Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition and Classification of Environmental Quality

1.2. The Seven Major Petrochemical Port Cities in China

1.3. Research on Environmental Quality in Petrochemical Port Cities

2. Methods

2.1. Information Source Identification

2.2. Data Preprocessing

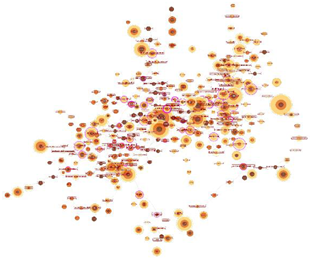

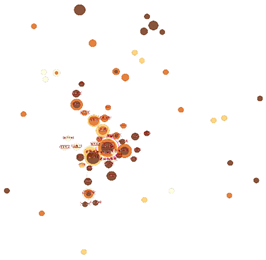

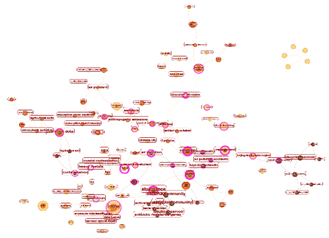

2.3. Visual Analytics

3. Discussion and Analysis

3.1. Research Focus Across Different City Tiers

3.2. Analytical Framework for Semantic Ontology Data Modeling

3.2.1. Semantic Ontology Model for Atmospheric Environments

3.2.2. Semantic Ontology Model for Aquatic Environments

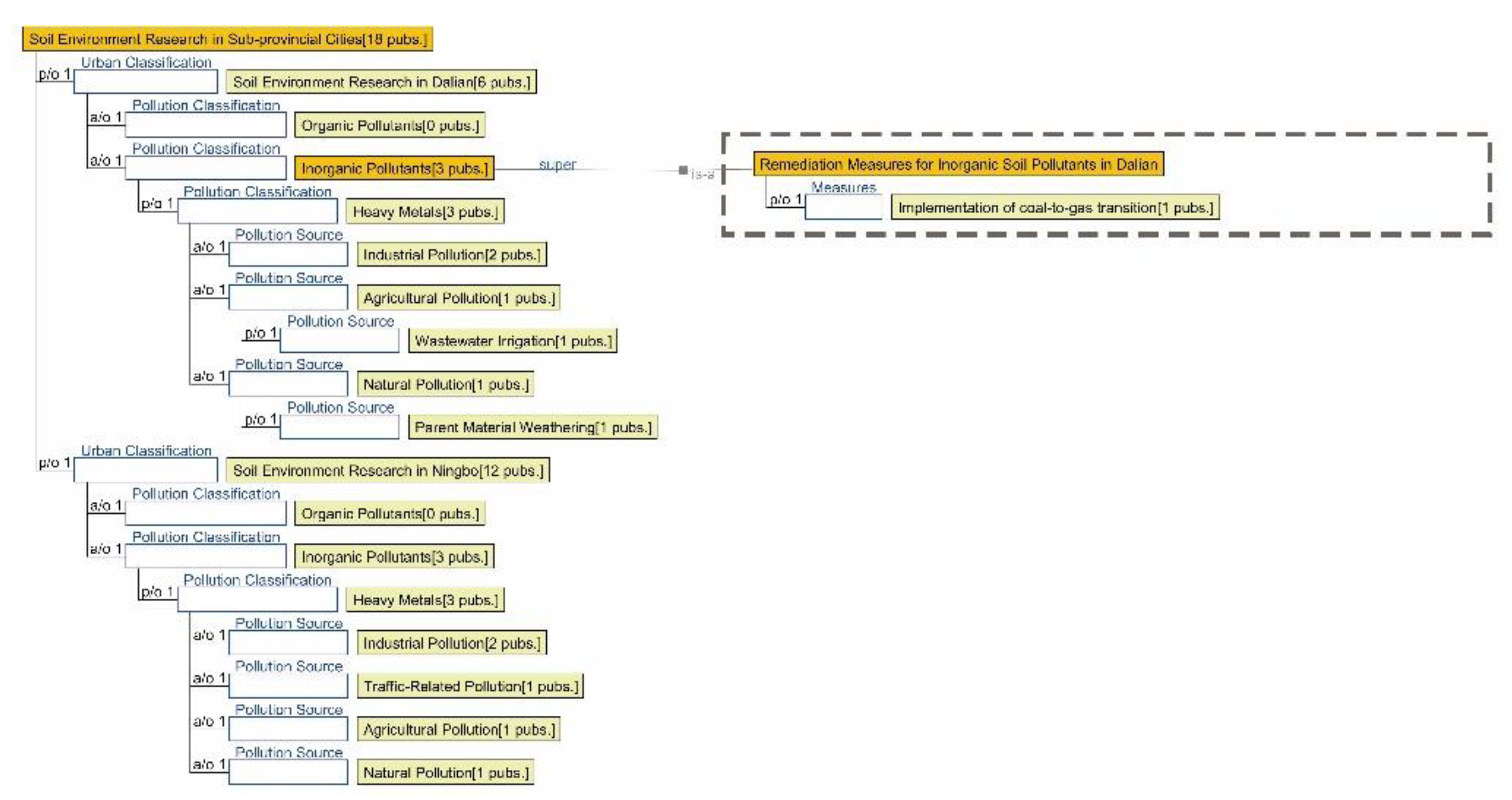

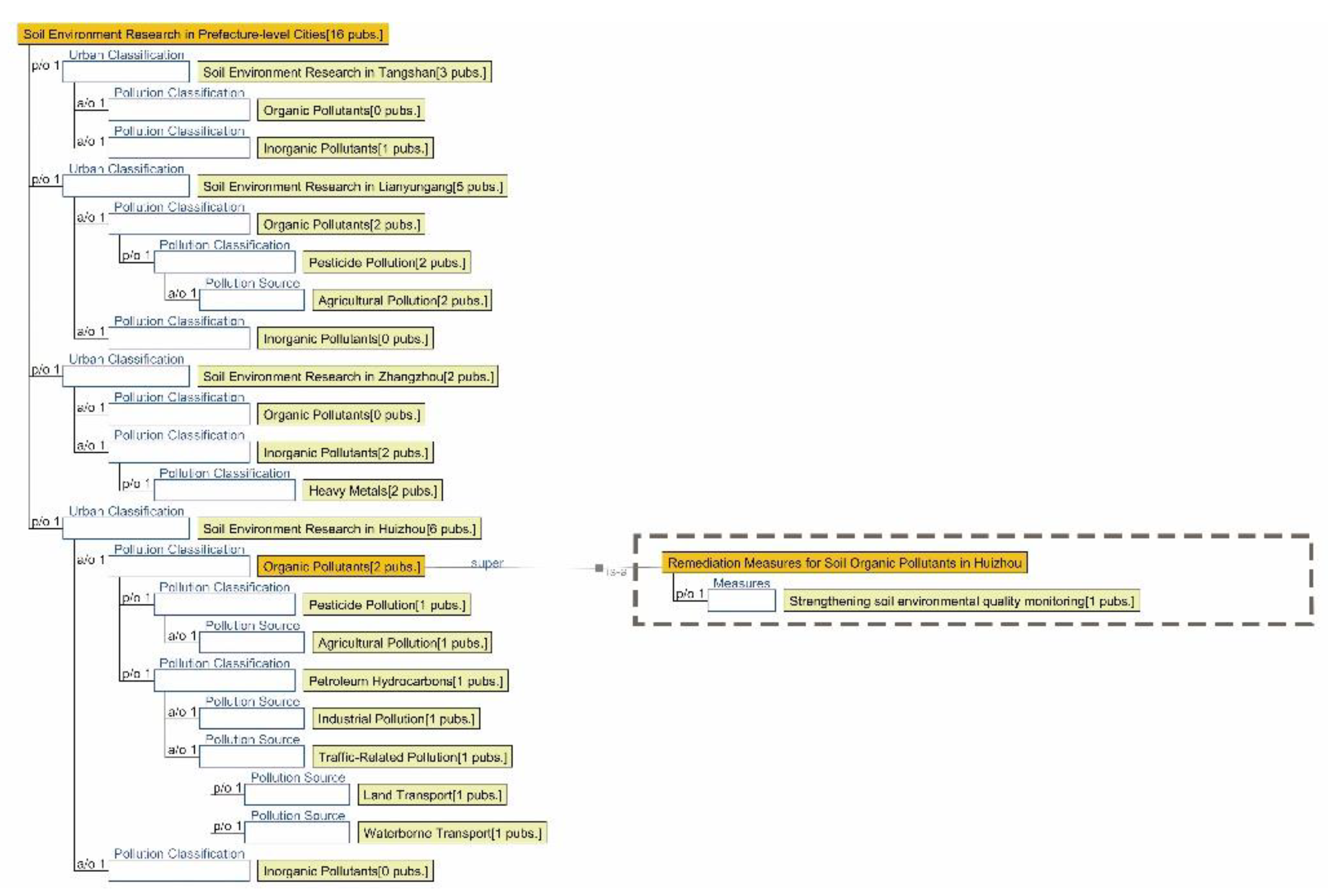

3.2.3. Semantic Ontology Model for Soil Environment

3.2.4. Semantic Ontology Model for Biological Environments

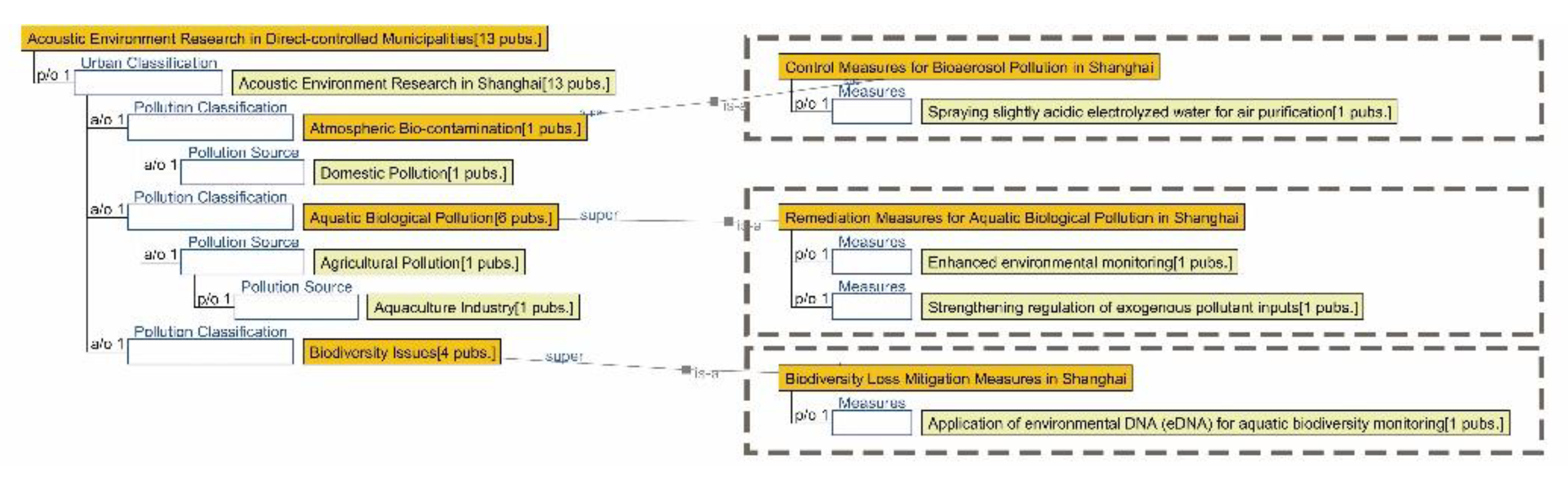

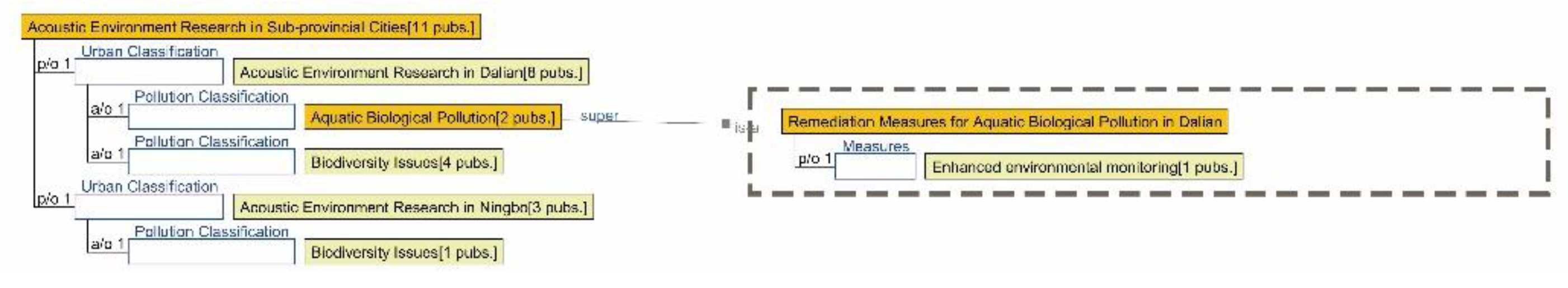

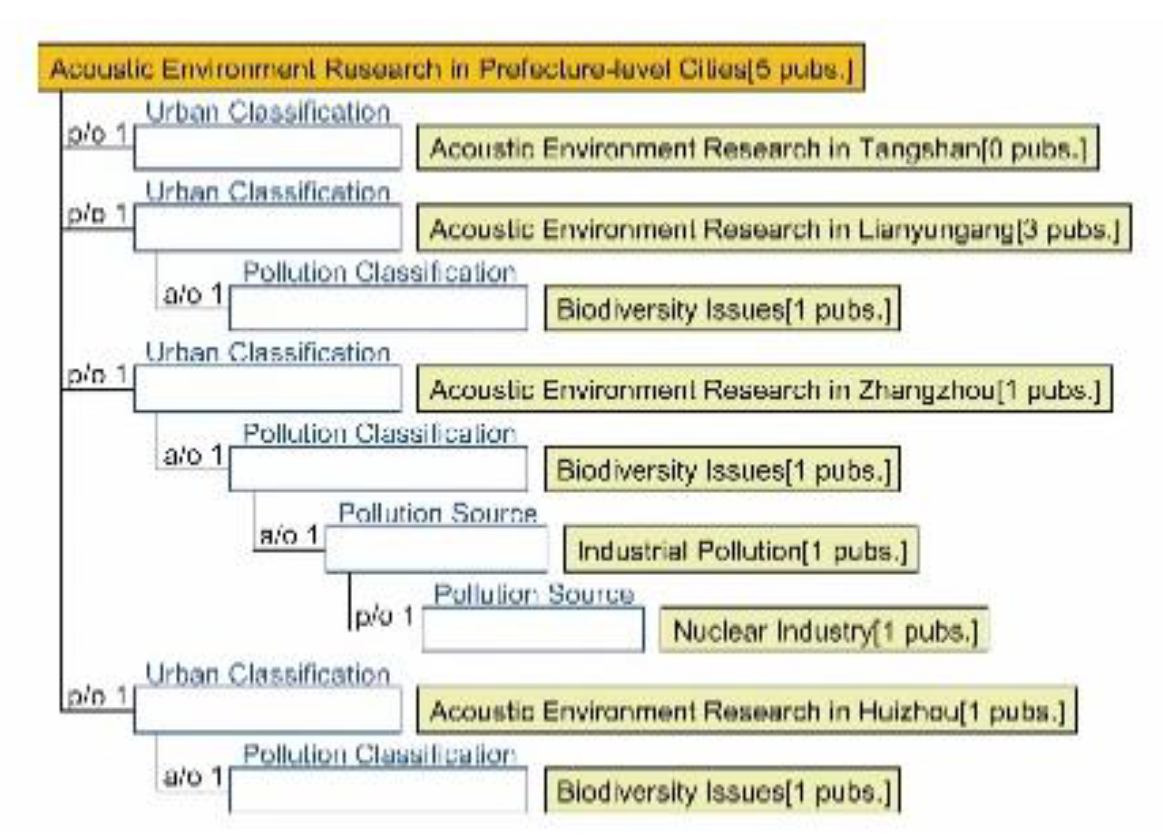

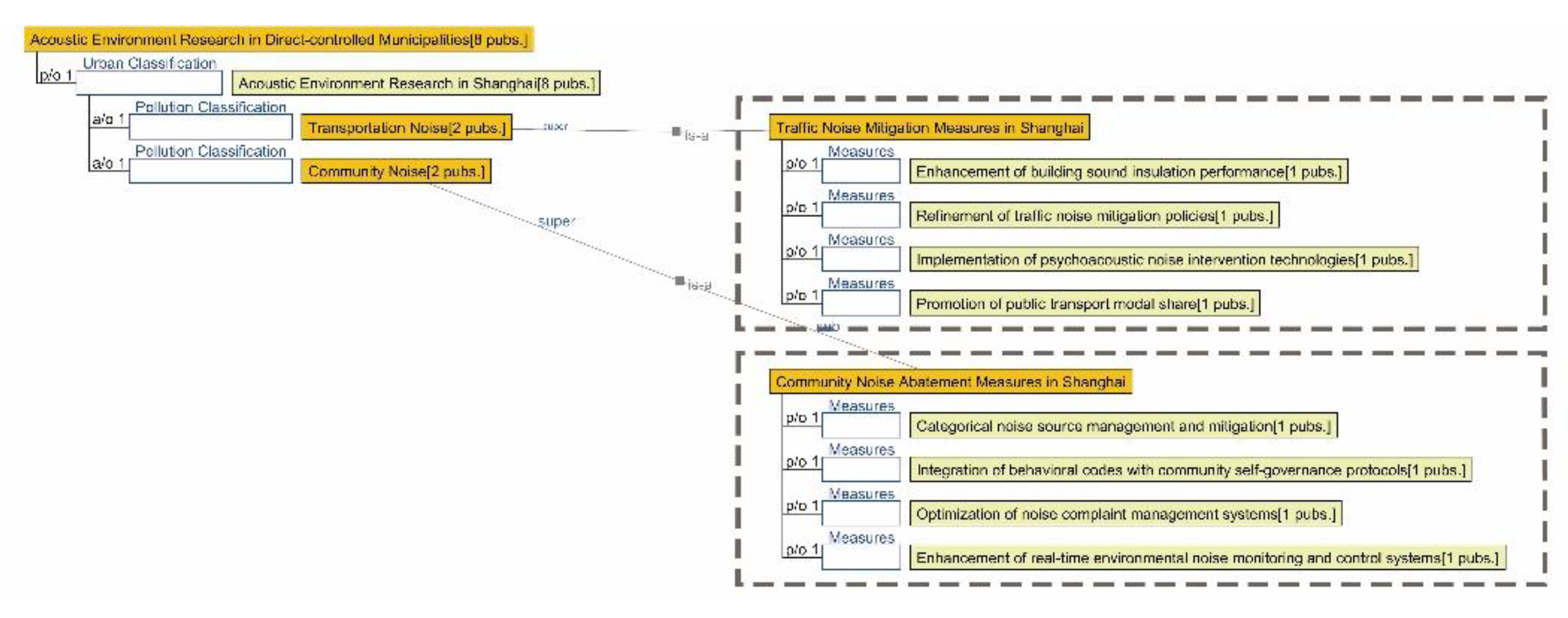

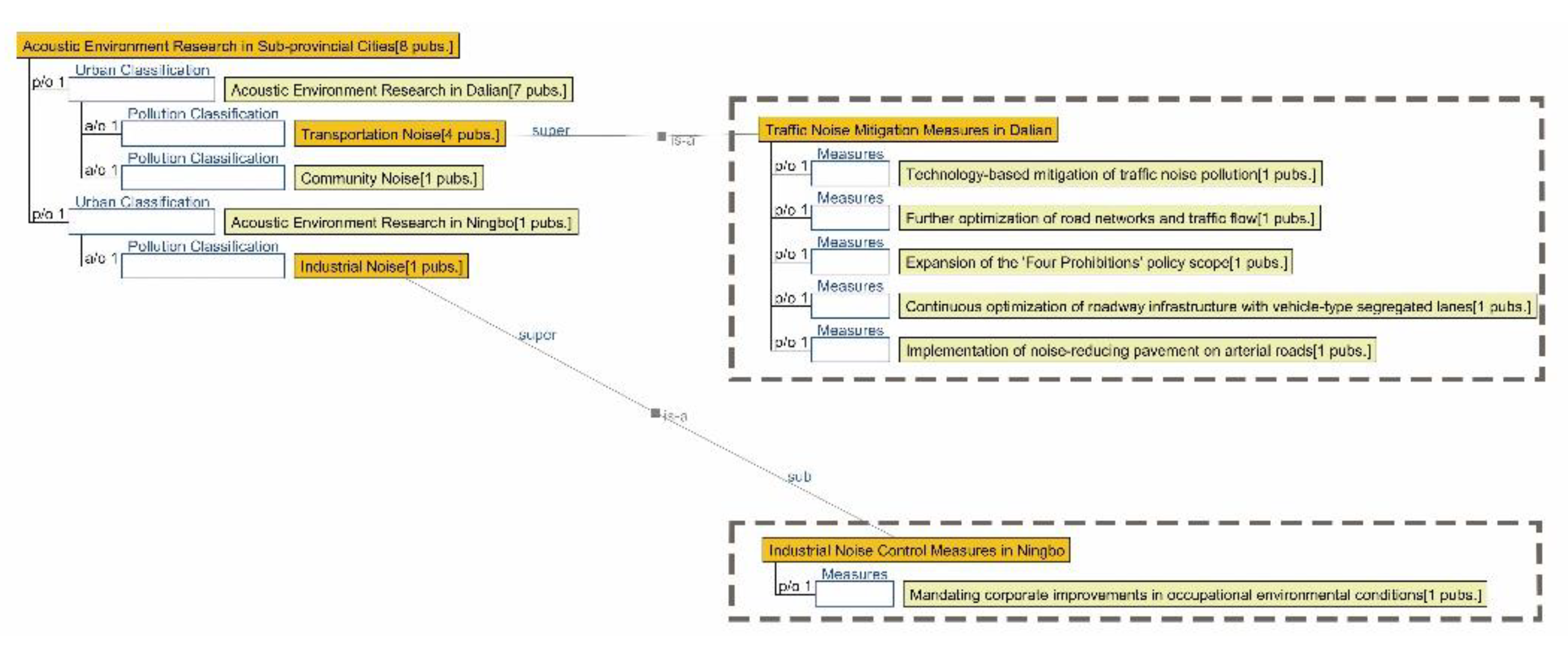

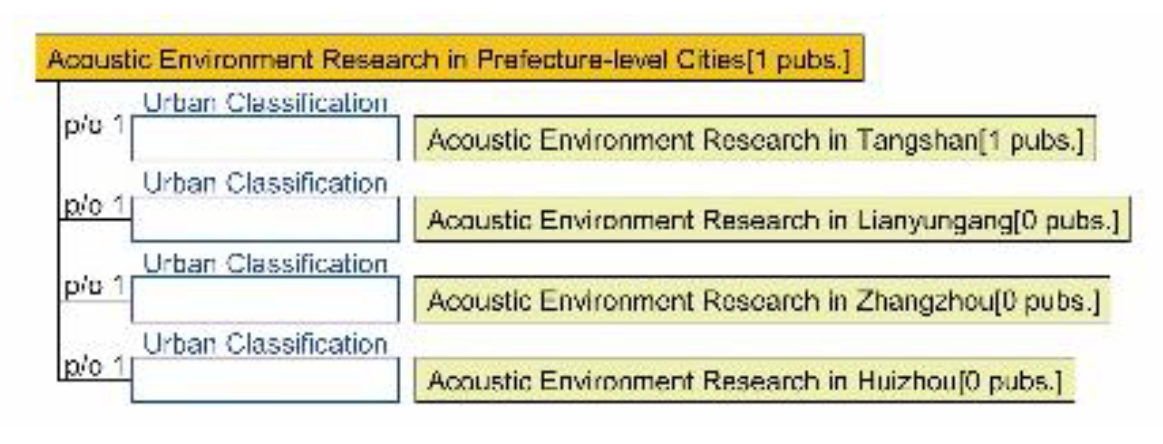

3.2.5. Semantic Ontology Model for Acoustic Environment

4. Conclusions

4.1. Summary of Existing Research

4.1.1. Research Summary on Air Quality in Seven Major Chinese Petrochemical Port Cities (Past Three Years)

4.1.2. Research Summary on Aquatic Environment Quality in Seven Major Chinese Petrochemical Port Cities (Past Three Years)

4.1.3. Research Summary on Soil Environment Quality in Seven Major Chinese Petrochemical Port Cities (Past Three Years)

4.1.4. Research Summary on Biological Environment Quality in Seven Major Chinese Petrochemical Port Cities (Past Three Years)

4.1.5. Research Summary on Acoustic Environment Quality in Seven Major Chinese Petrochemical Port Cities (Past Three Years)

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.2.1. Limitations of the Study

4.2.2. Future Research Directions

Acknowledgments

References

- China Petroleum and Chemical Industry Federation: Petrochemical Industry Revenue Achieves Positive Growth. https://chinanpo.mca.gov.cn/xwxq?id=28032&newsType=1947,1943,1948 (accessed 2025-08-31).

- Introduction to Environmental Science (Fang, S.-R.; Yao, H.) (Z-Library) (1).

- Tian, C.; Liang, Y.; Lin, Q.; You, D.; Liu, Z. Environmental Pressure Exerted by the Petrochemical Industry and Urban Environmental Resilience: Evidence from Chinese Petrochemical Port Cities. J. Cleaner Prod. 2024, 471, 143430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143430. [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Chen, J.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, P. Research on the High-Quality Development Strategy of the Petrochemical Industry. Strategic Study of CAE 2021, *23* (5), 122–129.

- Dai, H.; Chen, J.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, P. Research on the Green and Low-Carbon Transformation Development of China’s Chemical and Petrochemical Industry. Strategic Study of CAE 2024, *26* (6), 223–232.

- Li, Z. A Study on Human Behavior in the Waterscape Space of a Residential Complex in China. Ph.D. Dissertation, Kyoto University, 2009.

- Wang, Y.; Dai, X.; Gong, D.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, H.; Ma, W. Correlations between Urban Morphological Indicators and PM2.5 Pollution at Street-Level: Implications on Urban Spatial Optimization. Atmosphere 2024, 15 (3), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15030341. [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, N.; Zhu, P.; Yan, J.; Yin, S. Sequential Interaction of Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds and SOAs in Urban Forests Revealed Using Toeplitz Inverse Covariance-Based Clustering and Causal Inference. Forests 2023, 14 (8), 1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14081617. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Duan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y. How Can Trees Protect Us from Air Pollution and Urban Heat? Associations and Pathways at the Neighborhood Scale. Landscape Urban Plann. 2023, 236, 104779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104779. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lyu, J.; Chen, W. Y.; Chen, D.; Yan, J.; Yin, S. Quantifying the Capacity of Tree Branches for Retaining Airborne Submicron Particles. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 310, 119873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119873. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, J. Comprehensive Economic Impact Assessment of Regional Shipping Emissions: A Case Study of Shanghai, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 211, 117368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.117368. [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Chen, J.; Wen, H.; Wan, Z.; Tang, T. Emissions Assessment of Bulk Carriers in China’s East Coast-Yangtze River Maritime Network Based on Different Shipping Modes. Ocean Eng. 2022, 249, 110903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.110903. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xiang, J.; Lv, J. Analysis of Air Quality in a Typical Mountainous County/City in Eastern China—A Case Study of Xinchang County. Energy Conservation and Environmental Protection 2022, No. 3, 44–46.

- Šabanovič, A.; Matijošius, J.; Marinković, D.; Chlebnikovas, A.; Gurauskis, D.; Gutheil, J. H.; Kilikevičius, A. Experimental Setup and Machine Learning-Based Prediction Model for Electro-Cyclone Filter Efficiency: Filtering of Ship Particulate Matter Emission. Atmosphere 2025, 16 (1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16010103. [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Shan, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Deciphering Urban Traffic Impacts on Air Quality by Deep Learning and Emission Inventory. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 124, 745–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2021.12.035. [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Bao, Z.; Thomas Ng, S.; Song, W. Estimating the Effect of Air Quality on Bike-Sharing Usage in Shanghai, China: An Instrumental Variable Approach. Travel Behav. Soc. 2023, 33, 100626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2023.100626. [CrossRef]

- Ting, Y.-C.; Ku, C.-H.; Zou, Y.-X.; Chi, K.-H.; Soo, J.-C.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C. Characteristics and Source-Specific Health Risks of Ambient PM2.5-Bound PAHs in an Urban City of Northern Taiwan. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2023, 23 (11), 230092. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.230092. [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Sun, W.; Wang, S.; Zou, S. Analyzing the Sources of PM2.5 at a State-Controlled Atmospheric Monitoring Substation in Dalian City Using Big Data. Science & Technology Information 2023, *21* (6), 87–90. https://doi.org/10.16661/j.cnki.1672-3791.2208-5042-7257. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Gao, X.; Yan, H.; Guo, L.; Zhang, H.; Ran, Z. Temporal and Spatial Distribution Characteristics of PM2.5 and Their Relationship with Meteorological Conditions in the Coastal Area of Lianyungang. Technology Innovation and Application 2022, *12* (6),73–75. https://doi.org/10.19981/j.CN23-1581/G3.2022.06.020. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, W. Analysis of Ambient Air Quality Changes and Improvement Measures in Lianyungang City During the “13th Five-Year Plan” Period. Shandong Chemical Industry 2022, *51* (4), 219–220,223. https://doi.org/10.19319/j.cnki.issn.1008-021x.2022.04.038.https://doi.org/10.19319/j.cnki.issn.1008-021x.2022.04.038. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Gao, B.; Cui, S.; Ding, L.; Wang, L.; Shen, Y. Regional Differences in PM2.5 Environmental Efficiency and Its Driving Mechanism in Zhejiang Province, China. Atmosphere 2023, 14 (4), 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos14040672. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, C.; Yu, W.; Yin, Y.; Han, D.; Li, S.; Kuang, J. Heterogeneity Environmental Regulation and Provincial Haze Pollution in China: An Empirical Study Based on Threshold Model. Environ. Dev. Sustainability 2023, 25 (12), 14715–14732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02685-w. [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, S.; Tu, X.; Ahmad, K.; Qadeer, A. A Real-Time Assessment of Hazardous Atmospheric Pollutants across Cities in China and India. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 479, 135711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.135711. [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Zhou, D.; Bai, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Duan, H.; Zhang, W. Quantification of the Carbon Emission of Urban Residential Buildings: The Case of the Greater Bay Area Cities in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 95, 106775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2022.106775. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, K.; Liu, D.; Yang, Y.; Wu, D. Estimating the Carbon Emission of Construction Waste Recycling Using Grey Model and Life Cycle Assessment: A Case Study of Shanghai. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19 (14), 8507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148507. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, C. How Does the “Zero-Waste City” Strategy Contribute to Carbon Footprint Reduction in China? Waste Management 2023, 156, 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2022.11.032. [CrossRef]

- Liao, N.; Bolyard, S. C.; Lü, F.; Yang, N.; Zhang, H.; Shao, L.; He, P. Can Waste Management System Be a Greenhouse Gas Sink? Perspective from Shanghai, China. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2022, 180, 106170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106170. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Md. A.; Assiri, M. E.; Islam, M. N.; Bilal, M.; Ghulam, A.; Huang, Z. Identification of NO2 and SO2 over China: Characterization of Polluted and Hotspots Provinces. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2024, 17 (10), 2203–2221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-024-01565-8. [CrossRef]

- Hua, E.; Sun, R.; Feng, P.; Song, L.; Han, M. Optimizing Onshore Wind Power Installation within China via Geographical Multi-Objective Decision-Making. Energy 2024, 307, 132431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.132431. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, S.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, L.; Liu, M.; Cao, C.; Xia, Y.; Gao, J. Cooking-Related Thermal Comfort and Carbon Emissions Assessment: Comparison between Electric and Gas Cooking in Air-Conditioned Kitchens. Build. Environ. 2024, 265, 111992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2024.111992. [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Walls, W. D.; Zheng, X.; Li, G. Evaluating Environmental Benefits from Driving Electric Vehicles: The Case of Shanghai, China. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 119, 103749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2023.103749. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Choma, E. F. Health Benefits of Vehicle Electrification through Air Pollution in Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169859. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, J.; Gu, C.; Sun, Z.; Xue, R.; Zhou, B. A New Portable Open-Path Instrument for Ambient NH3 and on-Road Emission Measurements. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 136, 606–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2023.01.017. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Lv, S.; Wang, F.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Du, W.; Liu, S.; Zhang, F.; Li, J.; Meng, J.; Wang, G. Ammonia in Urban Atmosphere Can Be Substantially Reduced by Vehicle Emission Control: A Case Study in Shanghai, China. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2023, 126, 754–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2022.04.043. [CrossRef]

- Ji, A.; Guan, J.; Zhang, S.; Ma, X.; Jing, S.; Yan, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, H. Environmental and Economic Assessments of Industry-Level Medical Waste Disposal Technologies–a Case Study of Ten Chinese Megacities. Waste Manage. (Oxford) 2024, 174, 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2023.11.036. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z. Quantitative Analysis of Sulfur Dioxide Emissions in the Yangtze River Economic Belt from 1997 to 2017, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19 (17), 10770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710770. [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Dong, W.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, J. Identification of Priority Pollutants at an Integrated Iron and Steel Facility Based on Environmental and Health Impacts in the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 115464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115464. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Guo, B.; Qie, F.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Rong, J.; Zong, B. A Sustainable Integration of Removing CO2/NO and Producing Biomass with High Content of Lipid/Protein by Microalgae. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 73, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2022.04.008. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Bai, X.; Tian, J. Study on the Impact of Electric Power and Thermal Power Industry of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region on Industrial Sulfur Dioxide Emissions—from the Perspective of Green Technology Innovation. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 837–849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.02.039. [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Qian, X.; Huang, J.; Li, G.; Guo, X. A Mediation Analysis of Meteorological Factors on the Association between Ambient Carbon Monoxide and Tuberculosis Outpatients Visits. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1526325. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1526325. [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Liu, C.; Lin, J.; Tan, W.; Liu, T. VOCs Hyperspectral Imaging: A New Insight into Evaluate Emissions and the Corresponding Health Risk from Industries. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 461, 132573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132573. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, K.; He, W. Research on Real-Time Self-Calibration Method for SO2 UV Cameras. Acta Optica Sinica 2023, *43* (12), 1228005. https://doi.org/10.3788/AOS221512. [CrossRef]

- Shifting from End-of-Pipe Supervision to Whole-Process Control: Effectively Enhancing the Level of Atmospheric Environmental Governance—Ningbo Municipal Bureau of Ecology and Environment, Zhenhai Branch. Ningbo Communications 2023, No. 8, 74–75.

- Sun, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z. Collaborative Governance of Air Pollution Caused by Energy Consumption in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration under Low-Carbon Constraints: Efficiency Measurement and Spatial Empirical Testing. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2023, 234 (9), 566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-023-06579-z. [CrossRef]

- Xie, S. Research on Ozone Characteristics and Control Strategy Methods in Longwen District, Zhangzhou City, Fujian Province. Ecology and Resources 2024, No. 12, 22–24.

- Zhao, S.; Zhao, D.; Song, Q. Comparative Lifecycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Their Reduction Potential for Typical Petrochemical Enterprises in China. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 116, 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2021.05.031. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, S. Green Total Factor Productivity Measurement of Industrial Enterprises in Zhejiang Province, China: A DEA Model with Undesirable Output Approach. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.05.094. [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Hou, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Lu, M.; Liu, X.; Yao, Z. Pollution Characteristics and Ecological Impact of Screening Analysis of Fishing Port Sediments from Dalian, North China. Environ. Health 2024, 2 (10), 702–711. https://doi.org/10.1021/envhealth.4c00042. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, K.; Yang, M.; Lu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, L.; Qian, M.; Shi, L. Screening of Priority Pollutants and Discussion on Coordinated Monitoring in the Yangtze River Delta Eco-Green Integration Demonstration Zone. Resources and Environment in the Yangtze Basin 2022, *31* (2), 358–365.

- Huang, M. Water Quality Assessment and Pollution Prevention Countermeasures for Huashanxi in Pinghe County. Strait Science 2024, No. 3, 80–83.

- Hu, L.; Jia, G.; Zhang, L. Water Quality Assessment and Pollution Characteristic Analysis of Reservoir-Type Water Sources in Dalian City. Green Science and Technology 2024, *26* (12), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.16663/j.cnki.lskj.2024.12.039. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J. Comprehensive Evaluation and Analysis of Water Environmental Quality in Major River Systems in the Shanghai Area. Design of Water Resources & Hydropower Engineering 2025, *44* (1), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.20275/j.cnki.issn.1007-6980.2025.01.003. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, X.; Qiao, X. Multimedia Fate Simulation of Mercury in a Coastal Urban Area Based on the Fugacity/Aquivalence Method. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170084. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, H.; Gan, S.; Sun, R.; Zheng, Y.; Craig, N. J.; Sheng, W.; Li, J.-Y. Antibiotics and Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals in Effluent from Wastewater Treatment Plants of a Mega-City Affected the Water Quality of Juvenile Chinese Sturgeon Habitat: Upgrades to Wastewater Treatment Processes Are Needed. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2025, 215, 117840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.117840. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jin, W.; Zhang, W.; Hu, F.; Ye, J. Research on Comprehensive Treatment of Rural Domestic Sewage in China. Strategic Study of CAE 2022, *24* (5), 154–160. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jiang, L.; Xue, S. Analysis of Influent Fluctuation and Operation Strategy of a Wastewater Treatment Plant in Shanghai During the Silent Management Period. China Water & Wastewater 2022, *38* (19), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.19853/j.zgjsps.1000-4602.2022.19.001. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Ye, H.; Huang, X.; Yang, G.; Cai, Y. Comparison of the Capacity and Characteristics of Representative Floating Plants for Removing Heavy Metals in Phytoremediation. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology 2022, *17* (3), 316–325.

- Shi, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Wu, D.; Lou, X.; Cai, Y. Study on the Prevention and Remediation Effect of Floating Plants on Heavy Metal Pollution in Freshwater Aquatic Products—Using Silver Crucian Carp as a Model. Quality and Safety of Agro-Products 2022, No. 1, 83–89.

- Liu, S.; Sun, F.; Ji, Y. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Distribution of Suspended Solids and Tidal Influence in Shanghai’s Major Rivers and Lakes. Water Resources Protection 2025, *41* (1), 178–185.

- Jiang, L.; Chen, M.; Huang, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhao, J.; Chan, F.; Yu, X. Effects of Different Treatment Processes in Four Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants on the Transport and Fate of Microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154946. [CrossRef]

- Perez, C. N.; Carré, F.; Hoarau-Belkhiri, A.; Joris, A.; Leonards, P. E. G.; Lamoree, M. H. Innovations in Analytical Methods to Assess the Occurrence of Microplastics in Soil. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10 (3), 107421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2022.107421. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Wang, H.; Yu, D.; Song, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y. Basic Data Platform for Environmental Capacity and Carrying Capacity Calculation of Soil Organic Pollutants in Ningbo. Journal of Agro-Environment Science 2024, *43* (11), 2604–2614.

- Guo, Y.; Lin, K.; Gao, X.; Zheng, Q.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, Y. Disinfection Efficacy of Slightly Acidic Electrolyzed Water on Microorganisms: Application in Contaminated Waste Sorting Rooms across Varied Scenarios. J. Cleaner Prod. 2024, 467, 142938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142938. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ling, L.; Tan, J.; Lin, X.; Wang, H.; Sun, B.; Li, Z. Challenges, Breakthroughs, and Prospects of Environmental DNA Technology in Aquatic Biological Monitoring. Journal of Shanghai Ocean University 2023, *32* (3), 564–574.

- Hu, L.; Xue, J.; Wu, H. Composition and Distribution of Bacteria, Pathogens, and Antibiotic Resistance Genes at Shanghai Port, China. Water 2024, 16 (18), 2569. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16182569. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Shen, X. Monitoring, Evaluation, and Prevention Measures of Road Traffic Noise in Areas Outside the Central Urban District of Dalian. Environmental Protection and Circular Economy 2023, *43* (3), 62–64.

- Zhou, Y. Practice of Urban Acoustic Environmental Protection—A Case Study of Environmental Noise Control in Shanghai. China Environmental Protection Industry 2022, No. 6, 25–29.

- Duan, D.; Leng, P.; Li, X.; Mao, G.; Wang, A.; Zhang, D. Characteristics and Occupational Risk Assessment of Occupational Silica-Dust and Noise Exposure in Ferrous Metal Foundries in Ningbo, China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1049111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1049111. [CrossRef]

Municipality directly under the central government (WOS) |

Municipality directly under the central government (CNKI) |

Sub-provincial level city (WOS) |

Sub-provincial level city (CNKI) |

Prefecture-level City (WOS) |

Prefecture-level City (CNKI) |

| Keywords | Centrality | Count | Keywords | Centrality | Count |

| Ecosystem services | 0.42 | 13 | Policy | 0.16 | 33 |

| Generation | 0.27 | 7 | Influencing factors | 0.16 | 15 |

| Economic growth | 0.26 | 12 | Yangtze river economic belt | 0.16 | 10 |

| Financial constraints | 0.24 | 4 | Public attention | 0.16 | 3 |

| Design | 0.22 | 7 | Sustainable development | 0.15 | 31 |

| Particulate matter [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.20 | 22 | Corporate governance | 0.15 | 18 |

| Drivers | 0.20 | 3 | Areas | 0.15 | 11 |

| Responsibility | 0.19 | 20 | Resolution | 0.15 | 5 |

| Energy consumption | 0.19 | 11 | Haze [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.15 | 3 |

| PM2.5 concentrations [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.19 | 3 | Deep learning | 0.14 | 10 |

| Life cycle assessment | 0.18 | 22 | Aerosol [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.14 | 6 |

| Trends | 0.18 | 15 | Social responsibility | 0.13 | 17 |

| Chemistry | 0.18 | 5 | Deposition | 0.13 | 6 |

| Municipal solid waste | 0.17 | 6 | Media attention | 0.13 | 3 |

| Exposure | 0.16 | 35 | Challenges | 0.13 | 2 |

| Keywords | Centrality | Count | Keywords | Centrality | Count |

| 上海(Shanghai) | 0.18 | 16 | 重金属(Heavy metals) | 0.02 | 5 |

| 水环境(Water environment) [Aquatic Environment] |

0.08 | 8 | 水质评价(Water quality assessment) [Aquatic Environment] |

0.02 | 5 |

| 土壤(Soil) [Soil Environment] |

0.07 | 6 | 上海市(Shanghai) | 0.02 | 2 |

| 地下水(Groundwater) [Aquatic Environment] |

0.04 | 5 | 发展环境(Development environment) | 0.02 | 1 |

| 养殖(Aquaculture) | 0.04 | 1 | 发布特征(Emission characteristics) | 0.01 | 2 |

| 幼蟹(Juvenile crabs) | 0.03 | 2 | 评估(Assessment) | 0.01 | 2 |

| 土壤污染(Soil pollution) [Soil Environment] |

0.03 | 1 | 工业地块(Industrial sites) | 0.01 | 2 |

| 空气质量(Air quality) [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.02 | 9 | 绿色经济(Green economy) | 0.01 | 2 |

| 水质(Water quality) [Aquatic Environment] |

0.02 | 7 | 浮水植物(Floating aquatic plants) | 0.01 | 2 |

| Keywords | Centrality | Count | Keywords | Centrality | Count |

| Satisfaction | 0.42 | 4 | Identification | 0.17 | 8 |

| Energy consumption | 0.37 | 4 | Diversity | 0.17 | 3 |

| Pollution | 0.34 | 10 | China | 0.16 | 6 |

| Quality | 0.33 | 8 | Performance | 0.15 | 16 |

| Catalyst | 0.31 | 6 | Evolution | 0.14 | 7 |

| Removal | 0.26 | 4 | Fabrication | 0.14 | 2 |

| Particulate matter [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.22 | 7 | Degradation | 0.14 | 2 |

| Source apportionment | 0.21 | 6 | Hydrogenation | 0.14 | 2 |

| Energy | 0.20 | 15 | Water quality [Aquatic Environment] |

0.13 | 2 |

| Impact | 0.20 | 11 | Model | 0.12 | 10 |

| Life cycle assessment | 0.20 | 4 | Carbon | 0.12 | 2 |

| Environmental impacts | 0.20 | 2 | Catalysts | 0.11 | 7 |

| Nanosheets | 0.19 | 6 | Air source heat pump | 0.11 | 1 |

| Long term exposure | 0.19 | 2 | Emissions | 0.09 | 4 |

| 15System | 0.17 | 9 | 30Environment | 0.09 | 3 |

| Keywords | Centrality | Count | Keywords | Centrality | Count |

| 宁波(Ningbo) | 0.02 | 7 | 协同治理(Collaborative governance) | 0.01 | 2 |

| Keywords | Centrality | Count | Keywords | Centrality | Count |

| Abundance | 0.40 | 4 | Haze | 0.16 | 2 |

| Water [Aquatic Environment] |

0.33 | 4 | Model | 0.15 | 7 |

| Management | 0.33 | 4 | Construction waste | 0.15 | 2 |

| Air pollution [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.33 | 3 | Atmospheric mercury | 0.15 | 1 |

| Allocation principles | 0.29 | 1 | Aerosols | 0.14 | 2 |

| Exposure | 0.26 | 4 | Air pollution accidents [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.13 | 1 |

| Sea [Aquatic Environment] |

0.26 | 4 | Bayesian networks | 0.13 | 1 |

| Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region | 0.19 | 3 | Assessments | 0.13 | 1 |

| Emissions | 0.19 | 2 | Framework | 0.13 | 2 |

| Heavy metals | 0.19 | 2 | Air quality [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.12 | 2 |

| Pearl river delta [Aquatic Environment] |

0.18 | 4 | PM2.5 concentrations [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.11 | 2 |

| China | 0.17 | 15 | Pollution | 0.11 | 2 |

| Contamination | 0.17 | 3 | Sustainable development | 0.10 | 2 |

| Energy | 0.16 | 2 | Impact | 0.09 | 5 |

| Deep learning | 0.16 | 4 | Environment | 0.09 | 3 |

| Keywords | Centrality | Count | Keywords | Centrality | Count |

| 唐山市(Tangshan) | 0.06 | 5 | 污染源(Pollution sources) | 0.01 | 2 |

| 空气质量(Air quality) [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.04 | 9 | 惠州市( Huizhou) | 0.01 | 2 |

| 水环境(Water environment) [Aquatic Environment] |

0.01 | 7 | 低碳(Low-carbon) | 0.01 | 1 |

| 水质(Water quality) [Aquatic Environment] |

0.01 | 5 | 臭氧(Ozone) [Atmospheric Environment] |

0.01 | 1 |

| 水质评价(Water quality assessment) [Aquatic Environment] |

0.01 | 3 | 污染物(Pollutants) | 0.01 | 1 |

| 治理(Governance) | 0.01 | 2 |

|

|

|

|

|||

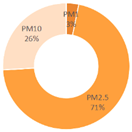

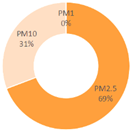

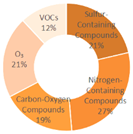

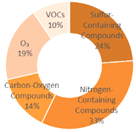

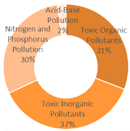

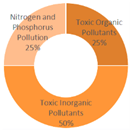

| All Cities | Shanghai | Dalian | Ningbo | |||

|

|

|

|

|||

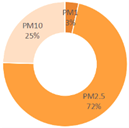

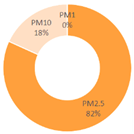

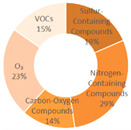

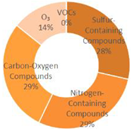

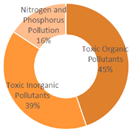

| Tangshan | Lianyungang | Zhangzhou | Huizhou | |||

|

|

|

|

|||

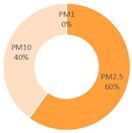

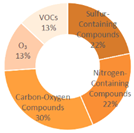

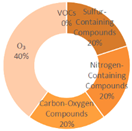

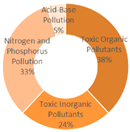

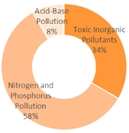

| All Cities | Shanghai | Dalian | Ningbo | |||

|

|

|

|

|||

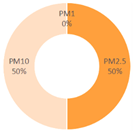

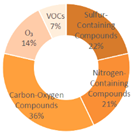

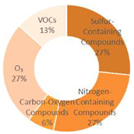

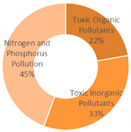

| Tangshan | Lianyungang | Zhangzhou | Huizhou | |||

|

|

|

|

|||

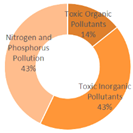

| All Cities | Shanghai | Dalian | Ningbo | |||

|

|

|

|

|||

| Tangshan | Lianyungang | Zhangzhou | Huizhou | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).