Introduction

Firms operating in international markets encounter a myriad of financial exposures, with currency risk being among the most significant. Exchange rate fluctuations can dramatically impact both revenues and costs, affecting the profitability and valuation of firms engaged in cross-border activities. To manage this inherent uncertainty, many firms turn to financial derivatives such as forward contracts, swaps, and options. These tools allow firms to lock in exchange rates or otherwise mitigate the financial impact of currency volatility. Over the past few decades, extensive research has documented that firms actively engaging in hedging activities tend to enjoy a valuation premium, often referred to as the 'hedging premium.' This premium suggests that the market values the reduction in cash flow volatility and the associated lower probability of financial distress.

However, as firms expand their operations internationally and evolve into multinational corporations (MNCs), the dynamics of financial risk management undergo a notable transformation. Multinational firms often develop natural hedging capabilities through their diversified operational footprint—generating revenues and incurring expenses in multiple currencies. Such natural diversification can offset currency fluctuations internally, potentially reducing the marginal benefit of engaging in formal financial hedging strategies. Consequently, it raises a crucial question for scholars and practitioners alike: does financial hedging continue to add value once a firm achieves multinational status?

In a world where globalization trends are shifting—marked by increased protectionism, trade wars, and regional economic blocs—understanding the evolution of the hedging premium is more critical than ever. Firms are navigating a landscape that combines elements of global integration with localized economic uncertainties. Thus, investigating whether hedging retains its value-enhancing properties across different stages of globalization offers vital insights. Financial decision-makers must assess whether traditional derivative-based hedging strategies should be maintained, modified, or replaced by more operationally integrated risk management frameworks as firms expand or contract their global presence. In this context, the study of hedging behavior across the globalization-deglobalization continuum is not merely academic—it has immediate and strategic implications for corporate governance, capital allocation, and long-term value creation.

The relationship between hedging activities and firm value has long been a focus of financial research. Early foundational work by Smith and Stulz (1985) suggested that hedging reduces expected costs associated with financial distress and cash flow volatility, thereby enhancing firm value. Allayannis and Weston (2001) provided empirical support, documenting a positive 'hedging

Premium for firms using foreign currency derivatives.

Later research nuanced these findings. Guay and Kothari (2003) questioned the economic magnitude of hedging benefits, highlighting that after adjusting for firm-specific factors, the effect might be smaller than initially perceived. Jorion (1990) and Pantzalis, Simkins, and Laux (2001) emphasized the importance of natural hedging through operational diversification, particularly for multinational corporations (MNCs), where financial derivatives may play a reduced role.

More recent studies have incorporated the evolving global environment. Bartram, Brown, and Conrad (2011) analyzed a global sample and found that derivative usage is associated with lower total risk and idiosyncratic risk, although the impact on firm value varies depending on corporate governance quality and market structure. Their findings suggest that the effectiveness of hedging

Is context dependent.

Kim, Kim, and Pantzalis (2019) extended prior work by showing that hedging activity is more valuable in firms exposed to political risk and during periods of economic uncertainty. Their work emphasizes the dynamic nature of hedging's value over time and across geopolitical contexts.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, new insights emerged. Wang and Zhou (2022) demonstrated that firms with active hedging programs fared better during the pandemic, preserving firm value more effectively than non-hedgers. They concluded that hedging provides critical downside protection during systemic shocks, offering renewed support for the strategic use of derivatives.

Finally, the contemporary trend toward 'selective globalization'—where firms focus expansion in politically and economically stable regions—has implications for hedging strategies. Cohn, Li, and Wardlaw (2023) recently argued that in a deglobalizing world, firms may return to more active financial hedging practices as operational diversification becomes less effective.

This study thus situates itself within a vibrant and evolving literature, seeking to bridge classical findings on the hedging premium with emerging evidence about how macroeconomic shifts alter the value proposition of corporate hedging strategies.

Methods and Data

2.1. Sample

The study sample consists of 66 non-financial U.S. firms that became multinational between 1999 and 2014. Data were extracted from SEC 10-K filings, Compustat, and annual reports.

Dataset Relevance: Capturing the Globalization Apex

Although the dataset in this study spans the period from 1999 to 2014, it captures what is widely considered the peak era of globalization. During this time, global trade volumes surged, cross-border investment proliferated, and multinational corporate expansion reached unprecedented levels. The World Trade Organization and regional trade agreements such as NAFTA and the EU facilitated a liberalized trade environment, while advancements in technology and communication

Enabled seamless global integration.

This temporal window offers a uniquely valuable lens into how firms responded to globalization's opportunities and risks, particularly in terms of financial exposure and hedging strategies. The decisions made by firms during this period reflect strategic responses to a high-openness economic environment characterized by fluid capital flows, fluctuating exchange rates, and expansive international operations. Therefore, studying hedging behavior during this period provides rich insights into how firms optimized risk management under global interdependence.

In contrast, the current global economic climate is marked by rising protectionism, shifting supply chains, and renewed political scrutiny of cross-border activities. Deglobalization trends have emerged in the wake of the U.S.-China trade tensions, Brexit, and the COVID-19 pandemic, prompting firms to reassess risk exposures and operational footprints. As such, understanding how hedging practices operated during globalization’s apex offers a vital benchmark for financial

Decision makers navigating today’s uncertain international environment.

By capturing the risk management practices of firms during a period of extensive global integration, the dataset not only enhances the empirical validity of the analysis but also provides practical relevance. It helps inform contemporary debates on whether hedging strategies should be adjusted in response to the evolving macroeconomic landscape. In this way, the 1999–2014 data serves not merely as a historical snapshot but as a critical reference point for recalibrating hedging frameworks under contemporary global conditions.

2.2. Variables

Dependent Variable:

Key Independent Variable: Total notional value of foreign exchange derivatives (log-transformed)

Controls:

The Role of Control Variables in Estimating the Hedging–Firm Value Relationship

To accurately isolate the effect of financial hedging on firm value, it is essential to control for other firm-level characteristics that are well-established in the finance literature as drivers of valuation. The following control variables are included in our OLS regression model to improve estimation precision and mitigate omitted variable bias: Return on Assets (ROA), Leverage, Firm Size (log of total assets), and a Dividend dummy. Each of these variables is theoretically grounded and empirically validated in the corporate finance domain.

-

1.

Return on Assets (ROA)

ROA is a direct measure of a firm's profitability, calculated as net income divided by total assets. It reflects the efficiency with which a firm utilizes its assets to generate earnings. More profitable firms tend to have higher valuations because they signal strong operating performance, cash generation capabilities, and management effectiveness. Including ROA in the model helps control for the fact that profitable firms might both hedge more (to protect future cash flows) and be valued more highly by investors. Failure to include ROA could lead to overstating the hedging premium due to a profitability–hedging correlation.

-

2.

Leverage (Debt/Assets)

Leverage captures the firm's capital structure and risk exposure. Highly leveraged firms face greater financial risk and may be more vulnerable to economic downturns or interest rate fluctuations. While some degree of leverage can enhance firm value through tax shields (as posited by Modigliani and Miller with taxes), excessive leverage increases bankruptcy risk and potential agency costs. Additionally, more leveraged firms may hedge more aggressively to reduce the risk of financial distress. By including leverage as a control, we account for the possibility that part of the firm value variation could be driven by debt-related risk and not hedging per se.

-

3.

Firm Size (Log of Total Assets)

Firm size, proxied by the natural logarithm of total assets, is a commonly used variable to control for scale effects and information asymmetries. Larger firms typically have better access to capital markets, more diversified revenue streams, and more sophisticated risk management practices. They may also be more visible to investors, thereby enjoying a valuation premium due to perceived stability and lower monitoring costs. However, size may also correlate with hedging behavior, as larger firms often have the infrastructure and resources to use derivatives extensively. Controlling for size helps isolate the unique effect of hedging on firm value independent of firm scale.

-

4.

Dividend Dummy (1 if dividends paid)

The dividend dummy captures whether a firm paid dividends in the observed year. Dividend-paying firms are often viewed as more mature, stable, and less reliant on reinvestment. They may also signal financial health, reducing information asymmetry between managers and shareholders. The literature suggests that dividend policy can influence firm valuation through both signaling and agency cost mitigation. At the same time, such firms may hedge differently compared to growth-oriented firms that reinvest earnings. Including the dividend dummy controls for these heterogeneities in corporate financial behavior

In summary, these control variables are critical to ensuring the robustness of our regression results. Each represents a fundamental determinant of firm value and allows us to isolate the incremental effect of hedging intensity on Tobin’s Q. Their inclusion strengthens the empirical integrity of our analysis and aligns the study with established methodological standards in corporate finance research.

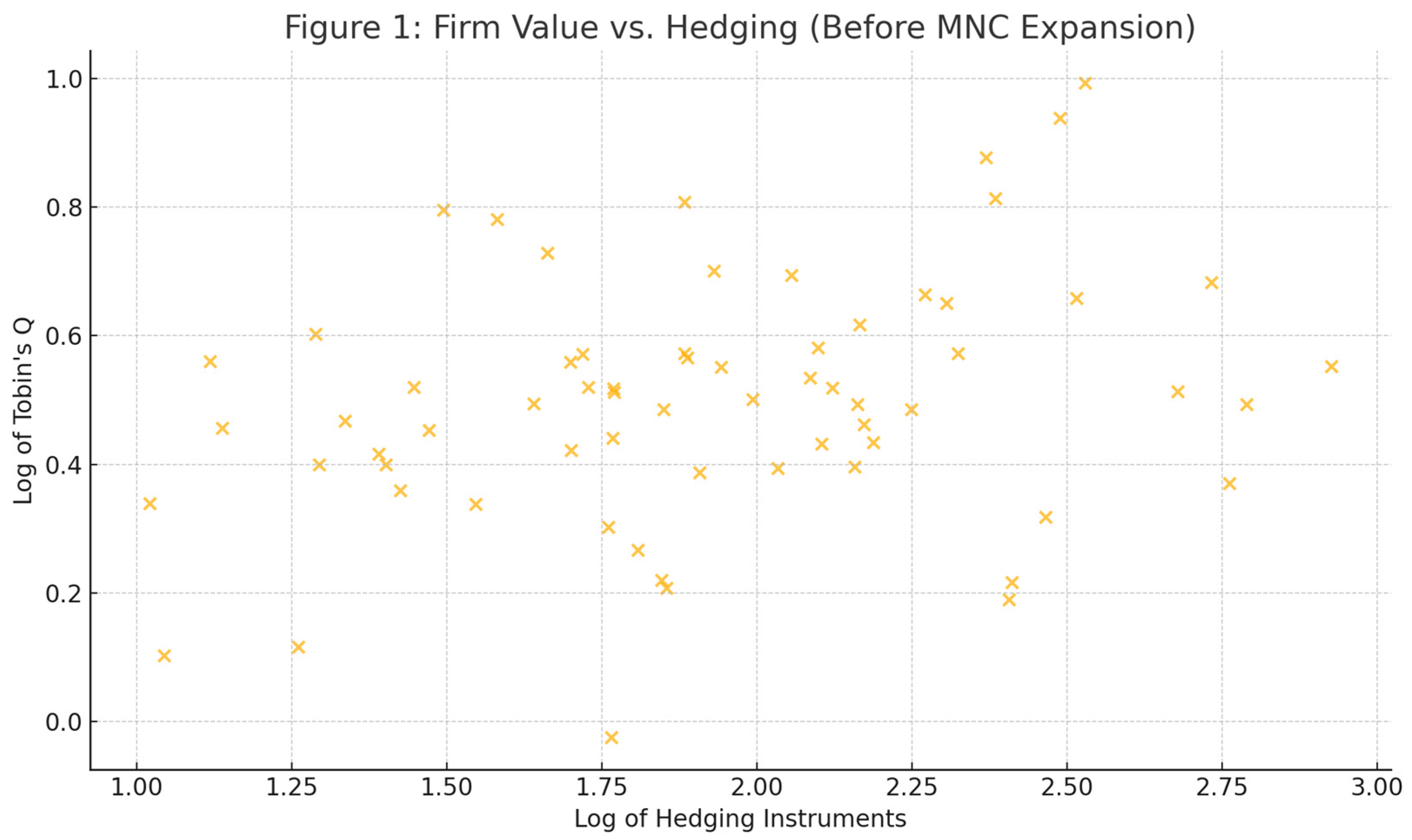

Figure 1.

Firm Value vs. Hedging (Before MNC Expansion). This figure illustrates the positive relationship between hedging intensity (log of hedging instruments) and firm value (log of Tobin’s Q) before firms transitioned into multinational operations. It supports the hypothesis of a hedging premium for non-MNCs and visually aligns with the positive and significant coefficient reported in the regression analysis.

Figure 1.

Firm Value vs. Hedging (Before MNC Expansion). This figure illustrates the positive relationship between hedging intensity (log of hedging instruments) and firm value (log of Tobin’s Q) before firms transitioned into multinational operations. It supports the hypothesis of a hedging premium for non-MNCs and visually aligns with the positive and significant coefficient reported in the regression analysis.

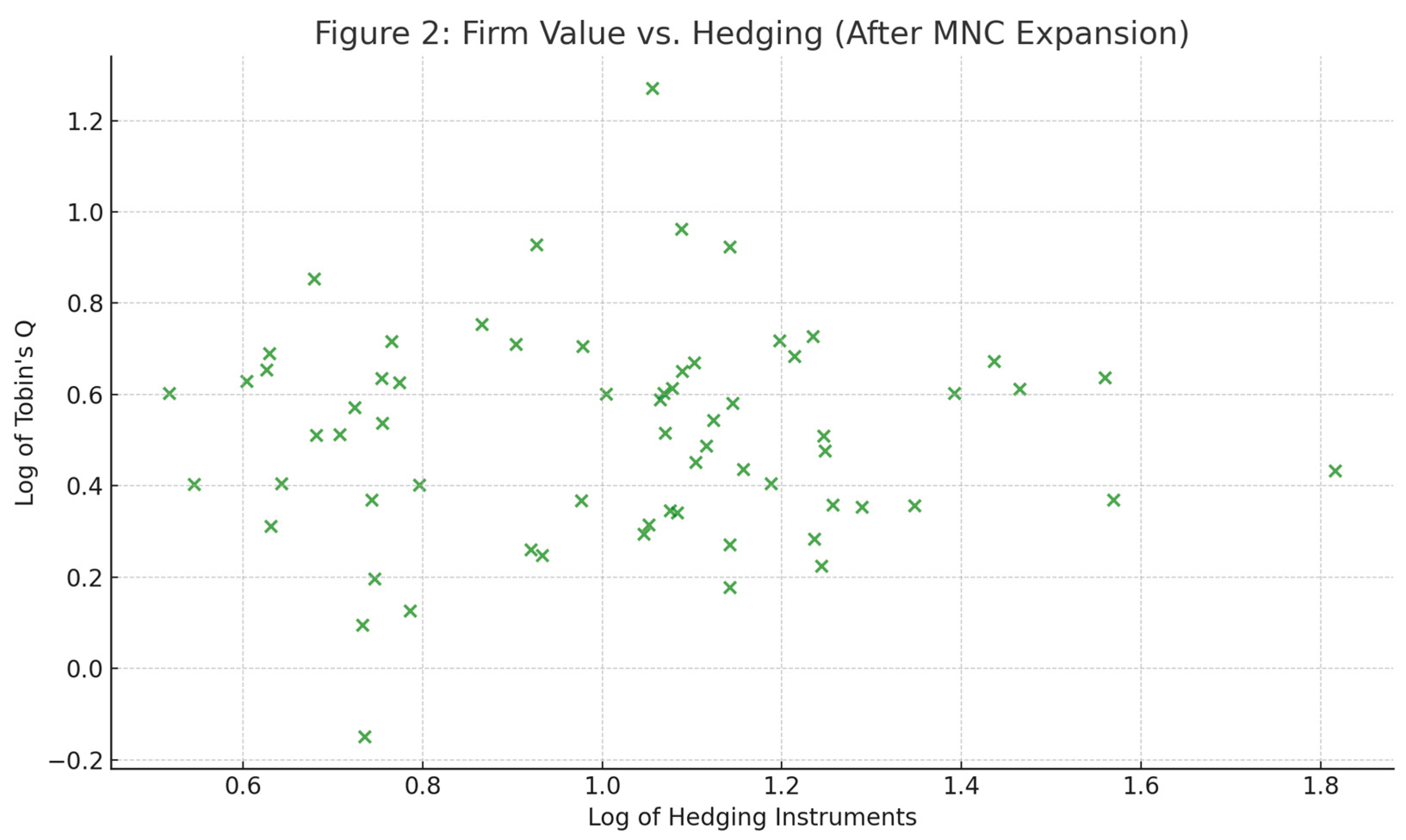

Figure 2.

Firm Value vs. Hedging (After MNC Expansion). This figure demonstrates the absence of a clear relationship between hedging intensity and firm value after multinational expansion. The plot highlights the flattening or disappearance of the hedging premium, in line with regression results showing a non-significant coefficient post-MNC.

Figure 2.

Firm Value vs. Hedging (After MNC Expansion). This figure demonstrates the absence of a clear relationship between hedging intensity and firm value after multinational expansion. The plot highlights the flattening or disappearance of the hedging premium, in line with regression results showing a non-significant coefficient post-MNC.

2.3. Model

To assess the relationship between financial hedging and firm value, we estimate the following ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model for two distinct periods—1999 (pre-internationalization) and 2014 (post-internationalization):

This model specification is widely used in empirical corporate finance to evaluate firm value determinants (e.g., Allayannis & Weston, 2001; Graham & Rogers, 2002). Tobin’s Q serves as a robust proxy for market valuation, while the independent variables reflect key aspects of a firm's financial policy and structure:

Hedge: captures the notional value of foreign exchange derivatives used—our primary variable of interest.

Leverage: controls for capital structure and potential financial distress.

ROA: captures firm profitability, which directly impacts valuation.

Size (Total Assets): accounts for scale economies and information asymmetry.

Dividend: reflects signaling and maturity effects in corporate policy.

By running this model separately for 1999 and 2014, we isolate how the effect of financial hedging changes with multinational expansion. This design allows us to empirically test whether operational hedging (from international diversification) diminishes the marginal value of financial derivatives. The structure also helps control for firm-specific heterogeneity, ensuring the findings are driven by structural shifts rather than unobserved characteristics.

Ultimately, this model forms the backbone of our analysis, enabling a clean identification of the hedging premium and its evolution over time.

3. Regression Results

The analysis confirms a statistically significant hedging premium in 1999, with the Hedge coefficient (2.86e-09) highly significant (p<0.01). This supports the idea that financial derivatives usage is associated with higher firm value in domestic-focused firms.

In 2014, after the firms became multinational, the coefficient on Hedge shrinks to 1.02e-10 and loses significance. This suggests that operational diversification inherent in multinational firms acts as a natural hedge, reducing the incremental value added by financial derivatives.

These results indicate that the effectiveness of financial hedging is context-dependent — more valuable before internationalization and less so afterward. This nuance is critical for corporate finance professionals managing risk in firms at different stages of globalization

Regression Output Tables

Table 1.

Univariate Regression Results - Hedging and Firm Value.

Table 1.

Univariate Regression Results - Hedging and Firm Value.

| Model |

Hedge_log Coefficient |

Standard Error |

Constant |

Obs |

Significance |

| Before MNC |

3.00e-09 |

1.46e-09 |

-0.0994 |

66 |

** |

| After MNC |

-0.0371 |

0.0479 |

0.107 |

66 |

ns |

Table 2.

Multivariate Regression Results (OLS) - Before and After Multinational Expansion.

Table 2.

Multivariate Regression Results (OLS) - Before and After Multinational Expansion.

| Variable |

Before MNC Coef |

SE |

After MNC Coef |

SE |

| Hedge_log |

2.86e-09 |

1.54e-09 |

0.00553 |

0.0240 |

| Leverage_log |

-0.425 |

0.0588 |

-0.409 |

0.0315 |

| ROA_log |

-0.0432 |

0.0252 |

0.00859 |

0.0225 |

| TotalAsset_log |

0.00858 |

0.0130 |

0.0250 |

0.0192 |

| Dividend |

-0.00120 |

0.0716 |

-0.193 |

0.117 |

| Constant |

-0.290 |

0.161 |

-0.217 |

0.241 |

Table 3.

Model Fit Statistics.

Table 3.

Model Fit Statistics.

| Model |

R-squared |

Observations |

| OLS Before MNC |

0.797 |

66 |

| OLS After MNC |

0.808 |

66 |

Discussion

This study contributes to the growing body of literature examining the effectiveness and value implications of corporate hedging strategies. In line with the findings of Allayannis and Weston (2001), the regression results demonstrate a significant positive relationship between hedging activity and firm value prior to multinational expansion. This so-called 'hedging premium' supports the theoretical notion proposed by Smith and Stulz (1985), that firms use derivatives to reduce cash flow volatility, thereby minimizing the likelihood of financial distress and enhancing firm value.

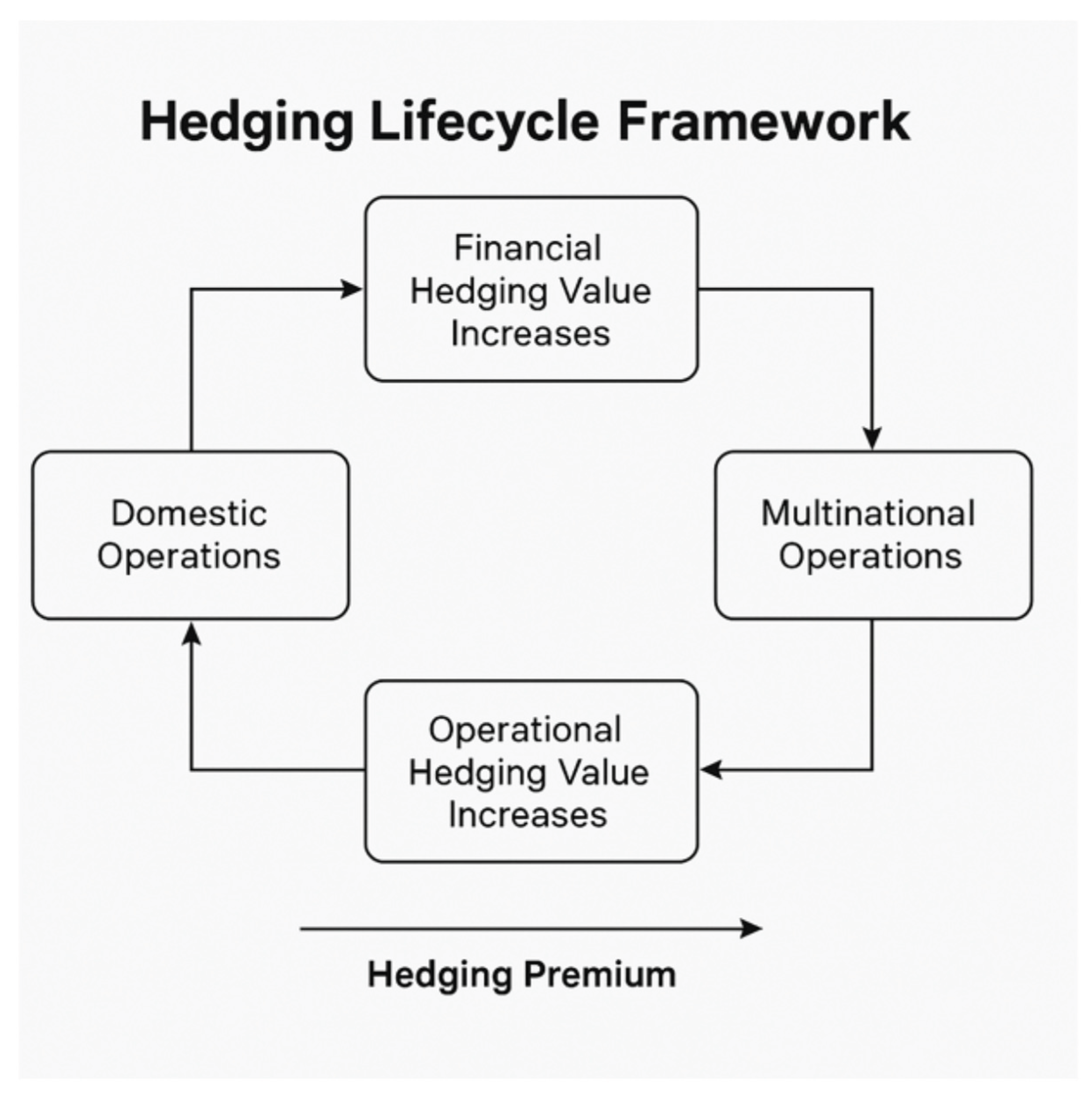

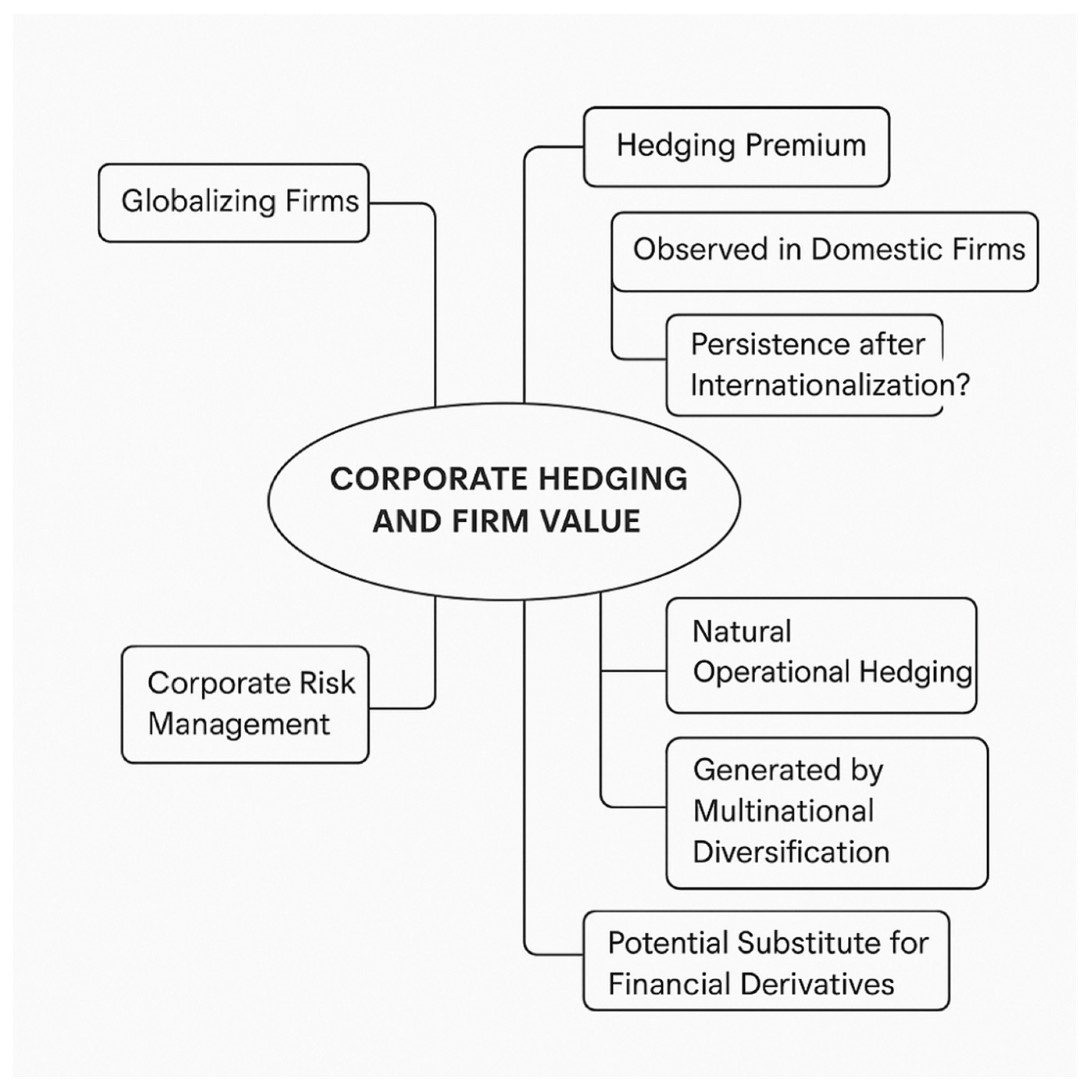

Figure 3.

The Hedging Lifecycle Framework illustrates the evolution of hedging value as firms transition from domestic to multinational operations. Initially, financial hedging provides greater value in domestic settings. As firms expand internationally, operational hedging becomes more effective due to natural currency and revenue-cost matching. The model highlights a cyclical dynamic in which the hedging premium shifts depending on a firm's operational stage and global exposure.

Figure 3.

The Hedging Lifecycle Framework illustrates the evolution of hedging value as firms transition from domestic to multinational operations. Initially, financial hedging provides greater value in domestic settings. As firms expand internationally, operational hedging becomes more effective due to natural currency and revenue-cost matching. The model highlights a cyclical dynamic in which the hedging premium shifts depending on a firm's operational stage and global exposure.

Our findings also echo those of Carter et al. (2006), who reported that firms in volatile industries such as airlines experienced tangible benefits from risk management strategies. In our sample, the premium associated with hedging disappears after the firm becomes multinational, implying that the marginal benefit of financial derivatives declines as operational diversification increases. This aligns with Pantzalis, Simkins, and Laux (2001), who suggest that MNCs develop natural hedging capabilities by matching revenues and costs in local currencies across different geographies.

Interestingly, the post-expansion regression results indicate no statistically significant impact of financial hedging on firm value. This suggests that as firms become more geographically diversified, they may rely less on formal financial hedging. Jorion (1990) found that currency exposure in large multinationals is often negligible due to such diversification effects. Similarly, Guay and Kothari (2003) argued that observed hedging activity may have only modest economic

Implications once firm-specific factors are accounted for.

In the broader context of risk management theory, our findings present a nuanced view. While financial hedging adds value for firms with limited global exposure, its relevance wanes as operational capabilities evolve to mitigate currency risk organically. This has important implications for corporate finance practitioners: rather than adopting a uniform hedging policy, firms should tailor their risk management strategies to their stage of internationalization and the

Nature of their operations.

Additionally, our study is uniquely positioned within a critical historical timeframe. The data set, spanning 1999–2014, captures the apex of globalization—a period characterized by expansive cross-border integration, trade liberalization, and growth in multinational activity. During this period, hedging likely held distinct strategic value as firms navigated emerging risks in volatile global markets. Yet, as globalization matures or even retreats in sectors influenced by protectionism, the landscape of risk management must adapt. Studies like Kim, Kim, and Pantzalis (2019) emphasize that hedging remains valuable in environments rife with political and economic uncertainty.

This perspective is reinforced by recent findings from Wang and Zhou (2022), who demonstrated that firms with structured hedging programs performed better during the COVID-19 pandemic—a modern stress test of global interconnectedness. Although our dataset precedes this event, it offers a benchmark for understanding the evolution of risk strategies in an integrated economy. Cohn, Li, and Wardlaw (2023) suggest that deglobalization might renew the relevance of formal hedging, as

Firms lose access to natural operational offsets.

Ultimately, this study suggests a lifecycle framework for hedging: it is most valuable during the early stages of international expansion and in unpredictable economic climates. Once a firm becomes fully multinational, natural hedging may reduce the necessity for financial derivatives—unless renewed volatility or geopolitical shifts reintroduce asymmetrical risks. For financial managers, this highlights the importance of regularly reassessing risk exposures and aligning hedging strategies with evolving global realities.

Conclusion

This study provides empirical evidence on the evolving role of financial hedging in enhancing firm value, with particular attention to the firm's multinational status. By analyzing a carefully constructed panel of 66 firms before and after their expansion into multinational operations, the results demonstrate a statistically significant hedging premium in the pre-expansion phase. This finding aligns with the theoretical expectation that financial hedging mitigates exposure to exchange rate volatility and reduces expected costs of financial distress, ultimately enhancing firm valuation.

However, the study also reveals that this hedging premium dissipates following a firm’s transition into multinational status. The absence of a significant relationship between hedging and firm value in the post-expansion period suggests that operational diversification may provide natural hedging mechanisms, reducing the marginal benefit of derivative use. This lifecycle dynamic implies that financial hedging strategies are not universally valuable across all stages of corporate growth, but instead, their effectiveness is context-dependent and evolves alongside the firm's international footprint.

These insights are especially relevant within the broader context of globalization and emerging protectionist trends. The data period (1999–2014) captures globalization’s zenith, allowing the study to serve as a benchmark for firms navigating an increasingly complex and fragmented global environment. As firms reassess their risk management frameworks considering geopolitical instability and shifting supply chains, the ability to draw lessons from periods of expansive global

Integration remains critical.

Ultimately, this study underscores the need for adaptive hedging policies that respond to both firm-specific attributes and macroeconomic conditions. Financial managers should carefully evaluate when and how hedging contributes to firm value, particularly as the effectiveness of risk mitigation strategies can shift with operational scale and global economic dynamics. Future research may extend this analysis by incorporating more recent data, sector-specific volatility, or the impact of ESG-driven risk exposure on hedging decisions

Policy Recommendations

This study’s findings—that financial hedging enhances firm value primarily before multinational expansion but offers diminishing returns afterward—have important implications for corporate finance and risk management. Drawing on both empirical insights and supporting literature, the following policy recommendations are proposed for firms, especially those operating in or transitioning toward international markets:

Firms should customize hedging strategies based on their internationalization stage. For domestic firms, the evidence strongly supports active engagement in financial derivatives to manage exchange rate volatility and enhance firm value (Allayannis & Weston, 2001; Smith & Stulz, 1985). In contrast, multinational firms can rely more on natural hedging through operational diversification (Pantzalis et al., 2001; Jorion, 1990). Risk managers should regularly reassess the value-add of derivatives relative to internal hedging capacity.

Policy Action: Firms should institutionalize a dynamic risk management review process that evaluates the balance between financial and operational hedging on a periodic basis.

- 2.

Integrate Operational and Financial Hedging Frameworks

Rather than treating financial and operational hedging as substitutes, firms should develop integrated risk dashboards that track exposure across both dimensions. As noted by Bartram, Brown, & Conrad (2011), the effectiveness of hedging is context-dependent, and a blended model may offer better resilience, especially in politically or economically volatile regions (Kim et al., 2019).

Policy Action: Implement cross-functional teams (finance, operations, and treasury) to co-develop hedging strategies aligned with firm-specific exposure profiles and geopolitical realities.

- 3.

Reevaluate Hedging Post-Deglobalization

As global economic integration retreats—evident in trends like U.S.–China decoupling and Brexit—multinational firms may lose the natural hedging advantage. This may reintroduce the need for active derivative use. Cohn, Li, & Wardlaw (2023) argue that deglobalization renews the relevance of financial hedging.

Policy Action: Firms should establish scenario-based contingency hedging plans that can be activated during periods of macroeconomic fragmentation or supply chain regionalization.

- 4.

Enhance Risk Governance and Reporting

Effective governance frameworks enhance the value of hedging, particularly in firms with strong transparency and internal controls (Graham & Rogers, 2002). With the growing scrutiny from stakeholders and ESG frameworks, firms should enhance the disclosure of risk policies and hedging outcomes, especially during transition phases.

Policy Action: Include detailed disclosures of hedging policy rationales, risk metrics, and their alignment with overall corporate strategy in annual financial statements and ESG reports.

- 5.

Hedge Selectively Based on Firm and Industry Risk

Sector-specific factors and firm size moderate hedging effectiveness (Guay & Kothari, 2003; Jin & Jorion, 2006). For example, industries like airlines, oil and gas, and commodities are more vulnerable to external shocks. The COVID-19 pandemic reaffirmed the critical value of hedging during systemic crises (Wang & Zhou, 2022).

Policy Action: Use a risk-adjusted approach to hedging, prioritizing firms in high-volatility sectors or those with limited internal hedging capacity.

- 6.

Leverage Advanced Analytics in Hedging Decisions

With data availability increasing, firms should adopt quantitative modeling tools to simulate hedging impacts on firm value under different internationalization stages and macroeconomic conditions.

Policy Action: Develop in-house or outsourced analytical capabilities to run cost-benefit analyses of hedging strategies under different operating environments.

The effectiveness of hedging is not uniform; it evolves with a firm’s scale, structure, and geopolitical context. Risk policies must reflect this dynamic nature. Financial managers and boards should embed flexibility and foresight into hedging frameworks to preserve firm value across the globalization-deglobalization continuum.

Appendix A: Variable Definitions and Measurement

- •

Tobin’s Q (Q_log): Proxy for firm value, calculated as (Book Value of Total Assets - Book Value of Equity + Market Value of Equity) / Book Value of Total Assets. The natural logarithm is taken for analysis.

- •

Hedge log: Natural logarithm of total hedging instruments reported in the 10-K filings, including currency forwards, swaps, and options.

- •

ROA_log: Return on Assets, calculated as Net Income divided by Total Assets, expressed in natural logarithm.

- •

Leverage_log: Natural logarithm of book value of debt divided by market value of common equity.

- •

Total Asset log: Natural logarithm of Total Assets.

- •

Dividend: Dummy variable equal to 1 if the firm paid dividends in the given year, 0 otherwise.

Appendix B: Descriptive Statistics (Before and After Multinational Expansion)

Table B1.

presents descriptive statistics of firm-level variables used in the analysis, before and after intensification of multinational operations.

Table B1.

presents descriptive statistics of firm-level variables used in the analysis, before and after intensification of multinational operations.

| Variable |

N |

Mean (Before) |

SD (Before) |

Mean (After) |

SD (After) |

| Hedge |

66 |

2.03e+07 |

7.61e+07 |

96,355 |

676,620 |

| Total Asset |

66 |

1.96e+08 |

8.97e+08 |

1.87e+06 |

6.29e+06 |

| Debt |

66 |

4.05e+07 |

1.60e+08 |

618,878 |

1.89e+06 |

| Net Income |

66 |

7.66e+07 |

3.18e+08 |

213,022 |

715,225 |

| ROA |

66 |

5,567 |

43,750 |

0.433 |

1.098 |

| Leverage |

66 |

2.45 |

5.92 |

9.30 |

31.07 |

| Q |

66 |

1.99 |

5.79 |

0.864 |

4.53 |

| Dividend |

66 |

0.754 |

0.434 |

0.803 |

0.401 |

Appendix C: Regression Model Specifications

Appendix D: Diagnostic Tests and Robustness Checks

Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) were calculated to check for multicollinearity. The mean VIFs were 1.32 (before) and 1.26 (after), indicating no significant multicollinearity issues.

Cameron and Trivedi's decomposition of the IM-test showed evidence of heteroskedasticity (p < 0.01),

Suggesting roubust standard errors were used.

Residual plots, kernel density estimates, and normal probability plots confirmed acceptable distributional assumptions for OLS residuals.

Figures and Captions for Final Paper

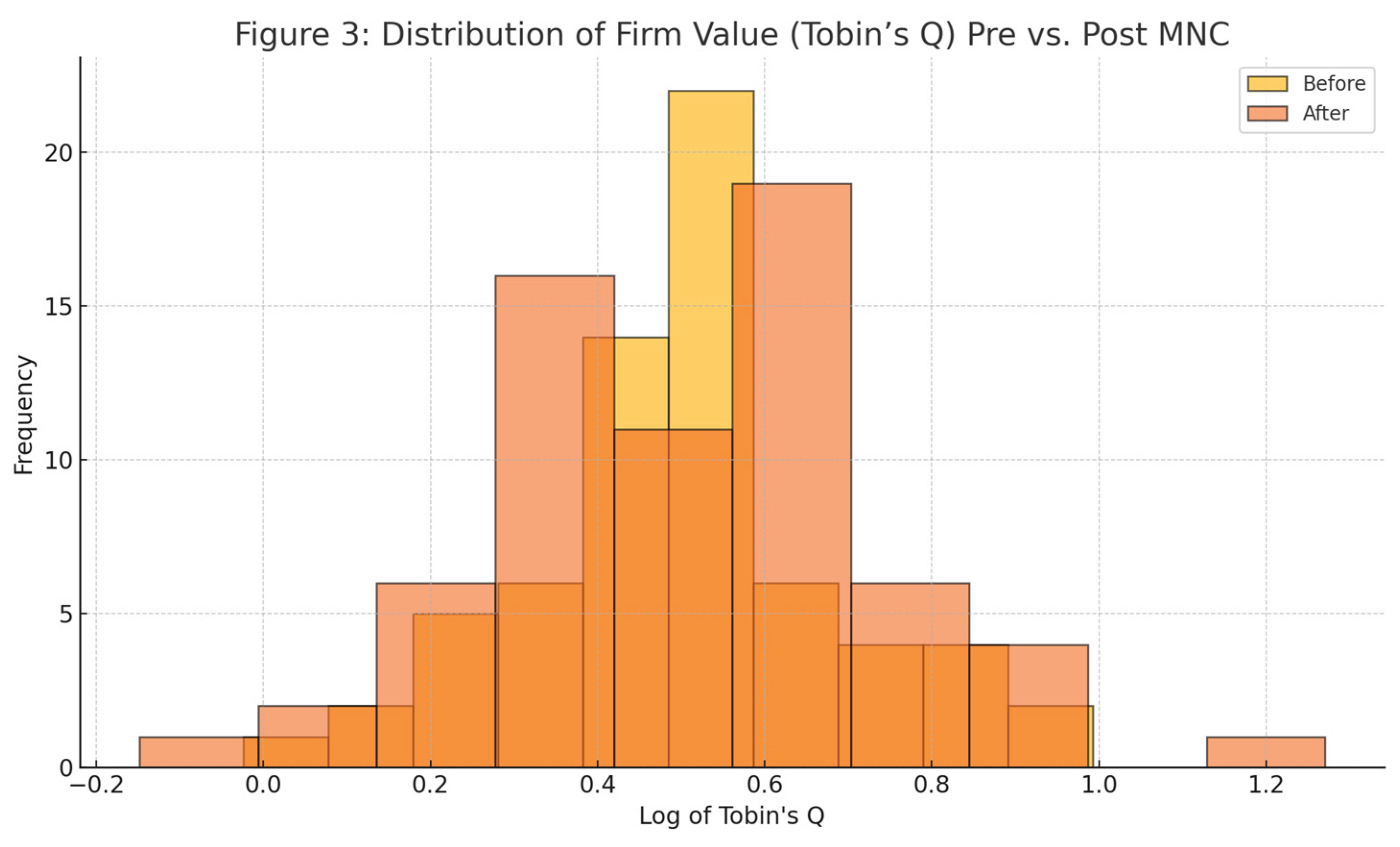

Figure 3.

Distribution of Firm Value (Tobin’s Q) Pre vs. Post MNC. The histogram compares the distribution of Tobin’s Q before and after multinational expansion. The figure illustrates the variability in firm value over time and supports the descriptive analysis discussed in the results section. This figure is best referenced in either the Descriptive Statistics or Appendix section.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Firm Value (Tobin’s Q) Pre vs. Post MNC. The histogram compares the distribution of Tobin’s Q before and after multinational expansion. The figure illustrates the variability in firm value over time and supports the descriptive analysis discussed in the results section. This figure is best referenced in either the Descriptive Statistics or Appendix section.

References

- Adler, M., & Dumas, B. (1984). Exposure to currency risk: Definition and measurement. Financial Management, 13, 41–50. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S., & Oliver, B. (2009). Determinants of capital structure for Japanese multinational and domestic corporations. International Review of Finance, 9(1-2), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Allayannis, G., & Ofek, E. (2001). Exchange rate exposure, hedging, and the use of foreign currency derivatives. Journal of International Money and Finance, 20(2), 273–296. [CrossRef]

- Allayannis, G., & Weston, J. P. (2001). The use of foreign currency derivatives and firm market value. Review of Financial Studies, 14(1), 243–276. [CrossRef]

- Altman, E. (1983). Corporate financial distress. New York, NY: John Wiley.

- Bartram, S. M., Brown, G. W., & Conrad, J. (2011). The effects of derivatives on firm risk and value. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 46(4), 967–999. [CrossRef]

- Bartram, S. M., Brown, G. W., & Fehle, F. (2009). International evidence on financial derivatives usage. Financial Management, 38(1), 185–206. [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. W. (2001). Managing foreign exchange risk with derivatives. Journal of Financial Economics. [CrossRef]

- Carter, D. A., Rogers, D. A., & Simkins, B. J. (2006). Does hedging affect firm value? Evidence from the US airline industry. Financial Management, 35(1), 53–87. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J., Li, T., & Wardlaw, M. (2023). Deglobalization and corporate risk management. Journal of Financial Economics.

- Froot, K. A., Scharfstein, D. S., & Stein, J. C. (1993). Risk management: Coordinating corporate investment and financing policies. Journal of Finance, 48(5), 1629–1658.

- Géczy, C., Minton, B. A., & Schrand, C. (1997). Why firms use currency derivatives. Journal of Finance, 52(4), 1323–1354.

- Graham, J. R., & Rogers, D. A. (2002). Is corporate hedging consistent with value maximization? An empirical analysis. Journal of Finance, 57(2), 815–844.

- Guay, W. R. (1999). The impact of derivatives on firm risk: An empirical examination of new derivatives users. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 26(1-3), 319–351. [CrossRef]

- Guay, W. R., & Kothari, S. P. (2003). How much do firms hedge with derivatives? Journal of Financial Economics, 70(3), 423–461. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., & Jorion, P. (2006). Firm value and hedging: Evidence from U.S. oil and gas producers. Journal of Finance, 61(2), 893–919. [CrossRef]

- Jorion, P. (1990). The exchange-rate exposure of U.S. multinationals. Journal of Business, 63(3), 331–345. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. S., Kim, H., & Pantzalis, C. (2019). Corporate hedging, political risk, and firm value. Journal of Financial Research, 42(3), 461–494.

- Lee, K. C., & Kwok, C. Y. (1988). Multinational corporations vs. domestic corporations: International environmental factors and determinants of capital structure. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(4), 41–58. [CrossRef]

- Mian, S. L. (1996). Evidence on corporate hedging policy. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 31(3), 419–439. [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, F., & Miller, M. H. (1958). The cost of capital, corporation finance, and the theory of investment. American Economic Review, 48(3), 261–297.

- Nance, D. R., Smith, C. W., Jr., & Smithson, C. W. (1993). On the determinants of corporate hedging. Journal of Finance, 48(1), 267–284.

- Pantzalis, C., Simkins, B., & Laux, P. (2001). Operational hedges and the foreign exchange exposure of U.S. multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(4), 793–812. [CrossRef]

- Schrand, C., & Unal, H. (1998). Hedging and coordinated risk management: Evidence from thrift conversions. Journal of Finance, 53(3), 979–1015. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. W., Jr., & Stulz, R. M. (1985). The determinants of firms’ hedging policies. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 20(4), 391–405. [CrossRef]

- Stulz, R. M. (1984). Optimal hedging policies. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 19(2), 127–140. [CrossRef]

- Tufano, P. (1996). Who manages risk? An empirical examination of risk management practices in the gold mining industry. Journal of Finance, 51(4), 1097–1137.

- Wang, Y., & Zhou, H. (2022). Hedging and firm value during systemic crises: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Corporate Finance.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).