Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Linking Fatigue Testing to Additive Manufacturing Process

3. Current Research in Bending Fatigue of AM Metals

3.1. Influence of Process Parameters on Bending Fatigue Performance of AM Metals

3.2. Impact of Build Orientation on Bending Fatigue Performance

3.3. Impact of Post-Processing and Surface Treatments

3.4. Prediction Methodologies for Bending Fatigue Life in AM Metals

3.4.1. Numerical Approaches

3.4.2. Probabilistic Estimation

3.4.3. Machine Learning Approaches

4. Future Directions for Mitigating Challenges

4.1. Adapting Miniaturization Concepts

4.2. Application to Unique Geometries

4.3. Establish Correlation Across Different Fatigue Test Methods

4.4. Develop Standard Operating Procedures (SOP)

5. Conclusions

- Processing parameters play a significant role in surface roughness that determines bending fatigue performance. Although, these are very material, condition and process specific; usually, lower laser power and lower scanning speed provide lower number of defects due to fair control of melt path and avoiding large heat affected zones [52]. Lower powder particle size can significantly improve surface smoothness and fatigue strength due to their excellent melting and reduced staircase effect [54].

- Optimized scan strategy such as choosing a higher hatch offset distance with a higher number of contours can remelt the prior printed contours to reduce surface roughness [52].

- Horizontal build orientation with respect to scan direction exhibits the best bending fatigue performance compared to inclined and vertical orientations due to minimized melt-pool and layer boundaries that could act as failure propagations regions and alleviate stress concentration.

- Post-processing and surface treatment of AM metals significantly improve bending fatigue strength by mitigating two primary limitations, such as surface roughness and near-surface defects. But the effective choice of these techniques strongly relies on the material, processes, and geometry considerations coupled to consumer needs.

- For mitigating challenges associated with fabrication and sample preparation, the role of miniaturization, geometric effects and prediction methodologies need to be thoroughly explored and adapted by developing optimal standard procedures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beyer, C. Strategic Implications of Current Trends in Additive Manufacturing. J Manuf Sci Eng. 2014, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Najmon, J.C.; Raeisi, S.; Tovar, A. Review of additive manufacturing technologies and applications in the aerospace industry. Additive Manufacturing for the Aerospace Industry. Elsevier; 2019. p. 7–31.

- Uriondo, A.; Esperon-Miguez, M.; Perinpanayagam, S. The present and future of additive manufacturing in the aerospace sector: A review of important aspects. Proc Inst Mech Eng G J Aerosp Eng. 2015, 229, 2132–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, E.; Moon, S.K. Additive manufacturing for space: Status and promises. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2019, 105, 4123–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmon, J.C.; Raeisi, S.; Tovar, A. Review of additive manufacturing technologies and applications in the aerospace industry. Additive Manufacturing for the Aerospace Industry. Elsevier; 2019. p. 7–31.

- Altıparmak, S.C.; Xiao, B. A market assessment of additive manufacturing potential for the aerospace industry. J Manuf Process. 2021, 68, 728–738. [Google Scholar]

- Rafi, K.; Zhonghong Liu, A.; Di Prima, M.; Bates, P.; Seifi, M. Regulatory and standards development in medical additive manufacturing. MRS Bull. 2022, 47, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid Mohd Haleem, A. Additive manufacturing applications in medical cases: A literature based review. Alexandria Journal of Medicine. 2018, 54, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M. Additive Manufacturing Processes in Medical Applications. Materials. 2021, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Pisignano, D.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, J. Advances in Medical Applications of Additive Manufacturing. Engineering. 2020, 6, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, R.; Barreiros, F.M.; Alves, L.; Romeiro, F.; Vasco, J.C.; Santos, M.; et al. Additive manufacturing tooling for the automotive industry. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2017, 92, 1671–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, J.C. Additive manufacturing for the automotive industry. Addit Manuf. Elsevier; 2021. pp. 505–30.

- Ganesh Sarvankar, S.; Yewale, S.N. Additive Manufacturing in Automobile Industry. 2019, 7.

- Mcnulty, C.M.; Arnas, N.; Campbell, T.A. Toward the Printed World: Additive Manufacturing and Toward the Printed World: Additive Manufacturing and Implications for National Security Implications for National Security [Internet]. Available online: https://digitalcommons.ndu.edu/defense-horizons.

- Ukoba, K.; Yoro, K.O.; Adeoye, A.E.; Ampah, J.D.; Yusuf, A.A.; Samuel, F.O.; et al. Additive manufacturing in the energy sector and the fourth industrial revolution. Progress in Additive Manufacturing. Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH; 2025.

- Md Bahar Uddin, Md. Hossain, Suman Das. Advancing manufacturing sustainability with industry 4.0 technologies. International Journal of Science and Research Archive. 2022, 6, 358–366. [Google Scholar]

- Karthik, G.M.; Kim, H.S. Heterogeneous Aspects of Additive Manufactured Metallic Parts: A Review. Metals and Materials International. 2021, 27, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kirka, M.M.; Nandwana, P.; Lee, Y.; Dehoff, R.R. Solidification and solid-state transformation sciences in metals additive manufacturing. Scr Mater. 2017, 135, 130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Isanaka, S.P.; Liou, F. A Comprehensive Study of Cooling Rate Effects on Diffusion, Microstructural Evolution, and Characterization of Aluminum Alloys. Machines. 2025, 13, 160. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, M.; Keist, J.S.; Palmer, T.A. Defects in Metal Additive Manufacturing Processes. Additive Manufacturing Processes. ASM International; 2020. p. 277–86.

- Kim, F.H.; Moylan, S.P. Literature review of metal additive manufacturing defects. Gaithersburg, MD; 2018 May.

- Morettini, G.; Razavi, N.; Zucca, G. Effects of build orientation on fatigue behavior of Ti-6Al-4V as-built specimens produced by direct metal laser sintering. Procedia Structural Integrity. 2019, 24, 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Konecna, R.; Varmus, T.; Nicoletto, G.; Jambor, M. Influence of Build Orientation on Surface Roughness and Fatigue Life of the Al2024-RAM2 Alloy Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF). Metals (Basel). 2023, 13, 1615. [Google Scholar]

- Bača, A.; Konečná, R.; Nicoletto, G.; Kunz, L. Influence of Build Direction on the Fatigue Behaviour of Ti6Al4V Alloy Produced by Direct Metal Laser Sintering. Mater Today Proc. 2016, 3, 921–924. [Google Scholar]

- Leuders, S.; Thöne, M.; Riemer, A.; Niendorf, T.; Tröster, T.; Richard, H.A.; et al. On the mechanical behaviour of titanium alloy TiAl6V4 manufactured by selective laser melting: Fatigue resistance and crack growth performance. Int J Fatigue. 2013, 48, 300–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kasperovich, G.; Hausmann, J. Improvement of fatigue resistance and ductility of TiAl6V4 processed by selective laser melting. J Mater Process Technol. 2015, 220, 202–214. [Google Scholar]

- Molaei, R.; Fatemi, A.; Phan, N. Notched fatigue of additive manufactured metals under axial and multiaxial loadings, Part I: Effects of surface roughness and HIP and comparisons with their wrought alloys. Int J Fatigue. 2021, 143, 106003. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti, M.; Torresani, E.; Leoni, M.; Fontanari, V.; Bandini, M.; Pederzolli, C.; et al. The effect of post-sintering treatments on the fatigue and biological behavior of Ti-6Al-4V ELI parts made by selective laser melting. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2017, 71, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J.; Dong, Y. Effects of Post-processing on the Surface Finish, Porosity, Residual Stresses, and Fatigue Performance of Additive Manufactured Metals: A Review. J Mater Eng Perform. 2021, 30, 6407–6425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, W.-J.; Ojha, A.; Li, Z.; Engler-Pinto, C.; Su, X. Effect of residual stress on fatigue strength of 316L stainless steel produced by laser powder bed fusion process. Progress in Additive Manufacturing. 2021, 6, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.C.; Brice, D.A.; Samimi, P.; Ghamarian, I.; Fraser, H.L. Microstructural Control of Additively Manufactured Metallic Materials. Annu Rev Mater Res. 2016, 46, 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard Test Method for Bending Fatigue Testing for Copper-Alloy Spring Materials 1. Available online: www.astm.org.

- Parvez, M.M.; Pan, T.; Chen, Y.; Karnati, S.; Newkirk, J.W.; Liou, F. High cycle fatigue performance of lpbf 304l stainless steel at nominal and optimized parameters. Materials. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M.M.; Chen, Y.; Karnati, S.; Coward, C.; Newkirk, J.W.; Liou, F. A displacement controlled fatigue test method for additively manufactured materials. Applied Sciences (Switzerland). 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Ribeiro, A.; Ribeiro, A.S.; José AFOCorreia utadpt LSilva, A.L.; Pde Jesus, A.M. EVOLUTION OF FATIGUE HISTORY [Internet]. 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299397997.

- Schütz, W. A history of fatigue. Eng Fract Mech [Internet]. 1996, 54, 263–300. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0013794495001786. [CrossRef]

- Parida, B.K. Fatigue Testing. Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology. Elsevier; 2001. p. 2994–9.

- Pineau, A.; McDowell, D.L.; Busso, E.P.; Antolovich, S.D. Failure of metals II: Fatigue. Acta Mater. 2016, 107, 484–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metal Fatigue Analysis Handbook - Google Books.

- CESCHINILJ A Servo mechanical-fatigue-test Machine. Exp Tech. 1984, 8, 34–37. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.M.; Milligan, W.W. High Cycle Fatigue of Structural Materials. 1997.

- Standard Practice for Presentation of Constant Amplitude Fatigue Test Results for Metallic Materials 1. Available online: www.astm.org.

- Standard Test Method for Strain-Controlled Fatigue Testing 1. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/da00a040-7358-47d2-95f2-2cafe405fbc4/astm-e606-e606m-12.

- Rafi, H.K.; Karthik, N.V.; Gong, H.; Starr, T.L.; Stucker, B.E. Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Ti6Al4V Parts Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting and Electron Beam Melting. J Mater Eng Perform. 2013, 22, 3872–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, E.; Heckenberger, U.; Holzinger, V.; Buchbinder, D. Additive manufactured AlSi10Mg samples using Selective Laser Melting (SLM): Microstructure, high cycle fatigue, and fracture behavior. Mater Des. 2012, 34, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellyson, B.; Brochu, M.; Brochu, M. Characterization of bending vibration fatigue of SLM fabricated Ti-6Al-4V. Int J Fatigue. 2017, 99, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, S.; Nezhadfar, P.D.; Shamsaei, N.; Seifi, M.; Beretta, S. High cycle fatigue behavior and life prediction for additively manufactured 17-4 PH stainless steel: Effect of sub-surface porosity and surface roughness. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics. 2020, 106, 102477. [Google Scholar]

- Leuders, S.; Lieneke, T.; Lammers, S.; Tröster, T.; Niendorf, T. On the fatigue properties of metals manufactured by selective laser melting – The role of ductility. J Mater Res. 2014, 29, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, M.; Tang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, C.; Tang, Z.; Yin, Y.; et al. A holistic review on fatigue properties of additively manufactured metals. J Mater Process Technol. Elsevier Ltd; 2024.

- Afroz, L.; Das, R.; Qian, M.; Easton, M.; Brandt, M. Fatigue behaviour of laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) Ti–6Al–4V, Al–Si–Mg and stainless steels: A brief overview. Int J Fract. 2022, 235, 3–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanifard, S.; Adibeig, M.R.; Hashemi, S.M. Determining strain-based fatigue parameters of additively manufactured Ti–6Al–4V: Effects of process parameters and loading conditions. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2022, 121, 8051–8063. [Google Scholar]

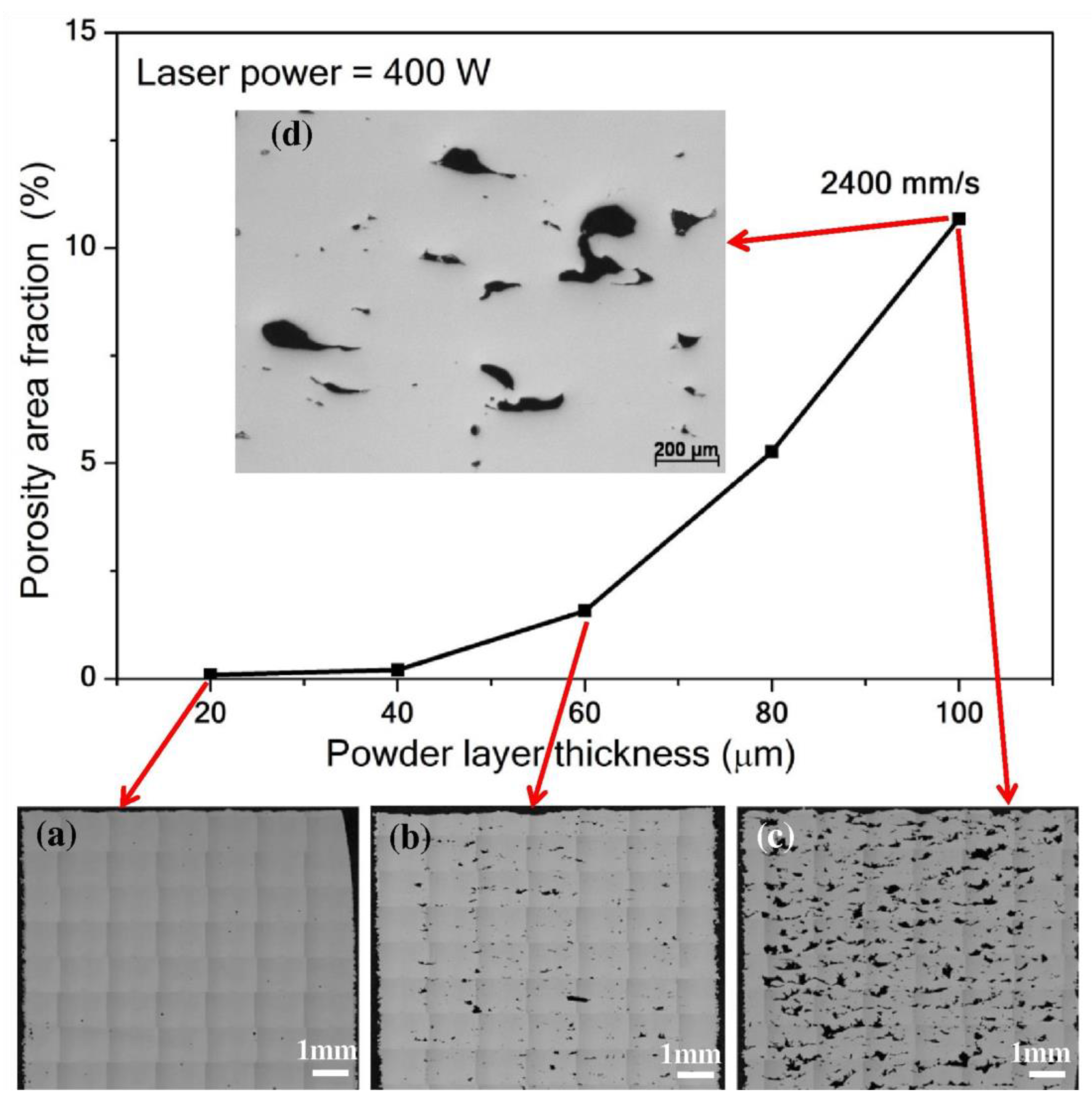

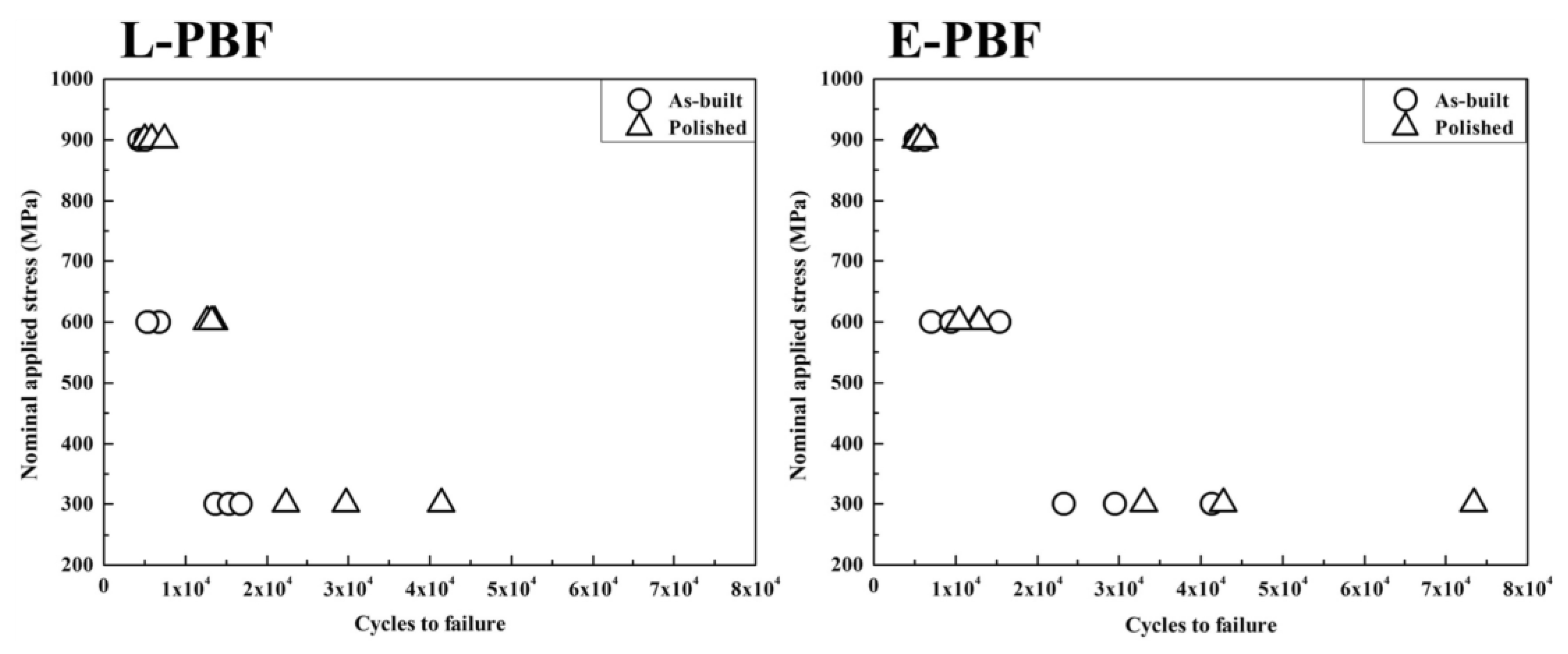

- Ramirez, B.; Banuelos, C.; De La Cruz, A.; Nabil, S.T.; Arrieta, E.; Murr, L.E.; et al. Effects of Process Parameters and Process Defects on the Flexural Fatigue Life of Ti-6Al-4V Fabricated by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Materials. 2024, 17, 4548. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S.; Ma, R.; Attardo, R.; Tomonto, C.; Nordin, M.; Wheelock, P.; et al. Impact of Surface and Pore Characteristics on Fatigue Life of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Ti-6Al-4V Alloy Described by Neural Network Models.

- Qiu, C.; Panwisawas, C.; Ward, M.; Basoalto, H.C.; Brooks, J.W.; Attallah, M.M. On the role of melt flow into the surface structure and porosity development during selective laser melting. Acta Mater. 2015, 96, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.M.; Lin, X.; Guo, P.F.; Yang, H.O.; Tan, H.; Chen, J.; et al. Low cycle fatigue properties of Ti-6Al-4V alloy fabricated by high-power laser directed energy deposition: Experimental and prediction. Int J Fatigue. 2019, 127, 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hatami, S. Variation of fatigue strength of parts manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. Powder Metallurgy. 2022, 65, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

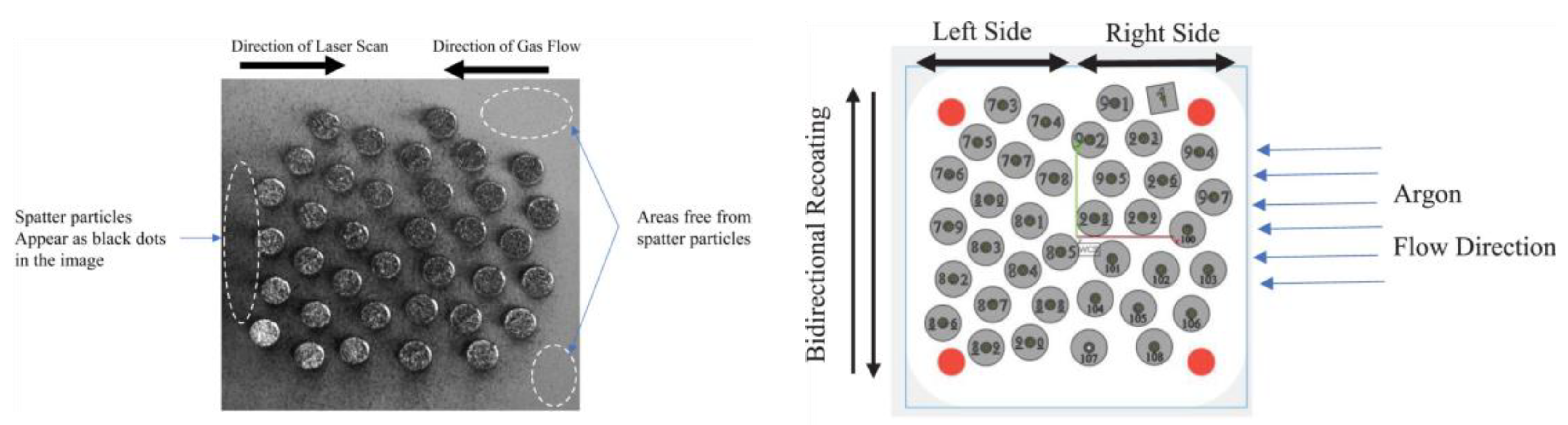

- Simonelli, M.; Tuck, C.; Aboulkhair, N.T.; Maskery, I.; Ashcroft, I.; Wildman, R.D.; et al. A Study on the Laser Spatter and the Oxidation Reactions During Selective Laser Melting of 316L Stainless Steel, Al-Si10-Mg, and Ti-6Al-4V. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A. 2015, 46, 3842–3851. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Mai, S.; Wang, D.; Song, C. Investigation into spatter behavior during selective laser melting of AISI 316L stainless steel powder. Mater Des. 2015, 87, 797–806. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y. Rotating Bending Fatigue Behavior of AlSi10Mg Fabricated by Powder Bed Fusion-Laser Beam: Effect of Layer Thickness. Crystals (Basel). 2025, 15, 422. [Google Scholar]

- Aghayar, Y.; Behvar, A.; Haghshenas, M.; Mohammadi, M. Rotating Bending Fatigue of Laser Powder Bed Fused 316L Stainless Steel at Various Stress Levels: Microstructural Evaluation and Predictive Modeling. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 2025, 48, 783–796. [Google Scholar]

- Behvar, A.; Aghayar, Y.; Avateffazeli, M.; Tridello, A.; Benelli, A.; Paolino, D.S.; et al. Synergistic impact of corrosion pitting on the rotating bending fatigue of additively manufactured 316L stainless steel: Integrated experimental and modeling analyses. Int J Fatigue. 2024, 188, 108491. [Google Scholar]

- Leuders, S.; Thöne, M.; Riemer, A.; Niendorf, T.; Tröster, T.; Richard, H.A.; et al. On the mechanical behaviour of titanium alloy TiAl6V4 manufactured by selective laser melting: Fatigue resistance and crack growth performance. Int J Fatigue. 2013, 48, 300–307. [Google Scholar]

- Leuders, S.; Vollmer, M.; Brenne, F.; Tröster, T.; Niendorf, T. Fatigue Strength Prediction for Titanium Alloy TiAl6V4 Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A. 2015, 46, 3816–3823. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Pan, Q.; Huang, H.; Feng, L.; Wang, Y. Influence of grain structure and crystallographic orientation on fatigue crack propagation behavior of 7050 alloy thick plate. Int J Fatigue. 2014, 66, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.W.; Liu, A.; Wang, X.S. The influence of building direction on the fatigue crack propagation behavior of Ti6Al4V alloy produced by selective laser melting. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2019, 767, 138409. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Pan, S.P.; Zhou, M.Z.; Yi, D.Q.; Xu, D.Z.; Xu, Y.F. Effects of inclusions, grain boundaries and grain orientations on the fatigue crack initiation and propagation behavior of 2524-T3 Al alloy. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2013, 580, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Konecna, R.; Varmus, T.; Nicoletto, G.; Jambor, M. Influence of Build Orientation on Surface Roughness and Fatigue Life of the Al2024-RAM2 Alloy Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF). Metals (Basel). 2023, 13, 1615. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, G.; Li, Y.; Paolino, D.S.; Tridello, A.; Berto, F.; Hong, Y. Very-high-cycle fatigue behavior of Ti-6Al-4V manufactured by selective laser melting: Effect of build orientation. Int J Fatigue. 2020, 136, 105628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadimi, H.; Jirandehi, A.P.; Nemati, S.; Ding, H.; Garbie, A.; Raush, J.; et al. Effects of Printing Layer Orientation on the High-Frequency Bending-Fatigue Life and Tensile Strength of Additively Manufactured 17-4 PH Stainless Steel. Materials. 2023, 16, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwanpreecha, C.; Manonukul, A. On the build orientation effect in as-printed and as-sintered bending properties of 17-4PH alloy fabricated by metal fused filament fabrication. Rapid Prototyp J. 2022, 28, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanpreecha, C.; Manonukul, A. On the build orientation effect in as-printed and as-sintered bending properties of 17-4PH alloy fabricated by metal fused filament fabrication. Rapid Prototyp J. 2022, 28, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; He, X.; Wu, B.; Dang, L.; Xin, H.; Li, Y. Anisotropic fatigue performance of directed energy deposited Ti-6Al-4V: Effects of build orientation. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2023, 876, 145112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milella, P.P. Fatigue and Corrosion in Metals. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2024.

- Rogers, J.; Elambasseril, J.; Wallbrink, C.; Krieg, B.; Qian, M.; Brandt, M.; et al. The impact of surface orientation on surface roughness and fatigue life of laser-based powder bed fusion Ti-6Al-4V. Addit Manuf. 2024, 85, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croccolo, D.; De Agostinis, M.; Fini, S.; Olmi, G.; Vranic, A.; Ciric-Kostic, S. Influence of the build orientation on the fatigue strength of EOS maraging steel produced by additive metal machine. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 2016, 39, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morettini, G.; Razavi, N.; Zucca, G. Effects of build orientation on fatigue behavior of Ti-6Al-4V as-built specimens produced by direct metal laser sintering. Procedia Structural Integrity. 2019, 24, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

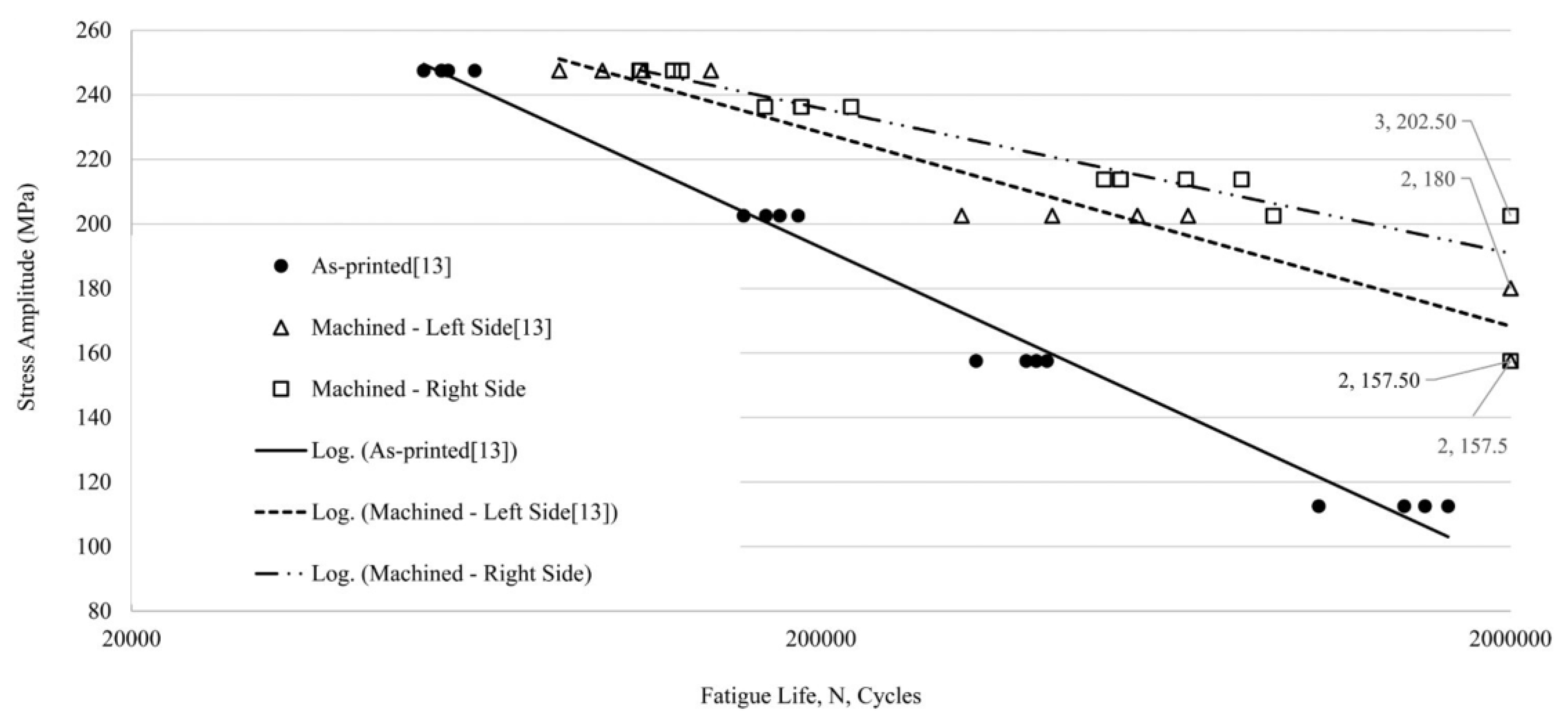

- Wood, P.; Libura, T.; Kowalewski, Z.L.; Williams, G.; Serjouei, A. Influences of Horizontal and Vertical Build Orientations and Post-Fabrication Processes on the Fatigue Behavior of Stainless Steel 316L Produced by Selective Laser Melting. Materials. 2019, 12, 4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; et al. The anisotropy of high cycle fatigue property and fatigue crack growth behavior of Ti–6Al–4V alloy fabricated by high-power laser metal deposition. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2022, 853, 143745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaei, R.; Fatemi, A. Fatigue performance of additive manufactured metals under variable amplitude service loading conditions including multiaxial stresses and notch effects: Experiments and modelling. Int J Fatigue. 2021, 145, 106002. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, S.N.; Walley, S.M. The Hall–Petch and inverse Hall–Petch relations and the hardness of nanocrystalline metals. J Mater Sci. 2020, 55, 2661–2681. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, T.; Zhang, X.; Flood, A.; Karnati, S.; Li, W.; Newkirk, J.; et al. Effect of processing parameters and build orientation on microstructure and performance of AISI stainless steel 304L made with selective laser melting under different strain rates. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2022, 835, 142686. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Ma, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, W.; Qian, X. Effects of build direction on tensile and fatigue performance of selective laser melting Ti6Al4V titanium alloy. Int J Fatigue. 2020, 130, 105260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Liu, S.; Murdoch, H.A.; Smith, P.M. Investigating build orientation-induced mechanical anisotropy in additive manufacturing 316L stainless steel. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2023, 880, 145308. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Miller, J.; Vezza, J.; Mayster, M.; Raffay, M.; Justice, Q.; et al. Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors. 2024, 24, 2668. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Y.-S.; Kwok, T.-H.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.C.L.; Chen, Y. Challenges and Status on Design and Computation for Emerging Additive Manufacturing Technologies. J Comput Inf Sci Eng. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranić, A.; Bogojević, N.; Kostić, Ć.; Croccolo, D.; Olmi, G. IMK-14-Research & Development in Heavy Machinery. 2017, 23, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liou, F. Introduction to additive manufacturing. Addit Manuf. Elsevier; 2021. p. 1–31.

- Piscopo, G.; Atzeni, E.; Saboori, A.; Salmi, A. An Overview of the Process Mechanisms in the Laser Powder Directed Energy Deposition. Applied Sciences. 2022, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Pillay, S.; Ning, H. Post-Process Treatments for Additive-Manufactured Metallic Structures: A Comprehensive Review. J Mater Eng Perform. 2023, 32, 7073–7122. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, K.A.; Kanakana-Katumba, M.G.; Maladzhi, R.W. A Review of Additive Manufacturing Post-Treatment Techniques for Surface Quality Enhancement. Procedia CIRP. 2023, 120, 404–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, A.W.; Mali, H.S.; Meena, A.; Puerta, A.P.V.; Kunkel, M.E. Surface characteristics improvement methods for metal additively manufactured parts: A review. Advances in Materials and Processing Technologies. 2022, 8, 4524–4563. [Google Scholar]

- Kahlin, M.; Ansell, H.; Basu, D.; Kerwin, A.; Newton, L.; Smith, B.; et al. Improved fatigue strength of additively manufactured Ti6Al4V by surface post processing. Int J Fatigue. 2020, 134, 105497. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, L.; Gaur, V. Different post-processing methods to improve fatigue properties of additively built Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Int J Fatigue. 2023, 176, 107850. [Google Scholar]

- Balachandramurthi, A.R.; Moverare, J.; Dixit, N.; Pederson, R. Influence of defects and as-built surface roughness on fatigue properties of additively manufactured Alloy 718. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2018, 735, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkin, D.B.; Patel, D.N.; Helvajian, H.; Steffeney, L.; Diaz, A. Surface Treatment of Powder-Bed Fusion Additive Manufactured Metals for Improved Fatigue Life. J Mater Eng Perform. 2019, 28, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaei, N.; Fatemi, A. Analysis of the effect of surface roughness on fatigue performance of powder bed fusion additive manufactured metals. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics. 2020, 108, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitemeier, D.; Dalle Donne, C.; Syassen, F.; Eufinger, J.; Melz, T. Effect of surface roughness on fatigue performance of additive manufactured Ti–6Al–4V. Materials Science and Technology. 2016, 32, 629–634. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Pegues, J.W.; Mahjouri-Samani, M.; Shamsaei, N. Laser polishing for improving fatigue performance of additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V parts. Opt Laser Technol. 2021, 134, 106639. [Google Scholar]

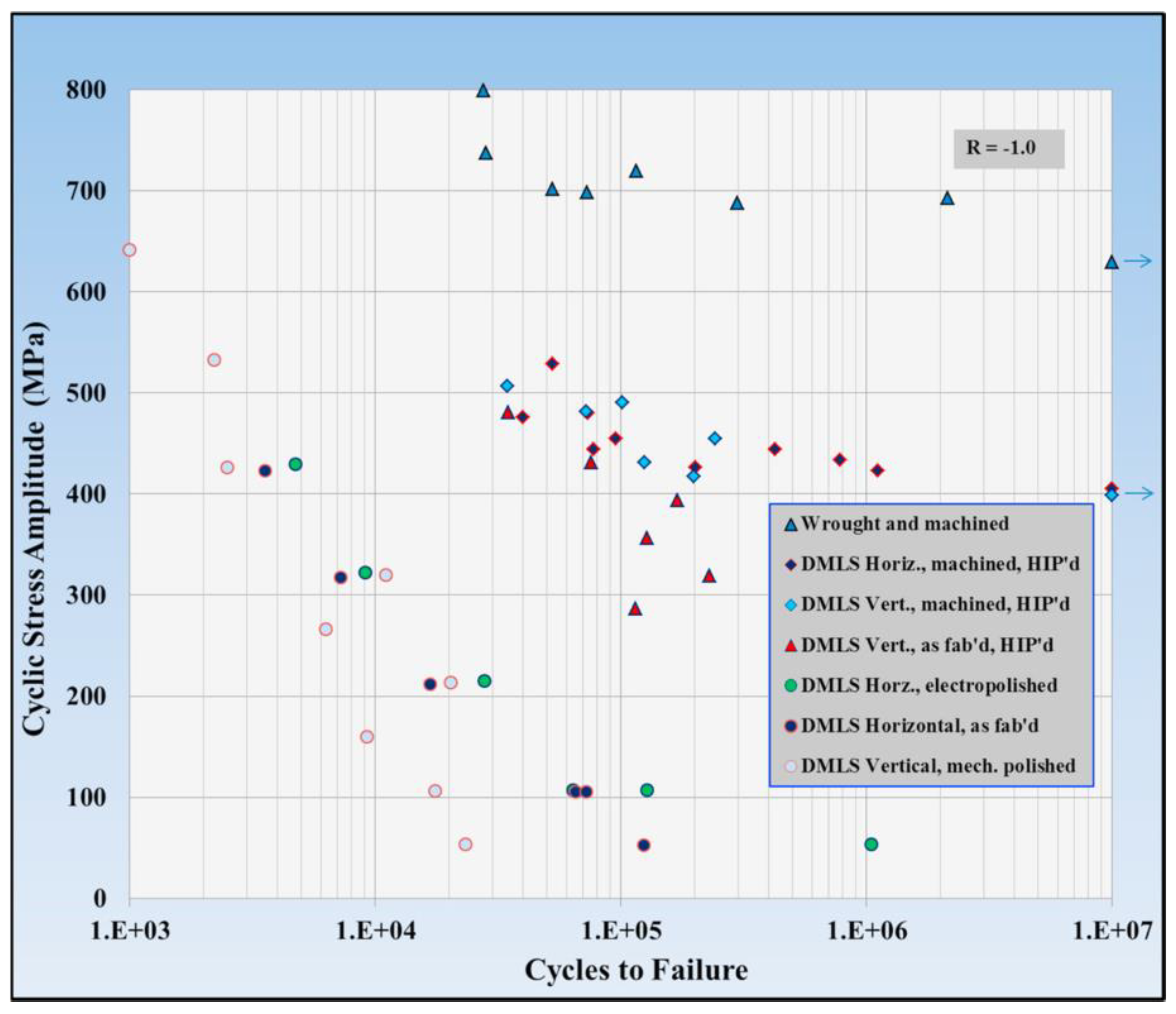

- Mower, T.M.; Long, M.J. Mechanical behavior of additive manufactured, powder-bed laser-fused materials. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2016, 651, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hassanin, A.; Scherillo, F.; Obeidi, M.A. Rotating Bending Fatigue Behavior of Additively Manufactured Ti6Al4V Specimens Subjected to CO2 Laser Polishing. J Mater Eng Perform. 2025, 34, 13452–13460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, M.; Masuo, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Murakami, Y. Effect of Surface Roughness on Fatigue Strength of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy Manufactured by Additive Manufacturing. Procedia Structural Integrity. 2019, 19, 294–301. [Google Scholar]

- Parvez, M.M.; Patel, S.; Isanaka, S.P.; Liou, F. A Novel Laser-Aided Machining and Polishing Process for Additive Manufacturing Materials with Multiple Endmill Emulating Scan Patterns. Applied Sciences. 2021, 11, 9428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayazfar, H.; Sharifi, J.; Keshavarz, M.K.; Ansari, M. An overview of surface roughness enhancement of additively manufactured metal parts: A path towards removing the post-print bottleneck for complex geometries. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2023, 125, 1061–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaghazardi, Z.; Wüthrich, R. Review—Electropolishing of Additive Manufactured Metal Parts. J Electrochem Soc. 2022, 169, 043510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, H.; Elshaer, A.; Benhadj-Djilali, R.; Modica, F.; Fassi, I. Surface Finish Improvement of Additive Manufactured Metal Parts. 2018. p. 145–64.

- Tyagi, P.; Goulet, T.; Riso, C.; Stephenson, R.; Chuenprateep, N.; Schlitzer, J.; et al. Reducing the roughness of internal surface of an additive manufacturing produced 316 steel component by chempolishing and electropolishing. Addit Manuf. 2019, 25, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, P.; Brent, D.; Saunders, T.; Goulet, T.; Riso, C.; Klein, K.; et al. Roughness Reduction of Additively Manufactured Steel by Electropolishing. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2020, 106, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, A. Investigation of surface roughness post-processing of additively manufactured nickel-based superalloy Hastelloy X using electropolishing. Surf Coat Technol. 2022, 441, 128529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Tang, Z.; Lu, W.; Wang, S.; Yi, M. Modeling and Prediction of Fatigue Properties of Additively Manufactured Metals. Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica. 2023, 36, 181–213. [Google Scholar]

- Serjouei, A.; Afazov, S. Predictive model to design for high cycle fatigue of stainless steels produced by metal additive manufacturing. Heliyon. 2022, 8, e11473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalalahmadi, B.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Vechart, A.; Weinzapfel, N. An Integrated Computational Materials Engineering Predictive Platform for Fatigue Prediction and Qualification of Metallic Parts Built With Additive Manufacturing. J Tribol. 2021, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, R.; Hosseini-Toudeshky, H.; Sadighi, M.; Mohammadi-Aghdam, M.; Zadpoor, A.A. Computational prediction of the fatigue behavior of additively manufactured porous metallic biomaterials. Int J Fatigue. 2016, 84, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y. A reliability-based fatigue design for mechanical components under material variability. Qual Reliab Eng Int. 2020, 36, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.; Raju, N.; Raghavan, N.; Rosen, D.W.; Kim, S. Bayesian inference-based decision of fatigue life model for metal additive manufacturing considering effects of build orientation and post-processing. Int J Fatigue. 2022, 155, 106535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghihi, D.; Sarkar, S.; Naderi, M.; Rankin, J.E.; Hackel, L.; Iyyer, N. A Probabilistic Design Method for Fatigue Life of Metallic Component. ASCE-ASME Journal of Risk and Uncertainty in Engineering Systems, Part B: Mechanical Engineering. 2018, 4.

- Hristopulos, D.; Petrakis, M.; Kaniadakis, G. Weakest-Link Scaling and Extreme Events in Finite-Sized Systems. Entropy. 2015, 17, 1103–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Bahn, C. Uncertainty Evaluation of Weibull Estimators through Monte Carlo Simulation: Applications for Crack Initiation Testing. Materials. 2016, 9, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y. Fatigue property prediction of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V using probabilistic physics-guided learning. Addit Manuf. 2021, 39, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awd, M.; Saeed, L.; Walther, F. Atomistic-Based Fatigue Property Normalization Through Maximum A Posteriori Optimization in Additive Manufacturing. Materials. 2025, 18, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gbagba, S.; Maccioni, L.; Concli, F. Advances in Machine Learning Techniques Used in Fatigue Life Prediction of Welded Structures. Applied Sciences. 2023, 14, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; He, X.; Tang, D.; Dang, L.; Li, A.; Xia, Q.; et al. Recent developments and future trends in fatigue life assessment of additively manufactured metals with particular emphasis on machine learning modeling. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 2023, 46, 4425–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; Hu, W.; Meng, Q. Data-driven fatigue life prediction in additive manufactured titanium alloy: A damage mechanics based machine learning framework. Eng Fract Mech. 2021, 252, 107850. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Ali, M.d.H.; Malik, A.W.; Mahmood, M.A.; Liou, F. Physics-Based Machine Learning Framework for Predicting Structure-Property Relationships in DED-Fabricated Low-Alloy Steels. Metals (Basel). 2025, 15, 965. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Ali, H.; Mahmood, M.A.; Malik, A.W.; Liou, F. A MACHINE LEARNING MODEL TO PREDICT MECHANICAL PROPERTY OF DIRECTED ENERGY DEPOSTION PROCESSED LOW ALLOY STEELS.

- Hasan, F.; Hamrani, A.; Rayhan, M.M.; Dolmetsch, T.; McDaniel, D.; Agarwal, A. Precision Calibration in Wire-Arc-Directed Energy Deposition Simulations Using a Machine-Learning-Based Multi-Fidelity Model. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2024, 8, 222. [Google Scholar]

- Rayhan, M.M.; Hamrani, A.; Hasan, F.; Dolmetsch, T.; Agarwal, A.; McDaniel, D. Dynamic Dwell Time Adjustment in Wire Arc-Directed Energy Deposition: A Thermal Feedback Control Approach. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025, 9, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, H.; Wu, S.; Wu, Z.; Kang, G.; Peng, X.; Withers, P.J. A machine-learning fatigue life prediction approach of additively manufactured metals. Eng Fract Mech. 2021, 242, 107508. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, C.-N.; Zhang, X.; Goh, P.C.; Wei, J.; Hardacre, D.; et al. High cycle fatigue life prediction of laser additive manufactured stainless steel: A machine learning approach. Int J Fatigue. 2019, 128, 105194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Qian, G.; Hong, Y. Machine learning based very-high-cycle fatigue life prediction of AlSi10Mg alloy fabricated by selective laser melting. Int J Fatigue. 2023, 171, 107585. [Google Scholar]

- Horňas, J.; Běhal, J.; Homola, P.; Senck, S.; Holzleitner, M.; Godja, N.; et al. Modelling fatigue life prediction of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V samples using machine learning approach. Int J Fatigue. 2023, 169, 107483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadimi, H.; Jirandehi, A.P.; Nemati, S.; Guo, S. Small-sized specimen design with the provision for high-frequency bending-fatigue testing. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 2021, 44, 3517–3537. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, G.; Brenne, F.; Niendorf, T.; Mittelstedt, C. Influence of the Miniaturisation Effect on the Effective Stiffness of Lattice Structures in Additive Manufacturing. Metals (Basel). 2020, 10, 1442. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletto, G. Fatigue Behavior of L-PBF Metals: Cost-Effective Characterization via Specimen Miniaturization. J Mater Eng Perform. 2021, 30, 5227–5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.W.; Zhang, B.; Feng, X.; Song, Z.M.; Qi, X.B.; Li, C.P.; et al. Pore-affected fatigue life scattering and prediction of additively manufactured Inconel 718: An investigation based on miniature specimen testing and machine learning approach. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2021, 802, 140693. [Google Scholar]

- Parvez, M.M.; Chen, Y.; Karnati, S.; Coward, C.; Newkirk, J.W.; Liou, F. A Displacement Controlled Fatigue Test Method for Additively Manufactured Materials. Applied Sciences. 2019, 9, 3226. [Google Scholar]

- Parvez, M.M.; Pan, T.; Chen, Y.; Karnati, S.; Newkirk, J.W.; Liou, F. High Cycle Fatigue Performance of LPBF 304L Stainless Steel at Nominal and Optimized Parameters. Materials. 2020, 13, 1591. [Google Scholar]

- Witkin, D.B.; Patel, D.N.; Bean, G.E. Notched fatigue testing of Inconel 718 prepared by selective laser melting. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 2019, 42, 166–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zancato, E.; Leonetti, D.; Meneghetti, G.; Maljaars, J. Experimental evaluation of the fatigue notch factor in as-built specimens produced by Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing. Procedia Structural Integrity. 2024, 53, 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, A.; Pegues, J.; Kelly, M.; Shao, S.; Shamsaei, N. Fatigue behavior of additively manufactured edge notched specimens. Int J Mech Sci. 2025, 296, 110315. [Google Scholar]

- Kahlin, M.; Ansell, H.; Moverare, J.J. Fatigue behaviour of notched additive manufactured Ti6Al4V with as-built surfaces. Int J Fatigue. 2017, 101, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Beretta, S. Extremes 2:2. 1999.

- Akiniwa, Y.; Stanzltschegg, S.; Mayer, H.; Wakita, M.; Tanaka, K. Fatigue strength of spring steel under axial and torsional loading in the very high cycle regime. Int J Fatigue. 2008, 30, 2057–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, M.; Łagoda, T. Comparison of the fatigue characteristics for some selected structural materials under bending and torsion. Materials Science. 2011, 47, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotwinski, J.; Moylan, S. Applicability of Existing Materials Testing Standards for Additive Manufacturing Materials. Gaithersburg, MD; 2014 Jun.

- Rogers, J.; Qian, M.; Elambasseril, J.; Burvill, C.; Brice, C.; Wallbrink, C.; et al. Fatigue test data applicability for additive manufacture: A method for quantifying the uncertainty of AM fatigue data. Mater Des. 2023, 231, 111978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Printing Parameter | Power (W) | Scanning Speed (mm/s) |

% Porosity | Circularity Avg. |

Number of Defects | Avg. dia. (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P3 Keyhole | 370 | 800 | 0.385 ± 0.004 | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 3861 | 29 |

| P5 Process Window | 370 | 1400 | 0.106 ± 0.012 | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 1363 | 32 |

| P8 Lack of Fusion | 370 | 2000 | 0.215 ± 0.046 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 2708 | 26 |

| EOS Nominal | 280 | 1200 | 0.008 ± 0.004 | 0.66 ± 0.06 | 231 | 22 |

| EOS Nominal Improved | 280 | 1200 | 0.017 ± 0.012 | 0.57 ± 0.05 | 143 | 19 |

| Nominal Contour Strategy | Improved Contour Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contour 1 | Contour 2 | Contour 1 | Contour 2 | Contour 3 | |

| Contour Offset (micron) | 20 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 |

| Laser Power (W) | 150 | 150 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Scanning Speed (mm/s) | 1250 | 1250 | 450 | 450 | 550 |

| Surface Roughness (micron) | 15 | 7 | |||

| References | Process parameters used | Materials Tested & process | Observed Defects/Surface Output | Bending Fatigue Performance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Power | Scanning Speed (mm/sec) | Hatch offset, mm | Powder Particle Size/Layer thick, µm | ||||

| [52] | 370J, 280J | 800,1400, 1200,2000 |

Scanning direction altered | D10=26.4 µm, 55µm D50=37.2µm, 76µm D90=57.4µm, 106µm |

Ti-6Al-4V LPBF, EPBF |

Keyhole porosity, Lack of fusion porosity |

1. High laser power, low scanning speed affected fatigue life 2. Fatigue performance improved by optimizing scan strategy |

| [59] | 370 Watt | 1300 | 0.19 | LT=50, 80 µm, | AlSi10Mg LPBF |

1. 80µm layer caused larger LOF pores and high roughness, 2. 50µm has few and small defects |

1. 50µm showed higher rotating bending fatigue limit (70-80 MPa at 10^8 cycles compared to 80 µm (15-25MPa) |

| [60,61] | 370 Watt | 1350 | 0.09 | LT=50 µm | SS316L LPBF |

1. Lack of Fusion porosity with size 113 µm for pre corroded and 141µm for corroded specimen 2. Surface degradation with pronounced crevices and pits due to corrosion |

1. Corrosion bending fatigue test was performed. Pre-corroded specimens show about 20% reduction in fatigue life than the non-corroded one. 2. Fatigue strength was found for corroded and pre-corroded as 203 and 243 MPa respectively |

| [62,63] | 400Watt | Particle size = 40µm LT = 30µm |

Ti-6Al-4V SLM |

1. Gas pores, LOF pores 2. Anisotropic columnar grains |

1. Pores have a drastic effect on the fatigue behavior at high-cycle fatigue regimes. 2. Significant fatigue life variation between as built and heat-treated specimen due to removing residual stress. 3. Mean fatigue life increased from 27000 cycles to 93,000 cycles by stress relieving |

||

| References | Build Orientation | Materials Tested | AM Process | Bending Fatigue Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [67] | 0°, 45° and 90° | Al2024-RAM2 | Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) |

1. 0° orientation showed lower roughness and the highest fatigue strength. 2. 45° and 90° had almost similar fatigue life as roughness was almost same. |

| [68] | 0°, 45° and 90° | Ti-6Al-4V | LPBF (SLM) |

1.Due to significant anisotropic characteristics, fatigue strength was reduced by around 40% when build orientation changed from 0 to 90 degree. 2. Favorable orientation was identified as 0° due to developing columnar grains against crack propagation thereby enhancing fatigue life. |

| [69] | Horizontal(0°) & Vertical (90°) | SS 17-4PH | Atomic diffusion AM (ADAM) | 1. Vertically oriented specimens experienced lower ductility and lower fatigue life than horizontally oriented specimens. 2. Vertically oriented specimens had poor quality with large pores due to lack of sintering that mainly extended towards the layer boundaries. |

| [70] | Flat, On edge and upright orientation | SS17-4PH alloy | Metal fused filament fabrication (MFFF) | 1. On-edge orientation displayed lower bending strength than flat orientation due to the creation of a sliding action by Poisson’s effect. This sliding action results in highly deformed and shifted voids towards the edge. 2. Upright orientation had higher bending strain and lower strength and limited plasticity as well. |

| [71] | Parallel (x-y) &perpendicular (x-z) | AlSi10Mg alloy | SLM | 1. At very high cycle fatigue (VHCF) regimes, the bending strength of the horizontally built specimens is higher than that of the vertically oriented parts due to microstructural effects while larger defect sizes were observed in the vertically fabricated parts. |

| [72] | X, Y and Z (Build direction) | Ti-6Al-4V | DED | 1. The mean fatigue life (logarithmic) in X and Y direction was almost twice that the fatigue life of the specimen built in the Z direction |

| References | Post processing/surface treatment applied | Material and Process | Type of fatigue test | Usefulness and improvements in fatigue performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [92] | 1. Shot Peening (SP) 2. Laser shock Peening (LSP) 3. Centrifugal Finishing (CF) 4. Laser Polishing (LP) 5. Linishing (Lin) 6. Hot Iso-static Pressing (HIP) |

Ti-6Al-4V EPBF & LPBF |

Rotating Bending | 1. Fatigue life was increased by around 100-125% with CF, SP and Lin post processing compared to as built 2. Laser shock peening was observed increase fatigue life by around 5-20% 3. But laser polishing reduced fatigue life instead due to formation of high surface roughness 4. Stress relieved LPBF samples showed higher strength than EPBF HIPPED specimens |

| [93] | 1. Heat Treatment 2. HIP |

Ti-6Al-4V alloy, LPBF | Axial | 1. Fatigue strength was improved by three times when compared to as built by applying Heat treatment 2. HT+HIP increased fatigue properties by five times |

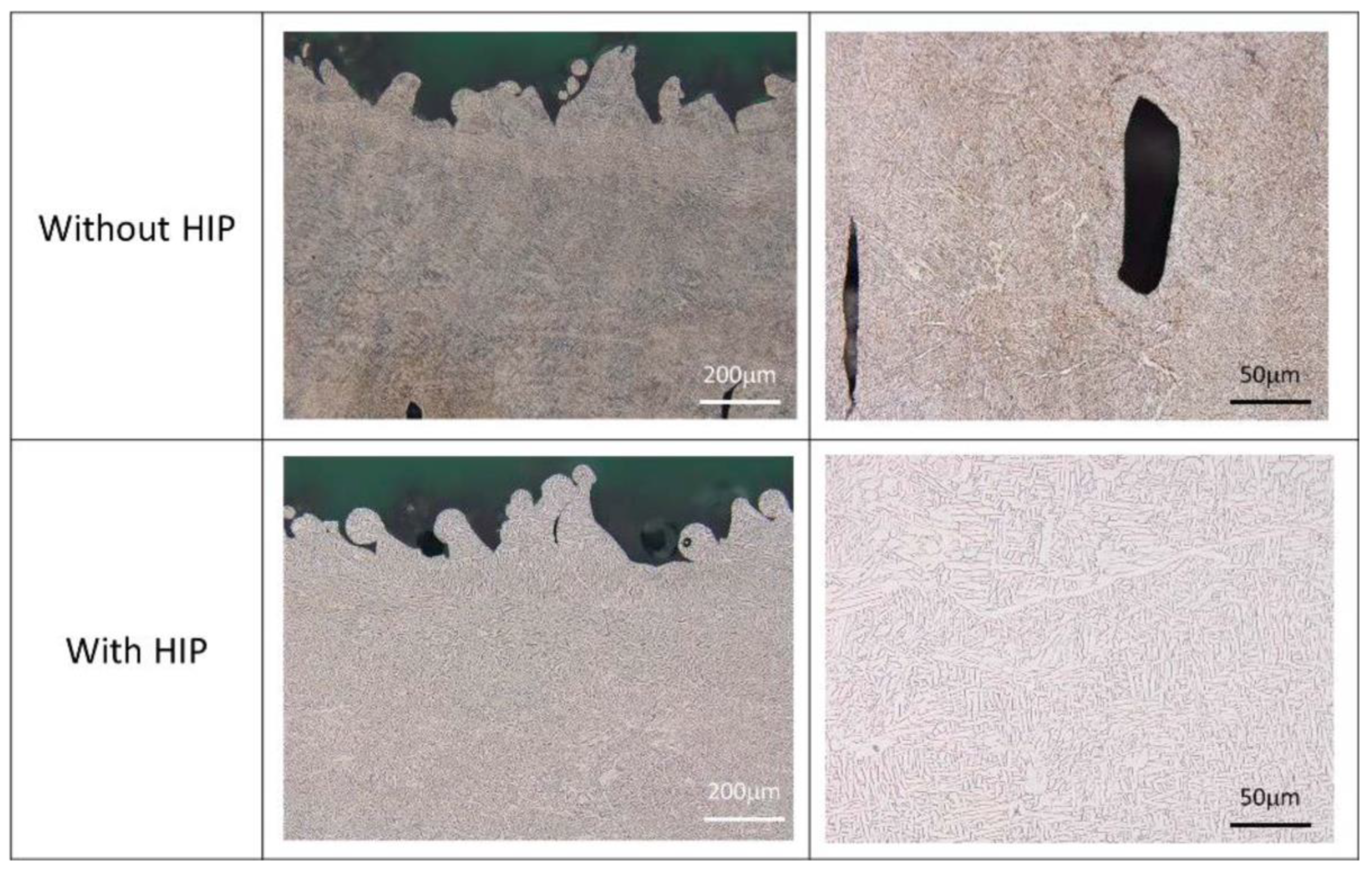

| [94] | 1. Machining 2. Hot Iso-static Pressing (HIP) |

718 alloy, EBM and SLM |

4-point bending | 1. Machined specimens had lower surface roughness and higher fatigue life, but large scatter observed due to large number of crack initiation sites. 2. HIP treatment significantly reduced the number of defects and improved fatigue life |

| [95] | 1. Vibratory polishing 2. Laser surface remelting (LSR) 3. Abrasive polishing |

Ti-6Al-4V &Inconel 625 EBM and SLM |

High Cycle Fatigue Test | 1. Both Vibratory and chemical finishing improved fatigue life by 3-5 times for Ti-6Al-4V 2. LSR and abrasive polishing didn’t improve fatigue life of Inconel 625 alloy significantly due to existing defects despite smoother surfaces |

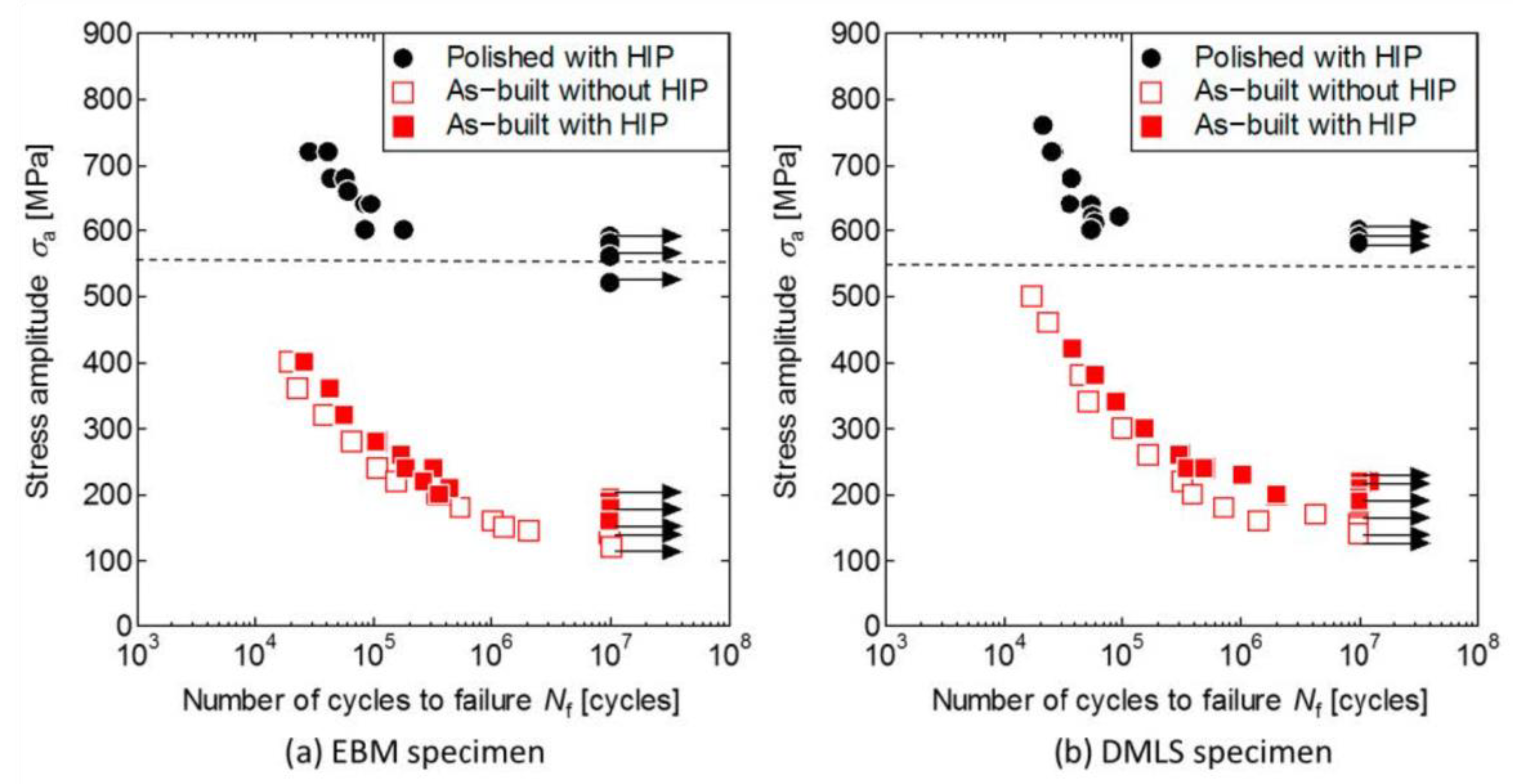

| [96,97] | 1. Hot Iso-static Pressing (HIP) | Ti-6Al-4V LPBF DMLS |

Axial | 1. Internal defects can be minimized by HIP without affecting surface roughness 2. Fatigue life was decreased significantly with the increase of Arithmetic mean surface roughness |

| [98] | 1. Laser Polishing 2. Stress-Relief |

Ti-6Al-4V LPBF |

Fully Reverse Bending, R=-1 | 1. Laser polished specimens exhibited longer fatigue life cycle compared to as built by decreasing surface roughness due to remelting of the partially melted powdered particles. 2. Stress Relief process helped improve fatigue strength at low cycle zones |

| [99] | 1. Electro chemical polishing 2. Mechanical Polishing 3. Machined (Round specimen) 4. HIP |

AlSi10Mg SLM Ti-6Al-4V DMLS 316L &17-4PH |

Fully Reverse Rotating Bending, R=-1 | 1. SLM AlSi10Mg showed 60% higher strength than that of conventional Al6061 2. Post treatment process did not effectively enhance fatigue strength due to high number of defects, pores etc. 3. DMLS fabricated stainless steels showed 85%-95% of the fatigue strength of wrought steels 4. HIP process improved fatigue strength of DMLS 316L in the high cycle regimes only |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).