1. Introduction

Patients with end-stage renal diasease (ESRD) undergoing chronic hemodialysis (HD) have significantly higher mortality rates than the general population, which is aggravated by diabetes mellitus (DM) [

1,

2,

3]. Cardiovascular (CV) disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in diabetic chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients, it increases further the overall CV disease risk, being responsible for over half of all mortalities [

4,

5,

6]. DM is one of the most common causes of kidney failure in the United States and worldwide. In diabetic HD patients, besides glycemic control other cardiovascular risk factors are also important [

7].

Exploring risk factors is crucial for enhancing the survival rates of these patients. Volume management is an essential and vital component of dialysis treatment [

8]. The increased risk of cardiovascular mortality in HD patients is linked to extracellular volume overload [

9,

10]. However, intradialytic hypotension (IDH) caused by aggressive volume removal, resulting in myocardial stunning, is also associated with higher mortality and morbidity 11]. The challenge is to determine the volume status and the appropriate amount of fluid to be removed during HD, specifically the ultrafiltration volume (UV). An increased ultrafiltration rate is linked to unfavourable cardiovascular outcomes [

12,

13,

14].

Fluid overload, together with conventional and end-stage kidney disease-related risk factors, such as renal anemia, chronic inflammation, vascular calcifications and secondary hyperparathyroidism, leads to structural and functional changes in the myocardium and arteries. We have previously described the relationship between UV variability and myocardial abnormalities in patients undergoing chronic dialysis [

15].

Visit-to-visit UV variability has also been shown to predict all-cause mortality in dialysis patients [

16]. We have demonstrated in a previous study that major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and all-cause mortality were associated with ultrafiltration volume variability standard deviation (UVSD) and coefficient of variation (UVCV) in patients on chronic hemodialysis [

17].

This study aims to explore the prognostic impact of diabetes mellitus in hemodialysis patients with high ultrafiltration volume variability. We retrospectively analysed patient records to study the interplay between diabetes status and visit-to-visit ultrafiltration volume variability on patient outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

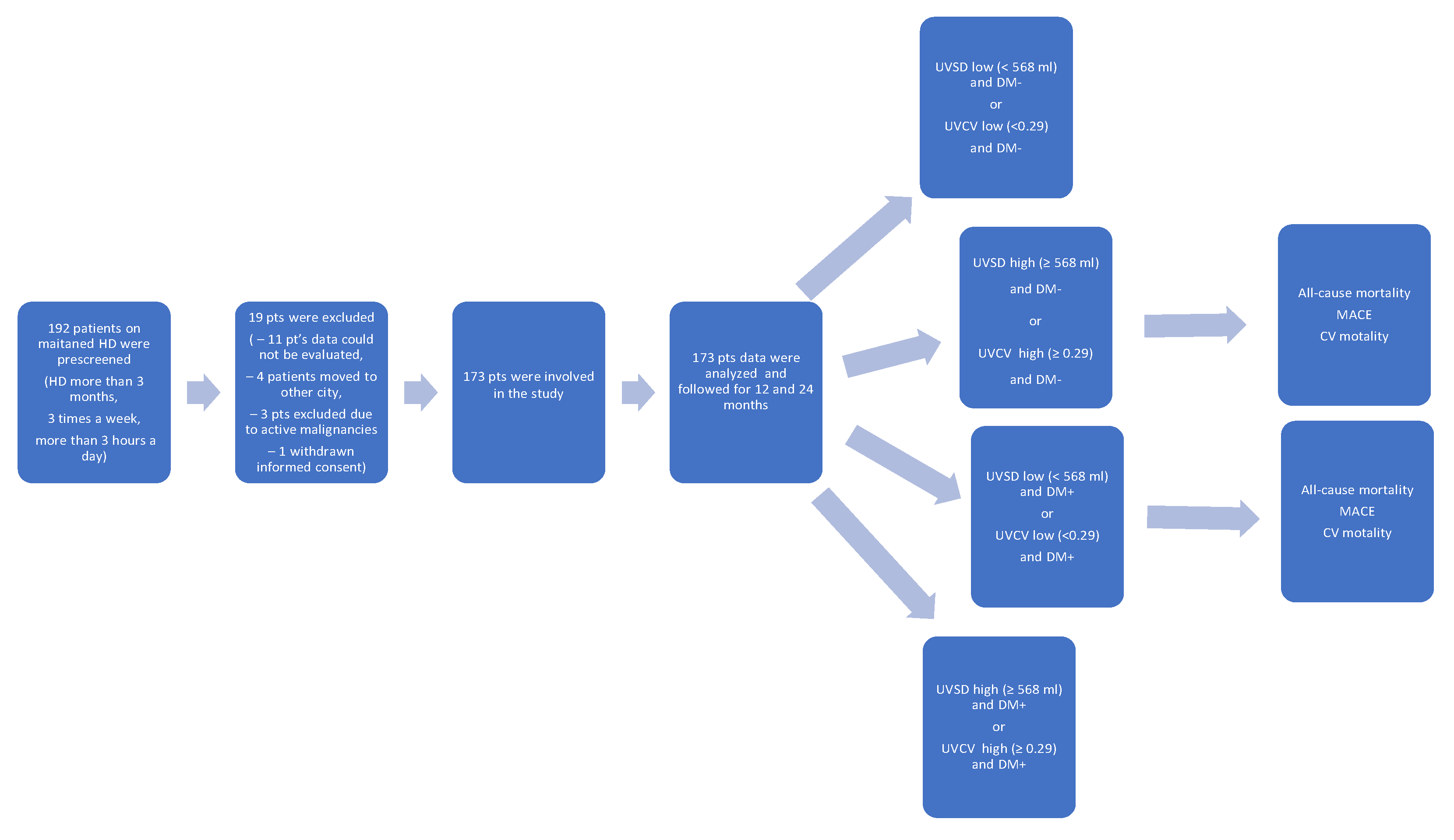

Data from 173 HD patients who underwent dialysis from January 2022 to December 2023 at the National Dialysis Center Pécs were retrospectively analysed (

Figure 1). Patients undergoing maintenance HD treatment at our center for at least three months were included. All patients received 4 hours of conventional HD three times a week. The sodium concentration of the dialysis fluid was 135–140 mmol/L, individualised if needed, but preferably unchanged during the observation period. The observation period lasted until the occurrence of MACE or death. If MACE did not occur, the final follow-up time was the most recent visit. Exclusion criteria were as follows: age<18 years; temporary dialysis in our center; kidney transplantation during the observation period; having less than 3 HD sessions/week and an unclear medical history or missing clinical information. Clinical and laboratory data, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), presence of hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure and peripheral vascular diseases) and etiology of chronic kidney disease were recorded before the beginning of the observation period.

Blood pressure measurements were performed pre-HD, every 60 min during HD treatment and post-HD using a calibrated sphygmomanometer. Serum levels of intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), albumin, calcium, phosphorus, and hemoglobin were obtained from the most recent regular laboratory examinations using blood samples collected before HD.

2.2. Definitions of UV Variability

After a dialysis adaptation period lasting for at least 3 months the observation period started, and a series of visits were conducted for 12 consecutive months to evaluate UV variability. Each dialysis session was regarded as a visit where dialysis-related information was recorded. The standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) were calculated using the indices of UV variability. The CV is the SD divided by the mean. UV data during the observation period were recorded and used to calculate the UV variability.

The following formulas were used for the calculations [

13]:

where n is the total dialysis time of each patient. Mean was calculated from all the UV data.

2.3. Definition of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events

MACE were defined as a composite endpoint of nonfatal stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction, peripheral artery revascularisation, and cardiovascular death.

2.4. Conventional Echocardiography Measurement

Comprehensive echocardiographic measurements were performed using a 3-MHz transducer and commercial ultrasound system (Mindray DC-80A; Mindray Global, Nanshan, Shenzhen, China). The imaging procedures followed standard techniques, including M-mode, two-dimensional, and Doppler measurements of the left atrium. Transmitral inflow velocities were assessed using pulsed-wave Doppler in the apical four-chamber view with the sample volume placed at the tips of the mitral valve leaflets. Early diastolic (E-wave) velocities were also measured. The left atrial diameter (LAD) was determined using 2D-guided M-mode echocardiography in the parasternal short-axis view at the base of the heart.

Left atrial (LA) volume was computed using the area-length approximation formula: LA volume (mL) = [8/(3π)] [(A1 × A2)/L], where A1 and A2 represent the corresponding LA areas measured in the apical two- and four-chamber views. Of the two long axes measured in each perspective, the LA was the shortest. Left ventricular (LV) mass was calculated using the following equation: LV mass (g) = 0.8 × {1.04 × ([IVS + LVID + PWT]ᶾ − [LVID]ᶾ)} + 0.6, where IVS represents the interventricular septum, LVID is the LV internal diameter, and PWT (posterior wall thickness) is the inferolateral wall thickness. All measurements were obtained at the end-diastole. To correct for body surface area (BSA), the left ventricular mass index (LVMI) was calculated by dividing the LV mass by the BSA. We measured Left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) using the biplane-modified Simpson's rule. Echocardiography was performed by qualified cardiologists who were blinded to the patients’ clinical data.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are shown as the mean ± SD or the median and interquartile range, depending on the normal distribution results using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, whereas categorical variables are described as percentages (%). The t-test was used for normally distributed data and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data.

The chi-squared test was applied to the variable data. Hazard ratios (HR) were estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression analyses for the relationships between all covariates (including demographic, clinical, and laboratory information) and all-cause mortality. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to display the connection between UV variability and all-cause mortality, and the log-rank test was used to evaluate the results.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to compare the efficiency of the two UV variability indices in predicting 1- and 2-year survival rates. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM Company, Chicago, IL). For multiple comparisons, Bonferroni’s correction was applied, and p<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

The patient recruitment flowchart is presented in

Figure 1. A total of 192 patients were prescreened and 19 patients were excluded: 11 patients due to missing data, 4 patients had moved to another city, 3 patients had active malignancy, and 1 patient withdrew consent.

The baseline characteristics and laboratory data of the participating patients are shown in

Table 1. In the final analysis 173 patients were included. The average age was 63±13 years, with 53% being male. A total of 36 (21%) participants had diabetes, and 42 (24%) had CV disease. Arteriovenous fistulas were used for dialysis in 53% of the patients. The etiology of CKD was as follows: glomerulonephritis in 19 (11 %) patients, diabetic nephropathy in 36 (21 %), hypertension in 82 (47 %), polycystic kidney disease in 20 (12%), and other causes in 16 (9 %).

All-cause mortality, CV mortality and MACE rates in the high and low (median, ≥ 568 ml vs. < 568 ml) UVSD and (bmedian, ≥ 0.29 vs. < 0.29) UVCV groups with or without diabetes are shown in

Table 2. All-cause mortality was significantly higher in patients with diabetes than in those without diabetes after 12 months (7/137 vs. 8/36; p=0.022) and also after 24 months (13/137 vs. 17/36; p<0.001). MACEs were also significantly higher in the diabetes group than in the non-diabetes group (6/137 vs. 9/36; p=0.037) after 12 months and (11/137 vs. 17/36; p<0.001) after 24 months, respectively.

Patients were divided into four groups based on the median UVSD (low: <568 ml vs. high: ≥ 568 ml) or UVCV levels (low <0.29 vs. high ≥ 0.29), and based on the presence or absence of diabetes. There were no significant differences between the groups (low vs. high UVSD/UVCV and DM- vs. DM+) in previous CV disease (myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral artery disease).

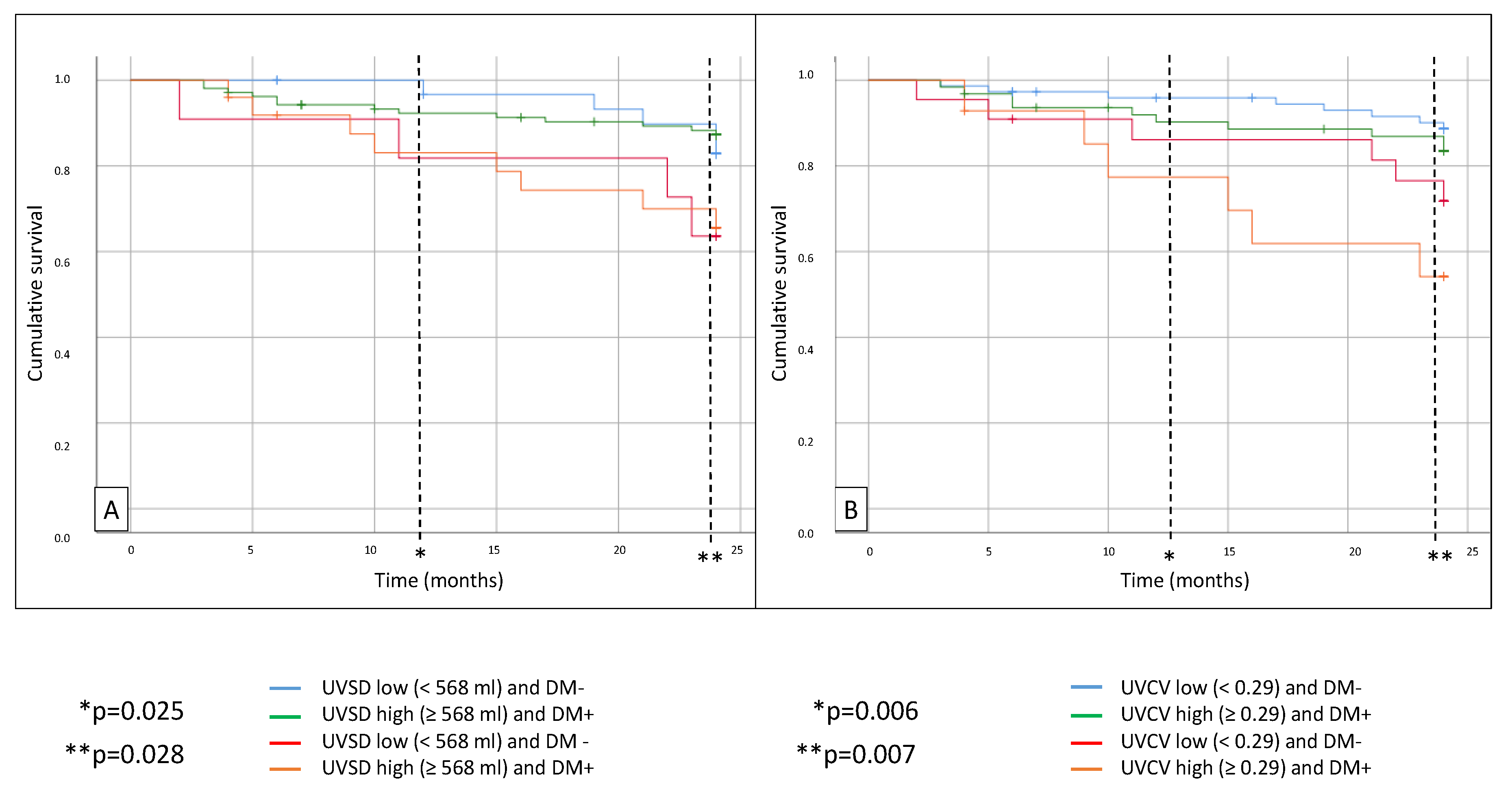

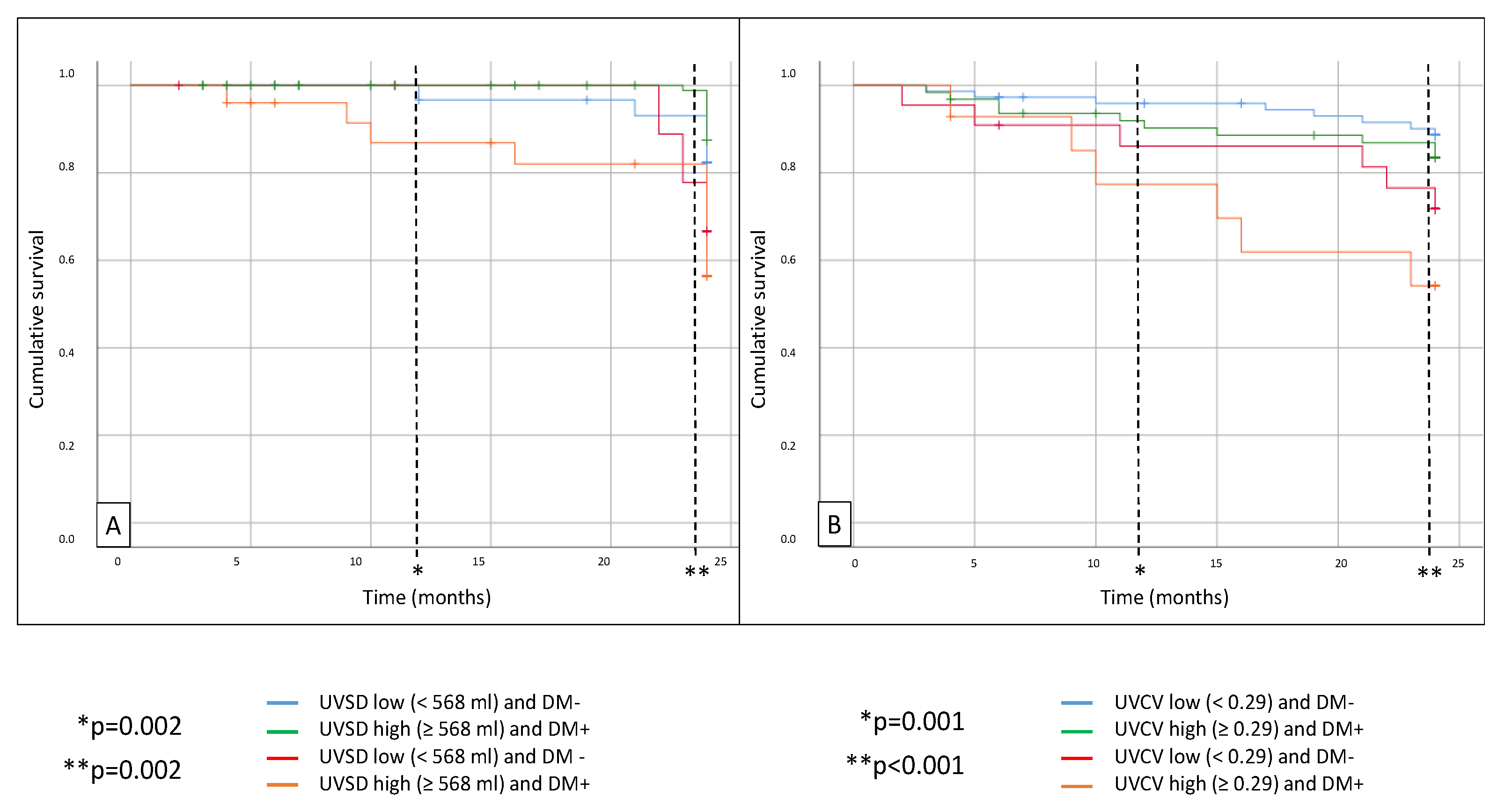

All-cause mortality was significantly higher in diabetic patients with high UVSD (p = 0.028) compared to the non-diabetic patients with low UVSD. Similarly, mortality was higher in the high UVCV group with diabetes (p = 0.007) after 24 months compared to the non-diabetic patients with low UVCV (

Figure 2). MACEs were also significantly higher in the high UVSD group with diabetes (p = 0.002) compared to the non-diabetic patients with low UVSD. The MACE rate was also significantly higher in the high UVCV group with diabetes compared to the non-diabetic patients with low UVCV (p < 0.001) after 24 months (

Figure 3). There was no significant difference between the groups in CV mortality.

According to multivariate regression analysis, factors influencing UVSD were: sex, hypertension, diabetes, and phosphate level; factors influencing UVCV were: sex, hypertension, LVMI, LVEDD, and serum albumin level (

Table 3).

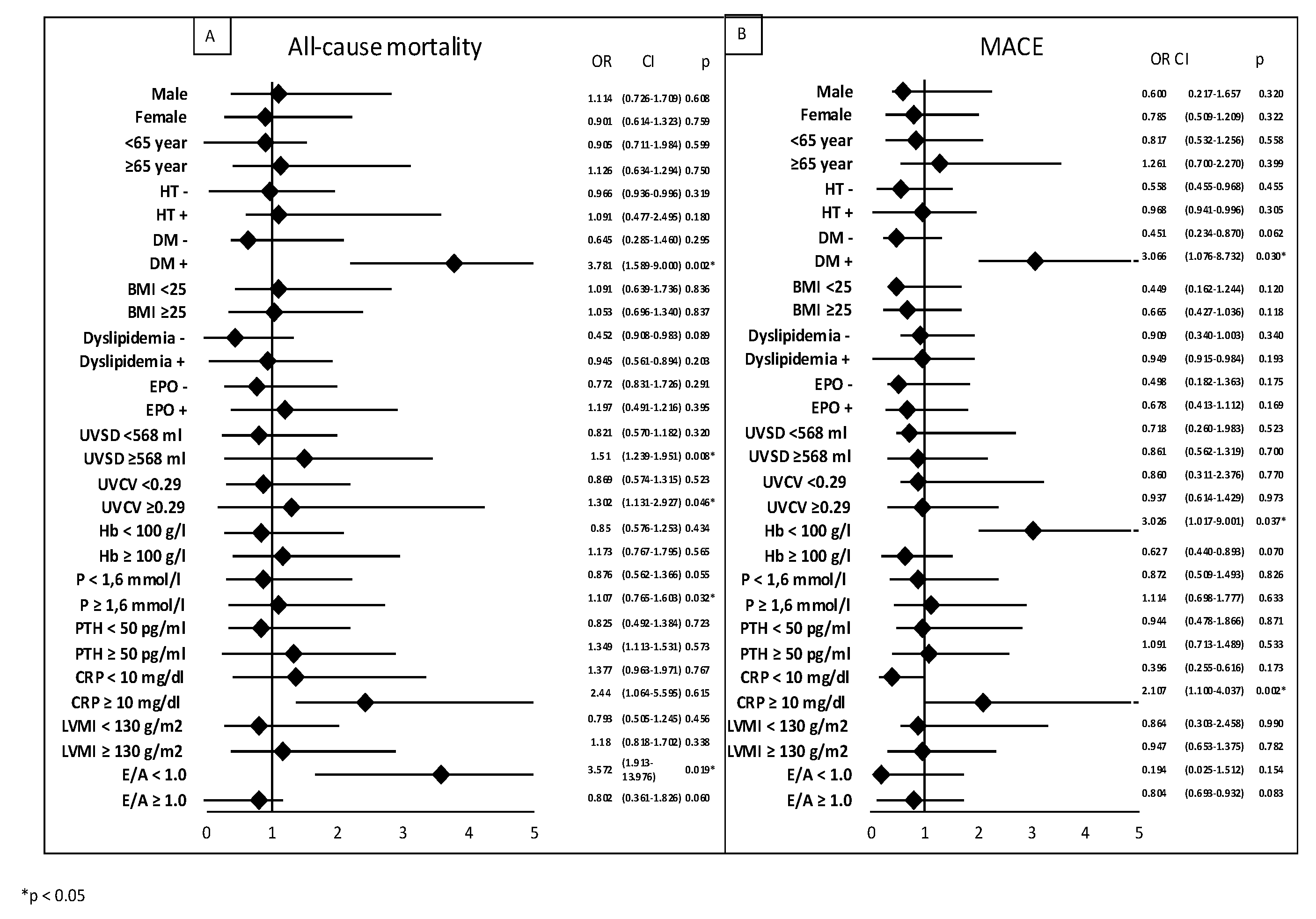

We performed subgroup analysis using logistic regression, which showed that factors influencing all-cause mortality were: DM (OR: 3.781; p = 0.002), high UVSD (OR: 1.51; p = 0.008), high UVCV (OR: 1.302; p = 0.046), and high phosphate levels (OR: 1.107; p = 0.032). Factors influencing MACE were: DM (odds ratio [OR]: 3.066; p = 0.03), low hemoglobin (OR: 3.026; p = 0.037), and high CRP (OR:2.107, p = 0.002,

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated that diabetic patients undergoing hemodialysis with high visit-to-visit ultrafiltration volume variability (UVSD or UVCV) experienced the poorest survival outcomes and the highest incidence of MACE from the examined groups. These findings highlight the combined deleterious effects of DM and intradialytic fluid management instability on the cardiovascular prognosis of patients with ESRD.

Our results suggest that UF variability may have independent effects beyond the absolute UF rate and volume. Patients with high UVSD or UVCV exhibited higher MACE rates and mortality despite having similar mean UF volumes compared to those in the lower variability groups. This indicates that an inconsistency in fluid removal may be a critical driver of cardiovascular injury. One possible explanation is that repetitive exposure to fluctuating hemodynamic stress leads to maladaptive remodelling processes that differ from those caused by sustained volume overload. Supporting this, in our echocardiographic analyses, high UV variability was associated with higher LVMI, LVEDD, and LVESD, along with elevated right ventricular pressure, particularly in patients with diabetes.

4.1. Diabetes and Mortality in Hemodialysis

It is well established that patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis (HD) face markedly higher mortality compared with the general population, with DM being one of the strongest aggravating factors [

1,

3]. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among patients with diabetes, and CKD further amplifies this risk, accounting for more than half of the total mortality in this population [

3,

4]. Epidemiological evidence shows that DM is not only one of the most common etiologies of ESRD, but also a condition that complicates the management of other cardiovascular risk factors [

5]. In our cohort, patients with diabetes had already a more adverse baseline CV profile, including a higher BMI and more severe echocardiographic abnormalities, than their non-diabetic counterparts. This supports the notion that patients with diabetes on HD represent a particularly vulnerable subgroup with limited cardiovascular reserve.

4.2. Ultrafiltration, Fluid Overload, and Outcome

Volume management is a central challenge in HD treatment. Both underestimation and overestimation of fluid removal carry substantial risks. Persistent extracellular fluid overload is closely linked to left ventricular hypertrophy, arterial stiffness and heart failure and is strongly associated with higher mortality [

9,

10]. Conversely, aggressive ultrafiltration predisposes patients to intradialytic hypotension (IDH) and myocardial stunning, which contribute to progressive cardiac dysfunction and increased risk of death [

11]. Striking the optimal balance between achieving euvolemia and avoiding rapid volume shifts remains difficult in clinical practice [

12].

Previous studies have largely focused on absolute ultrafiltration rates. Several large-scale studies have shown that high UF rates, typically exceeding 10–13 mL/kg/h, are associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes and increased mortality [

13,

14,

18,

19,

20]. The contribution of UF variability has only recently been investigated. Zhang et al. demonstrated that visit-to-visit UV variability predicted all-cause mortality in Chinese HD patients, especially in older male individuals with comorbidities [

16]. Our previous investigation also showed that UV variability was independently associated with survival in a Hungarian HD population [

17]. The present study extends these observations by demonstrating that UV variability has the greatest prognostic impact on patients with diabetes.

4.3. Mechanisms Linking UV Variability to Adverse Outcomes

The pathophysiological basis for the harmful effects of UV variability is probably multifactorial. Excessive interdialytic weight gain followed by abrupt ultrafiltration induces cyclic stress in multiple organ systems, particularly the cardiovascular system [

21]. Previous studies have shown that recurrent volume fluctuations promote cardiac chamber remodelling [

22], diastolic dysfunction, and repeated episodes of myocardial ischemia and stunning [

23,

24]. These changes contribute to irreversible myocardial fibrosis, ventricular dilatation, and systolic impairment. Beyond the myocardium, volume variability exerts deleterious effects on the peripheral arteries, accelerating vascular stiffness and endothelial dysfunction [

25,

26]. Collectively, these processes can explain the strong link between volume instability and increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [

27,

28,

29].

4.4. Diabetes as a Potentiating Factor

The interaction between diabetes and UF variability requires particular attention. Diabetic cardiomyopathy is characterised by the accumulation of advanced glycation end products, increased myocardial collagen deposition and impaired diastolic relaxation, ultimately leading to preserved ejection fraction heart failure (HFpEF) [

30]. In contrast, uremic cardiomyopathy is primarily driven by microinflammation, oxidative stress, and repeated ischemic injury due to dialysis-induced myocardial stunning [

31]. When these two conditions overlap, combined myocardial vulnerability may amplify the adverse consequences of UF variability.

In our study, patients with diabetes had significantly lower ejection fractions and E/A ratios and higher LVMI and LV dimensions than those without diabetes. These findings suggest that diabetes-related myocardial alterations exacerbate the detrimental effects of fluctuating fluid removal rates. Importantly, the worst prognosis was observed in the DM+ high UV variability group, supporting the hypothesis that the coexistence of these factors accelerates cardiovascular deterioration and all of these can cause echocardiographic changes.

4.5. Variability as a Broader Prognostic Marker

Our findings are in line with the growing evidence that high variability in various physiological parameters predicts poor outcomes in HD patients. Increased visit-to-visit blood pressure and heart rate variability has been linked to both short- and long-term cardiovascular mortality [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. High serum phosphorus, low hemoglobin and low albumin levels are asscociated with increased mortality and CV risk in chronic HD patients. Similarly, fluctuations in serum phosphorus [

40], albumin [

41], hemoglobin [

42], and heart rate [

43] have been shown to predict mortality independent of mean levels. Together, these observations suggest that variability itself may be more harmful than persistently elevated values, as it reflects impaired homeostatic mechanisms and contributes to cumulative stress on the organs. In our study, we found that UF variability likely follows this paradigm, indicating that clinicians should not only target optimal mean UF rates but also aim to minimise intersession variability.

Interestingly, UVSD and UVCV were not associated with identical clinical and biochemical factors. UVSD correlated more strongly with phosphate and PTH levels, both of which are recognised cardiovascular risk factors in patients undergoing dialysis [

44], whereas UVCV was more closely associated with traditional risk factors, such as serum cholesterol [

45]. These differences suggest that UVSD and UVCV capture distinct aspects of fluid management instability and may reflect different underlying mechanisms of cardiovascular risks.

4.6. Clinical Implications

Our findings have several clinical implications that warrant further investigation. First, diabetic HD patients should be recognised as a particularly high-risk subgroup when managing ultrafiltration. Efforts to reduce volume variability, such as individualised dry weight assessment, dietary sodium and fluid restriction or more frequent/extended dialysis sessions may improve outcomes in this population. Second, monitoring UV variability indices may provide an additional tool for risk stratification. While mean UF rates remain important, incorporating UVSD or UVCV into routine evaluations may help to identify patients at the greatest risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Finally, this study underscores the importance of integrated management of both diabetic and uremic cardiomyopathy mechanisms to reduce cumulative myocardial injury.

What could be the link between diabetes, uremia, and high UV variability? The matching point could be that both diseases cause heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), but in diabetic patients, the initiating step of the heart failure, detected by echocardiography, is left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (LVDD) and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). Lindmann et al. reported that the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and collagen deposition are important features of increased LV stiffness in patients with HF and reduced EF in diabetic cardiomyopathy [

46,

47,

48]. In contrast, in uremia, the main mechanism that leads to heart failure is myocardial stunning, and ischemia causes myocardial damage, which can cause myocardial fibrosis by micro-inflammation and oxidative stress [

49,

50]. The link between these two entities may be pathological myocardial remodeling, involving multiple factors. Volume overload and high ultrafiltration volume variability may be a triggering factor and accelerate these mechanisms. This hypothesis may explain the worse overall mortality and MACE rates observed in our study in diabetic groups with high UVSD/UVCV in hemodialysis patients.

5. Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations. This was a single-center observational study with a relatively small sample size, which may limit its generalizability. There was a relatively small number of diabetic patients, and also the cardiovascular mortality events were relatively few, precluding firm conclusions regarding this endpoint. Additionally, we did not distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes due to the small number of type 1 DM cases.

6. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that high visit-to-visit UF variability significantly worsens outcomes in HD patients, with the most pronounced effects observed in those with diabetes mellitus (DM). Both UVSD and UVCV were independently associated with increased all-cause mortality and MACE, highlighting the importance of considering variability in addition to absolute UF parameters. The coexistence of diabetes and high UF variability may synergistically accelerate adverse cardiovascular remodelling, leading to a poor prognosis. These findings reinforce the need for careful volume management and targeted strategies to reduce the variability in fluid removal, especially in patients undergoing HD with diabetes. Larger multicenter studies with longer follow-up periods are needed to validate these results and explore whether interventions aimed at stabilising UF variability can improve survival in this high-risk population.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. Balázs Sági conceived and designed the study, collected clinical data, and drafted the manuscript. Éva Fejes identified the study plot and contributed to the interpretation, drafting of the manuscript. Tibor Vas: Identified the study plot, performed statistical analysis. Botond Csiky: drafted an application for the Committee of Ethics, organized the database, and reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the University of Pécs Clinical Center Regional Research Ethical Committee (reference no. 10075-PTE 2025). All study participants provided informed consent. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to Hungarian regulations and the privacy of the individuals who participated in the study. The data can be shared upon reasonable request from the corresponding author if accepted by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics and local Data Protection Officials.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Istvánné Solymos and Gábor Borbély for their conscientious work on the study and data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

Not Applicable.

References

- Villegas Sierraa, L.E.; Agudelo, M.B.; Delgado, C.E.Y.; Jaramillo, Y.M.M.; Barragan, F.J. Interaction between the stage of chronic kidney disease and diabetes mellitus as factors associated with mortality in chronic kidney disease patients: An external cohort study. Nefrologia. 2023, 42, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.K.; Okpechi, I.G.; Osman, M.A.; et al. Epidemiology of haemodialysis outcomes. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022, 18, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puértolas, O.C.; Vizcaya, D.; Cerain-Herrero, M.J.; Gil-Terrón, N.; Cobo-Guerrero, S.; Salvador-González, B. Cardiovascular events and mortality in chronic kidney disease in primary care patients with previous type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension. A population-based epidemiological study (KIDNEES). BMC Nephrology 2022, 23, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, A.C.; et al. A personalized approach to chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1470–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zhao, S. Risk factors for mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017, 238, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loutradis, C.; Sarafidis, P.A.; Ferro, C.J.; et al. Volume overload in hemodialysis: diagnosis, cardiovascular consequences, and management. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021, 36, 2182–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahr, A.J.; Molitch, M.E. Management of Diabetes Mellitus in Patients With CKD: Core Curriculum 2022. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022, 79, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, C.; Mallamaci, F. Mapping progress in reducing cardiovascular risk with kidney disease: managing volume overload. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018, 13, 1432–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, E.; Asci, G.; Chazot, C.; et al. Controversies and problems of volume control and hypertension in haemodialysis. Lancet. 2016, 388, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaud, B.; Chazot, C.; Koomans, J.; et al. Fluid and hemodynamic management in hemodialysis patients: challenges and opportunities. J Bras Nefrol. 2019, 41, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, D.F.; Raimann, J.G.; Zhang, H.; et al. The time of onset of intradialytic hypotension during a hemodialysis session associated with clinical parameters and mortality. Kidney Int. 2021, 99, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, Y.; Sakai, K.; Hase, H.; et al. Dry weight targeting: the art and science of conventional hemodialysis. Semin Dial. 2018, 31, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, H.; Yee, J.; Weiner, D.E.; et al. Ultrafiltration rate thresholds in maintenance hemodialysis: an NKF KDOQI controversies report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016, 68, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Okuda, Y.; Sy, J.; et al. Ultrafiltration rate effects declines in residual kidney function in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2019, 50, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sági, B.; Vas, T.; Jakabfi-Csepregi, R.K.; Sulyok, E.; Csiky, B. Association between Visit-to-Visit Ultrafiltration Volume Variability, Vascular Biomarkers and Cardiovascular Parameters in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, N.; Nie, L.; Lu, C.; Chen, H.; He, W.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xiong, J. Visit-to-visit ultrafiltration volume variability predicts all-cause mortality in patients receiving hemodialysis. Ren Fail. 2023, 45, 2194439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sági, B.; Vas, T.; Fejes, É.; Csiky, B. Prognostic Significance of Visit-to-Visit Ultrafiltration Volume Variability in Hemodialysis Patients. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assimon, M.M.; Wenger, J.B.; Wang, L.; Flythe, J.E. : Ultrafiltration rate and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2016, 68, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Chang, T.I.; Kim, T.H.; Chou, J.A.; Soohoo, M.; Ravel, V.A.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Streja, E. : Association of ultrafiltration rate with mortality in incident hemodialysis patients. Nephron 2018, 139, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, J.E.; Rajabalan, A.; Cobb, J.; Lea, J.P. Proportion of Hemodialysis Treatments with High Ultrafiltration Rate and the Association with Mortality. Kidney360 2022, 3, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutradis, C.; Sarafidis, P.A.; Papadopoulos, C.E.; et al. The Ebb and flow of echocardiographic cardiac function parameters in relationship to hemodialysis treatment in patients with ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018, 29, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdogan, O.; Kayikcioglu, M.; Asci, G.; et al. Left atrial volume predicts mortality in low-risk dialysis population on long-term low-salt diet. Am Heart J. 2010, 159, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafidis, P.A.; Kamperidis, V.; Loutradis, C.; et al. Haemodialysis acutely deteriorates left and right diastolic function and myocardial performance: an effect related to high ultrafiltration volumes? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017, 32, 1402–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.G.; et al. Fluid overload is a determinant for cardiac structural and functional impairments in type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease stage 5 not undergoing dialysis. PloS One 2020, 15, e0235640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charra, B. Fluid balance, dry weight, and blood pressure in dialysis. Hemodial Int. 2007, 11, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecking, M.; Madero, M.; Port, F.K.; Schneditz, D.; Wabel, P.; Chazot, C. Fluid volume management in hemodialysis: never give up! Kidney Int. 2023, 103, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wizemann, V.; Wabel, P.; Chamney, P.; et al. The mortality risk of overhydration in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009, 24, 1574–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz Mendoza, J.; Sun, S.; Chertow, G.M.; et al. Dialysate sodium and sodium gradient in maintenance hemodialysis: a neglected sodium restriction approach? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011, 26, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, C.; Torino, C.; Tripepi, R.; et al. Pulmonary congestion predicts cardiac events and mortality in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013, 24, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindman, B.R.; Davila-Roman, V.G.; Mann, D.L.; et al. Cardiovascular phenotype in HFpEF patients with or without diabetes: a RELAX trial ancillary study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014, 64, 541–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Napoletano, A.; Provenzano, M.; Garofalo, C.; Bini, C.; Comai, G.; La Manna, G. Mineral Bone Disorders in Kidney Disease Patients: The Ever-Current Topic. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 13, 12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, İ.; Eser, B.; Özkurt, S.; Yayar, Ö.; Özgür, B.; Kayadibi, H.; Doğan, T.; Muşmul, A.; Soydan, M. Serum ADMA, endothelial dysfunction, and atherosclerosis in hypervolemic hemodialysis patients. Turk J Med Sci. 2018, 48, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amari, Y.; Morimoto, S.; Iida, T.; et al. Characteristics of visit-to-visit blood pressure variability in hemodialysis patients. Hypertens Res. 2019, 42, 1036–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.T.; Cheng, H.M.; Yu, W.C.; et al. Increased nighttime pulse pressure variability but not ambulatory blood pressure levels predicts 14-year all-cause mortality in patients on hemodialysis. Hypertension. 2019, 74, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, R.; Li, J.; Lin, L.; et al. The association between longand intra-dialytic blood pressure variability with all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2019, 48, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, C.E.; Jeemon, P.; Coleman, H.; McCallum, L.; Patel, R.; Dawson, J.; Sloan, W.; Meredith, P.; Jones, G.C.; Muir, S.; Walters, M.; Dominiczak, A.F.; Morrison, D.; McInnes, G.T.; Padmanabhan, S. Long-term and ultra long-term blood pressure variability during follow-up and mortality in 14,522 patients with hypertension. Hypertension. 2013, 62, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, L.; Yu, S.; et al. Blood pressure variability and prognosis in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Dis. 2021, 7, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Huang, J.; Yu, B.; et al. Long-term predialysis blood pressure variability and outcomes in hemodialysis patients. J Clin Hypertens. 2022, 24, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.L.; Henry, R.M.A.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Van Sloten, T.T.; Reesink, K.D.; Kroon, A.A. Blood Pressure Variability, Arterial Stiffness, and Arterial Remodeling. Hypertension 2018, 72, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Dou, L.; Zhu, M.; et al. Variability of serum phosphorus and its association with mortality among hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2018, 90, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Impact of serum albumin level and variability on short-term cardiovascular related and all-cause mortality in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Medicine. 2021, 100, e27666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.S.; et al. Impact of hemoglobin variability on cardiovascular mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2018, 50, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.M.; Huang, Y.T.; Chen, I.L.; et al. Heart rate variability as an independent predictor for 8-year mortality among chronic hemodialysis patients. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, H.B.S.; Canziani, M.E.F.; Barra, A.B.L.; Roque-da-Silva, A.P.; Strogoff-de-Matos, J.P.; Dalboni, M.A.; Moyses, R.M.A.; Elias, R.M. PTH may predict early mortality in incident patients on hemodialysis: results from a large cohort. Int Urol Nephrol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Chen, J.; Qin, X.; Yang, Y.; He, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Kong, Y.; Wan, Q.; Wang, Q.; Huang, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, A.; Liu, F.; Hou, F.; Liang, M. Relationship of serum total cholesterol and triglyceride with risk of mortality in aintenance hemodialysis patients: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Ren Fail. 2024, 46, 2334912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, H.; Chen, M.; Lindholm, B.; Wang, T. Volume control in diabetic and nondiabetic peritoneal dialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005, 37, 575–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marfella, R.; Sardu, C.; Mansueto, G.; Napoli, C.; ·Paolisso, G. Evidence for human diabetic cardiomyopathy. Acta Diabetologica 2021, 58, 983–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Schulze, P.C. Cardiac Metabolism in Heart Failure and Implications for Uremic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research. 2023, 132, 1034–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, M.; Saleem, A.; Hajjaj, M.; Faiz, H.; Pragya, A.; Jamil, R. ; SalimSSS; Lateef, I.K.; Singla, D.; Ramar, R.; Damara, I.; Shahid, L. Sex-specific differences in risk factors, comorbidities, diagnostic challenges, optimal management, and prognostic outcomes of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A comprehensive literature review. Heart Failure Reviews 2024, 29, 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Ji, Y.; Sun, T.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wang, G.; Xing, H.; Yang, B.; Xu, A.; Xian, X.; Yang, H. Management of Chronic Heart Failure in Dialysis Patients: A Challenging but Rewarding Path Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).