1. Introduction

Attributing cyberattacks to Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups remains a central challenge in national cyber defence and incident response [

1,

2]. Accurate attribution links observed indicators to adversary campaigns [

3], informs policy decisions while accounting for deception risks [

4], and enables proactive defence strategies grounded in tactic-level modelling [

2].

Traditional attribution approaches, largely based on heuristic rules, hand-crafted signatures, or expert-driven evaluations [

4,

5], struggle to generalise to evolving tactics or rare adversaries and remain vulnerable to false flag strategies. In response, recent advances in cyber threat intelligence (CTI) have introduced data-driven attribution, where contextualised relations among tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) provide semantically meaningful behavioural patterns [

3,

6].

However, many existing models remain incomplete. Sequence-based approaches such as DeepOP [

7] and DeepAPT [

8] capture temporal order but overlook lifecycle semantics, conflating actors that employ similar techniques at different operational stages. Others, such as CSKG4APT [

3], leverage multisource knowledge graphs but rely on static profile matching rather than adaptive relational learning.

To overcome these limitations, this work integrates the Cyber Kill Chain (CKC) [

9] directly into the attribution model, capturing both temporal progression and procedural function. A heterogeneous tripartite graph of APT groups, TTPs, and CKC stages is constructed, where TTPs are contextualised using Sentence-BERT (SBERT) semantic embeddings [

10]. This enables relational reasoning over behavioural similarity and lifecycle position, improving both the accuracy and interpretability of attribution, particularly for under-represented groups. As demonstrated in later sections, this design achieves state-of-the-art performance and produces insights suitable for practical deployment in Security Operations Centres (SOCs).

2. Related Work

APT attribution research spans feature-based, sequential, and graph-centric approaches, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses. Early efforts such as Irshad and Siddiqui [

1] demonstrated that blending technical and behavioural attributes can improve attribution, yet their reliance on static embeddings (e.g. Attck2Vec) restricts adaptability to evolving TTP vocabularies. Similarly, Hwang and Kim [

4] critically exposed the fragility of attribution artefacts under false flag conditions, but their Delphi-AHP method remains expert driven and offers little automation. These studies underscore the difficulty of scaling attribution when static features or human judgment dominate.

Graph-based models aim to overcome such limitations by capturing relationships across artefacts. CSKG4APT [

3] leverages multi-source knowledge graphs for large-scale campaign reasoning but reduces attribution to profile matching, limiting its ability to generalise beyond known actors. APT-MMF [

2] advances this by introducing a heterogeneous GNN with multimodal fusion and multi-level attention, yet procedural context such as attack-stage information is missing, meaning actors who employ similar techniques in different phases may remain indistinguishable. Sequence-driven methods, including DeepOP [

7] and DeepAPT [

8], learn temporal dependencies of ATT&CK TTPs, but neither explicitly models lifecycle semantics, leading to conflation between groups with overlapping technique sets.

Recent graph neural network approaches push further but still exhibit blind spots. GRAIN [

11] introduces APT–IoC–TTP graphs with attention mechanisms, successfully learning heterogeneous relations but lacking temporal or CKC integration. Deepro [

12] applies provenance-based GNN detection for campaigns, offering strong detection capabilities yet not fine-grained actor attribution. IPAttributor [

6], in contrast, clusters infrastructure artefacts with CTI enrichment, achieving strong results at the infra level but remaining disconnected from higher-level behavioural reasoning. At the strategic level, Goel and Nussbaum [

5] highlight attribution across cyberattack types, but their analysis is qualitative and policy-focused, offering little technical guidance for automation.

Taken together, these studies highlight three persistent gaps: (i) under utilisation of procedural context such as the Cyber Kill Chain, (ii) minimal integration of semantic embeddings with structured graph reasoning, and (iii) limited robustness against deceptive or low-frequency actors.

Table 1 summarises the critical distinctions and shows how our proposed model addresses these shortcomings.

3. Novelty and Contribution

The novelty of this work lies in its integration of semantic embeddings, procedural lifecycle modelling, and heterogeneous graph reasoning into a single attribution framework. Unlike prior approaches that either relied on static artefacts [

1], expert judgment [

4], or profile matching [

3], our design fuses semantic, temporal, and procedural signals to capture the operational flow of adversaries.

Key contributions include:

Tripartite Graph Design: Extends beyond APT-MMF [

2] and DeepOP [

7] by linking APTs, TTPs, and Cyber Kill Chain (CKC) stages in a unified graph. This prevents conflation of groups that share techniques but differ in lifecycle stage usage.

Contextual TTP Embeddings: Builds on semantic advances such as SBERT [

10] to encode technique descriptions into dense vectors, overcoming limitations of static embeddings (e.g., Attck2Vec). This enables generalisation across vocabulary variants and more nuanced behavioural similarity.

Lifecycle-aware Reasoning: Incorporates CKC semantics [

9] directly into feature vectors (Eq.

1), ensuring that identical techniques used in different stages are treated differently. This addresses a limitation noted in GRAIN [

11] and DeepAPT [

8], which omit procedural modelling.

Heterogeneous GNN Attribution: Uses relation-specific message passing across APT, TTP, and CKC nodes, enabling multi-hop reasoning. Unlike Deepro [

12] (focused on campaign detection) or IPAttributor [

6] (infrastructure clustering), our approach supports actor-level classification with both semantic and procedural depth.

Operational Readiness: Provides an automated graph pipeline that ingests unstructured reports, normalises them to ATT&CK/CKC, and delivers attribution in interpretable form. This reduces analyst workload and ensures applicability in real-world SOC environments.

Taken together, these contributions move beyond static, sequential, or profile-based attribution methods by unifying semantic, procedural, and structural intelligence. While prior research has often focused on either behavioural similarity or temporal patterns alone, our approach integrates both within a unified tripartite graph representation. This design provides not only higher attribution accuracy but also interpretable outputs that align with how analysts reason about APT campaigns in real-world SOC environments.

To further substantiate these contributions, the following section introduces the methodology used to operationalise this design, detailing how contextual embeddings, Cyber Kill Chain semantics, and graph-based learning are combined into a cohesive attribution framework.

4. Methodology

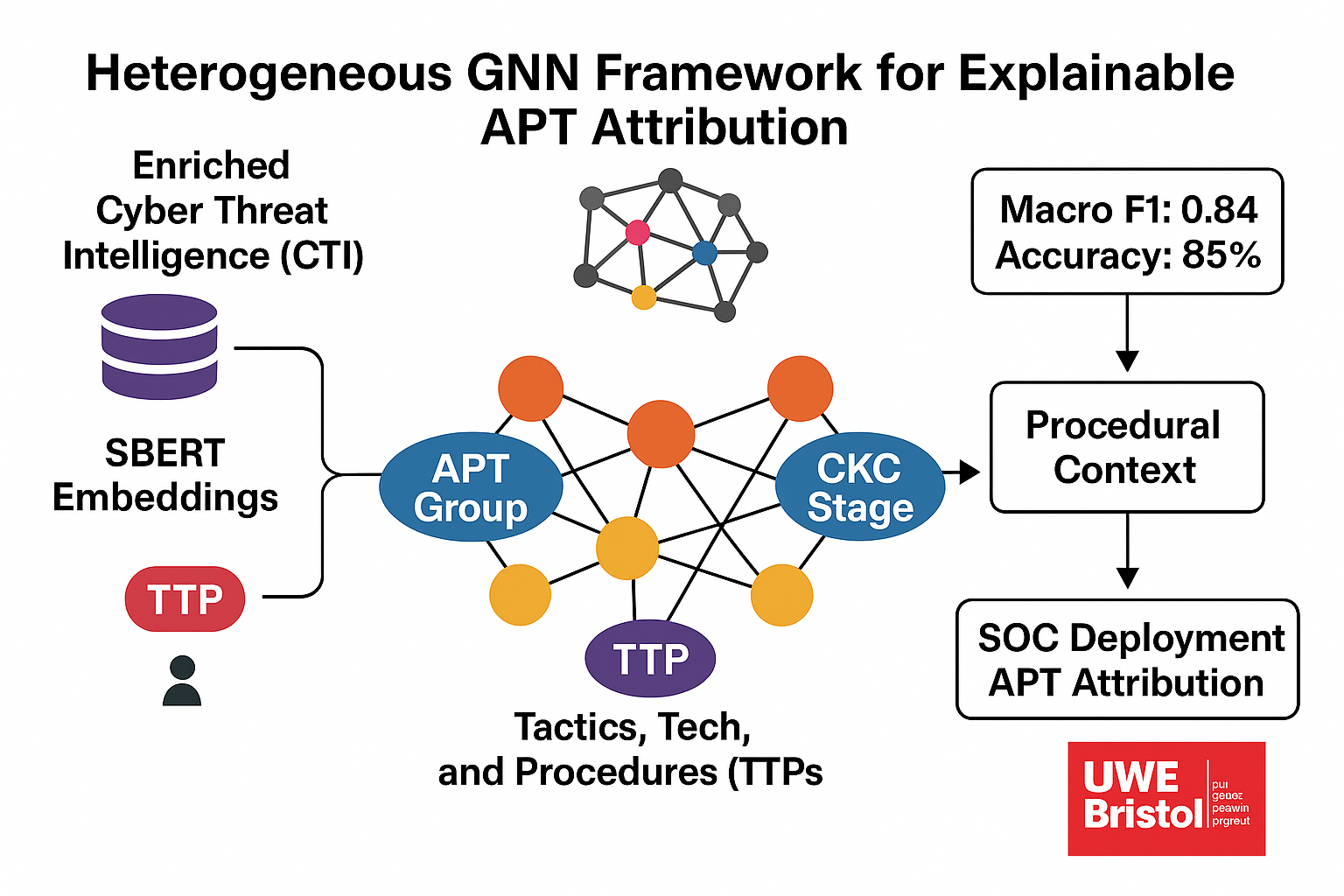

Building directly upon the conceptual advances discussed in

Section 3, this section formalises the proposed APT attribution framework into an implementable pipeline. The methodology is structured into three sequential stages that together realise the design principles of contextual reasoning, procedural grounding, and relational learning: (1) feature extraction of TTP semantics and lifecycle stages, (2) tripartite graph construction linking APTs, TTPs, and CKC nodes, and (3) heterogeneous GNN-based classification for actor-level attribution. Each stage is described in the following subsections.

Feature Extraction: contextualising TTPs with SBERT embeddings [

10] and Cyber Kill Chain semantics [

9] to capture both behavioural meaning and procedural role (

Section 4.1).

Graph Construction: assembling a tripartite heterogeneous graph of APTs, TTPs, and CKC stages, where relations encode observed usage, lifecycle mapping, and temporal sequence (

Section 4.2).

Classification: applying relation-aware message passing with GraphSAGE layers to learn actor-level embeddings and optimise attribution decisions (

Section 4.4).

This design ensures that semantic similarity, temporal ordering, and procedural role are jointly modelled, enabling robust and interpretable actor attribution that directly addresses the limitations of prior work.

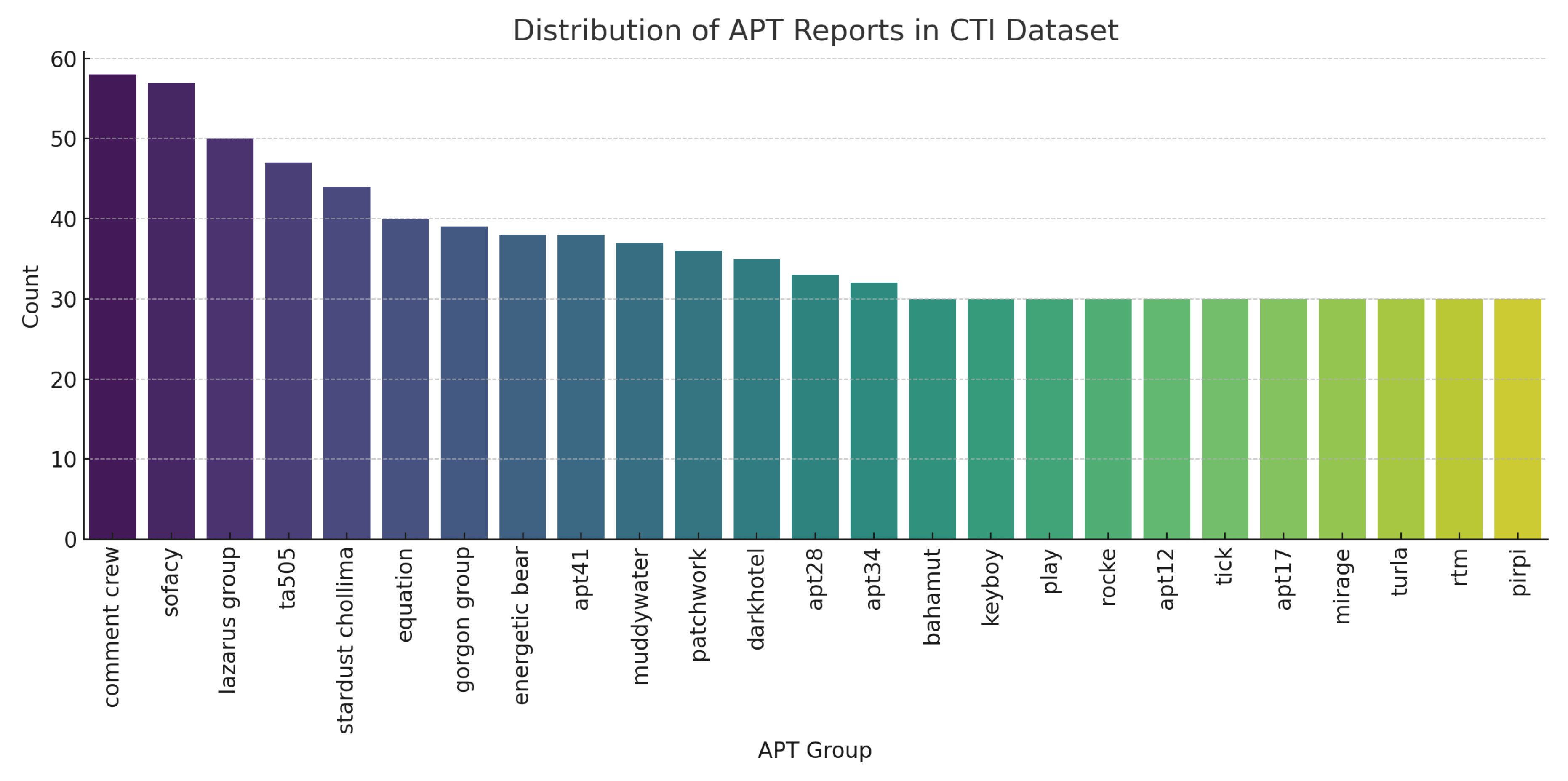

To motivate these design choices, we first examine the empirical distribution of APT classes and their frequency of report within the datasets.

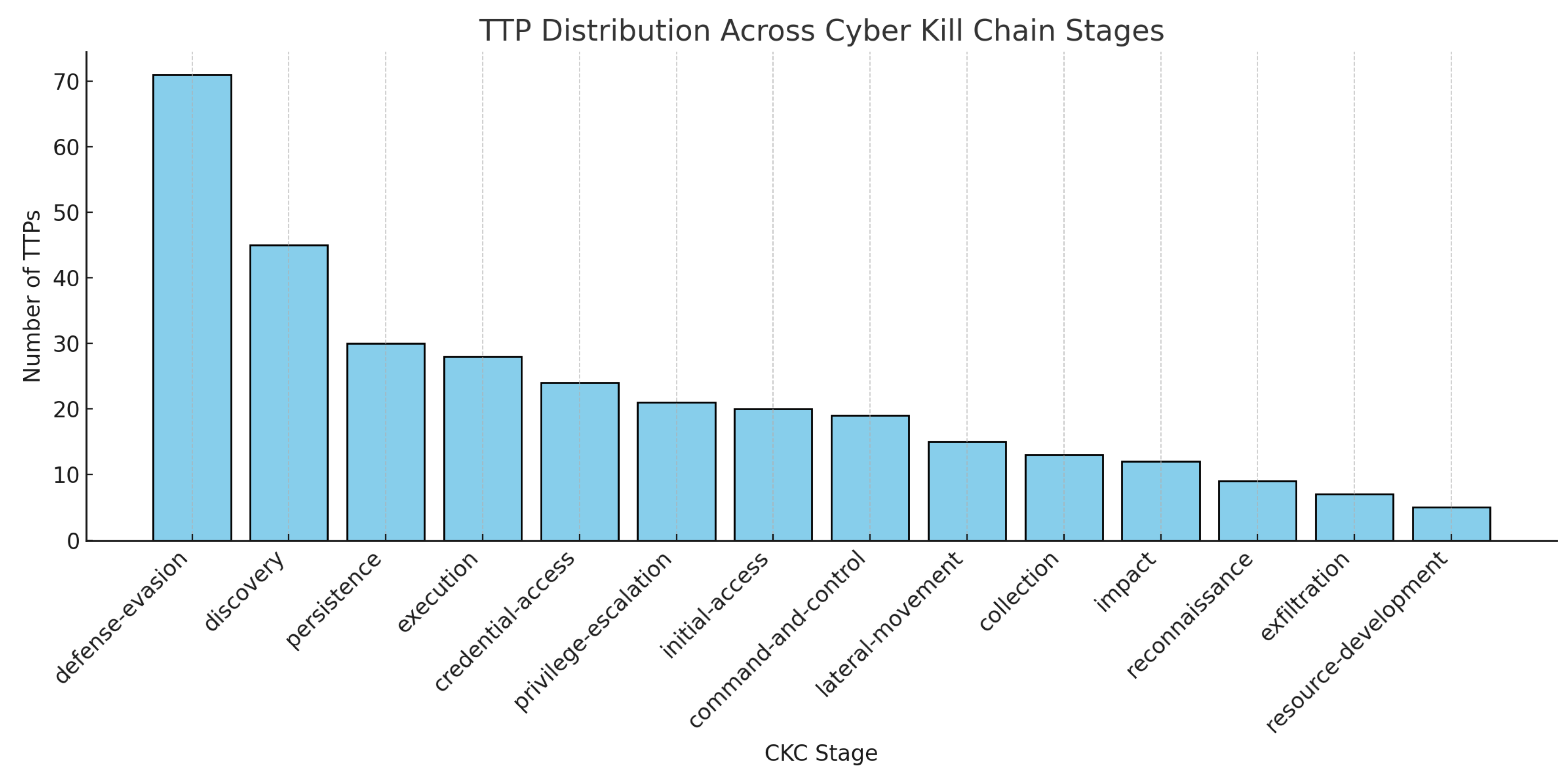

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 summarise the class and procedural distributions, which directly inform model design decisions.

The distributions in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 reveal two key characteristics of the dataset. First, the imbalance in APT report frequency highlights the dominance of certain well-documented actors such as Comment Crew and Sofacy, while many groups remain underrepresented. Second, the skew in TTP occurrences across Cyber Kill Chain (CKC) stages indicates that techniques linked to

defense evasion,

discovery, and

persistence dominate procedural space. These findings collectively motivate the use of class-weighted loss functions and CKC-aware embeddings in subsequent stages of model design, ensuring both balanced learning and lifecycle-sensitive attribution.

4.1. Feature Extraction

To represent each tactic, technique, or procedure (TTP), we combine two complementary sources of information:

Semantic meaning: Sentence-BERT (SBERT) embeddings are generated from the MITRE ATT&CK descriptions of TTPs, giving a 384-dimensional vector that captures semantic similarity between related behaviours (e.g., “credential dumping” and “password extraction”).

Procedural context: Each TTP is also mapped to its corresponding Cyber Kill Chain (CKC) stage (e.g., Initial Access, Execution, Lateral Movement). A one-hot vector encodes the stage, providing temporal and functional grounding.

The two components are concatenated to form the final TTP feature vector:

This design ensures that techniques which may be textually similar but occur in different phases of an attack are distinguished procedurally. Conversely, semantically related TTPs are drawn closer together in the embedding space, improving the model’s ability to generalise across reports.These contextualised embeddings form the foundation of the heterogeneous tripartite graph used for APT attribution.

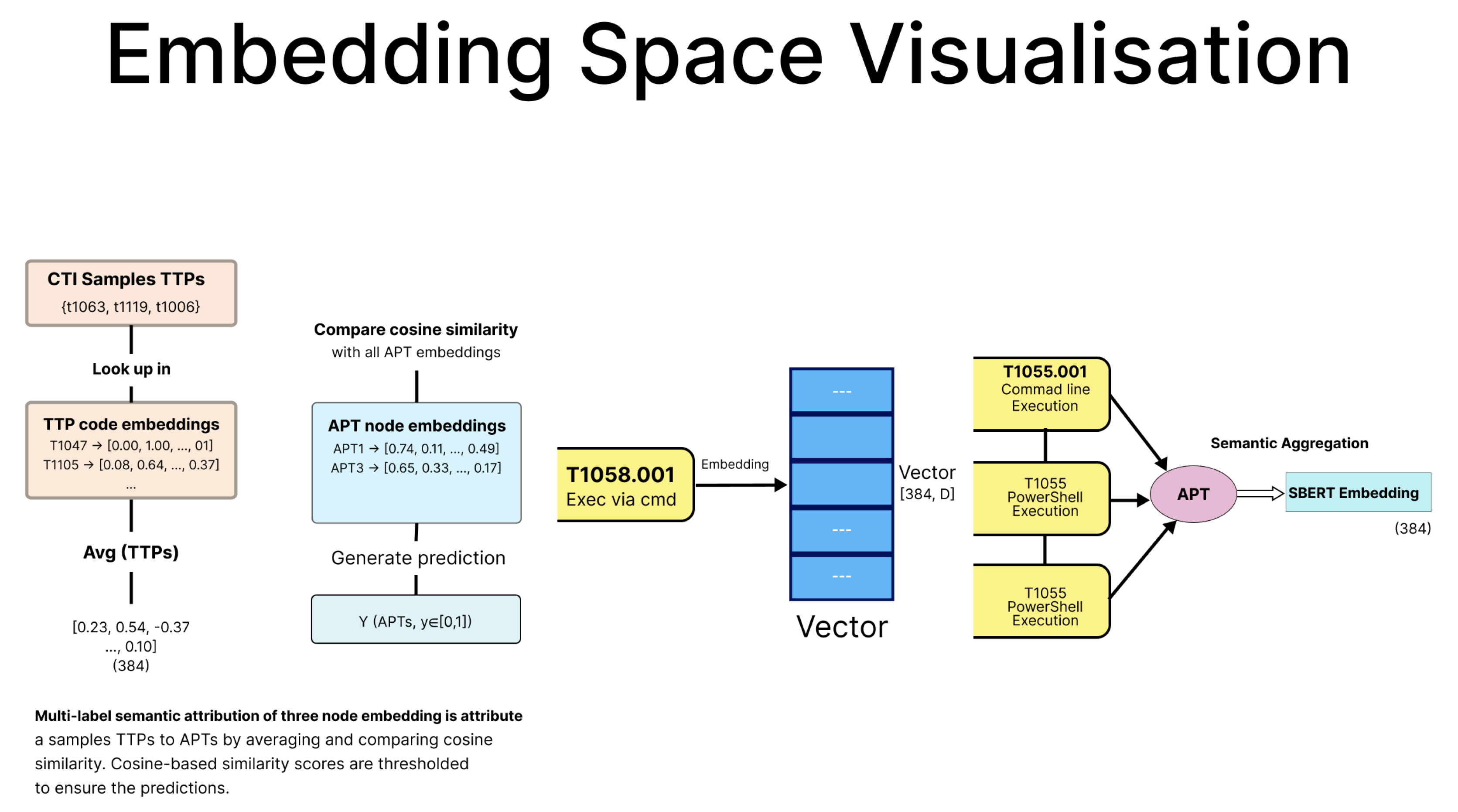

The embedding process and semantic comparison used for feature extraction are illustrated in

Figure 3. The diagram shows how TTPs are converted into 384-dimensional SBERT embeddings, averaged into feature vectors, and compared with APT embeddings using cosine similarity. This enables semantic multi-label attribution and supports generalisation across related techniques.

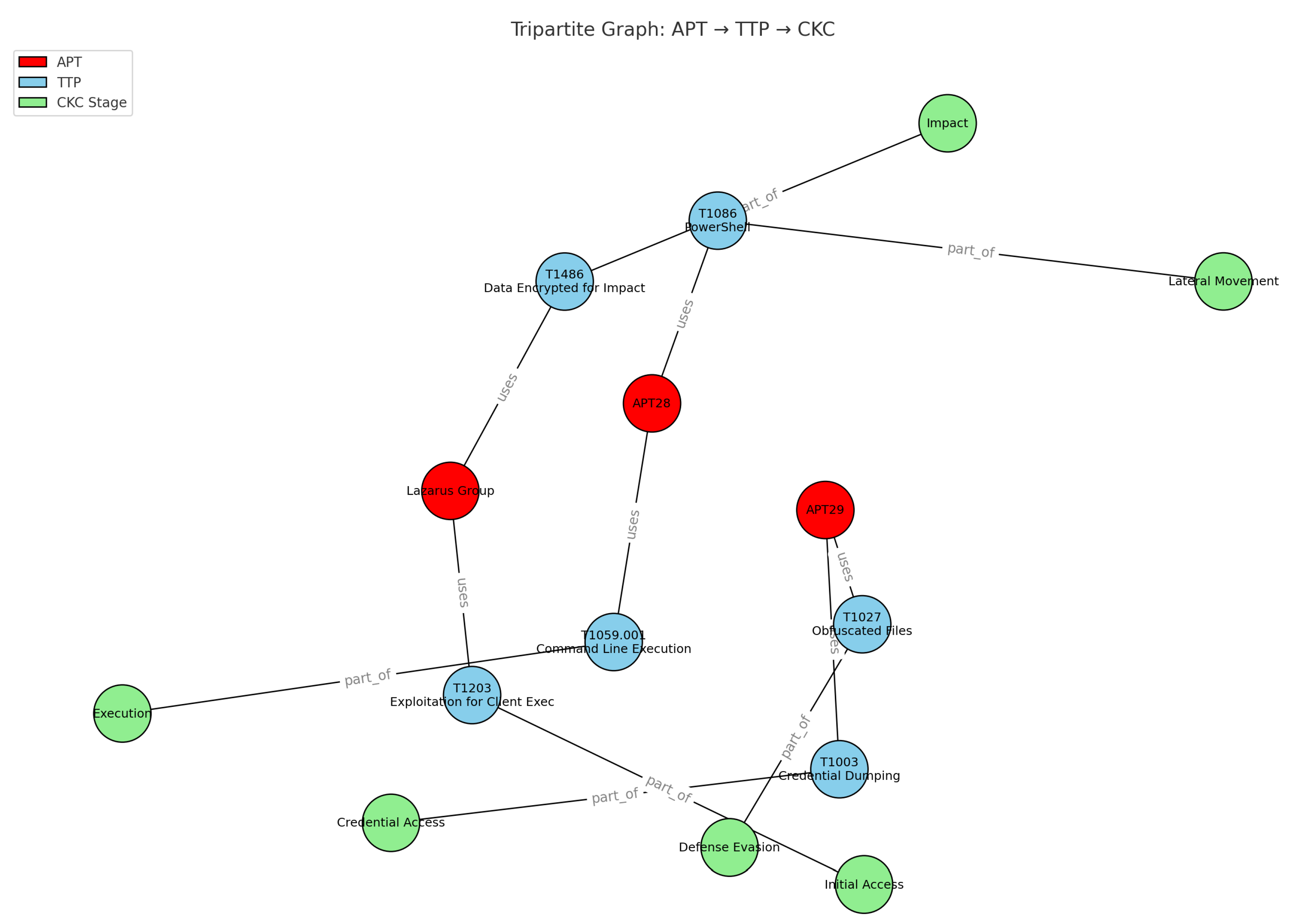

4.2. Graph Construction

Once contextualised TTP vectors are prepared, they are assembled into a heterogeneous tripartite graph linking APT groups, TTPs, and CKC stages. Each node type captures a distinct aspect of adversary behaviour: actor identity (APT nodes), behavioural technique (TTP nodes), and operational phase (CKC nodes). The edge set encodes three main types of relations:

APT–TTP edges: link actors to techniques they have employed in real campaigns, as reported in CTI sources such as ThreatFox, MISP, and OTX.

TTP–CKC edges: map each technique to its corresponding stage in the Cyber Kill Chain, providing procedural grounding and attack-context reasoning.

Temporal TTP–TTP edges: preserve the observed order of technique usage within campaigns, supporting temporal reasoning during model training.

Figure 4.

Tripartite heterogeneous graph linking APT groups (red), TTPs (blue), and CKC stages (green). Edges represent behavioural and procedural relationships: APT–TTP usage links, TTP–CKC mappings, and temporal TTP–TTP transitions. This structure enables relational learning across semantic, temporal, and lifecycle dimensions for improved APT attribution.

Figure 4.

Tripartite heterogeneous graph linking APT groups (red), TTPs (blue), and CKC stages (green). Edges represent behavioural and procedural relationships: APT–TTP usage links, TTP–CKC mappings, and temporal TTP–TTP transitions. This structure enables relational learning across semantic, temporal, and lifecycle dimensions for improved APT attribution.

Formally, the graph is defined as:

This tripartite construction is consistent with prior heterogeneous GNN-based attribution models such as APT-MMF [

2], but it extends them by explicitly encoding procedural (CKC) and temporal (TTP–TTP) relations. These relational structures enable the model to reason not only over which techniques are used, but also when and in what operational context.

4.3. Model Input

The heterogeneous graph constructed in

Section 4.2 is transformed into feature matrices and adjacency lists that can be consumed by the GNN. Each node type retains its own feature space: APT nodes are initialised with SBERT profile embeddings, TTP nodes use the 398-dimensional contextual vectors from Eq.

1, and CKC nodes are represented as one-hot vectors.

Message passing is then applied across node types. For a node of type

at layer

ℓ, its representation is updated by aggregating messages from neighbours:

where

denotes the aggregation function for relation

r (e.g., mean or SAGE-based aggregation [

13]), and

combines neighbour and self-representations with non-linearity and dropout. This update rule follows the message-passing paradigm introduced by Gilmer et al. [

14].

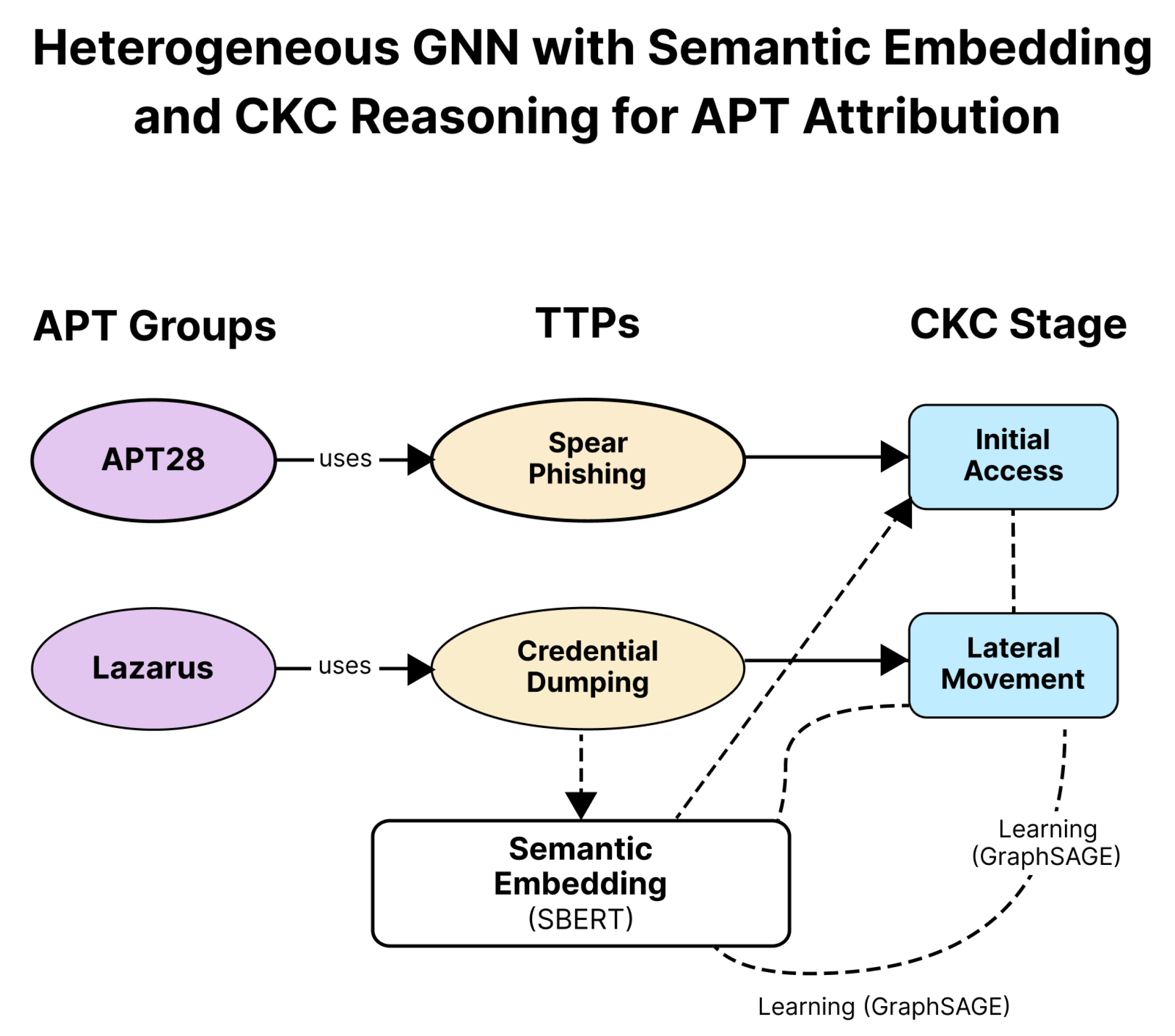

The heterogeneous input representation used by the GraphSAGE model is illustrated in

Figure 5. Each node type retains its own feature space: APT nodes are initialised with SBERT profile embeddings, TTP nodes with contextualised semantic embeddings, and CKC nodes with one-hot stage vectors. The model propagates information through these relationships using relation-aware message passing.

4.4. Classification

APT attribution is framed as a multi-class classification problem over APT nodes. Following Reimers and Gurevych [

10], we adopt the Sentence-BERT classification objective: given two embeddings

u and

v, we concatenate them with their element-wise difference

and apply a softmax classifier parameterised by

, where

n is the embedding dimension and

C the number of actor classes:

To mitigate class imbalance, we optimise a class-weighted cross-entropy loss [

15,

16]:

where

balances rare classes. During training, only labelled APT nodes contribute to the loss, while unlabelled nodes still propagate information through message passing. Regularisation includes dropout,

weight decay, and early stopping.

5. Training and Evaluation

The attribution task is trained and evaluated on the heterogeneous tripartite graph introduced in

Section 4.2. APT nodes are split into 80/20 train–validation partitions, ensuring class distribution is preserved. Optimisation uses Adam [

17] with learning rate

,

weight decay, batch size 32, and early stopping based on validation Macro-F1.

5.1. Evaluation Metrics

We report three widely adopted metrics for imbalanced classification settings [

2,

3,

7]:

where

C is the number of classes,

is the per-class F1 score,

is the support for class

c, and

N is the total number of samples. These measures balance raw accuracy with per-class robustness, capturing performance across frequent and rare actors.

5.2. Architectural Comparison

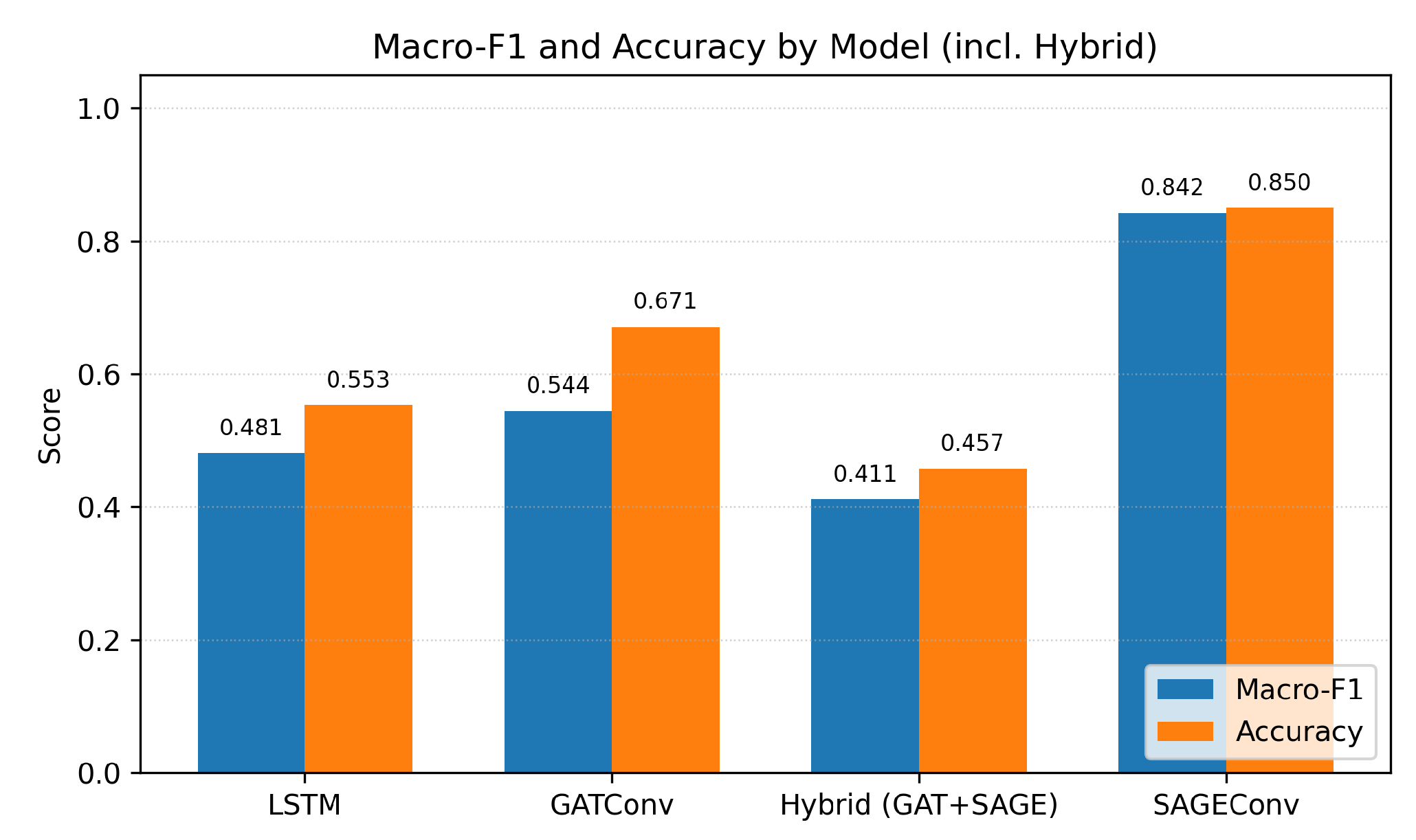

We benchmark four neural architectures: LSTM (sequence modelling), GATConv (attention-based GNN), Hybrid (GAT+SAGE), and the proposed GraphSAGE GNN. Results are summarised in

Table 2 and

Figure 6. The GraphSAGE architecture consistently outperforms others, achieving the best Macro-F1 and accuracy, confirming that semantic–procedural integration via heterogeneous graphs is superior to sequence-only or homogeneous alternatives.

6. Performance Analysis

6.1. Overall Performance

The HeteroGNN (GraphSAGE) model consistently outperforms all baselines across both Macro-F

and Accuracy. As presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 6, this model achieves the highest overall performance, demonstrating that combining semantic (SBERT) and procedural (CKC) information within the tripartite graph provides stronger representations of APT groups compared to sequence-only (LSTM) or attention-based (HeteroGNN with GATConv) approaches.

In contrast, the Hybrid HeteroGNN (GAT+SAGE) performs weakest, falling below both individual GNN variants. This indicates that simply combining multiple operators does not necessarily improve results and may introduce additional complexity without clear benefit.

Overall, the findings confirm that a heterogeneous GNN with GraphSAGE is the most effective approach for modelling APT attribution in this setting.

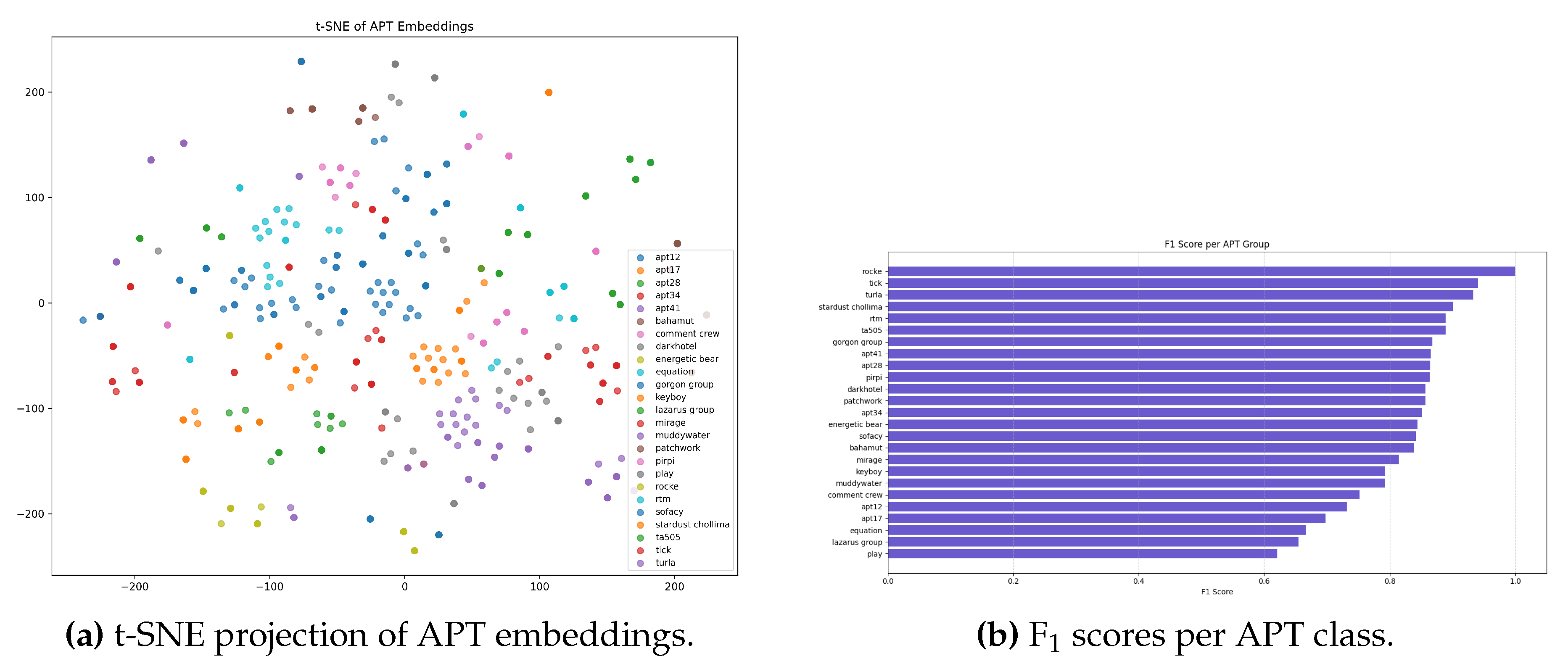

6.2. Representation Quality (t-SNE and Class-Wise )

To further analyse the quality of learned representations, we project the APT embeddings into two dimensions using t-SNE and evaluate per-class F scores to assess attribution stability across actors.

Figure 7.

Representation quality analysis for the HeteroGNN (GraphSAGE) model. (a) t-SNE visualisation showing well-separated APT clusters. (b) Class-wise distribution highlighting strong attribution for distinctive or well-supported actors.

Figure 7.

Representation quality analysis for the HeteroGNN (GraphSAGE) model. (a) t-SNE visualisation showing well-separated APT clusters. (b) Class-wise distribution highlighting strong attribution for distinctive or well-supported actors.

For each APT class

c, the F

score is defined as:

following the definition in prior benchmarking studies [

2,

7,

11]. Well-supported and distinctive actors (e.g., IDs 8, 14, 18, 21, 24) achieve near-perfect attribution, while underrepresented or behaviourally ambiguous groups (e.g., IDs 1, 12, 17) exhibit lower scores. Despite this, the distribution remains more balanced than in LSTM and APT-MMF baselines.

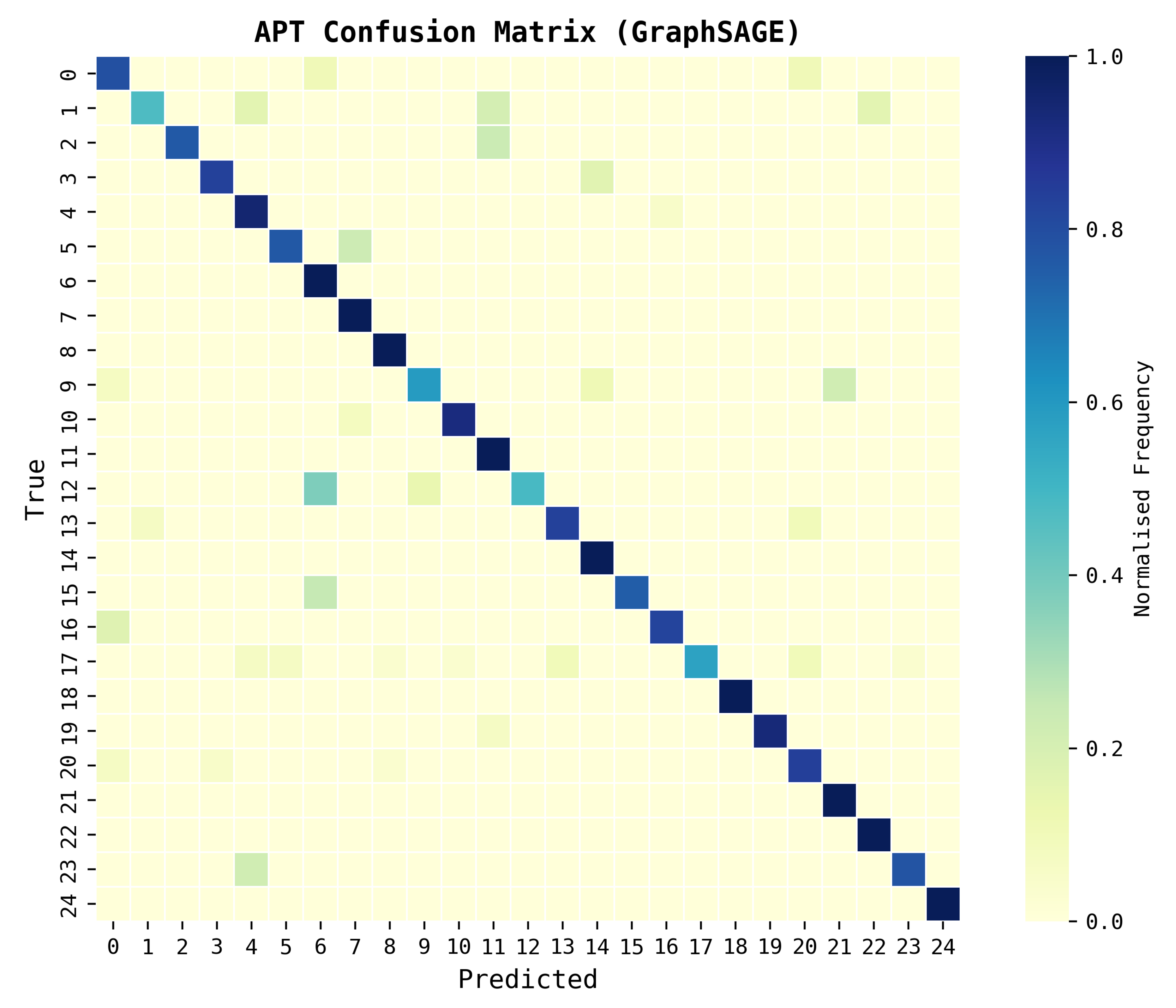

6.3. Confusion Matrix Analysis

To further examine prediction behaviour, we analysed the confusion matrix shown in

Figure 8. Diagonal dominance indicates strong overall attribution, while misclassifications mainly occur among behaviourally similar groups (e.g., APT12 vs. APT17). This highlights where the model confuses adversaries with overlapping TTP profiles, suggesting potential benefit from incorporating additional temporal or infrastructure-based features.

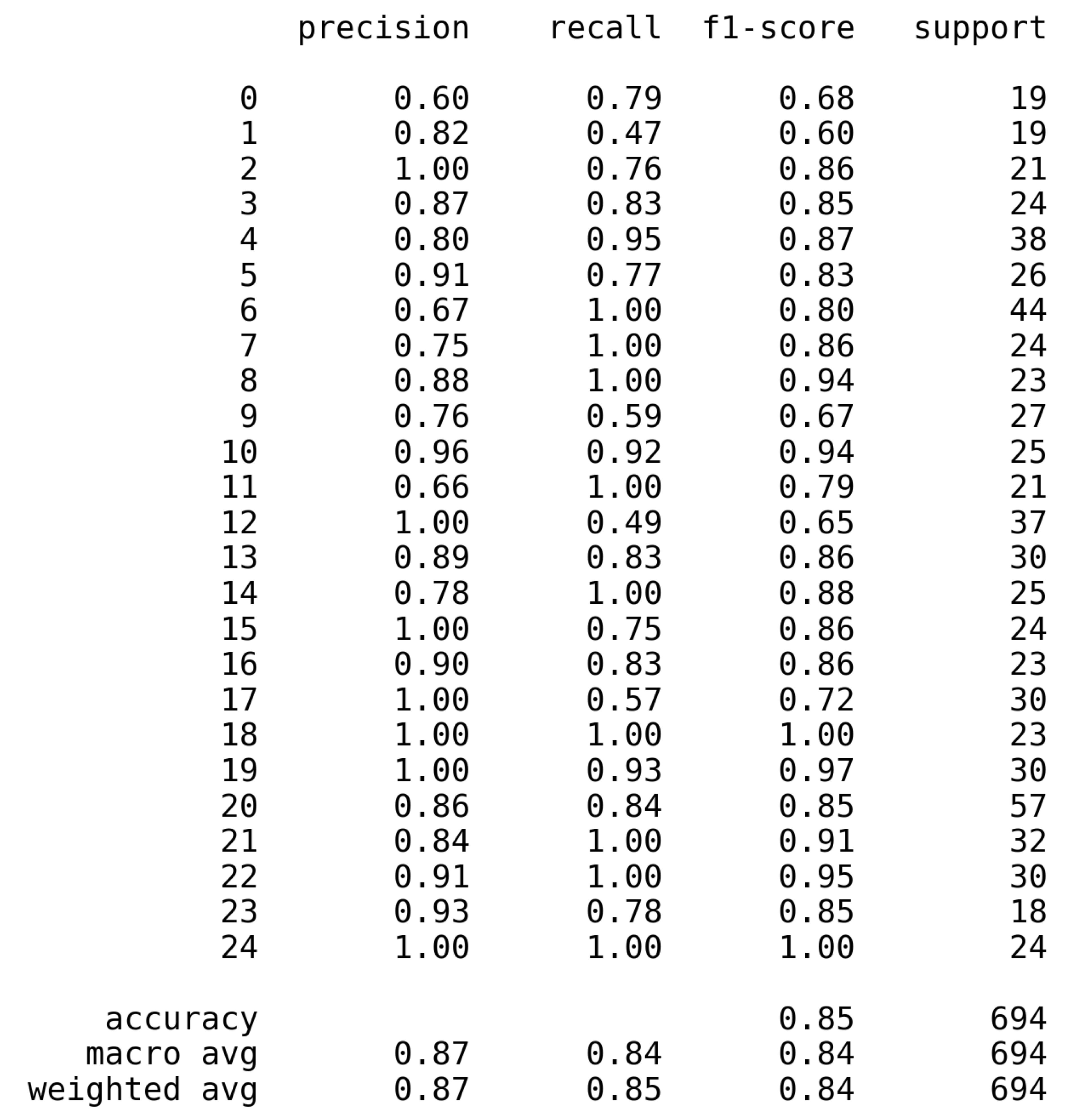

6.4. Classification Report

Beyond per-class F1, the full classification report in

Figure 9 provides a comprehensive view of precision, recall, and F1-score across all APT groups. The report shows that the model achieves balanced performance across most classes, with precision and recall values consistently above 0.80 for well-represented actors.

Low-resource classes (e.g., APT12, APT17) demonstrate lower recall, indicating that rare or behaviourally overlapping groups remain more difficult to detect. This mirrors challenges highlighted in prior work such as APT-MMF [

2], where imbalance heavily reduced Macro-F1. However, unlike APT-MMF, our model maintains stable precision even for minority classes, showing that SBERT embeddings combined with CKC structure help mitigate imbalance.

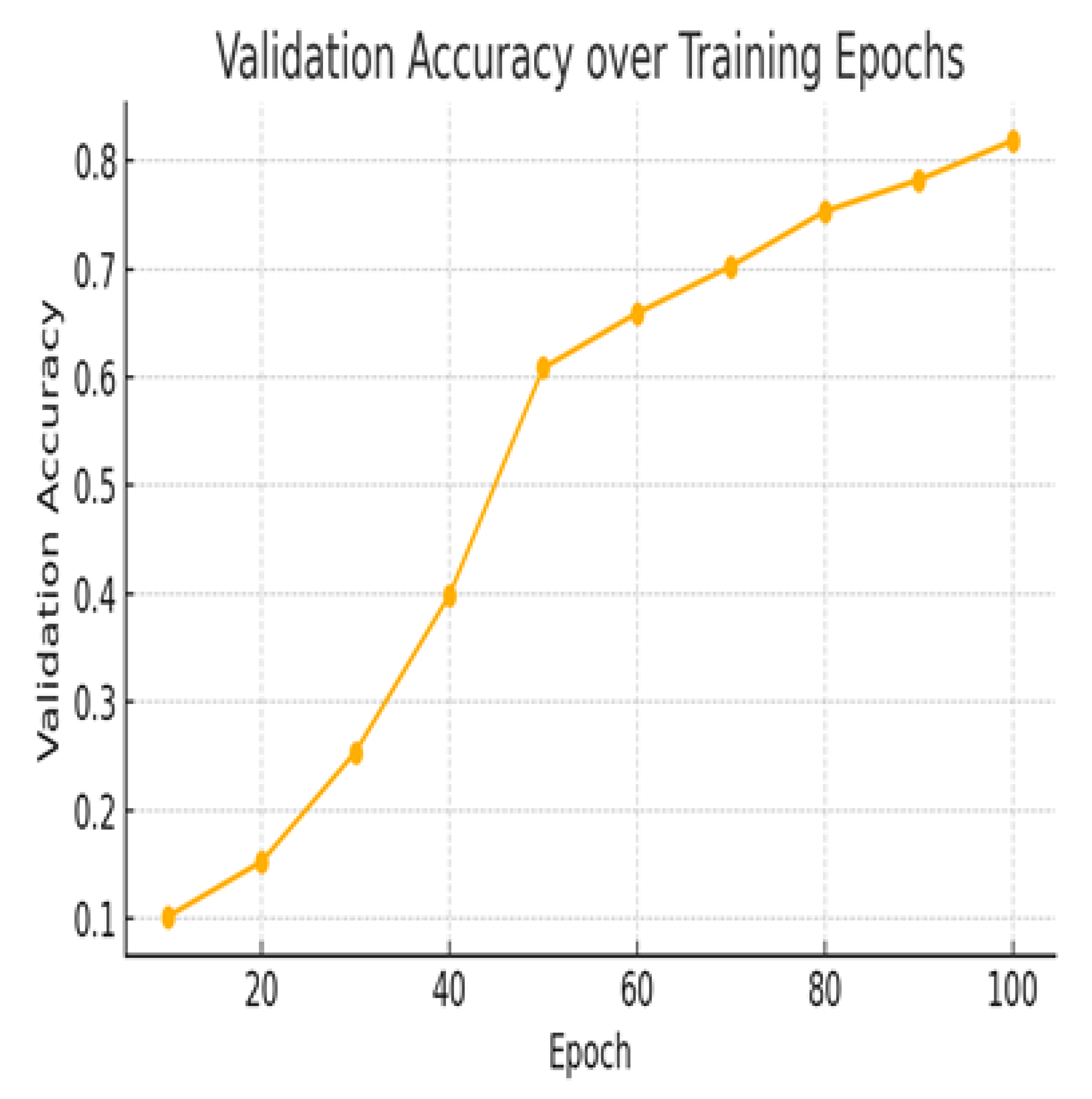

6.5. Learning Dynamics

Validation accuracy per epoch is computed as in Equation (

10), and the progression is visualised in

Figure 10.

Figure 10 shows that

steadily increases from approximately 10% at epoch 10 to above 80% by epoch 100. Steep gains between epochs 30–50 suggest rapid feature consolidation, after which convergence stabilises. The absence of strong oscillations indicates generalisation and no overfitting, aided by the heterogeneous tripartite structure and SBERT embeddings.

6.6. Summary Metrics

Table 3 reports the final summary metrics, confirming that the heterogeneous GNN balances underrepresented classes while retaining high accuracy. These results further validate the superiority of the GraphSAGE-based framework over prior APT attribution approaches such as APT-MMF [

2] and DeepOP [

7].

7. Benchmarking Against Prior Work

We benchmark our model against four representative approaches: APT-MMF, DeepOP, CSKG4APT, and GRAIN. These baselines capture different research directions. The results are summarised in

Table 4, with confusion matrix insights shown in

Figure 8.

APT-MMF. [

2] employs handcrafted metapaths and multilevel fusion, achieving

Macro-F = 0.687 on the full dataset. While effective, this approach overfits to frequent TTPs and struggles with long-tail classes. Our model explicitly incorporates CKC nodes and temporal edges, grounding attribution in lifecycle semantics. This design yields improved balance across rare classes and significantly higher performance (

Macro-F = 0.842), as reflected in both

Table 4 and the per-class distributions of

Figure 8.

DeepOP. [

7] demonstrates strong sequential path modelling, reporting

F = 0.894. However, DeepOP focuses exclusively on MITRE ATT&CK sequences and does not model actor-level grounding. As illustrated in

Figure 8, sequence-only methods conflate behaviourally similar actors (e.g., APT12 vs. APT17). Our model mitigates this by fusing semantic SBERT embeddings with CKC contextualisation, providing more discriminative actor representations (

Table 4).

CSKG4APT. [

3] leverages BERT-based models for CTI report analysis, with its best variant achieving

F, While effective for text-level relation extraction, this approach remains brittle to unseen or evolving behaviours and does not perform end-to-end actor attribution. Our model advances beyond sentence-level semantics by combining SBERT embeddings with lifecycle-aware graph reasoning, yielding higher attribution accuracy and generalisation (

Table 4).

GRAIN [

11] explores heterogeneous GNNs over IoCs with different semantic embeddings. Its strongest configuration (FastText) achieves

F = 0.815. However, GRAIN ignores CKC stage semantics and temporal progression, limiting interpretability and lifecycle grounding. By integrating contextual SBERT embeddings with explicit CKC nodes, our model outperforms GRAIN’s best configuration (

Macro-F = 0.842), while providing richer lifecycle-aware attribution, as seen in both

Table 4 and

Figure 8.

Synthesis. Taken together, these comparisons show that our model uniquely combines semantic, temporal, and lifecycle-aware features into a single end-to-end framework, outperforming multimodal, sequential, text-only, and heterogeneous baselines (see

Table 4 and

Figure 8).

8. Future Work and Recommendations

While the proposed framework achieves strong attribution performance, several directions remain open for exploration:

Few-shot and Meta-learning: Future work should explore meta-learning approaches that allow the model to rapidly adapt to new or underrepresented APT groups with very few examples. This is particularly important for emerging adversaries, where labelled CTI is scarce.

Adversarial Augmentation: Incorporating adversarial augmentation strategies can expose the model to perturbed or rephrased variants of TTPs during training. This would increase robustness against false-flag tactics and deceptive reporting, where actors deliberately alter their observable behaviour or language.

Synthetic CTI Generation: Generative methods (e.g., large language models or GANs) could be used to create synthetic but realistic CTI samples for rare APT classes. This would mitigate the long-tail imbalance problem, improving stability and accuracy across minority classes.

Multi-task Learning: Jointly predicting CKC stages and APT attribution may enable the model to capture richer temporal-procedural dynamics, further aligning with adversary lifecycle reasoning.

Hybrid Architectures: Combining GNNs with sequential models such as LSTMs or Transformers could enhance cross-report temporal reasoning and capture evolving campaign traces that unfold across multiple CTI sources.

Self-supervised Pretraining: Leveraging large unlabelled CTI corpora for contrastive or self-supervised training may improve embedding quality and resilience against sparse labelled datasets.

Explainability and SOC Integration: Embedding-level visualisations (e.g., UMAP/t-SNE projections) and confusion-matrix dashboards should be integrated into SOC workflows, helping analysts interpret adversary clustering and attribution confidence in real time.

These directions will advance the framework toward operational deployment in cyber defence centres, strengthening resilience against emerging adversaries and bridging automated AI models with analyst-driven decision-making.

9. Conclusions

This paper presented a heterogeneous GNN framework for APT attribution that integrates semantic embeddings, Cyber Kill Chain (CKC) procedural context, and multi-relational message passing. By constructing a tripartite graph of APTs, TTPs, and CKC stages, the framework jointly models behavioural semantics, temporal sequence, and procedural role. Architectural comparison

Empirical evaluation (

Section 5.2) demonstrated superior attribution performance with 85% accuracy and a Macro-F1 of 0.84, outperforming baselines such as APT-MMF and DeepOP. The confusion matrix and class-wise analysis confirmed robustness against long-tail imbalance, while benchmarking (

Section 7) highlighted competitive advantages over infrastructure- or rule-based attribution models. These findings validate the novelty claims made in

Section 3: that fusing semantic, procedural, and structural intelligence yields more accurate and interpretable attribution.

Critically, this work also exposes ongoing limitations. While the automated CTI→graph pipeline (

Section 4) supports reproducibility and near real-time workflows, challenges remain around rare-class generalisation, deception resistance, and SOC-level explainability. Addressing these issues requires integrating the future research directions discussed in

Section 8, especially few-shot learning, hybrid architectures, and interpretable dashboards.

In conclusion, this study not only advances state-of-the-art attribution accuracy but also lays the groundwork for operationally relevant, explainable, and scalable attribution systems. By bridging unstructured CTI with structured graph-based learning, it provides both technical innovation and a clear path toward deployment in real-world cyber defence environments.

References

- Irshad, E.; Siddiqui, A.B. Cyber threat attribution using unstructured reports in cyber threat intelligence. Egyptian Informatics Journal 2023, 24, 43–59. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Lang, B.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y. APT-MMF: An advanced persistent threat actor attribution method based on multimodal and multilevel feature fusion. Computers & Security 2024, 144, 103960. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Z. CSKG4APT: A cybersecurity knowledge graph for advanced persistent threat organization attribution. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2023, 35, 5695–5709. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, T.S. An exploratory study on artifacts for cyber attack attribution considering false flag: Using Delphi and AHP methods. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 74533–74544. [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Nussbaum, B. Attribution across cyber attack types: Network intrusions and information operations. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2021, 2, 942–953. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Liu, H.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, H.; Gu, Z. IPAttributor: Cyber attacker attribution with threat intelligence-enriched intrusion data. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1364. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xue, X.; Su, X. DeepOP: A hybrid framework for MITRE ATT&CK sequence prediction via deep learning and ontology. Electronics 2025, 14, 257. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, I.; Sicard, G.; David, E. DeepAPT: Nation-state APT attribution using end-to-end deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning – ICANN 2017, Cham, 2017; Vol. 10614, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 91–99. [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, E.M.; Cloppert, M.J.; Amin, R.M. Intelligence-Driven Computer Network Defense Informed by Analysis of Adversary Campaigns and Intrusion Kill Chains. Technical Report LM White Paper, Lockheed Martin, 2011.

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 3982–3992. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Chen, S.; Yang, J.; He, H.; Jiang, X.; Tan, X.; Jin, D. GRAIN: Graph neural network and reinforcement learning aided causality discovery for multi-step attack scenario reconstruction. Computers & Security 2025, 148, 104180. [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J.; Peng, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, T.; Lin, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, X. Deepro: Provenance-based APT campaigns detection via GNN. In Proceedings of the Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), 2022, pp. 747–758. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.L.; Ying, R.; Leskovec, J. Inductive Representation Learning on Large Graphs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). Curran Associates, Inc., 2017, pp. 1024–1034.

- Gilmer, J.; Schoenholz, S.S.; Riley, P.F.; Vinyals, O.; Dahl, G.E. Neural Message Passing for Quantum Chemistry. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR, 2017, Vol. 70, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 1263–1272.

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Jia, M.; Lin, T.Y.; Song, Y.; Belongie, S. Class-Balanced Loss Based on Effective Number of Samples. In Proceedings of the CVPR, 2019.

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. CoRR 2014, abs/1412.6980.

Figure 1.

Distribution of APT class labels across the dataset. Class imbalance motivates the use of weighted loss functions and Macro-F1 evaluation.

Figure 1.

Distribution of APT class labels across the dataset. Class imbalance motivates the use of weighted loss functions and Macro-F1 evaluation.

Figure 2.

TTP distribution across Cyber Kill Chain (CKC) stages. Counts per stage are skewed toward defense-evasion, discovery, and persistence, motivating lifecycle-aware feature modelling.

Figure 2.

TTP distribution across Cyber Kill Chain (CKC) stages. Counts per stage are skewed toward defense-evasion, discovery, and persistence, motivating lifecycle-aware feature modelling.

Figure 3.

Embedding space visualisation: TTPs are transformed into 384-dimensional SBERT embeddings and aggregated. Cosine similarity with APT embeddings enables semantic attribution and generalisation across related behaviours.

Figure 3.

Embedding space visualisation: TTPs are transformed into 384-dimensional SBERT embeddings and aggregated. Cosine similarity with APT embeddings enables semantic attribution and generalisation across related behaviours.

Figure 5.

Heterogeneous GNN framework: APT groups connected to TTPs and CKC stages, enriched with SBERT embeddings. GraphSAGE performs neighbourhood aggregation across the tripartite graph to produce APT attribution.

Figure 5.

Heterogeneous GNN framework: APT groups connected to TTPs and CKC stages, enriched with SBERT embeddings. GraphSAGE performs neighbourhood aggregation across the tripartite graph to produce APT attribution.

Figure 6.

Macro-F and accuracy across baseline and heterogeneous GNN variants. All GNN models are trained on the tripartite APT–TTP–CKC graph. Models compared: LSTM (temporal baseline), HeteroGNN (GATConv), HeteroGNN (GraphSAGE), and HeteroGNN (Hybrid: GAT+SAGE).

Figure 6.

Macro-F and accuracy across baseline and heterogeneous GNN variants. All GNN models are trained on the tripartite APT–TTP–CKC graph. Models compared: LSTM (temporal baseline), HeteroGNN (GATConv), HeteroGNN (GraphSAGE), and HeteroGNN (Hybrid: GAT+SAGE).

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix for the best-performing model, HeteroGNN (GraphSAGE), showing normalised classification outcomes across all 25 APT groups. Darker diagonal cells indicate correct attributions, while lighter off-diagonal values highlight confusions between behaviourally similar actors (e.g., APT12 and APT17).

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix for the best-performing model, HeteroGNN (GraphSAGE), showing normalised classification outcomes across all 25 APT groups. Darker diagonal cells indicate correct attributions, while lighter off-diagonal values highlight confusions between behaviourally similar actors (e.g., APT12 and APT17).

Figure 9.

Classification report for APT classes produced by the best model (HeteroGNN with GraphSAGE). Values show precision, recall, F1-score, and support for each class; overall accuracy and macro/weighted averages are reported at the bottom.

Figure 9.

Classification report for APT classes produced by the best model (HeteroGNN with GraphSAGE). Values show precision, recall, F1-score, and support for each class; overall accuracy and macro/weighted averages are reported at the bottom.

Figure 10.

Validation accuracy across training epochs for GraphSAGE. Rapid early gains followed by stable convergence indicate effective generalisation.

Figure 10.

Validation accuracy across training epochs for GraphSAGE. Rapid early gains followed by stable convergence indicate effective generalisation.

Table 1.

Comparison of existing work and this study.

Table 1.

Comparison of existing work and this study.

| Study |

Limitations |

How Our Work Responds |

| Irshad & Siddiqui [1] |

Relies on static embeddings (Attck2Vec) and handcrafted features; weak adaptability to evolving TTP vocabularies. |

Uses SBERT embeddings for contextual semantics, reducing vocabulary bias and capturing nuanced behavioural similarity. |

| Hwang & Kim [4] |

Identifies false-flag risks but remains expert-driven and unscalable. |

Moves beyond expert-driven analysis by leveraging SBERT embeddings and CKC-aware GNN reasoning, enabling scalable detection of false-flag operations and deceptive actor behaviours. |

| CSKG4APT [3] |

Profile matching over large graphs; brittle against unseen or evolving behaviours. |

Employs GNN reasoning with temporal and CKC semantics, generalising to novel actor strategies. |

| APT-MMF [2] |

Multimodal GNN with attention, but lacks lifecycle grounding; actors with similar TTP sets remain indistinguishable. |

Incorporates CKC-aware TTP embeddings to differentiate techniques by lifecycle stage. |

| DeepOP [7] and DeepAPT [8] |

Learn temporal order but omit procedural role; weak interpretability. |

Adds CKC stage semantics to temporal modelling for operational interpretability and improved attribution. |

| GRAIN [11] |

Models heterogeneous relations but ignores CKC and temporal progression. |

Adds CKC nodes and temporal TTP sequencing, resolving stage-order ambiguity. |

| Deepro [12] |

Strong for campaign detection but not fine-grained attribution; lacks procedural features. |

Extends GNN classification to actor-level with lifecycle-aware reasoning. |

| IPAttributor [6] |

Effective at infra-level clustering (IPs/domains), but blind to behavioural semantics. |

Operates at the operational layer (APT–TTP–CKC paths) for strategic attribution. |

| Goel & Nussbaum [5] |

Broad policy analysis; lacks temporal or technical modelling. |

Provides reproducible, data-driven attribution grounded in temporal and procedural CTI. |

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline and heterogeneous GNN variants for APT attribution. All GNN models operate on the tripartite APT–TTP–CKC graph; the only difference lies in the message-passing operator.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline and heterogeneous GNN variants for APT attribution. All GNN models operate on the tripartite APT–TTP–CKC graph; the only difference lies in the message-passing operator.

| Model |

Macro-F

|

Accuracy |

| LSTM (Temporal baseline) |

0.481 |

0.553 |

| HeteroGNN (GATConv) |

0.544 |

0.671 |

| HeteroGNN (GraphSAGE) |

0.842 |

0.850 |

| HeteroGNN (Hybrid: GAT+SAGE) |

0.596 |

0.611 |

Table 3.

Summary of final model performance.

Table 3.

Summary of final model performance.

| Metric |

Value |

| Accuracy |

85.0% |

| Macro-F

|

84.7% |

| Weighted-F

|

84.2% |

Table 4.

Comparison with related attribution models. Metrics are reproduced from prior work where available.

Table 4.

Comparison with related attribution models. Metrics are reproduced from prior work where available.

| Model |

Approach |

Features |

Graph Type |

Metric(s) |

Strengths |

| APT-MMF [2] |

Triple-attention heterogeneous GNN |

Text + Topology + Metapaths |

Heterogeneous |

Macro-

|

Multimodal fusion. |

| DeepOP [7] |

Transformer + causal modelling |

MITRE ATT&CK TTP sequences |

Sequential |

|

Strong path prediction. |

| CSKG4APT [3] |

BERT-based text modelling |

CTI report sentences |

– |

|

CTI text relation extraction. |

| GRAIN [11] |

Heterogeneous GNN + embeddings |

IoCs + semantic embeddings (FastText best) |

Heterogeneous |

|

Heterogeneous reasoning. |

| This paper |

SBERT GNN (GraphSAGE) |

TTP + CKC + edges |

Tripartite GNN |

Macro- |

High accuracy and lifecycle-aware attribution. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).