1. Introduction

Pressure ulcers (PUs) are a significant challenge for health systems, extending beyond the immediate concerns of wound management, and include broader patient safety issues [

1]. PUs are injuries to the skin and underlying tissues and result from long mechanical loading, typically over bony prominences such as the sacrum, heels, and hips. PUs are more frequent in patients with limited mobility. The etiology of PUs includes patient factors such as comorbidities, age-related tissue fragility, and nutritional deficiencies, as well as external factors such as mechanical forces, medical devices, and hospital care environment characteristics [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. While largely preventable, PUs occur frequently in healthcare settings, showing prevention practice inefficiencies and the need for effective monitoring and quality improvement. The occurrence of PUs is therefore both a clinical concern and a quality-of-care indicator, emphasizing the responsibility of health providers to prevent injury and to mitigate adverse outcomes [

1,

2].

The prevalence of PUs varies across healthcare settings. Intensive care units (ICUs), long-term care acute settings, and nursing homes have higher PU incidence rates, likely due to patient acuity, hospital care practices, and issues with staffing, lack of educational initiatives or prevention protocols [

2,

3]. Older age is a significant risk factor, because of age-related skin changes, tissue integrity, reduced mobility, and the higher prevalence of comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes [

3,

4]. Among younger populations those mostly affected are patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation, or extensive surgical interventions [

3,

6]. This variation in PU prevalence emphasized the need to map the frequency, anatomical site, and stage of PUs in hospitalized patients to understand risk stratification and resource allocation.

The pathophysiology of PUs involves an interplay of mechanical, cellular, and systemic factors. Prolonged pressure over bony prominences impairs tissue perfusion, leading to hypoxia, metabolic dysfunction, and ultimately cellular necrosis [

4]. This is the reason patients with conditions such as compromised cardiovascular function, and diabetes are particularly vulnerable [

4,

5]. Comorbidities often require prolonged immobilization and sometimes medications that can slow tissue repair [

5]. In addition, hospital environmental factors play a critical role. Patients in critical care settings experience extended immobility, sedation, and exposure to medical devices such as mechanical ventilators, catheters, and vascular access devices, all of which can contribute to tissue damage and delayed healing [

6,

7,

8]. Staffing adequacy, nursing education, and institutional culture also influence PU outcomes, with insufficient knowledge of prevention protocols or lack of systematic risk assessment contributing to higher incidence rates [

9,

15].

Evidence-based strategies for PU prevention include evidence-driven risk assessment, targeted interventions, and continuous monitoring. Validated instruments such as the Braden Scale and Norton Scale are available to measures the risk and facilitate early identification of high-risk patients and the focus of preventive resources to specific anatomical sites [

10,

11]. Repositioning protocols and the use of pressure-relieving surfaces reduce mechanical loading and forces, lowering the likelihood of tissue injury [

12,

13,

14]. Positioning techniques (e.g., 30-degree lateral rotation method) can be particularly effective in reducing pressure over bony prominences [

14]. Nutritional status further influences PU risk by affecting tissue repair, immune function, and overall skin integrity. Malnutrition also increases susceptibility to PUs and this emphasizes the need for nutritional assessment as part of PU prevention programs [

17].

Health provider education is important in PU prevention efforts. Educational interventions have been shown to improve knowledge, attitudes about patient safety, which in turn contribute to safer clinical practices related to PU prevention [

15,

16]. Training programs must prioritize professional development, documentation, and quality monitoring for adherence to evidence-based protocols. Quality monitoring includes process measures (e.g., completion rates of risk assessments, preventive interventions), and outcome measures (e.g., PU incidence, stage, and severity) as well [

18,

19,

20].

The clinical consequences of PUs extend beyond local tissue injury, affecting patient quality of life, functional status, and mental health. Patients report pain, sleep disturbances, mobility limitations, and anxiety, depression, and reduced self-efficacy [

21,

30,

31,

32,

35]. These impacts often influence long-term recovery and rehabilitation outcomes and extend beyond the hospital stay. Patients with advanced-stage PUs have higher risk for infection, sepsis, and delayed recovery from underlying medical conditions, and have been associated with increased morbidity and mortality [

22,

24,

25,

26,

29]. In addition, multiple coexisting PUs create compound challenges, reflecting underlying vulnerability, nutritional compromise, and complex care needs, further straining healthcare resources [

4,

33,

34]. The psychological and social implications of multiple PUs, including body image, social withdrawal, and caregiver strain, emphasize the importance of patient-centered approaches that address physical and psychosocial dimensions of care [

35,

36].

PU staging provides a framework for assessing injury severity, guiding treatment decisions, and evaluating clinical outcomes. Stage I PUs involve non-blanchable erythema of intact skin and with significant opportunities for early intervention to prevent progression [

26,

27]. Stage II injuries involve partial-thickness tissue loss and requires specialized wound care. There is still substantial healing potential [

28]. Stage III and IV PUs, represent full-thickness tissue loss, and may extend into muscle, bone, or supporting structures. They are associated with increased risk for infection, sepsis, and prolonged recovery [

29]. Advanced-stage PUs also increase resource utilization, and increased economic burden, emphasizing the critical need for early recognition and prevention [

24,

26,

31].

The anatomical site and multiplicity of PUs also influence clinical outcomes. The sacrum, heels, buttocks, hips, and elbows are the most affected regions, and multiple coexisting ulcers indicate compounded clinical challenges [

4,

33]. Multiple PUs are frequently linked with malnutrition, or advanced frailty, and limited healing capacity, increased risk for infection, prolonged hospitalization, and increased mortality risk [

4,

33,

34]. The psychological burden of multiple ulcers compounds patient vulnerability and interventions that address mental health alongside physical wound care [

35,

36].

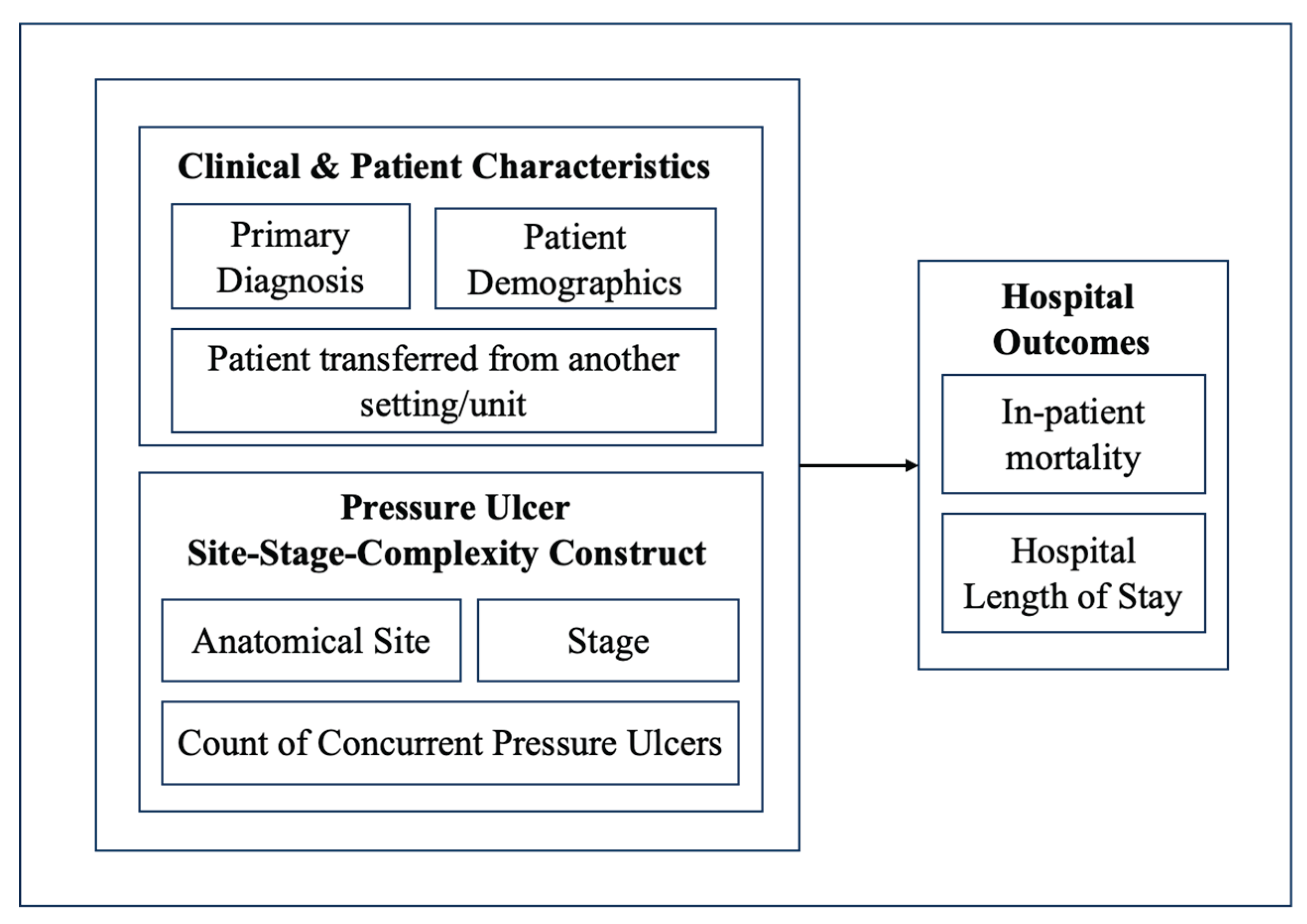

While prevention strategies and risk assessment tools are well-established, there remains a need to quantify the frequency, stage, and anatomical characteristics of PUs and evaluate their association with clinical outcomes. Mapping PU prevalence and PU characteristics can offer a useful tool to understand early risk detection, preventive interventions, and improved resource allocation. Moreover, understanding the relationship between PUs and adverse outcomes provides evidence to support quality improvement initiatives and patient safety policies. The present study aims to addresses this knowledge gap (i) mapping the frequency, anatomical site, stage, and characteristics of PUs, and (ii) examine their association with inpatient LOS and hospital mortality among hospitalized elderly patients. By combining descriptive analyses of PU patterns with outcome associations, this study aims to improve understanding of PU burden in hospital settings. Findings could also guide prevention strategies, inform clinical risk stratification (and help healthcare providers prioritize high-risk patients), optimize care processes and support evidence-based patient safety interventions.

4. Discussion

This study shows the clinical significance of pressure ulcers (PUs) in hospitalized Medicare patients. Overall PU prevalence was found to be 3.7%, consistent with prior national estimates showing PUs being a problem in acute care settings [

21]. The sacral region was the most frequent site, followed by buttocks and heels. These anatomical sites are most prone to immobility-related pressure [

4]. Stage 2 ulcers were the most common overall. This is likely because they represent the point at which early skin damage progresses to partial tissue loss, making them clinically visible. Stage 1 ulcers, although more frequent in practice, are often underreported since they involve only redness of intact skin, sometimes subtle. By contrast, Stage 2 PUs present with clear skin breaks, prompting recognition, and coding.

A high proportion of PUs are unstageable or unspecified ulcers, particularly in the right heel, left heel, and head, where nearly half of the cases lacked a definitive stage classification. While it is not clear whether these represent limitations in documentation or a distinct clinical profile, there are some reasonable explanations. Heel ulcers, for instance, are often covered with eschar that prevents accurate staging until debridement, while head ulcers in elderly patients may present atypically. It is also possible that hospitals with resource or training gaps contribute to inconsistent staging practices. This assumption can be furthermore explored in studies conducted at a hospital level, to account for organizational, and structural hospital characteristics. Unstageable ulcers may also hold clinical significance, because they may be proxies of overall patient vulnerability, where patient frailty and overall severity is more determinative of outcomes than wound severity. Addressing this uncertainty will require improved training in staging frameworks and standardized documentation practices. Accurate classification is required to inform appropriate treatment, and prevention strategies.

Hospital LOS was strongly correlated with PU stage and anatomical site. LOS increased from 9.4 days in Stage 1 to 15.2 days in Stage 4, showing the resource burden associated with advanced ulcers. In contrast, inpatient mortality rose modestly from Stage 1 through Stage 3 and plateaued at Stage 4, indicating that severity by stage may not be a direct mortality predictor.

PU severity, measured by locality stage score, was highest in hips and contiguous back/buttock/hip sites, while lowest in heels and head, and unstageable or unspecified ulcers were most frequent in the hip, heel, ankle, and elbow. Certain ulcer anatomical sites, such as the head, sacral area, hips, upper back, and contiguous back/buttock/hip sites, were associated with substantially longer LOS, while mortality was highest for left upper back (14%), head (12.8%), and unspecified hip (12.8%). The association of sacral, hip, head, and upper back ulcers with longer LOS and higher mortality suggests that these anatomical sites are markers of systemic frailty and serious comorbidities, where immobility, poor perfusion, and challenges in wound care would worsen outcomes.

Regression analyses identified specific sites, sacral, hip, head, buttock, and upper back, as independent risk factors for both longer hospitalization and higher mortality. These findings echo reports that ulcer anatomical site may reflect systemic illness severity and frailty rather than wound severity alone [

26].

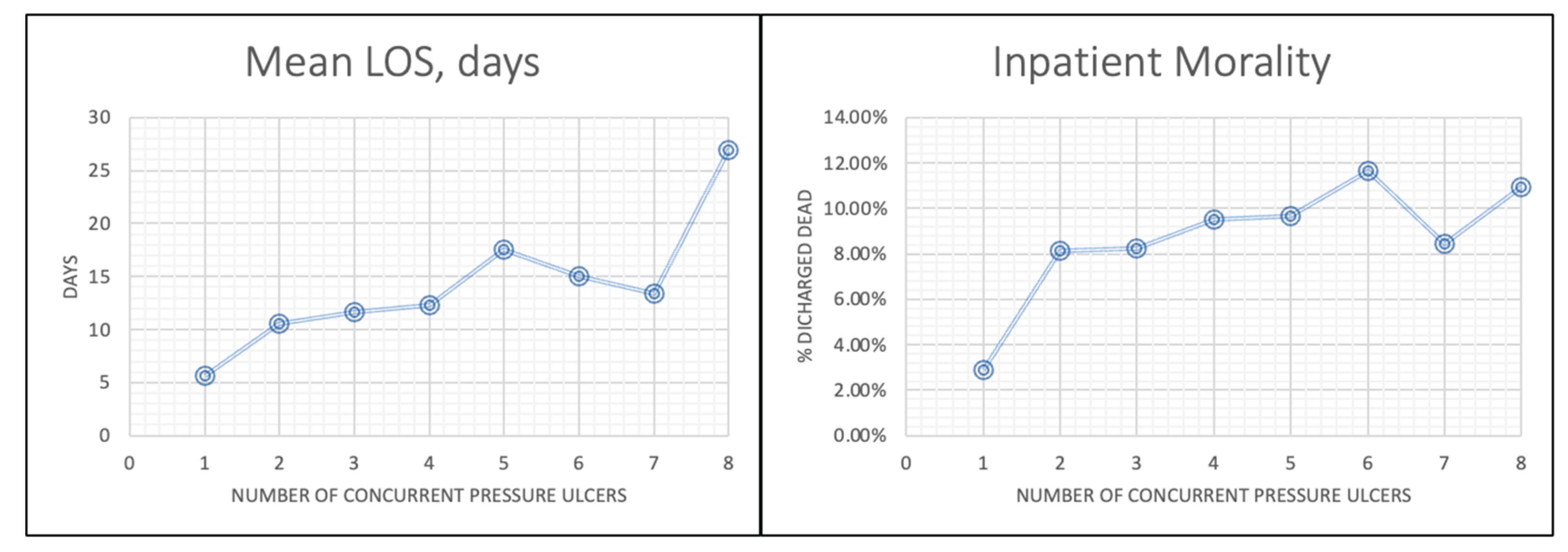

Multiplicity of ulcers was a determinant of adverse outcomes. Patients with ≥8 ulcers had a mean LOS of 23.5 days and mortality of 12.5%, compared to 10.6 days and 8.1% for those with a single ulcer. This trend shows the compounding effect of multisite ulceration, likely because of compromised healing capacity and overall systemic vulnerability [

36]. High-risk combinations, such as bilateral heels with sacral or hip involvement, were associated with especially poor outcomes, suggesting potential “red flag” patterns for clinical monitoring.

Our findings indicate that higher stage PUs were not directly associated with greater mortality risk. This somewhat counterintuitive result may reflect the reality that patients with the most severe underlying illnesses often do not survive long enough to develop advanced-stage ulcers. Another interpretation is that hospitals consistently coding higher stage ulcers may also be those with greater clinical vigilance and more robust prevention practices, which can lessen their impact on mortality. At the same time, it should be acknowledged that our study did not account for comorbidities or procedures that may contribute to ulcer development and severity. Exploring these relationships would offer a more nuanced understanding of which patient groups are most vulnerable. Still, recognizing certain combinations of ulcer anatomical site and stage as “red flags” for risk has practical value, as such awareness can help clinicians prevent avoidable harm.

When examining hospital LOS, we found that severe and multi-site ulcers are linked with longer admissions. Yet, this association may be circular: patients with prolonged hospitalizations are at higher risk of developing serious ulcers, and once ulcers appear, they tend to further extend recovery time. This feedback loop shows the importance of timely preventive strategies, consistent documentation, and early intervention.

Equally important, our findings reinforce that PUs themselves are strongly associated with extended hospital stays and, in some cases, increased inpatient mortality, regardless of primary Dx. Patients with multiple or advanced ulcers experienced markedly prolonged admissions, underscoring the dual role of PUs as both a cause and a consequence of longer hospitalizations. Certain ulcer sites, such as sacral, hip, and head, were independent predictors of poor outcomes, suggesting that anatomical site conveys additional risk beyond stage alone.