Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Contributions of This Paper

- We give an in-depth review on existing ML-based NIDS attack and defense techniques, including a detailed overview of NIDS, its types, ML techniques, commonly used datasets in NIDS, attacker models, and possible detection methods.

- The types of the powerful attack and defense techniques and the most realistic datasets in NIDS are carefully classified.

- Existing attack and defensive approaches on adversarial learning in the NIDS are analyzed and evaluated.

- We identify the real current challenges in detection and defensive techniques that need to be further investigated and remedied in order to produce more robust NIDS models and realistic datasets. Revealing current challenges guides us to provide insights about future research directions in the area of detecting AAs in ML-based NIDS. This has been explored in detail in the discussion section, highlighting our findings in revealing the limitations of current existing approaches.

- A comprehensive analysis has been conducted to show the impact of adversarial breaches on ML-based NIDS, including black-, gray-, and white-box attacks.

2. Background

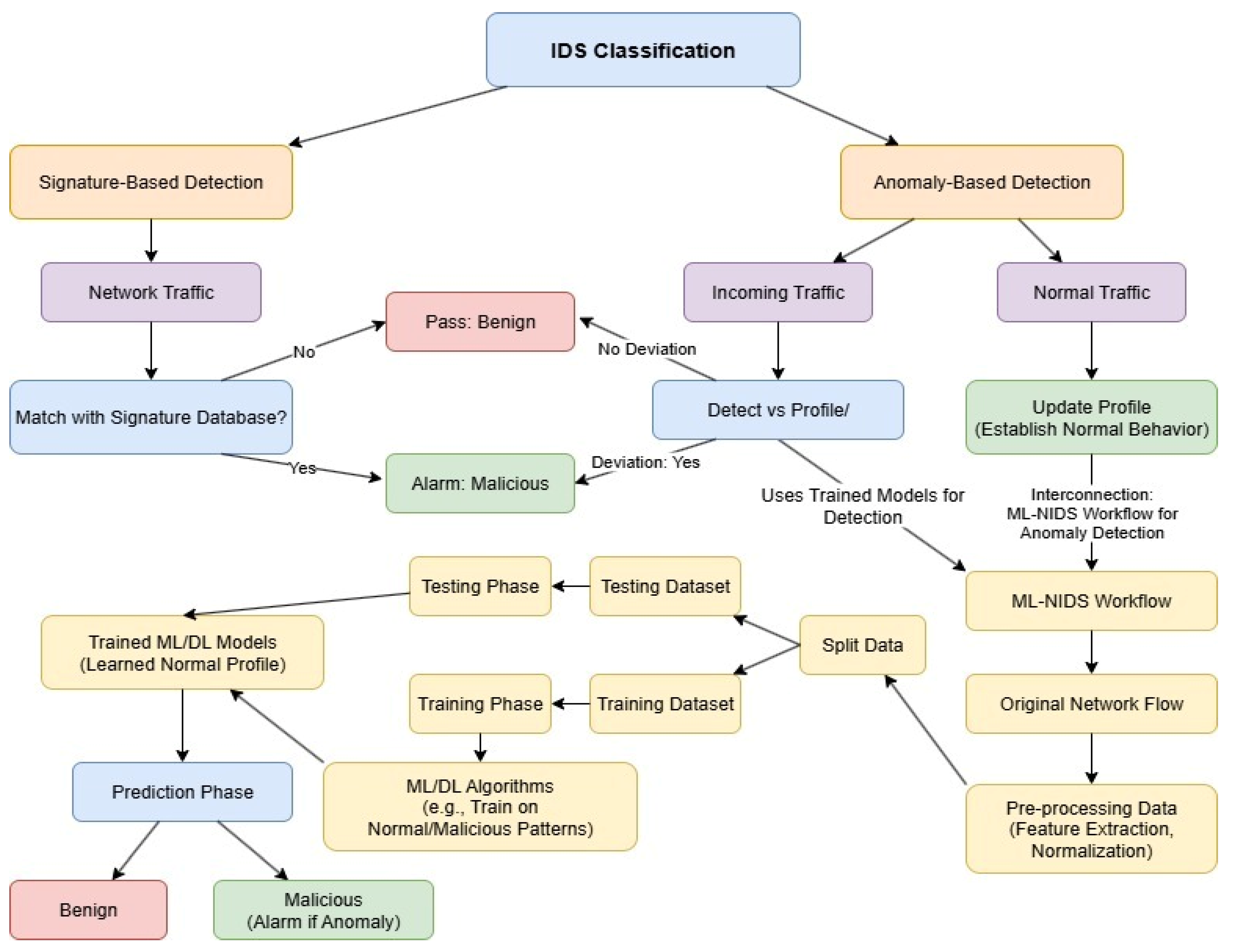

2.1. ML Techniques in NIDS

2.2. Adversarial Machine Learning (AML)

2.2.1. Knowledge

- Black box attack: no information about the parameters or the classifier’s structure is required for the malicious agents. They should be able to access the input and the output of the models, and the rest is considered as black-box.

- Gray box attack: limited information or access to the system should be known to an attacker, such as accessing the preparation of the dataset and the predicated labels (training dataset), or applied a limited number of queries to the model.

- White box attack: In this type, it has been assumed that the attacker has completely knowledge and in-formation about the classifier and the used hyperparameters.

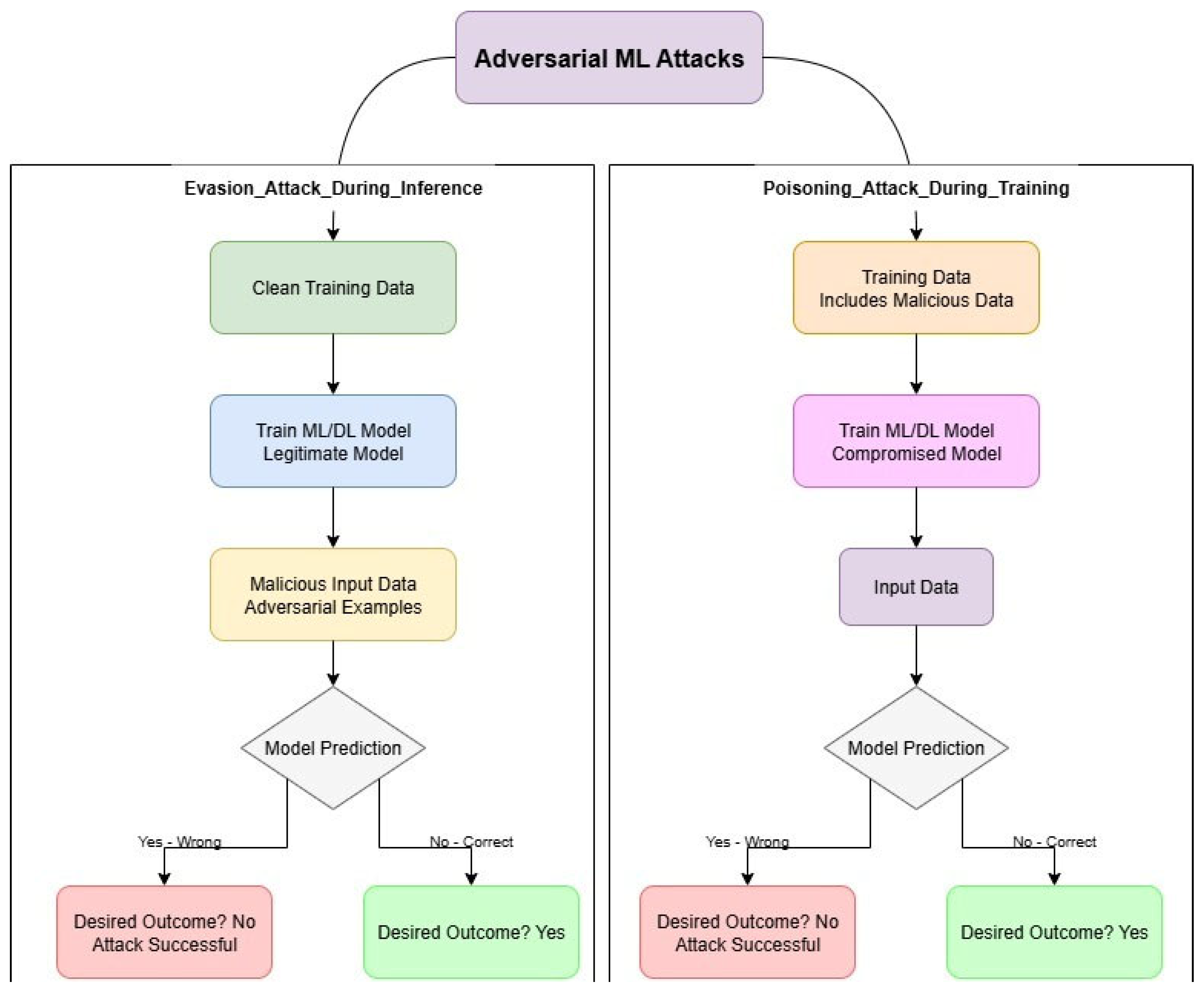

2.2.2. Timing

- Evasion Attack: The attack can be employed during the testing phase, where an attacker attempts to force the ML model to classify the observations wrongly. In the context of network-based IDS, the attacker tries to prevent the detection system from detecting malicious or unusual events, and therefore, the NIDS wrongly classifies the behavior as benign. To be more specific, four scenarios might occur, as follows: (1) Confidence reduction, which reduces the certainty score to cause wrongly classification, (2) Misclassification, in which the attacker modifies the result to produce a class not similar to the first class; (3) Intended wrong prediction, in which the malicious agent generates an instance that fools the model into classifying the behave as an objective or incorrect class, and (4) source or target Misclassification, in which the adversary changes the result class of a certain attack example to a particular target class [35].

- Poisoning attack: It occurs during the training phase, in which an assaulter tampers with the model or the training data to yield inaccurate predictions. Poisoning attacks mainly involve data insertions or injections, logic corruption, and data poisoning or manipulation. Data insertion or injection occurs when an assailant inserts hostile or harmful data inputs into the original data without changing its characteristics and labels. The phrase "data manipulation" refers to an adversary adjusting the original training data to compromise the ML model. Logic corruption refers to an adversary’s attempt to modify the internal model structure, decision making logic, or hyperparameters, to malfunction the ML [29].

2.2.3. Goals

2.2.4. Capability

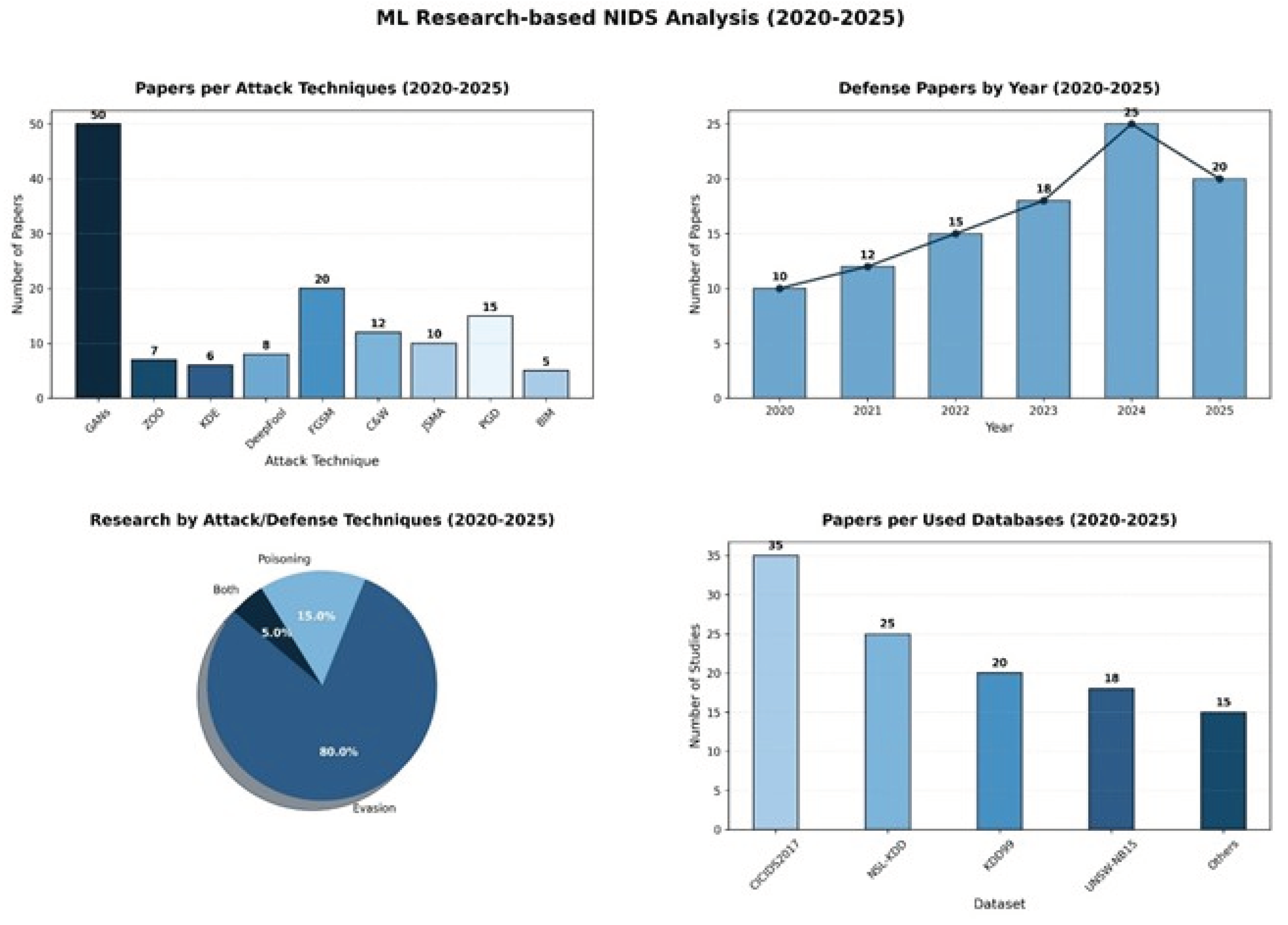

2.3. Adversarial Attacks Based on Machine Learning

2.3.1. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

2.3.2. Zeroth-Order Optimization (ZOO)

2.3.3. Kernel Density Estimation (KDE)

2.3.4. DeepFool

2.3.5. Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM)

2.3.6. The Carlini and Wagner (C&W) Attack

2.3.7. The Jacobian-based Saliency Map Attack (JSMA)

2.3.8. Projected Gradient Descent (PGD)

2.3.9. Basic Iteration Method (BIM)

3. Datasets used in NIDS

3.1. Type of Used Datasets

- NSL-KDD dataset: it represents the updated KDDCup 99 dataset implemented to solve the problems of the data imbalance and irrelevant records between abnormal and normal samples. It does have 41 features: 13 for content connection features, 9 for temporal features (found during the two-second time window), 9 for individual TCP connection features, and 10 for other general features [63].

- UNSW-NB15 dataset: It has been generated in 2015 by the cybersecurity research group at the Australian Centre of Cyber Security (ACCS). This dataset includes about data with 100 GB size, including both malicious and normal traffic records, where each sample has 49 features created by using many feature extraction techniques. It is mainly partitioned into test and training sets, involving, respectively, 82.332 and 175.341 instances [64].

- BoT-IoT dataset: It has been presented at the UNSW Canberra Cyber Center by the Cyber Range Lab. This dataset has been generated from a physical network incorporating botnet and normal samples from traffic. It consists the serious attacks, as follows:

- Kyoto 2006+ dataset: It was established and revealed by Song et al. [66]. It is a collection of real traffic coming from 32 honeypots with various features from almost three years (Nov 2006 to Aug 2009), including a total of over 93 million samples [67]. Then, it has been expanded by adding more honeypots, for nine years of traffic (to 2015), to include DNS servers for creating benign traffic records. Each of these records has 24 features captured from network traffic flows, 14 of them are represented as KDD or DARPA, while the rest are added as new features.

- CIC dataset: It has been generated to assess the NIDS performance and train the models further. The first generation of these datasets was CICIDS2017. It was collected from a synthetic network traffic for 5 days, available on request (is protected). The collected data are in flow and packet formats with 80 different features [4,20].

- CSE-CIC-IDS2018 dataset: The Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC) and Communications Security Establishment (CSE) have implemented this on AWS (Amazon Web Services), based in Fredericton [68]. It represents the extended CIC-IDS2017 and was collected to reflect real cyber threats, including eighty features, network traffic, and system logs [69,70]. The network’s infrastructure contains 50 attacking computers, 420 compromised machines, and 30 servers.

- The ADFA-LD dataset: It has been generated via the Australian Defence Force Academy (ADFA) at the New South Wales University, the Australian Centre for Cyber Security (ACCS). It was derived from the host-based IDSs and includes samples recorded from two operating systems. Many important attacks in this dataset have been collected from zero-day and malware-based attacks [73].

- KDD CUP 99 dataset: It has been produced in 1998 via the processing of the tcpdump segment of DARPA. It contains a total of 23 attacks with 41 features and an additional one, the 42nd feature, employed to divide the connection as either normal or attack [74].

- CTU-13 dataset: it is a synthetic dataset that concentrates mainly on botnet network traffic and contains a wide range of dataset analyses for anomaly detection on critical infrastructures, covering 153 attack types, including port scanning and DDoS. The dataset has 30 samples. In each one, a different botnet malware is executed in a controlled environment. This dataset was originally presented in two formats: a full Pcap of normal and malicious packets and a labelled bidirectional Netflow [75]. Table 3 illustrates the advantages and disadvantages of commonly used datasets in NIDS, highlighting strengths, limitations, and supporting references to evaluate the adversarial contexts.

3.2. Data Preparation

- A.

-

Data Preprocessing: It involves the following:

-

Handle missing values:

- o

- Remove rows and/or columns with many missing values.

- o

- Assign with median and / or mean (for numerical features).

- o

- Constant value or use mode (for classifying features).

- o

- Remove irrelevant data: Remove unnecessary columns, e.g., timestamps if not relevant.

- Eliminates duplication: Remove duplicated rows to prevent redundancy.

-

- B.

-

Data Transformation

- Log transformation: Apply to skewed numerical features to make them more normal-like.

- Binary features: Convert certain columns, e.g., flags, attack types, into binary 0/1 variables for classification tasks.

- C.

-

Handling Anomalies

- Noise filtering: Remove improbable or corrupt data points, e.g., negative packet sizes.

- Outlier detection: Identify and handle anomalies using z-scores, IQR, or isolation forest methods.

- D.

-

Aggregation

- Combine related features: Create summary statistics for network flows, e.g., total packets, average duration.

- Group traffic data by sessions or flows for better contextual understanding.

- E.

-

Standardize Data Format

-

Ensure all datasets share a consistent:

- o

- Column naming convention.

- o

- Labeling scheme, e.g., "Normal" vs. "Anomaly".

- Value format (e.g., "Yes"/"No" vs. 1/0).

-

- F.

-

Encoding Target Variable

- Binary classification: Encode the target as 0 (Normal) and 1 (Attack).

- Multi-class classification: Use integers or one-hot encoding for different attack types.

- G.

-

Splitting and Balancing

- Split into train/test/validation sets: Ensure realistic distributions in training and testing splits.

- Balance classes: Use oversampling, e.g., SMOTE, or undersampling to address class imbalance.

- H.

-

Data Type Conversion

- Convert all columns to appropriate data types (e.g., float, int, or category) for computational efficiency and modeling compatibility.

- I.

-

Dimensionality Reduction

- Incorporate t-SNE or PCA to decrease dimensionality while keeping patterns, especially for datasets with many features.

- J.

-

Feature Engineering

- Encode categorical variables: Discrete columns can be transformed leveraging the label and one-hot encoding, or ordinal encoding.

- Normalize numeric features: Use Standardization or the Min-Max technique for numeric values to ensure comparability.

- Extract temporal features: From timestamp columns, derive features like hour, day of the week, or duration.

- Feature selection: Use correlation analysis or feature importance metrics, e.g., mutual information, tree-based models, to retain only the most relevant features.

3.3. Feature Reduction

- Principal component analysis (PCA): It is leveraged to obtain valuable features in which the feature’s dimensions are decreased. This will reduce both the model’s computational time and complexity. The preferable features are extracted by this technique to reduce the search range [26]. In cybersecurity, PCA is used to obtain valuable features from the traffic network [39].

- Recursive feature elimination (Rfe): This one can be employed to choose preferable features from the entire ones in the given input data, where high ranks of features have only been chosen, while the ones with low ranks are deleted. This approach is used to eliminate redundant features and retrieve important and preferable features. The main aim of incorporating Rfe is to select the most possible sets of significant features [11].

- The stacked sparse autoencoder (SSAE): It is one of the deep learning models that is used to select features with high rank behavior and activity data. The classification features have been presented into SSAE for the first time to automatically extract the deep sparse features. The sparse features with low dimensions have been employed to implement various fundamental classifiers. The SSAE was compared with other feature selection approaches presented by prior studies. The experiments have been conducted using multiclass and binary classifications, and the results ensure the following:

- Sparse features with high dimensions extracted via SSAE are more effective in identifying intrusion behaviors than prior approaches.

- Sparse features with high dimensions significantly accelerate the classification of the basic classifiers. To sum up with it has been emphasized that the SSAE offers a new research direction approach to spot intrusion and has been considered as one of the most promising approaches for extracting valuable features [76].

- Auto-encoder (AE): AE is an unsupervised feature learning method used to classify both anomaly detection in network and malware. In fact, using deep AE, the original input is transformed into an improved representation through hierarchical feature learning, in which each corresponding level captures into a different degree of complexity. A linear activation function in all units of an AE captures a subspace of the basic parts of the input. Moreover, it is anticipated that incorporating non-linear activation functions with AE can help to detect more valuable features. Given the same number of parameters, AE can achieve better performance compared to a shallow AE [54,76,77].

- Stacked Non-Symmetrical Deep Autoencoder (SNDAE): It uses the novel NDAE (Nonlinear Deep Autoencoder) approach in an unsupervised learning for obtaining valuable features. A classification model built from stacked NDAEs has shown to offer great outcomes in feature reduction when the RF algorithm was used with two datasets: NSL-KDD and KDD Cup ’99 [54].

3.4. Feature Extraction

- 1.

- Feature Extraction based on Flow: this technique is the most common used one, where details from network packets in the same connection and flow are extracted. Every extracted feature refers to the main connection between two given devices. The extracted features in this method are mainly obtained from the header of the network packet and can be classified into three steps, as follows:

- Aggregate information can be used to compute the number of specific packet features in the connection, like how many bytes have been sent, the number of flags used, and packets transferred.

- Summary statistics give the entire information in detail regarding the whole connection, including the used protocol/service and the duration of the connection.

- Statistical information is used to evaluate statistics of the packet features in the network connection, e.g., the mean and the standard deviation of interarrival time and packet size of the network. Besides the statistical features, more information and sensitive data could be collected from external tools and software, e.g., system API calls (number of shell prompts), and malware detection engine [66,79]. These characteristics can be used to show the behavior of the internal devices and the network devices in detail. It is worth mentioning that since the system API calls are various among devices, replicating and setting up the external tools and software can be challenging. Therefore, external features cannot be used for general networks, but they are applicable in certain network configurations.

- 2.

- Feature Extraction based on Packet: This is another feature extraction technique that can be used to obtain a specific feature at the packet level, rather than at the connection or flow. Usually, features based on packet are statistically aggregated data same to the features flow, but with extra correlation analysis between the inter-packet time and the size of the packet across two devices. The features can be extracted using different time windows to minimize the traffic variations and capture the sequential data of the packets. The packet-based feature extraction techniques can be employed in different detection systems [80,81]. Note that this extraction method is effective for examining the header information of the packet in order to further allow optimal feature extraction.

4. Adversarial Attack against ML-based NIDS Models

4.1. Black Box Attack

4.1.1. Poisoning

4.1.2. Evasion

4.2. White Box Attack

4.2.1. Poisoning

4.2.2. Evasion

4.3. Gray Box Attack

4.3.1. Poisoning

4.3.2. Evasion

4.4. Combination of Poisoning and Evasion

5. Defending ML-based NIDS Models

5.1. Black Box Attack

5.1.1. Poisoning

5.1.2. Evasion

5.2. White Box Attack

5.2.1. Poisoning

5.2.2. Evasion

5.3. Gray Box Attack

5.3.1. Poisoning

5.3.2. Evasion

5.4. Combination of Poisoning and Evasion

6. Discussion

- There is no defensive technique, including NIDS or hybrid ML with NIDS, that has been presented yet that can provide a very high attack detection rate against strong attacks, such as GAN, DeepFool, and KDE. In [44], extensive experiments have been conducted, and it has been pointed out that no defensive approaches were able to prevent sophisticated attacks generated via incorporating different datasets with different percentage rates of attacks.

- Although GANs have been shown to be the most promising and powerful attacks, the recent study in [44] confirmed that other attack models, e.g., DeepFools, can be stronger than GANs if they have been trained carefully.

- The implementation of adversarial attacks has been extensively leveraged and explored in deep detail in both image and speech processing areas. However, their impacts on NIDS remain to be explored. Creating adversarial examples in the real-time domain from network traffic in the physical layer has not been proposed or presented yet. This one is especially important to open the door for future interesting research areas.

- Many ML-based NIDS can detect attacks very accurately, but this usually makes them slower and more resource-intensive to run. On the other hand, simpler detection systems can work faster and cheaper by removing less critical features. While this approach makes the system more efficient, it does cause a small drop in accuracy [167].

- Current defensive techniques typically address evasion or poisoning attacks separately, leaving models subject to combined threats. Our analysis shows that very few techniques can effectively mitigate both attacks at once. To close this gap, researchers should develop strong unified defenses to prevent both attack types, and this, in turn, makes the detection systems safer against real-world adversarial approaches.

- Unified defenses for evasion+poisoning, per the 2025 NIST taxonomy, which defines terminology for attacks across ML lifecycles [10].

- Bridge academic-real-world gaps with physical-layer attacks, informed by 2025 reviews on NIDS-specific adversarial impacts [14].

7. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Ahmad et al., "Novel approach using deep learning for intrusion detection and classification of the network traffic", IEEE CIVEMSA, 2020.

- Alasad; et al. , "Resilient and secure hardware devices using ASL," ACM JETC, vol. 17, no. 2, 2021.

- Q. Alasad, J.-S. Yuan, and P. Subramanyan," Strong logic obfuscation with low overhead against IC reverse engineering attacks," ACM TODAES, vol. 25, no. 4, 2020.

- M. J. Hashemi and E. Keller "Enhancing robustness against adversarial examples in network intrusion detection systems," IEEE NFV-SDN, 2020.

- S. Alahmed et al.," Mitigation of black-box attacks on intrusion detection systems-based ML, Computers," vol. 11, no. 7, 2022.

- N. Aboueata et al., "Supervised machine learning techniques for efficient network intrusion detection," IEEE ICCCN, 2019.

- Kumari and A., K. Mehta, "A hybrid intrusion detection system based on decision tree and support vector machine,"IEEE ICCCA, 2020.

- G. Sah and S. Banerjee, Feature reduction and classification techniques for intrusion detection system, IEEE ICCSP, 2020.

- B. M. Serinelli, A. Collen, and N. A. Nijdam, "Training guidance with kdd cup 1999 and nsl-kdd data sets of anidinr: Anomaly-based network intrusion detection system," Procedia Computer Science, vol. 175, pp. 560-565, 2020.

- Vassilev; et al. , "Adversarial machine learning: A taxonomy and terminology of attacks and mitigations," NIST Trustworthy and Responsible AI Report, NIST AI 100-2e2025.

- M. Usama et al., "Generative adversarial networks for launching and thwarting adversarial attacks on network intrusion detection systems," IEEE IWCMC, 2019.

- Chen; et al. , "Fooling intrusion detection systems using adversarially autoencoder," Digit. Commun. Netw., vol. 7, no. 3, 2021.

- H. A. Alatwi and A. Aldweesh, "Adversarial black-box attacks against network intrusion detection systems: A survey," in 2021 IEEE World AI IoT Congress (AIIoT), 2021: IEEE, pp. 0034-0040.

- M. Hasan et al., "Adversarial attacks on deep learning-based network intrusion detection systems: A taxonomy and review," SSRN 5096420, 2025.

- Alqahtani and, H. AlShaher, "Anomaly-Based Intrusion Detection Systems Using Machine Learning," Journal of Cybersecurity & Information Management, vol. 14, no. 1, 2024.

- H. A. Alatwi and C. A: Morisset, "Adversarial machine learning in network intrusion detection domain; arXiv:2112.03315, 2021.

- H. Abdulganiyu, T. A. Tchakoucht, and Y. K. Saheed, RETRACTED ARTICLE: Towards an efficient model for network intrusion detection system (IDS): systematic literature review, Wireless Netw., vol. 30, no. 1, 2024.

- Yogesh and L., M. Goyal, RETRACTED ARTICLE: Deep learning based network intrusion detection system: a systematic literature review and future scopes, Int. J. Inf. Secur., vol. 23, no. 6, 2024.

- A. Rawal, D. Rawat, and B. M. Sadler, "Recent advances in adversarial machine learning: status, challenges and perspectives, "AI & ML for Multi-Domain Ops Apps III, vol. 11746, 2021.

- Z. Ahmad et al.," Network intrusion detection system: A systematic study of machine learning and deep learning approaches," Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Techn., vol. 32, no. 1, 2021.

- M. Ozkan-Okay; et al. ," A comprehensive systematic literature review on intrusion detection systems," IEEE Access, vol. 9, 2021.

- I. Rosenberg; et al. , "Adversarial machine learning attacks and defense methods in the cyber security domain," ACM CSUR, vol. 54, no. 5, 2021.

- H. Jmila and M. I. Khedher, "Adversarial machine learning for network intrusion detection: A comparative study," Computer Networks, vol. 214, p. 109073, 2022.

- H. Khazane et al., "A holistic review of machine learning adversarial attacks in IoT networks," Future Internet, vol. 16, no. 1, 2024.

- Alotaibi and M., A. Rassam, "Adversarial machine learning attacks against intrusion detection systems: A survey on strategies and defense," Future Internet, vol. 15, no. 2, p. 62, 2023.

- W. Lim et al., "Future of generative adversarial networks (GAN) for anomaly detection in network security: A review," Comput. Secur., vol. 139, 2024.

- Y. Pacheco and W. Sun, "Adversarial Machine Learning: A Comparative Study on Contemporary Intrusion Detection Datasets," in ICISSP, 2021, pp. 160-171.

- K. He, D. D. Kim, and M. R. Asghar, "Adversarial machine learning for network intrusion detection systems: A comprehensive survey," IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 538-566, 2023.

- O. Ibitoye, R. Abou-Khamis, M. e. Shehaby, A. Matrawy, and M. O. Shafiq, "The Threat of Adversarial Attacks on Machine Learning in Network Security--A Survey," arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.02621, 2019.

- Q. Liu et al.," A survey on security threats and defensive techniques of machine learning: A data driven view," IEEE Access, vol. 6, 2018.

- Y. Peng et al.," Detecting adversarial examples for network intrusion detection system with GAN," IEEE ICSESS, 2020.

- G. Apruzzese et al., "Addressing adversarial attacks against security systems based on machine learning, "IEEE CyCon, vol. 900, 2019.

- G. Apruzzese et al.," Modeling realistic adversarial attacks against network intrusion detection systems," DTRAP, vol. 3, no. 3, 2022.

- E. Alhajjar, P. Maxwell, and N. Bastian, "Adversarial machine learning in network intrusion detection systems," Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 186, p. 115782, 2021.

- M. A. Ayub et al., "Model evasion attack on intrusion detection systems using adversarial machine learning," IEEE CISS, 2020.

- S. H. Silva and P. Najafirad, "Opportunities and challenges in deep learning adversarial robustness: A survey," arXiv preprint; arXiv:2007.00753, 2020.

- G. C. Marano et al., "Generative adversarial networks review in earthquake-related engineering fields," Bull. Earthq. Eng., vol. 22, no. 7, 2024.

- S. Bourou et al.," A review of tabular data synthesis using GANs on an IDS dataset”, Information, vol. 12, no. 9, 2021.

- R. Soleymanzadeh and R. Kashef," Efficient intrusion detection using multi-player generative adversarial networks (GANs): an ensemble-based deep learning architecture," Neural Comput. Appl., vol. 35, no. 17, 2023.

- K. Dutta et al., "Generative adversarial networks in security: A survey," IEEE UEMCON, 2020.

- R. Chauhan and S. S. Heydari, "Polymorphic adversarial DDoS attack on IDS using GAN, "ISNCC, 2020.

- P.-Y. Chen et al., "Zoo: Zeroth order optimization based black-box attacks to deep neural networks without training substitute models," ACM AI & Security Workshop, 2017.

- D. Golovin et al. "Gradientless descent: High-dimensional zeroth-order optimization; arXiv:1911.06317, 2019.

- S. Kumar, S. Gupta, and A. B. Buduru, "BB-Patch: BlackBox Adversarial Patch-Attack using Zeroth-Order Optimization," arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.06049, 2024.

- X. Tian et al., "Dynamic geothermal resource assessment: Integrating reservoir simulation and Gaussian Kernel Density Estimation under geological uncertainties," Geothermics, vol. 120, 2024.

- E. Aghaei and G. Serpen, "Host-based anomaly detection using Eigentraces feature extraction and one-class classification on system call trace data," arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.11284, 2019.

- G. Pillonetto et al., "Deep networks for system identification: a survey," Automatica, vol. 171, 2025.

- M. Ahsan et al.," Support vector data description with kernel density estimation (SVDD-KDE) control chart for network intrusion monitoring," Sci. Rep., vol. 13, no. 1, 2023.

- Y.-C. Chen, "A tutorial on kernel density estimation and recent advances," Biostatistics & Epidemiology, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 161-187, 2017.

- S. Węglarczyk, "Kernel density estimation and its application," in ITM web of conferences, 2018, vol. 23: EDP Sciences, p. 00037.

- D. V. Petrovsky et al., "PSSNet—An accurate super-secondary structure for protein segmentation," Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 23, no. 23, 2022.

- S.-M. Moosavi-Dezfooli, A. Fawzi, and P. Frossard, "Deepfool: a simple and accurate method to fool deep neural networks," in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 2574-2582.

- N. Fatehi, Q. Alasad, and M. Alawad, "Towards adversarial attacks for clinical document classification," Electronics, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 129, 2022.

- Shone, N. , et al., A deep learning approach to network intrusion detection. IEEE transactions on emerging topics in computational intelligence, 2018. 2(1): p. 41-50.

- S. Alahmed et al.," Impacting robustness in deep learning-based NIDS through poisoning attacks," Algorithms, vol. 17, no. 4, 2024.

- D. Jakubovitz and R. Giryes," Improving DNN robustness to adversarial attacks using Jacobian regularization,' ECCV, 2018.

- I. J. Goodfellow, J. Shlens, and C. Szegedy, "Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples," arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6572, 2014.

- N. Carlini and D. Wagner, "Towards evaluating the robustness of neural networks," in 2017 IEEE Symposium on security and privacy (sp), 2017: IEEE, pp. 39-57.

- N. Papernot et al.," The limitations of deep learning in adversarial settings, "IEEE EuroS&P, 2016.

- A. Madry et al., ʹTowards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks," arXiv:1706.06083, 2017.

- Kurakin, I. J. Goodfellow, and S. Bengio, "Adversarial examples in the physical world," in Artificial intelligence safety and security: Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018, pp. 99-112.

- M. Ahmed et al.," Re-Evaluating Deep Learning Attacks and Defenses in Cybersecurity Systems, "Big Data Cogn. Comput., vol. 8, no. 12, 2024.

- S. Aljawarneh, M. Aldwairi, and M. B. Yassein, "Anomaly-based intrusion detection system through feature selection analysis and building hybrid efficient model," Journal of Computational Science, vol. 25, pp. 152-160, 2018.

- N. Moustafa and J. Slay," UNSW-NB15: a comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set)," MilCIS, 2015.

- S. Alosaimi and S. M. Almutairi, "An intrusion detection system using BoT-IoT," Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 9, p. 5427, 2023.

- J. Song et al., 'Statistical analysis of honeypot data and building of Kyoto 2006+ dataset for NIDS evaluation," Workshop on Building Analysis Datasets, 2011.

- Manisha and, S. Gujar, "Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): What it can generate and What it cannot? arXiv:1804.00140, 2018.

- I. Sharafaldin, A. H. Lashkari, and A. A. Ghorbani, "Toward generating a new intrusion detection dataset and intrusion traffic characterization," ICISSp, vol. 1, no. 2018, pp. 108-116, 2018.

- L. Liu, P. Wang, J. Lin, and L. Liu, "Intrusion detection of imbalanced network traffic based on machine learning and deep learning," IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 7550-7563, 2020.

- F. Kilincer, F. Ertam, and A. Sengur, "Machine learning methods for cyber security intrusion detection: Datasets and comparative study," Computer Networks, vol. 188, p. 107840, 2021.

- I. Sharafaldin et al.," Developing realistic distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack dataset and taxonomy, "IEEE ICCST, 2019.

- S. Rizvi et al.," Application of artificial intelligence to network forensics: Survey, challenges and future directions," IEEE Access,2022.

- G. Singh and N. Khare, "A survey of intrusion detection from the perspective of intrusion datasets and machine learning techniques," Int. J. Comput. Appl., vol. 44, no. 7, 2022.

- V. Rampure and A. Tiwari, "A rough set based feature selection on KDD CUP 99 data set," Int. J. Database Theory Appl., 2015.

- A. Sharma and, H. Babbar, "Detecting cyber threats in real-time: A supervised learning perspective on the CTU-13 dataset," IEEE INCET, 2024.

- B. Yan and, G. Han, "Effective feature extraction via stacked sparse autoencoder to improve intrusion detection system," IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 41238-41248, 2018.

- M. Yousefi-Azar et al., "Autoencoder-based feature learning for cyber security applications," IEEE IJCNN, 2017.

- D. Han et al., "Evaluating and improving adversarial robustness of machine learning-based network intrusion detectors," IEEE JSAC, vol. 39, no. 8, 2021.

- M. Tavallaee et al., "A detailed analysis of the KDD CUP 99 data set," IEEE CISDA, 2009.

- V. L. Thing, IEEE 802.11" network anomaly detection and attack classification: A deep learning approach," IEEE WCNC, 2017.

- Y. Mirsky et al., "Kitsune: an ensemble of autoencoders for online network intrusion detection," arXiv:1802.09089, 2018.

- N. Narodytska and S. P. Kasiviswanathan, "Simple Black-Box Adversarial Attacks on Deep Neural Networks," in CVPR workshops, 2017, vol. 2, no. 2.

- S. Ghadimi and G. Lan, "Stochastic first-and zeroth-order methods for nonconvex stochastic programming," SIAM journal on optimization, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 2341-2368, 2013.

- A. Ilyas; et al. , "Black-box adversarial attacks with limited queries and information," ICML, 2018, Springer, pp. 261-273.

- D. Wierstra et al.," Natural evolution strategies," arXiv:1106.4487, 2011.

- P. Li; et al. , "Poisoning machine learning based wireless IDSs via stealing learning model," WASA, 2018.

- X. Zhou et al., "Hierarchical adversarial attacks against graph-neural-network-based IoT network intrusion detection system," IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 9310-9319, 2021.

- A. Hamza; et al. , "Detecting volumetric attacks on lot devices via sdn-based monitoring of mud activity," ACM Symposium on SDN Research, 2019, pp. 36-48.

- K. Xu et al., "Representation learning on graphs with jumping knowledge networks," ICML, 2018: pmlr, pp. 5453-5462.

- T. Kipf, "Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks," arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907, 2016.

- X. Zhou et al.,"Academic influence aware and multidimensional network analysis for research collaboration navigation based on scholarly big data," IEEE TETC, 2018.

- J. Ma, S. Ding, and Q. Mei, "Towards more practical adversarial attacks on graph neural networks," neurIPS, vol. 33, pp. 4756-4766, 2020.

- Z. Sun et al., "In-memory PageRank accelerator with a cross-point array of resistive memories," IEEE TED, 2020.

- J. Kotak and Y. Elovici, "Adversarial attacks against IoT identification systems,"IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 7868-7883, 2022.

- Sivanathan; et al. , "Classifying IoT devices in smart environments using network traffic characteristics," IEEE TMC, 2018.

- J. Tian, "Adversarial vulnerability of deep neural network-based gait event detection: A comparative study using accelerometer-based data," BSPC, vol. 73, p. 103429, 2022.

- Kuppa; et al. ,"Black box attacks on deep anomaly detectors," in Proceedings of the 14th international conference on availability, reliability and security, 2019, pp. 1-10. [Google Scholar]

- F. T. Liu, K. M. Ting, and Z.-H. Zhou, "Isolation forest," IEEE ICDM, 2008.

- B. Zong; et al. , "Deep autoencoding gaussian mixture model for unsupervised anomaly detection," ICLR, 2018.

- H. Zenati et al., "Adversarially learned anomaly detection," IEEE ICDM, 2018.

- Schölkopf; et al. , "Support vector method for novelty detection," neurIPS, 1999.

- T. Schlegl et al., "f-AnoGAN: Fast unsupervised anomaly detection with generative adversarial networks [J]," Medical image analysis, vol. 54, pp. 30-44, 2019.

- J. Aiken and S. Scott-Hayward, "Investigating adversarial attacks against network intrusion detection systems in sdns,"IEEE NFV-SDN, 2019.

- Q. Yan; et al. , "Automatically synthesizing DoS attack traces using generative adversarial networks," IJMLC, 2019.

- D. Shu; et al. , "Generative adversarial attacks against intrusion detection systems using active learning," in Proceedings of the 2nd ACM workshop on wireless security and machine learning, 2020.

- S. Guo; et al. , "A Black-Box Attack Method against Machine-Learning-Based Anomaly Network Flow Detection Models," Security and Communication Networks, vol. 2021, no. 1, p. 5578335, 2021.

- Y. Sharon et al, "Tantra: Timing-based adversarial network traffic reshaping attack," IEEE TIFS, 2022.

- B.-E. Zolbayar et al., "Generating practical adversarial network traffic flows using NIDSGAN," arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.06694, 2022.

- T. Hou,"IoTGAN: GAN powered camouflage against machine learning based IoT device identification," IEEE DySPAN, 2021.

- J. Bao, B. Hamdaoui, and W.-K. Wong, "Iot device type identification using hybrid deep learning approach for increased iot security," IEEE IWCMC, 2020.

- S. Aldhaheri and A. Alhuzali, "SGAN-IDS: Self-attention-based generative adversarial network against intrusion detection systems," Sensors, vol. 23, no. 18, p. 7796, 2023.

- M. Fan et al., "Toward Evaluating the Reliability of Deep-Neural-Network-Based IoT Devices," IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 9, no. 18, pp. 17002-17013, 2021.

- E. Wong, L. Rice, and J. Z. Kolter, "Fast is better than free: Revisiting adversarial training," arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.03994, 2020.

- Krizhevsky, V. Nair, and G. Hinton, "The CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets, 2014," URL https://www. cs. toronto. edu/~ kriz/cifar. html.

- M. Usama, J. Qadir, A. Al-Fuqaha, and M. Hamdi, "The adversarial machine learning conundrum: can the insecurity of ML become the achilles' heel of cognitive networks?" IEEE Network, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 196-203, 2019.

- A. Abusnaina, A. Khormali, D. Nyang, M. Yuksel, and A. Mohaisen, "Examining the robustness of learning-based ddos detection in software defined networks," IEEE DSC, 2019.

- M. J. Hashemi, G. Cusack, and E. Keller, "Towards evaluation of nidss in adversarial setting," in Proceedings of the 3rd ACM CoNEXT Workshop on Big DATA, Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Data Communication Networks, 2019, pp. 14-21.

- H. Zenati et al. arXiv:1802.06222, 2018.

- I. Homoliak et al., "Improving network intrusion detection classifiers by non-payload-based exploitindependent obfuscations: An adversarial approach," arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.02684, 2018.

- M. Teuffenbach, E. Piatkowska, and P. Smith, "Subverting network intrusion detection: Crafting adversarial examples accounting for domain-specific constraints," in International Cross-Domain Conference for Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, 2020: Springer, pp. 301-320.

- Y. Wang et al., "A c-ifgsm based adversarial approach for deep learning based intrusion detection,"VECoS, 2020: Springer, pp. 207-221.

- E. Anthi, "Hardening machine learning denial of service (DoS) defences against adversarial attacks in IoT smart home networks," computers & security, vol. 108, p. 102352, 2021.

- P. M. S. Sánchez et al., "Adversarial attacks and defenses on ML-and hardware-based IoT device fingerprinting and identification," Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 152, pp. 30-42, 2024.

- P. M. S. Sanchez et al., "LwHBench: A low-level hardware component benchmark and dataset for Single Board Computers," arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.08516, 2022.

- K. Roshan, A. Zafar, and S. B. U. Haque, "Untargeted white-box adversarial attack with heuristic defence methods in real-time deep learning based network intrusion detection system," Computer Communications, vol. 218, pp. 97-113, 2024.

- H. Xiao; et al. , "Is feature selection secure against training data poisoning?" in international conference on machine learning, 2015: PMLR, pp. 1689-1698.

- B. Biggio, B. Nelson, and P. arXiv:1206.6389, 2012.

- K. Yang et al.,"Adversarial examples against the deep learning based network intrusion detection systems," IEEE MILCOM, 2018.

- X. Peng, W. Huang, and Z. Shi, "Adversarial attack against dos intrusion detection: An improved boundary-based method," IEEE ICTAI, 2019.

- J. Lu, T. Issaranon, and D. Forsyth, "Safetynet: Detecting and rejecting adversarial examples robustly," IEEE ICCV, 2017.

- J. H. Metzen et al., "On detecting adversarial perturbations," arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.04267, 2017.

- M. Barreno et al., "The security of machine learning," Machine learning, vol. 81, no. 2, pp. 121-148, 2010.

- X. Chen et al., "Targeted backdoor attacks on deep learning systems using data poisoning," arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.05526, 2017.

- J. Wang et al., "Adversarial sample detection for deep neural network through model mutation testing," IEEE ICSE, 2019.

- A. Raghuvanshi; et al. , "Intrusion detection using machine learning for risk mitigation in IoT-enabled smart irrigation in smart farming," Journal of Food Quality, vol. 2022, no. 1, p. 3955514, 2022.

- C. Benzaïd, M. Boukhalfa, and T. Taleb, "Robust self-protection against application-layer (D) DoS attacks in SDN environment," IEEE WCNC, 2020.

- H. Benaddi; et al. , "Anomaly detection in industrial IoT using distributional reinforcement learning and generative adversarial networks," Sensors, vol. 22, no. 21, p. 8085, 2022.

- G. Li et al., "DeSVig: Decentralized swift vigilance against adversarial attacks in industrial artificial intelligence systems," IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 3267-3277, 2019.

- M. Mirza and S. Osindero, "Conditional generative adversarial nets," arXiv preprint arXiv:1411.1784, 2014.

- H. Benaddi; et al. , "Adversarial attacks against iot networks using conditional gan based learning," IEEE GLOBECOM 2022, pp. 2788-2793.

- Odena, C. Olah, and J. Shlens, "Conditional image synthesis with auxiliary classifier gans," in International conference on machine learning, 2017: PMLR, pp. 2642-2651.

- G. S. Dhillon et al., "Stochastic activation pruning for robust adversarial defense," arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.01442, 2018.

- R. Abou Khamis, M. O. Shafiq, and A. Matrawy, "Investigating resistance of deep learning-based ids against adversaries using min-max optimization," IEEE ICC, 2020.

- M. Pawlicki, M. Choraś, and R. Kozik, "Defending network intrusion detection systems against adversarial evasion attacks," Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 110, pp. 148-154, 2020.

- A. Ganesan and, K. Sarac, "Mitigating evasion attacks on machine learning based nids systems in sdn," IEEE NetSoft, 2021.

- I. Debicha; et al. , "Detect & reject for transferability of black-box adversarial attacks against network intrusion detection systems," ACeS, 2021: Springer, pp. 329-339.

- M. P. Novaes et al., "Adversarial Deep Learning approach detection and defense against DDoS attacks in SDN environments," Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 125, pp. 156-167, 2021.

- R. Yumlembam et al., "Iot-based android malware detection using graph neural network with adversarial defense," IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 10, no. 10, pp. 8432-8444, 2022.

- M. K. Roshan and A. Zafar, "Boosting robustness of network intrusion detection systems: A novel two phase defense strategy against untargeted white-box optimization adversarial attack," Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 249, p. 123567, 2024.

- Z. Awad, M. Zakaria, and R. Hassan, "An enhanced ensemble defense framework for boosting adversarial robustness of intrusion detection systems," Scientific Reports, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 14177, 2025.

- B. Nelson et al., "Misleading learners: Co-opting your spam filter," in Machine learning in cyber trust: Security, privacy, and reliability: Springer, 2009, pp. 17-51.

- G. Apruzzese et al.," AppCon: Mitigating evasion attacks to ML cyber detectors," Symmetry, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 653, 2020.

- G. Apruzzese and M. Colajanni, "Evading botnet detectors based on flows and random forest with adversarial samples," IEEE NCA, 2018.

- M. Siganos et al., "Explainable ai-based intrusion detection in the internet of things," in Proceedings of the 18th international conference on availability, reliability and security, 2023, pp. 1-10.

- C. Park et al., "An enhanced AI-based network intrusion detection system using generative adversarial networks," IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 2330-2345, 2022.

- M. A. Sen, "Attention-GAN for anomaly detection: A cutting-edge approach to cybersecurity threat management," arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.15945, 2024.

- H. Larijani et al., "An adversarial attack detection paradigm with swarm optimization," IEEE IJCNN, 2020.

- S. Waskle, L. Parashar, and U. Singh, "Intrusion detection system using PCA with random forest approach," IEEE ICESC, 2020.

- A. H. Mirza, "Computer network intrusion detection using various classifiers and ensemble learning," IEEE SIU, 2018.

- Q. R. S. Fitni and K. Ramli, "Implementation of ensemble learning and feature selection for performance improvements in anomaly-based intrusion detection systems," IEEE IAICT, 2020.

- P. Li et al., "Chronic poisoning against machine learning based IDSs using edge pattern detection," IEEE ICC, 2018.

- M. Usama et al.,"Black-box adversarial machine learning attack on network traffic classification," IEEE IWCMC, 2019.

- A. Warzyński and, G. Kołaczek, "Intrusion detection systems vulnerability on adversarial examples," IEEE INISTA, 2018.

- S. Zhao et al., "attackgan: Adversarial attack against black-box ids using generative adversarial networks," Procedia Computer Science, vol. 187, pp. 128-133, 2021.

- Z. Lin, Y. Shi, and Z. Xue, "Idsgan: Generative adversarial networks for attack generation against intrusion detection," KDDM, 2022: Springer, pp. 79-91.

- A. Punitha, S. Vinodha, R. Karthika, and R. Deepika, "A feature reduction intrusion detection system using genetic algorithm," IEEE ICSCAN, 2019.

- Q. Alasad, M. M. Hammood, and S. Alahmed, "Performance and Complexity Tradeoffs of Feature Selection on Intrusion Detection System-Based Neural Network Classification with High-Dimensional Dataset," ICETIS, 2022: Springer, pp. 533-542.

| Description | Description | Examples in NIDS Context | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Level of knowledge on the attacked model that the assaulter knows. | Black-box: Only input-output access. Gray-box: Limited dataset access. White-box: Full access to model parameters. |

[13] |

| Timing | When the attack occurs in the ML lifecycle. | Evasion: During the testing, to misclassify. Poisoning: During the training, to corrupt data. |

[14,29,35] |

| Goals | Attacker's objective. | Targeted: Specific misclassification. Non-targeted: General error induction. |

[36] |

| Capabilities | Attacker's access and actions on the system. | Full access: Modify model internals. Limited: Query outputs only. |

[10,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,32] |

| Attack Technique | Type (White/Black /Gray) | Strengths | Weaknesses | Success Rate in NIDS (Examples) | Datasets Tested | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GANs | Black/White /Gray |

High evasion; realistic samples | Computationally intensive | 98% evasion [41] | CICIDS2017 | [14,26,37,38,39,40,41] |

| ZOO | Black | Gradient-free; black-box effective | High query count; slow | 97% on DNNs [42] | NSL-KDD | [ 1,42,43,44 ] |

| KDE | White/Black | Non-parametric density estimation | Bandwidth sensitivity | 95% outlier detection [48] | NSL-KDD | [45,46,47,48,49,50,51] |

| DeepFool | Black/White | Minimal perturbations | Compute-heavy; white-box only | 90% misclassification [52] | KDDCup99 | [ 14,26,52 -56 ] |

| FGSM | White | Fast generation | Less transferable | 97% on CNN [57] | KDDCup99 | [25,57] |

| C&W | White | Optimized for distances (L0/L2/L∞) | Resource-intensive | 95% bypass [58] | Various | [ 24,58] |

| JSMA | White | Targets key features | Slow; feature-specific | 92% targeted [59] | NSL-KDD | [24,59] |

| PGD | White | Constrained optimization | Iterative; compute-costly | 96% robust test [60] | CICIDS2017 | [24,60] |

| BIM | White | Multi-step improvements | Similar to PGD but basic | 94% evasion [61] | CICIDS2017 | [24,61] |

| Dataset | Pros | Cons | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSL-KDD | Addresses KDD99 imbalances; 41 features for efficient processing. | Outdated (pre-2010); lacks modern attacks like IoT-specific threats. | [14,63] |

| UNSW-NB15 | Realistic traffic; 49 features including raw data. | Large size (~100 GB); requires heavy preprocessing. | [14,64] |

| BoT-IoT | Includes botnet and IoT attacks; real network simulation. | Limited to specific protocols (HTTP, TCP, UDP); small sample size. | [65] |

| Kyoto 2006+ | Long-term data (3+ years); honeypot-based with diverse features. | Older traffic (up to 2015); may not reflect 2025 threats. | [66,67] |

| CICIDS2017 | Modern attacks; 80 features in flow/packet formats. | Synthetic; potential biases in simulation. | [4,20] |

| CSE-CIC-IDS2018 | Updated with AWS simulation; 80 features, real cyberattacks. | Resource-intensive; focuses on DDoS/volumetric attacks. | [68] |

| CIC-IDS2019 | Fixes prior flaws; 87 features with new DDOS attacks. | Large volume; class imbalance in some categories. | [71,72] |

| ADFA-LD | Host-based with zero-day/malware; Windows/Linux samples. | Limited to host IDS; not network-flow focused. | [73] |

| KDD CUP 99 | Classic benchmark; 41 features with labeled attacks. | Highly outdated (1998); redundant/irrelevant records. | [74] |

| CTU-13 | Botnet-focused; 153 attack types in Pcap/Netflow. | Synthetic; limited to botnets, not broad threats. | [75] |

| Year | Ref. | Dataset | Setting | Models | Strategy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTAKS | 2012 | [127] | Real data, Artificial data | Gray Box | SVM | Poisoning |

| 2015 | [126] | PDF Malwav | Gray Box | LASSO, Ridge Regression | Poisoning | |

| 2018 | [86] | WSN- DS, Kyoto2006 +, NSL-KDD | Black Box | DNN | Poisoning | |

| 2019 | [32] | Tu-13 | Black Box | K-NN, ML, RF | Evasion, Poisoning | |

| 2019 | [129] | CICIDS2017, KDDCup99 | Black Box | DNN | Evasion, Poisoning | |

| 2019 | [96] | CICIDS2018 | Black Box | DAGMM, IF, GAN, BIGM, AE, One-class SVM | Evasion | |

| 2019 | [103] | CISIDS2017, DARPA | Black Box | K-NN, RF, SVM, LR | Evasion | |

| 2019 | [104] | KDDCup99 | Black Box | CNN | Evasion | |

| 2019 | [115] | NSL-KDD | White Box | SVM, DNN | Evasion | |

| 2019 | [116] | KDD-Cup99, NSL-KDD | White Box | CNN | Evasion | |

| 2019 | [119] | ASNM-NPBO | Gray Box | NB, DT, SVM, LR, NB | Evasion | |

| 2020 | [34] | NSL-KDD, UNSWNB15 | White Box | SVM, DT, NB, K-NN, RF, MLP | Evasion | |

| 2020 | [41] | CISIDS2017 | Black Box | DT, LR, NB, RF | Evasion, Poisoning | |

| 2020 | [105] | CICIDS2017 | Black Box | GAN with Activation Learning | Evasion | |

| 2020 | [78] | CICIDS2017, Kitsune | Black Box, Gray Box | Kitsune, IF, LR, SVM, DT, MLP | Evasion | |

| 2020 | [12] | CICIDS2017, NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15 | White Box | CNN, DT, K-NN, LR, LSTM, RF, Adaboost | Evasion | |

| 2020 | [120] | CICIDS2017, NSL-KDD | White Box | DNN, AE, DBW | Evasion | |

| 2020 | [128] | NSL-KDD | Gray Box | DNN | Evasion | |

| 2021 | [87] | UNSW-SOSR2019 | Black Box | GNN | Poisoning | |

| 2021 | [106] | CICIDS2018, KDDCup99 | Black Box | CNN, KNN, MLP, SVM | Evasion | |

| 2021 | [107] | UNSW, IOT Trace | Black Box | Random Forest, Decision Tree, KNN, SVM | Evasion | |

| 2021 | [114] | CIFAR-100, CIFAR-10 | White Box | DNN | Poisoning | |

| 2022 | [94] | IOT-Trace | Black Box | FCN, GAP, CNN | Poisoning | |

| 2022 | [108] | CISIDS2017, NSL-KDD | Black Box | KNN, SVM, DNN | Evasion | |

| 2022 | [5] | CSE-CICIDS2018 | Black Box | GAN, RF | Evasion | |

| 2023 | [111] | NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017 | Black Box | SGAN-IDS | Evasion | |

| 2024 | [62] | CSE.CICIDS2018, ADFA-LDs, CICIDS2019 | Black Box | DNN | Evasion | |

| 2024 | [55] | CSE-CICIDS2017 | Black Box | DL | Poisoning | |

| 2024 | [123] | LWHBench | White Box | CNN and LSTM | Evasion |

| Year | Ref. | Dataset | Setting | Models | Strategy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | [151] | Emails, Dictionaries |

Gray Box | Spam Boyes | Poisoning | |

|

Defenses against adversarial examples and attacks |

2010 | [132] | Healthcare dataset, Malware dataset, image dataset | Black Box | Regression Model, Classification Model, Generative Model | Poisoning |

| 2017 | [133] | YouTube dataset, Aligned face | Black Box | Deep ID, VGG-face | Poisoning | |

| 2019 | [11] | KDDCup99 | Black Box | SVM, DNN, LE, KNN, NB, RF, DT | Evasion | |

| 2019 | [134] | CIFAR10, MNIST | Black Box | DNN | Evasion | |

| 2019 | [142] | UNSW-NB15 | White Box | DNN | Evasion | |

| 2020 | [4] | CICDS2017 | White Box | DAGMM, BIGAN, Kitsune, DAE | Evasion | |

| 2020 | [31] | NSL-KDD | White Box | DNN | Evasion | |

| 2020 | [157] | NSL-KDD | White Box | DNN, ABC, and RNN-ADV | Evasion, poisoning |

|

| 2020 | [136] | CICIDS2017 | White Box |

MLP | Poisoning | |

| 2020 | [144] | CICDS2017 | White Box | Adaboost, DNN, EF, SVM, K-NN | Evasion | |

| 2020 | [153] | CTU-13 | Gray Box | Adaboost, DT, MLP, RF, WND | Evasion | |

| 2021 | [145] | CICDS2017, DARPA, KDDCup99 | White Box | RF, LR, SVM, DNN | Evasion | |

| 2021 | [146] | NSL-KDD | White Box | SVM, RF, LR, DT, LDA, and DNN. | Evasion | |

| 2021 | [147] | CICIDS2019 | White Box | LSTM, MLP, GAN, CNN | Evasion | |

| 2022 | [5] | CSE-CICIDS2018 | Black Box | RF, GAN | Evasion | |

| 2022 | [135] | NSL-KDD | Black Box | DNN, SVM | Evasion | |

| 2022 | [137] | Orchestration System dataset / The Distributed Smart Space. | White Box | DRL | Poisoning | |

| 2022 | [ 148] | CMaLdroid, Drebin | White Box | GNN | Evasion | |

| 2023 | [154] | IEC60879-5-104, CIC-IOT Dataset. 2022. | Gray Box | DT, RF, Adaboost, DNN, LR | Evasion | |

| 2023 | [154] | NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15 | Gray Box | CNN, DNN, GAN, Autoencoder | Evasion | |

| 2024 | [62] | CSE.CICIDS2018, ADFA-LDs, CICIDS2019 | Black Box | DNN | Evasion | |

| 2024 | [149] | CICIDOS2019 | White Box | Feature Squeezing | Evasion | |

| 2024 | [156] | CICIDS2017, KDD-Cup | Gray Box | Attention, GAN | Evasion | |

| 2025 | [10] | Various (taxonomy-focused) | White/Black/Gray | ML models (general taxonomy) | Evasion, Poisoning |

|

| 2025 | [14] | CICIDS2017, NSL-KDD | Black Box | DNN, RF | Evasion | |

| 2025 | [150] | CICIDS2019 | Gray Box | Ensemble (RF + DNN) | Evasion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).