Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

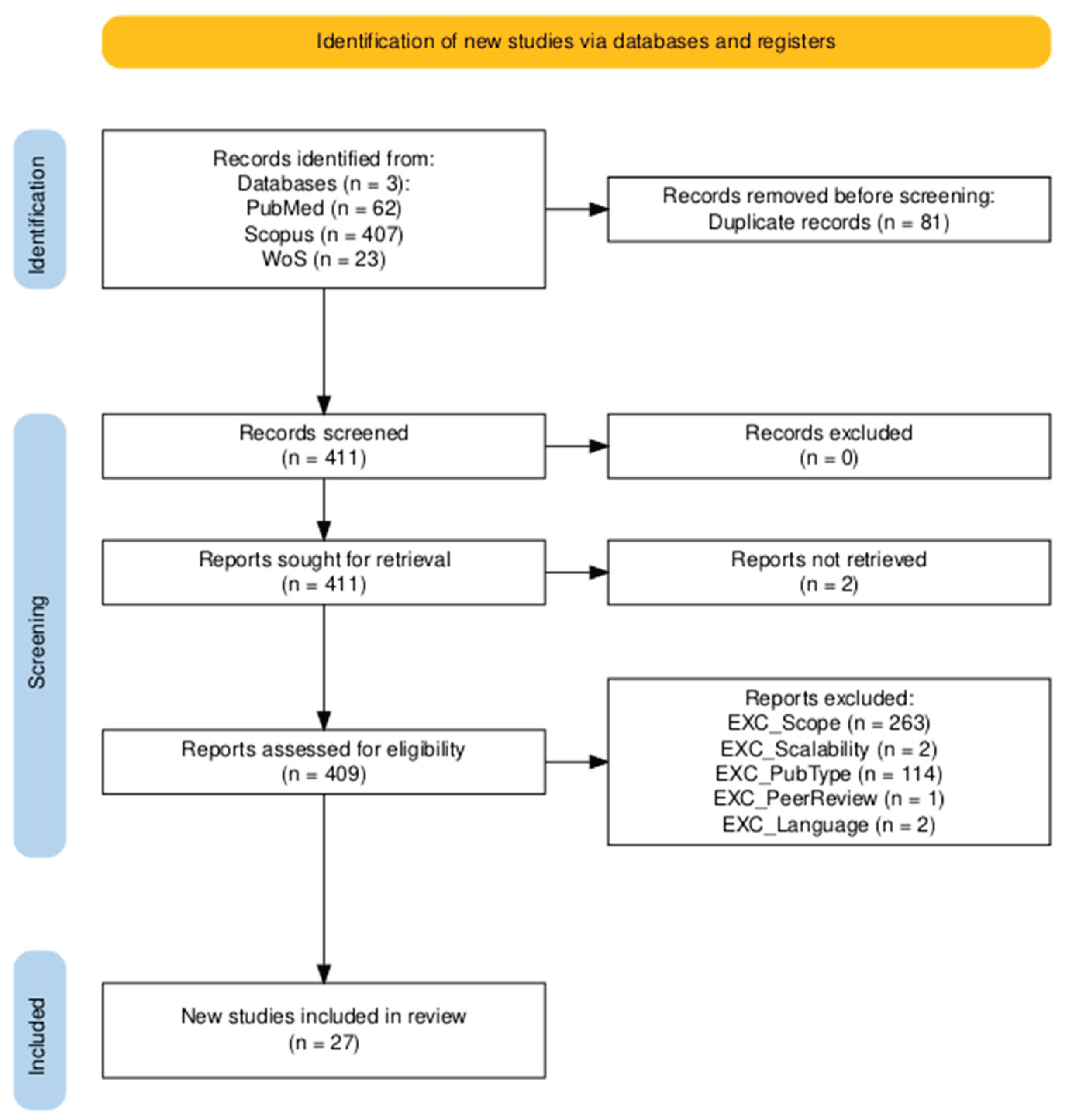

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Study Overlap and Redundancy in Umbrella Reviews

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Assessment

3.2. Study Overlap

3.3. Q1: Predictive Models for COPD Exacerbations Using Biosignals and AI

3.3.1. Overview of Populations and Data Sources

3.3.2. AI Models and Performance

3.4. Q2: Impact of Digital Health Interventions on COPD Management, Quality of Life, and Medication Adherence

3.4.1. Study Populations, Intervention Types, and Comparators

3.4.2. Outcomes of Digital Interventions for COPD

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of This Umbrella Review

4.2. Gaps and Limitations in Literature

4.3. Future Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Adm | Hospital Admission |

| AE | Acute Exacerbation |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AECOPD | Acute Exacerbation COPD |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CAT | COPD Assessment Test |

| CCQ | Clinical COPD Questionnaire |

| CCA | Corrected Covered Area |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CRQ | Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DNN | Deep Neural Netwokr |

| DT | Decition Tree |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| EQ-5D | EuroQol 5-Dimension |

| ER | Emergency Room |

| FEV₁ | Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second |

| FVC | Forced Vital Capacity |

| GOLD | Global Initiative for COPD |

| HCP | Healthcare Professional |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| HRQoL | Heart Rate Quality of Life |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| ISWT | Incremental Shuttle Walk Test |

| IVR | Interactive Voice Response |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MA | Meta-Analysis |

| MAQ | Medication Adherence Questionnaire |

| MG Test | Medication-taking Graph Test |

| mHealth | Mobile Health |

| MID | Minimal Important Difference |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MMAS-8 | Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 |

| mMRC | Modified Medical Research Council (Dyspnea Scale) |

| NCSI | Nijmegen Clinical Screening Instrument |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PDA | Personal Digital Assistant |

| PCS | Physical Component Summary (from SF-12/SF-36) |

| PEARL | Dyspnea, Eosinopenia, Consolidation, Acidemia, and atriaL fibrillation Score |

| PR | Pulmonary Rehabilitation |

| PROs | Patient Reported Outcomes |

| Pts | Patients |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RPM | Remote Patient Monitoring |

| RR | Respiratory Rate |

| Self-mgmt | Self-management interventions |

| SF-36 | Short Form-36 Health Survey |

| SGRQ | St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire |

| SMD | Standardized Mean Difference |

| SpO₂ | Peripheral Capillary Oxygen Saturation |

| SR | Systematic Review |

| STAIN | Spatio-Temporal Artificial Intelligence Network |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TUG | Timed Up and Go test |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| WAQI | World Air Quality Index |

| 6MWD | 6-Minute Walk Distance |

| 6MWT | 6-Minute Walk Test |

References

- S. C. Lareau, B. S. C. Lareau, B. Fahy, P. Meek, and A. Wang, “Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),” Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med., vol. 199, no. 1, pp. P1–P2, Jan. 2019.

- J. L. Lopez-Campos, C. J. L. Lopez-Campos, C. Calero, and E. Quintana-Gallego, “Symptom variability in COPD: a narrative review,” Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis., vol. 8, pp. 231–238, 13. 20 May.

- I. Iheanacho, S. I. Iheanacho, S. Zhang, D. King, M. Rizzo, and A. S. Ismaila, “Economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): A systematic literature review,” Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis., vol. 15, pp. 439–460, Feb. 2020.

- “Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).” Accessed: Jul. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.

- V. Kim and S. D. Aaron, “What is a COPD exacerbation? Current definitions, pitfalls, challenges and opportunities for improvement,” Eur. Respir. J., vol. 52, no. 5, p. 1801261, Nov. 2018.

- T. A. R. Seemungal, J. R. T. A. R. Seemungal, J. R. Hurst, and J. A. Wedzicha, “Exacerbation rate, health status and mortality in COPD--a review of potential interventions,” Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis., vol. 4, pp. 203–223, Jun. 2009.

- D. M. Halpin, M. D. M. Halpin, M. Miravitlles, N. Metzdorf, and B. Celli, “Impact and prevention of severe exacerbations of COPD: a review of the evidence,” Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis., vol. 12, pp. 2891–2908, Oct. 2017.

- D. Dias and J. Paulo Silva Cunha, “Wearable Health Devices-vital sign monitoring, systems and technologies,” Sensors (Basel), vol. 18, no. 8, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Bolpagni, S. M. Bolpagni, S. Pardini, M. Dianti, and S. Gabrielli, “Personalized stress detection using biosignals from wearables: A scoping review,” Sensors (Basel), vol. 24, no. 10, p. 3221, 24. 20 May.

- M. de Zambotti, N. M. de Zambotti, N. Cellini, A. Goldstone, I. M. Colrain, and F. C. Baker, “Wearable sleep technology in clinical and research settings,” Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., vol. 51, no. 7, pp. 1538–1557, Jul. 2019.

- C.-T. Wu et al., “Acute exacerbation of a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prediction system using wearable device data, machine learning, and deep learning: Development and cohort study,” JMIR MHealth UHealth, vol. 9, no. 5, p. e22591, 21. 20 May.

- C.-C. Hsiao, C.-Y. C.-C. Hsiao, C.-Y. Chu, R.-G. Lee, J.-H. Chang, and C.-L. Tseng, “Wearable devices for early warning of acute exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients,” in 2023 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), IEEE, Oct. 2023, pp. 4513–4518.

- J.-L. Pépin, B. J.-L. Pépin, B. Degano, R. Tamisier, and D. Viglino, “Remote monitoring for prediction and management of acute exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD),” Life (Basel), vol. 12, no. 4, p. 499, Mar. 2022.

- H. Ding, F. H. Ding, F. Fatehi, A. Maiorana, N. Bashi, W. Hu, and I. Edwards, “Digital health for COPD care: the current state of play,” J. Thorac. Dis., vol. 11, no. Suppl 17, pp. S2210–S2220, Oct. 2019.

- B. S. Pineda, R. B. S. Pineda, R. Mejia, Y. Qin, J. Martinez, L. G. Delgadillo, and R. F. Muñoz, “Updated taxonomy of digital mental health interventions: a conceptual framework,” MHealth, vol. 9, p. 28, Jun. 2023.

- J. D. Piette et al., “Effects of accessible health technology and caregiver support posthospitalization on 30-day readmission risk: A randomized trial,” Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf., vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 109–117, Feb. 2020.

- H. M. G. Glyde, C. H. M. G. Glyde, C. Morgan, T. M. A. Wilkinson, I. T. Nabney, and J. W. Dodd, “Remote patient monitoring and machine learning in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Dual systematic literature review and narrative synthesis,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 26, p. e52143, Sep. 2024.

- L. A. Smith et al., “Machine learning and deep learning predictive models for long-term prognosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Lancet Digit. Health, vol. 5, no. 12, pp. e872–e881, Dec. 2023.

- G. Shaw, M. E. G. Shaw, M. E. Whelan, L. C. Armitage, N. Roberts, and A. J. Farmer, “Are COPD self-management mobile applications effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis,” NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med., vol. 30, no. 1, p. 11, Apr. 2020.

- Alastair Watson and Tom, M.A. Wilkinson, “Digital healthcare in COPD management: a narrative review on the advantages, pitfalls, and need for further research. [CrossRef]

- M. H. J. Schulte, J. J. M. H. J. Schulte, J. J. Aardoom, L. Loheide-Niesmann, L. L. L. Verstraete, H. C. Ossebaard, and H. Riper, “Effectiveness of eHealth interventions in improving medication adherence for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma: Systematic review,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 23, no. 7, p. e29475, Jul. 2021.

- S. A. H. Tabatabaei, P. S. A. H. Tabatabaei, P. Fischer, H. Schneider, U. Koehler, V. Gross, and K. Sohrabi, “Methods for adventitious respiratory sound analyzing applications based on smartphones: A survey,” IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng., vol. 14, pp. 98–115, 2021.

- M. J. Page et al., “The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews,” BMJ, vol. 372, p. n71, Mar. 2021.

- R. Fernandez, A. M. R. Fernandez, A. M. Sharifnia, and H. Khalil, “Umbrella Reviews: A methodological guide,” Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs., Jan. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. J. Shea et al., “AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both,” BMJ, p. j4008, Sep. 2017.

- D. Pieper, S.-L. D. Pieper, S.-L. Antoine, T. Mathes, E. A. M. Neugebauer, and M. Eikermann, “Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview,” J. Clin. Epidemiol., vol. 67, no. 4, pp. 368–375, Apr. 2014.

- K. I. Bougioukas, T. K. I. Bougioukas, T. Diakonidis, A. C. Mavromanoli, and A.-B. Haidich, “ccaR: A package for assessing primary study overlap across systematic reviews in overviews,” Res. Synth. Methods, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 443–454, 23. 20 May.

- M. Kirvalidze, A. M. Kirvalidze, A. Abbadi, L. Dahlberg, L. B. Sacco, A. Calderón-Larrañaga, and L. Morin, “Estimating pairwise overlap in umbrella reviews: Considerations for using the corrected covered area (CCA) index methodology,” Res. Synth. Methods, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 764–767, Sep. 2023.

- Z. Xu, F. Z. Xu, F. Li, Y. Xin, Y. Wang, and Y. Wang, “Prognostic risk prediction model for patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD): a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Respir. Res., vol. 25, no. 1, p. 410, Nov. 2024.

- Z. Chen, J. Z. Chen, J. Hao, H. Sun, M. Li, Y. Zhang, and Q. Qian, “Applications of digital health technologies and artificial intelligence algorithms in COPD: systematic review,” BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak., vol. 25, no. 1, p. 77, Feb. 2025.

- D. Sanchez-Morillo, M. A. D. Sanchez-Morillo, M. A. Fernandez-Granero, and A. Leon-Jimenez, “Use of predictive algorithms in-home monitoring of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma: A systematic review: A systematic review,” Chron. Respir. Dis., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 264–283, Aug. 2016.

- B. Guerra, V. B. Guerra, V. Gaveikaite, C. Bianchi, and M. A. Puhan, “Prediction models for exacerbations in patients with COPD,” Eur. Respir. Rev., vol. 26, no. 143, p. 160061, Jan. 2017.

- S. K. Kim, S. Y. S. K. Kim, S. Y. Park, H. R. Hwang, S. H. Moon, and J. W. Park, “Effectiveness of mobile health intervention in medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” J. Med. Syst., vol. 49, no. 1, p. 13, Jan. 2025.

- G. Zangger et al., “Benefits and harms of digital health interventions promoting physical activity in people with chronic conditions: Systematic review and meta-analysis,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 25, p. e46439, Jul. 2023.

- C. Chung, J. W. C. Chung, J. W. Lee, S. W. Lee, and M.-W. Jo, “Clinical efficacy of mobile app-based, self-directed pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis,” JMIR MHealth UHealth, vol. 12, p. e41753, Jan. 2024.

- H. Chang, J. H. Chang, J. Zhou, Y. Chen, X. Wang, and Z. Wang, “Comparative effectiveness of eHealth interventions on the exercise endurance and quality of life of patients with COPD: A systematic review and network meta-analysis,” J. Clin. Nurs., vol. 33, no. 9, pp. 3711–3720, Aug. 2024.

- A. Aburub, M. Z. A. Aburub, M. Z. Darabseh, R. Badran, O. Eilayyan, A. M. Shurrab, and H. Degens, “The effects of digital health interventions for pulmonary rehabilitation in people with COPD: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials,” Medicina (Kaunas), vol. 60, no. 6, p. 963, Jun. 2024.

- S. Kyriazakos et al., “Benchmarking the clinical outcomes of Healthentia SaMD in chronic disease management: a systematic literature review comparison,” Front. Public Health, vol. 12, p. 1488687, Dec. 2024.

- H. Ariyanto and E. M. Rosa, “Telehealth improves quality of life of COPD patients: systematic review and meta-analysis,” Kontakt, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 252–259, Sep. 2024.

- A. Paleo, C. A. Paleo, C. Carretta, F. Pinto, E. Saltori, J. G. Aroca, and Á. Puelles, “Mobile phone-mediated interventions to improve adherence to prescribed treatment in chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A systematic review,” Adv. Respir. Med., vol. 93, no. 2, p. 8, Apr. 2025.

- M. A. M. Ferreira, A. F. M. A. M. Ferreira, A. F. Dos Santos, B. Sousa-Pinto, and L. Taborda-Barata, “Cost-effectiveness of digital health interventions for asthma or COPD: Systematic review,” Clin. Exp. Allergy, vol. 54, no. 9, pp. 651–668, Sep. 2024.

- Y. Dai, H. Y. Dai, H. Huang, Y. Zhang, N. He, M. Shen, and H. Li, “The effects of telerehabilitation on physiological function and disease symptom for patients with chronic respiratory disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMC Pulm. Med., vol. 24, no. 1, p. 305, Jun. 2024.

- A. Verma, A. A. Verma, A. Behera, R. Kumar, N. Gudi, A. Joshi, and K. M. M. Islam, “Mapping of digital health interventions for the self-management of COPD: A systematic review,” Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health, vol. 24, no. 101427, p. 101427, Nov. 2023.

- S. Isernia et al., “Characteristics, components, and efficacy of telerehabilitation approaches for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 19, no. 22, p. 15165, Nov. 2022.

- Y.-Y. Liu, Y.-J. Y.-Y. Liu, Y.-J. Li, H.-B. Lu, C.-Y. Song, T.-T. Yang, and J. Xie, “Effectiveness of internet-based self-management interventions on pulmonary function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” J. Adv. Nurs., vol. 79, no. 8, pp. 2802–2814, Aug. 2023.

- M. D. M. Martínez-García, J. D. M. D. M. Martínez-García, J. D. Ruiz-Cárdenas, and R. A. Rabinovich, “Effectiveness of smartphone devices in promoting physical activity and exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review,” COPD, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 543–551, Oct. 2017.

- C. McCabe, M. C. McCabe, M. McCann, and A. M. Brady, “Computer and mobile technology interventions for self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., vol. 5, no. 2, p. CD011425, 17. 20 May.

- S. Lundell, Å. Holmner, B. Rehn, A. Nyberg, and K. Wadell, “Telehealthcare in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis on physical outcomes and dyspnea,” Respir. Med., vol. 109, no. 1, pp. 11–26, Jan. 2015.

- M. Alwashmi, J. M. Alwashmi, J. Hawboldt, E. Davis, C. Marra, J.-M. Gamble, and W. Abu Ashour, “The effect of smartphone interventions on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” JMIR MHealth UHealth, vol. 4, no. 3, p. e105, Sep. 2016.

- S. Jang, Y. S. Jang, Y. Kim, and W.-K. Cho, “A systematic review and meta-analysis of telemonitoring interventions on severe COPD exacerbations,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 18, no. 13, p. 6757, Jun. 2021.

- W. Karlen, “CapnoBase IEEE TBME Respiratory Rate Benchmark.” Borealis, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Puppala et al., “METEOR: An enterprise health informatics environment to support evidence-based medicine,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 62, no. 12, pp. 2776–2786, Dec. 2015.

- G. D. Finlay, M. J. G. D. Finlay, M. J. Rothman, and R. A. Smith, “Measuring the modified early warning score and the Rothman index: advantages of utilizing the electronic medical record in an early warning system,” J. Hosp. Med., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 116–119, Feb. 2014.

- “Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD),” Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Accessed: Jul. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.cprd.

- S. Janjua, E. S. Janjua, E. Banchoff, C. J. Threapleton, S. Prigmore, J. Fletcher, and R. T. Disler, “Digital interventions for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., vol. 4, no. 4, p. CD013246, Apr. 2021.

- M. Zhuang et al., “Effectiveness of digital health interventions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 27, p. e76323, 25. 20 May.

| RQ | P - Patient | I - Intervention | C - Comparator | O - Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1 | Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | Use of wearable biosignals and AI for prediction of exacerbations | Not applicable | Prediction of AECOPD, along with challenges and barriers in implementation or application |

| RQ2 | Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | Digital health interventions | Standard care | Disease management effectiveness, quality of life and medication adherence |

| Code | Focus Area | Research Question | Search Query |

|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1 | Modeling and Prediction | What is known about the use of wearable biosignals and artificial intelligence for predicting COPD exacerbations, and what challenges have been reported in their application? | (COPD OR chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) AND (exacerbation OR acute episode) AND (prediction OR forecasting OR early detection) AND (wearable OR wearable sensor OR wearable device) AND (biosignal OR physiological signal OR vital sign) AND (machine learning OR artificial intelligence OR deep learning) AND (systematic review OR meta-analysis OR review) |

| RQ2 | Intervention | How do digital health interventions affect disease management, quality of life, and medication adherence in COPD patients compared to standard care? | (digital health OR mHealth OR eHealth OR telehealth OR wearable devices OR remote monitoring OR dtx OR digital intervention OR digital therapeutics) AND (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease OR COPD) AND (disease management OR self-management OR quality of life OR medication adherence) AND (effectiveness OR impact OR outcomes) AND (standard care OR usual care OR conventional care) AND (systematic review OR meta-analysis OR review) |

| Inclusion Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Description | Code |

| Scope of Research | Review must focus on COPD exacerbations and address either AI/wearable biosignals for prediction or digital health tools for disease management. | INC_Scope |

| Type of Publication | Only peer-reviewed systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or umbrella reviews are included. | INC_ReviewType |

| Relevance of Technologies | Must assess AI/wearables for COPD prediction or digital interventions for disease management. | INC_TechRelevance |

| Human-Centric Base | Must be based on human studies. | INC_Humanc |

| Scalability | Must address scalable technologies suitable for real-world or clinical use. | INC_Scalability |

| Outcomes Reported | Must report outcomes like prediction accuracy or impacts on management, adherence, or quality of life. | INC_Outcomes |

| Exclusion Criteria | ||

| Criteria | Description | Code |

| Non-relevant Topic | Excluded if not focused on COPD or if lacking AI, wearables, or digital health relevance. | EXC_Scope |

| Non-human Base | Reviews focusing solely on animal or in vitro studies will be excluded. | EXC_Humans |

| Invasive or Non-scalable | Excluded if focused only on invasive or hospital-based tools without scalable alternatives. | EXC_Scalability |

| Publication Type | Excluded if not a systematic review or meta-analysis. | EXC_PubType |

| Publication Period | Excluded if published outside the 2015–2025 range. | EXC_Year |

| Publication Language | Excluded if not published in English. | EXC_Language |

| Peer Review Status | Excluded if not published in a peer-reviewed journal | EXC_PeerReview |

| # | Article | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Q15 | Q16 | Score |

| Assessment of RQ1 eligible studies | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | [17] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | P | N | N | X | X | N | Y | X | Y | Critically Low |

| 2 | [29] | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | P | P | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Low |

| 3 | [30] | N | P | Y | P | Y | N | N | P | N | N | X | X | N | N | X | Y | Critically Low |

| 4 | [31] | N | N | Y | P | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | X | X | N | N | X | Y | Critically Low |

| 5 | [32] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | P | Y | N | X | X | Y | Y | X | Y | Moderate |

| Assessment of RQ2 eligible studies | ||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | [33] | Y | N | Y | P | N | Y | P | P | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low |

| 7 | [19] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Low |

| 8 | [19] | Y | N | Y | P | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Critically Low |

| 9 | [21] | Y | N | Y | P | Y | Y | N | P | Y | N | X | X | Y | Y | X | Y | Critically Low |

| 10 | [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| 11 | [35] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | P | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low |

| 12 | [36] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | P | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low |

| 13 | [37] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | X | X | Y | Y | X | Y | Low |

| 14 | [38] | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | P | N | N | X | X | N | N | X | Y | Critically Low |

| 15 | [19] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | P | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Critically Low |

| 16 | [39] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | Y | P | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low |

| 17 | [40] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | P | P | N | X | X | Y | N | X | Y | Low |

| 18 | [41] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | X | X | N | Y | X | Y | Critically Low |

| 19 | [42] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Critically Low |

| 20 | [43] | Y | N | N | P | Y | Y | N | P | P | N | X | X | Y | N | X | Y | Critically Low |

| 21 | [44] | Y | P | Y | P | Y | N | N | P | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low |

| 22 | [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low |

| 23 | [46] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | P | Y | N | X | X | Y | N | X | Y | Low |

| 24 | [47] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| 25 | [48] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low |

| 26 | [49] | N | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low |

| 27 | [50] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low |

| RQ | # Reviews | N | r | c | CCA Proportion | CCA Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 152 | 135 | 5 | 0.0253 | 2.5% |

| 2 | 22 | 532 | 359 | 23 | 0.0219 | 2.2% |

| Study | Year | Type | # Studies | Population | Dataset | Data Type / Devices | AI Methods & Outcomes | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | 2024 | SR | 51 | COPD frequent exacerbators, age 64–75, 40–45% female | Proprietary: TeleCare North, EDGE, Telescot | Wearables, spirometers, mHealth apps, point-of-care; biosignals (SpO₂, RR, HR, CRP), patient-reported, environmental | Decision trees, RF, SVM, DNN, LSTM, RNN; AUROC ≤0.95, Sens. ≤99.4%, Acc. ≤97.4%. Strong predictive performance for early detection and hospitalization, but mixed real-world impact | No external validation; small sample sizes; inconsistent AECOPD labels |

| [29] | 2024 | SR/MA | 46 | AECOPD, age 60–80, 45–85% male; China (17), Spain (7), US (6), UK (5) | Multi-center hospital-based (ED, ICU, GIMD); no named cohorts | Clinical records, labs, symptom scores | Logistic regression (LASSO, stepwise); some ML (RF, XGBoost); AUC 0.80 (mortality), 0.84 (hospitalization) | 98% models high bias; limited external validation; poor calibration & missing data handling |

| [30] | 2025 | SR | 41 | COPD all severities; age ~60–70, ~65% male (when reported); samples: 16–1000s | Public: Capnobase, METEOR, CPRD, Freesound, Respiratory DB; Proprietary: myCOPD, Re-Admit, DmD, EDGE | Biosignals, lung function, sounds, saliva, PROs, lifestyle/environmental; wearables, apps, sensors | SVM, RF, boosting, CNN, LSTM, GRU; Diagnostic Acc. 80.67–97%, Exacerbation AUROC ≤0.958 | Poor external validation; small datasets; low interpretability; underuse of environmental/lifestyle data |

| [31] | 2016 | SR | 20 | Elderly COPD (frequent exacerbators), small samples (5–169); EU, US, CAN, AUS | Study-specific proprietary data | Symptoms, biosignals, lung function; sensors, e-diaries, oximeters, spirometers | Naïve Bayes, SVM, BNN, KNN, clustering; COPD AUC ≤0.84, Asthma AUC 0.59–0.73; exacerbation prediction 3–5 days ahead | Heterogeneous labels, small samples, no external validation, poor usability |

| [32] | 2017 | SR | 25 | Severe COPD (GOLD II–IV), global; mostly male (>80%) | Public: ECLIPSE, BODE; mostly proprietary | Demographics, spirometry, biomarkers (CRP, IL-6), PROs | Logistic/Cox regression; 1 RF model; AUC 0.58–0.85 (mostly 0.60–0.75) | Weak validation (only 4/27); inconsistent predictors/outcomes; no modern data (wearables, deep learning) |

| Study | Year | Type | Design | P-Population | I-Intervention | C-Comparator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [33] | 2025 | SR/MA | 26 - RCTs | Chronic disease pts / Mostly CVD, diabetes, COPD / Also stroke, asthma, CKD, AIDS, cancer / Mean age: 50s–60s | mHealth via apps: med reminders, disease education (incl. video), symptom tracking, feedback alerts, HCP chat | Usual care: clinic visits, verbal/print education, non-digital adherence support (e.g., brochures, calls) |

| [55] | 2021 | SR/MA | 14 - RCTs | Adults w/ COPD (mild–very severe) / Mean age 65–72 / Mostly male (48–100%) | Digital (single/multi): apps, web, AV tools / Self-monitoring, breathing, education / Some via Skype or hybrid | Usual care: in-person visits, meds, emergencies / Some structured care, no digital tools |

| [19] | 2020 | SR/MA | 13 - RCTs | COPD pts, moderate–severe / Age 57–74 / Balanced gender / Studies in NL, UK, US, China | 18 trials: 11 smartphone apps, 2 tablet-based, 5 w/ wearables (e.g., pedometers, oximeters) | Usual care: visits, meds, PR, verbal/leaflet education / No app or telemonitoring access |

| [21] | 2021 | SR | 13 - RCTs | Adults w/ COPD or asthma / Asthma: age 30–50 / COPD: age 65–75 / Female %: 6.7–76.5% | Telemonitoring, IVR, SMS, web-based platforms / Delivered via phone, web, tablet, robots, email | Usual care: GP/specialist visits, verbal/print education, meds, some face-to-face counseling |

| [34] | 2023 | SR/MA | 130 - RCTs | Adults w/ ≥1 chronic condition / Mean age 61 / 41.6% female / Mostly IHD, HF, diabetes | mHealth (57), eHealth (29), devices (14), combos: mHealth+device (22), eHealth+device (6), all (2) | Usual care: standard management, in-person follow-ups, no digital tools or platforms used |

| [35] | 2024 | SR/MA | 10 - RCTs | COPD pts (FEV1/FVC <70%) / GOLD stage/stable / Age 62–72 / Mostly male / 8 countries | mHealth apps (7–10 studies): rehab w/ exercise modules / myCOPD, WeChat used in 3 studies | Usual PR: in-person, supervised exercise / Mostly hospital-based / No digital tools used |

| [36] | 2024 | SR/MA | 51 - RCTs | Stable COPD / Age 51–83 (mean 60–75) / Mostly male, gender mix varied across studies | 6 types: telemonitoring, apps, web, calls, VR, hybrid / Duration: 12–56 weeks | Usual care: meds, in-clinic follow-up, in-person PR, non-digital education / no tech use |

| [37] | 2024 | SR | 13 - RCTs | Adults with COPD / Severity: mild–very severe / N = 34–409 / Age: 44–75 (mean 60s–70s) / Mostly male | Digital PR: web, apps, video / Exercise (endurance, strength, breathing), education, self-management, motivation | In-person PR: 2–3× weekly sessions / Exercise + education / Usual care: meds + lifestyle advice |

| [38] | 2024 | SR | 35 - RCTs (27), Pilot (1), Feasibility study (3), Cluster-RCTs (1), Non-RCTs (3) |

Adults w/ chronic diseases (e.g., T2DM, CVD, cancer, COPD) / Poor control or recent events | Digital PR: web-based platforms, apps, videoconferencing, structured online PR programs | Standard care: in-person visits, consults, print education, non-interactive tools, passive monitoring |

| [56] | 2025 | SR/MA | 17 - RCTs | Adults 62–74y / Moderate–severe COPD / Multi-morbidity, ↓mobility / N=17–375 / 12 countries incl. USA, China, UK | Digital COPD care: self-mgmt tools (tracking, reminders, coaching, AI alerts), telerehab, remote HCP comms | Usual care: in-person rehab, GP/home visits, no digital tools / Some added non-digital resources |

| [39] | 2024 | SR/MA | 10 - RCTs | Adults w/ moderate–severe COPD / Some w/ frequent exacerbations / Age: 63–71 / No gender data | Telehealth: mHealth, web, tablets / COPD education, PR, symptom+vital monitoring / HCP/peer comms / 3–12 mo | Usual care: clinic follow-up (physicians/nurses) / Printed education: inhaler use, symptom mgmt |

| [40] | 2025 | SR | 13 - 12 RCTs and 1 comparative cohort study | Adults w/ moderate–severe COPD / Stable, post-hospital, or frequent exacerbators / Mean age 67 / 61% male | mHealth: apps (med reminders, symptom/activity tracking, feedback) / SMS (reminders, HCP chat) | Standard care: GP/specialist visits, meds per guidelines, occasional booklets / No digital elements |

| [41] | 2024 | SR | 35 - RCTs | Adults w/ COPD, asthma, or both / COPD: mod–very severe / Some ≥1 exacerbation/year / Mean age: 6–73 yrs | Digital tools: real-time monitoring, teleconsults, e-diaries / Data via Bluetooth / Alerts + auto feedback | Usual care: clinic visits, med reviews, exams / Manual symptom logs / No telemonitoring or digital tools |

| [42] | 2024 | SR/MA | 21 - RCTs | COPD primary focus / Also bronchiectasis, ILD / Ages: mid-50s–70s / Mostly male | Telerehab: video sessions, AI platforms, phone coaching, wearables for real-time exercise feedback | Usual PR: in-clinic aerobic, resistance, breathing exercises + education / Hospital or outpatient settings |

| [43] | 2023 | SR | 32 - RCTs (23), quasi-experimental (4), observational/cohort (4), qualitative (1) | Adults with stable COPD / No severity limits / Mostly >40 yrs / Mixed gender | Mobile apps, SMS, phone monitoring, web portals, tablet PR apps for COPD management | Usual meds only / Waitlist controls / Some single-arm studies focused on feasibility or adherence |

| [44] | 2022 | SR/MA | 22 - RCTs | COPD pts >40 / Mild–mod severity / 59% male / Mean age 62–75 / Studies: 11 countries | Telerehab: async (wearables, apps, web) + sync (live video PR) / Remote clinician monitoring | Usual care or wait-list / No structured rehab / Only standard clinical follow-up, no exercise training |

| [45] | 2023 | SR/MA | 6 - RCTs | Adults w/ COPD / Mostly moderate–very severe / 3 studies unstated severity / Mean age: 62.7–73.5 / Mostly male | Web-based self-mgmt via portals, apps, WeChat, EHR tools, web call centers | Usual care: clinic visits, meds, verbal advice / 2 studies: print/face-to-face education, no interactivity |

| [46] | 2017 | SR | 8 - RCTs (5), non-RCTs (3) | Adults with mild–moderate COPD / Mean age: 62–72 / 65–100% male | Smartphone-based PA tools: step count, visual feedback, texts / PA promo or exercise training | Usual care: standard COPD tx / Verbal advice to walk more / No structured PA or behavior support |

| [47] | 2017 | SR/MA | 3 - RCTs | Adults w/ COPD / Severity not reported / Mean age: 67 (Moy), 66 (Tabak), 58 (Voncken-Brewster) | Moy: 12-mo web walking prog / Pedometer, dashboard, goals, peer forum / Step uploads weekly | Moy: Pedometer only, no goals/feedback / Tabak: PR, no app / VB: Nurse coaching, no tech |

| [48] | 2015 | SR/MA | 9 - RCTs | Moderate–severe COPD / Mean age: 64–73 / 34% women / Sites: NA, Europe, Asia | Home-based: phone calls (edu, motivation), web (symptom reporting, tailored edu, live chat) | Usual care or brief education / Home exercise w/ print guides / No digital reinforcement |

| [49] | 2016 | SR/MA | 6 - RCTs (5), quasi-randomized controlled trial (1) | Adults w/ moderate–severe COPD / Some w/ full COPD spectrum / Mean age: 70 / 74% male | Smartphone-based COPD self-management: symptom + physio tracking, exercise programs, progress feedback | Routine care: meds, follow-up visits, education/training, pt-initiated contact during symptom worsening |

| [50] | 2021 | SR/MA | 22 - RCTs | Adults w/ severe COPD / Some on home O2 / Mean age 63–81 / Male: 30–70% | Telemonitoring via web portals, mobile/tablet/PDA devices, some w/ video conferencing | Usual care: clinical follow-up, guideline-based meds, emergency access, no telemonitoring |

| Study | O-Outocomes | Heterogeneity | Limitations |

| [33] | Med adherence ↑ (OR 2.37; SMD 0.28) via self-report (MMAS-8, MAQ, Voils, MG) and electronic tracking; no QoL data; symptoms tracking limited; ↑ effect w/ advanced reminders, interactivity, data sharing, dispensers | I² = 0–85% / ↑ in self-report tools / ↓ w/ interactive features / Random-effects model | Heterogeneity / Reporting gaps / High–unclear bias / Low quality / Publication bias |

| [55] | 6MWD ↑ (MD = 54.33m) / QoL ↑ (SGRQ −26.57, CAT/EQ-5D ~) / Self-efficacy ~ / CRQ-dyspnoea ↑ (MD = 0.64) / Exacerbation, admission ~ / Satisfaction mixed / Adherence ✗ | I² = 0–87% / ↑ in 6MWD (87%) / QoL varied / Low in dyspnoea, self-efficacy / Some not pooled | Heterogeneity / Reporting gaps / High–unclear bias / Unclear methods / Low quality / Small samples |

| [19] | Exacerbations & hospitalizations ~ (low certainty); QoL mostly sub-MID; SF-12 PCS ↑ (+9.2); 6MWT, anxiety, fatigue, depression, dyspnoea ~; Adherence ✗; Physical activity ↑ (+9.5 min/day, 1 study); QoL meta-analysis: SMD −0.4 (ns); Certainty low–very low | I² = 52–83% / ↑ QoL heterogeneity (I² = 83%) / No Q stats, subgroups, or publication bias tests | Heterogeneity / Reporting gaps / Unclear methods / Low quality / Small samples / Publication bias |

| [21] | Med adherence ↑ (13–49%) via self-report (MARS, Morisky), pill count, pharmacy, e-tracking; ~50% studies sig. (p .04–<.001); strongest in COPD/asthma inhaler use; QoL inconsistent, no standard tools; disease mgmt indirect | No meta-analysis / Heterogeneity high due to study design, adherence definitions, reporting, delivery variation | Small samples / Heterogeneity / Low study quality |

| [34] | Physical activity ↑ (SMD 0.29; +971 steps/day) / QoL ↑ modestly (SMD 0.18), not sustained / Effects ↓ at follow-up / Adherence ✗ / Self-care referenced, not quantified / Certainty low (bias, heterogeneity) | I² = 54–84% / ↑ in 6MWT, QoL, subjective PA / ↓ effects w/ age, BMI / Much unexplained | Heterogeneity / Reporting gaps / High–unclear bias / Low quality / Publication bias |

| [35] | Exacerbations, hospitalizations ↓ (mixed sig.) / QoL ↑ (CAT −1.29, p = .02) / SGRQ, EQ-5D ~ / Adherence underreported / ↑ PA (~462 steps/day), inhaler use, self-care / Dyspnea ~ / Mixed but favorable overall | Low I² across 6MWD, CAT, mMRC, SGRQ, hospitalizations / Funnel plot ✓ / Subgroup by severity, intervention type | Small sample sizes / Some heterogeneity |

| [36] | 6MWT ↑: Telemonitoring (+43.03m), App (+25.74m), VR (+18.43m), Combined (+25.67m); QoL ↑: App (SMD −0.47), Web (−1.49, SUCRA 94.3%), VR (−0.47); adherence ✗; eHealth ↑ self-management, engagement, ↓ readmissions | I² = 12–97.8% / ↑ in Web, Combined, Telemonitoring / No inconsistency (p > .65) / Sensitivity ✓ | Heterogeneity / Reporting gaps / High–unclear bias / Low quality |

| [37] | Digital PR ↑ 6MWT, 12MWT, ESWT, steps/day (p < .001); QoL ↑ (SGRQ, CAT, CRQ, SF-36); exacerbations, ED visits, hospitalizations ↓; dyspnoea ↓ (mMRC); self-efficacy ↑ (PRAISE, GSES); anxiety/depression ~ (HADS); adherence ✗ | Meta-analysis ✗ / Clinical-methodological heterogeneity / Variability in design, tools, duration, comparators, participants | Heterogeneity / Small samples / High–unclear bias / Low study quality |

| [38] | mHealth → ↓ HbA1c (−0.30% to −1.95%), BP ↓ in CVD/T2DM, COPD ER visits ↓, readmissions ↓; QoL ↑ (SF-36, EQ-5D), mixed in COPD/T2DM; adherence ↑; benefits in self-monitoring, knowledge, engagement, satisfaction | Moderate heterogeneity in HbA1c / COPD variability / Influenced by design, duration, delivery, digital literacy / Sensitivity analyses ✓ | Reporting issues / Heterogeneity |

| [56] | QoL ↑ (CAT −2.53; SGRQ ↑; EQ-5D ↑) / Self-efficacy ↑ (3–6 mo) / Dyspnea ↓ (mMRC −0.23) / 6MWT ~ / Admissions ~ / Adherence not measured / Benefits: education, symptom monitoring, self-care ↑ / No effect on acute outcomes or endurance | I² = 0–94% / Low for CAT, mMRC, admissions / High for SGRQ, EQ-5D, QoL, 6MWT / Attributed to intervention, comparator, and design variation / No subgroup analyses | Reporting issues / Small samples / Heterogeneity / Low study quality |

| [39] | QoL ↑ in 9/10 studies (SGRQ, EQ-5D, CAT, CRQ, CCQ, 15D); 1 study ~; self-management ↑ w/ education/behavioral features; adherence not assessed but supported via reminders, education | I² = 70% / χ² = 30.26 / Tau² = 0.08 / No subgroups / Variation in interventions, QoL tools, populations | Heterogeneity / Unclear methods / Low study quality |

| [40] | Adherence ↑ w/ interactivity (e.g., reminders); QoL ↑ (CRQ +12.4, SGRQ ↓ decline); readmissions ↓ (13.7% vs. 29.1%); PA ↑ (ISWT +51m); lung function ~; adherence mostly inferred; education ↑ self-care | High clinical/methodological heterogeneity / Not quantified / Due to sample size, intervention types, outcome tools | Heterogeneity / Small samples / High–unclear bias |

| [41] | Cost-effectiveness ↑ (ICER €3.5k–€286k/QALY); costs ↓ w/ ~QALYs; QoL (EQ-5D, CAT, SGRQ) mixed; Adherence ↑ w/ reminders or monitoring; Disease mgmt ↑ (↓ admissions, ↑ self-care); PA & lung function ~ | High heterogeneity / No I² or Q / Variation in DHI types, populations, methods, settings, evaluation models | Heterogeneity / Reporting gaps / High–unclear bias / Unclear methods / Low study quality |

| [42] | Telerehab ↑ short-term 6MWD (MD 7.52m), ↓ dyspnea (mMRC), QoL ↑ (CAT, SGRQ short-term), HADS ↓ anxiety/depression short-term only; FEV1 ~; self-management ↑ (inferred); no direct behavior/adherence metrics | I² = 0–56% / ↓ in SGRQ, HADS / ↑ in CAT / Subgroup: follow-up duration / Intervention, outcome, and population variability / Publication bias (6MWD, Egger’s p = .019) adjusted | Reporting issues / Heterogeneity |

| [43] | COPD outcomes ↑: ↓ exacerbations, hospital/ER visits; QoL ↑ (SGRQ, CAT, CRQ, EQ-5D); adherence ↑ via reminders, diaries, inhaler monitors; ↑ self-care, 6MWT, FEV₁; mobile/web/tablet tools effective | Substantial heterogeneity in interventions, populations, outcomes, methods / Not quantified / Narrative synthesis used | Reporting issues / Heterogeneity / Low study quality |

| [44] | TR vs no intervention: ↑ functional capacity (SMD 0.29), dyspnea (0.76), QoL (0.57); asynchronous TR ↑ vs NI (g 0.39–0.82); smaller or ~ effects vs center-based care; outcomes assessed via walk tests, CAT/SGRQ/CRQ, dyspnea scales, psychosocial tools; med adherence ✗ | Substantial heterogeneity in interventions, populations, outcomes, methods / Not quantified / Narrative synthesis only | Reporting issues / Heterogeneity / Low study quality |

| [45] | Pulmonary function: FEV1 ↑ (ns), FEV1 L ↑ (ns), FEV1/FVC ↑ (ns), FVC ↑ (1 study), FVC% ~; QoL, adherence ✗; interventions sometimes included self-monitoring, exercise, provider contact | I² reported / Random-effects model used / Heterogeneity from platform, COPD severity, setting, duration, quality | Reporting issues / High–unclear bias / Unclear methods / Low study quality |

| [46] | PA: mixed effects (↑13% or ↓2.5%) via smartphone sensors; ISWT ↑ (21%, 18.3%) or ~; QoL ~; No adherence data; Smartphone use ✓ (89–100%), some tech-related dropouts; PA correlated w/ use (r = 0.62) | No I²/Q reported / Substantial clinical-methodological heterogeneity / No subgroup/sensitivity analyses | Reporting gaps / Small samples / High–unclear bias / Low study quality |

| [47] | HRQoL ↑ short-term (SGRQ, CCQ; SMD –0.22); PA ↑ (MD +864 steps); no 12-month effect; hospitalizations, AECOPD, smoking cessation ~; med adherence ✗ | I² = 0% / p > .60 / No subgroup analyses / ↓ steps w/ age (–33/yr, p = .03) / Random-effects | Small sample size / High–unclear risk of bias |

| [48] | Physical activity ↑ (MD 64.7 min/week); 6MWT ~ (MD −1.3m); Dyspnea ~ (SMD 0.088); no sig. QoL or adherence data; assessed via accelerometers, self-reports, validated dyspnea tools; no publication bias | I² = 0–85% / ↓ after outlier removal / Mixed models used (I² > 30%: random, ≤ 30%: fixed) | Heterogeneity / Reporting issues / Small samples / High–unclear risk of bias |

| [49] | Exacerbation ↓ (OR 0.20, 95% CI: 0.07–0.62) / I² = 59% / QoL, adherence ✗ / Daily symptom tracking ✓ (low certainty) / Usability, satisfaction inconsistent / No pooled data for admissions or ER visits | I² = 59% / χ² = 4.9 (p = 0.08) / Moderate heterogeneity not statistically significant | Heterogeneity / Unclear methods / Low quality / Publication bias / Small samples |

| [50] | Telemonitoring: Hosp. adm ~ (SMD –0.10); ER visits ↓ (SMD –0.14); QoL mixed (SGRQ ↑, EQ-5D/SF-36 ~); Time to adm ~; Adherence ✗; Self-mgmt ↑ in some; Satisfaction ✓; Cost ↓ (∼50%); Mortality ~; Mental health effects mixed | I²: hosp. adm = 24%, ER = 18% / Fixed-effects model / Clinical variation noted / No subgroup analyses | Reporting issues / Heterogeneity / Low study quality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).