Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

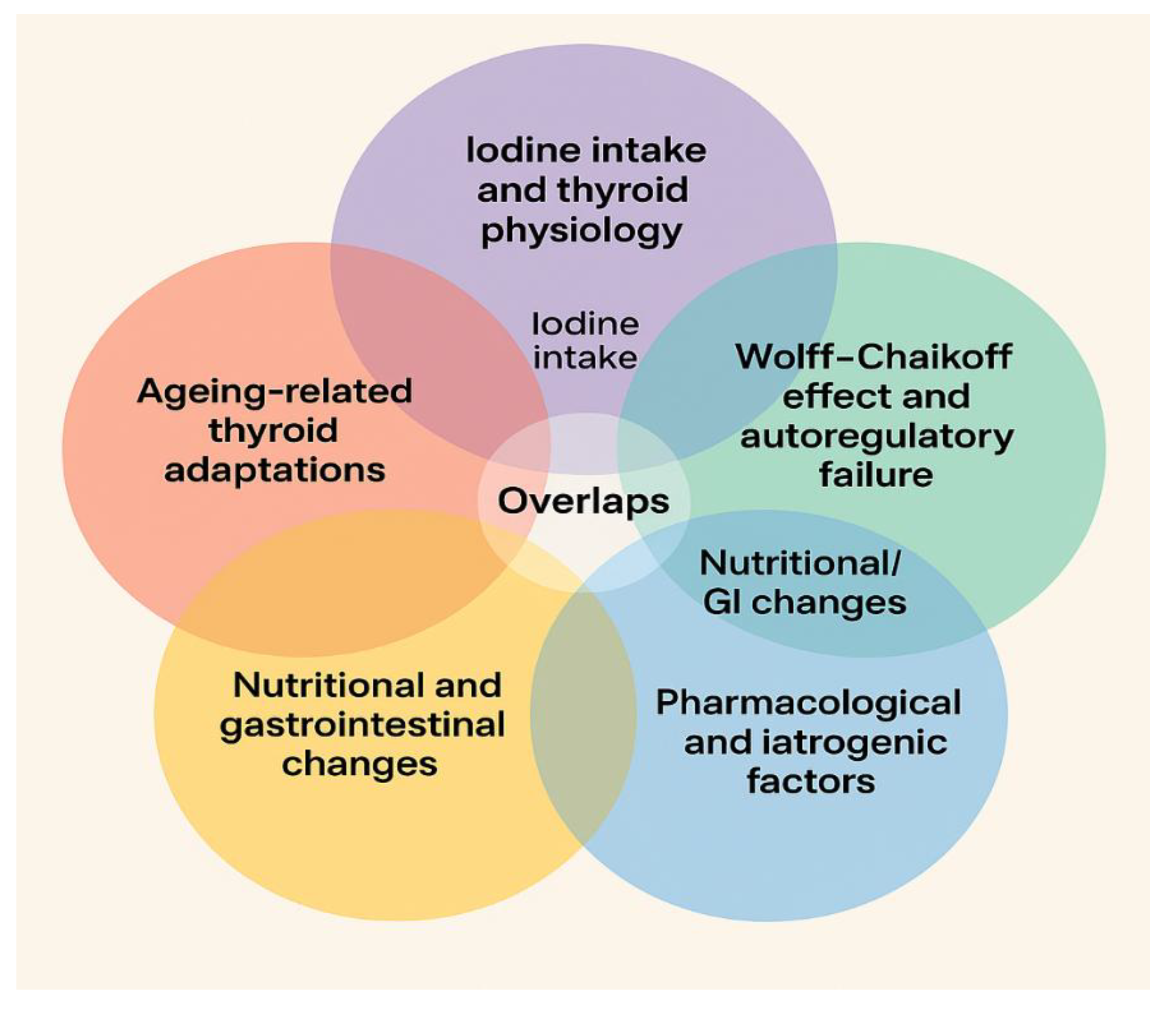

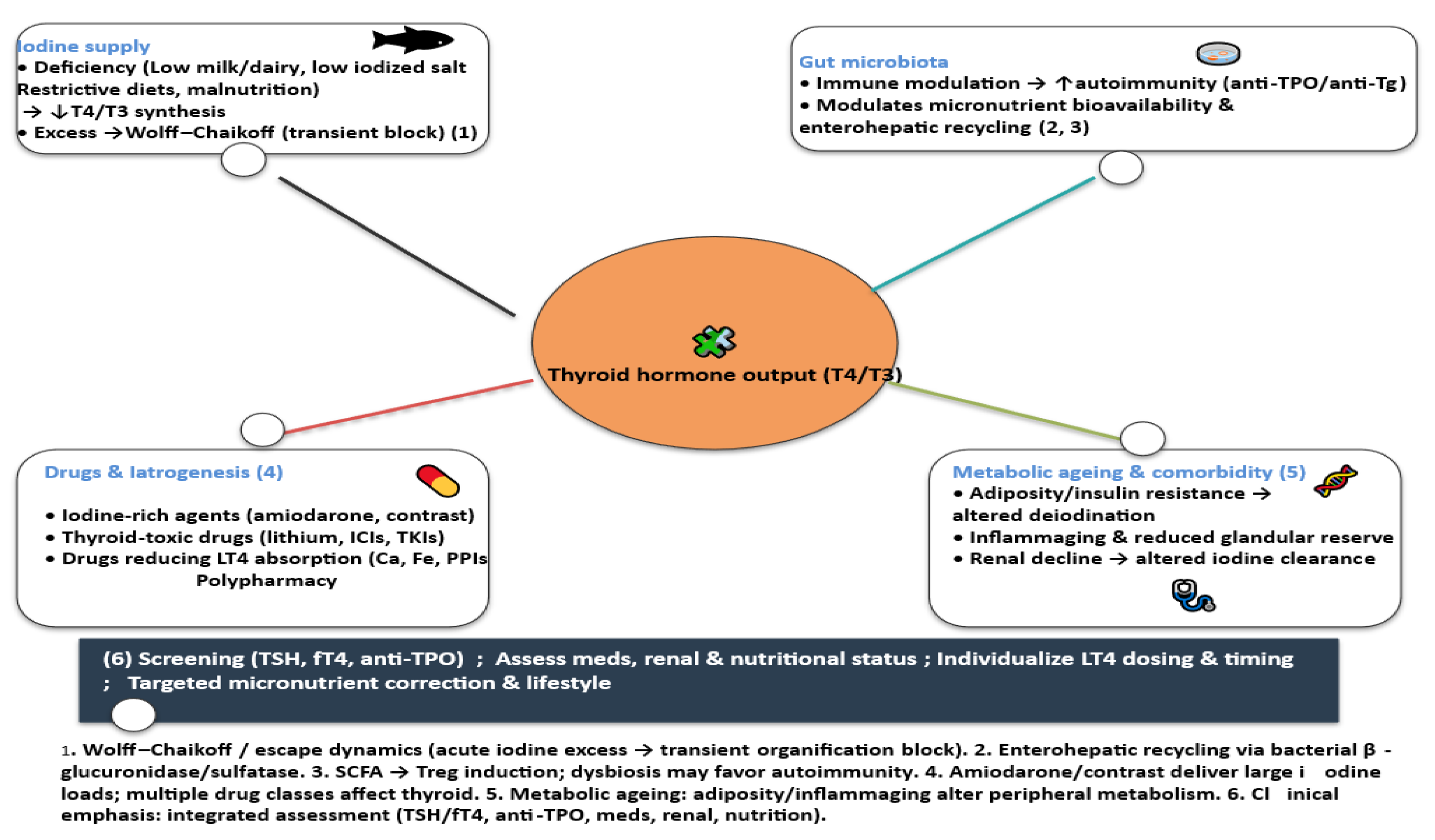

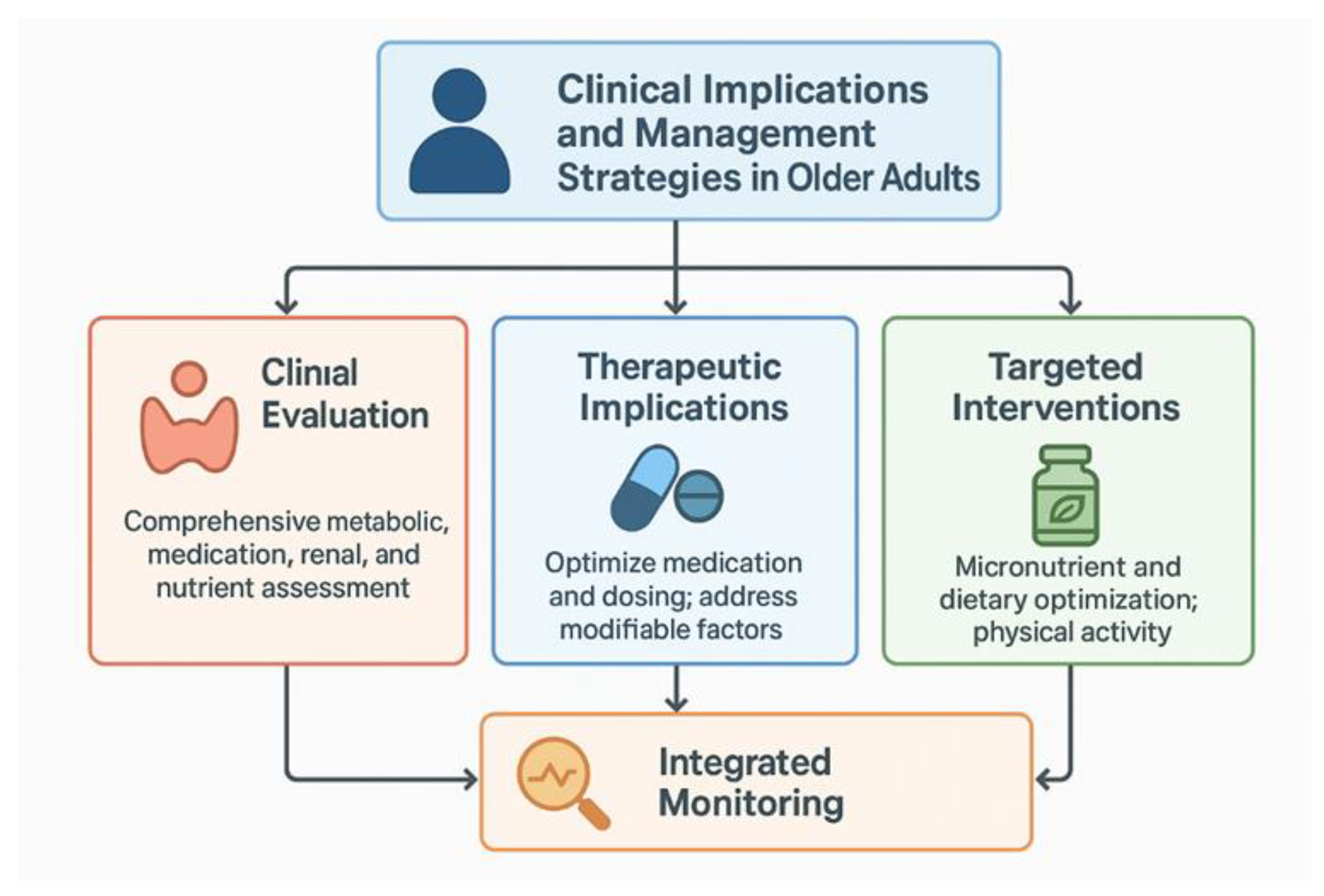

Background/Objectives: Iodine intake demonstrates a U-shaped relationship with thyroid dysfunction, with both deficiency and excess contributing to adverse outcomes. Older adults are especially susceptible due to age-related alterations in thyroid physiology, reduced functional reserve, impaired adaptation to iodine excess, comorbidities, and polypharmacy. This review aims to synthesize evidence on how ageing influences iodine–thyroid interactions and to identify factors that complicate clinical management in older populations. Methods: A narrative review of the literature was conducted, focusing on studies addressing iodine metabolism, thyroid function, and the modifying roles of gut microbiota, nutrient cofactors, pharmacological exposures, renal function, and metabolic ageing in older adults. Results: Ageing affects iodine handling and thyroid function through multiple mechanisms. Dysbiosis may contribute to thyroid autoimmunity and hormone metabolism via immune modulation, micronutrient utilization, and enterohepatic recycling. Declining renal clearance prolongs iodide retention, while the frequent use of amiodarone, iodinated contrast, lithium, and medications interfering with levothyroxine absorption increases iatrogenic risk. Concurrent metabolic changes—such as adiposity, insulin resistance, and chronic low-grade inflammation—further impair iodine utilization and thyroid hormone action. Conclusions: Recognition of the complex interactions between ageing, iodine metabolism, and thyroid function is essential for accurate diagnosis and individualized management in older adults. Strategies should incorporate age-adjusted reference ranges, systematic medication review, micronutrient optimization, and iodine prophylaxis policies compatible with salt-reduction initiatives. Emerging microbiome-targeted interventions warrant further investigation as potential modulators of iodine–thyroid dynamics in ageing populations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A Comprehensive Literature Search

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- The impact of iodine deficiency or excess on thyroid function in adults ≥60 years,

- Age-specific physiological changes in thyroid hormone regulation,

- Gut microbiota interactions with thyroid autoimmunity or hormone metabolism,

- Nutrient cofactors relevant to thyroid function (selenium, zinc, iron),

- Pharmacological exposures (iodine-rich or thyroid-disrupting drugs, absorption modifiers),

- Epidemiological or clinical data relevant to iodine status in Romania.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Romania as Case Example

3.2. Why Focus on Older Adults

3.3. Age-Related Thyroid Physiology and Iodine-Related Pathophysiology

3.3.1. Iodine’s Role in Thyroid Hormone Synthesis

3.3.2. Age-Specific Thyroid Physiology

- Altered hypothalamic–pituitary set-point — possible reduced sensitivity of hypothalamic thyrotropin -releasing hormon (TRH) neurons and/or pituitary thyrotrophs to circulating free T4 [77]

- Reduced TSH bioactivity — some studies suggest changes in glycosylation patterns that may make TSH less biologically potent, thus requiring higher serum levels to achieve the same thyroidal stimulation [78]

- Adaptive or benign physiological change — higher TSH in elderly may reflect a homeostatic adaptation to slow metabolism and reduced tissue demand for thyroid hormones, not necessarily pathological hypothyroidism

3.3.3. The Wolff–Chaikoff Effect

3.4. The U-Shaped Curve: Deficiency and Excess as Dual Hazards

3.5. Modifiers of Iodine Status and Thyroid Function in Ageing

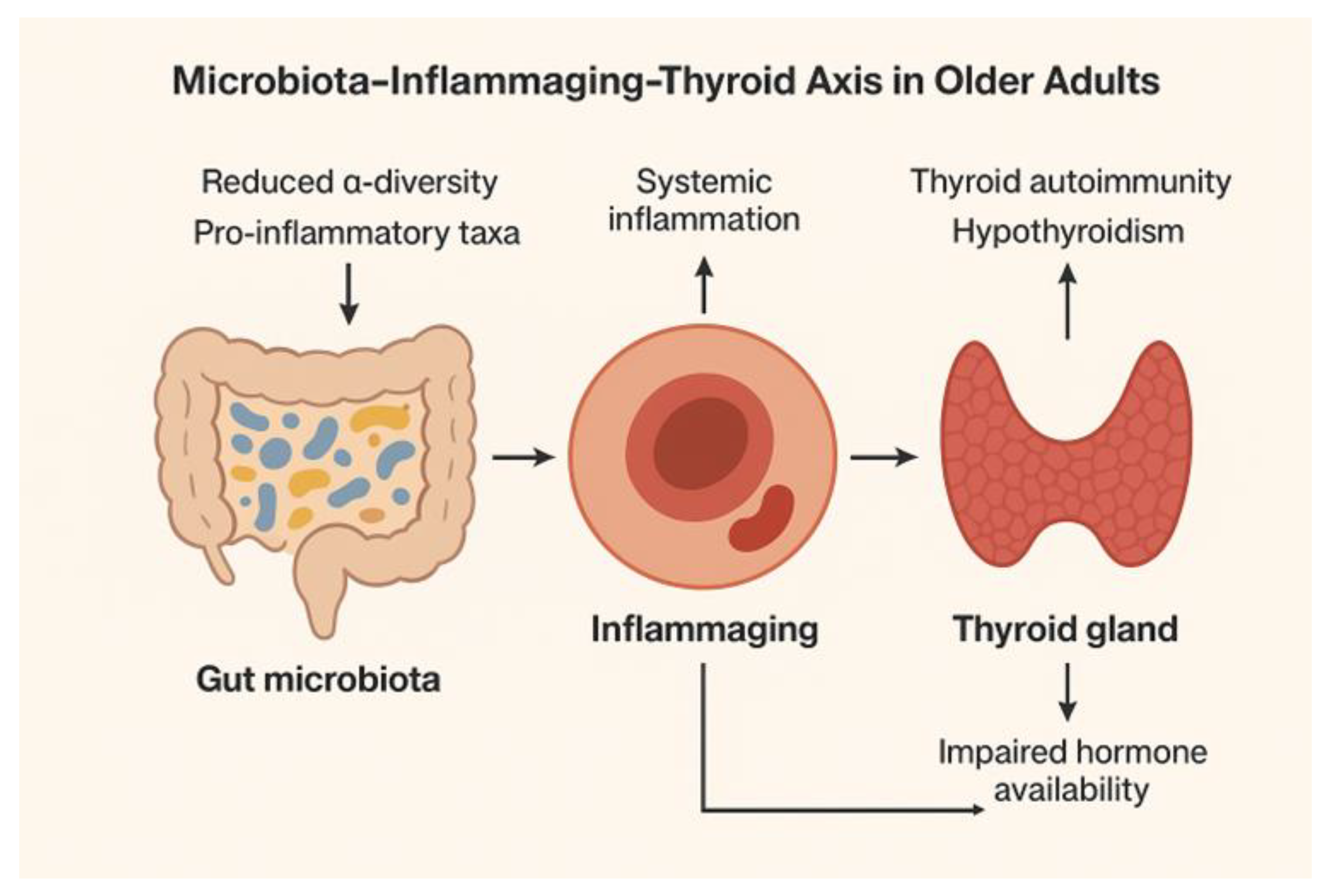

3.5.1. Gut Physiology and Microbiota

- Immune Modulation and Thyroid Autoimmunity

- Microbial Effects on Micronutrient Metabolism

- Influence on Enterohepatic Circulation and Peripheral Thyroid Hormone Metabolism

- Age-Related Microbiota Changes (Figure 3)

- Evidence linking microbiota composition to hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity

- Potential of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Symbiotics in Modulating Thyroid Outcomes

3.5.2. Changes in Dietary Habits, Nutrition and Gastrointestinal Physiology

- Dietary Transitions in Aging

- Gastrointestinal Structural and Functional Alterations

3.5.3. Pharmacologic and Iatrogenic Factors Affecting Thyroid Function in Older Adults

- Iodine-Rich Drugs

- Thyroid-Toxic Drugs

- Drugs Interfering with Levothyroxine Absorption

- Polypharmacy Patterns and Cumulative Impact in Older Adults

- Clinical Implications and Management

3.5.4. Metabolic Ageing and Thyroid–Iodine Interaction

- Metabolic Syndrome, Obesity, and Insulin Resistance

- Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation (“Inflammaging”)

- Influence of renal function decline on iodine excretion.

- Micronutrient Co-factors in Metabolic Ageing.

3.6. Clinical Implications and Management Strategies in Older Adults

3.7. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Transparency statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smyth, P.P.A. Iodine, Seaweed, and the Thyroid. European Thyroid Journal 2021, 10, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Kawashima, A.; Ishido, Y.; Yoshihara, A.; Oda, K.; Hiroi, N.; Ito, T.; Ishii, N.; Katayama, S.; Tsuboi, K.; Endo, T. Iodine Excess as an Environmental Risk Factor for Autoimmune Thyroid Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2014, 15, 12895–12912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.Y.; Inoue, K.; Rhee, C.M.; Leung, A.M. Risks of Iodine Excess. Endocrine Reviews 2024, 45, 858–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bath, S.C.; Steer, C.D.; Golding, J.; Emmett, P.; Rayman, M.P. Effect of Inadequate Iodine Status in UK Pregnant Women on Cognitive Outcomes in Their Children: Results from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children [ALSPAC]. The Lancet 2013, 382, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Boelaert, K. Iodine Deficiency and Thyroid Disorders. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2015, 3, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J.H. Iodine Status in Europe in 2014. European Thyroid Journal 2014, 3, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Andersson, M. Global Perspectives in Endocrinology: Coverage of Iodized Salt Programs and Iodine Status in 2020. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2021, 106, 3597–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, N.; Daya, N.R.; Juraschek, S.P.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Thyroid Dysfunction in Older Adults in the Community. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 13156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollowell, J.G.; Staehling, N.W.; Flanders, W.D.; et al. Serum TSH, T[43], and thyroid antibodies in the United States population [1988 to 1994]: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES III]. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekholdt, S.M.; Titan, S.M.; Wiersinga, W.M.; et al. Initial thyroid status and cardiovascular risk factors: The EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Clin. Endocrinol. 2010, 72, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, B.B.; Manning, L.; Chubb, S.A.; Hankey, G.J.; Golledge, J.; Almeida, O.P.; Flicker, L. Reference ranges for thyroid-stimulating hormone and free thyroxine in older men: Results from the Health In Men Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åsberg, A.; Berg, M.; Hov, G.G.; Lian, I.A.; Løfblad, L.; Mikkelsen, G. The HUNT study: Long-term within-subject variation of thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH]. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2025, 85, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahaly, G.J.; Dienes, H.P.; Beyer, J.; Hommel, G. Iodide induces thyroid autoimmunity in patients with endemic goiter: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 1998, 139, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalarani, I.B.; Veerabathiran, R. Impact of iodine intake on the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroid disease in children and adults. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 27, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K.L.; Targan, S.R.; Elson, C.O. 3rd. Microbiota activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2014, 260, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, A.; Shetty, G.B.; Shetty, P.; Nanjeshgowda, H.L. Influence of gut microbiota on autoimmunity: a narrative review. Brain Behav. Immun. Integr. 2024, 5, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, D.; Abdullahi, H.; Ibrahim, I. Bridging microbiomes: Exploring oral and gut microbiomes in autoimmune thyroid diseases—New insights and therapeutic frontiers. Gut Microbes Rep. 2025, 2, 2452471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka-Gutaj, N.; Gruszczyński, D.; Zawalna, N.; Nijakowski, K.; Muller, I.; Karpiński, T.; Salvi, M.; Ruchała, M. Microbiota alterations in patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-C.; Lin, S.-F.; Chen, S.-T.; Chang, P.-Y.; Yeh, Y.-M.; Lo, F.-S.; Lu, J.-J. Alterations of gut microbiota in patients with Graves’ disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 663131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Lu, G.; Gao, D.; Lv, Z.; Li, D. The relationships between the gut microbiota and its metabolites with thyroid diseases. Front. Endocrinol. [Lausanne] 2022, 13, 943408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ban; Y, Li, J; Wu, B; Ouyang, Q, et al. Efficacy evaluation of probiotics combined with prebiotics in patients with clinical hypothyroidism complicated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth during the second trimester of pregnancy. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022; 12:983027.

- Ouyang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Ban, Y.; Li, J.; Cai, Y.; Wu, B., et al. Probiotics and prebiotics in subclinical hypothyroidism of pregnancy with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024; 16, 579–588.

- Zawadzka, K.; Kałuzińska, K.; Świerz, M.J.; Sawiec, Z.; Antonowicz, E.; Leończyk-Spórna, M.; et al. Are probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics beneficial in primary thyroid diseases? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2023; 30, 217–23.

- Grassi, M.; Petraccia, L.; Mennuni, G.; et al. Changes, functional disorders, and diseases in the gastrointestinal tract of elderly. Nutr. Hosp. 2011, 26, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.E. Anorexia of ageing: A key component in the pathogenesis of both sarcopenia and cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, P.; Kaimal, N.; MacDonald, J.; Syed, A.A. Iodinated contrast-induced thyrotoxicosis. CMAJ 2013, 185, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayana, S.K.; Woods, D.R.; Boos, C.J. Management of amiodarone-related thyroid problems. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 2, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medić, F.; Bakula, M.; Alfirević, M.; Bakula, M.; Mucić, K.; Marić, N. Amiodarone and thyroid dysfunction. Acta Clin. Croat. 2022, 61, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, E.; Bartalena, L.; Bogazzi, F.; Braverman, L.E. The effects of amiodarone on the thyroid. Endocr. Rev. 2001, 22, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsoy, S.; Mavili, E.; Aydin, M.; Turan, T.; Esel, E. Ultrasonically determined thyroid volume and thyroid functions in lithium-naïve and lithium-treated patients with bipolar disorder: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 25, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, B.; Kahaly, G.J.; Robertson, R.P. Thyroid dysfunction and diabetes mellitus: Two closely associated disorders. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 789–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nillni, E.A.; Vaslet, C.; Harris, M.; Hollenberg, A.; Bjørbak, C.; Flier, J.S. Leptin regulates prothyrotropin-releasing hormone biosynthesis. Evidence for direct and indirect pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 36124–36133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, V.; Condorelli, R.A.; Cannarella, R.; Aversa, A.; Calogero, A.E.; La Vignera, S. Relationship between iron deficiency and thyroid function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somwaru, L.L.; Arnold, A.M.; Joshi, N.; Fried, L.P.; Cappola, A.R. High frequency of and factors associated with thyroid hormone over-replacement and under-replacement in men and women aged 65 and over. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 1342–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Kohrle, J. The impact of iron and selenium deficiencies on iodine and thyroid metabolism: Biochemistry and relevance to public health. Thyroid 2002, 12, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalnaya, M.G.; Skalny, A.V. Essential trace elements in human health: A physician’s view. Tomsk Publishing House of Tomsk State University: Tomsk, Russia, 2018.

- Virili, C.; Centanni, M. Does microbiota composition affect thyroid homeostasis? Endocrine 2015, 49, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Feng, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y. Alterations of the gut microbiota in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients. Thyroid 2018, 28, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurberg, P.; Cerqueira, C.; Ovesen, L.; Rasmussen, L.B.; Perrild, H.; Andersen, S.; Pedersen, I.B.; Carlé, A. Iodine Intake as a Determinant of Thyroid Disorders in Populations. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2010, 24, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; He, W.; Li, Q.; Jia, X.; Yao, Q.; Song, R.; Qin, Q.; Zhang, J.A. U-Shaped Relationship between Iodine Status and Thyroid Autoimmunity Risk in Adults. European Journal of Endocrinology 2019, 181, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health [accessed on 26 August 2025].

- Harper, S.; Howse, K.; Chan, A. Editorial: Integrating Age Structural Change into Global Policy. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 1005907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; de Benoist, B.; Rogers, L. Epidemiology of Iodine Deficiency: Salt Iodisation and Iodine Status. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2010, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertinato, J. Iodine Nutrition: Disorders, Monitoring and Policies. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research 2021, 96, 365–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, P.; Cook, P. The Assessment of Iodine Status—Populations, Individuals and Limitations. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry 2019, 56, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatch-McChesney, A.; Lieberman, H.R. Iodine and Iodine Deficiency: A Comprehensive Review of a Re-Emerging Issue. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Iodine Deficiency in Europe: A Continuing Public Health Problem. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241593960 [accessed on 26 August 2025].

- Niero, G.; Visentin, G.; Censi, S.; Righi, F.; Manuelian, C.L.; Formigoni, A.; Tenti, S.; Masoero, F.; Capelletti, M.; Gottardo, F.; Mason, F.; Masoero, G.; Bittante, G.; Schiavon, S. Invited Review: Iodine Level in Dairy Products—A Feed-to-Fork Overview. Journal of Dairy Science 2023, 106, 2213–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Bailey, E.H.; Arshad, M.; et al. Multiple Geochemical Factors May Cause Iodine and Selenium Deficiency in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2021, 43, 4493–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King’s College London. Urinary Iodine Concentration. Available online: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/open-global/biomarkers/mineral/iodine/urinary-iodine-concentration [accessed on 26 August 2025].

- World Health Organization. Iodine Deficiency. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/nutrition/nlis/info/iodine-deficiency [accessed on 26 August 2025].

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Fortification of Food-Grade Salt with Iodine for the Prevention and Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK254244/ [accessed on 26 August 2025].

- Bath, S.C.; Walter, A.; Taylor, A.; Wright, J.; Rayman, M.P. Iodine Deficiency in the UK: An Analysis of the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme. British Journal of Nutrition 2014, 112, 2066–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, E.N.; Lazarus, J.H.; Moreno-Reyes, R.; Zimmermann, M.B. Consequences of Iodine Deficiency and Excess in Pregnant Women: An Overview of Current Known and Unknowns. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2016, 104, 918S–923S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, S.C.; Rayman, M.P. A Review of Iodine Status of UK Pregnant Women and Its Impact on Neonatal Development. British Journal of Nutrition 2015, 114, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittermann, T.; Albrecht, D.; Arohonka, P.; et al. Standardized Map of Iodine Status in Europe. Thyroid 2020, 30, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.I. Hypothyroidism in Older Adults. In Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., et al., Eds.; Endotext: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279005/ (accessed on 14 July 2020).

- Vanderpump, M.P. The epidemiology of thyroid disease. Br. Med. Bull. 2011, 99, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madariaga, A.G.; Palacios, S.S.; Guillén-Grima, F.; Galofré, J.C. The incidence and prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in Europe: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlé, A.; Andersen, S.L.; Boelaert, K.; Laurberg, P. Management of endocrine disease: Subclinical thyrotoxicosis: Prevalence, causes and choice of therapy. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 176, R325–R337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawin, C.T.; Castelli, W.P.; Hershman, J.M.; McNamara, P.; Bacharach, P. The aging thyroid. Thyroid deficiency in the Framingham Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1985, 145, 1386–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochmann, H.; Bjøro, T.; Gaarder, P.I.; Hanson, F.; Frey, H.M. Prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in elderly subjects. A randomized study in a Norwegian rural community [Naerøy]. Acta Endocrinol. 1988, 117, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi, N.; Brown, T.R.; Parish, R.F. Thyroid dysfunction in adults over age 55 years. A study in an urban US community. Arch. Intern. Med. 1990, 150, 785–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luboshitzky, R.; Oberman, A.S.; Kaufman, N.; Reichman, N.; Flatau, E. Prevalence of cognitive dysfunction and hypothyroidism in an elderly community population. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 1996, 32, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Surks, M.I.; Hollowell, J.G. Age-specific distribution of serum thyrotropin and antithyroid antibodies in the US population: Implications for the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 4575–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, S.; Franceschi, C.; Cossarizza, A.; et al. The aging thyroid. Endocr. Rev. 1995, 16, 686–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, S.; Barbesino, G.; Caturegli, P.; et al. Complex alteration of thyroid function in healthy centenarians. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1993, 77, 1130–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Volzke, H.; Alte, D.; Kohlmann, T.; et al. Reference intervals of serum thyroid function tests in a previously iodine-deficient area. Thyroid 2005, 15, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenga, S.; Di Bari, F.; Vita, R. Undertreated hypothyroidism due to calcium or iron supplementation corrected by oral liquid levothyroxine. Endocrine 2017, 56, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Ostan, R.; Mariotti, S.; Monti, D.; Vitale, G. The aging thyroid: A reappraisal within the geroscience integrated perspective. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 1250–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Boelaert, K. Iodine deficiency and thyroid disorders. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayie, F.A.K.; Jourdan, K. Hypertension, dietary salt restriction, and iodine deficiency among adults. Am. J. Hypertens. 2010, 23, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Ma, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, J. A cross-sectional survey of iodized salt usage in dining establishments—13 PLADs, China, 2021–2022. China CDC Wkly. 2023, 5, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Iodization of salt for the prevention and control of iodine deficiency disorders. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/elena/interventions/salt-iodization [accessed on 9 August 2025].

- Sorrenti, S.; Baldini, E.; Pironi, D.; Lauro, A.; D'Orazi, V.; Tartaglia, F.; Tripodi, D.; Lori, E.; Gagliardi, F.; Praticò, M.; et al. Iodine: Its role in thyroid hormone biosynthesis and beyond. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.N.; Lansdown, A.; Witczak, J.; Khan, R.; Rees, A.; Dayan, C.M.; Okosieme, O. Age-related variation in thyroid function—A narrative review highlighting important implications for research and clinical practice. Thyroid Res. 2023, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooradian, A.D. Age-related thyroid hormone resistance: A friend or foe. Endocr. Metab. Sci. 2023, 11, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, O.; Razvi, S. Hypothyroidism in the older population. Thyroid Res. 2019, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yi, S.; Kang, Y.E.; Kim, H.W.; Joung, K.H.; Sul, H.J.; Kim, K.S.; Shong, M. Morphological and functional changes in the thyroid follicles of the aged murine and humans. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2016, 50, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, K.; Georgopoulos, N.; Kyriazopoulou, V.; Vagenakis, A.G. Iodine-induced hypothyroidism. Thyroid 2001, 11, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medić, F.; Bakula, M.; Alfirević, M.; Bakula, M.; Mucić, K.; Marić, N. Amiodarone and thyroid dysfunction. Acta Clin. Croat. 2022, 61, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Shan, Z.; Teng, W. Effects of increased iodine intake on thyroid disorders. Endocrinol. Metab. [Seoul] 2014, 29, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Peng, D.; Zhao, L. Iodinated contrast media [ICM]-induced thyroid dysfunction: a review of potential mechanisms and clinical management. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Teng, D.; Shi, X.; Ba, J.; Chen, B.; Du, J.; He, L.; Lai, X.; Teng, X.; Li, Y.; Chi, H.; Liao, E.; Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Qin, G.; Qin, Y.; Quan, H.; Shi, B.; Sun, H.; Tang, X.; Tong, N.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J.A.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Yan, L.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Yao, Y.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, M.; Ning, G.; Mu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Teng, W.; Shan, Z. U-shaped associations between urinary iodine concentration and the prevalence of metabolic disorders: a cross-sectional study. Thyroid 2020, 30, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.M.; Braverman, L.E. Iodine-induced thyroid dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2012, 19, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.M.; Braverman, L.E. Consequences of excess iodine. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, I.B.; Knudsen, N.; Carlé, A.; Vejbjerg, P.; Jørgensen, T.; Perrild, H.; Ovesen, L.; Rasmussen, L.B.; Laurberg, P. A cautious iodization programme bringing iodine intake to a low recommended level is associated with an increase in the prevalence of thyroid autoantibodies in the population. Clin. Endocrinol. [Oxf.] 2011, 75, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Ning, J. Recent advances in gut microbiota and thyroid disease: pathogenesis and therapeutics in autoimmune, neoplastic, and nodular conditions. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1465928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qin, X.; Lin, B.; et al. Analysis of gut microbiota diversity in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-León, M.J.; Mangalam, A.K.; Regaldiz, A.; González-Madrid, E.; Rangel-Ramírez, M.A.; Álvarez-Mardonez, O.; Vallejos, O.P.; Méndez, C.; Bueno, S.M.; Melo-González, F.; Duarte, Y.; Opazo, M.C.; Kalergis, A.M.; Riedel, C.A. Gut microbiota short-chain fatty acids and their impact on the host thyroid function and diseases. Front. Endocrinol. [Lausanne] 2023, 14, 1192216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, C.; Feng, S.; et al. Intestinal microbiota regulates the gut-thyroid axis: the new dawn of improving Hashimoto thyroiditis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulizi, N.; Quin, C.; Brown, K.; Chan, Y.K.; Gill, S.K.; Gibson, D.L. Gut mucosal proteins and bacteriome are shaped by the saturation index of dietary lipids. Nutrients 2019, 11, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulhai, A.M.; Rotondo, R.; Petraroli, M.; Patianna, V.; Predieri, B.; Iughetti, L.; et al. The role of nutrition on thyroid function. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.; Melo, M.; Carrilho, F. Selenium and thyroid disease: From pathophysiology to treatment. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 2017, 1297658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenneman, A.C.; Bruinstroop, E.; Nieuwdorp, M.; van der Spek, A.H.; Boelen, A. A comprehensive review of thyroid hormone metabolism in the gut and its clinical implications. Thyroid 2023, 33, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellock, S.J.; Redinbo, M.R. Glucuronides in the gut: Sugar-driven symbioses between microbe and host. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 8569–8576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröhlich, E.; Wahl, R. Microbiota and thyroid interaction in health and disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 30, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.J.; Le Couteur, D.G.; Raubenheimer, D. Putting the balance back in diet. Cell 2015, 161, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odamaki, T.; Kato, K.; Sugahara, H.; et al. Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian: A cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Parini, P.; Giuliani, C.; Santoro, A. Inflammaging: A new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, M.J.; Jeffery, I.B.; Conde, S.; Power, S.E.; O'Connor, E.M.; Cusack, S.; Harris, H.M.; Coakley, M.; Lakshminarayanan, B.; O'Sullivan, O.; et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature 2012, 488, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campaniello, D.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Altieri, C.; Bevilacqua, A. How diet and physical activity modulate gut microbiota: Evidence, and perspectives. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagi, E.; Franceschi, C.; Rampelli, S.; Severgnini, M.; Ostan, R.; Turroni, S.; Consolandi, C.; Quercia, S.; Scurti, M.; Monti, D.; et al. Gut microbiota and extreme longevity. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Chen, J.; Chen, S.; He, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Yu, L. Cross-talk between the gut microbiota and hypothyroidism: A bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1286593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, X.Q.; Wang, W.H.; Gao, Y.H.; Zhang, T.X.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhao, Z.D.; Zhang, H.W. Role of immune cells in mediating the effect of gut microbiota on Hashimoto's thyroiditis: A 2-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1463394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, J.; Starchl, C.; Tmava Berisha, A.; Amrein, K. Thyroid-gut-axis: How does the microbiota influence thyroid function? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazidi, M.; Rezaie, P.; Ferns, G.A.; Vatanparast, H. Impact of probiotic administration on serum C-reactive protein concentrations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Nutrients 2017, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Li, D.; Wang, C.Z.; Wan, J.Y.; Yao, H.; Yuan, C.S. Probiotics fortify intestinal barrier function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1143548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprecht, M.; Bogner, S.; Schippinger, G.; et al. Probiotic supplementation affects markers of intestinal barrier, oxidation, and inflammation in trained men; A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2012, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, D.; Cen, C.; Chang, H.; et al. Probiotic Bifidobacterium longum supplied with methimazole improved the thyroid function of Graves’ disease patients through the gut-thyroid axis. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.S.; Gill, H.S. Immunostimulatory probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 and Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 do not induce pathological inflammation in mouse model of experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 103, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voicu, S.N.; Scărlătescu, A.I.A.; Apetroaei, M.M.; Nedea, M.I.I.; Blejan, I.E.; Udeanu, D.I.; Velescu, B.Ș.; Ghica, M.; Nedea, O.A.; Cobelschi, C.P.; Arsene, A.L. Evaluation of neuro-hormonal dynamics after the administration of probiotic microbial strains in a murine model of hyperthyroidism. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, N.; Chittawar, S.; Khandelwal, D. Gut-thyroid axis and emerging role of probiotics in thyroid disorders. Thyroid Research and Practice. 2025, 21, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.; Kang, C.; Li, J.; Hou, Z.; Xiong, M.; Wang, X.; Peng, H. Effect of probiotics or prebiotics on thyroid function: A meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0296733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zempleni, S.; Christensen, S. The risk for malnutrition increases with high age. Pressbooks Nebraska n.d.. Available online: https://pressbooks.nebraska.edu/nutr251/chapter/the-risk-for-malnutrition-increases-with-high-age/.

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Andersson, M. Global endocrinology: Global perspectives in endocrinology: Coverage of iodized salt programs and iodine status in 2020. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 185, R13–R21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidelbaugh, J.J.; Metz, D.C.; Yang, Y.-X. Proton pump inhibitors: Are they overutilized in clinical practice and do they pose significant risk? Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012, 66, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löhr, J.-M.; Panic, N.; Vujasinovic, M.; Verbeke, C.S. The ageing pancreas: A systematic review of the evidence and analysis of the consequences. Pancreatology 2018, 18, 446–460. [Google Scholar]

- Drozdowski, L.; Thomson, A.B. Aging and the intestine. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 7578–7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, Z.; Avery, A.; Kalogiros, D.I.; Coneyworth, L.J.; Welham, S.J.M. Trace mineral intake and deficiencies in older adults living in the community and institutions: A systematic review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałkowska-Goździk, E.; Lachowicz, K.; Rosołowska-Huszcz, D. Effects of dietary protein on thyroid axis activity. Nutrients 2017, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Xue, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, G. Trace elements and the thyroid. Front. Endocrinol. [Lausanne] 2022, 13, 904889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Feng, H.F.; Liu, H.Q.; Guo, L.T.; Chen, C.; Yao, X.L.; Sun, S.R. Immune checkpoint inhibitors-related thyroid dysfunction: Epidemiology, clinical presentation, possible pathogenesis, and management. Front. Endocrinol. [Lausanne] 2021, 12, 649863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemons, J.; Gao, D.; Naam, M.; Breaker, K.; Garfield, D.; Flaig, T.W. Thyroid dysfunction in patients treated with sunitinib or sorafenib. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2012, 10, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liwanpo, L.; Hershman, J.M. Conditions and drugs interfering with thyroxine absorption. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 23, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghtedari, B.; Correa, R. Levothyroxine. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Livecchi, R.; Coe, A.B.; Reyes-Gastelum, D.; Banerjee, M.; Haymart, M.R.; Papaleontiou, M. Concurrent use of thyroid hormone therapy and interfering medications in older US veterans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e2738–e2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Lu, M.; Hu, J.; Fu, G.; Feng, Q.; Sun, S.; Chen, C. Medications and food interfering with the bioavailability of levothyroxine: A systematic review. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2023, 19, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Bakal, K.; Minokoshi, Y.; Hollenberg, A.N. Leptin signaling targets the thyrotropin-releasing hormone gene promoter in vivo. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 2221–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogan, B.İ.; Sahin, M. Adipocytokines in thyroid dysfunction. ISRN Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 646271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, A.C.; Rodondi, N.; Harrison, S.; Kanaya, A.M.; Simonsick, E.M.; Miljkovic, I.; Satterfield, S.; Newman, A.B.; Bauer, D.C.; Health, Ageing, and Body Composition [Health ABC] Study. Thyroid function and prevalent and incident metabolic syndrome in older adults: The Health, Ageing and Body Composition Study. Clin. Endocrinol. [Oxf.] 2012, 76, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delitala, A.P.; Scuteri, A.; Fiorillo, E.; Lakatta, E.G.; Schlessinger, D.; Cucca, F. Role of adipokines in the association between thyroid hormone and components of the metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassock, R.J.; Rule, A.D. The implications of anatomical and functional changes of the aging kidney: With an emphasis on the glomeruli. Kidney Int. 2016, 91, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, S.; Mikeda, T.; Okada, T.; et al. Chronic kidney disease and thyroid disorders in adult Japanese patients. Endocr. J. 2018, 65, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, R.; Yuan, X.; Kobayashi, S.; et al. Effect of dietary sodium intake on iodine status in Japanese adults: Cross-sectional analysis of the NHNS. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehade, J.M.; Belal, H.F. Cross-section of thyroidology and nephrology: Literature review and key points for clinicians. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2024, 37, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomburg, L. Selenium, selenoproteins and the thyroid gland: Interactions in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2011, 8, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, G.J.; Arthur, J.R. Thyroid hormone and trace elements. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 591–595. [Google Scholar]

- Baltaci, A.K.; Mogulkoc, R. Zinc and thyroid function. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 183, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, M.B. The influence of iron status on iodine utilization and thyroid function. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2006, 26, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, B.; Cappola, A.R.; Cooper, D.S. Subclinical hypothyroidism: A review. JAMA 2019, 322, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centanni, M.; et al. Thyroxine in goiter, Helicobacter pylori infection, and chronic gastritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar]

- Aakre, I.; Solli, D.D.; Markhus, M.W.; Mæhre, H.K.; Dahl, L.; Henjum, S.; Alexander, J.; Meltzer, H.M. Commercially Available Kelp and Seaweed Products: Valuable Iodine Source or Risk of Excess Intake? Food & Nutrition Research 2021, 65, 7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dold, S.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Jukic, T.; Kusic, Z.; Jia, Q.; Sang, Z.; Quirino, A.; San Luis, T.O.L.; Fingerhut, R.; Kupka, R.; Timmer, A.; Garrett, G.S.; Andersson, M. Universal Salt Iodization Provides Sufficient Dietary Iodine to Achieve Adequate Iodine Nutrition during the First 1000 Days: A Cross-Sectional Multicenter Study. The Journal of Nutrition 2018, 148, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorstein, J.L.; Bagriansky, J.; Pearce, E.N.; Kupka, R.; Zimmermann, M.B. Estimating the Health and Economic Benefits of Universal Salt Iodization Programs to Correct Iodine Deficiency Disorders. Thyroid 2020, 30, 1802–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.M.; Avram, A.M.; Brenner, A.V.; et al. Potential Risks of Excess Iodine Intake and Exposure: Statement by the American Thyroid Association Public Health Committee. Thyroid 2022, 32, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldimann, M.; Alt, A.; Blanc, A.; Blondeau, K. Iodine Content of Food Groups. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2005, 18, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | References | Notes / Focus / Overlaps |

|---|---|---|

|

1–30, 58, 60, 62–67 | Deficiency/excess, hormone synthesis, population surveys; overlaps with Wolff–Chaikoff effect |

|

3, 4, 31–42, 44, 54–57 | Elderly thyroid function, structural/hormonal changes; overlaps with metabolic ageing & nutritional changes |

|

19–21, 58, 60–66, 110–113 | Iodine-induced hypothyroidism, autoregulation mechanisms; overlaps with iodine intake |

|

68–75, 77–100, 142–143 | Gut–thyroid interactions, autoimmunity, probiotics; overlaps with nutritional/GI changes |

|

101–103, 105–109, 115, 138, 140 | Malnutrition, protein/mineral intake, GI aging; overlaps with microbiota axis & ageing adaptations |

|

110–114, 116–121 | Drugs affecting thyroid, contrast agents, interactions; overlaps with Wolff–Chaikoff effect in some cases |

|

122–137, 139, 141 | Thyroid–metabolism interplay, diabetes, adipokines, kidney; overlaps with ageing adaptations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).