Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

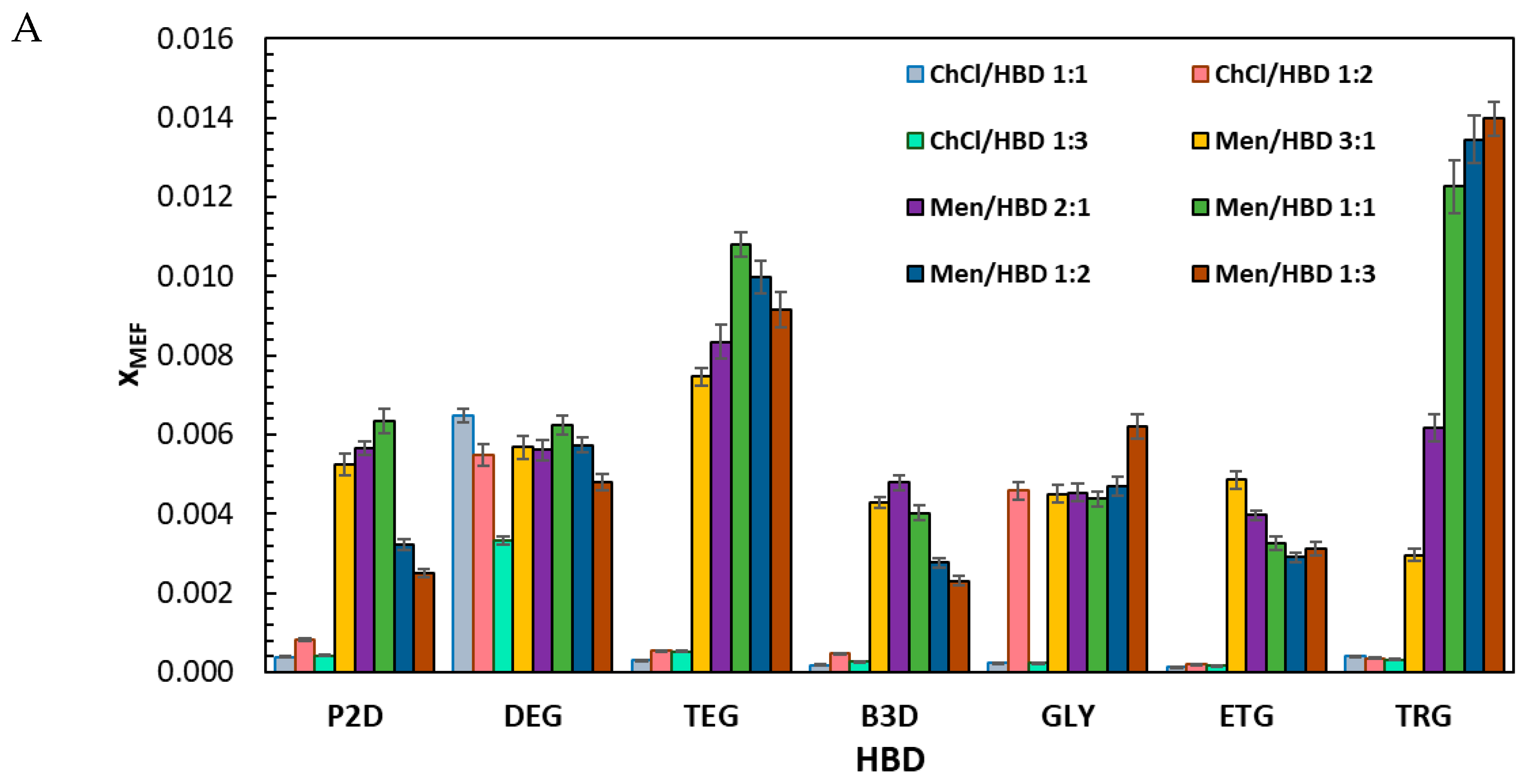

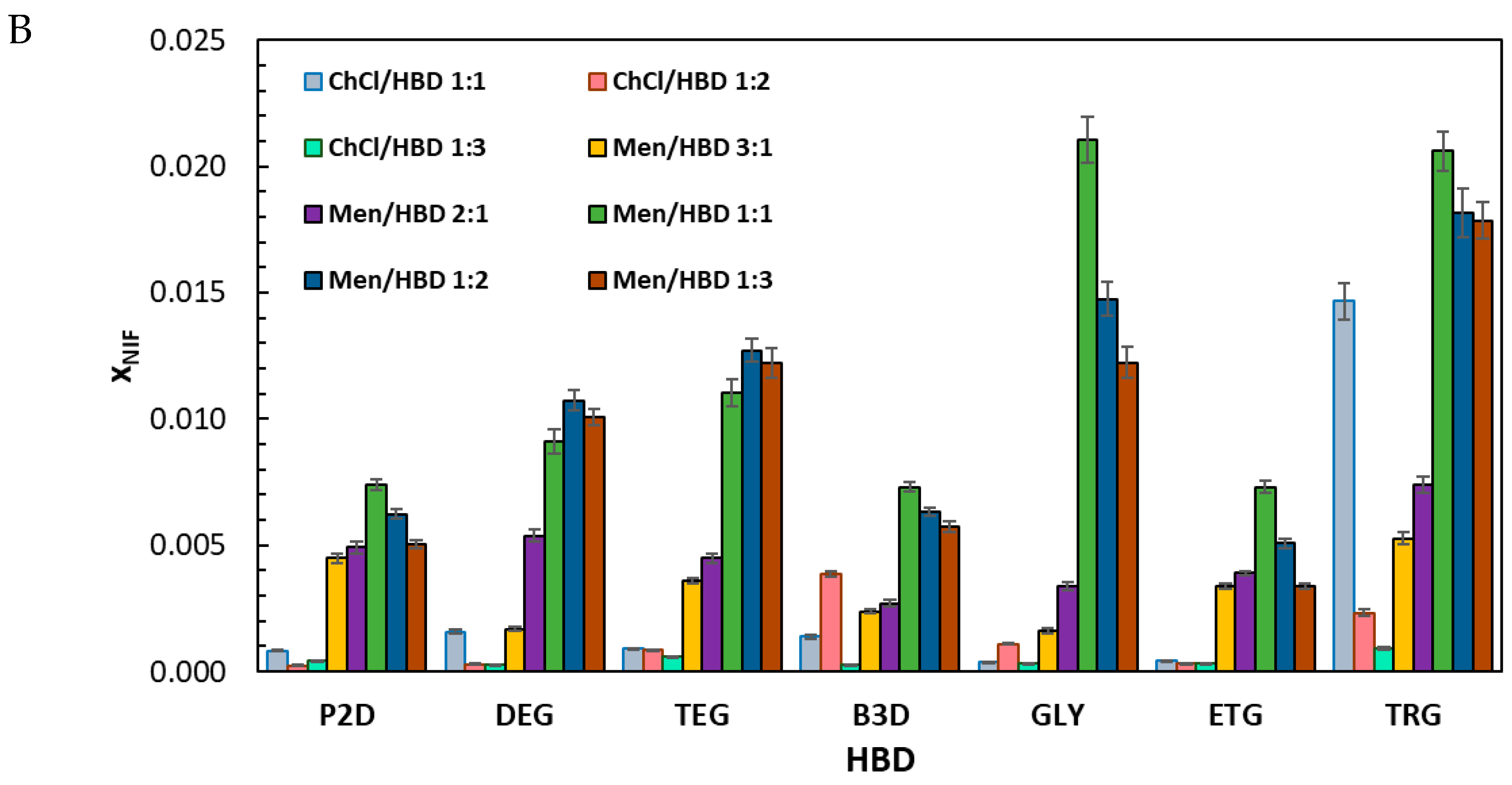

2.1. Solubility Measurements of Mefenamic Acid and Niflumic Acid

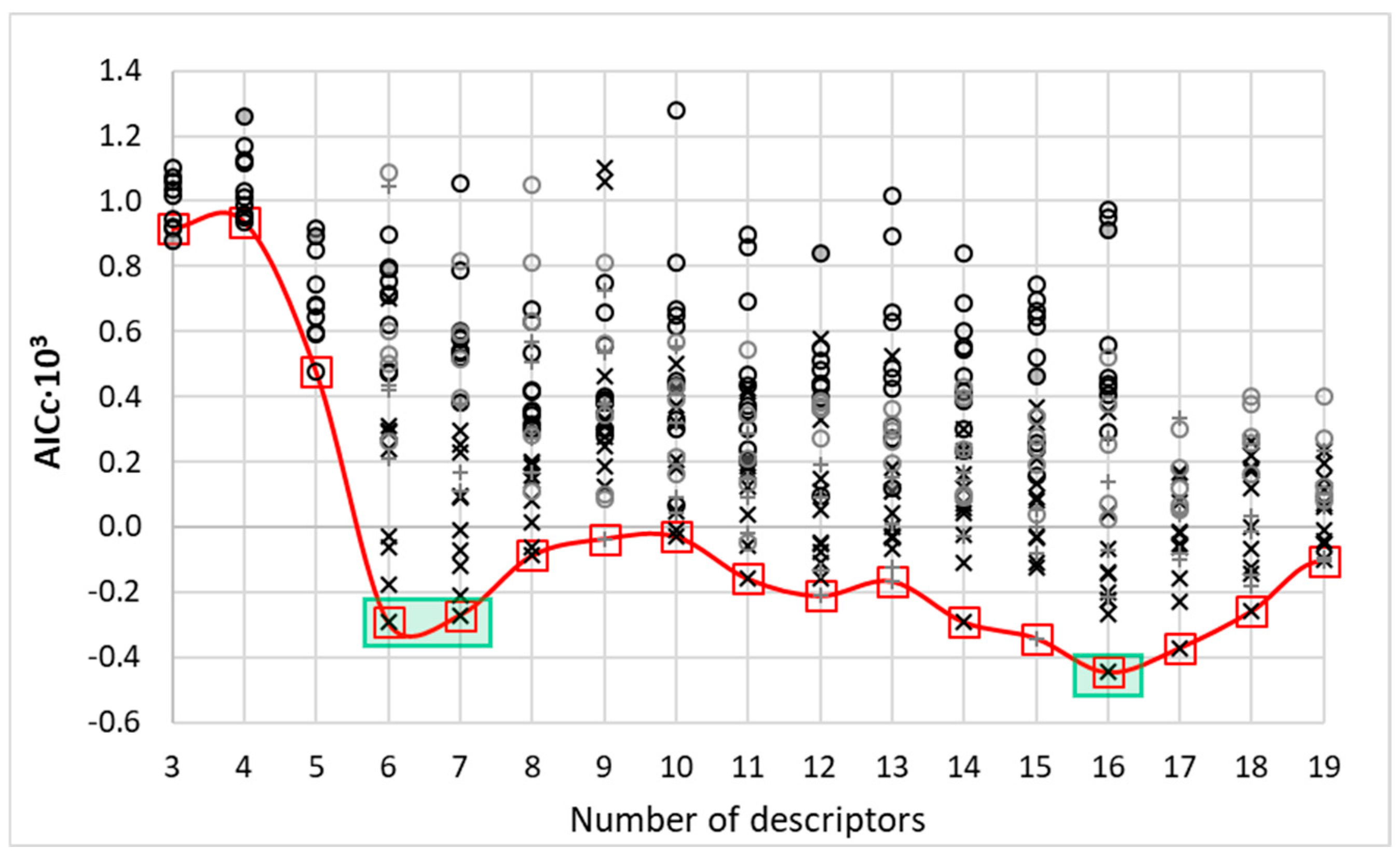

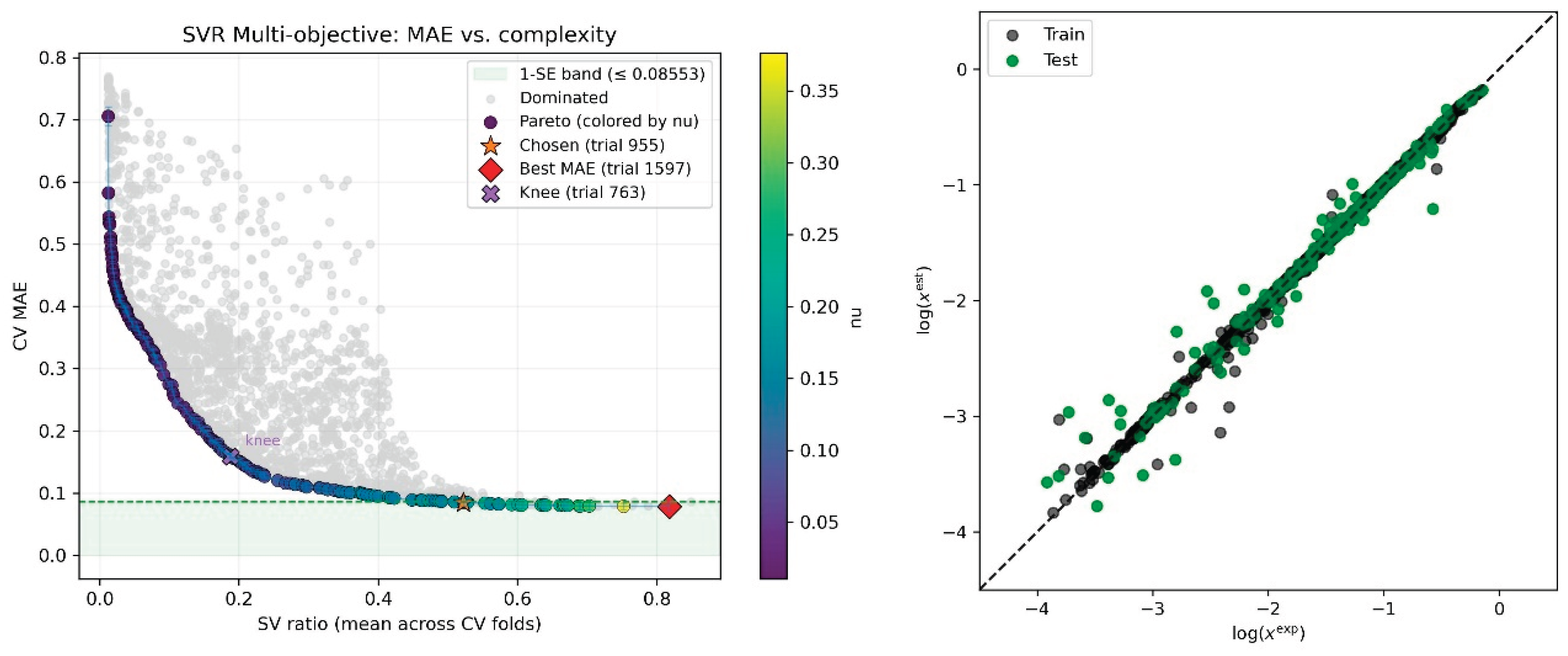

2.2. Identifying an Optimal Predictive Model via the DOO-IT Framework

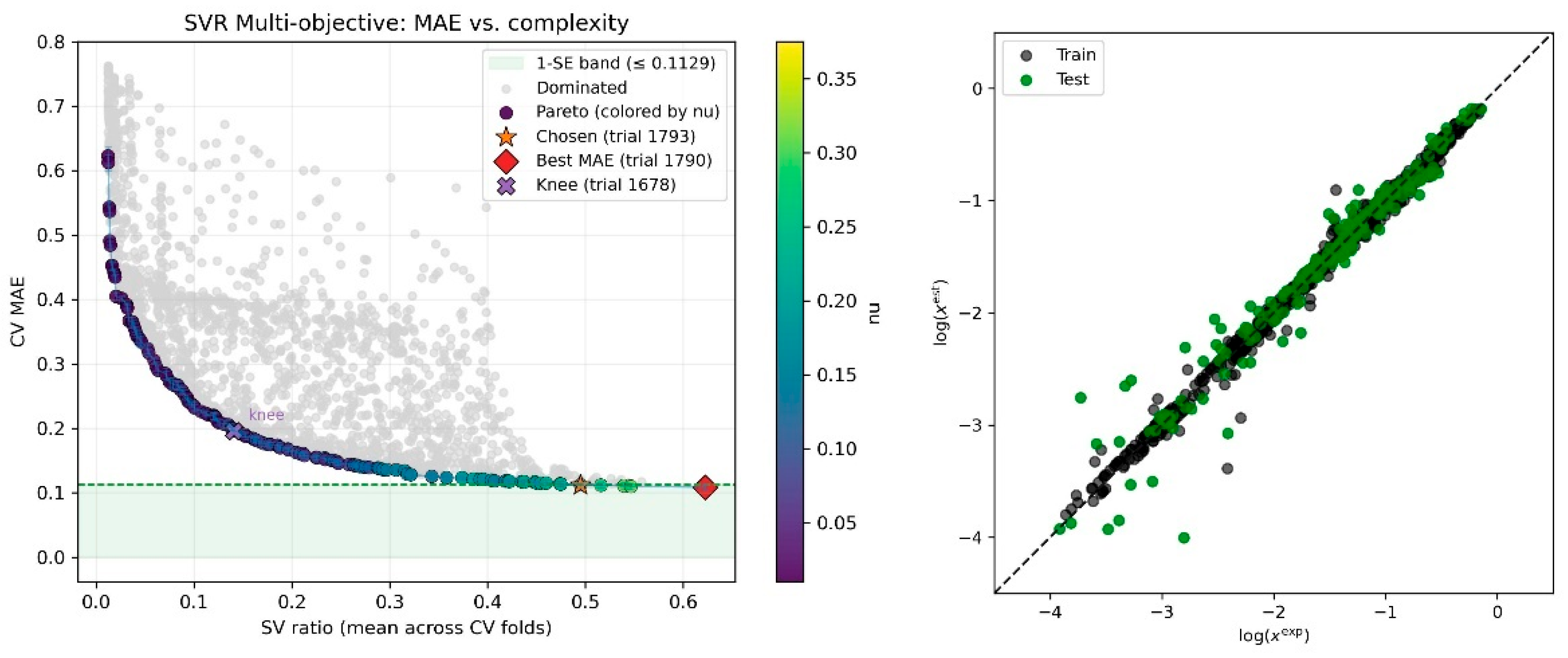

2.3. Performance of the Optimal Solubility Models

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Solubility Measurements Procedure

3.3. COSMO-RS Computations

3.4. Molecular Descriptors

3.5. Dataset

3.6. Machine Learning Protocol

3.6.1. Core Algorithm and Data Preprocessing

3.6.2. Dual-Objective Optimization Protocol

3.6.3. Iterative Model Refinement and Candidate Selection

3.6.4. Final Model Selection via Information Criterion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lamberth, C.; Dinges, J. Different Roles of Carboxylic Functions in Pharmaceuticals and Agrochemicals. Bioact. Carboxylic Compd. Classes Pharm. Agrochem. 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bharate, S.S. Carboxylic Acid Counterions in FDA-Approved Pharmaceutical Salts. Pharm. Res. 2021, 38, 1307–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagby, M.O.; Johnson, R.W.; Daniels, R.W.; Contrell, R.R.; Sauer, E.T.; Keenan, M.J.; Krevalis, M.A.; Staff, U.B. Carboxylic Acids. Kirk-Othmer Encycl. Chem. Technol. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ballatore, C.; Huryn, D.M.; Smith, A.B. Carboxylic Acid (Bio)Isosteres in Drug Design. ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Goel, N. Phenolic acids: Natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnol. Reports 2019, 24, e00370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfeen, M.; Srivastava, A.; Srivastava, N.; Khan, R.A.; Almahmoud, S.A.; Mohammed, H.A. Design, classification, and adverse effects of NSAIDs: A review on recent advancements. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2024, 112, 117899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, N.K.; Prince Sabina, E. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): A current insight into its molecular mechanism eliciting organ toxicities. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 172, 113598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimolai, N. The potential and promise of mefenamic acid. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 6, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, H.; Daud, S.; Sheraz, S.; Bibi, M.; Ahmad, T.; Sardar, A.; Fazal, T.; Khan, A.; Abid, O. ur R. The Chemistry and Bioactivity of Mefenamic Acid Derivatives: A Review of Recent Advances. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim). 2025, 358, e70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, B.N.; Tartifizadeh, A.; Khabnadideh, S. Comparison of fennel and mefenamic acid for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2003, 80, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderas, E.; Ateaga-Tlecuitl, R.; Rivera, M.; Gomora, J.C.; Darszon, A. Niflumic acid blocks native and recombinant T-type channels. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012, 227, 2542–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Inoue, H.; Fukuyama, S.; Matsumoto, K.; Matsumura, M.; Tsuda, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Aizawa, H.; Nakanishi, Y. Niflumic Acid Suppresses Interleukin-13–induced Asthma Phenotypes. 2012; 173, 1216–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbari, M.A.; El-Gazar, A.A.; Abdelbary, A.A.; Elshafeey, A.H.; Mosallam, S. Investigating the potential of novasomes in improving the trans-tympanic delivery of niflumic acid for effective treatment of acute otitis media. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 98, 105912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.; Schrimpl, L.; Schmidt, P.C. Some Physicochemical Properties of Mefenamic Acid. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2000, 26, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takács-Novák, K.; Szoke, V.; Völgyi, G.; Horváth, P.; Ambrus, R.; Szabó-Révész, P. Biorelevant solubility of poorly soluble drugs: Rivaroxaban, furosemide, papaverine and niflumic acid. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2013, 83, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Baloch, M.K.; Ullah, I.; Mustaqeem, M. Enhancement in aqueous solubility of Mefenamic acid using micellar solutions of various surfactants. J. Solution Chem. 2014, 43, 1360–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinamard, R.; Simard, C.; Del Negro, C. Flufenamic acid as an ion channel modulator. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhavan, M.; Hwang, G.C.C. Design and evaluation of transdermal flufenamic acid delivery system. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 1992, 18, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Li, K.; Yan, Q.; Koizumi, S.; Shi, L.; Takahashi, S.; Zhu, Y.; Matsue, H.; Takeda, M.; Kitamura, M.; et al. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Flufenamic Acid Is a Potent Activator of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 339, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, V.S.; Bertone, A.L. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Vet. Clin. North Am. - Equine Pract. 2002, 18, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vane, J.R.; Botting, R.M. Mechanism of Action of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. Am. J. Med. 1998, 104, 2S–8S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, A.M.; Girgis, A.S.; Kariuki, B.M.; Samir, N.; Said, M.F.; Abdelnaser, A.; Nasr, S.; Bekheit, M.S.; Abdelhameed, M.F.; Almalki, A.J.; et al. Design and synthesis of ibuprofen-quinoline conjugates as potential anti-inflammatory and analgesic drug candidates. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 119, 105557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleškić Kapo, S.; Rakanović-Todić, M.; Burnazović-Ristić, L.; Kusturica, J.; Kulo Ćesić, A.; Ademović, E.; Loga-Zec, S.; Sarač-Hadžihalilović, A.; Aganović-Mušinović, I. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of diclofenac and ketoprofen patches in two different rat models of acute inflammation. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 2023, 35, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yan, Y. Evaluation of the binding interactions of p-acetylaminophenol, aspirin, ibuprofen and aminopyrine with norfloxacin from the view of antipyretic and anti-inflammatory. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 312, 113397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, C.; Mujica, P.; Illanes-González, J.; López, A.; Vargas, C.; Sáez, J.C.; González-Jamett, A.; Ardiles, Á.O. Probenecid, an Old Drug with Potential New Uses for Central Nervous System Disorders and Neuroinflammation. Biomed. 2023, 11, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, N.; Koch, S.E.; Tranter, M.; Rubinstein, J. The history and future of probenecid. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2012, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, R.J. Phenolic acids in foods: An overview of analytical methodology. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2866–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jitan, S.; Alkhoori, S.A.; Yousef, L.F. Phenolic Acids From Plants: Extraction and Application to Human Health. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2018, 58, 389–417. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Huang, R. Ferulic acid: An extraordinarily neuroprotective phenolic acid with anti-depressive properties. Phytomedicine 2022, 105, 154355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.A.; Saifi, M.A.; Pulivendala, G.; Godugu, C.; Talla, V. Ferulic acid ameliorates the progression of pulmonary fibrosis via inhibition of TGF-β/smad signalling. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 149, 111980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, Z.; Cisowski, W. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging, antioxidant and anti-radical activity of some phenolic acids. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2003, 41, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Maalik, A.; Murtaza, G. Inhibitory mechanism against oxidative stress of caffeic acid. J. Food Drug Anal. 2016, 24, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizmarova, B.; Hubkova, B.; Bolerazska, B.; Marekova, M.; Birkova, A. Caffeic acid: a brief overview of its presence, metabolism, and bioactivity. Bioact. Compd. Heal. Dis. - Online ISSN 2574-0334; Print ISSN 2769-2426 2020, 3, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasulu, C.; Ramgopal, M.; Ramanjaneyulu, G.; Anuradha, C.M.; Suresh Kumar, C. Syringic acid (SA) ‒ A Review of Its Occurrence, Biosynthesis, Pharmacological and Industrial Importance. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogut, E.; Armagan, K.; Gül, Z. The role of syringic acid as a neuroprotective agent for neurodegenerative disorders and future expectations. Metab. Brain Dis. 2022, 37, 859–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimsa, S.; Mondal, S.; Mini, S. Syringic acid: A promising phenolic phytochemical with extensive therapeutic applications. R&D Funct. Food Prod. 2024, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Boz, H. p-Coumaric acid in cereals: presence, antioxidant and antimicrobial effects. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 2323–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, K.; Ou, J.; Huang, J.; Ou, S. p-Coumaric acid and its conjugates: dietary sources, pharmacokinetic properties and biological activities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 2952–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savjani, K.T.; Gajjar, A.K.; Savjani, J.K. Drug solubility: importance and enhancement techniques. ISRN Pharm. 2012, 2012, 195727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, F.; Jouyban, A.; Acree, W.E. Pharmaceuticals solubility is still nowadays widely studied everywhere. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 23, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Patel, N.; Lin, S. Solubility and dissolution enhancement strategies: current understanding and recent trends. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2015, 41, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Malik, M.Y.; Singh, S.K.; Chaturvedi, S.; Gayen, J.R.; Wahajuddin, M. Bioavailability Enhancement of Poorly Soluble Drugs: The Holy Grail in Pharma Industry. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 987–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattachar, S.N.; Deschenes, L.A.; Wesley, J.A. Solubility: it’s not just for physical chemists. Drug Discov. Today 2006, 11, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltescu, A.R.; Butnariu, M.; Sarac, I. The importance of solubility for new drug molecules. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2020, 13, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, K.; Shah, H.S.; Nahar, K.; Dave, R.; Morris, K.R. Contribution of Crystal Lattice Energy on the Dissolution Behavior of Eutectic Solid Dispersions. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 9690–9701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Censi, R.; Di Martino, P. Polymorph Impact on the Bioavailability and Stability of Poorly Soluble Drugs. Molecules 2015, 20, 18759–18776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, K.; Knapik-Kowalczuk, J.; Paluch, M. How does the high pressure affects the solubility of the drug within the polymer matrix in solid dispersion systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 143, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Bedi, N.; Tiwary, A.K. Enhancing solubility of poorly aqueous soluble drugs: critical appraisal of techniques. J. Pharm. Investig. 2018, 48, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesha, B.S.; Sheeba, F.R.; Deepak, H.K. A comprehensive review of green approaches to drug solubility enhancement. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2025, 51, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; Poe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Klein, J.M.; Horton, A.; Adhikari, L.; Zelovich, T.; Doherty, B.W.; et al. Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review of Fundamentals and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Achkar, T.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Fourmentin, S. Basics and properties of deep eutectic solvents: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3397–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.; Craveiro, R.; Aroso, I.; Martins, M.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents – Solvents for the 21st Century. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Friesen, J.B.; McAlpine, J.B.; Lankin, D.C.; Chen, S.N.; Pauli, G.F. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: Properties, Applications, and Perspectives. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, K.A.; Sadeghi, R. Physicochemical properties of deep eutectic solvents: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 360, 119524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, S.; Shayanfar, A. Deep eutectic solvents for pharmaceutical formulation and drug delivery applications. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2020, 25, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.A.; Chavda, V.; Hirpara, D.; Sharma, V.S.; Shrivastav, P.S.; Kumar, S. Exploring the potential of deep eutectic solvents in pharmaceuticals: Challenges and opportunities. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 390, 123171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantri, S.; Vora, A. Eutectic solutions for healing: a comprehensive review on therapeutic deep eutectic solvents (TheDES). Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2024, 50, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelquader, M.M.; Li, S.; Andrews, G.P.; Jones, D.S. Therapeutic deep eutectic solvents: A comprehensive review of their thermodynamics, microstructure and drug delivery applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2023, 186, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raevsky, O.A.; Grigorev, V.Y.; Polianczyk, D.E.; Raevskaja, O.E.; Dearden, J.C. Aqueous Drug Solubility: What Do We Measure, Calculate and QSPR Predict? Mini-Reviews Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowles, D.J.; Connaughton, B.J.; Carter, J.W.; Mitchell, J.B.O.; Palmer, D.S. Physics-Based Solubility Prediction for Organic Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boobier, S.; Hose, D.R.J.; Blacker, A.J.; Nguyen, B.N. Machine learning with physicochemical relationships: solubility prediction in organic solvents and water. Nat. Commun. 2020 111 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanavati, M.A.; Ahmadi, S.; Rohani, S. A machine learning approach for the prediction of aqueous solubility of pharmaceuticals: a comparative model and dataset analysis. Digit. Discov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. chen; Feng, J. wen Development and Application of Artificial Neural Network. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2018, 102, 1645–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panapitiya, G.; Girard, M.; Hollas, A.; Sepulveda, J.; Murugesan, V.; Wang, W.; Saldanha, E. Evaluation of Deep Learning Architectures for Aqueous Solubility Prediction. ACS Omega 2022, 28, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corso, G.; Stark, H.; Jegelka, S.; Jaakkola, T.; Barzilay, R. Graph neural networks. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2024, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Designing solvent systems using self-evolving solubility databases and graph neural networks - Chemical Science (RSC Publishing). Available online: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2023/sc/d3sc03468b (accessed on 23 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tosca, E.M.; Bartolucci, R.; Magni, P. Application of artificial neural networks to predict the intrinsic solubility of drug-like molecules. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Di, J.; Wang, D.; Dai, X.; Hua, Y.; Gao, X.; Zheng, A.; Gao, J. State-of-the-Art Review of Artificial Neural Networks to Predict, Characterize and Optimize Pharmaceutical Formulation. Pharm. 2022, 14, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cysewski, P.; Jeliński, T.; Kukwa, O.; Przybyłek, M. From Molecular Interactions to Solubility in Deep Eutectic Solvents: Exploring Flufenamic Acid in Choline-Chloride- and Menthol-Based Systems. Molecules 2025, 30, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, A. Conductor-like screening model for real solvents: A new approach to the quantitative calculation of solvation phenomena. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 2224–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, A. COSMO-RS: From quantum chemistry to fluid phase thermodynamics and drug design; 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; ISBN 9780444519948. [Google Scholar]

- Klamt, A.; Eckert, F.; Hornig, M.; Beck, M.E.; Bürger, T. Prediction of aqueous solubility of drugs and pesticides with COSMO-RS. J. Comput. Chem. 2002, 23, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, A.; Eckert, F.; Arlt, W. COSMO-RS: An alternative to simulation for calculating thermodynamic properties of liquid mixtures. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2010, 1, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassault Systèmes. COSMOtherm, Version 24.0.0; BIOVIA: San Diego, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jeliński, T.; Przybyłek, M.; Różalski, R.; Romanek, K.; Wielewski, D.; Cysewski, P. Tuning Ferulic Acid Solubility in Choline-Chloride- and Betaine-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: Experimental Determination and Machine Learning Modeling. Molecules 2024, 29, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cysewski, P.; Jeliński, T.; Przybyłek, M.; Mai, A.; Kułak, J. Experimental and Machine-Learning-Assisted Design of Pharmaceutically Acceptable Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Solubility Improvement of Non-Selective COX Inhibitors Ibuprofen and Ketoprofen. Molecules 2024, 29, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cysewski, P.; Jeliński, T.; Przybyłek, M. Exploration of the Solubility Hyperspace of Selected Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients in Choline- and Betaine-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: Machine Learning Modeling and Experimental Validation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeliński, T.; Przybyłek, M.; Różalski, R.; Romanek, K.; Wielewski, D.; Cysewski, P. Tuning Ferulic Acid Solubility in Choline-Chloride- and Betaine-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: Experimental Determination and Machine Learning Modeling. Molecules 2024, 29, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cysewski, P.; Jeliński, T.; Przybyłek, M.; Mai, A.; Kułak, J. Experimental and Machine-Learning-Assisted Design of Pharmaceutically Acceptable Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Solubility Improvement of Non-Selective COX Inhibitors Ibuprofen and Ketoprofen. Molecules 2024, 29, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cysewski, P.; Jeliński, T.; Przybyłek, M. Exploration of the Solubility Hyperspace of Selected Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients in Choline- and Betaine-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: Machine Learning Modeling and Experimental Validation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COSMOtherm, version 24.0.0, Dassault Systèmes, Biovia: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022.

- Klamt, A.; Eckert, F.; Arlt, W. COSMO-RS: An Alternative to Simulation for Calculating Thermodynamic Properties of Liquid Mixtures. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2010, 1, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, A. COSMO-RS: From quantum chemistry to fluid phase thermodynamics and drug design; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; ISBN 9780444519948. [Google Scholar]

- Klamt, A. Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents: A New Approach to the Quantitative Calculation of Solvation Phenomena. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 2224–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, A.; Eckert, F.; Hornig, M.; Beck, M.E.; Bürger, T. Prediction of aqueous solubility of drugs and pesticides with COSMO-RS. J. Comput. Chem. 2002, 23, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordova, I.W.; Teixeira, G.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J.A.; Abranches, D.O.; Pinho, S.P.; Ferreira, O.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Using Molecular Conformers in COSMO-RS to Predict Drug Solubility in Mixed Solvents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 9565–9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, S.M.; Abranches, D.O.; Crespo, E.A.; Ferreira, O.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Pinho, S.P. Experimental solubility and density studies on aqueous solutions of quaternary ammonium halides, and thermodynamic modelling for melting enthalpy estimations. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 300, 112281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, M.G.; Carvalho, P.J.; Santos, L.M.N.B.F.; Gomes, L.R.; Marrucho, I.M.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Solubility of water in fluorocarbons: Experimental and COSMO-RS prediction results. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2010, 42, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.B.; Chen, D.-L.; Luebke, D.R.; Johnson, J.K.; Enick, R.M. Critical Assessment of CO 2 Solubility in Volatile Solvents at 298.15 K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2011, 56, 1565–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acree, W.; Chickos, J.S. Phase Transition Enthalpy Measurements of Organic and Organometallic Compounds. Sublimation, Vaporization and Fusion Enthalpies From 1880 to 2010. 2010.

- Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A.J.; Williamson, R.C.; Bartlett, P.L. New support vector algorithms. Neural Comput. 2000, 12, 1207–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.J.; Panaye, A.; Doucet, J.P.; Zhang, R.S.; Chen, H.F.; Liu, M.C.; Hu, Z.D.; Fan, B.T. Comparative study of QSAR/QSPR correlations using support vector machines, radial basis function neural networks, and multiple linear regression. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Support vector regression-based QSAR models for prediction of antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkasov, A.; Muratov, E.N.; Fourches, D.; Varnek, A.; Baskin, I.I.; Cronin, M.; Dearden, J.; Gramatica, P.; Martin, Y.C.; Todeschini, R.; et al. QSAR modeling: Where have you been? Where are you going to? J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4977–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretton, A.; Borgwardt, K.M.; Rasch, M.J.; Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A. A kernel two-sample test. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 723–773. [Google Scholar]

- Muandet, K.; Fukumizu, K.; Sriperumbudur, B.; Schölkopf, B. Kernel mean embedding of distributions: A review and beyond. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2017, 10, 1–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- scikit-learn Developers. StandardScaler—scikit-learn 1.7.2 Documentation. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.preprocessing.StandardScaler.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- scikit-learn Developers. 7.3.1. Standardization, or Mean Removal and Variance Scaling—scikit-learn User Guide. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/preprocessing.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Optuna Developers. Multi-Objective Optimization with Optuna—Optuna Documentation (stable). Available online: https://optuna.readthedocs.io/en/stable/tutorial/20_recipes/002_multi_objective.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Yanase, T. Announcing Optuna 3.2. Optuna Blog (Medium). Available online: https://medium.com/optuna/announcing-optuna-3-2-cfbfbe104d5f (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.H.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and regression trees; Routledge, 2017; ISBN 9781351460491. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, N. Further analysis of the data by Akaike’s information criterion and the finite corrections. Commun. Stat. - Theory Methods 1978, 7, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvich, C.M.; Tsai, C.-L. Regression and Time Series Model Selection in Small Samples. Biometrika 1989, 76, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portet, S. A primer on model selection using the Akaike Information Criterion. Infect. Dis. Model. 2020, 5, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Python Software Foundation. Python 3.10 Documentation. Available online: https://docs.python.org/3.10/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. Available online: https://www.jmlr.org/papers/v12/pedregosa11a.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- pandas Development Team. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas, Version 2.3.0; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).