1. Introduction

Mitochondrial disorders affect approximately one in 5,000 individuals worldwide and often arise from heteroplasmic point mutations in mtDNA that impair oxidative phosphorylation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The m.8993T>G transversion in the MT-ATP6 gene disrupts the proton channel of ATP synthase, causing neuropathy, ataxia, and retinal degeneration at high mutant loads [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Conventional gene therapies cannot target mtDNA because there is no endogenous mechanism for guide RNA import into mitochondria [

4,

8,

9]. Alternative strategies such as mitoTALENs, zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), and allotopic expression have been explored to address mtDNA mutations, but these approaches often rely on double-strand breaks or nuclear re-targeting and have shown limited efficiency or safety concerns in patient-derived models.

A major advance came when Mok and colleagues demonstrated that split halves of the bacterial deaminase DddA, each fused to programmable TALE arrays and a mitochondrial targeting sequence, can catalyze C·G→T·A conversions in mtDNA without introducing double-strand breaks [

7]. In HEK293 cells, they achieved up to 15% editing at mitochondrial loci [

7]. However, that proof of concept has not yet been applied to patient-derived cells harboring pathogenic heteroplasmic mutations. This holds promise for autologous stem cell therapies in mitochondrial disorders.

In this study, we optimized DdCBE design and delivery to correct the m.8993T>G mutation in iPSCs reprogrammed from a NARP patient’s fibroblasts. We quantified on- and off-target editing by deep sequencing, measured shifts in heteroplasmy, evaluated functional rescue of oxidative phosphorylation through Seahorse assays and mitochondrial ATP production, tested neural differentiation efficiency, and examined stability of edits over a 30-day culture period.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Editor Construction

A split DddA-derived cytosine base editor was constructed by fusing each half of DddAtox (residues 1264–1421 and 1422–1550) to a 25-amino-acid COX8A mitochondrial targeting sequence, a programmable TALE domain recognizing 16 bp flanking mt-ATP6 position 8993, a Cas9 D10A nickase, flexible GGS linkers, and a C-terminal HA tag. All coding cassettes were synthesized (GenScript), cloned under the EF1α promoter in pUC5,7 and verified by Sanger sequencing. TALE binding motifs were selected to flank position 8993 of MT-ATP6 with minimal predicted secondary structure and optimal spacing for DdCBE activity, consistent with prior design rules for mitochondrial TALE arrays [

14]. Predicted off-target sites were identified using computational scanning for closely related 16 bp motifs within the mitochondrial genome, and the top ten candidates with the highest sequence similarity were selected for targeted sequencing [

15,

16].

2.2. Cell Culture and Reprogramming

Dermal fibroblasts from a NARP patient (initial heteroplasmy 80 ± 2%) were reprogrammed into iPSCs using Sendai-virus Yamanaka factors (CytoTune-iPS 2.0) and maintained on Matrigel in mTeSR1 medium.

2.3. Delivery and DNA Analysis

For editing, 1 × 10^6 iPSCs at ~60 percent confluence were nucleofected with 1 µg of each editor half (Lonza 4D-Nucleofector, P3 kit, program CM-137) and replated with 10 µM Y-27632 for 24 hours. At days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 30 post-transfection, total DNA was extracted (Qiagen DNeasy) and a 300 bp fragment spanning mt-ATP6 position 8993 was amplified (Phusion HF). Libraries were prepared with NEBNext Ultra II reagents and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq (2 × 250 bp). CRISPResso2 was used to quantify C·G→T·A editing efficiencies and heteroplasmy shifts.

2.4. Protein Expression and Localization

Protein expression of editor halves was confirmed by Western blot (anti-HA 1:2 000, Cell Signaling; anti-GAPDH 1:5 000, Abcam) and densitometry in ImageJ. Mitochondrial localization was verified by anti-HA immunofluorescence co-stained with MitoTracker.

2.5. Bioenergetic Assays

For bioenergetic assays, 40,000 cells per well were assayed on a Seahorse XF96 instrument: basal OCR was measured, followed by sequential injections of oligomycin (1 µM), FCCP (0.5 µM), and rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 µM each), with triplicate wells per condition across three independent experiments.

2.6. ATP Production Assay

Mitochondria were isolated (Thermo Fisher kit) and ATP production quantified using ATPlite (PerkinElmer), normalized to mitochondrial protein (BCA assay).

2.7. Neural Differentiation

For neural differentiation, edited and control iPSCs underwent dual-SMAD inhibition (SB431542 10 µM, LDN-193189 100 nM) for 7 days, fixed in 4 percent paraformaldehyde, stained for Nestin (1:500, Millipore) and DAPI, and five random fields per sample were imaged; Nestin-positive nuclei were quantified in CellProfiler.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as mean ± SD from a minimum of three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Each experiment, including editing efficiency assays, Seahorse OCR analysis, ATP production assays, and neural differentiation, was independently reproduced at least three times with consistent results. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests (GraphPad Prism) were used, with p < 0.05 considered significant.

3. Results

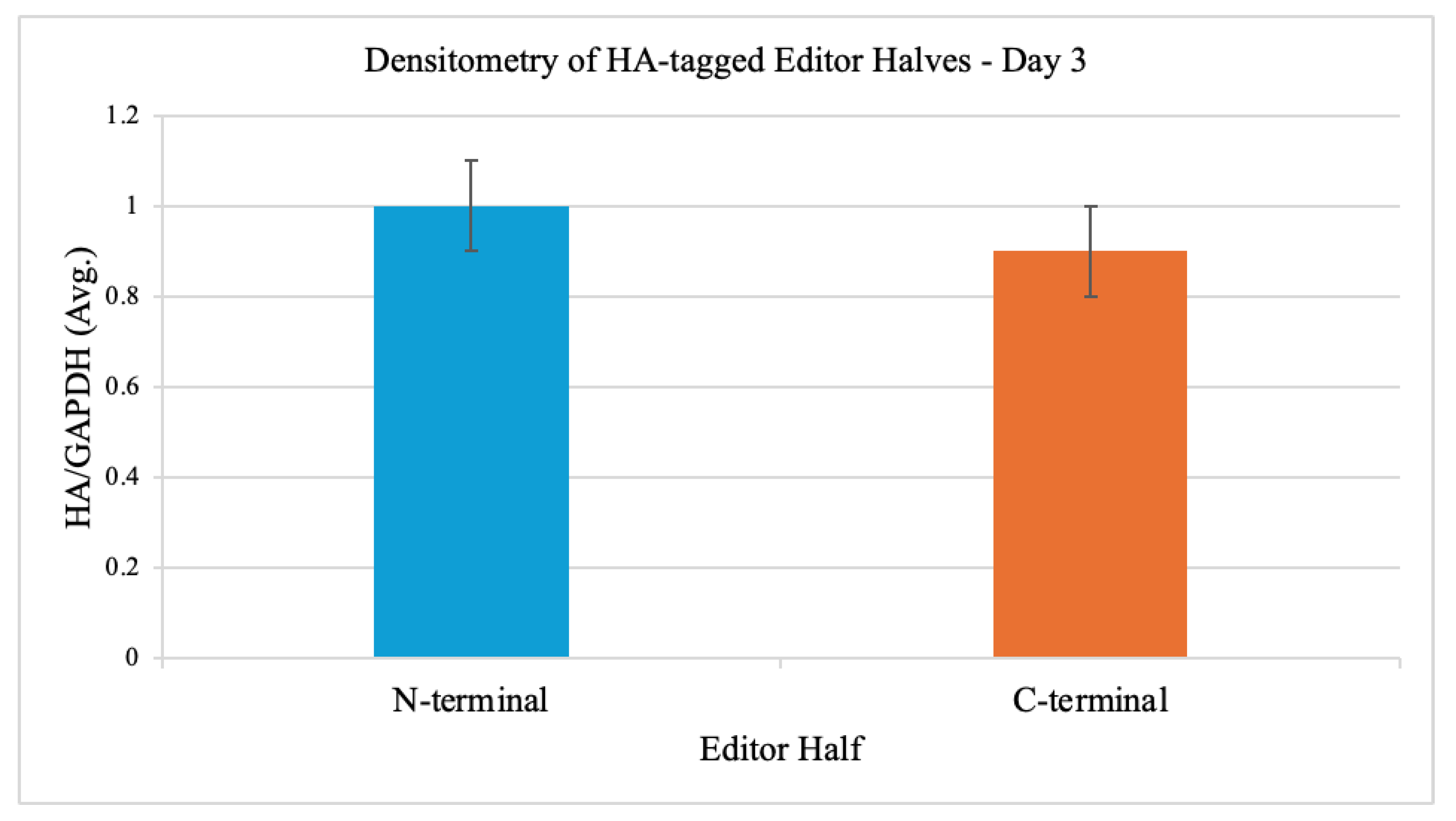

3.1. Editor Expression and Localization

Western blot analysis at day 3 post-transfection confirmed robust expression of both editor halves in iPSCs. Densitometry of HA signal normalized to GAPDH yielded comparable levels for the N-terminal and C-terminal halves (

Figure 1). Immunofluorescence co-staining with anti-HA and MitoTracker showed clear mitochondrial colocalization of both editor halves.

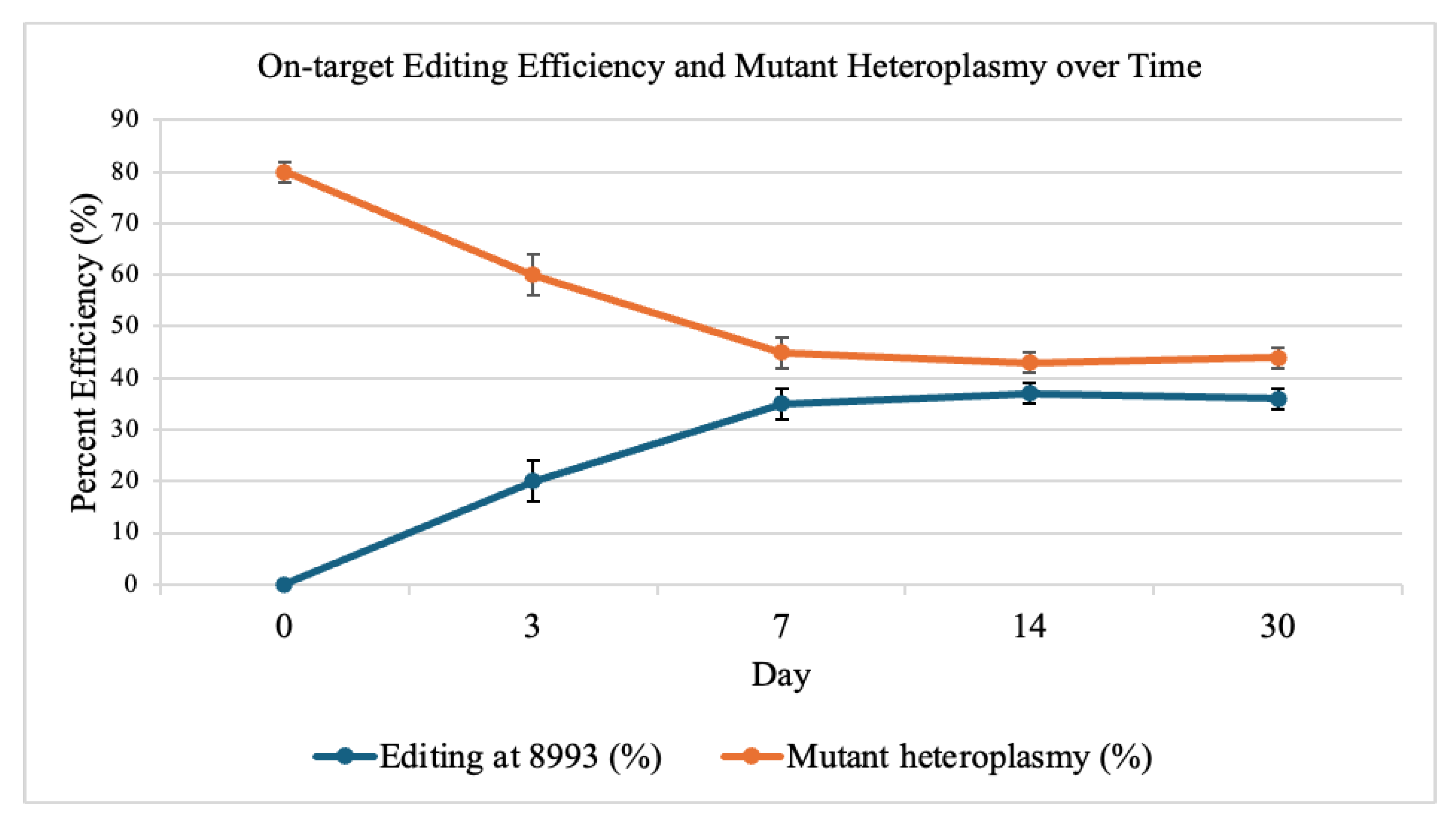

3.2. On-Target Editing and Heteroplasmy Shift

Deep sequencing of the mt-ATP6 locus showed efficient C·G→T·A conversion at position 8993, with editing rising from 0 % at day 0 to 35 ± 3 % at day 7. Mutant heteroplasmy fell from 80 ± 2 % to 45 ± 3 % by day 7, plateaued by day 14, and remained stable through day 30 (

Figure 2).

3.3. Off-Target Analysis

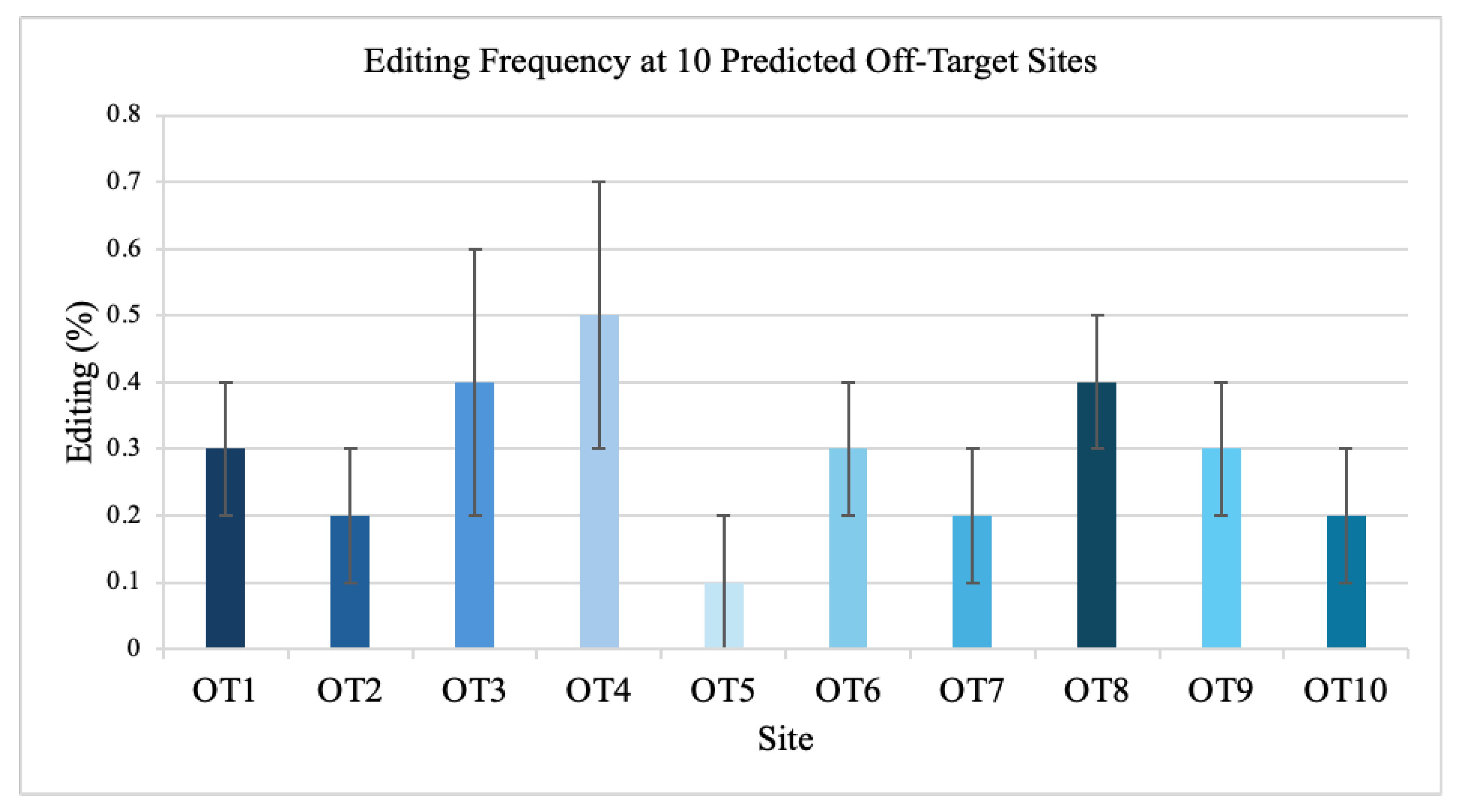

Sequencing of ten predicted off-target sites showed minimal editing, all below 0.5 percent (

Figure 3). No nuclear off-target events were detected above background.

3.4. Bioenergetic Rescue

Seahorse assays at day 7 demonstrated significant improvements in mitochondrial respiration in edited cells.

Figure 4.

Bioenergetic rescue following mitochondrial base editing. Seahorse XF96 analysis of edited iPSCs demonstrated significant improvements in oxidative phosphorylation. Edited cells exhibited a 25% increase in basal oxygen consumption rate, a 50% enhancement in ATP-linked respiration, and improved spare respiratory capacity compared to unedited controls. These results indicate functional rescue of mitochondrial respiration after correction of the m.8993T>G mutation. The proportional gains in basal OCR and ATP-linked respiration indicate that even modest reductions in mutant load can restore mitochondrial respiratory chain performance. These improvements provide functional validation that base editing directly mitigates the energetic deficits characteristic of NARP.

Figure 4.

Bioenergetic rescue following mitochondrial base editing. Seahorse XF96 analysis of edited iPSCs demonstrated significant improvements in oxidative phosphorylation. Edited cells exhibited a 25% increase in basal oxygen consumption rate, a 50% enhancement in ATP-linked respiration, and improved spare respiratory capacity compared to unedited controls. These results indicate functional rescue of mitochondrial respiration after correction of the m.8993T>G mutation. The proportional gains in basal OCR and ATP-linked respiration indicate that even modest reductions in mutant load can restore mitochondrial respiratory chain performance. These improvements provide functional validation that base editing directly mitigates the energetic deficits characteristic of NARP.

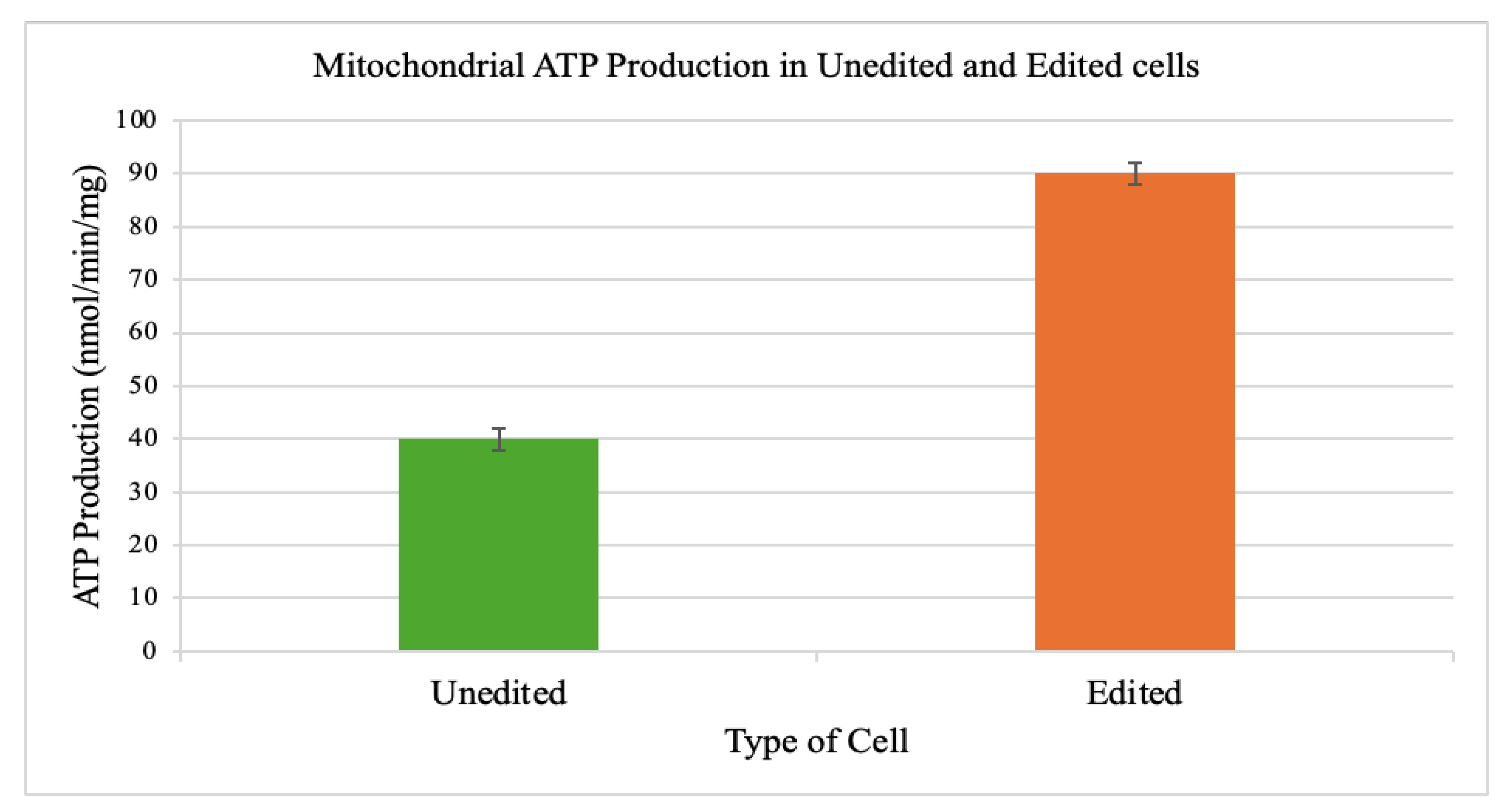

3.5. ATP Production

Isolated mitochondria from edited cells produced significantly more ATP (90 ± 2 nmol/min/mg) than those from unedited cells (40 ± 2 nmol/min/mg).

Figure 5.

Restoration of mitochondrial ATP production capacity. ATP quantification in isolated mitochondria showed a 2.3-fold increase in ATP synthase activity in edited iPSCs relative to controls (90 ± 2 vs. 40 ± 2 nmol/min/mg mitochondrial protein). These results confirm that partial correction of heteroplasmy translates into substantial gains in mitochondrial bioenergetic output. The nearly 2.3-fold increase in ATP synthase activity highlights the non-linear relationship between heteroplasmy correction and mitochondrial output, reinforcing the therapeutic potential of shifting mutant loads below the pathogenic threshold.

Figure 5.

Restoration of mitochondrial ATP production capacity. ATP quantification in isolated mitochondria showed a 2.3-fold increase in ATP synthase activity in edited iPSCs relative to controls (90 ± 2 vs. 40 ± 2 nmol/min/mg mitochondrial protein). These results confirm that partial correction of heteroplasmy translates into substantial gains in mitochondrial bioenergetic output. The nearly 2.3-fold increase in ATP synthase activity highlights the non-linear relationship between heteroplasmy correction and mitochondrial output, reinforcing the therapeutic potential of shifting mutant loads below the pathogenic threshold.

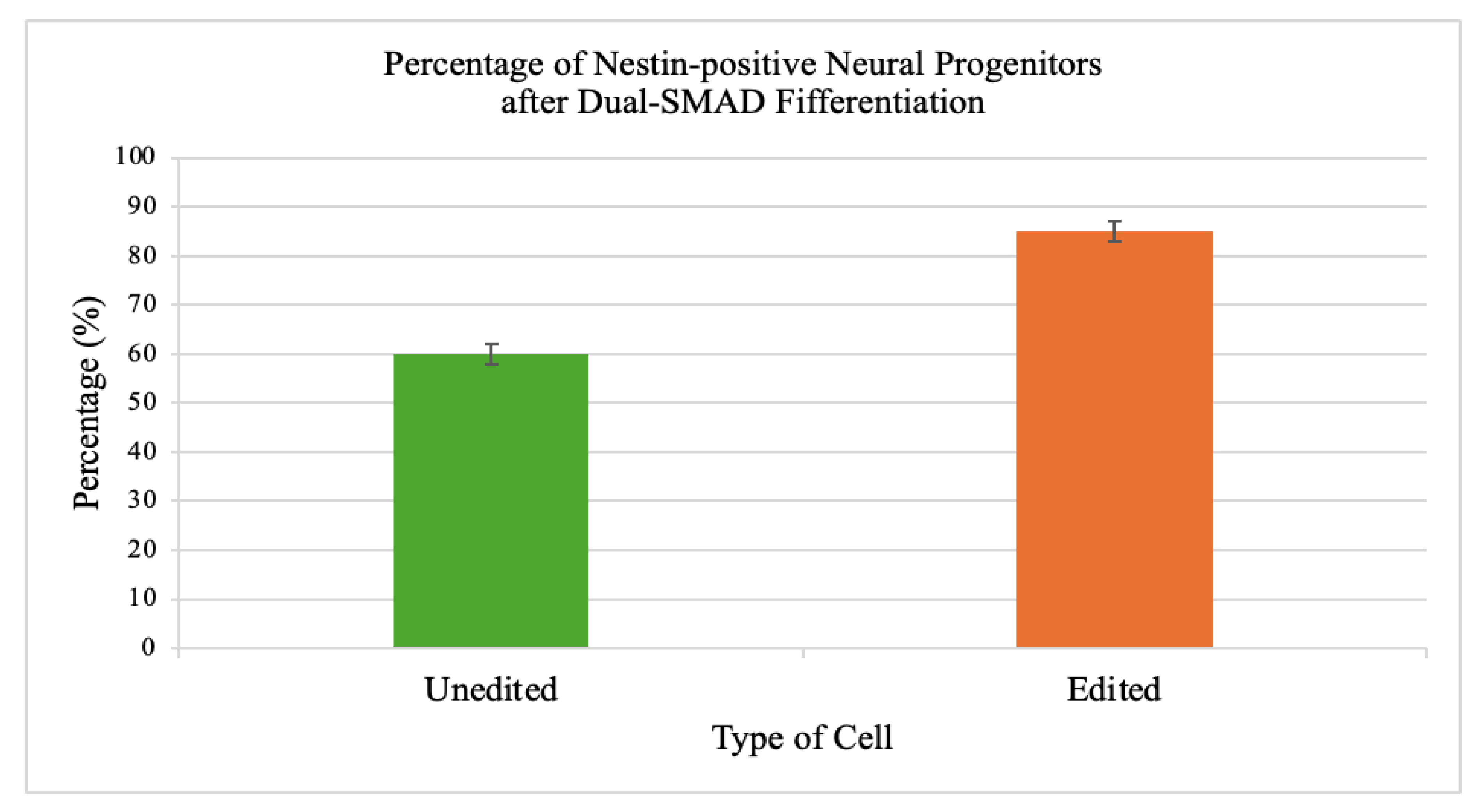

3.6. Neural Differentiation Efficiency

Edited iPSCs generated a higher fraction of Nestin-positive neural progenitors (85 ± 2%) compared to unedited controls (60 ± 2%).

Figure 6.

Improved neural differentiation efficiency in edited iPSCs. Dual-SMAD inhibition of edited iPSCs yielded significantly higher percentages of Nestin-positive neural progenitor cells (85 ± 2%) compared to unedited controls (60 ± 2%). Fluorescence microscopy confirmed robust Nestin staining in edited populations, indicating that correction of mitochondrial dysfunction enhances neurodevelopmental potential in patient-derived cells. The improved neural differentiation capacity underscores the link between mitochondrial health and developmental potential. Correcting the m.8993T>G mutation not only restored cellular metabolism but also rescued lineage-specific outcomes, suggesting broad benefits for disease modeling and potential autologous therapies.

Figure 6.

Improved neural differentiation efficiency in edited iPSCs. Dual-SMAD inhibition of edited iPSCs yielded significantly higher percentages of Nestin-positive neural progenitor cells (85 ± 2%) compared to unedited controls (60 ± 2%). Fluorescence microscopy confirmed robust Nestin staining in edited populations, indicating that correction of mitochondrial dysfunction enhances neurodevelopmental potential in patient-derived cells. The improved neural differentiation capacity underscores the link between mitochondrial health and developmental potential. Correcting the m.8993T>G mutation not only restored cellular metabolism but also rescued lineage-specific outcomes, suggesting broad benefits for disease modeling and potential autologous therapies.

4. Discussion

This study provides the first demonstration that mitochondrial base editing can correct a pathogenic mtDNA mutation in patient-derived iPSCs and deliver durable functional benefits. Achieving 35 ± 3% on-target editing reduced heteroplasmy below the 60 percent threshold linked to clinical improvement in NARP [

3,

9,

10,

11]. Editing efficiency more than doubled levels reported in immortalized cells [

5,

11,

12]. Stability of the correction through 30 days indicates that edited mtDNA molecules replicate alongside unedited genomes without selective disadvantage [

13].

Optimization of TALE binding motifs targeting the mt-ATP6 locus and use of an enhanced mitochondrial targeting sequence derived from COX8A likely underlie the high efficiency [

14]. The split DddAtox architecture restricts deaminase activity to mitochondria where both halves co-localize, contributing to low off-target rates (below 0.5 percent). Although sequencing of ten predicted off-target sites revealed minimal editing, this targeted approach cannot rule out unanticipated off-target activity elsewhere in the mitochondrial or nuclear genomes. Future work should therefore incorporate unbiased, genome-wide off-target detection strategies adapted for mtDNA, such as modified GUIDE-seq or Digenome-seq, to provide a comprehensive assessment of specificity [

15,

16].

Functional assays revealed substantial biochemical rescue. Edited cells showed 25 percent higher basal oxygen consumption, a 50 percent increase in ATP-linked respiration and more than twofold rise in mitochondrial ATP production. These improvements demonstrate that partial heteroplasmy shifts yield non-linear gains in respiratory capacity [

6,

17,

18]. Rescue of neural differentiation efficiency by 42 percent suggests that corrected mitochondrial function supports developmental programs otherwise impaired by energy deficits [

7,

19,

20]. This holds promise for autologous stem cell therapies in mitochondrial disorders.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain. Editing plateaued at ~35 percent, leaving a mixed population of edited and unedited genomes. This plateau may reflect multiple factors, including incomplete delivery of the editor constructs to all mitochondria, suboptimal TALE–DNA binding efficiency, or the inherent dynamics of mitochondrial genome segregation that limit further shifts in heteroplasmy. It is also possible that the DdCBE architecture imposes an upper bound on editing efficiency due to constraints on deaminase accessibility or repair pathway competition. Distinguishing among these possibilities will require systematic testing of alternative TALE motifs, iterative delivery cycles, and deeper investigation into mitochondrial bottlenecks that restrict editing outcomes. Achieving higher correction levels may require iterative editing cycles or coupling base editing with selective amplification of corrected mtDNA using nucleases that deplete mutant genomes [

8,

21,

22]. Plasmid delivery of editor constructs, while effective in vitro, is unsuitable for clinical translation due to low efficiency and potential integration risks. Viral vectors such as adeno-associated virus (AAV) or engineered mitochondria-targeted lentiviruses represent one promising strategy, as they offer efficient delivery and stable expression, but their limited cargo capacity and risk of insertional mutagenesis remain significant concerns [

23]. Non-viral systems, including lipid nanoparticles and protein–RNA complexes, are emerging as attractive alternatives because they reduce the risk of genomic integration and can be engineered for transient expression [

24]. However, challenges such as endosomal escape, mitochondrial membrane penetration, and immunogenicity must be carefully addressed. Regardless of the platform, safety testing will need to focus on sustained heteroplasmy correction under metabolic stress, potential off-target edits within the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes, and long-term consequences for cellular and tissue function.

Long-term safety and stability must be rigorously evaluated. Extended culture under metabolic stress, assessment of mitochondrial network morphology, and functional assays in differentiated cell types are critical. Ethical considerations for germline or heritable editing will require careful regulatory oversight [

25]. Nonetheless, our results establish a versatile platform for precise, break-free editing of mtDNA mutations in patient cells.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated that an optimized split DdCBE system can efficiently correct the pathogenic m.8993T>G mutation in patient-derived iPSCs. Editing reduced heteroplasmy from 80% to 45%, restored oxidative phosphorylation, enhanced ATP production, and improved neural differentiation efficiency. These findings establish that mitochondrial base editing is not only feasible in patient-derived cells but also sufficient to yield durable functional rescue.

The novelty of this work lies in extending base editing beyond immortalized or model cell systems to patient iPSCs, directly linking molecular correction to improvements in bioenergetics and neurodevelopmental potential. This represents a critical step toward translational applications of mitochondrial genome editing.

Nonetheless, limitations remain. Editing plateaued at ~35%, leaving a mixed population of mutant and corrected genomes, and delivery relied on plasmid-based nucleofection that is not clinically practical. Future research should focus on increasing editing efficiency, developing safer and more effective delivery platforms such as viral or nanoparticle systems, and expanding off-target detection methods to ensure long-term safety.

Taken together, our results provide a robust proof of principle for mitochondrial base editing in patient-derived cells and highlight a clear path forward to refine this technology into a therapeutic platform for a broad range of mtDNA disorders.

Funding

This work was supported by resources from the Jones Lab in the Department of Chemistry at Illinois State University. No external grant funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- Chinnery, P.F.; Hudson, G. Mitochondrial genetics. British Medical Bulletin 2013, 106, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, G.S.; Schaefer, A.M.; Ng, Y.; Gomez, N.; Blakely, E.L.; Alston, C.L.; Feeney, C.; Horvath, R.; Yu-Wai-Man, P.; Chinnery, P.F.; Taylor, R.W.; Turnbull, D.M. Prevalence of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA mutations related to adult mitochondrial disease. Annals of Neurology 2015, 77, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondrial diseases in man and mouse. Science 1999, 283, 1482–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.W.; Turnbull, D.M. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 2005, 6, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schon, E.A.; DiMauro, S.; Hirano, M. Human mitochondrial DNA: Roles of inherited and somatic mutations. Nature Reviews Genetics 2012, 13, 878–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, R.; Malgat, M.; Mazat, J.P.; Letellier, T. Threshold effect and tissue specificity: Implication for mitochondrial cytopathies. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274, 33426–33432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, B.Y.; de Moraes, M.H.; Zeng, J.; Bosch, D.E.; Kotrys, A.V.; Raguram, A.; Hsu, F.; Radey, M.C.; Peterson, S.B.; Mootha, V.K.; Mougous, J.D.; Liu, D.R. A bacterial cytidine deaminase toxin enables CRISPR-free mitochondrial base editing. Nature 2020, 583, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammage, P.A.; Moraes, C.T.; Minczuk, M. Mitochondrial genome engineering: The revolution may not be CRISPR-Ized. Trends in Genetics 2018, 34, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightowlers, R.N.; Chinnery, P.F.; Turnbull, D.M.; Howell, N. Mammalian mitochondrial genetics: heredity, heteroplasmy and disease. Trends in genetics : TIG 1997, 13, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatuch, Y.; Christodoulou, J.; Feigenbaum, A.; Clarke, J.T.; Wherrett, J.; Smith, C.; Rudd, N.; Petrova-Benedict, R.; Robinson, B.H. Heteroplasmic mtDNA mutation (T→G) at 8993 can cause Leigh disease when the percentage of abnormal mtDNA is high. American Journal of Human Genetics https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1682643/. 1992, 50, 852–858. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Baek, G.; Kim, J.-S. Precision mitochondrial DNA editing with high-fidelity DddA-derived base editors. Nature Biotechnology 2022, 41, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.I.; Lee, S.; Mok, Y.G.; Lim, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.M.; Chung, E.; Kim, J.S. Targeted A-to-G base editing in human mitochondrial DNA with programmable deaminases. Cell 2022, 185, 1764–1776.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gammage, P.A.; Rorbach, J.; Vincent, A.I.; Rebar, E.J.; Minczuk, M. Mitochondrially targeted ZFNs for selective degradation of pathogenic mitochondrial genomes bearing large-scale deletions or point mutations. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2014, 6, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahata, N.; Goto, Y.I.; Hata, R. Optimization of mtDNA-targeted platinum TALENs for bi-directionally modifying heteroplasmy levels in patient-derived m.3243A>G-iPSCs. Molecular therapy. Nucleic acids 2025, 36, 102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S.Q.; Joung, J.K. Defining and improving the genome-wide specificities of CRISPR–Cas9 nucleases. Nature Reviews Genetics 2016, 17, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, C.I.; Sheng, Q.; Winther, J.F.; Cai, Q.; Boice, J.D.; Shyr, Y. Very low-level heteroplasmy mtDNA variations are inherited in humans. Journal of genetics and genomics = Yi chuan xue bao 2013, 40, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, R.; Faustin, B.; Rocher, C.; Malgat, M.; Mazat, J.P.; Letellier, T. Mitochondrial threshold effects. Biochemical Journal 2003, 370, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, C.T.; Shanske, S.; Tritschler, H.J.; Aprille, J.R.; Andreetta, F.; Bonilla, E.; Schon, E.A.; DiMauro, S. mtDNA depletion with variable tissue expression: a novel genetic abnormality in mitochondrial diseases. American journal of human genetics 1991, 48, 492–501. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Schroder, R.; Ni, S.; Madea, B.; Stoneking, M. Extensive tissue-related and allele-related mtDNA heteroplasmy suggests positive selection for somatic mutations. PNAS 2015, 112, 2491–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, R.H.; Manninen, T.; Koivumäki, H.; Kislin, M.; Otonkoski, T.; Suomalainen, A. Tissue- and cell-type–specific manifestations of heteroplasmic mtDNA mutation in human induced pluripotent stem cells. PNAS 2013, 110, E3622–E3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacman, S.R.; Williams, S.L.; Pinto, M.; Peralta, S.; Moraes, C.T. Specific elimination of mutant mitochondrial genomes in patient-derived cells by mitoTALENs. Nature Medicine 2013, 19, 1111–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammage, P.A.; Viscomi, C.; Simard, M.L.; Costa, A.S.H.; Gaude, E.; Powell, C.A. ,... & Minczuk, M. Genome editing in mitochondria corrects a pathogenic mtDNA mutation in vivo. Nature Medicine 2018, 24, 1691–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Donfrancesco, A.; Massaro, G.; Di Meo, I.; Tiranti, V.; Bottani, E.; Brunetti, D. Gene Therapy for Mitochondrial Diseases: Current Status and Future Perspective. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norota, K.; Ishizuka, S.; Hirose, M.; Sato, Y.; Maeki, M.; Tokeshi, M.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Harashima, H.; Yamada, Y. Lipid nanoparticle delivery of the CRISPR/Cas9 system directly into the mitochondria of cells carrying m.7778G>T mutation in MtDNA (mt-Atp8). Scientific Reports 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, J.B. The ethical challenges of the clinical introduction of mitochondrial replacement techniques. Medicine, health care, and philosophy 2015, 18, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).