Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Agro-Industrial Waste in Indonesia

2.1. Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME)

2.2. Cassava Wastes

2.3. Sugarcane Wastes

2.4. Soybean Waste

3. Microalgae Cultivation on Agro-Industrial Wastewaters

3.1. Growth Modes

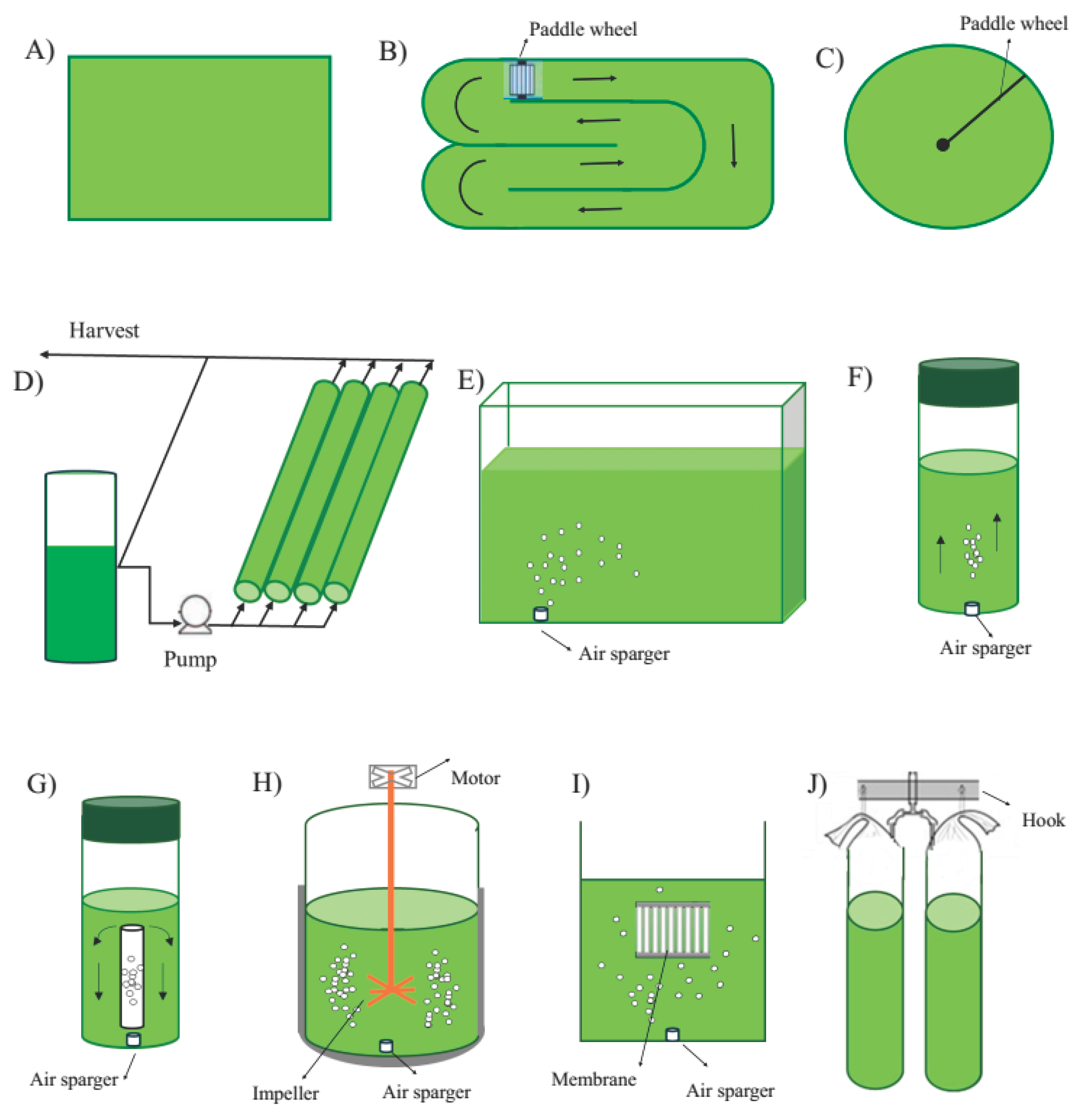

3.2. Cultivation Systems

3.3. Cultivation of Microalgae on Different Agro-Industrial Wastewaters

4. Environmental Benefits of Bioproducts from Agro-Industrial Residues

4.1. Nutrient Removal, COD/BOD Reduction, and Biomass Production

4.2. CO2 Capture and Potential Climate Mitigation

4.3. Other Multi-Benefit Strategies for Water, Energy, and Land Sustainability

5. Value-Added Bioproducts from Microalgal Biomass

5.1. Bioenergy

5.2. Pigments and Nutraceuticals

5.3. Biofertilizers, Biostimulants, Biocontrol Agents

5.4. Animal and Aquaculture Feed

6. Environmental Conditions and Opportunities for Microalgae Cultivation in Indonesia

7. Challenges and Limitations for Microalgae Cultivation in Indonesia

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Anaerobic Digestion |

| BOD | Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| CBEW | Cassava Biogas Effluent Wastewater |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CPW | Cassava Processing Wastewater |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| FAME | Fatty Acid Methyl Esters |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| HC | Hydrocarbon |

| HRAP | High-Rate Algal Pond |

| MBBR | Moving-Bed Biofilm Reactor |

| MBBR | Moving-Bed Biofilm Reactor |

| MBS | Microalgal Biostimulants |

| PBR | Photobioreactors |

| POME | Palm Oil Mill Effluent |

| POME | Palm Oil Mill Effluent |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid |

| TDS | Total Dissolved Solids |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| TP | Total Phosphorus |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| TWW | Tofu Whey Wastewater |

References

- Yuniarto, B.; Nurani, R.; Apriyono, A.; Rahmawati, R.; Nurfadilah, N. The Role of Geopolitics on Economic Growth in Indonesia. OPSearch Am. J. Open Res. 2024, 3, 251–257. [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, H.; Nurmalina, R.; Achsani, N.A.; Suroso, A.I.; Suprehatin, S. Indonesia’s Position and Participation in The Global Value Chain of The Agriculture Sector. J. Manaj. Dan Agribisnis 2025, 22, 105. [CrossRef]

- Sarma, M.; Septiani, S.; Nanere, M. The Role of Entrepreneurial Marketing in the Indonesian Agro-Based Industry Cluster to Face the ASEAN Economic Community. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6163. [CrossRef]

- Mileno, M.F. Industi Agro Indonesia Jadi Magnet Investasi, Serap Hingga 9 Juta Tenaga Kerja Available online: https://www.goodnewsfromindonesia.id/2025/04/02/industi-agro-indonesia-jadi-magnet-investasi-serap-hingga-9-juta-tenaga-kerja (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Kurniawan, R.D. Industri Agro Melemah di Q1 2025, Kemenperin Ungkap Biang Masalahnya Available online: https://wartaekonomi.co.id/read570500/industri-agro-melemah-di-q1-2025-kemenperin-ungkap-biang-masalahnya (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Hidayat, N.; Suhartini, S.; Arinda, T.; Elviliana, E.; Melville, L. Literature Review on Ability of Agricultural Crop Residues and Agro-Industrial Waste for Treatment of Wastewater. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Widayat; Philia, J.; Wibisono, J. Cultivation of Microalgae Chlorella Sp. on Fresh Water and Waste Water of Tofu Industry. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 31, 04009. [CrossRef]

- Hadiyanto, H. Ozone Application for Tofu Waste Water Treatment and Its Utilisation for Growth Medium of Microalgae Spirulina Sp. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 31, 03002. [CrossRef]

- Dwi Januari, A.; Warno Utomo, S.; Agustina, H. Estimation and Potential of Palm Oil Empty Fruit Bunches Based on Crude Palm Oil Forecasting in Indonesia. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 211, 05003. [CrossRef]

- Dianursanti; Rizkytata, B.T.; Gumelar, M.T.; Abdullah, T.H. Industrial Tofu Wastewater as a Cultivation Medium of Microalgae Chlorella vulgaris. Energy Procedia 2014, 47, 56–61. [CrossRef]

- Zahroh, S.F.; Syamsu, K.; Haditjaroko, L.; Kartawiria, I.S. Potential and Prospect of Various Raw Materials for Bioethanol Production in Indonesia: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 749, 012060. [CrossRef]

- Marthalia, L.; Tumuyu, S.S.; Asteria, D. Economy Circular Adoption toward Sustainable Business (Study Case: Agro-Industry Company in Indonesia). J. Pengelolaan Sumberd. Alam Dan Lingkung. J. Nat. Resour. Environ. Manag. 2024, 14, 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Mesa, J.A.; Sierra-Fontalvo, L.; Ortegon, K.; Gonzalez-Quiroga, A. Advancing Circular Bioeconomy: A Critical Review and Assessment of Indicators. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 324–342. [CrossRef]

- Pagels, F.; Amaro, H.M.; Tavares, T.G.; Amil, B.F.; Guedes, A.C. Potential of Microalgae Extracts for Food and Feed Supplementation-A Promising Source of Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Compounds. Life Basel Switz. 2022, 12, 1901. [CrossRef]

- Suhartini, S.; Indah, S.H.; Rahman, F.A.; Rohma, N.A.; Rahmah, N.L.; Nurika, I.; Hidayat, N.; Melville, L. Enhancing Anaerobic Digestion of Wild Seaweed Gracilaria verrucosa by Co-Digestion with Tofu Dregs and Washing Pre-Treatment. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2023, 13, 4255–4277. [CrossRef]

- Sahaq, A.B.; Hadiyanto The Bioelectricity of Tofu Wastewater in Microalgae-Microbial Fuel Cell (MMFC) System. Int. Adv. Res. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2019, 6, 37–39. [CrossRef]

- Elystia, S.; Saragih, L.R.; Muria, S.R. Algal-Bacterial Synergy for Lipid Production and Nutrient Removal in Tofu Liquid Waste. Int. J. Technol. 2021, 12, 287. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.; Mohanta, Y.K.; Reddy, C.N.; Reddy, S.D.M.; Mandal, S.K.; Yadavalli, R.; Sarma, H. Valorization of Agro-Industrial Biowaste to Biomaterials: An Innovative Circular Bioeconomy Approach. Circ. Econ. 2023, 2, 100050. [CrossRef]

- Sadh, P.K.; Duhan, S.; Duhan, J.S. Agro-Industrial Wastes and Their Utilization Using Solid State Fermentation: A Review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2018, 5, 1. [CrossRef]

- Rahmanulloh, A. Oilseeds and Products Annual: Indonesia (Report No. ID2025-0015).; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service, 2025;

- Sodri, A.; Septriana, F.E. Biogas Power Generation from Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME): Techno-Economic and Environmental Impact Evaluation. Energies 2022, 15, 7265. [CrossRef]

- Putra, S.E.; Dewata, I.; Barlian, E.; Syah, N.; Iswandi, U.; Gusman, M.; Amran, A.; Fariani, A. Analysis of Palm Oil Mill Effluent Quality. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 481, 03001. [CrossRef]

- Handayani, T.; Djarot, I.N.; Widyastuti, N.; Arianti, F.D.; Rifai, A.; Sitomurni, A.I.; Nur, M.M.A.; Dewi, R.N.; Nuha, N.; Haryanti, J.; et al. Biogas Quality and Nutrient Remediation in Palm Oil Mill Effluent through Chlorella vulgaris Cultivation Using a Photobioreactor. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Handayani, T.; Santoso, A.D.; Widyastuti, N.; Djarot, I.N.; Sitomurni, A.I.; Rifai, A.; Aziz, A.; Apriyanto, H.; Nadirah, N.; Kusrestuwardhani, K.; et al. Opportunity of Smart Aquaculture and Eco-Farming Integration in POME Bioremediation and Phycoremediation System for Environmental Sustainability. Evergreen 2025, 12, 903–931. [CrossRef]

- Sari, F.Y.A.; Suryajaya, I.M.A.; Christwardana, M.; Hadiyanto, H. Cultivation of Microalgae Spirulina platensis in Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) Media with Variations of POME Concentration and Nutrient Composition. J. Bioresour. Environ. Sci. 2022, 1, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, N.; Prasetyo, B.T.; Sofyan, Y.; Siregar, F. Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME): Biogas Power Plant. Distrib. Gener. Altern. Energy J. 2017, 6–18. [CrossRef]

- Hasanudin, U.; Sugiharto, R.; Haryanto, A.; Setiadi, T.; Fujie, K. Palm Oil Mill Effluent Treatment and Utilization to Ensure the Sustainability of Palm Oil Industries. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 72, 1089–1095. [CrossRef]

- Nuryadi, A.P.; Raksodewanto A, A.; Susanto, H.; Peryoga, Y. Analysis on the Feasibility of Small-Scale Biogas from Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) – Study Case: Palm Oil Mill in Riau-Indonesia. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 260, 03004. [CrossRef]

- Sinaga, A.R.I.; Nur, T.; Surya, I. Aspen Plus Simulation Analysis on Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) Recycling System into Bioethanol. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2023, 109, 41–50. [CrossRef]

- Hariyadi, T.P.; Jelita, M. Analisis Potensi Dan Evaluasi Emisi Biodiesel Dari Palm Oil Mill Effluent. J. Al-AZHAR Indones. Seri Sains dan Teknol. 2024, 9, 115. [CrossRef]

- Ratnasari, I.F.D.; Devi, D.; Yanuar Setyawan, I.A. Aplikasi Limbah Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) Terhadap Sifat Kimia Tanah Pada Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit. J. Media Pertan. 2024, 9, 113. [CrossRef]

- Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup Republik Indonesia Peraturan Menteri Lingkungan Hidup Nomor 5 Tahun 2014 Tentang Baku Mutu Air Limbah 2014.

- Media Bisnis Sawit Regulasi Baru Limbah Sawit Segera Terbit, KLHK Dorong Industri Hijau 2025.

- Pujono, H.R.; Kukuh, S.; Evizal, R.; Afandi; Rahmat, A. The Effect of POME Application on Production and Yield Components of Oil Palm in Lampung, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 648, 012058. [CrossRef]

- Siahaan, M.; Sakiah; Sutanto, A.S.; Lawary, A.; Mahmuda, R. The Study of Soil Biological and Chemical Properties on Palm Oil Plant Rhizosphere with and without Palm Oil Mill Effluent Applications. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 819, 012003. [CrossRef]

- Marsa Chairani, A.; Lestari, P.; Yuni Susanti, D.; Ngadisih; Clara Dione, N.; Labiba Azzahra, R.; Shiba Dhiyaul Rohma, A. Tropical Agricultural Waste Management: Exploring the Utilization of Cassava Husk for Extracting Cellulose and Starch as Sustainable Biomass Resources. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1438, 012072. [CrossRef]

- Edama, N.A.; Sulaiman, A.; Abd. Rahim, S.N. Enzymatic Saccharification of Tapioca Processing Wastes into Biosugars through Immobilization Technology. Biofuel Res. J. 2014, 1, 2–6. [CrossRef]

- Amalia, A.V.; Fibriana, F.; Widiatningrum, T.; Hardianti, R.D. Bioconversion and Valorization of Cassava-Based Industrial Wastes to Bioethanol Gel and Its Potential Application as a Clean Cooking Fuel. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 35, 102093. [CrossRef]

- Setyawati, R.; Katayama-Hirayama, K.; Kaneko, H.; Hirayaman, K. Current Tapioca Starch Wastewater (TSW) Management in Indonesia. World Appl. Sci. J. 2011, 14, 658–665.

- Kurniadie, D.; Wijaya, D.; Widayat, D.; Umiyati, U.; Iskandar Constructed Wetland to Treat Tapioca Starch Wastewater in Indonesia. Asian J. Water Environ. Pollut. 2018, 15, 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Hasanudin, U.; Kustyawati, M.E.; Iryani, D.A.; Haryanto, A.; Triyono, S. Estimation of Energy and Organic Fertilizer Generation from Small Scale Tapioca Industrial Waste. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 230, 012084. [CrossRef]

- Triani, H.; Yuniza, A.; Marlida, Y.; Husmaini, H.; Astuti, W.; Yanti, G. A Novel Bacterial Approach to Cassava Waste Fermentation: Reducing Cyanide Toxicity and Improving Quality to Ensure Livestock Feed Safety. Open Vet. J. 2025, 1. [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningtyas, R.D.; Hartanto, D.; Rohman, H.A.; Mitamaytawati; Qudus, N.; Daniyanto Valorization of Sugarcane-Based Bioethanol Industry Waste (Vinasse) to Organic Fertilizer. In Valorisation of Agro-industrial Residues – Volume II: Non-Biological Approaches; Zakaria, Z.A., Aguilar, C.N., Kusumaningtyas, R.D., Binod, P., Eds.; Applied Environmental Science and Engineering for a Sustainable Future; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 203–223 ISBN 978-3-030-39207-9.

- Adila, H.; Wisnu, W.; Handayani, E.T.; Fathin, H.R.; Rusdianto, A.S. Effectiveness of Sugarcane Bagasse Adsorbent Combined with Aquaponics System as an Innovation for Absorbing Contaminants in Sugar Industry Wastewater. Int. J. Food Agric. Nat. Resour. 2023, 4, 70–76. [CrossRef]

- Restiawaty, E.; Gani, K.P.; Dewi, A.; Arina, L.A.; Kurniawati, K.I.; Budhi, Y.W.; Akhmaloka, A. Bioethanol Production from Sugarcane Bagasse Using Neurospora intermedia in an Airlift Bioreactor. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2020, 9, 247–253. [CrossRef]

- Suryaningrum, L.H. Challenges and Strategies for the Utilization of Sugarcane Bagasse (By-Products of Sugar Industry) as Freshwater Fish Feed Ingredient. Perspektif 2022, 21, 26. [CrossRef]

- Kustiyah, E.; Novitasari, D.; Wardani, L.A.; Hasaya, H.; Widiantoro, M. Utilization of Sugarcane Bagasses for Making Biodegradable Plastics with the Melt Intercalation Method. J. Teknol. Lingkung. 2023, 24, 300–306.

- Jamir, L.; Kumar, V.; Kaur, J.; Kumar, S.; Singh, H. Composition, Valorization and Therapeutical Potential of Molasses: A Critical Review. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2021, 10, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Bandriyo, M.T.I.A.; Saukat, Y.; Rifin, A. Indonesian Molasses Export Supply in World Trade. J. Perspekt. Pembiayaan Dan Pembang. Drh. 2022, 10, 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Ginting, E.; Elisabeth, D.A.A.; Khamidah, A.; Rinaldi, J.; Ambarsari, I.; Antarlina, S.S. The Nutritional and Economic Potential of Tofu Dreg (Okara) and Its Utilization for High Protein Food Products in Indonesia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101175. [CrossRef]

- Pakpahan, M.R.; Ruhiyat, R.; Hendrawan, D. Evaluation of Wastewater Quality of Tempeh Industry (Case Study of Tempeh Semanan Industrial Estate).; Bandung, Indonesia, 2023; p. 020015.

- Wulansarie, R.; Fardhyanti, D.S.; Ardhiansyah, H.; Nuroddin, H.; Salsabila, C.A.; Alifiananda, T. Combination of Adsorption Using Activated Carbon and Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) Using O3/H2O2 in Decreasing BOD of Tofu Liquid Waste. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1381, 012041. [CrossRef]

- Bintari, S.H.; Herlina, L.; Wicaksono, D.; Sunyoto; Purnamaningrum, S.P.D.; Laksana, W.D.; Ulfa, B.M. Training on Making Liquid Organic Fertilizer from Tofu Whey Waste to Reduce Environmental Pollution. Abdimas J. Pengabdi. Masy. Univ. Merdeka Malang 2025, 10, 157–166. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Mishra, N.; Singh, G.; Mishra, S.; Lodhiyal, N. Microalgae Cultivation and Value-Based Products from Wastewater: Insights and Applications. Blue Biotechnol. 2024, 1, 20. [CrossRef]

- Muthukumaran, M.; Rawindran, H.; Noorjahan, A.; Parveen, M.; Barasarathi, J.; Blessie, J.P.J.; Ali, S.S.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Awasthi, M.K.; Hassan, S.; et al. Microalgae-Based Solutions for Palm Oil Mill Effluent Management: Integrating Phycoremediation, Biomass and Biodiesel Production for a Greener Future. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 191, 107445. [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.; Freitas, F.; Sobral, A.J.F.N.; Encarnação, T. Microalgae and Circular Economy: Unlocking Waste to Resource Pathways for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2025, 18, 2501488. [CrossRef]

- Nur, M.M.A.; Buma, A.G.J. Opportunities and Challenges of Microalgal Cultivation on Wastewater, with Special Focus on Palm Oil Mill Effluent and the Production of High Value Compounds. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 2079–2097. [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.R.; Deprá, M.C.; De Menezes, C.R.; Zepka, L.Q.; Jacob-Lopes, E. Microalgae Cultivation in Wastewater: How Realistic Is This Approach for Value-Added Product Production? Processes 2025, 13, 2052. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhao, W.; Mao, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, T.; Chen, F. High-Value Biomass from Microalgae Production Platforms: Strategies and Progress Based on Carbon Metabolism and Energy Conversion. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 227. [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.L.S.; Dutra, D.A.; Schneider, A.T.; Dias, R.R.; Deprá, M.C.; Zepka, L.Q.; Jacob-Lopes, E. Future Prospect of Development of Integrated Wastewater and Algal Biorefineries and Its Impact on Biodiversity and Environment. In Algal Biorefinery; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 371–383 ISBN 978-0-443-23967-0.

- Velásquez-Orta, S.B.; Yáñez-Noguez, I.; Ramírez, I.M.; Ledesma, M.T.O. Pilot-Scale Microalgae Cultivation and Wastewater Treatment Using High-Rate Ponds: A Meta-Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 46994–47021. [CrossRef]

- Cheah, W.Y.; Show, P.L.; Juan, J.C.; Chang, J.-S.; Ling, T.C. Enhancing Biomass and Lipid Productions of Microalgae in Palm Oil Mill Effluent Using Carbon and Nutrient Supplementation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 164, 188–197. [CrossRef]

- Alavianghavanini, A.; Shayesteh, H.; Bahri, P.A.; Vadiveloo, A.; Moheimani, N.R. Microalgae Cultivation for Treating Agricultural Effluent and Producing Value-Added Products. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169369. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.L.; Moniz, P.; Silva, C.; Reis, A. The Role of Heterotrophic Microalgae in Waste Conversion to Biofuels and Bioproducts. Processes 2021, 9, 1090. [CrossRef]

- Chia, S.R.; Ling, J.; Chia, W.Y.; Nomanbhay, S.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Chew, K.W. Future Bioenergy Source by Microalgae–Bacteria Consortia: A Circular Economy Approach. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 8935–8949. [CrossRef]

- Penloglou, G.; Pavlou, A.; Kiparissides, C. Recent Advancements in Photo-Bioreactors for Microalgae Cultivation: A Brief Overview. Processes 2024, 12, 1104. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Sánchez, D.; Martinez-Rodriguez, O.A.; Martinez, A. Heterotrophic Cultivation of Microalgae: Production of Metabolites of Commercial Interest: Heterotrophic Cultivation of Microalgae: Products. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2017, 92, 925–936. [CrossRef]

- Do, S.; Du, Z.-Y. Exploring the Impact of Environmental Conditions and Bioreactors on Microalgae Growth and Applications. Energies 2024, 17, 5218. [CrossRef]

- Braun, J.C.A.; Balbinot, L.; Beuter, M.A.; Rempel, A.; Colla, L.M. Mixotrophic Cultivation of Microalgae Using Agro-Industrial Waste: Tolerance Level, Scale up, Perspectives and Future Use of Biomass. Algal Res. 2024, 80, 103554. [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.-S.; Kim, Y.-S.; Yoon, H.-S. Effect of Different Cultivation Modes (Photoautotrophic, Mixotrophic, and Heterotrophic) on the Growth of Chlorella Sp. and Biocompositions. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 774143. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Kim, B.-H.; Ramanan, R.; Choi, J.-E.; Yang, J.-W.; Oh, H.-M.; Kim, H.-S. A Cost Analysis of Microalgal Biomass and Biodiesel Production in Open Raceways Treating Municipal Wastewater and under Optimum Light Wavelength. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, M.; Shaija, A.; Prashanth, P. Bubble Column Photobioreactor for Chlorella pyrenoidosa Cultivation and Validating Gas Hold up and Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient. Energy Sources Part Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 9779–9793. [CrossRef]

- Abdur Razzak, S.; Bahar, K.; Islam, K.M.O.; Haniffa, A.K.; Faruque, M.O.; Hossain, S.M.Z.; Hossain, M.M. Microalgae Cultivation in Photobioreactors: Sustainable Solutions for a Greener Future. Green Chem. Eng. 2024, 5, 418–439. [CrossRef]

- Shekh, A.; Sharma, A.; Schenk, P.M.; Kumar, G.; Mudliar, S. Microalgae Cultivation: Photobioreactors, CO2 Utilization, and Value-added Products of Industrial Importance. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 1064–1085. [CrossRef]

- Ting, H.; Haifeng, L.; Shanshan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhidan, L.; Na, D. Progress in Microalgae Cultivation Photobioreactors and Applications in Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2017, 10, 1–29.

- Shokravi, Z.; Mehravar, N. Optimization of Photobioreactor and Open Pond Systems for Sustainable Microalgal Biomass Production: Challenges, Solutions, and Scalability. In Microalgal Biofuels; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 45–62 ISBN 978-0-443-24110-9.

- Manu, L.; Mokolensang, J.F.; Ben Gunawan, W.; Setyawardani, A.; Salindeho, N.; Syahputra, R.A.; Iqhrammullah, M.; Nurkolis, F. Photobioreactors Are Beneficial for Mass Cultivation of Microalgae in Terms of Areal Efficiency, Climate Implications, and Metabolites Content. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101282. [CrossRef]

- Chanquia, S.N.; Vernet, G.; Kara, S. Photobioreactors for Cultivation and Synthesis: Specifications, Challenges, and Perspectives. Eng. Life Sci. 2022, 22, 712–724. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.H.; Yeom, S.H. Evaluation of Closed Photobioreactor Types and Operation Variables for Enhancing Lipid Productivity of Nannochloropsis sp. KMMCC 290 for Biodiesel Production. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2017, 22, 604–611. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, T. Biomass Productivity of Scenedesmus dimorphus (Chlorophyceae) Was Improved by Using an Open Pond–Photobioreactor Hybrid System. Eur. J. Phycol. 2019, 54, 127–134. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, J.C.; Molina-Aulestia, D.T.; Martinez-Burgos, W.J.; Karp, S.G.; Manzoki, M.C.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Rodrigues, C.; Scapini, T.; Vandenberghe, L.P.D.S.; Vieira, S.; et al. Agro-Industrial Wastewaters for Algal Biomass Production, Bio-Based Products, and Biofuels in a Circular Bioeconomy. Fermentation 2022, 8, 728. [CrossRef]

- Low, S.S.; Bong, K.X.; Mubashir, M.; Cheng, C.K.; Lam, M.K.; Lim, J.W.; Ho, Y.C.; Lee, K.T.; Munawaroh, H.S.H.; Show, P.L. Microalgae Cultivation in Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) Treatment and Biofuel Production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3247. [CrossRef]

- Nur, M.M.A.; Djarot, I.N.; Boelen, P.; Hadiyanto; Heeres, H.J. Co-Cultivation of Microalgae Growing on Palm Oil Mill Effluent under Outdoor Condition for Lipid Production. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2022, 34, 537–548. [CrossRef]

- Fernando, J.S.R.; Premaratne, M.; Dinalankara, D.M.S.D.; Perera, G.L.N.J.; Ariyadasa, T.U. Cultivation of Microalgae in Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) for Astaxanthin Production and Simultaneous Phycoremediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105375. [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.T.; Mohd Yasin, N.H.; Takriff, M.S.; Kamarudin, K.F.; Salihon, J.; Yaakob, Z.; Mohd Hakimi, N.I.N. Phycoremediation of Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) and CO2 Fixation by Locally Isolated Microalgae: Chlorella sorokiniana UKM2, Coelastrella sp. UKM4 and Chlorella pyrenoidosa UKM7. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 35, 101202. [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, K.M.; Bhuyar, P.; Ab. Rahim, M.H.; Govindan, N.; Maniam, G.P. Cultivation of Microalgae Spirulina platensis Biomass Using Palm Oil Mill Effluent for Phycocyanin Productivity and Future Biomass Refinery Attributes. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 2023, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Sorgatto, V.G.; Soccol, C.R.; Molina-Aulestia, D.T.; De Carvalho, M.A.; De Melo Pereira, G.V.; De Carvalho, J.C. Mixotrophic Cultivation of Microalgae in Cassava Processing Wastewater for Simultaneous Treatment and Production of Lipid-Rich Biomass. Fuels 2021, 2, 521–532. [CrossRef]

- Padri, M.; Boontian, N.; Teaumroong, N.; Piromyou, P.; Piasai, C. Application of Two Indigenous Strains of Microalgal Chlorella sorokiniana in Cassava Biogas Effluent Focusing on Growth Rate, Removal Kinetics, and Harvestability. Water 2021, 13, 2314. [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, K.; Coêlho, D.; Rodrigues, J.; Souza, R. Production of Scenedesmus sp. Microalgae in Cassava (Cassava Wastewater) for Extraction of Lipids. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2021, 11, 48393–48398.

- Tamil Selvan, S. Sustainable Bioremediation of Cassava Waste Effluent Using Nannochloropsis salina TSD06: An Eco-Technological Approach. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 642. [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Melo, L.B.U.; Borrego, B.B.; Gracioso, L.H.; Perpetuo, E.A.; Do Nascimento, C.A.O. Sugarcane Vinasse as Feedstock for Microalgae Cultivation: From Wastewater Treatment to Bioproducts Generation. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 41, 911–921. [CrossRef]

- Serejo, M.L.; Ruas, G.; Braga, G.B.; Paulo, P.L.; Boncz, M.À. Chlorella vulgaris Growth on Anaerobically Digested Sugarcane Vinasse: Influence of Turbidity. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2021, 93, e20190084. [CrossRef]

- Candido, C.; Cardoso, L.G.; Lombardi, A.T. Bioprospecting and Selection of Tolerant Strains and Productive Analyses of Microalgae Grown in Vinasse. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2022, 53, 845–855. [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Dallos, V.; García-Martínez, J.B.; Contreras-Ropero, J.E.; Barajas-Solano, A.F.; Barajas-Ferrerira, C.; Lavecchia, R.; Zuorro, A. Vinasse as a Sustainable Medium for the Production of Chlorella vulgaris UTEX 1803. Water 2019, 11, 1526. [CrossRef]

- Putri, N.A.; Dewi, R.N.; Lestari, R.; Yuniar, R.A.; Ma’arif, L.M.; Erianto, R. Microalgae as A Bioremediation Agent for Palm Oil Mill Effluent: Production of Biomass and High Added Value Compounds. J. Rekayasa Kim. Lingkung. 2023, 18, 149–161. [CrossRef]

- Ajijah, N.; Tjandra, B.C.; Hamidah, U.; Widyarani; Sintawardani, N. Utilization of Tofu Wastewater as a Cultivation Medium for Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 483, 012027. [CrossRef]

- Elystia, S.; Nasution, F.H.M.; Sasmita, A. Rotary Algae Biofilm Reactor (RABR) Using Microalgae Chlorella sp. for Tofu Wastewater Treatment. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 87, 263–271. [CrossRef]

- Coutinho Rodrigues, O.H.; Itokazu, A.G.; Rörig, L.; Maraschin, M.; Corrêa, R.G.; Pimentel-Almeida, W.; Moresco, R. Evaluation of Astaxanthin Biosynthesis by Haematococcus pluvialis Grown in Culture Medium Added of Cassava Wastewater. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2021, 163, 105269. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, N.S.P.; De Almeida, J.M.O.; Fonseca, G.G.; De Carvalho, E.M. Clarification of Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) Vinasse for Microalgae Cultivation. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 19, 101125. [CrossRef]

- Naser, A.S.; Asiandu, A.P.; Sadewo, B.R.; Tsurayya, N.; Putra, A.S.; Kurniawan, K.I.A.; Suyono, E.A. The Effect of Salinity and Tofu Whey Wastewater on the Growth Kinetics, Biomass, and Primary Metabolites in Euglena Sp. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Taufikurahman, T.; Irene, J.; Melani, L.; Marwani, E.; Purba, L.D.A.; Susanti, H. Optimizing Microalgae Cultivation in Tofu Wastewater for Sustainable Resource Recovery: The Impact of Salicylic Acid on Growth and Astaxanthin Production. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-K.; Wang, X.; Miao, J.; Tian, Y.-T. Tofu Whey Wastewater Is a Promising Basal Medium for Microalgae Culture. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 253, 79–84. [CrossRef]

- Oktaviani, Z.; Hendrasarie, N. Efektivitas Konsorsium Mikroalga Chlorella sp. dan Mikroba Indigenous Dalam Menurunkan BOD, COD, dan TN Air Limbah Industri Kecap Menggunakan MBBR. J. Serambi Eng. 2024, 9, 10724–10730.

- Faturrahman, A.; Rahmawati, A.; Anggoro, A.D.; Rahmah, A.F.; Haksara, M.F. Optimasi Konsorsium Mikroalga Chlorella Sebagai Upaya Revitalisasi Lingkungan Berbasis Biodegradasi Limbah POME (Palm Oil Mill Effluent). J. Ilmu Lingkung. 2025, 23, 721–729. [CrossRef]

- Basra, I.; Silalahi, L.; Pratama, W.D.; Joelyna, F.A. Pretreatment of Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) for Spirulina Cultivation. J. Emerg. Sci. Eng. 2023, 1, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Hariz, H.B.; Takriff, M.S.; Mohd Yasin, N.H.; Ba-Abbad, M.M.; Mohd Hakimi, N.I.N. Potential of the Microalgae-Based Integrated Wastewater Treatment and CO2 Fixation System to Treat Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) by Indigenous Microalgae; Scenedesmus sp. and Chlorella sp. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 32, 100907. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Bo, C.; Cao, S.; Sun, L. Enhancing CO2 Fixation in Microalgal Systems: Mechanistic Insights and Bioreactor Strategies. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 113. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Yuan, X.; Sahu, A.K.; Dewulf, J.; Ergas, S.J.; Van Langenhove, H. A Hollow Fiber Membrane Photo-bioreactor for CO2 Sequestration from Combustion Gas Coupled with Wastewater Treatment: A Process Engineering Approach. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 387–394. [CrossRef]

- Samoraj, M.; Çalış, D.; Trzaska, K.; Mironiuk, M.; Chojnacka, K. Advancements in Algal Biorefineries for Sustainable Agriculture: Biofuels, High-Value Products, and Environmental Solutions. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 58, 103224. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Sharma, P.K.; Chintala, V.; Khatri, N.; Patel, A. Environment-Friendly Biodiesel/Diesel Blends for Improving the Exhaust Emission and Engine Performance to Reduce the Pollutants Emitted from Transportation Fleets. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 3896. [CrossRef]

- Ammar, E.E.; Aioub, A.A.A.; Elesawy, A.E.; Karkour, A.M.; Mouhamed, M.S.; Amer, A.A.; EL-Shershaby, N.A. Algae as Bio-Fertilizers: Between Current Situation and Future Prospective. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 3083–3096. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.C.; Barata, A.; Batista, A.P.; Gouveia, L. Scenedesmus obliquus in Poultry Wastewater Bioremediation. Environ. Technol. 2019, 40, 3735–3744. [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, K.; Neeti, K.; Singh, R. Microalgae-Based Biodiesel Production and Its Challenges and Future Opportunities: A Review. Green Technol. Sustain. 2024, 2, 100060. [CrossRef]

- Wiley, P.E.; Campbell, J.E.; McKuin, B. Production of Biodiesel and Biogas from Algae: A Review of Process Train Options. Water Environ. Res. 2011, 83, 326–338. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, F.; Wu, Y.-R. Emerging Technologies for Conversion of Sustainable Algal Biomass into Value-Added Products: A State-of-the-Art Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 147024. [CrossRef]

- Spínola, M.P.; Mendes, A.R.; Prates, J.A.M. Chemical Composition, Bioactivities, and Applications of Spirulina (Limnospira platensis) in Food, Feed, and Medicine. Foods 2024, 13, 3656. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.R.; Spínola, M.P.; Lordelo, M.; Prates, J.A.M. Chemical Compounds, Bioactivities, and Applications of Chlorella vulgaris in Food, Feed and Medicine. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10810. [CrossRef]

- Savvidou, M.G.; Georgiopoulou, I.; Antoniou, N.; Tzima, S.; Kontou, M.; Louli, V.; Fatouros, C.; Magoulas, K.; Kolisis, F.N. Extracts from Chlorella vulgaris Protect Mesenchymal Stromal Cells from Oxidative Stress Induced by Hydrogen Peroxide. Plants 2023, 12, 361. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, K.; Duan, X.; Hill, D.; Barrow, C.; Dunshea, F.; Martin, G.; Suleria, H. Bioactive Compounds in Microalgae and Their Potential Health Benefits. Food Biosci. 2022, 49, 101932. [CrossRef]

- Christaki, E.; Bonos, E.; Florou-Paneri, P. Innovative Microalgae Pigments as Functional Ingredients in Nutrition. In Handbook of Marine Microalgae; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 233–243 ISBN 978-0-12-800776-1.

- Prates, J.A.M. Unlocking the Functional and Nutritional Potential of Microalgae Proteins in Food Systems: A Narrative Review. Foods 2025, 14, 1524. [CrossRef]

- García-Encinas, J.P.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Juárez, J.; Ornelas-Paz, J.D.J.; Del Toro-Sánchez, C.L.; Márquez-Ríos, E. Proteins from Microalgae: Nutritional, Functional and Bioactive Properties. Foods 2025, 14, 921. [CrossRef]

- Strauch, S.M.; Barjona Do Nascimento Coutinho, P. Bioactive Molecules from Microalgae. In Natural Bioactive Compounds; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 453–470 ISBN 978-0-12-820655-3.

- Ramos-Romero, S.; Torrella, J.R.; Pagès, T.; Viscor, G.; Torres, J.L. Edible Microalgae and Their Bioactive Compounds in the Prevention and Treatment of Metabolic Alterations. Nutrients 2021, 13, 563. [CrossRef]

- Conde, T.; Neves, B.; Couto, D.; Melo, T.; Lopes, D.; Pais, R.; Batista, J.; Cardoso, H.; Silva, J.L.; Domingues, P.; et al. Polar Lipids of Marine Microalgae Nannochloropsis oceanica and Chlorococcum amblystomatis Mitigate the LPS-Induced Pro-Inflammatory Response in Macrophages. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 629. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.V.; Pastrana, L.M.; Fuciños, P. Encapsulation of Microalgae-Based Products for Food and Feed Applications. In Handbook of Food and Feed from Microalgae; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 371–393 ISBN 978-0-323-99196-4.

- Martínez-Ruiz, F.; Andrade-Bustamante, G.; Holguín-Peña, R.; Renganathan, P.; Gaysina, L.; Sukhanova, N.; Puente, E. Microalgae as Functional Food Ingredients: Nutritional Benefits, Challenges, and Regulatory Considerations for Safe Consumption. Biomass 2025, 5, 25. [CrossRef]

- Molino, A.; Iovine, A.; Casella, P.; Mehariya, S.; Chianese, S.; Cerbone, A.; Rimauro, J.; Musmarra, D. Microalgae Characterization for Consolidated and New Application in Human Food, Animal Feed and Nutraceuticals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 2436. [CrossRef]

- Bernaerts, T.M.M.; Gheysen, L.; Kyomugasho, C.; Jamsazzadeh Kermani, Z.; Vandionant, S.; Foubert, I.; Hendrickx, M.E.; Van Loey, A.M. Comparison of Microalgal Biomasses as Functional Food Ingredients: Focus on the Composition of Cell Wall Related Polysaccharides. Algal Res. 2018, 32, 150–161. [CrossRef]

- Eltanahy, E.; Torky, A. CHAPTER 1. Microalgae as Cell Factories: Food and Feed-Grade High-Value Metabolites. In Microalgal Biotechnology; Shekh, A., Schenk, P., Sarada, R., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, 2021; pp. 1–35 ISBN 978-1-83916-003-5.

- Dhandwal, A.; Bashir, O.; Malik, T.; Salve, R.V.; Dash, K.K.; Amin, T.; Shams, R.; Wani, A.W.; Shah, Y.A. Sustainable Microalgal Biomass as a Potential Functional Food and Its Applications in Food Industry: A Comprehensive Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 32, 19110–19128. [CrossRef]

- Çelekli, A.; Özbal, B.; Bozkurt, H. Challenges in Functional Food Products with the Incorporation of Some Microalgae. Foods 2024, 13, 725. [CrossRef]

- Ronga, D.; Biazzi, E.; Parati, K.; Carminati, D.; Carminati, E.; Tava, A. Microalgal Biostimulants and Biofertilisers in Crop Productions. Agronomy 2019, 9, 192. [CrossRef]

- Renuka, N.; Guldhe, A.; Prasanna, R.; Singh, P.; Bux, F. Microalgae as Multi-Functional Options in Modern Agriculture: Current Trends, Prospects and Challenges. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1255–1273. [CrossRef]

- El-Kassas, H.Y.; Heneash, A.M.M.; Hussein, N.R. Cultivation of Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis Using Confectionary Wastes for Aquaculture Feeding. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2015, 13, 145–155. [CrossRef]

- Idenyi, J.N.; Eya, J.C.; Nwankwegu, A.S.; Nwoba, E.G. Aquaculture Sustainability through Alternative Dietary Ingredients: Microalgal Value-Added Products. Eng. Microbiol. 2022, 2, 100049. [CrossRef]

- Chauton, M.S.; Reitan, K.I.; Norsker, N.H.; Tveterås, R.; Kleivdal, H.T. A Techno-Economic Analysis of Industrial Production of Marine Microalgae as a Source of EPA and DHA-Rich Raw Material for Aquafeed: Research Challenges and Possibilities. Aquaculture 2015, 436, 95–103. [CrossRef]

- Chavan, K.J.; Chouhan, S.; Jain, S.; Singh, P.; Yadav, M.; Tiwari, A. Environmental Factors Influencing Algal Biodiesel Production. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2014, 31, 602–611. [CrossRef]

- Akter, F.; Songsomboon, K.; Ralph, P.J.; Kuzhiumparambil, U. A Comprehensive Overview of Microalgae- and Cyanobacteria-Derived Polysaccharides: Extraction, Structural Chemistry, Techno-Functional and Bioactive Properties. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 31, 102280. [CrossRef]

- Habibah, E.; Suyono, E.A.; Koerniawan, M.D.; Suwanti, L.T.; Siregar, U.J.; Budiman, A. Potential of Natural Sunlight for Microalgae Cultivation in Yogyakarta. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 963, 012041. [CrossRef]

- Sofiyah, E.S.; Septiariva, I.Y.; Suryawan, I.W.K. The Opportunity of Developing Microalgae Cultivation Techniques in Indonesia. Ber. Biol. 2021, 20, 221–233. [CrossRef]

- BPS-Statistics Indonesia Statistik Kelapa Sawit Indonesia 2023 (Indonesia Oil Palm Statistics 2023); BPS-Statistics Indonesia: Jakarta. Indonesia, 2024; Vol. 17; ISBN 1978-9947.

- Pusat Data dan Sistem Informasi Pertanian (Kementrian Pertanian) Outlook Ubi Kayu Komoditas Pertanian Subsektor Tanaman Pangan; Pusat Data dan Sistem Informasi Pertanian (Kementrian Pertanian), 2020; ISBN 1907-1507.

- Yuliansi, R.; Yuliastuti, R.; Setyaningsih, N. Biogas Production from Sugarcane Vinasee: A Review. J. Ris. Teknol. Pencegah. Pencemaran Ind. 2021, 12, 34–44.

- Derosya, V.; Ihsan, T. Assessing the Environmental Impact of Tofu Production: A Systematic Review for a Sustainable Industry. Agrointek J. Teknol. Ind. Pertan. 2025, 19, 261–272. [CrossRef]

- Lubis, D.M.; Sintawardhani, N.; Hamidah, U.; Astuti, D.I.; Dwiartama, A.; Widyarani Sustainability Assessment of Small-Scale Tofu Industry Based on Water Resource 2021.

- Cahyono, R.B.; Nugraha, M.G.; Pratama, A.R.; Insani, V.F.S.; Irianto, D.; Anugia, Z.; Sasmita, F.A.; Hadiyati, K.R.; Ariyanto, T. Biogas Potential for Sustainable Power Generation in Indonesia: Opportunity and Techno-Economic Analysis. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 30, 102143. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, S.; Qv, M.; Dai, D.; Liu, D.; Wang, W.; Tang, C.; Zhu, L. Microalgal Cultivation for the Upgraded Biogas by Removing CO2, Coupled with the Treatment of Slurry from Anaerobic Digestion: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 364, 128118. [CrossRef]

- Tongprawhan, W.; Srinuanpan, S.; Cheirsilp, B. Biocapture of CO2 from Biogas by Oleaginous Microalgae for Improving Methane Content and Simultaneously Producing Lipid. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 170, 90–99. [CrossRef]

- Rodero, M.D.R.; Lebrero, R.; Serrano, E.; Lara, E.; Arbib, Z.; García-Encina, P.A.; Muñoz, R. Technology Validation of Photosynthetic Biogas Upgrading in a Semi-Industrial Scale Algal-Bacterial Photobioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 279, 43–49. [CrossRef]

- Suhartini, S.; Pangestuti, M.B.; Elviliana; Rohma, N.A.; Junaidi, M.A.; Paul, R.; Nurika, I.; Rahmah, N.L.; Melville, L. Valorisation of Macroalgae for Biofuels in Indonesia: An Integrated Biorefinery Approach. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2024, 13, 269–304. [CrossRef]

- Markou, G.; Wang, L.; Ye, J.; Unc, A. Using Agro-Industrial Wastes for the Cultivation of Microalgae and Duckweeds: Contamination Risks and Biomass Safety Concerns. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1238–1254. [CrossRef]

- Santoso, A.; Hariyanti, J.; Pinardi, D.; Kusretuwardani, K.; Widyastuti, N.; Djarot, I.; Handayani, T.; Sitomurni, A.; Apriyanto, H. Sustainability Index Analysis of Microalgae Cultivation from Biorefinery Palm Oil Mill Effluent. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2023, 9, 559–576.

- Cavalcanti Pessôa, L.; Pinheiro Cruz, E.; Mosquera Deamici, K.; Bomfim Andrade, B.; Santana Carvalho, N.; Rocha Vieira, S.; Alves Da Silva, J.B.; Magalhães Pontes, L.A.; Oliveira De Souza, C.; Druzian, J.I.; et al. A Review of Microalgae-Based Biorefineries Approach for Produced Water Treatment: Barriers, Pretreatments, Supplementation, and Perspectives. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108096. [CrossRef]

- Djarot, I.N.; Pawignya, H.; Handayani, T.; Widyastuti, N.; Nuha, N.; Arianti, F.D.; Pertiwi, M.D.; Rifai, A.; Isharyadi, F.; Wijayanti, S.P.; et al. Enhancing Sustainability: Microalgae Cultivation for Biogas Enrichment and Phycoremediation of Palm Oil Mill Effluent - a Comprehensive Review. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2024, 36, 2347314. [CrossRef]

- Jeevanandam, J.; Harun, M.R.; Lau, S.Y.; Sewu, D.D.; Danquah, M.K. Microalgal Biomass Generation via Electroflotation: A Cost-Effective Dewatering Technology. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9053. [CrossRef]

- Padri, M.; Boontian, N.; Teaumroong, N.; Piromyou, P.; Piasai, C. Co-Culture of Microalga Chlorella sorokiniana with Syntrophic Streptomyces thermocarboxydus in Cassava Wastewater for Wastewater Treatment and Biodiesel Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 347, 126732. [CrossRef]

- Min, K.H.; Kim, D.H.; Ki, M.-R.; Pack, S.P. Recent Progress in Flocculation, Dewatering, and Drying Technologies for Microalgae Utilization: Scalable and Low-Cost Harvesting Process Development. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126404. [CrossRef]

| Parameters | National threshold [32] | Study 1 [34] | Study 2 [35] | Study 3 [22] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 5-9 | 8 | 7.71 | 7.5 – 8.9 |

| Total solid | 250 mg l−1 | 96 mg l−1 | 45 mg l−1 | 30 – 40 mg l−1 |

| Total nitrogen | 50 mg l−1 | 265.25 mg l−1 | 160 mg l−1 * | 1 – 18 mg l−1 |

| BOD | 100 mg l−1 | 189 mg l−1 | 180 mg l−1 | 20 – 300 mg l−1 |

| COD | 350 mg l−1 | 402 mg l−1 | 593 mg l−1 | 30 – 200 mg l−1 |

| Agro-industrial effluent | Microalgae | Medium pretreatment | Cultivation system | Biomass production/ Growth rate | Product | Removal efficiency |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POME | Co-cultivation Dunaliella sp, Spirulina sp., Nannochloropsis sp, Chaetoceros calciltrans |

F, D, A | Outdoor, 200 ml plastic bag, 75% POME added urea 450 mg l-1 | Growth rate 0.35 d-1 | Lipid 40% | - | [83] |

| POME | Haematococcus pluvialis, | F, D, A | Indoor, 2 L glass bottle, 7.5% POME | Growth rate 0.21 d-1 | Astaxanthin 22.43 mg l-1 | 50.9% COD, 49.3% TN, 69.4% TP |

[84] |

| POME | Chlorella sorokiniana UKM2 | F, D, A | Indoor, 2 L flask, 10% POME, 1% CO2 mixed with air |

Growth rate 1.06 d-1 | - | CO2 uptake rate 567 mg l-1 d-1, 100% ammonium, 65% TN, 56% TP | [85] |

| POME | Spirulina platensis | F, C, D, A | Indoor, 1 L conical flask-controlled conditions, 30% POME |

Biomass production 1.16 g l -1 | Phycocyanin 175,12 mg, Lipid 28.6 % |

- | [86] |

| POME | Different microalgae: Nannochloropsis oculate, Chlorella vulgaris, Spirulina platensis, | F, D | Outdoor, raceway ponds, direct sunlight, 25 and 30 °C, indoor, using a 1 L Erlenmeyer flask. Using POME at varying concentrations (10 %, 25 %, 50 %, and 100 %) | Growth rate: 0.21, 0.29, 0.152 d-1, respectively | Lipid 39.10, 14.34, 28.6%, respectively |

COD: 71-75, 97-99, 84.9%, respectively | [55] |

| CPW | Haematococcus pluvialis, Neochloris oleoabundans | F, D, A | Indoor, 2 L flask, 25% CPW | Biomass production 3.18 and 1.79 g l -1, respectively | Lipid 0.018 and 0.041 g l-1 d-1, respectively | 60.80 and 69.16% COD, 51.06 and 58.19% TN, 54.68 and 69.84% TP, respectively | [87] |

| CBEW | Chlorella sorokiniana P21 and WB1DG | F | Indoor, 12L acrylamide flask, 100% CBEW | Biomass production 2.6 and 1.3 g l-1, respectively | - | 73.78 and 63.42% COD, 92.11 and 91.68% TP, 67.33 and 70.66% TN, respectively | [88] |

| CPW | Scenedesmus sp. | F, D, A | Indoor, 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask, synthetic medium (ASM-1) supplemented with 5-10% CPW | Biomass 0.7 g l-1 | Lipid 35.5% | - | [89] |

| CPW | Nannochloropsis salina | F | Indoor, PBR 1500 L, 100% CPW | Biomass 7.25 g l-1 | Lipid 210.32 mg g-1, carbohydrates 125.34 mg ml-1, biodiesel 3.75 ml g-1 | 8.26% nitrate, 93.94% phosphate, 97.43% sulfate | [90] |

| Sugarcane vinasse | Coelastrella sp | C, CL, DC | Indoor, 250 ml Drechsler flask, 20% vinasse with 0.04% CO2 | Biomass 3.16 g l−1 | Carbohydrate 30%, lipid 20% | 53.9% COD | [91] |

| Sugarcane vinasse | Mixed culture is predominantly composed of Chlorella vulgaris |

No pretreatment | Indoor, 3 L glass bottle, raw vinasse containing anaerobic sludge from reactor treating vinasse |

Biomass 2.7 g l-1 | Lipid 265 mg l-1 | 98% TN | [92] |

| Sugarcane vinasse | Chlorella vulgaris | C, D | Indoor, 250 ml flask, 20% vinasse | Growth rate 1.41 d-1 | Protein 45.98 mg l-1, carbohydrate 6.67 mg l-1 | - | [93] |

| Sugarcane vinasse | Chlorella vulgaris | n.a. | Indoor, Tubular 6 L air-lift reactors, fully dark, 1% CO2, 75% vinasse | Biomass 8.7 g l-1, growth rate 0.72 g l-1 d-1 | Protein 45.95%, lipid 1.67% | - | [94] |

| TW | Spirulina sp., Nannochloropsis oculata | D, A | Indoor, 1 L polyethylene flask, 20% TW | Biomass 0.23 and 0.53 g l-1, respectively | Lipid 2.44 and 1.21%, respectively. Protein 1.71 and 1.51%, respectively | - | [95] |

| TW, TW-ADE |

Chlorella vulgaris, Arthrospira platensis |

D, A | Indoor, 1 L polyethylene flask, 5% TW, 3% TW, 100% TW-ADE | Biomass: C. vulgaris 2.0 g l-1 in 5% TW, A. plantesis 1.4 g l-1 in 5% TW; No growth at TW-ADE |

Protein: C. vulgaris 135.8 mg l-1 in 5% TW, A. platensis 42.5 mg l-1 in 3 % TW, Protein was not detected in TW-ADE |

- | [96] |

| TW | Chlorella sp. | D | Indoor, 18 L rotating algal biofilm reactor, 40% TW | Microalgae cells 3.99×106 cells m l-1 | - | 75.88% COD, 80.45% NH3 | [97] |

| No | Algal Species | Main Products | Applications | Health Benefits | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis/Limnospira platensis) | Phycocyanin (blue pigment); Proteins; Bioactive peptides | Natural blue food colorant, protein powders, supplements | Antioxidant, neuroprotective, immunomodulatory, antihypertensive | [14,116] |

| 2 | Chlorella vulgaris / C. pyrenoidosa | Chlorophylls; Proteins; Vitamin B12; Folate; Sulphated polysaccharides | Detox/immune supplements, bakery & beverage enrichment, vegan protein | Detoxification, gut microbiota modulation, antioxidant, ACE-inhibitory, antidiabetic | [117,118,119] |

| 3 | Haematococcus pluvialis | Astaxanthin; Carotenoids; PUFAs | Anti-ageing nutraceuticals, sports nutrition, antioxidant-rich supplements | Potent antioxidant, cardiovascular & skin protection, anti-inflammatory | [120,121,122] |

| 4 | Dunaliella salina | β-carotene; Luteins | Natural orange-red colorant, provitamin A supplements, functional foods | Eye health, antioxidant, and immune support | [121,123] |

| 5 | Nannochloropsis spp. | Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA); Proteins; Peptides; Chlorophyll; Carotenoids; Phytosterols | Vegan Omega-3 oil, aquafeed, functional beverages | Cardiovascular health, lipid metabolism, cognitive support, anticancer peptides | [124,125] |

| 6 | Isochrysis galbana | Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA); Proteins; Fucoxanthin; Phytosterols | Infant formulas, nutraceuticals | Neurological development, cardiovascular health, neuroprotective, antioxidant | [121,126,127] |

| 7 | Scenedesmus spp. | Lutein; Proteins; Carotenoids | Functional foods, eye health supplements | Antioxidant, ocular health, anti-inflammatory | [121,128] |

| 8 | Porphyridium spp. | Sulphated polysaccharides; Phycoerythrin (red pigment) | Food stabilizers, antiviral nutraceuticals | Antiviral, immune modulation, prebiotic functions | [129,130] |

| 9 | Muriellopsis spp. | Lutein | Eye health supplements, natural yellow colorants | Antioxidant, visual health | [131,132] |

| 10 | Schizochytrium | DHA (long-chain omega-3); EPA | Infant nutrition, vegan omega-3 oils | Brain & eye development, anti-inflammatory; cardiovascular health | [14,124] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).