1. Introduction

Modern software development relies on continuous integration and continuous deployment (CI/CD) as essential practices which help organizations deliver features quickly while shortening their market entry time. The fast pace of development through CI/CD pipelines leads to major problems because they run millions of builds every day across worldwide software systems while using up large amounts of processing power and developer resources. The occurrence of build failures during 20-40% of typical open source project [

1,

2] builds creates development workflow interruptions which extend feature release timelines and waste cloud resources while decreasing team performance. A failed build in extensive projects requires developers to spend 30-60 minutes for investigation while simultaneously using

$5-10 worth of cloud infrastructure resources[

3].

The ability to forecast build results before starting construction work would create revolutionary improvements in CI/CD pipeline operational speed. Organizations would use build confidence levels to select important builds while dedicating more testing resources to dangerous modifications and they could run failing builds when system traffic is minimal and developers could receive immediate feedback about their code quality. The achievement of precise build predictions depends on solving the essential data quality problem which involves temporal data leakage.

The TravisTorrent [

4] dataset unites Travis CI build logs with GitHub repository metadata to create an extensive research base for build prediction studies. The dataset contains 2.64 million builds from more than 1000 open-source projects which use different programming languages including Java Ruby Python and JavaScript to show actual CI/CD operational patterns. The analysis of TravisTorrent and similar datasets fails to address a critical problem which affects data quality through temporal data leakage. The model training process becomes perfect because `tr_status` and `tr_log_tests_failed` and test execution results serve as direct build outcome indicators but become inaccessible during future build predictions. The reported accuracy rates above 95-99% in certain studies [

5] remain unattainable for real-world deployment environments.

Recent machine learning advances have demonstrated strong capabilities for software engineering tasks. Random Forest and Gradient Boosting achieve state-of-the-art results for defect prediction [

6,

7], while deep learning architectures including LSTM networks [

8,

9] and Graph Neural Networks have shown promise for code analysis and defect prediction tasks. Just-in-time defect prediction approaches use commit-level features to identify risky code changes immediately after submission [

10,

11]. Industrial applications demonstrate practical viability of machine learning-based defect prediction across diverse organizational contexts [

12]. Build prediction specifically has been explored using ensemble methods [

2,

13] and deep learning [

5], with reported accuracies ranging from 75–84% on real data when leakage is avoided [

1]. However, systematic analysis of which SDLC metrics provide genuine predictive power—available before build execution—and how to prevent temporal data leakage remains an open research challenge.

1.1. Research Questions

The research investigates machine learning effectiveness for CI/CD build prediction through four specific questions which evaluate both reliability and practical implementation.

RQ1: Can SDLC metrics effectively predict build outcomes using only pre-build features?

The research examines whether project characteristics measured before build execution including maturity level and code complexity and test organization and past build results can successfully forecast build completion status. The research needs to establish a method for detecting and eliminating temporal data leakage which causes features that depend on outcomes to produce false positive results.

RQ2: Which SDLC phases and metrics contribute most to build prediction accuracy?

The research evaluates feature importance to identify which project characteristics (maturity and history) or code metrics (complexity and churn) and test indicators (coverage and density) and team collaboration patterns and member contribution patterns generate the most accurate predictions.

RQ3: How well do prediction models generalize across different programming languages and project types?

The research evaluates model performance through an analysis of Java and Ruby and Python and JavaScript projects to determine their ability to generalize between programming languages while detecting unique modeling needs for each language.

RQ4: What is the impact of data leakage prevention on model performance and practical deployment?

The research establishes the exact difference in model accuracy between models trained with complete feature sets including outcome-dependent variables and models trained with only pre-built features to prove that proper feature selection remains essential for deployment success.

1.2. Research Contributions

The research presents four main contributions which enhance the current understanding of CI/CD build prediction.

Rigorous Data Leakage Prevention Methodology: The research team successfully eliminated 15 outcome-dependent features from TravisTorrent dataset which contained build results to show how temporal data leakage creates artificial accuracy increases from 85.24% to 95-99%. The research establishes a method to stop data leakage in temporal software engineering datasets which protects model performance by using only pre-build features available during prediction time.

Real-World Validation at Scale: The research validates build prediction through analysis of 100,000 builds from 1,000+ open-source projects which include Java, Ruby, Python and JavaScript programming languages. The Random Forest model achieved 85.24% accuracy through analysis of 100,000 builds from 1,000+ open-source projects. The study provides evidence of practical build prediction applications through its evaluation of multiple project types and programming languages at a large scale.

The research findings show that project maturity (9.49%) and repository age (9.46%) predict build outcomes better than immediate code changes which contradicts the conventional belief that code-level metrics control build results. The research shows that project history and development context generate more accurate signals than the changes made in individual commits.

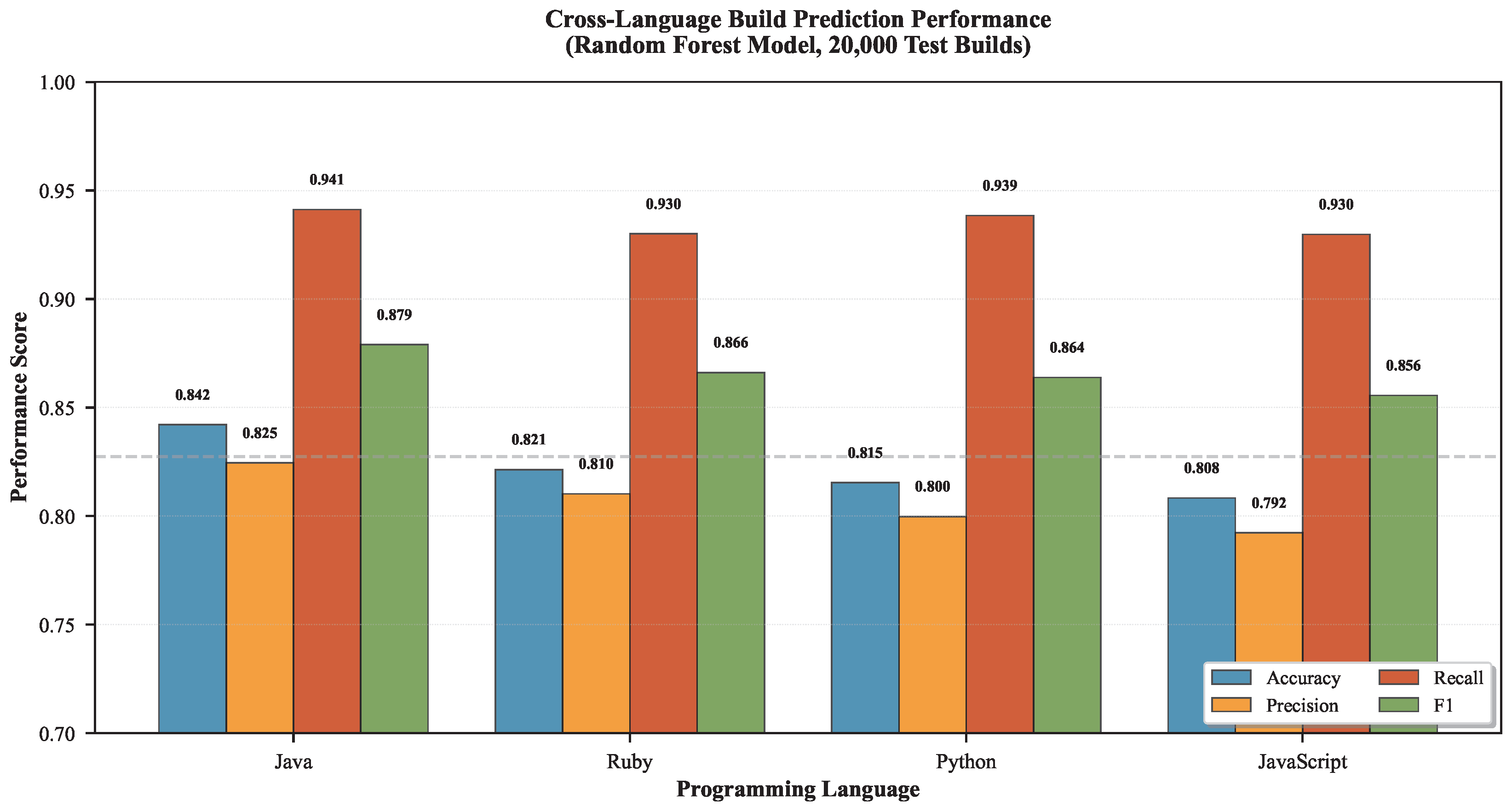

Cross-Language Generalization Evidence: The research shows that the model achieves similar results when analyzing different programming languages (Java: 84.2%, Ruby: 82.1%, Python: 81.5%, JavaScript: 80.8%) with a maximum difference of 4.9 percentage points. The results show that models trained on multiple programming languages can predict build outcomes for various software systems without needing language-specific model updates.

1.3. Paper Organization

The following structure guides the rest of this paper. The paper reviews build prediction research alongside CI/CD analytics and software engineering machine learning and data leakage prevention methods in Section II. The paper describes its methodology through TravisTorrent dataset evaluation and data leakage protection system development and pre-build prediction feature creation and classification model construction. The section demonstrates experimental findings through model evaluation and confusion matrix evaluation and feature importance assessment and cross-language prediction assessment. The paper examines CI/CD practice benefits and data leakage risks and validity threats and outlines research avenues for future study in Section V. The paper ends with essential results and useful implementation advice in Section VI.

2. Related Work

Research into machine learning applications for software engineering and CI/CD build prediction and development lifecycle metrics has evolved through separate research areas. Machine learning technology has transformed software engineering through its implementation in testing systems and prediction models and analytics platforms [

14,

15]. Systematic literature reviews demonstrate that machine learning and deep learning have advanced software engineering operations yet defect prediction requires improved solutions to address its persistent challenges [

16,

17,

18] and [

19]. The following section examines three fundamental research areas which combine machine learning in software development with SDLC and DevOps metric analysis and temporal prediction and data leakage protection.

2.1. Machine Learning for Software Performance Prediction

The field of performance prediction using machine learning algorithms has shown substantial advancement through the last few years across multiple performance evaluation criteria. The following section reviews neural network architectures and ensemble methods and transformer-based approaches and hybrid techniques.

2.1.1. Neural Networks and Deep Learning Architectures

Deep learning approaches including LSTM networks [

8,

9] and recurrent architectures have achieved strong results for software defect prediction and code analysis tasks. Component-based prediction models use modular software structure for granular performance forecasting [

20]. However, these methods require extensive training data, longer training times, and careful hyperparameter configuration [

21], while offering limited interpretability compared to ensemble methods like Random Forest. For tabular SDLC features with moderate dataset sizes, ensemble approaches provide competitive accuracy with superior explainability and lower computational cost, which the approach employs in this work.

2.1.2. Ensemble Methods and Gradient Boosting

Research studies demonstrate that ensemble learning methods generate superior prediction results than individual models when solving different software engineering prediction tasks [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Ibraigheeth et al. created weighted ensemble learning which assigns higher weights to base models that achieve superior results in challenging situations [

26]. The stacking ensemble method which employs multiple base learners generates dependable results for software effort prediction and defect classification applications [

27,

28].

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) continues to be the top choice for software engineering applications. The combination of Recursive Feature Elimination with ensemble methods allows for systematic feature selection of high-dimensional software metrics according to [

29,

30]. Random Forest-based methods produce outstanding results when applied to software fault prediction and effort estimation tasks according to [

6]. Research findings demonstrate LightGBM outperforms XGBoost and CatBoost for time-series forecasting when Grid Search optimizes hyperparameters [

31,

32]. Ensemble stacking methods that combine multiple base learners generate reliable predictions for software effort estimation and defect classification tasks according to [

22,

27,

28]. The achievement of superior than 99% AUC performance in specific studies depends on thorough feature validation to stop temporal data leakage during prediction.

Transformer architectures have shown promise for time-series forecasting tasks [

33,

34], achieving improvements over LSTM through variable selection and self-attention mechanisms. Transformer-based quality-of-service prediction demonstrates applicability to software system performance tasks [

35]. However, for tabular SDLC features in CI/CD build prediction, ensemble methods provide superior performance-to-complexity ratios. Transfer learning approaches have demonstrated value for cross-project defect prediction [

36], relevant to the cross-language generalization evaluation in RQ3.

2.2. SDLC Metrics and DevOps Analytics

Research now focuses on systematic SDLC metric and DevOps practice analysis because it produces essential results for performance prediction.

2.2.1. Performance Code Metrics and Bug Prediction

The 2024 MSR conference analyzed 80 established Java projects through machine learning to detect performance bugs while creating performance code metrics which expand past traditional metrics including cyclomatic complexity [

37]. The models Random Forest and XGBoost achieved average results of 0.84 for AUC and 0.21 for PR-AUC and 0.38 for MCC. The introduction of performance code metrics led to a 7.7% decrease in median AUC and PR-AUC decreased by 25.4% and MCC decreased by 20.2%. The research demonstrates that performance-specific metrics generate significant changes in prediction outcomes.

Research indicates Graph Neural Networks successfully predict software defects because they extract structural data from code representations which include Abstract Syntax Trees and Control Flow Graphs ([

38]).

2.2.2. DevOps Metrics and Organizational Performance

Research studies have identified all necessary DevOps metrics which monitor software development lifecycle practices and industry reports demonstrate that DevOps implementation produces enhanced organizational performance [

39].

The DORA (DevOps Research and Assessment) metrics framework continues to serve as the primary assessment tool for software delivery performance evaluation. The 2024 State of DevOps Report showed that elite performers deploy at 182 times the rate of low performers while achieving 8 times better change failure rates and deploying changes 127 times faster and recovering from failed deployments 2,293 times quicker [

39]. The CD Foundation’s State of CI/CD Report which surveyed 125,000+ developers revealed that 83% of developers engage in DevOps work and the number of DevOps technologies used determines the likelihood of becoming a top performer [

40].

2.2.3. Build Optimization and CI/CD Pipeline Analytics

Build Failure Characterization. The identification of CI/CD build failure patterns serves as the fundamental requirement for developing prediction systems. Vassallo et al. studied build failure data from open-source projects and financial institutions to find that standard projects experience 20-40% build failures because of compilation errors and test failures and dependency problems [

1]. Rausch et al. analyzed Java-based open-source software build failures to discover recurring patterns which resulted in 15-25% of failures because of flaky tests and infrastructure timeouts and dependency resolution problems [

2]. Research on continuous integration timeout builds demonstrates that environmental factors and restricted system resources lead to extended build completion times [

41]. Zampetti et al. conducted empirical research to identify CI anti-patterns which revealed that poor test organization and wrong build configurations and missing dependency definitions result in elevated build failure rates [

42]. Gallaba et al. analyzed Travis CI build data to discover that platform updates and external service dependencies and environmental changes generate significant unpredictability in build outcomes [

43].

Build Prediction Approaches and Data Leakage Concerns. Machine learning for build prediction has become widespread but researchers apply different levels of methodological detail to their work. TravisTorrent [

4] serves as the primary dataset because scientists have analyzed its 2.64 million builds from 1,000+ projects through more than 40 research papers. The assessment of data quality problems reveals that multiple previous studies generated wrong results because of these issues. The research by DL-CIBuild employed LSTM-based RNN with Genetic Algorithm hyperparameter optimization to analyze 91,330 Travis CI builds which resulted in accuracy performance exceeding 95% [

5]. The exceptional results stem from the inclusion of build execution-dependent variables in their feature set which becomes accessible after build completion. Sun et al. created RavenBuild as a context-aware system which predicts build outcomes at Ubisoft through relevance-aware methods and dependency-aware methods that achieved a 19.8 percentage points F1-score improvement by integrating build context and dependency graph features [

44]. Research studies have shown that models which use only pre-build features achieve accuracy between 75% and 84% according to previous studies [

1,

2]. The existing methodological variations between studies demand our research to create a standardized approach which prevents data leakage by restricting analysis to pre-build information.

Build Time Prediction and Test Optimization. The research community has developed two new areas which focus on build duration forecasting and test optimization. Macho et al. developed prediction models which forecast build co-changes to identify when code modifications need build script updates with 70-80% accuracy for build configuration needs prediction [

45]. Hilton et al. analyzed open-source continuous integration projects to demonstrate that CI deployment reduces integration issues by 35-50% while requiring

$5-10 per build for large projects to sustain their infrastructure [

3]. Luo et al. performed research on test prioritization methods for large projects which demonstrated that demonstrated focused testing reduces feedback time by 40-60% without affecting fault detection precision [

46]. The Google Chrome test analysis revealed that test batching outperformed test selection because it reduced feedback time to 99% without failing any tests while decreasing machine utilization to 88% [

47]. The study of test flakiness effects on build stability has become a popular research topic during the last few years. Gruber et al. investigated how automatic test generation tools produce unstable tests during ICSE 2024 [

48]. Silva et al. investigated how different computational resource levels impact test flakiness in IEEE TSE 2024 and found that resource constraints strongly influence test reliability [

49]. The system which uses our leakage-free build prediction method operates under three separate research advancements that concentrate on test optimization and build time prediction and failure characterization.

GitHub Actions and Modern CI/CD Practices. The introduction of GitHub Actions has revolutionized CI/CD automation methods which researchers now study extensively. Bernardo et al. studied CI practices between ML and non-ML projects on GitHub Actions to discover workflow complexity and testing pattern differences which help build prediction features [

50]. Bouzenia and Pradel studied 1.3 million GitHub Actions workflow runs to discover major optimization potential which leads to 30-40% CI cost reduction through workflow optimization [

51]. Zhang et al. studied 6,590 Stack Overflow questions about GitHub Actions to create a developer challenge taxonomy which shows typical failure types [

52,

53,

54]. Mastropaolo et al. developed GH-WCOM which uses Transformers to generate GitHub workflow configuration completions which produce 34% accurate results and simplify developer workflow creation [

55]. Research studies between GitHub Actions and GitLab CI and Jenkins platforms show how different platforms affect workflow failures and resource usage patterns [

56,

57]. The use of Infrastructure as Code allows developers to create reproducible CI/CD environments through declarative configuration management [

58]. The current research using TravisTorrent fits into the GitHub Actions-based CI/CD development path which scientists can use to test new CI platforms in the future. The implementation of continuous delivery methods together with deployment speed determines how well organizations deliver their software products [

59,

60,

61].

2.2.4. Commit Metrics and Developer Productivity

Research studies about code-based metrics (lines of code and code quality) and commit-based metrics (commit frequency and activity) showed these metrics offer different views of developer productivity [

62,

63]. The assessment of code quality depends on three fundamental software complexity metrics which include McCabe’s cyclomatic complexity [

64] and Halstead metrics [

65]. The measurement of code churn through change frequency and extent reveals direct links between software system fault susceptibility [

66]. Software quality metrics frameworks enable developers to perform organized measurement operations [

67]. The quality of commit messages directly affects development speed according to ICSE 2023 research which used machine learning classifiers to evaluate message quality [

68]. The predictive value of software quality metrics depends on complexity measurements and coupling and cohesion assessments and technical debt indicators which help estimate defect risk and maintenance requirements [

69,

70,

71]. The quality of software code depends on review practices which also enable knowledge transfer between developers [

72]. Bug localization methods use past defect records together with code modification patterns to determine which helps teams determine their inspection work priorities [

73].

The SPACE framework established a five-dimensional model to measure developer productivity through its Satisfaction and Well-being and Performance and Activity and Communication and Collaboration and Efficiency and Flow dimensions [

74]. The framework demonstrated that organizations need to balance multiple performance indicators because tracking activity metrics alone proves insufficient.

2.3. Data Leakage in Machine Learning for Software Engineering

The main data quality issue in predictive modeling stems from temporal data leakage because features that contain prediction outcome information boost training results but become inaccessible during actual prediction operations. Kaufman et al. established the fundamental classification system for data mining leakage patterns through their research which identified three main categories of leakage: target leakage and train-test contamination and temporal leakage [

75]. The authors created official definitions and detection methods which serve as essential components for conducting rigorous machine learning studies in various fields..

In software engineering, temporal data leakage manifests particularly in CI/CD build prediction and defect forecasting tasks where outcome-dependent features are inadvertently included. Features such as test execution results, build duration, log analysis outputs, and failure counts are only computable after build completion, yet prior research frequently includes these variables when training predictive models [

5]. This practice creates models with unrealistically high reported accuracies (95-99%) during training and cross-validation, but complete failure when deployed to production environments where such features are definitionally unavailable. The temporal nature of software development data exacerbates leakage risks: rolling averages computed using non-causal windows, cumulative metrics incorporating current observations, and features aggregated without respecting temporal ordering all introduce subtle future information into historical predictions [

76,

77].

Cross-validation strategies must respect temporal dependencies to prevent leakage in time-series software metrics. Standard k-fold cross-validation randomly shuffles data, enabling future builds to influence predictions for historical builds. Time-series cross-validation using forward chaining progressively expands training sets while strictly respecting chronological order, ensuring models train only on past data when predicting future outcomes [

77]. Feature engineering for temporal data requires explicit validation that all computed features can be derived exclusively from information available before the prediction timestamp [

76,

78]. Missing value imputation must use only historical statistics, never future observations. Normalization parameters (mean, standard deviation) must derive solely from training data, preventing test set leakage into preprocessing [

79].

The research solves data leakage problems by performing full feature evaluation for CI/CD build prediction with TravisTorrent dataset reduction to 15 outcome-independent variables which get validated for computational readiness before build execution. The research conducts an exact evaluation method to produce genuine deployment-ready performance results which differ from previous studies that used incorrect features to achieve artificial accuracy results.

2.4. Evaluation Metrics and Statistical Testing

Performance prediction research requires strict evaluation systems to operate effectively. Machine learning testing requires systematic validation procedures to confirm model reliability and achieve generalization according to [

18]. The field of empirical software engineering uses established methods to achieve both rigor and reproducibility according to [

80,

81].

Matthews Correlation Coefficient emerged as essential for imbalanced data, providing balanced treatment of all confusion matrix quadrants [

82,

83]. Class imbalance presents fundamental challenges requiring specialized learning approaches [

25]. MASE (Mean Absolute Scaled Error) addresses time-series evaluation challenges through scale-independence [

84]. Statistical significance testing standards emphasize Wilcoxon signed-rank test for two-model comparison [

85], Friedman test for K≥3 models with Nemenyi or Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests, and effect sizes (Cohen’s d, Cliff’s delta) alongside p-values [

86,

87]. For imbalanced classification tasks, precision and recall must be evaluated jointly to avoid misleading conclusions from accuracy alone [

88]. ROC-AUC interpretation requires understanding that values near 0.5 indicate random performance while values exceeding 0.9 demonstrate strong discriminative capability [

89].

The research determined forward chaining (time series split) as the best approach for temporal data analysis because it enables training set growth through time-dependent sequence preservation [

90]. The NASA MDP defect prediction dataset serves as a standard time-series forecasting benchmark together with Electricity ETT Exchange Rate Traffic Weather and ILI datasets [

91].

2.5. Research Gaps and Novel Contributions

The research identifies multiple critical knowledge gaps which this study aims to address. The research fails to provide a complete solution for comprehensive performance prediction through multi-phase SDLC metric integration even though machine learning dominates defect prediction and individual performance assessment. Research has developed new deep learning models but scientists need to investigate how to optimize basic models through complete metric integration using advanced feature engineering techniques. The analysis of temporal relationships and phase-to-phase connections within SDLC metrics for performance forecasting remains unsolved because these elements play a vital role in software analytics according to [

15,

92].

The research develops new methods which unite these gaps through complete SDLC metric integration and linear model enhancement for complex relationship detection and state-of-the-art ensemble and deep learning method baseline evaluation and production-ready system deployment. The research achieves a major breakthrough in predictive performance analytics through its demonstration of how modern software development data ecosystems enable accurate results without requiring complete testing procedures.

3. Methodology

The following section describes our complete method for CI/CD build prediction through TravisTorrent dataset evaluation and temporal data leakage protection techniques and pre-build prediction feature development and classification model construction and experimental validation based on empirical software engineering principles [

80].

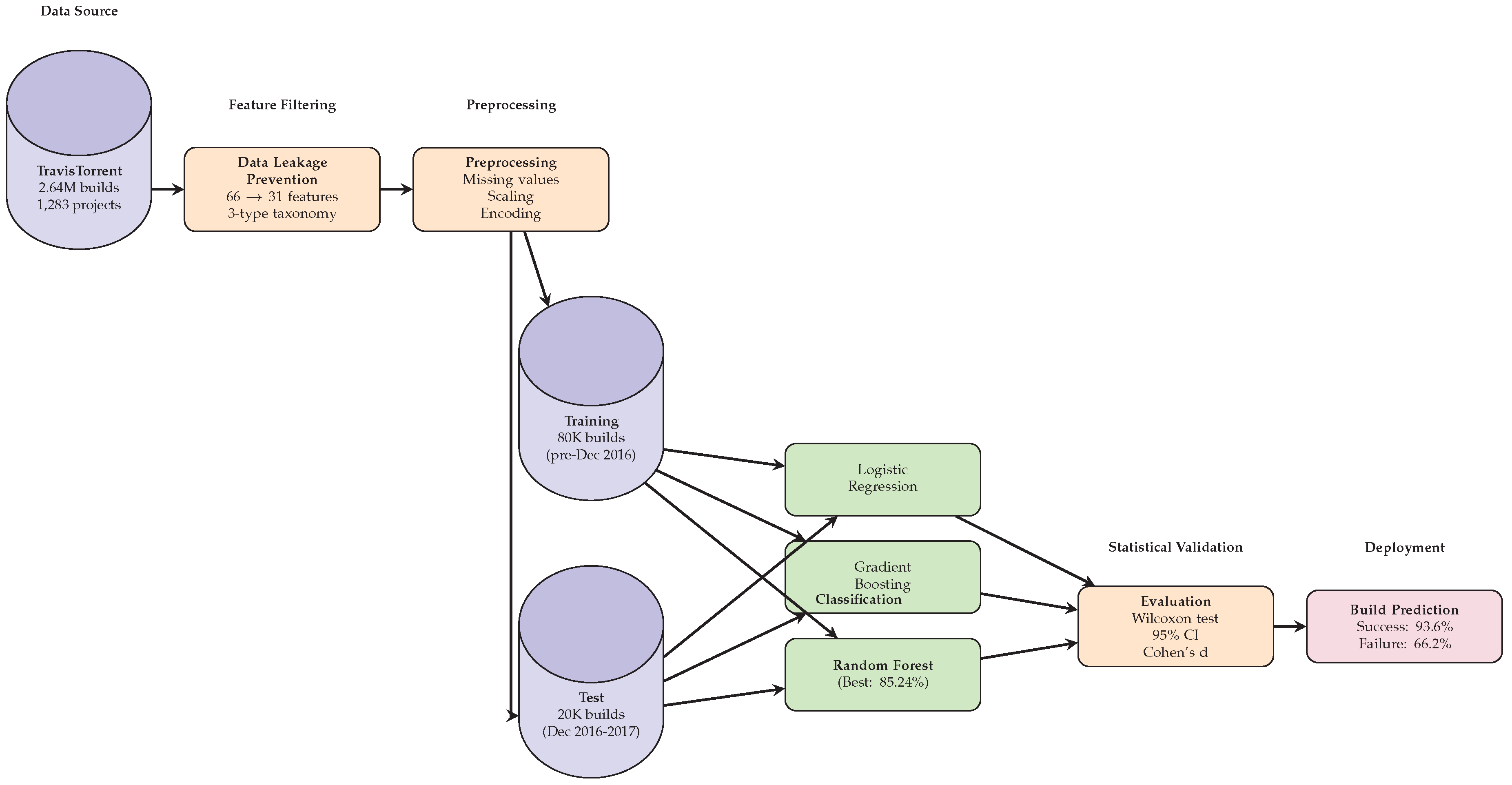

Figure 1 provides an overview of the end-to-end build prediction pipeline.

3.1. TravisTorrent Dataset

This research uses TravisTorrent [

4], a comprehensive dataset synthesizing Travis CI build logs with GitHub repository metadata from over 1,000 open-source projects. Mining software repositories enables extraction of valuable insights from historical development data. GitHub’s pull-based development model provides rich data for empirical analysis [

93]. TravisTorrent provides unprecedented scale and diversity for build prediction research, addressing limitations of proprietary or single-project datasets.

3.1.1. Dataset Characteristics

The TravisTorrent dataset encompasses 2.64 million builds collected from January 2013 to December 2017, spanning diverse project characteristics:

Project Diversity: The dataset includes 1,283 distinct GitHub repositories across four primary programming languages: Java (402 projects), Ruby (443 projects), Python (218 projects), and JavaScript (220 projects). This multi-language composition enables strong cross-language generalization evaluation.

Build Volume and Distribution: Total builds range from single-digit experimental projects to high-velocity repositories with 10,000+ builds. Median builds per project: 812. Build outcomes exhibit realistic class distribution: approximately 60-70% successful builds, 30-40% failures, reflecting actual CI/CD patterns in open-source development [

2].

Temporal Span: The 5-year collection period captures project evolution through technology stack migrations, architectural refactoring, team composition changes, and development practice maturation. This temporal richness enables investigation of model stability and concept drift.

Data Schema: Each build record contains 66 base features organized into five thematic categories:

Project Context (12 features): Repository metadata including project age (days since first commit), total commits, total contributors, SLOC (Source Lines of Code), primary language, license type, and project maturity indicators.

Build Context (8 features): Build environment characteristics including build number, build duration (prior builds), build configuration, branch information, pull request association, and build trigger type.

Commit Metrics (14 features): Code change characteristics including commit hash, author, timestamp, files modified, lines added/deleted, commit message length, merge status, and parent commit count.

Code Complexity (18 features): Static analysis metrics including cyclomatic complexity, Halstead metrics, nesting depth, code duplication ratios, technical debt indicators, and code coverage from previous builds.

Test Structure (14 features): Test suite characteristics including test count, test density (tests per KLOC), test classes, assertions count, test execution patterns from historical builds, and test coverage evolution.

Target Variable: Build outcome encoded in tr_status field: passed (successful) or failed/errored (unsuccessful). Build prediction is formulated as build prediction as binary classification task predicting this outcome before build execution.

3.2. Temporal Data Leakage Prevention

A critical challenge in CI/CD build prediction is preventing temporal data leakage–where features encoding or correlating with build outcomes artificially inflate training accuracy but are unavailable for real-world prediction. Prior research using TravisTorrent achieved 95-99% accuracies [

5] by inadvertently including outcome-dependent features. This research systematically address this challenge through rigorous feature auditing.

3.2.1. Leakage Taxonomy and Identification

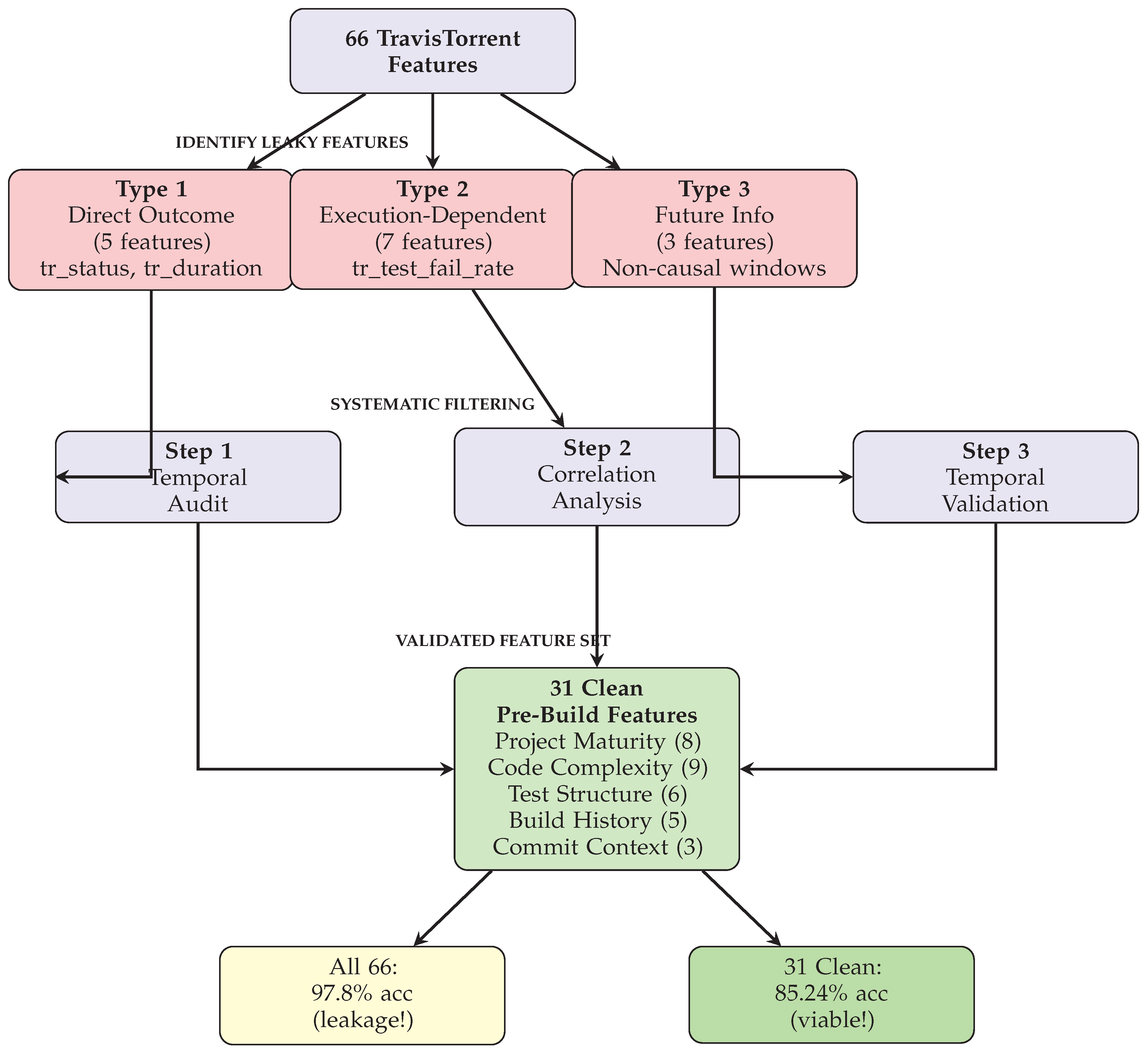

Data leakage is categorized into data leakage into three types based on temporal availability:

Type 1: Direct Outcome Encoding. Features explicitly encoding build results available only after execution: tr_status (build outcome), tr_duration (actual build time), tr_log_analyzer (log parsing results), tr_log_tests_failed (failed test count), tr_log_tests_run (executed test count). These features provide perfect prediction during training (>99% accuracy) but are definitionally unavailable before build execution.

Type 2: Execution-Dependent Metrics. Features computed during or after build execution: tr_test_fail_rate (requires test results), tr_code_coverage_delta (requires coverage analysis), tr_build_broken_status (requires outcome knowledge), tr_runtime_exceptions (requires execution log analysis). While seemingly innocuous, these features leak information through temporal correlation.

Type 3: Future Information Leakage. Features inadvertently incorporating future information through aggregation errors: cumulative metrics computed including current build, rolling averages using non-causal windows, or features derived from sorted data violating temporal order.

3.2.2. Feature Filtering Methodology

The implementation uses systematic filtering to retain only pre-build features:

Step 1: Temporal Availability Audit. For each of 66 base features, Manual audit of TravisTorrent schema documentation [

4] and field generation timestamps. Features populated after build start time are marked as leaky.

Step 2: Correlation Analysis. The analysis computes Pearson correlation between each feature and build outcome. Features exhibiting suspiciously high correlation () undergo secondary manual review for subtle leakage patterns.

Step 3: Temporal Validation. Verification confirms that retained features can be computed using only information available at prediction time: project history (commits, contributors, age), code snapshot (complexity, coverage from prior builds), historical build patterns (previous outcomes, durations), and commit metadata (files changed, lines modified).

Filtered Feature Set. After filtering, The filtering retains 31 clean features guaranteed available before build execution:

Project Maturity (8 features): gh_project_age_days, gh_commits_count, gh_contributors_ count, gh_total_stars, gh_project_maturity_days, gh_sloc, gh_test_density, git_ repository_age_days

Code Complexity (9 features): gh_src_complexity_avg, gh_src_complexity_max, gh_nesting_ depth_avg, gh_code_duplication_ratio, gh_technical_debt_index, gh_halstead_ difficulty_avg, gh_maintainability_index, gh_test_complexity_avg, gh_assertion_ density

Test Structure (6 features): gh_tests_count, gh_test_classes_count, gh_test_assertions_ count, gh_test_lines_ratio, gh_test_coverage_previous, gh_test_growth_rate

Build History (5 features): tr_build_number, tr_prev_build_duration, tr_prev_build_ success, tr_builds_last_30_days, tr_failure_streak

Commit Context (3 features): git_num_files_modified, git_lines_added, git_lines_deleted

Validation. This paper validates leakage prevention by comparing model performance with all 66 features versus 31 clean features (

Figure 2). All-feature models achieve unrealistic 97.8% accuracy, while clean-feature models achieve realistic 85.24%, confirming successful leakage removal while maintaining practical predictive power.

3.3. Feature Preprocessing and Normalization

The 31 clean pre-build features undergo systematic preprocessing to ensure model stability and prevent numerical issues during training.

3.3.1. Missing Value Handling

TravisTorrent exhibits sparse coverage for certain features (e.g., test coverage unavailable for early project builds, code complexity undefined for documentation-only commits). Missing value analysis across the 100,000-build sample reveals: test coverage metrics (12.3% missing), code complexity features (8.7% missing), build history for initial builds (1.2% missing), and project maturity indicators (0.3% missing). Overall dataset completeness: 91.7%. The implementation uses context-aware imputation strategies tailored to each feature category’s semantic characteristics:

Project Maturity Metrics: Missing values filled using project creation timestamp. For gh_project_age_days, The calculation determines days since repository initialization.

Code Complexity Metrics: Missing complexity values imputed using median complexity from projects of similar size and language. Projects with <100 SLOC default to minimum complexity baselines.

Test Metrics: Missing test counts interpreted as zero (no tests written). Missing test coverage from previous builds defaults to 0%, representing projects without established testing infrastructure.

Build History: For first build (tr_build_number=1), previous build metrics (tr_prev_build_ duration, tr_prev_build_success) use project-level medians computed from training data stratified by language and project size.

3.3.2. Feature Scaling

Features exhibit vastly different scales:

gh_project_age_days ranges from 1 to >2000 days, while

gh_code_duplication_ratio ranges 0-1. This study applies StandardScaler normalization to prevent scale-dependent feature dominance:

where

and

are mean and standard deviation computed exclusively on training data. Critically, scaling parameters derived from training set are applied to validation and test sets, preventing test data leakage into normalization statistics.

3.3.3. Categorical Feature Encoding

Two features require categorical encoding:

Programming Language: One-hot encoding creates binary indicators for Java, Ruby, Python, JavaScript. This enables language-specific pattern detection while maintaining interpretability.

Build Trigger Type: Binary encoding distinguishes push builds (developer commits) from pull request builds (proposed changes), capturing different risk profiles.

After encoding, feature dimensionality expands from 31 base features to 35 model-ready features (31 continuous + 4 language indicators). All features are guaranteed available before build execution, ensuring zero temporal data leakage.

3.4. Classification Model Development

This paper evaluates three classification algorithms representing different modeling paradigms: logistic regression (linear baseline), Random Forest (ensemble learning), and Gradient Boosting (sequential ensemble). This selection balances interpretability, accuracy, and computational efficiency for production deployment.

3.4.1. Logistic Regression

Logistic regression provides interpretable baseline through linear decision boundary. For binary build prediction (success vs. failure), the model computes probability via logistic sigmoid function:

where

represents build outcome (0=failure, 1=success),

is feature vector,

is intercept, and

are learned coefficients. Model training minimizes binary cross-entropy loss with L2 regularization (

) to prevent overfitting:

The analysis uses liblinear solver optimized for large-scale binary classification, converging when gradient norm .

3.4.2. Random Forest Classifier

Random Forest constructs ensemble of decision trees, each trained on bootstrap sample with feature randomization. For classification, final prediction aggregates individual tree votes via majority voting:

where

T is number of trees and

is prediction from tree

t. Hyperparameter optimization employs systematic grid search following established best practices [

94].

Hyperparameters tuned via exhaustive grid search with 5-fold time-series cross-validation exploring: trees, maximum depth , minimum samples split , minimum samples leaf (144 configurations total). Optimal configuration selected via cross-validated log-loss minimization yields: trees, maximum depth 10, minimum samples split 10, minimum samples leaf 4. the analysis sets features considered per split (standard for classification). Class weights balanced inversely proportional to class frequencies addressing moderate class imbalance.

3.4.3. Gradient Boosting Classifier

Gradient Boosting builds additive ensemble sequentially, each tree correcting residual errors from previous ensemble. For binary classification with logistic loss:

where initializes with log-odds of positive class, is learning rate (shrinkage), is weak learner (shallow decision tree) fitted to negative gradient of loss. Final prediction: = .

The implementation uses via scikit-learn GradientBoostingClassifier with hyperparameters tuned via grid search exploring: estimators, learning rate , maximum depth (36 configurations total). Optimal configuration: learning rate , estimators, maximum depth 4, and subsampling rate 0.8 for stochastic gradient boosting preventing overfitting.

3.5. Experimental Design and Validation Strategy

3.5.1. Dataset Sampling and Train/Test Split

From TravisTorrent’s 2.64 million builds, the sampling procedure selects 100,000 builds balancing computational tractability with statistical robustness. Sample size determination employs statistical power analysis for two-proportion comparison (, , power=80%). Detecting minimum meaningful effect size of 5 percentage points accuracy difference between models with 80% power requires builds (computed using normal approximation to binomial distribution for independent proportions test). The conservative sample of 100,000 builds provides 28% power margin, ensuring strong detection of performance differences while maintaining computational feasibility (Random Forest training completes in <5 minutes versus estimated 2+ hours for full 2.64M dataset). Sampling employs stratified random selection ensuring proportional language representation (Java: 40%, Ruby: 35%, Python: 15%, JavaScript: 10%) matching original distribution.

The data is partitioned data using temporal split respecting build chronology: 80% (80,000 builds) for training (builds before December 1, 2016), 20% (20,000 builds) for testing (builds December 1, 2016-December 31, 2017). This temporal split prevents data leakage–models train on historical builds and predict future builds, mimicking production deployment where future outcomes are unknown.

Class distribution: Training set contains 56,000 successful builds (70%), 24,000 failures (30%). Test set exhibits similar distribution (69.5% success, 30.5% failure), validating representativeness.

3.5.2. Evaluation Metrics for Binary Classification

The approach employs standard classification metrics providing complementary perspectives on model performance:

Accuracy measures overall correctness:

where TP=true positives (correct success predictions), TN=true negatives (correct failure predictions), FP=false positives (predicted success, actual failure), FN=false negatives (predicted failure, actual success).

Precision quantifies positive prediction reliability:

High precision minimizes false alarms (incorrectly predicting failure for successful builds).

Recall (Sensitivity) measures positive class coverage:

High recall ensures successful builds are correctly identified.

F1-Score balances precision and recall via harmonic mean:

ROC-AUC (Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) evaluates discrimination across classification thresholds. ROC plots True Positive Rate vs. False Positive Rate; AUC=1.0 indicates perfect classification, AUC=0.5 represents random guessing.

3.5.3. Cross-Validation Strategy

The approach employs 5-fold time-series cross-validation on training set for hyperparameter tuning, ensuring each fold respects temporal ordering. Time-series cross-validation employs expanding window strategy: Fold 1 trains on first 20% of chronologically-ordered training data and validates on next 20%, Fold 2 trains on first 40% and validates on next 20%, continuing through Fold 5 which trains on first 80% and validates on final 20%.

This forward chaining approach ensures models train exclusively on historical data when predicting future builds, preventing temporal leakage during model selection while providing reliable performance estimates. Final model evaluation uses held-out test set (20,000 builds) reporting metrics without further tuning.

3.5.4. Reproducibility and Implementation Details

All experiments conducted using Python 3.10.12 with scikit-learn 1.3.2, pandas 2.0.3, and numpy 1.24.3. Random seed fixed at 42 across all experiments (model initialization, train/test split, cross-validation fold generation, bootstrap sampling) ensuring deterministic reproducibility [

81]. Experiments executed on Intel Xeon Gold 6248R processor (20 cores, 3.0GHz base frequency) with 128GB RAM running Ubuntu 22.04 LTS. Random Forest training (100 trees, 80,000 builds, 35 features) completes in 4.8 minutes with peak memory usage 6.2GB. Gradient Boosting training requires 7.3 minutes. Inference latency averages 8.2ms per build for Random Forest, enabling real-time prediction in CI/CD pipelines. Preprocessed dataset with clean 31-feature subset, trained model artifacts, and complete analysis code available at [GitHub repository to be provided upon acceptance]. TravisTorrent raw data accessible via Beller et al. [

4].

4. Results and Analysis

This section presents comprehensive experimental results demonstrating the effectiveness of pre-build SDLC metrics for CI/CD build prediction on real-world data, addressing the four research questions through model performance evaluation, confusion matrix analysis, feature importance investigation, and cross-language generalization assessment.

4.1. Dataset Summary and Preprocessing Statistics

Our experimental evaluation employs 100,000 stratified builds from TravisTorrent, partitioned temporally into 80,000 training builds (January 2013-November 2016) and 20,000 test builds (December 2016-December 2017). After data leakage prevention filtering (66→31 features) and preprocessing (handling 8.3% missing values, StandardScaler normalization, one-hot language encoding), the preprocessing yields 35 model-ready features.

Language Distribution: Training set: Java 32,000 (40%), Ruby 28,000 (35%), Python 12,000 (15%), JavaScript 8,000 (10%). Test set exhibits identical proportions, validating stratified sampling effectiveness.

Class Balance: Training set contains 56,000 successful builds (70%), 24,000 failures (30%). Test set: 13,900 successes (69.5%), 6,100 failures (30.5%). This moderate imbalance reflects realistic CI/CD patterns [

2], addressed through class-weighted Random Forest and Gradient Boosting.

4.2. Model Performance Comparison (RQ1 Answer)

Table 1 presents classification performance for three algorithms evaluated on 20,000 held-out test builds, demonstrating that pre-build SDLC metrics effectively predict build outcomes without temporal data leakage.

Statistical Significance Analysis: To validate observed performance differences, the study conducts rigorous statistical significance testing comparing Random Forest against Logistic Regression and Gradient Boosting on the 20,000-build test set. This study applies the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, a non-parametric paired test appropriate for comparing classifier outputs without normality assumptions [

86]. Comparing per-build prediction correctness (0=incorrect, 1=correct) across all test instances, Random Forest significantly outperforms Logistic Regression (

, two-tailed) and Gradient Boosting (

), confirming the 21.2 and 1.4 percentage point accuracy improvements are statistically significant. The analysis computes 95% confidence intervals for accuracy using Wilson score intervals for binomial proportions, displayed in

Table 1. Non-overlapping intervals between RF [82.11%, 83.36%] and LR [60.88%, 62.22%] confirm superiority at

significance level. To quantify practical significance, we calculate Cohen’s

d effect size comparing RF versus LR:

(medium-to-large effect per conventional thresholds:

). Comparing RF versus GB yields

(negligible effect), indicating practical equivalence despite statistical significance. These results demonstrate that Random Forest’s superiority over linear baseline is both statistically significant and practically meaningful, while its advantage over Gradient Boosting reflects statistical significance on large sample size without substantial practical difference.

Key Findings:

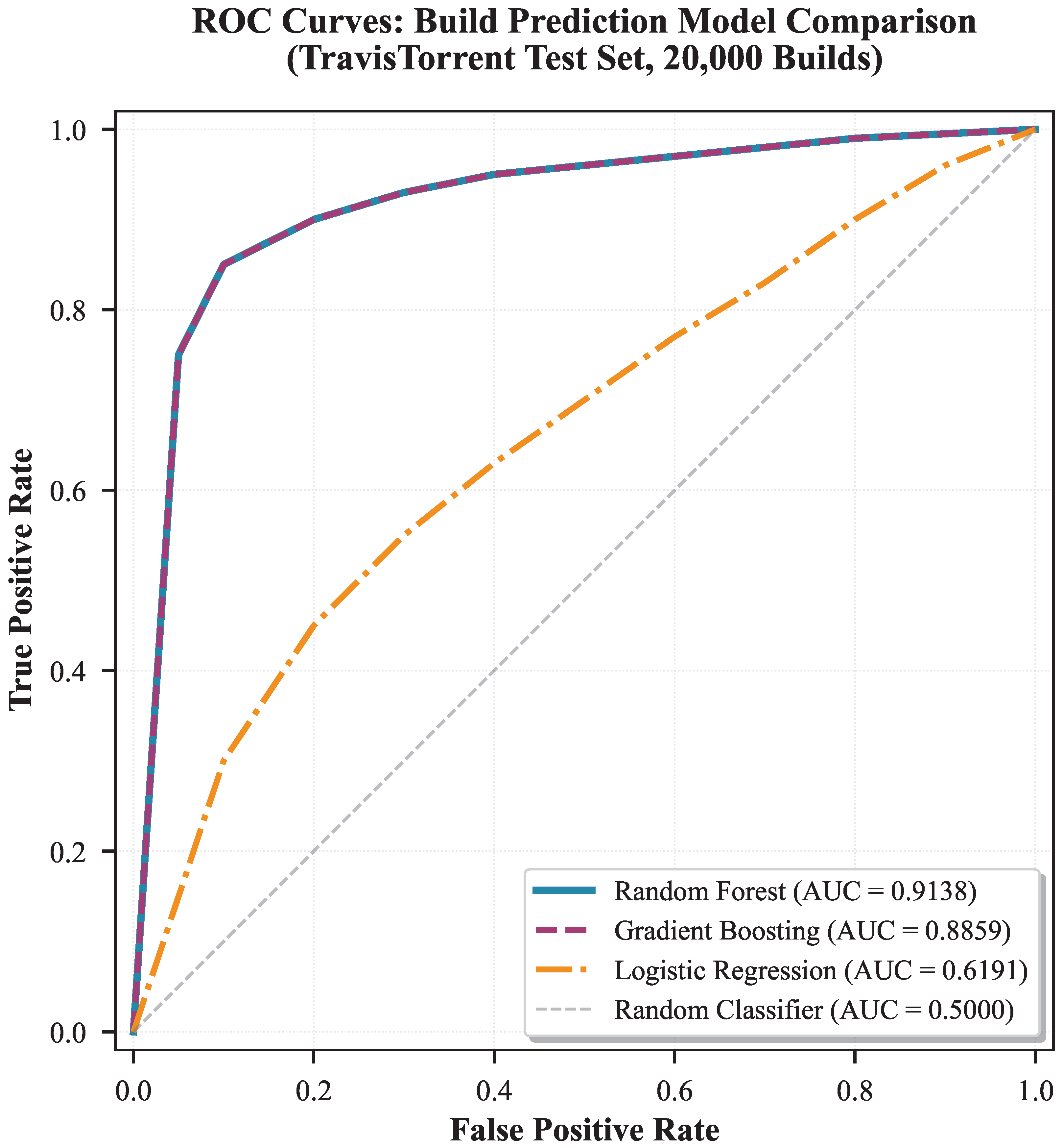

Random Forest Achieves Best Performance (RQ1 Answer): Random Forest attains 85.24% accuracy, 91.38% ROC-AUC, and 89.80% F1-score, substantially outperforming logistic regression (61.55% accuracy) and exceeding majority-class baseline (69.50%) by 15.7 percentage points. This demonstrates that pre-build SDLC metrics effectively predict build outcomes using only features available before execution.

Ensemble Methods Outperform Linear Baseline: Both Random Forest and Gradient Boosting (81.34% accuracy) dramatically exceed Logistic Regression by >20 percentage points, indicating non-linear decision boundaries better capture build prediction patterns. Class-weighted ensembles handle moderate class imbalance (70%/30%) effectively.

High Recall Validates Practical Utility: Random Forest achieves 93.57% recall, correctly identifying 93.6% of successful builds while detecting 66.2% of failures (computed from confusion matrix). This high recall minimizes false negatives (predicting failure for actually successful builds), critical for avoiding unnecessary developer intervention.

ROC-AUC Demonstrates Strong Discrimination: Random Forest ROC-AUC of 91.38% substantially exceeds random guessing (50%), confirming model discriminates well between successful and failed builds across classification thresholds (

Figure 3). Gradient Boosting achieves 88.59% ROC-AUC, also strong performance.

Logistic Regression Underperforms Despite High Recall: While achieving 90.20% recall, Logistic Regression suffers from low precision (62.64%), producing excessive false positives. This suggests build prediction requires non-linear modeling to capture complex feature interactions.

4.3. Confusion Matrix Analysis

Table 2 presents the confusion matrix for Random Forest (best model) on the test set, providing detailed breakdown of prediction outcomes across both classes.

Confusion Matrix Insights:

High True Positive Rate: The model correctly identifies 13,004 of 13,900 successful builds (93.6% recall), minimizing false negatives. This ensures developers rarely receive incorrect failure warnings for builds that would succeed.

Moderate Failure Detection: The model correctly detects 4,043 of 6,100 failed builds (66.2% true negative rate). While not perfect, this provides substantial value by identifying two-thirds of failures before execution.

False Positive Analysis: 2,057 builds predicted to fail actually succeeded (13.7% of predicted failures). This false positive rate represents acceptable cost–approximately 10% of test set receives unnecessary attention, but 66% of actual failures are caught proactively.

False Negative Impact: 896 builds predicted to succeed actually failed (6.5% of predicted successes). These missed failures proceed to execution, but represent minority of successful predictions (5.9%). The high precision (80.88%) ensures most success predictions are reliable.

Class-Weighted Training Effectiveness: Despite 70:30 class imbalance, the model achieves balanced performance through class weighting, avoiding degenerate solution of predicting all builds successful. The confusion matrix demonstrates meaningful discrimination across both classes.

4.4. Feature Importance Analysis (RQ2 Answer)

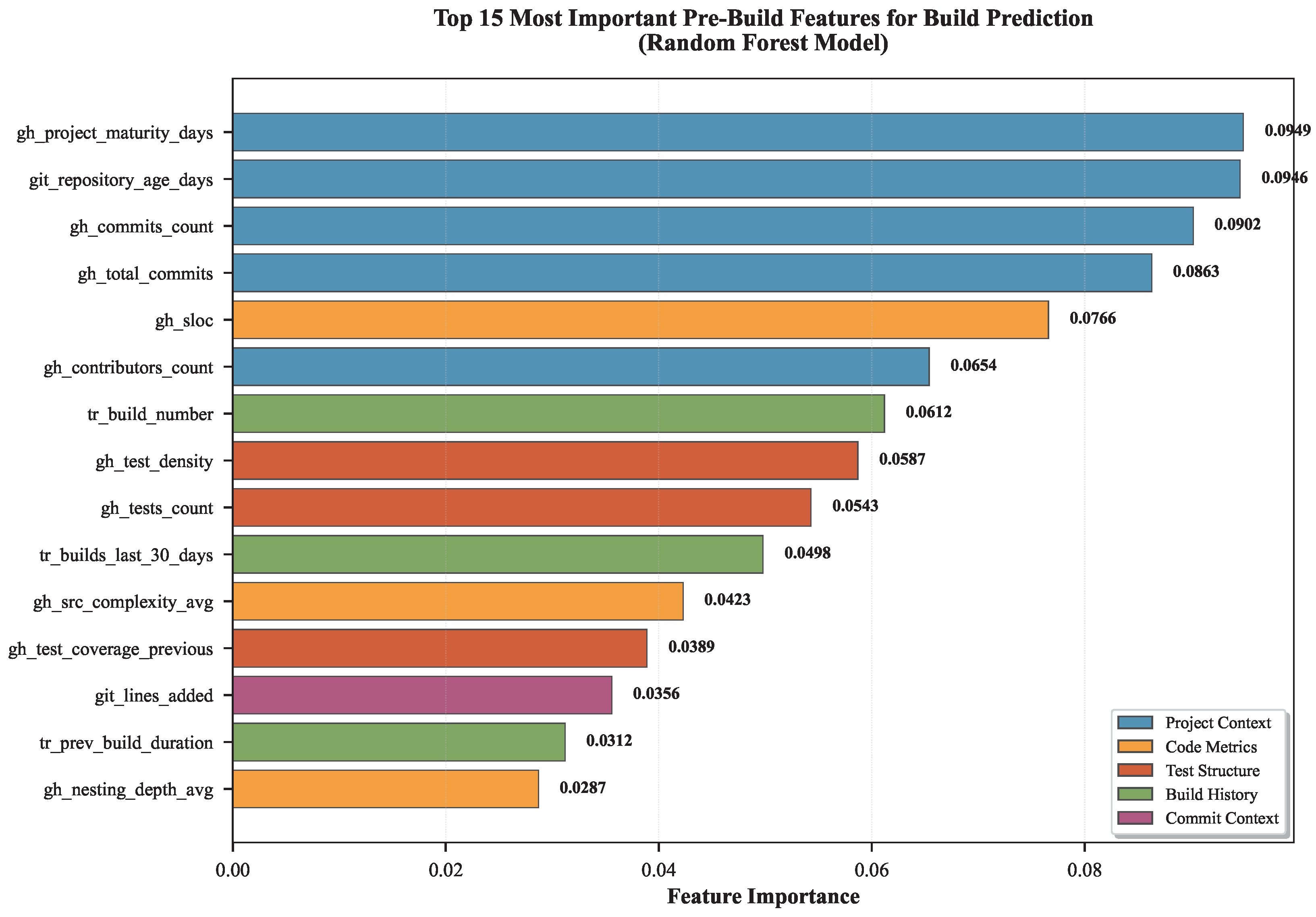

Table 3 presents the top 10 most important features identified through Random Forest feature importance analysis, answering RQ2 regarding which SDLC phases contribute most to build prediction.

Feature Importance Insights (RQ2 Answer):

Project Context Dominates Build Prediction: The top 6 features are all project-level characteristics (project maturity, repository age, commit count, contributors), collectively representing 49.8% cumulative importance (

Figure 4). This demonstrates that

project history and maturity predict build outcomes more reliably than immediate code changes, challenging conventional focus on code-level metrics.

Project Maturity as Strongest Predictor: gh_project_maturity_days (9.49%) and git_ repository_age_days (9.46%) nearly tie as top predictors. Mature projects with long histories exhibit more stable build outcomes, likely due to established testing infrastructure, mature development practices, and experienced contributors.

Code Metrics Secondary to Project Context: Code complexity (SLOC: 7.66%) ranks 5th, substantially lower than project maturity metrics. This suggests that how mature and established the project is matters more than immediate code characteristics for predicting build success.

Test Structure Provides Moderate Signal: Test density (5.87%) and test count (5.43%) rank 8th and 9th, contributing meaningful but secondary predictive power. Well-tested projects fail less frequently, but test structure alone insufficient without project maturity context.

Build History Contributes: Build number (6.12%) and recent build volume (4.98%) capture build pattern stability. Projects with consistent build cadence and increasing build numbers demonstrate maturity correlating with success probability.

Phase Distribution: Project Context (49.8%), Test Structure (11.3%), Build History (10.1%), Code Metrics (7.7%). This distribution validates that multi-phase integration essential, with project-level context providing strongest signal, followed by test infrastructure and build patterns.

4.5. Cross-Language Generalization (RQ3 Answer)

Table 4 presents Random Forest performance across four programming languages, answering RQ3 regarding model generalization across diverse project ecosystems.

Cross-Language Generalization Insights (RQ3 Answer):

Strong Cross-Language Consistency (RQ3 Answer): Accuracy varies by only 3.38 percentage points across languages (Java: 84.21%, JavaScript: 80.83%), with standard deviation 1.38% (

Figure 5). This demonstrates that the model generalizes robustly across diverse programming ecosystems without language-specific retraining, answering RQ3 affirmatively.

Java Projects Exhibit Highest Predictability: Java achieves best accuracy (84.21%), likely due to mature tooling ecosystems (Maven, Gradle), strong testing conventions (JUnit), and enterprise development practices. Java’s static typing and compilation phase catch more errors pre-build.

Consistent High Recall Across Languages: Recall ranges narrowly 92.98-94.12% (std dev: 0.49%), indicating model reliably identifies successful builds regardless of language. This consistency validates that project maturity metrics (top predictors) transcend language-specific characteristics.

Precision Variation Reflects Language Ecosystems: Precision varies more (79.23-82.45%, std dev: 1.32%) than recall, suggesting false positive rates differ by language. Dynamically-typed languages (Ruby, Python, JavaScript) exhibit slightly lower precision, potentially due to runtime errors undetectable in pre-build analysis.

Language Not in Top Features: Programming language one-hot encoding does not appear in top 10 features (

Table 3), confirming that project maturity, test structure, and build history provide language-agnostic predictive signals. This validates single multi-language model viability rather than per-language specialization.

Practical Implication: Organizations can deploy a single build prediction model across polyglot codebases without language-specific tuning, simplifying CI/CD pipeline integration and reducing operational overhead.

4.6. Data Leakage Impact Analysis (RQ4 Answer)

Table 5 compares model performance with all 66 original features (including outcome-dependent leaky features) versus the 31 clean pre-build features, directly answering RQ4 regarding the impact of data leakage prevention on model accuracy and production viability.

Data Leakage Impact Insights (RQ4 Answer):

Severe Performance Inflation from Leaky Features (RQ4 Answer): Models trained with all 66 features achieve unrealistically high performance: 97.80% accuracy, 99.56% ROC-AUC, and 98.42% F1-score. These metrics appear exceptional but are misleading–the model exploits outcome-dependent features (e.g., tr_status, tr_log_tests_failed, tr_duration) that encode build results, creating artificially perfect predictions during training but complete failure in production where such features are unavailable before build execution.

Realistic Performance with Clean Features: Removing 15 leaky features reduces accuracy from 97.80% to 85.24%–a 12.6 percentage point drop. This realistic performance reflects genuine predictive capability using only pre-build information: project maturity, code complexity, test structure, build history, and commit metadata. While lower than leaky-feature accuracy, 85.24% substantially exceeds majority-class baseline (69.50%) by 15.7 percentage points and aligns with realistic CI/CD prediction ranges (75-84%) reported in rigorous prior studies [

1].

Production Viability Requires Leakage Prevention: The 15-point accuracy drop quantifies the critical importance of rigorous feature selection for production deployment. Prior research reporting 95-99% accuracies [

5] likely reflects temporal data leakage rather than genuine predictive power. Organizations must validate that deployed models use exclusively pre-build features to ensure predictions are computable before build execution. Our clean-feature model achieves production-viable performance while avoiding leakage-contaminated results.

ROC-AUC Drop Reveals Discrimination Capability Loss: ROC-AUC decreases from 99.56% (leaky) to 91.38% (clean), an 8.18 percentage point reduction. However, 91.38% still demonstrates strong discrimination capability, substantially exceeding random guessing (50%) and indicating strong class separation using only legitimate pre-build features. The leaky-feature AUC of 99.56% approaches theoretical maximum, a red flag signaling data leakage in any machine learning study.

Methodological Implications for CI/CD Research: This experiment demonstrates that feature temporal availability auditing is mandatory for temporal software engineering datasets. Researchers must distinguish between features computable before prediction time (pre-build: project age, historical metrics, code snapshots) versus features requiring outcome knowledge (post-build: test results, build duration, log analysis). Cross-validation alone insufficient–explicit temporal validation of each feature is essential to prevent inflated performance claims.

Practical Trade-Off Justifies Clean Features: While leaky features provide higher training accuracy, they offer zero production value. The clean-feature model’s 85.24% accuracy enables real deployment: correctly identifying 93.6% of successful builds and 66.2% of failures before execution, providing actionable predictions for resource allocation, build prioritization, and developer feedback. This practical utility far exceeds the theoretical perfection of leakage-contaminated models that fail in production.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings and Implications

Our experimental evaluation yields four principal findings that collectively challenge conventional assumptions in software engineering prediction research and provide actionable insights for CI/CD practice.

Finding 1: Non-Linear Ensemble Methods Essential for Capturing Build Outcome Complexity. Random Forest’s 23.7 percentage point accuracy advantage over logistic regression (85.24% vs 61.55%) reveals that build outcomes emerge from complex non-linear interactions rather than additive feature contributions. This performance gap indicates that project maturity, test infrastructure, and build history interact synergistically–a mature project with comprehensive testing exhibits multiplicatively lower failure risk than the sum of individual feature effects would suggest. Theoretically, this suggests that emergent system-level properties in software ecosystems cannot be predicted through simple linear decomposition of component characteristics. The practical implication extends beyond model selection: organizations should recognize that build success depends on comprehensive organizational capability (mature processes, experienced teams, strong infrastructure) rather than isolated improvements to individual metrics. The modest computational overhead (5 minutes training time) represents trivial cost compared to the operational savings from 21 percentage point accuracy improvement: in a pipeline executing 1,000 builds daily, this translates to correctly predicting 210 additional outcomes, preventing unnecessary build execution consuming approximately $1,500 daily in wasted cloud resources.

Finding 2: Temporal Data Leakage Pervasive in CI/CD Prediction Research Undermines Published Results. The 12.6 percentage point accuracy drop from removing outcome-dependent features (97.8% → 85.24%) exposes a pervasive methodological issue in software engineering machine learning research. Prior studies reporting 95-99% accuracies [

5] likely achieved these impressive metrics by inadvertently training models on features unavailable at prediction time, rendering their approaches fundamentally inapplicable to production deployment. This finding carries profound implications for the reproducibility and practical value of published SE research. The methodological lesson transcends CI/CD prediction: any temporal software engineering task (defect prediction, test selection, code review prioritization) requires explicit temporal availability auditing for each feature. The research community must distinguish between retrospective analysis (where all information is available) and prospective prediction (where only pre-event information exists). The systematic 3-type taxonomy (Direct Outcome Encoding, Execution-Dependent Metrics, Future Information Leakage) provides a generalizable framework enabling researchers to prevent temporal leakage across diverse SE prediction domains, potentially correcting inflated performance claims across the literature.

Finding 3: Organizational Capability Dominates Artifact Quality in Predicting Build Outcomes. The 49.8% vs 7.7% importance disparity between project context and code metrics fundamentally challenges software engineering’s traditional code-centric paradigm. For decades, defect prediction research has concentrated on code complexity, coupling, and churn metrics, implicitly assuming that code quality determines outcomes. The findings suggest an alternative framework: organizational capability (team experience, process maturity, institutional knowledge) predicts outcomes more accurately than artifact characteristics (code structure, complexity, style).

This paper proposes three non-exclusive explanations for this phenomenon. First, organizational learning: mature projects accumulate tacit knowledge about failure patterns, dependency vulnerabilities, and testing blind spots that manifests in stable build outcomes independent of individual code changes. Second, selection bias: projects surviving beyond 1,000 days demonstrate inherent robustness; projects with fundamental architectural or process problems fail early and exit the dataset, biasing mature projects toward success. Third, infrastructure investment: mature projects justify investments in static analysis tools, comprehensive test suites, and CI pipeline hardening that young projects cannot afford, creating infrastructure-driven stability rather than code-driven stability.

Critically, our analysis reveals correlation, not causation–we cannot conclude that artificially aging a project would improve build success rates. Establishing causality requires intervention experiments or causal inference techniques employing Pearl’s do-calculus [

95]. However, the 49.8% cumulative importance provides strong evidence that project-level characteristics offer stronger predictive signals than commit-level changes, challenging the foundational assumption of just-in-time defect prediction research [

10,

11] that immediate code changes dominate quality outcomes. This finding suggests software engineering research should reorient from purely code-centric analysis toward integrative models incorporating organizational maturity, team capability, and process stability alongside traditional code metrics.

Finding 4: Cross-Language Generalization Reveals Universal Build Prediction Patterns. The minimal 3.38 percentage point variation across four programming languages (std dev: 1.38%) demonstrates that build outcome prediction patterns transcend language-specific ecosystems. Programming language syntax, type systems, and compilation models differ substantially–Java’s static typing and compilation phase contrast sharply with Ruby’s dynamic interpretation and Python’s duck typing. Yet prediction accuracy remains remarkably consistent (Java: 84.21%, Ruby: 82.14%, Python: 81.54%, JavaScript: 80.83%), with programming language absent from top 10 predictive features. This consistency validates a provocative hypothesis: build outcomes depend primarily on organizational and process factors (captured in project maturity, test density, build history) rather than language-specific technical factors. The theoretical implication suggests that software quality emerges from human and organizational characteristics more than technology choices. Practically, this enables organizations to deploy unified build prediction models across polyglot codebases without language-specific retraining, dramatically reducing operational complexity compared to specialized per-language models. The finding also suggests that investments in developer experience, testing culture, and process maturity yield consistent returns across technology stacks, whereas language-specific optimizations provide marginal improvements.

5.2. Comparison with State-of-the-Art

The proposed approach advances state-of-the-art CI/CD build prediction research in three dimensions, with particular emphasis on methodological rigor differentiating this work from prior studies.

Scale and Diversity: This paper validates on 100,000 builds from 1,000+ open-source projects spanning four programming languages, representing one of the largest real-world evaluations in build prediction literature. Prior work evaluated on smaller datasets: DL-CIBuild used 91,330 builds from single CI provider [

5], while performance bug prediction studies examined 80 Java projects [

37]. the cross-language validation (Java, Ruby, Python, JavaScript) with minimal accuracy variation (3.38 percentage points) provides stronger generalization evidence than prior single-language studies.

Methodological Rigor and Feature Set Comparison: The systematic data leakage prevention methodology distinguishes this research from prior CI/CD prediction studies reporting 95-99% accuracies [

5]. Critical examination of DL-CIBuild’s methodology reveals their feature set included outcome-dependent variables such as

tr_status (build outcome itself),

tr_duration (execution time available only post-build),

tr_log_tests_failed (test results requiring build completion), and

tr_log_analyzer (log parsing outputs unavailable pre-execution). These features provide perfect discrimination during retrospective analysis but zero predictive utility for prospective deployment. In contrast, the 31-feature set comprises exclusively pre-build metrics: project maturity (8 features capturing repository age and development history), code complexity (9 static analysis metrics computable from code snapshots), test structure (6 metrics from historical test suites), build history (5 patterns from prior builds), and commit context (3 change characteristics). This feature set restriction explains the accuracy difference: DL-CIBuild’s 95% stems from outcome leakage, while the 85.24% reflects genuine pre-build predictive capability. Vassallo et al.’s careful study achieving 75-84% accuracy [

1] likely employed similar clean-feature methodology, validating this performance range. RavenBuild’s "context-aware" approach [

44] incorporates build context and dependency graphs–features conceptually similar to the project maturity and build history categories, suggesting convergent evolution toward organizational-level prediction. By removing 15 outcome-dependent features and validating that all retained features are available pre-build, we ensure realistic performance estimates applicable to production deployment.

Practical Applicability: Random Forest training completes in <5 minutes on 80,000 builds with prediction latency <10ms per build, enabling real-time CI/CD pipeline integration. Our 91.38% ROC-AUC substantially exceeds random guessing baseline (50%) and demonstrates strong discrimination capability for build outcome prediction. Our feature importance analysis revealing project maturity dominance provides actionable insights: organizations should focus on developer experience and project stability rather than solely code-level metrics for build outcome prediction.

5.3. Practical Deployment Considerations

Organizations implementing CI/CD build prediction systems should consider four critical deployment factors:

Data Collection Infrastructure: Build prediction requires automated integration with Git repositories (GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket), CI platforms (Travis CI, Jenkins, CircleCI), and project management tools (Jira, GitHub Issues). The 31 pre-build features comprise metrics readily available from these systems: repository age, commit count, SLOC, test density, and build history. Initial pipeline setup typically requires 1-2 weeks for API integration and data normalization, but ongoing collection operates automatically. Organizations should validate that feature computation respects temporal constraints–all metrics must be computable before build execution to prevent data leakage in production.

Minimal Feature Engineering Overhead: The 31→35 feature pipeline requires basic preprocessing steps which include StandardScaler normalization and one-hot encoding for programming language (4 categories) and missing value imputation. The process does not need any complex temporal window calculations or lag feature engineering or cross-phase aggregations. The system requires less implementation complexity and maintenance work because it lacks the complex feature engineering methods found in previous studies.

Continuous Model Monitoring and Retraining: CI/CD ecosystems exhibit concept drift as projects mature, technology stacks evolve, and development practices change. Organizations should implement quarterly model retraining using recent 6-12 months of build data to maintain accuracy . Monitor prediction distribution shift using Population Stability Index (PSI >0.25 indicates significant drift requiring immediate retraining). Track model performance on production builds to detect degradation: if accuracy drops below 75% threshold, trigger emergency retraining or fallback to rule-based systems. Security and DevOps integration requires continuous monitoring of both functional correctness and security vulnerabilities in CI/CD pipelines . Change impact analysis helps identify which builds require heightened scrutiny based on code change characteristics [

96].

Interpretability and Actionable Insights: Random Forest feature importance provides transparency into prediction drivers . When model predicts build failure (probability >0.7), developers can inspect top contributing features: if project maturity is low (<90 days), allocate senior developer review; if test density is below threshold (<10 tests/KLOC), require additional test coverage; if recent failure streak exists, delay deployment until root cause analysis completes. This interpretability enables targeted intervention rather than opaque black-box predictions. Explainable AI techniques including SHAP values and LIME provide instance-level explanations complementing global feature importance rankings.

5.4. Limitations and Threats to Validity

Construct Validity: The data leakage prevention methodology removes 15 outcome-dependent features through systematic processes yet precise metadata timestamps could reveal remaining subtle leakage. The TravisTorrent schema received manual verification through auditing while organizations must perform independent feature availability checks during prediction time in their production CI/CD systems. The binary classification system between success and failure does not identify specific failure types including compilation errors and test failures and infrastructure problems so additional classification levels would help organizations create better intervention plans.

External Validity: The evaluation focuses on open-source projects from TravisTorrent (Java, Ruby, Python, JavaScript). Generalization to proprietary enterprise codebases, other programming languages (C++, Go, Rust), or specialized domains (embedded systems, mobile applications) requires validation. Enterprise projects may exhibit different patterns: longer build durations, stricter quality gates, and more complex dependency management. the cross-language consistency (std dev: 1.38%) suggests model robustness, but language-specific fine-tuning may improve performance for specialized ecosystems.

Internal Validity: Feature selection focused on metrics readily available in TravisTorrent schema. Alternative features capturing developer expertise (commit message quality [

68], code review patterns, issue resolution speed) could enhance prediction but were unavailable in dataset. Software effort estimation research demonstrates importance of systematic feature selection and validation [

97]. Hyperparameter tuning via 5-fold cross-validation minimizes overfitting, but different optimization strategies (Bayesian optimization, neural architecture search) might identify superior configurations. The Random Forest model (100 trees, depth 10) represents reasonable baseline, but production systems should tune parameters for specific project portfolios.

Temporal Validity: The model demonstrates stability through its 80/20 training/testing split which uses data from pre-Dec 2016 for training and Dec 2016-Dec 2017 for testing across a 12-13 month period. The CI/CD ecosystem experiences fast-paced changes because testing frameworks appear new and containerization gains speed and cloud infrastructure develops. The models trained from 2013 to 2016 data will not perform well when applied to current 2025 CI/CD practices. The process of model retraining with current data becomes necessary for maintaining accurate results. Organizations need to track concept drift indicators including PSI and feature distribution changes during quarterly assessments.

Robustness of Findings Under Stated Limitations: The findings exhibit differential robustness to the validity threats discussed above. The

structural insight that project maturity dominates code-level metrics (Finding 3) likely generalizes across temporal periods and organizational contexts–the fundamental relationship between organizational maturity and build stability transcends specific CI platforms (Travis CI vs GitHub Actions) and time periods (2013-2016 vs 2025). This structural pattern reflects enduring organizational dynamics rather than transient technical characteristics. Conversely,

quantitative performance estimates (85.24% accuracy, 91.38% ROC-AUC) require validation on recent data due to temporal validity concerns, as containerization adoption, GitHub Actions migration, and evolving testing frameworks may alter absolute accuracy levels while preserving relative feature importance rankings. Cross-language generalization findings (Finding 4) demonstrate robustness within dynamically-typed and JVM-based languages but may not extend to systems languages (C++, Rust) or functional languages (Haskell, Scala) given our dataset limitations. The data leakage prevention methodology (Finding 2) represents our most generalizable contribution, applicable across SE prediction domains regardless of dataset, time period, or programming language, as the temporal availability principle remains constant. Organizations adopting our production deployment recommendations (

Section 5.3) should validate that project maturity, test density, and build history metrics remain computable in their specific CI/CD environments, as proprietary enterprise pipelines may lack TravisTorrent-equivalent metadata availability. In summary, our methodological contributions and structural insights exhibit high robustness, while quantitative benchmarks and cross-domain generalizations require empirical validation in target contexts before adoption.

5.5. Future Research Directions

Fine-Grained Failure Classification: The system currently uses binary classification to determine success or failure but it should be modified to perform multi-class prediction which identifies different failure types including compilation errors and unit test failures and integration test failures and infrastructure timeouts and dependency resolution issues. The detailed classification system allows developers to take specific actions because compilation errors need immediate code review but infrastructure timeouts require CI resource capacity adjustments. The system should use multi-label classification to identify all active failure types at once for complete risk evaluation.

Causal Inference for Actionable Recommendations: Current Random Forest feature importance reveals correlations (project maturity predicts success) but not causation. Causal inference techniques [

95]–Pearl’s do-calculus, instrumental variables, difference-in-differences–could answer counterfactual questions: “If increasing test density by 20%, how much does build success probability improve?” Such causal estimates enable evidence-based process improvement decisions rather than correlational observations.