1. Introduction

The use of social networks has transformed the ways we communicate, interact, and disseminate opinions. However, these environments facilitate the spread of hate speech and cyberbullying, which most severely impact vulnerable groups. This form of digital violence generates various psychological, social, and emotional effects, making the automated detection of this discourse a research challenge.

This research aims to identify hate speech on social networks using techniques based on Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning (ML), considering emotional tone as a component to improve the accuracy of detection models.

NLP also addresses situations related to offensive language in digital environments. In particular, the use of transformers marked a breakthrough in the accuracy of automatic text classification systems [

1]. However, traditional approaches based on sentiment polarity are insufficient to capture the emotional complexity present in hostile messages.

On the other hand, emotion analysis has become established as an alternative that allows us to identify whether a message conveys a negative emotion, as well as to distinguish the type of emotion expressed, such as anger, fear, or sadness [

2]. This capability is valuable when hate speech is expressed indirectly or ambiguously, making it difficult to detect using conventional methods [

3]. Therefore, systems that incorporate emotion analysis can obtain greater sensitivity to implicit hostility patterns.

Furthermore, the use of a multimodal architecture enables the integration of contextual, linguistic, and behavioral cues, thus improving the accuracy of tasks such as the detection of cyberbullying [

4]. Furthermore, recent studies have indicated that emotion classification also expands the models’ ability to adapt to texts in minority languages or with dialectal variation [

5].

Another aspect to consider is the application of multilingual and multi-technique models that analyze content in different cultural and linguistic contexts, which is key to addressing the diversity of hate speech directed at women on a global scale [

6]. Furthermore, the use of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques gained relevance by providing transparency in the models’ decisions and strengthening their reliability in sensitive contexts [

7].

To organize and systematize recent research on this topic, we conducted a structured review using the PRISMA methodology [

8]. The PICOS model was also used to formulate research questions precisely, delimiting the population as social media users, the intervention as the use of NLP, ML, emotional analysis, the comparison between traditional and advanced models, and the result in terms of system precision [

9].

The results show the most widely used techniques for classifying emotions and hate speech, the methods employed by researchers, the most commonly recognized emotions, the main methodological challenges, the opportunities and gaps identified in the use of these techniques, the models that report the best performance according to metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score, as well as lines of future research. This information is presented in a structured manner that facilitates an understanding of the current state of the field, its advances, limitations, and emerging trends.

Among the contributions of this study are: i) the characterization of the NLP techniques and ML models most used in the classification of emotional tone in hate speech, based on the analysis of their frequency and the role they play in the textual analysis process; ii) the identification of the most frequently used methods and algorithms and the models that report the best results according to the evaluation metrics for classification models; iii) an updated overview available to researchers on existing strategies for emotional and hate speech detection, facilitating comparison between approaches and highlighting those that show the most excellent effectiveness; iv) a list of the challenges, opportunities, and lines of future research, among which the integration of the emotional dimension, the improvement in tone moderation in hate speech on social networks, and the definition of adequate criteria for the selection and training of artificial intelligence models, as a fundamental part in the construction of software artifacts oriented to its prevention.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows.

Section 2 details the procedure used for bibliographical research, combining the PRISMA and PICOS methodologies.

Section 3 presents the evaluation of the results and their discussion, highlighting the 34 primary studies obtained and performing analysis and interpretation for each research question. Finally,

Section 5 presents the conclusions and lists future lines of work.

3. Results

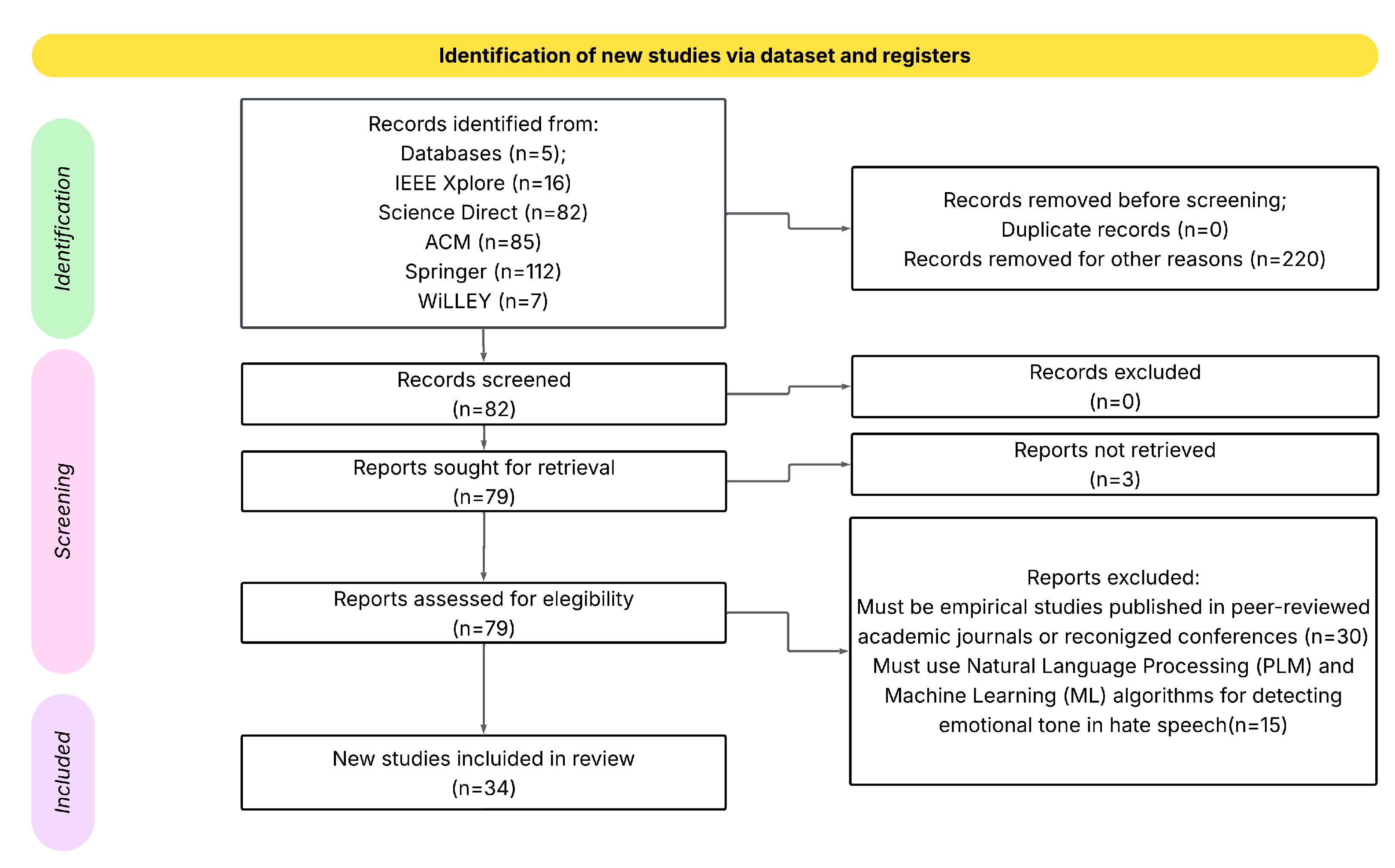

This section presents the results obtained. In summary, we identified 82 relevant articles compiled from scientific databases, including IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, ACM, Springer, and Wiley, as shown in

Figure 1. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we eliminated 48 articles that did not focus on the classification of emotional tone in hate speech using NPL and ML techniques, were not empirical studies, and did not present quantitative results. Therefore, we selected 34 primary articles for analysis. Subsequently, each article was read, reviewed, and studied to answer the research questions individually and classify the collected information. We present the analysis of the results below, grouped by each research question:

RQ1:What are the most used NLP and machine learning techniques for detecting emotional tone and/or hate speech on social media?

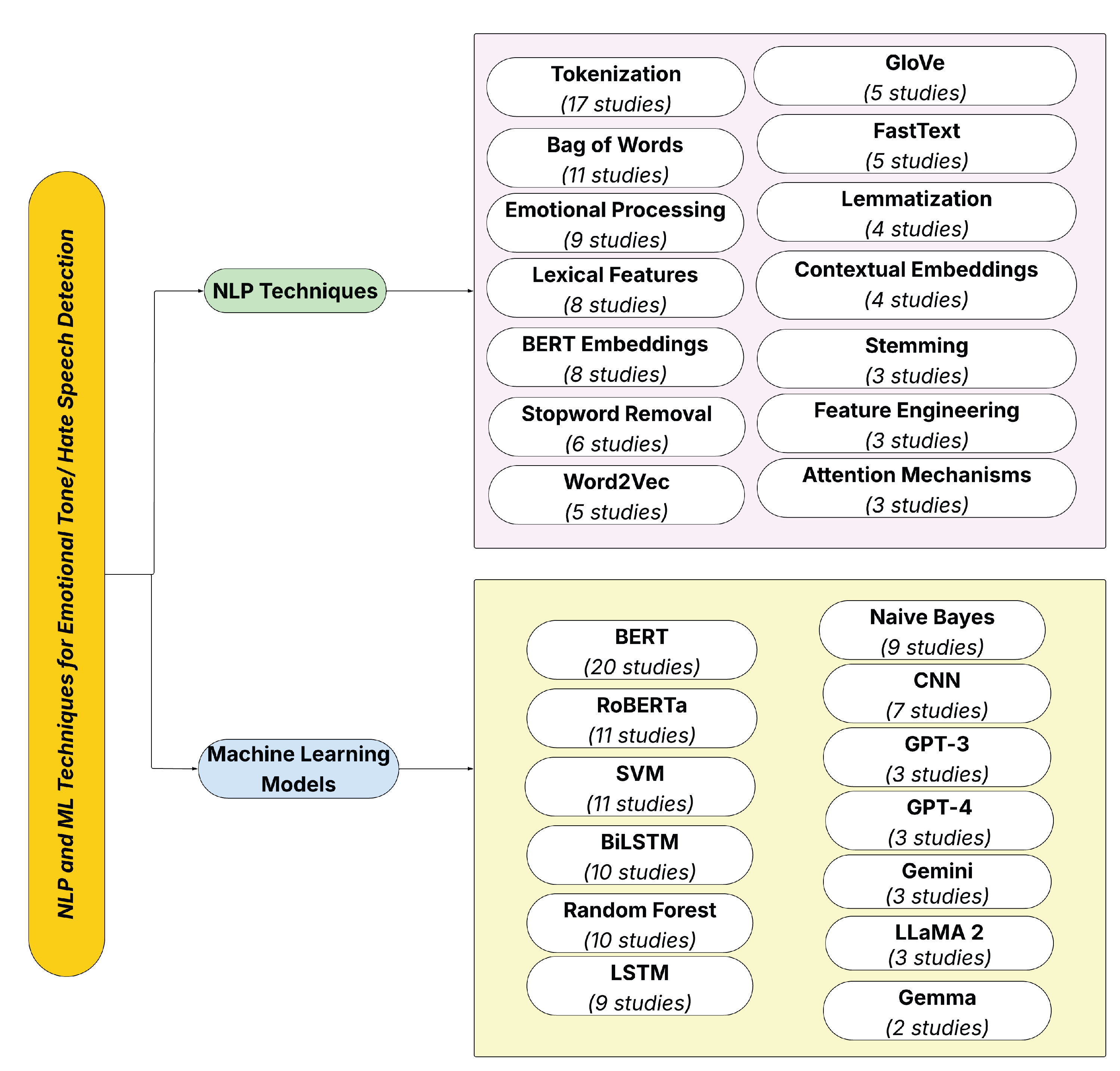

We identified several NLP techniques for detecting emotional tone in hate speech. Their respective references are listed in

Table 3, sorted in descending order by number of articles (i.e., “frequency”). We also include a "category" column, which indicates the function of each technique within the language processing pipeline. This classification distinguishes whether the method corresponds to text preprocessing, vector representation, feature extraction, and semantic or emotional analysis.

Table 3 lists the most common techniques. The most used method is tokenization (17 studies), classified as a part of textual preprocessing, which is followed by a bag-of-words (11 studies) approach, a classic textual representation technique. Within semantic and emotional analysis, emotional processing is particularly notable (9 studies). Approaches linked to feature extraction and modern contextual representation, such as lexical features and BERT embeddings (each with eight studies), are also common. Other relevant techniques include stopword removal (in 6 studies) and vector representations, such as Word2Vec, GloVe, and FastText (each with five studies). In addition, linguistic normalization methods are identified, such as lemmatization and contextual embeddings (4 studies). Additionally, we find other less frequently used techniques such as stemming, feature engineering, and attention mechanisms (3 studies).

The frequency of use of NLP techniques reveals the most widely used tools and, at the same time, indicates changes in the way the field is evolving. We find the simultaneous presence of traditional approaches, such as the bag-of-words model, alongside recent models, including BERT and attention mechanisms. The results demonstrate that classical techniques play a functional role due to their low computational cost and ease of implementation in diverse environments. At the same time, the increasing use of contextual embedding reflects a trend toward models that take into account the context in which words are used, which is key to identifying the emotional tone in hate speech.

On the other hand, the low frequency of methods such as stemming, feature engineering, and attention mechanisms raises questions about their effectiveness and the limited number of studies that evaluate them in depth, as well as how to establish the choice of techniques in future studies.

Table 4 shows the ML models, along with their frequency, references, and model type, arranged in descending order.

In

Table 4, we highlight the architecture based on pre-trained transformers, with BERT being the most widely used model (20 studies), followed by SVM, a discriminative classifier, and RoBERTa, another pre-trained transformer (11 studies each). We also observe a high presence of traditional models, such as Random Forest, a tree-based classifier, and BiLSTM, a recurrent neural network (each mentioned 10 times), as well as Naive Bayes, a probabilistic classifier. Likewise, LSTM, another recurrent neural network (9 studies), is designed to process sequential data with temporal dependencies, and CNN, a convolutional neural network (7 studies), is designed to process data with spatial structure. All of the above reflects their validity in tasks of emotional tone classification in hate speech.

It is worth highlighting more recent models, such as GPT-3, GPT-4, LLaMA, LLaMA 2, Gemma, and Gemini, all of which are generative models for training large amounts of text (LLMs), which appear less frequently (in 2 or 3 studies). However, they are showing emerging use, especially in zero-shot or few-shot approaches, which highlights their potential in tasks with less labeled data. These results indicate a growing trend toward pre-trained, contextual language models without neglecting the validity of traditional models due to their simplicity and interpretability.

Figure 2 presents a visual representation of the results summary for RQ1, facilitating the identification of the NLP techniques and ML models most used in classifying emotional tones in hate speech [

42].

RQ2:What tools do authors use to implement NLP and machine learning techniques for detecting hate speech and/or emotional tone on social media?

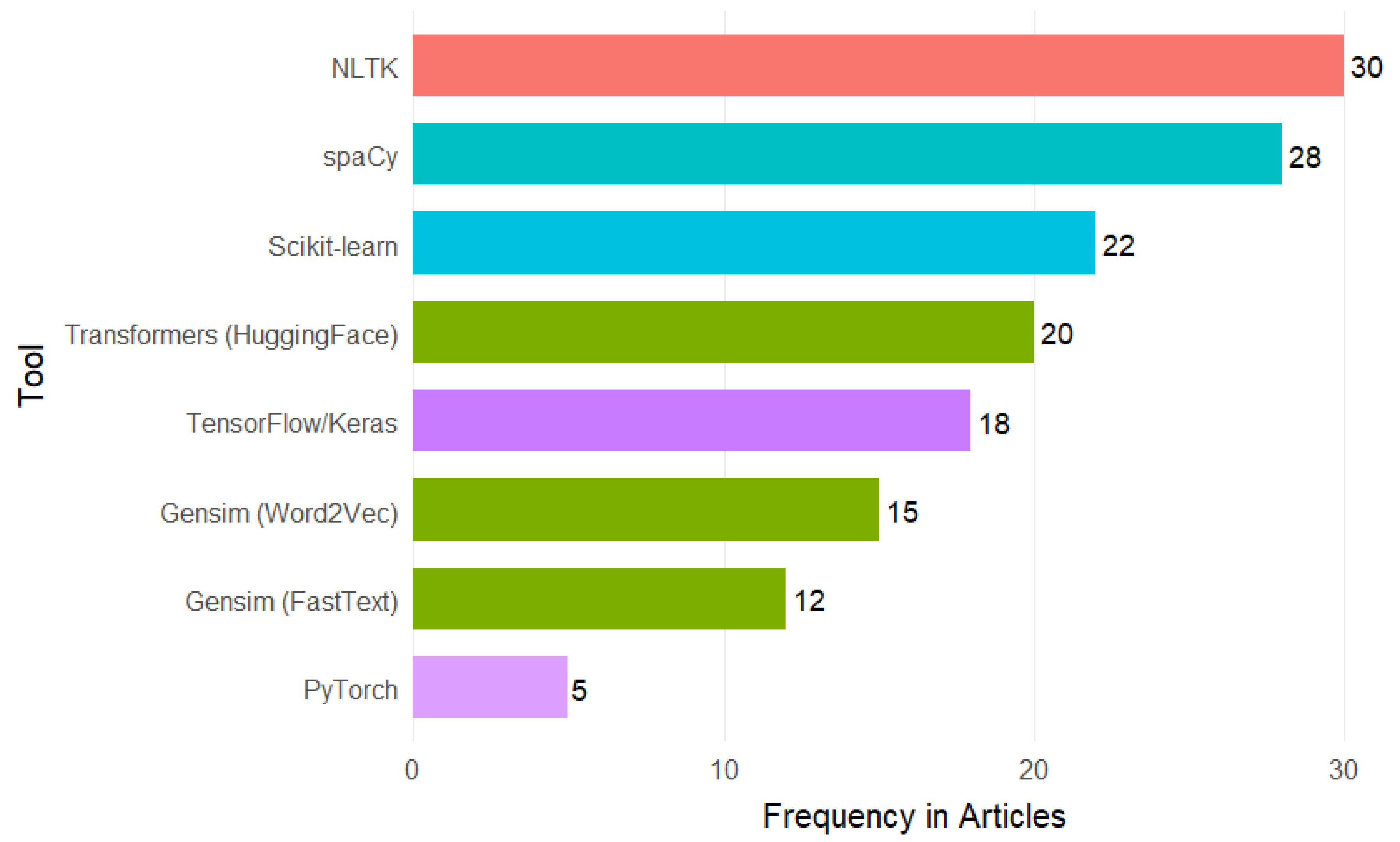

Given this research question, the uniform implementation of preprocessing with NLTK and Spacy addresses the need to manage the variability and noise inherent in social media language. [

25] highlights that NLTK facilitates the tokenization and elimination of stopwords, as well as the integration of custom dictionaries to filter hashtags and URLs. On the other hand, [

17] note that Spacy accelerates the process with its architecture, which is based on static vectors that enable efficient lemmatization of large volumes of text, thereby reducing computational costs compared to other libraries.

For static lexical representation, the authors opted for Word2Vec and FastText via Gensim, not only because of their ease of use but because both models can be quickly trained on specialized corpora. [

21] showed that Word2Vec effectively captures fine-grained semantic relationships between offensive terms and their contexts. Finally, [

30] utilizes FastText to handle mixed code (Hindi-English) cases and neologisms robustly, thereby improving the coverage of rare or emerging vocabulary.

The leap towards contextual embedding is supported by the adoption of Hugging Face’s Transformers library. [

15] compare BERT and RoBERTa in emotion detection tasks on Twitter and report that these models increase the F1-score by up to 7% compared to Word2Vec. The authors place particular emphasis on disambiguating irony and double entendres (i.e., two interpretations) common in hate speech. [

31] reinforce this finding by combining contextual embeddings with user features to improve multimodal classification.

In the modeling phase, however, the preference for Scikit-learn (SVM, Random Forest, Naive Bayes) is due to its stability and transparency; this preference was valued in studies that require interpretability, such as [

3] when designing a multi-label self-training scheme where Scikit-learn’s cross-validation yields reproducible results.

On the other hand, TensorFlow/Keras and PyTorch are the core of deep architectures in the articles by [

14], in which they implement a CNN–BiLSTM with attention and emotional lexicon in Keras. [

4] developed a multimodal Transformer in PyTorch with cross-attention that integrates text, emojis, and metadata.

Figure 3 shows the frequency of use of each tool, with the upper end dominated by the Natural Language Toolkit (30 studies) and spaCy (28 studies), which serve as pillars of preprocessing, ensuring the cleaning and normalization of the text before any other phase. Subsequently, the bars for Scikit-learn (22 studies) and Transformers (20 studies) indicate the transition to feature extraction and the comparison between classical methods and advanced embeddings. In the middle positions, Word2Vec (15 studies) and FastText (12 studies) confirm their complementary role as static representations. At the same time, the shorter TensorFlow/Keras (18 studies) and PyTorch (5 studies) show that deep architecture is only applied when more complex modeling is required.

RQ3:What are the most detected emotions in hate speech?

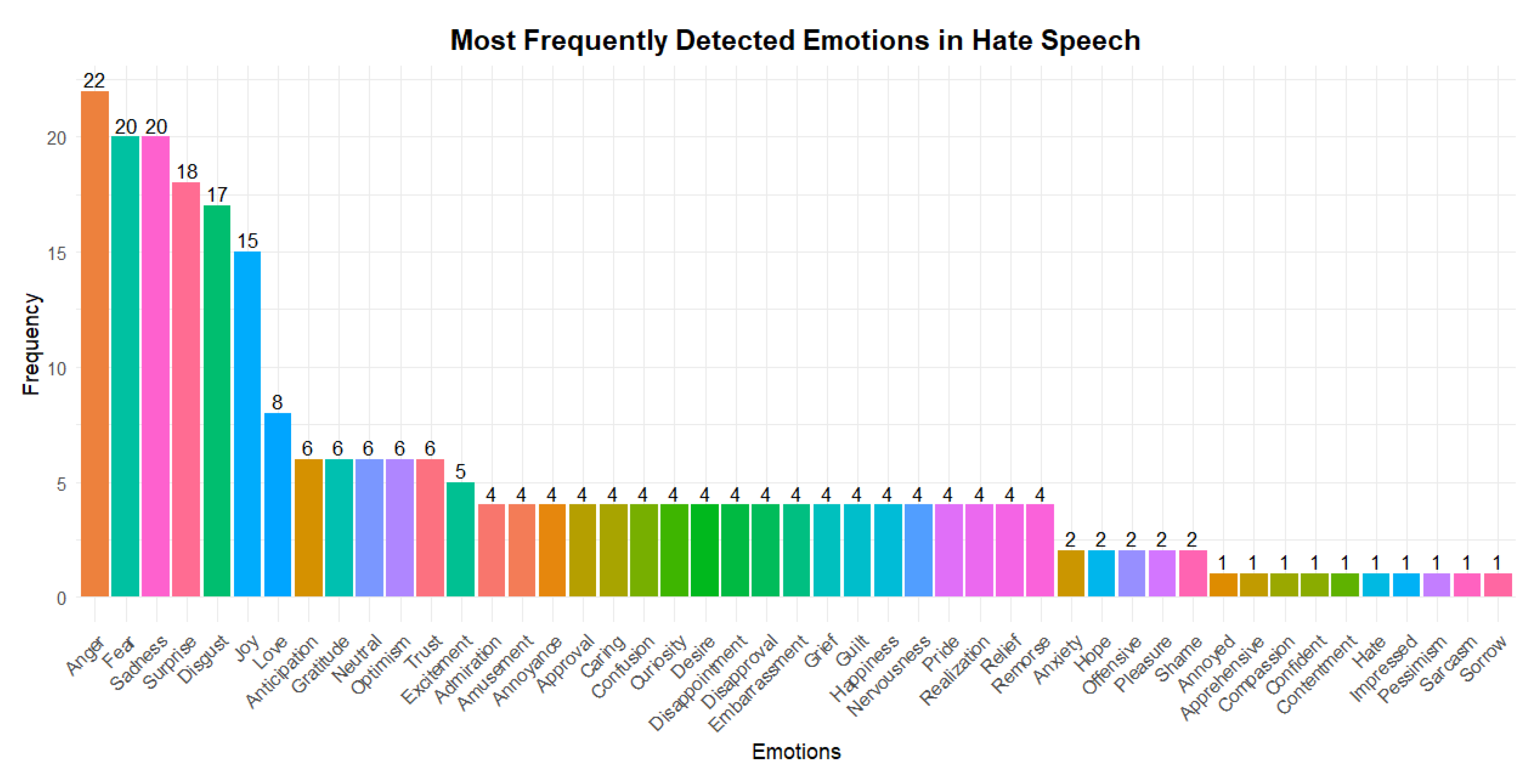

The emotions most frequently detected in hate speech are consistent with the study proposed by psychologist Paul Ekman. Ekman developed the theory of basic emotions, which recognizes the universal existence of six emotions: joy, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust. These emotions are the most used in computer science research [

43], which are strongly perceived and easily distinguishable.

In this context, we highlight that the most frequently detected emotions are anger (22 studies), followed by fear and sadness (each with 20 studies), surprise (18 studies), and disgust (17 studies). These represent responses to basic emotions in the face of threats or conflict situations and frequently appear in hate speech. This trend is supported by studies such as that of [

19]. They labeled 17.5 million tweets using distant supervision with emojis aligned with the Ekman model and found that anger, sadness, disgust, and fear were the most recurrent emotions in hate speech. Similarly, the study by [

3] analyzed three hate speech datasets and concluded that the same emotions were dominant when classifying messages with violent and discriminatory content.

Likewise, in this study, we identified emotions considered positive, such as happiness (15 studies), love, and gratitude (each in 6 studies). The presence of these emotions may be related to the ironic or ambiguous use of language, which is common in contexts where affective expressions are used to reinforce hostile discourse indirectly. As mentioned by [

5] and [

14], where speeches are analyzed that, although they seem positive, are loaded with hate or double meanings. Although these emotions do not dominate automatic analysis, they enable us to explore the sarcastic dimensions of discourse.

Finally, more than 40 different emotions were detected, demonstrating the emotional complexity behind hate speech, mainly when directed at vulnerable groups. The presence of negative emotions reinforces the notion that this type of speech is characterized by hostility, threat, and rejection. By studying these emotions, we find them extremely useful for training emotional classification models. The distribution of emotions found in this study is presented in

Figure 4.

RQ4:What are the main challenges, limitations, and future research directions for using NLP and machine learning techniques for detecting emotional tone in hate speech?

Automating emotional tone detection in hate speech faces a first challenge: emotional polarity. Traditionally, many methods rely on classifying each text as negative, positive, or neutral, but in the context of hate speech, this approach is insufficient. As shown in

Figure 5, almost half of the hostile messages (49%) are labeled as negative, but a surprising 37.8% appear with a positive polarity, and 13.3% are labeled as neutral. This distribution indicates the frequency of sarcasm, irony, or "hostility camouflaged" with friendly expressions, causing models based solely on polarity to overlook much of the offensive content [

35]. Therefore, a future direction is to incorporate communicative intent annotations and specific irony detection metrics to reduce false negatives and enrich contextual analysis.

Another critical challenge is the scarcity of high-quality, multilingual data. Most work focuses on English-language corpora, which biases and limits the validity of the systems in other languages and dialects [

1]. Without balanced repositories that include minority languages and unified annotation schemes for both hate speech categories and emotional nuances, it is tough to compare approaches and ensure cultural equity. As a future solution, it is essential to promote collaborative initiatives that create multilingual repositories with consistent annotations and quality protocols, thereby facilitating reproducibility and benchmarking.

The ambiguity and subtlety of language constitute another barrier. Expressions laden with sarcasm, youth slang, or double entendres (i.e., two interpretations) often fool the most advanced contextual models. [

35] demonstrate that even in transformers like BERT, detecting irony and emerging neologisms yields high error rates. To mitigate this, evaluation frameworks are needed that include "youth bias" or "sarcasm detection" metrics, as well as communicative intent annotations that allow algorithms to differentiate between message form and function.

On the technical side, the adoption of deep learning models is hampered by their high computational demands and opacity. Architectures such as those based on multimodal Transformers require substantial volumes of labeled data and computing power, making them challenging to utilize in resource-constrained environments [

44]. Furthermore, their "black box" nature prevents auditing and explaining decisions, a critical aspect in sensitive applications. Future directions include model distillation into lightweight versions and the integration of explainable AI (XAI) techniques that justify predictions and facilitate adoption in contexts of high social responsibility.

Finally, a multimodal fusion of text, images, emojis, and user metadata will enrich the emotional analysis, as demonstrated by [

4], who incorporate cross-attention in Twitter. However, these approaches require synchronized and labeled datasets across modalities, which are still scarce in the literature. Future work should focus on developing multimodal annotation protocols, exploring temporal alignment methods, and studying how to efficiently combine signals from different channels to capture emotional tones more holistically.

Figure 5 presents a visualization that empirically reinforces these findings. The results indicate that the predominant emotional polarity in hate speech is negative (49%), followed by a surprising proportion of positively polarized messages (37.8%) and a minority of neutral messages (13.3%).

The pattern in

Figure 5 is consistent with what is expected, given that hate speech is often charged with emotions such as contempt, anger, or rejection. However, the high proportion of messages classified as positive or neutral points to another dimension of the problem. Many hostile messages are crafted to appear benign or employ emotionally positive grammatical structures that conceal harmful content. This is consistent with the argument by [

35], who argue that contemporary language, particularly among young people and on social media, includes forms of expression that are difficult to capture by outdated or biased models. The presence of these disguised emotions underscores the need to incorporate emotional detection as an integral part of automated moderation systems.

Furthermore, the possibility that hate speech may be perceived as emotionally neutral also raises methodological questions. [

1] suggest that emotion should be assessed in conjunction with the full communicative context rather than solely from the plain text. Consequently, the detection of emotional tone in hate speech should consider not only polarity but also its implicit manifestation, its temporal evolution, and its relationship to the conversational environment. In this sense, the contributions of [

44] on multimodal models open the door to a more holistic and nuanced detection, allowing us to understand not only the content but also the intention and emotional impact of messages.

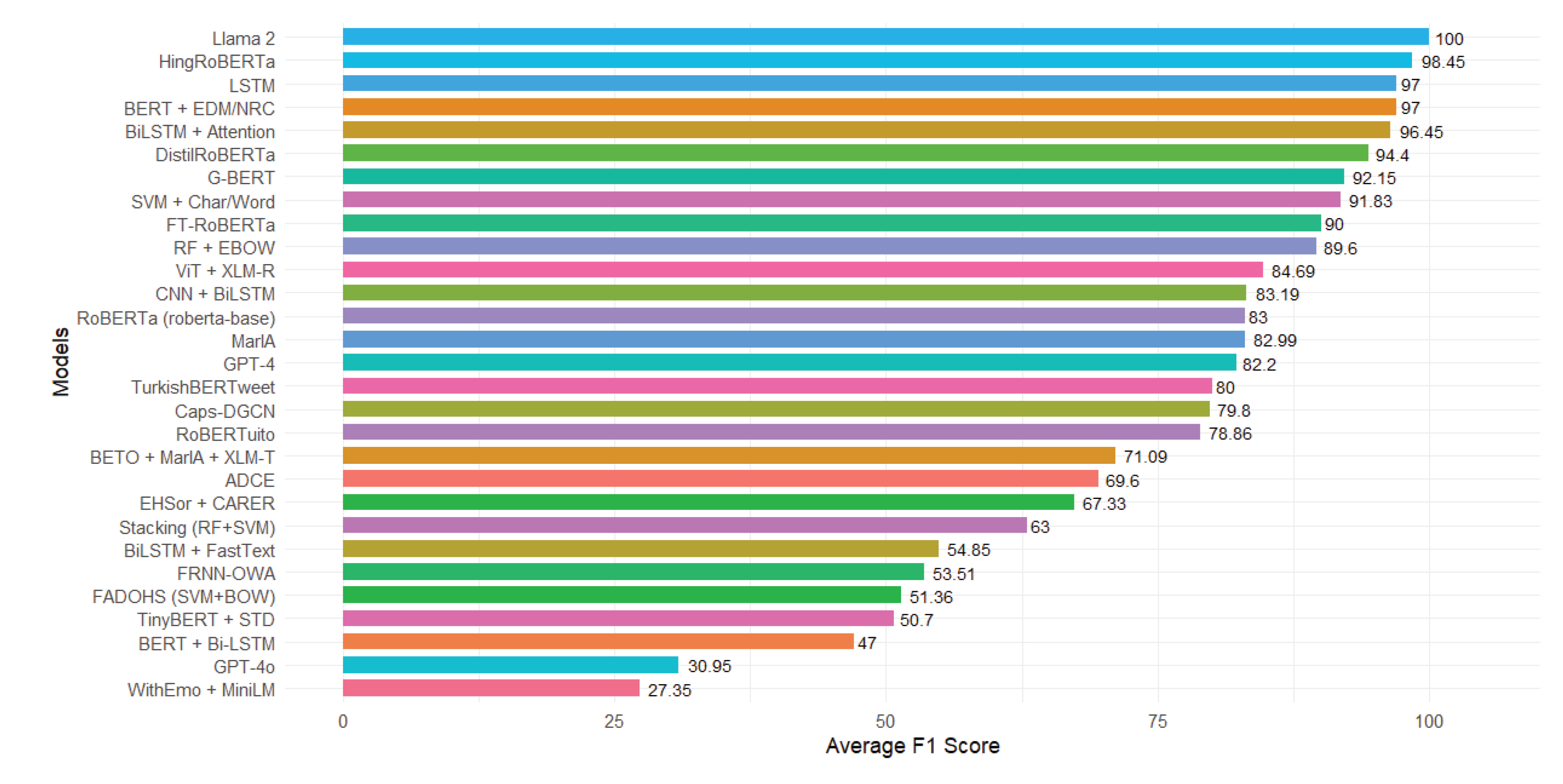

RQ5:Which NLP or machine learning models perform best in emotional tone classification based on metrics such as precision, recall, or F1 score?

In analyzing the primary studies, researchers used the F1 score, a metric that represents the harmonic meaning between precision and recall, to detect emotional tone in hate speech. This measure provides a balanced evaluation when working with datasets that have a class imbalance. A value close to 1 (or 100%) indicates that the model correctly identifies and retrieves relevant instances.

Based on the F1-score analysis, the LLaMA 2 model achieved 100% performance on this metric, positioning itself as the most practical for classifying emotional tone in hate speech. This result was obtained by applying context-based learning to five examples within the Google Play dataset, which features a small number of labeled records and an uneven distribution between classes.

The LLaMA 2 model operates on a transformer-like architecture that implements RMSNorm normalization, employs the SwiGLU activation function, and utilizes rotational position encoding. It was trained with trillions of tokens and can handle long inputs, which facilitates the interpretation of broad contexts. The model does not require weight tuning, as it generates predictions only from examples within the same input message; this enables its application in scenarios where there is insufficient data for supervised training.

On the other hand, HingRoBERTa, which specializes in Hindi-English code-mixed texts, follows with a 98.45% score [

28]. LSTM [

17] and BERT combined with EDM/NRC (Emotion Detection Model and NRC Emotion Lexicon) [

14], both with a 97% score, reflecting the usefulness of classical models and lexical techniques in specific contexts.

Likewise, other models achieved outstanding results, such as BiLSTM with attention mechanisms, which scored 96.45% [

7], DistilRoBERTa, which scored 94.4% [

31], and G-BERT, which scored 92.15% [

20]. These values show a preference for Transformer-based models and combinations with emotion-focused attention techniques or embeddings, which demonstrate the ability to capture emotional context in language.

Figure 6 presents the best-performing models based on their average F1 score, highlighting the effectiveness of modern architecture compared to classical approaches.

4. Discussion

This study presents an analysis of the existing literature on the classification of emotional tone in hate speech, utilizing natural language processing and machine learning techniques. Every aspect was considered, from the methodology to the results obtained. Through a selective search and review of publications available on IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, ACM, Springer, and Wiley digital databases, we identified 82 articles initially. Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we selected 34 relevant primary studies from these sources.

Firstly, we examine the most frequently used natural language processing techniques. These include tokenization, the most common approach, bag-of-words, emotional processing, BERT, Word2vec, GloVe, FastText, lemmatization, stop-word removal, and attention mechanisms. These techniques facilitate the preparation and transformation of texts to identify patterns that aid in detecting emotional tone in hate speech. We see a growing trend toward approaches that combine traditional processing with context-based deep learning models. This methodological evolution demonstrates that the field is migrating toward more complex models that not only analyze the surface of the text but also incorporate deeper semantic elements.

Regarding machine learning models, we identified a higher frequency in Transform-based architecture, with BERT being the most used, followed by its variant RoBERTa. We also identified traditional models, such as SVM, Random Forest, and Naive Bayes, as well as neural network models, including CNN and BiLSTM. Additionally, we explored the use of models like GPT-3, GPT-4, LLaMA 2, Gemini, and Gemma. Although these were less frequently used, they reflect the potential in tasks where labeled data is scarce, and they can apply learned knowledge in other contexts (i.e., zero-shot or few-shot learning). Recently, advanced and pre-trained models that have been adopted have shown promising results. However, it is essential to investigate further why some less-used yet high-performing models, such as LLaMA 2, have not yet been widely adopted. This could be due to factors such as code availability, implementation difficulty, or lack of external validation.

It is important to note that some of the best-performing models are not the most commonly used in reviewed studies, demonstrating that frequency of use is not always directly related to their effectiveness. Among the models with the highest F1 scores are LlaMA 2 (100%), HingRoBERTa (98.45%), and models such as LSTM and BERT+EDM/NRC (97% each). These results indicate that less-cited models can outperform the most popular ones. This finding highlights the need for future research to be more inclusive of replicating well-known architecture; instead, recent proposals that have demonstrated greater generalization and accuracy should be explored.

Regarding the identified emotions, we find an alignment with Ekman’s theory of emotions. When comparing negative and positive emotions, the former predominates. Among them, anger, fear, and sadness stand out as the most frequent, which is consistent with the hostile nature of this type of discourse. When discussing positive emotions, we encounter happiness, love, and gratitude, which, although ostensibly positive and non-harmful, can be associated with the use of ironic or ambiguous expressions, adding complexity to the analysis and highlighting the need to improve approaches that can capture less explicit semantic nuances. Along these lines, [

35] highlight those hostile expressions disguised as positive are increasingly frequent in youth speech, representing a considerable challenge for models that work solely with emotional polarity, thus generating a high number of false negatives.

On the other hand, we underline a series of challenges and limitations in the use of NLP and ML techniques for detecting emotional tone in hate speech. One of the primary issues is linguistic and cultural bias, as evidenced by the predominance of models trained in English or Arabic. This highlights a lack of multilingual databases, which limits the models’ generalization capabilities. Furthermore, the ambiguity of language in expressions such as irony or sarcasm, which are increasingly common among young people, represents an obstacle, as they often elude traditional detection mechanisms. This situation highlights the urgent need to build multilingual and culturally diverse corpora with more refined emotional annotations, allowing for the training of models that are adaptable to different sociolinguistic contexts.

Among the limitations inherent to machine learning models for detecting emotional tone in hate speech using ML and NLP, we identify those based on deep learning, such as BERT, RoBERTa, GPT-3/4, BiLSTM, and CNN, which are computationally intensive, making them difficult to implement in low-resource environments. Furthermore, since they are "black box" models, the interpretability of the results is reduced, which is a fundamental aspect in the detection of hate speech, where transparency is required to avoid unfair or arbitrary decisions. Some models can repeat biases that already exist in the data and, therefore, end up treating certain groups poorly or unfairly. In this sense, it becomes essential to incorporate Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques that allow the models’ decisions to be audited and ensure their behavior is ethical and responsible.

Similarly, despite its widespread adoption, NLTK has efficiency limitations, being considerably slower than modern tools like spaCy in basic preprocessing tasks. However, spaCy sacrifices flexibility in favor of performance, which limits its adaptation to experimental contexts. Meanwhile, TensorFlow/Keras, although powerful, can be complex to debug and excessive in scenarios where deep modeling is not required, which limits its use in studies with limited computational resources.

Finally, we emphasize that the findings of this systematic review offer an insight into the current state of the techniques and models most commonly used for detecting emotional tone in hate speech, which highlights the need to continue improving tools to address the complexity of language in the digital environment to make hate speech safer and more respectful. In this regard, it is recommended that future research advance toward the development of hybrid models that combine supervised approaches with deep semantic interpretation capabilities. Additionally, we suggested cross-validating models in different regions, designing multimodal annotations that incorporate text, emojis, and user context, and integrating systems that not only detect emotions but also interpret the communicative intent behind messages.