Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

01 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

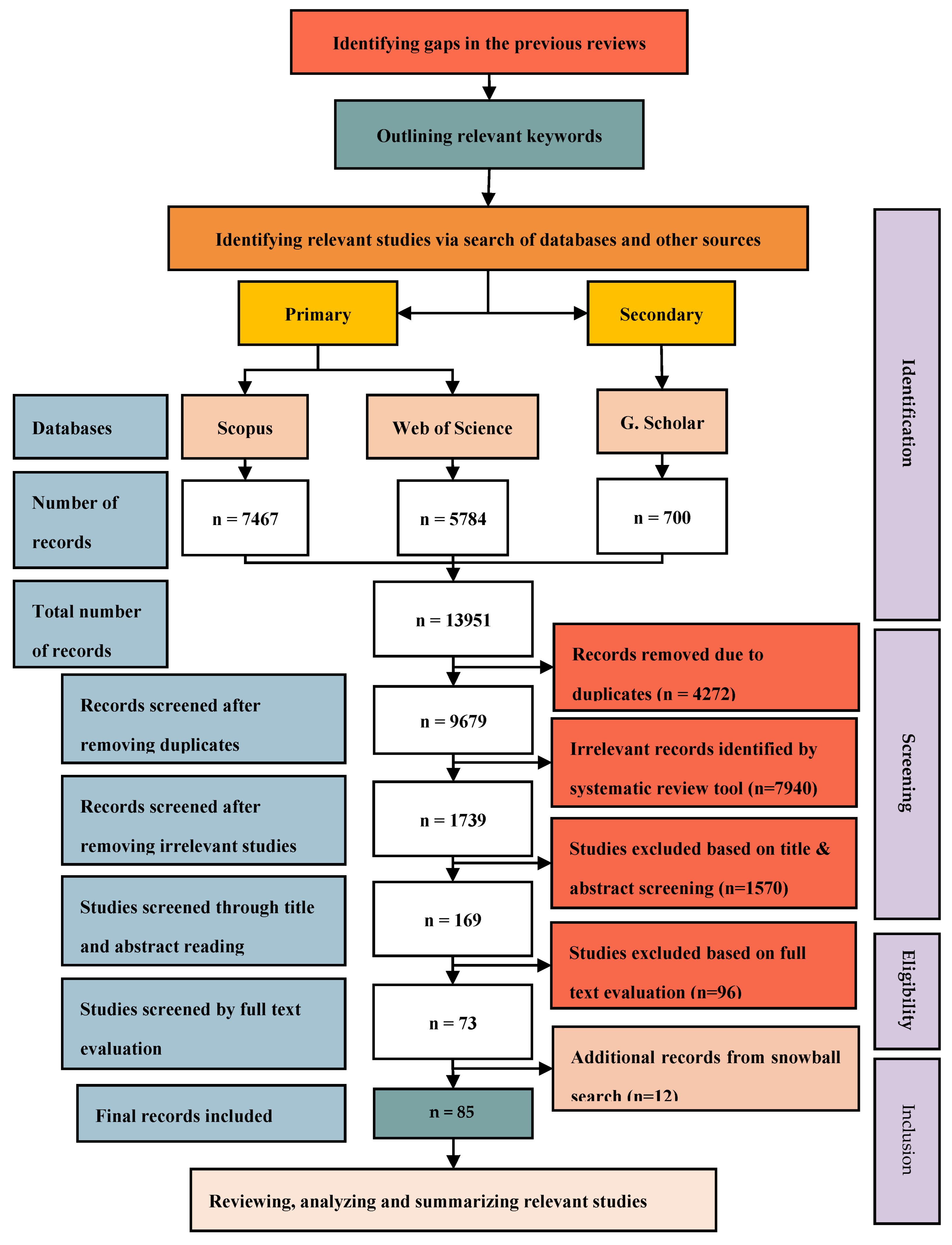

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Identification

2.2. Data Screening and Inclusion

2.3. Data Analysis

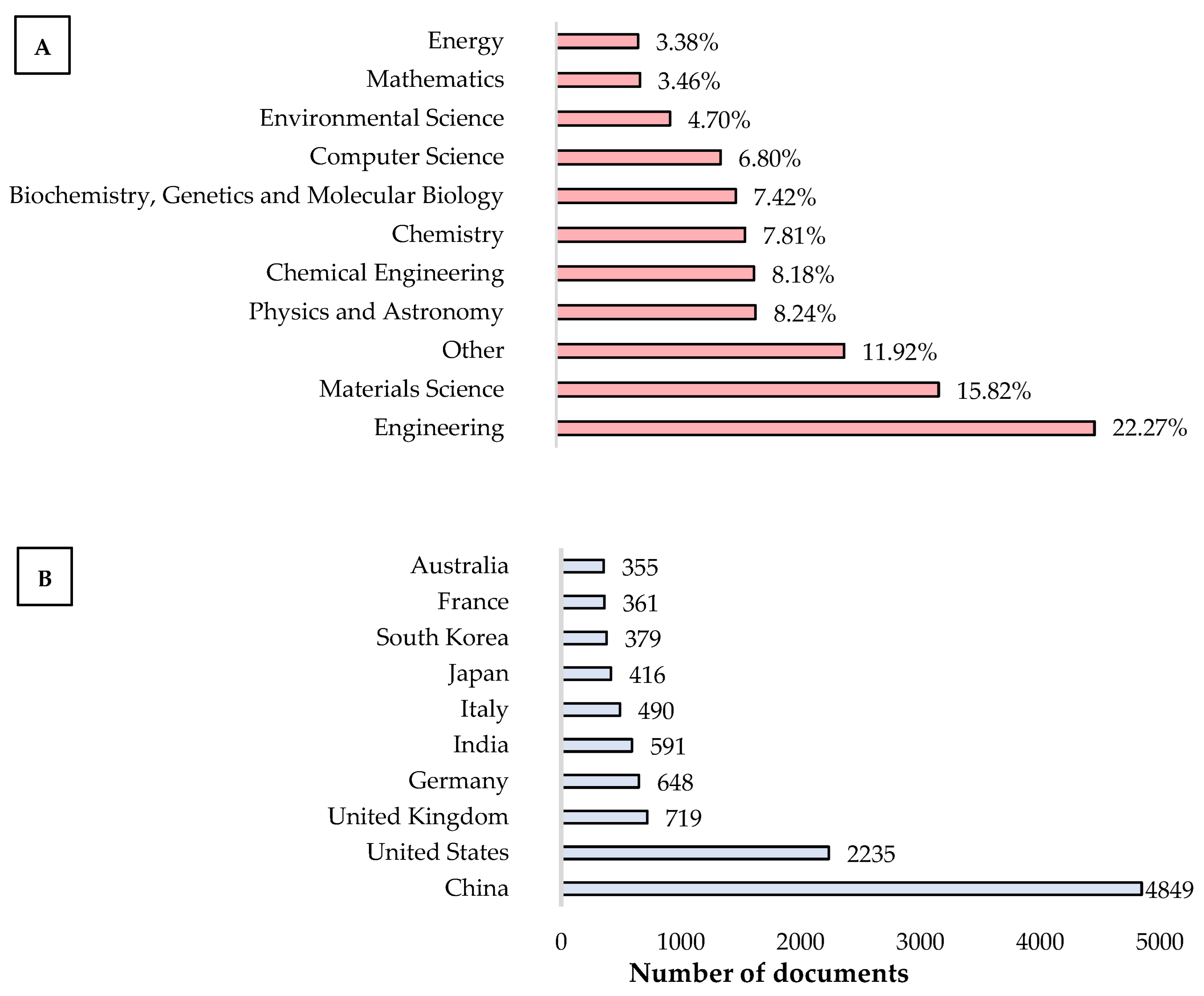

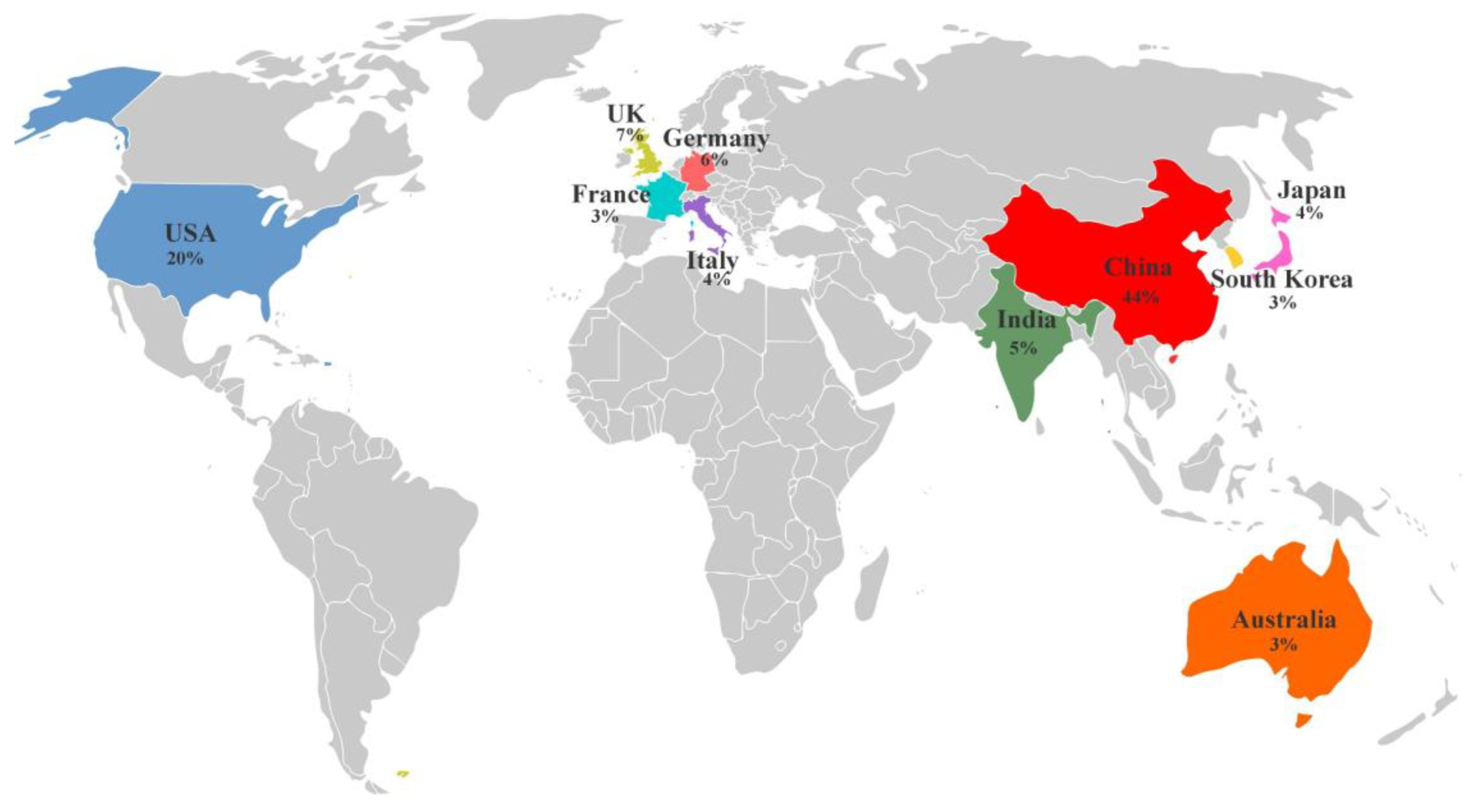

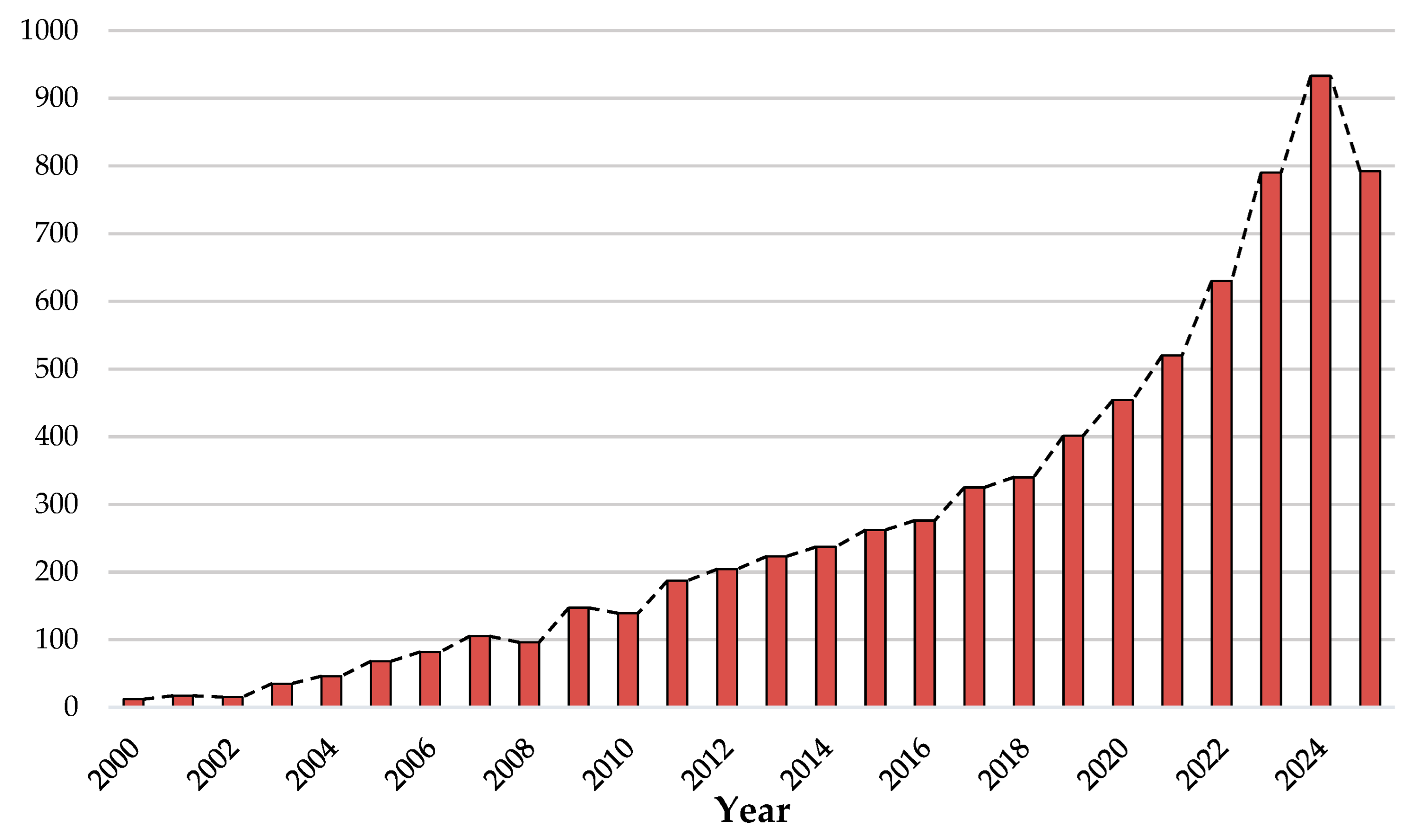

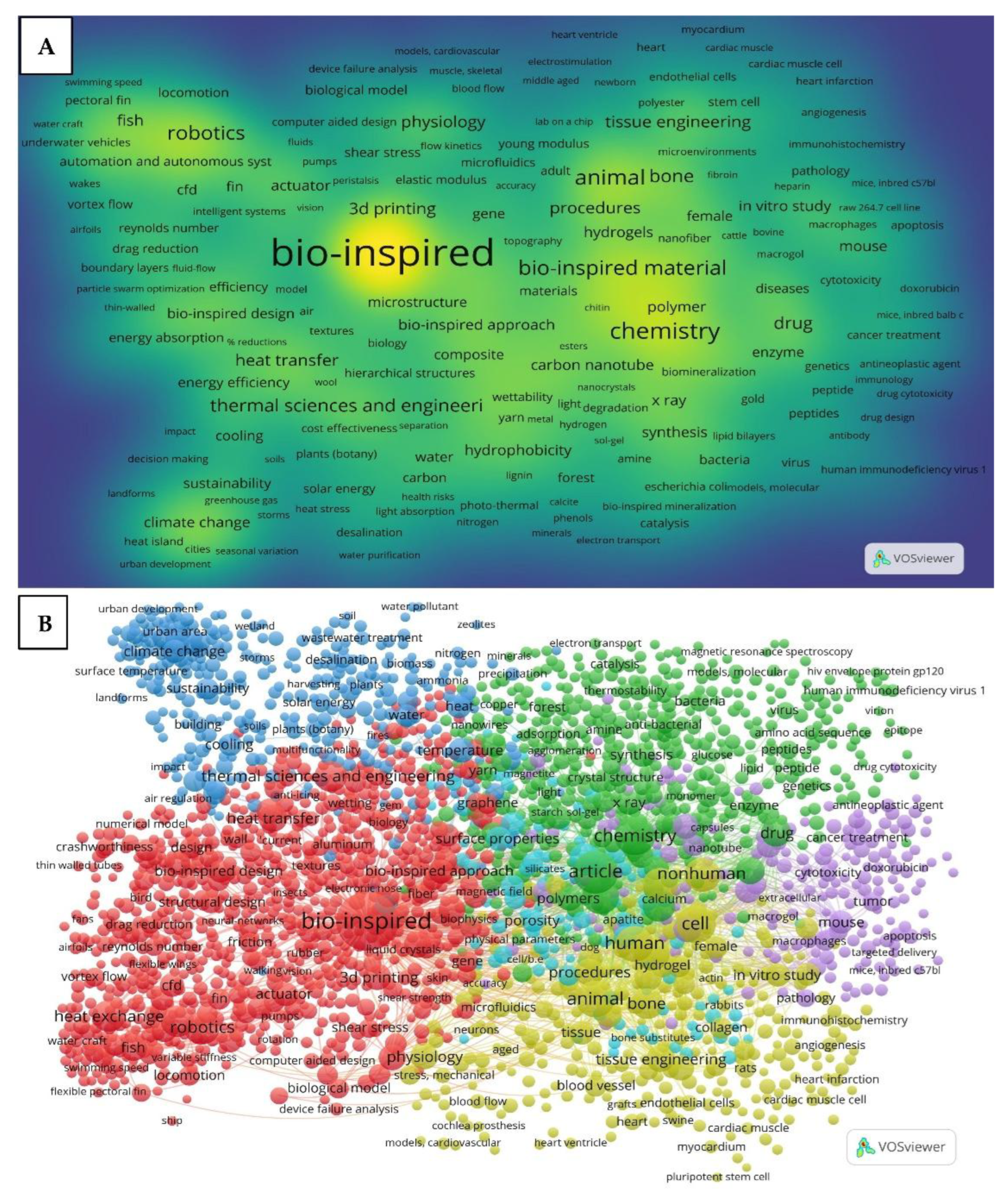

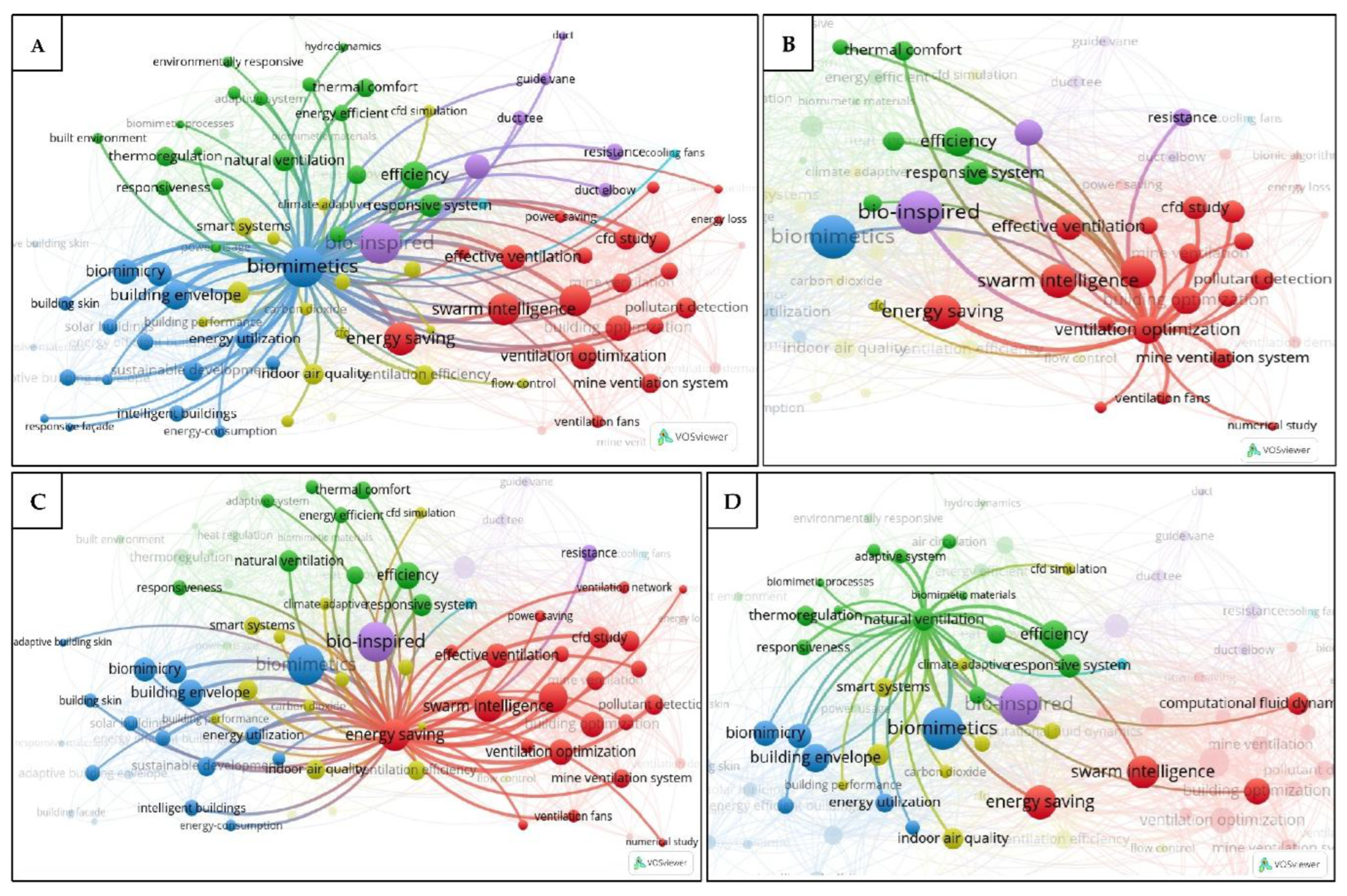

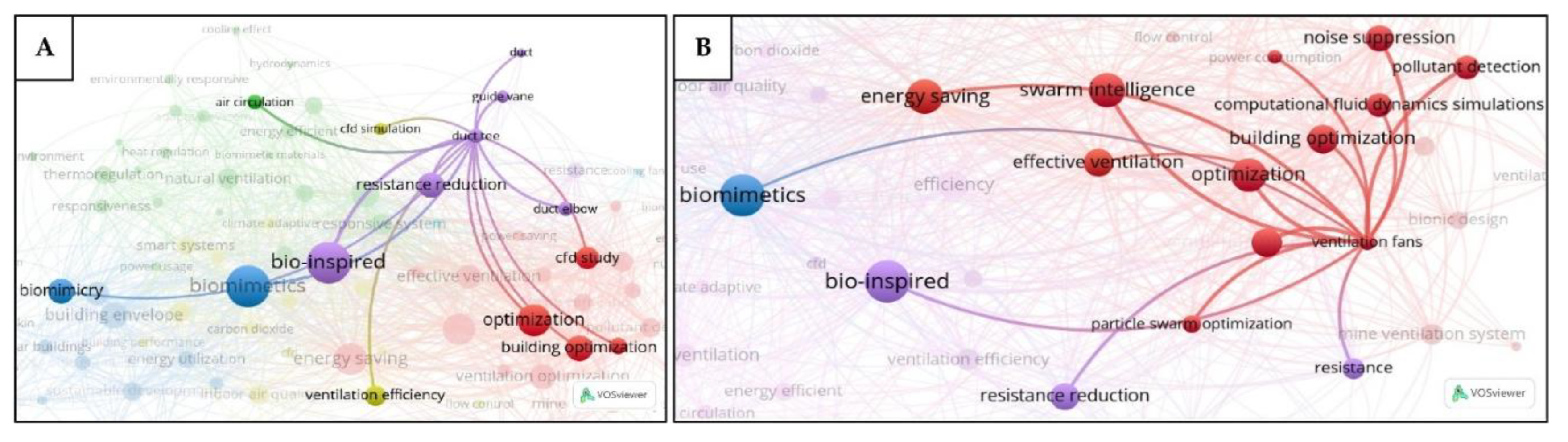

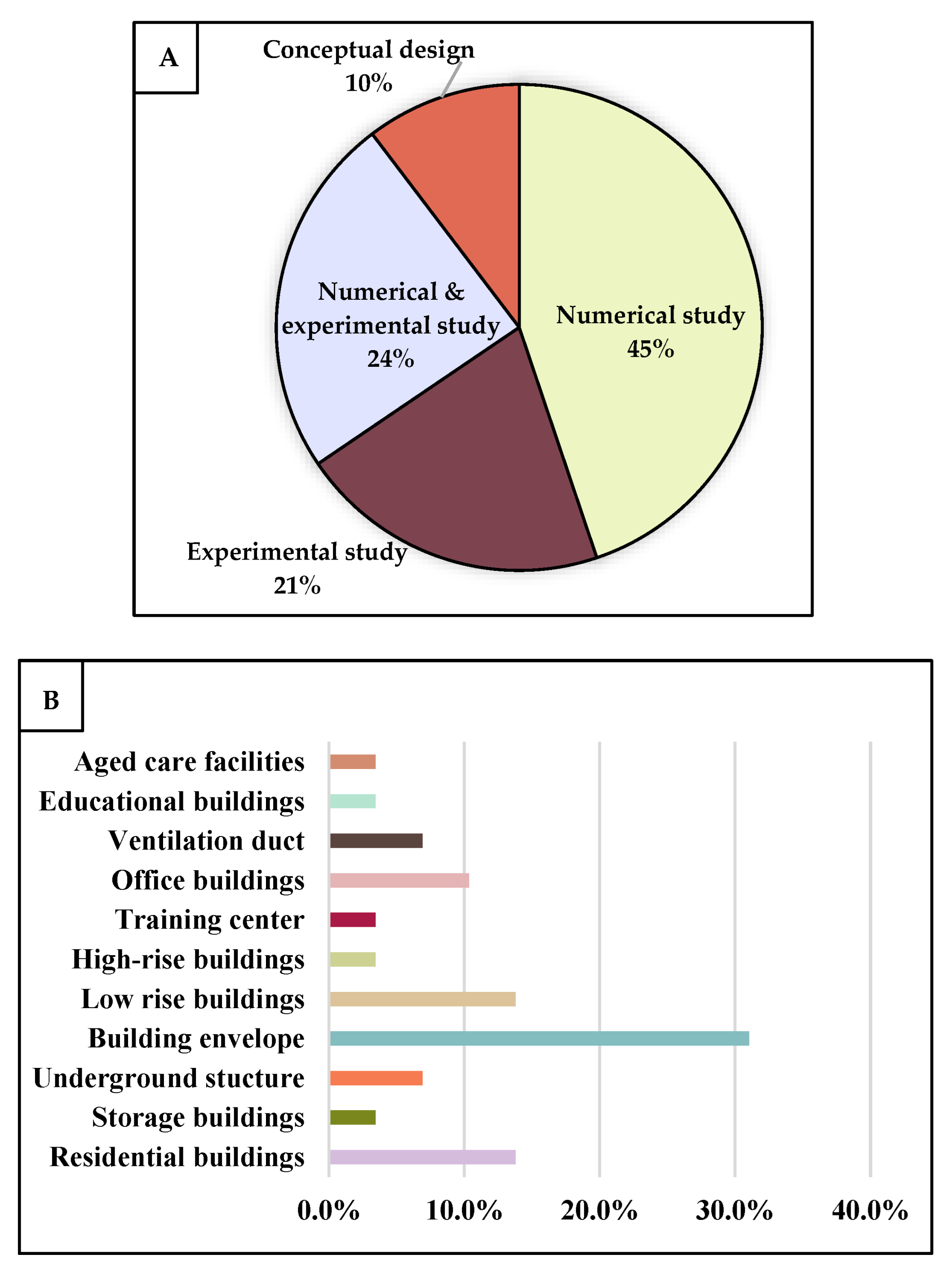

2.3.1. Research Trend and Bibliometric Analysis

2.3.2. Comparative Analysis

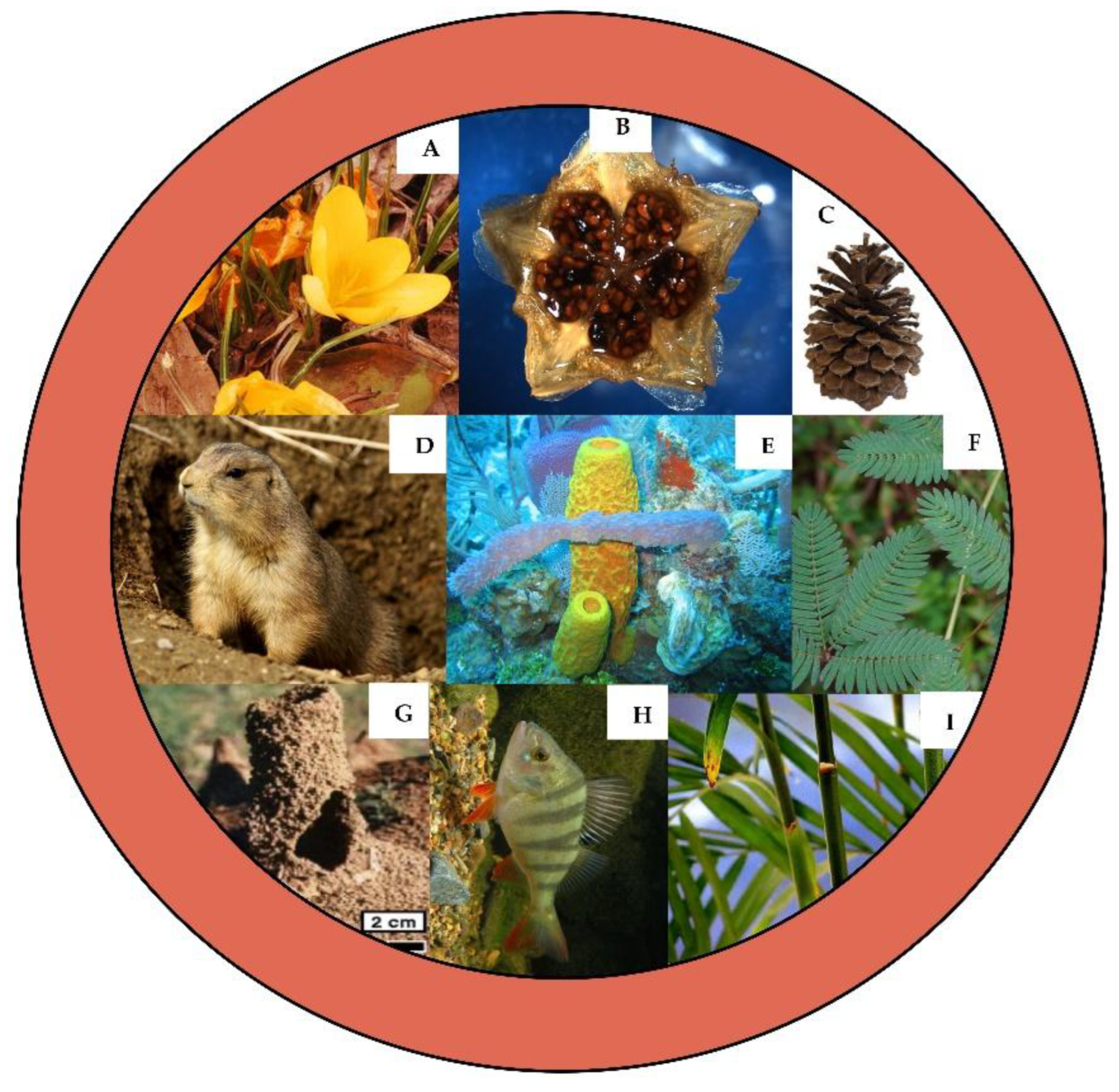

3. Designs and Strategies Inspired by Animal Dwellings for Improving Natural Ventilation

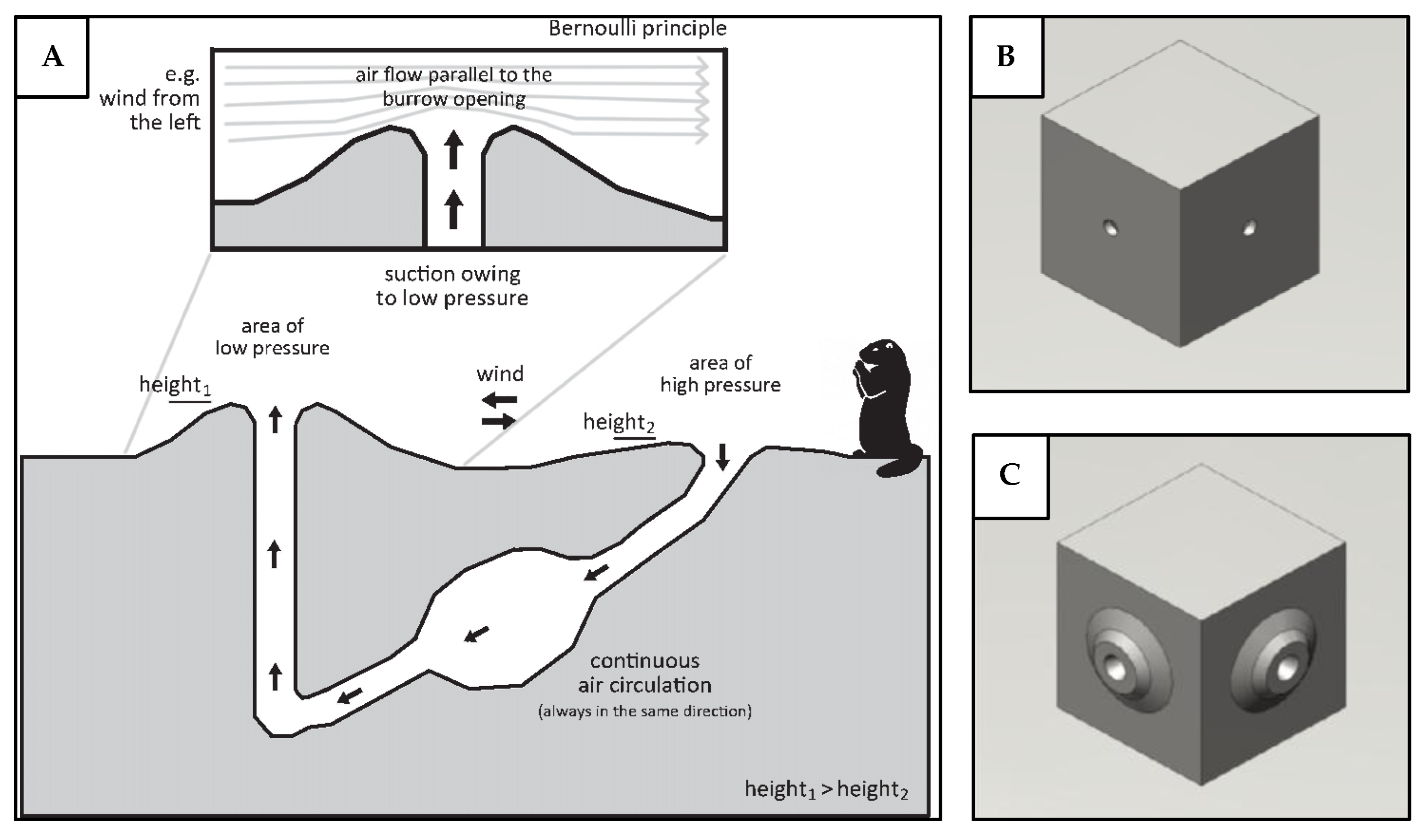

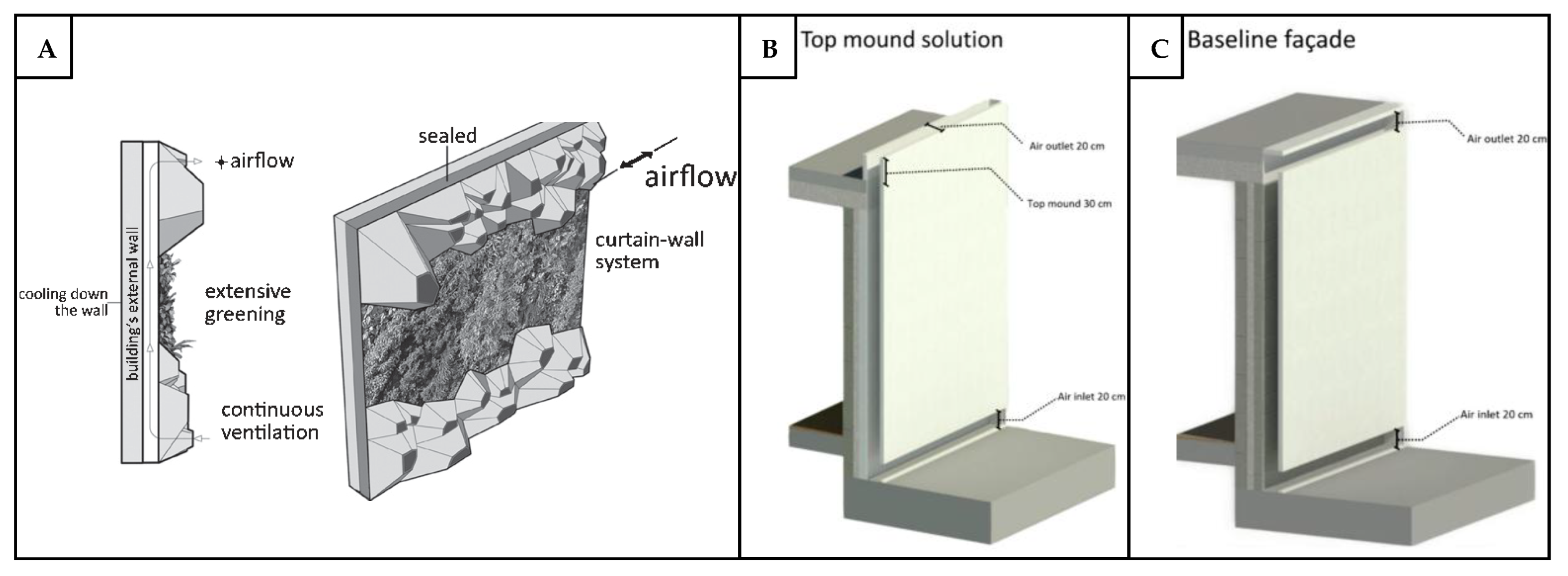

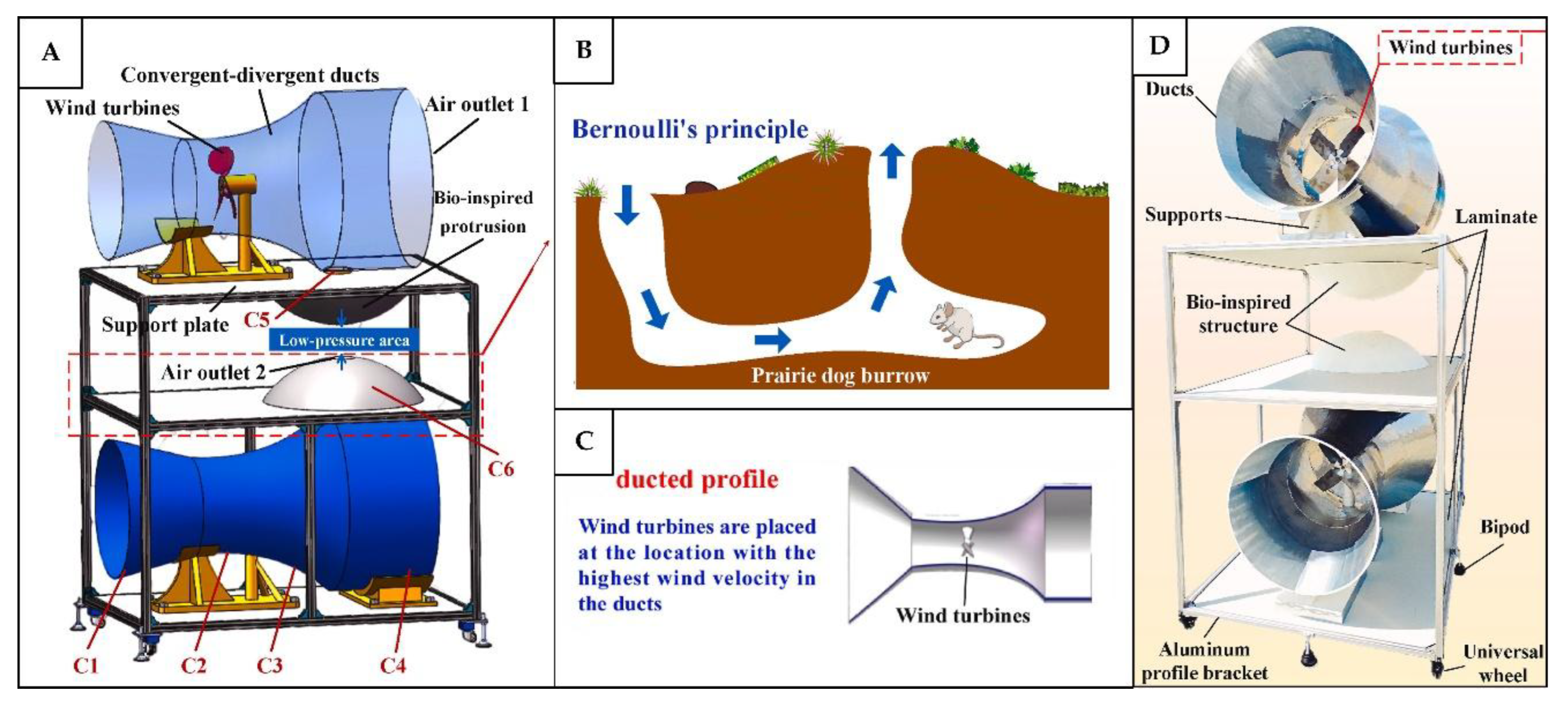

3.1. Insights from Prairie Dog Burrows

3.2. Insights from Termite Mounds

3.3. Insights from Ant Nests

4. Learning from Biological Systems for Effective Ventilation

4.1. Inspiration from Mammalian and Avian Respiratory Systems

4.2. Inspiration from Kidney and Fractal Structures

| Source of inspiration | Mimicked features | Applications | Advantages | Challenges/limitations | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human and animal respiratory systems | Periodic inhalation–exhalation. | Time-periodic ventilation system with single or dual inlets. | More uniform velocity distribution; reduced pollutants in stagnant zones; higher ventilation efficiency; lower age of air. | Computationally demanding to simulate; impact on occupants’ thermal comfort not investigated. | [86] |

| Human respiratory system | Periodic movement of volumes between the lung interior and exterior. | Biomimetic active ventilation (BAV) modules that separate indoor and outdoor environments. | Faster air exchange rate between indoor and outdoor environments. | Model assumes advection-dominated transport; natural ventilation is only effective with wind inflow; the impact on occupants’ thermal comfort is not considered. | [85] |

| Kidney’s Loop of Henle | Substance extraction before waste removal. | Natural ventilation with a heat recovery system. | Lower heating load; improved airflow and reduced CO₂ when coupled with stack ventilation. | Does not meet thermal comfort needs in rooms with single occupancy; performance is influenced by the closing/opening of doors. | [90] |

| Fractal structures | Self-repeating branching patterns. | Fractal ventilation networks. | Improved airflow and cooling uniformity; enhanced cooling in weakly ventilated areas. | Reduced upward penetration; slower air diffusion and cooling rate. | [93] |

5. Bio-Inspired Structures and Strategies for Optimization of Ventilation System and Its Components

5.1. Nature-Inspired Algorithm for Ventilation in Underground Mines and Buildings

5.2. Fishbone Shape for Outdoor Ventilation

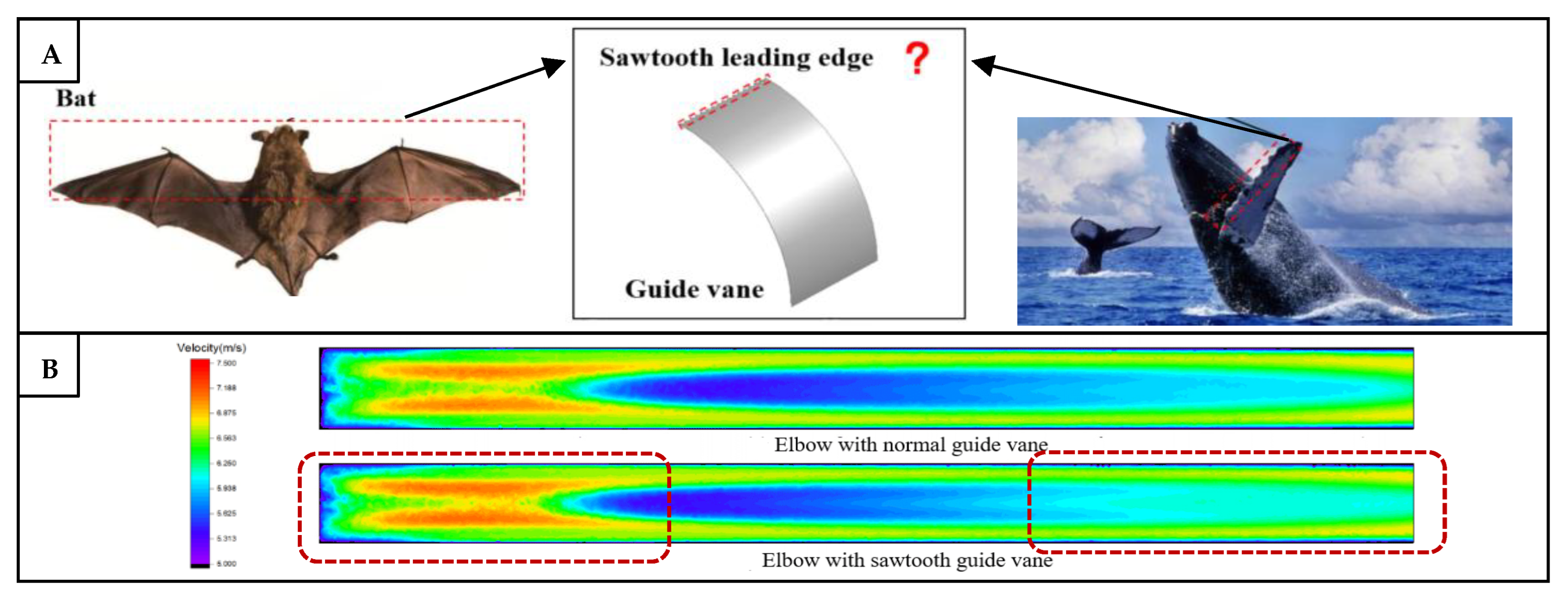

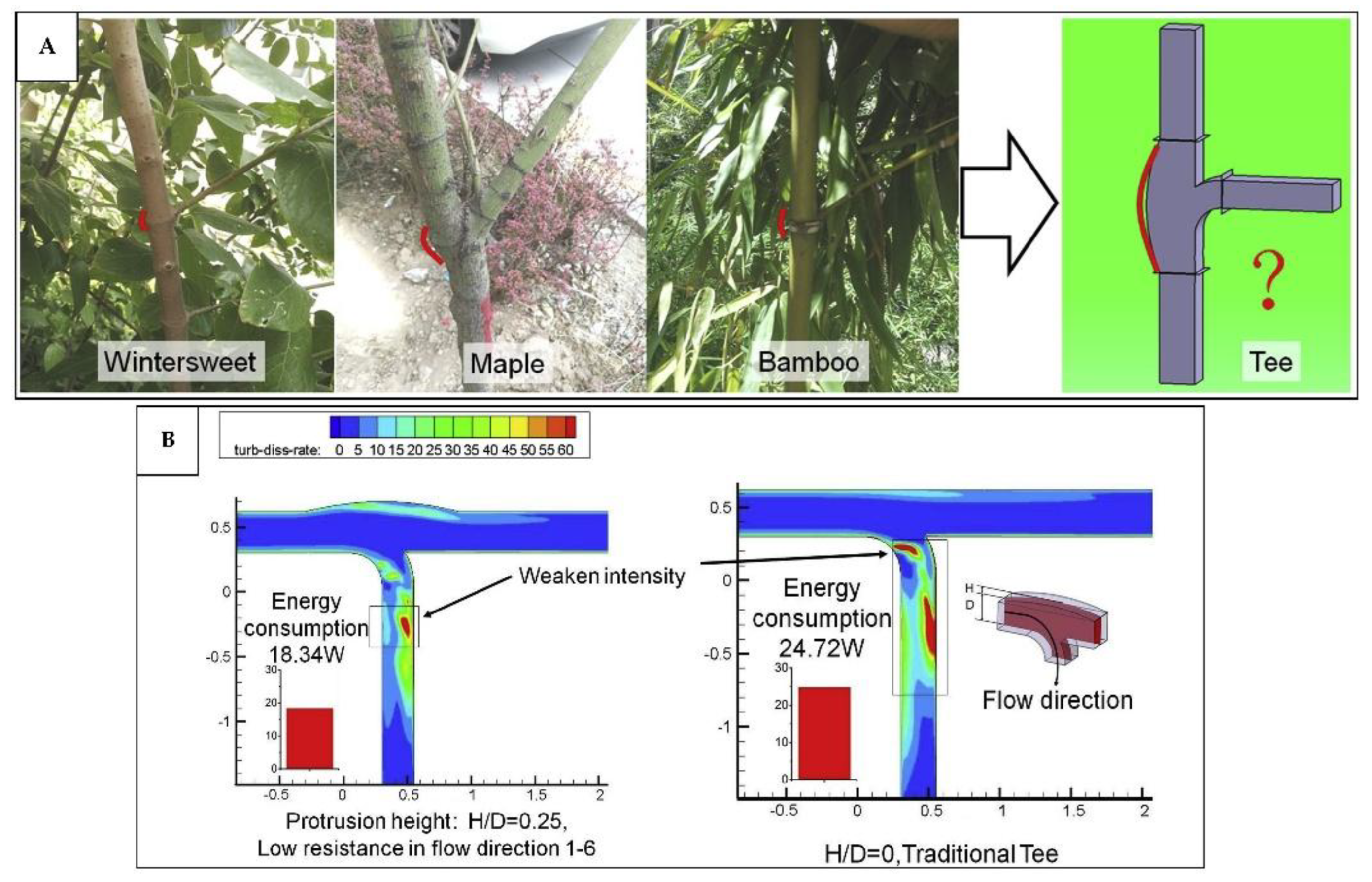

5.3. Designs Inspired by Bat Wings, Whale Fins, and Trees for Duct Resistance Reduction

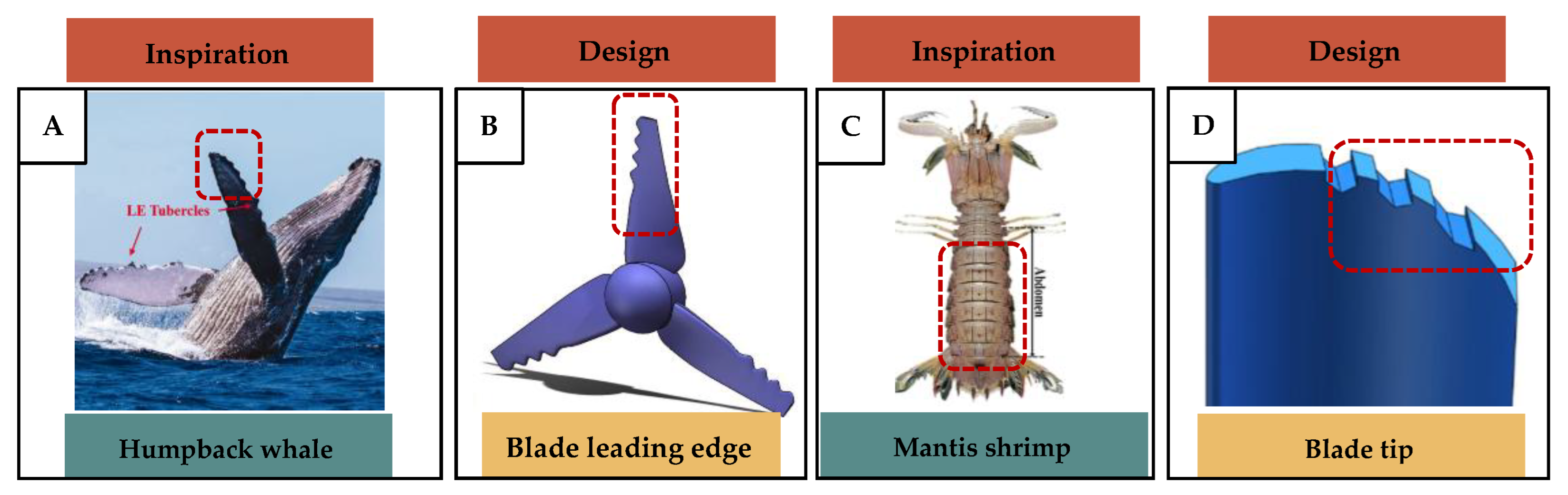

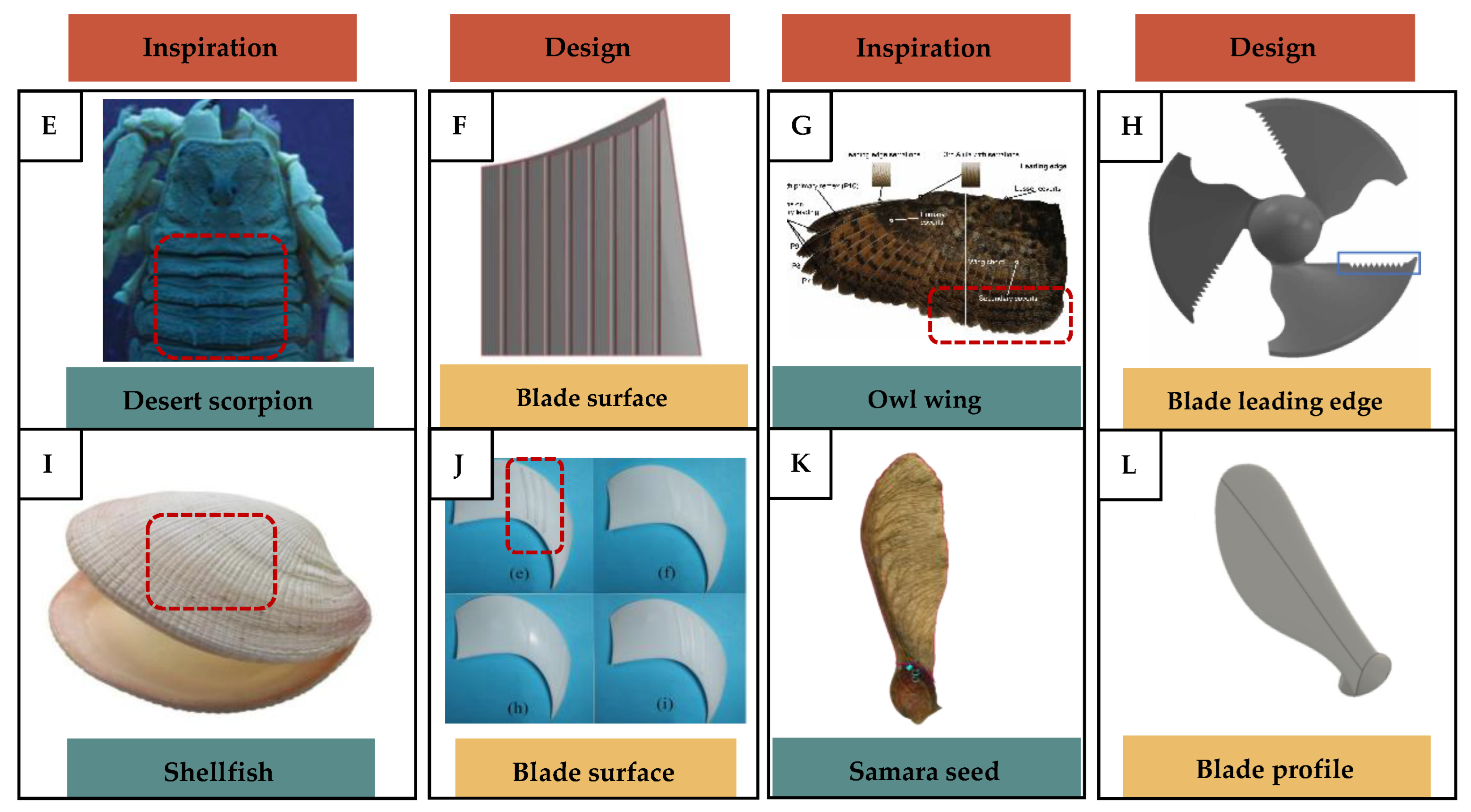

5.4. Insight from Animals for Ventilation Fan Optimization

6. Bio-Inspired Approaches for Adaptive Ventilation

6.1. Insights from Plants

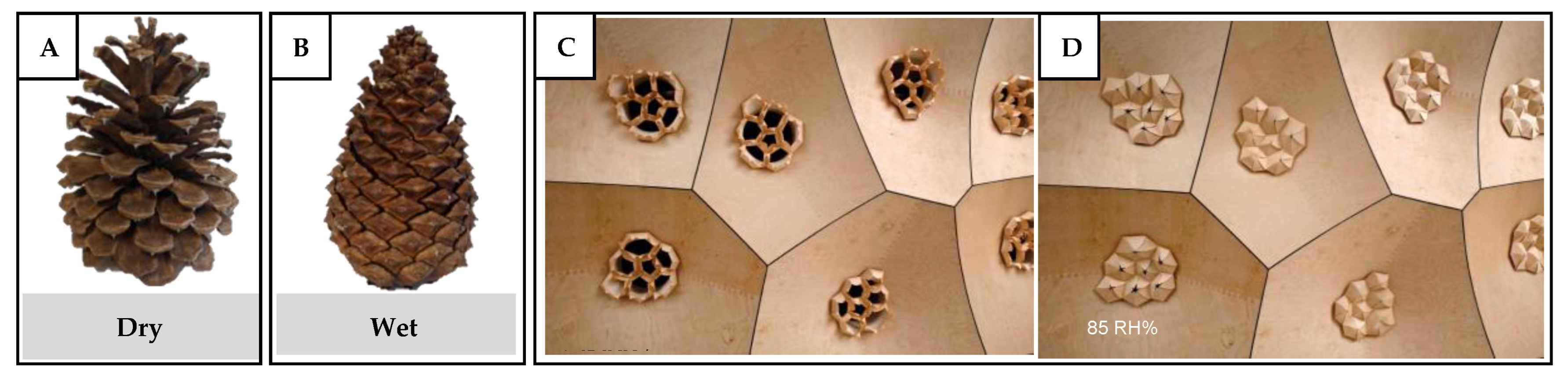

6.1.1. Pine Cones

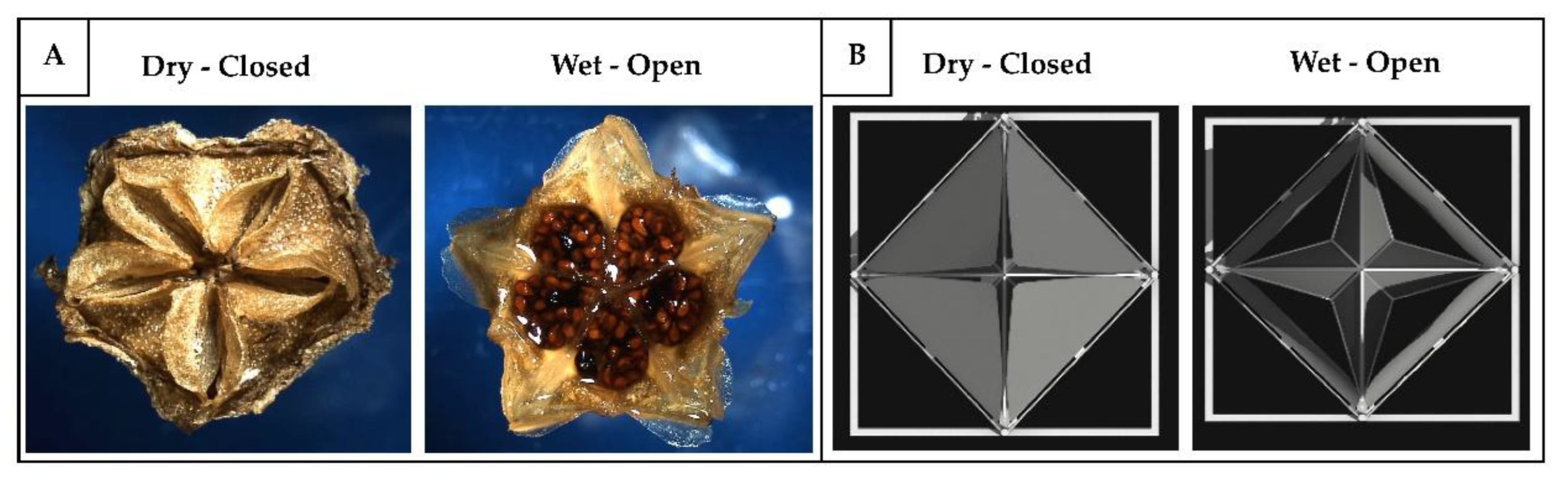

6.1.2. Ice Plants

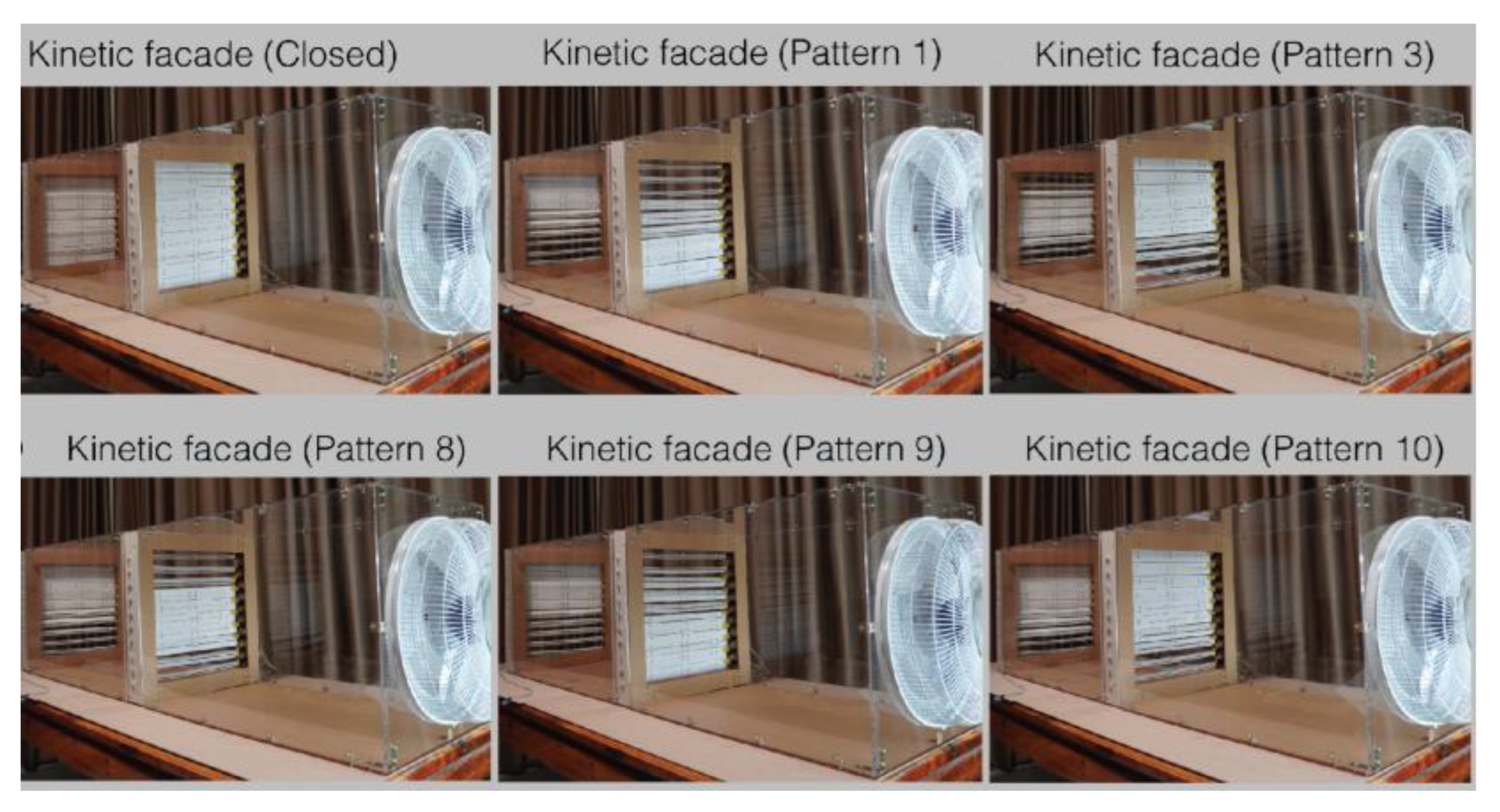

6.1.3. Mimosa Pudica

6.1.4. Stomata

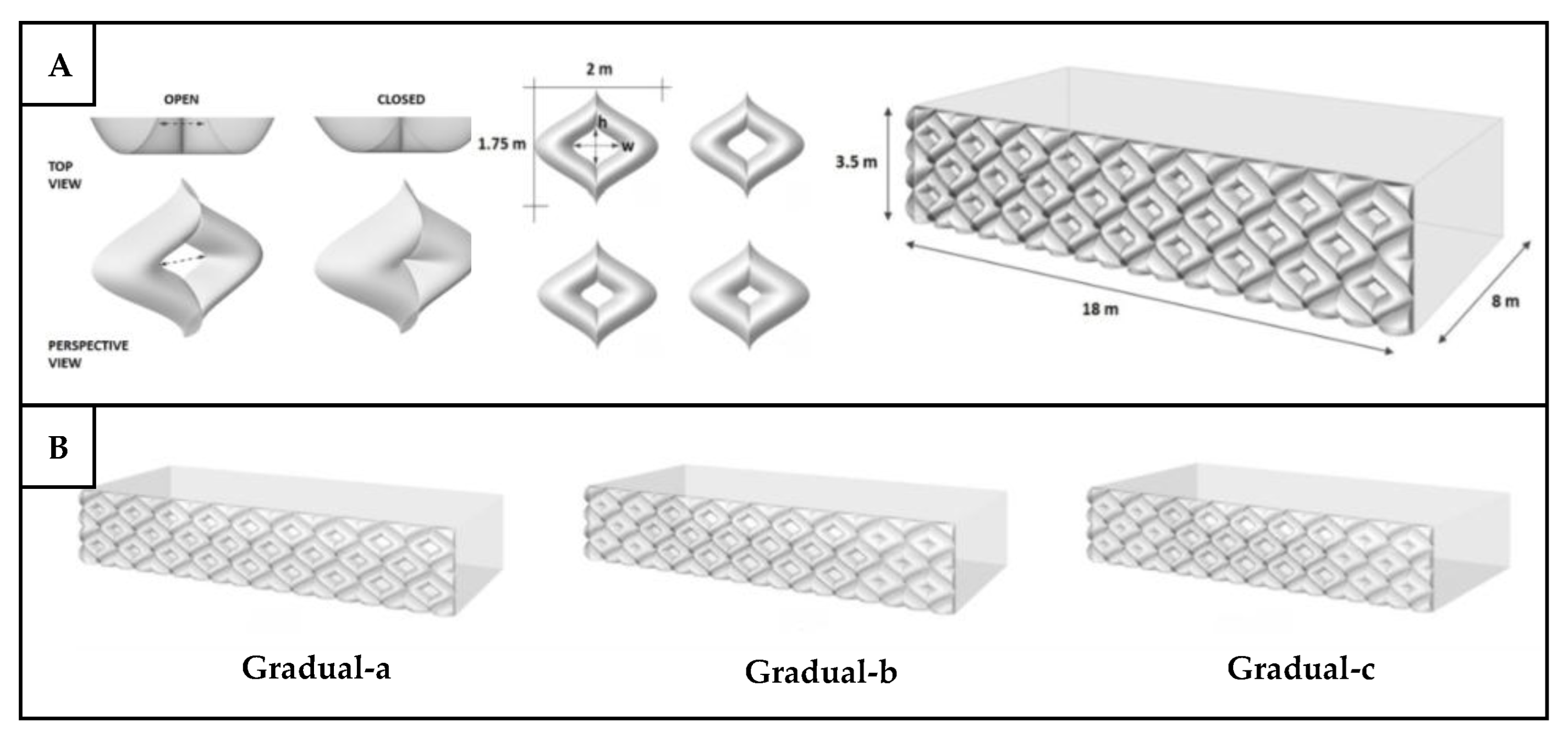

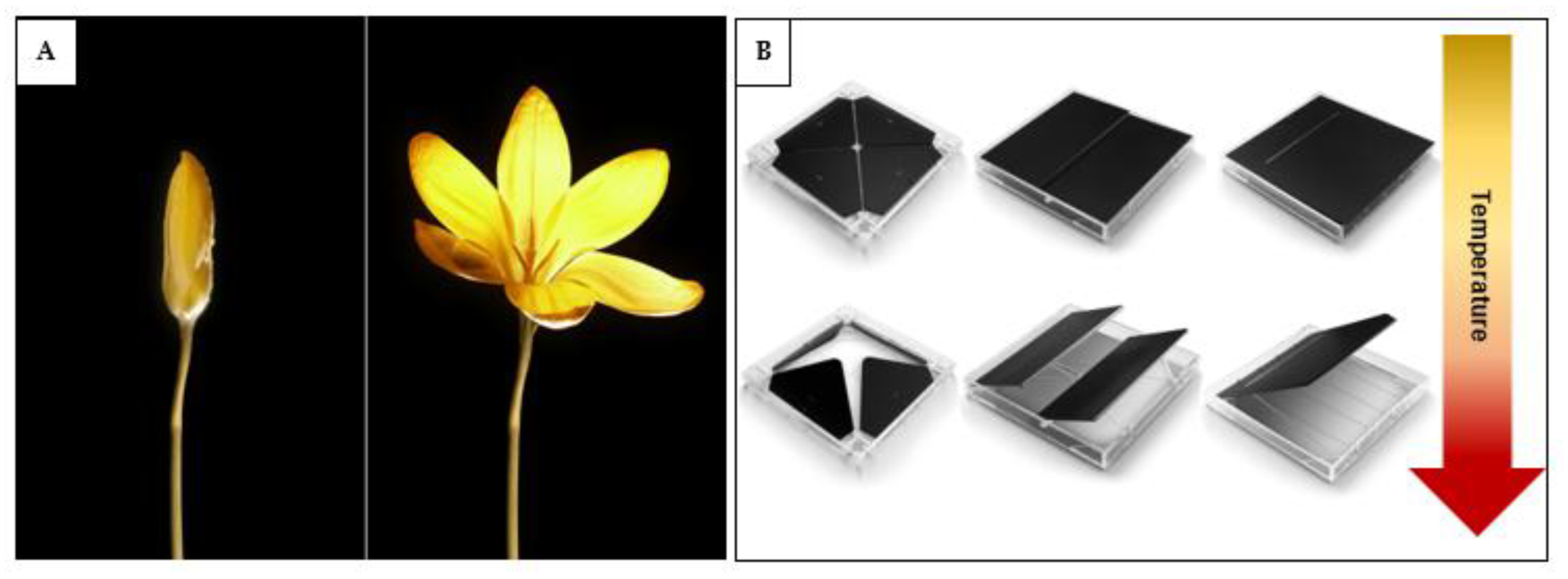

6.1.5. Crocus Flower

6.2. Insights from Simple Aquatic Animals and Lungs

| Source of inspiration | Mimicked features | Applications | Advantages | Challenges/limitations | Study | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine cone | Opening and closing of scales. | Adaptive envelope components for ventilation. | Energy-free operation due to autonomous response to humidity changes; lightweight construction; dynamic environmental adaptation. | Limited user control; reduced sensitivity over time from material fatigue; response time influenced by material thickness and size; performance dependent on geometric shape and arrangement. | [143,144,147,148] | ||

| Ice plant | Opening and closing of its seed capsules. | Adaptive envelope components for ventilation. | Dynamic environmental adaptation; responsive to changing conditions. | Manufacturing/upscaling challenges for large structures; precise synchronization of movements is challenging; risk of malfunction. | [150,151] | ||

| Mimosa pudica | Sensitivity and automatic response to external stimuli. | Kinetic façade that facilitates ventilation. | Enhanced ventilation efficiency; improved indoor air quality and airflow. | Difficult to balance between comfort and air quality. | [152] | ||

| Stomata | Opening and closing of guard cells. | Façade openings for natural ventilation. | Optimum configuration of opening shape and location ensures desirable airflow and occupant comfort. | Not experimentally verified; dependent on wind conditions and direction. | [155] | ||

| Crocus flower | Opening and closing of petals. | Smart and responsive (adaptive) ventilation panels. | Improved natural ventilation; reduced energy use with smart materials. | Requires maintenance; effectiveness decreases with material fatigue; limited temperature response range. | [157] | ||

| Sea sponge & human respiratory system | Active breathing or pumping in and out. | Façade with components that inhale and exhale to provide ventilation. | Improved permeability of envelope but still controllable; improved air velocity distribution and reduced age of air in optimized case. | Complex to manufacture and operate; the use of piezoelectric wire to generate a pressure difference may be inefficient and costly for large-scale buildings. | [159,160] | ||

7. Applications and Integration of Bio-Inspired Ventilation in Off-Earth Habitats and Underground Mines

7.1. Ventilation Challenges in Off-Earth Habitats and Underground Mines

7.2. Bio-Inspired Solutions for Ventilation in Off-Earth Habitats and Underground Mines

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- González-Torres, M.; Pérez-Lombard, L.; Coronel, J.F.; Maestre, I.R.; Yan, D. A Review on Buildings Energy Information: Trends, End-Uses, Fuels and Drivers. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 626–637. [CrossRef]

- Sara, K.; Noureddine, Z. A Bio Problem-Solver for Supporting the Design, towards the Optimization of the Energy Efficiency. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th International Conference on Modeling, Simulation, and Applied Optimization (ICMSAO), Istanbul, Turkey, 27-29 May 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–6.

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Xin, Y.; He, T.; Zhao, G. A Review of Studies Involving the Effects of Climate Change on the Energy Consumption for Building Heating and Cooling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 18, 40. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Kumar, P.; Mottet, L. Natural Ventilation in Warm Climates: The Challenges of Thermal Comfort, Heatwave Resilience and Indoor Air Quality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 138, 110669. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, D.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Setunge, S.; Shi, L. A Critical Review of Combined Natural Ventilation Techniques in Sustainable Buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110795. [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M. Subsurface Ventilation Engineering, Mine Ventilation Services. Inc Fresno 2009.

- Wen, J.; Zuo, J.; Wang, Z.; Wen, Z.; Wang, J. Failure Mechanism Analysis and Support Strength Determination of Deep Coal Mine Roadways – A Case Study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 443, 137704. [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, D.J.; Mathews, M.J.; Maré, P.; Kleingeld, M.; Arndt, D. Evaluating the Impact of Auxiliary Fan Practices on Localised Subsurface Ventilation. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2019, 29, 933–941. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, J.; Xue, Y.; Wen, L.; Shi, D. Optimization of Airflow Distribution in Mine Ventilation Networks Using the Modified Sooty Tern Optimization Algorithm. Min. Metall. Explor. 2024, 41, 239–257. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, K.; Prosser, B.; Stinnette, J.D. The Practice of Mine Ventilation Engineering. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 165–169. [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, S.G.; Kocsis, C.K. Mining at Depth▲ The Ventilation Challenge. Des. Methods 2004, 51.

- Halim, A. Ventilation Requirements for Diesel Equipment in Underground Mines–Are We Using the Correct Values. In Proceedings of the 16th North American Mine Ventilation Symposium, Golden, CO, USA, 17-22 June 2017; SME: Colorado, USA; Vol. 27, pp. 1–7.

- von Einem, M.; Groll, R.; Heinicke, C. Computational Modeling of a Ventilation Concept for a Lunar Habitat Laboratory. J. Space Saf. Eng. 2022, 9, 145–153. [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, M.-R.; Meslem, A.; Nastase, I.; Sandu, M.; Bode, F. Experimental Study of Carbon Dioxide Accumulation on a Model of the Crew Quarters on the ISS. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on ENERGY and ENVIRONMENT (CIEM), Timisoara, Romania, 17-18 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 269–273.

- Georgescu, M.R.; Meslem, A.; Nastase, I.; Tacutu, L. An Alternative Air Distribution Solution for Better Environmental Quality in the ISS Crew Quarters. Int. J. Vent. 2023, 22, 24–39. [CrossRef]

- James, J.T. The Headache of Carbon Dioxide Exposures. In proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), Chicago, IL, USA, 9–12 July 2007; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 411-416.

- Son, C.H.; Zapata, J.L.; Lin, C.-H. Investigation of Airflow and Accumulation of Carbon Dioxide in the Service Module Crew Quarters. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), San Antonio, TX, USA, 15–18 July 2002; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2002; 2002-01–2341.

- Broyan, J.L.; Borrego, M.A.; Bahr, J.F. International Space Station USOS Crew Quarters Development. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), San Francisco, CA, USA, 29 June–3 July 2008; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2008; 08ICES-0222. [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, M.-R.; Nastase, I.; Meslem, A.; Sandu, M.; Bode, F. Design of a Small-Scale Experimental Model of the International Space Station Crew Quarters for a PIV Flow Field Study. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; 2019; Vol. 111, p. 01045.

- Sandu, M.; Nastase, I.; Bode, F.; Croitoru, C.; Tacutu, L. Preliminary Study on a Reduced Scaled Model Regarding the Air Diffusion inside a Crew Quarter on Board of the ISS. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 32, 01015.

- Bode, F.; Nastase, I.; Croitoru, C.; Sandu, M.; Dogeanu, A.; Ursu, I. Preliminary Numerical Studies for the Improvement of the Ventilation System of the Crew Quarters on Board of the International Space Station. INCAS Bull. 2018, 10, 137–143.

- Jernigan, M.; Gatens, R.; Perry, J.; Joshi, J. The next Steps for Environmental Control and Life Support Systems Development for Deep Space Exploration. In Proceedings of the 48th International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), Albuquerque, NM, USA, 8–12 July 2018; ICES: USA, 2018; ICES-2018-276.

- Shaw, L.; Garr, J.; Gavin, L.; Hornyak, D.; Matty, C.; Ridley, A.; Salopek, M.; Toon, K. International Space Station as a Testbed for Exploration Environmental Control and Life Support Systems 2021 Status. In Proceedings of the 50th International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), 2021; ICES: 2021; ICES-2021-20.

- Karaarslan-Semiz, G. Education for Sustainable Development in Primary and Secondary Schools: Pedagogical and Practical Approaches for Teachers; Springer Nature, 2022; ISBN 978-3-031-09112-4.

- Pawlyn, M. Biomimicry in Architecture; Riba Publishing, 2019; ISBN 0-429-34677-8.

- Khelil, S.; Zemmouri, N. Biomimetic: A New Strategy for a Passive Sustainable Ventilation System Design in Hot and Arid Regions. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 2821–2830. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, E. Biomimicry: A New Approach to Enhance the Efficiency of Natural Ventilation Systems in Hot Climate.; 2010.

- Lunau, K.; Konzmann, S.; Bossems, J.; Harpke, D. A Matter of Contrast: Yellow Flower Colour Constrains Style Length in Crocus Species. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0154728. [CrossRef]

- Harrington, M.J.; Razghandi, K.; Ditsch, F.; Guiducci, L.; Rueggeberg, M.; Dunlop, J.W.C.; Fratzl, P.; Neinhuis, C.; Burgert, I. Origami-like Unfolding of Hydro-Actuated Ice Plant Seed Capsules. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 337. [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Pirosa, A.; Yang, W.; Ritchie, R.O.; Meyers, M.A. Hydration-Induced Reversible Deformation of the Pine Cone. Acta Biomater. 2021, 128, 370–383. [CrossRef]

- Siirila, A. Black-Tailed Prairie Dog. Wikimedia Commons. 2007. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prairie_Dog_Washington_DC_1.jpg (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Ocean Explorer Sponges in Caribbean Sea, Cayman Islands in Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons. 2010. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sponges_in_Caribbean_Sea,_Cayman_Islands.jpg (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Vengolis Mimosa Pudica in Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons. 2020. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mimosa_pudica_04215.jpg (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Cosarinsky, M.I.; Roces, F. The Construction of Turrets for Nest Ventilation in the Grass-Cutting Ant Atta Vollenweideri: Import and Assembly of Building Materials. J. Insect Behav. 2012, 25, 222–241. [CrossRef]

- Gomon, M.F.; Bray, D.J. Perca Fluviatilis in Fishes of Australia. 2024. Available online: https://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/3690 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Hoffman, D. Bamboo. Flickr. 2014. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/universalpops/12770331525 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Fu, S.C.; Zhong, X.L.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, T.W.; Chan, K.C.; Lee, K.Y.; Chao, C.Y.H. Bio-Inspired Cooling Technologies and the Applications in Buildings. Energy Build. 2020, 225, 110313. [CrossRef]

- Shashwat, S.; Zingre, K.T.; Thurairajah, N.; Kumar, D.K.; Panicker, K.; Anand, P.; Wan, M.P. A Review on Bioinspired Strategies for an Energy-Efficient Built Environment. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113382. [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Shi, B.; Jiang, M.; Fu, B.; Song, C.; Tao, P.; Shang, W.; Deng, T. Biological and Bioinspired Thermal Energy Regulation and Utilization. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 7081–7118. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Said, I.; Ossen, D.R. Applications of Thermoregulation Adaptive Technique of Form in Nature into Architecture: A Review. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 719–724. [CrossRef]

- Canuckguy World Map (BlankMap-World). Wikimedia Commons. 2006. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BlankMap-World.svg (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Paar, M.J.; Petutschnigg, A. Biomimetic Inspired, Natural Ventilated Façade – A Conceptual Study. J. Facade Des. Eng. 2017, 4, 131–142.

- AbdUllah, A.; Said, I.B.; Ossen, D.R. Cooling Strategies in The Biological Systems and Termite Mound: The Potential of Emulating Them to Sustainable Architecture and Bionic Engineering. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2018, 13, 8127–8141.

- Kleineidam, C.; Ernst, R.; Roces, F. Wind-Induced Ventilation of the Giant Nests of the Leaf-Cutting Ant Atta Vollenweideri. Naturwissenschaften 2001, 88, 301–305. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, H.; Tu, D. Effect of Mechanical Ventilation and Natural Ventilation on Indoor Climates in Urumqi Residential Buildings. Build. Environ. 2018, 144, 108–118. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Fu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, P.; He, X. Rapid Urbanization and Climate Change Significantly Contribute to Worsening Urban Human Thermal Comfort: A National 183-City, 26-Year Study in China. Urban Clim. 2022, 43, 101154. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, C.; Qian, Q.K.; Huang, R.; You, K.; Visscher, H.; Zhang, G. Incentive Initiatives on Energy-Efficient Renovation of Existing Buildings towards Carbon–Neutral Blueprints in China: Advancements, Challenges and Prospects. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113343. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Cai, H.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Shi, H. Propagation of Meteorological to Hydrological Drought for Different Climate Regions in China. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 283, 111980. [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Wen, J.; Wong, N.H.; Tan, E. Impact of Façade Design on Indoor Air Temperatures and Cooling Loads in Residential Buildings in the Tropical Climate. Energy Build. 2021, 243, 110972. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.M.A.; Haw, L.C.; Fazlizan, A. A Literature Review of Naturally Ventilated Public Hospital Wards in Tropical Climate Countries for Thermal Comfort and Energy Saving Improvements. Energies 2021, 14, 435. [CrossRef]

- Sari, D.P. A Review of How Building Mitigates the Urban Heat Island in Indonesia and Tropical Cities. Earth 2021, 2, 653–666. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Zhu, R.; Tong, S.; Mei, S.; Zhu, W. Impact of Anthropogenic Heat from Air-Conditioning on Air Temperature of Naturally Ventilated Apartments at High-Density Tropical Cities. Energy Build. 2022, 268, 112171. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Yecko, P. Bio-Inspired Passive Ventilation for Underground Networks. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Mathematical Modeling in Physical Sciences, Belgrade, Serbia, 5–8 September 2022; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2022; 2872, 020010.

- Parr, D.R.G. Biomimetic Lessons for Natural Ventilation of Buildings: A Collection of Biomimicry Templates Including Their Simulation and Application. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference, Living Machines, London, UK, 29 July-02 August, 2013; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; Vol. 8064, pp. 421–423.

- Alyahya, A.; Lannon, S.; Jabi, W. Biomimetic Opaque Ventilated Façade for Low-Rise Buildings in Hot Arid Climate. Buildings 2025, 15, 2491. [CrossRef]

- Waheeb, M.I.; Hemeida, F.A.; Mohamed, A.F. Improving Thermal Comfort Using Biomimicry in the Urban Residential Districts in New Aswan City, Egypt. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Lu, J.; Liu, Z.; Jing, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cui, X.; Wang, H. A Novel Bio-Inspired Ducted Wind Turbine: From Prairie Dog Burrow Architecture to Aerodynamic Performance Optimization. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 123941. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Jiao, L.; Lu, J.; Liu, Z.; Jing, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cui, X.; Wang, H. Optimized Empty Duct Geometry for Ducted Wind Turbines: A Prairie Dog Burrow-Inspired Approach. Energy 2025, 335, 137950. [CrossRef]

- Lüscher, M. Air-Conditioned Termite Nests. Sci. Am. 1961, 205, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.S.; Soar, R.C. Beyond Biomimicry: What Termites Can Tell Us about Realizing the Living Building. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Industrialized, Intelligent Construction (I3CON), Loughborough, United Kingdom, 14-16 May 2008; Loughborough University: Loughborough, UK, 2008; pp. 1–18.

- Noirot, C.; Darlington, J.P.E.C. Termite Nests: Architecture, Regulation and Defence. In Termites: Evolution, Sociality, Symbioses, Ecology; Abe, T., Bignell, D.E., Higashi, M., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2000; pp. 121–139 ISBN 978-90-481-5476-0.

- King, H.; Ocko, S.; Mahadevan, L. Termite Mounds Harness Diurnal Temperature Oscillations for Ventilation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 11589–11593. [CrossRef]

- Ocko, S.A.; King, H.; Andreen, D.; Bardunias, P.; Turner, J.S.; Soar, R.; Mahadevan, L. Solar-Powered Ventilation of African Termite Mounds. J. Exp. Biol. 2017, 220, 3260–3269. [CrossRef]

- Verbrugghe, N.; Rubinacci, E.; Khan, A.Z. Biomimicry in Architecture: A Review of Definitions, Case Studies, and Design Methods. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 107. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Yu, X.; Yang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Xiang, B.; Wang, Y. Bionic Building Energy Efficiency and Bionic Green Architecture: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 771–787. [CrossRef]

- Claggett, N.; Surovek, A.; Capehart, W.; Shahbazi, K. Termite Mounds: Bioinspired Examination of the Role of Material and Environment in Multifunctional Structural Forms. J. Struct. Eng. 2018, 144, 02518001. [CrossRef]

- Ramasam, N.G.; Kaviarasu, V.; Adarsh, V.; Rohithraman, R. Termite Mould Building – A Comparative Study on Bio-Memetics Model. in Proceedings of the Advancements in Materials for Civil Engineering Applications, Kattankulathur, India, 9–11 March 2023; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2024; p. 030017.

- Alleyne, M. The Termite Mound: A Not-Quite-True Popular Bioinspiration Story. 2013. Available online: https://insectsdiditfirst.com/2013/09/18/the-termite-mound-a-not-quite-true-popular-bioinspiration-story/ (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- ElDin, N.N.; Abdou, A.; ElGawad, I.A. Biomimetic Potentials for Building Envelope Adaptation in Egypt. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 34, 375–386. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Simulation and Optimization Study on the Ventilation Performance of High-Rise Buildings Inspired by the White Termite Mound Chamber Structure. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 607. [CrossRef]

- Andréen, D.; Soar, R. Termite-Inspired Metamaterials for Flow-Active Building Envelopes. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1126974. [CrossRef]

- Hölldobler, B.; Wilson, E.O. The Ants; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1990;

- Jonkman, J.C.M. The External and Internal Structure and Growth of Nests of the Leaf-cutting Ant Atta Vollenweideri Forel, 1893 (Hym.: Formicidae): Part I1. Z. Für Angew. Entomol. 1980, 89, 158–173. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Forti, L.C.; Andrade, A.P.; Boaretto, M.A.; Lopes, J. Nest Architecture of Atta Laevigata (F. Smith, 1858) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Stud. Neotropical Fauna Environ. 2004, 39, 109–116.

- Bollazzi, M.; Forti, L.C.; Roces, F. Ventilation of the Giant Nests of Atta Leaf-Cutting Ants: Does Underground Circulating Air Enter the Fungus Chambers? Insectes Sociaux 2012, 59, 487–498. [CrossRef]

- Bollazzi, M.; Römer, D.; Roces, F. Carbon Dioxide Levels and Ventilation in Acromyrmex Nests: Significance and Evolution of Architectural Innovations in Leaf-Cutting Ants. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 210907. [CrossRef]

- Halboth, F.; Roces, F. The Construction of Ventilation Turrets in Atta Vollenweideri Leaf-Cutting Ants: Carbon Dioxide Levels in the Nest Tunnels, but Not Airflow or Air Humidity, Influence Turret Structure. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0188162. [CrossRef]

- Kleineidam, C.; Roces, F. Carbon Dioxide Concentrations and Nest Ventilation in Nests of the Leaf-Cutting Ant Atta Vollenweideri: Insectes Sociaux 2000, 47, 241–248. [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, R.J.; Cherrett, J.M. Aspects of the Symbiosis of the Leaf-cutting Ant Acromyrmex Octospinosus (Reich) and Its Food Fungus. Ecol. Entomol. 1978, 3, 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Nývlt, V.; Musílek, J.; Čejka, J.; Stopka, O. The Study of Derinkuyu Underground City in Cappadocia Located in Pyroclastic Rock Materials. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 2253–2258. [CrossRef]

- Tsui, E.; Wei, H.D.; Hua, Z.L.; Jie, S.; Su, B.; Tao, H.J. The Global Health Community (Termite’s Nest-Based Apartment Complex Design) Guangzhou, China. World Arch. 2010. Available online: https://warearthissue2010.blogspot.com/2010/08/global-health-community-termites-nest.html (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Yang, G.; Zhou, W.; Qu, W.; Yao, W.; Zhu, P.; Xu, J. A Review of Ant Nests and Their Implications for Architecture. Buildings 2022, 12, 2225. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, L.M. Nature Carved Rock Cappadocia. Wikimedia Commons. 2018. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nature_carved_rock_Cappadocia_03.jpg (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Claggett, N.; Surovek, A.; Capehart, W.; Shahbazi, K. Termite Mounds: Bioinspired Examination of the Role of Material and Environment in Multifunctional Structural Forms. J. Struct. Eng. 2018, 144, 02518001. [CrossRef]

- Marom, G.; Grossbard, S.; Bodek, M.; Neuman, E.; Elad, D. Computational Analysis of a New Biomimetic Active Ventilation Paradigm for Indoor Spaces. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2023, 33, 2710–2729. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-L.; Li, B.; Shang, J.; Wang, W.-W.; Zhao, F.-Y. Airborne Pollutant Removal Effectiveness and Hidden Pollutant Source Identification of Bionic Ventilation Systems: Direct and Inverse CFD Demonstrations. Indoor Air 2023, 2023, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Cuce, P.M.; Riffat, S. A Comprehensive Review of Heat Recovery Systems for Building Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 665–682. [CrossRef]

- Kragh, J.; Rose, J.; Nielsen, T.R.; Svendsen, S. New Counter Flow Heat Exchanger Designed for Ventilation Systems in Cold Climates. Energy Build. 2007, 39, 1151–1158. [CrossRef]

- Zender–Świercz, E. A Review of Heat Recovery in Ventilation. Energies 2021, 14, 1759. [CrossRef]

- Adamu, Z.; Price, A. Natural Ventilation with Heat Recovery: A Biomimetic Concept. Buildings 2015, 5, 405–423. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.H.; West, G.B. Scaling in Biology; Oxford University Press, USA, 2000;

- Niklas, K.J.; Spatz, H.-C. Plant Physics; University of Chicago Press, 2012;

- Lin, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, W.; Lu, X. Analysis of Flow Field and Temperature Distribution in Granary under Novel Ventilation Systems Based on Fractal Structure. Therm. Sci. 2024, 28, 1545–1559. [CrossRef]

- Wei, G. Optimization of Mine Ventilation System Based on Bionics Algorithm. Procedia Eng. 2011, 26, 1614–1619. [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Wang, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Y. Research on Optimization and Regulation of Air Volume in Mine Ventilation Network Based on Multi-Strategy Beetle Swarm Optimization. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 68, 103654. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Dong, J.; Cui, Y. Multi-Objective Intelligent Decision and Linkage Control Algorithm for Mine Ventilation. Energies 2022, 15, 7980. [CrossRef]

- Babu, V.R.; Maity, T.; Burman, S. Energy Saving Possibilities of Mine Ventilation Fan Using Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, and Optimization Techniques (ICEEOT), Chennai, India, 03-05 March 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 676–681.

- Babu, V.R.; Maity, T.; Burman, S. Optimization of Energy Use for Mine Ventilation Fan with Variable Speed Drive. In Proceedings of the 2016 International conference on intelligent control power and instrumentation (ICICPI), Kolkata, India, 21-23 October 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 148–151.

- Lei, B.; Zhao, C.; He, B.; Wu, B. A Study on Source Identification of Gas Explosion in Coal Mines Based on Gas Concentration. Fuel 2021, 290, 120053. [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Xu, G.; Huang, J.; Ma, X. A Mine Main Fans Switchover System with Lower Air Flow Volatility Based on Improved Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2019, 11, 1687814019829281. [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Liao, Y.; Cai, H.; Guo, X.; Zhang, B.; Lin, B.; Zhang, W.; Wei, L.; Tong, Y. Experimental Study on 3D Source Localization in Indoor Environments with Weak Airflow Based on Two Bionic Swarm Intelligence Algorithms. Build. Environ. 2023, 230, 110020. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; He, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Peng, Y. CFD Simulation and Optimization of Ventilation for the Layout of Community Architecture Inspired by Fishbone Form. Int. J. Model. Simul. Sci. Comput. 2023, 14, 2350049. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y. Effect of Wind Speed on Human Thermal Sensation and Thermal Comfort. In Proceedings of MATERIALS SCIENCE, ENERGY TECHNOLOGY AND POWER ENGINEERING II (MEP2018), Hangzhou, China, 14–15 April 2018; AIP Publishing, Melville, NY, USA, 2018; Vol. 1971, p. 030012.

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Chen, X.; Shen, H.; Cao, X.; Gao, H. Simulation and Experimental Study on the Elbow Pressure Loss of Large Air Duct with Different Internal Guide Vanes. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2022, 43, 725–739. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, A.; Che, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y. A Low-Resistance Elbow with a Bionic Sawtooth Guide Vane in Ventilation and Air Conditioning Systems. Build. Simul. 2022, 15, 117–128. [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Liu, K.; Li, A.; Fang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Cong, B. Biomimetic Duct Tee for Reducing the Local Resistance of a Ventilation and Air-Conditioning System. Build. Environ. 2018, 129, 130–141. [CrossRef]

- Harvie-Clark, J.; Conlan, N.; Wei, W.; Siddall, M. How Loud Is Too Loud? Noise from Domestic Mechanical Ventilation Systems. Int. J. Vent. 2019, 18, 303–312. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, X.; Shen, L.; Yang, A.; Chen, E.; Fieldhouse, J.; Barton, D.; Kosarieh, S. Noise Reduction of Automobile Cooling Fan Based on Bio-Inspired Design. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J. Automob. Eng. 2021, 235, 465–478. [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Cui, Q.; Qin, G. Performance Improvement and Noise Reduction Analysis of Multi-Blade Centrifugal Fan Imitating Long-Eared Owl Wing Surface. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 125147. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Mu, Z.; Yin, W.; Li, W.; Niu, S.; Zhang, J.; Ren, L. Biomimetic Multifunctional Surfaces Inspired from Animals. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 234, 27–50. [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, J.W.; Peake, N. Aeroacoustics of Silent Owl Flight. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2020, 52, 395–420. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Lu, X.-Y.; Song, Y.-B.; Bennett, G.J. Bio-Inspired Aerodynamic Noise Control: A Bibliographic Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2224. [CrossRef]

- Fish, F.E.; Weber, P.W.; Murray, M.M.; Howle, L.E. The Tubercles on Humpback Whales’ Flippers: Application of Bio-Inspired Technology. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2011, 51, 203–213. [CrossRef]

- Miklosovic, D.S.; Murray, M.M.; Howle, L.E.; Fish, F.E. Leading-Edge Tubercles Delay Stall on Humpback Whale (Megaptera Novaeangliae) Flippers. Phys. Fluids 2004, 16, L39–L42. [CrossRef]

- Watts, P.; Fish, F.E. The Influence of Passive, Leading Edge Tubercles on Wing Performance. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Unmanned Untethered Submersible Technology, Durham, New Hampshire, USA, 19–22 August 2001; AUSI: New Hampshire, USA, 2001; pp. 2–9.

- Gu, Y.; Xia, K.; Zhang, W.; Mou, J.; Wu, D.; Liu, W.; Xu, M.; Zhou, P.; Ren, Y. Airfoil Profile Surface Drag Reduction Characteristics Based on the Structure of the Mantis Shrimp Abdominal Segment. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2021, 91, 919–932. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, Z.; Yin, W.; Wang, H.; Ge, C.; Jiang, J. Numerical Experiment of the Solid Particle Erosion of Bionic Configuration Blade of Centrifugal Fan. Acta Metall. Sin. Engl. Lett. 2013, 26, 16–24. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Yang, Z.; Ma, F. Bionic Noise Reduction Design of Axial Fan Impeller. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2024, 57, 345501. [CrossRef]

- Tieghi, L.; Czwielong, F.; Barnabei, V.F.; Ocker, C.; Delibra, G.; Becker, S.; Corsini, A. Aerodynamics and Aeroacoustics of Leading Edge Serration in Low-Speed Axial Fans with Forward Skewed Blades. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2024, 146, 021007. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zheng, N.; Zhang, R.; Li, C. Effect of Serrated Trailing-Edge Blades on Aerodynamic Noise of an Axial Fan. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2022, 36, 2937–2948. [CrossRef]

- Le Roy, C.; Debat, V.; Llaurens, V. Adaptive Evolution of Butterfly Wing Shape: From Morphology to Behaviour. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 1261–1281. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Huang, W.; Weng, Q. Kinematic and Aerodynamic Investigation of the Butterfly in Forward Free Flight for the Butterfly-Inspired Flapping Wing Air Vehicle. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2620. [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Xi, G. Effects of Bionic Blades Inspired by the Butterfly Wing on the Aerodynamic Performance and Noise of the Axial Flow Fan Used in Air Conditioner. Int. J. Refrig. 2022, 140, 17–28. [CrossRef]

- Minami, S.; Azuma, A. Various Flying Modes of Wind-Dispersal Seeds. J. Theor. Biol. 2003, 225, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Azuma, A.; Okuno, Y. Flight of a Samara, Alsomitra Macrocarpa. J. Theor. Biol. 1987, 129, 263–274. [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.G.; Foster, J.C.; Ashby, T.A.; Walker, R.K.; Johnson, J.A.; Markin, V.S. Mimosa Pudica : Electrical and Mechanical Stimulation of Plant Movements. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 163–173. [CrossRef]

- Ladera, C.L.; Pineda, P.A. The Physics of the Spectacular Flight of the Triplaris Samaras. Lat.-Am. J. Phys. Educ. 2009, 3, 11.

- Green, D.S. The Terminal Velocity and Dispersal of Spinning Samaras. Am. J. Bot. 1980, 67, 1218–1224.

- McCutchen, C.W. The Spinning Rotation of Ash and Tulip Tree Samaras. Science 1977, 197, 691–692. [CrossRef]

- Gururaj, F.; Vijayakumar, N.; Satish, J.; Madhusudhana, H.K.; Aakash, C.; Siddhi, R. Design and Analysis of Nature-Inspired Design for Ceiling Fan Inspired by Sycamore Seeds to Ensure a More Optimal Air Flow. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Advances in Physical Sciences and Materials (ICAPSM), Coimbatore, India, 17–18 August 2023; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2024; p. 100039.

- Su, L.; Qiang, X.; Zheng, T.; Teng, J. Effect of Undulating Blades on Highly Loaded Compressor Cascade Performance. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J. Power Energy 2020, 235, 17–28. [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Dong, X.; Li, Z.; Sun, Z.; Feng, L. Numerical and Experimental Study on Flow Separation Control of Airfoils with Various Leading-Edge Tubercles. Ocean Eng. 2022, 252, 111046. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Qin, W.; Xi, G. Flow Control Mechanism of Blade Tip Bionic Grooves and Their Influence on Aerodynamic Performance and Noise of Multi-Blade Centrifugal Fan. Energies 2022, 15, 3431. [CrossRef]

- Weger, M.; Wagner, H. Morphological Variations of Leading-Edge Serrations in Owls (Strigiformes). PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0149236. [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.K.; Rezgui, D. Sectional Leading Edge Vortex Lift and Drag Coefficients of Autorotating Samaras. Aerospace 2023, 10, 414. [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Fang, Z.; Li, A.; Liu, K.; Yang, Z.; Cong, B. A Novel Low-Resistance Tee of Ventilation and Air Conditioning Duct Based on Energy Dissipation Control. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 132, 790–800. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-Q.; Han, Z.-W.; Cao, H.-N.; Yin, W.; Niu, S.-C.; Wang, H.-Y. Numerical Analysis of Erosion Caused by Biomimetic Axial Fan Blade. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 2013, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, M.K.; Wang, H.; Hazell, P.J. From Biology to Biomimicry: Using Nature to Build Better Structures – A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 320, 126195. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C.; Vincent, J.F.; Rocca, A.-M. How Pine Cones Open. Nature 1997, 390, 668–668. [CrossRef]

- Reyssat, E.; Mahadevan, L. Hygromorphs: From Pine Cones to Biomimetic Bilayers. J. R. Soc. Interface 2009, 6, 951–957. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Li, R.; Liu, Z.; Peng, H.; Lyu, J. From Adaptive Plant Materials toward Hygro-Actuated Wooden Building Systems: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369, 130479. [CrossRef]

- Correa, D.; Papadopoulou, A.; Guberan, C.; Jhaveri, N.; Reichert, S.; Menges, A.; Tibbits, S. 3D-Printed Wood: Programming Hygroscopic Material Transformations. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2015, 2, 106–116. [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, G.; Baldinelli, G.; Bianconi, F.; Filippucci, M.; Fioravanti, M.; Goli, G.; Rotili, A.; Togni, M. Characterisation of Wood Hygromorphic Panels for Relative Humidity Passive Control. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101829. [CrossRef]

- Reichert, S.; Menges, A.; Correa, D. Meteorosensitive Architecture: Biomimetic Building Skins Based on Materially Embedded and Hygroscopically Enabled Responsiveness. Comput.-Aided Des. 2015, 60, 50–69. [CrossRef]

- Vailati, C.; Hass, P.; Burgert, I.; Rüggeberg, M. Upscaling of Wood Bilayers: Design Principles for Controlling Shape Change and Increasing Moisture Change Rate. Mater. Struct. 2017, 50, 250. [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Rubio, R.; Martín, S.; Ben Croxford How Plants Inspire Façades. From Plants to Architecture: Biomimetic Principles for the Development of Adaptive Architectural Envelopes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 692–703. [CrossRef]

- Krieg, O.D. HygroSkin–Meteorosensitive Pavilion. In Advancing Wood Architecture; Routledge, 2016; pp. 125–138.

- Menges, A.; Reichert, S. Performative Wood: Physically Programming the Responsive Architecture of the HygroScope and HygroSkin Projects. Archit. Des. 2015, 85, 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Guiducci, L.; Razghandi, K.; Bertinetti, L.; Turcaud, S.; Rüggeberg, M.; Weaver, J.C.; Fratzl, P.; Burgert, I.; Dunlop, J.W.C. Honeycomb Actuators Inspired by the Unfolding of Ice Plant Seed Capsules. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0163506. [CrossRef]

- Khosromanesh, R.; Asefi, M. Form-Finding Mechanism Derived from Plant Movement in Response to Environmental Conditions for Building Envelopes. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 51, 101782. [CrossRef]

- Khosromanesh, R.; Asefi, M. Towards an Implementation of Bio-Inspired Hydro-Actuated Building Façade. Intell. Build. Int. 2022, 14, 151–171.

- Sankaewthong, S.; Miyata, K.; Horanont, T.; Xie, H.; Karnjana, J. Mimosa Kinetic Façade: Bio-Inspired Ventilation Leveraging the Mimosa Pudica Mechanism for Enhanced Indoor Air Quality. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 603. [CrossRef]

- Doheny-Adams, T.; Hunt, L.; Franks, P.J.; Beerling, D.J.; Gray, J.E. Genetic Manipulation of Stomatal Density Influences Stomatal Size, Plant Growth and Tolerance to Restricted Water Supply across a Growth Carbon Dioxide Gradient. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 547–555. [CrossRef]

- Franks, P.J.; Beerling, D.J. Maximum Leaf Conductance Driven by CO2 Effects on Stomatal Size and Density over Geologic Time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 10343–10347. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, H. Pneumatic Skin with Adaptive Openings - Adaptive Façade with Opening Control Integrated with CFD for Natural Ventilation. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia: Learning, Prototyping and Adapting (CAADRIA), Beijing, China, 17-19 May 2018; CAADRIA, Hongkong, 2018; pp. 143–151.

- Andrews, F.M. The Effect of Temperature on Flowers. Plant Physiol. 1929, 4, 281–284.

- Payne, A. The Air Flower (ER). LIFT Archit. 2007. Available online: https://www.liftarchitects.com/air-flower (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Deep-Sea Sponge Grounds: Reservoirs of Biodiversity; United Nations Environment Programme, World Conservation Monitoring Centre, World Wide Fund for Nature, Eds.; UNEP regional seas report and studies; World Conservation Monitoring Centre: Cambridge, 2010; ISBN 978-92-807-3081-4.

- Badarnah, L.; Knaack, U. Bio-Inspired Ventilating System for Building Envelopes. In Proceedings of the International Conference of 21st Century: Building Stock Activation, Tokyo, Japan, 5–7 November 2007; TIHEI: Tokyo, Japan; pp 431-438.

- Badarnah, L.; Kadri, U.; Knaack, U. A Bio-Inspired Ventilating Envelope Optimized by Air-Flow Simulations. In Proceedings of the 2008 World Sustainable Building Conference (SB08), Melbourne, Australia, 21-25 September 2008; CSIRO: Melbourne, Australia: pp. 230-237.

- Berville, C.; Georgescu, M.-R.; Năstase, I. Numerical Study of the Air Distribution in the Crew Quarters on Board of the International Space Station. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 85, 02015.

- Bode, F.; Nastase, I.; Croitoru, C.V.; Sandu, M.; Dogeanu, A. A Numerical Analysis of the Air Distribution System for the Ventilation of the Crew Quarters on Board of the International Space Station. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 32, 01006.

- Allen, C.S. International Space Station Acoustics-A Status Report. In Proceedings of the 45th International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), Bellevue, WA, USA, 2015; ICES, 2015; ICES-2015-286.

- Goodman, J.R.; Grosveld, F.W. Acoustics and Noise Control in Space Crew Compartments. 2015, JSC-CN-34152.

- Broyan, J.; Welsh, D.; Cady, S. International Space Station Crew Quarters Ventilation and Acoustic Design Implementation. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 11-15 July 2010; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2010; AIAA 2010-6018 J.

- Koch, L.D.; Stephens, D.; Goodman, J.M.; Mirhashemi, A.; Buerhle, R.; Sutliff, D.L.; Allen, C.S. Spacecraft Cabin Ventilation Fan Research at NASA. In Proceedings of the 30th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Rome, Italy, 4-7 June 2024; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2024.

- Law, J.; Watkins, S.; Alexander, D. In-Flight Carbon Dioxide Exposures and Related Symptoms: Association, Susceptibility, and Operational Implications. NASA Tech. Pap. 2010, 216126, 2010.

- Broyan, J.; Welsh, D.; Cady, S. International Space Station Crew Quarters Ventilation and Acoustic Design Implementation. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 11-15 July 2010; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA 2010; AIAA 2010-6018.

- Wagner, S.; Thomas, G.; Laws, B. An Assessment of Dust Effects on Planetary Surface Systems to Support Exploration Requirements. NASA JSC Report CTSD-AIM-0029, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center: Houston, TX, USA, 20 August 2004.

- Kobrick, R.L.; Agui, J.H. Preparing for Planetary Surface Exploration by Measuring Habitat Dust Intrusion with Filter Tests during an Analogue Mars Mission. Acta Astronaut. 2019, 160, 297–309. [CrossRef]

- He, M.C.; Guo, P.Y. Deep Rock Mass Thermodynamic Effect and Temperature Control Measures. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2013, 32, 2377–2393.

- Nie, X.; Wei, X.; Li, X.; Lu, C. Heat Treatment and Ventilation Optimization in a Deep Mine. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 1529490. [CrossRef]

- Ranjith, P.G.; Zhao, J.; Ju, M.; De Silva, R.V.; Rathnaweera, T.D.; Bandara, A.K. Opportunities and Challenges in Deep Mining: A Brief Review. Engineering 2017, 3, 546–551. [CrossRef]

- Demirel, N. Energy-Efficient Mine Ventilation Practices. In Energy Efficiency in the Minerals Industry; Awuah-Offei, K., Ed.; Green Energy and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 287–299 ISBN 978-3-319-54198-3.

- Costa, L. de V.; Silva, J.M. da Strategies Used to Control the Costs of Underground Ventilation in Some Brazilian Mines. REM-Int. Eng. J. 2020, 73, 555–560.

- Kamyar, A.; Aminossadati, S.M.; Leonardi, C.; Sasmito, A. Current Developments and Challenges of Underground Mine Ventilation and Cooling Methods. In Proceedings of the 2016 Coal Operators' Conference, Wollongong, Australia, 18-20 February 2019; University of Wollongong: Wollongong, Australia; pp. 277-287.

- Acuña, E.I.; Lowndes, I.S. A Review of Primary Mine Ventilation System Optimization. Interfaces 2014, 44, 163–175. [CrossRef]

- Pouresmaieli, M.; Ataei, M.; Qarahasanlou, A.N.; Barabadi, A. Integration of Renewable Energy and Sustainable Development with Strategic Planning in the Mining Industry. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101412. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, E. Cost Saving Strategies in Mine Ventilation. CIM J. 2018, 9, 2018.

- De Vilhena Costa, L.; Margarida Da Silva, J. Cost-Saving Electrical Energy Consumption in Underground Ventilation by the Use of Ventilation on Demand. Min. Technol. 2020, 129, 1–8.

- Palchak, D.; Cochran, J.; Deshmukh, R.; Ehlen, A.; Soonee, R.; Narasimhan, S.; Joshi, M.; McBennett, B.; Milligan, M.; Sreedharan, P. Greening the Grid: Pathways to Integrate 175 Gigawatts of Renewable Energy into India’s Electric Grid, Vol. I—National Study. 2017.

- Stockman, B.; Boyle, J.; Bacon, International Space Station Systems Engineering. Case Study; Defense Technical Information Center: Fort Belvoir, VA, 2010.

- Georgescu, M.R.; Meslem, A.; Nastase, I. Accumulation and Spatial Distribution of CO2 in the Astronaut’s Crew Quarters on the International Space Station. Build. Environ. 2020, 185, 107278. [CrossRef]

| Biomimicry-related keywords | Boolean | Subject-related keywords |

|---|---|---|

| bio-inspired* OR bioinspired* OR biomimetic* OR bioinspiration* OR bio-inspiration* OR nature-inspired* OR nature-based* OR biomimicry* OR bio-design* OR bionic* OR organism-inspired* OR plant-inspired* | AND | vent* OR fan* |

| duct* | ||

| air AND regulat* | ||

| wall* OR envelope* | ||

| air AND circulat* | ||

| bio-inspired* OR bioinspired* OR biomimetic* OR bioinspiration* OR bio-inspiration* OR nature-inspired* OR nature-based* OR biomimicry* OR bio-design* OR bionic* OR organism-inspired* OR plant-inspired* | AND | HVAC* OR “heating ventilation and air conditioning” |

| Criteria for inclusion | Criteria for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Documents published between 2000 and 2025 inclusive | Duplicate studies or multiple reports from the same research with no additional data or insights |

| Studies on ventilation for the indoor and outdoor environment | Studies lacking bio-inspired designs/strategies |

| Studies relevant to ventilation systems and their components | Documents written in other languages or containing a significant portion of confusing and unintelligible discussions |

| Studies considered important for improving the ventilation systems, even if they are not solely focused on ventilation | Pure review studies that do not present new conceptual designs |

| Written in English language | Only a small portion of the study is relevant to the ventilation systems, or it is not deemed significant for the improvement of the ventilation systems. |

| Source of inspiration | Mimicked features | Applications | Advantages | Challenges/limitations | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prairie dog burrow | Height difference between entrance and exit to the burrow. | Ventilated façade with upper and lower openings or with random extruded openings. | Improved airflow speed within the slot; reduced wall surface temperature; reduced cooling load; improved energy saving. | Climate/wind dependency; manufacturing and upscaling challenges of the complex extruded openings; unverified across building types/heights. | [42,55] |

| Prairie dog burrow | Asymmetric height, shape, and size of openings. | Entrances and exits to subway tunnels. | Higher air exchange and flow rate; improved natural ventilation. | Implementation for complex, interconnected tunnel networks is challenging and may be less effective in practice; the effect of urban microclimate is overlooked. | [53] |

| Prairie dog burrow | Pressure difference due to the strategic placement of openings. | Strategic building orientation and layout to generate a pressure difference. | Improved natural ventilation and thermal comfort; reduced cooling load and energy consumption. | Ineffective in extreme cold; unsuitable for buildings with multiple attached blocks. | [56] |

| Prairie dog burrow | Elevated entrance and convergent-divergent channels. | Duct with contraction-expansion sections and protrusions. | Increased mass flow rate; accelerated airflow; reduced turbulent kinetic energy. | Structural complexity; protrusions and sudden geometric changes may cause noise, vibration, and flow instability. | [57,58] |

| Termite mound | Thermosiphon flow and wind-induced ventilation. | Buildings with chimneys and lower openings; multi-chamber systems connected to occupied spaces and external air. | Reduced cooling load and reliance on air conditioning; lower energy consumption; cooler indoor temperatures; increased airflow rate and speed. | Application in high-rise buildings still relies on fans; sensitive to wind availability; performance depends heavily on geometry and weather conditions. | [26,43,60,64,65,67,68,84] |

| Termite mound | Reticulated tunnels and surface conduits. | Artificial surface conduits or reticulated tunnels that connect the indoor and outdoor environment. | Improved natural ventilation and cooling of living spaces using wind. | Dependence on wind availability and weather conditions; limited control over airflow may cause drafts and discomfort (in a fully passive system); manufacturing challenges for real-scale buildings. | [60,71] |

| Ant nest | Top turrets and lower openings. | Underground or buried habitat. | Enhanced passive ventilation; more stable indoor thermal conditions. | Construction complexity; high maintenance; risk of flooding. | [75,77,80,82] |

| Source of inspiration | Mimicked features | Applications | Advantages | Challenges/limitations | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beetle (swarm) | Behavioral patterns. | Algorithm for underground mine ventilation optimization. | Reduced energy use; high accuracy; stable convergence; improved volumetric flow. | Requires a longer time for convergence or optimization. | [95] |

| Beetle (swarm) | Foraging mechanisms. | Algorithm for underground mine ventilation optimization. | Faster convergence and good optimization. | Lower accuracy. | [95] |

| Animal social behavior | Collective behavior, such as the flocking of birds or schooling of fish. | Algorithm for underground mine ventilation optimization. | Balanced convergence accuracy and efficiency; suitable for large-scale ventilation systems. | Complex real mine conditions and sensor errors may reduce the reliability of the algorithm. | [96] |

| Animal social behavior | Collective behavior, such as the flocking of birds or schooling of fish. | Optimization of mine fan switchover | Reduced airflow volatility; improved safety and efficiency during the switchover. | Airflow fluctuations still occur during the switchover when some doors are almost fully closed or open. | [100] |

| Ant colony | The foraging mechanism of ant colonies to find the shortest path to food. | Algorithm for underground mine ventilation optimization. | Applicable to new and old mines; reduced ventilation cost; optimizes airway use. | Limited validation in real mines; simplified assumptions. | [94] |

| Humpback whale | Hunting behavior | Algorithm for pollutant source identification. | Higher success rate; can prevent robots from getting stuck in a local extremum area. | Required more localization steps; prone to premature convergence. | [101] |

| Fish | Fishbone shape | Building layouts and heights. | Improved pedestrian wind comfort; reduced static zones; improved natural ventilation; lowered wind pressure on windward buildings. | The effect on occupants’ thermal comfort is not assessed; performance indicators such as age of air, temperature, and humidity are not included. | [102] |

| Bat wings and whale pectoral fins | Sawtooth structures | Guide vanes for ventilation ducts. | Reduced local resistance coefficient; improved uniformity of the velocity distribution. | Resistance reduction depends on duct dimensions; local resistance is based on the average value; the noise effect is not considered. | [105] |

| Tree branch | Protrusions | Ventilation ducts. | Reduced resistance and energy consumption; smaller energy dissipation rate. | Excessive protrusions can cause flow deformation and increase resistance instead of reducing it. | [106,136] |

| Owl wings, whale fins, mantis shrimp, desert scorpion | Wavy/sinusoidal/non-smooth structures | Ventilation fans. | Reduced flow resistance; lower turbulent kinetic energy; reduced noise. | Performance and effectiveness depend on fan types, placement, and component types. | [108,109,110,111,113,115,116,119,137] |

| Challenges | Context | Relevant solutions | Integration/Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal comfort issue - heat | Off-Earth habitats | Temperature-responsive ventilation panels that open or close autonomously with the increase or decrease in temperature levels. | Integrated into habitat walls or panels to regulate airflow and heat autonomously. |

| Thermal comfort issue - humidity | Off-Earth habitats | Humidity-sensitive components or wall systems that adjust permeability depending on the humidity levels. | Integrated into wall panels or habitat envelopes for passive humidity regulation. |

| Air mixing issue | Off-Earth habitats | Manipulating the height and shape differences between the inlet and outlet openings so that a greater pressure difference can be generated to increase the airflow; using a time-periodic ventilation supply instead of a steady supply. | Incorporated into the habitat duct layouts or the inlet and outlet openings. |

| CO2 build-up issue | Off-Earth habitats | Ventilation system or components that are responsive to the CO₂ level. | Sensor-actuator system integrated into adaptive ventilation to detect regions with low CO₂ concentration and supply air based on demand. |

| Air mixing issue | Underground mines | Height, size, and shape differences between tunnel entry/exit; venturi-shaped openings at tunnel entrances or exits located at higher elevations; time-periodic ventilation supply. | Integrated into mine tunnel designs and auxiliary ventilation systems to enhance airflow. |

| Air mixing and power consumption issue | Underground mines | Nature-inspired algorithms to balance ventilation demand, safety, and energy use. | Implemented in real-time mine ventilation control systems or in fan operation systems. |

| Power consumption issue | Underground mines | Heat recovery ventilation to capture waste heat from the exhaust air and reuse it to warm the intake air in cold regions. | Integrated into mine HVAC and heating systems. |

| Resistance issue | Underground mines and off-Earth habitats | Duct geometry modifications (protrusions and sawtooth guide vanes). | Applied in junctions, tees, and bends to reduce airflow resistance and save more energy (power). |

| Noise issue | Underground mines and off-Earth habitats | Sawtooth or non-smooth structures in ventilation fans. | Incorporated into appropriate components and locations of ventilation fans. |

| Dust issue | Underground mines and off-Earth habitat | Lotus-inspired dust-repellent surface materials. | Applied to duct linings and filter housings to minimize dust accumulation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).