Abstact:

Higher education inculcates in students an enduring curiosity about the world. Accomplishing this goal requires helping undergraduates recognize that learning is a social process occurring within multiple communities of practice. Each of these collectives provides different lenses through which aspects of reality are illuminated, none encompassing all there is to know about a subject. Students thus appreciate that learning is an open-ended processes driven by a curiosity that is never satisfied. Knowledge resulting from that process is forever being refined, a project to which undergraduates can contribute. Appreciating the many ways of knowing the world requires engaging meaningfully with these distinct communities. This is best done by participating directly in the work and lives of multiple such collectives. Field schools provide excellent opportunities in which students come to perceive, think about, and act in worlds constituted by the communy of archaeologists and that comprised of people hosting and participating in the investigations. We use our experiences directing an archaeological field school in northwest Honduras from 1983-2008 to illustrate how we used this learning environment to help undergraduates make original contributions to knowledge of the area’s past while rethinking who they are and what they are capable of achieving.

1. Introduction

Most of us enter college with what Derek Bok called “an ignorant certainty” about the world and our place within it (2006:68-69). An enduring goal of higher education is to help students question that assuredness as they achieve a realistic appreciation of the world’s complexity (Bok 2006: 68-69). Doing so means encouraging undergraduates to cultivate an enduring curiosity about what constitutes reality. Curiosity, arising from uncertainty about what we think we know, drives learning and makes it open-ended (Bradley and Kahn 2024).

Basing our remarks on the archaeological field school we directed in Honduras, we offer suggestions about how this type of education can encourage curiosity by helping students: reimagine how they learn; rethink what constitutes knowledge; and appreciate what those from different backgrounds have to teach them about the world and their relations to it. We contend that the skills taught at colleges and universities will certainly help students succeed in their various endeavors. The most important lessons offered by higher education, however, are those that encourage students to see more in the world than they thought was there and to think about their observations in ways that challenge common sense notions of reality. Neither of those aims are easy to achieve, both are crucial to our collective futures. Trying to accomplish them begins with considering what learning is.

2. Learning as a Social Process

We suggest that learning consists of: registering stimuli from our surroundings using all our senses; interpreting what those inputs signify; acting based on those inferences; and, evaluating the rightness of our analyses as we assess our actions’ outcomes (Barth 2002:1; Clarke 2005:84; Hamilakis 2001:8, 10; Hamilakis and Rainbird 2004:50; Hawkins 2014; Lave and Wenger 1991; Lock 2004:59; Wenger 1998:101,184,273). Those judgments are essential parts of learning. If our actions yield expected results, we have reason to believe that the principles we use to understand the world are valid. If not, then we are justified in questioning the reliability of our observations and the ways we interpret them. We are thus motivated to find better ways of doing both (Lemert and Branama 1997).

Learning is pervasive, something we do every waking moment of our lives. Students, therefore, do not attend college to master a process in which they are already engaged, if often subconsciously. What higher education provides is the opportunity to learn mindfully and so to become better at it. By “better” we mean heightening our awareness that learning is not something localized within individual heads. Rather it is a distributed process. We never learn alone but always from and with multiple people (Hutchins 2006; Salomon 1993; Wolcott 1982). The stimuli we attend to are those others have called to our attention. Similarly, the principles we use to interpret those inputs and evaluate our actions are ones we acquire from people with whom we share understandings about what constitutes reality. Consequently, learning, like all we do, is social, embedded within recurring interpersonal interactions. The contexts in which learning in all its forms occurs are communities of practice (Lave and Wenger 1991; Wenger 1998:4, 45). These social formations are instantiated by their members’ collective participation in projects through which those involved cooperate in achieving aims they deem valuable (Ortner 1995). These projects can range from clearing and cultivating fields to mapping the galaxy. Neophytes master ways of observing, reflecting, and acting appropriate to the community through formal and informal interactions with established members of the collective. Such learning is made possible by shared means of communication through which crucial information is passed and group activities coordinated. Communities of practice range in size and duration. The crucial point is that each constitutes a specific way of being in the world, a culture born of interactions among people who have learned to observe, reflect, and act from each other.

3. The Many Forms of Knowledge

What emerges from these social dealings is knowledge about aspects of reality that interest a community’s members. Each community of practice makes truth claims about different features of the world, informed by their participants’ shared experiences, values, and assumptions (Bok 2006:68-69, 109-114; Bradley and Kahn 2024; Wenger 1998). Many of us, students included, assume that knowledge generated by different communities can be ranked hierarchically. Some claims about the world, say those advanced by scientists, might be seen as superior to those made by others. Ranking truth claims is harder than it looks and may well be counterproductive. All reliable such claims are evidence-based and context-specific. Each community of practice has something to teach the rest of us within their area of expertise. The privileging of Western science encouraged members of the medical community, for example, to ignore for many years what Indigenous people working within their communities of practice knew about the curative properties of certain plants. As it turns out, participants in all these communities had much to teach one another about caring for the sick.

Knowledge is, therefore, not so much a thing that can be slotted neatly into a single hierarchy of value as it is the outcome of open-ended learning processes pursued by many in very different ways. Each generation working within their respective communities of practice contributes novel insights to a body of thought they will never see completed. This does not mean that there are no knowable truths. Instead, we need students to understand that there are many truths that can be advanced about our world. Each is valid in the moment, pertaining to a distinct knowledge domain, and the foundation for more refined understandings that will emerge as observing, analyzing, and assessing continue.

4. Learning from Many Teachers

A college education should, therefore, make students aware that there are as many things to know as there are communities of practice whose members are devoted to pursuing knowledge. It is within these collectives that truth claims are advanced, challenged, and revised by people who have honed their expertise together. Learning as a process is everywhere the same. Guided by different premises, alert to distinct stimuli, driven by sundry goals, members of varied communities pursue knowledge that illuminates different aspects of a reality that refuses to be captured within one way of interpreting, observing, and acting.

Acknowledging that there are many ways of understanding our shared reality encourages curiosity if only because it alerts us to the limits of our entrenched perspectives while opening us up to alternative ways of observing, thinking, and acting. Learning to communicate across community boundaries, drawing on the well-honed perspectives of many, are essential abilities needed to solve just about any problem. This is because no one community’s knowledge encompasses all there is to understand about a topic. Climate scientists, for example, have much to teach us about the effects of fossil fuels on global climate change. They, however, have little to say about what a shift to renewable energy sources would mean for those working in refineries and on drilling platforms. A humane climate policy would need to be informed by perspectives offered by members of these and other relevant communities, thus ensuring a habitable environment in which displaced workers are made whole. It is crucial, therefore, to encourage students to realize that: the ways of learning and knowing with which we are familiar are limited; we must seek out, therefore, those with other perspectives to address our collective crises; and so must find ways to make common cause with diverse people.

Recognizing the many communities with stakes in, and knowledge about, any issue, therefore, stresses the importance of working with all those who know aspects of, but not all about, a situation we are facing together. It should also encourage skepticism about fabricated communities whose goals are not the pursuit and assessing of knowledge, but its subversion in the interest of personal gain. Deciding among claims to truth is never easy. It is harder if we do not cultivate the habit of critically assessing what we have to learn from others and what some gain by promoting their own views (Bok 2006: 109-114; Hamilakis 2001:9-10; 2004: 293, 301; Lock 2004: 59; Shore and Wright 1999).

Appreciating what different communities of practice have to teach us requires participating at least peripherally in their shared work. These engagements also help clarify the distinctions between learning communities that arise organically in the pursuit of knowledge from those created to promote self-serving propaganda. This is what a liberal arts curriculum encourages. By taking courses taught by members of distinct communities of practice, students learn something through readings, lectures, discussions, and labs about how their practitioners know the world.

5. Anthropology as a Community of Practice

Anthropologists are well positioned to play a crucial role in this process. On the one hand, the field spans humanistic through social and natural science approaches to observation, analysis, and action. It is a microcosm of the liberal arts. On the other, it is the only academic discipline that explicitly challenges western common sense notions about what guides, and gives meaning to, human interactions, about what defines ‘reasonable’ and ‘normal’ in different contexts. If a student is paying even modest attention to what they are learning in anthropology, they should become increasingly uncomfortable. Uncomfortable as they come to realize just how much of what they ‘know’ about the world and its people is based on untried, historically contingent, culturally constructed assumptions. Uncomfortable as they grapple with the ambiguity of human behaviors’ many meanings and the multiple ways anthropologists have concocted for deciphering the significance of those actions. Anthropology, done well, encourages just the sorts of critical musings that are central to frustrating complacency and spurring the uncertainty that drives curiosity and lifelong learning (Pluciennik 2001: 26).

Anthropology, like other social sciences and the humanities, is often judged, and judged harshly, for not teaching marketable skills (Higgins 1985: 321). The neoliberal moment in higher education, in which student- and parent-clients demand good value for money in the form of abilities esteemed in the marketplace, seemingly devalues much of what anthropology has to offer (Barth 2002:9; Hamilakis 2004: 289-292; see also papers in Strathern 2000). In defending the field, some have argued that anthropology, along with other liberal arts disciplines, actively promotes skills in reasoning, speaking, and writing, along with the ability, in our case, to work across cultures, that many employers value (e.g., Upham et al. 1988). We also teach practical techniques, such as how to conduct an interview, lay out a trench, or, more broadly, conduct multi-stage research projects, that are directly applicable in a number of careers, including the business of Cultural Resource Management (Upham et al. 1988). As important as it is to emphasize the marketable value of anthropological knowledge and techniques, these skills do not by themselves engender curiosity (Hamilakis 2001, 2004; Shore and Wright 1999). Accomplishing that aim means demonstrating how the skills developed in any community take on meaning only to the extent that they focus observations, enhance analyses of them, and promote successful actions based on those assessments. These linkages are clarified when students participate directly within a community of practice (Hawkins 2014; Wegner 1998).

6. Putting Thought into Action on Field Schools

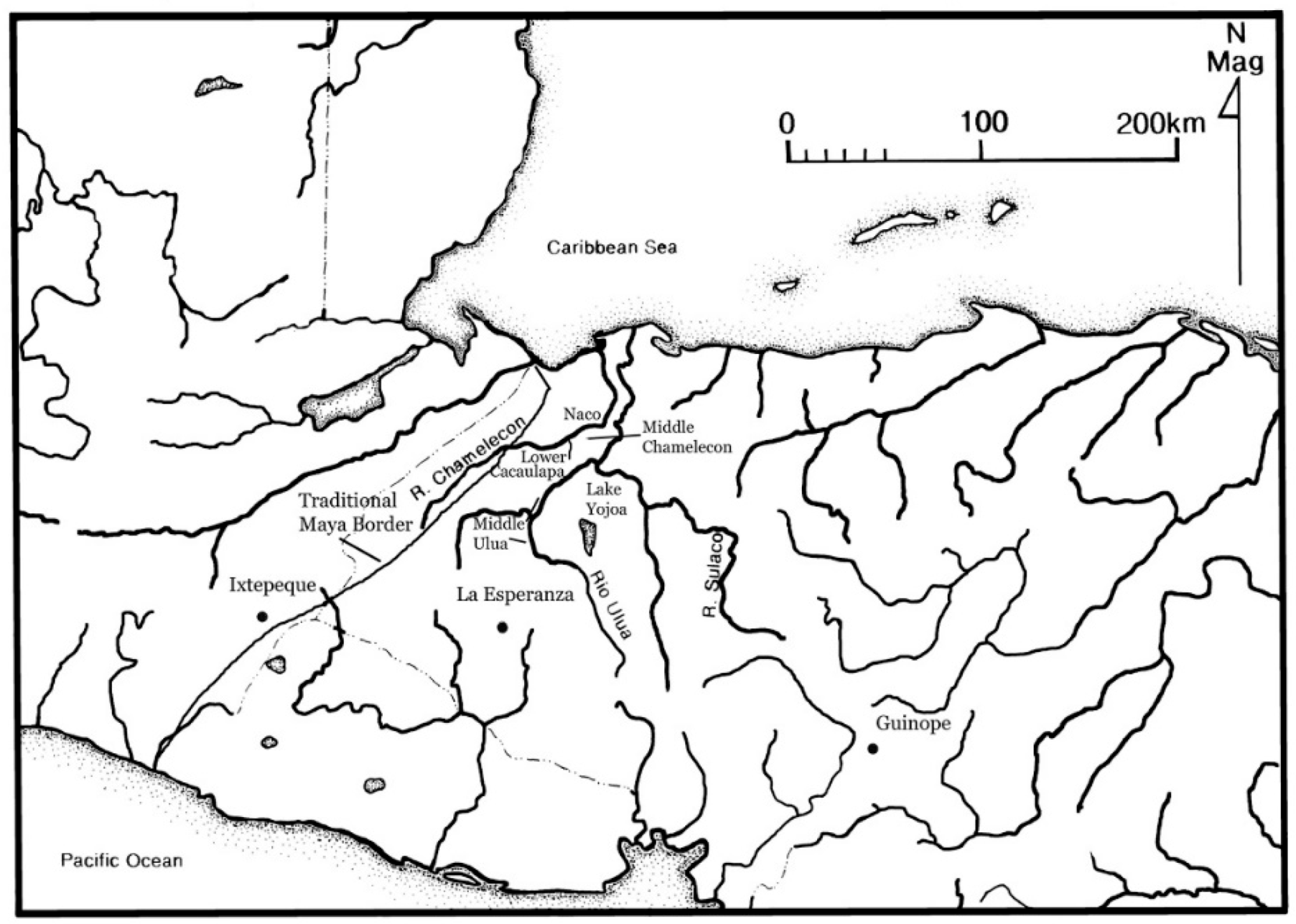

It is difficult to encourage undergraduates to experience what it means to observe, think, and act as an anthropologist within the confines of a classroom. Ideally, doing so requires that student practices constitute significant investigations yielding results they can meaningfully contemplate. Undergraduates should then be encouraged to share those findings with others who, in turn, can comment on their results, hopefully leading to new insights. Archaeologists have an established means for accomplishing these objectives in field schools. We argue that this learning environment, often narrowly rationalized as teaching practical skills, can serve as a powerful basis for accomplishing additional pedagogical objectives. Doing so requires re-thinking a field school’s aims, still teaching techniques but making it clear how those practices contribute to the distinct ways of learning that characterize anthropology’s community of practice. In pursuing this topic we will not dwell on how field schools teach archaeological method and theory to undergraduates. Instead, we focus on the field school as a means of fomenting critical reasoning on several levels. That is what we tried to do while directing an archaeological field school from 1983-2008 in the Naco, lower Cacaulapa, middle Chamelecon, and middle Ulua valleys of northwest Honduras (

Figure 1; Urban and Schortman 2019).

7. Learning How to Know

We suggest that field investigations pose numerous opportunities for students to destabilize their understanding of how learning proceeds and what knowledge is by grappling with open-ended problems and ambiguous results. This is especially the case where undergraduates follow the research process through from: formulating a question to ask about the past; developing a strategy to address that query; conducting the necessary work; analyzing their results; and, reporting on those finds in a systematic manner to project members and professional audiences (Hamilakis 2001:9; Hawkins 2014; Weldrake 2004: 192). In our experience, students given this freedom and responsibility come to appreciate:

How observations are conditioned by the interpretive frameworks guiding an investigation;

The ways in which those conceptual schemes can be challenged by new findings leading to critical evaluations of all you thought you knew;

How to make reasoned judgments about the past based on incomplete data, acknowledging that these interpretations are more inferences to the best explanation than definitive truths (Bevan et al. 2004: 209; Copeland 2004; Hawkins 2014; Urban and Schortman 2019).

Such tacking back and forth between theory and data highlights how we make sense of life in general as we apply interpretive frameworks to observations and critically assess the former in reference to the latter. Being clear about the process helps undergraduates to be more alert to the steps involved in all learning. Such awareness also makes students better problem-solvers if only because they are more keenly aware of how easily their preconceived notions can lead them astray (Hamann 2003). It also maintains the link between knowledge and self-development that classroom-based instruction can obscure (Bunderson et al. 1996:41; Hamilakis 2004:289; Hawkins 2014; Lock 2004: 59; Wilcox 2004: 218). Rather than a commodity transferred from professor to student, knowledge is revealed to be part of a “life-transforming experiential process” to which undergraduates can contribute and from which they and others can benefit (Hamilakis 2004: 289). At the very least, students who engage in this process should find it harder in the future to take received wisdom for granted. They should be especially aware of the temptation to accept anything as true simply because it reinforces premises with which they are comfortable (Clarke 2005: 84; Hamilakis 2001:9; 2004:296)

Conducting meaningful research also inculcates a sense of confidence in undergraduates who pursue their investigations through to successful conclusions. That success is measured by a student’s ability to generate and report on new information that helps address important, open-ended questions. When undergraduates present their results at gatherings of professionals they become, and see themselves as, contributors to the ongoing processes of observation and critical reflection through which knowledge of the world is deepened and expanded within anthropology’s community of practice (Barth 2002:10; Hawkins 2014; Wegner 1998).

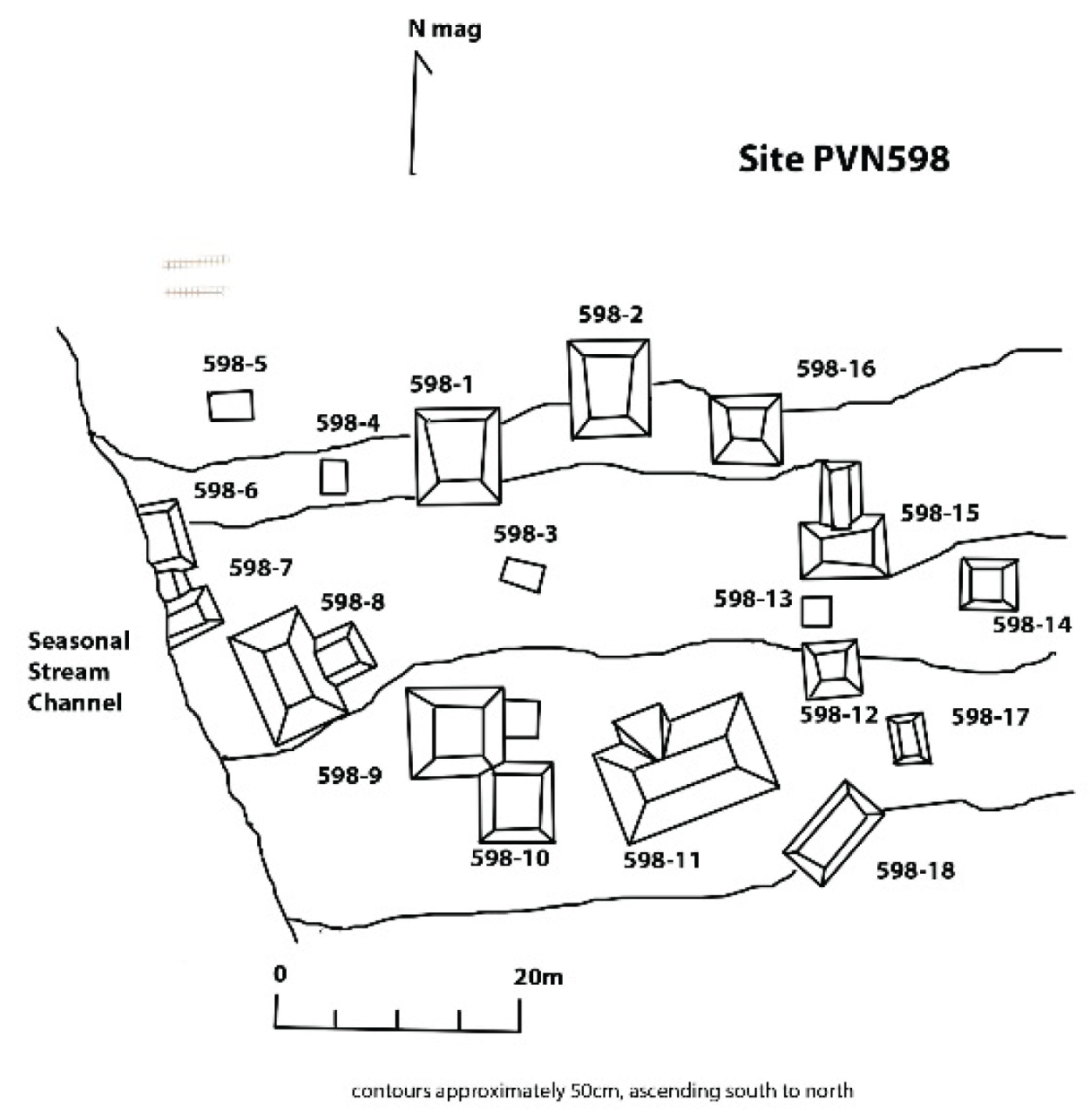

Accomplishing these goals takes time. We began by running 10-week long field programs for students (1983-1986) but found that the participants just reached the point where they could conduct research confidently and effectively on their own when the season ended. This led us, with the support of Kenyon College and the Instituto Hondureňo de Antropologia e Historia, to shift to 11, five-month-long seasons from 1985 through 2008. These more extensive field experiences gave undergraduates the opportunity to hone their skills as investigators while getting a deeper appreciation for the questions they might use those skills to answer. After two months of field and classroom training, students generally worked with 8-10 local men for an additional two months excavating a household (

Figure 2). These ubiquitous domestic compounds, dating from 600-1000CE, consist of stone-faced platforms, usually under 1m high, that supported residences, work- stations, and storerooms, all arranged around a plaza. Households were basic units in which food was produced and consumed, crafts were practiced, children were raised, and religious rituals performed. They are locales in which ancient communities of practice took shape and were sustained, their investigation providing valuable information on the varying ways people organized their lives as they satisfied their needs. Student research has, over the course of 25 years, yielded an unprecedented corpus of information on how commoners in ancient Southeast Mesoamerica made lives of meaning.

We came to realize that undergraduates did not have sufficient time in the field to analyze, compare, and reflect on the significance of their household studies. Students quite quickly became good field technicians but often had trouble translating observations on the features, strata, and artifacts they unearthed into interpretations of past behaviors. This led us to institute a follow-up course in the United States during the semester after the field season. That class gave the undergraduates the chance to write up formal reports on their research and consider in detail how what they found answered, or failed to answer, the queries they originally raised. The end-products of these efforts were 34 papers they delivered on their work at the Society for American Archaeology meetings and 39 honors theses. Presenting their research to professionals in the field and outside examiners was unnerving to most but ensured that the students appreciated how knowledge is created through, and comes to constitute, communities of practice. They also realized that they were contributors to that collective enterprise along with the members of staff and local people with whom they worked (Bourdieu 1977, 1990; Hawkins 2014; Wegner 1998). Whatever the long-term significance of their research, pursuing such investigations literally transforms students’ senses of themselves and their capacities.

Results of student investigations, together with their theses, are posted at

https://digital.kenyon.edu/honduras/. The archive contains all field records generated by undergraduates and staff who worked on the field school. By providing access free of charge to the notes, drawings, photographs, and other records made by project members, the work of undergraduates and others is available to those who want to learn about the people we were fortunate enough to study for over two decades (see Schortman et al. 2020 for a description of the archive and examples of its use in teaching and research).

8. Learning How to Know Others

Field schools are wonderful environments for enlarging a student’s field of social interactions to include people who they would otherwise never get to know in more than a perfunctory manner, if at all (Hamilakis 2004:295). Certainly, this is the case for a field school’s participants who often form close bonds with each other as a result of their shared experiences and mutual dependencies. We are thinking more specifically, however, of ties forged with the communities whose members contribute significantly to, and have a stake in, a field school’s activities and outcomes. Such interested parties may be quite varied, their life experiences diverging considerably from those of the undergraduates. This is especially the case when a field school is conducted outside the student’s home country. Because we know ourselves through our interactions with others, the more diverse the backgrounds of those with whom we deal, the richer our understanding of who we are and the greater our respect for those who comprehend the world differently from us. Promoting this broadening of student visions requires that field programs, no matter where they operate, be structured in ways that destabilize student perceptions of themselves and those around them by helping undergraduates re-think their relations to people living in other communities of practice.

One way we sought to achieve these aims was by offering semester-long courses, as part of the field school, on the local history and cultures of the area where the research was carried out. These classes served to shake student complacency to the extent that they challenged the participants’ sense that they knew where they now lived and who their neighbors were.

In addition, we encouraged the undergraduates to use their developing understanding of local cultures and history to engage with our hosts in informal settings. This involvement was facilitated by the small sizes of the towns where we lived, none having more than 5,000 residents, and the fact that students worked regularly with local people in the field and lab. It was in the course of interactions while excavating or conducting artifact analyses that students and local residents had a chance to talk with, and get to know, one another. From there, students were invited to take part in events, such as soccer and volleyball games. These group interactions led to invitations to birthday parties and christenings just as our neighbors were welcomed at our parties.

Structuring and supporting student involvement in what were to them deeply unfamiliar ways of knowing and being depended on significant support from field school staff and the directors. Most importantly, theses engagements relied on the willingness of our hosts to teach the students what they needed to know to behave properly in their new setting. It was critical to monitor, but not control, student interactions in town to make sure they were learning in new ways without disrupting the lives of their local teachers. We relied heavily of local contacts we had developed over the years to keep track of student interactions with our neighbors just as we worked with staff to assess show the undergraduates were feeling about those dealings. Having five months allowed these relations to take shape more fully than was the case within the 2-3 months of the earlier field seasons.

All of the students went through periods when they despaired of ever being able to avoid making mistakes in conducting archaeological research or in their dealings with local people. These were followed by intervals of euphoria when all seemed to be going well. Such satisfying moments were inevitably succeeded by an awareness of how much more they still had to learn. Through time, these emotional and intellectual oscillations moderated until by the semester’s end students had the sense that they were beginning to understand something of their local co-workers’ and friends’ aspirations, perceptions, and models for living. They were not part of the community where they were residing, but they did appreciate something of its rich complexity. Encouraging undergraduates to participate in a host’s community of practice:

Problematizes student understandings of those impacted by the investigations (e,g., realizing that the past has different meanings for the diverse parties interested in it);

Helps students to understand what their interlocutors are ‘saying’ in the broadest sense of that term;

Provides fodder for critical reflections on all aspects of the field experience, including interactions with the living;

Encourages students to see the common humanity that unites us all while not losing an appreciation for cultural and socio-economic differences.

Near the end of the 2002 field season, a student remarked to Schortman at dinner, “I always knew that poor people were people but here I am working with these local men and they’re very poor but we laugh, joke, talk about our families, and they really are people!” There are subtler ways of conveying this basic idea but they got at the heart of what we were attempting to do for the 25 years we worked with undergraduates in Honduras. That is, to get students to the point where they could empathize with men and women whose lives were different in many ways from their own. In so doing, students’ senses of self and their relations to others were unsettled and expanded.

Accomplishing this goal was never easy; some undergraduates remarked that the experience at times could be too strong. Nonetheless, every one of the undergraduates we worked with said that they had never, up to that point, felt more alive, more challenged, and more satisfied with themselves for meeting those challenges, than when they were working in Honduras. They all acknowledged that they had grown in unexpected ways and took those experiences and insights into their careers in business, medicine, teaching, social work, government service, and even anthropology.

Mindful disruptions of student cultural complacency, therefore, require:

Offering courses that give undergraduates the background and context needed to help them observe intelligently the place where they are living and to reflect critically on their experiences with members of host communities;

Opportunities to put that knowledge into practice through daily interactions with local people in, and especially outside, work settings;

Constant support from the directors, staff, and local colleagues to ensure that students are not overwhelmed by their encounters or are moving through them oblivious to the consequences of their actions (Hamilakis 2001:9; Hawkins 2014).

9. Conclusions

If learning consists of reflecting critically on experiences and putting the resulting insights into action, field schools can serve as excellent educational environments. They provide settings in which undergraduates come to grips with the complexities of making reasoned judgments based on incomplete and ambiguous data, thereby subverting simplistic understandings of what knowledge is and how it is formulated. In addition, field schools can provide means for facilitating mindful engagements with people from varied backgrounds who come to be seen as fully human and not just representatives of the exotic other. Students also come to appreciate have much they have to learn from those they never thought of as teachers. Accomplishing both aims requires:

Providing undergraduates with the skills and concepts needed to successfully conduct research and interact with their hosts in multiple settings;

Opportunities to put what they have learned into practice in meaningful ways, within and outside research contexts;

Support for both of these efforts by the directors, staff, and local colleagues who, while allowing students to make mistakes, help them to make sense of their successes and errors;

All while ensuring the investigations meet professional standards and local people are treated respectfully.

By teaching practical skills and critical thinking such programs can simultaneously meet calls for a narrow form of accountability while subverting the premises on which such an auditing culture is built (Hamilakis 2004: 291; papers in Strathern 2000). That subversion comes in the form of enhancing student capacities for critical reflection on cherished assumptions. Those assessments are facilitated by participating with members of communities who observe, understand, and act in the world in ways with which students are familiar. In the course of seeing reality anew, students come to realize that they have much to contribute to our understandings of the past just as they have a lot to learn from those who at first seem too foreign to understand. They also grasp the importance of communicating across community boundaries, something that is essential if we are ever to combine the varied perspectives of many in achieving the common good. Once students know this is possible, they have the confidence to keep making those connections.

Most field school participants will not become archaeologists. That was certainly the case on the program we directed. They are, however. citizens of the planet called on to communicate respectfully and meaningfully with those who see the world differently from them, to make judgments based on incomplete data, and to act with diverse people on issues that affect everyone. Field schools are important arenas in which these citizens can hone their observational and interpretive skills to benefit them and all of us who share the earth. :

Acknowledgments

Our experiences working with undergraduates in Honduras were made possible by the generous support of the National Science Foundation (especially its Research Experiences for Undergraduates program), National Endowment for the Humanities, National Geographic Society, Wenner-Gren Foundation, and Kenyon College. Posting field records to the online archive was supported by generous grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources. Colleagues at Kenyon greatly facilitated our collaboration with students in the field, re-arranging schedules and providing all manner of practical and moral support without which our teaching efforts would have been impossible. The staff and directors of the Instituto Hondureňo de Antropologia e Historia were our constant and esteemed collaborators throughout our many years teaching and conducting research in Honduras. Residents of the communities where we worked were invariably welcoming hosts and valued collaborators in our investigations and pedagogical efforts. There is no doubt that the undergraduates learned as much, likely more, from interacting with these men and women as they did from us. We are very grateful to all these people and institutions for their generous support of student learning in Honduras. Perhaps our deepest thanks go to the undergraduates themselves. It was through introducing them to a country and field that we love that our interest in, and appreciation for, that place and discipline was enriched far more than if we had conducted the work without them. All errors and omissions in this paper are solely the authors’ responsibilities.

References

- Barth, Fredrick 2002 An Anthropology of Knowledge. Current Anthropology 43: 1-18.

- Bevan, Bill, John Barnatt, Mike Dymond, Mark Edmonds, and Graham McElearney 2004 Public Prehistories: Engaging Archaeology on Gardom’s Edge, Derbyshire. In, Education and the Historic Environment. Don Henson, Peter Stone, and Mike Corbishley eds., pp. 195-211. London: Routledge.

- Bok, Derek 2006 Our Underachieving Colleges: A Candid Look at How Much Students Learn and Why They Should Be Learning More. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre 1977 Outline of a Theory of Practice. R. Nice translator. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 1990 The Logic of Practice. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Bradley, Elizabeth and Jonathon Kahn 2024 In Pursuit: The Power of Epistemic Humility. Inside Higher Ed https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2024/08/28/power-epistemic-humility-opinion Accessed August 28, 2024.

- Bunderson, Eileen, Adrian van Mondfrans, and Mark Henderson 1996 The Baker Village Teachers’ Archaeology Field School: A Case Study of Public Involvement in Archaeology. Journal of California and Great Basin Archaeology 18: 38-47.

- Clarke, Catherine 2005 Archaeology: Another Story. Australian Archaeology 61: 80-87.

- Copeland, Tim 2004 Interpretations of History: Constructing Pasts. In, Education and the Historic Environment. Don Henson, Peter Stone, and Mike Corbishley eds., pp. 33-40. London: Routledge.

- Farah, Kirby, Aspen Kemmerlin, and Benjamin Luley 2024 Experiencing Archaeology beyond the Classroom. The SAA Archaeological Record 24:34-39.

- Hamaan, Edmund 2003 Imagining the Future of the Anthropology of Education if We Take Laura Nader Seriously. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 34: 438-449.

- Hamilakis, Yannis 2001 Interrogating Archaeological Pedagogies. In, Interrogating Pedagogies: Archaeology in Higher Education. Paul Rainbird and Yannis Hamilakis eds, pp. 5-12. British Archaeological Reports International Series 948, Archeopress, 948.

- 2004 Archaeology and the Politics of Pedagogy. World Archaeology 36:287-309.

- Hamilakis, Yannis and Paul Rainbird 2004 Interrogating Pedagogies: Archaeology in Higher Education. In, Education and the Historic Environment. Don Henson, Peter Stone, and Mike Corbishley eds., pp. 47-54. London: Routledge.

- Hawkins, John 2014 The Undergraduate Ethnographic Field School as a Research Method. Current Anthropology 55: 551-590.

- Higgins, Patricia 1985 Teaching Undergraduate Anthropology. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 16: 318-331.

- Hutchins, Edwin 2006 The Distributed Cognition Perspective on Human Interaction. In, Roots of Human Sociality: Culture, Cognition, and Interaction. Stephen Levinson, Nicholas Enfield eds., pp. 375-398. London: Routledge.

- Lave, Jean and Etienne Wenger 1991 Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lemert, Charles and Ann Branaman (eds.) 1997 The Goffman Reader. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Lock, Gary 2004 Rolling Back the Years: Lifelong Learning and Archaeology in the United Kingdom. In, Education and the Historic Environment. Don Henson, Peter Stone, and Mike Corbishley eds., pp. 55-64. London: Routledge.

- Ortner, Sherry 1995 Resistance and the Problem of Ethnographic Refusal. Comparative Studies in Society and History 37:173-193.

- Pluciennik, Mark 2001 Theory as Practice.. In, Interrogating Pedagogies: Archaeology in Higher Education. Paul Rainbird and Yannis Hamilakis eds, pp. 21-28. British Archaeological Reports International Series 948, Archeopress, 948.

- Salomon, Gavriel 1993 Distributed Cognitions: Psychological and Educational Considerations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schortman, Edward, Ellen Bell, Jenna Nolt, and Patricia Urban 2020 The Past is Prologue: Preserving and Disseminating Archaeological Data Online. In, Anthropological Data in the Digital Age. Jerome Crowder, Lindsay Poirier, Mike Fortun, and Rachel Besara eds., pp. 185-207. NY: Springer.

- Shore, Cris and Susan Wright 1999 Audit Culture and Anthropology: Neo-Liberalism in British Higher Education. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 5:557-575.

- Strathern, Marilyn (ed.) 2000 Audit Cultures: Anthropological Studies in Accountability, Ethics, and the Academy. New York: Rourledge.

- Upham, Steadman, Wenda Trevathan, and Richard Wilk 1988 Teaching Anthropology: Research, Students, and the Marketplace. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 19: 203-217.

- Urban, Patricia and Edward Schortman 2019 Archaeological Theory in Practice. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Wegner, Etienne 1998 Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Weldrake, Dave 2004 Archaeology at Wilsden, West Yorkshire: A Local Focus for National Curriculum Work. In, Education and the Historic Environment. Don Henson, Peter Stone, and Mike Corbishley eds., pp. 185-193. London: Routledge.

- Wilcock, Damion 2004 Kilmartin House Trust. In, Education and the Historic Environment. Don Henson, Peter Stone, and Mike Corbishley eds., pp. 213-219. London: Routledge.

- Wolcott, Harry 1982 The Anthropology of Learning. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 13:83-108.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).