Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.2.1. Search Strategy

2.2.2. Eligibility Criteria

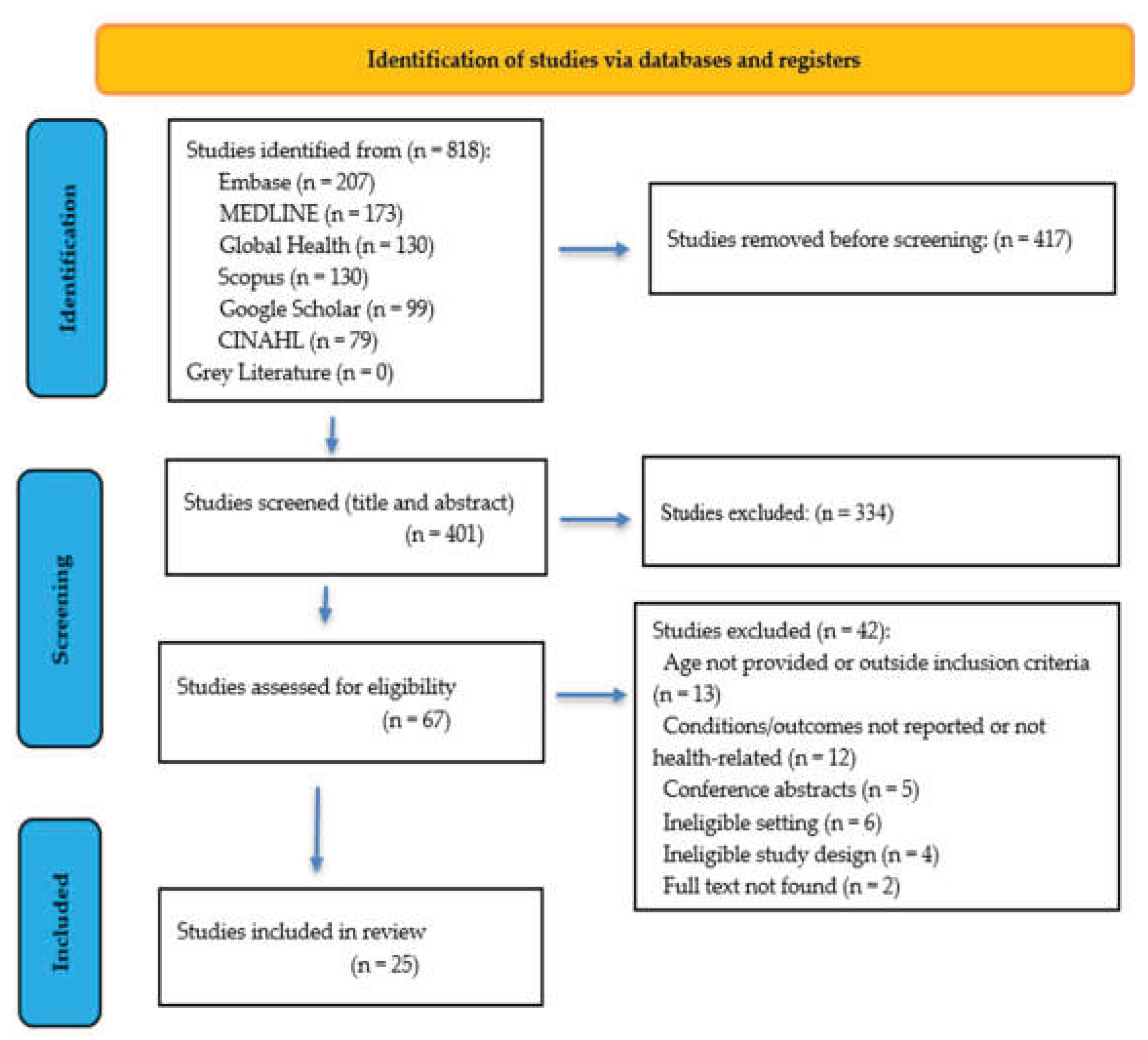

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Synthesis of Extracted Results

3. Results

3.1. Studies Included

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Refugee Child Health Conditions and Outcomes in Canada

3.3.1. Communicable Diseases

3.3.2. Non-Communicable Diseases

3.3.3. Developmental and Mental Health of Refugee Children

3.4. Measurement of Refugee Child Health Conditions and Outcomes by Refugee-Serving PHCs

3.4.1. Communicable Diseases

3.4.2. Non-Communicable Diseases

Growth/Malnutrition/Bone Density

Anaemia/Heamatological Conditions

Immunization Status

Diabetes

Oral Health

Eye Health

3.4.3. Developmental and Mental Health

4. Discussion

4.1. Refugee Child Health Conditions and Outcomes

4.2. Measurement Inconsistencies and Their Implications for Refugee Child Health Assessment

4.3. Inconsistent Data Collection and Its Consequences for Refugee Children

4.3.1. Gaps in Health Conditions and Outcomes

4.3.2. Measurement Gaps and Methodological Limitations

4.4. Implications for Practice, Research, and Policy

4.4.1. Practice

4.4.2. Research

4.4.3. Policy

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| CDC | Centre for Disease Control |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| CMAJ | Canadian Medical Association Journal |

| DPTP | Diptheria/Pertussis/Tetanus/Polio |

| DXA | Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

| EIA | Enzyme Immunoassay |

| EMR | Electronic Medical Record |

| GARs | Government-Assisted Refugees |

| Hib | Haemophilys influenza B |

| ICD-10-CA | International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, the 10th Revision, Canada |

| IGRA | Interferon-Gamma Release Assay |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| LTBI | Latent tuberculosis infections |

| NCHC | New Canadians Health Centre |

| PHCs | Primary Health Centres/Clinics |

| PICO | Patient, Intervention Comparison and Outcome |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews |

| PSRs | Privately Sponsored Refugees |

| REC | Research and Evaluation Committee |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix

Appendix A.1

Appendix B.1

| Study ID | Study Aim | Study Design | Province | Population Age | Country/Region of Origin |

| Higgins 2023 | A systematic review which describes the extent, quality and cultural appropriateness of current research on the health conditions of refugee children aged 0-6 years settled in high-income countries | Systematic Review | Not Canadian specific, but includes papers in Canada | 0-6 | High income countries |

| Hoover 2017 | To identify the risk determinants of caries and record oral hygiene status in recent immigrant and refugee children | Cross sectional | Saskatchewan | Refugee children: 3-6 years; 6-14 years; 14-16 years Immigrant children: 3-6 years; 6-14 years; 14-16 years |

Indian subcontinent, Asia, and rest of the world |

| Lane 2019 | To characterize the health and nutritional status of immigrant and refugee children in Canada, specifically focusing on their bone mineral content and vitamin D status | Cross sectional; Mixed-methods research | Saskatchewan | 3-4 years; 5-7 years; 8-10 years; 11-13 years | Immigrants: Middle East (e.g., Iran, Iraq, Pakistan); Asia (e.g., Burma, India, Philippines); Africa; Latin America; Eastern Europe; Western Europe and United States Refugees: Middle East (e.g., Iran, Iraq, Pakistan); Asia (e.g., Burma, India, Philippines); Africa; Latin America; Eastern Europe |

| Bhayana 2018 | To provide a framework for primary care providers to approach developmental disabilities in both refugee and nonrefugee immigrant populations | Review | NA | NA | NA |

| BinYameen 2019 | To assess the ocular health status of Syrian pediatric refugees in Canada and report the prevalence of vision impairment within this population | Multi-methods Cross sectional study, | Ontario | <1 year; 1-3 years; 4-6 years; 7-9; 10-12; 13-15; 15-18 | Syria |

| Guttmann 2020 | To evaluate factors associated with uptake of a financial incentive for developmental screening at an enhanced 18-month well-child visit (EWCV) in Ontario, Canada. | Cross sectional study; Retrospective chart review | Ontario | 17-24 months. | Not specified |

| Suppiah 2023 | To assess growth indicators for resettled Yazidi and non-Yazidi pediatric refugees from Syria and Iraq. | Retrospective chart review cohort study | Alberta | < 5 years and 5 years or older | Iraq and Syria |

| Gagnon 2013 | To determine whether refugee or asylum-seeking women or their infants experience a greater number or a different distribution of professionally identified health concerns after birth than immigrant or Canadian-born women. | Quantitative research; Longitudinal (cohort study), Retrospective study | Ontario and Quebec | Infants | Refugees: Africa; Asia; Europe; Latin America Asylum-Seekers: Africa; Asia; Europe; Latin America Immigrants Africa; Asia; Europe; Latin America; Northern America |

| Aucoin 2013 | To determine the 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) serum levels in refugee women of childbearing age and in refugee children; to compare their 25(OH)D levels with the recommended levels in order to determine the prevalence of deficiency; to compare their 25(OH)D levels with those in the general Canadian population in the appropriate age and sex groups; and to investigate the association of vitamin D deficiency with potential risk factors | Cross sectional study; Retrospective chart review | Alberta | 0-5 years; 6-11 years; 12-19 years; 20-39 years; 40-45 years | Africa; Asia; Middle East; South America; Other |

| Dorman 2017 | Characterize the demographics and health status of North Korean refugees who have accessed care at a refugee clinic in Toronto | Retrospective chart review; cross sectional, Other: Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) methodology | Ontario | All | North Korea; Swaziland; Saudi Arabia; Croatia; Iran; Afghanistan; Eritrea; Ethiopia; Nigeria; North Korea; Hungary; Other |

| DeVetten 2017 | To determine the prevalence of intestinal parasites and rates of stool testing compliance, as well as associated patient characteristics | Retrospective chart review, cross sectional | Alberta | < 6 years; 6-18 years; 19-39 years and 40 years | Sub-Saharan Africa; North Africa; Middle East; Asia; Latin America; Europe or North America |

| Taseen 2017 | To determine the level of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-(OH) D) in the paediatric refugee population residing in Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada and to determine variables predicting vitamin D levels including age, sex, BMI, influence of season, ethnicity, previous country of residence and duration of stay in Canada from time of arrival. | Cross sectional study; Retrospective chart review | Quebec | <3 years; 3 - <6 years; 6 - <12 years; 12 years | Afghanistan; Iraq; Bhutan, Columbia, Guatemala; and Central African Republic |

| Darwish 2020 | To describe the population of Syrian refugees who received care at temporary triage clinics, the health issues addressed, and the health services used in the clinics | Non-randomized experimental study; Cross sectional study; Retrospective chart review | Ontario | 1 month - 62 years (55% children) | Syria |

| Muller 2022 | This study aims to investigate the prevalence and species of intestinal parasites identified in stool ova and parasite (O&P) specimens in a sample of newly arrived refugees in Toronto, Canada. | Retrospective chart review, cross sectional | Ontario | 0-9 years; 10-19 year; 20-29 years; 30-39 years; 40-49 year; 50-59 years; 60-69 years; 70+ | East Asia & Pacific; Europe & Central Asia; Latin America & Caribbean; Middle East & North Africa; North America; South Asia; and Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Harwood-Johnson 2023 | To measure LTBI treatment acceptance and completion outcomes of LTBI treatment at the REACH clinic in Saskatoon | Retrospective chart review, cross sectional | Saskatchewan | 6 months or older | Africa; Eastern Europe, Mediterranean; Southeast Asia |

| Kamali 2023 | To examine differences in mental health-related service contacts between immigrant, refugee, racial and ethnic minoritized children and youth, and the extent to which social, and economic characteristics account for group differences | Other: Retrospective correlational analysts (cross sectional) | Ontario | 4 - 17 yrs | NA |

| Smati 2024 | To conduct a detailed retrospective cohort investigation of the sociodemographic characteristics, health conditions, and clinic utilization patterns of Afghan refugee patients resettled in Calgary, Canada between 2011 and 2020 | Retrospective chart review; Other: community-engaged | Alberta | 0-4 years; 5-11 years; 12-17 years | Afghanistan |

| Redditt 2015b | To determine the prevalence of selected chronic diseases among newly arrived refugee patients and explore associations with key demographic factors | Retrospective chart review, cross-sectional | Ontario | 0-4 years; 5-14 years; 15-24 years; 25-34 years; 35-44 years; 45-54 years; 55-64 years; 65+ years | Africa; Americas; Asia; Eastern Mediterranean; Europe; North America |

| Redditt 2015 | To determine the prevalence of selected infectious diseases among newly arrived refugee patients and whether there is variation by key demographic factors | Retrospective chart review, cross-sectional | Ontario | 0-4 years; 5-14 years; 15-24 years; 25-34 years; 35-44 years; 45-54 years; 55-64 years; 65+ years | Africa; Americas; Asia; Eastern Mediterranean; Europe |

| Gadermann 2022 | Estimate the administrative data-derived diagnostic prevalence of mental disorders (conduct, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], and mood/anxiety) for refugee, immigrant, and nonimmigrant children and youth in British Columbia, Canada. | Retrospective chart review, cross sectional | British Columbia | 0-19 years | NA |

| Salehi 2015 | To describe selected anthropometric and health status variables among immigrant and refugee children ≤6 years of age within an inner-city clinic in Toronto, Ontario | Cross sectional; Retrospective chart review | Ontario | 0-6 years | Afghanistan; Myanmar; and Columbia |

| Guttmann 2008 | To investigate access to effective primary health care services in children of new immigrants to Canada by assessing immunization coverage at age 2 | Longitudinal (Cohort study) | Ontario | 17-24 months | Latin/Central America, Western Europe, North America; Eastern Europe; Middle East; Africa; Southeast and Northeast Asia, Oceania; South Asia |

| Beukeboom 2018 | To examine the variation among ethnic populations in the prevalence of anemia, vitamin D and B12 deficiencies among refugee children. The study aims to determine the frequency and distribution of these deficiencies among refugee children, stratified by country of origin and age group |

Cross sectional study; Retrospective chart review | Ontario | 0-4 year; 5-11 years; 12-16 years | Iraq; Somalia; Myanmar; Afghanistan; Other |

| Lane 2018 | Explore the health and nutritional status of immigrant and refugee children in Canada, identifying chronic disease risks and health inequities influenced by socioeconomic and lifestyle factors, to inform public health interventions for newcomer families. | Retrospective, Cross sectional study; Mixed-methods research | 3-13 years | ||

| Moreau 2019 | To assess the oral health status of refugee children in comparison with that of Canadian children and investigate the extent to which demographic factors are associated with caries experience in this population | Retrospective chart review | Quebec | 1-14 years | Africa; Latin America; North America; Middle East; Europe; and Asia |

Appendix B.2

| Study ID | Outcomes | Measurement Approach Defined | ||

| Communicable | Non- communicable | Developmental and mental health | ||

| Higgins 2023 | X | X | X | NA |

| Hoover 2017 | X | Clinical Examinations - Assessment of the presence of the number of decayed, missing and filled teeth (dmft/DMFT). Oral hygiene status evaluated by Simplified Oral Hygiene Index (OHIS). | ||

| Lane 2019 | X | Physical exam: Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Blood sample for serum vitamin D analysis. Questionnaire: Modified version of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2008 socio-economic and demographic questionnaire, the CCHS Food security Questionnaire, Statistics Canada's Children's Physical Activity questionnaire, and serial 24 h dietary recalls. |

||

| Bhayana 2018 | X | NA | ||

| BinYameen 2019 | X | Visual screening, slit-lamp examination, direct dilated fundoscopy, and refractive index measurements. | ||

| Guttmann 2020 | X | Immunization Rates (Categorized as 85%, 90%, or >95% complete immunizations) and birth weight | ||

| Suppiah 2023 | X | Height and Weight | ||

| Gagnon 2013 | X | X | Project nurse assessment post-birth, 7-10 days and four months. Assessed for the presence of health concerns based on a list developed from standards for postpartum care. Nipissing Assessment Tool Vitamin D supplements Infant weight |

|

| Aucoin 2013 | X | Laboratory measurement using the standard DiaSorin Liaison 25(OH)D vitamin D assay. | ||

| Dorman 2017 | X | X | Glucose (fasting blood sugar, random blood sugar, and hemoglobin A1c), hepatitis B serology (surface antigen, surface antibody, core antibody), BMI | |

| DeVetten 2017 | X | Stool ova and parasite test - All specimens were first screened for Giardia lamblia and Cyptospokidium using an enzyme immunoassay, then positives were confirmed with direct fluorescent antibody testing. | ||

| Taseen 2017 | X | Laboratory measurements of 25-(OH)D levels determined by Elecsys Vitamin D Total Assay. | ||

| Darwish 2020 | X | X | X | NA |

| Muller 2022 | X | X | BMI, WHO Anemia guidelines, height, weight | |

| Harwood-Johnson 2023 | X | QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus 4-tube assay (IGRA) and Mantoux method (TST) | ||

| Kamali 2023 | X | Questionnaire tool: 2014 Ontario Child Health Study (OCHS) | ||

| Smati 2024 | X | X | X | Based on the ICD-10 |

| Redditt 2015b | X | Hemoglobin Levels and diabetes screening test results (fasting blood glucose, random blood glucose, or hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] measurement) |

||

| Redditt 2015 | X | HIV serology, hepatitis B serology (surface antigen and surface antibody), hepatitis C antibody, Strongyloides serology, Schistosoma serology, stool ova and parasites, gonorrhea and chlamydia testing (culture or nucleic acid amplification test), syphilis testing, and varicella immune status (varicella immunoglobulin G antibody) | ||

| Gadermann 2022 | X | Identified Indicators using symptoms |

||

| Salehi 2015 | X | X | Height and weight abnormalities, determined by the WHO Child Growth Standards (using a cut-off z-score of ≤−2, which indicates a percentile measurement of approximately ≤2.3). Data were also collected regarding the presence of: iron deficiency (defined as ferritin levels below the age-specific laboratory lower reference limits); anemia (defined as hemoglobin levels below the age-specific laboratory lower reference limits); parasitic enteric infections (positive stool culture for ova and parasites); hepatitis B (positive hepatitis B surface antigen levels); HIV (positive ELISA test); and elevated lead levels (lead levels ≥ 0.48 μmol/L). |

|

| Guttmann 2008 | X | Five immunizations given after age 7 weeks as being up to date, representing the recommended 3doses and 1booster of Diptheria/Pertussis/Tetanus/Polio/ Haemophilys influenza B (DPTP/Hib) given at 2, 4, 6, and 18 months, and 1 combined dose of measles, mumps, and rubella given after age 12 months. |

||

| Beukeboom 2018 | X | "Hemoglobin Levels: Hemoglobin levels were measured to evaluate anemia among refugee children. The cut-off levels for anemia were based on age and sex-specific guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO). Vitamin D Levels: Serum 25(OH)D levels were measured to assess vitamin D status. Vitamin D is crucial for bone health, immune function, and overall physical development. Vitamin B12 Levels: Serum vitamin B12 levels were measured to determine the prevalence of vitamin B12" |

||

| Lane 2018 | X | Physical exam: Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Blood sample for serum vitamin D analysis. Questionnaire: Modified version of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2008 socio-economic and demographic questionnaire, the CCHS Food security Questionnaire, Statistics Canada's Children's Physical Activity questionnaire, and serial 24h dietary recalls. Blood sample to assess serum glucose, total cholesterol, and serum vitamin D. Anthropometric measurements including height, weight, and waist circumference |

||

| Moreau 2019 | X | Dental caries diagnosis (dmft/DMFT) for primary and permanent teeth. Oral hygiene was scored using the simplified oral hygiene index. Gingival health status was measured visually without probing. Patients' malocclusion assessment looked at crossbite, open bite, overbite, and overjet. | ||

References

- UNHCR. (2025). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2024. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2024. (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Concern Worldwide. (2025). The global refugee crisis, explained. Concern Worldwide. https://www.concern.net/news/global-refugee-crisis-explained. (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- IRCC. (2024). 2024 annual report to Parliament on immigration. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/documents/pdf/english/corporate/publications-manuals/annual-report-2024-en.pdf. (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Dowell, A., & Turner, N. Child health indicators: From theoretical frameworks to practical reality? The British Journal of General Practice, 2014, 64(629), 608–609. [CrossRef]

- Khan, I., & Leventhal, B. L. Developmental Delay. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing., 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562231/.

- Kirmayer, L., & Jarvis, G. Culturally Responsive Services as a Path to Equity in Mental Healthcare. HealthcarePapers, 2019, 18(2), 11–23. [CrossRef]

- Sim, A., Ahmad, A., Hammad, L., Shalaby, Y., & Georgiades, K. Reimagining mental health care for newcomer children and families: A qualitative framework analysis of service provider perspectives. BMC Health Services Research, 2023, 23(1), 699. [CrossRef]

- Eruyar, S., Huemer, J., & Vostanis, P. Review: How should child mental health services respond to the refugee crisis? Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 2018. 23(4), 303–312. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J., Ruacho, H. C., Zeng, X., & Franklin, C. A Scoping Review of Family-Based Interventions for Immigrant/Refugee Children: Exploring Intergenerational Trauma. Community Mental Health Journal 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D. A Scoping Review of Interventions Delivered by Peers to Support the Resettlement Process of Refugees and Asylum Seekers. Trauma Care 2022, 2(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Baauw, A., Kist-van Holthe, J., Slattery, B., Heymans, M., Chinapaw, M., & Van Goudoever, H. Health needs of refugee children identified on arrival in reception countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 2019a, 3(1), e000516. [CrossRef]

- Frounfelker, R. L., Miconi, D., Farrar, J., Brooks, M. A., Rousseau, C., & Betancourt, T. S. Mental Health of Refugee Children and Youth: Epidemiology, Interventions, and Future Directions. Annual Review of Public Health, 41 2020, 159–176. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J., & Evennett, J. The health needs of asylum-seeking children. The British Journal of General Practice, 2018, 68(670), 238. [CrossRef]

- Horne, M. Identifying the Health Needs of Communities and Populations. In Public Health and Society 2003, pp. 119–132). Palgrave, London. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2021, October 21). Common health needs of refugees and migrants: Literature review. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033108. (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Refugee Health Coalition . (2020). Refugee health community engagement: Project report. Available online at: https://www.refugeehealthcoalition.ca/_files/ugd/fda787_0f3b634eff7c42d29ca35dcb57c9cff7.pdf. (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Salami, B., Olukotun, M., Vastani, M., Amodu, O., Tetreault, B., Obegu, P. O., Plaquin, J., & Sanni, O. Immigrant child health in Canada: A scoping review. BMJ Global Health, 2022, 7(4). [CrossRef]

- Scharf, R. J., Zheng, C., Briscoe Abath, C., & Martin-Herz, S. P. Developmental Concerns in Children Coming to the United States as Refugees. Pediatrics, 2021, 147(6), e2020030130. [CrossRef]

- Gold, A. W., Perplies, C., Biddle, L., & Bozorgmehr, K. Primary healthcare models for refugees involving nurses: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Global Health, 2025, 10(3), e018105. [CrossRef]

- Haight, J., Kruth, M., Gokiert, R., Botwe, A., Dzunic-Wachilonga, A., Neves, C., Velasquez, A., Whalen-Browne, M., Ladha, T., & Rogers, C. A principles-based community health center for addressing refugee health: The New Canadians Health Centre. Frontiers in Public Health, 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Bell, R., Bloomer, E., & Goldblatt, P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. The Lancet, 2012, 380(9846), 1011–1029. [CrossRef]

- Matlin, S. A., Depoux, A., Schütte, S., Flahault, A., & Saso, L. Migrants’ and refugees’ health: Towards an agenda of solutions. Public Health Reviews, 2018, 39(1), 27. [CrossRef]

- Pottie, K., Hui, C., Rahman, P., Ingleby, D., Akl, E. A., Russell, G., Ling, L., Wickramage, K., Mosca, D., & Brindis, C. D. Building Responsive Health Systems to Help Communities Affected by Migration: An International Delphi Consensus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2017, 14(2), 144. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. (2018). The life-course approach: from theory to practice: case stories from two small countries in Europe. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/342210. (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- WHO. (2018b). The life-course approach: From theory to practice. Case stories from two small countries in Europe. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/342210. (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023, July 7). Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: Monitoring framework, Summary. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/cultural-safety-health-care-framework/contents/summary. (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Baba, L. Cultural Safety in First Nations, Inuit and Métis Public Health. 2013.

- Browne, A. J., Varcoe, C., Ford-Gilboe, M., Nadine Wathen, C., Smye, V., Jackson, B. E., Wallace, B., Pauly, B. (Bernie), Herbert, C. P., Lavoie, J. G., Wong, S. T., & Blanchet Garneau, A. Disruption as opportunity: Impacts of an organizational health equity intervention in primary care clinics. International Journal for Equity in Health, 2018, 17(1), 154. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S.-J., & Reid, P. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 2019, 18(1), 174. [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, I., Oltrogge, J. H., Pruskil, S., Mews, C., Schlichting, D., Jahnke, M., Wagner, H.-O., Lühmann, D., & Scherer, M. Referrals to secondary care in an outpatient primary care walk-in clinic for refugees in Germany: Results from a secondary data analysis based on electronic medical records. BMJ Open, 2020, 10(10), e035625. [CrossRef]

- Klas, J., Grzywacz, A., Kulszo, K., Grunwald, A., Kluz, N., Makaryczew, M., & Samardakiewicz, M. Challenges in the Medical and Psychosocial Care of the Paediatric Refugee-A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022, 19(17), 10656. [CrossRef]

- Gadeberg, A. K., Montgomery, E., Frederiksen, H. W., & Norredam, M. Assessing trauma and mental health in refugee children and youth: A systematic review of validated screening and measurement tools. European Journal of Public Health, 2017, 27(3), 439–446. [CrossRef]

- Gervais, C., Daoust-Zidane, N., Thomson-Sweeny, J., Campeau, M., & Côté, I. Safety at the Heart of Well-Being of Migrant-Background Children in Canada. Child Indicators Research, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Prior, A., Vestergaard, C. H., Vedsted, P., Smith, S. M., Virgilsen, L. F., Rasmussen, L. A., & Fenger-Grøn, M. Healthcare fragmentation, multimorbidity, potentially inappropriate medication, and mortality: A Danish nationwide cohort study. BMC Medicine, 2023, 21(1), 305. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C., Gartland, D., Yelland, J., Brown, S., Szwarc, J., Kaplan, I., Paxton, G., & Riggs, E. Refugee child health: A systematic review of health conditions in children aged 0–6 years living in high-income countries. Global Health Promotion, 2023, 30(4), 45–55. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 2020, 18(10), 2119–2126. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H., Garritty, C. M., Hempel, S., Horsley, T., Langlois, E. V., Lillie, E., O’Brien, K. K., Tunçalp, Ӧzge, Wilson, M. G., Zarin, W., & Tricco, A. C. Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Systematic Reviews, 2021, 10(1), 263. [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N., & Duran, B. Community-Based Participatory Research Contributions to Intervention Research: The Intersection of Science and Practice to Improve Health Equity. American Journal of Public Health, 2010, 100(Suppl 1), S40–S46. [CrossRef]

- Minkler, M., & Wallerstein, N. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass. 2008.

- Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. Published 2007 Jun 15. [CrossRef]

- Covidence systematic review software, (2025). Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org. (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- World Health Organization. Country groupings [Internet]. Geneva: WHO. Available from: https://www.who.int/observatories/global-observatory-on-health-research-and-development/classifications-and-standards/country-groupings. [accessed June 17 2025].

- Hoover, Jay et al. “Risk Determinants of Dental Caries and Oral Hygiene Status in 3-15 Year-Old Recent Immigrant and Refugee Children in Saskatchewan, Canada: A Pilot Study.” Journal of immigrant and minority health 2017, vol. 19,6: 1315-1321. [CrossRef]

- Lane, Ginny et al. “Canadian newcomer children's bone health and vitamin D status.” Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme 2019, vol. 44,7: 796-803. [CrossRef]

- Bhayana A, Bhayana B. Approach to developmental disabilities in newcomer families. Can Fam Physician. 2018, 64(8):567-573.

- Bin Yameen, Tarek Abdullah et al. “Visual impairment and unmet eye care needs among a Syrian pediatric refugee population in a Canadian city.” Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie 2019, vol. 54,6: 668-673. [CrossRef]

- Guttmann, Astrid et al. “Implementation of a Physician Incentive Program for 18-Month Developmental Screening in Ontario, Canada.” The Journal of pediatrics 2020, vol. 226: 213-220.e1. [CrossRef]

- Suppiah, Roopa et al. “Stunting and Overweight Prevalence Among Resettled Yazidi, Syrian, and Iraqi Pediatric Refugees.” JAMA pediatrics 2023, vol. 177,2: 203-204. [CrossRef]

- Gagnon AJ, Dougherty G, Wahoush O, et al. International migration to Canada: the post-birth health of mothers and infants by immigration class. Soc Sci Med. 2013, 76(1):197-207. [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, Michael et al. “Vitamin D status of refugees arriving in Canada: findings from the Calgary Refugee Health Program.” Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien 2013, vol. 59,4: e188-94.

- Dorman, Katie et al. “Health Status of North Korean Refugees in Toronto: A Community Based Participatory Research Study.” Journal of immigrant and minority health 2017, vol. 19,1: 15-23. [CrossRef]

- DeVetten G, Dirksen M, Weaver R, et al. Parasitic stool testing in newly arrived refugees in Calgary, Alta. CFP 2017, 63:e518–e525.

- Taseen K, Beaulieu G. Vitamin D levels and influencing predictors in refugee children in Sherbrooke (Quebec), Canada. J Paediatr Child Health 2017; 22:307–311. [CrossRef]

- Darwish, Wais. and Laura Muldoon. “Acute primary health care needs of Syrian refugees immediately after arrival to Canada” Canadian Family Physician 2020, vol. 66,1: e30–e38.

- Müller, Frank et al. “Intestinal parasites in stool testing among refugees at a primary care clinic in Toronto, Canada.” BMC infectious diseases 2022, vol. 22,1 249. [CrossRef]

- Harwood-Johnson, Emily et al. “Community treatment of latent tuberculosis in child and adult refugee populations: outcomes and successes.” Frontiers in public health 2023, vol. 11 1225217. [CrossRef]

- Kamali, Mahdis et al. “Social Disparities in Mental Health Service Use Among Children and Youth in Ontario: Evidence From a General, Population-Based Survey.” Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie 2023, vol. 68,8: 596-604. [CrossRef]

- Smati, Hannah & Hassan, Nour & Essar, Mohammad & Abdaly, Fawzia & Noori, Shayesta & Grewal, Rabina & Norrie, Eric & Talavlikar, Rachel & Bietz, Julia & Kimball, Sarah & Coakley, Coakley & Chatterjee, Avik & Fabreau, Gabriel. Health status and care utilization among Afghan refugees newly resettled in Calgary, Canada between 2011-2020. 2024. 10.1101/2024.06.21.24309182.

- Reddit V, Granziano D, Janakiram P, et al. Health status of newly arrived refugees in Toronto, Ont: Part 2: chronic diseases: CFP 2015; 61:e310-e315.

- Redditt V, Janakiram P, Graziano D, et al. Health status of newly arrived refugees in Toronto, Ont: Part 1: infectious diseases. CFP 2015; 61:e303–e309.

- Gadermann, Anne M et al. “Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders Among Immigrant, Refugee, and Nonimmigrant Children and Youth in British Columbia, Canada.” JAMA network open 2022, vol. 5,2 e2144934. [CrossRef]

- Salehi L, Lofters AK, Hoffmann SM, Polsky JY, Rouleau KD. Health and growth status of immigrant and refugee children in Toronto, Ontario: a retrospective chart review. Paediatrics & child health. 2015, 20(8):e38-42. [CrossRef]

- Guttmann, Astrid et al. “Immunization coverage among young children of urban immigrant mothers: findings from a universal health care system.” Ambulatory pediatrics : the official journal of the Ambulatory Pediatric Association 2008, vol. 8,3: 205-9. [CrossRef]

- Beukeboom C, Arya N. Prevalence of Nutritional Deficiencies Among Populations of Newly Arriving Government Assisted Refugee Children to Kitchener/Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. J Immigr Minor Health 2018, 20:1317–1323. [CrossRef]

- Lane, Ginny et al. “Chronic health disparities among refugee and immigrant children in Canada.” Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme 2018, vol. 43,10: 1043-1058. [CrossRef]

- Moreau, Anne-Marie et al. “Oral Health Status of Refugee Children in Montreal.” Journal of immigrant and minority health 2019, vol. 21,4: 693-698. [CrossRef]

- Lavanchy D, Kane M. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection. In Hepatitis B virus in human diseases 2016 (pp. 187-203). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Xiao, W., Zhao, J., Chen, Y., Liu, X., Xu, C., Zhang, J., Qian, Y., & Xia, Q. Global burden and trends of acute viral hepatitis among children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Hepatology International, 2024, 18(3), 917–928. [CrossRef]

- Baauw, A., Kist-van Holthe, J., Slattery, B., Heymans, M., Chinapaw, M., & Van Goudoever, H. Health needs of refugee children identified on arrival in reception countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 2019b, 3(1), e000516. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, K.L.H, Sprechmann, P., Calderbank, R., Sapiro G, Egger H. L. Quantifying Risk for Anxiety Disorders in Preschool Children: A Machine Learning Approach. PLOS ONE 2016, 11(11): e0165524. [CrossRef]

- Wichstrøm L, Belsky J, Berg-Nielsen TS. Preschool predictors of childhood anxiety disorders: a prospective community study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013, 54(12):1327-1336. [CrossRef]

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Evidence snapshots [Internet]. Toronto (ON): CAMH. Available from: https://www.camh.ca/en/professionals/professionals--projects/immigrant-and-refugee-mental-health-project/newsletter/evidence-snapshots. (accessed 2024 Jun 22).

- Pottie, K., Greenaway, C., Feightner, J., Welch, V., Swinkels, H., Rashid, M., Narasiah, L., Kirmayer, L. J., Ueffing, E., MacDonald, N. E., Hassan, G., McNally, M., Khan, K., Buhrmann, R., Dunn, S., Dominic, A., McCarthy, A. E., Gagnon, A. J., Rousseau, C., … Health, coauthors of the C. C. for I. and R. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ, 2011, 183(12), E824–E925. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Ontario. (n.d.). Parasite – Faeces. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/laboratory-services/test-information-index/parasite-faeces. (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Alberta Precision Laboratories. (n.d.). Ova and parasite exam (O&P). https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/webapps/labservices/indexAPL.asp?id=8538&tests=&zoneid=1&details=true. (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Herrick JA, Nordstrom M, Maloney P, Rodriguez M, Naceanceno K, Gallo G, Mejia R, Hershow R. Parasitic infections represent a significant health threat among recent immigrants in Chicago. Parasitology research. 2020, Mar;119(3):1139-48.

- International Society for Clinical Densitometry. 2019 ISCD official positions – Pediatric. 2019. https://www.iscd.org.

- Bernhardt, K., Le Beherec, S., Uppendahl, J., Baur, M.-A., Klosinski, M., Mall, V., & Hahnefeld, A. Exploring Mental Health and Development in Refugee Children Through Systematic Play Assessment. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 2025, 56(3), 629–639. [CrossRef]

- Sterling, T. R., Bethel, J., Goldberg, S., Weinfurter, P., Yun, L., & Horsburgh, C. R. The Scope and Impact of Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection in the United States and Canada. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2006, 173(8), 927–931. [CrossRef]

- King, J. S. H., Low, P. S., Chan, Y. H., & Neihart, M. Interpreting Parents’ Concerns About Their Children’s Development with the Parents Evaluation of Developmental Status: Culture Matters. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 2012, 33(2), 179. [CrossRef]

- Kroening, A. L. H., Moore, J. A., Welch, T. R., Halterman, J. S., & Hyman, S. L. Developmental Screening of Refugees: A Qualitative Study. Pediatrics, 2016, 138(3), e20160234. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., Jiao, D., Li, X., Zhu, Y., Kim, C., Ajmal, A., Matsumoto, M., Tanaka, E., Tomisaki, E., Watanabe, T., Sawada, Y., & Anme, T. Measurement invariance and country difference in children’s social skills development: Evidence from Japanese and Chinese samples. Current Psychology, 2023, 42(24), 20385–20396. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie K, Ashraf A, Tuck A, di Tomasso L, Thompson L, Varga B. (2019). Immigrant, refugee, ethnocultural and racialized populations and the social determinants of health: A review of 2016 census data. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Available from: https://www.camh.ca/en/professionals/professionals--projects/immigrant-and-refugee-mental-health-project/newsletter/evidence-snapshots/es-nov-2019---immigrant-refugee-ethnocultural-and-racialized-populations. (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- de Freitas Girardi, J., Miconi, D., Lyke, C., & Rousseau, C. Creative expression workshops as Psychological First Aid (PFA) for asylum-seeking children: An exploratory study in temporary shelters in Montreal. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2020, 25(2), 483–493. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J. T., & Kennedy, S. Insights into the ‘healthy immigrant effect’: Health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 2004, 59(8), 1613–1627. [CrossRef]

- Morteza H, Boleyn T. Health ecology: health, culture and human-environment interactions. Routledge London, New York. 1999.

- von Schirnding, Y. Health ecology. Health, culture and human-environment interaction. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2000, 78(2), 276–276.

- Berman H, Mulcahy G, Forchuk C, et al. Uprooted and displaced: a critical narrative study of homeless, Aboriginal, and newcomer girls in Canada. Issues Ment. Health Nurs 2009, 30:418–430. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2018, 169(7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Inclusion (study meets all criteria) | Exclusion (study meets any criteria) |

| Population | Focus on refugees, asylum seekers, or displaced persons | Immigrants, Adolescents, youth and adults, Newcomers |

| Age | A sample of refugee children birth to 5 years old in the population | Adolescents, youth and adults |

| AND | ||

| Setting (Context) | Refugee-receiving Primary healthcare clinic/centre providing services to refugee/immigrant | |

| AND | ||

| Phenomena of Interest (Concept) | Health conditions or outcomes of young children and/or health conditions or outcomes measurement techniques and tools | Focus on acute/emergency health issues |

| Study design/ types of publication | Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods studies, Interventional studies/ RCTs, Review articles, Secondary data analysis, Grey literature, Conference proceedings, preprints, and research letter | Opinion papers or commentaries or pieces, Books, presentations, and conference abstracts, case studies |

| Results of studies | Results presented for Canadian children < 6 years. Health outcomes must be disaggregated for this population but not health measurements | |

| AND | ||

| Country | Canada | Any study does not include Canada |

| Language | English language | Published in any language other than English |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).