Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

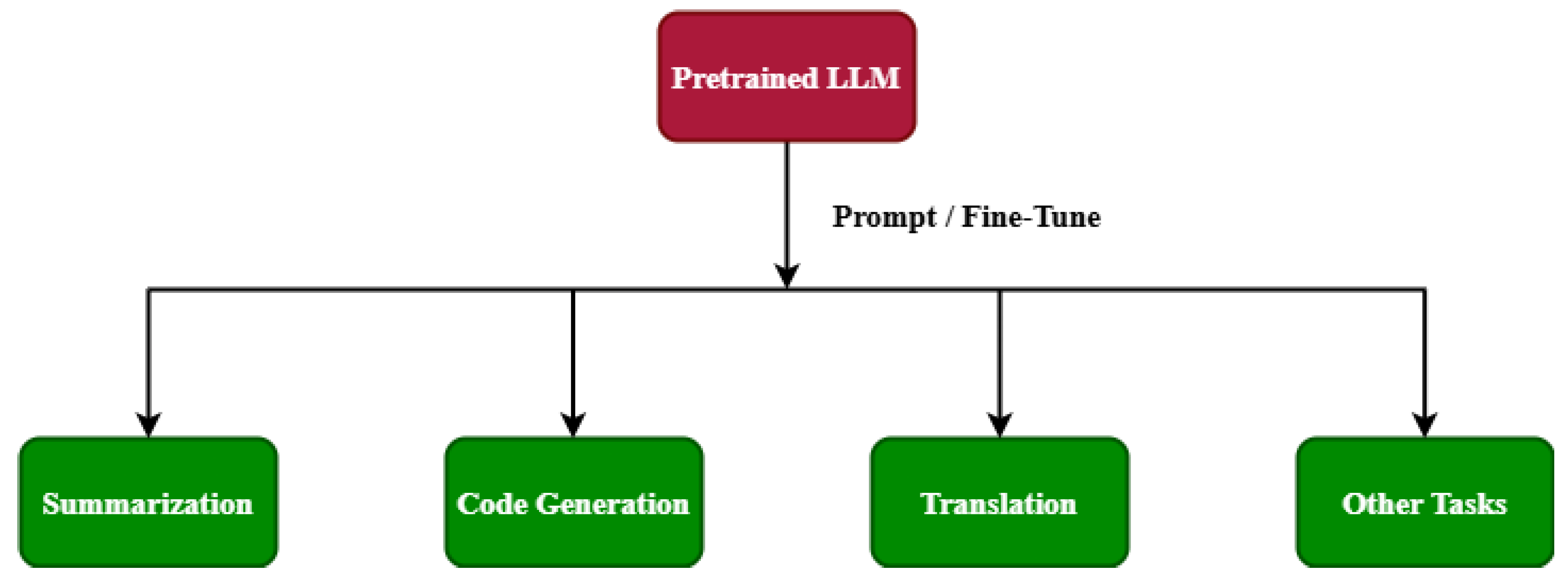

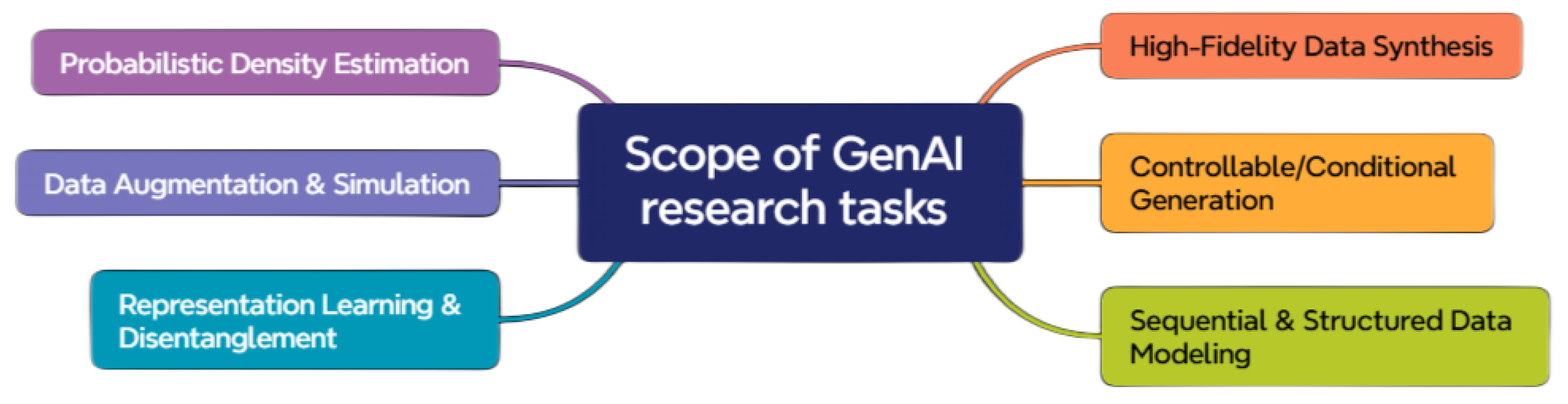

2. A Pragmatic Taxonomy of Generative Tasks

2.1. Key Generative Research Tasks

2.2. Core Generative Paradigms

2.3. Evaluation Criteria from a Researcher’s Perspective

- Sample Quality: Assesses the fidelity, coherence, and realism of generated outputs using metrics such as Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) [29], Inception Score (IS), and domain-specific evaluations.

- Sample Diversity: Measures the model’s ability to capture a wide range of data modes and intra-class variations, indicating robustness against mode collapse.

- Controllability: Evaluates how effectively a model responds to conditioning inputs, supports fine-grained control, and generalizes to zero-shot scenarios.

- Computational Budget: Accounts for training and inference efficiency, including FLOPs, GPU memory usage, latency, and overall computational cost.

- Likelihood Estimation: Considers the availability, tractability, and accuracy of estimating the data likelihood , which is crucial for probabilistic interpretability [30].

- Latent Space Utility: Examines the structure and semantics of the latent space, focusing on interpretability, smoothness, and potential for disentangled representations.

- Training Dynamics: Reviews the stability and scalability of the training process, including convergence speed, sensitivity to hyperparameters, and adaptability to various scales. Table 2 provides information about Evaluation Criteria for Generative Models.

3. Task-Driven Analysis

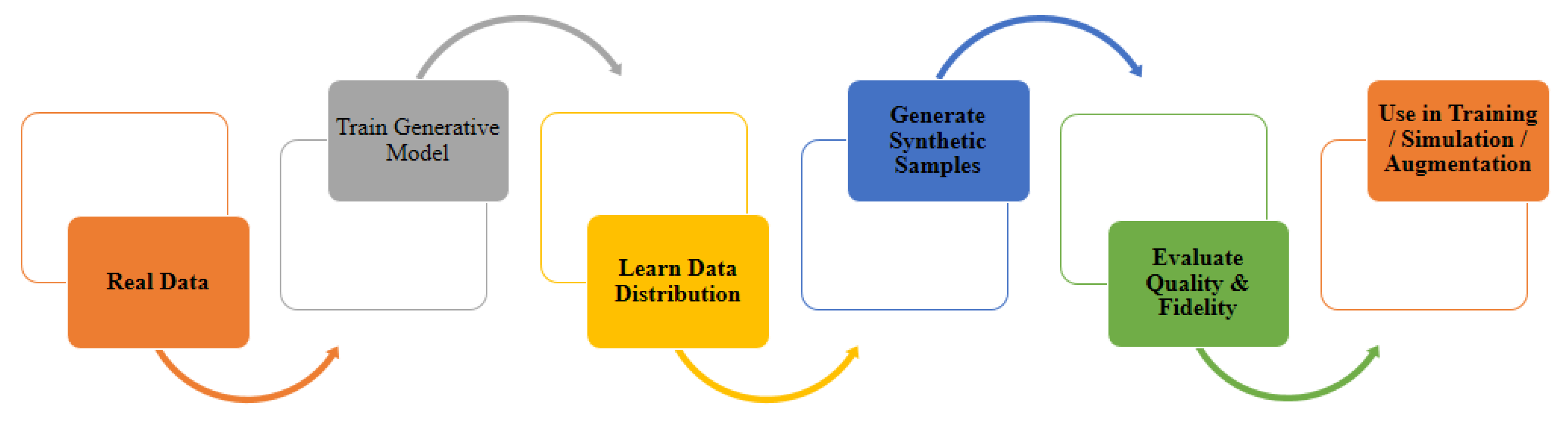

3.1. High-Fidelity Data Synthesis

3.2. Controllable & Conditional Generation

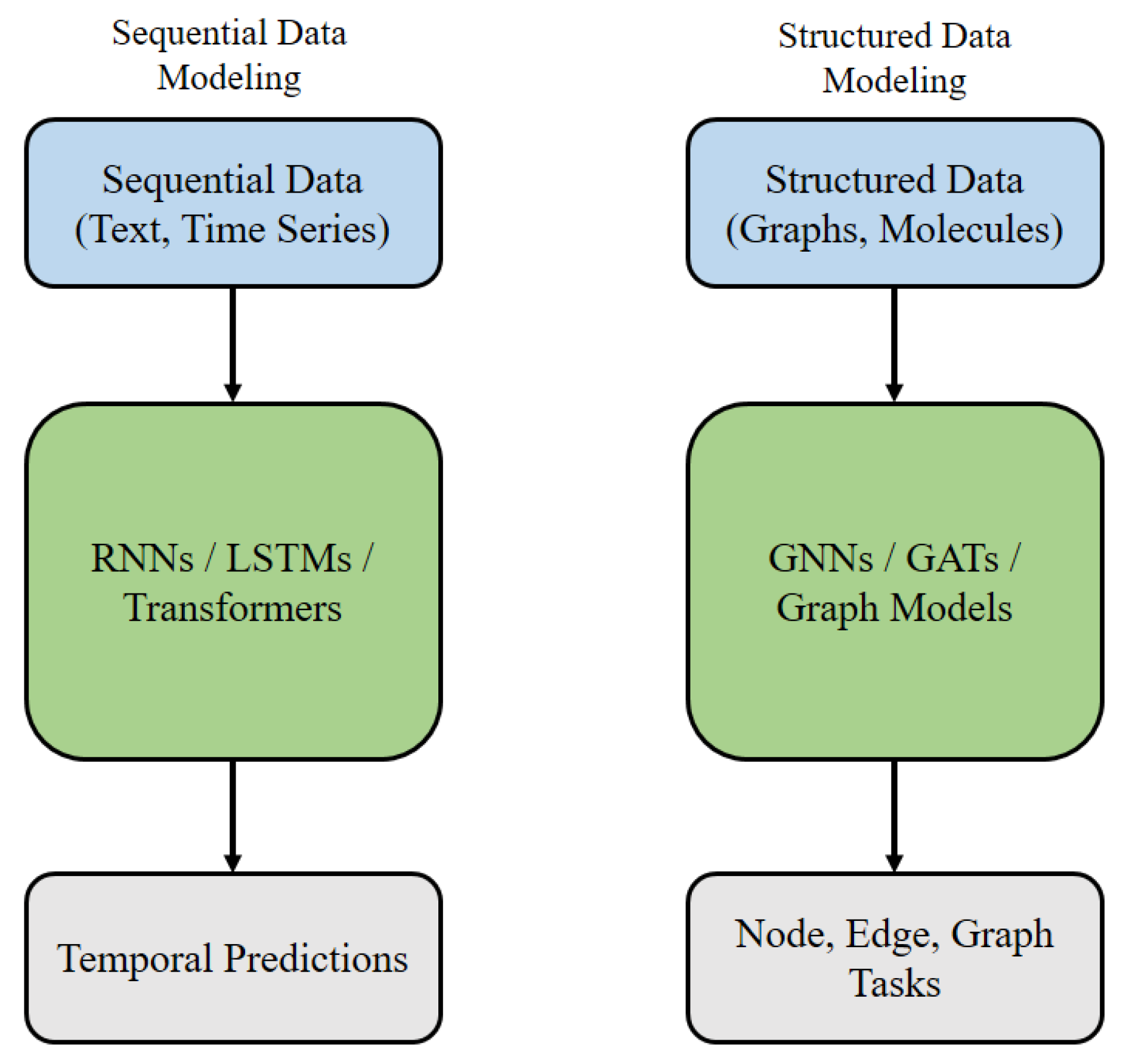

3.3. Sequential & Structured Data Modeling:

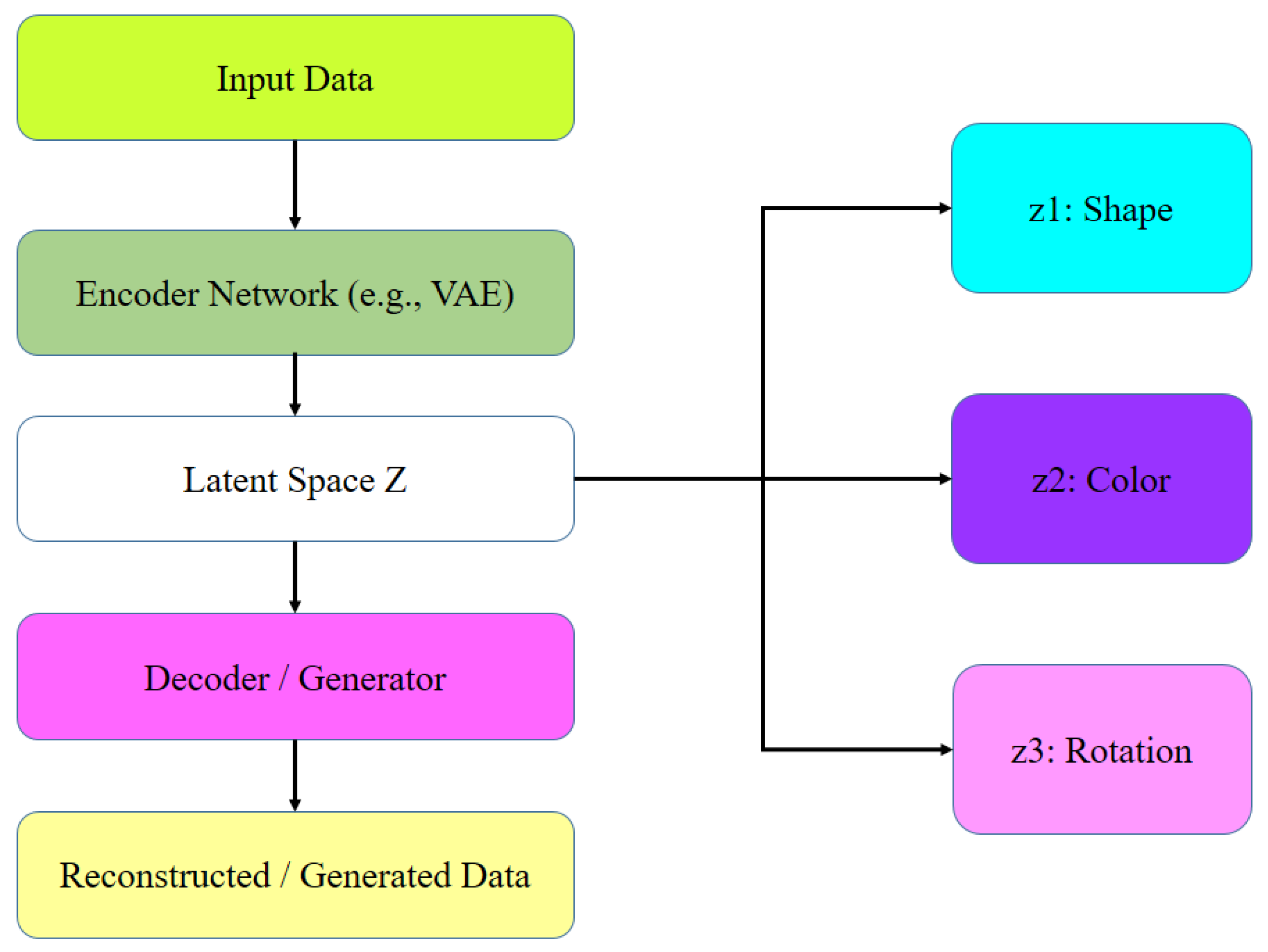

3.4. Representation Learning & Disentanglement

3.5. Data Augmentation & Simulation

3.6. Probabilistic Density Estimation:

4. Advancing & Cross-cutting Best Practices

4.1. Technical Strategies Beyond Basic Fine-Tuning

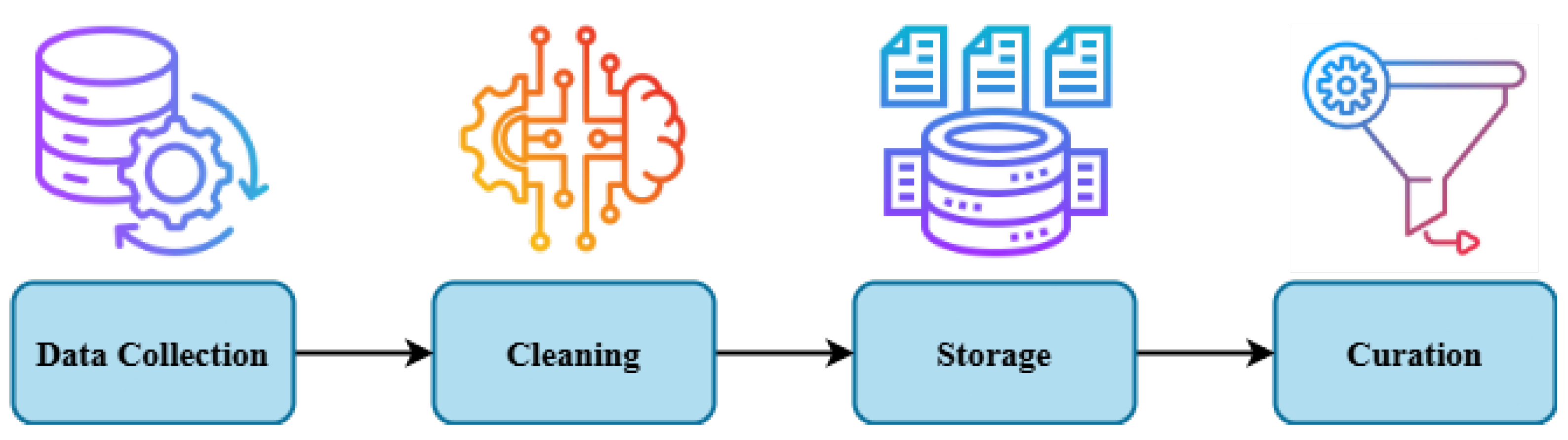

4.2. Data Engineering & Curation

4.3. Technical Aspects of Large-Scale Data Handling

4.4. Computational Efficiency & Scaling

4.5. Debugging, Reproducibility & Evaluation Toolkits

4.6. Responsible AI (Technical Implementations)

5. Technical Challenges & Future Directions

5.1. Key Open Problems

5.2. Focus on Technical Methods

6. Conclusions

References

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; et al. Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2020; Vol. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Dhariwal, P.; Nichol, A. Diffusion Models Beat GANs on Image Synthesis. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2021; Vol. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2014, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aittala, M.; Hellsten, J.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Analyzing and Improving the Image Quality of StyleGAN. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020; pp. 8110–8119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional Generative Adversarial Nets. arXiv preprint 2014, arXiv:1411.1784 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, K.; Lee, H.; Yan, X. Learning Structured Output Representation using Deep Conditional Generative Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2015; Vol. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, A.; Dhariwal, P.; Nichol, A.; Chu, C.; Chen, M. Zero-Shot Text-to-Image Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Salimans, T.; Gritsenko, A.; Chan, W.; Norouzi, M.; Fleet, D.J. Video Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave, D.; Cho, K.; Oh, A., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc; 2022; Vol. 35, pp. 8633–8646. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol, A.; Dhariwal, P.; Ramesh, A.; Shyam, P.; Poole, B.; McGrew, B.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, M. GLIDE: Towards Photorealistic Image Generation and Editing with Text-Guided Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Elman, J.L. Finding Structure in Time. Cognitive Science 1990, 14, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Łukasz, K.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Vincent, P. Representation Learning: A Review and New Perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2013, 35, 1798–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y. Deep Learning of Representations for Unsupervised and Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ICML Workshop on Unsupervised and Transfer Learning; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, I.; Matthey, L.; Pal, A.; Burgess, C.; Glorot, X.; Botvinick, M.; Mohamed, S.; Lerchner, A. beta-VAE: Learning Basic Visual Concepts with a Constrained Variational Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Duan, Y.; Houthooft, R.; Schulman, J.; Sutskever, I.; Abbeel, P. InfoGAN: Interpretable Representation Learning by Information Maximizing Generative Adversarial Nets. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. Journal of Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, J.; Fong, R.; Ray, A.; Schneider, J.; Zaremba, W.; Abbeel, P. Domain Randomization for Transferring Deep Neural Networks from Simulation to the Real World. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE; 2017; pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, L.; Wang, J. The Effectiveness of Data Augmentation in Image Classification using Deep Learning. arXiv preprint 2017, arXiv:1712.04621 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan, G.J.; Peel, D. Finite Mixture Models; John Wiley & Sons, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Papamakarios, G.; Nalisnick, E.; Rezende, D.J.; Mohamed, S.; Lakshminarayanan, B. Normalizing Flows for Probabilistic Modeling and Inference. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2021, 22, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- van den Oord, A.; Kalchbrenner, N.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Pixel Recurrent Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rezende, D.; Mohamed, S. Variational inference with normalizing flows. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2015; pp. 1530–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar]

- Heusel, M.; Ramsauer, H.; Unterthiner, T.; Nessler, B.; Hochreiter, S. GANs Trained by a Two Time-Scale Update Rule Converge to a Local Nash Equilibrium. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2017; pp. 6626–6637. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, L.; Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Bengio, S. Density Estimation using Real NVP. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Aittala, M.; Laine, S.; Härkönen, E.; Hellsten, J.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Alias-Free Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, E.R.; et al. Efficient Geometry-Aware 3D Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2206.05185 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tewari, A.; et al. State of the Art on Neural Rendering. Computer Graphics Forum 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Brox, T. Generating Images with Perceptual Similarity Metrics based on Deep Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Qiao, Y.; Loy, C.C. Real-ESRGAN: Training Real-World Blind Super-Resolution with Pure Synthetic Data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Heusel, M.; Ramsauer, H.; Unterthiner, T.; Nessler, B.; Hochreiter, S. GANs Trained by a Two Time-Scale Update Rule Converge to a Local Nash Equilibrium. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Salimans, T.; et al. Improved Techniques for Training GANs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Deep Features as a Perceptual Metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, A.; et al. Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2204.06125 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.11239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ermon, S. Score-Based Generative Modeling through Stochastic Differential Equations. NeurIPS 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aila, T. A Style-Based Generator Architecture for Generative Adversarial Networks. CVPR 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Belongie, S. Arbitrary style transfer in real-time with adaptive instance normalization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision; 2017; pp. 1501–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. MICCAI 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. NeurIPS 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Metz, L.; Chintala, S. Unsupervised Representation Learning with Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv preprint 2015, arXiv:1511.06434 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. ICLR 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki, K.; Michalski, M. ADA: Augmented Data Augmentation for GANs. ICLR 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gulrajani, I.; Ahmed, F.; Arjovsky, M.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A. Improved Training of Wasserstein GANs. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Miyato, T.; Kataoka, T.; Koyama, M.; Yoshida, Y. Spectral Normalization for Generative Adversarial Networks. ICLR 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Binkowski, M.; Lucic, M.; Seitzer, M.; Gelly, S.; Schultz, T.; Pietquin, O. Demystifying MMD GANs. ICLR 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Salimans, T.; Goodfellow, I.; Zaremba, W.; Chen, X.; He, X.; Zhu, Y. Improved Techniques for Training GANs. NeurIPS 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aila, T. Analyzing and Improving the Image Quality of StyleGAN. CVPR 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Aittala, M.; Laine, S.; Karras, E.H.A.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Alias-Free Generative Adversarial Networks. NeurIPS 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Keskar, N.S.; McCann, B.; Varshney, L.R.; Xiong, C.; Socher, R. CTRL: A conditional transformer language model for controllable generation. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1909.05858 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liang, X.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Xing, E.P. Toward controlled generation of text. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2017; pp. 1587–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhumoye, S.; Tsvetkov, Y.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Black, A.W. Exploring controllable text generation techniques. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2020; pp. 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, M.; Zhang, J. Variational discrete representation for controllable text generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Sheldon, D.; McCallum, A. DExperts: Decoding-time controlled text generation with experts and anti-experts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2021; pp. 3124–3136. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.; Hilton, J.; Niekum, S. Plug and play language models: A simple approach to controlled text generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, W.X.; Hu, W.; Li, J. Controllable text generation with disentangled latent variables. Neurocomputing 2022, 481, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Salimans, T. Classifier-Free Diffusion Guidance. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2207.12598 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional Generative Adversarial Nets. arXiv preprint 2014, arXiv:1411.1784 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miyato, T.; Koyama, M. cGANs with projection discriminator. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, R.; Alaluf, Y.; Atzmon, M.; Patashnik, O.; Bermano, A.H.; Chechik, G.; Cohen-Or, D. StyleGAN-NADA: CLIP-guided Domain Adaptation of Image Generators. In Proceedings of the ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG); 2022; Vol. 41, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, K.; Lee, H.; Yan, X. Learning Structured Output Representation using Deep Conditional Generative Models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2015, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.L.; Liang, P. Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); 2021; pp. 4582–4597. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, J.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, M.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. NeurIPS 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Houlsby, N.; Giurgiu, A.; Jastrzebski, S.; Morrone, B.; de Laroussilhe, Q.; Gesmundo, A.; Attariyan, M.; Gelly, S. Parameter-efficient transfer learning for NLP. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2019; pp. 2790–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, E.; Chang, K.W.; Natarajan, P.; Peng, N. The Woman Worked as a Babysitter: On Biases in Language Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2019; pp. 3407–3412. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, T.; Yatskar, M.; Ordonez, V.; Chang, K.W. Gender bias in coreference resolution: Evaluation and debiasing methods. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2018; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X. AdaGN: Adaptive group normalization for conditional image generation. IEEE TPAMI 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, E.; Strub, F.; de Vries, H.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A. FiLM: Visual reasoning with a general conditioning layer. In Proceedings of the AAAI; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.; Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.T.; Parekh, Z.L.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.V.; Sung, Y.; Li, Z.; Duerig, T. Scaling up Visual and Vision-Language Representation Learning With Noisy Text Supervision. ICML 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Moryossef, A.; Shuster, K.; Ju, D.; Weston, J. Filling the Gap: Learning Natural Language Image Search with Synthetic Datasets. In Proceedings of the EMNLP; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2203.02155 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Kadavath, S.; Kundu, S.; et al. Training a Helpful and Harmless Assistant with RLHF. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2204.05862 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; et al. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the ICLR; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Constant, N. The Power of Scale for Parameter-Efficient Prompt Tuning. In Proceedings of the EMNLP; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hessel, J.; Holtzman, A.; Forbes, M.; Choi, Y. CLIPScore: A Reference-Free Evaluation Metric for Image Captioning. In Proceedings of the EMNLP; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, R.; Kadian, A.; Gat, Y.; Chechik, G.; Bermano, A.H. Image Generation With Multimodal Priors. In Proceedings of the ICLR; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood, C.; Williams, C.K.I. A framework for the quantitative evaluation of disentangled representations. In Proceedings of the ICLR; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Roller, S.; Goyal, N.; Artetxe, M.; et al. OPT: Open Pre-trained Transformer Language Models. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2205.01068 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y.; Simard, P.; Frasconi, P. Learning long-term dependencies with gradient descent is difficult. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 1994, 5, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ICLR; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proceedings of NAACL 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. In Proceedings of the OpenAI Blog; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests; Vol. 45, 2001; pp. 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. Adaptive boosting algorithms for combining classifiers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ICML; 1999; pp. 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guyon, I.; Elisseeff, A. Introduction to Feature Selection; Vol. 3, 2003; pp. 1157–1182.

- Friedman, J. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine; Vol. 29, 2001; pp. 1189–1232. [CrossRef]

- Dong, E.; Wei, W.; Zhang, W.X. A new method for missing data imputation; Vol. 5, 2013; pp. 263–276.

- Little, R.J.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; Wiley, 2018.

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Vincent, P. Representation Learning: A Review and New Perspectives. IEEE TPAMI 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, I.; Matthey, L.; Pal, A.; Burgess, C.; Glorot, X.; Botvinick, M.; Mohamed, S.; Lerchner, A. β-VAE: Learning Basic Visual Concepts with a Constrained Variational Framework. ICLR 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, M.; Zhao, J.J.; LeCun, Y. Disentangling disentanglement in variational autoencoders. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Locatello, F.; Bauer, S.; Lucic, M.; Raetsch, G.; Gelly, S.; Schölkopf, B.; Bachem, O. Challenging common assumptions in the unsupervised learning of disentangled representations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR; 2019; pp. 4114–4124. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, C.P.; Higgins, I.; Pal, A.; Matthey, L.; Watters, N.; Desjardins, G.; Lerchner, A. Understanding disentangling in beta-VAE. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Workshop on Learning Disentangled Representations; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, J.; Tucker, G.; Grosse, R.B.; Norouzi, M. Don’t blame the ELBO! A linear VAE perspective on posterior collapse. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Mnih, A. Disentangling by factorising. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR; 2018; pp. 2649–2658. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.Q.; Li, X.; Grosse, R.B.; Duvenaud, D.K. Isolating sources of disentanglement in variational autoencoders. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2018; Vol. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Duan, Y.; Houthooft, R.; Schulman, J.; Sutskever, I.; Abbeel, P. InfoGAN: Interpretable representation learning by information maximizing generative adversarial nets. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2016; Vol. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; Xie, S.; Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE; 2020; pp. 9729–9738. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchacourt, D.; Tomioka, R.; Nowozin, S. Multi-level variational autoencoder: Learning disentangled representations from grouped observations. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pineau, J.; Vincent-Lamarre, P.; Sinha, K.; Lariviere, V.; Beygelzimer, A.; d’Alché Buc, F.; Fox, E.; Larochelle, H. Improving reproducibility in machine learning research (A report from the NeurIPS 2019 reproducibility program). Journal of Machine Learning Research 2021, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. Journal of Big Data 2019, 6, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, J.; Prakash, A.; Acuna, D.; Brophy, M.; Jampani, V.; Anil, C.; To, T.; Cameracci, E.; Boochoon, S.; Birchfield, S. Training deep networks with synthetic data: Bridging the reality gap by domain randomization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1082–10828. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.; Li, J.; Cai, Z.; Ma, W.; Yu, W. Image synthesis with semantic segmentation and instance segmentation for automated driving datasets. In Proceedings of the IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1141–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.B.; Andrychowicz, M.; Zaremba, W.; Abbeel, P. Sim-to-real transfer of robotic control with dynamics randomization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE; 2018; pp. 3803–3810. [Google Scholar]

- Cubuk, E.D.; Zoph, B.; Mane, D.; Vasudevan, V.; Le, Q.V. Autoaugment: Learning augmentation strategies from data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE; 2019; pp. 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, S.R.; Vineet, V.; Roth, S.; Koltun, V. Playing for data: Ground truth from computer games. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV). Springer; 2016; pp. 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Jia, Q.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tian, J. Data augmentation with learned transformations for one-shot medical image segmentation. Neurocomputing 2020, 388, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zou, K.; Yu, Z. EDA: Easy data augmentation techniques for boosting performance on text classification tasks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tamar, A.; Schwing, A.; Tenenbaum, J.; Zettlemoyer, L. Value iteration networks. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau, D. ALVINN: An autonomous land vehicle in a neural network. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 1989, 1, 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- Alshammari, R. A survey on natural language processing tasks and approaches in data augmentation. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2019, 31, 720–734. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Bag of Tricks for Image Classification with Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1904.06422 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, C.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Zhang, K.; Yu, Y. Learning data augmentation strategies for deep learning. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2007.03956 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H. Deep reinforcement learning for autonomous driving: A survey. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 20757–20772. [Google Scholar]

- Yosinski, J.; Clune, J.; Bengio, Y.; Lipson, H.; et al. Transferable visual models: A study on a large collection of class-labeled images from the web. Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2014, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Zoph, B.; Le, Q.V. Neural architecture search with reinforcement learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.01578 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Settles, B. Active learning. Synthesis Lectures on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning 2012, 6, 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; He, J. Edge computing for autonomous vehicles: A survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 213532–213547. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O.; Moritz, P.; Ibarz, J.; Abbeel, P. Trust region policy optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y. Learning Deep Architectures for AI. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning 2013, 2, 1–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamakarios, G.; Nalisnick, E.; Rezende, D.; Mohamed, S.; Lakshminarayanan, B. Normalizing Flows for Probabilistic Modeling and Inference. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2021, 22, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M.; Kucukelbir, A.; McAuliffe, J.D. Variational Inference: A Review for Statisticians. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2017, 112, 859–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Chopra, S.; Hadsell, R.; Ranzato, M.; Huang, F.J. A Tutorial on Energy-Based Learning. Predicting Structured Data 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; et al. On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2108.07258 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; et al. Chain of Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, I.G.; et al. Tree-of-Thought Deliberate Reasoning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.10601 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Schuurmans, D.; et al. Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2203.11171 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dettmers, T.; Pagnoni, A.; Holtzman, A.; et al. QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized LLMs. arXiv preprint 2023, arXiv:2305.14314 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ilharco, G.; Dodds, Z.; Wei, J.; et al. Editing Models with Task Arithmetic. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2212.04089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cao, N.; Aziz, W.; Titov, I. Inserting Knowledge into Pre-trained Models via Knowledge Fact Injection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, M.; Tan, L. Principles of Data Engineering; TechPress, 2018.

- Zikopoulos, P. Data Integration and Governance: Best Practices; IBM Press, 2017.

- Batini, C.; Cappiello, C.; Francalanci, C.; Maurino, A. Methodologies for data quality assessment and improvement. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 2009, 41, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J. Data Quality: The Accuracy Dimension. Morgan Kaufmann 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Chen, X. Data Quality Monitoring: A Comprehensive Survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2012, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchin, R. The Data Revolution; Sage, 2014.

- Vines, T.; Andrew, R. The Value and Impact of Data Curation. BioScience 2014, 64, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.; Pereira, J. Building Scalable Data Pipelines. Journal of Big Data 2016, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2103.00020 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Broder, A. On the Resemblance and Containment of Documents. In Proceedings of the Compression and Complexity of Sequences; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; et al. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rasam, S.; Narayanan, D.; Shoeybi, M.; et al. DeepSpeed: System Optimizations Enable Training Deep Learning Models with Over 100 Billion Parameters. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2007.03068 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Shoeybi, M.; Patwary, M.; et al. Efficient Large-Scale Language Model Training on GPU Clusters Using Megatron-LM. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2104.04473 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Griewank, A.; Walther, A. Algorithm 799: Revolve: An Implementation of Checkpointing for the Reverse or Adjoint Mode of Computational Differentiation. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software 2000, 26, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micikevicius, P.; Narang, S.; Alben, J.; et al. Mixed Precision Training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nangia, N.; Gupta, R.; He, W.; et al. Training Transformers with 8-bit Floating-Point. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2009.04013 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, T.; Fu, D.; Ermon, S.; Ré, C. FlashAttention: Fast and Memory-Efficient Exact Attention with IO-Awareness. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2205.14135 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Katharopoulos, A.; Vyas, A.; Patil, N.; Fleuret, F. Transformers are RNNs: Fast Autoregressive Transformers with Linear Attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W. Deep Compression: Compressing Deep Neural Networks With Pruning, Trained Quantization and Huffman Coding. arXiv preprint 2015, arXiv:1510.00149 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, B.; Kligys, S.; Chen, B.; et al. Quantization and Training of Neural Networks for Efficient Integer-Arithmetic-Only Inference. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; et al. Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2001.08361 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Biewald, L. Weights & Biases. Software 2020. https://wandb.ai.

- Abadi, M.; Chu, A.; Goodfellow, I.; et al. Deep Learning with Differential Privacy. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Helström, L.; Li, T.; Sorensen, A.; et al. HELM: A Holistic Evaluation of Language Models. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2210.15900 2022. [Google Scholar]

- EleutherAI. EleutherAI Language Model Evaluation Harness. https://github.com/EleutherAI/lm-evaluation-harness, 2021.

- Barocas, S.; Hardt, M.; Narayanan, A. Fairness and Machine Learning. Book manuscript 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Merity, S.; Xiong, C.; Bradbury, J.; Socher, R. Pointer Sentinel Mixture Models. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1611.01726 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Maimour, M.; Siahbani, M. Invisible Watermarking for Deepfake Detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.01746 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lake, B.; Ullman, T.; Tenenbaum, J.; Gershman, S. Building Machines That Learn and Think Like People. In Proceedings of the Behavioral and Brain Sciences; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, A.; Donahue, J.; Simonyan, K. Large Scale GAN Training for High Fidelity Natural Image Synthesis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Model Type | Objective Function | Sampling Efficiency | Latent Space | Notable Strengths | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GANs | Adversarial loss | Fast | Implicit | High-quality samples | Mode collapse, instability |

| VAEs | Variational lower bound (ELBO) | Fast | Structured, interpretable | Easy interpolation, latent utility | Blurry outputs due to inference |

| Normalizing Flows | Exact likelihood maximization | Moderate | Invertible, explicit | Precise likelihood, anomaly detection | High compute cost, Jacobian constraint |

| Diffusion Models | Denoising score matching | Slow | Implicit (LDM: explicit) | SOTA fidelity, stable training | Slow generation, compute-heavy |

| Criterion | Focus | Metrics / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Quality | Realism and coherence of generated data | FID, IS, human evaluation |

| Sample Diversity | Range of variation and mode coverage | Mode count, intra-class spread |

| Controllability | Accuracy and granularity of conditional outputs | Prompt fidelity, editability, zero-shot ability |

| Computational Budget | Efficiency in training/inference | FLOPs, GPU hours, latency |

| Likelihood Estimation | Ability to compute or estimate | Log-likelihood, bits/dim |

| Latent Space Utility | Smoothness and disentanglement of representations | Traversals, MIG, -VAE score |

| Training Dynamics | Stability, convergence, scalability | Loss curves, hyperparameter robustness |

| Aspect | Data Augmentation | Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Idea | Modify existing real data using transformations | Generate entirely synthetic data mimicking real-world scenarios |

| Use Case | When real data exists but needs variation | When real data is scarce, expensive, or risky to collect |

| Examples | Image flipping, rotation, scaling; text paraphrasing | Virtual environments for driving, healthcare, robotics |

| Efficiency | ✓ Computationally efficient | ✗ Computationally intensive |

| Control & Diversity | ✗ Limited to realistic transformations | ✓ High control, includes rare scenarios |

| Realism | ✓ Operates on real data | ✗ Depends on simulation fidelity |

| Scalability | ✓ Easily scalable with low cost | ✗ Requires high resources and effort |

| Generalization Risk | ✓ Low risk if transformations are valid | ✗ Risk if synthetic data is not representative |

| Training Domain | Image classification, NLP, speech recognition | Robotics, autonomous systems, healthcare, RL |

| Main Limitation | Limited by the variability of original data | May introduce unrealistic or biased data |

| Aspect | Description | Representative Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Data Synthesis | Generate data nearly indistinguishable from real samples. | GANs, Diffusion Models, VAEs |

| Controllable / Conditional Generation | Condition generation on labels, layouts, or prompts. | cGANs, Conditional VAEs, Guided Diffusion |

| Sequential & Structured Data Modeling | Model temporal or relational data like sequences and graphs. | RNNs, LSTMs, Transformers, GNNs, GATs |

| Representation Learning & Disentanglement | Learn interpretable, structured latent spaces. | VAEs, -VAEs, InfoGANs |

| Data Augmentation & Simulation | Expand dataset or simulate environments for training. | Transformations, Procedural Simulations |

| Probabilistic Density Estimation | Model true data distribution for generative tasks. | KDE, GMMs, VAEs, Flows, PixelCNN |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).