1. Background

Stiff Person Syndrome (SPS) is a rare autoimmune-mediated neurological disorder most commonly associated with antibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase (anti-GAD). Its estimated prevalence is approximately 1–2 per million individuals, typically affecting adults between 20 and 50 years of age [

1].

Clinically, anti-GAD SPS is characterised by progressive muscle rigidity and painful spasms, predominantly involving the trunk and lower limbs. These symptoms often fluctuate and are exacerbated by emotional or sensory stimuli. Additional features may include hyperlordosis, impaired gait, and psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression. The condition is progressive and can lead to severe functional disability [

2].

Diagnosis is based primarily on clinical presentation and is supported by findings from electromyography, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, anti-GAD antibody seropositivity, and the clinical response to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-enhancing agents such as benzodiazepines. Patients may be classified as fulfilling criteria for definite or probable SPS [

3,

4]. The condition is also associated with specific genetic markers (e.g., HLA-DQB1 and DRB1 alleles) and frequently coexists with other autoimmune disorders, including type 1 diabetes, thyroiditis, coeliac disease, pernicious anaemia, and myasthenia gravis [

4].

Although oculomotor dysfunction has been described in SPS, it remains significantly under-recognised and underdiagnosed [

5,

6]. Given the central nervous system involvement in SPS—particularly affecting brainstem and cerebellar pathways crucial for eye movement control—neuro-ophthalmological examination has considerable potential as a non-invasive, sensitive marker of disease activity [

7].

The aim of this paper is to present an illustrative case series of oculomotor abnormalities in anti-GAD–associated SPS with videonystagmographic documentation to expand the clinical spectrum of this disorder. In doing so, we seek to enhance clinical recognition of the neuro-ophthalmological features of anti-GAD SPS and to support earlier, more accurate diagnosis of this disabling condition, with the ultimate goal of improving diagnostic strategies and patient management.

2. Case Presentation 1

History. A 40-year-old man presented with a two-year history of progressive neuromuscular symptoms, including intolerance to physical activity and sensory stimuli that provoked episodic painful muscle cramps and fatigue. These symptoms most prominently affected the facial region, abdominal musculature, and lower limbs.

Clinical findings. Neurological examination revealed asymmetric blepharospasm and transient right-sided ptosis, both consistently elicited during oculomotor testing, particularly with upward gaze. No nystagmus or signs of bulbar involvement were observed. During assessment of facial muscle innervation, repeated movements (such as smiling or baring the teeth) elicited bradykinesia and a progressive reduction in movement amplitude. Examination of the limbs demonstrated normal muscle tone and no evidence of paresis. Pyramidal signs were present, including bilateral Babinski responses and hyperreflexia in the lower limbs. Bradykinesia was again observed during repetitive motor tasks, including finger tapping and facial movements. Psychological assessment identified comorbid anxiety and depression.

Diagnosis. Extensive diagnostic evaluation—including serological testing, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, electrophysiological studies, and neuroimaging—was performed. Brain and spinal imaging were unremarkable. Needle electromyography demonstrated continuous spontaneous motor unit activity potentials. Paraneoplastic screening was negative. Elevated anti-GAD antibody index was detected by ELISA (antibody index 25.0; reference range 0.00–1.00). Based on these findings, together with the clinical features, a diagnosis of definite anti-GAD–associated SPS was established.

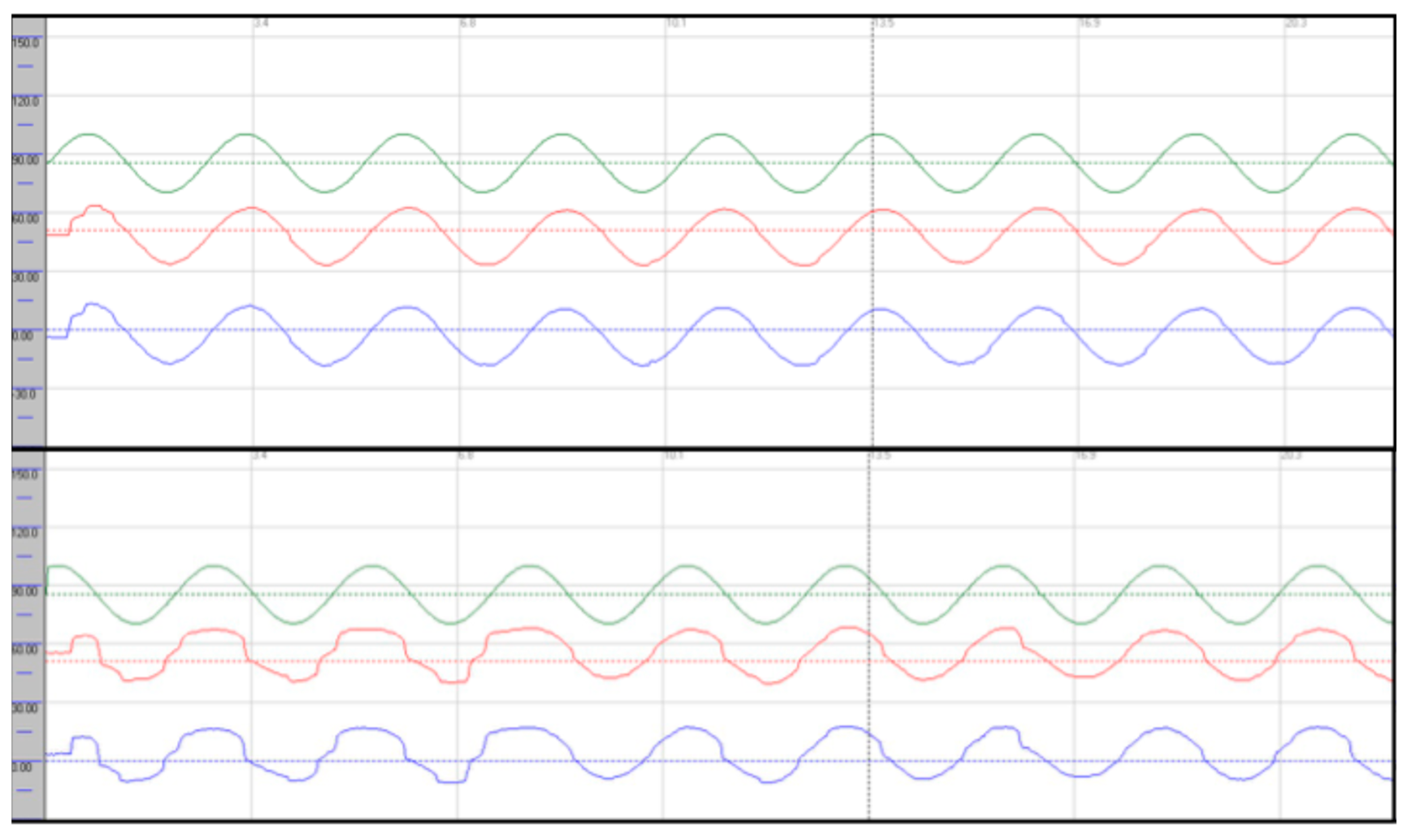

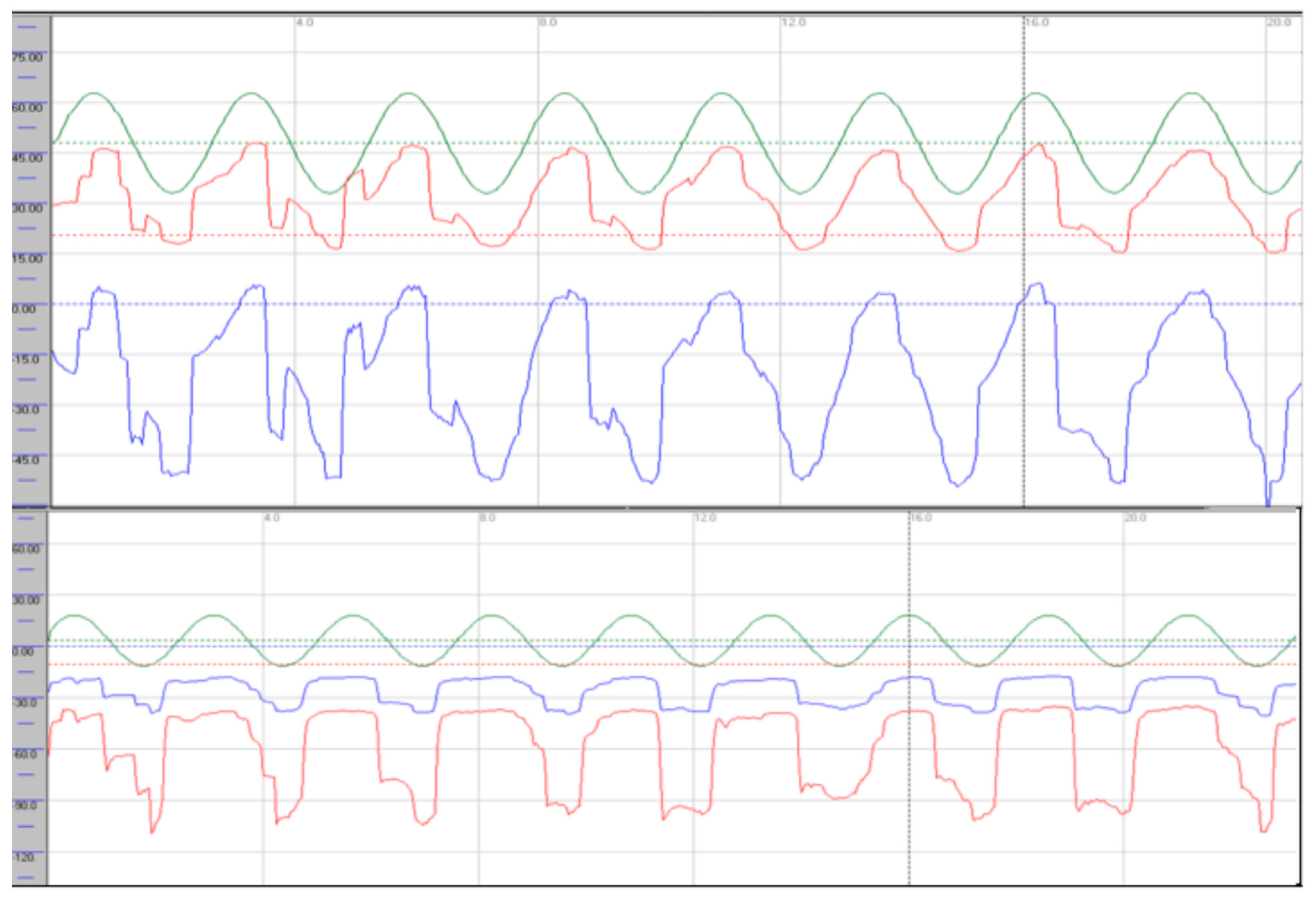

Oculomotor assessment and videonystagmography. Oculomotor testing was performed using videonystagmography (SYNAPSYS VNG Ulmer) with both monocular and binocular infrared cameras. Primary gaze was stable in all directions, with no evidence of spontaneous or gaze-evoked nystagmus, and without saccadic intrusions. Smooth pursuit was mildly impaired, particularly in the vertical plane, with reduced average values most evident in downward tracking (see

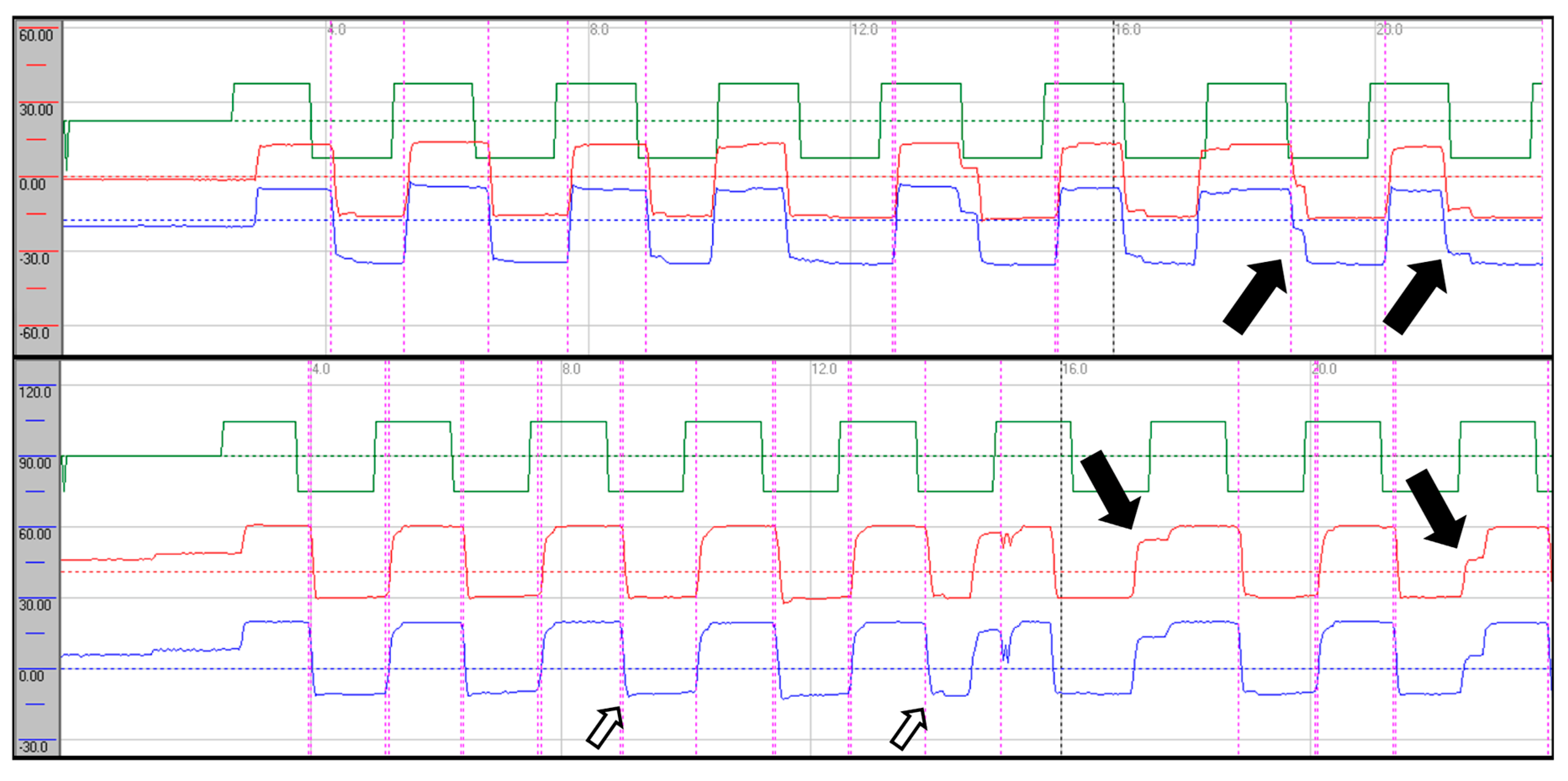

Figure 1). Evaluation of saccadic eye movements demonstrated prolonged latencies in all directions. Repetitive stimulation led to the occurrence of saccadic hypometria, and slight hypermetria of downward saccades was also observed (see

Figure 2). During gaze-evoked testing, upward gaze consistently provoked asymmetric blepharospasm and transient right-sided ptosis, accompanied by delayed relaxation of the orbicularis oculi muscles during eye closure and reopening (

Supplementary video 1).

Treatment. The patient was commenced on immunomodulatory therapy consisting of five sessions of plasmapheresis (5,000 ml per session). Adjunctive treatment with muscle relaxants, physiotherapy, and neuropsychological intervention was initiated. This combination yielded clinical improvement.

Follow-up VNG showed stable smooth pursuit in the horizontal plane with predominant vertical dysfunction; there was no improvement in gain values in any direction, and vertical pursuit was slightly more impaired, particularly during downward tracking. Upward gaze continued to provoke blepharospasm-like eyelid phenomena (Supplementary Video 1). Saccadic latencies were unchanged, hypometria with repetitive stimulation was no longer observed, and vertical saccades continued to exhibit dysmetria as previously described. The eyelid phenomena persisted. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

3. Case Presentation 2

History. A 44-year-old woman presented with a four-month history of progressive cramps and muscle spasms, predominantly affecting the lower limbs. These episodes were triggered by emotional stimuli, postural changes, and sensory inputs such as tactile sensations and sounds. Between episodes, she developed increasing muscle stiffness that eventually rendered her immobile.

Clinical findings. Cranial nerve assessment revealed subtle smooth pursuit abnormalities, saccadic dysfunction, and saccadic intrusions. There was no evidence of facial nerve or bulbar involvement. Examination of the limbs showed hypertonia in all extremities with heightened reflexes and positive pyramidal signs in the lower limbs. Gait was severely impaired, displaying a spastic and occasionally magnetic pattern, with muscle spasms in the lower limbs triggered by sensory stimuli. Psychological assessment demonstrated severe anxiety and reactive depression.

Diagnosis. Extensive diagnostic evaluation, including serological testing, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, electrophysiological studies, and neuroimaging, was undertaken. Brain and spinal imaging were unremarkable. Nerve conduction studies were normal. Needle electromyography demonstrated continuous spontaneous motor unit activity potentials. Paraneoplastic screening was negative. Elevated anti-GAD antibody index was detected by ELISA (antibody index >400.0; reference range 0.00–1.00). Based on these findings, together with the clinical features, a diagnosis of definite anti-GAD–associated SPS was established.

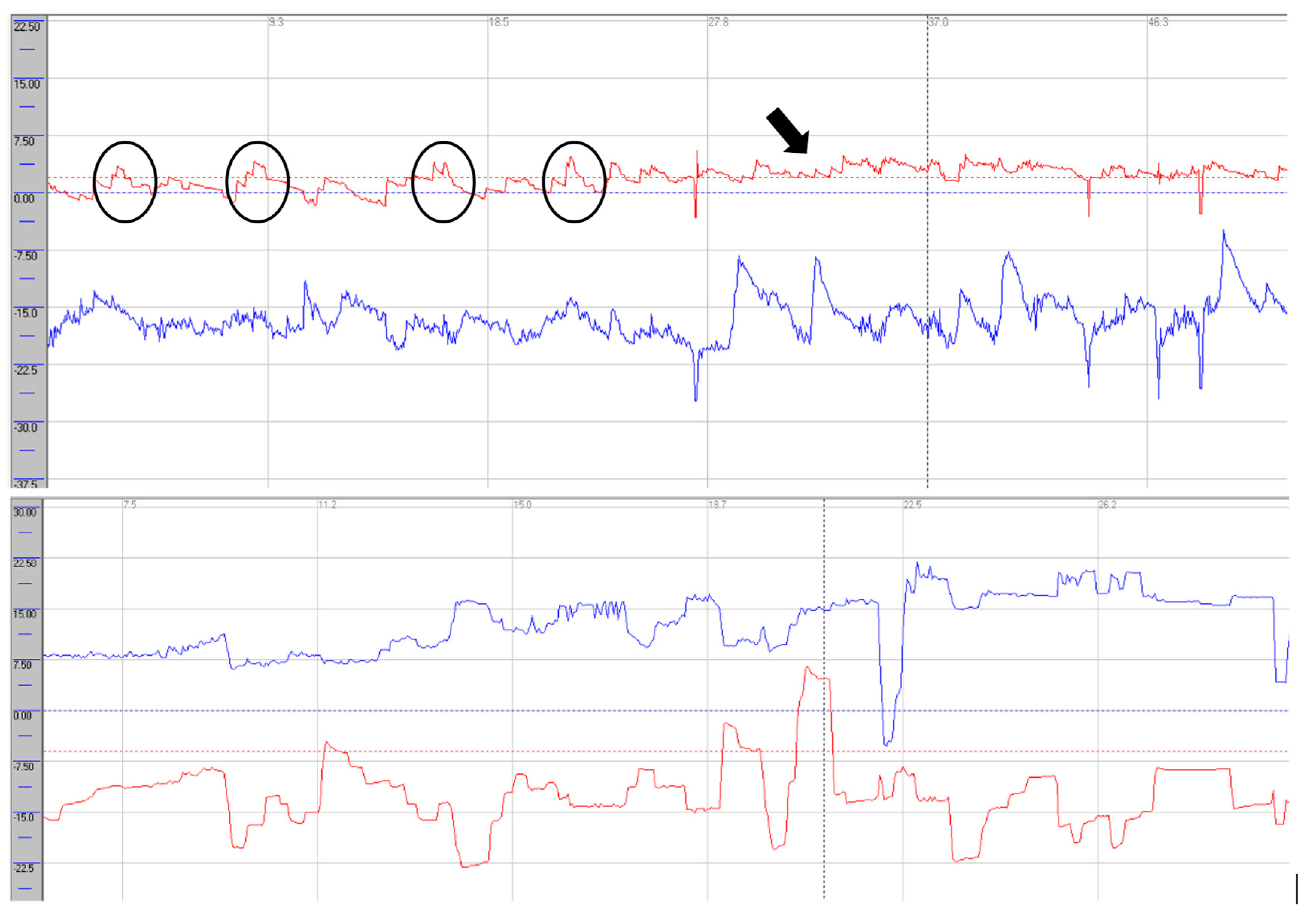

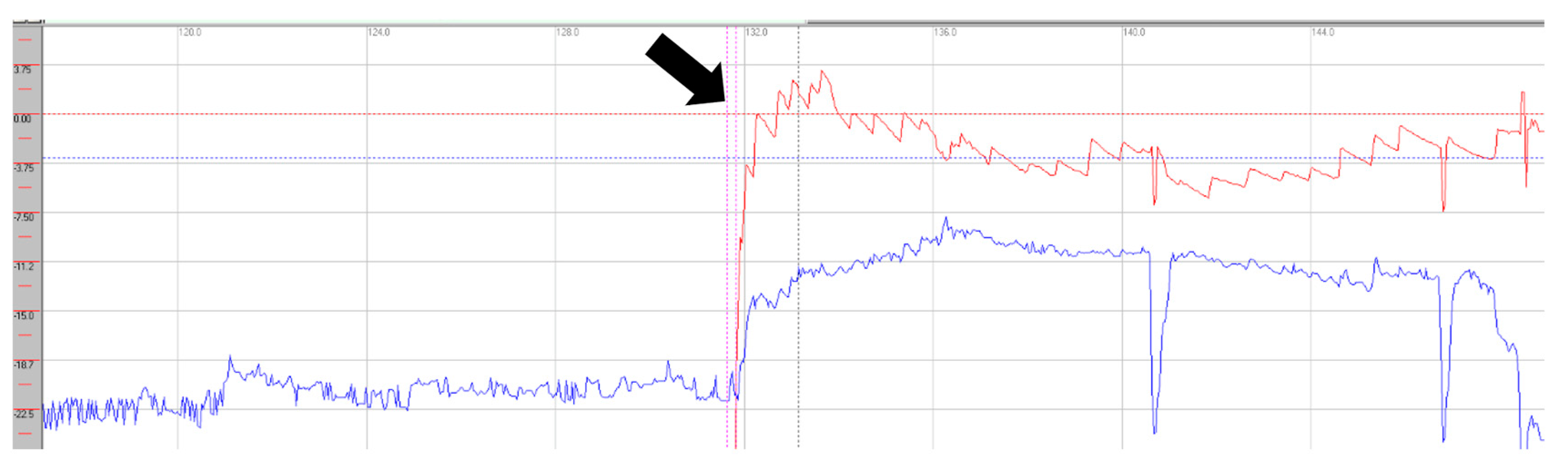

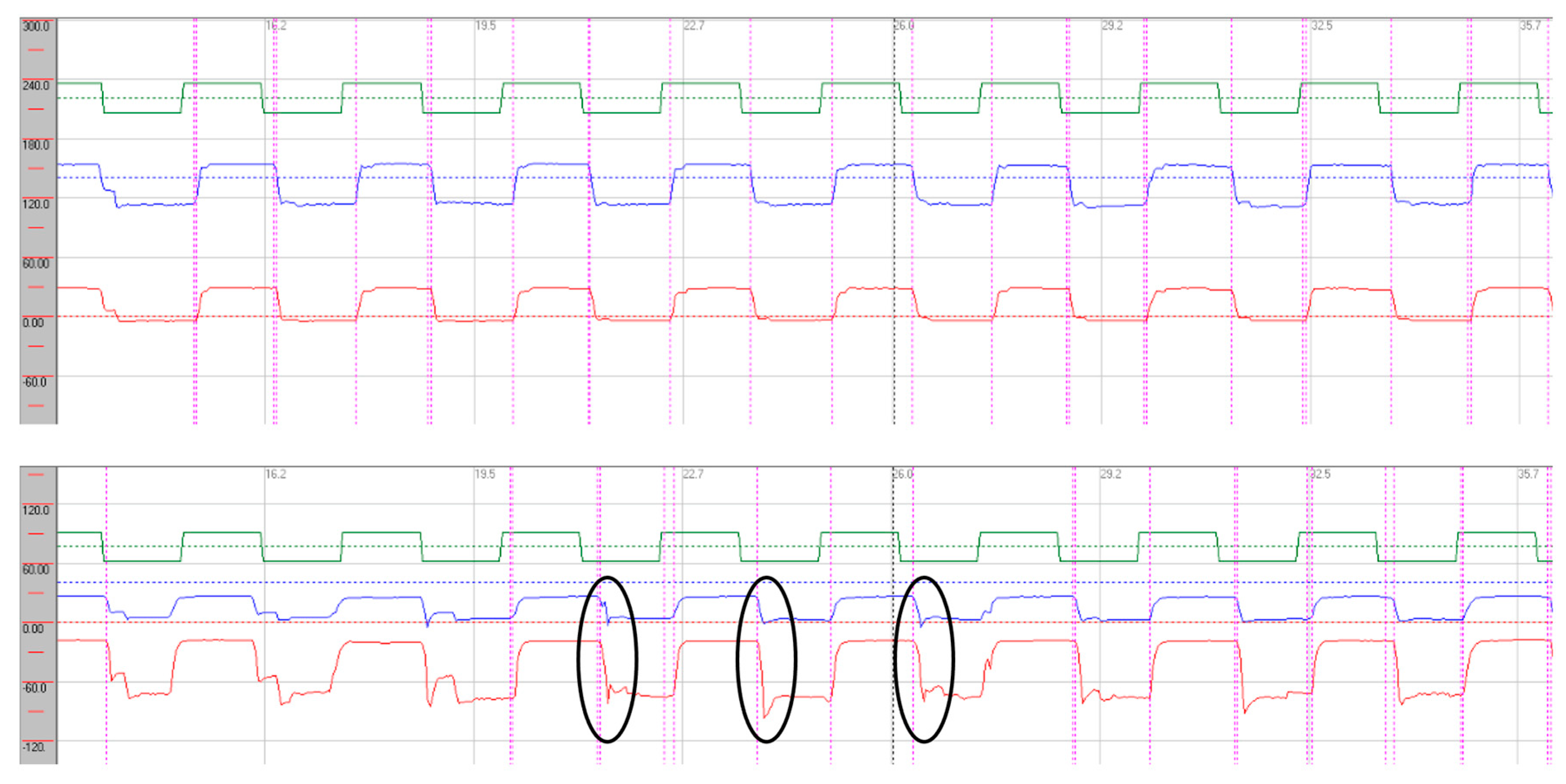

Oculomotor assessment and videonystagmography. Oculomotor testing was performed using videonystagmography (SYNAPSYS VNG Ulmer) with both monocular and binocular infrared cameras. In primary gaze, paroxysmal saccadic intrusions were observed in the horizontal plane together with horizontal nystagmus, as well as persistent vertical saccadic intrusions with an irregular, arrhythmic pattern (Supplementary Video 2). These phenomena were often superimposed, and square-wave jerks were also identified (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Rightward gaze testing revealed gaze-evoked horizontal nystagmus (Supplementary Video 3). During return to primary position we observed form of rebound nystagmus (Supplementary Video 4).

Smooth pursuit was severely impaired, most pronounced in the vertical plane, with reduced tracking accuracy and frequent catch-up saccades (see

Figure 5).

Horizontal saccades demonstrated normal latency without evidence of dysmetria. During vertical gaze testing, saccadic analysis revealed hypermetria of downward saccades (see

Figure 6).

Treatment. Immunotherapy was initiated with corticosteroids followed by plasmapheresis. Symptomatic treatment with a combination of benzodiazepines and neuroleptics was administered to relieve muscle stiffness and cramps. Subsequently, maintenance oral prednisone was introduced, with a favourable clinical effect. On follow up, oculomotor function showed improvement, with a reduction in gaze-holding deficits; however, gaze-evoked nystagmus persisted. Smooth pursuit in the horizontal plane demonstrated improved average gain values, and the previously observed hypermetria of downward saccades had resolved. Written and informed consent was obtained from patient.

4. Discussion

Anti-GAD–positive neurological disorders present with a broad phenotypical spectrum. The main clinical manifestations include stiff person syndrome (SPS), cerebellar ataxia, autoimmune epilepsy, limbic encephalitis, progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus, nystagmus, and other abnormal eye movements. These syndromes may occur in isolation or with significant overlap [

8].

A wide range of oculomotor abnormalities in anti-GAD SPS has been reported in the literature [

7]. However, their recognition in clinical practice remains substantially underdiagnosed and underappreciated [

4].

Oculomotor disturbances in anti-GAD SPS span several functional domains—those that stabilise vision on a target of interest and those that enable gaze shifts to new targets. They may range from non-specific findings to isolated nystagmus and/or oculomotor dysfunction of varying severity. Other abnormalities have also been described, including voluntary gaze provoking upper-quadrant facial hyperkinesias, conjugate eye deviations, and abduction paresis mimicking internuclear ophthalmoplegia. These disturbances are frequently exacerbated by fatigue or sensory stimuli [

9,

10,

11]. Overlapping features with other immune-mediated neurological disorders, such as myasthenia gravis, have also been reported [

6].

Central forms of nystagmus syndromes have been observed in the horizontal plane, such as gaze-evoked nystagmus, as well as in vertical forms, including downbeat nystagmus. These findings indicate dysfunction of brainstem and cerebellar gaze integrator circuits, such as the nucleus prepositus hypoglossi and the cerebellar flocculus, both of which rely heavily on GABAergic modulation. In downbeat nystagmus syndrome, vertical vestibulo-ocular reflexes depend on a balanced interaction of the semicircular canals, with the cerebellar flocculus selectively inhibiting anterior canal pathways [

12]. In case presentation 2, we observed a form of rebound nystagmus, a recognised sign of dysfunction of the neural integrator for gaze holding within brainstem–cerebellar circuits [

13].

Smooth pursuit dysfunction was observed in both patients and was more pronounced in the vertical plane, with slightly greater impairment during downward gaze. The severity of smooth pursuit deficits ranged from mild in case 1 to severe disruption in case 2. Some abnormalities, particularly mild pursuit deficits, may also occur in healthy individuals and should be interpreted carefully. Moreover, differences between horizontal and vertical pursuit are well recognised, with vertical pursuit generally being less accurate, and asymmetries between right–left or up–down movements may also occur [

14]. Shemesh et al. demonstrated in animal models that bilateral floccular lesions predominantly impair downward pursuit more than upward pursuit, possibly due to asymmetry in the vertical gaze-velocity Purkinje cells of the flocculus [

15]. This up–down asymmetry was evident in both of our cases, with deficits most pronounced during downward pursuit, as reflected by average gain values. An additional finding was deterioration of smooth pursuit with repeated stimulation, observed in case 1, suggesting oculomotor intolerance to repetitive activation.

Saccadic abnormalities were also frequent. Both cases demonstrated prolonged latencies, more pronounced in the vertical plane and particularly during downward gaze. Normal values are approximately 200 ms [

16]. On vertical downward gaze, we observed slight hypermetria of saccades in both patients, while case 1 also exhibited hypometric saccades in upward gaze. These alterations in latency and dysmetria may be attributed to dysfunction of the rostral interstitial nucleus of the medial longitudinal fasciculus (riMLF), the cerebellar vermis, and involvement of the fastigial nucleus. The presence of saccadic intrusions, opsoclonus, or flutter further supports widespread central involvement, consistent with dysfunction of omnipause neurons within the brainstem nuclei [

17]. In case presentation 2, we observed a mixture of intrusion types—both with and without an intersaccadic interval—indicating that these abnormalities may overlap with each other and with other oculomotor syndromes, such as nystagmus. In this case, intrusions occurred in the horizontal plane in a paroxysmal fashion and were almost continuous in the vertical plane [

18].

Oculomotor system abnormalities therefore represent additional signs in patients with anti-GAD SPS, or may reflect overlap with oculomotor dysfunction and nystagmus, which has been defined as a distinct clinical entity. Given the extensive network of oculomotor structures and functions, such abnormalities may be even more frequent than previously recognised, with some studies reporting their presence in up to 23% of patients [

19]. These manifestations may often be subtle or subclinical and may only be detected using Frenzel goggles or videonystagmography. These cases expand the recognised clinical spectrum of anti-GAD–associated SPS.

Autoimmune and immune-mediated mimics of anti-GAD–associated SPS with overlapping oculomotor signs span the broader spectrum of autoimmune cerebellar ataxias (e.g., gluten ataxia, post-infectious forms, primary autoimmune cerebellar ataxia) as well as Miller–Fisher syndrome, opsoclonus–myoclonus syndrome, and paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration [

20]. The differential further extends to selected movement disorders, genetic ataxias, infectious and metabolic aetiologies [

21]; among others ocular myasthenia should also be considered [

22]. In practice, differentiation begins with careful phenomenological analysis of eye-movement abnormalities in the context of associated neurological signs: downbeat nystagmus points to cerebellar syndromes [

23]; fatigable ocular motility supports myasthenia [

24]; florid opsoclonus–myoclonus commonly suggests a paraneoplastic process [

25]; and severe supranuclear ophthalmoplegia may indicate parkinsonian syndrome, particularly progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) [

26]. As oculomotor examination alone seldom achieves high aetiological specificity, ancillary testing—including electrophysiology, targeted antibody panels, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, neuroimaging, and tumour screening—is often warranted.

In Case 1, immunomodulatory therapy resulted in clinical improvement showed only partial improvement on saccadic testing. In Case 2, immunomodulatory therapy led to clear improvement in oculomotor function, especially in smooth pursuit and vertical saccades, with a reduction in saccadic intrusions in primary gaze.The beneficial effects of immunomodulation on oculomotor function have been reported with IVIG [

27] and with other agents such as rituximab [

28]. Improvement following immunomodulation raises the possibility of using oculomotor parameters as sensitive markers of therapeutic response, although causality cannot be established from two cases. Prospective studies with systematic evaluation of oculomotor profiles and treatment responses will be required.

5. Conclusion

Oculomotor abnormalities may represent clinically relevant, non-invasive markers of central oculomotor involvement in SPS. Taken together, these findings expand the recognised clinical phenotype of anti-GAD SPS. It is important to note, that observations presented in this paper are illustrative and hypothesis-generating rather than generalisable. They underscore the need for systematic, prospective studies employing quantitative oculomotor assessment, to clarify the prevalence, diagnostic significance, and therapeutic responsiveness of these abnormalities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary Video 1. Oculomotor eyelid phenomena on upward gaze with asymmetric contraction of the right orbicularis oculi and delayed relaxation, causing impaired vertical eye tracking on VNG with infrared binocular goggles. Supplementary Video 2. Videonystagmography during primary gaze showing saccadic intrusions in both the horizontal and vertical planes. Supplementary Video 3. Videonystagmography demonstrating gaze-evoked nystagmus. Supplementary Video 4. Videonystagmography demonstrating rebound nystagmus on return to primary position.

Author Contributions

PS and MT designed the study and collected and analyzed the data. JP and KS assisted in data collection. MG, SS and EK assited in data interpretation and revision. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Ethics Committee of the Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Slovakia, approved the realization of the research project (Approval No. EK 32/2023) on June 28, 2023. Written and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Written and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Muranova A, Shanina E. Stiff Person Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.

- Dalakas, MC. Stiff-person syndrome and related disorders—diagnosis, mechanisms and therapies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2024;20:587–601. [CrossRef]

- Chia NH, McKeon A, Dalakas MC, Flanagan EP, Bower JH, Klassen BT, Dubey D, Zalewski NL, Duffy D, Pittock SJ, Zekeridou A. Stiff person spectrum disorder diagnosis, misdiagnosis, and suggested diagnostic criteria. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2023 Jul;10(7):1083-1094. [CrossRef]

- Bose S, Jacob S. Stiff-person syndrome. Pract Neurol. 2025;25:6–17.

- Newsome SD, Johnson T. Stiff person syndrome spectrum disorders; more than meets the eye. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;369:577915. [CrossRef]

- Thomas S, Critchley P, Lawden M, Farooq S, Thomas A, Proudlock FA, et al. Stiff person syndrome with eye movement abnormality, myasthenia gravis, and thymoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(1):141–2. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Tourkevich R, Bosley J, Gold DR, Newsome SD. Ocular motor and vestibular characteristics of antiglutamic acid decarboxylase-associated neurologic disorders. J Neuroophthalmol. 2021;41(4):e665–71. [CrossRef]

- Baizabal-Carvallo, JF. The neurological syndromes associated with glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies. J Autoimmun. 2019;101:35–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarthi S, Goyal MK, Lal V. Pearls & Oy-sters: tonic eye deviation in stiff-person syndrome. Neurology. 2015;84(17):e124–7. [CrossRef]

- Economides JR, Horton JC. Eye movement abnormalities in stiff person syndrome. Neurology. 2005;65(9):1462–4. [CrossRef]

- Rucker JC, Leigh RJ. Eye movement abnormalities in movement disorders. Clin Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;1:2–7. [CrossRef]

- Antonini G, Nemni R, Giubilei F, Gragnani F, Ceschin V, Morino S, et al. Autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase in downbeat nystagmus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(7):998–9. [CrossRef]

- Otero-Millan J, Colpak AI, Kheradmand A, Zee DS. Rebound nystagmus, a window into the oculomotor integrator. Prog Brain Res. 2019;249:197–209. [CrossRef]

- Ke SR, Lam J, Pai DK, Spering M. Directional asymmetries in human smooth pursuit eye movements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(6):4409–21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shemesh AA, Zee DS. Eye movement disorders and the cerebellum. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2019;36(6):405–14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The neurology of eye movements. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

- Zivotofsky AZ, Siman-Tov T, Gadoth N, Gordon CR. A rare saccade velocity profile in Stiff-Person Syndrome with cerebellar degeneration. Brain Res. 2006;1093(1):135–40. [CrossRef]

- Lemos J, Eggenberger E. Saccadic intrusions: review and update. Curr Opin Neurol. 2013;26(1):59–66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakocevic G, Alexopoulos H, Dalakas MC. Quantitative clinical and autoimmune assessments in stiff person syndrome: evidence for a progressive disorder. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Mitoma H, Manto M, Hadjivassiliou M. Immune-Mediated Cerebellar Ataxias: Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment Based on Immunological and Physiological Mechanisms. J Mov Disord. 2021 Jan;14(1):10-28. [CrossRef]

- Kassavetis P, Kaski D, Anderson T, Hallett M. Eye Movement Disorders in Movement Disorders. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2022 Feb 16;9(3):284-295. [CrossRef]

- Behbehani, R. Ocular Myasthenia Gravis: A Current Overview. Eye Brain. 2023 Feb 5;15:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Ariño H, et al. Cerebellar ataxia and glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies. JAMA Neurol. 2014; 71, 1009–1016. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TT, Kang JJ, Chae JH, Lee E, Kim HJ, Kim JS, Oh SY. Oculomotor fatigability with decrements of saccade and smooth pursuit for diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. J Neurol. 2023 May;270(5):2743-2755. [CrossRef]

- Musunuru K, Kesari S. Paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus ataxia associated with non-small-cell lung carcinoma. J Neurooncol. 2008 Nov;90(2):213-6. [CrossRef]

- Chen AL, Riley DE, King SA, Joshi AC, Serra A, Liao K, Cohen ML, Otero-Millan J, Martinez-Conde S, Strupp M, Leigh RJ. The disturbance of gaze in progressive supranuclear palsy: implications for pathogenesis. Front Neurol. 2010 Dec 3;1:147. [CrossRef]

- Cruz RA, Gutierrez Treviño O. Isolated ophthalmoplegia: an uncommon presentation of anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (anti-GAD65) neurological syndrome. Cureus. 2024;16(12):e75375. [CrossRef]

- Kodama S, Tokushige SI, Sugiyama Y, Sato K, Otsuka J, Shirota Y, et al. Rituximab improves not only back stiffness but also “stiff eyes” in stiff person syndrome: implications for immune-mediated treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2020;408:116506. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).