1. Background

Among the most common causes of blindness and visual impairment worldwide are retinal and choroidal vascular diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema (DME), retinal vein occlusion (RVO), and neovascular age-related macular degeneration (n-AMD) [

1].

The pathophysiological hallmarks of n-AMD, DME, and RVO edema often intersect, involving oxidative stress, inflammatory cascades, and abnormal angiogenesis. Collectively, these factors converge on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and angiopoietin 2 (Ang-2) which orchestrates pathological vessel growth and elevates vascular permeability [

2,

3]. Co-expression of Ang-2 and VEGF-A has been linked to accelerated neovascularization [

4]. VEGF-A facilitates angiogenesis by encouraging the movement, survival, and development of endothelial cells. Ang-2 has been demonstrated to increase proinflammatory signals in endothelial cells and is implicated in vascular leakage and aberrant vessel shape [

4].

The treatment of retinal disorders has changed over the past 2 decades due to the introduction of anti-vascular endothelial growth factors (anti-VEGFs), which are currently the first-line treatment [

5]. Anti-VEGF agents have become a powerful and successful tool in the fight against RVO, DR complications, and n-AMD. These agents administered intravitreally block proangiogenic factors’ functional activity with varying target selectivity, affinity, and efficacy [

6]. VEGF inhibitors that are currently used to treat retinal disorders are ranibizumab, aflibercept, brolucizumab, and bevacizumab, the latter is used off-label [

7]. In recognition of the multifactorial pathophysiology underlying RVD, research efforts are increasingly focused on developing novel therapeutic approaches that extend beyond VEGF inhibition alone [

8]. Although anti-VEGF therapies have demonstrated efficacy in controlled clinical trials, their effectiveness in real-world practice frequently falls short of expectations. Common obstacles include primary or secondary nonresponse, tachyphylaxis, and recurrence of edema following treatment discontinuation [

9].

Faricimab a new bispecific antibody that targets both VEGF-A and Ang-2, was recently developed by Roche/Genentech to treat DME and n-AMD. Faricimab binds and neutralizes Ang-2, a key regulator of vascular stability, as well as VEGF-A, a major contributor to neovascularization and vascular permeability. By inhibiting VEGF-A, Faricimab lessens neovascularization and vascular permeability, preventing the buildup of retinal fluid that causes macular disorders’ vision loss. Its attachment to Ang-2 also prevents vascular destabilization, which further prevents the buildup of retinal fluid [

10]. This means that, in contrast to current VEGF-A inhibitors, the simultaneous blockage of both pathways offers the possibility of comprehensive therapeutic efficacy [

1].

The aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy and safety of intravitreal Faricimab in patients with refractory macular edema secondary to n-AMD, DME, and RVO, who have previously undergone multiple intravitreal anti-VEGF treatments other than Faricimab and exhibited poor or no response. The study seeks to determine whether Faricimab can provide improved visual and anatomical outcomes in this refractory population.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective, open-label, interventional clinical study included 88 eyes of 76 patients with primary refractory diabetic macular edema (DME), refractory macular edema secondary to retinal vein occlusion (RVO), and refractory neovascular age-related macular degeneration (n-AMD). All patients had previously failed to respond to intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy with bevacizumab and/or aflibercept. This study was carried out at a specialized ophthalmic center in Baghdad, Iraq. Over 6 months, this study encompassed all essential stages, including patient recruitment, baseline evaluations, treatment administration, follow-up assessments, data analysis.

2.2. Ethical Consideration

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of College of Medicine / University of Baghdad (03.37/2025). All participants provided written informed consent after being thoroughly informed about the purpose, risks, procedures, and potential benefits of the research. The research team maintained full compliance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patient data were anonymized and stored securely. The study is officially registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database under the identifier number (NCT07093385).

2.3. Patient Selection Criteria

2.3.1. Patients Inclusion criteria

Patients were considered eligible if they met all the following inclusion criteria:

18 years old or older Patient diagnosed with refractory DME, RVO edema, or active n-AMD by clinical evidence, optical coherence tomography OCT and angiography (OCTA).

Primary refractory patients show persistent subretinal or intraretinal fluid with no improvement BCVA nor a decrease in central retinal thickness after a minimum of 3 loading doses of Bevacizumab and Aflibercept (CRT>300 µm with BCVA either unchanged or worse compared with baseline).

Ability to attend follow-up appointments and comply with treatment protocol.

2.3.2. Patient Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded from the study if any of the following conditions were met:

Inconsistent treatment history: missed a dose of anti-VEGF doses, or failure to complete the three loading doses of Faricimab.

Ocular comorbidities that could confound outcomes, such as: Visually significant cataract as Grade 2+ or more, corneal opacity, uncontrolled glaucoma (IOP > 25 mmHg on medication) with an increase in cup/disc ratio, Other macular pathologies (e.g., macular hole, epiretinal membrane ERM).

Severe baseline vision loss (BCVA < 6/60).

4. Secondary non-responders: patients who initially showed improvement in BCVA and CRT after anti-VEGF therapy, but subsequently experienced deterioration despite continued treatment with bevacizumab and aflibercept.

2.4. Methods

Baseline Assessments and Data collection: To be enrolled in the study, eligible patients gave their written informed consent to be included in the treatment regimen, patients’ demographic data (age and gender) and past medical history for hypertension and diabetes mellitus were documented in an electronic medical records system, and Patients subjected to a combination of tests for complete ophthalmic evaluation after one month from the last anti-VEGF. Both eyes’ Best-Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA) was measured using a Snellen chart, which was subsequently transformed into a log MAR for statistical analysis. Slit lamp ocular examination was performed for anterior segment examination. Subsequently, topical tropicamide 1% eye drops were used to dilate the patient’s pupil. A 90 or 78 diopter condensing lens is used for a thorough inspection of the fundus and macula. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography OCT-A was used to diagnose the cases of wet AMD and CNV, also to exclude ischemic maculopathy cases. Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT) is utilized to evaluate intraretinal fluid (IRF), subretinal fluid (SRF), central retinal thickness (CRT).

Intervention Procedures: All patients receive faricimab loading dose (three intravitreal injections monthly) within two days of examination. Intravitreal administration of Faricimab was performed under aseptic conditions following topical anesthesia with tetracaine hydrochloride (Cooper). The eyelids and eyelashes were disinfected with 10% povidone-iodine solution, and the conjunctival fornices were irrigated with 5% povidone-iodine. Faricimab (6 mg/0.05 mL) was injected into the vitreous via pars plana, approximately 3.5 mm posterior to the limbus, using a 30-gauge needle. Post-injection, topical tobramycin was prescribed four times daily for 5 days.

Outcome Measures: The ophthalmologic assessment was conducted at baseline and repeated again after one month after the third faricimab injection (week 16) to compare the results and to assess treatment response. The response to Faricimab was evaluated both functionally and anatomically. The primary outcomes assessed were the mean (BCVA), (CRT), and complete resolution of retinal fluid.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version XX). BCVA values were converted to logMAR for statistical purposes. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages, while continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For normally distributed continuous variables, paired t-tests were used to compare baseline and post-treatment values. For non-normally distributed variables, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariate analysis (logistic regression) was used to identify predictors of persistent intraretinal fluid (IRF) after faricimab treatment.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data and Medical Background of Patients

A total of 76 patients were included in the study, with a mean age of 66.14±8.678 years range between (46-83) with 43 (56.57%) case ≥ 65 years and 33 (43.42%) case < 65 years. The total number of males were 37 (48.68%) and females were 39 (51.32%) with a ratio of female to male (1.05:1.0).

Table 1.

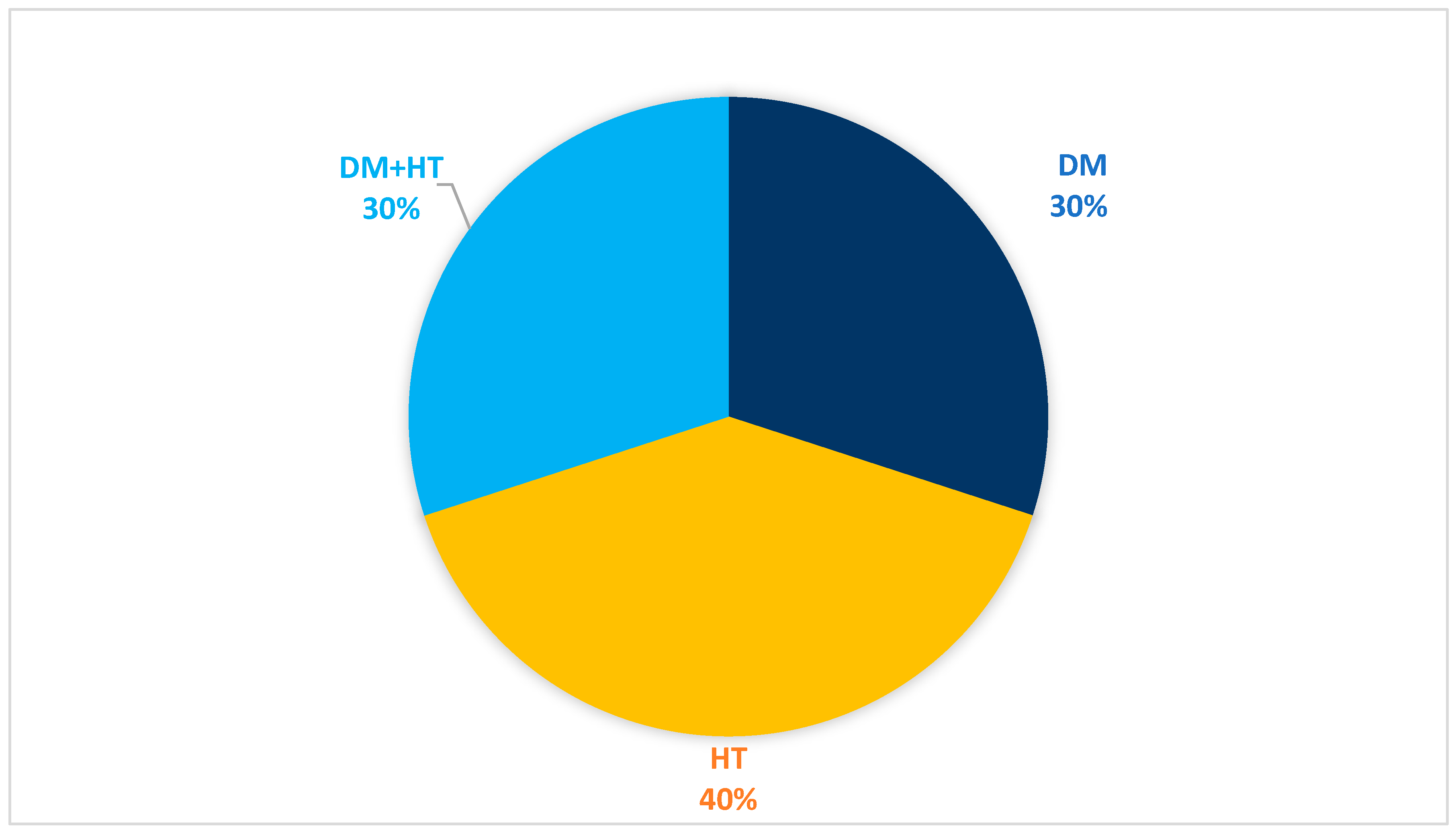

Past medical history (PMH) was positive among 62 (81.58%) patients, with HT among 30 (39.47%) and DM among 47 (61.9%). Some patients 15 (19.73%) have both HT and DM.

Table 2.

3.2. Characteristic of the Eyes to be Treated

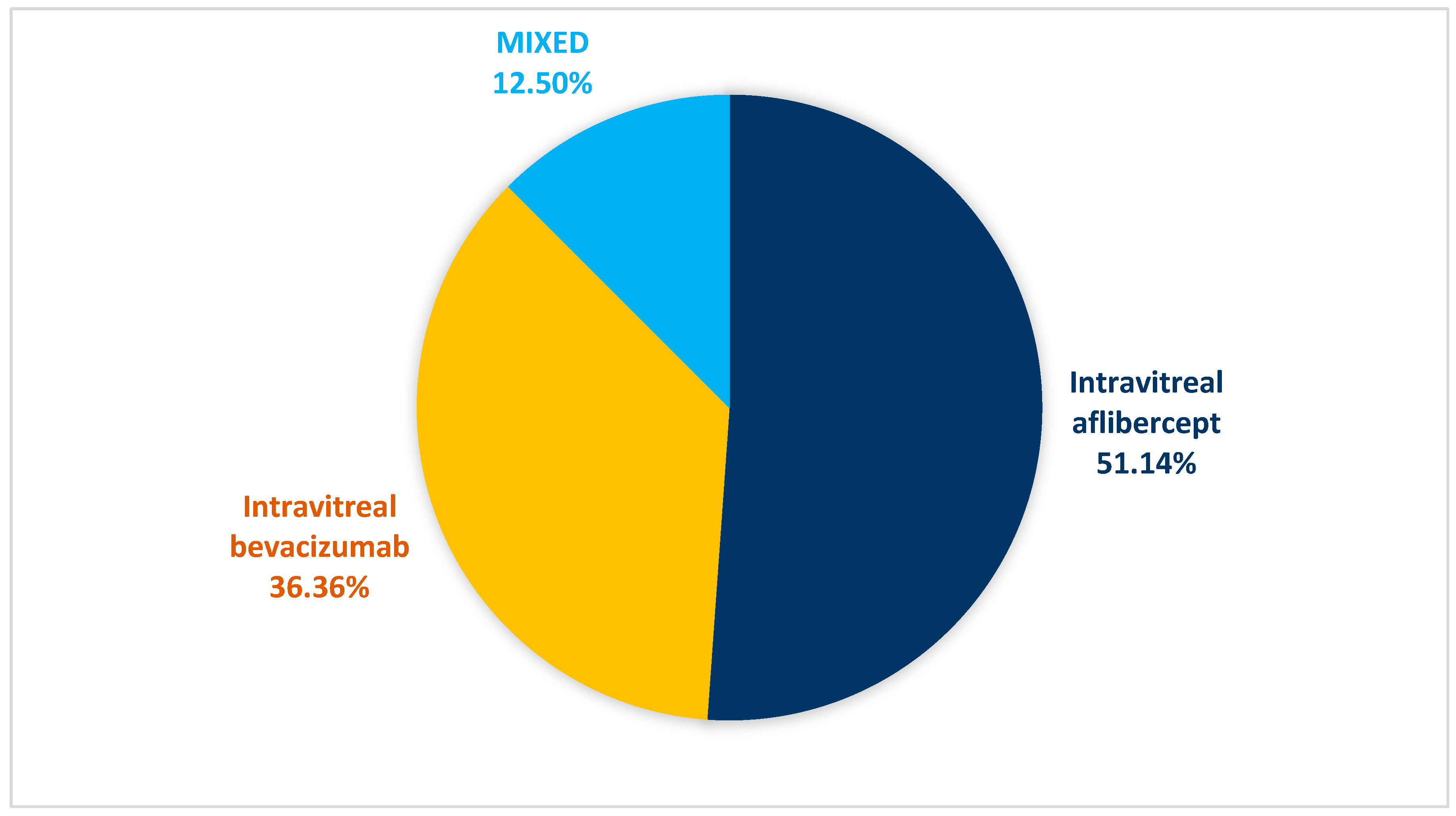

The study enrolled 88 eyes, 44 (50%) right and 44 (50%) left eyes, showed in

Table 3,

Figure 1. Previous anti-VEGF injection were Intravitreal aflibercept among 45 (51.14%) eyes, Intravitreal bevacizumab among 32 (36.36%), and mix Intravitreal aflibercept and Intravitreal bevacizumab among 11 (12.50%) eyes; with mean injections of 7.0±1.77 range between (5-12) in the past year.

Table 3,

Figure 2.

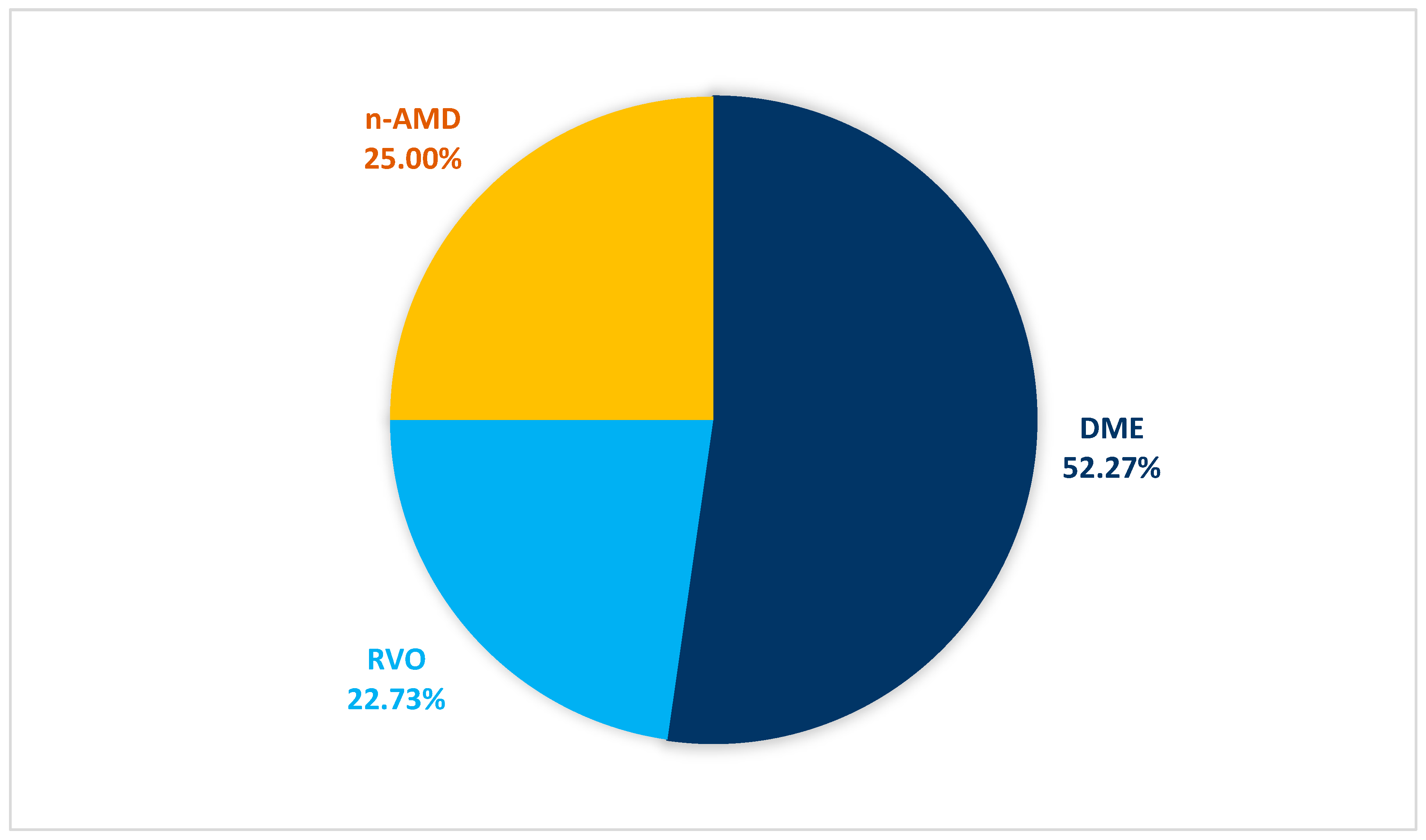

3.3. Ocular Diagnosis

Of the total 88 eyes treated with intravitreal faricimab, 46 (52.27%) eyes diagnosed with DME, 20 (22.73%) eyes diagnosed with RVO, and 22 (25.0%) eyes diagnosed with n-AMD.

Figure 3.

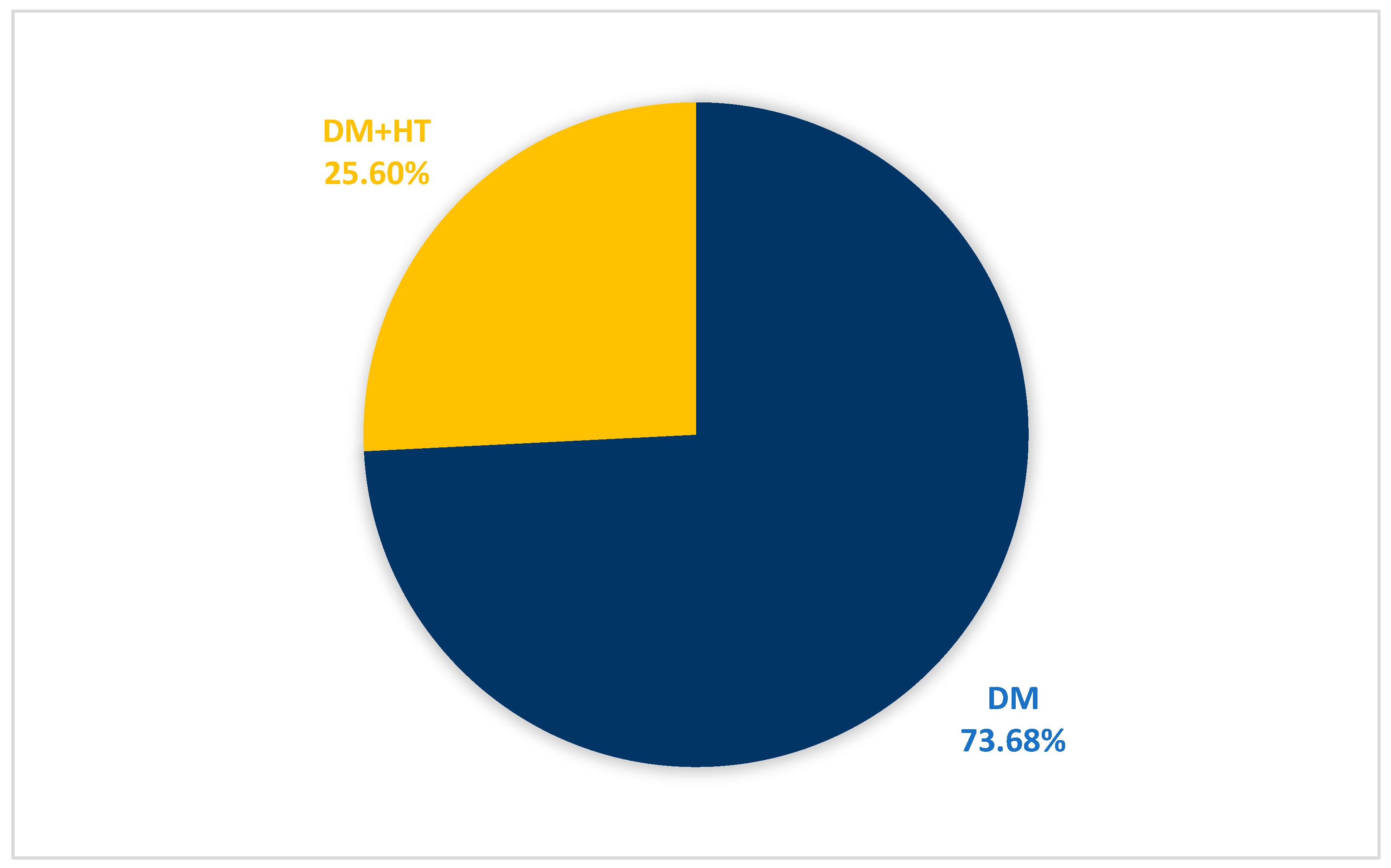

3.4. Demographic Data and Medical Background of Patients with DME

Patients diagnosed with DME had a mean age of 64.8 ± 7.9 years range between (54–80) with 17 (44.7%) cases ≥ 65 years and 21 (55.3%) cases < 65 years. All participants 38 (100%) had PMH, including DM in every case 38 (100%) and HT in 10 cases (25.6%), with this subset having comorbid DM.

Table 4,

Figure 4.

3.5. Clinical Parameters for Patients with DME

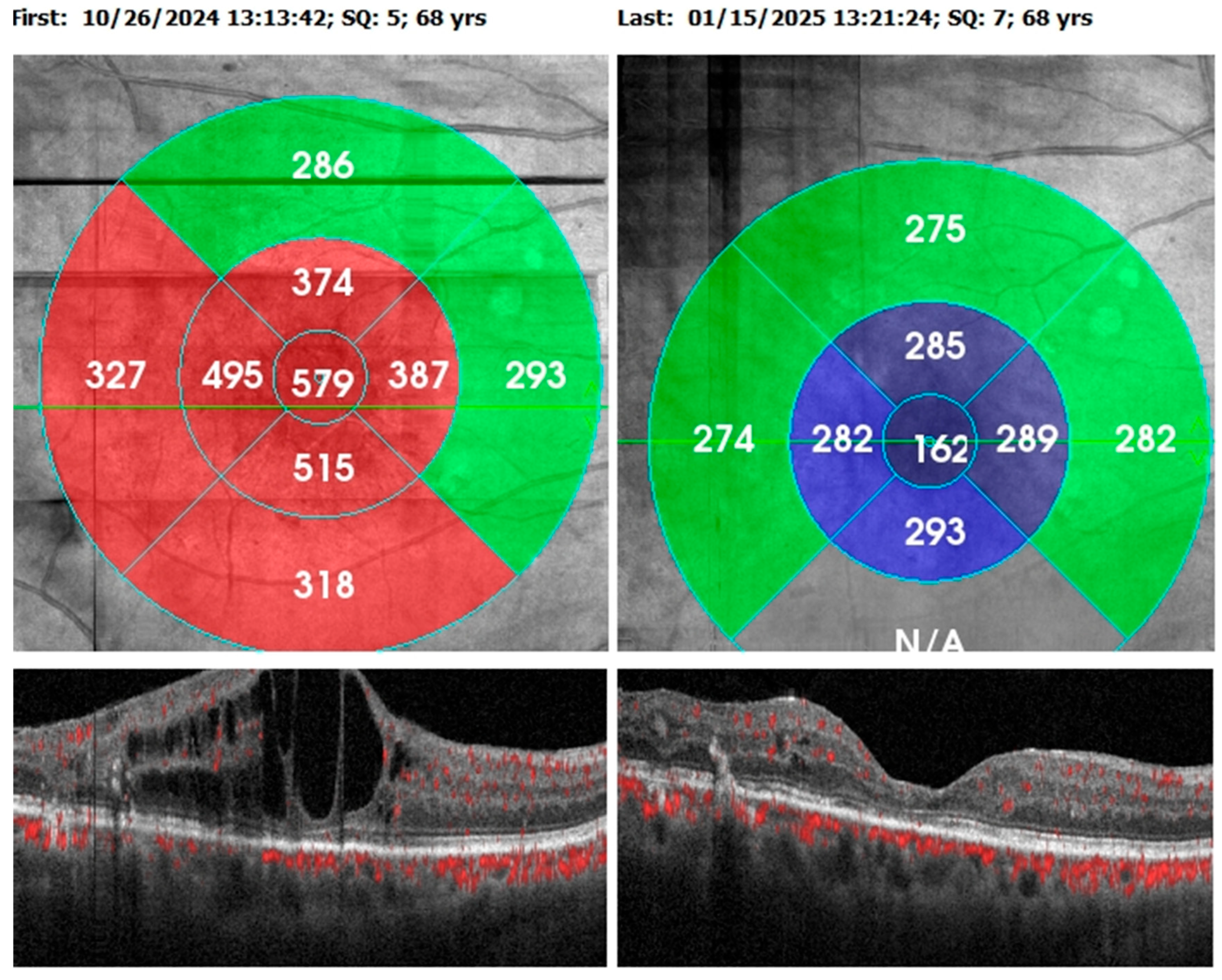

The comparison of clinical parameters before and after starting Faricimab was detailed in

Table 5. Example on the anatomical outcome showed in

Figure 5.

Visual acuity and central retinal thickness show a significant improvement (P<0.001). The mean visual acuity reduced from 0.60 (SD±0.24) to 0.44 (SD±0.24) and mean central retinal thickness reduced from 464.74 (SD±112.99) to 288.5 (SD±85.04), 1 month after the third faricimab injection.

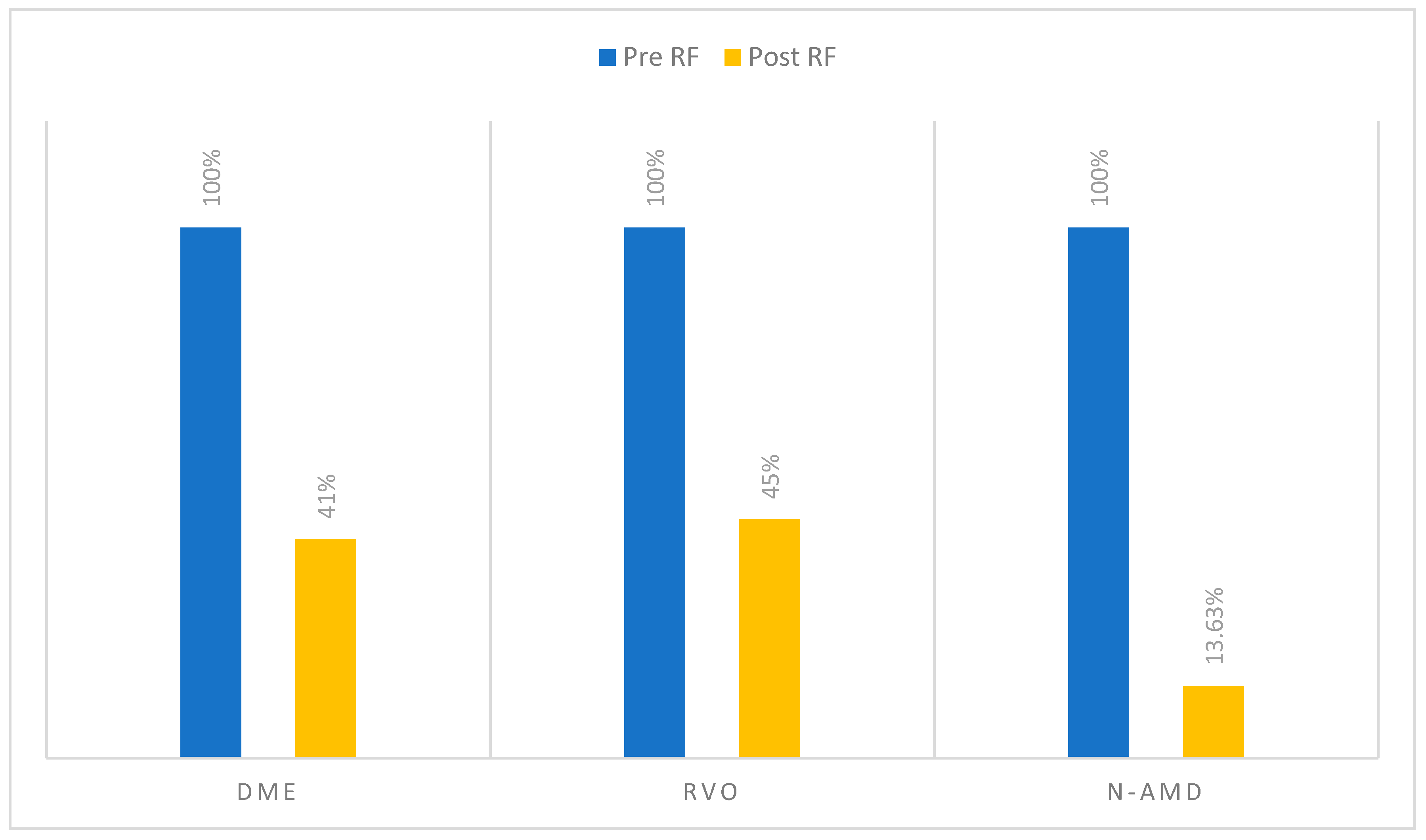

Intraretinal fluid and subretinal fluid show significant reduction (P<0.001). The proportion of eyes with SRF decreased from 15 (32.60%) pretreatment to 2 (4.34%) posttreatment, while the proportion of eyes with IRF decreased from 46 (100%) to 19 (41.30%). Intraocular pressure remained stable over the course of the study (p=0.673).

Figure 5.

68-year-old female with diabetic macular edema with previous five intravitreal aflibercept injections with persistent CMO and IRF, and after three loading doses of Faricimab, the retina was dry, and visual acuity improved from 1 to 0.6.

Figure 5.

68-year-old female with diabetic macular edema with previous five intravitreal aflibercept injections with persistent CMO and IRF, and after three loading doses of Faricimab, the retina was dry, and visual acuity improved from 1 to 0.6.

Table 5.

comparison of clinical parameters before and after starting faricimab for patients with DME, No=46.

Table 5.

comparison of clinical parameters before and after starting faricimab for patients with DME, No=46.

| Parameters |

Pretreatment |

Posttreatment |

P* value |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| Visual Acuity LogMAR |

0.60 |

0.24 |

0.44 |

0.24 |

<0.001 |

| Intraocular Pressure |

15.64 |

2.20 |

15.57 |

2.54 |

0.673 |

| Central Retinal Thickness |

464.74 |

112.99 |

288.5 |

85.04 |

<0.001 |

| Parameters |

No.46 |

100% |

No.46 |

100% |

P^ value |

| Subretinal Fluid |

15 |

32.60% |

2 |

4.34% |

<0.001 |

| Intraretinal Fluid |

46 |

100% |

19 |

41.30% |

<0.001 |

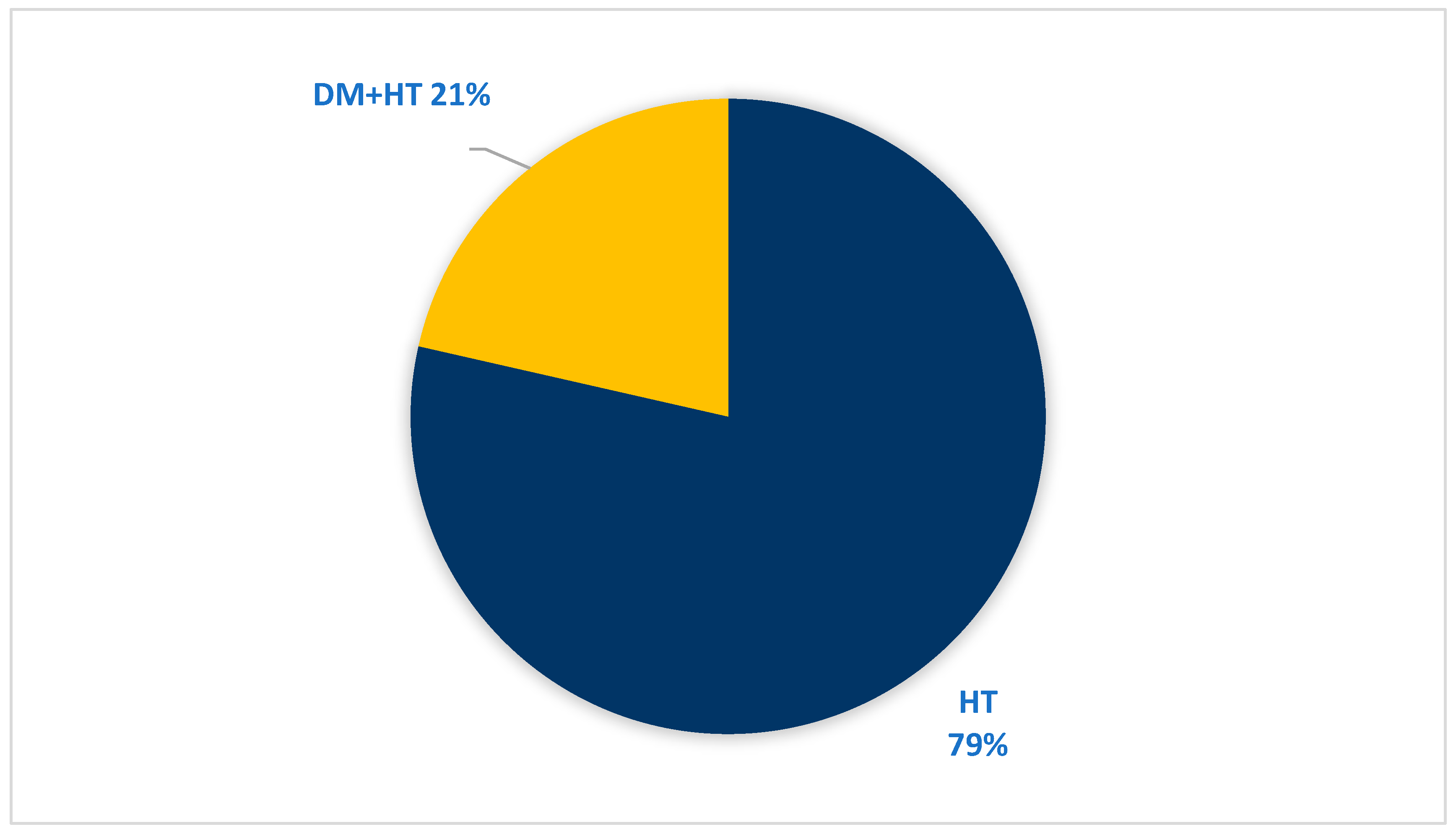

3.6. Demographic Data and Medical Background of Patients with RVO

The study included 19 patients diagnosed with RVO, with a mean age of 63.6±8.6 years range in between (46-76) with 8 case ≥ 65 years and 11 case < 65 years. PMH was positive in 14 patients (73.7%), including HT in 14 patients (73.7%) and DM in 3 patients (15.9%). From these patients 3 cases (15.9%) had both DM and HT. (

Table 6),

Figure 6.

3.7. Clinical Parameters for Patients with RVO

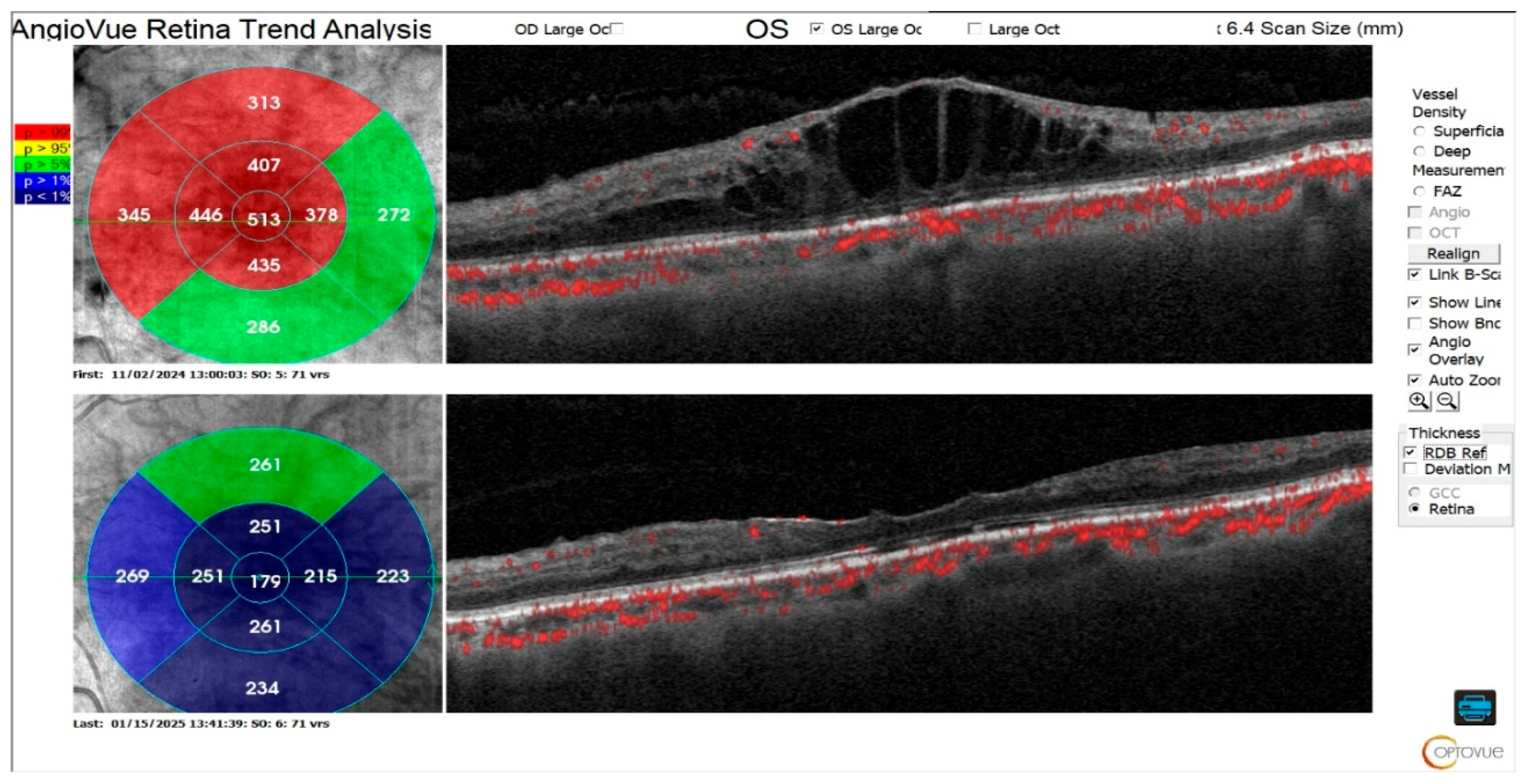

The comparison of clinical parameters before and after starting faricimab was detailed in

Table 7. Example on the anatomical outcome showed in

Figure 7.

Visual acuity and central retinal thickness show a significant improvement (P<0.001). The mean visual acuity reduced from 0.71 (SD±0.25) to 0.48 (SD±0.27) and mean central retinal thickness reduced from 534.3 (SD±144.79) to 324.45 (SD±88.30), 1 month after the third faricimab injection.

Intraretinal fluid and subretinal fluid show significant reduction (P<0.05). The proportion of eyes with SRF decreased from 10 (50%) pretreatment to 2 (10%) posttreatment, while the proportion of eyes with IRF decreased from 20 (100%) to 9 (45%). Intraocular pressure remained stable over the course of the study (p=0.408).

Table 7.

comparison of clinical parameters before and after starting faricimab for patients with RVO, No=20.

Table 7.

comparison of clinical parameters before and after starting faricimab for patients with RVO, No=20.

| Parameters |

Pretreatment |

Posttreatment |

P* value |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| Visual Acuity LogMAR |

0.71 |

0.25 |

0.48 |

0.27 |

<0.001 |

| Intraocular Pressure |

17.65 |

2.13 |

17.5 |

1.88 |

0.408 |

| Central Retinal Thickness |

534.3 |

144.79 |

324.45 |

88.30 |

<0.001 |

| Parameters |

No.20 |

100% |

No.20 |

100% |

P^ value |

| Subretinal Fluid |

10 |

50% |

2 |

10% |

0.015 |

| Intraretinal Fluid |

20 |

100% |

9 |

45% |

0.002 |

Figure 7.

71-year-old female presented with CRVO and previous five intravitreal aflibercept 2mg and four intravitreal Bevacizumab with CMO and switched to three loading doses of Faricimab with disappearance of IRF and SRF, but visual acuity remained one due to damage in photoreceptors.

Figure 7.

71-year-old female presented with CRVO and previous five intravitreal aflibercept 2mg and four intravitreal Bevacizumab with CMO and switched to three loading doses of Faricimab with disappearance of IRF and SRF, but visual acuity remained one due to damage in photoreceptors.

3.8. Demographic Data and Medical Background of Patients with n-AMD

The study included 19 patients diagnosed with n-AMD, with a mean age of years range between (61-83) with 18 (94.7%) case ≥ 65 years and 1 (5.3%) case < 65 years. PMH was positive in 10 patients (52.6%), including HT in 7 patients (36.8%) and DM in 6 patients (31.6%). From these patients 2 cases (10.5%) had both DM and HT. (

Table 8),

Figure 8.

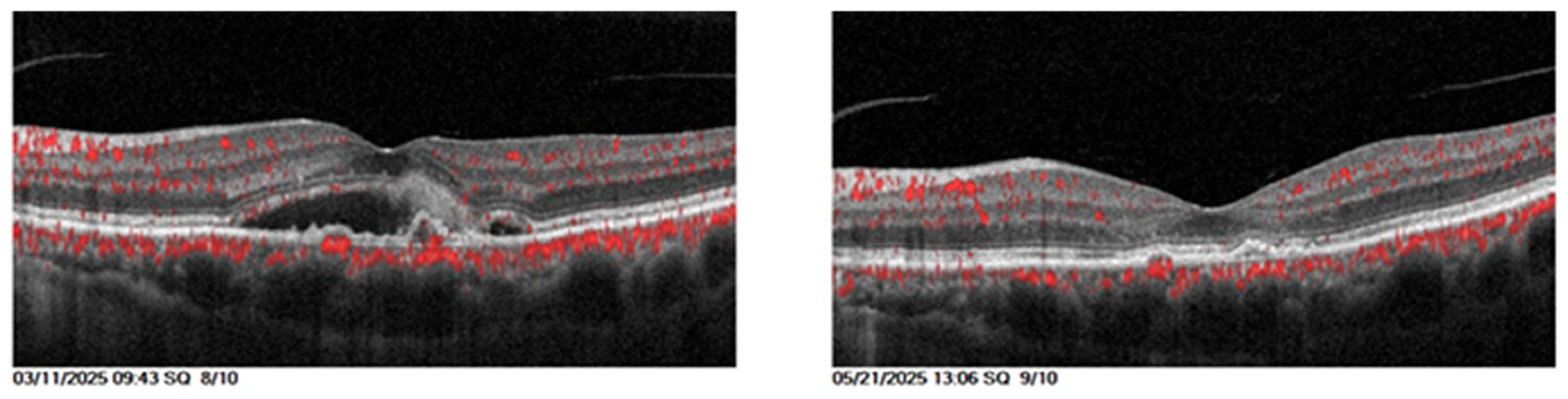

3.9. Clinical Parameters for Patients with n-AMD

The comparison of clinical parameters before and after starting faricimab was detailed in

Table 9. Example on the anatomical outcome showed in

Figure 9.

Visual acuity and central retinal thickness show a significant improvement (P<0.001). The mean visual acuity reduced from 0.63 (SD±0.18) to 0.39 (SD±0.28) and mean central retinal thickness reduced from 411.23 (SD±78.99) to 268.73 (SD±58.13), 1 month after the third faricimab injection.

Intraretinal fluid and subretinal fluid show significant reduction (P<0.05). The proportion of eyes with SRF decreased from 22 (100%) pretreatment to 3 (13.63%) posttreatment, while the proportion of eyes with IRF decreased from 6 (27.27%) to 0 (0%). Intraocular pressure remained stable over the course of the study (p=0.35).

Table 9.

comparison of clinical parameters before and after starting faricimab for patients with n-AMD, No=46.

Table 9.

comparison of clinical parameters before and after starting faricimab for patients with n-AMD, No=46.

| Parameters |

Pretreatment |

Posttreatment |

P* value |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| Visual Acuity LogMAR |

0.63 |

0.18 |

0.39 |

0.28 |

<0.001 |

| Intraocular Pressure |

14.64 |

2.44 |

14.91 |

2.83 |

0.216 |

| Central Retinal Thickness |

411.23 |

78.99 |

268.73 |

58.13 |

<0.001 |

| Pigmented epithelial detachment |

176.91 |

225.71 |

68.91 |

100.94 |

0.007 |

| Parameters |

No.22 |

100% |

No.22 |

100% |

P^ value |

| Subretinal Fluid |

22 |

100% |

3 |

13.63% |

<0.001 |

| Intraretinal Fluid |

6 |

27.27% |

0 |

0% |

<0.05 |

Figure 9.

67-year-old male with wet AMD treated previously with 5 intravitreal Bevacizumab injections with no response and switched to Faricimab, and OCT shows that after the three loading doses, subretinal fluid disappeared with visual acuity improved from 0.5 to 0.3.

Figure 9.

67-year-old male with wet AMD treated previously with 5 intravitreal Bevacizumab injections with no response and switched to Faricimab, and OCT shows that after the three loading doses, subretinal fluid disappeared with visual acuity improved from 0.5 to 0.3.

3.10. Retinal fluid

In all three diagnostic groups, the baseline proportion of patients exhibiting retinal fluid (IRF and/or SRF) was 100%. Following treatment, a substantial proportion of patients achieved complete retinal dryness, approximately 59% in DME, 55% in RVO, and 86.37% in n-AMD.

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

4. Discussion

4.1. Patient Demographics and Background

The study included 88 eyes from 76 patients, with a mean age of 66.14±8.678 years and about 56.57% of cases ≥ 65 years, indicating a strong correlation between RVD and aging. This finding aligns closely with a study conducted in Nepal, which reported a high prevalence (52.37%) of retinal abnormalities among individuals aged 60 years and older, with a mean age of 69.64 ± 7.31 years [

11]. Minor difference in the female-to-male ratio (1.05:1) is consistent with the analysis reported by Shafiee, A., Juran, T [

12].

A considerable proportion of patients had pre-existing health issues (81.6%), predominantly DM (61.84%), and HT (39.47%) with some patients have both HT and DM (19.7%), these comorbidities are prevalent in populations with RVD. DM is the primary cause of DR and HT plays a role in the development and progression of DR as well as RVO [

13].

Of the 88 eyes treated with intravitreal faricimab, 46 eyes (52.27%) had refractory DME, 22 eyes (25.00%) had refractory n-AMD and 20 eyes (22.73%) had refractory RVO. The distribution reflects the spectrum of anti-VEGF-resistant macular edema encountered in routine clinical practice. These data indicate that DME patient most likely to develop anti-VEGF resistance followed by those with n-AMD and RVO. 44% of patients with DME show persistent retinal fluid on OCT, Even after 2 years receiving aflibercept medication [

14]. In case of AMD, about 19.7% and 36.6% of patients who had aflibercept treatment every 4 and 8 weeks for a year, respectively, continued to have active exudation [

15]. For RVO the results of clinical trials and clinical practice differ, which suggests that anti-VEGF may not be sufficient to completely treat this illness [

16].

All patients had received multiple prior intravitreal injections of bevacizumab and/or aflibercept (mean 7 injections, range 5–12), administered as part of a standard loading regimen, with assessment of response 4–6 weeks after the last injection. This baseline profile highlights the complexity of managing refractory RVD and the need for alternative therapeutic strategies in this population.

4.2. Best Corrected Visual Acuity

For patients with DME, this study demonstrates a significant improvement in VA after switching to Faricimab (P<0.001), with mean VA improved to o.44 from o.60, corresponding to gain of approximately 8 EDTR letter. This finding aligns with real-world data reported by Rush RB [

17] but different from Deiters V.’s study that reported stable visual function with a negligible tendency for improvement. [

18]

For patients with RVO, VA show significant improvement (P<0.001), with mean VA reduced from 0.71 to 0.48, indicating that the applied therapeutic technique was successful in improving patient sight (>10 EDTR). [

19] The significant improvement in VA is consistent with faricimab’s dual mode of action, which targets both Ang-2 and VEGF to address the complex pathophysiology of RVO [

20].

For eyes diagnosed with n-AMD, treatment switching is a standard strategy to address nonresponse [

21]. Information on VA for patients with n-AMD varies widely in the literatures. Some authors have documented improvement [

22] other documented stability [

23], while worsening is sometimes observed [

24]. The main causes of this could be different inclusion and exclusion criteria, and different lengths of prior anti-VEGF treatment. In the current study, the mean visual acuity of individuals with n-AMD improved significantly from 0.63 to 0.39 (P<0.001), corresponding to gain of >10 EDTR letter.

4.3. Anatomical Outcomes

For patients with DME, the anatomical function of the eye shows significant improvement represented by significant reduction in CRT, IRF and SRF. Patients with refractory DME who transitioned from aflibercept to faricimab demonstrated a notable improvements in CRT when compared to those who continued aflibercept medication with 37.5% of the patients had a CRT < 300 µm after switching to faricimab [

17]. IRF usually reacts favorably to anti-VEGF treatment. [

25] In this study IRF was detected in (100%) eyes in patients with DME at baseline. Following the administration of three loading doses of faricimab, (47.82%) of patients achieved complete dryness, while the remaining patients showed a considerable reduction in intraretinal fluid. These findings align with YOSEMITE and RHINE trials, 98.7% to 99.0% of eyes exhibited IRF at baseline. Two years later, IRF resolution was attained in 44–49% of the T&E group and 58–63% of the Q8W group. [

26]

For patients diagnosed with RVO, the current study result shows a considerable morphological improvement exhibited as significant reduction in CRT (mean -209.85, p<0.001) and IRF (p=0.002). IRF dryness is seen in half of the patients and the other half have significant fluid loss. 40% of eyes experience complete SRF dryness. Additionally according to the BALATON and COMINO investigations, Faricimab caused a rapid and significant decrease in retinal fluid from the baseline in patients with RVO, as seen by the decrease in CRT [

19].

In the current study, faricimab improve anatomic function of the n-AMD patient eyes, with a notable CRT mean reduction (-142.5) (p<0.001), considerable proportion of patient (86.37%) without SRF, and no patient with IRF following faricimab. These finding suggest that faricimab Ang-2 and VEGF-A inhibition combination improve the drying anatomical outcomes beyond VEGF-A inhibition alone. [

18] According to earlier research, faricimab effectively improves anatomical outcomes following a transition from other medications. [

19,

27] These anatomical results are in line with a number of other real-world faricimab outcome studies in eyes that have already received treatment for n-AMD. [

23,

28,

29] This study indicates that PED severity has decreased because faricimab counteracts the primary mechanisms behind the development of PEDs. [

4,

30]

One of the primary markers of therapy response in our study was complete retinal fluid resolution, which is demonstrated by the absence of any detectable fluid (IRF and SRF). Compared to the DME and RVO (58.7% and 55% of the eyes achieving a totally dry retina), the n-AMD population had a considerably higher percentage of eyes that achieved complete retinal fluid resolution (86.73% of the eyes reaching the endpoint). As of right now, we cannot adequately explain this variation in anatomical response. It may be connected to a slower reaction in diabetic eyes, which may require further injections to completely recede the fluid. However, four injections are insufficient to determine the appropriate response to a particular anti-VEGF therapy. Some individuals may require six or more injections to achieve the desired results, according to several studies [

25]. We cannot rule out the possibility that eyes with DME included in our trial will eventually see a full anatomical response following further injections.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) remained stable during follow-up in all groups. The observed pattern of transient IOP elevation immediately after injection, with rapid normalization to below 21 mmHg within minutes, is consistent with previous reports for other intravitreal anti-VEGF agents. No cases of endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, or other serious ocular complications were recorded during the study period. [

31].

The goal of the current investigation was to determine the short-term effects of a loading dosage rather than to evaluate the long-term response to faricimab. Therefore, there is no correlation between early reaction and our patients’ long-term prognosis. To clarify this point, a research extension is required. Our study demonstrates the effectiveness of faricimab in patients who had previously failed several lines of treatment in a practical context. Real-world investigations, as opposed to controlled clinical trials, frequently include a more varied patient group with a range of comorbidities and illness severity. [

32] This increases the therapeutic significance of results and sheds light on how faricimab is actually used in complicated situations.

5. Conclusions

In this study, eyes with diabetic macular edema, retinal vein occlusion edema, and neovascular age-related macular degeneration showed statistically significant improvements in both morphological and functional characteristics after switching to intravitreal Faricimab treatment for patients with persistent or refractory macular edema showing that Faricimab is a promising treatment option, particularly for those patients.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration 115 of Helsinki, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of College of Medicine / University of Baghdad (03.37/2025).

Consent of Publication

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to sincerely acknowledge and thank JENNA OPHTHALMIC CENTER group for their valuable assistance and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this article:

| Ang2 |

angiopoietin |

| BCVA |

best corrected visual acuity |

| CRT |

central retinal thickness |

| DME |

diabetic macular edema |

| DM |

diabetes mellitus |

| EDTR |

Early treatment diabetic retinopathy study |

| HT |

hypertension |

| IOP |

intraocular pressure |

| IRF |

intraretinal fluid |

| n-AMD |

neovascular age related macular degeneration |

| OCTA |

optical coherence tomography angiography |

| PED |

pigmented epithelial detachment |

| PMH |

past medical history |

| RVO |

retinal vein occlusion edema |

| SD |

standard deviation |

| SD-OCT |

spectral domain optical coherence tomography |

| SRF |

subretinal fluid |

| VA |

visual acuity |

| VEGF |

vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Panos, G.D., et al., Faricimab: transforming the future of macular diseases treatment-a comprehensive review of clinical studies. Drug design, development and therapy, 2023: p. 2861-2873. [CrossRef]

- Weis, S.M. and D.A. Cheresh, Pathophysiological consequences of VEGF-induced vascular permeability. Nature, 2005. 437(7058): p. 497-504. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J., et al., Targeting VE-PTP activates TIE2 and stabilizes the ocular vasculature. The Journal of clinical investigation, 2014. 124(10): p. 4564-4576. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.M., et al., Tie-2/Angiopoietin pathway modulation as a therapeutic strategy for retinal disease. Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 2019. 28(10): p. 861-869. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R., S.K. Gupta, and S. Agrawal, Efficacy and safety analysis of intravitreal bio-similar products of bevacizumab in patients with macular edema because of retinal diseases. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, 2023. 71(5): p. 2066-2070. [CrossRef]

- Fogli, S., et al., Clinical pharmacology of intravitreal anti-VEGF drugs. Eye, 2018. 32(6): p. 1010-1020. [CrossRef]

- Platania, C.B., et al., Molecular features of interaction between VEGFA and anti-angiogenic drugs used in retinal diseases: a computational approach. Frontiers in pharmacology, 2015. 6: p. 248. [CrossRef]

- Yerramothu, P., New Therapies of Neovascular AMD—Beyond Anti-VEGFs. Vision, 2018. 2(3): p. 31. [CrossRef]

- Bressler, N.M., et al., Biosimilars of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for ophthalmic diseases: A review. Survey of ophthalmology, 2024. 69(4): p. 521-538. [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.A., A.P. Finn, and P. Sternberg Jr, Spotlight on faricimab in the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration: design, development and place in therapy. Drug Design, Development and Therapy, 2022: p. 3395-3400. [CrossRef]

- Thapa, R., et al., Prevalence, pattern and risk factors of retinal diseases among an elderly population in Nepal: the bhaktapur retina study. Clinical Ophthalmology, 2020: p. 2109-2118. [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, A., et al., Racial and Gender Disparities in Clinical Trial Representation for Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical & Translational Ophthalmology, 2025. 3(3): p. 16. [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Afriyie, B., et al., Prevalence of risk factors of retinal diseases among patients in Madang Province, Papua New Guinea. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 2022. 2022(1): p. 6120908. [CrossRef]

- Rush, R.B. and S.W. Rush, Faricimab for treatment-resistant diabetic macular edema. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ), 2022. 16: p. 2797. [CrossRef]

- Machida, A., et al., Factors Associated with Success of Switching to Faricimab for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Refractory to Intravitreal Aflibercept. Life, 2024. 14(4): p. 476. [CrossRef]

- Nichani, P.A., et al., Efficacy and safety of intravitreal faricimab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration, diabetic macular edema, and retinal vein occlusion: A meta-analysis. Ophthalmologica, 2024. 247(5-6): p. 355-372. [CrossRef]

- Rush, R.B., One year results of faricimab for aflibercept-resistant diabetic macular edema. Clinical Ophthalmology, 2023: p. 2397-2403. [CrossRef]

- Deiters, V., et al., Real-World Data on Morphological and Functional Responses After Switching to Faricimab in Recalcitrant, Chronic Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology and Therapy, 2025: p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Hattenbach, L.-O., et al., BALATON and COMINO: phase III randomized clinical trials of faricimab for retinal vein occlusion: study design and rationale. Ophthalmology Science, 2023. 3(3): p. 100302.

- Hafner, M., et al., Switching to Faricimab in Therapy-Resistant Macular Edema Due to Retinal Vein Occlusion: Initial Real-World Efficacy Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2025. 14(7): p. 2454. [CrossRef]

- Löw, K., et al., Real-Life Treatment Intervals and Morphological Outcomes Following the Switch to Faricimab Therapy in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 2025. 15(5): p. 189. [CrossRef]

- Rush, R.B., One-year outcomes of faricimab treatment for aflibercept-resistant neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Clinical Ophthalmology, 2023: p. 2201-2208. [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, R., et al., Outcomes of treatment-resistant neovascular age-related macular degeneration switched from aflibercept to faricimab. Ophthalmology Retina, 2024. 8(6): p. 537-544. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M., et al., Short-term outcomes of treatment switch to faricimab in patients with aflibercept-resistant neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 2024. 262(7): p. 2153-2162. [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.R., et al., Measurements of retinal fluid by optical coherence tomography leakage in diabetic macular edema: a biomarker of visual acuity response to treatment. Retina, 2019. 39(1): p. 52-60.

- Lim, J.I., et al., Anatomic Control with Faricimab versus Aflibercept in the YOSEMITE/RHINE Trials in Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology Retina, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.Y., et al., Real-world 1-year outcomes of treatment-intensive neovascular age-related macular degeneration switched to faricimab. Ophthalmology Retina, 2025. 9(1): p. 22-30. [CrossRef]

- Szigiato, A., et al., Short-term outcomes of faricimab in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration on prior anti-VEGF therapy. Ophthalmology Retina, 2024. 8(1): p. 10-17. [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.A., et al., Clinical outcomes of faricimab in patients with previously treated neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology Retina, 2024. 8(4): p. 360-366. [CrossRef]

- Yen, W.-T., et al., Efficacy and safety of intravitreal faricimab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 2024. 14(1): p. 2485. [CrossRef]

- Hoguet, A., et al., The effect of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents on intraocular pressure and glaucoma: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology, 2019. 126(4): p. 611-622.

- Callizo, J., et al., Real-world data: ranibizumab treatment for retinal vein occlusion in the OCEAN study. Clinical Ophthalmology, 2019: p. 2167-2179. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).