Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Scope and Approach

3. Review

3.1. Fundamentals of Soil Compaction and Recompactation

3.2. Mobilization and Alteration of Soil Structure

3.3. Progressive Compaction Management

3.4. Virgin Compression Line (VCL)

3.5. Impact of Mechanized Traffic in Sugarcane Fields

3.6. Controlled Traffic Farming (CTF)

3.7. Soil Preparation in Sugarcane Cultivation

3.7.1. Conventional Tillage System (CST)

3.7.2. Reduced Tillage System (RST)

3.7.3. Strip Soil Tillage (SST)

- SSTC – Strip Soil Tillage associated with a bed former: combines subsoiler shanks, rotary hoe, and simultaneous application of amendments and inputs in the planting row;

- SSTS – Strip Soil Tillage with Localized Subsoiling: replaces the rotary hoe with modified subsoilers, without rotary surface mobilization;

- SSTP – Variant of SSTC with deep incorporation of 25% of the lime (0.4–0.6 m), aimed at chemical correction in subsurface layers.

3.7.4. Physical and Structural Benefits

3.7.5. Operational Efficiency and Sustainability

3.7.6. Hydrological and Root Performance

3.7.7. Integration with Chemical and Biological Management

3.7.8. Integrated Management Associated with the Strip Soil Tillage System (SSTC)

3.8. Advanced Soil Management Support Technologies Automatic

3.8.1. Positioning and Steering Systems

3.8.2. Soil Sensors and In-Situ Monitoring

3.8.3. Aerial Photogrammetry and Drones

3.8.4. Digital Platforms and Precision Agriculture

4. Discussion

4.1. Integration of CTF, SST, and Compaction Control

4.2. Improvement of Physical Structure and Root System

4.3. Chemical Correction and Fertility

4.4. Organic Matter and Microbiota

4.5. Bioactivation by Phosphorus Solubilizers

4.6. Operational Efficiency and Environmental Impact

4.7. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions and Practical Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

- • Soil compaction caused by harvesting and transportation operations reduces porosity, root growth, infiltration, and water and nutrient availability, with measurable effects on productivity when soil density and stresses exceed critical limits;

- • The adoption of CTF reduces the area effectively subject to random traffic and defines contour zones that make SSTC feasible without mobilizing the entire production network; the combination of CTF and SSTC preserves structural interrows and concentrates mobilization only on the necessary strips;

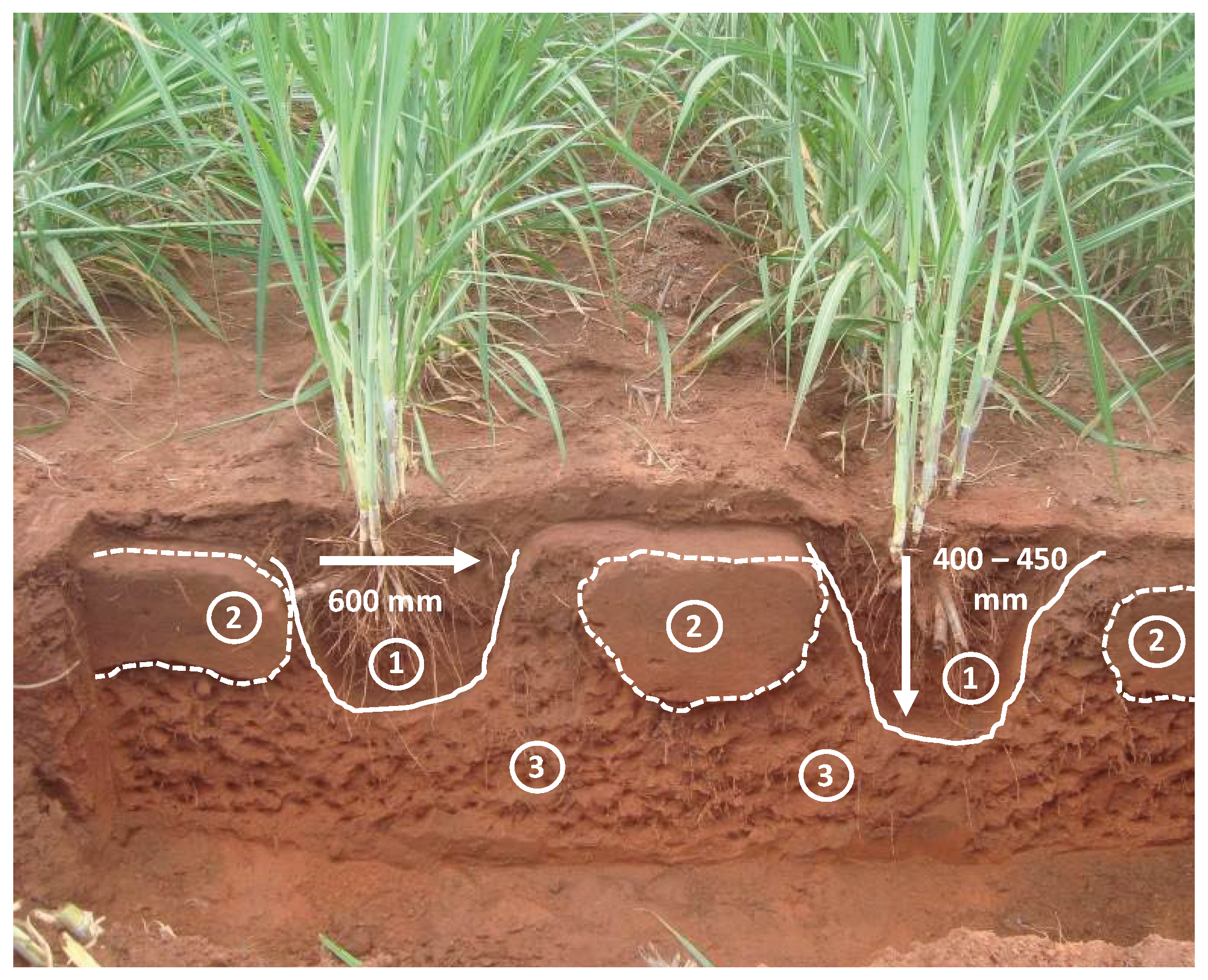

- • To preserve root zones and avoid encroachment on traffic zones, the bibliographic constraints adopted here result in the following SSTC contour geometries: mobilized strip width = 0.60 m (derived from a 1.50 m planting spacing minus lateral propagation of stresses due to overflow = 0.90 m) and working depth of 0.40 m (functional root concentration at 0–0.40 m). These dimensions should be the baseline parameter for experimental evaluations and design models;

- • The coordinated implementation of CTF + SSTC presents quantifiable benefits in operational and environmental efficiencies: average mobilization of the production network close to 53%, observed average reductions in diesel consumption of 43.5% in compared scenarios, and estimated CO2 emission reductions of 163–315.4 kg ha-1;

- • Agronomic gains (porosity recovery, greater root exploration depth, and yield gains) tend to be observed when SSTC is applied in a targeted and repeated manner combined with conservation practices (cover crops, organic incorporation), but the magnitude of the benefit depends on soil texture, moisture content at the time of operation, and traffic history;

- • Localized subsoiling demonstrates a positive effect, but is often transient; the rate of recompactation is high in soils under continuous traffic and varies with texture, moisture content, and intensity of operations. Therefore, the effectiveness of SSTC is only maintained when accompanied by reduced traffic outside defined zones (CTF) and periodic monitoring;

- • There is a clear need for standardized experimental validation: field trials with designs that compare SSTC+CTF versus CST and CTF alone, measuring βb, SR, macroporosity, hydraulic parameters, production, and economic indicators in time series (pre- and post-intervention, multiple harvests);

- • Critical gaps identified: (i) lack of longitudinal studies (>5 years) on recompacting and the sustainability of its effects; (ii) quantified integration between localized input management (fertilization, amendments, filter cake/composts) and the agronomic response of SSTC;

- • From a policy and circular economy perspective, the adoption of SSTC integrated with CTF has the potential to reduce emissions and enable synergies with chemical/biological management (localized application of amendments and organic waste), creating opportunities for incentive mechanisms (carbon credits) and optimizing input use.

5.2. Practical Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTC | Controlled Traffic Farming |

| SST | Strip Soil Tillage |

| SSTC | Strip Soil Tillage with Bed Former |

| SSTS | Strip Soil Tillage with Localized Subsoiling |

| SSTP | Strip Soil Tillage with Deep Lime Incorporation |

| CST | Conventional Tillage System |

| RST | Reduced Tillage System |

| σP | Pre-consolidation Pressure |

| σZ | Vertical Stress |

| ρb | Bulky Density |

| SR | Soil Resistance to Penetration |

| VCL | Virgin Compression Line |

| DAP | Days After Planting |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

References

- Schäffer, J. (2022). Recovery of soil structure and fine root distribution in compacted forest soils. Soil Systems, 6(2), 49. [CrossRef]

- Eggers, H. S., de Brito, D. L., Sprey, M. M., Pereira, L. E. S., Garcia, B. T., & de Souza Maia, J. C. (2025). Impactos do manejo agrícola na resistência a penetração do solo: comparação entre cultivos de cana-de-açúcar e floresta nativa. REVISTA DELOS, 18(63), e3467-e3467.

- Saljnikov, E., Eulenstein, F., Lavrishchev, A., Mirschel, W., Blum, W. E., McKenzie, B. M., ... & Mueller, L. (2022). Understanding soils: their functions, use and degradation. In Advances in understanding soil degradation (pp. 1-42). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Horn, R. F. (2021). Soils in agricultural engineering: Effect of land?use management systems on mechanical soil processes. Hydrogeology, chemical weathering, and soil formation, 187-199. [CrossRef]

- Shaheb, M. R., Venkatesh, R., & Shearer, S. A. (2021). A review on the effect of soil compaction and its management for sustainable crop production. Journal of Biosystems Engineering, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Keller, T., Lamandé, M., Naderi-Boldaji, M., & de Lima, R. P. (2022). Soil compaction due to agricultural field traffic: An overview of current knowledge and techniques for compaction quantification and mapping. Advances in understanding soil degradation, 287-312. [CrossRef]

- Ogorek, L. L. P., Gao, Y., Farrar, E., & Pandey, B. K. (2024). Soil compaction sensing mechanisms and root responses. Trends in Plant Science. [CrossRef]

- Misiewicz, P. A., Kaczorowska-Dolowy, M., White, D. R., Dickin, E. T., & Godwin, R. J. (2022). Agricultural traffic management systems and soil health. [CrossRef]

- Shaheb, M. R., Misiewicz, P. A., Godwin, R. J., Dickin, E., White, D. R., & Grift, T. E. (2024). The effect of tire inflation pressure and tillage systems on soil properties, growth and yield of maize and soybean in a silty clay loam soil. Soil Use and Management, 40(2), e13063. [CrossRef]

- Júnnyor, W. D. S. G., Diserens, E., De Maria, I. C., Araujo-Junior, C. F., Farhate, C. V. V., & de Souza, Z. M. (2019). Prediction of soil stresses and compaction due to agricultural machines in sugarcane cultivation systems with and without crop rotation. Science of the total environment, 681, 424-434. [CrossRef]

- Júnnyor, W. D. S. G., De Maria, I. C., Araujo-Junior, C. F., Diserens, E., da Costa Severiano, E., Farhate, C. V. V., & de Souza, Z. M. (2022). Conservation systems change soil resistance to compaction caused by mechanised harvesting. Industrial Crops and Products, 177, 114532. [CrossRef]

- Cherubin, M. R., da Luz, F. B., de Lima, R. P., Tenelli, S., Bordonal, R. O., de Oliveira, B. G., ... & Carvalho, J. L. N. (2024). Soil Health in Sugarcane Production Systems. Soil Health Series: Volume 3 Soil Health and Sustainable Agriculture in Brazil, 145-178. [CrossRef]

- da Luz, F. B., Gonzaga, L. C., Castioni, G. A. F., de Lima, R. P., Carvalho, J. L. N., & Cherubin, M. R. (2023). Controlled traffic farming maintains soil physical functionality in sugarcane fields. Geoderma, 432, 116427. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L. C., de Souza, Z. M., Franco, H. C. J., Otto, R., Neto, J. R., Garside, A. L., & Carvalho, J. L. N. (2018). Soil texture affects root penetration in Oxisols under sugarcane in Brazil. Geoderma regional, 13, 15-25. [CrossRef]

- Delmond, J. G., Junnyor, W. D. S. G., de Brito, M. F., Rossoni, D. F., Araujo-Junior, C. F., da Costa Severiano, E., & Severiano, E. C. (2024). Which operation in mechanized sugarcane harvesting is most responsible for soil compaction?. Geoderma, 448,116979. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, K. J., Rolim, M. M., de Lima, R. P., Cavalcanti, R. Q., Silva, Ê. F., & Pedrosa, E. M. (2021). Soil physical indicators of a sugarcane field subjected to successive mechanised harvests. Sugar Tech, 23, 811-818. [CrossRef]

- Otto, R., Trivelin, P. C. O., Franco, H. C. J., Faroni, C. E., & Vitti, A. C. (2009). Root system distribution of sugar cane as related to nitrogen fertilization, evaluated by two methods: monolith and probes. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 33, 601-611. [CrossRef]

- Mazaron, B. H. S., Coelho, A. P., & Fernandes, C. (2022). Is localized soil tillage in the planting row a sustainable alternative for sugarcane cultivation?. Bragantia, 81, e4222. [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.F.D., Albiero, D., Rossetto, R., Biagi, J.D., & da Silva, J. G. (2023). Strip soil tillage and traffic over the soil on sugar cane compared to conventional tillage systems. Sugar Tech, 25(5), 1025-1035. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, C. C., De Maria, I. C., da Silva Guimarães Júnnyor, W., Figueiredo, G. C., Dechen, S. C. F., & Bolonhezi, D. (2022). ROOT parameters of sugarcane and soil compaction indicators under deep strip tillage and conventional tillage. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 18537. [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.F.D. (2021). Análise econômica e operacional de preparo de solo e colheita mecanizada= Economic and operational analysis of soil tillage and mechanized harvesting (Doctoral dissertation, [sn]).

- Alesso, C. A., Cipriotti, P. A., Masola, M. J., Carrizo, M. E., Imhoff, S. D. C., Rocha-Meneses, L., & Antille, D. L. (2020). Spatial distribution of soil mechanical strength in a controlled traffic farming system as determined by cone index and geostatistical techniques. [CrossRef]

- Antille, D. L., Peets, S., Galambošová, J., Botta, G. F., Rataj, V., Macak, M., ... & Godwin, R. J. (2019). Soil compaction and controlled traffic farming in arable and grass cropping systems. [CrossRef]

- Bluett, C., Tullberg, J. N., McPhee, J. E., & Antille, D. L. (2019). Soil and Tillage Research: Why still focus on soil compaction? Soil and Tillage Research, 194, 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Botta, G. F., Antille, D. L., Nardon, G. F., Rivero, D., Bienvenido, F., Contessotto, E. E., ... & Ressia, J. M. (2022). Zero and controlled traffic improved soil physical conditions and soybean yield under no-tillage. Soil and Tillage Research, 215, 105235. [CrossRef]

- Etana, A., Holm, L., Rydberg, T., & Keller, T. (2020). Soil and crop responses to controlled traffic farming in reduced tillage and no-till: some experiences from field experiments and on-farm studies in Sweden. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B - Soil & Plant Science, 70(4), 333-340. [CrossRef]

- Hefner, M., Labouriau, R., Nørremark, M., & Kristensen, H. L. (2019). Controlled traffic farming increased crop yield, root growth, and nitrogen supply at two organic vegetable farms. Soil and Tillage research, 191, 117-130. [CrossRef]

- Martins Filho, M.V., Siqueira, D. S. and Marques Júnior, J. (2015). The importance of knowing the variability of soil attributes - A importância de se conhecer a variabilidade dos atributos do solo. In: Processos agrícolas e mecanização da cana-de-açúcar. Cham: Sociedade Brasileira de engenharia Agrícola. pp. 149 - 173.

- Ró?ewicz, M. (2022). Review of current knowledge on strip-till cultivation and possibilities of its popularization in Poland. Polish Journal of Agronomy, 49, 20-30. [CrossRef]

- Voltr, V., Wollnerová, J., Fuksa, P., & Hruška, M. (2021). Influence of tillage on the production inputs, outputs, soil compaction and GHG emissions. Agriculture, 11(5), 456. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Sha, Y., Ren, Z., Huang, Y., Gao, Q., Wang, S., ... & Feng, G. (2024). Conservative strip tillage system in maize maintains high yield and mitigates GHG emissions but promotes N2O emissions. Science of The Total Environment, 173067. [CrossRef]

- Toledo, M. P., Rolim, M. M., de Lima, R. P., Cavalcanti, R. Q., Ortiz, P. F., & Cherubin, M. R. (2021). Strength, swelling and compressibility of unsaturated sugarcane soils. Soil and Tillage Research, 212, 105072. [CrossRef]

- Esteban, D. A. A., de Souza, Z. M., Tormena, C. A., dos Santos Gomes, M. G., Parra, J. A. S., Júnnyor, W. D. S. G., & de Moraes, M. T. (2024). Risk assessment of soil compaction due to machinery traffic used in infield transportation of sugarcane during mechanized harvesting. Soil and Tillage Research, 244, 106206. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, B. K., & Bennett, M. J. (2024). Uncovering root compaction response mechanisms: new insights and opportunities. Journal of Experimental Botany, 75(2), 578-583. [CrossRef]

- Torres, L. C., Nemes, A., ten Damme, L., & Keller, T. (2024). Current limitations and future research needs for predicting soil precompression stress: A synthesis of available data. Soil and Tillage Research, 244, 106225. [CrossRef]

- Arruda, A. B., Souza, R. F. D., Brito, G. H. M., Moura, J. B. D., Oliveira, M. H. R. D., Santos, J. M. D., & Dutra e Silva, S. (2021). Resistance of soil to penetration as a parameter indicator of subsolation in crop areas of sugar cane. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 11780. [CrossRef]

- Crusciol, C. A. C., McCray, J. M., de Campos, M., do Nascimento, C. A. C., Rossato, O. B., Adorna, J. C., & Mellis, E. V. (2021). Filter cake as a long-standing source of micronutrients for sugarcane. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 21(1), 813-823. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M. A., Antille, D. L., Kodur, S., Chen, G., & Tullberg, J. N. (2021). Controlled traffic farming effects on productivity of grain sorghum, rainfall and fertiliser nitrogen use efficiency. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 3, 100111. [CrossRef]

- Bayat, H., Zangeneh, Z., Heydari, L., & Hamzei, J. (2022). The effects of tillage, cover crop and cropping systems on confined compression behavior of a sandy loam soil. Dry Land Soil Research (DLSR), 1(1), 85-96. [CrossRef]

- D’Antonio, P., Mehmeti, A., Toscano, F., & Fiorentino, C. (2023). Operating performance of manual, semi-automatic, and automatic tractor guidance systems for precision farming. Research in Agricultural Engineering, 69(4), 179. [CrossRef]

- Ivanchenko, P. G., Astafiev, V. L., Polichshuk, Y. V., Binyukov, Y. V., Derepaskin, A. I., Kuvaev, A. N., ... & Murzabekov, T. A. (2023). Effectiveness of the use of automatic driving systems in technological processes of crop cultivation in the northern region of Kazakhstan. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 71(5). [CrossRef]

- da Luz, F. B., Carvalho, M. L., Castioni, G. A. F., de Oliveira Bordonal, R., Cooper, M., Carvalho, J. L. N., & Cherubin, M. R. (2022). Soil structure changes induced by tillage and reduction of machinery traffic on sugarcane-A diversity of assessment scales. Soil and Tillage Research, 223, 105469. [CrossRef]

- Braunbeck, O.A, and Magalhães, P.S.G. (2014). Technological evaluation of sugarcane mechanization. In Sugarcane bioethanol for Productivity and Sustainability. Cham: Edgard Blücher. pp. 451 - 464. São Paulo.

- de Maria, I. C., Drugowich, M. I., Bortoletti, J. O., Vitti, A. C., Rossetto, R., Fontes, J. L., ... & Margatho, S. F. (2016). Recomendações gerais para a conservação do solo na cultura da cana-de-açúcar. Campinas: IAC.. https://www.iac.sp.gov.br/publicacoes/arquivos/iacbt126.pdf.

- Ferreira, L. R. P. and Ferreira, M.N. (2015). Case study: Application of seedbed making in sugarcane fields - Estudo de caso: Aplicação de canteirização em canaviais. In: Processos agrícolas e mecanização da cana-de-açúcar. Cham: Sociedade Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola. pp. 487 - 503.

- de Campos, M., Rossato, O. B., Marasca, I., Martello, J. M., de Siqueira, G. F., Garcia, C. P., ... & Crusciol, C. A. C. (2022). Deep tilling and localized liming improve soil chemical fertility and sugarcane yield in clayey soils. Soil and Tillage Research, 222, 105425. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, P. A. L., Galindo, F. S., Oliveira, C. E. D. S., Jalal, A., Mortinho, E. S., Fernandes, G. C., ... & Teixeira Filho, M. C. M. (2022). Inoculation with plant growth-promoting bacteria to reduce phosphate fertilization requirement and enhance technological quality and yield of sugarcane. Microorganisms, 10(1), 192. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G. C., Rosa, P. A. L., Jalal, A., Oliveira, C. E. D. S., Galindo, F. S., Viana, R. D. S., ... & Teixeira Filho, M. C. M. (2023). Technological quality of sugarcane inoculated with plant-growth-promoting bacteria and residual effect of phosphorus rates. Plants, 12(14), 2699. [CrossRef]

- Ning, T., Liu, Z., Hu, H., Li, G., & Kuzyakov, Y. (2022). Physical, chemical and biological subsoiling for sustainable agriculture. Soil and Tillage Research, 223, 105490. [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, F. A., Moreira, S. G., Peixoto, D. S., Silva, J. C. R., Macedo, J. R., Silva, M. M., ... & Nunes, M. R. (2023). Lime incorporation up to 40 cm deep increases root growth and crop yield in highly weathered tropical soils. European Journal of Agronomy, 144, 126763. [CrossRef]

- Enesi, R. O., Dyck, M., Chang, S., Thilakarathna, M. S., Fan, X., Strelkov, S., & Gorim, L. Y. (2023). Liming remediates soil acidity and improves crop yield and profitability-a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Agronomy, 5, 1194896. [CrossRef]

- Szczepanek, M., B?aszczyk, K., & Piekarczyk, M. (2025). The Spatial Distribution of Nutrients in the Soil, Their Uptake by Plants, and Green Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Yield Under the Strip-Tillage System. Agronomy, 15(2), 382. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C. A., de Camargo, R., de Sousa, R. T. X., Soares, N. S., de Oliveira, R. C., Stanger, M. C., ... & Lemes, E. M. (2021). Chemical and technological attributes of sugarcane as functions of organomineral fertilizer based on filter cake or sewage sludge as organic matter sources. PLoS one, 16(12), e0236852. [CrossRef]

- Yarahmadi, F., Landi, A., & Enayatizamir, N. (2023). Effects of Filter Cake, Bagasse and Chemical Fertilizers Application on Some Quantitative and Qualitative Characteristics of Sugarcane. Iranian Journal of Soil and Water Research, 54(5), 811-827. [CrossRef]

- Elhaissoufi, W., Ghoulam, C., Barakat, A., Zeroual, Y., & Bargaz, A. (2022). Phosphate bacterial solubilization: a key rhizosphere driving force enabling higher P use efficiency and crop productivity. Journal of Advanced Research, 38, 13-28. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P., Das, S., Shankhdhar, D., & Shankhdhar, S. C. (2021). Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms: mechanism and their role in phosphate solubilization and uptake. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 21(1), 49-68. [CrossRef]

- Aye, P. P., Pinjai, P., & Tawornpruek, S. (2021). Effect of phosphorus solubilizing bacteria on soil available phosphorus and growth and yield of sugarcane. Walailak Journal of Science and Technology (WJST), 18(12), 10754-9. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. M., Pimenta, L. S., Qi, X., & JBN Cardoso, E. (2022). Economic gains using organic P source and inoculation with P-solubilizing bacteria in sugarcane. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, 27, 101-107. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, I. N., de Souza, Z. M., Bolonhezi, D., Totti, M. C. V., de Moraes, M. T., Lovera, L. H., ... & Oliveira, C. F. (2022). Tillage systems impact on soil physical attributes, sugarcane yield and root system propagated by pre-sprouted seedlings.

- Masnello, O.D. & Molin, J.P. Tipos de pilotos automáticos para máquinas agrícolas. Cultivar Máquinas, 08 jan. 2021. https://revistacultivar.com.br/noticias/tipos-de-pilotos-automaticos-para-maquinas-agricolas.

- Topcueri, M., Keskin, M., & ?ekerli, Y. E. (2024). Efficiency of GNSS-based tractor auto steering for the uniformity of pass-to-pass plant inter-row spacing. Tekirda? Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi, 21(1), 46-63. [CrossRef]

- Sanches, G. M., Magalhães, P. S., Remacre, A. Z., & Franco, H. C. (2018). Potential of apparent soil electrical conductivity to describe the soil pH and improve lime application in a clayey soil. Soil and Tillage Research, 175, 217-225. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A. P., Umezu, C. K., Polania, E. C. M., Dias Neto, A. F., Rossetto, R., & Albiero, D. (2022). Sensor-based technologies in sugarcane agriculture. Sugar Tech, 24(3), 679-698. [CrossRef]

- Som-Ard, J., Atzberger, C., Izquierdo-Verdiguier, E., Vuolo, F., & Immitzer, M. (2021). Remote sensing applications in sugarcane cultivation: A review. Remote sensing, 13(20), 4040. [CrossRef]

- Canata, T. F., Wei, M. C. F., Maldaner, L. F., & Molin, J. P. (2021). Sugarcane yield mapping using high-resolution imagery data and machine learning technique. Remote Sensing, 13(2), 232. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos L., A. C., Picoli, M. C. A., Duft, D. G., Rocha, J. V., Leal, M. R. L. V., & Le Maire, G. (2021). Empirical model for forecasting sugarcane yield on a local scale in Brazil using Landsat imagery and random forest algorithm. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 184, 106063. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, K. J., M. M. I. F. Rolim, R. P. Gomes, L. L. A. de Lima, and P. F. S. Ortiz. (2021). Numerical analysis applied to the study of soil stress and compaction due to mechanized sugarcane harvest. Soil and Tillage Research 206: 104487. [CrossRef]

- Ferraz Dias Neto, A., Bazo Bergamim, I., de Freitas Gonçalves, F. R., Rossetto, R., & Albiero, D. (2024). Use of Vegetation Activity Index for Evaluation of L-Alpha Amino Acid Treatment in Sugarcane. Agriculture, 14(11), 1877. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, J. C. S., Speranza, E. A., Antunes, J. F. G., Barbosa, L. A. F., Christofoletti, D., Severino, F. J., & de Almeida Cançado, G. M. (2023). Development and validation of a model based on vegetation indices for the prediction of sugarcane yield. AgriEngineering, 5(2), 698-719. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, K. J., Rolim, M. M., de Lima, R. P., Cavalcanti, R. Q., Silva, Ê. F., & Pedrosa, E. M. (2021). Soil physical indicators of a sugarcane field subjected to successive mechanised harvests. Sugar Tech, 23, 811-818. [CrossRef]

- Grande, L. H. Q., dos Santos, J. K., Pereira, M. B. N., da Silva, L. H. A., Muniz, L. F., Bolonhezi, D., ... & de Moraes, M. T. (2025). Modelling sugarcane root elongation in response to mechanical stress as an indicator of soil physical quality. Experimental Agriculture, 61, e3. [CrossRef]

- CONAB - COMPANHIA NACIONAL DE ABASTECIMENTO. Série histórica das safras. Março de 2025. https://www.conab.gov.br/info-agro/safras/serie-historica-das-safras/itemlist/category/892-cana-de-acucar-area-total.

- Prabhu, N., Borkar, S., & Garg, S. (2019). Phosphate solubilization by microorganisms: overview, mechanisms, applications and advances. Advances in biological science research, 161-176. [CrossRef]

| Context/Conditions | Key Evidence | Implication for SSTC | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanized harvesting; wheels/tracks comparison; transshipment traffic | Lateral propagation of transshipment-induced stresses reaching the planting row; tracks reduce surface deformation | Bed width = 0.60 m (1.50 m – 0.90 m lateral influence); keep traffic confined outside the mobilized zone | [15] |

| Prediction of stresses and compaction risk in sugarcane | Harvester-transshipment sets exceed σP and propagate stress bulbs in the profile; higher risk under high moisture | Prerequisite: CTF to concentrate damage; avoid traffic over the row; adjust operational windows | [10,11] |

| Root system distribution | 80% of roots in 0–0.40 m and up to 0.30 m from the row center | Target depth for mobilization and inputs: 0–0.40 m | [17] |

| Compaction risk in infield transport | Stresses of 275–595 kPa; irreversible compaction when σP is exceeded | Reinforces fixed traffic lanes and exclusion of traffic over the bed | [13] |

| Hydrological performance under SSTC | Infiltration 278 vs 120 mm h−1 (bed vs track); roots up to 1.33 m at 120 DAP | Functional benefit of 0.60 m (width) × target 0–0.40 m (depth) geometry under CTF | [19] |

| Axis | Parameter | Value / Window | Practical Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning and Diagnosis | Chemical profile sampling | 0–0.60 m | pH, V% and available P; use map for site-specific prescription |

| CTF | Lane delimitation | GNSS/RTK | Permanent traffic outside the planting row |

| Bed Geometry (SSTC) | Mobilized width | 0.60 m | Derived from spacing (1.50 m) and lateral propagation (0.90 m) |

| Bed Geometry | Target depth | 0–0.40 m | Zone of highest root density |

| Chemical Correction | Lime | According to technical criteria based on soil analysis | 75% on the surface + 25% in the subsoil via ducts |

| Chemical Correction | CaO / MgO | According to technical criteria based on soil analysis | Localized application as per subsoil analysis |

| Filter cake/compost | Applied dose | According to the chemical characteristics of the material | Homogenize with rotary hoes |

| Bioactivation (PSM) | Consortium | Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Penicillium | Prefer strains adapted to local soil |

| Bioactivation (PSM) | Concentration | 108–109 CFU mL−1 | Liquid or solid application in the furrow |

| Monitoring | Chemical | Annual | Review need for amendments every 2 years |

| Monitoring | Physical | ρb and SR at 0–0.40 m | Assess effectiveness and trigger |

| Technological Support | Sensing | Moisture, conductivity, drones | Map variability and prescribe locally |

| Indicators | Performance | Yield, diesel, emissions, costs | Evaluate time series |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).