1. Introduction

As the world experiences increasing pressures related to food security, growing climate challenges, and continuing changes in global trade flows, the digital economy has become a central force of change and high quality development in the global agricultural system. In this context, China sees the digital economy as a key driver of agricultural and rural modernization and high quality agricultural development. The report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China explicitly called for accelerating the construction of a “Digital China”; deep integration of the digital economy and real economy; and empowerment of traditional industries through digitalization and intelligent transformation. The 2023 Overall Layout Plan for Building Digital China, elevated the construction of a “green and intelligent digital ecological civilization” goal to a national strategic priority. The report emphasized the deep integration of the digital economy and green economy, which provides policy direction and institutional support for leveraging digitization to drive the high-quality development of agriculture. In agriculture, the digital economy presents opportunities not only for the intelligent upgrading of production modes but also for systematic changes in resource allocation mechanisms, organizational, and ecological governance systems [1]. From a theoretical perspective, the substance of high quality agricultural development is to decouple economic growth from resource consumption and environmental degradation. Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity (AGTFP) is a methodology used to assess agricultural efficiency and sustainability by incorporating resource consumption and environmental pollution as undesirable outputs into traditional efficiency and productivity assessments [2]. Consequently, AGTFP is viewed as an important indicator of high-quality agricultural development, with improvements indicating enhanced production efficiency and coordinated improvements in resource conservation and environmental protection [3]. However, there exists an imbalance between the level of digital economy development and the progress of high-quality agricultural across regions in China, which constrains capacities for high quality agricultural progress in two ways. First, it poses a risk of further widening the regional “digital divide” - in turn undermining its overall effects of enabling digital empowerment for agricultural green transformation. Second, it inscribes indicative development trajectories that are not reliant on region-specific contexts [4,5]. Thus, it is crucial to articulate how the digital economy impacts AGTFP, in degrees of combinations and synergies of key factors, and including representative regional development trajectories to address gaps between implementation and national strategic objectives.

Scholarly research on the association between the digital economy and high-quality agricultural development has generated multi-dimensional, multi-level findings. At the macro level, research has concentrated on studying the overall impact of the digital economy on agricultural productivity and the transition to green agricultural production [1]. For example, Ma et al. (2025) [6] utilized provincial panel data to establish evidence for the claim that the digital economy has profound benefits for agricultural productivity because it enhances resource allocation efficiency and facilitates the dissemination of technological innovation. Cai and Wang (2025) [7] found that the digital economy can indirectly promote high-quality agricultural development through the mediating effect of green agriculture. Ma et al. (2024) [8] similarly demonstrated that the development of digital economy significantly suppresses agricultural carbon emission intensity - thereby demonstrating a beneficial role in supporting green transformation. At the meso level, research has examined the digitalisation of industrial chains and the impacts of industrial clustering [4,10]. Many scholars have explored how digital technologies are reshaping essential stages of agricultural production, distribution, and marketing. Xu et al. (2024) [11] showed that digital integration of agricultural value chains can effectively reduce transaction costs and improve coordination efficiency. Teng et al. (2024) [12] employed a simulation model to explore the process of digital transformation and found that different types of industrial clusters should adopt differentiated digital transformation paths to achieve optimal transformation performance.Similarly, Li et al. (2024) [13] have shown that digital industrial clusters have promoted structural upgrading of regional agricultural industries through knowledge spillovers and innovation network effects. At the micro level, research has considered the mechanisms of individual factors such as digital infrastructure, digital finance, and smallholder adoption of digital technologies [14-16]. Zhang et al. (2025) [17] provide broadband expansion helps smallholder farmers adopt new agricultural technologies and enhance productivity, while Gou et al. (2024) [14] showed that digital inclusive finance alleviates credit constraints and considerably improves green productivity of new agricultural entities. Overall, whilst there has been considerable progress, there are three limitations to the existing research. First, analytical perspectives remain fragmented; most scholarship has segregated individual factors from studying the interactions and synergies impacting technological, organizational, and environmental factors. Secondly, most of the existing analyses remain at a static level and fail to fully demonstrate how the digital economy continuously drives the dynamic process of agricultural transformation. Third, traditional econometric methods have limitations in their ability to examine complex type multi-factor interactions, and restrictions in examining how various regions may follow different pathways to achieve similar development outcomes.

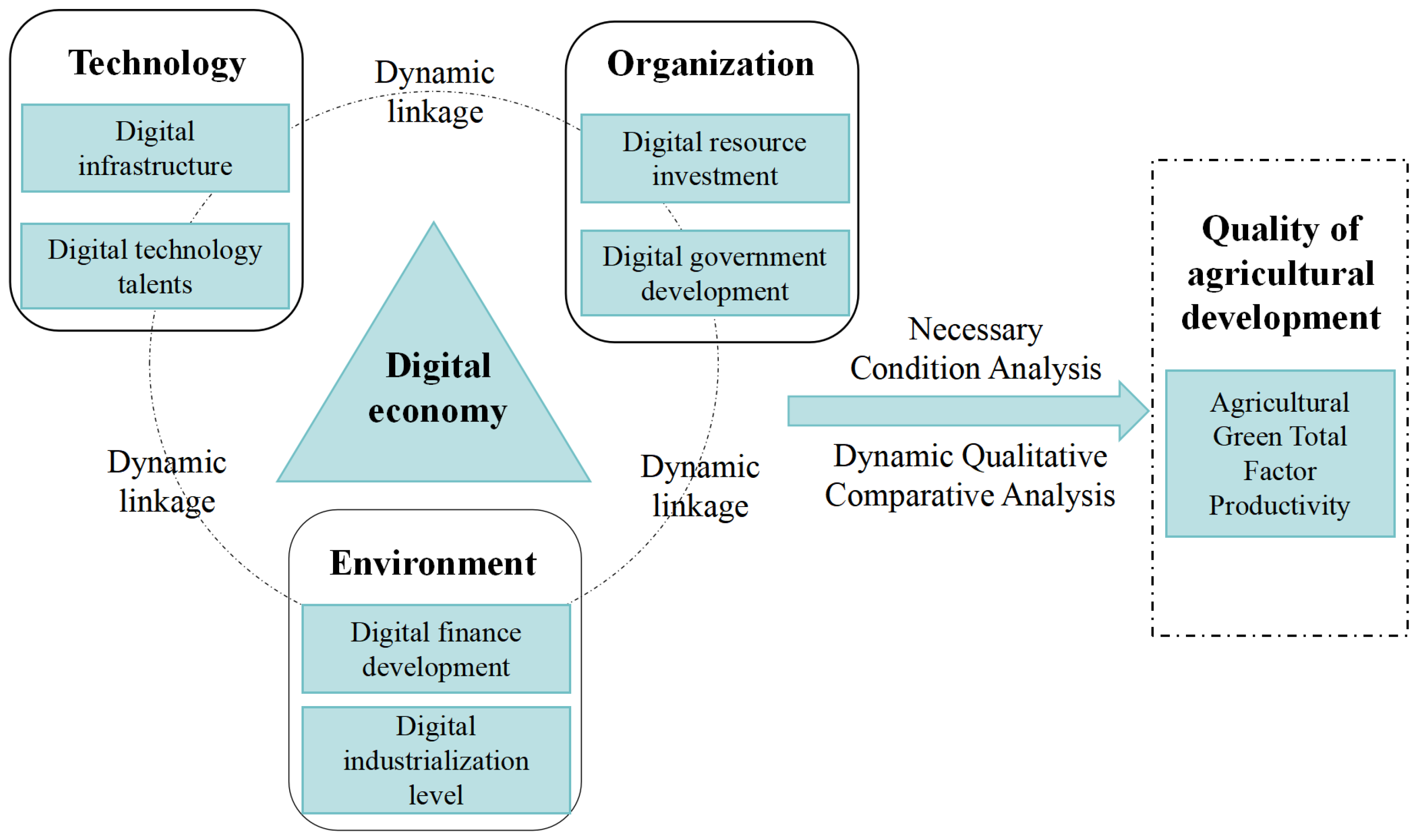

The marginal contributions of the contribution are three-fold. (1) Theoretical contribution: Supported by the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework, this research systematically integrates the technological, organizational, and environmental orientations to provide a holistic analytical perspective to understand the multiple and complex mechanisms of agricultural green development. (2) Methodological contribution: Combining necessary condition and dynamic analyses together discover the synergetic mechanisms and evolutionary trajectory of the influence of the digital economy on joint AGTFP. (3) Empirical contribution: Analysis hued in on several factor configurations that enhance AGTFP, or find the empirical evidence that high-quality agricultural development is achieved from various, context-based pathways.

2. Theoretical Model Construction

The TOE framework serves as a systematic theoretical lens to study the complex mechanisms in which the digital economy influences high-quality agricultural development. The framework was initially proposed by DePietro et al. (1990) [18] to study the adoption and implementation of technological innovations in organizations. The TOE framework posits that technology is only effective if it can be effectively adopted, used, and utilized, which relies on a joint consideration of the characteristics of the technology itself, organizational characteristics, and the technology’s context or environment. As research into the TOE framework and technology adoption evolved, Zhu et al. (2006) [19] extended the framework into the digital transformation space, demonstrating its theoretical value in understanding the complexity of technology adoption into organizations. In studies of the digitalization of agriculture, the practical application of the TOE framework has been amply demonstrated, integrating the full chain of influencing factors, from technological application micro-level context, organizational capability meso-level context, to the issue of policy environment at the macro-level context. Recent empirical studies contributed to enrich the application of the TOE framework. For example, Zhao et al. (2024) [20] demonstrated that the synergy of the three dimensions explained the outcome of digital economy better than solely relying on each dimension. Gao et al. (2023) [21] stated that there were significant resource allocation strategies across agricultural entities at different operational scale. Nagy et al. (2025) [22] pointed out that the TOE framework has a direct positive relationship with the performance of agricultural SMEs.These studies collectively validated the explanatory power of the TOE framework to understand the agricultural space, but also contributed to further our understanding of the digital economy ability to influence high-quality agricultural development, and offers a theoretical lens for this study.

A crucial aspect of the digital economy is the technological dimension. The technological dimension consists of two primary elements: digital infrastructure and digital technology talent, which together constitute the material and intellectual foundation of the digital economy. As outlined in the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Agricultural and Rural Informatization from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, a critical national project has been identified that involves building an integrated “sky-space-ground” agricultural observation network as part of its aim to promote the digital transformation of agricultural production. There is evidence that digital infrastructure enables the real-time monitoring of farm environments and threshold-specific data collection for farm management decisions, which can be the foundation for deploying green technologies such as water-saving irrigation [23]. In a related way, the key points for the digital rural development work in 2023 focus on the adoption of a “digital rural talent reform program” to address the need for human resources that are sufficiently skilled in agricultural production tasks in rural areas. Similarly, studies show that digital technology workers not only maintain and run smart agricultural equipment, but also help with data analytics and decision optimization, thereby improving the AGTFP [24].

The organizational dimension provides crucial resource support for the digital economy, and has two components which further exemplify the concept: digital resource investment and digital government construction. Regarding the investment in digital resources, continued investments in finance and equipment represents the material underpinning of high-quality development. The extent of investment directly associates with the extent of exploitation and adoption of technology [25]. Case studies show that for leading agricultural enterprises, organizational structure reorganization and management innovation are the keys to achieving digital transformation. These investments not only expand the application scope of intelligent devices, but also promote the systematic accumulation and intelligent analysis of agricultural data through the synergy of technology and organization. This process can optimize production decisions, reduce the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and ultimately enhance AGTFP [26]. In terms of digital government construction, the government plays a crucial role in creating an institutional environment conducive to the high-quality development of agriculture [27]. Specifically, digital government promotes the development of green agriculture through two major paths: First, construction of agricultural data and digital public service infrastructural sharing reduces the cost of information and transaction costs of agricultural producers [28]. Secondly, through the construction of digital regulatory, the government monitors for the environmental impacts of agricultural production through precise monitoring individuals, and executes institutional protection for green and sustainable practices [29].

The environmental dimension represents the external ecological basis of digital economy, which consists of two main elements: the promotion of digital finance and the development of the digital industry. For digital finance, digital inclusive finance mitigates the financing constraints faced by agricultural producers through big data–driven risk control and online credit services [14]. In particular, credit evaluation models that rely on digital technologies are more accurately able to assess agricultural operational risks, providing financing to sectors traditionally eschewed by financial institutions [30]. Digital finance also leads to green agricultural transformation by providing new insurance products and service models that provide risk coverage and financial security [31]. The development of the digital industry relates to the regional level of digital industrialization and directly affects the accessibility and multiplicity of technological resources for digital economy. Regions with highly developed digital industries can provide agricultural sectors with more advanced digital solutions and professional technical service teams. The spillover effects of technology do not end with access to hardware but also with the introduction of modern management concepts and innovative thinking [32]. Also, with the expansion of the digital industry has also led to the development of specialized digital service companies dedicated to serving agriculture. These companies provide customized high-quality development solutions for agriculture, significantly reducing the technological and financial risks associated with digital agricultural transformation, decreasing implementation costs while increasing technological transformation efficiency for agricultural producers [33].

Thus, this research provides a framework of analysis to explore how the digital economy generates high-quality agricultural development. This study adopts a TOE framework, guided by the following six antecedent conditions: Digital Infrastructure (DI), Digital Technology Talent (DTT), Digital Resource Investment (DRI), Digital Government Development (DGD), Digital Finance Development (DFD), and Digital Industry Development (DID), which corresponds to the technological, organizational, and environmental aspects to which they relate. The overall framework can be shown in

Figure 1.

2. Research Design

2.1. Research Method

2.1.1. NCA and Dynamic QCA Method

This paper employs an integrated model of Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) and Dynamic Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) as a systematic approach to understand the layered mechanisms underlying high-quality agricultural development. The QCA model, founded on set theory and Boolean algebra, is appropriate for analyzing complex, many-faceted, causally asymmetric, and equifinal relationships. It identifies the various configurations of antecedent conditions that lead to subsequent outcomes, which generate a relatively moderate-sized sample [34]. Since high-quality agricultural development is dynamic and cumulative by nature, conventional static QCA is unable to capture the evolution of the high-quality agricultural development processes. The dynamic QCA framework overcomes that shortcoming by revealing how causal configurations that lead to successful high-quality agricultural development evolve [35]. While QCA can be used to test for necessity of conditions, QCA’s requisite conditions are typically a more robust threshold. NCA entails a more precise measure of determining the degree of necessity of conditions and quantifying other important thresholds of conditions to determine whether the condition is necessary or not. Regardless, one can easily see the harmony of utilizing both NCA and dynamic QCA to capture various advantages: NCA is centered on articulating or identifying requisite conditions while dynamic QCA emphasizes sufficient configurations and how those sufficient configurations vary over time [36]. The explicit comparison of both methods enables a more thorough understanding of the multiple driving mechanisms behind high-quality agricultural development, through the dual lenses of necessity vs sufficiency and static vs dynamic analyses.

2.1.2. SBM-GML Model

In this research, we quantify AGTFP by taking into account both the Slack-Based Measure (SBM) of efficiency model and the Global Malmquist–Luenberger (GML) index. The SBM efficiency model addresses two important methodological issues. First, it accounts for the efficiency of production processes when undesirable outputs are present. Second, it also allows for the results to be comparable across time [37]. Assume there are

decision-making units (DMUs) in the sample. For each DMU, the input vector in period

is denoted as

, the desirable output as

, and the undesirable output as

. Based on undesirable outputs, the SBM efficiency model is specified as follows:

In this model, the variables

,

, and

indicate slack variables associated with inputs, desirable outputs, and undesirable outputs, respectively. The symbol

represents overall the efficiency score of the decision-making unit. A lower score indicates that the decision-making unit is closer to the production frontier, reflecting a higher level of green efficiency. On this basis, the Malmquist–Luenberger index is used to study the dynamic change in Green Total Factor Productivity. The Malmquist–Luenberger index is given as follows:

A value of the index indicates an improvement in green total factor productivity , whereas a value below 1 signifies a decline.

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Outcome Variable

This study uses agricultural development quality as the outcome variable, and AGTFP as the measurement indicator to operationalize this outcome variable, following the general approach set forth by Zhou et al. (2023) [38]. The AGTFP is computed based on the User-Oriented SBM-Global Malmquist (SBM–GML) model, which alleviates the measurement biases presented by other traditional radial models of productivity. This model incorporates undesired outputs into the efficiency evaluation system, ensuring both the accuracy of the results and achieving comparability across time dimensions [37]. Based on previous research and taking into account the availability of data and the characteristics of agricultural production, an input-output indicator system was constructed, which specifically includes the following input indicators: (1) number of agricultural laborers(10,000 persons), (2) total sown crop area (thousand hectares), (3) total agricultural machinery power (kW), (4) Fertilizer consumption (tons), (5) pesticide consumption (tons), (6) agricultural plastic film consumption (tons), and (7) effectively irrigated area (thousand hectares). These indicators comprehensively capture the major factors of agricultural production: labor, land, capital, and technology. Desirable output is defined as the gross value of agricultural output, while undesirable output is defined as total agricultural carbon emissions, which were calculated using the coefficient method. Thus, the input-output indicator framework is designed to capture the essential relationship between agricultural economic growth and its associated costs of output, resources and the environment.

2.2.2. Condition Variables

Using the TOE framework, this study creates a configurational analytical framework that embodies six element conditions. Theoretical analysis suggests that digital infrastructure, digital technology talent, digital resource input, digital government development, digital financial development, and digital industry development have complex interrelationships. The factors have direct paths toward AGTFP, and also act synergistically through three levels (technological empowerment, organizational support, and environmental facilitation). These paths could be constructed and unified to encourage sustainable agricultural development. In our study, the multidimensional coupling of factors serves as a systematic analytical approach to explore the pathways related to AGTFP. Among these various factors, we also quantify four composite variables representing (i) digital infrastructure, (ii) digital industry development, (iii) digital resource input, and (iv) digital government development, based on the entropy-weight method to create unified composite indices. The specific measurement indicators, data sources, and calculation methods can be found in

Table 1.

2.2.3. Data Calibration

To conduct a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis, the raw data must be transformed into fuzzy-set membership scores ranging from 0 to 1. This study applies the direct calibration method, setting calibration anchors based on both theoretical knowledge and the empirical distribution of the sample data. Following widely adopted academic practice, the upper quartile (75%), median (50%), and lower quartile (25%) of each variable are defined as the thresholds for full membership, crossover point, and full non-membership, respectively [44]. The specific calibration anchor values for each variable are presented in

Table 2 on the following page.

3. Data Analysis and Empirical Results

3.1. Necessary Condition Analysis

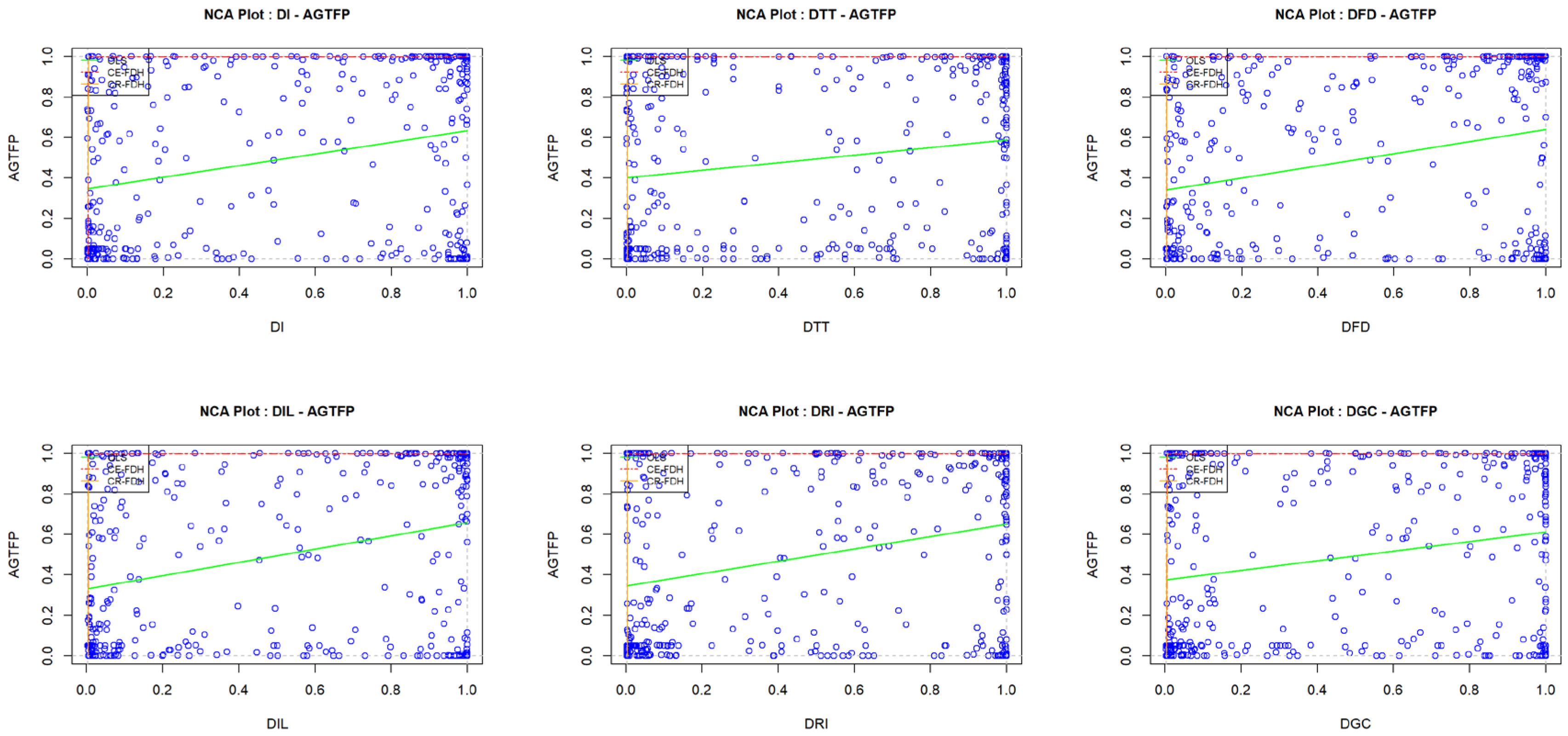

NCA aims to identify antecedent conditions that are essential for the occurrence of an outcome—that is, conditions that must be present whenever the outcome exists. To enhance the robustness of the findings, both NCA and QCA were employed in this study. First, using the NCA method, two estimation techniques—ceiling regression (CR) and ceiling envelopment (CE)—were applied to calculate the effect size (d) and significance level (p-value) of each condition. As indicated in

Table 3, all effect sizes are below the threshold of 0.1, suggesting that none of the variables were necessary for higher levels of AGTFP. These findings are additionally supported by the NCA scatterplot (

Figure 2), which shows significant dispersion below the ceiling line without an observable “corner-shaped” concentration or clear bounding constraint area. The scatterplot shows that no singular condition needs to be at a sufficient level in order to achieve high AGTFP. Second, the bottle neck levels presented in

Table 4 indicate that all conditions are non-necessary (NN) at lower levels of outcomes (e.g., Y ≤ 20). As levels of outcomes increase, conditions begin to exhibit bottleneck levels. For instance, when Y = 100, bottleneck levels for DI, DFD, DID, and DGD are 0.4, 0.2, 0.2, and 0.4 respectively and remain at 0 for DTT and DRI. These findings demonstrate that while some conditions are going to need to reach a moderate level in order to achieve high AGTFP, there are overall low threshold levels.

3.2. Analysis of Single-Condition Necessity

In addition, the study employs QCA to understand the need for each individual condition.

Table 5 suggests that the consistency levels of all of the individual conditional variables fall well below the threshold of 0.9 and, thus establishes that there is no single antecedent condition that is necessary for the outcome. This is consistent with the findings from the NCA. In general, both the quantitative NCA and qualitative QCA perspectives demonstrate predict that the antecedent conditions involve the outcome through combinatorial configurations and not through any isolated condition. This logic reinforces the aim of exploring multiple concurrent causal pathways with subsequent analyses. After performing an inter-temporal analysis for configurations with adjusted inter-group consistency distance > 0.2, the analysis tested whether any configuration combine of causal conditions might constitute a necessary condition. As shown in

Table 6, in most years, the inter-group consistency values for Cases 1–7 remain below the 0.9 threshold. Although in 2023, Cases 1–4 exhibited inter-group consistency above 0.9, their coverage values were all below 0.1. The extremely low coverage suggests that these causal relationships occur only sporadically in a few cases and thus lack generalizability. Taken together, the results indicate that none of the antecedent conditions in this study—whether associated with high or low AGTFP—can be regarded as a single necessary condition.

3.3. Analysis of Sufficiency for Condition Configurations

Building on the necessity analysis, this study employs R software to perform condition configuration analysis, aiming to uncover how multiple antecedent conditions interact to drive both high and low AGTFP. Given that this study is based on a medium-sized sample, a case frequency threshold of 1 is set, with an original consistency threshold of 0.8 and a PRI consistency threshold of 0.6 [45]. Following the analysis of the software output, we obtain results corresponding to complex, simplified, and intermediate solutions. Core and peripheral conditions are drawn from the prior established academic conventions: core conditions appear in both the simplified and intermediate solutions, indicating a strong causal relationship between core conditions and outcome, whereas peripheral conditions appear only in the intermediate solution, indicating a weaker causal relationship [46]. The intermediate solution served as a basis of analysis with the simplified solution identifying core conditions. This process allows for systematically identifying the multiple, concurrent causal pathways to outcome. The analysis is in

Table 7 and lists the configurations for high and low AGTFP. Utilizing the combination of condition variables, five configuration types are identified: the financial-government dual-driver, the infrastructure-government dual-driver, the financial-resource dual-driver, the industry-led driver, and the talent-island trap.

3.3.1. Summary of Results Analysis

(1) Configuration Analysis of High-Quality Agricultural Development

According to the analysis results in

Table 7, the consistency of the overall solution for high AGTFP reaches 0.843, exceeding the threshold of 0.75, indicating that the selected condition combination can fully explain the phenomenon of high AGTFP. The overall coverage rate of 0.424 and the PRI consistency of 0.645 both meet the standard requirements of the QCA method. Further examination of the inter-group and intra-group consistency adjustment distances of each pathway revealed that most values were within 0.3, indicating that different combinations of preconditions can effectively drive the formation of high AGTFP.

The Financial-Government dual-driver pathway is composed of two configurations, H1a and H1b. In configuration H1a, a high level of digital financial development, high level of digital government development, low level of digital infrastructure, and low level of digital technology talent are all selected as core conditions. The supporting condition used in this configuration is a high level of digital industry development . These conditions together create a high-enhancing effect on AGTFP. Jiangxi Province is a representative case of the pathway where the high-quality development of agriculture clearly expresses a government-driven process. The provincial government has legitimized the strategic priority of green ecology agriculture through top-level documents, such as the “No. 1 Document”, and established the direction to deploy financial resources to areas of green transformation. For instance, Yichun City incentivized low-carbon oil tea garden projects by promoting a full-chain mechanism that allocated 140 million RMB in loans. Additionally, Jizhou District financed the agricultural low-carbon transition of agricultural enterprises through the “Agricultural Low-Carbon Loan” program at 2.05% interest rate. This example demonstrates the successful coupling of policy-driven (government) direction and market-driven finance. The second configuration, H1b, shares the same core conditions as H1a, except in H1b high level of digital resource input is used as a supporting condition instead of digital industry development. The consistency of H1b is 0.895, and 0.287 coverage, both of which confirm the robustness and explanatory power of the Financial-Government dual-driver pathway.

The Infrastructure-Government dual-driver pathway indicates that the effective interaction of digital infrastructure and government governance can promote AGTFP even if support from digital finance is weak. This pathway is represented by a pair of highly similar configurations, H2a and H2b, each of which has high digital infrastructure, high governmental governance, and low digital financial development as core conditions. The differ in that H2a has low digital industry development as a supporting condition, while H2b has low digital resource input as a supporting condition. An exemplary illustration of the H2a pathway is Hebei Province. The Province has actively promoted the development of the national integrated computing power network with a hub node in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and the construction of the Zhangjiakou Data Center Cluster, to promote the synergistic development of data centers and renewable energy. On the policy side, the provincial government released the “Action Plan for Accelerating the Construction of Digital Hebei (2023–2027),” which identifies specific goals and tasks relative to the development of digital infrastructure. The plan seeks to promote the deep integration of digital technology with the real economy by implementing six special actions and 20 key projects.

Configuring H3 within the Financial-Resource dual-driver pathway reflects a scenario with intense capital development associated with digital finance and high relationship intensity with digital resource input. High intensity is also supported by high development within the digital industry pathway suggesting that there is solid infrastructure related to the digital industry, but digital infrastructure and digital government development were relatively weak. The logic for this type of configuration relates to financial capital identifying viable opportunities required for investment in agricultural green transformation, towards digitized solutions to improve resource allocation and efficiency in agricultural production. Guizhou Province is an illustrative example of how growth and intensity occurs in digital financial development as a first major driver. Within the province of Guizhou financial institutions have actively developed online methods to enhance financial product delivery, with the example of the “Qian Nong e-Loan” that utilizes big data risk control as mechanisms to enhance the accessibility of credit for farmers and agricultural enterprises. As a second driver, Guizhou Province has developed green financial products specific to green / organic industries such as tea and medicinal herbs. All of these products aim to ensure the efficacious allocation of certified funds for green and organic agricultural production.

The industry-led driver pathway, depicted by configuration H4, demonstrates an agricultural green transformation that relies on industrial upgrading as opposed to technology and capital-intensive high-quality development of agriculture pathways. This pathway is advanced by high levels of digital industry development and takes advantage of mechanisms such as large-scale production, specialization of business entities, and industry chain integration, to effectively offset disadvantages in digital technology development (including brand development, financial investment, infrastructure, and government governance). The Shaanxi Province “Luochuan Apple” has been established as a representative of this pathway. In terms of creating a highly organized industry model and unified green production standards, the industry has effectively promoted agricultural green development with improved efficiency through industrial upgrading.

(2) Configuration Analysis of Low-Quality Agricultural Development

The Talent Island Trap configuration (NH1) exemplifies a structural mismatch between the supply of digital technology talent and the supply of industrial development. The structure of this configuration consists of excess digital technology talent, with a deficit supporting industrial development infrastructure, investment resources, and compatible financing resources to adequately apply the skills of digital technology talent into an effective real driver of high-quality development of agriculture. The Xizang Autonomous Region can be regarded as a typical representative of this configuration. Although a large number of digital technology talents have been introduced through the aid Xizang policy, the relatively single agricultural industrial structure of the region, the limited application scenarios of digital technology and the insufficient investment in digital resources have led to the difficulty in effectively matching talents with industrial demands. This phenomenon of disconnection between talents and industries hinders digital technology talents from fully realizing their potential in enhancing AGTFP. Similarly, the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region also presents different manifestations of this problem. Although the region has a certain reserve of digital talents, due to environmental factors such as incomplete coverage of digital infrastructure and limited digital financial services, the application of digital technology in agricultural production still faces significant obstacles. Furthermore, the local digital industry development level is insufficient, and it is unable to provide the necessary technical support and service infrastructure for the high-quality development of agriculture of agriculture. This eventually led to digital technology talents falling into a predicament of “having talents but no platforms”. This phenomenon of talent silos highlights the limitations of simply introducing digital technology talents. To fully unleash the potential of such talents, it is necessary to simultaneously promote the construction of the industrial environment, improve digital infrastructure, strengthen financial service support, and build an ecosystem conducive to the effective application of digital technology talents.

3.3.2. Inter-group Consistency Analysis

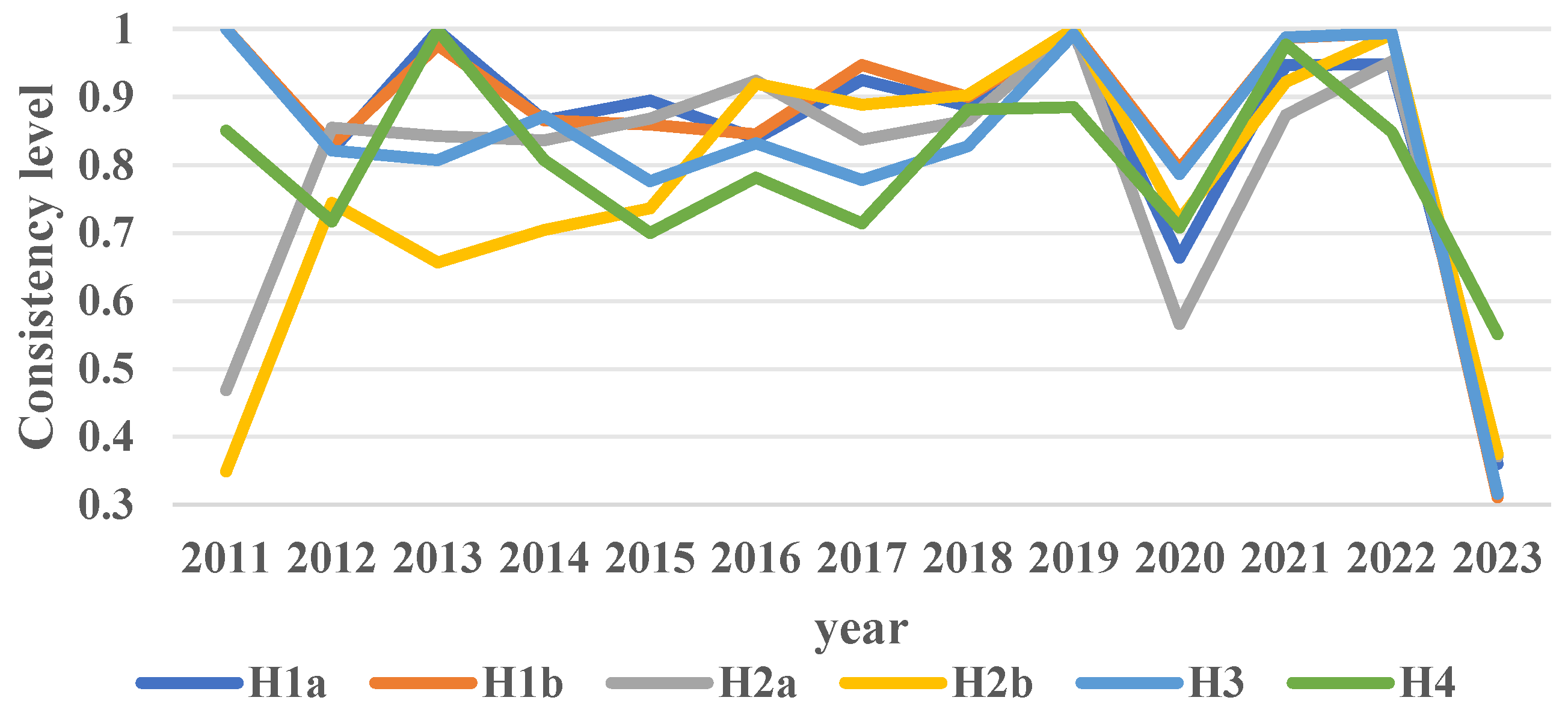

Inter-group consistency analysis is used to assess whether the prior configuration of the driving outcome systematically changes over time, thereby evaluating the temporal stability of the driving path. As shown in

Figure 3, driving pathways, remain fairly stable from 2011-2023, although slight changes are apparent. More specifically, digital finance (H1b, H3) configurations show higher temporal stability (consistently=0.85) as the result of market capital’s foundational role in agricultural green transformation persists (in most years). On the other hand, the digital infrastructure (H2b) pathway has experienced growth from low to high, suggesting that the interactive effects of digital infrastructure and government governance require a longer accumulation of resources to realize their potential. It is observe that all pathways experience a reduction in consistency in 2023, which may indicate a systematic change in the agricultural green development environment.

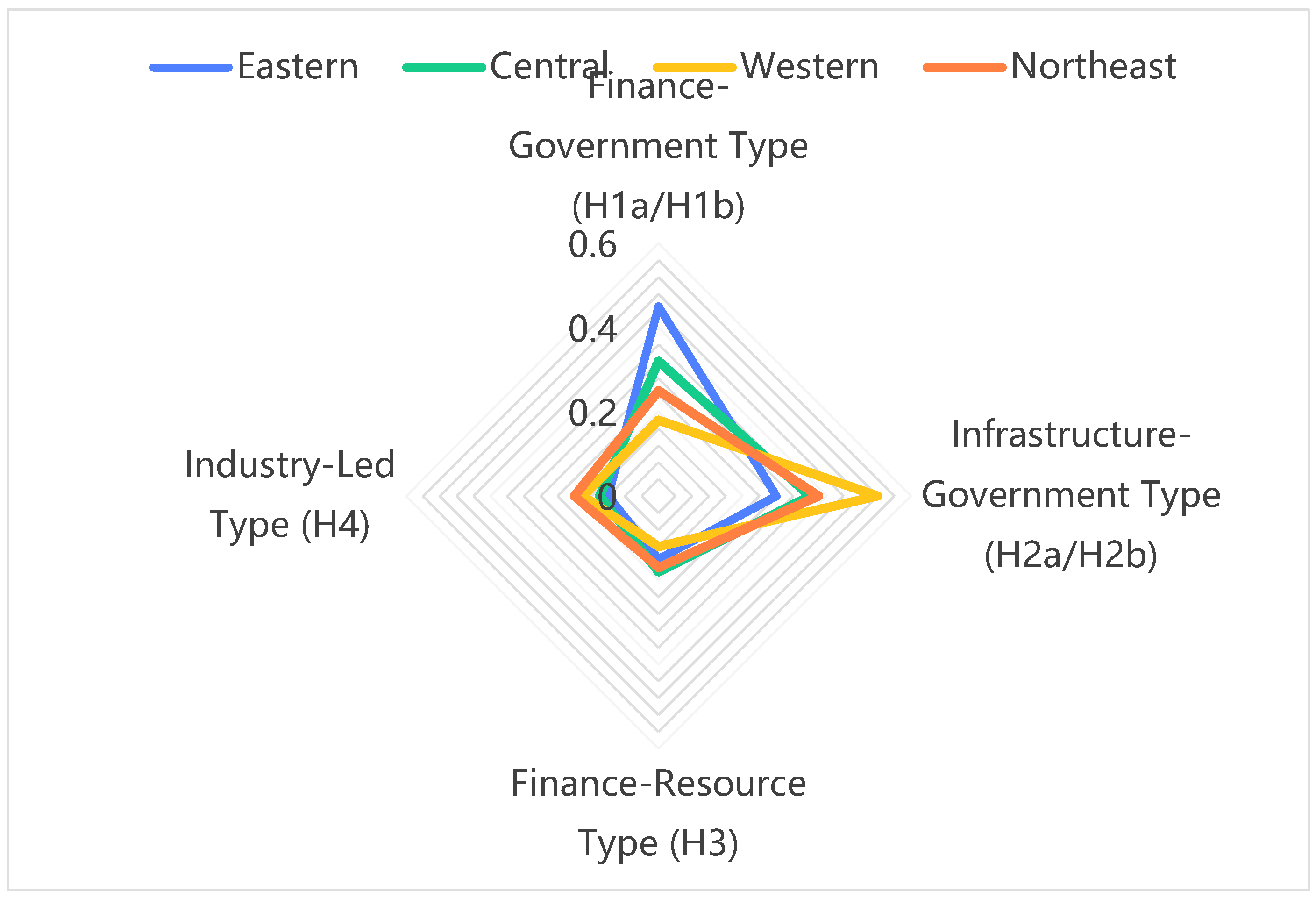

3.3.3. Regional Differences Analysis of High-Quality Agricultural Development Pathways

To better examine the spatial distribution patterns and regional applicability of driving pathways, this study builds layers on the configuration analysis by averaging the coverage of each driving pathway developed across four regions in China, which can be identified as the Eastern, Central, Western, and Northeastern areas of the country. The findings identified in

Figure 4 reveal substantial regional differences in the pathways concerning high-quality agricultural development. First, the Eastern region is a clear leader in the Financial-Government dual-driver pathway (coverage =0.45), highlighting the synergy advantages of its mature financial market and efficient government governance. Second, in the case of the Western region, the Infrastructure-Government dual-driver pathway is the predominant driver (coverage= 0.52), demonstrating the strong government-led push in developing the region’s digital infrastructure to catch up and improve. Both the Central and Northeastern regions have relatively high coverage in the Infrastructure-Government pathway. However, the unique performance of the northeastern region in the industry-led path (coverage=0.20) highlights the supporting role of its traditional industrial base in the high-quality development of agriculture. This spatial pattern indicates that the High-quality development of China’s agriculture shows obvious path dependence and regional adaptability. Therefore, policy design must fully take into account the comparative advantages and resource endowments of each region and implement differentiated and targeted promotion strategies.

3.4. Robustness Test

To test the reliability of the research conclusions, this study referred to the robustness test method proposed by Du et al. (2022) [47], raising the case frequency threshold from 1 to 2 and increasing the PRI consistency threshold from 0.60 to 0.65. After re-conducting the configuration analysis, two robust configurations S1 and S2 were obtained, as shown in

Table 8. Their core condition structures are highly consistent with the original high AGTFP configuration: S1 corresponds to the Financial-Resource dual-driver, and S2 corresponds to the Infrastructure-Government dual-driver driven type. The two configurations still maintained a high consistency under the adjusted parameters, with an overall consistency of 0.871 and an overall coverage of 0.36. This indicates that the original configuration structure still has explanatory power under different threshold Settings, and the research results have good robustness.

4. Discussion and Implications

4.1. Research Conclusions

This study focuses on the core issue of digital economy-driven agricultural high-quality development and systematically reveals the multiple pathways and dynamic mechanisms for enhancing AGTFP under the collaborative interaction of technological, organizational, and environmental factors. Based on panel data from 31 Chinese provinces from 2011 to 2023 and incorporating dynamic QCA and NCA methods, the study finds that no single necessary condition can independently lead to high AGTFP. Instead, multiple equivalent configurations exist, including financial-government dual-drive, infrastructure-government dual-drive, financial-resource dual-drive, and industry-led drive, as well as the talent island trap leading to low-quality development.

In the necessity analysis, the NCA method was used to test the antecedent conditions, and the results indicated that the effect size of all conditions was below the 0.1 threshold, suggesting that no single condition is necessary for the enhancement of high AGTFP. Specifically, conditions such as DI, DTT, DFD, DIL, DRI, and DGD all showed that they are not essential individual factors. This result further emphasizes the collaborative role of multiple factors in agricultural high-quality development, indicating that the roles of these factors are complementary, not isolated.

Within the context of assessing sufficiency, QCA was employed to unpack the ways conditions combined to generate the sufficient conditions that lead to high AGTFP. The analysis highlighted multiple pathways resulting in high AGTFP constructed from synergies between conditions, rather than one single condition. Some of these pathways were formed as sufficient conditions generated by the combination of conditions, such as the financial-resource dual-drive model, as a sufficient condition describing the combination of digital finance and resource investment, specifically in areas with low levels of digital industry. Additionally, the study conducted a configuration analysis for low AGTFP pathways, describing the “talent island trap” model as a pathway that illustrates the imbalance between demand and supply of digital technology talent, often characterized as a location with an abundance of digital technology talent without a supportive industry or directed investment in resources and finances to support the transformation of talent into a high-quality agricultural development driving force.

The consistency analysis demonstrated the dynamic stability of each driving path, emphasizing a high degree of stability across multiple years. For example, pathways based on digital finance awareness, including financial-government dualway and financial-resource dualway, exhibited a high degree of stability in several years, reflecting the enduring nature of financial capital in high-quality development of agriculture. Conversely, pathways based on infrastructure, such as infrastructure-government dualway, had been initially performing poorly but eventually became more stable, signifying durability associated with infrastructure construction in the long term.

The findings of this study are consistent with those of Zhang et al. (2025) [5] and Ma et al. (2026) [6] on the link between the digital economy and agricultural development, in particular, the interplay between digital finance and government actions. Notably, Zhang et al. (2025) [5] advocate for the importance of a digital government infrastructure in enhancing agricultural management efficiency and better resource allocation, and according to Ma et al. (2026) [6], digital finance can improve agricultural productivity and assist with high-quality development of agriculture via improved fund allocation. However, this study differs from some of the literature in some details. Unlike the “single factor influence model” proposed by luo et al. (2022) [48] and Qin et al. (2025) [49], this study emphasizes that high-quality agricultural development is not driven by a single factor, but by a path composed of multiple conditions, with substitution and complementarity relationships among these paths.

Notably, these findings lend credence to the validity of applying the TOE framework in researching high-quality development of agriculture and reveal the centrality of multi-factor synergies in agricultural green transformation. New perspectives are disclosed in exploring regional differentiated development mechanisms. It provides practical implications for local governments to develop differentiated and precise rural digital development strategies.

4.2. Practical Significance

For policymakers in China and other developing countries, it is important to construct policies that effectively leverage the digital economy to advance high-quality agricultural development, taking into account the unique characteristics of these nations, such as the level of economic development, disparities in digital infrastructure, resource endowments, farmers’ digital skills or literacy, and development level imbalances.

(1) Differentiated Regional Strategies Based on Path Characteristics

Policies to support high-quality agricultural development should be made according to the driving modes identified by regional characteristics. For the financial-government dual-drive type found in the eastern areas, suitable policies should enhance the deep coordination of financial capital and policy guidance to promote innovation in green financial products, including green loans and green bonds, to support the financing of green agricultural projects. Local government agencies should make use of tax incentives and subsidies to direct financial and agricultural resources to green agriculture, thus facilitating the dual-agenda for digital agricultural development and green agriculture. For the infrastructure-government dual-drive type found in the western areas of the regions, adequate policies should focus on strengthening infrastructure development related to digital agriculture and agricultural production, as well as promoting the adoption of digital agricultural technologies, with the government as an “investor.” An adequate policy should aim to invest in infrastructure, including IoT and smart agricultural machinery, while also providing for the management of data and public administration efficiency in relation to agricultural production. In the northeast, the industry-led drive type should have policies to support and facilitate traditional agriculture to integrate into a digital transformation. Policies should promote and encourage partnerships between agricultural enterprises and technology companies to facilitate the digital processing and marketing of agricultural products. Additionally, to strengthen the digital capacities of agricultural enterprises, government should offer adequate technical support and training related to agricultural enterprises. Finally, to guarantee that adequate policies are adequate, a “regional digital agriculture development type identification system” should be established by the agricultural sector to scientifically designate the dominant development path based on regional natural resources and development type.

(2) Differentiated Evaluation Mechanisms Based on Path Characteristics

To facilitate the green transformation of agriculture, an established evaluation mechanism should be based on different dimensions of each pathway. For financial-government dual-drive regions, an assessment should emphasize the ratio of green loans and efficiency of policy coordination, in terms of assessing whether financial support is mobilized for agricultural green discourse and how well policy can coordinate and allocate resources to benefit agricultural green development. For infrastructure-government dual-drive regions, an assessment should highlight the coverage and utilization efficiency of digital infrastructure, notably relating to the breadth and depth of construction of infrastructure and also the extent and actual use and utilization of key infrastructures, such as the internet of things (IoT) and smart agricultural equipment. For industry-led drive regions, the assessment should concern the degree of digitalization in the industrial chain and the green benefits as an outcome. This includes what a deeper application of digital agriculture could take place in traditional agriculture and the efficacy of those transformations. For reliable assessment, it is preferable to establish a digital agriculture policy lab, using digital twins to create a simulated environment with diverse policy combinations in multiple scenarios, using policy to adapt to conditions and to begin to optimize policy; thus achieving “monitoring-evaluation-feedback-optimization” dynamic governance.

(3) Differentiated Talent Development Mechanisms

Establishing a differentiated talent development mechanism is pivotal for promoting high-quality development of agriculture. In areas with a dual driving force of finance-government, the objective is to cultivate composite talents with expertise in both digital finance and policy design. These composite talents not only must master digital finance technologies, but also must understand the core components of policy design and execution to serve as a bridge or consortium member between government entities and financial institutions and promote innovation and execution for green financial products and policies. In regions with a dual driving force of infrastructure-government, talent development should concentrate on cultivating talent who are taught, trained, and educated in the operation and management of digital infrastructure projects. These individuals must possess the knowledge base of modern digital infrastructure construction and management that enables them to plan and execute agricultural digital transformation infrastructure projects to ensure efficient operational construction of the projects. In regions that are driven by the industry, talent development must focus on cultivating people who are capable of digitally integrating the agricultural industry chain by responding to a key factor of positive industry outcomes that is needed to engage and deliver the desired outcomes for the otherwise traditional and modern agriculture industry. These individuals should have established basic industry knowledge and will also have a track record of applying digital technology to enhance traditional processes in innovative ways to support productive outcomes for the entire industry as a whole. Finally, to ensure that the relevant talents are aligned with the developmental needs of their region, a path-talent matching mechanism should be built. This type of mechanism of regional focus provides a framework for designing a talent development framework specific to the dominant paths of development along with industry needs, which provides valid and viable talent development to ensure there is a targeted and functional workforce that can ultimately support the high-quality development of agriculture.

4.3. Limitations and Prospects

Although this study has made certain progress in method integration and path identification, there are still certain limitations. First, this research examines the AGTFP levels across 31 provinces in China, but we have not adequately explored the county or enterprise-level. The coverage of cases is limited. Future studies should incorporate micro-level data, examining counties or enterprises, while still examining the unique practices and effects of high-quality development throughout varying regions and agricultural scales. The case studies will facilitate insights into the enhance understanding of the true transformation processes, in addition to connecting to the impact of changes in regional differences on agricultural digitalization, by doing so this research will be more applicable and richer in terms of findings.

Additionally, the research does not include cross-national comparisons with other countries where digital economies are rapidly growing. Future research could expand its scope by including emerging digital countries such as Brazil, South Africa, and South Korea to conduct cross-national comparisons, which would help explore commonalities and differences in promoting green innovation and high-quality development of agriculture thus provide additional international experiences and lessons for policy development in China and other developing countries.

Finally, the research examines AGTFP in aggregate, possibly ignoring variation across agricultural sub-sectors. For example, there are important distinctions in production methods, resource inputs, and technology requirements that exist between crop production and animal husbandry. Future research could further disaggregate AGTFP by analyzing the high-quality development and green innovation paths of different sub-sectors respectively, thus allowing for a nuanced policy response for different agricultural industries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and B.L.; Methodology, Z.L. and B.L.; Investigation, Z.L.; Data curation, Z.L.; Formal analysis, Z.L.; Visualization, Z.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; Writing—review and editing, B.L.; Supervision, B.L.; Project administration, B.L.; Funding acquisition, B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. B.L. is the corresponding author.

Funding

This work was supported by Major Project of Fundamental Research in Philosophy and Social Sciences for Higher Education Institutions in Henan Province (2024-JCZD-21).

Informed Consent Statement

The corresponding author confirms that consent for displaying the email addresses has been obtained from all authors.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study were obtained from (i) the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS) (

https://www.stats.gov.cn; accessed on 25 August 2025), (ii) the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China (MIIT) (

https://www.miit.gov.cn; accessed on 25 August 2025), and (iii) the Peking University Digital Finance Research Center (

https://dc.pku.edu.cn/dfinlab/; accessed on 25 August 2025). Some data providers may require institutional subscriptions or licenses.

Acknowledgments

The author, Zihang Liu, would like to express sincere gratitude to Prof. Bingjun Li for his continuous guidance, valuable suggestions, and encouragement throughout this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang J, Dong Y, Wang H. Research on the impact and mechanism of digital economy on China’s food production capacity[J]. Scientific Reports, 2024, 14(1): 27292. [CrossRef]

- Ma G, Dai X, Luo Y. The effect of farmland transfer on agricultural green total factor productivity: evidence from rural China[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2023, 20(3): 2130.

- Lu S, Zhuang J, Sun Z, et al. How can rural digitalization improve agricultural green total factor productivity: Empirical evidence from counties in China[J]. Heliyon, 2024, 10(15). [CrossRef]

- Zhou L, Zhang S, Zhou C, et al. The impact of the digital economy on high-quality agricultural development——Based on the regulatory effects of financial development[J]. Plos one, 2024, 19(3): e0293538.

- Zhang G, Zhang C, Liu T. How does the digital economy impact the high-quality development of agriculture? An empirical test based on the spatial Durbin model[J]. Digital Economy and Sustainable Development, 2025, 3(1): 18.

- Ma G, Qin R, Lei S, et al. Influence of data elements on China’s agricultural green total factor productivity[J]. Scientific Reports, 2025, 15(1): 31358. [CrossRef]

- Cai Y, Wang L. Impact of Digital Economy on Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity: Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of the” Broadband China” Strategy[J]. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2025, 9: 1607567.

- Ma M, Li J, Song J, et al. Digital agriculture’s impact on carbon dioxide emissions varies with the economic development of Chinese provinces[J]. Communications Earth & Environment, 2024, 5(1): 621.

- Han J, Wei W, Ge W, et al. Digital Technology and Agricultural Production Agglomeration: Mechanisms, Spatial Spillovers, and Heterogeneous Effects in China[J]. Sustainability, 2025, 17(10): 4387.

- Ning L, Yao D. The impact of digital transformation on supply chain capabilities and supply chain competitive performance[J]. Sustainability, 2023, 15(13): 10107. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Wan J, Dai Z. How does digital technology application empower specialty agricultural farmers? Evidence from Chinese litchi farmers[J]. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2024, 8: 1444192.

- Teng Y, Zheng J, Li Y, et al. Optimizing digital transformation paths for industrial clusters: Insights from a simulation[J]. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2024, 200: 123170.

- Li Z, Zhou Q, Wang K. The impact of the digital economy on industrial structure upgrading in resource-based cities: Evidence from China[J]. Plos one, 2024, 19(2): e0298694.

- Guo J, Chen L, Kang X. Digital inclusive finance and agricultural green development in China: A panel analysis (2013–2022)[J]. Finance Research Letters, 2024, 69: 106173. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Digital finance and agricultural green total factor productivity: Evidence from China. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2024, 76, 214–229.

- Jin S, Zhong Z. Impact of digital inclusive finance on agricultural total factor productivity in Zhejiang Province from the perspective of integrated development of rural industries[J]. Plos one, 2024, 19(4): e0298034.

- Zhang J, Zhang L, Zhang K, et al. Can internet use promote farmers’ diversity in green production technology adoption? Empirical evidence from rural China[J]. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 2025, 12(1): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Depietro R, Wiarda E, Fleischer M. The context for change: Organization, technology and environment[J]. The processes of technological innovation, 1990, 199(0): 151-175.

- Zhu K, Dong S, Xu S X, et al. Innovation diffusion in global contexts: determinants of post-adoption digital transformation of European companies[J]. European journal of information systems, 2006, 15(6): 601-616.

- Zhao, X.; et al. A study on the influencing factors of corporate digital transformation based on the TOE framework. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 12.

- Gao, Y.; Wang, S. P.; Han, Z. M. Agricultural digitalization and the development of new-type agricultural management entities. Journal of Zhongnan University of Economics and Law 2023, 5, 108–121.

- Nagy A, Tumiwa J, Arie F, et al. A meta-analysis of the impact of TOE adoption on smart agriculture SMEs performance[J]. Plos one, 2025, 20(2): e0310105. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. Y.; Xu, Q. Design of an intelligent greenhouse water-saving irrigation control system. Modern Agricultural Equipment 2022, 43, 4.

- Luo, Q. F.; Zhao, Q. F.; Zhang, L. X. The theoretical framework, efficiency-enhancing mechanism and realization path of digital technology empowering high-quality agricultural development. Contemporary Economics and Management 2022, 44, 7, 49–56.

- Zhang Y, Ma L, Wei F. Digital Infrastructure and Agricultural Global Value Chain Participation: Impacts on Export Value-Added[J]. Agriculture, 2025, 15(15): 1588.

- Wang S, Yang Y, Yin H, et al. Towards digital transformation of agriculture for sustainable development in China: experience and lessons learned[J]. Sustainability, 2025, 17(8): 3756. [CrossRef]

- Liao F, Zheng Y, Yang D. Digital transformation in rural governance: unraveling the micro-mechanisms and the role of government subsidies[J]. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 2025, 12(1): 1-14.

- Zou X, Min J, Meng S, et al. Can digital governance stimulate green development? Evidence from the program of “pilot cities regarding information for public well-being” in China[J]. Frontiers in Public Health, 2025, 12: 1463532.

- Finger R. Digital innovations for sustainable and resilient agricultural systems[J]. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 2023, 50(4): 1277-1309. [CrossRef]

- Hong X, Chen Q, Wang N. The impact of digital inclusive finance on the agricultural factor mismatch of agriculture-related enterprises[J]. Finance Research Letters, 2024, 59: 104774.

- Carter M R. Can digitally--enabled financial instruments secure an inclusive agricultural transformation?[J]. Agricultural Economics, 2022, 53(6): 953-967. [CrossRef]

- Choruma D J, Dirwai T L, Mutenje M J, et al. Digitalisation in agriculture: A scoping review of technologies in practice, challenges, and opportunities for smallholder farmers in sub-saharan africa[J]. Journal of agriculture and food research, 2024, 18: 101286.

- Sauvagerd M, Mayer M, Hartmann M. Digital platforms in the agricultural sector[J]. Big Data & Society, 2024, 2024(4): 1-16.

- Ragin C C. Fuzzy-set social science[M]. University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- Verweij S, Vis B. Three strategies to track configurations over time with Qualitative Comparative Analysis[J]. European Political Science Review, 2021, 13(1): 95-111.

- Dul J. Identifying single necessary conditions with NCA and fsQCA[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2016, 69(4): 1516-1523. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Li R, Zhang J. Understanding the green total factor productivity of manufacturing industry in China: analysis based on the super-SBM model with undesirable outputs[J]. Sustainability, 2022, 14(15): 9310.

- Zhou Z, Duan J, Geng S, et al. Spatial network and driving factors of agricultural green total factor productivity in China[J]. Energies, 2023, 16(14): 5380.

- Zhou, M.; Wang, L.; Guojia, H. Measurement and temporal–spatial comparison of the integration of the digital economy and the real economy in the context of new quality productivity: based on the patent co-classification method. Journal of Quantitative Techniques in Economics 2024, 41, 7, 5–27.

- Zhang Y, Ji M, Zheng X. Digital economy, agricultural technology innovation, and agricultural green total factor productivity[J]. Sage Open, 2023, 13(3): 21582440231194388. [CrossRef]

- Ehlers M H, Huber R, Finger R. Agricultural policy in the era of digitalisation[J]. Food policy, 2021, 100: 102019.

- Chen Z W, Tang C. Impact of digital economy development on agricultural carbon emissions and its temporal and spatial effects[J]. Sci. Tochnol. Manag. Res, 2023, 43: 137-146.

- Su, J.; et al. Evaluation of digital economy development level based on four-dimensional index system: evidence from China. Frontiers in Environmental Economics 2022, 22, 1396615.

- Fainshmidt S, Witt M A, Aguilera R V, et al. The contributions of qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to international business research[J]. Journal of international business studies, 2020, 51(4): 455-466. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y. Z.; Jia, L. D. Configuration perspective and qualitative comparative analysis (QCA): a new way of management research. Management World 2017, 6, 155–167.

- Fiss P C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research[J]. Academy of management journal, 2011, 54(2): 393-420.

- Du, Y. Z.; Liu, Q. C.; Chen, K. W.; Xiao, R. Q.; Li, S. S. Robustness test of business environment configurations for high total factor productivity: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis approach. Management World 2022, 9.

- Luo Y, Mensah C N, Lu Z, et al. Environmental regulation and green total factor productivity in China: A perspective of Porter’s and Compliance Hypothesis[J]. Ecological Indicators, 2022, 145: 109744.

- Qin L, Liu S, Xie F. Green Finance and Green Total Factor Productivity: Impact Mechanisms, Threshold Characteristics, and Spatial Effects[J]. SAGE Open, 2025, 15(2): 21582440251345879. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).