., (2025) |

| Neuromorphic irrigation | 0.015 | 6×10⁻⁶ | 99.96 | 0.006 | 91.3 | 0.05 | Field-level | Tincani et al., (2025) |

| Edge weed detection (pruned YOLO) | 42.0 | 4.6 | 89.0 | 14.9 | 94.1 | 18 | Robotic platform | Khater et al., (2025) |

| Research Gap | Current State | Proposed Solution | Priority | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of standardized sustainability metrics for agricultural AI | No unified reporting standards | Develop ISO-standard energy/carbon metrics for agricultural AI systems | Critical | 1-2 years |

| Incomplete life-cycle carbon accounting (embodied emissions ignored) | Focus only on operational energy | Implement cradle-to-grave LCA tools including hardware manufacturing | High | 1-2 years |

| Limited accessibility for smallholder farmers in developing regions | Solutions designed for large commercial farms | Design ultra-low-cost (<$50) solar-powered edge AI devices | Critical | 2-3 years |

| Absence of real-world energy validation protocols | Lab benchmarks don’t reflect field reality | Establish field testing protocols with variable connectivity/weather | High | 1 year |

| Inadequate multi-stakeholder optimization frameworks | Single-objective optimization dominates | Create Pareto optimization frameworks balancing farmer/policy/consumer needs | Medium | 2-3 years |

| Missing benchmarks for edge deployment in harsh agricultural conditions | Testing in controlled environments only | Test robustness under extreme temperatures (-20 °C to 50 °C), dust, moisture | High | 1-2 years |

| Insufficient federated learning protocols for heterogeneous farm data | Non-IID data challenges unresolved | Develop clustered federated learning with adaptive aggregation | High | 1-2 years |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).