Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Category | Definition | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Core Concepts | ||

| Hallucination | Output inconsistent with model’s knowledge (context or training) | Fluent but factually or logically wrong |

| Factuality | Output matches real-world facts | Can be outdated or missing info |

| Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic | ||

| Intrinsic | Contradicts input context | Wrong data in source summary |

| Extrinsic | Unsupported by input or training | Fabricated facts beyond knowledge |

| Faithfulness vs. Factuality | ||

| Faithfulness | Violates user instructions or context | Ignoring prompt or internal contradictions |

| Factuality | Conflicts with real-world truth | Made-up or false facts |

| Domain-Specific Types | ||

| Contradiction | Fact or context violation | Entity/relation errors, self-contradiction |

| Fabrication | Made-up entities/events | False citations, image-text mismatches |

| Logical Fallacies | Flawed reasoning or code | Invalid logic, dead code |

1.1. Definition: From Factual Deviation to Internal Inconsistency

1.2. Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic

- Intrinsic Hallucinations: An intrinsic hallucination occurs when the model generates content that directly contradicts the user-provided input. It reflects a failure to remain faithful to the immediate context. For example, if a source text states that a company’s revenue was $10 million, but the summary produced by the model reports $15 million, this constitutes an intrinsic hallucination [10]. This category focuses on the model’s ability to accurately represent information available during inference [11].

- Extrinsic Hallucinations: This error occurs when the model generates content that cannot be verified from the provided context and is inconsistent with its training data. It involves fabricating unsupported information. For example, if a summary includes, “The CEO also announced plans to expand into the Asian market,” despite no such statement in the source or likely in training data, it constitutes an extrinsic hallucination. This category reflects the model’s tendency to over-extrapolate or fill gaps beyond its knowledge, often when generating novel content based solely on task instructions. It underscores the model’s limitations in recognizing the boundaries of its internal knowledge [10].

1.3. Factuality vs. Faithfulness Framework

- Instruction inconsistency: failure to follow or accurately interpret user instructions.

- Context inconsistency: contradiction of the provided input, aligning closely with intrinsic hallucinations.

- Logical inconsistency: internal contradictions within the generated output itself.

1.4. Domain-Specific Manifestations of Hallucination

-

Contradiction: This category captures direct violations of known facts or inconsistencies with provided context [15,16].Factual contradiction occurs when the model generates statements that are inconsistent with real-world knowledge [4]. These may include entity-error hallucinations (e.g., naming an incorrect entity) or relation-error hallucinations (e.g., misrepresenting a relationship between entities).Context-conflicting hallucinations emerge when generated output contradicts previous model outputs. For example, a summary might incorrectly substitute a person’s name mentioned earlier [17].Input-conflicting hallucinations arise when generated content diverges from the user’s original input, such as adding details not found in the source material [17].In code generation, context inconsistency refers to contradictions between newly generated code and prior code or user input, often manifesting as subtle logical flaws [18,19].A distinct subcategory is self-contradiction, where the model outputs two logically inconsistent statements within the same response, even though it was conditioned on a unified context [19].

-

Fabrication: This form of hallucination involves the generation of entities, events, or citations that are entirely fictitious or unverifiable [20].In MLLMs, fabrication often manifests as mismatches between visual inputs and textual descriptions.Object category hallucinations involve naming objects that do not appear in the image (e.g., mentioning a “laptop” or “small dog” that isn’t present).Object attribute hallucinations occur when properties such as shape, color, material, or quantity are inaccurately described—e.g., referring to a man as “long-haired” when he is not. These may include event misrepresentations or counting errors.Object relation hallucinations involve incorrect assertions about spatial or functional relationships (e.g., “the dog is under the table” when it is beside it) [14].In high-stakes medical applications, where AI is increasingly used for diagnosis, treatment, and patient monitoring [21,22,23], fabrication can result in hallucinated clinical guidelines, procedures, or sources that do not exist [24].More broadly, fabrication occurs when LLMs are prompted with questions beyond their training knowledge or lack sufficient data, leading them to generate plausible-sounding but unsupported content.

-

Logical Fallacies: These hallucinations reflect flawed reasoning or illogical outputs in tasks requiring step-by-step reasoning [25,26].In medicine, these errors fall under the umbrella of Incomplete Chains of Reasoning, encompassing:

- *

- Reasoning hallucination—incorrect logic in clinical explanations;

- *

- Decision-making hallucination—unsound treatment suggestions;

- *

- Diagnostic hallucination—medically invalid diagnoses [24].

In general LLMs, such flaws are often labeled as logical inconsistencies, which include internal contradictions within the same output.In code generation, this includes:- *

- Intention conflicts, where the generated code deviates from the intended functionality—either in overall or local semantics [27];

- *

In multimodal contexts, logical fallacies may appear as judgment errors, such as incorrect answers to visual reasoning tasks.

2. Hallucination Detection Methods

2.1. Uncertainty-Based Detection

- Logit-Based Estimation (Grey-box): Measures output entropy or minimum token probability. Higher entropy is often correlated with hallucinations [29]. This approach operates on the principle that the model’s confidence is encoded in its output probability distribution. Techniques in this category analyze the token-level logits provided by the model’s final layer. A high Shannon entropy across the vocabulary for a given token position indicates that the model is uncertain and distributing probability mass widely, which is a strong signal of potential hallucination. Other metrics include using the normalized probability of the generated token itself; a low probability suggests the model found the chosen token unlikely, even if it was selected during sampling.

- Consistency-Based Estimation (Black-box): Generates multiple completions for the same prompt and computes their agreement via metrics such as BERTScore or n-gram overlap. Used in SelfCheckGPT [32] and variants. For example, SelfCheckGPT generates multiple responses and compares them to the original sentence using metrics like n-gram overlap, BERTScore, or even a question-answering framework to see if questions derived from one response can be answered by others. A statement that is not consistently supported across multiple generations is flagged as a potential hallucination. However, this method’s primary drawback is its computational cost, as it requires multiple inference calls for a single detection, and it may fail if the model consistently makes the same factual error across all outputs.

2.2. Knowledge-Based Detection (Fact-Checking and Grounding)

- External Retrieval (RAG-based): This approach transforms hallucination detection into a fact-checking task by grounding the LLM’s output in external, authoritative knowledge. A typical RAG-based verifier works by first decomposing the generated text into a set of verifiable claims or facts. Each claim is then used as a query to a retriever, which fetches relevant snippets from a knowledge corpus (e.g., Wikipedia or a domain-specific database). Finally, a verifier model, often an NLI (Natural Language Inference) model or another LLM, assesses whether the retrieved evidence supports, refutes, or is neutral towards the claim. While powerful, this method is dependent on the quality of both the retriever and the external knowledge base; retrieval failures or outdated sources can lead to incorrect verification. [35].

- Internal Verification (Chain-of-Verification): This black-box technique cleverly prompts the model to critique its own outputs without external tools. The process unfolds in a structured sequence: (1) the LLM generates an initial response; (2) it is then prompted to devise a series of verification questions to fact-check its own response; (3) it attempts to answer these questions independently; and (4) finally, it generates a revised, final answer based on the outcome of its self-verification process. This method encourages a form of self-reflection, forcing the model to re-examine its claims and correct inconsistencies. Its main advantage is its resource independence, but its effectiveness is bounded by the model’s own internal knowledge and its ability to formulate useful verification questions. [36].

- ChainPoll Adherence (Closed-domain): Judges how well output aligns with provided evidence passages using multi-round CoT prompting and majority voting [33].

2.3. Dedicated Detection Models

- QA-Based Fact Checking: Converts model outputs to questions and uses QA pipelines to retrieve answers from source text. Discrepancies reveal hallucinations [39].

| Technique | Detection Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SelfCheckGPT | Consistency-based (Black-box) | [44] |

| ChainPoll | Prompt-based Judge (Black-box) | [33] |

| G-Eval | Prompted LLM with scoring aggregation | [45] |

| RAG + Verifier | Retrieval-based Fact-checking (Grey/Black-box) | [46] |

| Chain-of-Verification | Internal self-questioning (Black-box) | [36] |

| Graph-based Context-Aware (GCA) | Reference alignment via graph matching | [47] |

| ReDeEP | Mechanistic interpretability in RAG | [48] |

| Drowzee (Metamorphic Testing) | Logic-programming and metamorphic prompts | [49] |

| MIND (Internal-state monitoring) | Internal activations | [50] |

| Verify-when-Uncertain | Combined self- and cross-model consistency (Black-box) | [31] |

| Holistic Multimodal LLM Detection | Bottom-up detection in Multimodal LLMs | [51] |

| Large Vision Language Models Hallucination Benchmarks/M-HalDetect | Multimodal reference-free detection | [52] |

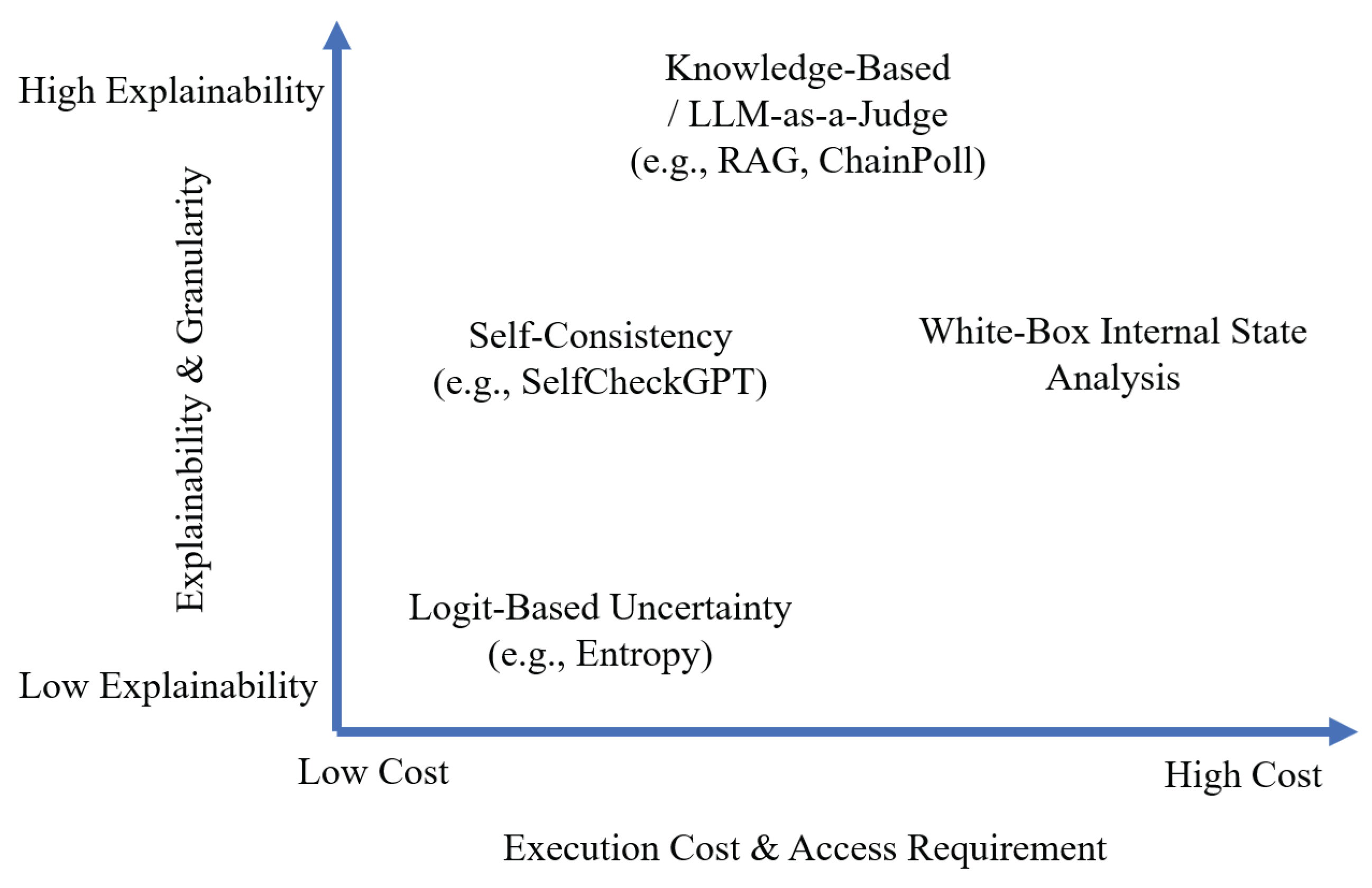

2.4. Summary and Practical Considerations

- Application Scope: Whether the hallucination is open-domain (factual world knowledge) or closed-domain (reference-consistent).

- Model Access: Varying from full access to weights (white-box) to restricted API-only access (black-box).

- Efficiency: Cost of multiple generations (e.g., 20 runs in SelfCheckGPT vs. 5 in ChainPoll).

- Explainability: Whether human-readable justifications are provided (e.g., CoT in ChainPoll, entailment evidence in NLI). This aligns with a growing demand for user-friendly and explainable frameworks in AI-driven processes, such as those being developed for AutoML [53].

3. Hallucination Mitigation Strategies

3.1. Data-Centric and Pre-Training Strategies

3.1.1. High-Quality Data Curation and Filtering

3.1.2. Retrieval-Augmented Pre-Training

3.2. Model-Centric Strategies: Fine-Tuning and Alignment

3.2.1. Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)

3.2.2. Preference Optimization for Alignment

3.2.3. Knowledge Editing: Surgical Model Updates

- ROME (Rank-One Model Editing): Introduces a rank-one update to a single MLP layer to revise a single fact.

- MEMIT (Mass Editing Memory in Transformers): Extends ROME to modify multiple layers, allowing batch editing of thousands of facts.

- GRACE: Stores updated knowledge in an external memory module without modifying model parameters.

- In-Context Editing (ICE): A training-free approach that injects new facts into the prompt context during inference.

3.3. Inference-Time Mitigation Strategies

- Knowledge-Augmented Generation: Augment the prompt with retrieved external evidence.

- Structured Reasoning and Self-Correction: Guide the generation process through explicit, multi-step reasoning [72].

- Advanced Decoding and Intervention: Modify the decoding process or directly intervene in the model’s internal activations [73].

3.3.1. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

- Retrieve: Search a knowledge base (e.g., via dense retrieval) using the user query.

- Augment: Append retrieved evidence to the prompt.

- Generate: Produce a response conditioned on both the query and the retrieved documents.

- Iterative RAG: Performs multiple rounds of retrieval and generation.

- Self-Corrective RAG: The model generates a draft, then retrieves evidence to revise its own output.

3.3.2. Structured Reasoning and Self-Correction

- Generate a baseline answer.

- Plan verification questions.

- Independently answer the questions.

- Revise the original response based on verification.

3.3.3. Advanced Decoding and Intervention Strategies

- DoLa (Decoding by Contrasting Layers): Amplifies factual content by contrasting logit distributions from mature (later) and premature (earlier) layers, suppressing shallow patterns and emphasizing deep semantic knowledge [60].

- CAD (Context-Aware Decoding): Forces the model to attend to provided evidence by penalizing tokens that would have been generated in the absence of context. This encourages grounding in retrieved or injected information, reducing reliance on parametric priors [61].

- Inference-Time Intervention (ITI): This white-box technique seeks to steer the model’s internal state toward more truthful representations. ITI begins by applying linear probing to a dataset such as TruthfulQA [74], identifying a sparse set of attention heads whose activations correlate strongly with truthful responses. Then, during inference, a small learned vector is added to the output of these attention heads at each generation step. This nudges the model’s activations in truth-correlated directions, substantially improving truthfulness with minimal computational overhead and no parameter updates.

3.4. A Unified View and Future Directions

- Foundation Layer (Data): High-quality pre-training data serves as the first line of defense. This layer emphasizes automated filtering, deduplication, and upsampling of trusted sources to ensure a strong factual grounding in the parametric knowledge of the model.

- Core Layer (Model Alignment): Alignment methods like Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) shape the model’s behavior toward factual and safe outputs. For known factual inaccuracies, targeted Knowledge Editing methods (e.g., ROME, MEMIT) provide localized corrections without retraining the entire model.

- Application Layer (Inference-Time Grounding): Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and related techniques are applied at deployment to supplement parametric knowledge of the model with up-to-date domain-specific information, helping mitigate knowledge gaps and ensure temporal relevance.

- Guardrail Layer (Verification and Post-processing): Structured reasoning strategies like Chain-of-Verification (CoVe) enforce internal consistency through self-checking. Finally, detection tools serve as a post-hoc safety net, flagging hallucinated outputs for human review or triggering fallback behaviors (e.g., “I don’t have enough information to answer”).

- Scalable Data Curation: Developing fully automated, scalable, and multilingual pipelines for high-quality data curation remains a foundational challenge, especially at trillion-token scales.

- The Alignment–Capability Trade-off: Overalignment may suppress the model’s general capabilities—such as reasoning or creativity—resulting in an “alignment tax.” Research is needed to develop alignment strategies that maintain or even enhance model utility across tasks.

- Editing Reasoning, Not Just Facts: Most knowledge editing methods target discrete facts. However, true robustness requires the ability to trace and modify the deeper reasoning paths through which those facts influence behavior—a challenge that demands more advanced mechanistic interpretability.

- Compositionality of Mitigation Techniques: While combining mitigation methods appears beneficial, their interactions are poorly understood. For example, how does RAG interact with ITI or DPO? Can editing methods interfere with self-correction routines? Systematic analysis is needed to develop principled strategies for composing techniques effectively.

- The Inevitability of Hallucination: An emerging perspective suggests that hallucination may be an inherent artifact of probabilistic next-token generation and the current training paradigm. If so, mitigation efforts may shift from eliminating hallucinations to managing them through uncertainty estimation, robust detection, fallback policies, and human-in-the-loop oversight.

4. Recent Trends and Open Issues

4.1. Emerging Trends in Mitigation and Detection

- Shift Toward Simpler Alignment Methods: There is a notable trend away from complex, multi-stage alignment pipelines like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) towards simpler, more stable, and mathematically direct alternatives. The rapid adoption of Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) and its variants exemplifies this, as it achieves comparable or superior performance to RLHF without the need to train a separate reward model, thus reducing complexity and computational overhead.

- Rise of Surgical Knowledge Editing: Rather than relying on costly full-model fine-tuning, researchers are increasingly developing "surgical" methods to edit a model’s internal knowledge directly. Techniques like ROME and MEMIT use mechanistic interpretability to locate and precisely modify the model parameters responsible for storing specific facts. This allows for the efficient correction of factual errors without risking the catastrophic forgetting of other knowledge.

- Advanced Inference-Time Interventions: A major area of innovation is the development of techniques that operate during the generation process, requiring no parameter updates. These methods are highly practical as they can be applied to any model, including proprietary APIs. This trend includes Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipelines that ground outputs in external evidence, self-correction routines [75] like Chain-of-Verification (CoVe) that prompt a model to fact-check its own statements, and advanced decoding strategies (e.g., DoLa, ITI) that intervene in a model’s internal activations to steer it toward more truthful outputs.

- Development of LLM-as-a-Judge Paradigms: For detection, there is a growing reliance on using powerful LLMs themselves as evaluators. The LLM-as-a-Judge [40,76] paradigm, seen in methods like G-Eval [45], leverages the advanced reasoning capabilities of frontier models (e.g., GPT-4) to assess the factuality and faithfulness of outputs from other models, often outperforming traditional metrics and approaching human-level judgment.

4.2. Key Open Problems

- Scalable and High-Quality Data Curation: The principle of ’garbage in, garbage out’ remains a fundamental obstacle. Developing fully automated, scalable, and multilingual pipelines for curating high-quality, factually accurate, and diverse training data is a critical and unresolved challenge, especially at the scale of trillions of tokens.

- The Alignment-Capability Trade-off: A critical open problem is the risk of an "alignment tax," where interventions to enhance factuality and reduce hallucinations inadvertently diminish other valuable model capabilities. Aggressive fine-tuning or preference optimization (like RLHF or DPO) can make a model overly cautious, causing it to refuse to answer reasonable questions or lose its ability to perform complex, multi-step reasoning. For instance, a model heavily optimized for factuality might become less creative or struggle with tasks that require nuanced inference beyond explicitly stated facts. This trade-off forces a difficult balance: how can we make models more truthful without making them less useful? Future research must focus on developing alignment techniques that are more targeted and less disruptive. This could involve disentangling different model capabilities at a mechanistic level, allowing for surgical interventions that correct for factuality without impairing reasoning or creativity. Another promising direction is developing alignment methods that explicitly reward nuanced behaviors, such as expressing uncertainty or providing conditional answers, rather than simply penalizing any output that cannot be externally verified. Synthesizing factuality with utility remains a central challenge for the next generation of LLMs.

- Editing Reasoning Paths, Not Just Facts: Current knowledge editing techniques (e.g., STRUEDIT [77]) are effective at correcting discrete, single-hop facts (e.g., "Paris is the capital of France"). However, they struggle to update the complex, multi-hop reasoning pathways that depend on those facts. Advancing from fact-editing to reasoning-path editing is a major frontier that will require more sophisticated mechanistic interpretability tools.

- Compositionality of Mitigation Techniques: The most robust systems will likely employ a "defense-in-depth" strategy that layers multiple mitigation techniques. However, the interactions between these methods are poorly understood. Research is needed to develop a principled understanding of how different strategies (e.g., RAG, DPO, and knowledge editing) can be composed effectively without interfering with one another.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CAD | Context-Aware Decoding |

| Cal-DPO | Calibrated Direct Preference Optimization |

| CoT | Chain-of-Thought |

| CoVe | Chain-of-Verification |

| DPO | Direct Preference Optimization |

| GCA | Graph-based Context-Aware |

| ICE | In-Context Editing |

| IFMET | Interpretability-based Factual Multi-hop Editing in Transformers |

| ITI | Inference-Time Intervention |

| KG | Knowledge Graph |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| MEMIT | Mass Editing Memory in Transformers |

| MIND | Internal-state monitoring |

| MLLM | Multimodal Large Language Model |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| RETRO | Retrieval-Enhanced Transformer |

| RLHF | Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback |

| RLFH | Reinforcement Learning for Hallucination |

| ROME | Rank-One Model Editing |

| SFT | Supervised Fine-Tuning |

| V-DPO | Vision-guided Direct Preference Optimization |

References

- Sajjadi Mohammadabadi, S.M.; Kara, B.C.; Eyupoglu, C.; Uzay, C.; Tosun, M.S.; Karakuş, O. A Survey of Large Language Models: Evolution, Architectures, Adaptation, Benchmarking, Applications, Challenges, and Societal Implications. Electronics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadabadi, S.M.S. From generative ai to innovative ai: An evolutionary roadmap. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, E.; Chen, L.T.; Vijayakumar, T.M.; Asumah, H.; Tretheway, P.; Liu, L.; Fu, Y.; Chu, P. AI-generated and YouTube Videos on Navigating the US Healthcare Systems: Evaluation and Reflection. International Journal of Technology in Teaching & Learning 2024, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Yu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhong, W.; Feng, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Peng, W.; Feng, X.; Qin, B.; et al. A survey on hallucination in large language models: Principles, taxonomy, challenges, and open questions. ACM Transactions on Information Systems 2025, 43, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadabadi, S.M.S.; Entezami, M.; Moghaddam, A.K.; Orangian, M.; Nejadshamsi, S. Generative artificial intelligence for distributed learning to enhance smart grid communication. International Journal of Intelligent Networks 2024, 5, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawte, V.; Sheth, A.; Das, A. A survey of hallucination in large foundation models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.05922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Dong, Y.; Cheung, J.C.K. Hallucinated but factual! inspecting the factuality of hallucinations in abstractive summarization. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.09784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, Y.; Cahyawijaya, S.; Lee, N.; Dai, W.; Su, D.; Wilie, B.; Lovenia, H.; Ji, Z.; Yu, T.; Chung, W.; et al. A multitask, multilingual, multimodal evaluation of chatgpt on reasoning, hallucination, and interactivity. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.04023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, Y.; Ji, Z.; Schelten, A.; Hartshorn, A.; Fowler, T.; Zhang, C.; Cancedda, N.; Fung, P. Hallulens: Llm hallucination benchmark. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.17550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawte, V.; Chakraborty, S.; Pathak, A.; Sarkar, A.; Tonmoy, S.I.; Chadha, A.; Sheth, A.; Das, A. The troubling emergence of hallucination in large language models-an extensive definition, quantification, and prescriptive remediations. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023.

- Orgad, H.; Toker, M.; Gekhman, Z.; Reichart, R.; Szpektor, I.; Kotek, H.; Belinkov, Y. Llms know more than they show: On the intrinsic representation of llm hallucinations. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.02707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Dodge, J.; Wadden, D.; Huang, M.; Peng, H. Language models hallucinate, but may excel at fact verification. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.14564. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Feng, X.; Feng, X.; Qin, B. The factual inconsistency problem in abstractive text summarization: A survey. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.14839. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Xue, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhao, X.; Wang, K.; Hou, L.; Li, R.; Peng, W. A survey on hallucination in large vision-language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.00253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, N.; Ornik, M.; Driggs-Campbell, K. Hallucination detection in foundation models for decision-making: A flexible definition and review of the state of the art. ACM Computing Surveys 2025, 57, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mündler, N.; He, J.; Jenko, S.; Vechev, M. Self-contradictory hallucinations of large language models: Evaluation, detection and mitigation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.15852. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cui, L.; Cai, D.; Liu, L.; Fu, T.; Huang, X.; Zhao, E.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Siren’s song in the ai ocean: A survey on hallucination in large language models. Computational Linguistics 2025, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.H.; Chen, H.; Babar, M.A. Deep learning for source code modeling and generation: Models, applications, and challenges. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2020, 53, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Shi, L.; Huang, H.; Wang, R.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y. Exploring and evaluating hallucinations in llm-powered code generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.00971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Wang, P.; Xiao, T.; He, T.; Han, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Shou, M.Z. Hallucination of multimodal large language models: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, M.; Borhani Peikani, M. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare: A Survey of Applications in Diagnosis, Treatment, and Patient Monitoring 2024.

- Mohammadabadi, S.M.S.; Seyedkhamoushi, F.; Mostafavi, M.; Peikani, M.B. Examination of AI’s role in Diagnosis, Treatment, and Patient care. In Transforming gender-based healthcare with AI and machine learning; CRC Press, 2024; pp. 221–238.

- Mohammadabadi, S.M.S.; Peikani, M.B. Identification and classification of rheumatoid arthritis using artificial intelligence and machine learning. In Diagnosing Musculoskeletal Conditions using Artifical Intelligence and Machine Learning to Aid Interpretation of Clinical Imaging; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 123–145.

- Kim, Y.; Jeong, H.; Chen, S.; Li, S.S.; Lu, M.; Alhamoud, K.; Mun, J.; Grau, C.; Jung, M.; Gameiro, R.; et al. Medical hallucinations in foundation models and their impact on healthcare. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.05777. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Agarwal, A.; Singla, S. Llms will always hallucinate, and we need to live with this. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.05746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, D.H.; Tran, V.; Nguyen, L.M. Analyzing Logical Fallacies in Large Language Models: A Study on Hallucination in Mathematical Reasoning. In Proceedings of the JSAI International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence. Springer; 2025; pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Y.; Yu, H.; You, J. Beyond Facts: Evaluating Intent Hallucination in Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.06539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Shi, E.; Ma, Y.; Zhong, W.; Chen, J.; Mao, M.; Zheng, Z. Llm hallucinations in practical code generation: Phenomena, mechanism, and mitigation. Proceedings of the ACM on Software Engineering 2025, 2, 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, E.; Salazar, J.Y.; Koerner, R.; Rivas, P.; Cerny, T. Detecting hallucinations in large language model generation: A token probability approach. In Proceedings of the World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering & Applied Computing. Springer; 2024; pp. 154–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S.; Liao, Q.V.; Vorvoreanu, M.; Ballard, S.; Vaughan, J.W. " I’m Not Sure, But...": Examining the Impact of Large Language Models’ Uncertainty Expression on User Reliance and Trust. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, 2024, pp. 822–835.

- Xue, Y.; Greenewald, K.; Mroueh, Y.; Mirzasoleiman, B. Verify when uncertain: Beyond self-consistency in black box hallucination detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.15845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Jiang, K.; Chu, X.; Gulati, S.; Garg, P. Hallucination detection in LLM-enriched product listings. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Seventh Workshop on e-Commerce and NLP@ LREC-COLING 2024, 2024, pp. 29–39.

- Friel, R.; Sanyal, A. Chainpoll: A high efficacy method for llm hallucination detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.18344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadangi, A.; Sartipi, A.; Tchappi, I.; Bahmani, R. Noise Augmented Fine Tuning for Mitigating Hallucinations in Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.03302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Luo, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Yu, S.; Zhang, B.; Cao, J.; Ma, J.; et al. A survey on knowledge-oriented retrieval-augmented generation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.10677. [Google Scholar]

- Dhuliawala, S.; Komeili, M.; Xu, J.; Raileanu, R.; Li, X.; Celikyilmaz, A.; Weston, J. Chain-of-verification reduces hallucination in large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.11495. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrinovics, E.; Biswas, R.; Bjerva, J.; Hose, K. Knowledge graphs, large language models, and hallucinations: An nlp perspective. Journal of Web Semantics 2025, 85, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Liu, Y.; Lin, H.; Lu, Y.; He, B.; Han, X.; Sun, L. Mitigating large language model hallucinations via autonomous knowledge graph-based retrofitting. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 18126–18134.

- Dutta, T.; Liu, X. FaCTQA: Detecting and Localizing Factual Errors in Generated Summaries Through Question and Answering from Heterogeneous Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Jiang, X.; Shi, Z.; Tan, H.; Zhai, X.; Xu, C.; Li, W.; Shen, Y.; Ma, S.; Liu, H.; et al. A survey on llm-as-a-judge. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.15594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dong, Q.; Chen, J.; Su, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ai, Q.; Ye, Z.; Liu, Y. Llms-as-judges: a comprehensive survey on llm-based evaluation methods. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.05579. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Li, T.; Wu, D.; Jenkin, M.; Liu, S.; Dudek, G. Hallucination detection and hallucination mitigation: An investigation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.08358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaraby, M.; Lu, M.; Dunn, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Tian, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Halo: Estimation and reduction of hallucinations in open-source weak large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.11764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manakul, P.; Liusie, A.; Gales, M.J. Selfcheckgpt: Zero-resource black-box hallucination detection for generative large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08896. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Iter, D.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, R.; Zhu, C. G-eval: NLG evaluation using gpt-4 with better human alignment. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.16634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhong, R.; Niu, C. RAG-HAT: A hallucination-aware tuning pipeline for LLM in retrieval-augmented generation. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Industry Track, 2024, pp. 1548–1558.

- Fang, X.; Huang, Z.; Tian, Z.; Fang, M.; Pan, Z.; Fang, Q.; Wen, Z.; Pan, H.; Li, D. Zero-resource hallucination detection for text generation via graph-based contextual knowledge triples modeling. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2025, Vol. 39, pp. 23868–23877.

- Sun, Z.; Zang, X.; Zheng, K.; Song, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Yu, W.; Li, H. Redeep: Detecting hallucination in retrieval-augmented generation via mechanistic interpretability. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.11414. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shi, L.; Wang, K.; Wang, H. Drowzee: Metamorphic testing for fact-conflicting hallucination detection in large language models. Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 2024, 8, 1843–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Wang, C.; Ai, Q.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Unsupervised real-time hallucination detection based on the internal states of large language models. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2403.06448. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Fei, H.; Pan, L.; Wang, W.Y.; Yan, S.; Chua, T.S. Combating Multimodal LLM Hallucination via Bottom-Up Holistic Reasoning. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2025, Vol. 39, pp. 8460–8468.

- Gunjal, A.; Yin, J.; Bas, E. Detecting and preventing hallucinations in large vision language models. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 18135–18143.

- Sırt, M.; Eyüpoğlu, C. A User-Friendly and Explainable Framework for Redesigning AutoML Processes with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2025 33rd Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU). IEEE; 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.Z.; Ma, J.; Zhang, X.; Hao, N.; Yan, A.; Nourbakhsh, A.; Yang, X.; McAuley, J.; Petzold, L.; Wang, W.Y. A survey on large language models for critical societal domains: Finance, healthcare, and law. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.01769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyanarayana, S.V.; Shah, R.; Hiremath, S.D.; Panda, R.; Jana, R.; Singh, R.; Irfan, R.; Murali, A.; Ramsundar, B. DeepRetro: Retrosynthetic Pathway Discovery using Iterative LLM Reasoning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.07060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Chen, C.; Xu, X.; Payani, A.; Shu, K. Can Knowledge Editing Really Correct Hallucinations? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.16251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Bau, D.; Andonian, A.; Belinkov, Y. Locating and editing factual associations in gpt. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 17359–17372. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, K.; Sharma, A.S.; Andonian, A.; Belinkov, Y.; Bau, D. Mass-editing memory in a transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.07229. [Google Scholar]

- Madaan, A.; Tandon, N.; Gupta, P.; Hallinan, S.; Gao, L.; Wiegreffe, S.; Alon, U.; Dziri, N.; Prabhumoye, S.; Yang, Y.; et al. Self-refine: Iterative refinement with self-feedback. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 46534–46594. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, Y.S.; Xie, Y.; Luo, H.; Kim, Y.; Glass, J.; He, P. Dola: Decoding by contrasting layers improves factuality in large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.03883. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Han, X.; Lewis, M.; Tsvetkov, Y.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Yih, W.t. Trusting your evidence: Hallucinate less with context-aware decoding. Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 2: Short Papers), 2024, pp. 783–791.

- Li, K.; Patel, O.; Viégas, F.; Pfister, H.; Wattenberg, M. Inference-time intervention: Eliciting truthful answers from a language model. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 41451–41530. [Google Scholar]

- Amatriain, X. Measuring and mitigating hallucinations in large language models: amultifaceted approach, 2024.

- Rejeleene, R.; Xu, X.; Talburt, J. Towards trustable language models: Investigating information quality of large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.13086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bubeck, S.; Eldan, R.; Del Giorno, A.; Gunasekar, S.; Lee, Y.T. Textbooks are all you need ii: phi-1.5 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.05463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, M.; Aneja, J.; Behl, H.; Bubeck, S.; Eldan, R.; Gunasekar, S.; Harrison, M.; Hewett, R.J.; Javaheripi, M.; Kauffmann, P.; et al. Phi-4 technical report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.08905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, H.; Li, M.; Honavar, V.G. Cal-dpo: Calibrated direct preference optimization for language model alignment. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 114289–114320. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Li, G.; Xu, X.; Kan, M.Y. V-dpo: Mitigating hallucination in large vision language models via vision-guided direct preference optimization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.02712. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Kan, Z.; Cheng, K.; Hu, L.; Wang, D. Locate-then-edit for multi-hop factual recall under knowledge editing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.06331. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Song, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Shi, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H. Detecting LLM Fact-conflicting Hallucinations Enhanced by Temporal-logic-based Reasoning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13416. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Deng, H.; Ou, J.; Feng, C. Mitigating spatial hallucination in large language models for path planning via prompt engineering. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 8881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaat, A.; Wong, A.; Verberne, S.; Broekens, J.; van Stein, N.; Back, T. Reasoning with large language models, a survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.11511. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, F.; Huang, Z.; Liu, C.; Sun, Q.; Yang, H.; Lim, S.N. Intervening anchor token: Decoding strategy in alleviating hallucinations for MLLMs. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Hilton, J.; Evans, O. Truthfulqa: Measuring how models mimic human falsehoods. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.07958. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Saxon, M.; Xu, W.; Nathani, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.Y. Automatically correcting large language models: Surveying the landscape of diverse self-correction strategies. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.03188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Chiang, W.L.; Sheng, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Xing, E.; et al. Judging llm-as-a-judge with mt-bench and chatbot arena. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 46595–46623. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, B.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Mei, L.; Gao, H.; Fang, J.; Cheng, X. Struedit: Structured outputs enable the fast and accurate knowledge editing for large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.10132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Detection Paradigm | Core Principle | Key Methods/Papers | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White-box | Internal State Analysis | Hidden-state activations reveal hallucinations | INSIDE (EigenScore), SAPLMA, OPERA, DoLa | Direct mechanistic signal | Requires full model access; model-specific |

| Grey-box | Uncertainty Quantification | Low confidence = likely hallucination | Token/sequence probability, Semantic entropy, LLM-Check | Efficient; accessible via logits | Probabilistic assumptions may fail; needs API logits access |

| Black-box | Consistency Checking | Hallucinations vary across outputs | SelfCheckGPT, LM-vs-LM, Multi-Agent Debate | Model-agnostic; any API-accessible model | Expensive (multiple calls); fails if model consistently hallucinates |

| Lifecycle Stage | Core Principle | Representative Techniques | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Centric (Pre-Training) | Improve factual quality of training data to reduce hallucination at the source. | High-quality data curation; retrieval-augmented pre-training (e.g., RETRO [55]). | Reduces hallucination fundamentally; better internal grounding. | High computational cost; limited by source quality; difficult to scale. |

| Model-Centric (Fine-Tuning & Alignment) | Align model parameters with factual knowledge and human preferences. | Supervised fine-tuning (SFT); RLHF; DPO; knowledge editing (ROME [56,57], MEMIT [58]). | Enables steerability and surgical correction; enhances safety. | Requires human preference data; risk of forgetting; unstable optimization. |

| Inference-Time | Guide generation with external evidence or real-time reasoning. | Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG); self-refinement (CoVe [36], Self-Refine [59]); decoding control (DoLa [60], CAD [61]); ITI [62]. | Model-agnostic; low deployment barrier; can use live information. | Latency overhead; tool quality bottleneck; limited correction for internal errors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).