1. Introduction

The internet was initially designed for simplicity and open data exchange among academic institutions, not security [

1,

2]. Its rapid public adoption, however, revealed a critical need for confidentiality as industries began transmitting sensitive financial and personal data [

3,

4,

5,

6]. This demand for secure channels led to the development of proprietary protocols like Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) [

7]. To create a unified, robust standard, the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol was established to provide server authentication and encrypted communication for a wide range of internet services [

8].

This paper builds upon the foundational work in [

9,

10], which proposed a block cipher based on Pythagorean Triples. We extend this concept by integrating the idea proposed in said papers into the well tested Feistel architecture and conducting a comprehensive analysis of the cipher and integrating it into a secure communication protocol. The proposed protocol is architecturally modeled after TLS 1.2 [

8] and is designed to evaluate the cipher’s practical usability. It serves as a standalone solution for securing inter-organizational communications in environments where traditional Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) are infeasible due to compatibility and firmware constraints.

The increasing volume of sensitive information transmitted online has prompted stringent data privacy legislation. Concurrently, the growing sophistication of cyber threats necessitates robust security for a diverse ecosystem of devices. This creates a critical demand for a lightweight security protocol capable of operating on resource-constrained platforms, including microcontrollers, laboratory equipment, and IoT devices.

2. Background

Early cryptographic protocols for securing connections were often hindered by proprietary interests and patents. The first major effort to establish a unified, cross-platform standard was the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) protocol, which later evolved into Transport Layer Security (TLS). While initial versions suffered from significant vulnerabilities, the iterative development of TLS has systematically mitigated these attacks. The modern TLS protocol now reliably provides secure communications between cooperating clients and servers, built upon the cryptographic primitives detailed in the following subsections.

2.1. One Way Deterministic Hash Functions

A cryptographic hash function deterministically maps arbitrary-length input to a fixed-size output (a digest). To be cryptographically secure, it must satisfy three core properties: pre-image resistance (infeasible to reverse the output), second pre-image resistance (infeasible to find a different input with the same hash), and collision resistance (infeasible to find any two colliding inputs) [

11]. Furthermore, its output must be pseudo-random and exhibit the avalanche effect, where a small input change produces a drastically different output.

These properties make hash functions vital for security. They are primarily used for data integrity verification and form the foundation of efficient digital signature schemes, where a message’s hash is signed instead of the message itself [

12].

Hash functions are crucial in other applications including password storage, blockchain technology, cryptocurrencies and proof-of-work systems providing a trusted, efficient, and secure method for fingerprinting digital data [

13].

2.2. Hash Based Message Authentication Codes

this too pls A Hash-based Message Authentication Code (HMAC) is a cryptographic mechanism used to verify both the integrity and authenticity of a message [

14]. It ensures that a message has not been tampered with and originated from a party possessing the correct secret key.

An HMAC is constructed by combining a cryptographic hash function with a secret key. The algorithm processes the key and the message together in a specific nested structure, making it resistant to various cryptanalytic attacks. This makes HMACs widely used in security protocols like TLS, IPSec, and API authentication to protect data in transit [

14]. The steps to produce and verify an HMAC are as follows:

Generate: Sender uses a secret key and the message to create an HMAC tag via a cryptographic hash function.

Transmit: The original message and the HMAC tag are sent to the receiver.

Verify: Receiver recalculates the HMAC using the received message and the shared key. If it matches the sent tag, the message is authentic and unaltered.

The nested HMAC structure

is designed to provably protect against length-extension attacks [

14] - a vulnerability of simple

constructions - while maintaining security even if the underlying hash function has minor weaknesses.

BLAKE2 [

15] is a performance oriented cryptographic hash function due to simplified rounds and optimized implementation. Unlike HMAC, which is a construction that uses a hash function, BLAKE2 includes a built-in keying mechanism (BLAKE2 MAC), allowing secure MAC generation without needing the HMAC wrapper, making it simpler and potentially faster than standard algorithms for authenticated hashing.

2.3. Symmetric Key Encryption

Symmetric encryption, also called

private key cryptography, is one of the oldest and most widely used forms of encryption, using only one key for both encryption and decryption [

16,

17]. The sender uses the key to transform plaintext into ciphertext, and the receiver applies the same key to recover the original plaintext. Because the process is computationally efficient, symmetric encryption is especially suitable for protecting large amounts of data in real time, such as securing internet traffic, files, or communications.

The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) [

17] is an example of a symmetric block cipher optimized for hardware efficiency and is the global benchmark for security. ChaCha20 [

18] is a stream cipher designed for fast, secure software performance, particularly in mobile and web protocols, serving as a common alternative to AES.

A block cipher encrypts fixed-size blocks of data at a time, while a stream cipher encrypts data bit-by-bit or byte-by-byte by generating a keystream that is combined (typically via XOR) with the plaintext [

16].

Modes of operation define how a block cipher (like AES) is applied to encrypt data longer than a single block [

19]. Certain modes, such as Counter (CTR), effectively convert a block cipher into a stream cipher. In CTR mode, the block cipher is used to encrypt a sequential counter value, producing a keystream. This keystream is then XORed with the plaintext, enabling streaming encryption without padding requirements.

Symmetric encryption depends heavily on secure key distribution, which is why it is usually combined with asymmetric encryption for initial key exchange [

8].

2.4. Public Key Cryptography

Asymmetric encryption, introduced in the 1970s, solved the key distribution problem of symmetric systems by using a key pair: a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption [

20,

21]. This foundation enables secure key exchange over public channels and forms the basis for digital signatures.

RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) was one of the first widely used asymmetric algorithms, RSA’s security relies on the difficulty of factoring large primes [

20]. It remains crucial for HTTPS, digital certificates, and email encryption.

ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography) provides security equivalent to RSA but with significantly smaller key sizes, offering greater efficiency [

22]. It is essential in modern TLS, blockchain systems, and mobile applications.

Asymmetric encryption revolutionized secure communication by solving the problem of key distribution and enabling digital identity verification [

23]. While slower than symmetric encryption, it works hand-in-hand with symmetric methods: public key cryptography establishes secure connections, and symmetric algorithms handle the bulk of data transfer[

8,

24].

2.5. Key Establishment

Key establishment is a fundamental cryptographic process enabling two parties to securely derive a shared secret over an insecure channel. The Diffie-Hellman (DH) key exchange protocol, introduced in 1976, was the first practical method to solve this problem and revolutionized secure communications [

21].

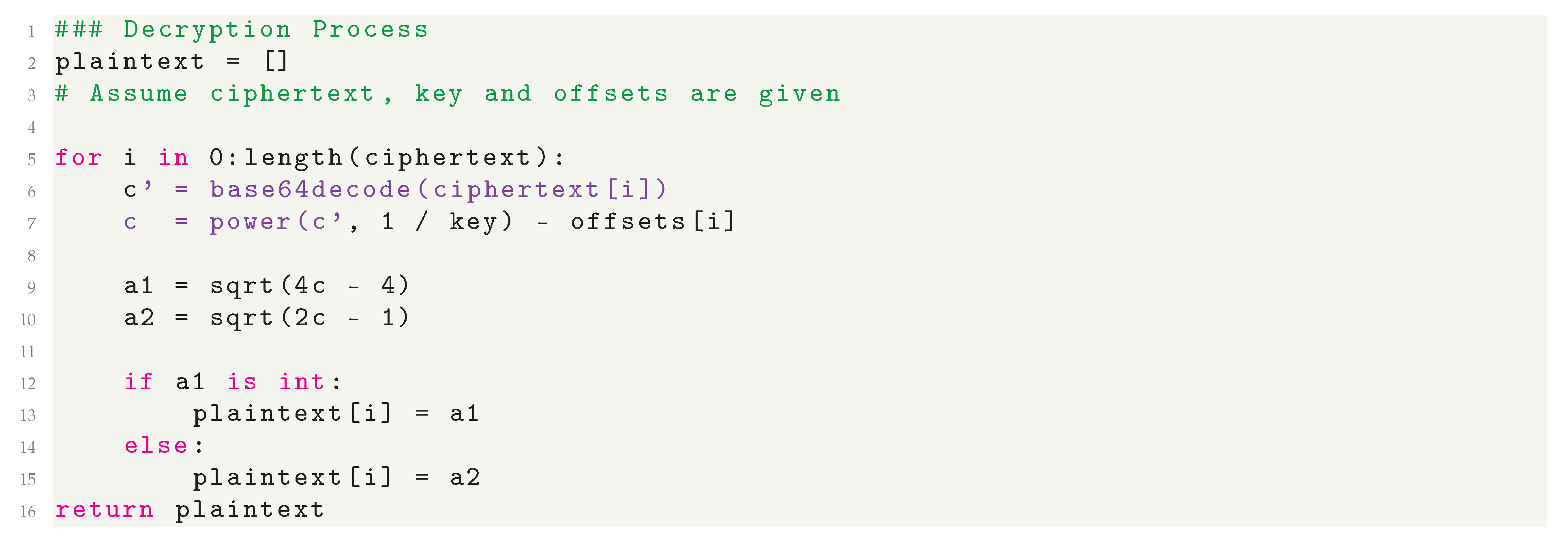

Using the mathematics of modular exponentiation in cyclic groups, DH allows two parties to independently generate public-private key pairs, exchange public keys, and compute an identical shared secret without ever transmitting it.

While DH itself provides no authentication and is vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks, it forms the basis for authenticated key exchange protocols like the Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) used in modern TLS [

25,

26]. Its core idea remains foundational to asymmetric cryptography.

Figure 1 displays the process of key exchange using Diffie Hellman Key Exchange.

2.6. Digital Signatures

A digital signature is a cryptographic mechanism that provides authentication, integrity, and non-repudiation for digital messages or documents [

20]. It operates using asymmetric cryptography: the signer generates a signature on a message with their private key, and any recipient can verify this signature using the signer’s public key. A digital signature verifies the identity of the signer by cryptographically binding the signature to both the document and the signer’s unique private key, thereby confirming that the message was created by the holder of the private key and has not been altered since signing.

Crucially, hash functions play an essential role in this process: instead of signing the entire message (which can be large), a cryptographic hash of the message is computed first, and the signature is generated on this fixed-size digest. This approach improves efficiency and security, ensuring the signature process remains robust even for large files. Digital signatures form the basis for secure protocols like TLS, code signing, and digital certificates, enabling trust in electronic transactions [

20,

27].

Digital signatures are fundamental to the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol, primarily used during the handshake phase to authenticate the server (and optionally the client) and to ensure the integrity of the key exchange. The server proves its identity by sending a digital certificate, which contains a public key and identity information signed by a trusted Certificate Authority (CA) [

8,

28].

2.7. Certificates, PKI And Chain Of Trust

A digital certificate is an electronic document that binds a public key to a specific identity (e.g., a person, organization, or website). It acts as a digital passport, enabling trust in asymmetric cryptography by verifying that a public key belongs to the claimed entity. Certificates contain information such as the subject’s name, the public key, the issuing Certificate Authority (CA), a digital signature from the CA, and validity dates. This structure allows relying parties to authenticate communicating peers and establish secure channels. The most widely used standard for certificates is X.509, which defines their format and is foundational to secure web browsing (HTTPS), email encryption (S/MIME), and many other security protocols [

28,

29].

A Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) is a framework of policies, technologies, and procedures that enables the secure creation, management, distribution, and revocation of digital certificates. Its primary purpose is to bind public keys to respective identities of entities (e.g., persons, organizations, devices) in a trustworthy manner. This trust is established through a hierarchical structure involving Certificate Authorities (CAs), which issue and sign digital certificates, and Registration Authorities (RAs), which verify the identity of certificate applicants. The core components of PKI include digital certificates, public-key cryptography, and trust models that together form a scalable system for authentication and encryption across untrusted networks such as the internet [

28,

30].

The security of PKI relies fundamentally on the chain of trust. This cryptographic trust model is a hierarchical sequence of certificates, where each certificate is signed by the private key of the entity that issued it. The chain begins with a Root Certificate Authority (root CA), which is a trusted, self-signed entity. The root CA issues certificates to intermediate CAs, which in turn may issue further intermediate certificates or end-entity certificates. To validate a certificate, one must verify the digital signature of each certificate in the chain using the public key of the issuer, recursively, until reaching a root CA that is explicitly trusted by the verifier (e.g., pre-installed in a trust store). This delegation of trust allows for scalable security without requiring every party to directly trust every issuer, and it ensures that compromise of an intermediate CA does not necessarily compromise the entire system, provided the root remains secure [

31,

32].

A self-signed certificate is a digital certificate that is signed by its own creator rather than by a trusted third-party CA. While they do not provide authentication in the traditional trust model of the public web-as any entity can generate one without independent verification-they are invaluable in controlled or private environments. Their primary need arises in situations where establishing a full PKI is impractical or unnecessary, such as in internal development, testing, prototyping or within closed systems where the participants can manually establish trust. Common applications include securing internal network services, encrypting data in transit for pre-production software, and creating temporary secure channels where the primary requirement is encryption and integrity rather than public trust. Their ease of generation and zero cost make them a practical tool for encryption and authentication in non-public contexts.

The main limitations of PKI and self-signed certificates include sole reliability on a centralized authority (CA) and challenges related to certificate revocations.

2.8. Transport Layer Security

The Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol is the foundational cryptographic protocol designed to provide secure communication over a computer network, most notably the internet. Its primary objectives are to ensure privacy (through encryption), data integrity (through message authentication codes), and authentication (via digital certificates and public key infrastructure) between two or more communicating applications.

TLS operates as a layer between a reliable transport protocol, such as TCP, and application-layer protocols like HTTP (becoming HTTPS), SMTP, and FTP, effectively shielding data from eavesdropping and tampering during transit. It has become the de facto standard for securing web traffic, online transactions, and sensitive data exchange, forming the backbone of trust for the modern internet economy [

8,

28].

The establishment of a secure TLS session is governed by the TLS handshake, a complex sub-protocol that negotiates the cryptographic parameters of the session. During this handshake, the client and server agree on a TLS version and a cipher suite (which specifies algorithms for key exchange, authentication, encryption, and integrity). A critical step involves authentication, where the server presents a digital certificate signed by a Certificate Authority (CA) to prove its identity; the client validates this certificate by verifying the CA’s digital signature against a pre-installed list of trusted root certificates, traversing the chain of trust. Following authentication, the parties use a key exchange algorithm (like Diffie-Hellman) to generate a shared secret key, from which the session keys for symmetric encryption and integrity checking are derived. This ensures that even if the key exchange is intercepted, the session keys cannot be computed by an adversary, providing forward secrecy [

28,

33].

Since its inception as Secure Sockets Layer (SSL), the protocol has undergone significant evolution to address cryptographic weaknesses and enhance performance. TLS 1.3, the latest version, represents a major overhaul by removing support for obsolete cryptographic algorithms (e.g., static RSA key exchange, SHA-1), mandating forward secrecy for all connections, and streamlining the handshake to reduce latency from two round trips to one in most cases. These improvements not only bolster security by eliminating known vulnerabilities but also increase efficiency, making encrypted communication faster than ever. Despite its robustness, the security of TLS is contingent on correct implementation, secure configuration, and the trustworthiness of the underlying Certificate Authorities, requiring continuous vigilance from the security community [

34,

35].

2.9. Dolev-Yao Adversary Modeling

The Dolev-Yao model, introduced by Danny Dolev and Andrew Yao in 1983, is a seminal formal framework for analyzing the security of cryptographic protocols against an active network adversary [

36]. This model abstracts cryptographic operations as algebraic term manipulations, treating encryption and decryption as perfect black-box functions-meaning the adversary cannot break the cryptography mathematically but can misuse it if given the proper keys. The adversary in this model possesses complete control over the communication network: it can eavesdrop on, intercept, block, alter, forge, and replay any message transmitted between honest parties. This makes the Dolev-Yao adversary exceptionally powerful, as it represents a worst-case scenario where the attacker mediates all communications, requiring protocols to be designed to resist such intensive manipulation [

37].

The primary significance of the Dolev-Yao model lies in its application to formal verification of security protocols. By defining a precise adversarial capabilities framework, it enables researchers to mathematically prove whether a protocol achieves its security goals-such as secrecy, authentication, and integrity - even under extreme attack conditions [

38]. This model has become the gold standard for reasoning about protocol security and has influenced the design and analysis of countless real-world systems, including authentication and key-exchange protocols like TLS and SSH [

36]. While the model’s assumptions of perfect cryptography and omnipotent network control are theoretical simplifications, they provide a rigorous foundation for identifying logical flaws that could be exploited in practice, ensuring that protocols are resilient not just to passive eavesdropping but to active manipulation [

37].

2.10. Applicational Tools

2.10.1. JSON

JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) is a lightweight, text-based, language-independent data interchange format. It was derived from the object literals of the JavaScript programming language but is now supported by a vast majority of modern programming languages through built-in or standard libraries. JSON’s syntax is built on two universal data structures: a collection of name/value pairs (often realized as an object, record, or dictionary) and an ordered list of values (an array or list). Its simplicity, human-readability, and ease of parsing compared to alternatives like XML led to its rapid adoption for serializing and transmitting structured data over networks, most notably in web APIs[

39]. It is formally specified in RFC 8259, which defines its grammar and interoperability standards [

39].

2.10.2. Base64 Encoding

Base64 encoding is a binary-to-text encoding scheme that represents binary data in an ASCII string format [

40]. It is primarily used when transmitting binary data over channels that only reliably support textual data, such as email (MIME) or JSON-based web services.

The core principle of Base64 is to take input binary data, divide it into 6-bit groups, and map each group to one of 64 printable ASCII characters [

40]. The standard Base64 alphabet includes uppercase letters (A–Z), lowercase letters (a–z), digits (0–9), and two special characters (+ and /). Padding with the = character ensures that the encoded string length is always a multiple of four characters, which is crucial for unambiguous decoding [

40].

2.10.3. Python Sockets

The Python socket library provides a low-level interface to the Berkeley sockets API, the standard for network communication on the internet [

41]. It allows Python programs to create network clients and servers by enabling communication between processes, either on the same machine or across a network, using various protocols like TCP (reliable, connection-oriented) and UDP (unreliable, connectionless). The library offers functions to create sockets, bind them to addresses, establish connections, and send or receive data. While powerful, it operates at a fundamental level, requiring the developer to manually handle aspects like data serialization, protocol design, and connection management, making it foundational for implementing custom network protocols and services.

Main functionality includes constructing a socket (client/server), binding (server), listening (server), accepting connections (server), connecting (client), sending and receiving (client/server). For the purposes of this paper, a socket is defined a pair (IP address, host) as both values are required for differentiating between network applications.

2.11. Multi Layered Encryption Using Pythagorean Triples

Introduced by Voloch N. and N. B. in [

9,

10], this algorithm is the focus of this paper.

Pythagorean Triples are an ordered pair of

which satisfy the following equation

. Given one perpendicular

a two formulas exist to derive the other perpendicular and the hypotenuse, one developed by Pythagoras himself for odd values of

a and one by Plato some 200 years after Pythagoras for even values of

a. The formulae are given below:

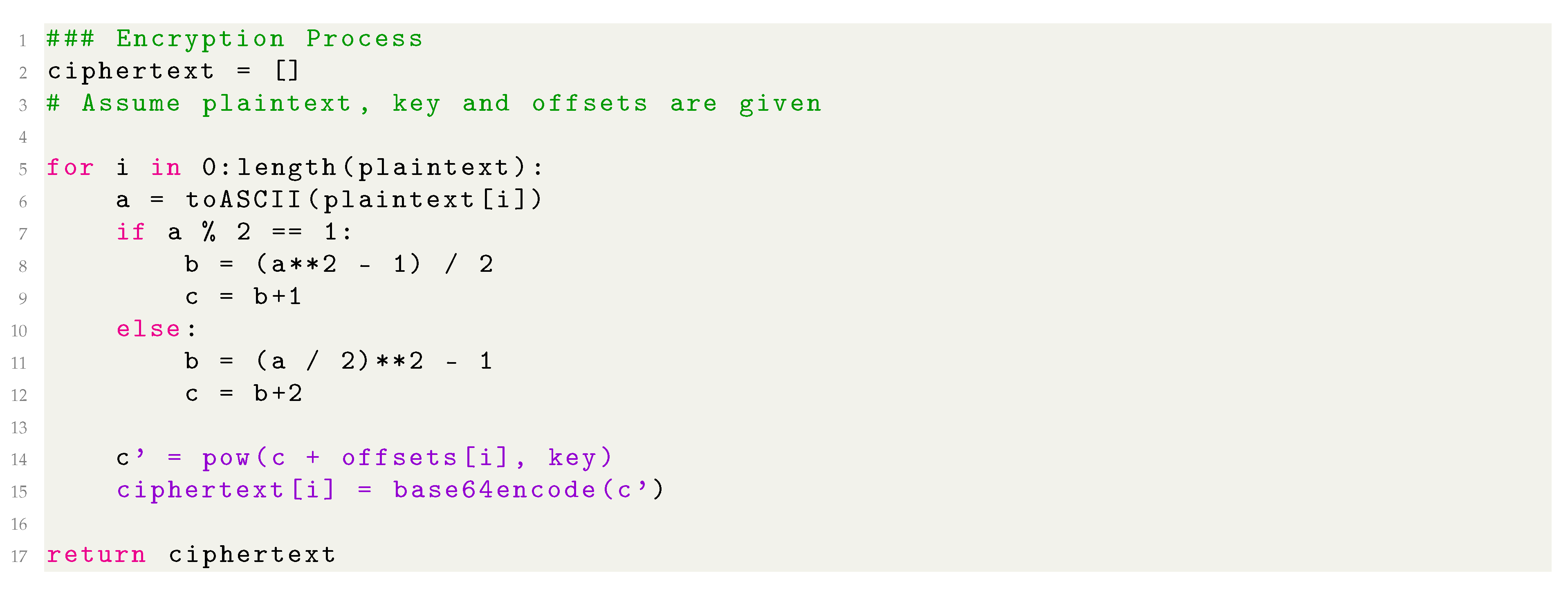

The approach proposed in [

9,

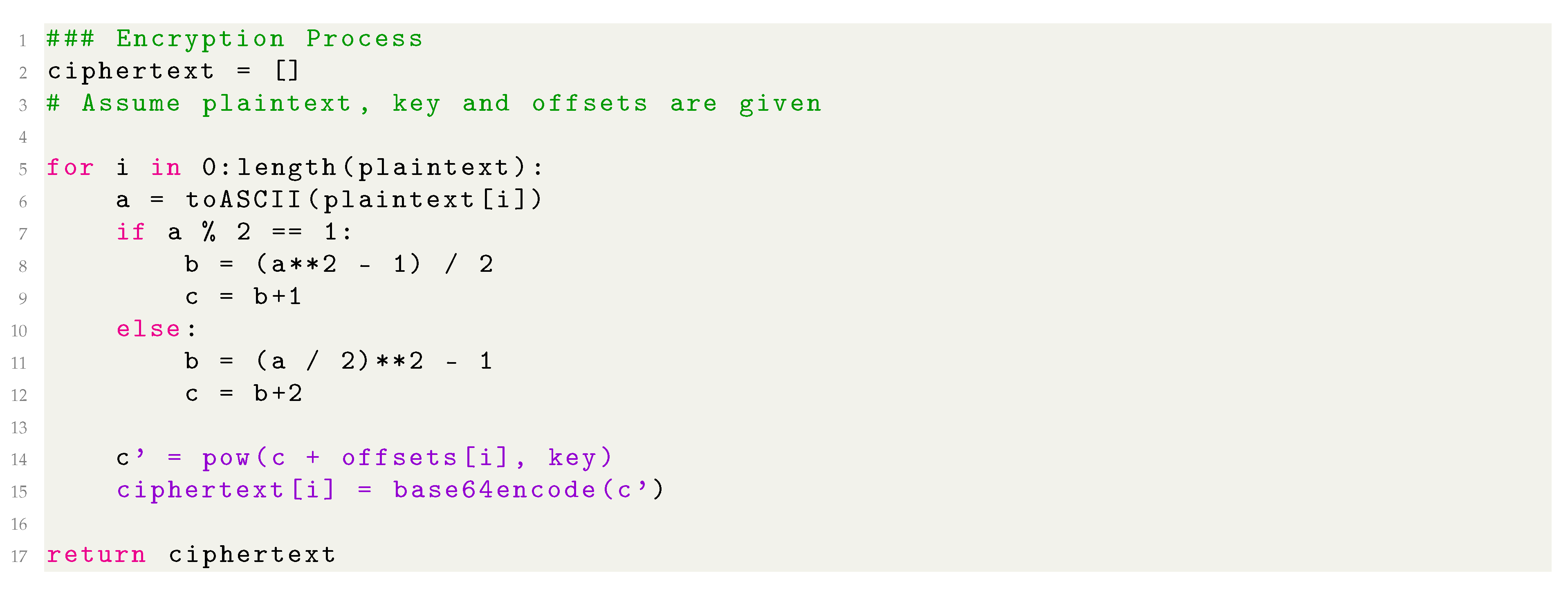

10] consists of intertwined encryption by raising the sum of the hypotenuse and an offset to the power of the key and returning the Base64 encoding of the underlying result, as shown below:

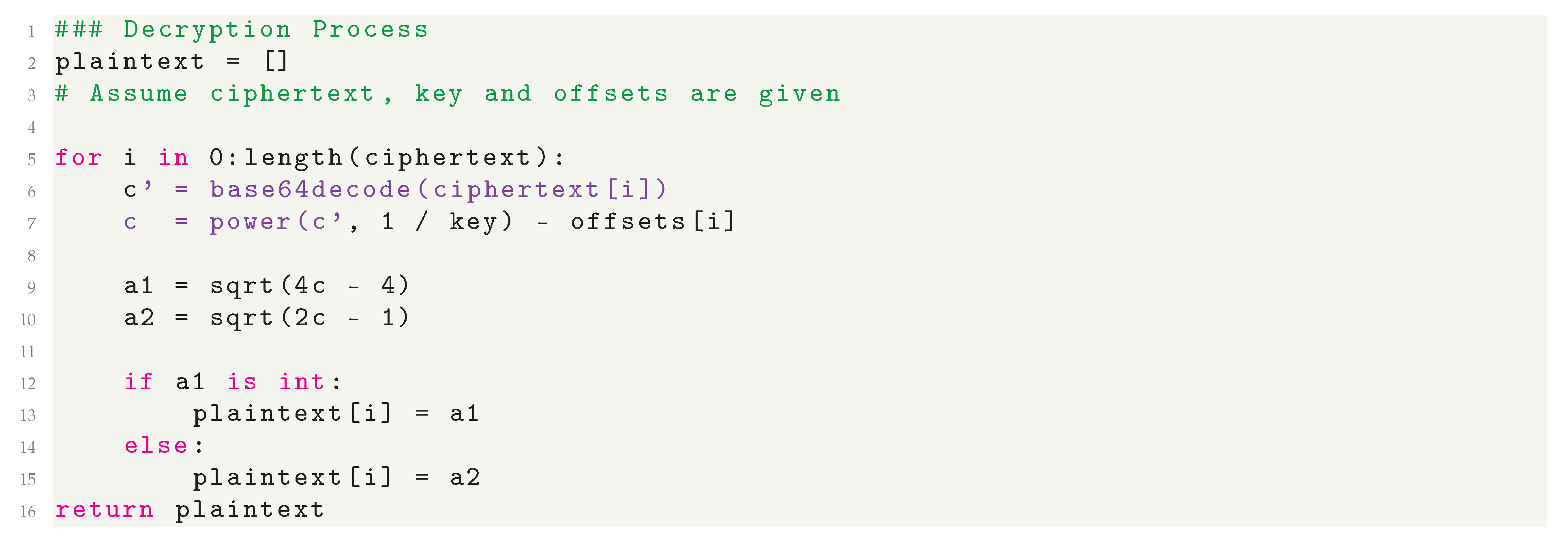

|

Listing 1. Encryption Pseudocode |

|

|

Listing 2. Decryption Pseudocode |

|

The algorithm is characterized by its non linearity, especially after adding the key and raising to the power of the key.

3. Methodology

3.1. Purpose

The primary contribution of this paper is the specification and security analysis of a new secure communication protocol. We formally define the protocol, verify its functional correctness, and provide a security proof. Furthermore, we conduct an empirical analysis to evaluate the performance and robustness of the Pythagorean Triples Encryption (PTE) cipher within this operational context.

The primary purpose of the proposed protocol is to enable secure inter-organizational communication, ensuring that information exchanged between entities remains protected from unauthorized access or manipulation. The protocol is designed to guarantee the fundamental properties of secure communication - secrecy, authentication, and integrity - thereby addressing the critical requirements of confidentiality and trust in distributed systems. By establishing these guarantees, the framework facilitates reliable communication between clients and servers, which is essential in environments where sensitive or mission-critical data is transferred.

The protocol highlights the practical application of a novel Pythagorean Triplet based encryption algorithm proposed in [

9,

10]. This protocol serves as a foundation for exploring alternative mathematical structures in secure protocol design. An additional property of the proposed protocol is the ease of configuration for both server and client systems. The proposed protocol will be evaluated on the two essential pillars of correctness and security.

3.2. Pythagorean Triples Encryption

The algorithm proposed in

Section 2.11 has the following characteristics:

Non Linearity: Derivation of the Pythagorean Triplet and raising to the power of the key are non-linear and can challenge linear cryptanalysis efforts.

Inherent Support For IVs: The algorithm inherently supports Initialization Vectors because of the use of offsets. Also, addition before the exponentiation guarantees non linearity towards the offsets/IV.

Output Is Different Than Input: The input to the system, both key and plaintext can be represented as an 8-bit number. However, due to the exponentiation the output is not bounded to the max value 255, causing representation problems.

Implementation Discrepancies: Due to the exponentiation, even bounded values can explode in size. In some cases, decoding resulting large numbers failed resulting in failure of decryption, affecting the functional accuracy of the algorithm.

In light of the above characteristics, a formal specification for encryption is needed, one which is characterized by the inherent support for salting [

42] and non-linearity, but also one which guarantees the output to be 8-bit unsigned integers for every 8-bit input unsigned integer, ie. the size of the output is equal to that of the input.

An optimal solution for the above problem is the adaptation of the Pythagorean Triple Encryption algorithm for use with an addition-rotation-xor (ARX) Feistel Cipher structure [

43,

44]. This adaptation not only answers

all of the above statements but also improves security as:

We propose the following 128-bit Pythagorean ARX (P-ARX) structure. Inspired by TEA, a lightweight cipher using a 128-bit key, our design extends the block size to 128 bits for enhanced security. [

46].

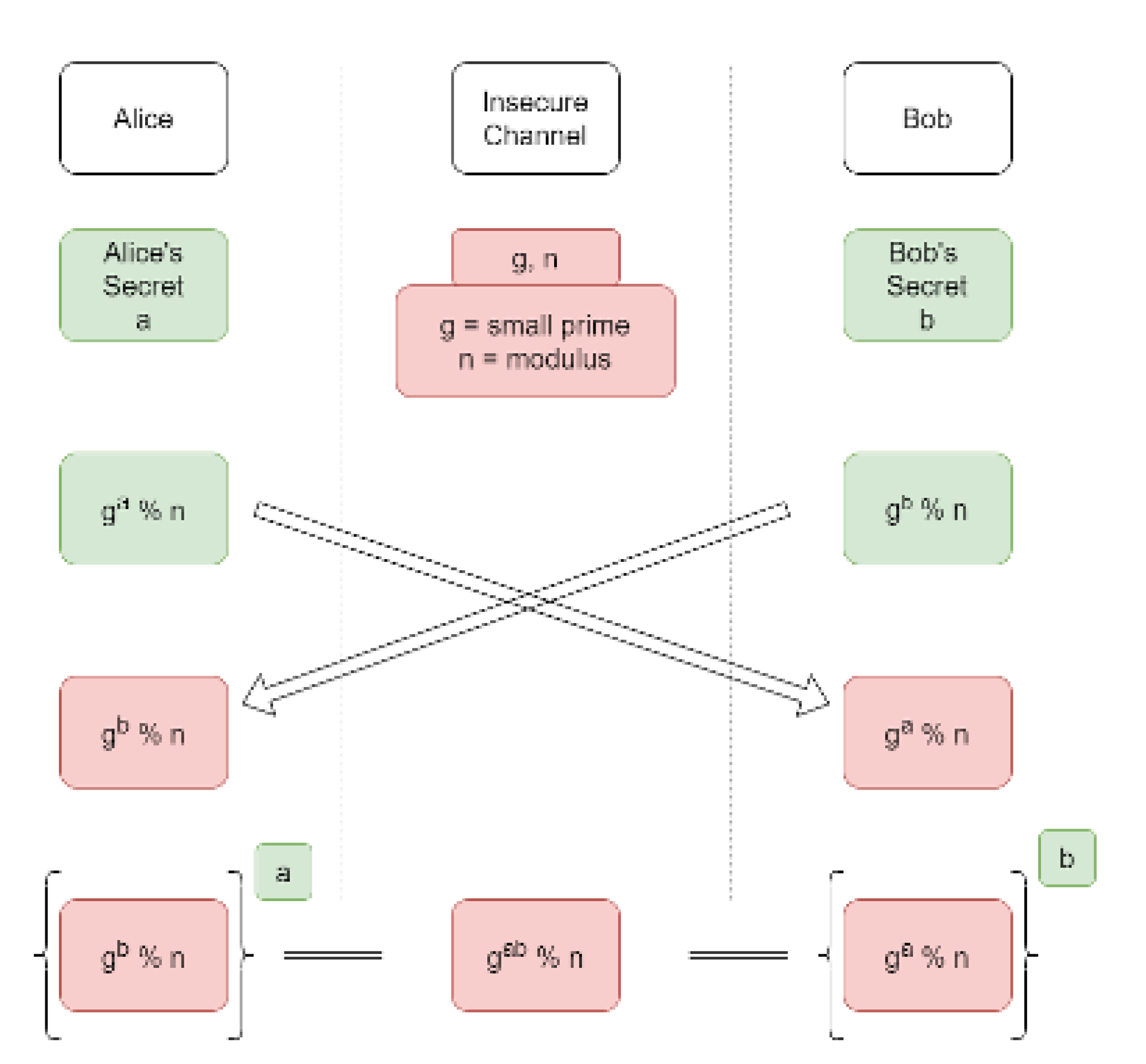

The structure, as can be seen in

Figure 2, consists of simple operations such as rotation and xor and the focus of this paper, Pythagorean Triplet Encryption.

The side

is branched into three branches, two of which are non-linear, and XORed back into one branch which is XORed with the other part. Once, it is rotated by 4 bits to the left and encrypted byte-wise using the

f function using the first half of the key. The second time is similar, just that

is rotated by 5 bits to the right and encrypted with the other half. The third time incorporates the IV. This half "round" of encryption is repeated, this time with flipped keys and on

, resulting in one full round of encryption. Like TEA, we suggest 32 full encryption rounds for best security-performance tradeoff. The

f function is defined as follows:

Note that

denotes the hypotenuse of the Pythagorean Triplet of

a,

c, which can be calculated using the formulae in

Section 2.11. Also note that the

f function has two important attributes - not only is it bounded to the range

but it also constitutes as non-linear substitution which is crucial for diffusion in modern encryption algorithms.

Thus, one full encryption round is defined as:

Where denotes byte-wise application of f as described above, XOR precedes addition and denotes half of the initialization vector. Note that XOR precedes addition in the above equation - parenthesis were omitted for compatibility with both single and double column templates.

Also note that are 64-bit blocks of the original key and ciphertext, and the f function is defined on 8-bit blocks, therefore the need for byte-wise application arises. The red o-plus symbols denote addition modulo as is the size of in bits, which is another non-linear operation.

3.3. Security And Compatibility Goals

3.3.1. Three Pillars Of Security

The proposed protocol is designed to ensure three core security properties: confidentiality, authentication, and integrity. Confidentiality is achieved by encrypting the bi-directional communication session between the client and server, ensuring that only parties possessing the correct encryption key can decipher the messages. While an adversary may intercept the encrypted communication, they cannot decipher its contents assuming the keys are handled securely and the endpoints are not compromised [

47].

Authentication is managed through the use of cryptographic credentials. The server presents a certificate signed by a mutually trusted Certificate Authority (CA), allowing the client to verify the server’s identity [

28]. The protocol also supports client authentication, though its primary focus is on authenticating the server. It is important to note that this mechanism verifies the presented credentials are valid, not that the server’s identity is the one the user intended to contact; it cannot prevent phishing attacks where a user is tricked into connecting to a server with valid credentials for a malicious domain.

Finally, integrity is guaranteed via Hash-Based Message Authentication Codes (HMACs) [

48]. This mechanism ensures that messages exchanged between the client and server cannot be altered, replayed, or manipulated during transmission without detection. Assuming the integrity key remains secret, any attempt to forge or modify a message will be detected, thereby preserving the accuracy and trustworthiness of the entire conversation. The security of HMAC, and thus these guarantees, relies on the security of the underlying cryptographic hash function [

49]. Assuming the integrity key remains secret, any attempt to forge or modify a message will be detected with negligible probability, thereby preserving the accuracy and trustworthiness of the entire conversation.

3.3.2. Verification Of Transaction

The proposed protocol provides irrefutability (non-repudiation), ensuring a party cannot deny participating in a transaction, which is critical for financial, contractual, and document-sharing systems [

51]. This guarantee incurs a minimal performance overhead. Furthermore, to enhance production reliability, the protocol generates cryptographically secure unique identifiers for subsystems, preventing the leakage of both ephemeral and constant secrets.

The ever increasing demand for applications which facilitate sensitive information and transactions makes this protocol an attractive tool for security and privacy based applications

3.3.3. Backward Secrecy

Backward secrecy is an essential feature for modern communication, which dictates that compromise of current credentials does not increase the ease of compromise of previous communications [

28].

The proposed protocol, if implemented with the correct general cryptographic guidelines, fully guarantees backward secrecy by the use of secure key derivation functions such as keyed hashes of the Blake2 family [

15].

3.3.4. Resistance To Known Attacks

The proposed protocol is designed to be resilient against the following attacks:

Impersonation/spoofing attacks, man-in-the-middle attacks, secure connection stripping, connection/parameter downgrade attacks and replay attacks [

21,

28,

36,

37,

50,

51,

52]. A deeper analysis will be presented in

Section 3.9.6.

3.3.5. Error Detection And Handling

The protocol is designed to be able to detect the following types of attacker manipulation [

28,

36]: The protocol is engineered to actively detect and prevent attacker manipulation through the following mechanisms:

Handshake Manipulation: The last two handshake messages include a cryptographic summary of the entire negotiation. Any alteration of client-hello or server-hello parameters causes a signature verification failure, immediately terminating the connection.

Handshake Packet Blocking: A built-in timeout counter for the handshake phase ensures that connection failures - whether from network issues or intentional blocking-are detected promptly, with both parties safely terminating the session.

Data Manipulation: All data packets are protected by an HMAC. Any tampering with packet contents is detected upon verification, triggering an immediate connection termination. This guarantees message integrity throughout the session.

Data Packet Blocking: To counter silent failures, the protocol mandates a final summary exchange to formally conclude a transaction. If either party does not receive this confirmation, the entire transaction is considered void, preventing state desynchronization.

3.3.6. Data Compatibility

The proposed protocol will structure necessary information in a key-value format using JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) [

39]. Both JSON and modern application protocols like HTTP need data to be encoded as text; JSON supports UTF-8 but older protocols do not. Therefore, the protocol will encode non-text data into Base64 strings [

40]. It is strongly recommended to also encode text data to Base64 before sending in order to maximize compatibility with older infrastructure which does not support Unicode.

3.4. Protocol Overview

To ensure all security objectives are met, the protocol divides the client-server connection into two distinct phases: a Handshake to establish an authenticated and encrypted channel, and Data Transfer to convey the application data securely and reliably [

28,

36,

37]. Additionally, a smaller exchange is facilitated at the end of the transaction according to client-server needs in order to generate a cryptographically valid summary for the transaction if needed, for irrefutability.

3.4.1. Handshake

The handshake is a four-message exchange that negotiates the cryptographic parameters for the secure session - such as encryption keys, Diffie-Hellman public values, and random Number Used Once (nonces) - and authenticates the server and, optionally, the client .

The handshake protocol proceeds as follows:

Client Hello: The client initiates the connection by sending a Client Hello message, containing a client-generated random nonce and a unique connection identifier.

Server Hello: The server responds with a Server Hello message, presenting its certificate for authentication, its Diffie-Hellman public key, and a signature over all handshake parameters to prove possession of the corresponding private key. This message may also signal a request for client authentication.

Client Handshake Finish: The client verifies the server’s certificate and signature. Upon successful validation, it generates a pre-master secret and sends its own Diffie-Hellman public key to the server. Optionally, it may include a random challenge for the server to prove real-time key ownership and, if requested, its own credentials for client authentication.

Server Handshake Finish: The server finalizes the handshake by responding to the client’s challenge (if present) and sending necessary acknowledgments. Upon completion, both parties derive the session keys.

3.4.2. Secure Data Transfer

Following a successful handshake, the data transfer phase commences. The underlying secure channel supports full or half-duplex communication, as dictated by the configuration of the transport-layer socket. The subsequent data transfer phase involves the exchange of packets containing encrypted payloads, Hash-based Message Authentication Codes (HMACs) for integrity, and timestamps.

The underlying information to be transferred is packaged in secure, structured JSON strings [

39]. The package starts with the Global ID for identification. Then, the message itself is encoded to a string using Base64 encoding [

40] and secured using an HMAC using a securely derived key from the pre-master secret. As principle, the HMAC should secure the message, Global ID and the timestamp in order to securely mitigate replay attacks. Note that client and server randoms are omitted as they affect the encryption and MAC keys, affecting the value of HMAC and capacitating the detection of replay attacks.

3.4.3. Bi-Consensual Termination Stage

Secure connection termination is critical to prevent replay, spoofing, and denial-of-service attacks . An improper closure can lead to state de-synchronization, where one party believes a transaction is complete while the other does not, violating core security principles.

To mitigate this, the protocol implements a bi-consensual termination phase. Both parties must explicitly acknowledge a termination message, ensuring a synchronized end state. Optionally, this phase can generate a cryptographic proof of the transaction, providing irrefutability (non-repudiation) if required.

3.5. Protocol Component Structure

3.5.1. Algorithms

This subsection elaborates on the various algorithm used in the proposed protocol and how they relate to the fields proposed in

Section 3.4.

For digital signatures, the reliable RSA-PSS [

53] was chosen with a key size of 2048 bits, mainly for its ease of use in cryptographic implementations - the SHA256 algorithm was the most versatile hash choice for digital signatures. For secure key exchange, the Diffie Hellman algorithm was chosen, which generates 2048-bit private keys, for the same reason as RSA-PSS. The certificates use the popular x.509 format [

28]. For calculating MACs, the keyed BLAKE-2B algorithm was chosen, as it converts integrity checking into a one-hash operation as compared to the two-hash HMAC. For encryption, the focus of this paper, the Pythagorean Triples Encryption ARX implementation was chosen, as described in sub

Section 3.2.

To adhere to stricter cryptographic standards, recommended practices such as salting in all its forms were incorporated. As stated in sub

Section 3.2, the Pythagorean Triples Encryption (PTE) supports a 128-bit IV field. BLAKE-2B, by design, supports secure keyed hashing and salting. RSA-PSS [

53] by definition incorporates random padding. Diffie Hellman is used in such a way that random keys are generated for every session.

Every message can be seen as a key-value pair, making the use of JSON optimal for structuring the messages internally. JSON’s specification is well defined [

54] and it features a rather simple, context-free language which can be used to determine whether a string is valid JSON or not in finite time [

54].

As JSON needs the internal objects to be serializable, all binary objects (excluding PEM encoded credentials) were encoded to ASCII strings using Base64 encoding for transmission and can be decoded easily at the receiver. This choice is favorable as it allows propagation of the messages in the protocol through older infrastructure which only supports ASCII.

3.5.2. Message And Connection Parameters

As stated above, all bytes/binary objects which are not PEM encoded string should be encoded using Base64 encoding to byte-strings and attached to the message. Several things to shed light are the "Client Authentication" and "Challenge For Client" fields, which are Base64 encoded bytes, which indicate to the client that the server needs to authenticate the client as per server policy. Also, the symmetric and symmetric fields "Challenge" fields may seem a little unique to this protocol.

In the case that the flag is raised, the server provides a challenge for the client to sign in the server hello. The client should sign it with its private key and return the signature alongside its certificate signed by the CA (please refer to

Table 2,

Table 3).

Server authentication is non-optional, with the server providing its certificate and signature in the server hello itself, with the latter acting as a proof of access to the server’s private key. However, in order to increase security, another round of challenges is proposed. The client should generate a random byte-string of length 128 bytes and send it to the server to sign in the client handshake finish message. The server should sign the challenge with its private key and also encrypt it symmetrically using the pre-master key. The two products should be checked by the client. If both challenges match expectations, the client essentially verifies the identity of the server. Note that almost a mirror process can take place to authenticate the client if server policy dictates. Details about key derivation follow.

The protocol defines crucial variables and credentials regarding the communication described as follows:

Server Signature The server signature should take into account parameters chosen by both client and server for increased security. Therefore, the signature should consist of the concatenation of the following variables encoded as bytes: client random, global ID, server random, Diffie Hellman parameters, server Diffie Hellman public key, server certificate and the timestamp. Note that the timestamp is converted to bytes in little endian format and should match the timestamp sent in the server hello.

Client Signature Similarly, the client, with its private key should sign the concatenation of: client random, global ID, server random, challenge sent by the server, client certificate and the timestamp. Similar notes to the one above apply here.

Pre-Master Secret The pre-master secret is the direct result of the Diffie Hellman key exchange.

-

Pre-Master Key Even though the pre-master secret is ephemerally generated, to maintain consistency and incorporate the randoms and the timestamp, the actual key should be should be generated in the following way:

Where k is the pre-master secret, are the client random, global ID and the server random respectively.

-

Encryption Key Should be generated in the following way:

Where k is the pre-master key.

-

HMAC Key Should be generated in the following way:

Where k is the pre-master key.

-

Initialization Vectors Draw 8 pseudo-random bytes in the following way:

Where k is the pre-master key.

Note that the choice of 8-byte IVs (and 8-byte counters) is different than most other counter modes. The PTE algorithm is under development and nuances such as modes of operations will be developed with more depth in later research.

Read-Write Counters To facilitate correct encryption and hash based MACs, a connection has 2 counters of size 64 bits (8 bytes) each. The counters are named intuitively, closely related to the purpose they fulfill: server_read_client_write and client_read_server_write. This nomenclature was chosen as when the server sends a message and the client reads it (or vice-versa), the same counter is incremented, making the process somewhat fool-proof for implementation.

3.6. Protocol Implementation

3.6.1. Client/Server Behavior For Transfer Of Short Data

This subsection defines the steps needed to be completed by the client and server after a successful handshake in order to securely send one block of data, limited to 19600 bytes. Immediately after establishing the pre-master secret, both client and server should derive the two separate keys for encryption and integrity checking, as discussed in

Section 3.5.2.

The sender should adhere to the following steps:

Note that if the whole message itself is smaller than the maximum size, the flag indicating last message should always be 1.

3.6.2. Client/Server Behavior For Transfer Of Lengthy Data

All messages in a secure protocol should have a maximum size. This is to prevent attacks known as "data bombs" - attacks which exploit compression to deflate into large files, rendering the server useless. Even though the proposed protocol does not feature compression, an attacker could replace a short but correct message into a large but corrupted message, increasing memory usage at the victim, and in extreme cases can open an opportunity for denial of service attacks, even if the attacker has no cryptographic influence.

It was thus decided to incorporate message limits in the proposed protocol. The maximum length of any payload is bytes. Therefore, if the application layer decides to send a message greater than m bytes, the protocol should split it into blocks of m bytes and increment the counter for each block, with the flag indicating last block being raised only on the last block.

The receiving side should process each block exactly as stated in

Section 3.6.1. However, if the flag indicating last block is 0, it should append every incoming message to a buffer, supplying the application layer with the whole buffer after processing the last block.

3.6.3. Client/Server Behavior For Termination Of Connection

When the client wants to terminate the connection on grounds of completeness, it should send the termination message as stated in

Table 6. On receiving this message, the server should immediately empty its send buffer while updating its summary. After this, the server should sign the final summary (see

Section 3.6.5) using its private key and send it to the client. After this step, the server should close the connection from its side.

The client should verify the signature using the public key. If the signature matches the client-side summary, it can mark the transaction as successful and relay the success to the application layer including the signature provided by the server. Any other outcome which does not consist of a successful signature on this specific message should be relayed as a failure, and the client should discard all the messages it has stored, starting a new transaction if needed.

If implemented correctly, including buffering messages before the final verification, the protocol can guarantee irrefutability even if the server tries to manipulate the information at its side. If, in future, a question about the existence of the conversation arises, the client can produce the messages sent to-and-from it, thus the final summary in contrast to the signature provided by the server (see

Section 3.6.5). Note that the three summarizers for this purpose are non-key based in order to mitigate the need to store cryptographic keys, not endangering the guarantee of backward secrecy. To mitigate determinism of ciphertexts, incorporating the salt functionality as provided by BLAKE2B is strongly recommended.

3.6.4. Operational Auxiliary Requirements

The protocol is implemented using Python’s low-level Socket API over TCP. While TCP guarantees chronological order, it does not preserve message boundaries, risking message coalescence. To solve this, the standard practice of prefixing each JSON-formatted message with its length is adopted. This ensures reliable parsing without compromising the protocol’s security or full-duplex design. This is considered an implementation detail separate from the protocol’s theoretical security.

3.6.5. Cryptographic Hashing and Message Digests

Secure protocols commonly employ cryptographic hash functions not only for data protection but also to verify protocol state integrity. For instance, TLS uses a hash of the handshake transcript to ensure parameter negotiation has not been altered by a Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) adversary [

28].

The proposed protocol utilizes cryptographic hashing in five distinct roles throughout a connection’s lifetime. A hash function is abstracted as a "summarizer" object with two methods: update(), which processes input bytes to update an internal state, and digest(), which finalizes and returns the hash value.

The five applications are as follows:

Server Authentication: The server signs a hash of the connection parameters with its private key. This non-optional step, detailed in

Section 3.4.1, proves the server controls the private key corresponding to its certificate. Verification failure results in connection termination.

Optional Client Challenge: The client may optionally request the server to sign a challenge, combined with the connection parameters (

Section 3.4.1).

Client Authentication (Policy-Dependent): If mandated by server policy, the client must sign the connection parameters, often including a server-provided challenge (

Section 3.4.1).

Data Integrity (HMAC): All data blocks transferred post-handshake are accompanied by a Hash-based Message Authentication Code (HMAC), a keyed cryptographic digest ensuring integrity and authenticity.

Non-Repudiation Digest: To provide irrefutability (

Section 3.4.3 and

Section 3.6.3), three non-keyed hash computations are maintained:

Handshake Transcript (): All messages exchanged during the handshake.

Client-Write Transcript (): All messages sent by the client after the handshake.

Server-Write Transcript (): All messages sent by the server after the handshake.

A final, composite digest for non-repudiation is computed as:

This digest is used during the termination phase, as elaborated in

Section 3.6.3, to cryptographically bind the entire session.

3.7. Error Characterization and Handling

This subsection characterizes errors that may occur during both normal operation and under adversarial conditions. It enumerates the probable causes for these errors and specifies the protocol’s mandated response actions.

As established in previous sections, a secure connection consists of three phases: the handshake, encrypted data transfer, and consensual termination. During development, it was observed that when both communicating parties cooperate, the probability of an error is negligible. However, in the presence of an active adversary attempting to compromise the communication, distinct and detectable errors manifest, particularly within cryptographic credentials. This behavior is a desirable property of a robust security protocol.

Based on these observations, the protocol mandates that upon the detection of any error, the connection must be terminated immediately without attempting to categorize its severity. This design decision is supported by the reliability guarantees of the underlying TCP/IP network layer [

55], which ensures the integrity of data delivery between cooperating endpoints. Consequently, any error that occurs is, with high probability, an indication of adversarial interference, necessitating immediate connection termination to preserve security.

The protocol integrates multiple subsystems and algorithms - including JSON [

54], Base64 encoding [

40], socket communication, and Message Authentication Codes (MACs) - each representing a potential point of failure or ambiguity during message processing, especially under attack. The following error categories are defined:

Parsing Errors: Occur when the incoming message violates the structural syntax of JSON, rendering it invalid.

Credential Mismatch: Occur when cryptographic credentials - such as HMACs, digital signatures, or challenge values - fail to validate against the current connection state.

Malformed Message Errors: Occur when an incoming message is syntactically valid JSON but contains semantic malformations. These include key-value mismatches or internal Base64 decoding errors. The implementation requires messages to contain exactly the set of keys defined in the specification. This strictness enhances security by preventing attackers from introducing extraneous data that could potentially aid in forgery attacks. The presence of undefined keys or values constitutes a malformed message and results in connection termination.

Message Withholding: Occur when an adversary intentionally withholds crucial messages (e.g., termination messages), potentially causing state desynchronization between the client and server.

Network Layer Errors: The protocol operates over TCP/IP, implemented via Python’s socket API. While TCP provides reliability, connectivity issues can manifest as exceptions raised by the socket module, such as ConnectionRefusedError, ConnectionResetError, ConnectionAbortedError, or TimeoutError. As security is paramount, any network-layer error results in the immediate termination of the secure connection.

The protocol requires bi-consensual termination. The initiating party must supply an error code within the termination message. A code of `0’ (sent only by the client to indicate a normal end of transaction) triggers the standard signature process outlined in

Section 3.6.3. Any non-zero error code indicates a critical fault, prompting immediate termination after a simple acknowledgment exchange.

Table 7 delineates the potential termination causes, their corresponding error codes, and the required response from all parties. For production environments, it may be more secure to use a generic non-zero code to avoid leaking diagnostic information to a potential attacker.

3.8. Analysis Of Correctness

All algorithms in this protocol are well defined, tested and refined, apart from Pythagorean Triples Encryption specifically, which is under testing through this protocol. Hence, only academic analysis will be presented, with as much backing as possible.

3.8.1. Data Encoding And Structuring Schemes

The protocol relies on two fundamental encoding standards to structure and transmit data: JSON for serialization and Base64 for binary-to-text encoding. A functional analysis confirms their suitability for this domain.

The primary role of JSON, as defined in RFC 8259 [

39], is to serialize structured objects - composed of fundamental data types - into a text-based format for storage or transmission. This serialized data can later be deserialized, often on a different machine, to reconstruct the original object. Academically, the JSON specification is regarded as exceptionally well-defined, utilizing an unambiguous context-free grammar. This precision allows a parser to definitively determine whether a given string is valid JSON and to identify the location of any errors, a level of diagnostic clarity not always available in alternatives like YAML [

56]. This contribution is two-fold: it provides a clear structure for protocol packets and enforces rules that prevent ambiguity, which is critical for security-prioritized applications.

However, a key implementational caveat of JSON in security contexts is the risk of denial-of-service (DoS) attacks via maliciously crafted input. To mitigate this, the protocol enforces a strict 6000-byte limit on any handshake message, after which the connection is terminated. This limit is calculated from the typical sizes of handshake components-a certificate ( 2000 bytes), a Diffie-Hellman public key ( 600 bytes), exchange parameters ( 1000 bytes), and a signature ( 300 bytes) - summing to approximately 4000 bytes. A 50 percent safety factor is applied to this sum to arrive at the final, conservative limit of 6000 bytes.

Since JSON is limited to fundamental types, a mechanism for encoding binary data is required. Base64 encoding fulfills this role by converting byte-strings into ASCII character strings, which can be safely embedded in JSON fields and decoded after transfer. Although JSON supports UTF-8, Base64 was selected for its ubiquity on the internet and its robustness in ensuring binary data can traverse older, ASCII-restrictive systems without corruption.

It is noted that while complex extensions like JSON Schema exist, the protocol’s use of both JSON and Base64 is basic, minimizing the likelihood of complications or vulnerabilities arising from more advanced features of these specifications.

3.8.2. Output Structure And Cryptographic Hashing

The structure adheres to modern layered cryptographic paradigms, supporting clear separation between encryption, MAC authentication, and digital signature layers. This modularity aligns with structural principles in secure protocol design, and enables independent key management for each layer, reducing key reuse risks and improving resistance to compromise.

In the proposed protocol, the encryption and HMAC keys and pre-master keys were derived from the pre-master secret using a cryptographic one-way function, guaranteeing that breaches in lower layers do not propagate to upper layers and thus compromise the entire connection and more.

3.8.3. Functional Analysis of PKI Components

The proposed system integrates classical PKI components, including certificate authorities (CAs), digital certificates, public/private key pairs, and a revocation mechanism into a lightweight layered encryption model. These elements are not implemented as infrastructure-level services but as logic components in the protocol flow, allowing flexible emulation of PKI functionality without dependency on external trust anchors. The design supports session-based key exchange, ephemeral keys, and signer authentication using modular primitives.

3.9. Analysis Of Security

3.9.1. Secure Design Philosophy

From a systemic standpoint, the protocol achieves layered security through sequential application of symmetric encryption, MAC authentication, and digital signatures. Each layer targets a distinct threat vector: ciphertext confidentiality, message integrity, and sender authenticity, respectively. Key separation, session isolation, and optional IV configuration further enhance security posture. While formal reductions are not included, the architecture draws from secure design patterns used in TLS-like protocols, offering a robust structure with practical safeguards against known cryptographic attacks.

3.9.2. Security Aspects of Encryption Based on Pythagorean Triples

The proposed encryption algorithm offers practical security guarantees rooted in its structural properties. First, functional correctness has been empirically validated by testing over one million random (plaintext, key) pairs, where decryption consistently yielded the original plaintext. This confirms the deterministic invertibility of the Feistel-based design across the full ASCII space. Furthermore, all operations are performed modulo 256 at the byte level, ensuring bounded output and compatibility with standard systems, without overflow or data corruption.

The substitution function , constructed using Pythagorean Triplet logic and enhanced via modular arithmetic and XOR operations, introduces strong non-linearity and high diffusion, which is critical traits that resist linear and differential cryptanalysis. Additionally, the substitution table demonstrates a low collision rate over printable ASCII characters, particularly when used in combination with initialization vectors or session-specific keys. These properties collectively prevent predictable ciphertext patterns and enhance entropy.

Finally, the algorithm’s layered architecture supports modular integration of encryption, authentication (MAC), and digital signature functionalities. This separation of concerns allows for independent key management, reduces key reuse risks, and improves resilience against compromise by isolating cryptographic responsibilities across layers. Although formal proofs like IND-CPA security are not provided here, the design reflects established principles in secure symmetric cipher construction and offers robustness suitable for practical deployments.

3.9.3. Statistical Crypt-Analysis of Pythagorean Triples Encryption

The block cipher proposed in

Section 3.2 was tested against basic statistic and cryptanalysis tests. A full cryptanalysis will be performed in later research.

A series of basic tests were conducted for initial analysis of the algorithm, mostly based on the cipher test suite by NIST [

57]:

Mono-bit Frequency Test: To check if there exists a bias between the number of ones and zeros in ciphertexts.

Runs Test: To test for (joint) correlation between consecutive bits of ciphertexts.

Autocorrelation Test: To check for correlation between bits of the same ciphertext (up to 20 lags).

Avalanche Distribution Test: To check if there exist bits in the ciphertext which do not have a 50% probability of changing for a change of one bit in the plaintext or key. Also to model the number of bits changed in ciphertext as a result of one bit changed in any input.

Linear Approximation of Table (LAT): As the round function’s non linear component can be seen as a substitution, a linear approximation of the substitution table was performed, to check for linear bias between bytes.

Note that traditional LAT assumes 8-bit input S-boxes (256 entries). Our cipher can be modeled to use a 9-bit input space generated by summing 8-bit data and 8-bit key bytes, requiring analysis of 512 input values instead of 256. The adaptations included extending input masks to cover a 9-bit space and extending the test space to mask combinations, with other factors remaining unchanged.

3.9.4. Analysis Of Other Cryptographic Primitives in the Protocol

Beyond the core PTE encryption scheme, the protocol incorporates SHA-256 hashing for message integrity, HMAC for authenticated encryption when needed, and optional digital signatures using RSA or ECDSA depending on the deployment context. Initialization vectors (IVs) are either random or derived via KDFs when session state is available. These primitives were chosen for their standardization, platform compatibility, and synergy with the lightweight arithmetic of the PTE core. The modularity allows the protocol to degrade gracefully under partial trust or minimal key distribution scenarios.

The protocol employs two fundamental cryptographic primitives: the Diffie-Hellman key exchange for establishing a shared secret and the RSA-PSS algorithm for digital signatures.

The Diffie-Hellman key exchange [

21] enables two parties to collaboratively generate a shared secret over an insecure channel without any prior shared knowledge. Its functionality is based on the computational difficulty of the Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP). Each party generates a public/private key pair from agreed-upon public parameters (a generator g and a prime modulus p). They then exchange their public keys. Each party combines their own private key with the other’s public key to compute the same shared secret. A passive adversary observing the public keys cannot feasibly compute this secret. This shared secret forms the basis for deriving symmetric session keys for encryption and authentication, providing forward secrecy if ephemeral key pairs are used.

The RSA-PSS (RSA Signature Scheme with Probabilistic Signature) [

53] is used for digital signatures to provide authentication and non-repudiation. Functionally, it improves upon older, deterministic RSA signing by incorporating a probabilistic padding scheme. Before signing, the message is hashed and then padded with a random salt value. This process ensures that two signatures of the identical message are different, which protects against certain cryptanalytic attacks. The recipient verifies the signature by reconstructing the padding pattern. RSA-PSS is provably secure under the RSA assumption and is considered the modern standard for RSA-based signatures.

The RSA Assumption states that for all efficient (probabilistic polynomial-time) algorithms, the probability of solving the RSA Problem is negligible. In simpler terms, it is assumed that there is no practical algorithm that can efficiently compute roots modulo n when n is a product of two large, secret primes.

This assumption is foundational because the most straightforward way to solve the RSA problem -finding

m as the

root of

c modulo

n - is believed to be computationally equivalent to factoring the modulus. Since the Integer Factorization Problem is also considered computationally intractable for sufficiently large primes, the security of RSA is thereby based on this well-studied hard problem [

12].

Therefore, when we state that "RSA-PSS is provably secure under the RSA assumption" [

53], it means that forging a signature can be shown to be as difficult as solving the RSA Problem. An adversary capable of creating a valid forgery could also be used to construct an algorithm to break the underlying RSA assumption.

3.9.5. Correctness Of The Feistel Structure

We formally demonstrate that our Feistel-based cipher correctly decrypts to the original plaintext for all keys in the key space. The core insight, established by Feistel [

44], is that the structure is inherently reversible regardless of the round function

F. For each round

i with left and right halves

and round key

, the encryption performs:

Decryption reverses this process using the same round keys in reverse order:

Since all operations - including our modular arithmetic within the domain-are well-defined and deterministic, the composition of encryption followed by decryption yields the identity function, restoring the original plaintext.

This theoretical guarantee is maintained in practice through careful implementation that preserves the Feistel invariants. Luby and Rackoff [

45] further established that even with pseudorandom round functions, the Feistel construction provides cryptographic security, validating our architectural choice. Our empirical validation in sub

Section 4.1 confirms this theoretical correctness across extensive test vectors.

3.9.6. Known Attack-Wise Analysis Of Security

Impersonation/Spoofing: Mitigated by certificate verification, challenge-response handshake stages, and integrity-protected summary fields.

Harvest and Decrypt: Mitigated by incorporating three random values and a timestamp.

MITM Attacks: Mitigated by certificate validation, secure key establishment, encryption, and integrity checking.

Secure Connection Stripping: Mitigated by non-negotiable, mandatory authentication, encryption, and integrity.

Connection Downgrade: Mitigated by using a single, fixed protocol version.

Parameter Downgrade: Mitigated by standardizing cryptographic strengths at configuration time.

Certificate Spoofing: Mitigated by terminating the connection if certificate details do not match strict standards, assuming a secure CA.

Lower-Level MITM (ARP/DNS): Mitigated by the attacker’s inability to complete the real-time cryptographic challenge.

Certificate-Related Attacks: Mitigated by the assumed security of the Certificate Authority (CA).

Replay Attacks: Mitigated in the handshake by timestamps and summary fields, and in data transfer by counters and HMACs.

Key Exchange/Negotiation Attacks: Mitigated by unified minimum parameter strengths (configuration dependent) and prioritizing security over flexibility by preventing re-negotiation.

Isolation Attacks: Mitigated by securely deriving all session keys (encryption, HMAC) from the pre-master secret.

3.9.7. Risk Analysis Table

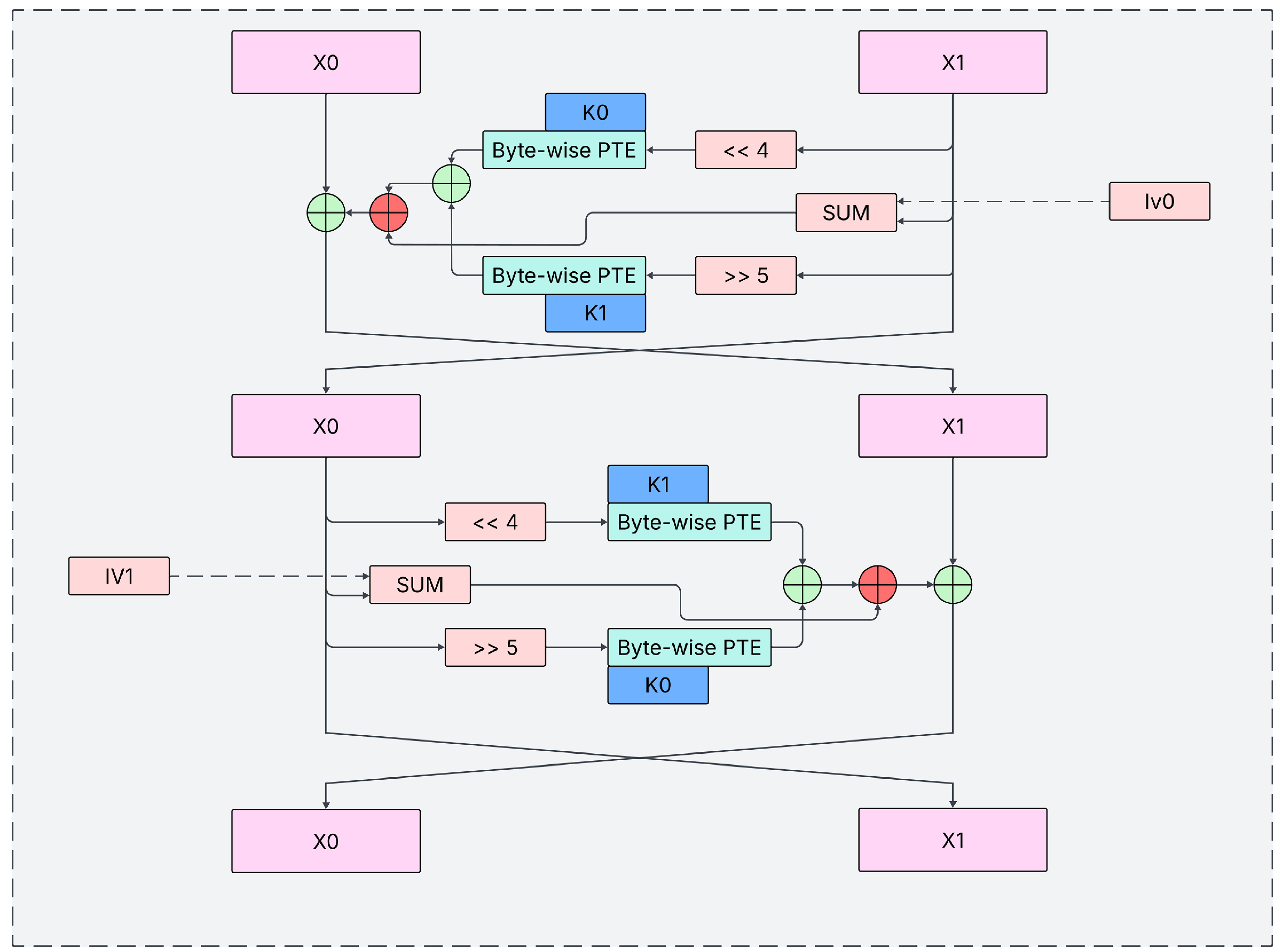

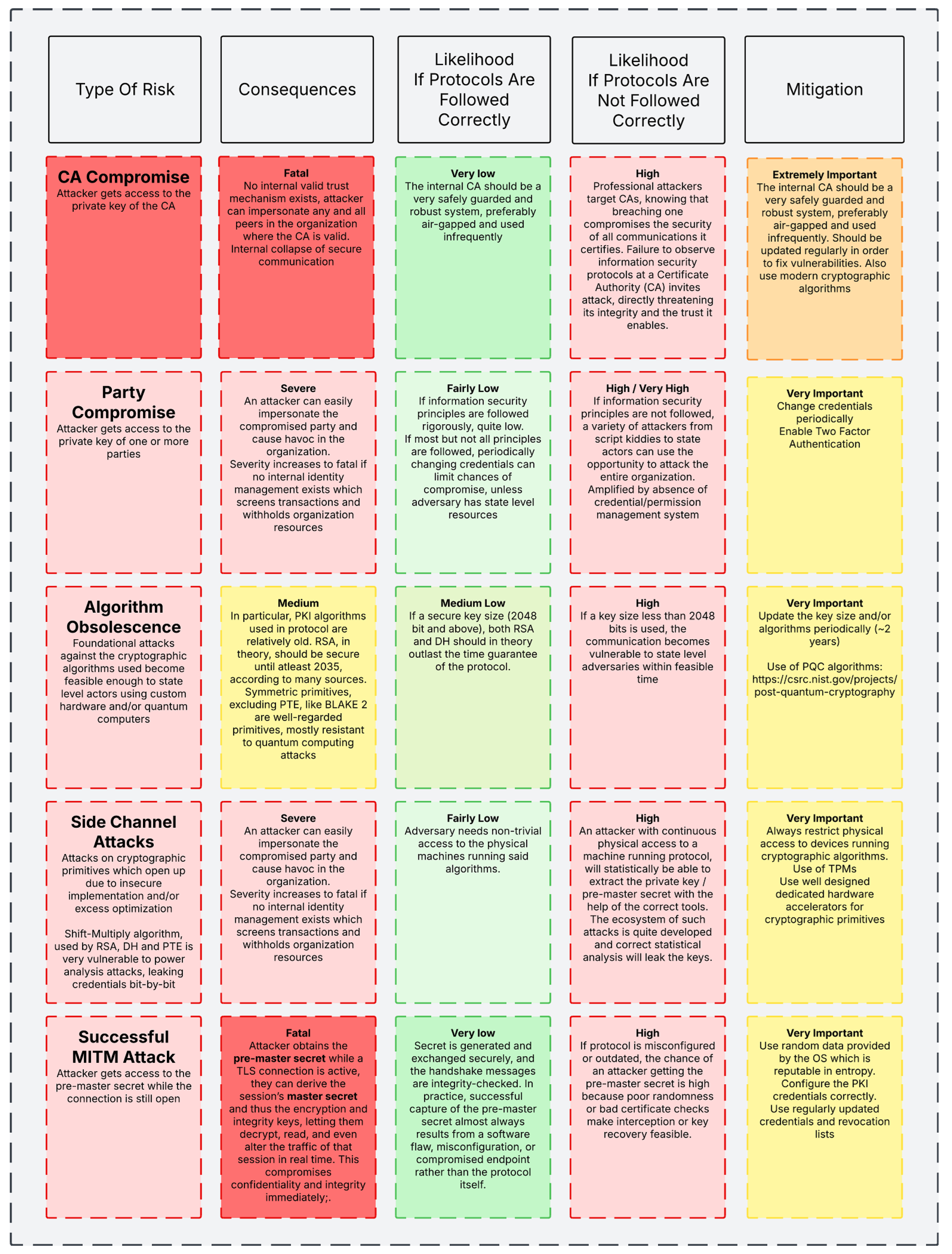

Figure 3 displays the imminent risks associated with using our protocol and the categorization of them as per the likelihood of occurrence.

4. Results

4.1. Pythagorean Triples Encryption

Pythagorean Triples Encryption, as defined in

Section 3.2 is an instantiation of a Feistel Cipher which are known to be developer and user friendly as well as reliable (a short review of the advantages and the correctness are given in

Section 3.9.5). This subsection displays the various tests conducted on the proposed cipher and the respective results of test.

Note that statistical tests were conducted in C++ for a baseline standard whereas development was done using Python 3.10+, both on a single thread I7-1165G7 processor running at 2.80 GHz.

4.1.1. Random Key-Plaintext Testing And Performance

A basic test was conducted on one million random 128-bit (key,data,iv) tuples to test the correctness of 32 rounds of encryption as well as decryption, i.e. to check if the data after decryption matched the plaintext or not under the same key. This test terminated gracefully, with no data mismatch in a runtime of 11.153 seconds, with a resulting throughput of around 2.86 MB per second. As the cipher is essentially a drop-in replacement to TEA with essentially the same structure and number of rounds, we believe the proposed cipher should be almost as fast as TEA [

46].

Both the correctness and performance results met expectations, as the Feistel cipher is a very well-tested, foolproof and reliable architecture with incredible support for fast ARX round functions.

4.1.2. Statistical Analysis

The following table displays a statistical analysis on the ciphertext after systematically changing bits in the plaintext and the ciphertext, with every aspect being checked on 10000 pairs.

Table 8.

Statistical Analysis

Table 8.

Statistical Analysis

| Criterion |

Value |

Units |

Remark |

| Monobit Frequency Std. |

0.0396 |

% |

49.9604 % ones vs 50.0396 % zeros |

| Monobit Frequency P |

0.65406 |

- |

Nist Special Suite |

| Runs: Expected Vs Actual |

640,001 / 640,391 |

Runs |

|

| Runs: Std. |

0.061 |

% |

Deviation |

| Runs: Z / P scores |

0.69 / 1.510 |

|

Nist Special Suite |

| Avalanche Key/PT Bits Changed Mean |

63.78 / 49.83 |

bits / percentage |

128-bit block size |

| Avalanche Key/PT Bits Changed Deviation |

0.2245 / 0.35 |

bits / percentage |

128-bit block size |

Mono-bit Frequency Test: The proposed cipher excels in this test as the ratio of ones to zeros is very close to 1.

Runs Test: The proposed cipher excels in this test as well, with the actual number of runs (consecutive bits) being very close to the expected value.

Autocorrelation Test: The proposed cipher does not show any long or short term dependencies between different bits of the same ciphertext.

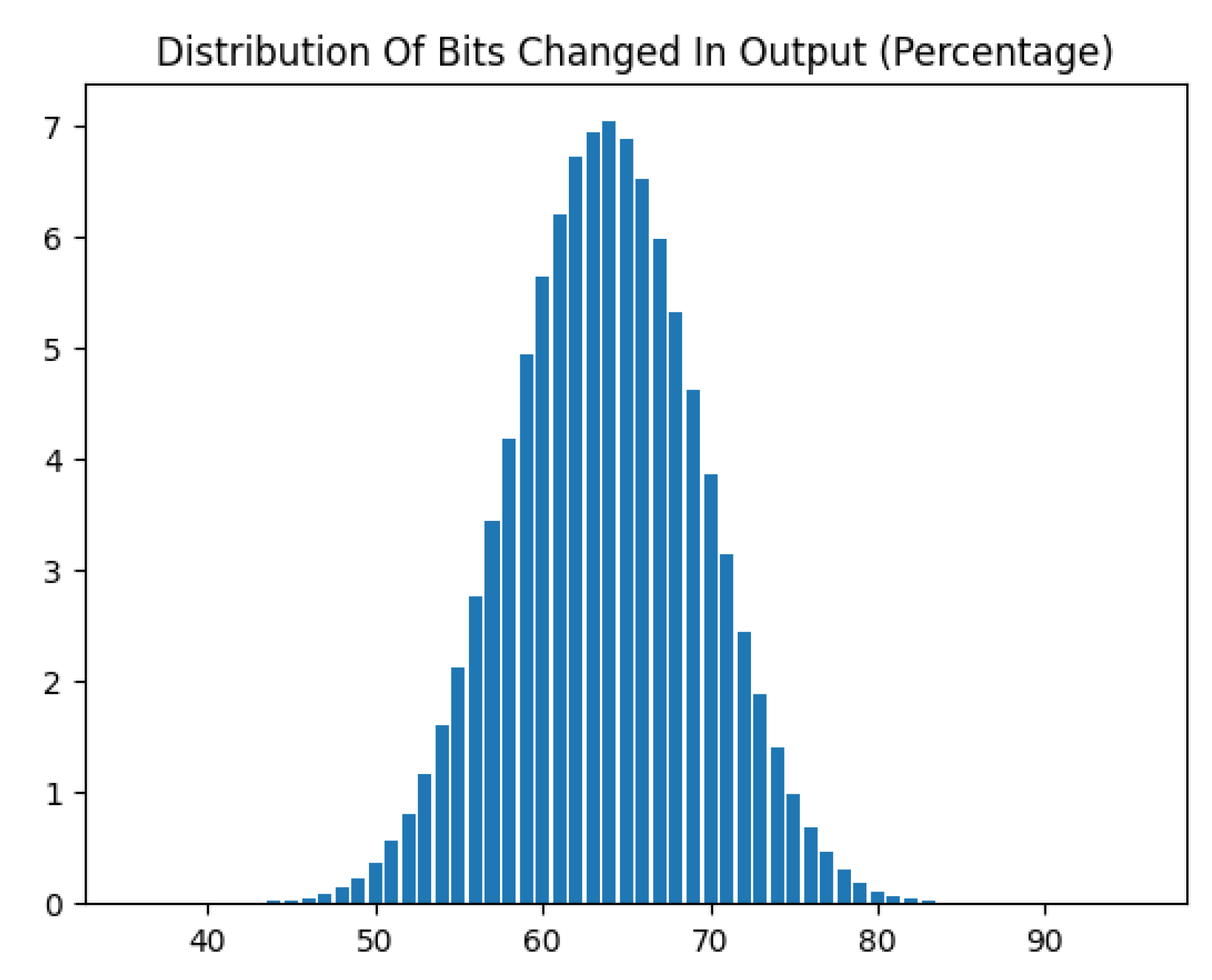

Avalanche Distribution Test: The distribution of number of bits changed in the ciphertext as a result of one bit flip in the plaintext follows a normal distribution with a mean very close to the half block size as required by the strict avalanche criterion. The actual distribution is documented in

Figure 4.

The above analysis confirms that the proposed cipher produces outputs which are statistically in-differentiable from true random sequences under testing. The proposed cipher passed with flying colors in the autocorrelation test with near-ideal 50% disagreement rates on all tested lags.

Linear Approximation Table analysis revealed significant biases in the mathematically-derived S-box, with maximum bias 0.375 observed between specific input and output bit combinations. This indicates linear approximations that hold with 68.75% probability rather than the ideal 50%, representing a cryptanalytic weakness in the S-box component.

However, comprehensive statistical testing demonstrated that the full Feistel cipher with 32 rounds maintains strong security properties despite component weaknesses. The excellent avalanche effect (49.82% average bit changes) and passing mono-bit, runs, and autocorrelation tests show the Feistel structure successfully mitigates the S-box’s linear vulnerabilities through robust diffusion and mixing across rounds.

4.2. Proof Of Security Based On Dolev-Yao Model

This subsection presents a semi-formal analysis of the proposed protocol’s security properties within the widely adopted Dolev-Yao adversary model. The objective of this analysis is to demonstrate that the protocol upholds the security guarantees outlined in sub

Section 3.3.

Assumption A1.

The adversary can control the communication between two parties including overhearing, manipulating and forging messages.

Assumption A2.

The adversary cannot break cryptographic primitives. Also, adversary cannot guess secrets ahead of time due to including but not limited to, implementation and isolation attacks.

Theorem 1.

The protocol guarantees confidentiality and backwards secrecy if Diffie Hellman keys are generated securely.

Proof. As per assumption A2, the adversary cannot directly guess the secret. The protocol dictates a minimum key size of 2048 bits for Diffie Hellman keys. Assuming that the parameters were generated correctly, an adversary cannot feasibly attack the exchange.

The pre-master key incorporates the three randoms in a cryptographic manner, thus being infeasible to attack, especially if at least one of the parties generates its secrets randomly. As the encryption and HMAC keys are keyed hashes using a secure hash function, if an attacker theoretically gets access to one of the keys, the other key is not within reach of the attacker as this forces the attacker to invert a secure cryptographic hash function which is not feasible. □

Theorem 2.

The protocol guarantees authentication under the assumption that the CA is secure and correct handling/manipulation of private keys.

Proof. As briefly described in

Section 2.6, party A signing any document with its private key and the signature being verified by party B proves to B that A has access to the private key which signed the document, assuming B has the correct public key of A. By incorporating timestamps and randomness into the document, the signature becomes a cryptographically robust way to prove ownership.

Sub

Section 3.4.1 elaborates on the transfer of credentials and challenges. By completing the challenge, the verifying party can be convinced that the latter party has current access to the private key. The public key, as is the basis of PKI, is signed by the CA, thus by verifying the correctness of the challenge and signature, the verifying party can be sure that it is talking to party it wants to. After completion of handshake, if successful, the conversation is guaranteed to be direct and not through a middleman. This behavior is extracted from the TLS protocol [

8]. □

Theorem 3.

Assuming correct completion of handshake and credential manipulation, the protocol guarantees that changes in content of messages during transfer are detected by the receiver as also changes in the number of the internal packets.

Proof. As established in sub

Section 3.4.2, data exchanged between communicating parties is secured using a keyed HMAC. Theorem 1 ensures that the pre-master secret remains exclusively with the legitimate parties upon a successful handshake, thereby preventing an attacker from obtaining the HMAC key, hence, forging valid MACs.

Consequently, any modification to a message’s content will result in an HMAC mismatch at the receiver, enabling tamper detection. However, supporting multi-block messages - as outlined in sub

Section 3.6.2 - introduces potential vulnerabilities if not carefully designed. For instance, without per-block authentication, an attacker could replay or omit blocks, misleading the receiver into accepting manipulated data. □

Theorem 4.

Assuming randomly generated connection parameters and correct handshake practices, an attacker impersonating a legitimate party will not be able to complete the handshake successfully.

Proof. Impersonation is mitigated through a robust handshake protocol that employs mutual challenges to authenticate both parties, as detailed in sub

Section 3.4.1.

Following the approach of TLS versions 1.2 and 1.3 [

8,

28], server impersonation is primarily prevented during the Server Hello phase. An attacker lacking the server’s private key cannot forge a valid signature verifiable by the CA-signed certificate’s public key.

To address the extreme scenario where weak randomness compromises secret generation - potentially enabling handshake replay - the protocol incorporates a timestamp into the server’s signature, see sub

Section 3.5.2. This ensures that any replayed signature can be detected and rejected if its timestamp exceeds a predefined tolerance threshold. □

Theorem 5.

Assuming un-compromised and secure generation of connection parameters, the protocol guarantees security against replay attacks.

Proof. Replay attacks are mitigated by incorporating timestamps and counters into all cryptographic hashes and MACs. A replayed message with an unmodified timestamp will be rejected as stale by the receiver. Conversely, if an attacker attempts to modify the timestamp, the HMAC validation will fail, since the attacker lacks the key required to generate a valid MAC for the altered data. In both scenarios, the protocol effectively prevents replay attacks. □

5. Discussion

5.1. Pythagorean Triples Based Encryption

Apart from the ease of decryption, two characteristics became clear after a shallow but cryptographic analysis of the algorithm: the mapping used byte-wise to mix the data is indeed non-linear however is not bijective, with values occurring more than once.

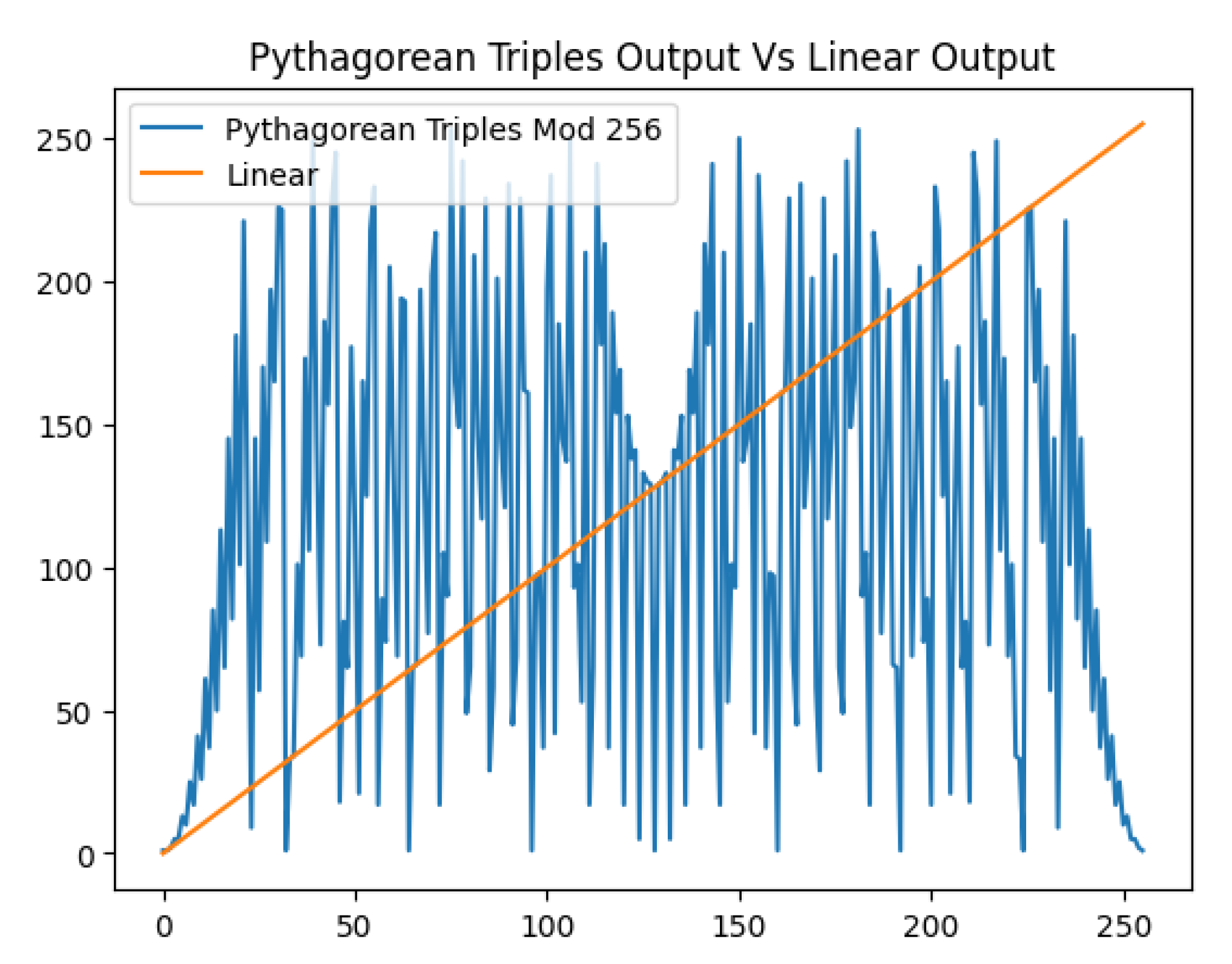

Figure 5 displays the non-linearity of the algorithm.

As the function is equivalent to a substitution, it is extremely important for it to be bijective, which in this case is not. However, we believe correct incorporation of this function may help mitigate vulnerabilities - for example key whitening and incorporation in a Feistel Cipher should in theory help reduce collisions to a far-fetched possibility. A deeper analysis will be provided in later research as the focus of this paper is more on the implementation than security.

5.2. Use Cases

This encryption approach is well-suited for secure messaging platforms, embedded systems with constrained computational power, and educational cryptographic tools due to its lightweight arithmetic and intuitive mathematical basis. Furthermore, its deterministic core and optional IV configuration make it adaptable to both streaming and block-based use cases. Future work could explore deployment within IoT devices or over low-latency communication networks, using hybrid modes with AES or ChaCha20 for layered defense.

The protocol described in this work is designed to address inter-organizational security requirements. Various organizations across multiple sectors maintain internal computing infrastructure that necessitates secure communication channels, for which traditional Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) may represent an unsuitable or overly complex solution.