Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

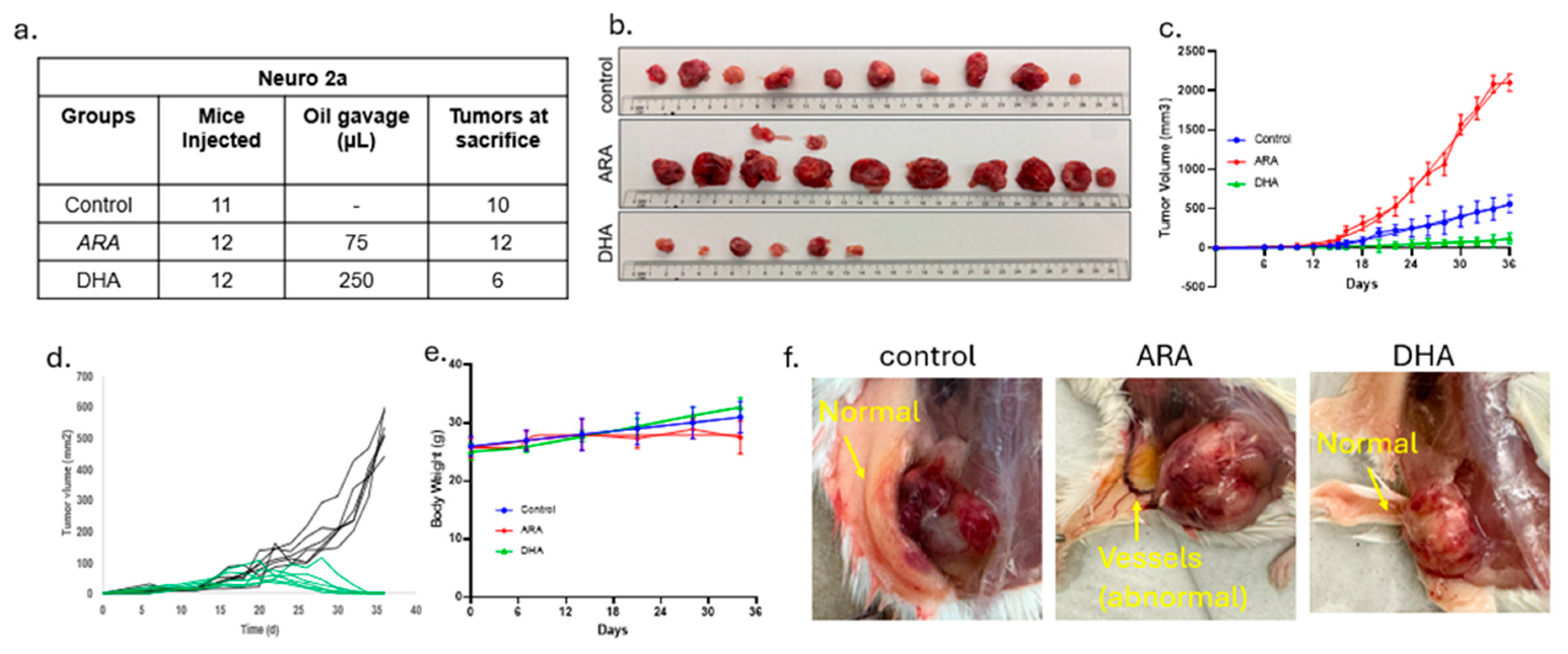

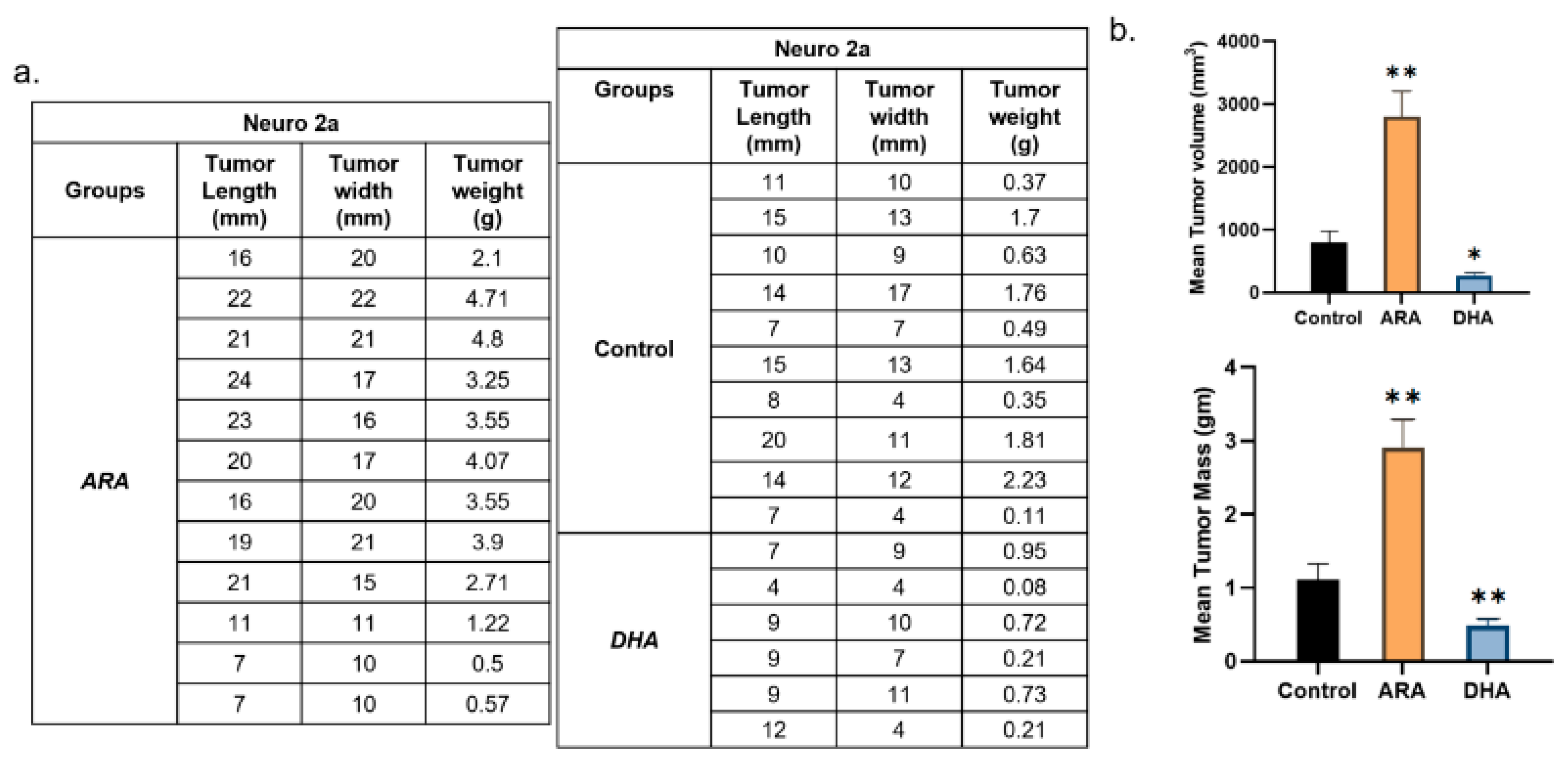

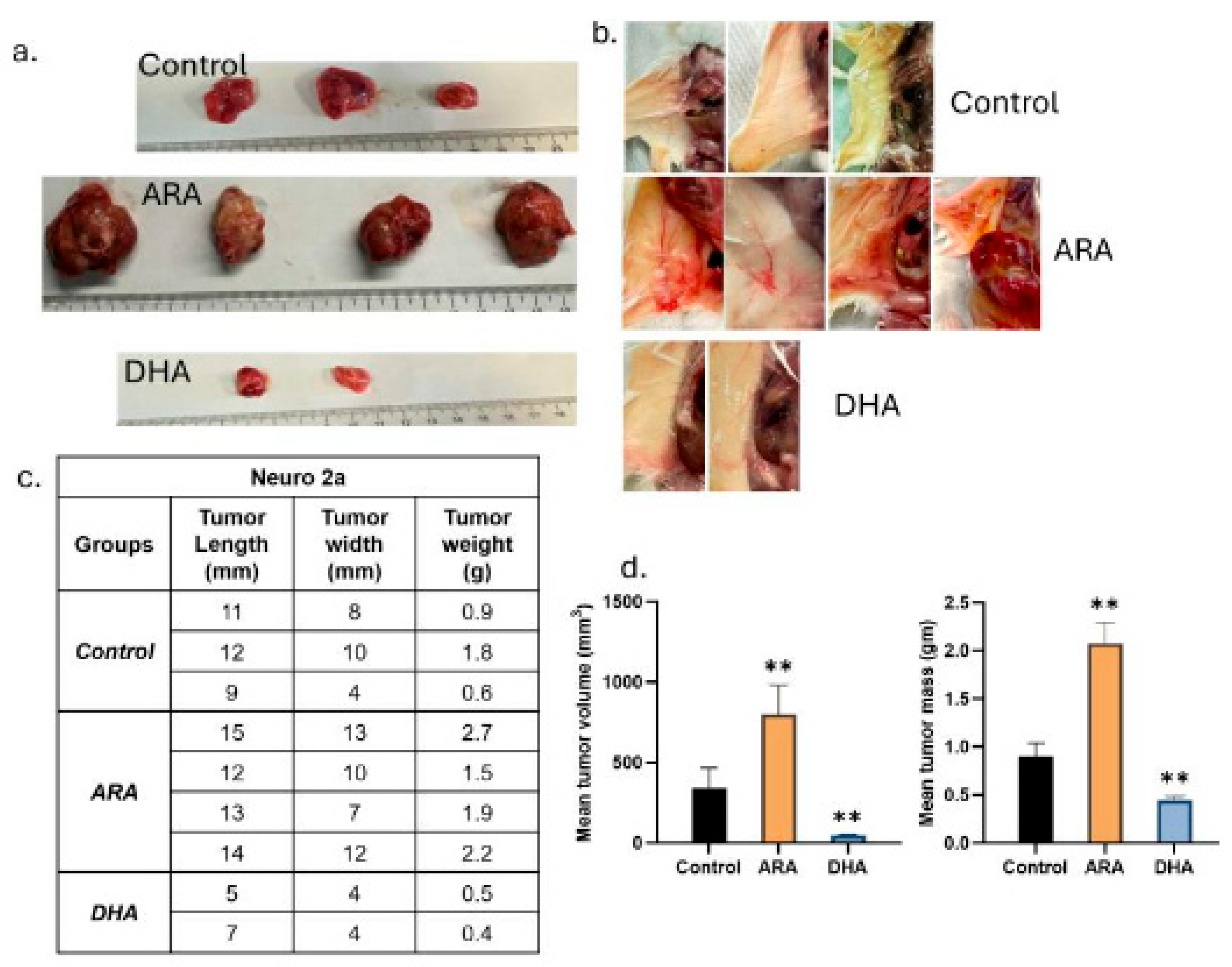

2.1. DHA Suppresses MYCN-Driven Tumor Growth While ARA Accelerates It

2.2. Tumor Burden and Regression Outcomes

2.3. Lipid Mediator Profiles Reveal Opposing Programs

| ARA Derived Eicosanoids | Liver | Spleen | Brain | Skeletal Muscle |

| PGE2 (351/271) | 0.18 | - | - | - |

| PGD2 (351/189) | 0.03 | - | - | - |

| PGF2a (353/193) | 0.06 | - | - | 0.33 |

| 8-iso-PGF2a (353/193) | - | - | - | 0.32 |

| TXB2 (369/169) | 0.04 | - | - | 0.34 |

| 5-HETE (319/115) | 0.09 | 0.32 | - | - |

| 12-HETE (319/179) | 0.12 | - | - | 0.38 |

| 15-HETE (319/219) | 0.14 | 0.32 | - | 0.34 |

| 20-HETE (319/289) | 0.11 | 0.12 | - | 0.16 |

| LTB4 (335/195) | - | - | - | - |

| LXA4/15(R)-LXA4 (351/115) | 0.14 | - | - | - |

| LXB4 (351/221) | - | - | - | - |

| 8,9-EET (319/127) | 0.10 | 0.21 | - | 0.35 |

| 11,12-EET | 0.08 | 0.30 | - | 0.37 |

| 14,15-EET | 0.07 | 0.35 | - | - |

| 5,6 DiHETrE (337/145) | 0.13 | 0.21 | - | 0.38 |

| 8,9 DiHETrE (337/127) | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.14 |

| 11,12-DiHET | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.23 |

| 14,15-DiHET | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.27 |

| PGE1 (353/ 317) | 0.20 | - | - | - |

| EPA Derived Eicosanoids | Liver | Spleen | Brain | Skeletal Muscle |

| 8,9-EpETE (317/127) | 4.69 | 3.21 | 2.19 | - |

| 11,12-EpETE (317/167) | 3.90 | 3.90 | 3.36 | 1.85 |

| 14,15-EpETE (317/207) | 4.60 | 3.54 | - | 1.94 |

| 17,18-EpETE (317/215) | 4.93 | 2.62 | 2.71 | 2.14 |

| 17,18 DiHETE (335/203) | 2.08 | - | - | 1.85 |

| 18-HEPE (317/259) | 4.87 | 3.02 | 2.84 | 1.87 |

| 5-HEPE (317/115) | 4.04 | 2.31 | 2.27 | 2.58 |

| 11-HEPE (317/167) | 3.62 | 2.85 | 2.65 | - |

| 12-HEPE (317/179) | 2.68 | 3.49 | 2.60 | 2.54 |

| 15-HEPE (317/219) | 2.68 | 1.88 | 2.14 | - |

3. Results Summary

| DHA Derived Docosanoids | Liver | Spleen | Brain | Skeletal Muscle |

| 7,8-EpDPA (343/113) | - | - | - | - |

| 10,11-EpDPA (343/153) | - | 2.37 | 1.33 | 1.83 |

| 13,14-EpDPA (343/161) | - | 2.77 | 1.53 | 2.61 |

| 16,17-EpDPA (343/273) | - | 1.97 | - | 2.27 |

| 19,20-EpDPA (343/241) | - | - | - | - |

| 7,8-DiHDPA (361/127) | - | - | - | - |

| 10,11-DiHDPA (361/153) | - | - | 1.86 | 2.12 |

| 13,14-DiHDPA (361/193) | - | 2.40 | 1.61 | 2.09 |

| 16,17-DiHDPA (361/233) | - | - | - | - |

| 19,20-DiHDPA (361/229) | - | 4.85 | - | 2.26 |

| 4-HDHA (343/101) | - | - | - | - |

| 7-HDHA (343/141) | - | - | - | - |

| 8-HDHA (343/125) | - | - | - | - |

| 10-HDHA (343/181) | - | 2.34 | 1.35 | 1.81 |

| 11-HDHA (343/165) | - | - | - | 1.69 |

| 13-HDHA (343/193) | - | 2.11 | - | 2.19 |

| 14-HDHA (343/205) | - | 2.85 | 1.64 | 2.61 |

| 16-HDHA (343/233) | - | - | - | - |

| 17-HDHA (343/245) | - | 1.91 | - | 2.31 |

| 20-HDHA (343/241) | - | - | - | - |

4. Discussion

4.1. ARA and DHA Divergent Effects in MYCN-Amplified Neuroblastoma

4.2. MYC-Associated Cancers

4.3. Lipids as Active Orchestrators of Oncogenesis

5. Conclusions

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Neuro-2a cells | ATCC | CCL-131 |

| MYCN transgene construct | Custom (human MYCN) | Details in Methods |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| A/J mice | Jackson Laboratory | Stock #000646 |

| Cell Culture Reagents | ||

| Lipofectamine 3000 | Thermo Fisher | Cat# L3000008 |

| RPMI-1640 medium | Gibco (Thermo Fisher) | Cat# 11875-093 |

| Heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS) | Gibco (Thermo Fisher) | Cat# 16140-071 |

| LC-MS/MS Standards | ||

| Primary Vascular Eicosanoid MaxSpec LC-MS Mixture | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 19667 |

| Arachidonic Acid CYP450 Metabolite MaxSpec LC-MS Mixture | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 20665 |

| Primary COX and LOX MaxSpec LC-MS Mixture | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 19101 |

| Arachidonic Acid Oxylipin MaxSpec LC-MS Mixture | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 20666 |

| SPM E-series MaxSpec LC-MS Mixture | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 19417 |

| Prostaglandin E1 | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 13010 |

| Prostaglandin E3 | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 14990 |

| Leukotriene B4 | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 20110 |

| DHA Oxylipin MaxSpec LC-MS Mixture | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 22280 |

| SPM D-series LC-MS Mixture | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 18702 |

| SPM E-series LC-MS Mixture | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 19417 |

| 8-iso Prostaglandin F2a | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 16350 |

| Lipoxin LC-MS Mixture | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 19412 |

| Docosahexaenoic Acid CYP450 Oxylipins LC-MS Mixture | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 22639 |

| Lipid Reagents | ||

| Arachidonic acid oil (40% ARA) | ARASCO | Cat# 476800 |

| Docosahexaenoic acid oil (82% DHA)x` | OMEGAVIA | N/A |

| HPLC Reagent | ||

| Acetonitrile ≥99.9% (by GC) for HPLC, for spectrophotometry | J.T. Baker | Cat# JT9012-3 |

| Methanol ≥99.8% (by GC, corrected for water content), BAKER ANALYZED™ HPLC for liquid chromatography, for HPLC, UHPLC, for spectrophotometry | J.T. Baker | Cat# JT9093-33 |

| Water, BAKER ANALYZED® HPLC for HPLC, UHPLC, for spectrophotometry | J.T. Baker | Cat# JT4218-88 |

| Acetic acid, glacial, ACS, 99.7+% | Sigma- Aldrich | Cat# A6283-1L |

| 2-Propanol ≥99.5%, BAKER ANALYZED® A.C.S. Reagent ACS | J.T. Baker | Cat# JT9084-33 |

| Hexanes, mixed isomers, HPLC Grade, 99+% | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 045652.K7 |

| Instruments and Software | ||

| ExionLC AD UHPLC | Sciex | N/A |

| Sciex 7500 QTRAP mass spectrometer | Sciex | N/A |

| Kinetex Polar C18 column (100 mm × 3 mm, 2.6 µm, 100 Å) | Phenomenex | Cat# 00D-4759-Y0 |

| Strata-X 33 µm Polymeric SPE cartridges | Phenomenex | Cat# 8B-S100-TBL |

| Sciex OS Analytics software | Sciex | Sciex OS-FULL v3.3 |

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad Software | v.3.1 |

| Excel 2024 | Microsoft | v.2507 |

6. Resource Availability

- Lead Contact: Further information and requests should be directed to J. Thomas Brenna [jtbrenna@utexas.edu]

- Materials Availability: This study did not generate new unique reagents.

- Data and Code Availability: All data supporting the findings are available from the Lead Contact upon reasonable request.

7. Method Details

7.1. Cell Culture and Transfection

7.2. Syngeneic Neuroblastoma Model

7.3. Lipid Mediator Extraction and LC-MS/MS

8. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

References

- Maris JM. Recent advances in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jun 10;362(23):2202-11.

- Crawford JR, MacDonald TJ, Packer RJ. Medulloblastoma in childhood: new biological advances. Lancet Neurol. 2007 Dec;6(12):1073-85.

- Calviello G, Serini S, Piccioni E, Pessina G. Antineoplastic effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in combination with drugs and radiotherapy: preventive and therapeutic strategies. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61(3):287-301.

- Dyall SC, Balas L, Bazan NG, Brenna JT, Chiang N, da Costa Souza F et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid-derived lipid mediators: Recent advances in the understanding of their biosynthesis, structures, and functions. Prog Lipid Res. 2022 Apr;86:101165.

- Bailes JE, Abusuwwa R, Arshad M, Chowdhry SA, Schleicher D, Hempeck N et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in severe brain trauma: case for a large multicenter trial. J Neurosurg. 2020 Aug 1;133(2):598-602.

- Lewis MD. When Brains Collide: What Every Athlete and Parent Should Know about the Prevention and Treatment of Concussion and Head Injuries: Lioncrest Publishing; 2016.

- Bailes JE, Abusuwwa R, Arshad M, Chowdhry SA, Schleicher D, Hempeck N et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in severe brain trauma: case for a large multicenter trial. J Neurosurg. 2020 May 15:1-5.

- Cockbain AJ, Toogood GJ, Hull MA. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for the treatment and prevention of colorectal cancer. Gut. Jan;61(1):135-49.

- Freitas RDS, Campos MM. Protective Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Cancer-Related Complications. Nutrients. 2019 Apr 26;11(5).

- D'Eliseo D, Velotti F. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Cancer Cell Cytotoxicity: Implications for Multi-Targeted Cancer Therapy. J Clin Med. 2016 Jan 26;5(2).

- Patel V, Li YN, Benhamou LRE, Park HG, Raleigh M, Brenna JT et al. High dose ω3 eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid block, whereas ω6 arachidonic acid accelerates, MYCN-driven tumorigenesis in vivo. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17(3):362.

- Sheeter DA, Garza S, Park HG, Benhamou LE, Badi NR, Espinosa EC et al. Unsaturated Fatty Acid Synthesis Is Associated with Worse Survival and Is Differentially Regulated by MYCN and Tumor Suppressor microRNAs in Neuroblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Apr 21;16(8).

- Wang D, Dubois RN. Eicosanoids and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010 Mar;10(3):181-93.

- Larsson SC, Kumlin M, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Wolk A. Dietary long-chain n-3 fatty acids for the prevention of cancer: a review of potential mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Jun;79(6):935-45.

- Sun G, Li YN, Davies JR, Block RC, Kothapalli KS, Brenna JT et al. Fatty acid desaturase insertion-deletion polymorphism rs66698963 predicts colorectal polyp prevention by the n-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid: a secondary analysis of the seAFOod polyp prevention trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024 Aug;120(2):360-8.

- Spector AA, Hoak JC, Fry GL, Denning GM, Stoll LL, Smith JB. Effect of fatty acid modification on prostacyclin production by cultured human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1980 May;65(5):1003-12.

- Palombo JD, Bistrian BR, Fechner KD, Blackburn GL, Forse RA. Rapid incorporation of fish or olive oil fatty acids into rat hepatic sinusoidal cell phospholipids after continuous enteral feeding during endotoxemia. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993 May;57(5):643-9.

- Chiu CY, Smyl C, Dogan I, Rothe M, Weylandt KH. Quantitative Profiling of Hydroxy Lipid Metabolites in Mouse Organs Reveals Distinct Lipidomic Profiles and Modifications Due to Elevated n-3 Fatty Acid Levels. Biology (Basel). 2017 Feb 4;6(1).

- Morin C, Sirois M, Echave V, Rizcallah E, Rousseau E. Relaxing effects of 17(18)-EpETE on arterial and airway smooth muscles in human lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009 Jan;296(1):L130-9.

- Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007 Oct;7(10):763-77.

- Johnsen JI, Lindskog M, Ponthan F, Pettersen I, Elfman L, Orrego A et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 is expressed in neuroblastoma, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs induce apoptosis and inhibit tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 2004 Oct 15;64(20):7210-5.

- Larsson K, Kock A, Idborg H, Arsenian Henriksson M, Martinsson T, Johnsen JI et al. COX/mPGES-1/PGE2 pathway depicts an inflammatory-dependent high-risk neuroblastoma subset. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Jun 30;112(26):8070-5.

- Hou R, Yu Y, Jiang J. Prostaglandin E2 in neuroblastoma: Targeting synthesis or signaling? Biomed Pharmacother. 2022 Dec;156:113966.

- Brenna JT, Kothapalli KSD. New understandings of the pathway of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 2022 Mar 1;25(2):60-6.

- Kothapalli KSD, Park HG, Kothapalli NSL, Brenna JT. FADS2 function at the major cancer hotspot 11q13 locus alters fatty acid metabolism in cancer. Prog Lipid Res. 2023 Aug 18;92:101242.

- Rasmuson A, Kock A, Fuskevag OM, Kruspig B, Simon-Santamaria J, Gogvadze V et al. Autocrine prostaglandin E2 signaling promotes tumor cell survival and proliferation in childhood neuroblastoma. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29331.

- Rauzi F, Kirkby NS, Edin ML, Whiteford J, Zeldin DC, Mitchell JA et al. Aspirin inhibits the production of proangiogenic 15(S)-HETE by platelet cyclooxygenase-1. FASEB J. 2016 Dec;30(12):4256-66.

- Zhang G, Panigrahy D, Mahakian LM, Yang J, Liu JY, Stephen Lee KS et al. Epoxy metabolites of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) inhibit angiogenesis, tumor growth, and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Apr 16;110(16):6530-5.

- Gleissman H, Yang R, Martinod K, Lindskog M, Serhan CN, Johnsen JI et al. Docosahexaenoic acid metabolome in neural tumors: identification of cytotoxic intermediates. FASEB J. 2010 Mar;24(3):906-15.

- Carlson LM, Rasmuson A, Idborg H, Segerstrom L, Jakobsson PJ, Sveinbjornsson B et al. Low-dose aspirin delays an inflammatory tumor progression in vivo in a transgenic mouse model of neuroblastoma. Carcinogenesis. 2013 May;34(5):1081-8.

- Panigrahy D, Edin ML, Lee CR, Huang S, Bielenberg DR, Butterfield CE et al. Epoxyeicosanoids stimulate multiorgan metastasis and tumor dormancy escape in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012 Jan;122(1):178-91.

- Wang D, Fu L, Ning W, Guo L, Sun X, Dey SK et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta promotes colonic inflammation and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 May 13;111(19):7084-9.

- Honn KV, Tang DG, Gao X, Butovich IA, Liu B, Timar J et al. 12-lipoxygenases and 12(S)-HETE: role in cancer metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1994 Dec;13(3-4):365-96.

- Pogash TJ, El-Bayoumy K, Amin S, Gowda K, de Cicco RL, Barton M et al. Oxidized derivative of docosahexaenoic acid preferentially inhibit cell proliferation in triple negative over luminal breast cancer cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2015 Feb;51(2):121-7.

- Serhan CN, Dalli J, Karamnov S, Choi A, Park CK, Xu ZZ et al. Macrophage proresolving mediator maresin 1 stimulates tissue regeneration and controls pain. FASEB J. 2012 Apr;26(4):1755-65.

- Rossner P, Jr., Gammon MD, Terry MB, Agrawal M, Zhang FF, Teitelbaum SL et al. Relationship between urinary 15-F2t-isoprostane and 8-oxodeoxyguanosine levels and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Apr;15(4):639-44.

- Hao H, Liu M, Wu P, Cai L, Tang K, Yi P et al. Lipoxin A4 and its analog suppress hepatocellular carcinoma via remodeling tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2011 Oct 1;309(1):85-94.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).