1. Introduction

According to the United Nations [

1], the population of older adults worldwide is expected to increase significantly by 2050. As a result, the demand for emotionally intelligent systems to support elderly well-being will grow, especially given the projected shortage of caregivers and the increased vulnerability of older adults to verbal and psychological mistreatment [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] . Facial expression recognition systems can assist in detecting depression in elderly individuals and recognizing diseases in their early stages, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s diseas[

7,

8,

9]. In this context, facial expression recognition (FER) has emerged as a promising technology for providing emotional support and health monitoring.

Considerable research has been conducted on the recognition of emotions through facial expressions. However, most of these studies focused primarily on the younger population, paying less attention to the elderly. Deep learning-based FER studies are mainly performed on datasets such as CK+ [

10], JAFFE [

11], and FER13 [

12], which include only youthful faces [

13,

14,

15]. These studies have not addressed the challenges associated with recognizing expressions in aging populations. Deep wrinkles, folds, and changes to bone and skin structure affect the interpretation of emotional expressions [

16,

17,

18]. Most previous studies on facial emotion recognition have been interested in solving FER problems such as occlusion and lighting and treating expression recognition as a classification problem [

19]. However, the influence of aging on expression recognition performance remains largely unexplored.

In this paper, our approach leverages advanced attention mechanisms and squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks to enhance feature extraction in elderly faces, where wrinkles and age-related changes often obscure emotional signals. This proposed architecture improves classification accuracy by highlighting important expression features while addressing the unique challenges posed by aging. Specifically, we utilizes depthwise separable convolution layers instead of standard convolutions to reduce model complexity. The integration of SE blocks further enhances the extraction of salient features relevant to facial expressions in older adults. This combination helps to capture important features of emotions effectively, even in the presence of age-related variations. By developing a model that can accurately detect emotions in elderly individuals, this research has the potential to revolutionize eldercare, allowing for more effective emotional monitoring in nursing homes [

20,

21,

22].

One of the main contributions of this paper is the evaluation of multiple pre-trained models like VGG16 [

23], MobileNet [

24], ResNet50 [

25], DenseNet121 [

26], Xception [

27], and EfficientNetB0 [

28] to classify facial expressions in elderly individuals. This approach improves recognition accuracy while addressing the problem of insufficient data. We specifically employ a combination of depthwise and separable convolution layers along and SE modules to highlight important features and better capture the unique traits of aging faces, which improves the representation of facial expressions. Our contributions are summarized as follows:

The SE block is added to the last depthwise separable convolution layer to help the model focus more on the important channels. This refinement improves performance on challenging facial expressions, particularly in elderly subjects where age-related features may lead misclassifications.

By incorporating an attention mechanism, the network can concentrate on significant parts of the face, mitigating the impact of wrinkles that make it harder to accurately identify emotions.

Using depthwise separable convolutions keeps the design efficient in terms of computation while still capturing detailed features from the facial images.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section II reviews recent literature related to facial expression recognition (FER), particularly focusing on elderly populations and the application of transfer learning and attention mechanisms. Section III describes the proposed method, which involves transfer learning models, a squeeze-and-excitation module, and a straightforward explanation of depthwise separable convolution. Section IV provides a comparative analysis of our experimental results, with an ablation study and t-SNE visualization of the proposed method. Finally, Section V concludes the paper and presents future perspectives.

2. Related Works

Facial expression recognition (FER) in elderly individuals has recently attracted increased attention due to its potential applications in health monitoring and assistive technologies. A recent review by Gaya-Morey et al. [

29] confirms that while deep learning especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has achieved strong performance in general FER tasks, limited research has addressed elderly populations, largely due to the lack of aging-related samples in FER datasets. However, a few studies have addressed the problem of facial expression recognition in the elderly automatically [

30].

A. Caroppo et al. [

31] proposed a deep learning approach using a stacked denoising auto-encoder followed by supervised fine-tuning. Their model achieved 88.2% accuracy across six emotion classes and 93.3% accuracy for a binary classification (happy vs. neutral) using the FACE and Lifespan datasets. In the work of N. Lopas et al. [

32], the features of the face where extracted using a Gabor filter and sent to a multiclass support vector machine to analyze FER in both young and elderly groups. Their results show that elderly participants achieved

,

, and

accuracy for neutral, happy, and sad expressions, respectively, while younger subjects achieved

,

, and

for the same categories. This difference is explained by the influence of aging on automatic facial expression recognition, which requires considering the age impact on FER applications. In the study by Nora Algaraawi et al. [

33],LBP responses were used to compare facial expressions among young-neutral, young-happy, and old-neutral faces. The young-happy and old-neutral faces exhibited similar features because of wrinkles and decreased muscle elasticity,causing misclassifications. The appearance of deep wrinkles can trick the classification of emotions. For example, older neutral faces exhibited features similar to younger facial expressions [

34]. Some expressions, such as anger and disgust, may share common characteristics due to facial deformation with aging, causing significant difficulty in distinguishing between facial expressions [

35]. As a result, traditional appraoches like local binary pattern (LBP) [

36], histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) [

37], and optical flow (OF) [

38] might not be good enough to capture the important features of expressions shown by older adults.

In contrast, deep learning methods have recently gained prominence in computer vision applications, outperforming handcrafted methods [

39,

40,

41,

42]. To further enhance the performance of convolutional neural networks , transfer learning techniques are used to boost the performance of a CNN model by transferring knowledge from a pre-trained model on a sizeable dataset to a new task [

43]. This technique helps to overcome the problem of insufficient data [

3]. Moreover, applied transfer learning is more effective than training the model from scratch due to the capability of transfer learning in extracting basic features correctly through the early layers of the network [

44]. Wikanningrum et al. [

45] studied transfer learning from medium-sized datasets to improve lightweight CNN performance on FER. Hung et al. [

46] contribute to solving the problem of small datasets by designing the Dense_FaceLiveNet framework, a two phases of transfer learning based on the DenseNet model that improved test accuracy from

to

. Ning et al. [

39] demonstrate that fine-tuning GoogLeNetv2 yielded better representation of emotional features in static images due to its capacity to generalize from limited data. In another exapmle, Jia et al. [

47] suggest a facial expression recognition (FER) model that combines patch-based feature extraction with attention mechanisms to improve performance under challenging conditions, reaching an accuracy of 95.55%.

However, CNNs have limitations in performing feature aggregation and transformation. Convolutional operations utilize a kernel that strides over the entire input image and combines local features from various regions. Conversely, transformation involves applying non-linear functions to the aggregated features to learn complex data. In the context of facial emotion recognition in older adults, emotional cues are confounded by wrinkles. Therefore, highlighting expression-specific details becomes essential to accurately identify the features of the expression.

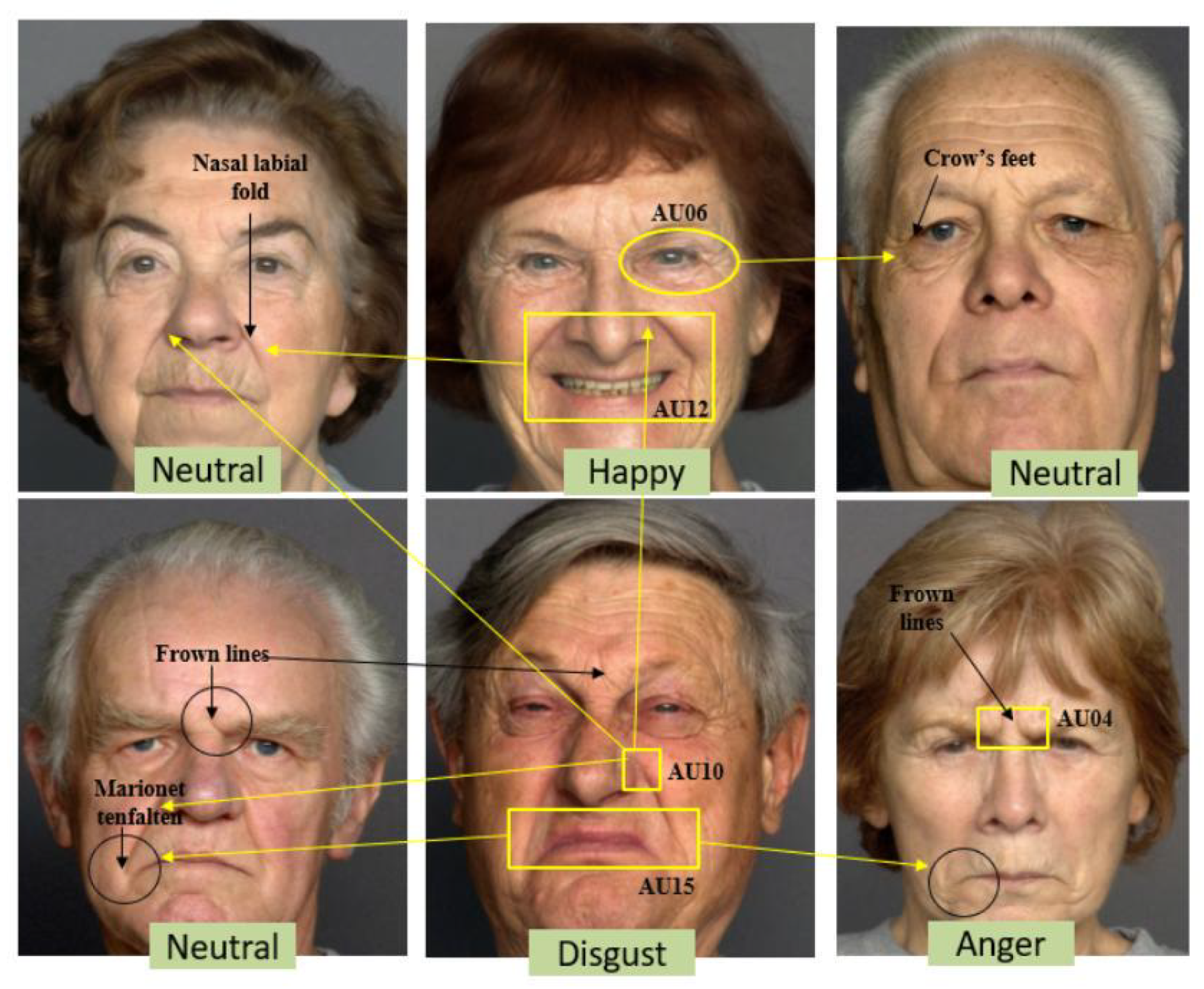

Figure 1 provides an illustrative example of a resemblance between wrinkles and facial expression features according to FACS action units [

48]. However, a general convolution operation considers the entire facial region as an input failing to focus on lovalized expression regions [

49]. Identifying emotions in aging faces requires a more targeted approach to capture subtle features specifically related to emotional expression.

Integrating attention mechanism into CNNs allows the highlighting of salient facial regions and assigns higher attention weights to the essential facial regions [

40,

49]. This is particularly relevant in elderly FER, where wrinkles can obscure emotion-specific cues. According to the work of Li et al. [

19], the attention mechanism enhances the weights of relevant features and improves facial expression recognition accuracy. This study proposed a dual-branch attention model using VGG16 and integrating LBP features demonstrating improved recognition rate. Fernandez et al. [

50] introduced a complete network design using an attention model to better understand the input image and significantly improved the classification perfomance. Similarly, Xue et al. [

51] proposed a transformer based FER model that combines CNNs-extracted feature with MultiHead Self-Attention Dropping (MSAD) to drop irrelevant facial parts. For depression recognition, Pan et al. [

52] created STA-DRN model, incorporating a ResNet backbone with spatial attention to improve pixel-level feature associations. Zhou et al. [

53] proposed a memory attention mechanism for deep depression representation using residual network module ResNet, while the attention module works as a pooling layer to address appearance and pose variation. Xiaohan et al. [

40] employed hierarchical transformers with local self-attention in each system block to identify important features from both local and global facial regions. Liu et al. [

54] used Vision Transformers (ViT) with patch-based attention with pretrained ResNet-18 for facial expression recognition under occlusion, the ViT helped the system focus on important areas of the image while ignoring blocked parts. While Zhao et al. [

55] proposed a Hierarchical Attention Network combined with a Progressive Feature Fusion strategy that capture both local and global facial features. Many recent studies have integrated CNNs with attention mechanisms to improve FER performance [

41,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. However, most of these studies focus on younger adults and use datasets like CK+ [

10], JAFFE [

11], and FER13 [

12], Oulu-CASIA[

63], RAF-DB[

64], and AffectNet[

65], which lack elderly subjects.o datasets specifically contain older adults.

A lot of research has focused on automatic facial emotion recognition using advanced deep learning methods, including transfer learning, fine-tuning and attention mechanism [

66,

67,

68,

69]. As regular CNNs continue to struggle with recognizing aged facial expressions, researchers are motivated in attention-based mechanisms to improve pretability and focus [

19,

70,

71,

72,

73]. Despite these advances, the challenge of recognizing facial emotions in the elderly remains unresolved. Facial expression traits changes with age make axpression traits difficult to identify and harder to distinguish [

16]. The main goal of our study is to adress this gap by proposing an optimized architecture that combines transfer learning and attention mechanisms to enhance FER of elderly individuals, with practical potential for deployment in intelligent and embedded systems.

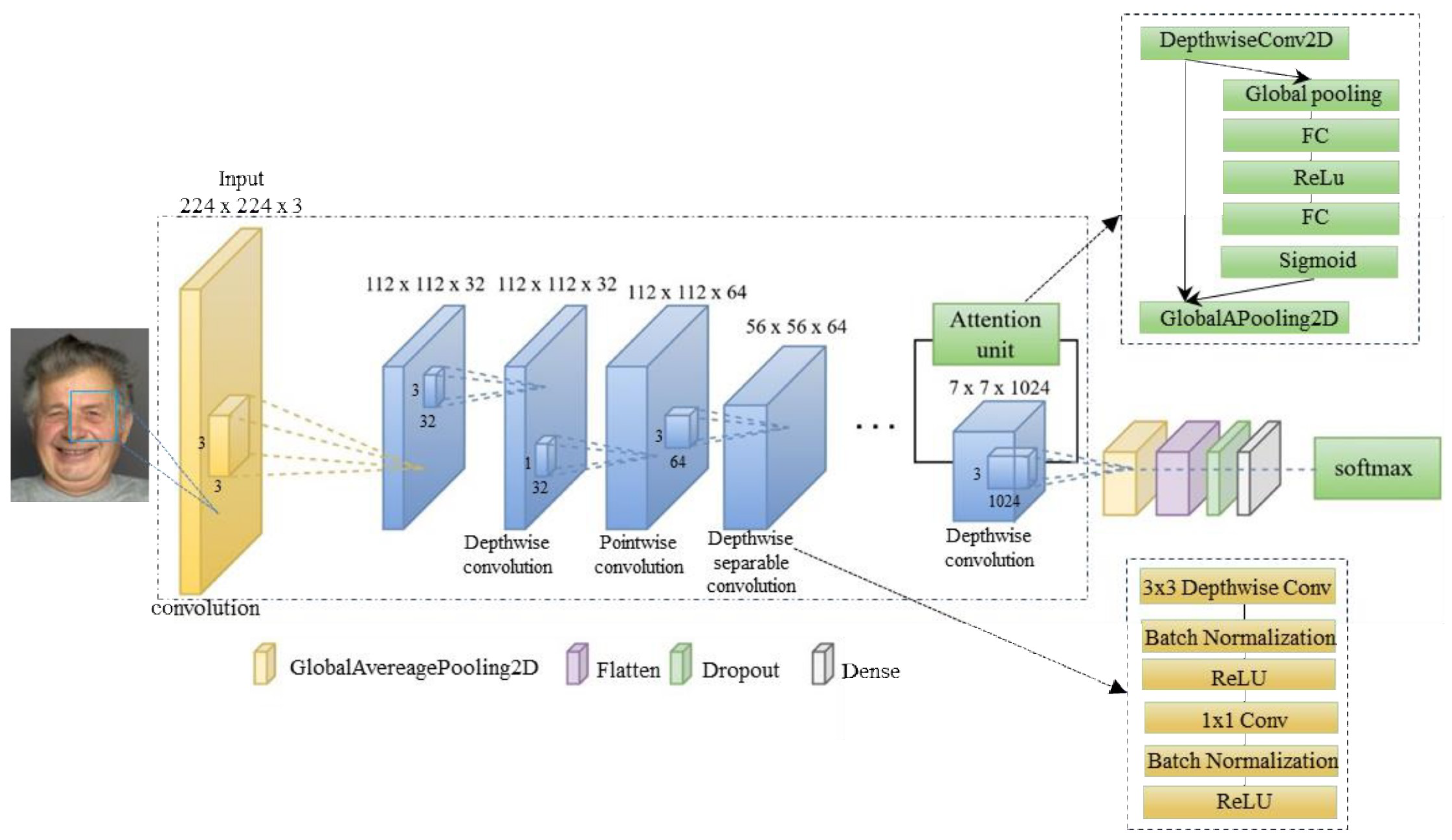

3. Proposed Method

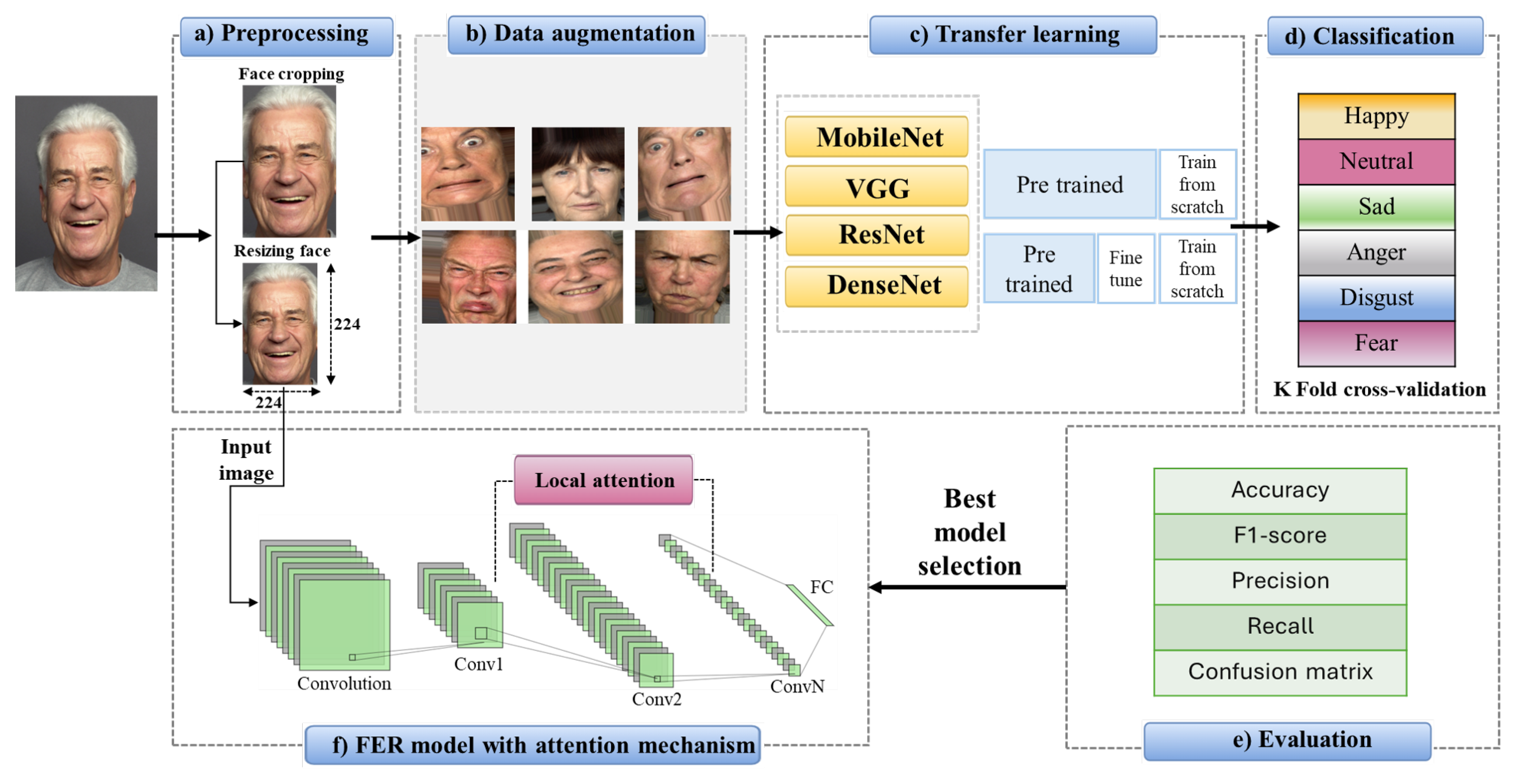

This paper proposes a convolutional neural network (CNN) model integrated with an attention mechanism to effectively recognize six basic emotions in elderly individuals: happiness, disgust, anger, fear, sadness, and neutrality. To enhance the CNN’s ability to capture relevant facial features affected by aging, we integrate a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module that adaptively recalibrates channel-wise feature responses. The proposed methodology consists of six sequential steps: (a) image preprocessing, (b) data augmentation, (c) feature extraction using transfer learning, (d) emotion classification, (e) performance evaluation, and (f) architectural enhancement through attention integration. A overview of this workflow is presented in

Figure 2. During preprocessing, faces are detected and cropped to a

image size to align with input dimensions required by the pre-trained models. Data augmentation techniques including horizontal flipping, rotation, and shifting are then applied to artificially expand the dataset and improve model robustness. Feature extraction is performed via transfer learning using several pre-trained networks: VGG16, MobileNet, ResNet50, Xception, EfficientNet, and DenseNet. These models were selected because of their simple network structure and proven learning performance on various tasks. Two main transfer learning strategies are applied in this study: (1) fine-tuning the pre-trained network to adapt to the specific FER task, and (2) using the pre-trained network as a fixed feature extractor followed by custom classification layers. Model performance are evaluated using five metrics: accuracy, F1-score, precision, recall, and confusion matrix analysis. Five-fold cross-validation strategy is employed to assess the recognition accuracy and select the best model performance. After selecting the best-performing model, we enhance its architecture by integrating SE blocks to improve features selection in expression-relevant regions. Fonally, a lightweight CNN model is proposed combining attention mechanism with depthwise separable convolutions to better extract the highlighted features of elderly facial expressions. The remainder of this section provides a detailed explanation of each methodological step: (a) image preprocessing, (b) data augmentation, (c) feature extraction via transfer learning, (d) Depthwise separable convolution of MobileNet, (e) Squeeze and excutation block, and (f) architecture design with attention integration will be described with detailed explanations.

3.1. Image Preprocessing

Facial expression recognition is a complicated task that requires efficient image preprocessing. Therefore, face cropping is essential to eliminate redundant information and background noise and highlight the significant features of facial expressions for efficient feature extraction. Next, we resized each image to a resolution of 224x224 pixels to align it with the input of the pre-trained models. Furthermore, the images were rescaled by dividing the input image by a value of 255 to normalize the data.

3.2. Data Augmentation

Data augmentation is crucial to enhance the robustness of FER deep learning models. Since facial expression datasets are usually small, data augmentation techniques are employed in this study to generate new images to solve the problem of insufficient data. The results show that using data augmentation methods like rotating, shearing, zooming, flipping horizontally, and resizing helps improve the model’s accuracy due to the limited size of public image-labeled databases. We employed the Keras ImageDataGenerator for various data augmentation methods, including horizontal flips, rotations, and shifts. These augmentation techniques allow the model to be trained on more data than the present dataset to enhance recognition accuracy [

43].

3.3. Transfer learning model for facial expression extraction

According to the study [

74], transfer learning aims to leverage prior knowledge from a source domain Ds to adjust the weight of existing knowledge in a target domain Dt, where Ds!=Dt. The source domain is a model weight already trained on a large-scale dataset used to migrate features to another model rather than training a model from scratch [

43]. Transfer learning comprises feature extraction and fine-tuning, which requires only limited domain-specific data to achieve good generalization [

75]. In this strategy, a base model trained on a large dataset is fine-tuned on a small target dataset to achieve better performance [

76]. Fine-tuning consists of training the model according to different strategies depending on the nature of the source and target domain [

76] retrained models are widely used due to the high computational cost of training from scratch, making fine-tuning a more practical approach, particularly when leveraging specialized hardware to accelerate the process. As shown in recent studies [

77], CNNs trained on large-scale datasets such as ImageNet [

78] are often adapted to new classification tasks by only modifying the final fully connected (FC) layers. The architecture of widely used CNN models such as Inception, ResNet, VGG, MobileNet, EfficientNet, and DenseNet differ in terms of layers depth, input resolution, and computational complexity. These differences directly affect model performance, influencing inference speed, parameter count, and feature representation capabilities.

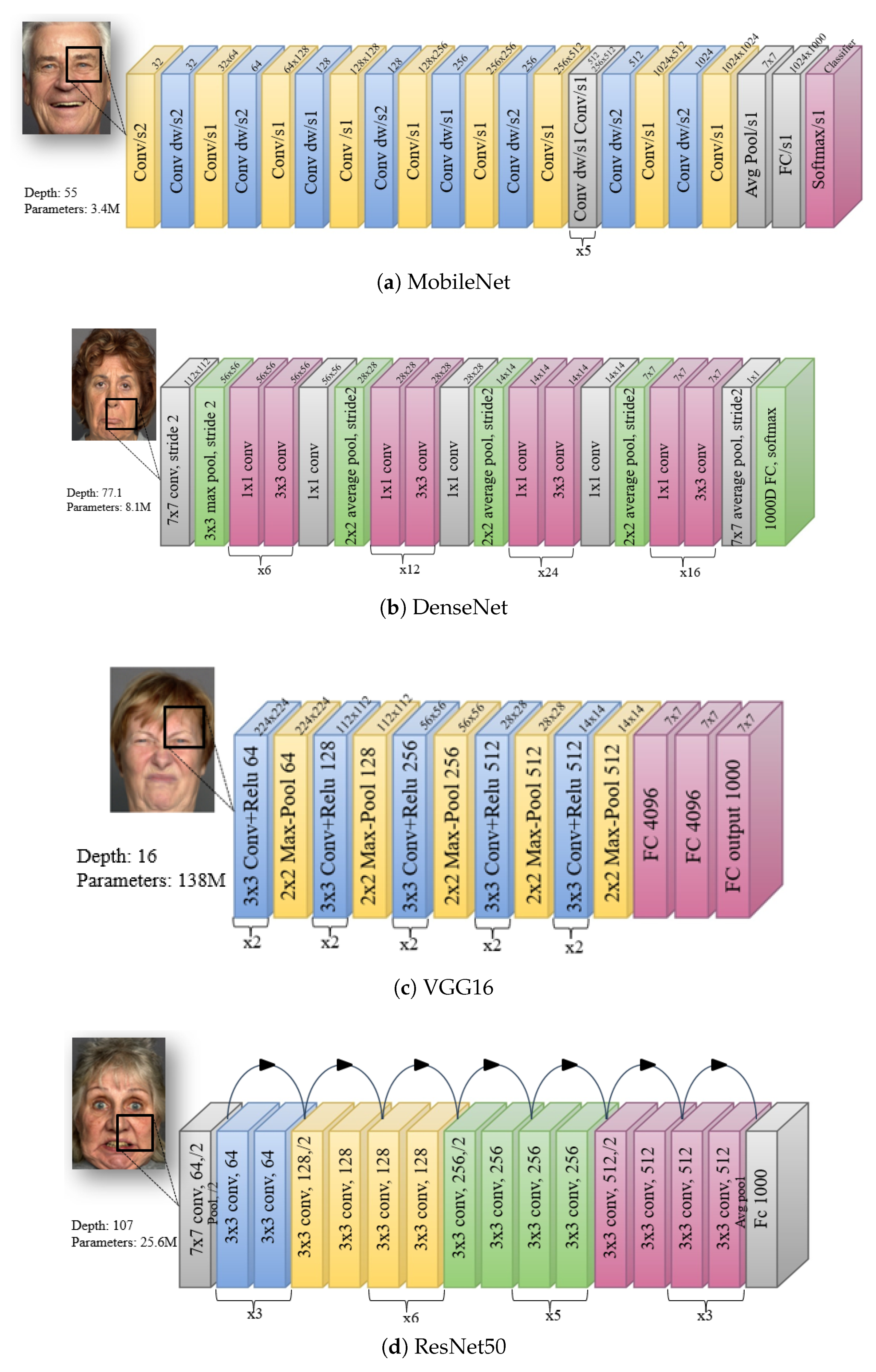

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of these models[

77]. There is generally a trade-off between inference speed and classification accuracy: faster models tend to be less accurate, while more accurate models are typically slower and more complex. In this study, we investigated the performance of four popular pre-trained models: VGG-16, MobileNet, ResNet50, and DenseNet121, for recognizing facial expressions. MobileNet is optimized for mobile and embedded applications due to its ability to balance between latency and accuracy [

24,

77]. VGG16 remains popular for its simplicity and deeper architecture consisting of five convolutional blocks with small

filters [

79]. ResNet50 leverages residual connections to address the degradation problem in deep networks [

80]. DenseNet introduces dense connectivity to slow down the gradient disappearance [

81]. The architectures of these models are illustrated in

Figure 3. Additionally, this study includes Xception and EfficientNetB0 for evaluation. Xception, also known as Extreme Inception, employes depthwise separable convolutions, making it similar to MobileNet since both are designed to be lightweight and efficient [

26]. EfficientNetB0 incorporates a balanced scaling approach to optimize performance with minimal resource usage[

28] .

3.4. Depthwise separable convolution of MobileNet

The MobileNet model employs depthwise separable convolutions composed of depthwise convolution and pointwise convolution. The depth-wise convolutions apply a single filter to each input channel. Then, a pointwise convolution with a kernel size of

is applied to combine these features across all channels. In contrast, a standard convolution filters the inputs and combines them into a new set of outputs in a single step. The cost of a standard convolution is as follows:

represent the input feature map.

is the kernel’s spatial dimension, M is the number of input channels, and N is the number of output channels. The computational cost of standard convolution depends on the number of inputs and output channels, the size of the kernel, and the feature map. MobileNet models address each of these terms and their interactions by reducing the cost. The MobileNet splits the filtering and the combination steps into two steps: depthwise convolution and pointwise convolution. The depthwise convolution performs filtering independently for each input channel, resulting in a computational cost of:

Compared to standard convolution, depthwise convolution is more efficient. However, depthwise convolution alone does not capture inter-channel information. To adress this, a pointwise convolution is applied, which uses a 1 × 1 kernel to combine the outputs of the depthwise convolution across channels. The computational cost of pointwise convolution can be calculated as follows:

The depthwise and pointwise convolutions are combined to create the depthwise separable convolution. The total cost is calculated as follows:

Compared with the standard convolution cost, the reduction factor is:

Since MobileNet employs depthwise separable convolutions, it reduces the computational cost by approximately 8 to 9 times compared to standard convolutions, making it well-suited for mobile and real-time applications.

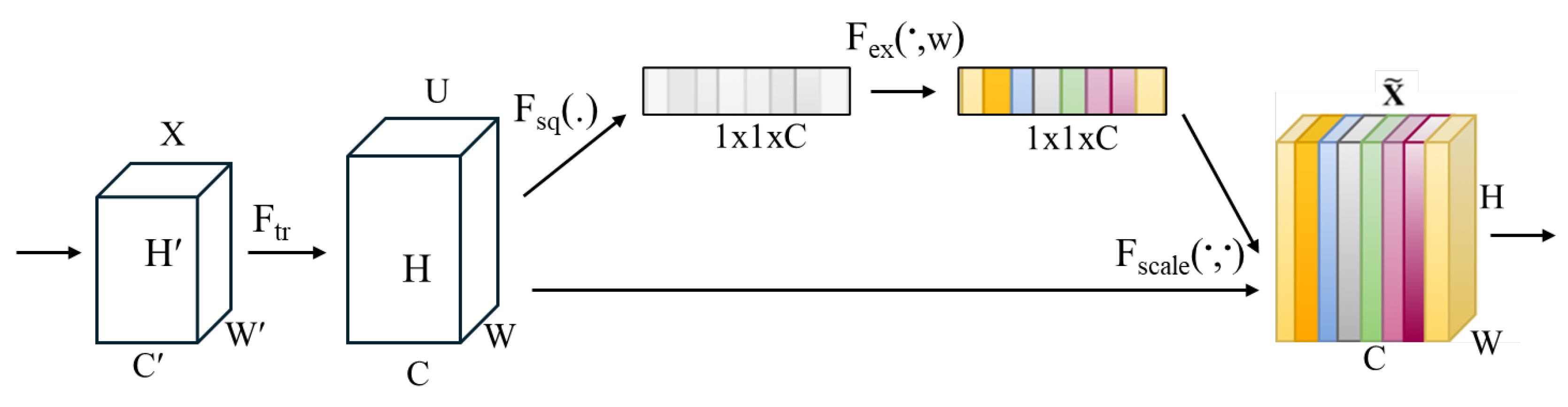

3.5. Squeeze and excitation block

The innovation of the squeeze and excitation block[

79] lies in its ability to focus on the most informative local features of facial expressions, while ignoring misleading features such as wrinkles that may create false characteristics in the feature representation. The SE network is integrated to the base model architecture to enhance feature quality. Modeling the correlation between the channels of the network convolution allows for improving the quality of representations of features. This mechanism can learn informative features and suppress less useful ones. The SE network (SENet) is constructed by a convolution transformation, a squeeze operation, and an excitation step followed by feature re-scaling, as presented in

Figure 4.

The transformation

is applied to map the input

to give the feature maps

to perform feature calibration.

denotes the convolution operator,

is a set of filter kernels, and

is the output where

The output features U are first passed through a squeeze operation. Generally, the input to this operation is a 3-D tensor of the shape . The squeeze operation is used to address the problem of channel dependencies, which refers to how different channels in the neural network interact with each other and can create limitations related to local receptive fields. A local receptive field occurs when a filter captures local patterns and considers only a limited region of the input data. Consequently, the transformation output (U) is limited in accessing information from other channels outside the local area.

The squeeze block’s purpose is to turn global spatial data into a feature descriptor by applying global average pooling, which simplifies the input size to

to create statistics for each channel. Formally, a statistic

is generated by shrinking U through its spatial dimensions

, such that the c-th element of

z is calculated by:

Thereafter, the aggregated feature map goes through an excitation block to calibrate the channel-wise information, which is the output of the squeeze operation. This step must satisfy two criteria: flexibility to learn nonlinear interaction between channels, and non-mutually exclusive relationships, which aim to allow multiple channels to be emphasized. We employ a simple gating mechanism with sigmoid activation to meet these criteria.

where

and

. A bottleneck with two fully connected (FC) layers is used to limit the model complexity and improve generalization. The dimensionality is reduced by the first FC layer, where

r is a hyperparameter and serves as the coefficient of dimensionality reduction. Finally, the system employs a ReLU activation. Then, the final output U is rescaled with activation s:

where

and

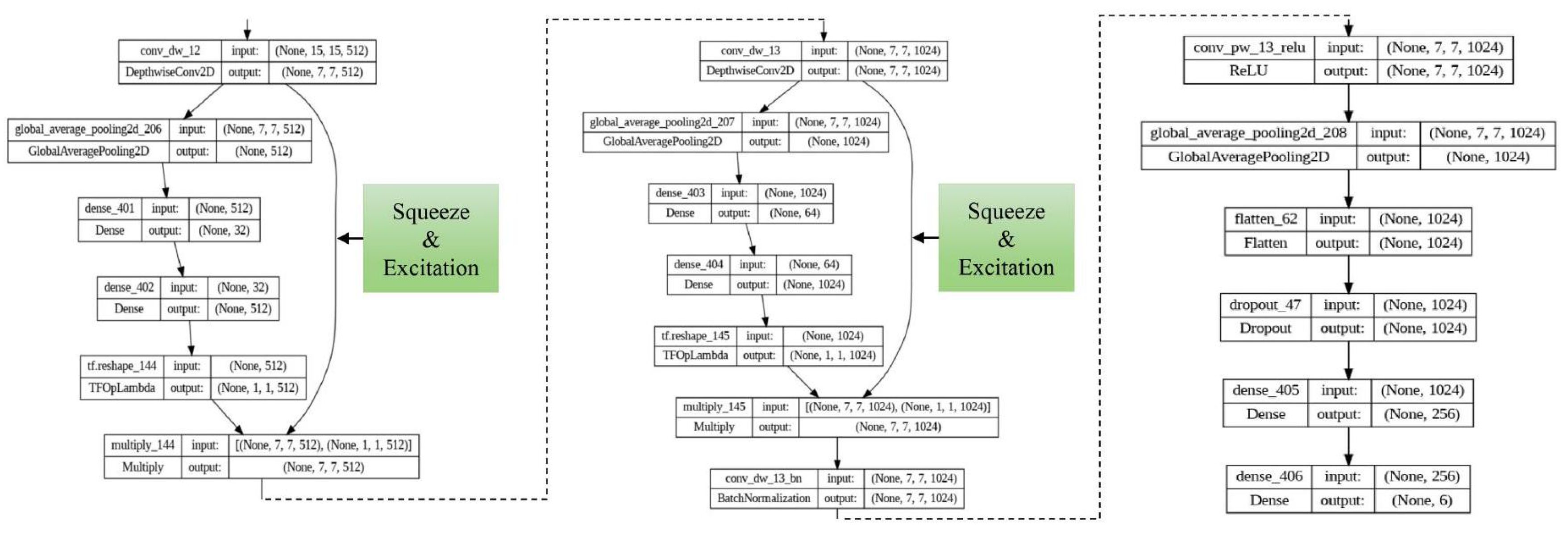

3.6. Network architecture of FER model with attention mechanism

This study introduces a modification to the standard MobileNet architecture by incorporating a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block into the final depthwise separable convolution layers. The traditional convolution operation processes the entire face region and captures spatial features across the face. However, this method cannot focus on the most discriminative local areas, which is crucial when dealing with elderly facial expressions. Wrinkles, for example, may resemble features of specific emotions, leading to misclassification.

To address this, we enhance MobileNet by integrating SE blocks to recalibrate the feature maps at the channel level. As depicted in

Figure 5, SE blocks are added to the final depthwise convolution layers. This enables the network to adaptively emphasize the most informative features based on global channel-wise statistics. The refinement allows the model to more effectively distinguish facial muscle movements from wrinkles and other age-induced changes. The SE mechanism dynamically adjusts the importance of each channel, focusing on the regions most relevant to elderly facial expression recognition, where features may overlap with aging traits.

The schematic of the enhanced architecture is illustrated in

Figure 6. In this architecture, the input to the model is an image with size of

, representing the cropped facial region of an elderly individual. This image goes through a

convolutional layer with a stride of 2, which lowers the image size and picks up basic features. This is followed by a series of depthwise separable convolutions layers. These consists of two steps: (1) depthwise convolution, which applies a single filter per input channel, and (2) pointwise convolution, which combines the outputs from the depthwise layers. This technique significantly reduces computational complexity while preserving the performance.

Next, the SE block is applied to the output of the final depthwise separable layer. This block recalibrates feature responses by explicitly modeling interdependencies between channels. The attention mechanism is applied to the depthwise convolution output of size before the final fully connected layers. It enables the model to focus more on informative and discriminative regions, such as the eyes and mouth, which are critical for expression recognition. The SE block includes three main steps: First, it uses global average pooling to summarize channel-wise information, followed by two fully connected layers with ReLU activation and sigmoid function. These weights are then used to rescale the original feature maps.

After the recalibration, the output from the attention mechanism is passed through a GlobalAveragePooling2D layer, followed by a Flatten layer and dense layers. The final classification layer use a softmax function to predict one of the six emotion categories.

Experimental results confirm that this combination of SE blocks with depthwise separable convolution layers of MobileNet enhances the feature representation and classification performance for elderly FER tasks, addressing the unique challenge of aging-related facial changes,while maintaining computational efficiency, making it well-suited for real-time and embedded system deployment.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed facial expression recognition (FER) method tailored for elderly individuals. We benchmark multiple deep learning models, including VGG16, MobileNet, ResNet50, DenseNet121, Xception, and EfficientNetB0. We conduct the experiments on the FACE database, a dataset for elderly facial expressions. Evaluations are performed using five-fold cross-validation and standard classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and confusion matrix. The proposed method integrates a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block into MobileNet, the best-performing baseline, to enhance feature representation. A We present a detailed ablation study and visualizations that use Grad-CAM and t-SNE to interpret model attention and feature distribution. Finally, we compare our method with state-of-the-art works to demonstrate the efficacy of our proposed method for FER tasks in the elderly.

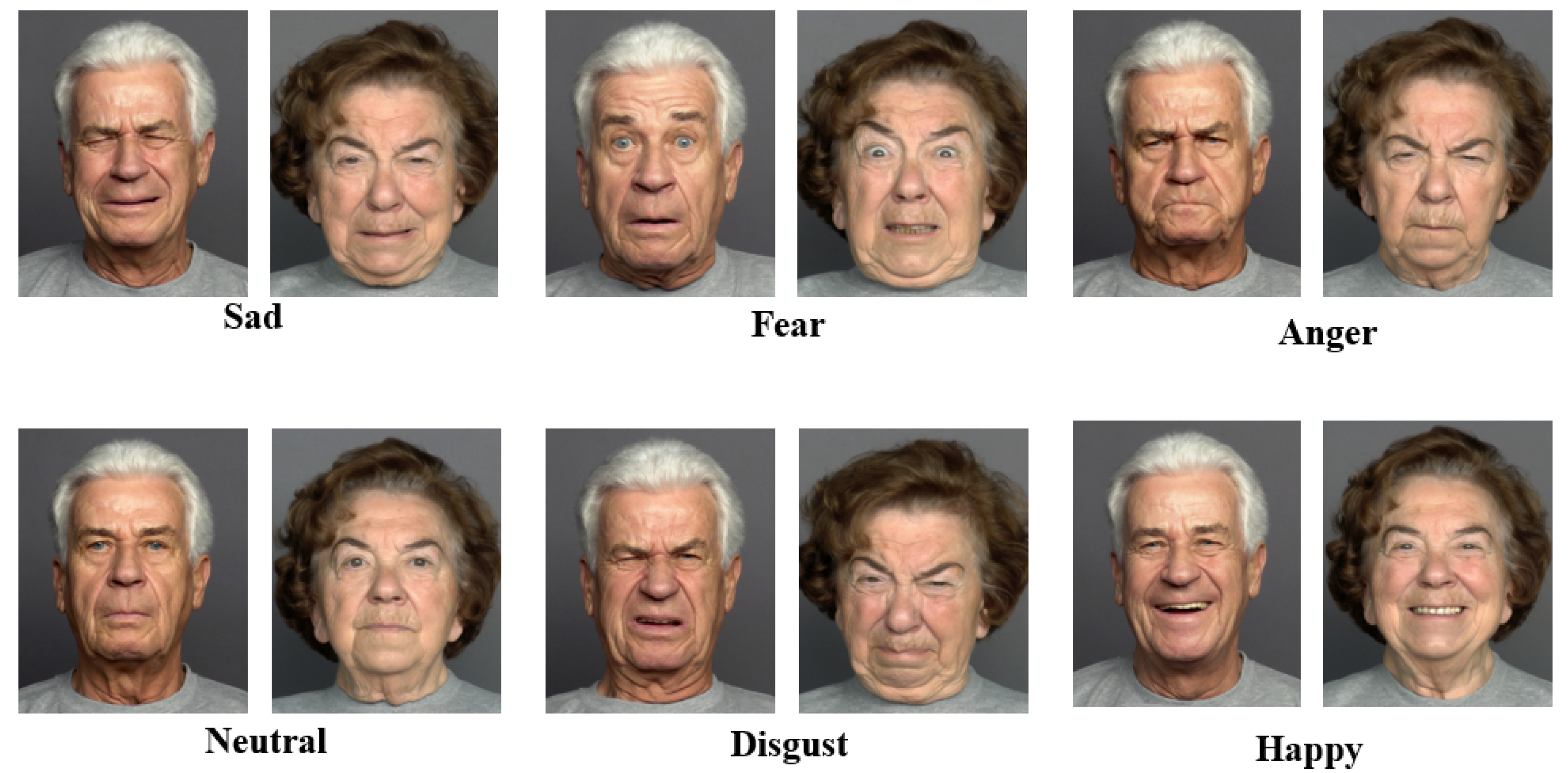

4.1. Dataset

The FACE database of facial expressions was used in this study [

82], a facial expression dataset containing both young and elderly subjects. Specifically, the subset used includes 57 older individuals (

M_age = 73.2 years, SD = 2.8; age range: 69–80). These facial models represented six basic emotions: happiness, sadness, anger, disgust, fear, and neutrality.

Figure 7 shows examples taken from the FACE database.

A total of 684 images were selected, comprising two representative emotional expressions per individual. Detailed statistics of the dataset and demographic characteristics are summarized in

Table 2.

The dataset used in this study comprises both publicly available and privately collected facial expression images. The private dataset was gathered with informed consent under ethical approval granted by the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Center for Lifespan Psychology, Berlin, Germany. Access to this dataset is restricted due to privacy considerations. The public portion of the dataset used in this study is available at

https://faces.mpdl.mpg.de/imeji/. The private dataset is not publicly available but may be accessed upon reasonable request and with appropriate institutional approval.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the classification performance of our models, we use the following standard metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score [

83]. Confusion matrices are generated to analyze the model’s behavior across emotion categories. The confusion matrix has four quadrants: True Positive (TP): Instances where the model correctly predicts the positive class. When the model predicts the negative class incorrectly, it is called a False-Negative (FN). When the model accurately predicts the negative class, it is said to be True-Negative (TN). False Positive (FP): Instances where the model incorrectly predicts the positive class. A multiclass confusion matrix comprises a square grid where rows and columns correspond to the various classes involved in the classification task. Each cell within this matrix denotes the number of instances associated with a particular pairing of predicted and actual class labels. The entries along the diagonal of the matrix indicate accurate predictions, whereas entries off the diagonal signify instances of misclassification.

Accuracy is a performance metric representing the ratio of correctly classified instances to the total number of instances. The accuracy is calculated as fol

Precision is a performance metric to measure the proportion of correctly predicted positive instances among all positive predictions. Precision focuses on the accuracy of positive predictions. Precision is calculated as follows:

Recall is a metric that measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all actual positive samples in the dataset. Recall is calculated as follows:

The F1 score combines both precision and recall. A high F1 score suggests that the model can achieve strong performance in both precision and recall. F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, calculated as follows:

4.3. Experimental Preparation and Assessment

The proposed model is implemented using the Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, and Keras libraries and trained on a Google Colab Pro environment equipped with a T4 GPU. For model optimization, we adopt Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) [

84] with a momentum of 0.9 and a learning rate of 0.0005. Early stopping is applied to prevent overfitting, and dropout is set to 0.1 to improve generalization. Categorical cross-entropy loss is used as loss function for multi-class emotion classification. The hyperparameters used during training are given in

Table 3.

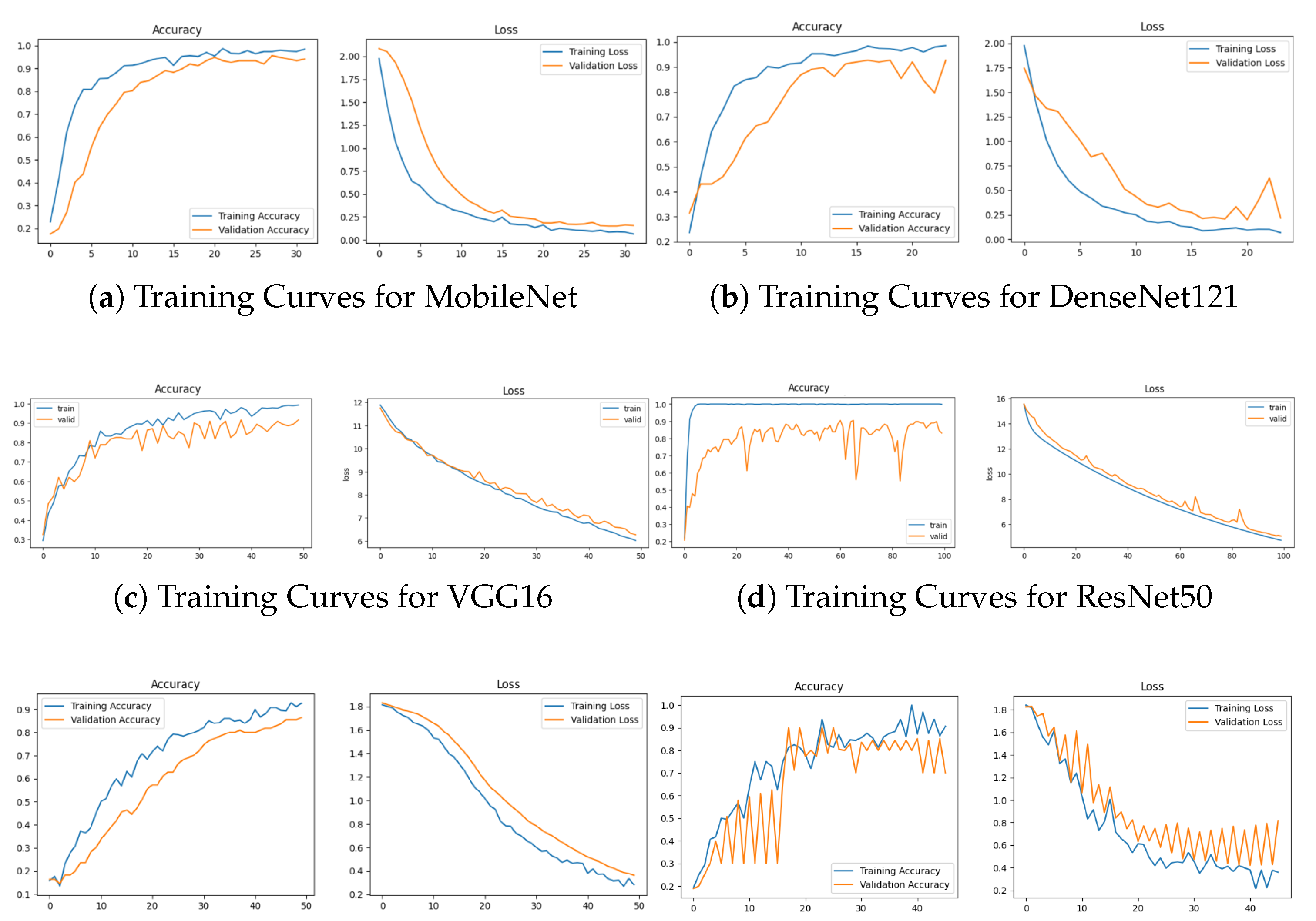

4.4. EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

The training of the transfer learning models is conducted using three strategies: total fine-tuning, partial fine-tuning (with early layers frozen), and fixed feature extraction. The parameters of each model are summarized in

Table 4.

Table 5 reports the training results for the six transfer learning (TL) models under these three strategies.

The results from the table demonstrate that total fine-tuning yields the best performance across all models. Notably, when fine-tuning the entire model, MobileNet performs better than the other models by achieving an accuracy of

. However, ResNet50 performs better when employing the partial fine-tuning method, achieving an accuracy of

. On the other hand, VGG16 was relatively poor compared to the different models. To select the best model, the observations consider metric performance, accuracy, and loss curves. Since fine-tuning the model entirely demonstrates better performance, we visualize the accuracy and loss curves presented in

Figure 8 to observe the changes during the training process.

For MobileNet (

Figure 3), the initial phase between epochs 0 and 5 indicates that the model is learning valuable features from the training data and improving its generalization to the validation set. Between epochs 5 and 15, both training and validation accuracies are high and close, suggesting that the model is converging well and performing effectively on both seen and unseen data. In

Figure 3, the validation accuracies were lower than the training accuracies, while the losses were high, indicating that the DenseNet121 model was not performing well. About the ResNet50 model (

Figure 3), it appears that the training and validation accuracy is reaching high values (close to

) as the epochs progress. However, these high accuracies might be an indication of overfitting. The training accuracy reaches close to 100%, indicating that the model can fit the training data very well. This is a sign of overfitting since the validation accuracy is not increasing as much as the training accuracy. For VGG16, the validation accuracy fluctuates, suggesting that the model may be overfitting unseen data. In

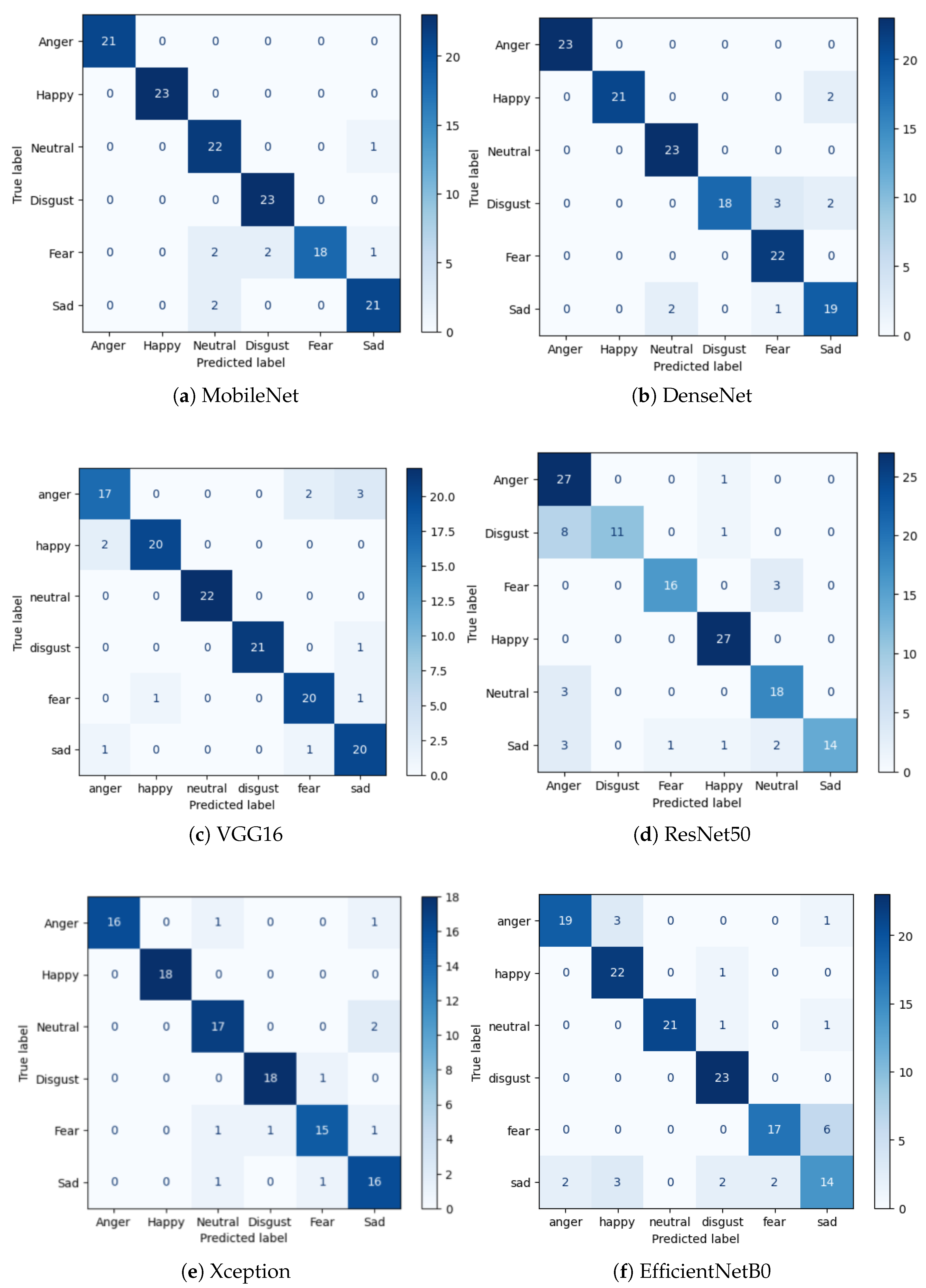

Figure 8, it appears that the EfficientNetB0 model training is fluctuating in both accuracy and loss across epochs, with significant variations in validation performance. For the Xception model, the training process showed a gradual improvement in both accuracy and loss across epochs. In the initial stages, the training accuracy started relatively low, but as training progressed, it consistently increased, reaching approximately 87.50% accuracy by the final epochs. Subsequently, the networks were compared using their confusion matrices and classification results, as shown in

Figure 9 and

Table 6.

The recall, F1-score, and precision obtained by fine-tuning MobileNet entirely are higher, with a value of 1.00 on angry, happy, and disgusted expressions.

In summary, the MobileNet model performed better overall, reaching a top accuracy of

when trained using the total fine-tuning method. As the epochs progressed, the training and validation accuracy increased, reaching high values, suggesting that the model is learning better representations. The MobileNet model comprises a simple architecture with a few parameters, as shown in

Table 4. It significantly reduces the number of parameters compared to a network using regular convolutions of equivalent depth. The simple architecture of this model and its low cost give better results than the other models with complex architecture. For a detailed explanation of the depthwise separable convolution used in MobileNet, please refer to the Methods section (Section II/d). Hence, fine-tuning the entire MobileNet allows for updating the low-level and depthwise separable layers to learn specific features of facial expressions. Because MobileNet was originally trained on the ImageNet dataset [

78], its features are not optimized for FER tasks, making complete fine-tuning essential. Facial expression datasets often have unique features that the pre-trained model might not well capture on more general datasets like ImageNet. Facial expression recognition usually involves capturing complex relationships between facial features. Fine-tuning the entire model allows the network to better adjust its internal representations to capture these intricate relationships.

4.5. DEEP FER MODEL WITH ATTENTION MECHANISM

MobileNet achieved the highest overall performance and was therefore selected as the base feature extractor in the proposed architecture (see

Table 5 and

Table 6). In the proposed implementation, the squeeze operation is global average pooling applied to the input tensor. Two fully connected layers use the squeezed output as their input during the excitation operation. The first dense layer reduces the dimensionality of the squeeze vector using the activation function ReLU. In contrast, the second dense layer maps back to the original number of channels using the sigmoid function. To adapt the model for emotion classification, the final layers were modified by replacing the top with a GlobalAveragePooling2D() to reduce the data dimensionality. Then, a Flatten() layer is added to convert the pooled feature maps into a one-dimensional tensor, followed by a fully connected layer with ReLU. The final layer consists of six units equal to the number of classes with softmax activation. We compared Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF) as classifiers to validate the proposed classifier’s effectiveness. The results are presented in

Table 7.

The model used with the SVM classifier shows different accuracy levels based on the kernel type: RBF (27.52%), Poly (27.27%), Linear (30.27%), and Sigmoid (20.9%). The combination with the RF classifier, with 100 estimators, achieves an accuracy of

. Both classifiers attain very low accuracy— less than

, demonstrating that the proposed method outperforms the other classifiers in terms of accuracy.

Table 8 shows the recognition accuracy of the proposed methods and different transfer learning models. Integrating the SE block into depthwise separable convolution improves accuracy, achieving

. We also assess the training time per epoch for each model as shown in

Table 8.

The training time of MobileNet and MobileNet+SE was the shortest among all the models. Moreover, MobileNet with and without SE exhibited similar convergence times, approximately 5.30 s and 6.90 s per epoch, respectively. Consistent with the findings of [

85] , integrating SE blocks in transfer learning models for autonomous systems, including the squeeze-and-excitation block in the model, demonstrated the shortest training time. This indicates that the SE block does not significantly increase the complexity of the model while maintaining excellent accuracy results. The comparison of the speed between MobileNet and MobileNet+SE shows that adding Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks to MobileNet did not noticeably slow it down; in fact, it actually got a little faster by 3.21%. The addition of SE blocks does not introduce significant computational overhead. The Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks add learnable parameters, but they also help recalibrate the feature maps, which could, in some cases, result in more efficient computations depending on the model and dataset. In contrast, ResNet50, DenseNet121, Xception, and VGG16 require a longer convergence time of

, and 8.5s per epoch. EfficientNetB0 requires a very long convergence time of 55.27s. The reason is that MobileNet, with its simple architecture, requires a smaller number of parameters and a smaller memory size, which speeds up the convergence time. Moreover, the SE network, integrated with depthwise separable convolution, has enabled the model to study expression features and improve recognition accuracy while maintaining convergence speed. The evaluation showed that adding Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks reduced the time it takes for the MobileNet model to make predictions by 3.21%, with MobileNet+SE averaging 132.897 ms, compared to 137.306 ms for the original model. This demonstrates that SE blocks enhance model performance and contribute to slightly faster inference, which is crucial for real-time applications.

4.6. ABLATION STUDY

In the ablation study, we analyze the effectiveness of the proposed method and evaluate the impact of integrating squeeze and excitation blocks.

Table 9 shows the performance results with and without the SE block.

By implementing the SE block to emphasize discriminative features in elderly facial expressions, the results show a notable improvement in accuracy from to . Specifically, the neutral expression’s precision, recall, and F1 scores are enhanced from , and to , and , respectively. The recall and F1 scores of fear expression have improved from 0.78 and 0.88 to 0.96 and 0.98 , respectively. For the sad expressions, all three metrics—precision, recall, and F1-score achieved a perfect score of 1.00. This improvements confirms that integrating SE enhances the model’s attention to relevant facial features, leading to more accurate classification across all emotion classes.

4.7. Visualization

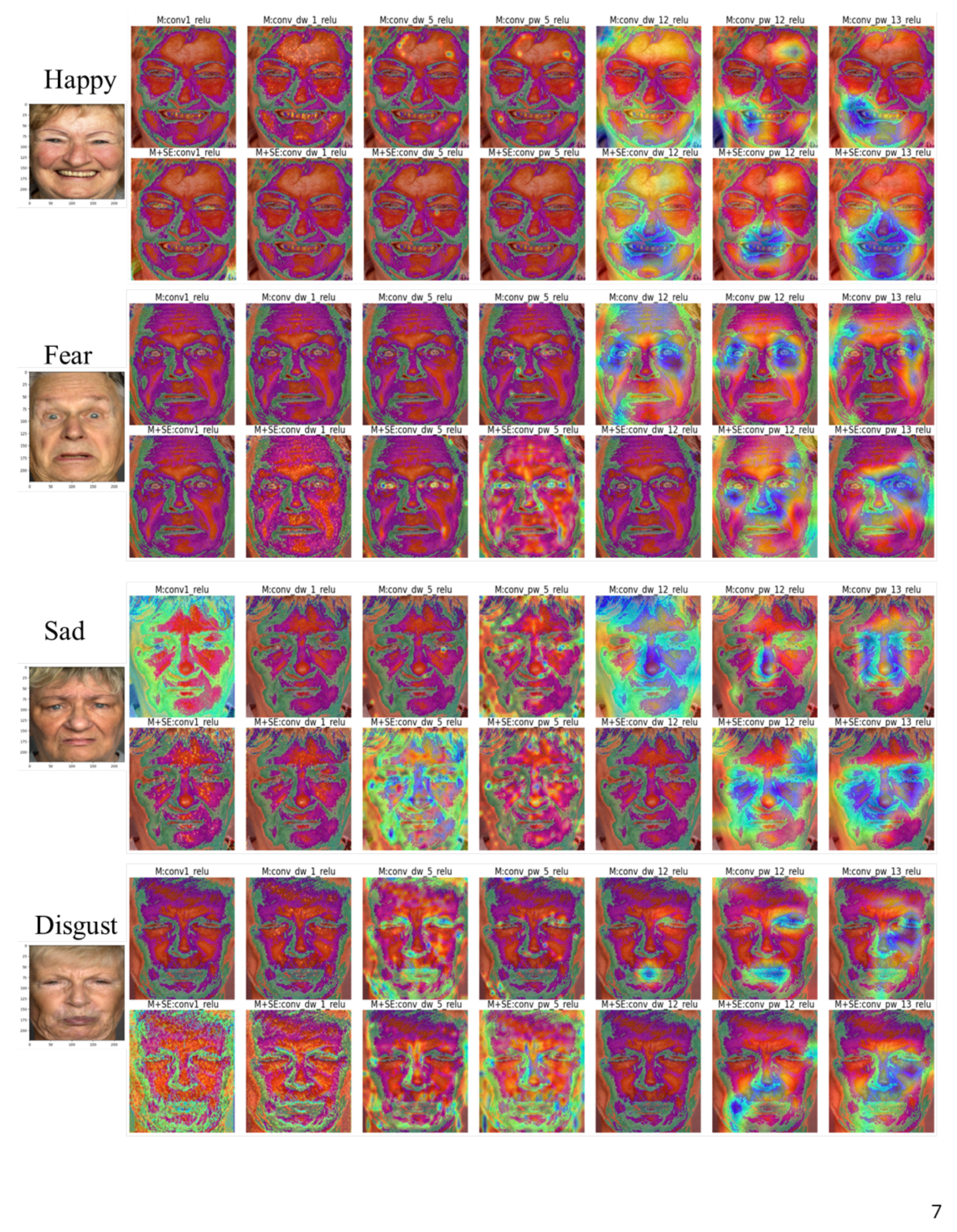

We compare the Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) visualizations between MobileNet and MobileNet+SE to demonstrate how the SE block in the MobileNet model improves its ability to focus on the most discriminative features for facial expression recognition. Grad-CAM is a visualization technique that highlights the regions in an image that contribute most to a model’s prediction. By generating heatmaps, grad-CAM allows for the interpretation of which areas of the face the model considers important for classifying emotions. This helps assess whether the SE block improves feature localization and attention. In

Figure 10, we examine different parts of the network to see how feature representation changes and how SE blocks help with feature localization as we go deeper into the network.

In the first two rows of

Figure 10, the Grad-CAM for the "Happy" expression shows that in the earlier layers, both MobileNet (M) and MobileNet+SE (M+SE) heatmaps have wide activations, highlighting basic features like edges and shapes. However, M+SE exhibits more concentrated focus around key regions such as the eyes and mouth, with reduced background noise compared to M. At deeper layers, which capture high-level features crucial for facial expression classification, M+SE heatmaps demonstrate a more localized emphasis on expression-relevant regions, including the mouth (smile) and eye wrinkles, which are relevant for recognizing a happy expression. Generally, at the final convolutional layers, the model without SE blocks shows a focus on important facial areas, but this focus varies between different samples, often highlighting just one area (like the cheeks or nose) and missing other important parts. In contrast, Grad-CAM results of the model with the SE block demonstrate better alignment with expression-related regions (e.g., eyes for surprise, mouth for disgust). Furthermore, SE blocks suppress noisy activations (e.g., on the background or irrelevant facial areas like cheeks). In

Figure 11, the results display the final Grad-CAM outputs, which directly compare attention focused on specific emotions. For surprise expressions, M+SE highlights the wide-open eyes and mouth, key indicators of surprise.

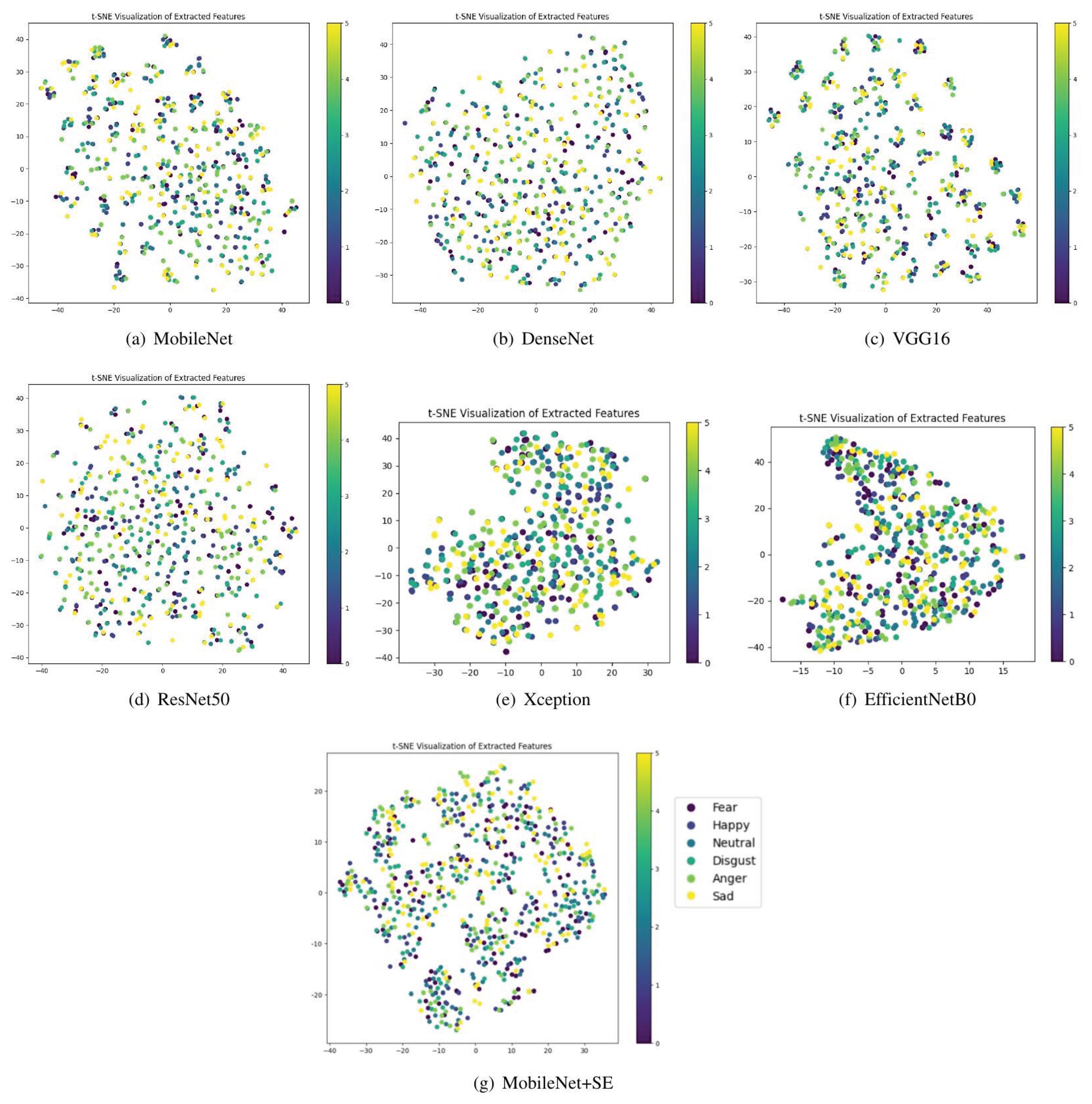

M, however, exhibits broader but less distinct activations, reducing its focus. For anger expressions, M+SE targets furrowed brows and tight lips, features strongly associated with anger. M’s activations spread over the face, including less relevant areas. For happiness, M+SE shows concentrated activations on the smile and the wrinkles near the eyes, which are highly expressive for happiness. M again shows wider but less precise activation patterns. For neutral expressions, M+SE focuses on balanced features such as the symmetry of the face, avoiding overemphasis on unnecessary regions. M spreads activations evenly, which may not enhance recognition for neutral expressions. These results indicate that SE blocks significantly enhance feature localization, producing more informative and interpretable Grad-CAM visualizations. The improved attention helps the model focus on relevant regions, potentially leading to higher accuracy in facial expression recognition tasks. Building on these observations, we further validate the effectiveness of our model through t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), as shown in

Figure 12.

By looking at the feature distribution on the FACE database, more effectively separates emotional classes, compared to the other transfer learning models. This result demonstrates the superior capacity of the proposed method to learn and discriminate the features of elderly facial expressions. This conclusion supports the findings from grad-CAM, where the SE blocks were shown to help the model focus on the most discriminative features, leading to better feature discrimination across different emotional categories.

4.8. Comparison with State of the Art

In this section, we conduct a comparison between our method and state-of-the-art solutions for emotion recognition in older adults through facial expressions.

Table 10 presents a detailed comparison between our proposed method and existing solutions.

We observed that our method outperforms the state-of-the-art by exploring six classes of emotions: anger, disgust, sadness, fear, happiness, and neutral. For instance, the proposed method achieves better results than Caroppo et al. [

31], who explore only two emotional classes: happy and neutral. Compared to Lopes et al. [

32], our model demonstrates the superiority of deep transfer learning over traditional machine learning approaches for elderly FER. Both works by P. Sreevidya et al. [

86] and Dou, S. et al. [

87] used CNN with LSTM and achieved less than 90%. These results indicate that transfer learning with an attention mechanism is efficient for facial expression recognition in older adults. Moreover, we extended the comparison to include recent attention-based FER models that, while not specifically designed for elderly faces, offer insight into alternative attention strategies. Fanglei Xue et al. [

51] employ Vision Transformers and Multihead Self-Attention Dropping (MSAD) to focus on local patches for FER. While TransFER uses transformers to pay attention to different parts of an image, our model adds Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks to the depthwise separable convolutions of MobileNet to better handle age-related changes in faces, like wrinkles, in older people. This makes our approach more suited to tackling FER challenges specific to older adults. In the work of Marrero et al. [

50], FERAtt uses attention-based CNNs to focus on expression-specific regions. Whereas FERAtt applies region-specific attention, our SE-based attention mechanism enhances feature recalibration in the depthwise convolution layers, making it more effective for dealing with the unique facial attributes of the elderly population, such as muscle degradation and age-induced wrinkles. In the research by Dong et al. [

62], the Multi-Scale Attention Learning Network (MALN) uses multiple branches of Vision Transformers for FER, and it uses multi-scale attention to pick up on small details in expressions; our approach, however, uses SE blocks to adjust and improve important facial features that are specific to older people. This reinforces the efficiency of our lightweight model architecture for age-specific emotion classification. The present study demonstrates the applicability of SE blocks in elderly FER, where wrinkles and facial sagging complicate the recognition process. In another work, Jing Li et al. [

19] utilize traditional LBP features integrated with attention mechanisms in a CNN for FER. While both studies use attention mechanisms, our method advances by embedding SE blocks directly within MobileNet, offering a compact, trainable, and highly adaptive architecture specifically fine-tuned for elderly facial expressions. This makes it particularly well-suited for real-world embedded and assistive systems.

5. Conclusion

This paper proposes a novel transfer learning approach with an attention mechanism to enhance the learning process of facial expression representation in older adults. The fine-tuned MobileNet model achieves competitive results compared to baseline models for transfer learning, demonstrating improved feature extraction for FER, particularly on a middle-sized dataset of elderly facial expressions. By using depthwise separable convolutions along with an attention module and squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks, our tests greatly improved accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and how quickly the model learns. Furthermore, MobileNet+SE achieved a 3.21% reduction in latency compared to the baseline MobileNet model, highlighting that SE blocks enhance classification performance and contribute to slightly faster inference, making the model more suitable for real-time applications. Our method is proven to work well through t-SNE and Grad-CAM visualizations, which show that SE blocks help the model pay more attention to important facial areas related to expressions while reducing distractions from unimportant parts. A comparison with the best current methods shows that our approach is better, reaching an accuracy of 95.47% for six basic emotions on the FACE dataset. Additionally, MobileNet’s lightweight architecture combined with SE blocks ensures computational efficiency, making it practical for real-world applications. To further enhance our approach, we aim to collect a larger dataset to evaluate our method under real-world conditions, ensuring better generalization across diverse environments. We also plan to use the proposed model in smart devices to create an automatic emotion recognition system designed for older adults, which improves human-computer interactions in healthcare and assistive applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L.,S.E.,M.A., Y.Z., M.G., and O.B.; methodology, N.L.,S.E.,M.A., Y.Z., M.G., and O.B.; software, N.L.; validation S.E.,M.A., Y.Z., M.G., and O.B.; formal analysis, N.L.,S.E.,M.A., Y.Z., M.G., and O.B. ;investigation, N.L.,S.E.,M.A., Y.Z., M.G., and O.B.; data curation, N.L.; writing—original draft preparation,N.L.; writing—review and editing,S.E.,M.A., Y.Z., M.G., and O.B.; visualization, S.E.,M.A., Y.Z., M.G., and O.B.;supervision, S.E.,M.A., Y.Z., M.G., and O.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This project has been supported by the Moroccan Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research and Innovation, the Digital Development Agency (DDA) and the National Center for Scientific and Technical Research of Morocco (CNRST) through the ”Al-Khawarizmi project”, besides Kompai, Teamnet and MAScIR

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study comprises both publicly available and privately collected facial expression images. The publicly available portion of the data, the FACE database of facial expressions [

82], can be accessed at

https://faces.mpdl.mpg.de/imeji/. The private portion of the dataset was collected with informed consent under ethical approval granted by the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Center for Lifespan Psychology, Berlin, Germany. Due to privacy considerations, this dataset is not publicly available but may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with appropriate institutional approval.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Teamnet and Kompai Robotics for being our industrial partners in this project. We would also like to express our gratitude to the A-LAB (Analytics LAB) department at Mohamed VI Polytechnic University in Rabat, as the project leader and technical supervisors are part of this department. As a reminder, this publication is part of the work undertaken by different partners composed of MAScIR (Moroccan Foundation for Advanced Science, Innovation and Research), ENSIAS (Ecole Nationale Superieure d’Informatique et d’Analyse des Systemes), ENSAO (Ecole Nationale des Sciences Appliquees d’Oujda) and USPN (Universite de Sorbonne Paris Nord) within the framework of the ”Medical Assistant Robot” project. This project has been supported by the Moroccan Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research and Innovation, the Digital Development Agency (DDA) and the National Center for Scientific and Technical Research of Morocco (CNRST) through the ”Al-Khawarizmi project”, besides Kompai, Teamnet and MAScIR. (Research project code: Alkhawarizmi/2020/15)

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interes

References

- Wilmoth, J.R.; Bas, D.; Mukherjee, S.; Hanif, N.; et al. World social report 2023: Leaving no one behind in an ageing world; UN, 2023.

- Rogers, W.A.; Mitzner, T.L. Envisioning the future for older adults: Autonomy, health, well-being, and social connectedness with technology support. Futures 2017, 87, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jothimani, S.; Premalatha, K. THFN: Emotional health recognition of elderly people using a Two-Step Hybrid feature fusion network along with Monte-Carlo dropout. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 86, 105116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, F.; Raffe, W.; Garcia, J. Emotion recognition techniques for geriatric users: a snapshot. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 8th International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, O.; Araújo, L.; Figueiredo, D.; Paúl, C.; Teixeira, L. The caregiver support ratio in Europe: estimating the future of potentially (Un) available caregivers. In Proceedings of the Healthcare. MDPI, Vol. 10; 2021; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, G.L.; Kaas, M.J.; Hjartardottir, K.L. Psychotherapy with older adults. Psychotherapy for the Advanced Practice Psychiatric Nurse: A how-to Guide for Evidence-Based Practice 2022, pp. 823–865.

- Huang, W. Elderly Depression Recognition Based on Facial Micro-Expression Extraction. Traitement du Signal 2021, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaita, A.; Malnati, M.; Vaccaro, R.; Pezzati, R.; Marcionetti, J.; Vitali, S.; Colombo, M. Impaired facial emotion recognition and preserved reactivity to facial expressions in people with severe dementia. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics 2009, 49, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; Yang, E.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, W. A novel deep neural network-based emotion analysis system for automatic detection of mild cognitive impairment in the elderly. Neurocomputing 2022, 468, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, P.; Cohn, J.F.; Kanade, T.; Saragih, J.; Ambadar, Z.; Matthews, I. The extended cohn-kanade dataset (ck+): A complete dataset for action unit and emotion-specified expression. In Proceedings of the 2010 ieee computer society conference on computer vision and pattern recognition-workshops. IEEE; 2010; pp. 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M.J.; Kamachi, M.; Gyoba, J. Coding facial expressions with Gabor wavelets (IVC special issue). arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.05938 2020.

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Erhan, D.; Carrier, P.L.; Courville, A.; Mirza, M.; Hamner, B.; Cukierski, W.; Tang, Y.; Thaler, D.; Lee, D.H.; et al. Challenges in representation learning: A report on three machine learning contests. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing: 20th International Conference, ICONIP 2013, Daegu, Korea, 2013. Proceedings, Part III 20. Springer, 2013, November 3-7; pp. 117–124.

- Canal, F.Z.; Müller, T.R.; Matias, J.C.; Scotton, G.G.; de Sa Junior, A.R.; Pozzebon, E.; Sobieranski, A.C. A survey on facial emotion recognition techniques: A state-of-the-art literature review. Information Sciences 2022, 582, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revina, I.M.; Emmanuel, W.S. A survey on human face expression recognition techniques. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2021, 33, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.; Chenniappan, P.; Devaraj, S.; Madian, N. Facial expression recognition techniques: a comprehensive survey. IET Image Processing 2019, 13, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fölster, M.; Hess, U.; Werheid, K. Facial age affects emotional expression decoding. Frontiers in psychology 2014, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, A.; Liew, S.; Weinkle, S.; Garcia, J.K.; Silberberg, M.B. The facial aging process from the “inside out”. Aesthetic surgery journal 2021, 41, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Kim, K.; Bae, M.; Seo, M.G.; Nam, G.; Park, S.; Park, S.; Ihm, J.; Lee, J.Y. Changes in computer-analyzed facial expressions with age. Sensors 2021, 21, 4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jin, K.; Zhou, D.; Kubota, N.; Ju, Z. Attention mechanism-based CNN for facial expression recognition. Neurocomputing 2020, 411, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukavina, S.; Gruss, S.; Hoffmann, H.; Traue, H.C. Elderly People Benefit More from Positive Feedback Based on Their Reactions in the Form of Facial Expressions during Human-Computer Interaction. Psychology 2016, 7, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, H.; Mahoor, M.H.; Zandie, R.; Siewierski, J.; Qualls, S.H. Artificial emotional intelligence in socially assistive robots for older adults: a pilot study. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2022, 14, 2020–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Tran, D.T.; Lee, J.H. 3d facial pain expression for a care training assistant robot in an elderly care education environment. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2021, 8, 632015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 2014.

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.04861 2017.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 4700–4708.

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 1251–1258.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019, pp. 6105–6114.

- Gaya-Morey, F.X.; Buades-Rubio, J.M.; Palanque, P.; Lacuesta, R.; Manresa-Yee, C. Deep Learning-Based Facial Expression Recognition for the Elderly: A Systematic Review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.02618 2025.

- Labzour, N.; Fkihi, S.E.; Benaissa, S.; Zennayi, Y.; Bourja, O. A Survey on Facial Emotion Recognition for the Elderly. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Digital Technologies and Applications. Springer; 2023; pp. 561–575. [Google Scholar]

- Caroppo, A.; Leone, A.; Siciliano, P. Facial Expression Recognition in Older Adults using Deep Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the AI* AAL@ AI* IA; 2017; pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, N.; Silva, A.; Khanal, S.R.; Reis, A.; Barroso, J.; Filipe, V.; Sampaio, J. Facial emotion recognition in the elderly using a SVM classifier. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on Technology and Innovation in Sports, Health and Wellbeing (TISHW). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Algaraawi, N.; Morris, T. Study on aging effect on facial expression recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering, 2016, Vol. 1, pp. 465–70.

- Franklin, R.G.; Zebrowitz, L.A. Older adults’ trait impressions of faces are sensitive to subtle resemblance to emotions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 2013, 37, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. Strong evidence for universals in facial expressions: A reply to Russell’s mistaken critique. Psychological Bulletin 1994, 115, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, T.; Pietikäinen, M.; Mäenpää, T. Gray scale and rotation invariant texture classification with local binary patterns. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2000: 6th European Conference on Computer Vision Dublin, Ireland, June 26–July 1, 2000 Proceedings, Part I 6. Springer, 2000, pp. 404–420.

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE computer society conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR’05). Ieee, Vol. 1; 2005; pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, B.D.; Kanade, T. An iterative image registration technique with an application to stereo vision. In Proceedings of the IJCAI’81: 7th international joint conference on Artificial intelligence, Vol. 2; 1981; pp. 674–679. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N.; Li, Q.; Huan, R.; Liu, J.; Han, G. Deep spatial-temporal feature fusion for facial expression recognition in static images. Pattern Recognition Letters 2019, 119, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Jiang, D. HiT-MST: Dynamic facial expression recognition with hierarchical transformers and multi-scale spatiotemporal aggregation. Information Sciences 2023, p. 119301.

- Lu, Z.; Tang, X. Patch-Range Attention and Visual Transformer for Facial Expression Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Computer Technology (EIECT). IEEE, 2022, pp. 196–201.

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X. Deep multi-modality soft-decoding of very low bit-rate face videos. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2020, pp. 3947–3955.

- Islam, M.M.; Barua, P.; Rahman, M.; Ahammed, T.; Akter, L.; Uddin, J. Transfer learning architectures with fine-tuning for brain tumor classification using magnetic resonance imaging. Healthcare Analytics 2023, 4, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztel, I.; Yolcu, G.; Oz, C. Performance comparison of transfer learning and training from scratch approaches for deep facial expression recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wikanningrum, A.; Rachmadi, R.F.; Ogata, K. Improving lightweight convolutional neural network for facial expression recognition via transfer learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Computer Engineering, Network, and Intelligent Multimedia (CENIM). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–6.

- Hung, J.C.; Lin, K.C.; Lai, N.X. Recognizing learning emotion based on convolutional neural networks and transfer learning. Applied Soft Computing 2019, 84, 105724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Ngwe, J.; Lim, K.M.; Lee, C.P.; Ong, T.S.; Alqahtani, A. PAtt-Lite: lightweight patch and attention MobileNet for challenging facial expression recognition. IEEE Access 2024.

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Facial action coding system. Environmental Psychology & Nonverbal Behavior 1978.

- Indolia, S.; Nigam, S.; Singh, R. Integration of Transfer Learning and Self-Attention for Spontaneous Micro-Expression Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 Seventh International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Grid Computing (PDGC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 325–330.

- Marrero Fernandez, P.D.; Guerrero Pena, F.A.; Ren, T.; Cunha, A. Feratt: Facial expression recognition with attention net. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 2019, pp. 0–0.

- Xue, F.; Wang, Q.; Guo, G. Transfer: Learning relation-aware facial expression representations with transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 3601–3610.

- Pan, Y.; Shang, Y.; Liu, T.; Shao, Z.; Guo, G.; Ding, H.; Hu, Q. Spatial–temporal attention network for depression recognition from facial videos. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 237, 121410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Huang, P.; Liu, H.; Niu, S. Learning content-adaptive feature pooling for facial depression recognition in videos. Electronics Letters 2019, 55, 648–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hirota, K.; Dai, Y. Patch attention convolutional vision transformer for facial expression recognition with occlusion. Information Sciences 2023, 619, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Duan, Q. Hierarchical attention network with progressive feature fusion for facial expression recognition. Neural Networks 2024, 170, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; He, F.; Zhang, M. Real-time face expression recognition network based on attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Information Technology, Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (ICIBA). IEEE, 2023, Vol. 3, pp. 1064–1067.

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Wei, Q. Research and application of facial expression recognition based on attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Image Processing, Electronics and Computers (IPEC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 282–285.

- Meng, D.; Peng, X.; Wang, K.; Qiao, Y. Frame attention networks for facial expression recognition in videos. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2019, pp. 3866–3870.

- Sun, X.; Xia, P.; Ren, F. Multi-attention based deep neural network with hybrid features for dynamic sequential facial expression recognition. Neurocomputing 2021, 444, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Xu, L. Multiple attention network for facial expression recognition. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 7383–7393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D. Facial expression recognition in the wild using multi-level features and attention mechanisms. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2020, 14, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Ren, W.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, W.; Liu, H. Multi-scale attention learning network for facial expression recognition. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2023, 30, 1732–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Huang, X.; Taini, M.; Li, S.Z.; PietikäInen, M. Facial expression recognition from near-infrared videos. Image and vision computing 2011, 29, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Deng, W.; Du, J. Reliable crowdsourcing and deep locality-preserving learning for expression recognition in the wild. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 2852–2861.

- Mollahosseini, A.; Hasani, B.; Mahoor, M.H. Affectnet: A database for facial expression, valence, and arousal computing in the wild. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2017, 10, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Deng, W. Deep facial expression recognition: A survey. IEEE transactions on affective computing 2020, 13, 1195–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Zhu, Z.; Dai, Y.; Wang, B.; Wu, X. Facial expression recognition based on deep learning. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2022, 215, 106621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, T.; Xia, Y.; Yan, Q.; Xun, L. Facial expression recognition with faster R-CNN. Procedia Computer Science 2017, 107, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shi, X.; Zhang, S. Facial expression recognition via deep learning. IETE technical review 2015, 32, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Huang, C.; Wang, X.; Jiang, F. Facial expression recognition with grid-wise attention and visual transformer. Information Sciences 2021, 580, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, J.; Shan, S.; Chen, X. Occlusion aware facial expression recognition using CNN with attention mechanism. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2018, 28, 2439–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Cui, J. Recognition of teachers’ facial expression intensity based on convolutional neural network and attention mechanism. IEEE access 2020, 8, 226437–226444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, A.R.; Yan, H. SqueezExpNet: Dual-stage convolutional neural network for accurate facial expression recognition with attention mechanism. Knowledge-Based Systems 2023, 269, 110451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on knowledge and data engineering 2009, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Too, E.C.; Yujian, L.; Njuki, S.; Yingchun, L. A comparative study of fine-tuning deep learning models for plant disease identification. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 161, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Duan, Y.; Gu, Y. A comparison review of transfer learning and self-supervised learning: Definitions, applications, advantages and limitations. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, p. 122807.

- Stančić, A.; Vyroubal, V.; Slijepčević, V. Classification efficiency of pre-trained deep CNN models on camera trap images. Journal of Imaging 2022, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. International journal of computer vision 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshalali, T.; Josyula, D. Fine-tuning of pre-trained deep learning models with extreme learning machine. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI). IEEE, 2018, pp. 469–473.

- Li, B.; Lima, D. Facial expression recognition via ResNet-50. International Journal of Cognitive Computing in Engineering 2021, 2, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. Facial expression recognition by DenseNet-121. In Multi-Chaos, Fractal and Multi-Fractional Artificial Intelligence of Different Complex Systems; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 263–276.

- Ebner, N.C.; Riediger, M.; Lindenberger, U. FACES—A database of facial expressions in young, middle-aged, and older women and men: Development and validation. Behavior research methods 2010, 42, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandini, M.; Bagli, E.; Visani, G. Metrics for multi-class classification: an overview. arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.05756 2020.

- Ruder, S. An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.04747 2016.

- Tseng, F.H.; Yeh, K.H.; Kao, F.Y.; Chen, C.Y. MiniNet: Dense squeeze with depthwise separable convolutions for image classification in resource-constrained autonomous systems. ISA transactions 2023, 132, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreevidya, P.; Veni, S.; Ramana Murthy, O. Elder emotion classification through multimodal fusion of intermediate layers and cross-modal transfer learning. Signal, image and video processing 2022, 16, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; Feng, Z.; Yang, X.; Tian, J. Real-time multimodal emotion recognition system based on elderly accompanying robot. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, 2020, Vol. 1453, p. 012093.

Figure 1.

Wrinkles and facial expression features resemblance. AU: action units; AU06: Cheek Raiser and Lid Compressor; AU10: Upper Lip Raiser; AU04: Brow Lowerer; AU15: Lip Corner Depressor; AU12: Lip Corner Puller.

Figure 1.

Wrinkles and facial expression features resemblance. AU: action units; AU06: Cheek Raiser and Lid Compressor; AU10: Upper Lip Raiser; AU04: Brow Lowerer; AU15: Lip Corner Depressor; AU12: Lip Corner Puller.

Figure 2.

Workflow of the Proposed Facial Expression Recognition Method.

Figure 2.

Workflow of the Proposed Facial Expression Recognition Method.

Figure 3.

The original architecture of transfer learning models

Figure 3.

The original architecture of transfer learning models

Figure 4.

A Squeeze-and-Excitation Block.

Figure 4.

A Squeeze-and-Excitation Block.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the integration of the SE blocks into the last layers of the MobileNet architecture.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the integration of the SE blocks into the last layers of the MobileNet architecture.

Figure 6.

MobileNet architecture with a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block.

Figure 6.

MobileNet architecture with a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block.

Figure 7.

Samples from the FACE database.

Figure 7.

Samples from the FACE database.

Figure 8.

Loss and accuracy curves of all models using the total fine-tuning method. Panels are described as: (a) MobileNet, (b) DenseNet121, (c) VGG16, (d) ResNet50, (e) Xception, (f) EfficientNetB0.

Figure 8.

Loss and accuracy curves of all models using the total fine-tuning method. Panels are described as: (a) MobileNet, (b) DenseNet121, (c) VGG16, (d) ResNet50, (e) Xception, (f) EfficientNetB0.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrices of all models using the total fine-tuning method. Panels are described as: (a) MobileNet, (b) DenseNet, (c) VGG16, (d) ResNet50, (e) Xception, (f) EfficientNetB0.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrices of all models using the total fine-tuning method. Panels are described as: (a) MobileNet, (b) DenseNet, (c) VGG16, (d) ResNet50, (e) Xception, (f) EfficientNetB0.

Figure 10.

Layer-wise analysis: Visualization comparison for MobileNet and MobileNet+SE on the FACE database.

Figure 10.

Layer-wise analysis: Visualization comparison for MobileNet and MobileNet+SE on the FACE database.

Figure 11.

Expression-wise analysis: Grad-CAM comparison across multiple expressions.

Figure 11.

Expression-wise analysis: Grad-CAM comparison across multiple expressions.

Figure 12.

t-SNE feature visualization.

Figure 12.

t-SNE feature visualization.

Table 1.

Image classification pre-trained models and their properties.

Table 1.

Image classification pre-trained models and their properties.

| Model |

Size (MB) |

Top-1 Acc. (%) |

Params |

Depth |

Time (ms) |

| Inception |

215 |

80.3 |

55.9M |

449 |

10.0 |

| InceptionV3 |

92 |

77.9 |

23.9M |

189 |

6.9 |

| MobileNet |

16 |

70.4 |

4.3M |

55 |

3.4 |

| MobileNetV2 |

14 |

71.3 |

3.5M |

105 |

3.8 |

| DenseNet121 |

33 |

75.0 |

8.1M |

242 |

5.4 |

| DenseNet169 |

57 |

76.2 |

14.3M |

338 |

6.3 |

| DenseNet201 |

80 |

77.3 |

20.2M |

402 |

6.7 |

| VGG16 |

528 |

71.3 |

138.4M |

16 |

4.2 |

| VGG19 |

549 |

71.3 |

143.7M |

19 |

4.4 |

| ResNet50 |

98 |

74.9 |

25.6M |

107 |

4.6 |

| ResNet50V2 |

98 |

76.0 |

25.6M |

103 |

4.4 |

| ResNet101 |

171 |

76.4 |

44.7M |

209 |

5.2 |

| NASNetMobile |

23 |

74.4 |

5.3M |

389 |

6.7 |

| NASNetLarge |

343 |

82.5 |

88.9M |

533 |

20.0 |

| EfficientNet-B3 |

47 |

81.6 |

12.0M |

114 |

4–5 |

| EfficientNet-B0 |

29 |

77.1 |

5.3M |

82 |

1–2 |

Table 2.

Dataset statistics and demographic characteristics of elderly subjects

Table 2.

Dataset statistics and demographic characteristics of elderly subjects

| Characteristics |

Older Adults (n=57) |

Number of Images per Emotion |

| |

|

N |

H |

D |

A |

S |

F |

| Age, mean (SD) |

73.2 (2.8) |

114 |

114 |

114 |

114 |

114 |

114 |

| Sex, n (%) |

F: 29 (50.88%)

M: 28 (49.12%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

Hyperparameter configuration for training

Table 3.

Hyperparameter configuration for training

| Parameters |

Setting |

| Batch size |

32 |

| Optimizer |

SGD |

| Epochs |

100 |

| Learning rate |

0.0005 |

| Criterion |

Categorical cross entropy |

| Momentum |

0.9 |

| Dropout rate |

0.1 |

| Regularization |

L2 = 0.03 |

Table 4.

Parameters of transfer learning models

Table 4.

Parameters of transfer learning models

| Models |

Size (MB) |

Top-1 Accuracy |

Parameters |

Depth |

| MobileNet |

16 |

70.04% |

4.3M |

55 |

| VGG16 |

528 |

71.3% |

138.4M |

16 |

| ResNet50 |

98 |

74.9% |

25.6M |

107 |

| DenseNet121 |

33 |

75.0% |

8.1M |

77.1 |

| EfficientNetB0 |

29 |

81.6% |

5.3M |

82 |

| Xception |

88 |

79.0% |

22.9M |

71 |

Table 5.

Average accuracy with 5-fold cross-validation for all transfer learning models