1. Introduction

With the United Nations’ Agenda 2030, the European (EU) Green Deal [

1], legal frameworks [

2] and action plans [

3] derived from it, countries around the world have set themselves seventeen ambitious global sustainable development goals. These are intended to secure social prosperity and peace globally and enable healthy economic growth for all, despite the challenges posed by the climate crisis. In this context, the economy and the manufacturing industry are assigned considerable responsibility for overcoming these challenges. Against this backdrop, lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling constitutes a strategically important locus where circular-economy ambitions encounter implementation realities. Beyond technical efficacy, progress depends on how organizations mobilize resources, align institutional routines, and build internal legitimacy for change. Our study speaks to these practical conditions by eliciting stakeholder priorities and perceived constraints.

Recycling and waste management play a central role in this. They are the link between production, consumption, and the return of raw materials. This means that they not only contribute to the conservation of primary resources and the reduction of emissions through proper disposal and recycling but are also an important economic sector. However, simply implementing the right measures, such as recycling or the production of secondary raw materials, is not enough. It is equally crucial to implement these measures efficiently and in an environmentally friendly manner to achieve sustainability goals and a circular economy. Without a comprehensive environmental management system that monitors consistent compliance with environmental standards and continuously reduces emissions and pollutants, these processes threaten to counteract their original purpose - environmental protection.

In addition to social and environmental challenges, recycling and waste management companies face the same economic challenges as any other business and are therefore caught between their social mission and entrepreneurial thinking. Sustainability in waste management therefore means not only doing the right things but also doing them right. Effective environmental and sustainability management are the keys to combining ecological, social, and economic goals. Only through a combination of technical innovations, stringent monitoring and responsible action can recycling and waste management processes contribute to solving global environmental problems.

The same applies to the field of LIB production and their recycling. As production scales up, sustainability management and responsible recycling become essential to fulfil the dual function of returning critical raw materials to the cycle and reducing environmental impact. Life cycle assessments (LCA) have highlighted the potential of LIB recycling to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, energy use, and water consumption by more than 50% compared to primary extraction, with key sensitivities related to electricity mix and chemical input [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Technological research in this field has advanced rapidly, with numerous studies analyzing and comparing different recycling methods, as well as emerging options [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. While the performance potential of LIB recycling is increasingly well documented, less is known about the organizational and institutional conditions that determine whether such potential is realized in practice. We address this gap using stakeholder-based mapping to diagnose where implementation stalls.

Despite this growing body of technical and environmental research, stakeholder perspectives remain underrepresented when talking about sustainable recycling strategies, even though implementation depends on coordinated action across the value chain from manufacturers to policymakers. Academic work in this field often takes a top-down regulatory focus, yet sustainability transitions require active stakeholder agency. Recent studies begin to address this by analyzing stakeholder-specific sustainability trade-offs [

13], social impacts along the supply chain [

5], or collaborative circularity strategies [

14]. Still, systematic mappings of recycler-informed barriers and interventions are rare. This study fills that gap. Based on systematic research into the advantages of sustainable economic management of companies compared to neglecting it, as well as a survey of possible company-related internal barriers and drivers, a stakeholder-related survey is conducted. The results are a weighted list of risks and opportunities associated with sustainability in companies presented in the form of a risk-opportunity mapping, as well as a priority-weighted barrier-intervention mapping derived by the same stakeholders, which culminates in clear recommendations for sustainable action for participants from the industry. The resulting roadmap links key challenges to countermeasures across strategic, operational, and institutional levels, supporting implementation. The method and roadmap are not only valid for stakeholders in the LIB recycling sector but can also be used as a blueprint for other industries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

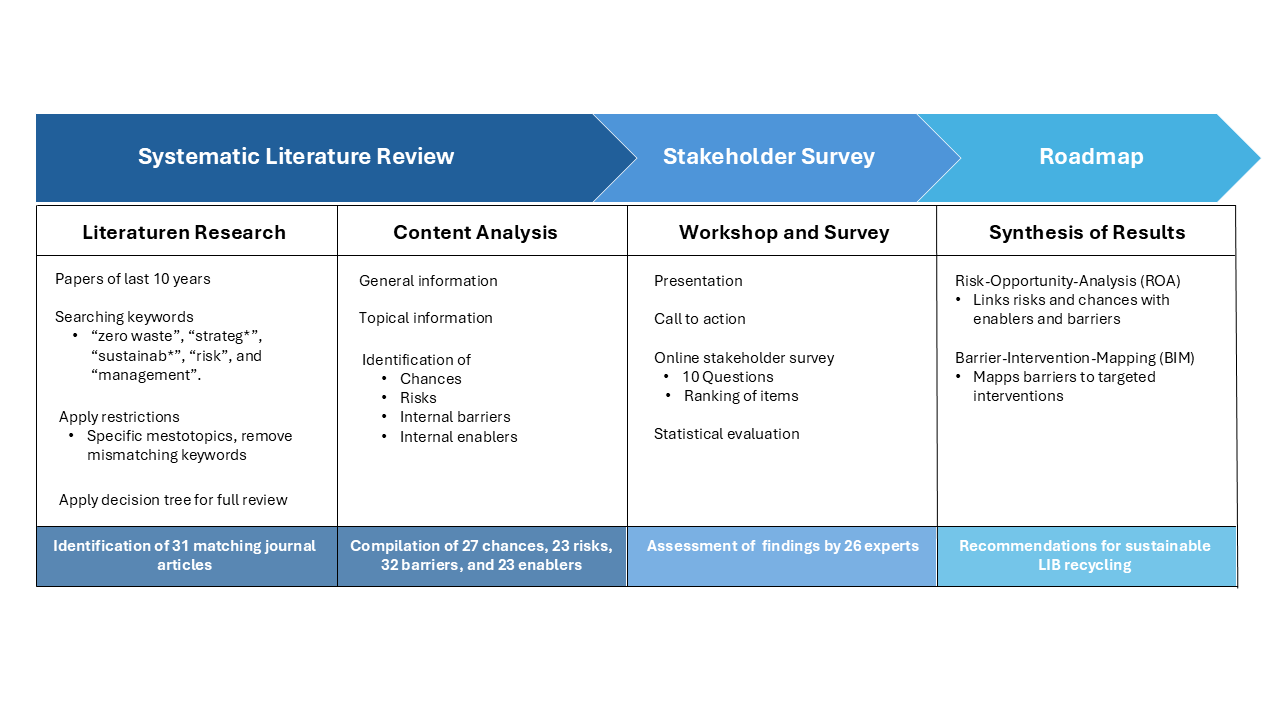

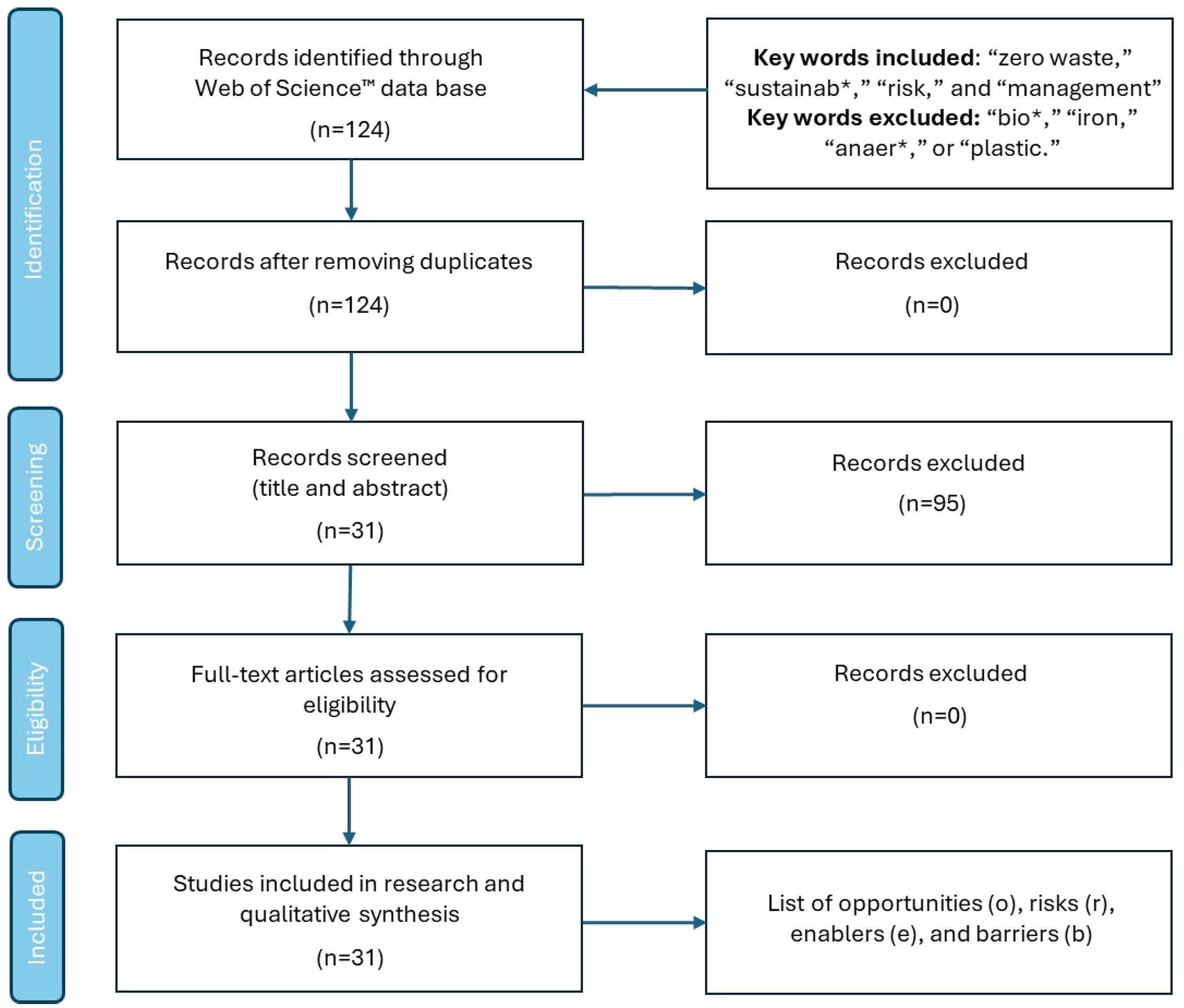

2.1.1. Systematic Literature Review

A structured literature review, see

Figure 1, was conducted to provide an item list of four relevant dimensions: company-related inside-out opportunities (o), risks (r), enablers (e) and barriers (b) of sustainable strategies. All items were coded by frequency and thematic relevance. Every risk and opportunity are categorized into one of the three sustainability dimensions (economical, ecological, environmental). Barriers and enabler items are sub-grouped into the five domains: strategic, operational, cultural, institutional, and technical-relevant item. This enables reading the results not only as content lists but as proxies for organizational capability and governance attention. Results partially build on earlier work by Rutrecht et al. 2023 [

15]. The resulting lists of items form the basis for stakeholder evaluation and both mapping approaches.

2.1.2. Stakeholder Survey

To contextualize the literature-based finding, a stakeholder survey was conducted, featuring a structured online questionnaire during a study-related project workshop. Overall, the survey engaged 26 participants from industry (n=9) academia (n=16) and regulatory institutions (n=1), of which 21 took part at the workshop, 5 during a conference setting, at the Sardinia Symposium 2023. All participants had technical-scientific backgrounds and held mid- to senior-level management roles in battery production, recycling, or circular economy. The group was balanced in terms of age (25–54+) and gender (46% female, 54% male).

The questionnaire applies a funnel structure, progressing from general to specific assessments. In total, ten questions examine the stakeholder perspective of the four relevant dimensions in this study: opportunities, risks, barriers, and enablers. Opportunities were assessed by ranking perceived positive sustainability impact (high, low) and implementation effort (high, low). Risks are evaluated on a four-tier criticality scale (low, moderate, high, critical) supported by a graphical matrix. Barriers and enablers are rated using five-point ordinal scales (very low to very high).

Stakeholders were also asked to select the top five most relevant opportunities, risks, barriers, and enablers in their own institutional settings to check for consistency in answering behaviour. These rankings are used as well to surface practical salience and to triangulate aggregated scores with decision-facing priorities in organizations. To reduce selection bias, the list of answers is randomly ordered for each participant.

To verify construct validity, Likert scales (strongly agree–strongly disagree) were applied, and internal consistency of the scales was evaluated using Cronbach’s Alpha [

16]. A pre-test of the questionnaire was conducted to ensure clarity and resulted in an average completion time of 10 minutes. The full questionnaire is available in the supplementary material.

2.2. Synthesis

Risk-opportunity mapping and barrier-intervention mapping are used to synthesize literature results and stakeholder insights of the survey.

2.2.1. Risk-Opportunity Mapping

The qualitative assessment of each risk item by a respondent is translated to a four-tier ordinal scale: low =1, moderate=2, high=3, and critical=4. The individual scores are aggregated to calculate an overall criticality index (c), which categorizes risks as follows: critical (c>50), high (45–49), moderate (40–44), or low (<40). The intervals from low to critical are deliberately chosen to distinguish between degrees of urgency. Opportunities are evaluated using a two-dimensional matrix with perceived impact (high/low) and implementation effort (high/low) as axes, yielding into four categories: low-hanging fruits (high impact, low effort), strategic leaps (high impact, high effort), incremental improvements (low impact, low effort), and money pits (low impact, high effort). Post-hoc classification of risk origin (inside-out, outside-in, dual) is used solely to interpret stakeholder ratings through the lens of double materiality in current reporting practice, not as a formal theory test.

2.2.2. Barrier-Intervention Mapping

Barrier-intervention mapping is applied to structure internal implementation constraints and derive targeted mitigation strategies. Barriers and enablers are rated on a five-point ordinal scale:0=none, 1=minor, ..., 4=very high. For each item, stakeholder responses are aggregated to calculate a weighted score representing the average disabling or enabling effect of each item. Based on these cumulative scores, barriers are grouped as very high (sb>50), high (sb=45-50), moderate (sb=40-44), low (sb=36-40), or very low (sb<36). Following the same logic, enablers are grouped: very high (se>66), high (se=61-65), moderate (se=56-60), low (se=51-55), and very low (se<50). The choice of thresholds for each group was made deliberately by the authors to support meaningful discussion across distinct levels of perceived hindrance or support.

Then, a barrier–intervention heatmap is developed by applying the following scoring logic. Every and each enabler–barrier pair is assessed and assigned with a basic score of the expected positive effect by the authors ranging from: 2 = strong positive effect, 1 = tentative positive effect, and 0 = no expected effect. Then, the qualitative score is multiplied by the stakeholder-derived weight of the aggregated enabling score sb and se reflecting the degree of the perceived enabling and hindering effect of the item. To keep the numbers small, the scores sb and se are translated to a five-tier ordinal scale (low=1 to critical=5). According to this calculation, scores always range between 0 and 50, with 50 representing the maximum value and the highest priority. The combined results yield a priority-ranked barrier-intervention heatmap, incorporating both weighted scores of perceived relevance and estimated leverage. Because the basic score (0, 1, 2) reflects authorial judgment, we document the scoring scheme and carry this interpretive choice forward into the limitations of the method to maintain transparency. Equation 1 gives a scoring example for assessing the positive effect of any “enabler” item on every “barrier”-item.

2.2.3. Roadmap

Finally, a mixed-method approach is applied to formulate a roadmap, to translate stakeholder insights into actionable strategies towards sustainable business practices. Interventions are developed by triangulating: (a) literature results, (b) expert input from the stakeholder survey, and (c) authorial synthesis including an indicative timeline (short- to long-term).

3. Results

3.1. Literature Results

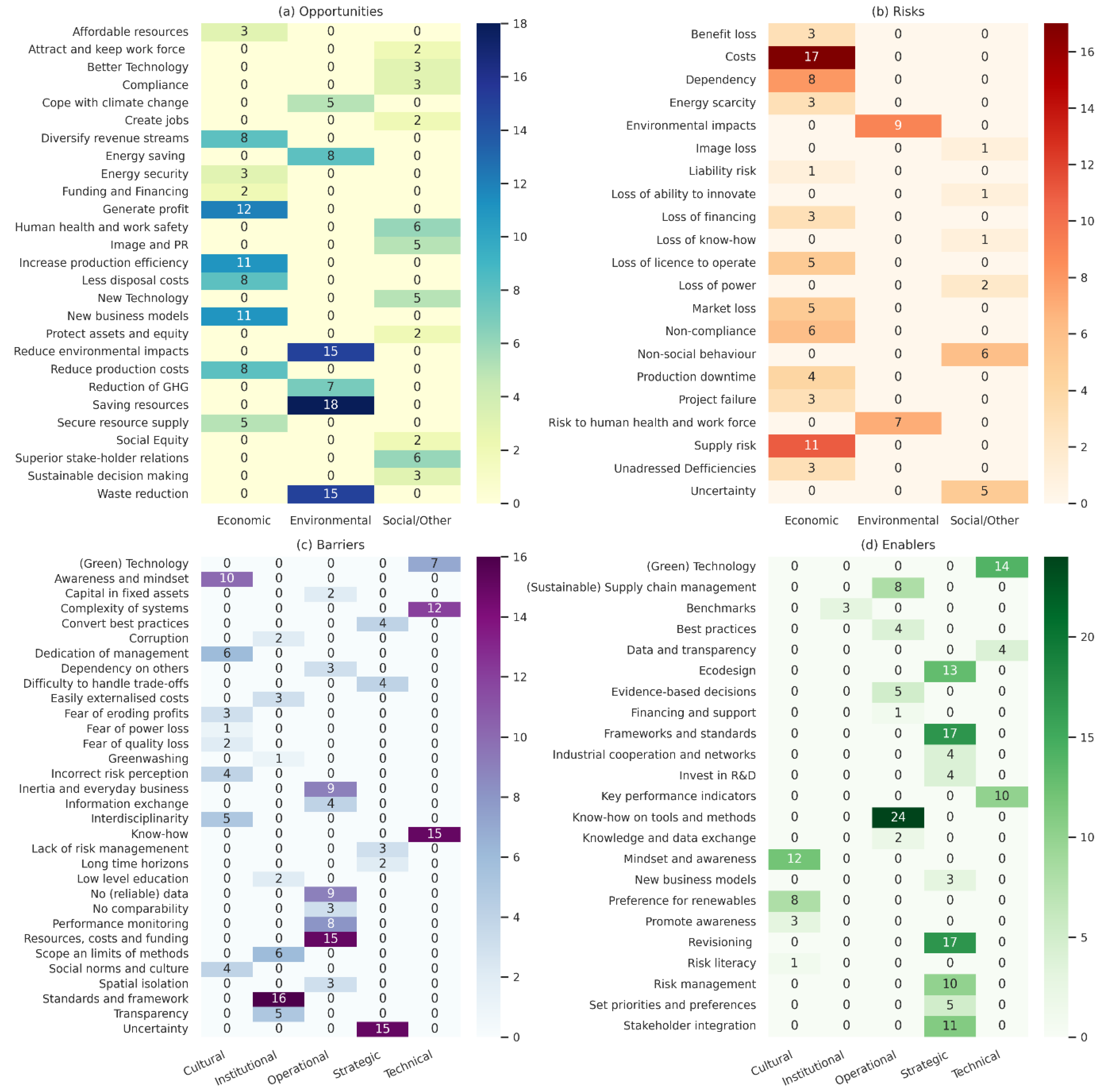

The structured literature review yields 27 opportunities, 21 risks, 32 internal barriers, and 23 enablers (

Figure 2). Opportunities are most frequently linked to economic (41.8%) and environmental (38.1%) benefits, whereas risks are predominantly framed in economic terms (66.2%), with social (21.8%) and environmental (12.0%) aspects discussed less often. Below, we synthesize key thematic clusters per category and illustrate the main mechanisms emphasized across literature.

The thorough results including source indexing are provided in supplementary material S1.

3.1.1. Chances of Embracing Sustainability

Across studies, three clusters dominate opportunities linked to sustainability (

Figure 2 (a)). First,

environmental efficiency is consistently highlighted by realizing resource savings (cited in 18 sources), waste reduction (15), and reduced environmental impacts (15). Second,

economic performance and business resilience appears as a core theme, including profit generation (12), new business models (11), and increased production efficiency (11). Third,

technological innovation features through adoption of new or better technologies (5 and 3, respectively) and lower disposal-related costs (8). Social and governance-related opportunities, such as social equity (2), job creation (2), and sustainable decision-making (3), are discussed far less frequently.

Mechanistically, the literature describes several pathways through which firms realize given opportunities. Productivity and efficiency gains are implemented via more efficient technologies, minimized resource and energy consumption, reduced waste generation, and avoided levies or taxes associated with emissions and disposal; improvements in occupational safety can further diminish downtime and indirect costs. New or diversified revenue streams are realized through product take-back and repair, rental or service-based models, and industrial symbiosis that monetizes by-products as secondary inputs. Enhanced resilience against market and supply volatility is strengthened through energy and resource security strategies, portfolio diversification, and workforce attraction/retention supported by improved working conditions.

Literature provides a rich background highlighting chances of sustainability. The following studies give a broad overview [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

3.1.2. Risks of Abandoning Sustainability

Companies that fail to exploit the potential of sustainability may enjoy short-term profits, for example through externalized environmental costs (source: externalized costs) but in the medium to long term perspective they will face serious challenges (

Figure 2,

(b)). Three clusters structure the literature-derived risk landscape. The first is

operational and financial fragility, including increasing costs (17 sources), supply chain failure (11), and dependency on critical inputs (8). The second

concerns regulatory and institutional uncertainty, with non-compliance (6), general policy uncertainty (5), and loss of license to operate (5). The third encompasses

environmental and social risks, most commonly environmental impacts (9), risks to human health and workforce (7), and non-social or irresponsible behaviour (6). Downstream financial consequences such as loss of financing and project failure (each 3) are repeatedly described as outcomes of internal and external misalignments.

The literature details several reinforcing mechanisms, of which four stand out in particular: First, profit erosion through inefficiencies (high material and energy intensity), elevated waste and emissions, and associated taxes/levies; reputational damage can further depress sales and pricing power. Second, threats to company value via unplanned downtime, asset under-maintenance, and workplace accidents or illnesses; coupled with reputational loss, these dynamics impair recruitment and retention. Thirdly, loss of competitiveness when firms fail to meet evolving standards, procurement requirements, or financing criteria, and when the outflow of skilled personnel undermines innovation capacity. And finally, legal exposure via liability for environmental or health damages and, in the extreme, loss of the license to operate.

A double-materiality logic is implicit in many accounts: inside-out risks (e.g., emissions, safety lapses, knowledge attrition) can trigger outside-in pressures (e.g., sanctions, financing constraints, market backlash). This coupling reinforces the need for integrated risk management that spans operational performance, regulatory compliance, and social legitimacy. Selected key studies [

15,

17,

18,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] provide a good overview on the subject.

3.1.3. Organizational Levers and Constraints

The literature exhibits an asymmetry: enablers are broadly catalogued, yet granular discussion of how they overcome specific barriers is rarer. Most frequently cited enablers (

Figure 2, (d)) include know-how on tools and methods (18 publications), data and knowledge exchange (17), frameworks and standards (17), and industry-wide collaboration and networks (14). These are followed by (green) technology (14), process transparency (13), financing and resources (10), and research and development (R&D) investment (10). Cultural enablers, stakeholder integration (12) and management mindset (11), appear less frequently but feature prominently in conceptual debates on implementation.

On the barrier side, the most frequently discussed obstacles (

Figure 2,

(c)) are lack of reliable data (16), resource and funding constraints (15), and system complexity (12). Additional barriers include limited methodological scope (9), organizational inertia (9), and insufficient risk management structures (6). Soft barriers (e.g., social norms, limited management dedication) are less visible in counts but may carry outsized practical influence.

Across literature, four cross-cutting mechanisms recur. They revolve around data deficits, funding constraints, perception of complexity and know-how gaps. First, when it comes to data deficits, manual collection, inconsistent metrics, and poor traceability come into play. They undermine the credibility and usefulness of management in general, and sustainability tools in particular. Secondly, funding constraints, which is especially salient for small to medium enterprises, limit investment in digital infrastructure, training, and R&D, slowing or even inhibiting capability buildup. Thirdly, the perceived and actual complexity of the subject, handling the multitude of tools, standards, while addressing sometimes conflicting needs of stakeholders, creates cognitive overload and decision paralysis when sustainability is treated as an add-on rather than embedded practice. And last but not least, know-how gaps ranging from meaningful tool selection to result interpretation diminish internal legitimacy and can lead to misapplication or superficial compliance. The enabler set corresponds to these deficits: standards and data governance respond to information gaps; collaboration and networks address fragmentation; research and development of green technologies target technical bottlenecks; and training and leadership commitment build absorptive capacity. Yet the literature provides fewer concrete pairings of enablers to specific barrier constellations, an evidence gap that the stakeholder-derived barrier–intervention mapping in

Section 3.4.2 begins to close. Key publications in this area are: [

15,

17,

18,

21,

22]. Broader contextual insights are provided by [

25,

26,

27]. Additional institutional and cross-sectoral perspectives are offered by [

16,

28].

3.2. Stakeholder Survey

The specific responses of the stakeholders to the survey can be found in the supplementary material S2.

3.3. Risk-Opportunity Mapping

Evaluation of the answers of the stakeholder survey reveals the following insights.

3.3.1. Validated Opportunities

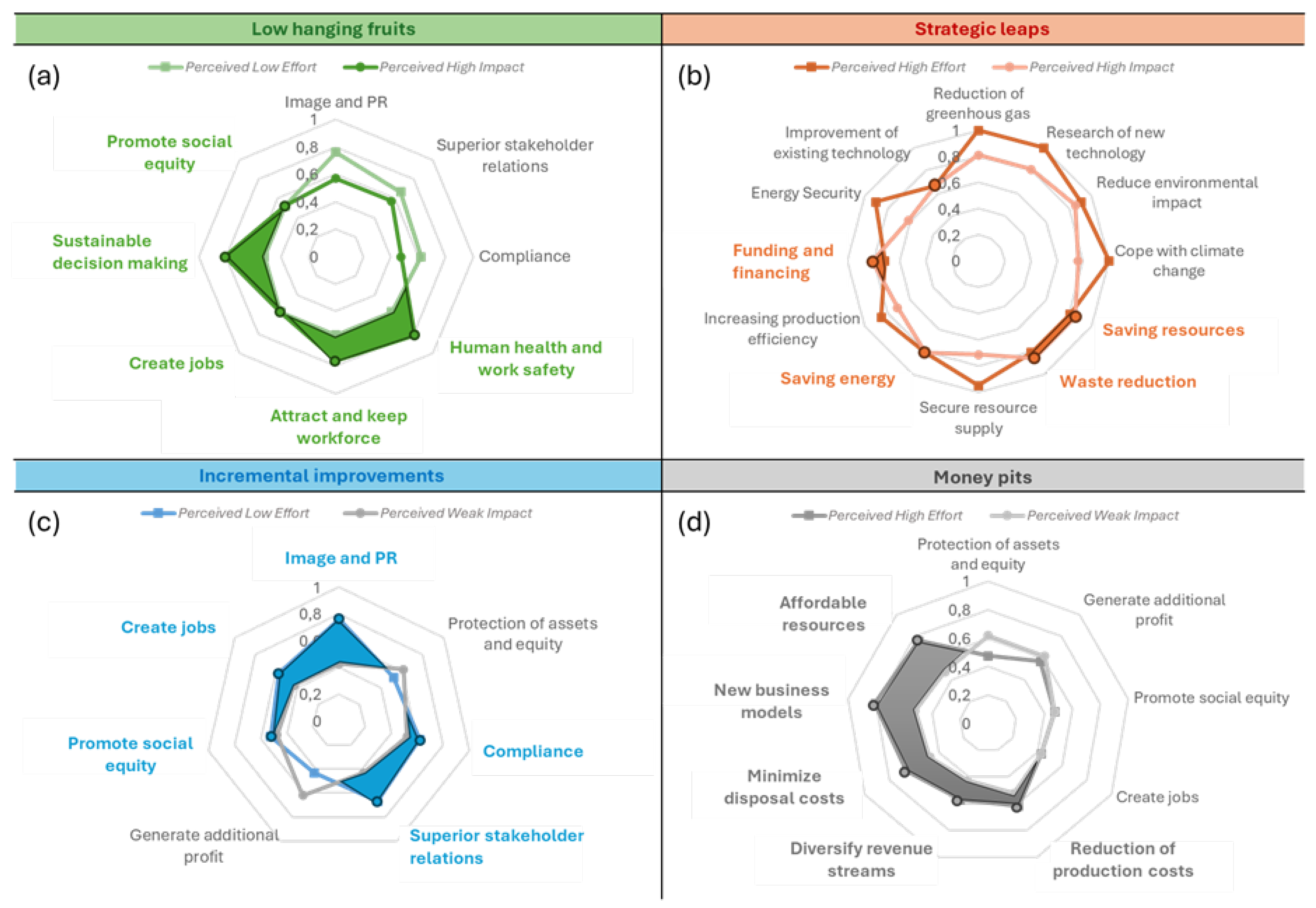

According to the method, four distinct categories are derived (

Figure 3). Incremental improvements (

Figure 3, (c)) reflect opportunities like social equity, job creation, and basic PR measures. Although recognized, these were not rated as transformative opportunities. Low hanging fruits (

Figure 3,

(a)) include domains such as the implementation of human health and work safety, attract and keep workforce, create jobs, sustainable decision-making and promote social equity.

Despite being linked with low effort, image and PR, superior stakeholder relations and compliance are seen as less impactful. Items categorized as strategic leaps (

Figure 3,

(b)) are perceived by stakeholders as core levers for transformative change, albeit requiring substantial resources. In particular, greenhouse gas reduction is unanimously considered to demand significant effort; nonetheless, measures in this domain are attributed the highest effectiveness. The same applies to the research and development of new technologies, the mitigation of negative environmental impacts, the safeguarding of resource supply, and climate change adaptation. Certain entries, such as resource conservation, waste reduction, saving energy, funding and resource provision, and the experimental advancement of existing technologies, stand out as particularly attractive. For these items, stakeholders anticipate considerably higher benefits than the associated implementation efforts would suggest. Other items are assessed as money pits (

Figure 3,

(d)), where the effort is expected to be high and linked to perceived weak impact. For instance, procurement of affordable resources, new business models and minimizing disposal costs received moderate attention but were deprioritized due to poor perceived returns relative to effort.

The top five opportunities selected by stakeholders as most feasible within their own institutional context were: research of new technologies, workforce attraction and retention, improvement of existing technologies, waste reduction, and greenhouse gas reduction. A Cronbach’s Alpha of α = 0.992 confirmed the high internal consistency of the literature-derived list of opportunity items.

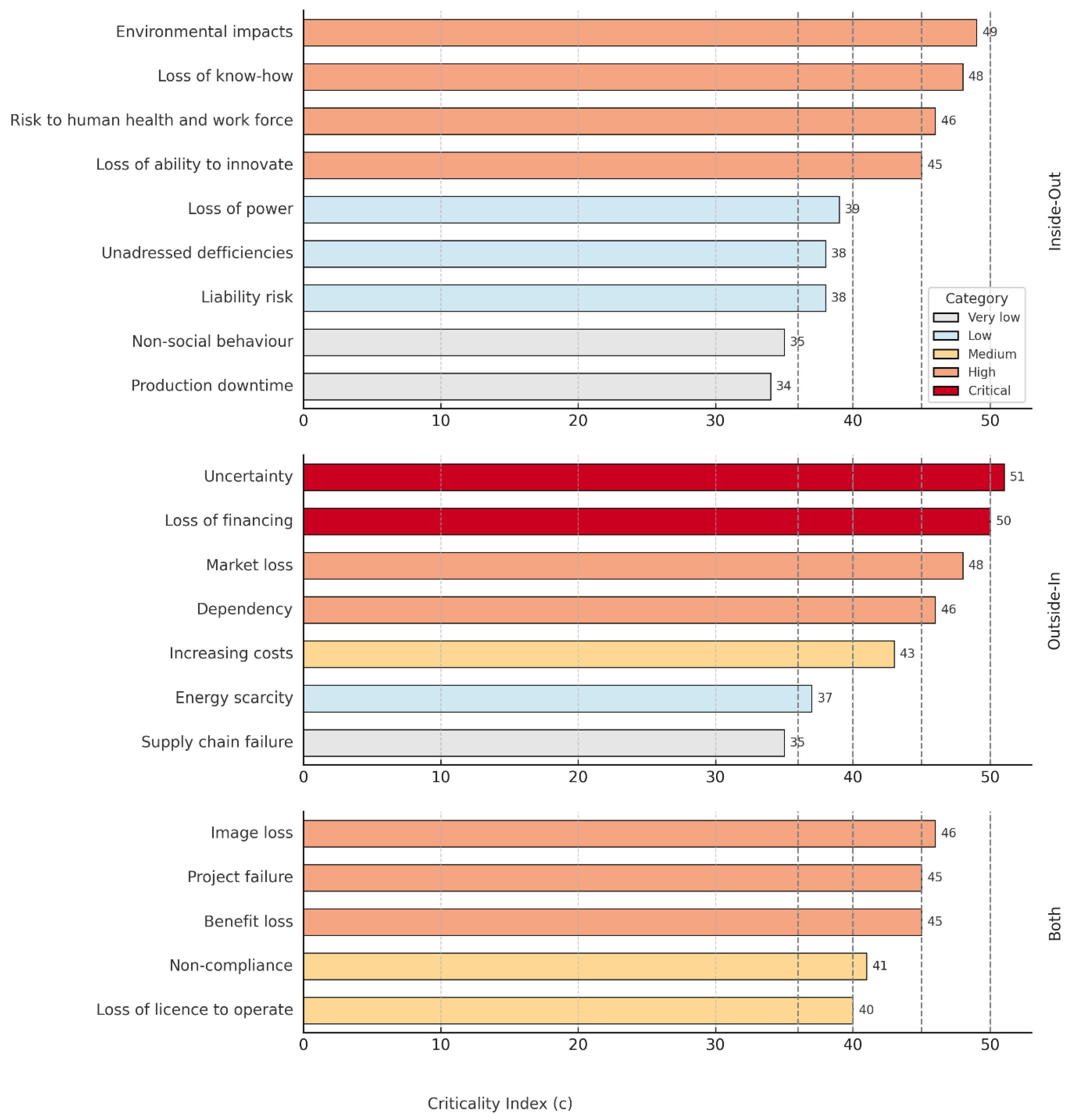

3.3.2. Consolidated Risk Landscape

Figure 4 gives an overview of the results of the risk assessment by the stakeholders, displaying a ranked order by the aggregated criticality index c. The highest-rated risk is regulatory uncertainty (c = 51), followed by loss of financing (c = 50) and environmental impacts (c = 49). Other high-risk items include market loss and loss of know-how (each c = 48), image loss, dependency, and health and workforce risks (c = 46), as well as project failure, benefit loss, and loss of innovation capacity (c = 45). In contrast, risks such as production downtime, non-social behaviour, supply chain failure, and liability risk were rated with lower criticality (c < 40), suggesting they are considered more manageable under current conditions.

The stakeholder-specific prioritizations closely mirror the scoring results. The top-five items are in a top-down order loss of financing, loss of know-how, project failure, loss of ability to innovate and image loss.

A Cronbach’s Alpha of α = 0.990 confirms the robustness and internal consistency of the risk construct.

3.4. Barrier-Intervention Mapping

3.4.1. Barrier and Enabler Assessment

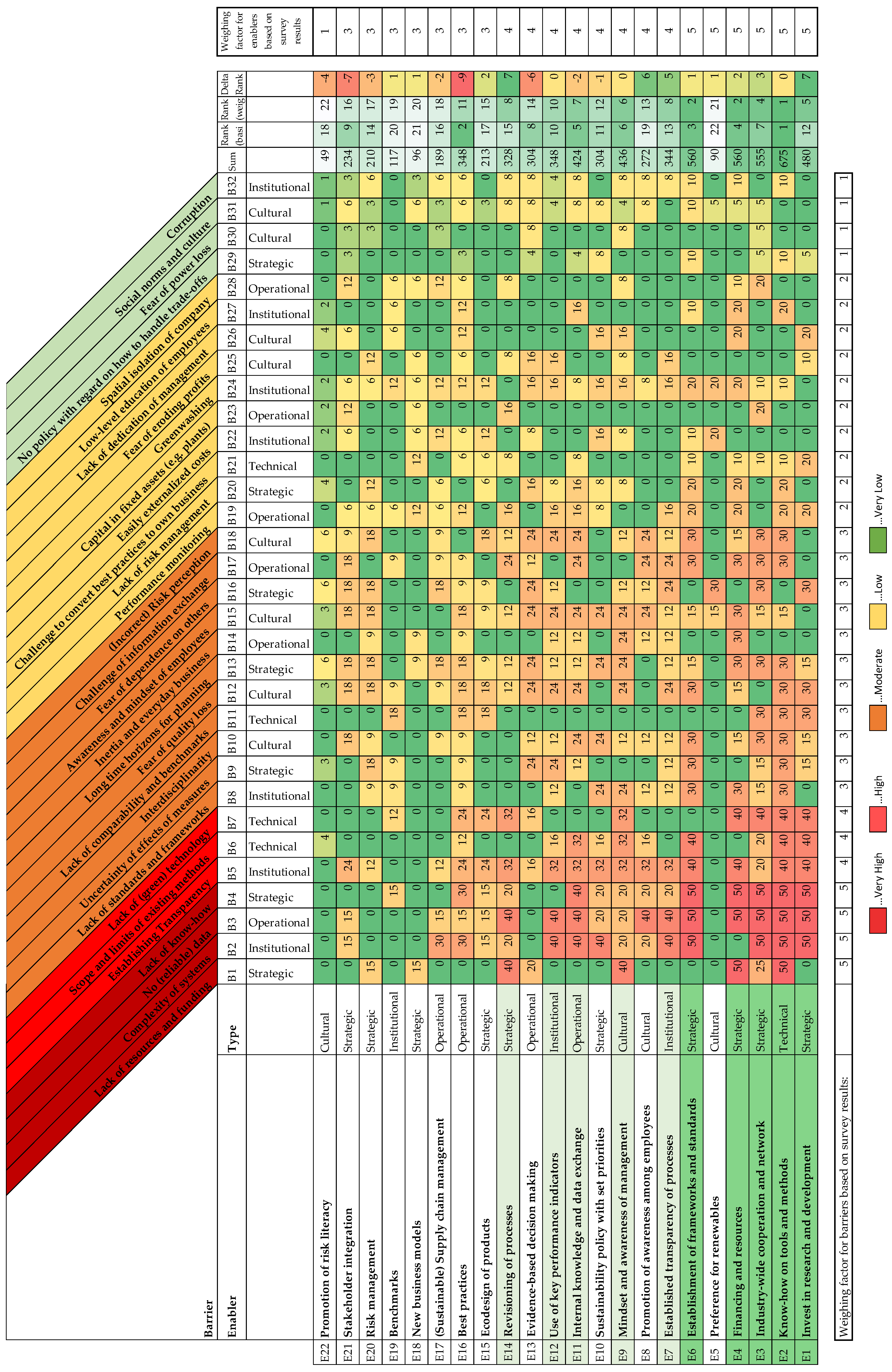

The result of the barrier and enabler assessment is summarized in

Table 1. Four items form a structural core of constraints perceived as the primary impediments to sustainability integration in LIB recycling. Those are namely the lack of resources and funding (s

b = 56), followed by the absence of (reliable) data and systemic complexity (each 55), and a lack of methodological know-how (53). Additional high-ranking barriers (45-47) include limited transparency of processes, difficulties in method application, and limited access to green technologies, reflecting concerns about both technical readiness and strategic orientation. Moderately scored barriers (40-44) include

organizational inertia, long planning horizons, and missing benchmarks. Some items consistently rank lower (score < 40), such as corruption, social norms, or power dynamics, and are considered less relevant in the LIB recycling context.

Stakeholder-specific rankings confirm the salience of the top barriers: lack of funding (13 mentions), data deficits (10), complexity (9), and greenwashing or organizational inertia (7-8). The close alignment between aggregate scores and contextual top-five prioritization suggests that these barriers are cross-cutting and widely acknowledged.

The enabler analysis reveals a concentrated set of high-leverage factors. Investments in R&D and (green) technology ranked highest (each se = 83), followed by methodological know-how (78), industry collaboration (75), and financing and resources (73). Other strongly rated enablers (64-71) include the use of renewable inputs, harmonized standards, and the establishment of process transparency. Mid-tier enablers (60–63) are the use of key performance indicators (KPIs), internal knowledge sharing, defined sustainability policies or revisioning of existing processes. New business models, benchmarks, risk management, risk literacy and stakeholder integration score lower but are still viewed positively.

Stakeholders most frequently select the following enablers in their own institutions as tentatively most helpful: management mindset (11), R&D investment (10), expert know-how (9), implementation of green technologies, going for renewables, and dedicated financing and resources (each 8), followed by internal knowledge exchange (7) and inter-firm cooperation (6).

3.4.2. Barrier Intervetion Mapping

Table 2 displays the combined results of the priority-ranked barrier–intervention heatmap, which integrates both the weighted scores of perceived hindering effects and the estimated leverage of enabling measures. Enablers that are perceived as highly effective generally act across multiple barriers simultaneously. This implies that enabling factors are not limited to one barrier but often provide leverage in several domains at once.

Aggregating the expected effectiveness of enabling effects across all barriers yields the following rank-ordered list: know-how on tools and methods (score: 675), financing and resources and establishment of frameworks and standards (both 560), industry-wide cooperation and networks (555), and investment in research and development (480).

When looking at the four most critical barrier items individually (

Table 2, B1-B4), the following intervention patterns emerge.

Lack of resources and funding (B1)

Unsurprisingly, financing and resources (score: 50) was ranked as the most decisive enabler to conquer lack of resources. However, know-how on tools and methods (50) is also perceived as effective, for example as supportive trait at funding applications or to uncover alternative financing mechanisms. Additional relevant measures include management mindset and awareness (40), revisioning of processes (40), industrial cooperation and networks (25), evidence-based decision-making (20), risk management systems (15), and new business models (15).

Complexity of systems (B2)

Stakeholders emphasized frameworks and standards (50), know-how on tools and methods (50), industry-wide cooperation and networks (50), and knowledge and data exchange (40) as highly valuable enablers. Further supporting measures are process transparency (40), key performance indicators (40), sustainability policies with set priorities (40), and investment in research and development (50).

No (reliable) data (B3)

This barrier closely reflects the systemic challenges of complexity. However, stakeholders rated financing and resources (50) and revisioning of processes (40) as particularly effective in enabling reliable data collection.

Lack of know-how (B4)

The same top enablers were considered decisive for this barrier: frameworks and standards, financing and resources, industry-wide cooperation and networks, and investment in research and development (all 50). They are complemented by internal knowledge and data exchange (40) and best practice implementation (30). Cultural and institutional factors such as sustainability policies, management and employee awareness, and process transparency (all 20) were viewed as less effective but still positively associated.

4. Discussion

4.1. Opportunity Mapping

The opportunity mapping, given in

Figure 3, shows that stakeholders strongly prioritize items that fall into the category of strategic leaps. Out of 27 identified opportunities, 12 were classified in this quadrant, including reduction of greenhouse gases, research and development of new technologies, reduction of environmental impacts, safeguarding of resource and energy supply, and climate change adaptation. The emphasis on emission reduction confirms the central role of LIB recycling in achieving broader climate goals.

The findings align with literature. Opportunities which highlight environmental impact reduction [

21,

26], resource and waste reduction [

17,

18,

23,

29], and increased production efficiency [

27] are assessed as highly effective but also demanding in terms of effort. Nonetheless, the recurrence of high-effort, high-impact items among the top-five opportunities chosen in organizational contexts suggests a strong orientation toward transformative change.

However, the mapping also reveals contradictions and divergences between literature and stakeholder assessments. A prominent example is new business models. While the literature frequently presents them as a key lever for advancing circular economy transitions [

17,

28,

30,

31,

32], stakeholders categorized them as money pits—high in effort with limited short-term payoff. This scepticism may reflect feasibility constraints, particularly given that stakeholders simultaneously ranked lack of resources and funding, lack of know-how, and inertia of everyday business among the most severe barriers.

Beyond business models, other economic opportunities also received a more critical assessment than suggested by the literature. Protection of assets and equity, diversification of revenue sources, and procurement of affordable resources were all judged as high in effort with limited benefits. In contrast, academic studies often highlight such business-related items as central contributions to competitiveness and resilience [

16,

33,

34,

35,

36].

This negative evaluation indicates that stakeholders place little confidence in the immediate economic pay-off of sustainability opportunities. At the same time, it suggests that short-term considerations dominate over potential long-term resilience gains, as highlighted in the literature’s stronger emphasis on strategic benefits of resource efficiency and diversification [

20,

33]. The consistently low ranking of risk literacy further supports this interpretation, given that the literature explicitly notes its importance as a governance enabler [

22,

37,

38].

A second field of divergence concerns softer management measures. Items such as legal compliance, health and safety management, superior stakeholder relations, and image and PR are rated positively in the literature [

15,

16,

23,

28], yet survey responses revealed more divided opinions. While some stakeholders acknowledged their value, others regarded them as conservative measures that at best deliver incremental improvements. This divergence reflects differing views on their contribution: whereas literature emphasizes their importance for social and reputational objectives, practitioners do not widely perceive them as transformative drivers of sustainability transitions.

In summary, the opportunity mapping reflects both ambition and caution. Stakeholders clearly recognize the transformative potential of sustainability measures such as greenhouse gas reduction and R&D of new technologies, even when these are costly and demanding. At the same time, they remain sceptical toward new business models and many economic opportunities, which they perceive as delivering limited short-term returns. Softer management measures divide opinion and are not seen as strong levers of change. Overall, the analysis points to a willingness to pursue transformative change but also highlights the constraints of feasibility, organizational capacity, and risk perception that shape the prioritization of opportunities.

4.2. Risk Landscape

The stakeholder-based risk mapping confirms that literature-based risks such as financial fragility [

20,

22,

31],regulatory volatility [

19,

20,

22],and knowledge attrition [

15] are perceived as key existential risks in the transition toward sustainable LIB recycling. The prioritizations of the top-five risks within individual organizations closely mirrors the aggregated survey scores, which reinforces the robustness of the overall risk landscape.

Referring to

Figure 4, a central finding is the strong emphasis placed on outside-in risks. Uncertainty and loss of financing were consistently rated highest across respondents, indicating that stakeholders are primarily concerned with pressures originating from markets, regulation, and financial systems rather than with risks generated internally. By contrast, items such as energy scarcity, supply chain failure, and increasing costs were not considered highly relevant threats in the survey, despite their prominence in recent global events and the academic literature [

15,

33,

34,

39]. This discrepancy may partly reflect the composition of the stakeholder group, where many participants stemmed from academia and thus face less direct exposure to market and supply chain pressures.

Dual risks also emerged as particularly salient. Loss of know-how, project failure, and image loss were ranked among the most critical items, representing risks that combine inside-out and outside-in dimensions. In the LIB recycling sector, inefficiencies in internal processes (inside-out) can rapidly trigger regulatory sanctions, financial penalties, or reputational damage (outside-in). These compound vulnerabilities illustrate the practical relevance of the double materiality perspective as embedded in sustainability reporting frameworks [

40,

41].

In contrast, inside-out risks were assigned comparatively less weight. Environmental impacts, risk to human health, and loss of ability to innovate were acknowledged but did not rank as highly critical like literature suggests [

19,

25]. This indicates that participants either perceive such risks as objectively lower or consider them more manageable within their organizational context. An alternative interpretation is that there is a systematic underestimation of corporate responsibility for risk generation across stakeholder types. Again, the academic-heavy composition of the sample may play a role, since institutional environments differ in their direct exposure to liability and operational risks.

The dominance of outside-in and dual risks has important implications. It underlines that stakeholders recognize the exposure of LIB recycling to external volatility, while at the same time acknowledging the potential for internal weaknesses to escalate into external consequences. Literature strongly recommends that such compound risks be addressed through systematic risk management [

20,

37]. Measures such as energy and resource security strategies, portfolio diversification, and improved working conditions for workforce retention are frequently highlighted as effective approaches [

26,

33,

34]. Strengthening risk literacy and embedding resilience into organizational routines are therefore crucial steps for enhancing the sector’s ability to withstand volatility and maintain legitimacy [

32].

In sum, the risk landscape demonstrates that stakeholders primarily focus on outside-in pressures, while giving comparatively less attention to inside-out risks. The prominence of dual risks highlights the interconnected nature of vulnerabilities in LIB recycling and supports the application of a double materiality perspective for both analysis and reporting.

4.3. Enabler and Barrier Assessment

The comparison of enablers and barriers between literature findings and stakeholder survey results shows both substantial overlap and meaningful discrepancies. At first glance, sustainable progress appears less a question of technical feasibility than of strategic and institutional alignment. However, this perspective captures only one dimension of a multi-faceted problem, since system complexity and interdependencies play a central role in shaping implementation pathways.

For enablers, several areas of convergence emerge. Both literature and stakeholder results emphasize the importance of know-how on tools and methods and the establishment of frameworks and standards [

38,

39,

42] as key preconditions for advancing sustainability , see

Table 1. Further common ground is visible in the recognition of key performance indicators [

43,

44], management mindset and awareness [

17,

28,

32], and supply chain management [

19,

34]. These findings suggest that technical capacities and structured governance instruments are widely regarded as necessary foundations.

At the same time, divergences highlight the contours of the implementation gap. Top-ranked enablers in the stakeholder survey include investment in research and development, implementation of (green) technologies, industrial collaboration and networks, and financing. These items revolve around translating academic insights into concrete action and often require substantial resources. So does literature [

25], however it assigns comparatively greater weight to institutional and cultural factors such as stakeholder integration [

17,

28] or industrial cooperation [

16,

35] and institutional pressure [

28]. This discrepancy indicates that while scholars identify soft enablers as crucial for long-term transition legitimacy, practitioners tend to prioritize interventions that are more directly under their control and less dependent on external actors.

For barriers, convergence is likewise evident. Both literature and survey results consistently identify lack of resources and funding, lack of know-how on tools and methods, and complexity of systems as core hindering factors [

15,

23,

37]. These shared assessments underscore that financial and methodological constraints, coupled with systemic complexity, remain central obstacles to LIB recycling.

Differences appear most clearly in the treatment of uncertainty and inertia of everyday business. Literature discusses these barriers more prominently [

16,

21,

22,

35], stressing the challenges posed by external volatility and the difficulty of changing entrenched routines. Stakeholders, by contrast, gave them lower weight, perhaps reflecting a stronger focus on immediate, tangible obstacles rather than more diffuse or long-term dynamics. Nevertheless, the persistence of organizational inertia and methodological uncertainty are typical of socio-technical transformations, where existing infrastructures, sunk investments, and established routines slow down the uptake of new solutions.

Taken together, the enabler and barrier assessment highlights that both perspectives agree on the structural bottlenecks but diverge in their prioritization of institutional and cultural factors. The survey results suggest that practitioners gravitate toward measures that are internally manageable and resource-focused, while the literature more strongly emphasizes the role of soft enablers for legitimacy and long-term sustainability. Recognizing both dimensions is crucial for bridging the gap between academic recommendations and organizational practice.

4.4. Barrier-Intevention Mapping

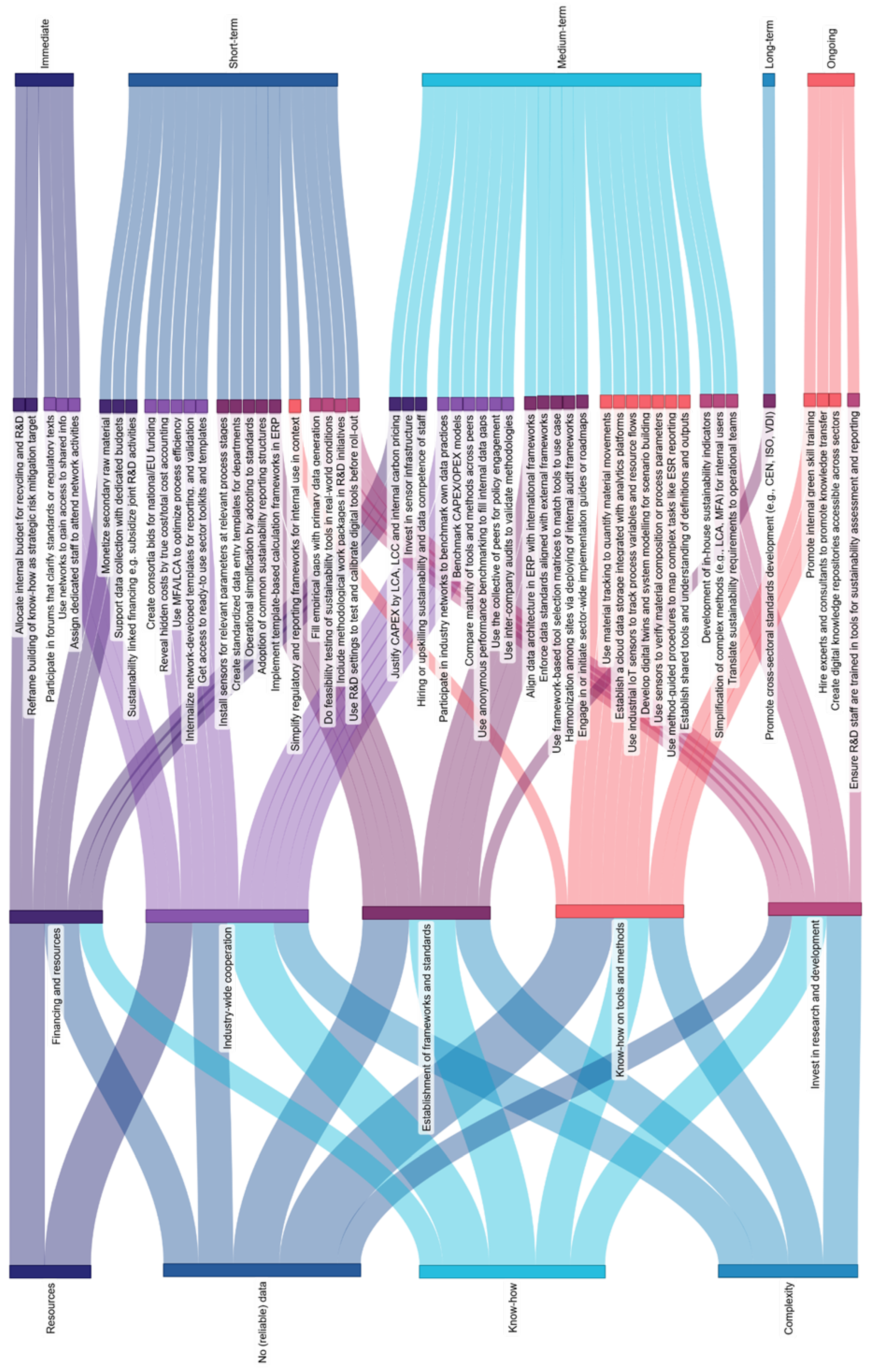

The barrier–intervention mapping in

Table 2 shows that enablers act less as single-purpose remedies than as multidimensional accelerators. Highly ranked items such as know-how on tools and methods, financing and resources, frameworks and standards, industry-wide cooperation and networks, and investment in research and development cut across multiple barriers and deliver spillover benefits beyond their primary scope. This systemic effect underlines that interventions cannot be confined to isolated domains but unfold their potential through interconnections.

The analysis also highlights a sequence of dependencies. Lack of resources and funding constitutes a foundational constraint. Without sufficient resources, companies are unable to establish data infrastructures, pursue R&D, or invest in training and capacity building. Reliable data is in turn essential for reducing the complexity of systems, while know-how is required to interpret data and apply sustainability tools in a meaningful way. These dependencies create cascading relationships: resources enable data generation, data supports methodological competence, and both together simplify complex systems. Such linkages can also lead to circular dependencies. Companies often need resources to collect and process data, but reliable data is required to justify resource allocation in the first place. This creates a feedback loop that can stall implementation, reinforcing the impression of sustainability as a costly and overly complex undertaking.

The survey results therefore make clear that interventions should not be designed as isolated countermeasures. Instead, they need to be sequenced strategically, with early emphasis on financial governance and training to build a foundation for subsequent investments in data infrastructures and methodological application. Once in place, these steps create the conditions for reducing perceived complexity and embedding sustainability measures into routine operations.

4.5. From Map to Roadmap

Translating the barrier–intervention mapping into a roadmap highlights how the identified constraints can be addressed through coordinated and sequenced action, see

Figure 5. Four barriers stand out as particularly critical: lack of resources and funding, no (reliable) data, complexity of systems, and lack of know-how. Their strong interdependencies mean that improvements in one area often enable progress in others. For example, investment in digital infrastructure requires both financial resources and trained personnel; reducing complexity depends on methodological know-how and standardized frameworks; and the availability of resources determines whether organizations can pursue research and development or training to support data generation and tool uptake.

The roadmap developed from these insights therefore proposes a layered approach. Addressing lack of resources and funding is foundational, as it underpins the capacity to act in other domains. Beyond liquidity, this barrier reflects issues of resource governance, since sustainability initiatives often compete with core operations in capital-intensive sectors such as LIB recycling. Establishing dedicated budgets, applying instruments such as LCA or life cycle costing (LCC) to justify investments, and participating in sectoral consortia or EU-level funding programs can help strengthen the financial base.

With resources secured, the next step is to address no (reliable) data. Standardized protocols, sensor-based monitoring, and centralized platforms can improve data availability and integration, while benchmarking and audits support comparability. Reliable data is essential not only for reporting credibility but also for reducing perceptions of uncertainty and enabling evidence-based decision-making.

Reducing complexity of systems then becomes feasible. Structured tool-selection frameworks, simplified calculators for early-stage assessments, and ready-to-use templates can lower entry barriers. Appointing internal “method translators” can further help organizations navigate between different tools and reporting requirements.

Finally, lack of know-how needs to be tackled through systematic capacity building. Targeted training programs, recruitment of method specialists, and harmonization of terminology across departments can build internal competence. Embedding training within reporting cycles, such as those required by legal frameworks [

45], creates feedback loops between compliance and learning, strengthening the long-term integration of sustainability tools.

Overall, the roadmap emphasizes that interventions should be sequenced according to organizational maturity and context. Rather than prescribing a one-size-fits-all blueprint, it provides a flexible guide that allows organizations to prioritize interventions based on their current capacities, while recognizing that resources, data, know-how, and complexity reduction are inseparably linked.

4.6. Transferability and Limitations

While the findings offer valuable insights for advancing sustainability in LIB recycling, they are shaped by the specific context of the study. The stakeholder survey was embedded in the Austrian COMET module FuLIBatteR, characterized by an innovation-driven environment and close cooperation between academia, industry, and policy actors. This setting ensured technically informed contributions but also introduces certain boundary conditions that affect transferability.

The composition of the survey group is a key limitation. Of the 26 participants, a large share came from academia, while small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), informal sector actors, and non-governmental organizations were underrepresented. This imbalance may have influenced the relative weight assigned to risks, barriers, and enablers, since organizations with fewer resources and stronger cost pressures might prioritize differently. As a result, the findings should be understood as sector-informed rather than sector-representative.

The survey design itself also presents constraints. Although the questionnaire was pre-tested and randomized to mitigate bias, some participants reported it as cognitively demanding and repetitive. This raises the possibility of attention loss or satisficing behaviour. While no evidence of rushed answering was observed, future studies could benefit from modular or adaptive designs to reduce respondent fatigue.

Methodological considerations further shape the results. The barrier–intervention mapping required authorial judgment in assigning basic scores to enabler–barrier combinations. Although these decisions were transparently documented and triangulated with literature and stakeholder input, they inevitably involve an interpretive dimension. In addition, the very high internal consistency of the Likert-scale constructs (Cronbach’s α > 0.99) suggests overlapping themes and multidimensionality, which supports a systems-thinking interpretation but also complicates precise differentiation between individual items.

Finally, the transferability of the roadmap is conditioned by contextual factors. While many of the barriers and enablers identified, such as lack of resources and funding, no (reliable) data, complexity of systems, and lack of know-how, are systemic in nature and likely relevant in other contexts, their specific manifestations may differ across national, industrial, or organizational settings. Adaptation will therefore be necessary when applying the framework elsewhere.

Despite these limitations, the mixed-methods approach proved robust and generated practice-oriented insights. By integrating literature findings with stakeholder perspectives, the study provides a structured framework that can guide sustainability implementation in LIB recycling and may serve as a transferable model for related resource-intensive sectors.

4.7. Overlooked but Emerging Dimensions

Cybersecurity did not emerge as a distinct risk or enabler in either the literature or the stakeholder survey, despite the sector’s growing reliance on digital infrastructures, sensor networks, and cloud-based platforms. This omission points to a conceptual blind spot: data systems are often treated as neutral tools for transparency, while their vulnerability is overlooked. The neglect of cybersecurity may stem from disciplinary silos, as IT security is rarely integrated into recycling or sustainability frameworks. Yet, without robust safeguards, digitalization risks undermining rather than supporting transparency and resilience. Future work should therefore explicitly include cybersecurity in risk and enabler assessments, treating it as part of operational resilience to ensure that digitalization strengthens rather than weakens system robustness.

5. Conclusions

The main findings of this study can be summarized as follows:

The will to act is there.

Risks are underestimated.

Resources are the bottleneck.

We face a socio-technical challenge.

Closing the implementation gap is key.

Stakeholders clearly see many opportunities for sustainability in LIB recycling and demonstrate willingness to pursue them. Items such as greenhouse gas reduction,

waste reduction, and research and development of new technologies were strongly prioritized, even though they are resource-intensive and demanding. This shows that ambition is not the limiting factor; rather, the challenge lies in creating the right conditions for implementation.

Risks remain underappreciated in organizational decision-making. While technical risk management is often established, it only addresses one dimension. The broader sustainability risk landscape includes complex interdependencies across environmental, social, and governance domains. Outside-in risks such as uncertainty and loss of financing dominate stakeholder concerns, but dual risks like loss of know-how and image loss reveal that internal weaknesses can rapidly trigger external consequences. Strengthening integrated risk management and risk literacy is therefore essential for building resilience.

Across both literature and stakeholder results, lack of resources and funding emerges as the foundational barrier. Without sufficient financial and human capital, data collection, methodological development, and process innovation remain out of reach. The gap is not one of awareness but of resource governance: stakeholders recognize what is needed, but lack the means to pursue it at scale.

The findings highlight that technical solutions alone are insufficient. Cultural and institutional factors such as management mindset, stakeholder integration, and employee awareness are frequently undervalued in aggregate assessments, even though they prove decisive in practice. With too much focus on technical fixes, implementation risks stalling because the human and organizational dimensions are overlooked. LIB recycling, like other sustainability transitions, is therefore not only a technological but also a socio-technical challenge.

The study confirms that an implementation gap persists between ambition and practice. Stakeholders know the opportunities, but structural barriers, limited resources, and insufficient attention to cultural enablers dampen progress. The barrier–intervention mapping and the derived roadmap show that interventions must be sequenced strategically: securing resources first, then building data infrastructures, strengthening know-how, and reducing complexity. Addressing these interdependencies, while embedding cultural legitimacy and institutional trust, is key to closing the gap and accelerating sustainable progress.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1.1: Literature list of opportunities; Table S1.2: Literature list of risks; Table S1.3: Literature list of intern enablers; Table S1.4: Literature list of intern barriers. https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s2, Figure S2.1: Survey Questionnaire. https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s3, Figure S3.1: Collected Answers of the Survey

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R. and S.R.; methodology, B.R.; software, B.R.; validation, B.R., S.R., A.A., and T.N.; formal analysis, B.R.; investigation, B.R. and S.R.; resources, R.P.; data curation, B.R., writing—original draft preparation, B.R.; writing—review and editing, B.R., S.R., and T.N.; visualization, B.R.; supervision, T.N. and R.P.; project administration, T.N. and B.R.; funding acquisition, T.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding support of K1-MET GmbH, the metallurgical competence center. The Module FuLIBatteR is supported by COMET (Competence Center for Excellent Technologies), the Austrian program for competence centers. COMET is funded by the Federal Ministry of Innovation, Mobility and Infrastructure (BMIMI), the Federal Ministry Economy, Energy and Tourism (BMWET), the Austrian Federal States of Upper Austria and Styria, as well as the Styrian Business Promotion Agency (SFG). Furthermore, Upper Austrian Research GmbH continuously supports the Module. In addition to the public funding from COMET, this Module is partially financed by the company partners Audi, BRAIN Biotech, Ebner Industrieofenbau, RHI Magnesita, Saubermacher Dienstleistungs AG, TÜV SÜD Landesgesellschaft Österreich, VTU Engineering, and voestalpine High-Performance Metals, as well as the scientific partners ACIB, Coventry University, Technical University of Leoben, BOKU University, and UVR-FIA.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data of the survey presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author, for aggregated results please refer to the supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks goes to SankeyMATIC and their free to use and open source material flow diagram webpage. During the preparation of this work the author(s) used DeepL and ChatGPT by OpenAI in order to assist in language refinement, outline structuring of the manuscript and meaningful shortening of text. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EU |

European |

| LCA |

Life cycle assessment |

| LCC |

Life cycle costing |

| LIB |

Lithium-ion battery |

| Lit. |

Literature |

| PR |

Public relations |

| Qual. |

qualitative |

| R&D |

Research and development |

| Surv. |

Survey |

References

- European Commission, The European Green Deal. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_de.

- European Commission, Ed., The Clean Industrial Deal: A joint roadmap for competitiveness and decarbonisation.: Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of Regions. Brüssel, 2025.

- European Commission, Ed., Circular Economy Action Plan, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.eu2020.de/resource/blob/2429166/156d2d98b66b2ff28b6990161eed91e9/12-17-kreislaufwirtschaftsaktionsplan-bericht-de-data.pdf.

- M. Machala et al., Life cycle comparison of industrial-scale lithium-ion battery recycling and mining supply chains, 2023.

- J. A. Llamas-Orozco et al., “Estimating the environmental impacts of global lithium-ion battery supply chain: A temporal, geographical, and technological perspective,” PNAS nexus, vol. 2, no. 11, pgad361, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Mrozik, M. A. Rajaeifar, O. Heidrich, and P. Christensen, “Environmental impacts, pollution sources and pathways of spent lithium-ion batteries,” Energy Environ. Sci., vol. 14, no. 12, pp. 6099–6121, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Boyden, V. K. Soo, and M. Doolan, “The Environmental Impacts of Recycling Portable Lithium-Ion Batteries,” Procedia CIRP, vol. 48, pp. 188–193, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Harper et al., “Recycling lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles,” Nature, vol. 575, no. 7781, pp. 75–86, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma et al., “The evolution of lithium-ion battery recycling,” Nat. Rev. Clean Technol., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 75–94, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. J. Baum, R. E. Bird, X. Yu, and J. Ma, “Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling─Overview of Techniques and Trends,” ACS Energy Lett., vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 712–719, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Xu, D. H. S. Tan, B. Jiao, H. Gao, X. Yu, and Z. Chen, “A Materials Perspective on Direct Recycling of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Principles, Challenges and Opportunities,” Adv Funct Materials, vol. 33, no. 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Lv, Z. Wang, H. Cao, Y. Sun, Y. Zhang, and Z. Sun, “A Critical Review and Analysis on the Recycling of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries,” ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 1504–1521, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Husmann, A.-R. Ali, F. Cerdas, and C. Herrmann, “The influence of stakeholder perspectives on the end-of-life allocation in the life cycle assessment of lithium-ion batteries,” Front. Sustain., vol. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. K. Biswal, B. Zhang, P. Thi Minh Tran, J. Zhang, and R. Balasubramanian, “Recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries for a sustainable future: recent advancements,” Chemical Society reviews, vol. 53, no. 11, pp. 5552–5592, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Luthra, M. Sharma, A. Kumar, S. Joshi, E. Collins, and S. Mangla, “Overcoming barriers to cross-sector collaboration in circular supply chain management: a multi-method approach,” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, vol. 157, p. 102582, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Veleva and G. Bodkin, “Corporate-entrepreneur collaborations to advance a circular economy,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 188, pp. 20–37, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M.-L. Tseng, T. P. T. Tran, H. M. Ha, T.-D. Bui, and M. K. Lim, “Causality of circular business strategy under uncertainty: A zero-waste practices approach in seafood processing industry in Vietnam,” Resources, Conservation and Recycling, vol. 181, p. 106263, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. U. Zaman, “A comprehensive review of the development of zero waste management: lessons learned and guidelines,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 91, pp. 12–25, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Nimsai, C. Yoopetch, and P. Lai, “Mapping the Knowledge Base of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Bibliometric Literature Review,” Sustainability, vol. 12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Liu, Y. Fan, B. Xue, T. Wang, and Q. Chao, “Feature extraction and classification of climate change risks: a bibliometric analysis,” Environmental monitoring and assessment, vol. 194, no. 7, p. 495, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Harris, M. Martin, and D. Diener, “Circularity for circularity’s sake? Scoping review of assessment methods for environmental performance in the circular economy,” Sustainable Production and Consumption, vol. 26, pp. 172–186, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Shaktawat and S. Vadhera, “Risk management of hydropower projects for sustainable development: a review,” Environ Dev Sustain, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 45–76, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Song, J. Li, and X. Zeng, “Minimizing the increasing solid waste through zero waste strategy,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 104, pp. 199–210, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Sousa, L. M. Martelo, A. T. Marques, M. M.S.M. Bastos, and H. M.V.M. Soares, “A closed and zero-waste loop strategy to recycle the main raw materials (gold, copper and fiber glass layers) constitutive of waste printed circuit boards,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 434, p. 134604, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li et al., “Quantitative sustainable design (QSD) for the prioritization of research, development, and deployment of technologies: a tutorial and review,” Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol., vol. 8, no. 11, pp. 2439–2465, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Ang, E. T. Saw, W. He, X. Dong, and S. Ramakrishna, “Sustainability framework for pharmaceutical manufacturing (PM): A review of research landscape and implementation barriers for circular economy transition,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 280, p. 124264, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Fantke and N. Illner, “Goods that are good enough: Introducing an absolute sustainability perspective for managing chemicals in consumer products,” Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, vol. 15, pp. 91–97, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Nassani, N. Isac, J. Rosak-Szyrocka, Z. Yousaf, and M. Haffar, “Institutional Pressures and Circular Economy Target Performance: Are Zero Waste Practices and Enviropreneurship Worth Pursuing?,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 2952, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Mulvaney, R. M. Richards, M. D. Bazilian, E. Hensley, G. Clough, and S. Sridhar, “Progress towards a circular economy in materials to decarbonize electricity and mobility,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 137, p. 110604, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Masoudipour, H. Amirian, and R. Sahraeian, “A novel closed-loop supply chain based on the quality of returned products,” Journal of Cleaner Production, pp. 344–355.

- M. A. Momeni, V. Jain, K. Govindan, A. Mostofi, and S. J. Fazel, “A novel buy-back contract coordination mechanism for a manufacturer-retailer circular supply chain regenerating expired products,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 375, p. 133319, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Scheel and B. Bello, “Transforming Linear Production Chains into Circular Value Extended Systems,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 7, p. 3726, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Axon and R. C. Darton, “Sustainability and risk – a review of energy security,” Sustainable Production and Consumption, vol. 27, pp. 1195–1204, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Iqbal, Y. Kang, and H. W. Jeon, “Zero waste strategy for green supply chain management with minimization of energy consumption,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 245, p. 118827, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Tang, Y. He, and M. Salling, “Optimal pricing and production strategies for two manufacturers with industrial symbiosis,” International Journal of Production Economics, vol. 235, p. 108084, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Lieder and A. Rashid, “Towards circular economy implementation: a comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 115, pp. 36–51, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Owen, “What makes climate change adaptation effective? A systematic review of the literature,” Global Environmental Change, vol. 62, p. 102071, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Glavič, Z. N. Pintarič, and M. Bogataj, “Process Design and Sustainable Development—A European Perspective,” Processes, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 148, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Hampus and M. Ljunggren, “Towards comprehensive assessment of mineral resource availability? Complementary roles of life cycle, life cycle sustainability and criticality assessments,” Resources, Conservation & Recycling, no. 167, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Office, Richtlinie (EU) 2022/2464 des europäischen Parlaments und vom 14. Dezember 2022 zur Änderung der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 537/2014 und der Richtlinien 2004/109/EG, 2006/43/EG und 2013/34/EU hinsichtlich der Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung von Unternehmen: CSRD-Richtlinie, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022L2464.

- A. Primec and J. Belak, “Sustainable CSR: Legal and Managerial Demands of the New EU Legislation (CSRD) for the Future Corporate Governance Practices,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 24, p. 16648, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Zanghelini, E. Cherubini, and S. R. Soares, “How Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) is aiding Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) in results interpretation,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 172, pp. 609–622, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Colla, A. Ioannou, and G. Falcone, “Critical review of competitiveness indicators for energy projects,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 125, p. 109794, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Hernandez-Betancur and G. J. Ruiz-Mercado, “SUSTAINABILITY INDICATORS FOR END-OF-LIFE CHEMICAL RELEASES AND POTENTIAL EXPOSURE,” Current opinion in chemical engineering, vol. 26, pp. 157–163, 2019. [CrossRef]

- EFRAG, First Set of draft ESRS. [Online]. Available: www.efrag.org/lab6 (accessed: Jun. 30 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

5

5 5

5 5

5 5

5 5

5 5

5 4

4 4

4 4

4 4

4 4

4 4

4 4

4 4

4 4

4 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 1

1 5

5 5

5 5

5 5

5 4

4 4

4 4

4 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 3

3 2

2 2

2 2

2 2

2 2

2 2

2 2

2 2

2 2

2 2

2 1

1 1

1 1

1 1

1