Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

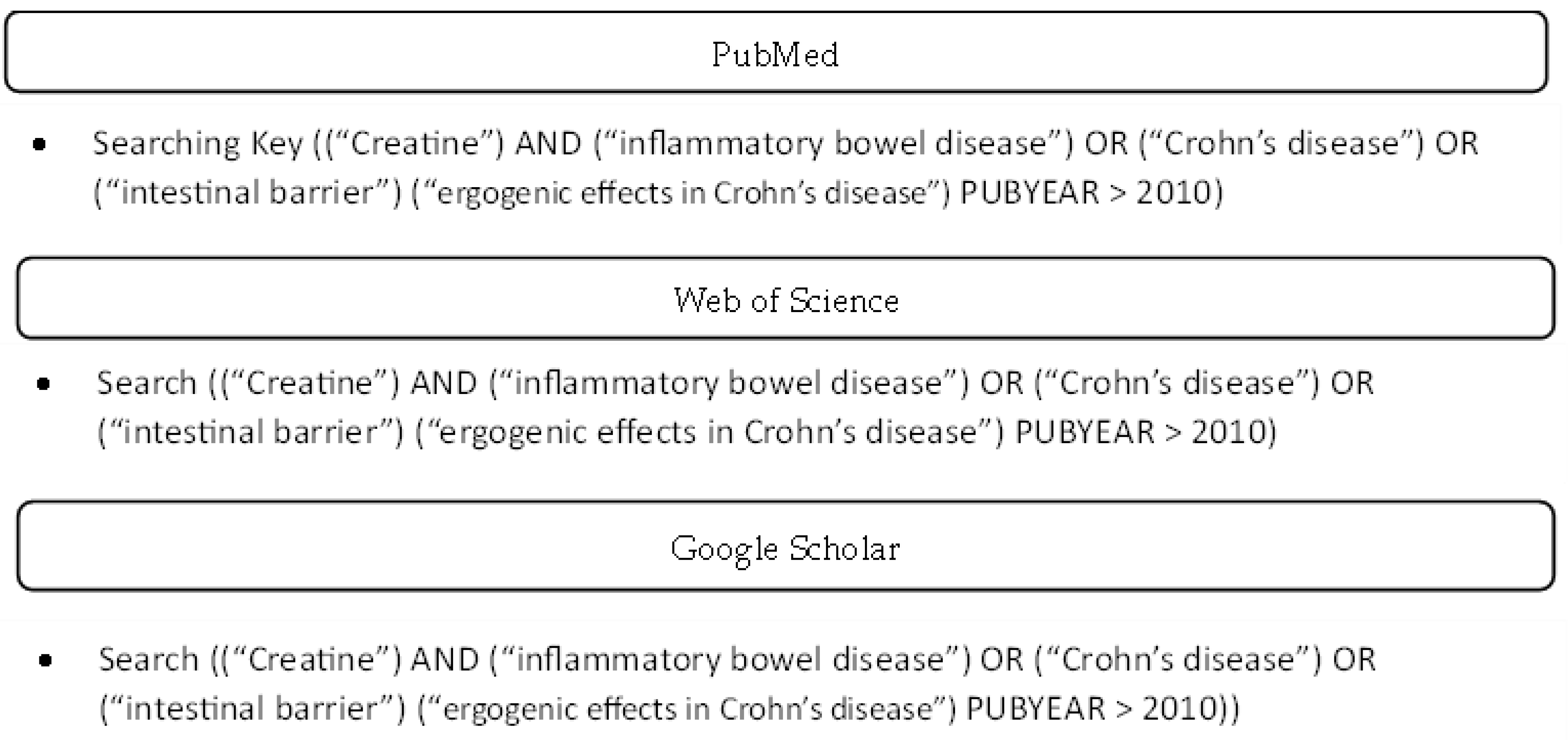

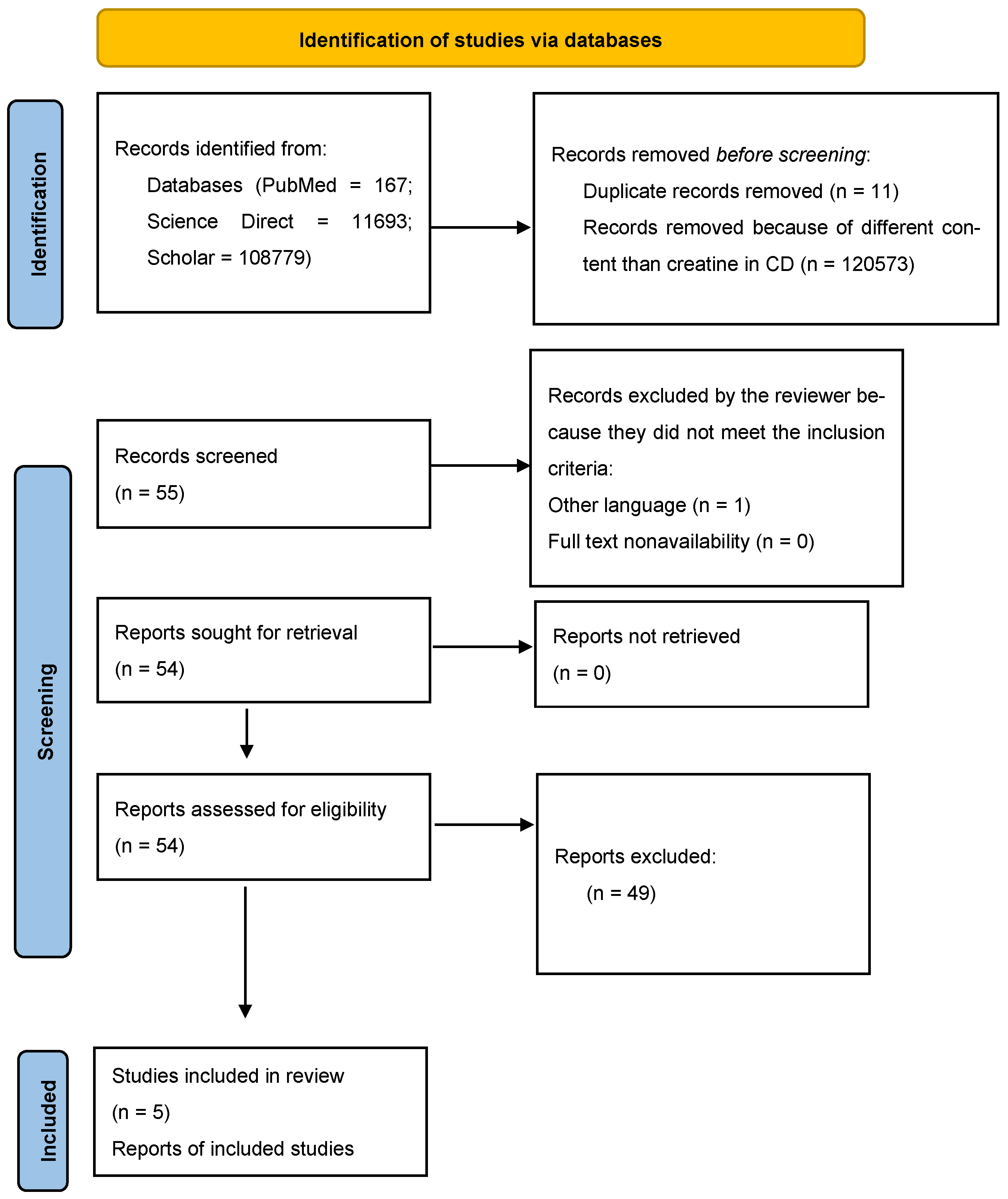

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Null Hypothesis

4.2. The Research Hypothesis

4.3. How Can We Begin the Research Journey of Creatine Contribution?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cr | Creatine |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| ATP | triphosphoric adenosine |

| ADP | diphosphoric adenosine |

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

| StO2 | Oxygen saturation |

| Gatm | Glycine aminotransferase |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| Cr-HCL | Creatine hydrochloride |

| Cr-M | Creatine monohydrate |

| PCr | phosphocreatine |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| HIF | hypoxia-inducible transcription factors |

| CK | creatine kinase |

| CrT1 | creatine transporter |

| SLC6A8 | solute carrier family 6 member 8 |

Appendix A

References

- Jäger, R.; Purpura, M.; Shao, A.; Inoue, T.; Kreider, R.B. Analysis of the Efficacy, Safety, and Regulatory Status of Novel Forms of Creatine. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreider, R.B.; Jäger, R.; Purpura, M. Bioavailability, Efficacy, Safety, and Regulatory Status of Creatine and Related Compounds: A Critical Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parise, G.; Mihic, S.; MacLennan, D.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Effects of Acute Creatine Monohydrate Supplementation on Leucine Kinetics and Mixed-Muscle Protein Synthesis. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 91, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruchalla, E. Nahrungsergänzungsmittel im Sport – Kreatinsupplementation Erhöht den Wassergehalt im Körper. Sportverletz. Sportschaden 2016, 30, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellery, S.J.; Murthi, P.; Gatta, P.A.D.; May, A.K.; Davies-Tuck, M.; Kowalski, G.M.; Callahan, D.L.; Bruce, C.R.; Wallace, E.M.; Walker, D.W.; et al. The Effects of Early-Onset Pre-Eclampsia on Placental Creatine Metabolism in the Third Trimester. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Landa, J.; Calleja-González, J.; León-Guereño, P.; Caballero-García, A.; Córdova, A.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J. Effect of the Combination of Creatine Monohydrate Plus HMB Supplementation on Sports Performance, Body Composition, Markers of Muscle Damage and Hormone Status: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, K.L.; Thomson, J.; Swift, R.J.; von Hurst, P.R. Role of Nutrition in Performance Enhancement and Postexercise Recovery. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2015, 6, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.C.; Candow, D.G.; Neto, J.H.F.; Kennedy, M.D.; Forbes, J.L.; Machado, M.; Bustillo, E.; Gomez-Lopez, J.; Zapata, A.; Antonio, J. Creatine Supplementation and Endurance Performance: Surges and Sprints to Win the Race. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2023, 20, 2204071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Trojian, T.H. Creatine Supplementation. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2013, 12, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, R.B.; Jagim, A.R.; Antonio, J.; Kalman, D.S.; Kerksick, C.M.; Stout, J.R.; Wildman, R.; Collins, R.; Bonilla, D.A. Creatine Supplementation Is Safe, Beneficial throughout the Lifespan, and Should Not Be Restricted. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1578564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Loon, L.J.C.; Oosterlaar, A.M.; Hartgens, F.; Hesselink, M.K.C.; Snow, R.J.; Wagenmakers, A.J.M. Effects of creatine loading and prolonged creatine supplementation on body composition, fuel selection, sprint and endurance performance in humans. Clin. Sci. 2003, 104, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francaux, M.; Poortmans, J. Effects of training and creatine supplement on muscle strength and body mass. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1999, 80, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, R.B.; Stout, J.R. Creatine in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsowith, E.J.; Stock, M.S.; Kocuba, O.; Schumpp, A.; Jackson, K.; Brooks, A.M.; Larson, A.; Dixon, M.; Fairman, C.M. Impact of short-term creatine supplementation on muscular performance among breast cancer survivors. Nutrients 2024, 16, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingues, W.J.R.; Ritti-Dias, R.M.; Cucato, G.G.; Wolosker, N.; Zerati, A.E.; Puech-Leão, P.; Coelho, D.B.; Nunhes, P.M.; Moliterno, A.A.; Avelar, A. Effect of creatine supplementation on functional capacity and muscle oxygen saturation in patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease: A pilot study of a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, K.; Kokotilo, M.S.; Carter, J.M.; Thiesen, A.; Madsen, K.L.; Studzinski, J.; Khadaroo, R.G.; Churchill, T.A. Creatine-loading preserves intestinal barrier function during organ preservation. Cryobiology 2018, 84, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turer, E.; McAlpine, W.; Wang, K.W.; Lu, T.; Li, X.; Tang, M.; Zhan, X.; Wang, T.; Zhan, X.; Bu, C.H.; Murray, A.R.; Beutler, B. Creatine maintains intestinal homeostasis and protects against colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E1273–E1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.H.T.; Lee, J.S.; Murphy, E.M.; Gerich, M.E.; Dran, R.; Glover, L.E.; Abdulla, Z.I.; Skelton, M.R.; Colgan, S.P. Creatine transporter, reduced in colon tissues from patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, regulates energy balance in intestinal epithelial cells, epithelial integrity, and barrier function. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 984–998e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, M.; Dias, C.C.; Alves, C.; Ministro, P.; Gonçalves, R.; Carvalho, D.; Portela, F.; Correia, L.; Lago, P.; Magro, F. The Magnitude of Crohn’s Disease Direct Costs in Health Care Systems (from Different Perspectives): A Systematic Review. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.T. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2652–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burisch, J.; Zhao, M.; Odes, S.; De Cruz, P.; Vermeire, S.; Bernstein, C.N.; Kaplan, G.G.; Duricova, D.; Greenberg, D.; Melberg, H.O.; et al. The cost of inflammatory bowel disease in high-income settings: A Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology Commission. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 458–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppertz-Hauss, G.; Høivik, M.L.; Langholz, E.; Odes, S.; Småstuen, M.; Stockbrugger, R.; Hoff, G.; Moum, B.; Bernklev, T. Health-Related Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a European-Wide Population-Based Cohort 10 Years after Diagnosis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, A.; Escher, J.; Hébuterne, X.; Kłęk, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Schneider, S.; Shamir, R.; Stardelova, K.; Wierdsma, N.; Wiskin, A.E.; et al. ESPEN Guideline: Clinical Nutrition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, B.; Mrowiec, S. Nutritional Status and Its Detection in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrieri, P.; Ribolsi, M.; Guarino, M.P.L.; Emerenziani, S.; Altomare, A.; Cicala, M. Nutritional Aspects in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcil, V.; Levy, E.; Amre, D.; Bitton, A.; Sant’Anna, A.M.G.A.; Szilagy, A.; Sinnett, D.; Seidman, E.G. A Cross-Sectional Study on Malnutrition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Is There a Difference Based on Pediatric or Adult Age Grouping? Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2020, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Lee, D. Dietary Creatine as a Possible Novel Treatment for Crohn’s Ileitis. ACG Case Rep. J. 2016, 3, e173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreider, R.B.; Jäger, R.; Purpura, M. Bioavailability, Efficacy, Safety, and Regulatory Status of Creatine and Related Compounds: A Critical Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, K.; Deligiannidou, G.-E.; Voulgaridou, G.; Giaginis, C.; Papadopoulou, S.K. Nutritional Habits in Crohn’s Disease Onset and Management. Nutrients 2025, 17, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, K. The Influence of Aerobic Type Exercise on Active Crohn’s Disease Patients: The Incidence of an Elite Athlete. Healthcare 2022, 10, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkikas, K.; Svolos, V.; Hansen, R.; Russell, R.K.; Gerasimidis, K. Take-Home Messages from 20 Years of Progress in Dietary Therapy of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 79, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadimitriou, K. Effect of Resistance Exercise Training on Crohn’s Disease Patients. Intest. Res. 2021, 19, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirstensen, C.A.; Askenasy, N.; Jain, R.K.; Koretsky, A.P. Creatine and Cyclocreatine Treatment of Human Colon Adenocarcinoma Xenografts: 31P and 1H Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Studies. Br. J. Cancer 1999, 79, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, M.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Creatine and Creatinine Metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 1107–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, L. Creatine in T Cell Antitumor Immunity and Cancer Immunotherapy. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, C.; Cho, J.H. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 2066–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, R.M.M.; Li, E.; Fishman, L.N. Impact of Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Diagnosis on Exercise and Sports Participation: Patient and Parent Perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 4493–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, K.; Detopoulou, P.; Soufleris, K.; Voulgaridou, G.; Tsoumana, D.; Ntopromireskou, P.; Giaginis, C.; Chatziprodromidou, I.P.; Spanoudaki, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K. Nutritional Risk and Sarcopenia Features in Patients with Crohn’s Disease: Relation to Body Composition, Physical Performance, Nutritional Questionnaires, and Biomarkers. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, L.E.; Bowers, B.E.; Saeedi, B.; Ehrentraut, S.F.; Campbell, E.L.; Bayless, A.J.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Kendrick, A.A.; Kelly, C.J.; Burgess, A.; Miller, L.; Kominsky, D.J.; Jedlicka, P.; Colgan, S.P. Control of Creatine Metabolism by HIF is an Endogenous Mechanism of Barrier Regulation in Colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19820–19825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, L.E.; Colgan, S.P. Epithelial Barrier Regulation by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14, S233–S236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Wang, R.X.; Alexeev, E.E.; Colgan, S.P. Intestinal Inflammation as a Dysbiosis of Energy Procurement: New Insights into an Old Topic. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, J.; Candow, D.G.; Forbes, S.C.; et al. Common Questions and Misconceptions about Creatine Supplementation: What Does the Scientific Evidence Really Show? J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, G.; Gonzalez, A.M.; St Mart, D.; Torres, M.; Echols, J.; Islas, M.; Schoenfeld, B.J. Analysis of the efficacy, safety, and cost of alternative forms of creatine available for purchase on Amazon.com: Are label claims supported by science? Heliyon 2022, 8, e12113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, M.E.; Brosnan, J.T. The Role of Dietary Creatine. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallimann, T.; Hall, C.H.T.; Colgan, S.P.; Glover, L.E. Creatine supplementation for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: A scientific rationale for a clinical trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crohn, B.B.; Ginzburg, L.; Oppenheimer, G.D. Regional ileitis; a pathologic and clinical entity. Am. J. Med. 1952, 13, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, C.J. Nutritional Supplements for Endurance Athletes. In Nutritional Supplements in Sports and Exercise; Humana Press, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, N.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, C.; Dan, H. Association between nutrient intake and inflammatory bowel disease risk: Insights from NHANES data and dose-response analysis. Nutrition 2025, 131, 112632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, E.; Artioli, G.G.; Pereira, R.M.R.; Gualano, B. Muscular atrophy and sarcopenia in the elderly: Is there a role for creatine supplementation? Biomolecules 2019, 9, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candow, D.G.; Forbes, S.C.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Cornish, S.M.; Antonio, J.; Kreider, R.B. Effectiveness of creatine supplementation on aging muscle and bone: Focus on falls prevention and inflammation. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Foods | Creatine Content (g· kg−1 mass) |

|---|---|

| Rice | ≈ 0.32 |

| Potatoes | ≈ 0.18 |

| Salmon | ≈ 4.5 |

| Chicken | ≈ 0.8 |

| Meat (Beef, pork) | ≈ 4.5-5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).