1. Introduction

Patients with type 2 diabetes are at substantially higher risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) compared to the general population [

1]. This is driven not only by diabetic nephropathy and vascular complications but also by the frequent presence of other comorbidities that predispose the kidney to injury. Obesity, which often overlaps with diabetes, introduces additional factors such as hypertension and fatty liver disease, further amplifying susceptibility. Episodes of AKI in this population carry weighty consequences, including progression to end stage kidney disease and greater cardiovascular risk [

1]. For this reason, understanding how modern diabetes and weight-management therapies affect AKI risk is an important clinical question.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) have become central to diabetes and obesity treatment because of their strong effects on glucose lowering, weight loss, and cardiovascular protection. Clinical trial data suggest that GLP-1 RAs improve chronic kidney disease (CKD) outcomes, for example by reducing macroalbuminuria and slowing eGFR decline [

2]. Yet post-marketing data have raised a different concern: reports of acute renal events. Case series and pharmacovigilance studies link GLP-1 RAs to AKI, often attributed to dehydration from severe gastrointestinal side effects [

3]. In some cases, however, intrinsic kidney injury such as biopsy-proven interstitial nephritis has been reported [

4,

5].

Semaglutide is a widely used GLP-1 RA with proven benefits but also scattered reports of AKI. Case reports describe both prerenal azotemia and interstitial nephritis [

6,

7]. Pharmacovigilance studies confirm that semaglutide, along with liraglutide, has been associated with a modest signal for AKI in the FAERS database [

3]. While clinical trial data show very low absolute event rates (generally <0.5%) [

8,

9], this discrepancy between trial and real-world data warrants attention.

Tirzepatide, a dual GIP and GLP-1 agonist, was approved in 2022 and has shown impressive metabolic benefits. Post-hoc analyses of clinical trials suggest it may slow CKD progression [

10], but real-world safety data are still limited. A few case reports describe AKI with tirzepatide use [

11], and the drug’s label notes this as a potential risk. However, initial pharmacovigilance analyses have not identified a clear signal [

11].

Because neither the SUSTAIN trials for semaglutide nor the SURPASS trials for tirzepatide were designed to capture rare renal events, head-to-head comparisons are lacking. To address this gap, we conducted a comparative FAERS disproportionality analysis of AKI reports for both drugs from January 2022 through September 2025. Although spontaneous reporting databases have limitations, they can shed light on whether one agent is disproportionately associated with AKI.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective pharmacovigilance study using the publicly accessible U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), covering the period from January 2022 through September 2025. All domestic reports were reviewed, and cases were included if tirzepatide or semaglutide was listed as the primary suspect drug. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was broadly defined using relevant MedDRA preferred terms, including acute kidney injury, renal failure, renal impairment, renal injury, tubulointerstitial nephritis, renal tubular necrosis, and anuria. Duplicate entries were avoided by relying on FAERS unique case identifiers. For each drug, we tabulated total adverse event (AE) reports, AKI counts, sex distribution, year of report, and serious outcomes (death, disability, hospitalization, life-threatening).

To assess whether AKI was disproportionately reported, we used two established disproportionality metrics. The reporting odds ratio (ROR) was calculated from 2×2 contingency tables as (a×d)/(b×c), where a represents AKI cases with the drug of interest, b non-AKI cases with the drug of interest, c AKI cases with the comparator drug, and d non-AKI cases with the comparator. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) for the ROR were estimated using the standard error of the natural log of ROR. We also calculated the proportional reporting ratio (PRR), defined as [a/(a+b)] / [c/(c+d)]. Both metrics can be derived directly from the counts presented in

Table 1 using standard spreadsheet calculations. A disproportionality signal was considered present when the lower bound of the 95% CI for the ROR excluded 1, or when the PRR was ≥2 with at least three cases [

12,

13].

3. Results

We identified 92,807 domestic AE reports for tirzepatide, including 432 (0.47%) AKI cases, and 41,065 reports for semaglutide, including 440 (1.07%) AKI cases. Relative disproportionality favored tirzepatide: the ROR comparing tirzepatide vs semaglutide was 0.44 (95% CI 0.38–0.50), with a PRR of 0.44. Accordingly, AKI appeared less frequently among tirzepatide reports than among semaglutide reports (

Table 1).

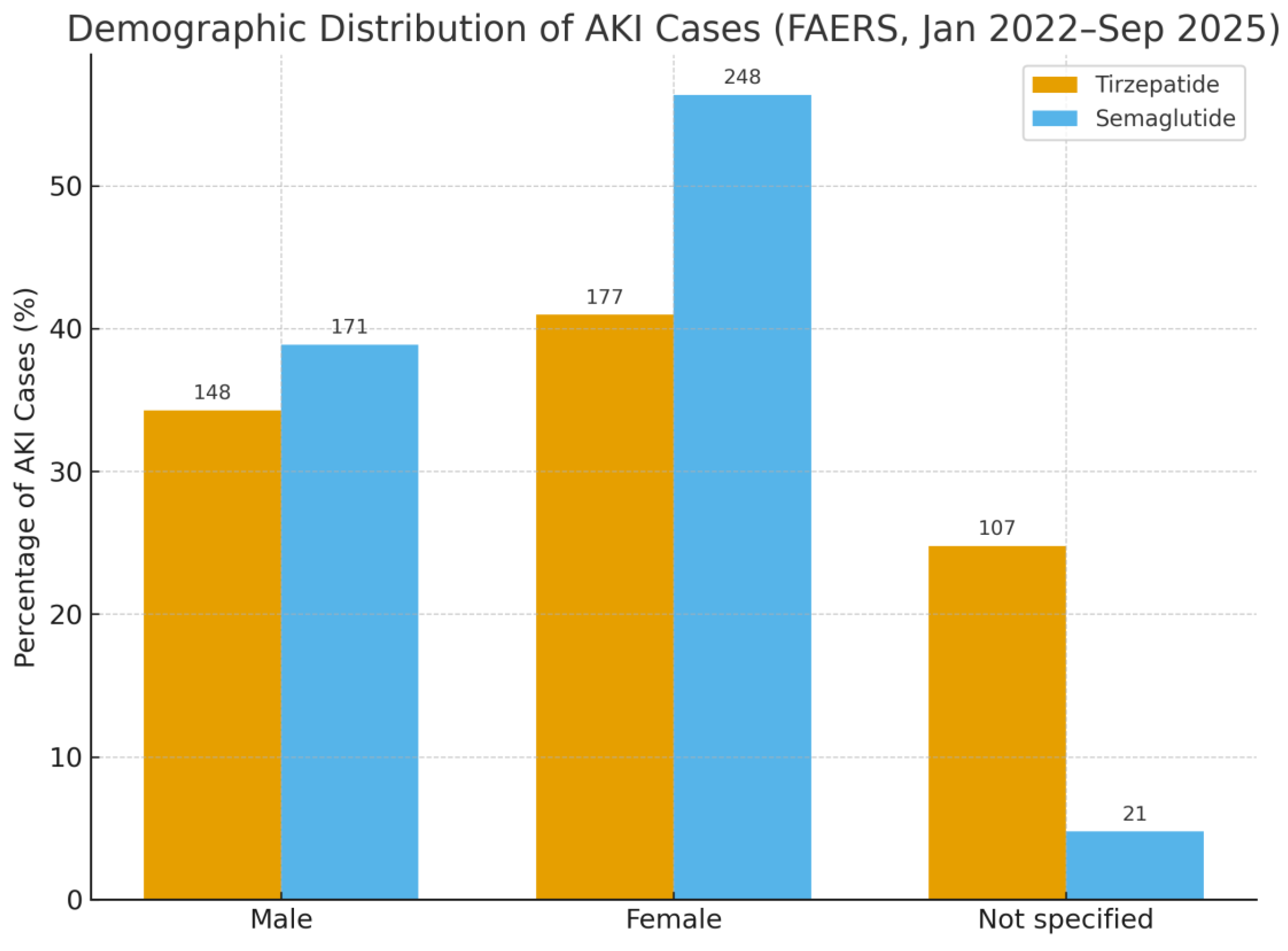

Sex distribution among AKI cases differed between drugs. With tirzepatide (n = 432), 34.3% were male, 41.0% female, and 24.8% not specified; with semaglutide (n = 440), 38.9% were male, 56.4% female, and 4.8% not specified (

Figure 1).

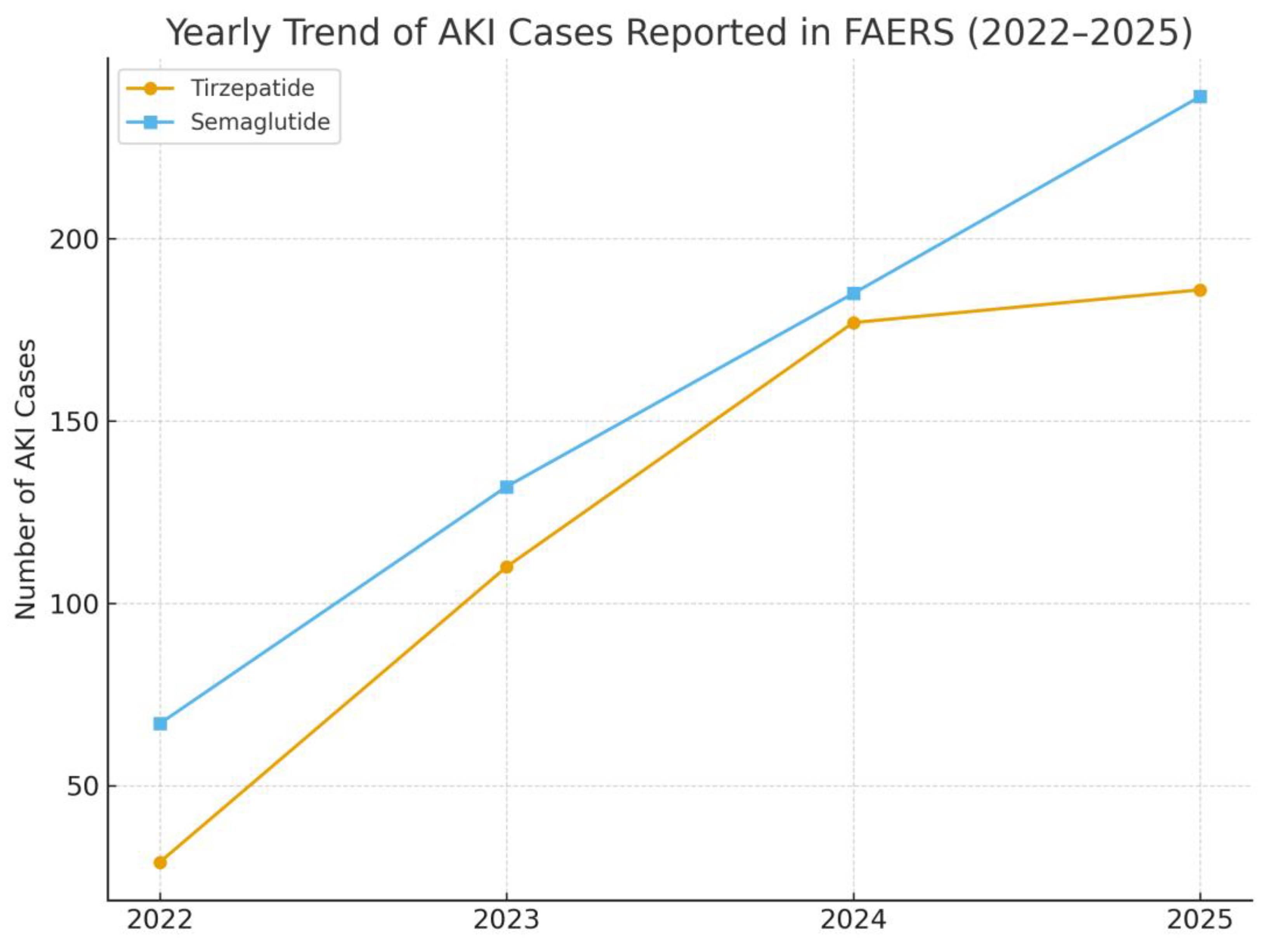

AKI reports rose steadily for both drugs, reaching 186 cases for tirzepatide and 239 cases for semaglutide in 2025 (

Figure 2).

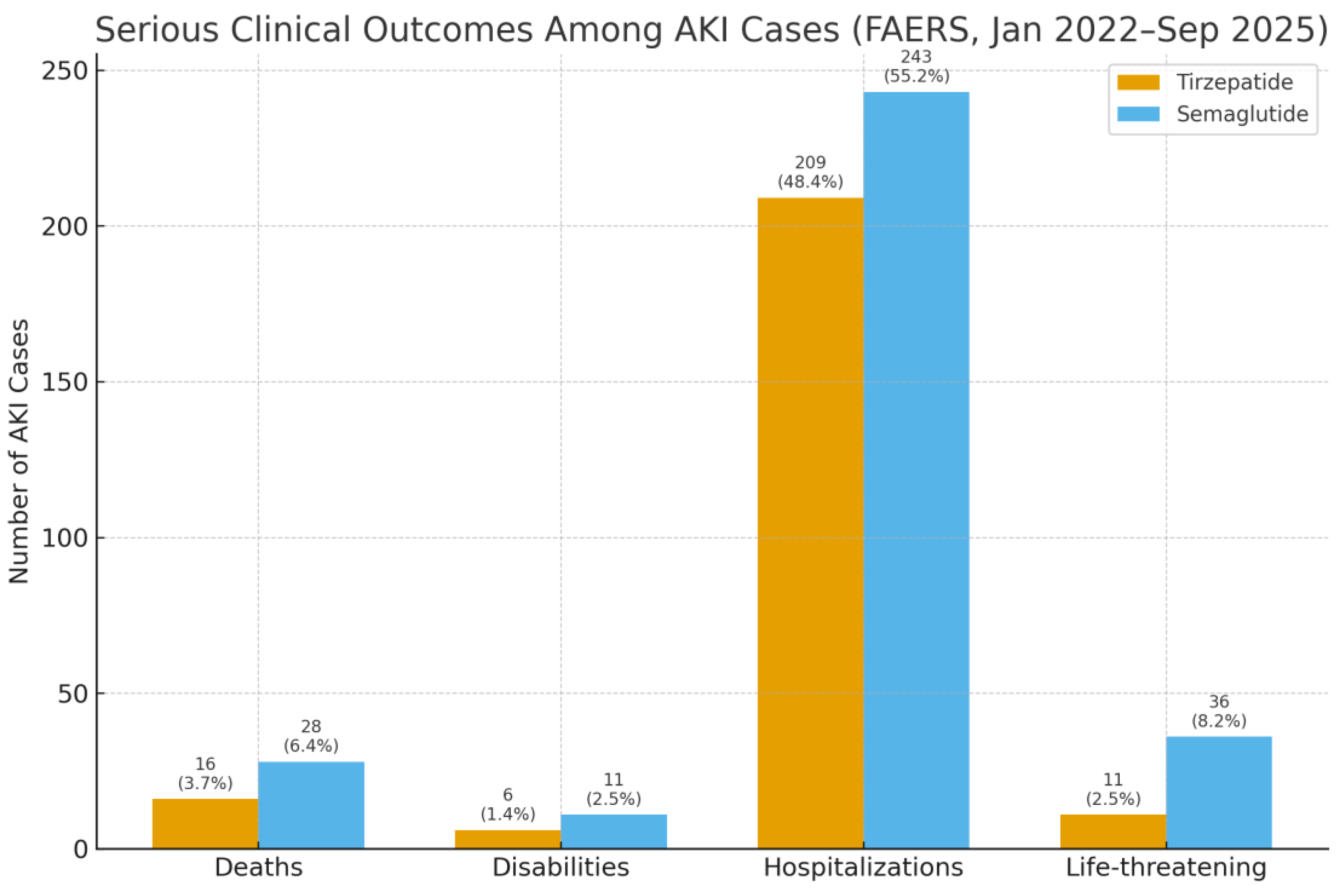

Serious outcomes among AKI reports were numerically higher for semaglutide: tirzepatide had 16 deaths, 6 disabilities, 209 hospitalizations, and 11 life-threatening events; semaglutide had 28 deaths, 11 disabilities, 243 hospitalizations, and 36 life-threatening events (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

This analysis demonstrates a marked divergence in pharmacovigilance signals between tirzepatide and semaglutide. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was reported at more than twice the proportional rate with semaglutide compared to tirzepatide, with a reporting odds ratio of 0.44 (95% CI, 0.38–0.50) favoring tirzepatide. The proportional reporting ratio confirmed this observation. Semaglutide, unlike tirzepatide, crossed conventional thresholds for a disproportionality signal.

Although the rise in AKI reports for both agents likely reflects broader clinical uptake, semaglutide consistently accounted for a larger share of serious outcomes, including hospitalizations and deaths. This pattern echoes earlier case reports and pharmacovigilance studies implicating GLP-1 receptor agonists in AKI, usually linked to gastrointestinal fluid loss, though biopsy-proven interstitial nephritis has occasionally been reported [

3,

6].

The lack of a disproportionality signal for tirzepatide should not be taken to mean no risk; rather, it suggests that reporting frequencies have not yet exceeded background expectations. In contrast, semaglutide’s enrichment for AKI aligns with prior pharmacovigilance data and supports its recognition as a GLP-1 RA with a reproducible, albeit infrequent, renal safety concern [

3,

11]. These findings suggest a potential safety distinction between tirzepatide and semaglutide in real-world reporting.

Clinical trial evidence provides an important counterpoint. In both the SURPASS program for tirzepatide and the SUSTAIN/PIONEER trials for semaglutide, AKI events were rare. A pooled analysis of semaglutide trials identified only 18 AKI cases among more than 9,000 treated participants, mirroring comparator rates [

15]. Similarly, cardiovascular outcome studies have suggested renal benefit, such as reduced macroalbuminuria with semaglutide [

2] and slower eGFR decline with tirzepatide [

10]. Small numerical imbalances in AKI events have been observed in semaglutide trials (8 vs. 1 with comparators), though these were not statistically significant [

6,

16]. Such findings may reconcile with the FAERS signal, suggesting that rare events emerge in practice despite being underpowered for detection in trials.

Mechanistically, the most plausible cause of AKI with GLP-1 RAs is prerenal azotemia from dehydration due to gastrointestinal side effects, particularly nausea and vomiting during dose escalation [

3,

17]. Rarely, idiosyncratic interstitial nephritis has been confirmed on biopsy [

6]. GIP receptor activity is unlikely to substantially alter these pathways, as renal expression is minimal [

2].

In clinical practice, these findings underscore the importance of patient counseling and monitoring. For semaglutide, the reproducible AKI signal highlights the need to ensure adequate hydration, monitor renal function, and hold therapy temporarily during episodes of intercurrent illness. Tirzepatide, despite not showing a signal to date, should be managed with similar precautions given the presence of isolated case reports [

11]. Although uncommon, AKI can be clinically significant: a notable proportion of cases required hospitalization, and some resulted in death [

3]. Encouragingly, renal function often recovered after drug withdrawal and rehydration, and rechallenge may be possible unless interstitial nephritis is suspected [

18].

Although FAERS is constrained by reporting biases and other limitations, the reproducibility of semaglutide’s signal across independent datasets and case series strengthens its clinical plausibility. Continued surveillance and robust real-world studies are essential to clarify whether tirzepatide’s apparent renal safety advantage persists with broader exposure.

5. Conclusions

In summary, semaglutide continues to show a disproportionate signal for AKI in FAERS, while tirzepatide does not. Although absolute risk is low, the signal supports careful hydration counseling and monitoring for patients starting semaglutide. Tirzepatide appears reassuring so far, but ongoing pharmacovigilance is needed as its use expands. Large, well-controlled cohort studies using electronic health records and mechanistic studies of renal physiology will be critical to confirm whether these drugs truly differ in AKI risk or if reporting differences explain the discrepancy. For now, both agents remain valuable therapies with strong metabolic and renal benefits, provided that clinicians remain alert to potential acute kidney complications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, All adverse event data used in this study were obtained from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). FAERS is a publicly accessible database, available at the FDA’s official website.

Author Contributions

A.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the analysis was conducted using publicly available, de-identified data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). This study did not involve human participants, patient-level data, or animal research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are publicly available from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) at the FDA’s official website

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Lee, J.; Liu, J.-J.; Liu, S.; Liu, A.; Zheng, H.; Chan, C.; Shao, Y.M.; Gurung, R.L.; Ang, K.; Lim, S.C. Acute kidney injury predicts the risk of adverse cardio renal events and all cause death in southeast Asian people with type 2 diabetes. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 27027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, I.; Giorgino, F. Renal effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists and tirzepatide in individuals with type 2 diabetes: seeds of a promising future. Endocrine 2024, 84, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Sun, C. Can glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists cause acute kidney injury? An analytical study based on post-marketing approval pharmacovigilance data. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 1032199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, F.; Chang, K.; Kapoor, K.; Vij, R.; Phadke, G.; Hiser, W.M.; Wanchoo, R.; Sharma, P.; Sutaria, N.; Jhaveri, K.D. Semaglutide-associated kidney injury. Clin Kidney J 2024, 17, sfae250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komala, M.G.; Renthawa, J. A Case of Dulaglutide-Induced Acute Interstitial Nephritis After Many Years of Treatment With an Alternate GLP-1 Receptor Agonist. Clin Diabetes 2022, 40, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leehey, D.J.; Rahman, M.A.; Borys, E.; Picken, M.M.; Clise, C.E. Acute Kidney Injury Associated With Semaglutide. Kidney Med 2021, 3, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkum, M.; Lau, W.; Blanco, P.; Farah, M. Semaglutide-Associated Acute Interstitial Nephritis: A Case Report. Kidney Medicine 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorli, C.; Harashima, S.I.; Tsoukas, G.M.; Unger, J.; Karsbøl, J.D.; Hansen, T.; Bain, S.C. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide monotherapy versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multinational, multicentre phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017, 5, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroda, V.R.; Erhan, U.; Jelnes, P.; Meier, J.J.; Abildlund, M.T.; Pratley, R.; Vilsbøll, T.; Husain, M. Safety and tolerability of semaglutide across the SUSTAIN and PIONEER phase IIIa clinical trial programmes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2023, 25, 1385–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Sattar, N.; Pavo, I.; Haupt, A.; Duffin, K.L.; Yang, Z.; Wiese, R.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Cherney, D.Z.I. Effects of tirzepatide versus insulin glargine on kidney outcomes in type 2 diabetes in the SURPASS-4 trial: post-hoc analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2022, 10, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xie, J.; Han, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z. A real-world disproportionality analysis of tirzepatide-related adverse events based on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database. Endocr J 2025, 72, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaeda, T.; Tamon, A.; Kadoyama, K.; Okuno, Y. Data mining of the public version of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Int J Med Sci 2013, 10, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.J.; Waller, P.C.; Davis, S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2001, 10, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartnell, N.R.; Wilson, J.P. Replication of the Weber effect using postmarketing adverse event reports voluntarily submitted to the United States Food and Drug Administration. Pharmacotherapy 2004, 24, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feier, C.V.I.; Vonica, R.C.; Faur, A.M.; Streinu, D.R.; Muntean, C. Assessment of Thyroid Carcinogenic Risk and Safety Profile of GLP1-RA Semaglutide (Ozempic) Therapy for Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J.F.E.; Hansen, T.; Idorn, T.; Leiter, L.A.; Marso, S.P.; Rossing, P.; Seufert, J.; Tadayon, S.; Vilsbøll, T. Effects of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide on kidney function and safety in patients with type 2 diabetes: a post-hoc analysis of the SUSTAIN 1-7 randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020, 8, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oesterle, T.S.; Ho, M.-F. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists: A New Frontier in Treating Alcohol Use Disorder. Brain Sciences 2025, 15, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstock, J.; Fonseca, V.A.; Gross, J.L.; Ratner, R.E.; Ahrén, B.; Chow, F.C.; Yang, F.; Miller, D.; Johnson, S.L.; Stewart, M.W.; et al. Advancing basal insulin replacement in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with insulin glargine plus oral agents: a comparison of adding albiglutide, a weekly GLP-1 receptor agonist, versus thrice-daily prandial insulin lispro. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2317–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).