Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

01 October 2025

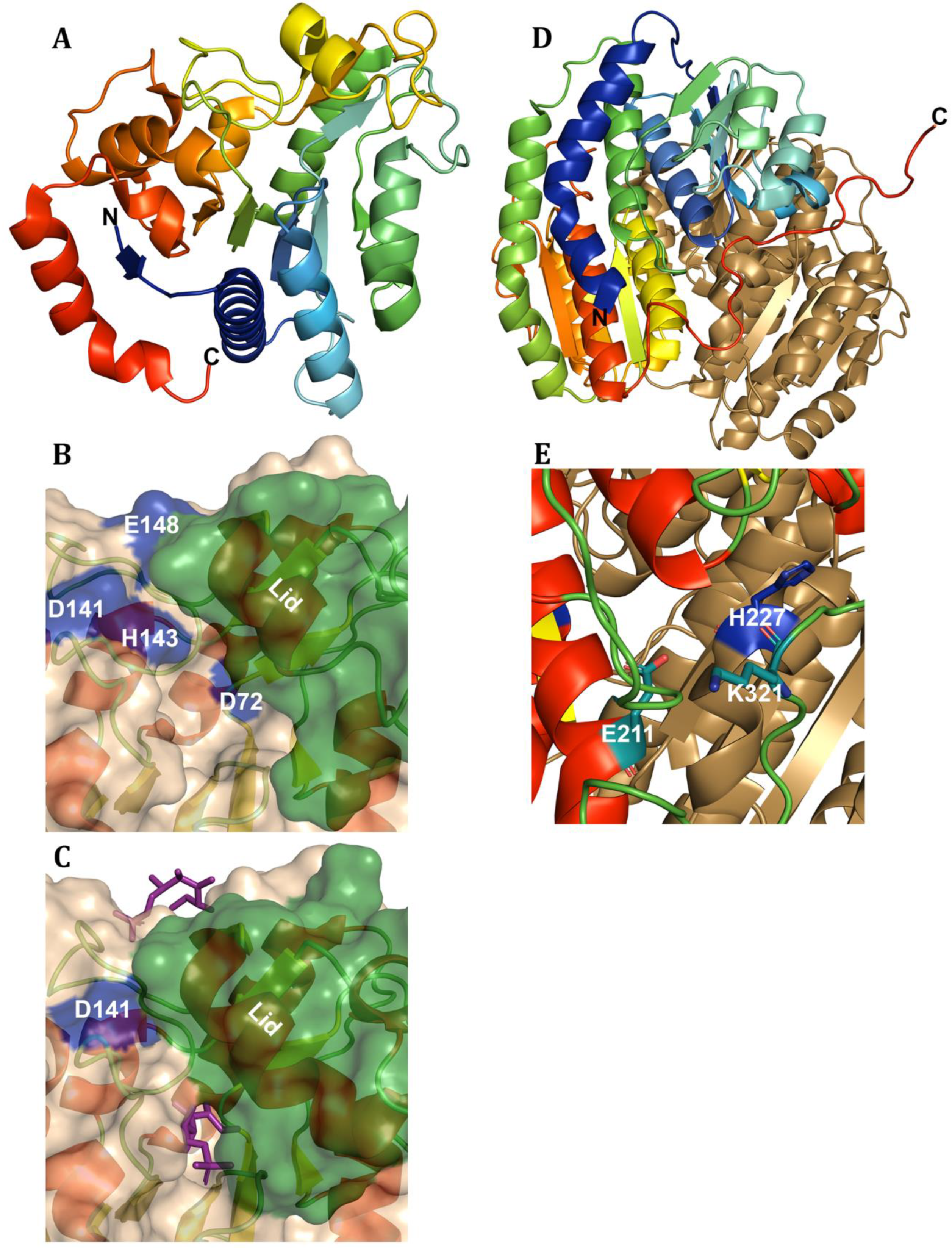

You are already at the latest version

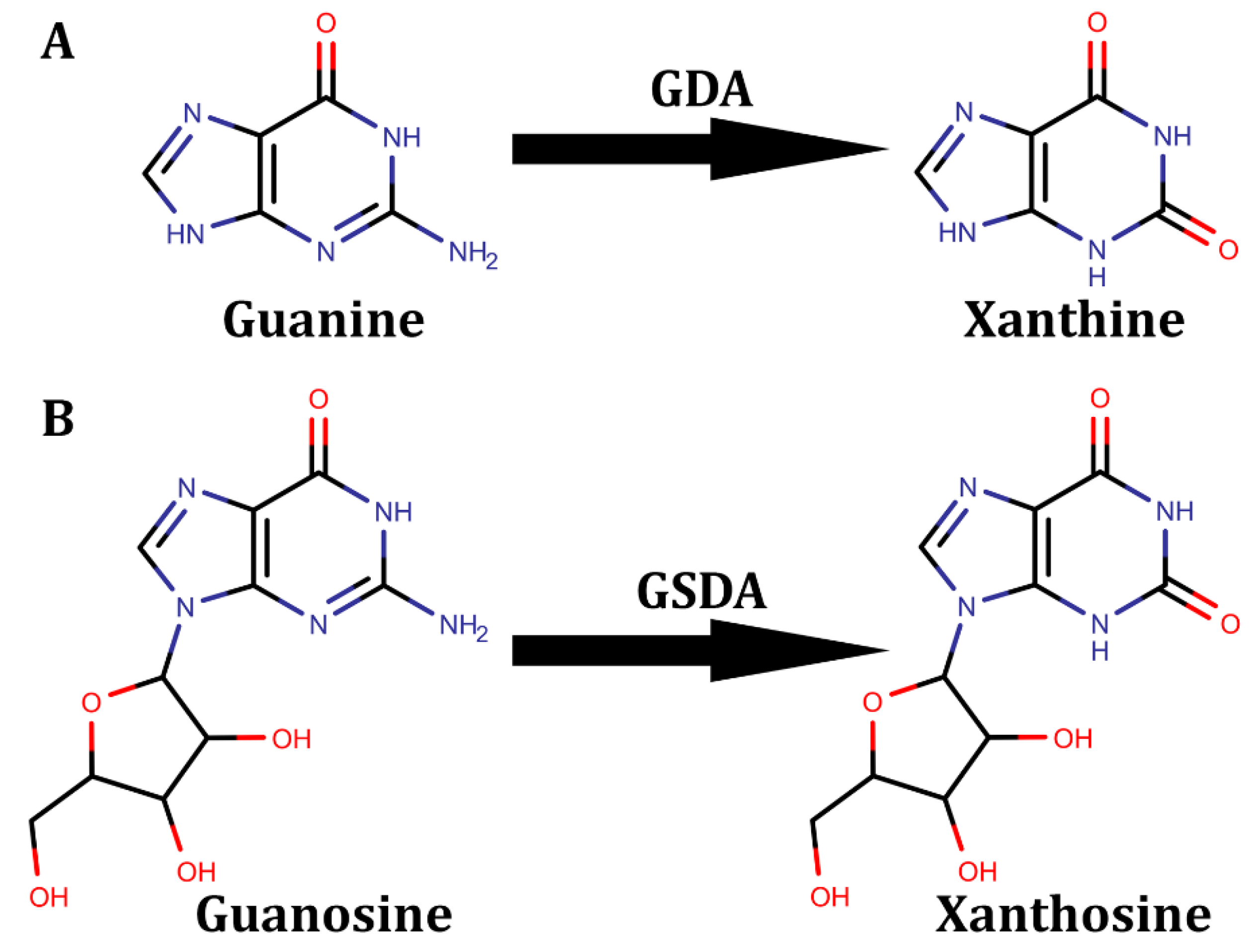

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

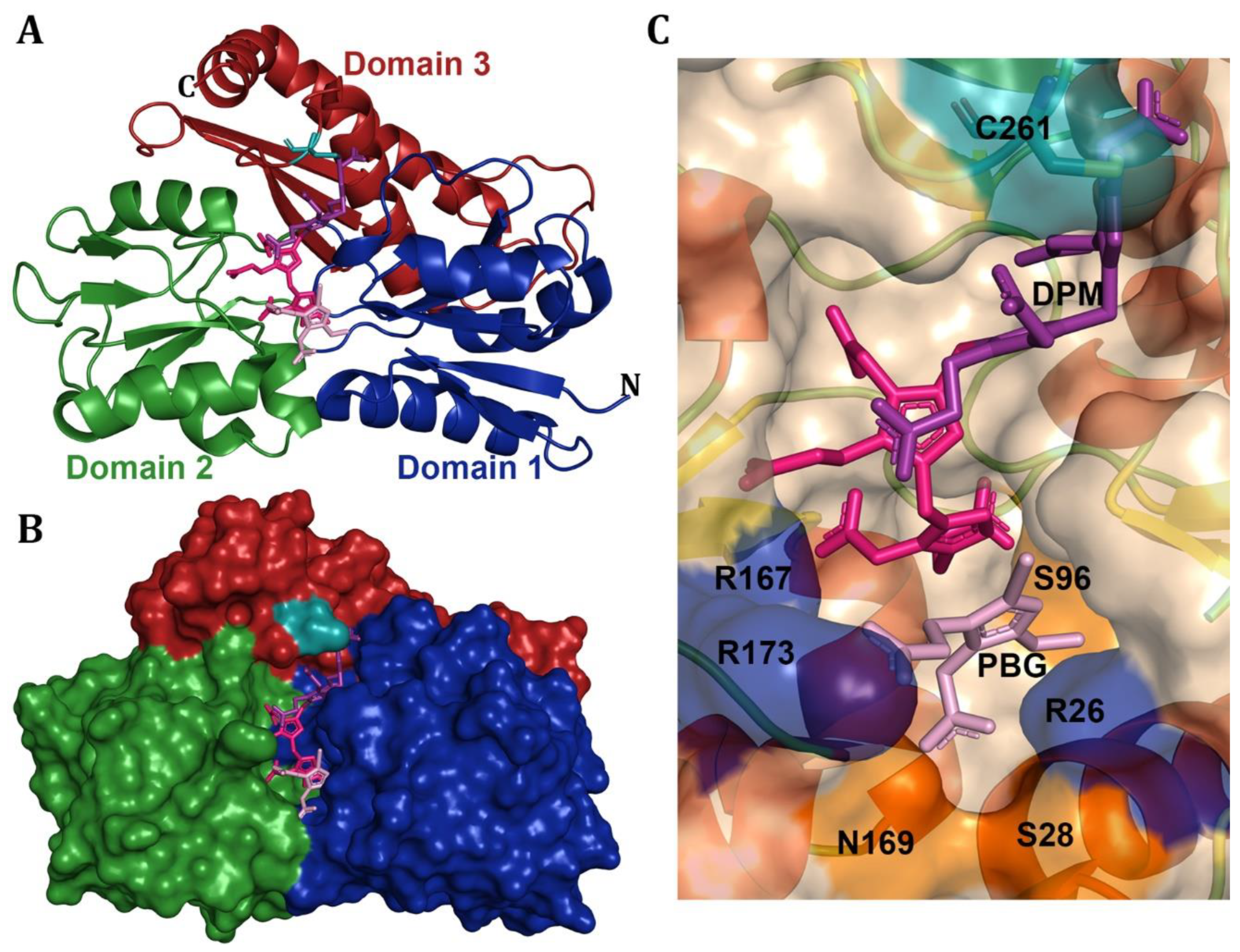

2. Tetrapyrroles Biosynthesis Pathway Deaminases

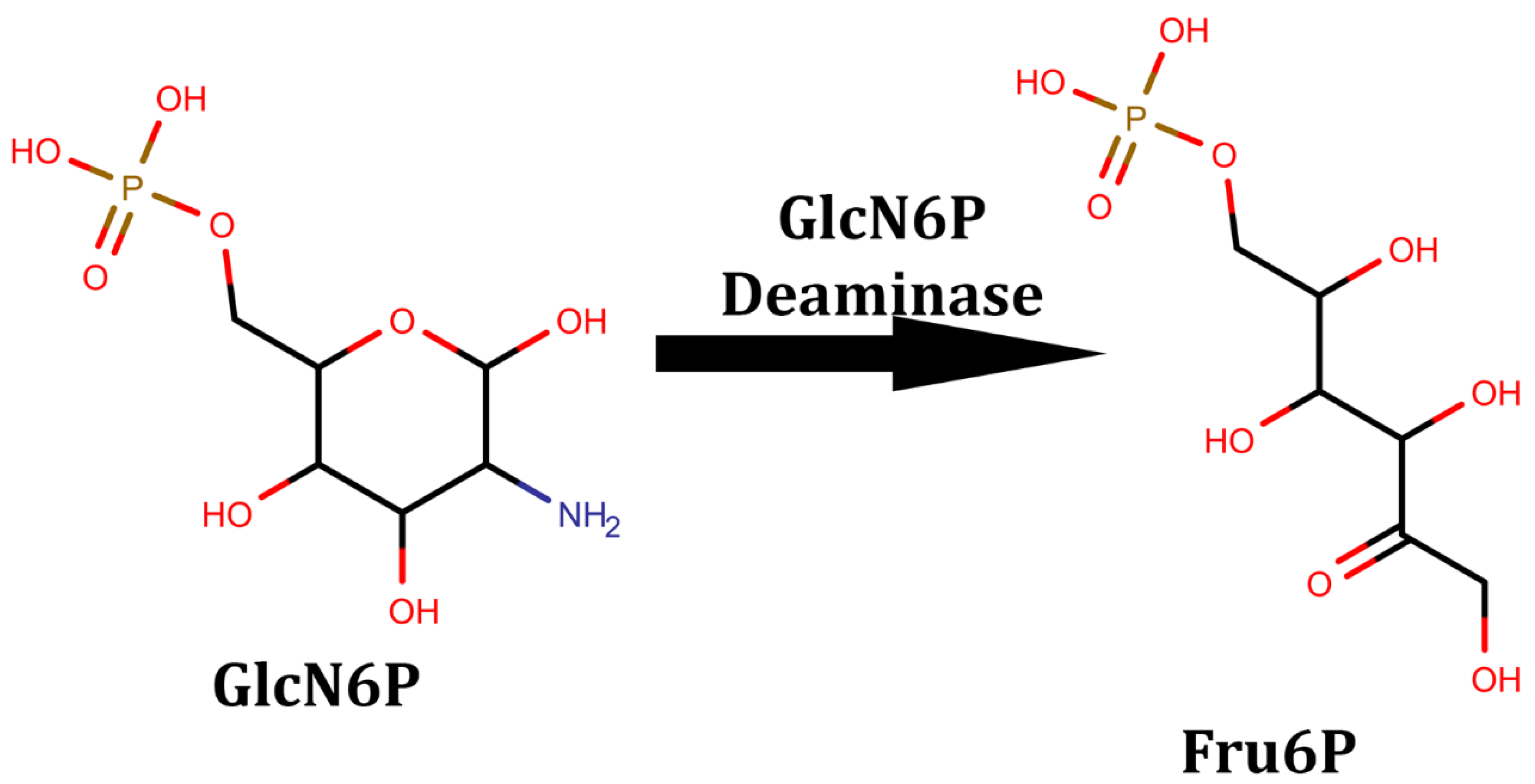

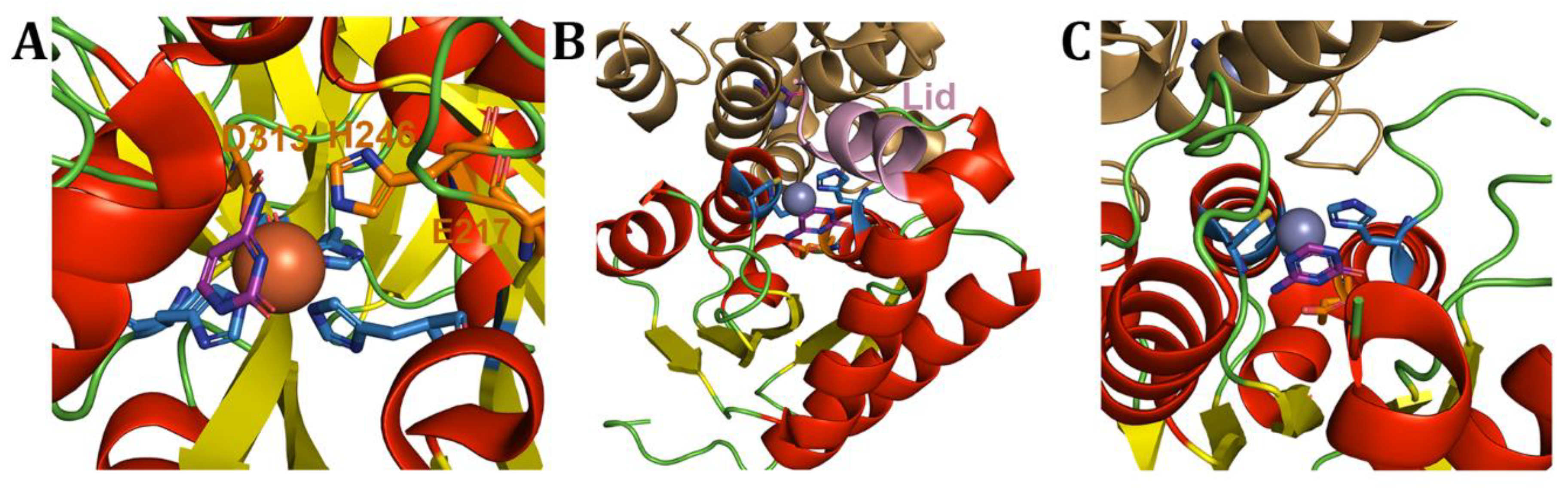

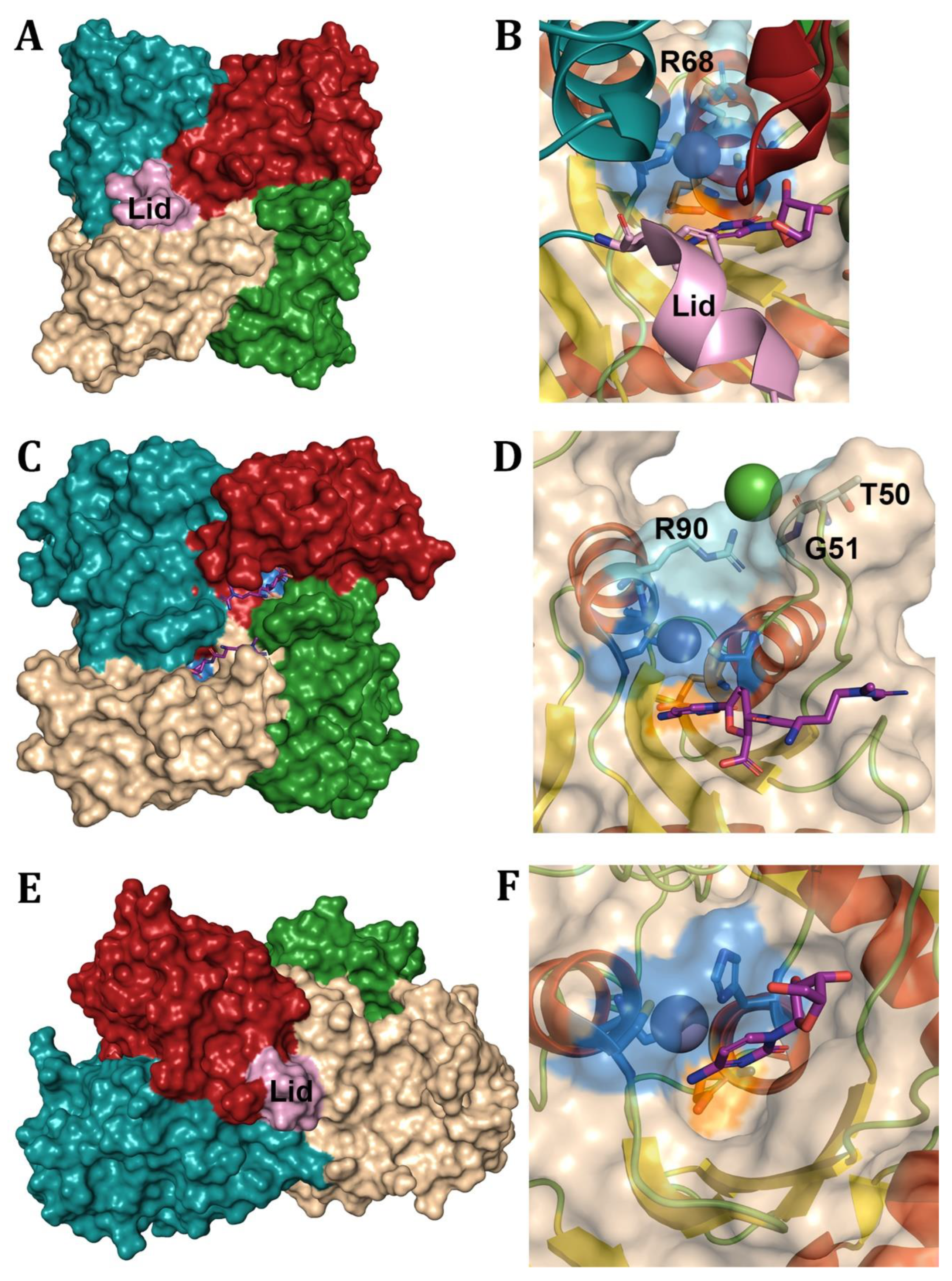

3. Amino Sugar Deaminases

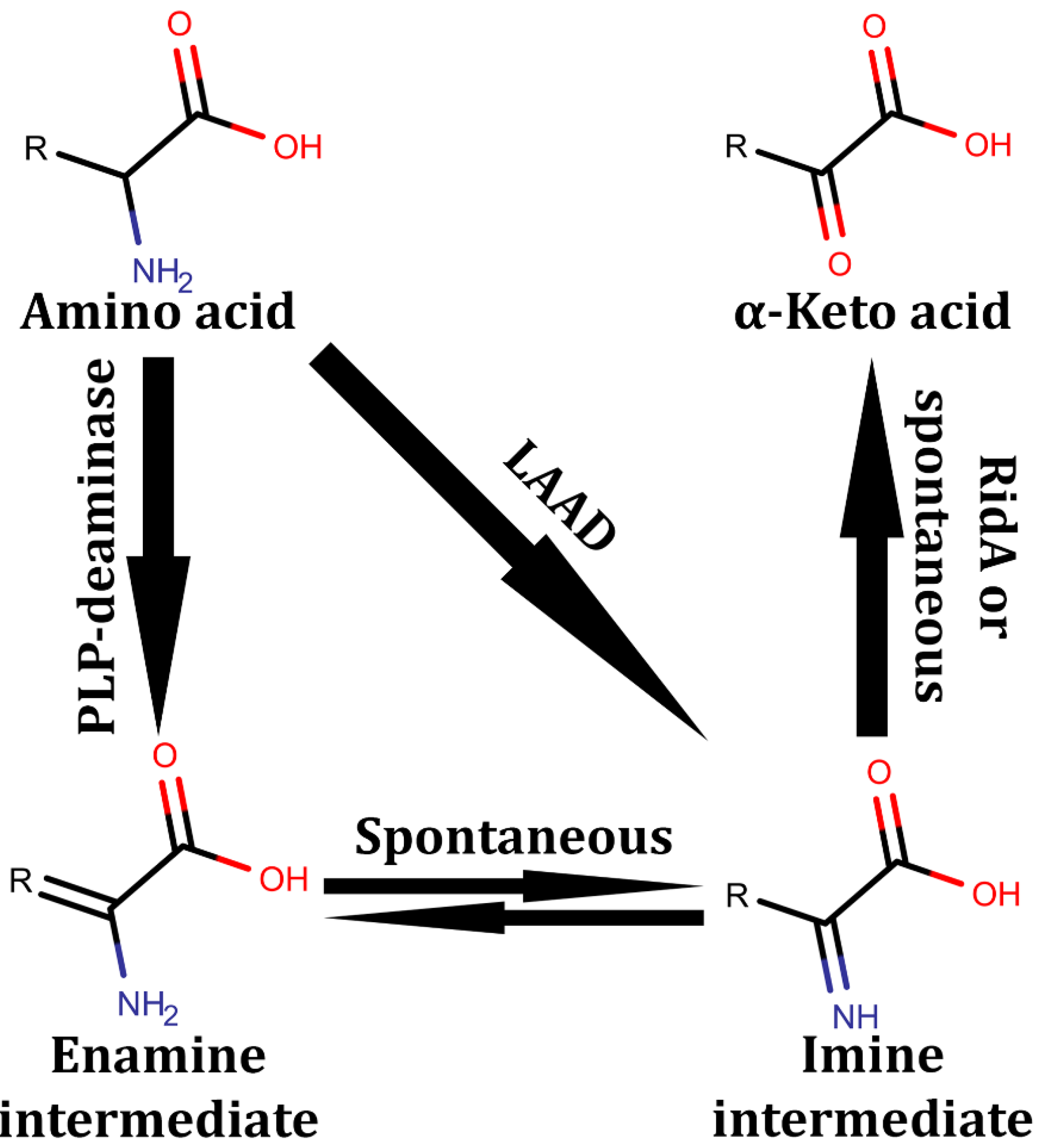

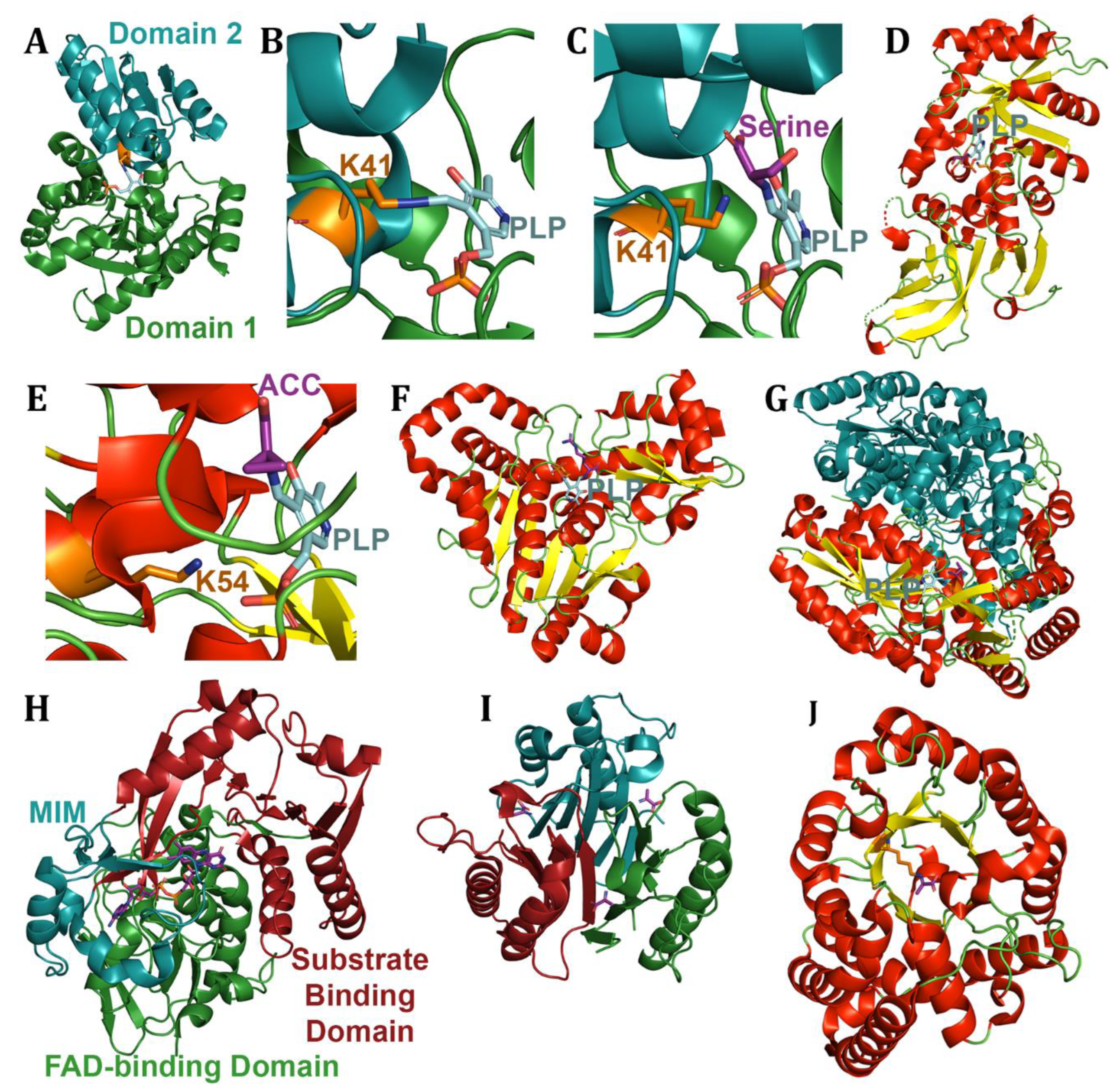

4. Amino Acid Derivative Deaminases

5. Guanine Derivative Deaminases

6. Adenine Deaminases and Derivatives

6.1. Free adenine-Derived Nucleo -Base/-Side Deaminases

6.2. Adenosine tRNA Deaminases

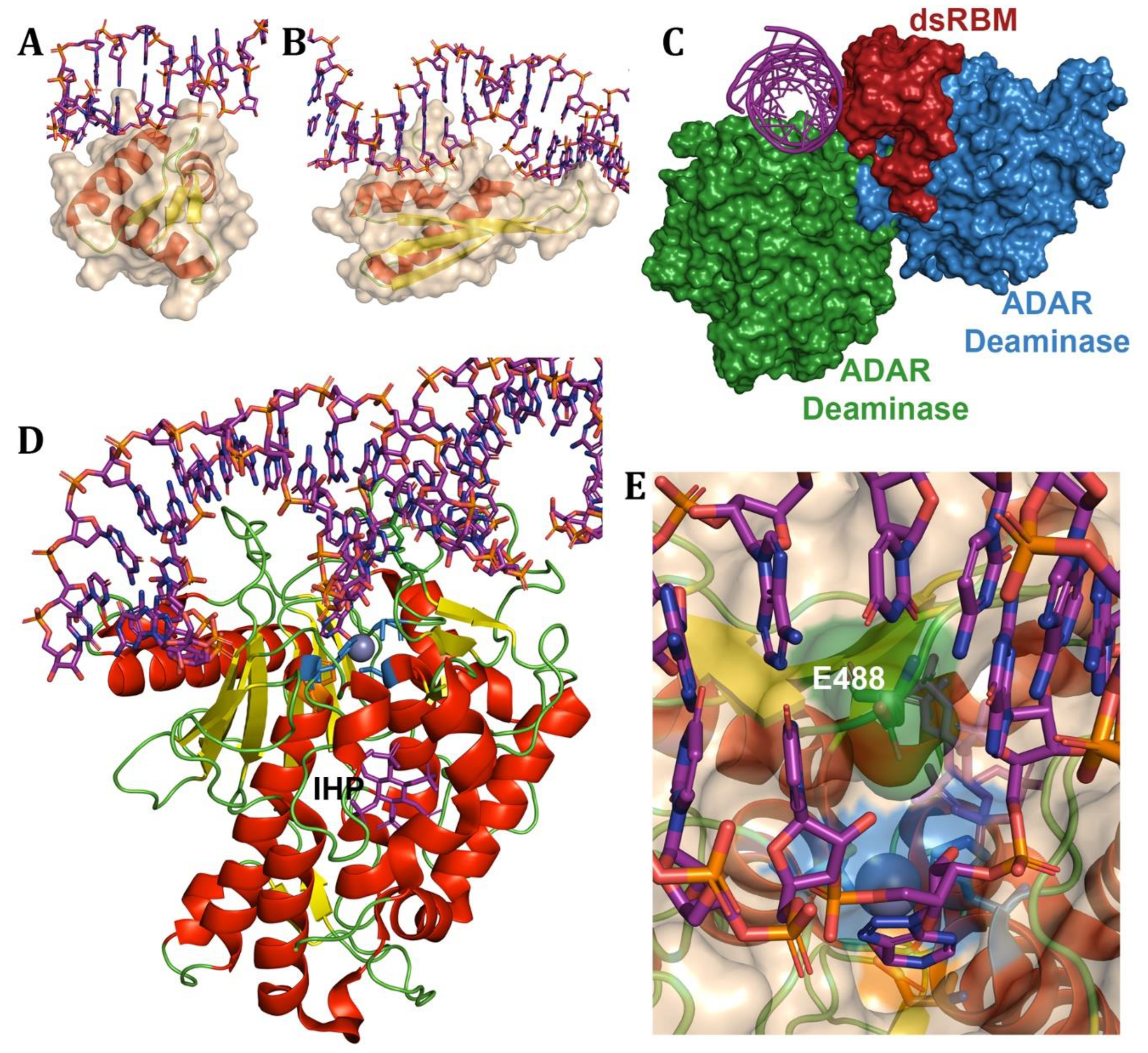

6.3. Adenosine dsRNA Deaminases

7. Cytosine Deaminases and Derivatives

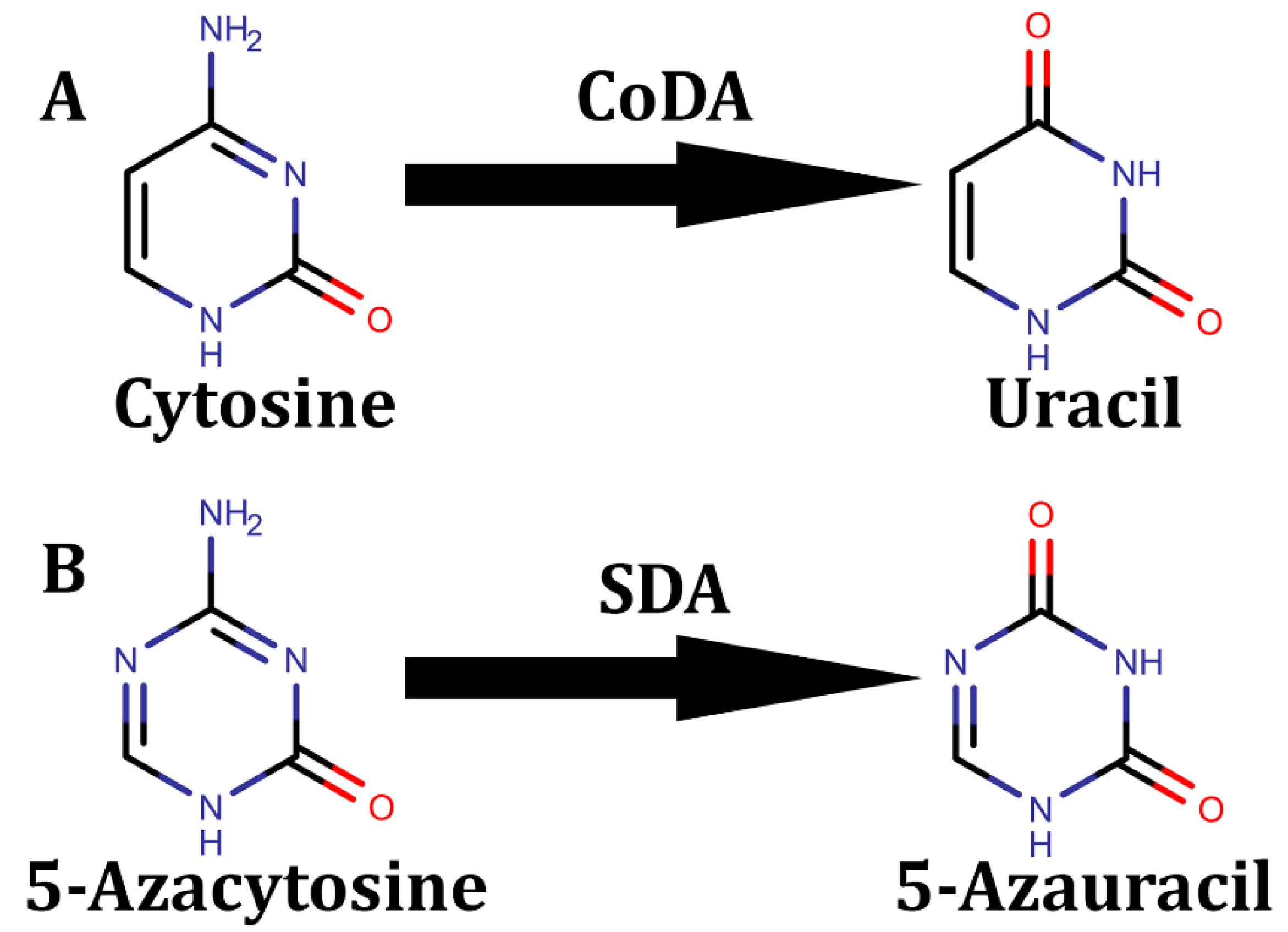

7.1. Free Cytosine-Derived Nucleobase Deaminases

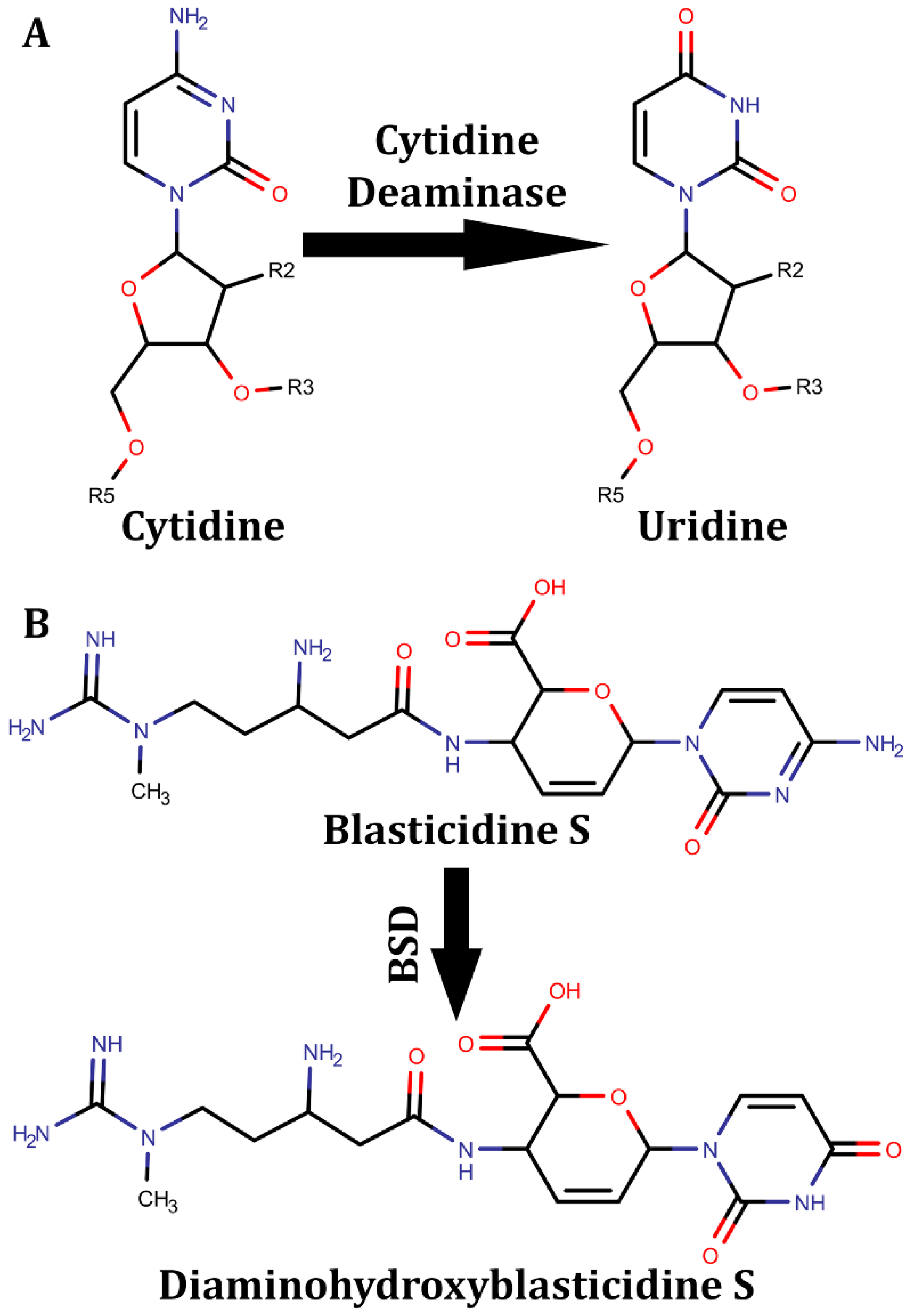

7.2. Free Cytosine-Derived Nucleoside Deaminases

7.3. Free Cytosine-Derived Nucleotide Deaminases

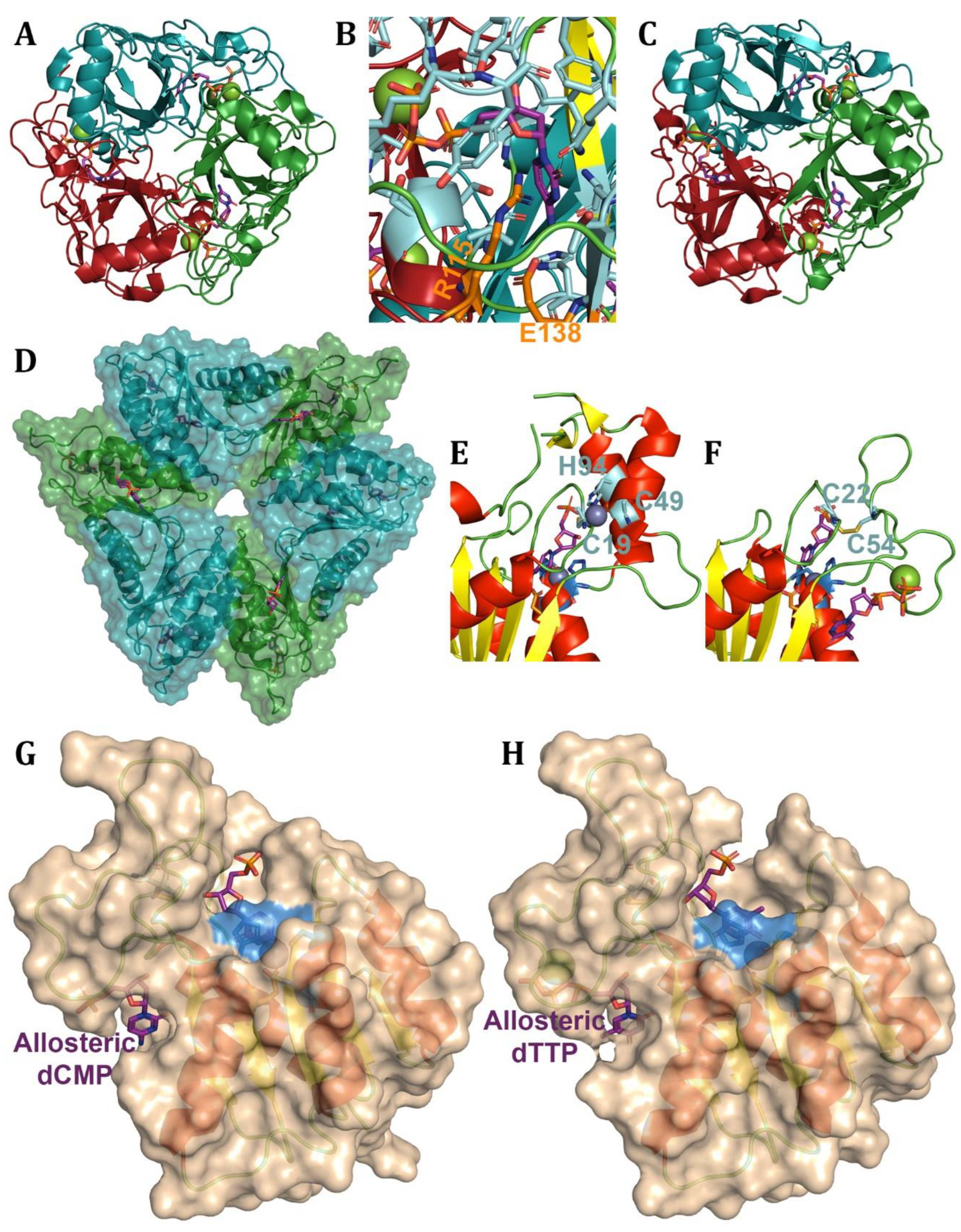

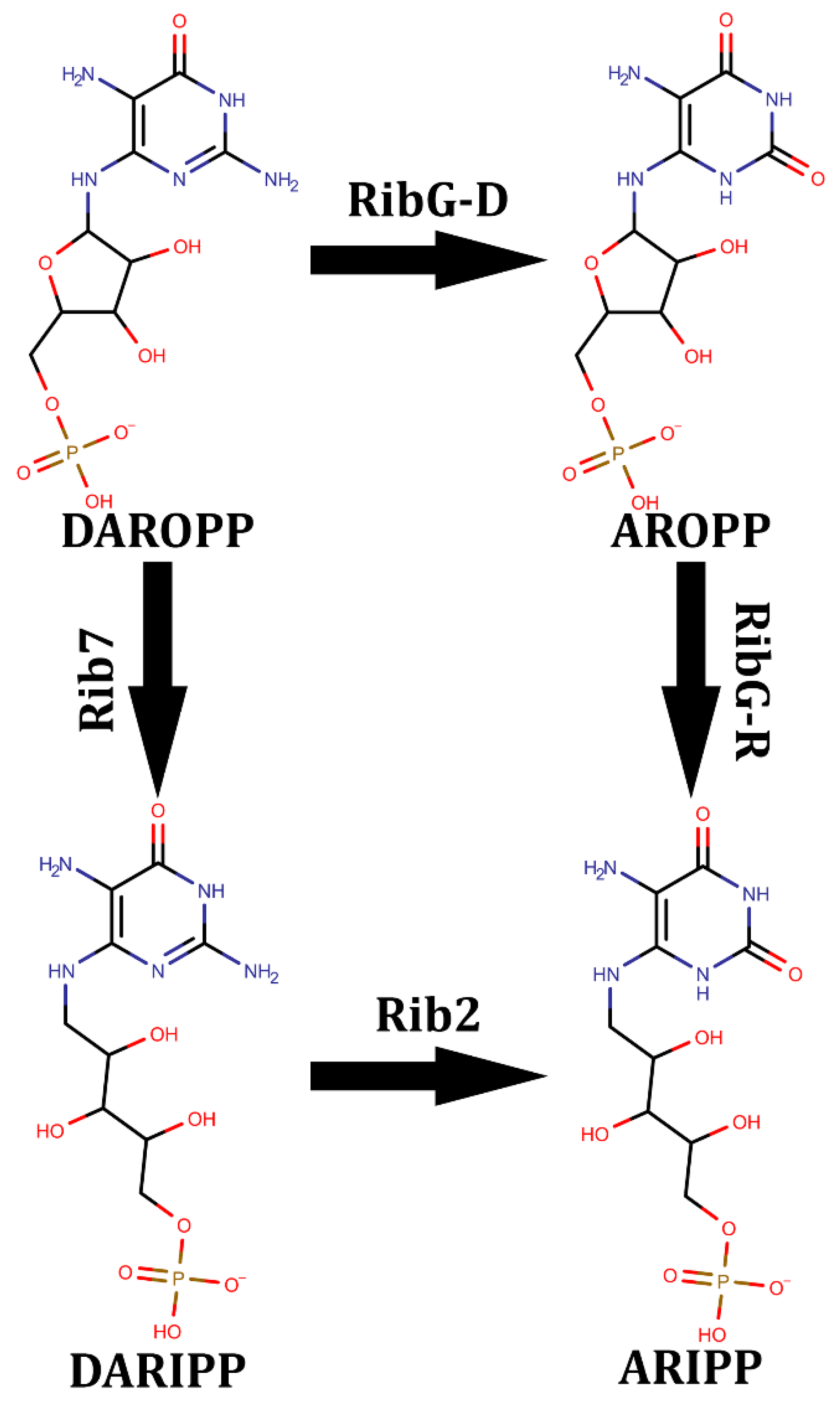

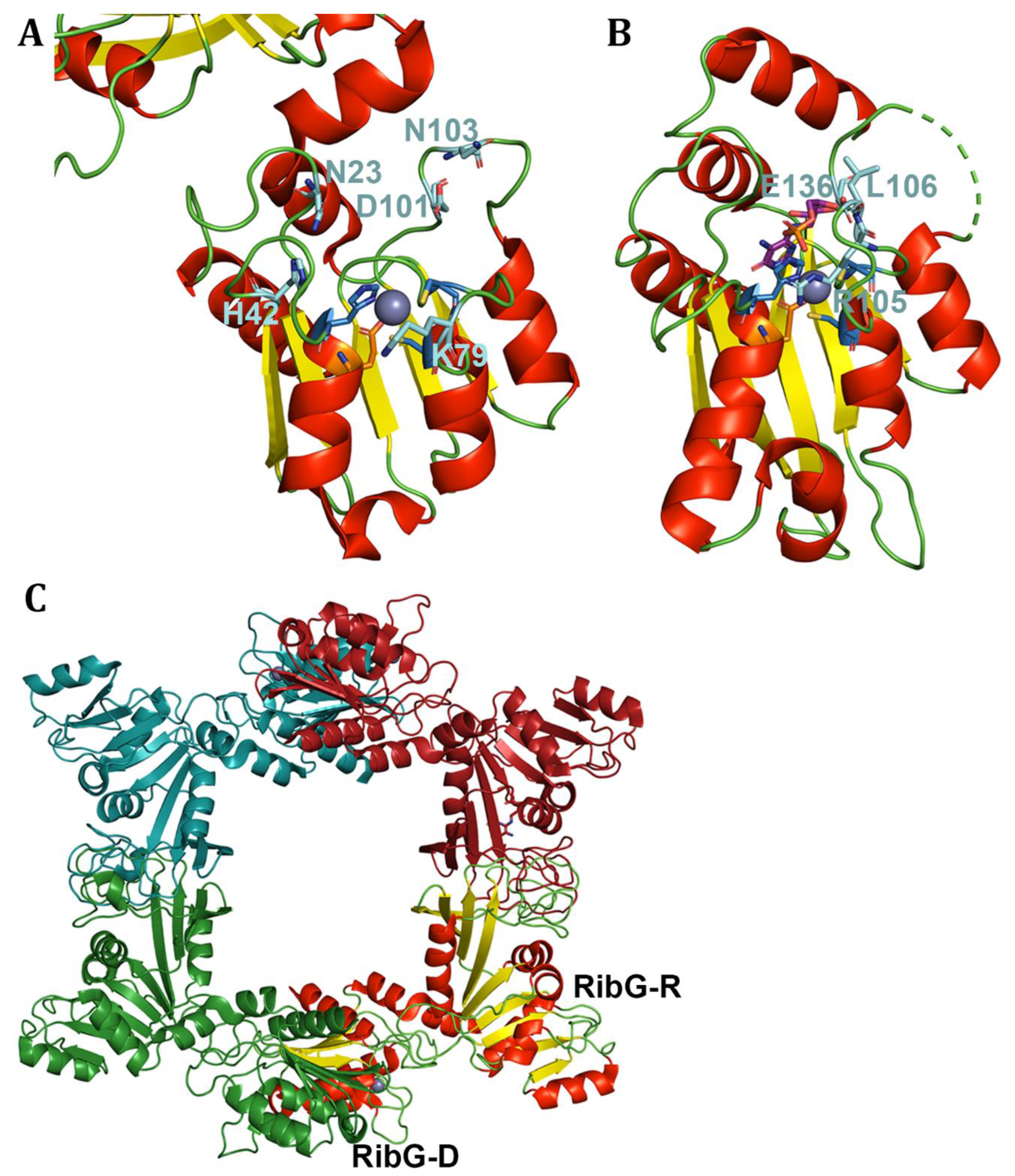

7.4. Free Cytosine-Derived Vitamin B2 Pathway Deaminases

7.5. Cytidine RNA Deaminases

7.6. Cytidine DNA Interbacterial Toxin Deaminases

7.7. AID/APOBEC Family Deaminases

8. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A1CF | APOBEC1 complementation factor |

| AAAD | Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase |

| ABE | Adenosine base editor |

| ACC | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid |

| ACCD | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid deaminase |

| ADA | Adenosine deaminases |

| ADAR | dsRNA-specific adenosine deaminases |

| ADATs | Adenosine deaminases of tRNA (Eukaryotic) |

| ADEase | Adenine deaminases |

| AFLDA | Aminofutalosine deaminase |

| AID | Activation-induced cytidine deaminase |

| APOBEC | Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing catalytic polypeptide-like |

| ARIPP | 5-amino-6-(D-ribitylamino-2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione 5’-phosphate |

| AROPP | 5-amino-6-ribosylamino-2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione 5’-phosphate |

| BSD | Blasticidin S deaminase |

| CaMV | Cauliflower mosaic virus |

| CBE | Cytidine base editor |

| CBF-β | Core binding factor-β |

| CD | Catalytic domain |

| CDA | Cytidine deaminase |

| CDAT8 | Cytidine deaminase of tRNA 8 |

| CoDA | Cytosine deaminase |

| CSR | Class switch recombination |

| dAMPD | Deoxyadenosine monophosphate deaminase |

| DARIPP | 2,5-diamino-6-ribitylamino-4(3H)-pyrimidinone 5’-phosphate |

| DAROPP | 2,5-diamino-6-ribosylamino-4-(3H)-pyrimidinone 5’-phosphate |

| DCD:DUT | Bifunctional deaminase/diphosphatase |

| D-CDA | Dimeric cytidine deaminase |

| dCTPD | deoxycytidine triphosphate deaminase |

| DddA | dsDNA deaminase toxin A |

| DPM | Dipyrromethane |

| dsRBM | dsRNA-binding motifs |

| FAD | Flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| FAMIN | Fatty acid metabolism-immunity nexus |

| FMN | Flavin mononucleotide |

| GDA | Guanine deaminases |

| GlcN6P | Glucosamine-6-phosphate |

| GlcNAc6P | N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-6-phosphate |

| GSDA | Guanosine deaminase |

| HMBS | Hydroxymethylbilane synthase |

| HPC | 1-pyrroline-4-hydroxy-2-carboxylate |

| IHP | Inositol hexakisphosphate |

| LAAD | L-amino acid deaminase |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| MAPDA | N6-methyl-adenosine monophosphate deaminase |

| PBGD | Porphobilinogen deaminase |

| PLP | Pyridoxal 5’-phosphate |

| PPR | Pentatricopeptide repeat |

| RBM47 | RNA-binding protein 47 |

| RHS | rearrangement hotspot |

| RidA | Reactive intermediate deaminase A |

| SHM | Somatic hypermutation |

| SsdA | ssDNA deaminase toxin A |

| TadA | tRNA adenosine deaminases (prokaryotic and plant chloroplast) |

| T-CDA | Tetrameric cytidine deaminase |

| TD | Threonine deaminase |

| Vif | Viral infectivity factor |

References

- Wilson, D.K., F.B. Rudolph, and F.A. Quiocho, Atomic structure of adenosine deaminase complexed with a transition-state analog: understanding catalysis and immunodeficiency mutations. Science, 1991. 252(5010): p. 1278-84.

- Ose, T., et al., Reaction intermediate structures of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase: insight into PLP-dependent cyclopropane ring-opening reaction. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(42): p. 41069-76.

- Slater, P.G., et al., Characterization of Xenopus laevis guanine deaminase reveals new insights for its expression and function in the embryonic kidney. Dev Dyn, 2019. 248(4): p. 296-305.

- Tasca, C.I., et al., Neuromodulatory Effects of Guanine-Based Purines in Health and Disease. Front Cell Neurosci, 2018. 12: p. 376.

- Egeblad, L., et al., Pan-pathway based interaction profiling of FDA-approved nucleoside and nucleobase analogs with enzymes of the human nucleotide metabolism. PLoS One, 2012. 7(5): p. e37724.

- Sato, H., et al., Crystal structures of hydroxymethylbilane synthase complexed with a substrate analog: a single substrate-binding site for four consecutive condensation steps. Biochem J, 2021. 478(5): p. 1023-1042.

- Dawson, A., et al., Structure of diaminohydroxyphosphoribosylaminopyrimidine deaminase/5-amino-6-(5-phosphoribosylamino)uracil reductase from Acinetobacter baumannii. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun, 2013. 69(Pt 6): p. 611-.

- Kumasaka, T., et al., Crystal structures of blasticidin S deaminase (BSD): implications for dynamic properties of catalytic zinc. J Biol Chem, 2007. 282(51): p. 37103-11.

- Han, L., et al., Streptomyces wadayamensis MppP is a PLP-Dependent Oxidase, Not an Oxygenase. Biochemistry, 2018. 57(23): p. 3252-3264.

- Mok, B.Y., et al., A bacterial cytidine deaminase toxin enables CRISPR-free mitochondrial base editing. Nature, 2020. 583(7817): p. 631-637.

- Maiti, A., et al., Structure of the catalytically active APOBEC3G bound to a DNA oligonucleotide inhibitor reveals tetrahedral geometry of the transition state. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 7117.

- Arreola, R., et al., Two mammalian glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminases: a structural and genetic study. FEBS Lett, 2003. 551(1-3): p. 63-70.

- Holden, L.G., et al., Crystal structure of the anti-viral APOBEC3G catalytic domain and functional implications. Nature, 2008. 456(7218): p. 121-4.

- Mahan, S.D., et al., Random mutagenesis and selection of Escherichia coli cytosine deaminase for cancer gene therapy. Protein Eng Des Sel, 2004. 17(8): p. 625-33.

- Teh, A.H., et al., The 1.48 A resolution crystal structure of the homotetrameric cytidine deaminase from mouse. Biochemistry, 2006. 45(25): p. 7825-33.

- Johansson, E., et al., Structures of dCTP deaminase from Escherichia coli with bound substrate and product: reaction mechanism and determinants of mono- and bifunctionality for a family of enzymes. J Biol Chem, 2005. 280(4): p. 3051-9.

- Bitra, A., A. Biswas, and R. Anand, Structural basis of the substrate specificity of cytidine deaminase superfamily Guanine deaminase. Biochemistry, 2013. 52(45): p. 8106-14.

- Jia, Q., et al., Substrate Specificity of GSDA Revealed by Cocrystal Structures and Binding Studies. Int J Mol Sci, 2022. 23(23).

- Losey, H.C., A.J. Ruthenburg, and G.L. Verdine, Crystal structure of Staphylococcus aureus tRNA adenosine deaminase TadA in complex with RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2006. 13(2): p. 153-9.

- Kinoshita, T., et al., Structural basis of compound recognition by adenosine deaminase. Biochemistry, 2005. 44(31): p. 10562-9.

- Liang, J., et al., Current Advances on Structure-Function Relationships of Pyridoxal 5’-Phosphate-Dependent Enzymes. Front Mol Biosci, 2019. 6: p. 4.

- Gallagher, D.T., et al., Structure and control of pyridoxal phosphate dependent allosteric threonine deaminase. Structure, 1998. 6(4): p. 465-75.

- Yamada, T., et al., Crystal structure of serine dehydratase from rat liver. Biochemistry, 2003. 42(44): p. 12854-65.

- Yao, M., et al., Crystal structure of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase from Hansenula saturnus. J Biol Chem, 2000. 275(44): p. 34557-65.

- Han, L., et al., Streptomyces wadayamensis MppP Is a Pyridoxal 5’-Phosphate-Dependent L-Arginine alpha-Deaminase, gamma-Hydroxylase in the Enduracididine Biosynthetic Pathway. Biochemistry, 2015. 54(47): p. 7029-40.

- Conticello, S.G., The AID/APOBEC family of nucleic acid mutators. Genome Biol, 2008. 9(6): p. 229.

- Nabel, C.S., S.A. Manning, and R.M. Kohli, The curious chemical biology of cytosine: deamination, methylation, and oxidation as modulators of genomic potential. ACS Chem Biol, 2012. 7(1): p. 20-30.

- Borzooee, F., et al., Viral subversion of APOBEC3s: Lessons for anti-tumor immunity and tumor immunotherapy. Int Rev Immunol, 2018. 37(3): p. 151-164.

- Layer, G., et al., Structure and function of enzymes in heme biosynthesis. Protein Sci, 2010. 19(6): p. 1137-61.

- Roberts, A., et al., Insights into the mechanism of pyrrole polymerization catalysed by porphobilinogen deaminase: high-resolution X-ray studies of the Arabidopsis thaliana enzyme. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2013. 69(Pt 3): p. 471-85.

- Louie, G.V., et al., Structure of porphobilinogen deaminase reveals a flexible multidomain polymerase with a single catalytic site. Nature, 1992. 359(6390): p. 33-9.

- Song, G., et al., Structural insight into acute intermittent porphyria. FASEB J, 2009. 23(2): p. 396-404.

- Gill, R., et al., Structure of human porphobilinogen deaminase at 2.8 A: the molecular basis of acute intermittent porphyria. Biochem J, 2009. 420(1): p. 17-25.

- Pluta, P., et al., Structural basis of pyrrole polymerization in human porphobilinogen deaminase. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj, 2018. 1862(9): p. 1948-1955.

- Bustad, H.J., et al., Characterization of porphobilinogen deaminase mutants reveals that arginine-173 is crucial for polypyrrole elongation mechanism. iScience, 2021. 24(3): p. 102152.

- Helliwell, J.R., et al., Time-resolved and static-ensemble structural chemistry of hydroxymethylbilane synthase. Faraday Discuss, 2003. 122: p. 131-44; discussion 171-90.

- Azim, N., et al., Structural evidence for the partially oxidized dipyrromethene and dipyrromethanone forms of the cofactor of porphobilinogen deaminase: structures of the Bacillus megaterium enzyme at near-atomic resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2014. 70(Pt 3): p. 744-51.

- Guo, J., et al., Structural studies of domain movement in active-site mutants of porphobilinogen deaminase from Bacillus megaterium. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun, 2017. 73(Pt 11): p. 612-620.

- Funamizu, T., Chen, M., Tanaka, Y., Ishimori, K., Uchida, T., Porphobilinogen deaminase from Vibrio Cholerae. 2016.

- Vincent, F., G.J. Davies, and J.A. Brannigan, Structure and kinetics of a monomeric glucosamine 6-phosphate deaminase: missing link of the NagB superfamily? J Biol Chem, 2005. 280(20): p. 19649-55.

- Flores, C.L. and C. Gancedo, Construction and characterization of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain able to grow on glucosamine as sole carbon and nitrogen source. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 16949.

- Oliva, G., et al., Structure and catalytic mechanism of glucosamine 6-phosphate deaminase from Escherichia coli at 2.1 A resolution. Structure, 1995. 3(12): p. 1323-32.

- Horjales, E., et al., The allosteric transition of glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase: the structure of the T state at 2.3 A resolution. Structure, 1999. 7(5): p. 527-37.

- Rudino-Pinera, E., et al., Structural flexibility, an essential component of the allosteric activation in Escherichia coli glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2002. 58(Pt 1): p. 10-20.

- Bustos-Jaimes, I., et al., On the role of the conformational flexibility of the active-site lid on the allosteric kinetics of glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase. J Mol Biol, 2002. 319(1): p. 183-9.

- Rudino-Pinera, E., Rojas-Trejo, S.P., Horjales, E., Glucosamine-6-Phosphate Deaminase Complexed with the Allosteric Activator N-Acetyl-Glucoamine-6-Phosphate both in the Active and Allosteric sites. 2009.

- Liu, C., et al., Ring-opening mechanism revealed by crystal structures of NagB and its ES intermediate complex. J Mol Biol, 2008. 379(1): p. 73-81.

- (SSGCID), S.S.G.C.f.I.D., Crystal structure of glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase from Borrelia burgdorferi. 2009.

- Maltseva, N., Kim, Y., Kwon, K., Anderson, W.F., Joachimiak, A., CSGID, Center for Structural Genomics of Infectious Diseases (CSGID), Crystal structure of glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase from Vibrio cholerae. 2014.

- Chang, C., Maltseva, N., Kim, Y., Kwon, K., Anderson, W.F., Joachimiak, A., Center for Structural Genomics of Infectious Diseases (CSGID), Crystal structure of tertiary complex of glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase from Vibrio cholerae with BETA-D-GLUCOSE-6-PHOSPHATE and FRUCTOSE-6-PHOSPHATE. 2016.

- Minasov, G., Shuvalova, L., Kiryukhina, O., Dubrovska, I., Satchell, K.J.F., Joachimiak, A., Center for Structural Genomics of Infectious Diseases (CSGID), 2.05 Angstrom Resolution Crystal Structure of Hypothetical Protein KP1_5497 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. 2018.

- Subramanian, R., Srinivasachari, S., Glucosamie-6-phosphate Deaminase from Pasturella multocida. 2021.

- Subramanian, R., Srinivasachari, S., Glucosamine-6-phosphate Deaminase from H. influenzae. 2021.

- Stetter, G.F.a.K.O., Pyrococcus furiosus sp. nov. represents a novel genus of marine heterotrophic archaebacteria growing optimally at 100 °C. Arch. Microbiol., 1986. 145: p. 56-61.

- Blamey, J.M. and M.W. Adams, Characterization of an ancestral type of pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic bacterium, Thermotoga maritima. Biochemistry, 1994. 33(4): p. 1000-7.

- Kim, K.J., et al., The crystal structure of a novel glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Proteins, 2007. 68(1): p. 413-7.

- (JCSG), J.C.f.S.G., Crystal structure of Glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase (TM0813) from Thermotoga maritima at 1.8 A resolution. 2002.

- Teplyakov, A., et al., Channeling of ammonia in glucosamine-6-phosphate synthase. J Mol Biol, 2001. 313(5): p. 1093-102.

- Torrens-Spence, M.P., et al., Structural basis for divergent and convergent evolution of catalytic machineries in plant aromatic amino acid decarboxylase proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2020. 117(20): p. 10806-10817.

- Tanaka, H., et al., Crystal structure of a zinc-dependent D-serine dehydratase from chicken kidney. J Biol Chem, 2011. 286(31): p. 27548-58.

- Goto, M., RIKEN Structural Genomics/Proteomics Initiative (RSGI), Crystal Structure of T.th. HB8 Threonine deaminase. 2004.

- Simanshu, D.K., H.S. Savithri, and M.R. Murthy, Crystal structures of Salmonella typhimurium biodegradative threonine deaminase and its complex with CMP provide structural insights into ligand-induced oligomerization and enzyme activation. J Biol Chem, 2006. 281(51): p. 39630-41.

- Gonzales-Vigil, E., et al., Adaptive evolution of threonine deaminase in plant defense against insect herbivores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011. 108(14): p. 5897-902.

- Sun, L., et al., Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of human serine dehydratase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2003. 59(Pt 12): p. 2297-9.

- Bharath, S.R., et al., Crystal structures of open and closed forms of d-serine deaminase from Salmonella typhimurium - implications on substrate specificity and catalysis. FEBS J, 2011. 278(16): p. 2879-91.

- Urusova, D.V., et al., Crystal structure of D-serine dehydratase from Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2012. 1824(3): p. 422-32.

- Wang, C.Y., et al., Modulating the function of human serine racemase and human serine dehydratase by protein engineering. Protein Eng Des Sel, 2012. 25(11): p. 741-9.

- Deka, G., et al., Structural studies on the decameric S. typhimurium arginine decarboxylase (ADC): Pyridoxal 5’-phosphate binding induces conformational changes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2017. 490(4): p. 1362-1368.

- (JCSG), J.C.f.S.G., Crystal structure of a putative d-serine deaminase (bxe_a4060) from burkholderia xenovorans lb400 at 2.00 A resolution. 2009.

- Fujino, A., et al., Structural and enzymatic properties of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase homologue from Pyrococcus horikoshii. J Mol Biol, 2004. 341(4): p. 999-1013.

- Karthikeyan, S., et al., Structural analysis of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase: observation of an aminyl intermediate and identification of Tyr 294 as the active-site nucleophile. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2004. 43(26): p. 3425-9.

- Karthikeyan, S., et al., Structural analysis of Pseudomonas 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase complexes: insight into the mechanism of a unique pyridoxal-5’-phosphate dependent cyclopropane ring-opening reaction. Biochemistry, 2004. 43(42): p. 13328-39.

- Motta, P., et al., Structure-Function Relationships in l-Amino Acid Deaminase, a Flavoprotein Belonging to a Novel Class of Biotechnologically Relevant Enzymes. J Biol Chem, 2016. 291(20): p. 10457-75.

- Ju, Y., et al., Crystal structure of a membrane-bound l-amino acid deaminase from Proteus vulgaris. J Struct Biol, 2016. 195(3): p. 306-315.

- Niehaus, T.D., et al., Genomic and experimental evidence for multiple metabolic functions in the RidA/YjgF/YER057c/UK114 (Rid) protein family. BMC Genomics, 2015. 16(1): p. 382.

- Liu, X., et al., Crystal structures of RidA, an important enzyme for the prevention of toxic side products. Sci Rep, 2016. 6: p. 30494.

- Burman, J.D., et al., The crystal structure of Escherichia coli TdcF, a member of the highly conserved YjgF/YER057c/UK114 family. BMC Struct Biol, 2007. 7: p. 30.

- Digiovanni, S., et al., Two novel fish paralogs provide insights into the Rid family of imine deaminases active in pre-empting enamine/imine metabolic damage. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 10135.

- Deriu, D., et al., Structure and oligomeric state of the mammalian tumour-associated antigen UK114. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2003. 59(Pt 9): p. 1676-8.

- Manjasetty, B.A., et al., Crystal structure of Homo sapiens protein hp14.5. Proteins, 2004. 54(4): p. 797-800.

- Kwon, S., et al., Crystal structure of the reactive intermediate/imine deaminase A homolog from the Antarctic bacterium Psychrobacter sp. PAMC 21119. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2020. 522(3): p. 585-591.

- Visentin, C., et al., Apis mellifera RidA, a novel member of the canonical YigF/YER057c/UK114 imine deiminase superfamily of enzymes pre-empting metabolic damage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2022. 616: p. 70-75.

- Chen, Y., et al., A Unique Homo-Hexameric Structure of 2-Aminomuconate Deaminase in the Bacterium Pseudomonas species AP-3. Front Microbiol, 2019. 10: p. 2079.

- Chen, S., et al., L-Hydroxyproline and d-Proline Catabolism in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol, 2016. 198(7): p. 1171-81.

- (SSGCID), S.S.G.C.f.I.D., Crystal structure of1-pyrroline-4-hydroxy-2-carboxylate deaminase from Brucella melitensis ATCC 23457. 2013.

- (SSGCID), S.S.G.C.f.I.D., Crystal structure of 1-pyrroline-4-hydroxy-2-carboxylate deaminase from Brucella melitensis with covalently bound substrate. 2013.

- Fernandez, J.R., B. Byrne, and B.L. Firestein, Phylogenetic analysis and molecular evolution of guanine deaminases: from guanine to dendrites. J Mol Evol, 2009. 68(3): p. 227-35.

- Bitra, A., et al., Identification of function and mechanistic insights of guanine deaminase from Nitrosomonas europaea: role of the C-terminal loop in catalysis. Biochemistry, 2013. 52(20): p. 3512-22.

- Hall, R.S., et al., Discovery and structure determination of the orphan enzyme isoxanthopterin deaminase. Biochemistry, 2010. 49(20): p. 4374-82.

- Murphy, P.M., et al., Alteration of enzyme specificity by computational loop remodeling and design. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009. 106(23): p. 9215-20.

- Kumaran, D., Burley, S.K., Swaminathan, S., New York SGX Research Center for Structural Genomics (NYSGXRC), Crystal Structure of Guanine Deaminase from C. acetobutylicum with bound guanine in the active site. TBA.

- Agarwal, R., Burley, S.K., Swaminathan, S., New York SGX Research Center for Structural Genomics (NYSGXRC), Crystal structure of guanine deaminase from Bradyrhizobium japonicum. 2007.

- Moche, M., et al., Human Guanine Deaminase (Guad) in Complex with Zinc and its Product Xhantine. 2007.

- Shek, R., et al., Structural Determinants for Substrate Selectivity in Guanine Deaminase Enzymes of the Amidohydrolase Superfamily. Biochemistry, 2019. 58(30): p. 3280-3292.

- Hall, R.S., et al., The hunt for 8-oxoguanine deaminase. J Am Chem Soc, 2010. 132(6): p. 1762-3.

- Mariam, J., et al., Deciphering protein microenvironment by using a cysteine specific switch-ON fluorescent probe. Org Biomol Chem, 2021. 19(23): p. 5161-5168.

- Liaw, S.H., et al., Crystal structure of Bacillus subtilis guanine deaminase: the first domain-swapped structure in the cytidine deaminase superfamily. J Biol Chem, 2004. 279(34): p. 35479-85.

- Singh, J., et al., Structure guided mutagenesis reveals the substrate determinants of guanine deaminase. J Struct Biol, 2021. 213(3): p. 107747.

- Jia, Q., et al., The C-terminal loop of Arabidopsis thaliana guanosine deaminase is essential to catalysis. Chem Commun (Camb), 2021. 57(76): p. 9748-9751.

- Kamat, S.S., et al., Catalytic mechanism and three-dimensional structure of adenine deaminase. Biochemistry, 2011. 50(11): p. 1917-27.

- Kamat, S.S., et al., The catalase activity of diiron adenine deaminase. Protein Sci, 2011. 20(12): p. 2080-94.

- Wilson, D.K. and F.A. Quiocho, A pre-transition-state mimic of an enzyme: X-ray structure of adenosine deaminase with bound 1-deazaadenosine and zinc-activated water. Biochemistry, 1993. 32(7): p. 1689-94.

- Terasaka, T., et al., A highly potent non-nucleoside adenosine deaminase inhibitor: efficient drug discovery by intentional lead hybridization. J Am Chem Soc, 2004. 126(1): p. 34-5.

- Han, B.W., et al., Membrane association, mechanism of action, and structure of Arabidopsis embryonic factor 1 (FAC1). J Biol Chem, 2006. 281(21): p. 14939-47.

- Sugadev, R., Kumaran, D., Burley, S.K., Swaminathan, S., New York SGX Research Center for Structural Genomics (NYSGXRC), Crystal structure of an adenine deaminase. 2006.

- Guan, R., et al., Methylthioadenosine deaminase in an alternative quorum sensing pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry, 2012. 51(45): p. 9094-103.

- Hitchcock, D.S., et al., Structure-guided discovery of new deaminase enzymes. J Am Chem Soc, 2013. 135(37): p. 13927-33.

- Goble, A.M., et al., Pa0148 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa catalyzes the deamination of adenine. Biochemistry, 2011. 50(30): p. 6589-97.

- Goble, A.M., et al., Deamination of 6-aminodeoxyfutalosine in menaquinone biosynthesis by distantly related enzymes. Biochemistry, 2013. 52(37): p. 6525-36.

- Feng, M., et al., Aminofutalosine Deaminase in the Menaquinone Pathway of Helicobacter pylori. Biochemistry, 2021. 60(24): p. 1933-1946.

- Terasaka, T., et al., Structure-based design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship studies of novel non-nucleoside adenosine deaminase inhibitors. J Med Chem, 2004. 47(15): p. 3730-43.

- Niu, W., et al., The role of Zn2+ on the structure and stability of murine adenosine deaminase. J Phys Chem B, 2010. 114(49): p. 16156-65.

- Weihofen, W.A., et al., Crystal structures of HIV-1 Tat-derived nonapeptides Tat-(1-9) and Trp2-Tat-(1-9) bound to the active site of dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (CD26). J Biol Chem, 2005. 280(15): p. 14911-7.

- Terasaka, T., et al., Structure-based design and synthesis of non-nucleoside, potent, and orally bioavailable adenosine deaminase inhibitors. J Med Chem, 2004. 47(11): p. 2728-31.

- Weihofen, W.A., et al., Crystal structure of CD26/dipeptidyl-peptidase IV in complex with adenosine deaminase reveals a highly amphiphilic interface. J Biol Chem, 2004. 279(41): p. 43330-5.

- Terasaka, T., et al., Rational design of non-nucleoside, potent, and orally bioavailable adenosine deaminase inhibitors: predicting enzyme conformational change and metabolism. J Med Chem, 2005. 48(15): p. 4750-3.

- Kinoshita, T., T. Tada, and I. Nakanishi, Conformational change of adenosine deaminase during ligand-exchange in a crystal. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2008. 373(1): p. 53-7.

- Vedadi, M., et al., Genome-scale protein expression and structural biology of Plasmodium falciparum and related Apicomplexan organisms. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 2007. 151(1): p. 100-10.

- Ma, M.T., et al., Catalytically active holo Homo sapiens adenosine deaminase I adopts a closed conformation. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol, 2022. 78(Pt 1): p. 91-103.

- Jaruwat, A., et al., Crystal structure of Plasmodium falciparum adenosine deaminase reveals a novel binding pocket for inosine. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2019. 667: p. 6-13.

- Gao, Z.W., et al., Distinct Roles of Adenosine Deaminase Isoenzymes ADA1 and ADA2: A Pan-Cancer Analysis. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: p. 903461.

- Jia, Q. and W. Xie, Alternative conformation induced by substrate binding for Arabidopsis thalianaN6-methyl-AMP deaminase. Nucleic Acids Res, 2019. 47(6): p. 3233-3243.

- Wu, B., et al., Structure of Arabidopsis thaliana N(6)-methyl-AMP deaminase ADAL with bound GMP and IMP and implications for N(6)-methyl-AMP recognition and processing. RNA Biol, 2019. 16(10): p. 1504-1512.

- Cader, M.Z., et al., FAMIN Is a Multifunctional Purine Enzyme Enabling the Purine Nucleotide Cycle. Cell, 2020. 180(2): p. 278-295 e23.

- Lee, M.S., et al., Structural Basis for the Peptidoglycan-Editing Activity of YfiH. mBio, 2022. 13(1): p. e0364621.

- Minasov, G., Shuvalova, L., Mondragon, A., Taneja, B., Moy, S.F., Collart, F.R., Anderson, W.F., Midwest Center for Structural Genomics (MCSG), 1.8 A CRYSTAL STRUCTURE OF AN UNCHARACTERIZED B. STEAROTHERMOPHILUS PROTEIN. 2004.

- Seetharaman, J., Swaminathan, S., Burley, S.K., New York SGX Research Center for Structural Genomics (NYSGXRC), Crystal structure of protein yfiH from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, Pfam DUF152. 2003.

- Seetharaman, J., Swaminathan, S., Burley, S.K., New York SGX Research Center for Structural Genomics (NYSGXRC), Crystal structure of protein yfiH from Shigella flexneri, Pfam DUF152. 2004.

- Almeida, L.R., Grejo, M.P., Mulinari, E.J., Santos, J.C., Camargo, S., Bernardes, A., Muniz, J.R.C., Crystal structure of Bacillus licheniformis hypothetical protein YfiH. 2018.

- Elias, Y. and R.H. Huang, Biochemical and structural studies of A-to-I editing by tRNA:A34 deaminases at the wobble position of transfer RNA. Biochemistry, 2005. 44(36): p. 12057-65.

- Kuratani, M., et al., Crystal structure of tRNA adenosine deaminase (TadA) from Aquifex aeolicus. J Biol Chem, 2005. 280(16): p. 16002-8.

- Kim, J., et al., Structural and kinetic characterization of Escherichia coli TadA, the wobble-specific tRNA deaminase. Biochemistry, 2006. 45(20): p. 6407-16.

- Dolce, L.G., et al., Structural basis for sequence-independent substrate selection by eukaryotic wobble base tRNA deaminase ADAT2/3. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 6737.

- Liu, X., et al., Crystal structure of the yeast heterodimeric ADAT2/3 deaminase. BMC Biol, 2020. 18(1): p. 189.

- Liu, H., et al., Structure of a tRNA-specific deaminase with compromised deamination activity. Biochem J, 2020. 477(8): p. 1483-1497.

- Lee, W.H., et al., Crystal structure of the tRNA-specific adenosine deaminase from Streptococcus pyogenes. Proteins, 2007. 68(4): p. 1016-9.

- Lapinaite, A., et al., DNA capture by a CRISPR-Cas9-guided adenine base editor. Science, 2020. 369(6503): p. 566-571.

- Lam, D.K., et al., Improved cytosine base editors generated from TadA variants. Nat Biotechnol, 2023.

- Liu, X., et al., Functional and structural investigation of N-terminal domain of the SpTad2/3 heterodimeric tRNA deaminase. Comput Struct Biotechnol J, 2021. 19: p. 3384-3393.

- Ramos-Morales, E., et al., The structure of the mouse ADAT2/ADAT3 complex reveals the molecular basis for mammalian tRNA wobble adenosine-to-inosine deamination. Nucleic Acids Res, 2021. 49(11): p. 6529-6548.

- Keegan, L.P., et al., Adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs): RNA-editing enzymes. Genome Biol, 2004. 5(2): p. 209.

- Welin, M., Tresaugues, L., Andersson, J., Arrowsmith, C.H., Berglund, H., Collins, R., Dahlgren, L.G., Edwards, A.M., Flodin, S., Flores, A., Graslund, S., Hammarstrom, M., Johansson, A., Johansson, I., Karlberg, T., Kotenyova, T., Lehtio, L., Moche, M., Nilsson, M.E., Nyman, T., Olesen, K., Persson, C., Sagemark, J., Schueler, H., Thorsell, A.G., van der Berg, S., Wisniewska, M., Wikstrom, M., Nordlund, P., Crystal structure of human tRNA-specific adenosine-34 deaminase subunit ADAT2. 2008.

- Hood, J.L. and R.B. Emeson, Editing of neurotransmitter receptor and ion channel RNAs in the nervous system. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol, 2012. 353: p. 61-90.

- Barraud, P. and F.H. Allain, ADAR proteins: double-stranded RNA and Z-DNA binding domains. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol, 2012. 353: p. 35-60.

- Wulff, B.E. and K. Nishikura, Modulation of microRNA expression and function by ADARs. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol, 2012. 353: p. 91-109.

- Piontkivska, H., et al., ADAR Editing in Viruses: An Evolutionary Force to Reckon with. Genome Biol Evol, 2021. 13(11).

- Orecchini, E., et al., ADAR1 restricts LINE-1 retrotransposition. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017. 45(1): p. 155-168.

- Thuy-Boun, A.S., et al., Asymmetric dimerization of adenosine deaminase acting on RNA facilitates substrate recognition. Nucleic Acids Res, 2020. 48(14): p. 7958-7972.

- Schwartz, T., et al., Crystal structure of the Zalpha domain of the human editing enzyme ADAR1 bound to left-handed Z-DNA. Science, 1999. 284(5421): p. 1841-5.

- Schwartz, T., et al., Structure of the DLM-1-Z-DNA complex reveals a conserved family of Z-DNA-binding proteins. Nat Struct Biol, 2001. 8(9): p. 761-5.

- Placido, D., et al., A left-handed RNA double helix bound by the Z alpha domain of the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1. Structure, 2007. 15(4): p. 395-404.

- Ha, S.C., et al., Crystal structure of a junction between B-DNA and Z-DNA reveals two extruded bases. Nature, 2005. 437(7062): p. 1183-6.

- Schade, M., et al., The solution structure of the Zalpha domain of the human RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 reveals a prepositioned binding surface for Z-DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1999. 96(22): p. 12465-70.

- Athanasiadis, A., et al., The crystal structure of the Zbeta domain of the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1 reveals distinct conserved surfaces among Z-domains. J Mol Biol, 2005. 351(3): p. 496-507.

- Feng, S., et al., Alternate rRNA secondary structures as regulators of translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2011. 18(2): p. 169-76.

- Kim, D., et al., Sequence preference and structural heterogeneity of BZ junctions. Nucleic Acids Res, 2018. 46(19): p. 10504-10513.

- Ha, S.C., et al., The structures of non-CG-repeat Z-DNAs co-crystallized with the Z-DNA-binding domain, hZ alpha(ADAR1). Nucleic Acids Res, 2009. 37(2): p. 629-37.

- de Rosa, M., et al., Crystal structure of a junction between two Z-DNA helices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(20): p. 9088-92.

- Park, C., et al., Dual conformational recognition by Z-DNA binding protein is important for the B-Z transition process. Nucleic Acids Res, 2020. 48(22): p. 12957-12971.

- Barraud, P., et al., A bimodular nuclear localization signal assembled via an extended double-stranded RNA-binding domain acts as an RNA-sensing signal for transportin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014. 111(18): p. E1852-61.

- Stefl, R., et al., Structure and specific RNA binding of ADAR2 double-stranded RNA binding motifs. Structure, 2006. 14(2): p. 345-55.

- Stefl, R., et al., The solution structure of the ADAR2 dsRBM-RNA complex reveals a sequence-specific readout of the minor groove. Cell, 2010. 143(2): p. 225-37.

- Macbeth, M.R., et al., Inositol hexakisphosphate is bound in the ADAR2 core and required for RNA editing. Science, 2005. 309(5740): p. 1534-9.

- Matthews, M.M., et al., Structures of human ADAR2 bound to dsRNA reveal base-flipping mechanism and basis for site selectivity. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2016. 23(5): p. 426-33.

- Monteleone, L.R., et al., A Bump-Hole Approach for Directed RNA Editing. Cell Chem Biol, 2019. 26(2): p. 269-277 e5.

- Doherty, E.E., et al., Rational Design of RNA Editing Guide Strands: Cytidine Analogs at the Orphan Position. J Am Chem Soc, 2021. 143(18): p. 6865-6876.

- Doherty, E.E., et al., ADAR activation by inducing a syn conformation at guanosine adjacent to an editing site. Nucleic Acids Res, 2022. 50(19): p. 10857-10868.

- Ireton, G.C., et al., The structure of Escherichia coli cytosine deaminase. J Mol Biol, 2002. 315(4): p. 687-97.

- Ireton, G.C., M.E. Black, and B.L. Stoddard, The 1.14 A crystal structure of yeast cytosine deaminase: evolution of nucleotide salvage enzymes and implications for genetic chemotherapy. Structure, 2003. 11(8): p. 961-72.

- Hall, R.S., et al., Three-dimensional structure and catalytic mechanism of cytosine deaminase. Biochemistry, 2011. 50(22): p. 5077-85.

- Ko, T.P., et al., Crystal structure of yeast cytosine deaminase. Insights into enzyme mechanism and evolution. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(21): p. 19111-7.

- Hitchcock, D.S., et al., Rescue of the orphan enzyme isoguanine deaminase. Biochemistry, 2011. 50(25): p. 5555-7.

- Hitchcock, D.S., et al., Discovery of a bacterial 5-methylcytosine deaminase. Biochemistry, 2014. 53(47): p. 7426-35.

- Ireton, G.C. and B.L. Stoddard, Microseed matrix screening to improve crystals of yeast cytosine deaminase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2004. 60(Pt 3): p. 601-5.

- Korkegian, A., et al., Computational thermostabilization of an enzyme. Science, 2005. 308(5723): p. 857-60.

- Korkegian, A.M., Stoddard, B.L., Yeast Cytosine Deaminase D92E Triple Mutant bound to transition state analogue HPY. 2006.

- Fuchita, M., et al., Bacterial cytosine deaminase mutants created by molecular engineering show improved 5-fluorocytosine-mediated cell killing in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res, 2009. 69(11): p. 4791-9.

- Gaded, V. and R. Anand, Selective Deamination of Mutagens by a Mycobacterial Enzyme. J Am Chem Soc, 2017. 139(31): p. 10762-10768.

- Johansson, E., et al., Crystal structure of the tetrameric cytidine deaminase from Bacillus subtilis at 2.0 A resolution. Biochemistry, 2002. 41(8): p. 2563-70.

- Chung, S.J., J.C. Fromme, and G.L. Verdine, Structure of human cytidine deaminase bound to a potent inhibitor. J Med Chem, 2005. 48(3): p. 658-60.

- Xie, K., et al., The structure of a yeast RNA-editing deaminase provides insight into the fold and function of activation-induced deaminase and APOBEC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(21): p. 8114-9.

- Taylor, L., Crystal structure of a plant cytidine deaminase. 2016.

- Johansson, E., et al., Structural, kinetic, and mutational studies of the zinc ion environment in tetrameric cytidine deaminase. Biochemistry, 2004. 43(20): p. 6020-9.

- Liu, W., et al., Biochemical and structural analysis of the Klebsiella pneumoniae cytidine deaminase CDA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2019. 519(2): p. 280-286.

- Levdikov, V.M., Blagova, E.V., Fogg, M.J., Brannigan, J.A., Moroz, O.V., Wilkinson, A.J., Wilson, K.S., Crystal Structure of Cytidine Deaminase Cdd-2 (BA4525) from Bacillus Anthracis at 2.40A Resolution. 2005.

- Sanchez-Quitian, Z.A., et al., Structural and functional analyses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3315c-encoded metal-dependent homotetrameric cytidine deaminase. J Struct Biol, 2010. 169(3): p. 413-23.

- Sanchez-Quitian, Z.A., Rodrigues-Junior, E., Rehm, J.G., Eichler, P., Trivella, D.B.B., Bizarro, C.V., Basso, L.A., Santos, D.S., Functional and structural evidence for the catalytic role played by glutamate-47 residue in the mode of action of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cytidine deaminase. Rsc Adv, 2015. 5: p. 830-840.

- Baugh, L., et al., Increasing the structural coverage of tuberculosis drug targets. Tuberculosis (Edinb), 2015. 95(2): p. 142-8.

- (SSGCID), S.S.G.C.f.I.D., Crystal structure of Blasticidin S Deaminase from Coccidioides Immitis. 2010.

- Wang, J., et al., Crystal structure of Arabidopsis thaliana cytidine deaminase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2020. 529(3): p. 659-665.

- Xiang, S., et al., Transition-state selectivity for a single hydroxyl group during catalysis by cytidine deaminase. Biochemistry, 1995. 34(14): p. 4516-23.

- Xiang, S., et al., Cytidine deaminase complexed to 3-deazacytidine: a “valence buffer” in zinc enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry, 1996. 35(5): p. 1335-41.

- Xiang, S., et al., The structure of the cytidine deaminase-product complex provides evidence for efficient proton transfer and ground-state destabilization. Biochemistry, 1997. 36(16): p. 4768-74.

- Minasov, G., Wawrzak, Z., Skarina, T., Wang, Y., Grimshaw, S., Papazisi, L., Savchenko, A., Anderson, W.F., Center for Structural Genomics of Infectious Diseases (CSGID), 2.2 Angstrom Crystal Structure of Cytidine deaminase from Vibrio cholerae in Complex with Zinc and Uridine. 2012.

- Almog, R., et al., Three-dimensional structure of the R115E mutant of T4-bacteriophage 2’-deoxycytidylate deaminase. Biochemistry, 2004. 43(43): p. 13715-23.

- Maiti, A., et al., Crystal Structure of a Soluble APOBEC3G Variant Suggests ssDNA to Bind in a Channel that Extends between the Two Domains. J Mol Biol, 2020. 432(23): p. 6042-6060.

- Xiao, X., et al., Structural determinants of APOBEC3B non-catalytic domain for molecular assembly and catalytic regulation. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017. 45(12): p. 7494-7506.

- Prochnow, C., et al., The APOBEC-2 crystal structure and functional implications for the deaminase AID. Nature, 2007. 445(7126): p. 447-51.

- Johansson, E., et al., Regulation of dCTP deaminase from Escherichia coli by nonallosteric dTTP binding to an inactive form of the enzyme. FEBS J, 2007. 274(16): p. 4188-98.

- Oehlenschlaeger, C.B., et al., Bacillus halodurans Strain C125 Encodes and Synthesizes Enzymes from Both Known Pathways To Form dUMP Directly from Cytosine Deoxyribonucleotides. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2015. 81(10): p. 3395-404.

- Thymark, M., et al., Mutational analysis of the nucleotide binding site of Escherichia coli dCTP deaminase. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2008. 470(1): p. 20-6.

- Abendroth, J., et al., SAD phasing using iodide ions in a high-throughput structural genomics environment. J Struct Funct Genomics, 2011. 12(2): p. 83-95.

- Baugh, L., et al., Combining functional and structural genomics to sample the essential Burkholderia structome. PLoS One, 2013. 8(1): p. e53851.

- Johansson, E., et al., Structure of the bifunctional dCTP deaminase-dUTPase from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii and its relation to other homotrimeric dUTPases. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(30): p. 27916-22.

- Zhang, R., Dong, A., Xu, X., Savchenko, A., Edwards, A.M., Joachimiak, A., Midwest Center for Structural Genomics (MCSG), Crystal structure of 2’-deoxycytidine 5’-triphosphate deaminase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. 2007.

- Helt, S.S., et al., Mechanism of dTTP inhibition of the bifunctional dCTP deaminase:dUTPase encoded by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Biol, 2008. 376(2): p. 554-69.

- Huffman, J.L., et al., Structural basis for recognition and catalysis by the bifunctional dCTP deaminase and dUTPase from Methanococcus jannaschii. J Mol Biol, 2003. 331(4): p. 885-96.

- Hou, H.F., et al., Crystal structures of Streptococcus mutans 2’-deoxycytidylate deaminase and its complex with substrate analog and allosteric regulator dCTP x Mg2+. J Mol Biol, 2008. 377(1): p. 220-31.

- Li, Y., et al., Mechanism of the allosteric regulation of Streptococcus mutans 2’-deoxycytidylate deaminase. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol, 2016. 72(Pt 7): p. 883-91.

- Siponen, M.I., Moche, M., Arrowsmith, C.H., Berglund, H., Bountra, C., Collins, R., Dahlgren, L.G., Edwards, A.M., Flodin, S., Flores, A., Graslund, S., Hammarstrom, M., Johansson, A., Johansson, I., Karlberg, T., Kotenyova, T., Lehtio, L., Nilsson, M.E., Nyman, T., Persson, C., Sagemark, J., Schuler, H., Thorsell, A.G., Tresaugues, L., Van Den Berg, S., Weigelt, J., Welin, M., Wikstrom, M., Wisniewska, M., Nordlund, P., The Crystal Structure of Human Dcmp Deaminase. 2008.

- Marx, A. and A. Alian, The first crystal structure of a dTTP-bound deoxycytidylate deaminase validates and details the allosteric-inhibitor binding site. J Biol Chem, 2015. 290(1): p. 682-90.

- Li, Y.H., et al., Structural basis of a multi-functional deaminase in chlorovirus PBCV-1. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2022. 727: p. 109339.

- Lovgreen, M.N., Harris, P., Ucar, E., Willemoes, M., Dttp Inhibition of the Bifunctional Dctp Deaminase- Dutpase from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis is Ph Dependent: Kinetic Analyses and Crystal Structure of A115V Variant. 2011.

- Stenmark, P., et al., The crystal structure of the bifunctional deaminase/reductase RibD of the riboflavin biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli: implications for the reductive mechanism. J Mol Biol, 2007. 373(1): p. 48-64.

- Chen, S.C., et al., Complex structure of Bacillus subtilis RibG: the reduction mechanism during riboflavin biosynthesis. J Biol Chem, 2009. 284(3): p. 1725-31.

- Chen, S.C., et al., Crystal structure of a bifunctional deaminase and reductase from Bacillus subtilis involved in riboflavin biosynthesis. J Biol Chem, 2006. 281(11): p. 7605-13.

- Chen, S.C., et al., Evolution of vitamin B2 biosynthesis: eubacterial RibG and fungal Rib2 deaminases. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2013. 69(Pt 2): p. 227-36.

- Chen, S.C., et al., Crystal structures of Aspergillus oryzae Rib2 deaminase: the functional mechanism involved in riboflavin biosynthesis. IUCrJ, 2021. 8(Pt 4): p. 549-558.

- Averianova, L.A., et al., Production of Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) by Microorganisms: An Overview. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2020. 8: p. 570828.

- (JCSG), J.C.f.S.G., Crystal structure of a diaminohydroxyphosphoribosylaminopyrimidine deaminase/ 5-amino-6-(5-phosphoribosylamino)uracil reductase (tm1828) from thermotoga maritima at 1.80 A resolution. 2006.

- Hajian, B., et al., Drugging the Folate Pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: The Role of Multi-targeting Agents. Cell Chem Biol, 2019. 26(6): p. 781-791 e6.

- Bonomi, H.R., Cerutti, M.L., Posadas, D.M., Goldbaum, F.A., Klinke, S., C-terminal domain of RibD from Brucella abortus (5-amino-6-ribosylamino-2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione 5’-phosphate reductase). 2021.

- Takenaka, M., et al., DYW domain structures imply an unusual regulation principle in plant organellar RNA editing catalysis. Nat Catal, 2021. 4(6): p. 510-522.

- Randau, L., et al., A cytidine deaminase edits C to U in transfer RNAs in Archaea. Science, 2009. 324(5927): p. 657-9.

- Toma-Fukai, S., et al., Structural insight into the activation of an Arabidopsis organellar C-to-U RNA editing enzyme by active site complementation. Plant Cell, 2023. 35(6): p. 1888-1900.

- de Moraes, M.H., et al., An interbacterial DNA deaminase toxin directly mutagenizes surviving target populations. Elife, 2021. 10.

- Yin, L., K. Shi, and H. Aihara, Structural basis of sequence-specific cytosine deamination by double-stranded DNA deaminase toxin DddA. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2023.

- Cho, S.I., et al., Targeted A-to-G base editing in human mitochondrial DNA with programmable deaminases. Cell, 2022. 185(10): p. 1764-1776 e12.

- Pham, P., et al., Structural analysis of the activation-induced deoxycytidine deaminase required in immunoglobulin diversification. DNA Repair (Amst), 2016. 43: p. 48-56.

- Wolfe, A.D., et al., The structure of APOBEC1 and insights into its RNA and DNA substrate selectivity. NAR Cancer, 2020. 2(4): p. zcaa027.

- Yaping Liu, W.L., Chunxi Wang, Chunyang Cao, Two different kinds of interaction modes of deaminase APOBEC3A with single-stranded DNA in solution detected by nuclear magnetic resonance. Protein Science, 2021. 31(2).

- Shi, K., et al., Conformational Switch Regulates the DNA Cytosine Deaminase Activity of Human APOBEC3B. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 17415.

- Shaban, N.M., et al., 1.92 Angstrom Zinc-Free APOBEC3F Catalytic Domain Crystal Structure. J Mol Biol, 2016. 428(11): p. 2307-2316.

- Yang, H., et al., Understanding the structural basis of HIV-1 restriction by the full length double-domain APOBEC3G. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 632.

- Bohn, J.A., et al., APOBEC3H structure reveals an unusual mechanism of interaction with duplex RNA. Nat Commun, 2017. 8(1): p. 1021.

- Krishnan, A., et al., Diversification of AID/APOBEC-like deaminases in metazoa: multiplicity of clades and widespread roles in immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2018. 115(14): p. E3201-E3210.

- Quinlan, E.M., et al., Biochemical Regulatory Features of Activation-Induced Cytidine Deaminase Remain Conserved from Lampreys to Humans. Mol Cell Biol, 2017. 37(20).

- Ghorbani, A., et al., Ancestral reconstruction reveals catalytic inactivation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase concomitant with cold water adaption in the Gadiformes bony fish. BMC Biol, 2022. 20(1): p. 293.

- Shi, K., et al., Crystal Structure of the DNA Deaminase APOBEC3B Catalytic Domain. J Biol Chem, 2015. 290(47): p. 28120-30.

- Damsteegt, E.L., A. Davie, and P.M. Lokman, The evolution of apolipoprotein B and its mRNA editing complex. Does the lack of editing contribute to hypertriglyceridemia? Gene, 2018. 641: p. 46-54.

- Modenini, G., P. Abondio, and A. Boattini, The coevolution between APOBEC3 and retrotransposons in primates. Mob DNA, 2022. 13(1): p. 27.

- Hayward, J.A., et al., Differential Evolution of Antiretroviral Restriction Factors in Pteropid Bats as Revealed by APOBEC3 Gene Complexity. Mol Biol Evol, 2018. 35(7): p. 1626-1637.

- Salter, J.D., R.P. Bennett, and H.C. Smith, The APOBEC Protein Family: United by Structure, Divergent in Function. Trends Biochem Sci, 2016. 41(7): p. 578-594.

- Sawyer, S.L., M. Emerman, and H.S. Malik, Ancient adaptive evolution of the primate antiviral DNA-editing enzyme APOBEC3G. PLoS Biol, 2004. 2(9): p. E275.

- Munk, C., A. Willemsen, and I.G. Bravo, An ancient history of gene duplications, fusions and losses in the evolution of APOBEC3 mutators in mammals. BMC Evol Biol, 2012. 12: p. 71.

- Nakano, Y., et al., A conflict of interest: the evolutionary arms race between mammalian APOBEC3 and lentiviral Vif. Retrovirology, 2017. 14(1): p. 31.

- Byeon, I.J., et al., Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Structure of the APOBEC3B Catalytic Domain: Structural Basis for Substrate Binding and DNA Deaminase Activity. Biochemistry, 2016. 55(21): p. 2944-59.

- Bohn, M.F., et al., The ssDNA Mutator APOBEC3A Is Regulated by Cooperative Dimerization. Structure, 2015. 23(5): p. 903-11.

- Kouno, T., et al., Crystal structure of APOBEC3A bound to single-stranded DNA reveals structural basis for cytidine deamination and specificity. Nat Commun, 2017. 8: p. 15024.

- Kitamura, S., et al., The APOBEC3C crystal structure and the interface for HIV-1 Vif binding. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2012. 19(10): p. 1005-10.

- Siu, K.K., et al., Structural determinants of HIV-1 Vif susceptibility and DNA binding in APOBEC3F. Nat Commun, 2013. 4: p. 2593.

- Shi, K., et al., Structural basis for targeted DNA cytosine deamination and mutagenesis by APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2017. 24(2): p. 131-139.

- Byeon, I.J., et al., NMR structure of human restriction factor APOBEC3A reveals substrate binding and enzyme specificity. Nat Commun, 2013. 4: p. 1890.

- Hirabayashi, S., et al., APOBEC3B is preferentially expressed at the G2/M phase of cell cycle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2021. 546: p. 178-184.

- Shaban, N.M., et al., The Antiviral and Cancer Genomic DNA Deaminase APOBEC3H Is Regulated by an RNA-Mediated Dimerization Mechanism. Mol Cell, 2018. 69(1): p. 75-86 e9.

- Vasudevan, A.A.J., et al., Loop 1 of APOBEC3C regulates its antiviral activity against HIV-1. bioRxiv preprint, 2020: p. 1-67.

- Koning, F.A., et al., Defining APOBEC3 expression patterns in human tissues and hematopoietic cell subsets. J Virol, 2009. 83(18): p. 9474-85.

- Mohanram, V., et al., IFN-alpha induces APOBEC3G, F, and A in immature dendritic cells and limits HIV-1 spread to CD4+ T cells. J Immunol, 2013. 190(7): p. 3346-53.

- Peng, G., et al., Induction of APOBEC3 family proteins, a defensive maneuver underlying interferon-induced anti-HIV-1 activity. J Exp Med, 2006. 203(1): p. 41-6.

- Milewska, A., et al., APOBEC3-mediated restriction of RNA virus replication. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 5960.

- Wang, S.M. and C.T. Wang, APOBEC3G cytidine deaminase association with coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. Virology, 2009. 388(1): p. 112-20.

- Cheng, A.Z., et al., Epstein-Barr virus BORF2 inhibits cellular APOBEC3B to preserve viral genome integrity. Nat Microbiol, 2019. 4(1): p. 78-88.

- Shaban, N.M., et al., Cryo-EM structure of the EBV ribonucleotide reductase BORF2 and mechanism of APOBEC3B inhibition. Sci Adv, 2022. 8(17): p. eabm2827.

- Matsuoka, T., et al., Structural basis of chimpanzee APOBEC3H dimerization stabilized by double-stranded RNA. Nucleic Acids Res, 2018.

- Cheng, C., Zhang, T., Wang, C., Lan, W., Ding, J., Cao, C., Crystal Structure of Cytidine Deaminase Human APOBEC3F Chimeric Catalytic Domain in Complex with DNA. Chinese Journal of Chemistry, 2019. 36(12).

- Yan, X., et al., Structural Investigations on the Interactions between Cytidine Deaminase Human APOBEC3G and DNA. Chem Asian J, 2019. 14(13): p. 2235-2241.

- Yang, H., et al., Structural basis of sequence-specific RNA recognition by the antiviral factor APOBEC3G. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 7498.

- Wang, J., et al., Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Vif and Human APOBEC3B Interactions Resemble Those between HIV-1 Vif and Human APOBEC3G. J Virol, 2018. 92(12).

- Delviks-Frankenberry, K.A., B.A. Desimmie, and V.K. Pathak, Structural Insights into APOBEC3-Mediated Lentiviral Restriction. Viruses, 2020. 12(6).

- Nakashima, M., et al., Structural Insights into HIV-1 Vif-APOBEC3F Interaction. J Virol, 2016. 90(2): p. 1034-47.

- Hu, Y., et al., Structural basis of antagonism of human APOBEC3F by HIV-1 Vif. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2019. 26(12): p. 1176-1183.

- Kouno, T., et al., Structure of the Vif-binding domain of the antiviral enzyme APOBEC3G. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2015. 22(6): p. 485-91.

- Xiao, X., et al., Crystal structures of APOBEC3G N-domain alone and its complex with DNA. Nat Commun, 2016. 7: p. 12193.

- Ito, F., et al., Structural basis for HIV-1 antagonism of host APOBEC3G via Cullin E3 ligase. Sci Adv, 2023. 9(1): p. eade3168.

- Qiao, Q., et al., AID Recognizes Structured DNA for Class Switch Recombination. Mol Cell, 2017. 67(3): p. 361-373 e4.

- Bohn, M.F., et al., Crystal structure of the DNA cytosine deaminase APOBEC3F: the catalytically active and HIV-1 Vif-binding domain. Structure, 2013. 21(6): p. 1042-50.

- Ito, F., et al., Understanding the Structure, Multimerization, Subcellular Localization and mC Selectivity of a Genomic Mutator and Anti-HIV Factor APOBEC3H. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 3763.

- Shi, K., et al., Active site plasticity and possible modes of chemical inhibition of the human DNA deaminase APOBEC3B. FASEB Bioadv, 2020. 2(1): p. 49-58.

- Chen, K.M., et al., Structure of the DNA deaminase domain of the HIV-1 restriction factor APOBEC3G. Nature, 2008. 452(7183): p. 116-9.

- Furukawa, A., et al., Structure, interaction and real-time monitoring of the enzymatic reaction of wild-type APOBEC3G. EMBO J, 2009. 28(4): p. 440-51.

- Harjes, E., et al., An extended structure of the APOBEC3G catalytic domain suggests a unique holoenzyme model. J Mol Biol, 2009. 389(5): p. 819-32.

- Shandilya, S.M., et al., Crystal structure of the APOBEC3G catalytic domain reveals potential oligomerization interfaces. Structure, 2010. 18(1): p. 28-38.

- Maiti, A., et al., Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 restriction factor APOBEC3G in complex with ssDNA. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 2460.

- Jumper, J., et al., Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 2021. 596(7873): p. 583-589.

- Varadi, M., et al., AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res, 2022. 50(D1): p. D439-D444.

- Lorenzo, J.P., et al., APOBEC2 is a Transcriptional Repressor required for proper Myoblast Differentiation. bioRxiv, 2021: p. 2020.07.29.223594.

- Tang, C., A. Krantsevich, and T. MacCarthy, Deep learning model of somatic hypermutation reveals importance of sequence context beyond hotspot targeting. iScience, 2022. 25(1): p. 103668.

- Adolph, M.B., R.P. Love, and L. Chelico, Biochemical Basis of APOBEC3 Deoxycytidine Deaminase Activity on Diverse DNA Substrates. ACS Infect Dis, 2018. 4(3): p. 224-238.

- Senavirathne, G., et al., Single-stranded DNA scanning and deamination by APOBEC3G cytidine deaminase at single molecule resolution. J Biol Chem, 2012. 287(19): p. 15826-35.

- Pham, P., et al., Processive AID-catalysed cytosine deamination on single-stranded DNA simulates somatic hypermutation. Nature, 2003. 424(6944): p. 103-7.

- Wong, L., et al., APOBEC1 cytosine deaminase activity on single-stranded DNA is suppressed by replication protein A. Nucleic Acids Res, 2021. 49(1): p. 322-339.

- Adolph, M.B., et al., Cytidine deaminase efficiency of the lentiviral viral restriction factor APOBEC3C correlates with dimerization. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017. 45(6): p. 3378-3394.

- Adolph, M.B., et al., Enzyme cycling contributes to efficient induction of genome mutagenesis by the cytidine deaminase APOBEC3B. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017. 45(20): p. 11925-11940.

- Gorle, S., et al., Computational Model and Dynamics of Monomeric Full-Length APOBEC3G. ACS Cent Sci, 2017. 3(11): p. 1180-1188.

- Ziegler, S.J., et al., Insights into DNA substrate selection by APOBEC3G from structural, biochemical, and functional studies. PLoS One, 2018. 13(3): p. e0195048.

- Mitra, M., et al., Sequence and structural determinants of human APOBEC3H deaminase and anti-HIV-1 activities. Retrovirology, 2015. 12: p. 3.

- Wittkopp, C.J., et al., A Single Nucleotide Polymorphism in Human APOBEC3C Enhances Restriction of Lentiviruses. PLoS Pathog, 2016. 12(10): p. e1005865.

- Silvas, T.V. and C.A. Schiffer, APOBEC3s: DNA-editing human cytidine deaminases. Protein Sci, 2019. 28(9): p. 1552-1566.

- Hix, M.A. and G.A. Cisneros, Computational Investigation of APOBEC3H Substrate Orientation and Selectivity. J Phys Chem B, 2020. 124(19): p. 3903-3908.

- Lu, X., et al., Crystal structure of DNA cytidine deaminase ABOBEC3G catalytic deamination domain suggests a binding mode of full-length enzyme to single-stranded DNA. J Biol Chem, 2015. 290(7): p. 4010-21.

- Kitamura, S., Ode, H., Nakashima, M., Imahashi, M., Naganawa, Y., Ibe, S., Yokomaku, Y., Watanabe, N., Suzuki, A., Sugiura, W., Iwatani, Y., Crystal structure of the human APOBEC3C having HIV-1 Vif-binding interface. 2011.

- Li, Y.L., et al., The structural basis for HIV-1 Vif antagonism of human APOBEC3G. Nature, 2023. 615(7953): p. 728-733.

- Larson, E.T., et al., Structures of substrate- and inhibitor-bound adenosine deaminase from a human malaria parasite show a dramatic conformational change and shed light on drug selectivity. J Mol Biol, 2008. 381(4): p. 975-88.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).