Submitted:

28 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the specific patterns of functional connectivity disruption in the motor, default mode, and salience networks following a stroke, and how do these relate to different functional impairments?

- Which rehabilitation protocols, including task-specific motor training, cognitive exercises, or neuromodulatory interventions, are most effective in enhancing network-specific connectivity and promoting functional recovery?

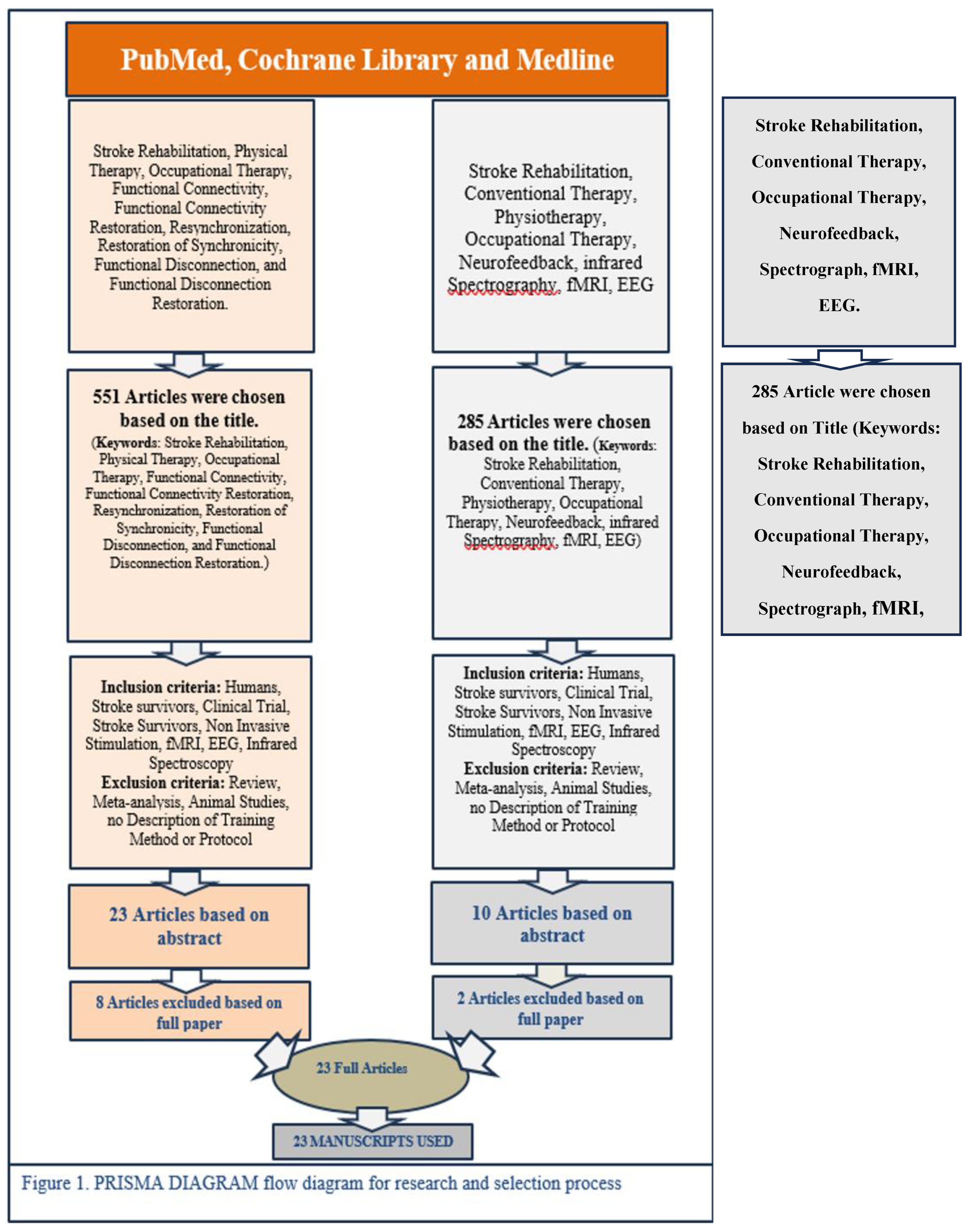

2. Method

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

| Search Terms | Filters | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| (“stroke rehabilitation” OR “post-stroke rehabilitation”) AND (“physical therapy” OR “occupational therapy” OR “neuromodulation” OR “neurofeedback” OR “infrared spectrography” OR “fMRI” OR “quantitative EEG”) AND (“functional disconnection” OR “functional connectivity” OR “resynchronization” OR “restoration of synchronicity”) | Date range: 2015–2025 Human studies English language |

Humans with a stroke Original clinical or real-world trials Non-invasive stimulation, imaging, or feedback-based interventions Focus on disruptions or restoration of functional connectivity |

Reviews, meta-analyses Animal studies No described intervention No mention of connectivity/disconnection |

3. Findings and Thematic Synthesis

3.1. Cognitive Training

| Author & Year | Participants (Age, Sex, N) | Key Measures | Intervention | Connectivity Disruption | Effect of Intervention |

Domain(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Yin [38] | 34 (rTMS grp 16 M/2 F; no-stim grp 16 M/2 F; ≈57 y) | MoCA, VST, RBMT, MBI; ALFF, FC | 10 Hz rTMS (L-DLPFC) + CACT (4 wk) | ↓ DMN (MPFC–hippocampus) | ↑ ALFF (L-MPFC), ↑ FC (R-MPFC→rACC) correlating with MoCA & VST improvements | Cognitive |

| 2. Qin et al. [40] | 49 (31 M/18 F; ≈59 y) | MAS, FMA-UE, MBI | 1 Hz rTMS + 10 Hz rPMS (8 wk) | Reticulospinal ↑ excitability; ↓ inhibition | ↑ ALFF (rSMA, rMFG, rCereb); ↓ ALFF (rPCG, lPrCG); improved spasticity & motor function | Motor |

| 3. Middag-Van Spanje et al. [41] | 22 (16 M/6 F; median ≈ 61 y) | SCT, CVDT, MLBT-d, SLBT, CBS, SNQ | 10 Hz tACS + VST (6 wk) | Disrupted lateralized spatial attention | ↑ Alpha synchronization; better contralesional detection; reduced visuospatial neglect | Cognitive/Spatial Attention |

| 4. Chen et al. [42] | 5 (3 M/2 F; 47–77 y) | UE-FM; rs-fMRI | Bihemispheric tDCS (1.5 mA) + PT/OT (2 wk) | ↓ Interhemispheric motor connectivity | ↑ Ipsilesional motor → contralesional premotor & precuneus connectivity → improved motor function | Motor |

| 5. Sinha et al. [43] | 23 (13 M/10 F; ≈62 y) | rs-fMRI; ARAT; 9-HPT; SIS; BI | EEG-BCI + FES (~15 sessions) | ↓ Interhemispheric M1 connectivity | ↑ M1–M1 and broader motor network rsFC; improved SIS (ADL, mobility) | Motor/ADL |

| 6. Mekbib et al. [44] | 8 stroke, 13 HC (≈57 y) | FM-UE; rs-fMRI | VR-LMT + conventional (1 h/day, 2 wk) | Bilateral M1 connectivity disrupted | ↑ Interhemispheric M1 connectivity; correlated with FM-UE gains | Motor |

| 7. Wittenberg et al. [45] | 13 (12 M/1 F; 44–81 y) | TMS (MEP); MRI (FA, BOLD); FM; WMFT | Intensive robotic vs. conventional (6–12 wk) | Affected M1–PMAd connectivity changes | ↑ M1–PMAd connectivity; correlated with improved motor outcomes | Motor |

| 8. Fan et al. [46] | 10 (8 M/2 F; ≈52 y) | FMA-UL; WMFT; FIM; rs-fMRI | Robot-assisted bilateral arm therapy (4 wk) | ↓ Interhemispheric SMC connectivity | ↑ M1–M1 rs-FC; improved FMA, WMFT, ADLs | Motor/ADL |

| 9. Hu et al. [47] | 19 stroke (14 M/5 F; ≈54 y), 11 HC | ALFF; ReHo; FC; FMA | MI-BCI ± tDCS (1 mA, 20 min; ~2 wk) | ↓ SMN, disrupted DMN | MI-BCI only: ↑ ALFF in contralesional SMN; ↓ ALFF/ReHo in posterior DMN; better FMA | Motor/Cognitive |

| 10. Wada et al. [48] | 9 (6 M/3 F; ≈64 y) | EEG (ERD strength); physio data | DMB-based neurofeedback (14 d) + conventional | Impaired motor cortical connectivity → weaker ERD | 22.9% ↑ ERD strength → reorganized motor pathways; improved spasticity | Motor |

| 11. Sebastian et al. [37] | 32 HC (42 y), 34 stroke (65 y) | EEG (BSI, LC); FMA; BBT; 9HPT | MI-BCI: VR avatar + FES (~25 sess) | Lateralization asymmetry (BSI, LC) → motor deficits | ↑ Symmetry (BSI, LC); correlated with better FMA and function | Motor |

| 12. Phang et al. [49] | 10 (6 M/4 F; 39–80 y) | EEG (MRCP, FC); IMU; classification accuracy | Lower-limb motor tasks BCI (17 min) | PFCC disconnection | ↑ PFCC strength hemiplegic side; marker of recovery | Motor/Sensorimotor Integration |

| 13. Li et al. [50] | 7 (5 HC, 2 stroke) | EEG–EMG (SPMI); isometric push/pull | GNN approach to EEG–EMG data | Traditional CMC inadequate | GNN: 88.9% accuracy; robust connectivity measure | Motor Intention Detection |

| 14. Gangemi et al. [51] | 30 (15 Exp/15 Ctrl; M = 20 F = 10; ≈58 y) | EEG (θ, α, β); clinical | Neurocognitive VR training (2D/3D) | (presumed) reduced α/β power | ↑ α/β band power; enhanced connectivity; neural improvements | Cognitive/Motor |

| 15. Ray et al. [52] | 30 (18 M/12 F; ≈50 y) | cFMA; SMR; ERD (EEG) | BMI + physiotherapy (several wk) | Possible interhemispheric inhibition → ↓ α desync | ↑ α desync ipsilesional; correlated with better motor recovery | Motor |

| 16. Phang et al. [53] | 11 (age ≈ 25 y) | EEG (frontoparietal corr.); BCI accuracy | Bipedal motor-prep BCI + neurofeedback | ↓ Frontoparietal α → poor classification | Lowering α improved BCI performance; enhanced synchronization | Motor |

| 17. Carino-Escobar et al. [54] | 9 (5 M/4 F; 43–85 y) | EEG (α, β ERD/ERS); FMA-UE | BCI + robotic hand orthosis (4 wk) | β-band disruptions; nonhomologous hemispheres | ↑ β power; correlated with motor recovery; cortical activation | Motor |

| 18. Chen et al. [55] | 46 (18–65 y) | BBS; TIS; balance tests; sEMG; fNIRS; FMA-LE; BI | Cerebellar vermis iTBS (3 wk) + PT | (implicit) vermis–cortical disruption | Hypothesized ↑ SMA excitability; better trunk/lower-limb activation | Motor/Balance |

| 19. Ramos-Murguialday et al. [56] | 28 (18–80 y) | cFMA; GAS; MAL; Ashworth; EMG; fMRI; LI | BMI + physiotherapy (1 h + 1 h/day, 4 wk) | (no long-term connectivity change) | Motor learning observed; EEG reorganization | Motor |

| 20. Cheng et al. [42] | 10 (4 M/6 F; ≈52 y) | fNIRS (OxyHb); sEMG; MSS | Robot-assisted hand therapy | (not specified) | ↑ prefrontal & SMC OxyHb; improved muscle synergy/activation | Motor |

| 21. Min Li et al. [57] | 8 (M = 8; age ≈24.5 y) | Behavioral (accuracy, RT); P300 (ERP) | Exoskeleton hand + fingertip haptics | Disrupted motor–perception loop | ↑ P300 amplitude; stronger M1/PM/S1 activation | Motor/Sensory Feedback |

| 22. Ripollés et al. [58] | 20 stroke (≈59 y), 14 Ctrl (≈56 y) | ARAT; APS; BBT; 9HPT; Barthel; neuropsych; fMRI | Music-supported therapy (4 wk) | ↓ auditory–motor network (SMA–PRG, PAC–IFG) | ↑ intrahemispheric connectivity (SMA–PRG, etc.); normalized network; gains in motor, sensory, some cognition | Motor/Sensory/Cognitive |

| 23. Chen et al. [59] | 72 (18–80 y; 4 groups) | MoCA; IADL; TCD (CBFV, PI, BHI) | CCT, tDCS, CACT, or CACT + tDCS (3 wk) | ↓ DMN–FP correlation | CACT + tDCS: ↑ cerebrovascular reactivity; bilateral prefrontal excitability | Cognitive |

3.1.1. Functional Disconnection Patterns Underlying Cognitive and Accompanying Physical Dysfunction

3.1.2. Connectivity and Synchronization Mechanisms Underpinning Cognitive Training Intervention Outcomes

3.2. Conventional Therapy

3.2.1. Functional Disconnection Patterns Underlying Sensory, Motor, and Cognitive Dysfunction

3.2.2. Connectivity and Synchronization Mechanisms Underpinning Conventional Intervention Outcomes

3.3. Robot-Assisted Enhanced Conventional Therapy

3.3.1. Functional Disconnection Patterns Underlying Sensory, Motor, and Cognitive Dysfunction

3.3.2. Connectivity and Synchronization Mechanisms Underpinning Robotics Enhanced Conventional Intervention Outcomes

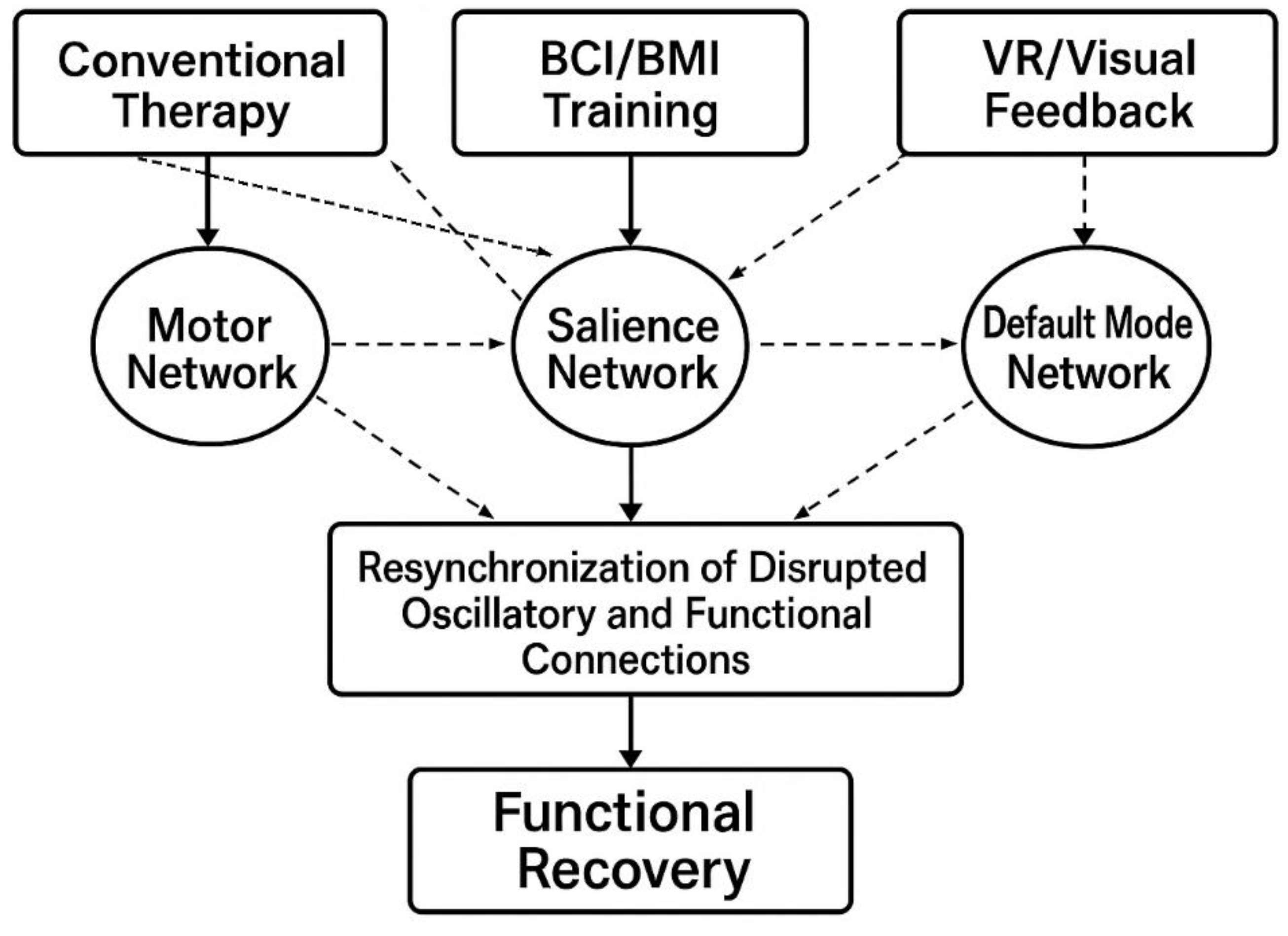

3.4. BMI, BCI, Virtual Reality, Visual Feedback-Enhanced Conventional Therapy

3.4.1. Functional Disconnection Patterns Underlying Sensory, Motor, and Cognitive Dysfunction

3.4.2. Connectivity and Synchronization Mechanisms Underpinning Feedback-Enhanced Conventional Intervention Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms of Network Restoration

4.1.1. Addressing Research Question 1: Patterns of Functional Connectivity Disruption

4.1.2. Addressing Research Question 2: Rehabilitation Protocol Effectiveness

4.1.3. Key Finding: Modality-Specific Network Targeting

4.2. Clinical Translation

4.3. Limitations of Current Evidence

4.4. Future Research Trajectories

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, C.O.; Nguyen, M.; Roth, G.A.; Nichols, E.; Alam, T.; Abate, D.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abraha, H.N.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Stark, B.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Roth, G.A.; Bisignano, C.; Abady, G.G.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abedi, V.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbetta, M.; Siegel, J.S.; Shulman, G.L. On the low dimensionality of behavioral deficits and alterations of brain network connectivity after focal injury. Cortex 2018, 107, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbetta, M.; Ramsey, L.; Callejas, A.; Baldassarre, A.; Hacker, C.D.; Siegel, J.S.; Astafiev, S.V.; Rengachary, J.; Zinn, K.; Lang, C.E.; et al. Common behavioral clusters and subcortical anatomy in stroke. Neuron 2015, 85, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.S.; Ramsey, L.E.; Snyder, A.Z.; Metcalf, N.V.; Chacko, R.V.; Weinberger, K.; Baldassarre, A.; Hacker, C.D.; Shulman, G.L.; Corbetta, M. Disruptions of network connectivity predict impairment in multiple behavioral domains after stroke. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E4367–E4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Heuvel, M.P.; Sporns, O. A cross-disorder connectome landscape of brain dysconnectivity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grefkes, C.; Fink, G.R. Connectivity-based approaches in stroke and recovery of function. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehme, A.K.; Grefkes, C. Cerebral network disorders after stroke: Evidence from imaging-based connectivity analyses of active and resting brain states in humans. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, C.; Chen, H.; Qin, W.; He, Y.; Fan, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, K.; Zang, Y.; et al. Dynamic functional reorganization of the motor execution network after stroke. Brain 2010, 133, 1224–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, A.; Ramsey, L.E.; Siegel, J.S.; Shulman, G.L.; Corbetta, M. Brain connectivity and neurological disorders after stroke. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2016, 29, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, K.M.; Valenstein, E.; Watson, R.T. Neglect and related disorders. Semin. Neurol. 2000, 20, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.R.; Astafiev, S.V.; Lang, C.E.; Connor, L.T.; Rengachary, J.; Strube, M.J.; Pope, D.L.W.; Shulman, G.L.; Corbetta, M. Resting interhemispheric functional magnetic resonance imaging connectivity predicts performance after stroke. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 67, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.D.; Halko, M.A.; Eldaief, M.C.; Pascual-Leone, A. Measuring and manipulating brain connectivity with resting state functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging (fcmri) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (tms). Neuroimage 2012, 62, 2232–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Schotten, M.T.; Foulon, C.; Nachev, P. Brain disconnections link structural connectivity with function and behaviour. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindenberg, R.; Renga, V.; Zhu, L.L.; Nair, D.; Schlaug, G. Bihemispheric brain stimulation facilitates motor recovery in chronic stroke patients. Neurology 2010, 75, 2176–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pino, G.; Pellegrino, G.; Assenza, G.; Capone, F.; Ferreri, F.; Formica, D.; Ranieri, F.; Tombini, M.; Ziemann, U.; Rothwell, J.C.; et al. Modulation of brain plasticity in stroke: A novel model for neurorehabilitation. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamoudi, M.; Schambra, H.M.; Fritsch, B.; Schoechlin-Marx, A.; Weiller, C.; Cohen, L.G.; Reis, J. Transcranial direct current stimulation enhances motor skill learning but not generalization in chronic stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2018, 32, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.S.; Rogasch, N.C.; Chiang, A.K.I.; Millard, S.K.; Skippen, P.; Chang, W.-J.; Bilska, K.; Si, E.; Seminowicz, D.A.; Schabrun, S.M. The influence of sensory potentials on transcranial magnetic stimulation—electroencephalography recordings. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022, 140, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, M.; Arumugum, N.; Midha, D. Combined effect of transcranial direct current stimulation (tdcs) and functional electrical stimulation (fes) on upper limb recovery in patients with subacute stroke. J. Neurol. Stroke 2019, 9, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, T.; Won, S.J.; Ramanathan, D.S.; Wong, C.C.; Bodepudi, A.; Swanson, R.A.; Ganguly, K. Robust neuroprosthetic control from the stroke perilesional cortex. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 8653–8661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M.; Ballester, B.R.; Verschure, P.F.M.J. Principles of neurorehabilitation after stroke based on motor learning and brain plasticity mechanisms. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerbeek, J.M.; Van Wegen, E.; Van Peppen, R.; Van Der Wees, P.J.; Hendriks, E.; Rietberg, M.; Kwakkel, G. What is the evidence for physical therapy poststroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlinchey, M.P.; James, J.; McKevitt, C.; Douiri, A.; McLachlan, S.; Sackley, C.M. The effect of rehabilitation interventions on physical function and immobility-related complications in severe stroke-protocol for a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimyan, M.A.; Cohen, L.G. Neuroplasticity in the context of motor rehabilitation after stroke. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2011, 7, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, N.; Izumi, S.-I. Rehabilitation with poststroke motor recovery: A review with a focus on neural plasticity. Stroke Res. Treat. 2013, 2013, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekna, M.; Pekny, M.; Nilsson, M. Modulation of neural plasticity as a basis for stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 2012, 43, 2819–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhorne, P.; Bernhardt, J.; Kwakkel, G. Stroke rehabilitation. Lancet 2011, 377, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Koski, L.; Xie, H. Combining rtms and task-oriented training in the rehabilitation of the arm after stroke: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Stroke Res. Treat. 2013, 2013, 539146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, F.C.; Cohen, L.G. Non-invasive brain stimulation: A new strategy to improve neurorehabilitation after stroke? Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, T.B.; Marshall, R.S.; Lazar, R.M. Stroke, cognitive deficits, and rehabilitation: Still an incomplete picture. Int. J. Stroke 2013, 8, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, S.T.; Rothwell, P.M. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.R.; Patel, K.R.; Astafiev, S.V.; Snyder, A.Z.; Rengachary, J.; Strube, M.J.; Pope, A.; Shimony, J.S.; Lang, C.E.; Shulman, G.L.; et al. Upstream dysfunction of somatomotor functional connectivity after corticospinal damage in stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2012, 26, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Fong, K.N.K. Effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation in modulating cortical excitability in patients with stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, L.E.; Siegel, J.S.; Lang, C.E.; Strube, M.; Shulman, G.L.; Corbetta, M. Behavioural clusters and predictors of performance during recovery from stroke. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Meer, M.P.A.; Van Der Marel, K.; Wang, K.; Otte, W.M.; El Bouazati, S.; Roeling, T.A.P.; Viergever, M.A.; Berkelbach Van Der Sprenkel, J.W.; Dijkhuizen, R.M. Recovery of sensorimotor function after experimental stroke correlates with restoration of resting-state interhemispheric functional connectivity. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 3964–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miotto, E.C.; Bazán, P.R.; Batista, A.X.; Conforto, A.B.; Figueiredo, E.G.; Martin, M.d.G.M.; Avolio, I.B.; Amaro, E.; Teixeira, M.J. Behavioral and neural correlates of cognitive training and transfer effects in stroke patients. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastián-Romagosa, M.; Udina, E.; Ortner, R.; Dinarès-Ferran, J.; Cho, W.; Murovec, N.; Matencio-Peralba, C.; Sieghartsleitner, S.; Allison, B.Z.; Guger, C. Eeg biomarkers related with the functional state of stroke patients. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, H.; Peng, L.; Ai, Y.; Luo, J.; Hu, X. Effects of rtms treatment on cognitive impairment and resting-state brain activity in stroke patients: A randomized clinical trial. Front. Neural Circuits 2020, 14, 563777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, B.J.; Gasson, N.; Bucks, R.S.; Troeung, L.; Loftus, A.M. Cognitive training and noninvasive brain stimulation for cognition in parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2017, 31, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, X. Effects of transcranial combined with peripheral repetitive magnetic stimulation on limb spasticity and resting-state brain activity in stroke patients. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 992424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middag-van Spanje, M.; Nijboer, T.C.W.; Schepers, J.; Van Heugten, C.; Sack, A.T.; Schuhmann, T. Alpha transcranial alternating current stimulation as add-on to neglect training: A randomized trial. Brain Commun. 2024, 6, fcae287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Liu, T.; Zhang, B.; Wu, X.; Song, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Ren, X.; Zhao, M.; Su, Y.; Wang, J. Effects of robot-assisted hand function therapy on brain functional mechanisms: A synchronized study using fnirs and semg. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1411616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.M.; Nair, V.A.; Prabhakaran, V. Brain-computer interface training with functional electrical stimulation: Facilitating changes in interhemispheric functional connectivity and motor outcomes post-stroke. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 670953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekbib, D.B.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, B.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, R.; Fang, S.; Shao, Y.; Yang, W.; Han, J.; et al. Proactive motor functional recovery following immersive virtual reality–based limb mirroring therapy in patients with subacute stroke. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittenberg, G.F.; Chen, R.; Ishii, K.; Bushara, K.O.; Taub, E.; Gerber, L.H.; Hallett, M.; Cohen, L.G. Constraint-induced therapy in stroke: Magnetic-stimulation motor maps and cerebral activation. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2003, 17, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.T.; Wu, C.Y.; Liu, H.L.; Lin, K.C.; Wai, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.L. Neuroplastic changes in resting-state functional connectivity after stroke rehabilitation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Cheng, H.-J.; Ji, F.; Chong, J.S.X.; Lu, Z.; Huang, W.; Ang, K.K.; Phua, K.S.; Chuang, K.-H.; Jiang, X.; et al. Brain functional changes in stroke following rehabilitation using brain-computer interface-assisted motor imagery with and without tdcs: A pilot study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 692304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Ono, Y.; Kurata, M.; (Imanishi) Ito, M.; (Tani) Minakuchi, M.; Kono, M.; Tominaga, T. Development of a brain-machine interface for stroke rehabilitation using event-related desynchronization and proprioceptive feedback. Adv. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 8, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, C.-R.; Su, K.-H.; Cheng, Y.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Ko, L.-W. Time synchronization between parietal–frontocentral connectivity with mrcp and gait in post-stroke bipedal tasks. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ji, H.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Jin, L.; Liu, L.; Bai, Z.; Ye, C. A sequential learning model with gnn for eeg-emg-based stroke rehabilitation bci. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1125230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, A.; De Luca, R.; Fabio, R.A.; Lauria, P.; Rifici, C.; Pollicino, P.; Marra, A.; Olivo, A.; Quartarone, A.; Calabrò, R.S. Effects of virtual reality cognitive training on neuroplasticity: A quasi-randomized clinical trial in patients with stroke. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, A.M.; Figueiredo, T.D.C.; López-Larraz, E.; Birbaumer, N.; Ramos-Murguialday, A. Brain oscillatory activity as a biomarker of motor recovery in chronic stroke. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 1296–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phang, C.-R.; Chen, C.-H.; Cheng, Y.-Y.; Chen, Y.-J.; Ko, L.-W. Frontoparietal dysconnection in covert bipedal activity for enhancing the performance of the motor preparation-based brain–computer interface. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carino-Escobar, R.I.; Carrillo-Mora, P.; Valdés-Cristerna, R.; Rodriguez-Barragan, M.A.; Hernandez-Arenas, C.; Quinzaños-Fresnedo, J.; Galicia-Alvarado, M.A.; Cantillo-Negrete, J. Longitudinal analysis of stroke patients’ brain rhythms during an intervention with a brain-computer interface. Neural Plast. 2019, 2019, 7084618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Su, W.; Gui, C.-F.; Guo, Q.-F.; Tan, H.-X.; He, L.; Jiang, H.-H.; Wei, Q.-C.; Gao, Q. Effectiveness of cerebellar vermis intermittent theta-burst stimulation in improving trunk control and balance function for patients with subacute stroke: A randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e066356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Murguialday, A.; Curado, M.R.; Broetz, D.; Yilmaz, Ö.; Brasil, F.L.; Liberati, G.; Garcia-Cossio, E.; Cho, W.; Caria, A.; Cohen, L.G.; et al. Brain-machine interface in chronic stroke: Randomized trial long-term follow-up. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2019, 33, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, J.; He, B.; He, G.; Zhao, C.-G.; Yuan, H.; Xie, J.; Xu, G.; Li, J. Stimulation enhancement effect of the combination of exoskeleton-assisted hand rehabilitation and fingertip haptic stimulation. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1149265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripollés, P.; Rojo, N.; Grau-Sánchez, J.; Amengual, J.L.; Càmara, E.; Marco-Pallarés, J.; Juncadella, M.; Vaquero, L.; Rubio, F.; Duarte, E.; et al. Music supported therapy promotes motor plasticity in individuals with chronic stroke. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016, 10, 1289–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, T.; Qu, Y. Computer-aided cognitive training combined with tdcs can improve post-stroke cognitive impairment and cerebral vasomotor function: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.; St George, B.; Fenton, M.; Firkins, L. Top 10 research priorities relating to life after stroke—consensus from stroke survivors, caregivers, and health professionals. Int. J. Stroke 2014, 9, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggisberg, A.G.; Koch, P.J.; Hummel, F.C.; Buetefisch, C.M. Brain networks and their relevance for stroke rehabilitation. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 1098–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J.M.; Wodeyar, A.; Srinivasan, R.; Cramer, S.C. Abstract tmp42: Coherent neural oscillations inform early stroke motor recovery. Stroke 2020, 51 (Suppl. S1), ATMP42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, N.S.; Brown, M.M.; Thompson, A.J.; Frackowiak, R.S.J. Neural correlates of outcome after stroke: A cross-sectional fmri study. Brain 2003, 126, 1430–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldsman, M.; Curwood, E.; Pathak, S.; Werden, E.; Brodtmann, A. Default mode network neurodegeneration reveals the remote effects of ischaemic stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2018, 89, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakkel, G.; Wagenaar, R.C.; Koelman, T.W.; Lankhorst, G.J.; Koetsier, J.C. Effects of intensity of rehabilitation after stroke: A research synthesis. Stroke 1997, 28, 1550–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granger, C.V.; Hamilton, B.B.; Keith, R.A.; Zielezny, M.; Sherwin, F.S. Advances in functional assessment for medical rehabilitation. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 1986, 1, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, K.O.; Wood-Dauphinee, S.L.; Williams, J.I.; Maki, B. Measuring balance in the elderly: Validation of an instrument. Can. J. Public Health. 1992, 83 (Suppl. S2), S7–S11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cramer, S.C.; Dodakian, L.; Le, V.; See, J.; Augsburger, R.; McKenzie, A.; Zhou, R.J.; Chiu, N.L.; Heckhausen, J.; Cassidy, J.M.; et al. Efficacy of home-based telerehabilitation vs in-clinic therapy for adults after stroke: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laver, K.E.; Adey-Wakeling, Z.; Crotty, M.; Lannin, N.A.; George, S.; Sherrington, C. Telerehabilitation services for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 1, CD010255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, E.; Miller, N.E.; Novack, T.A.; Cook, E.W., 3rd; Fleming, W.C.; Nepomuceno, C.S.; Connell, J.S.; Crago, J.E. Technique to improve chronic motor deficit after stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1993, 74, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, S.L.; Winstein, C.J.; Miller, J.P.; Taub, E.; Uswatte, G.; Morris, D.; Giuliani, C.; Light, K.E.; Nichols-Larsen, D.; Excite Investigators, F.T. Effect of constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity function 3 to 9 months after stroke: The excite randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2006, 296, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, A.J. Understanding sensorimotor adaptation and learning for rehabilitation. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2008, 21, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobath, B. Adult Hemiplegia: Evaluation and Treatment, 3rd ed.; Heinemann Medical Books: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Konosu, A.; Matsuki, Y.; Fukuhara, K.; Funato, T.; Yanagihara, D. Roles of the cerebellar vermis in predictive postural controls against external disturbances. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qi, G.; Yu, C.; Lian, G.; Zheng, H.; Wu, S.; Yuan, T.-F.; Zhou, D. Cortical plasticity is correlated with cognitive improvement in alzheimer’s disease patients after rtms treatment. Brain Stimul. 2021, 14, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.C.; Guarino, P.D.; Richards, L.G.; Haselkorn, J.K.; Wittenberg, G.F.; Federman, D.G.; Ringer, R.J.; Wagner, T.H.; Krebs, H.I.; Volpe, B.T.; et al. Robot-assisted therapy for long-term upper-limb impairment after stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1772–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrholz, J.; Pohl, M.; Platz, T.; Kugler, J.; Elsner, B. Electromechanical and robot-assisted arm training for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD006876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleim, J.A.; Jones, T.A. Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: Implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J. Speech. Lang. Hear. Res. 2008, 51, S225–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nudo, R.J. Mechanisms for recovery of motor function following cortical damage. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2006, 16, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, N.S. Restoring brain function after stroke—bridging the gap between animals and humans. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calautti, C.; Baron, J.-C. Functional neuroimaging studies of motor recovery after stroke in adults: A review. Stroke 2003, 34, 1553–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancause, N.; Nudo, R.J. Shaping plasticity to enhance recovery after injury. In Progress in Brain Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 192, pp. 273–295. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Murguialday, A.; Broetz, D.; Rea, M.; Läer, L.; Yilmaz, Ö.; Brasil, F.L.; Liberati, G.; Curado, M.R.; Garcia-Cossio, E.; Vyziotis, A.; et al. Brain–machine interface in chronic stroke rehabilitation: A controlled study. Ann. Neurol. 2013, 74, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khademi, F.; Naros, G.; Nicksirat, A.; Kraus, D.; Gharabaghi, A. Rewiring cortico-muscular control in the healthy and poststroke human brain with proprioceptive β-band neurofeedback. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 6861–6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laver, K.E.; Lange, B.; George, S.; Deutsch, J.E.; Saposnik, G.; Crotty, M. Virtual reality for stroke rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 11, CD008349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva Cameirão, M.; Bermúdez, I.; Badia, S.; Duarte, E.; Verschure, P.F.M.J. Virtual reality based rehabilitation speeds up functional recovery of the upper extremities after stroke: A randomized controlled pilot study in the acute phase of stroke using the rehabilitation gaming system. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2011, 29, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, P.L.; Rand, D.; Katz, N.; Kizony, R. Video capture virtual reality as a flexible and effective rehabilitation tool. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2004, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieme, H.; Morkisch, N.; Mehrholz, J.; Pohl, M.; Behrens, J.; Borgetto, B.; Dohle, C. Mirror therapy for improving motor function after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD008449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertelt, D.; Small, S.; Solodkin, A.; Dettmers, C.; McNamara, A.; Binkofski, F.; Buccino, G. Action observation has a positive impact on rehabilitation of motor deficits after stroke. Neuroimage 2007, 36, T164–T173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchal-Crespo, L.; Reinkensmeyer, D.J. Review of control strategies for robotic movement training after neurologic injury. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2009, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).