1. Introduction

Vitamin D is known as the 'sunshine hormone' [

1]. Its status is usually conditioned by various factors, such as skin pigmentation, physical agents that block exposure to solar radiation (e.g. clothing and sunscreens), and geographical location (e.g. latitude, climate, season and altitude) [

2,

3]. However, irrespective of its associated factors, vitamin D deficiency is now considered a worldwide pandemic representing a public health concern with multiple health consequences [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Apart from its fundamental role in regulating calcium and phosphorus homeostasis for skeletal development, vitamin D also mediates other functions, including cell proliferation and differentiation, anti-inflammatory action, and the regulation of innate and acquired immunity. Calcidiol, the major circulating vitamin D metabolite, is considered the best indicator of vitamin D status due to its long half-life, relative stability, and responsiveness to endogenous production or exogenous intake of vitamin D [

8]. In fact, it has come to be known as the “barometer” of vitamin D status. Currently, the American Endocrine Society criteria for classification of vitamin D status [

9] are the most widely accepted and used by authors (

Table 1).

Table 1.

American Endocrine Society criteria for classification of vitamin D status.

Table 1.

American Endocrine Society criteria for classification of vitamin D status.

| Vitamin D status |

Calcidiol level (1 ng/mL corresponds to 2.5 nmol/L) |

Vitamin D deficiency

Vitamin D insufficiency

Vitamin D sufficiency |

<20 ng/m (<50 nmol/L)

20 to 29 ng/mL (51–74 nmol/L)

≥30 ng/m (≥75 nmol/L) |

Table 2.

Prevalence of maternal and newborn vitamin D deficiency [calcidiol <30 ng/m L (adapted from [

15] and [

42]).

Table 2.

Prevalence of maternal and newborn vitamin D deficiency [calcidiol <30 ng/m L (adapted from [

15] and [

42]).

| WHO regions |

Maternal (%) |

Newborn (%) |

| Northern America |

64 |

30 |

| European |

57 |

73 |

| Eastern Mediterrranean |

46 |

60 |

| South-East Asian |

87 |

96 |

| Western Pacific |

83 |

54 |

| Africa |

44 |

49 |

During pregnancy, the fetus is entirely dependent on maternal sources of vitamin D, which also regulate placental function [

10]. The metabolic physiology of pregnant women is distinct from that of other women. In fact, during pregnancy, the mother modifies her physiological and homeostatic mechanisms to satisfy the physiological needs of the growing fetus. In recent years, the potential impact of vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy on maternal and neonatal health has received increasing attention. Vitamin D is essential for placental function, calcium homeostasis and fetal bone mineralization — all of which are important for fetal development and growth [

11,

12,

13]. Furthermore, as vitamin D plays an immunomodulatory role, it has been suggested that it contributes to maternal-fetal immune tolerance; without this, the fetus could not survive [

2,

14]. Therefore, it is important to maintain adequate maternal vitamin D levels during pregnancy to avoid adverse outcomes for the pregnancy, the fetus and the postnatal period. Pregnant women and newborns are recognized as populations at increased risk of vitamin D deficiency [

2,

3,

4,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of spontaneous early pregnancy loss, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, caesarean section, bacterial vaginosis, postpartum depression, preterm delivery and low birth weight (LBW), as well as being small for gestational age (SGA) [

7,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive narrative review of (a) recent data on the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women, (b) the relationship between maternal and neonatal vitamin D levels, and the possible influence of vitamin D deficiency on the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and (c) the potential benefits of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on neonatal anthropometry. The review is based on an electronic literature search performed by two independent researchers in the PubMed database of the US National Library of Medicine, covering publications from January 2014 to December 2024. The following Medical Subject Headings or keywords were used alone or in combination for the search: 'vitamin D status', 'vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency', 'pregnancy', 'intrauterine growth restriction', 'small for gestational age', 'low birth weight' and 'vitamin D supplementation'.

2. Vitamin D Metabolism and Adaptive Changes During Pregnancy

Vitamin D (cholecalciferol) is a prohormone that is synthesized primarily endogenously in the skin under the influence of solar radiation (ultraviolet radiation type B) and requires double hydroxylation for its functional activation. It is then released into the bloodstream, where it is transported to the liver bound to vitamin D binding protein (VDBP). There, the enzyme cholecalciferol-25-hydroxylase (CYP2R1) catalyzes the first hydroxylation, creating 25-hydroxycholecalciferol, also known as calcidiol. Calcidiol is the primary circulating vitamin D metabolite and is used to determine vitamin D status. However, it is not the active form of vitamin D. Calcidiol is released into the bloodstream, where it is transported bound to VDBP to the kidneys. There, the enzyme 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) catalyzes a second hydroxylation, converting calcidiol to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D₃ (calcitriol), the biologically active form of vitamin D. CYP27B1 is primarily expressed in the kidneys but can also be found in multiple tissues, including the placenta.

Renal CYP27B1 is responsible for most of the circulating calcitriol. The main regulators of renal calcitriol synthesis are parathyroid hormone (PTH) -which signals calcium serum levels-, fibroblast growth factor (FGF23) -which signals serum phosphate levels-, and calcitriol itself. In fact, calcitriol regulates its own catabolism via feedback mechanisms, whereby high concentrations activate the functionality of the CYP24A1 enzyme (24-hydroxylase activity), which catalyzes the conversion of calcidiol and calcitriol into 24,25(OH)₂D and 1,24,25(OH)₃D (vitamin D metabolites with virtually no biological activity). Simultaneously, it reduces enzymatic activity of CYP27B1, resulting in a decrease in calcitriol levels.

The physiological role of vitamin D extends far beyond regulating calcium homeostasis and bone metabolism; it has a variety of effects outside of the skeleton. In fact, vitamin D is now considered a pleiotropic hormone that acts through genomic and non-genomic pathways. Most of vitamin D's effects are mediated by its interaction with a nuclear transcription factor, the vitamin D receptor (VDR), and subsequent binding to specific DNA sequences. This regulates the expression of a large number of target genes (about 5–10% of the total human genome) that are involved in several physiological processes. These include cellular proliferation and differentiation, as well as anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities (genomic pathway). Additionally, vitamin D induces rapid, non-genomic cellular responses by binding to a membrane receptor called the membrane-associated rapid response steroid (MARRS) in order to regulate several intracellular processes, such as calcium transport, mitochondrial function, and ion channel activity [

2,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

During pregnancy, maternal calcium metabolism undergoes significant changes to support adequate fetal bone mineralization. Consequently, several physiological adaptations occur, including increased maternal serum calcitriol and VDBP, as well as increased placental VDR and renal and placental CYP27B1 activity. Finally, there is a decrease in calcitriol catabolism, though this is not associated with changes in serum calcium and PTH levels [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. In pregnant women, serum calcitriol levels increase from the first trimester of pregnancy, tripling their concentration compared to the preconception stage by the end of the third trimester (calcitriol does not cross the placental barrier). This is not associated with changes in serum calcium and PTH levels, and these return to normal values after delivery. This possibility is due to the fact that during pregnancy, there is a significant increase in maternal renal synthesis of calcitriol due to increased CYP27B1 activity. Furthermore, the placenta also plays an important role, as both the maternal (decidual) and fetal (trophoblastic) placentas exhibit CYP27B1 activity and, as extrarenal organs, contribute significantly to vitamin D activation. Increased maternal calcitriol levels would promote intestinal calcium absorption and, consequently, a secondary increase in plasma levels to cover, through transplacental passage, fetal calcium demands for skeletal mineralization [

35]. The mechanisms that lead to an increase in CYP27B1 activity during pregnancy remains unclear, in part because its known regulatory factors, such as PTH, remain unchanged and/or suppressed during gestation (during pregnancy PTH as a marker of vitamin D status is unreliable). It has been hypothesized that a potential regulatory factor for CYP27B1 activity could be, in conjunction with other factors (calcitonin, IGF-1, placental lactogen, estradiol, and prolactin), PTH-related peptide (PTH-rP), a PTH analogue that increases throughout pregnancy. This peptide is synthesized in the placenta (both maternal and fetal), as well as in the fetal parathyroid glands [

36], and would explain, to a large extent, the significant increase in calcitriol and the suppression of PTH levels during pregnancy [

37]. Maternal VDBP levels increase significantly during gestation. Given VDBP's greater affinity for calcidiol than calcitriol, some have suggested that this increase may serve as a reservoir for calcidiol and/or redistribute it into the fetal circulation. As previously mentioned, in non-pregnant women, calcitriol regulates its own catabolism through feedback mechanisms. However, during pregnancy, placental methylation of the CYP24A1 enzyme reduces its functionality. Consequently, activation of the vitamin D catabolism mechanism is reduced. This epigenetic imbalance in the vitamin D feedback loop greatly contributes to increased maternal calcitriol levels during pregnancy and ensures greater calcium transfer between mother and fetus. [

2,

38].

One of the most important contributions of vitamin D during pregnancy is increasing maternal calcium absorption and placental transport. However, since VDR and CYP27B1 are also expressed in other female reproductive tissues, such as the uterus, ovaries, endometrium, and fallopian epithelial cells, other possible paracrine and autocrine actions of calcitriol cannot be ruled out. Vitamin D also plays a critical role in regulating the innate and adaptive immune systems, which is crucial since an adequate balance of cytokines is necessary for a successful pregnancy. Vitamin D improves the antimicrobial properties of barrier epithelia by modulating the genetic expression of potent antimicrobial peptides, such as cathelicidin and β-defensins, which destroy the cell membranes of bacteria and viruses. Additionally, vitamin D inhibits the production of inflammatory cytokines: interleukin (IL)-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, IL-21, tumor necrosis factor-alfa (TNF-α) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and increases the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines: IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β). In other words, vitamin D plays a dual role: improving the innate immune response and neutralizing potentially exacerbated inflammation [

22,

39,

40,

41]. The biological effects of vitamin D on the placenta are also related to hormonogenesis and overall placental physiology. Vitamin D induces endometrial decidualization and the synthesis of estradiol and progesterone; however, it also regulates the expression of human chorionic gonadotropin and placental lactogen. Considering the significant impact of vitamin D on human pregnancy, it is not surprising that vitamin D deficiency could contribute to various pregnancy-related disorders [

2,

22].

3. Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency in the Pregnant Women

As previously mentioned, various factors influence vitamin D status and should be considered when comparing the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in countries with different ethnic, cultural or geographic characteristics (2, 3]. Vitamin D deficiency has been reported among pregnant women worldwide. For instance, a 2013 narrative review indicated that, although the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy depends on geographic area of residence, it is a particular global concern. Indeed, vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women was found to range from 27% to 91% in the United States, 39% to 65% in Canada, 70% to 100% in Northern Europe, 78% to 100% in the Middle East, 45% to 98% in Asia and 25% to 65% in Australia. The review provided a global overview of the incidence of vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women worldwide, and the available data indicated that vitamin D deficiency is a global public health issue affecting all age groups, particularly pregnant women, even in those countries with year-round sun exposure [

2].

Subsequently, a systematic review with meta-analysis was published in 2016 with the aim of creating a global summary of maternal and neonatal vitamin D status [

15]. The review, which involved pregnant women and their newborns from different population groups corresponding to WHO regions from which data were available (North America, Europe, the Eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asia, and the Western Pacific), indicates that vitamin D deficiency was present in 54% of pregnant women and 75% of newborns. Severe vitamin D deficiency was present in 18% of pregnant women and 29% of newborns. There was some variability among the different geographic areas included in the study. Indeed, the regional ranking of the proportion of pregnant women with vitamin D deficiency was as follows: South-East Asia: 87%, Western Pacific: 83%, Americas: 64%, Europe: 57%, Eastern Mediterranean: 46%. The regional ranking of the proportion of newborns with vitamin D deficiency was as follows: South-East Asia: 96%; Europe: 73%; Eastern Mediterranean: 60%; Western Pacific: 54%; and the Americas: 30% (

Table 1). A systematic review and meta-analysis that included participants from 23 African countries is worth mentioning concerning the African continent. Despite great methodological heterogeneity, the meta-analysis revealed that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in African general population, particularly among pregnant women (44%) and newborns (49%), was higher than expected given the abundant sunshine in the continent (

Table 1). This was mainly observed in populations living in North Africa and South Africa, as opposed to sub-Saharan Africa [

42].

Recently, several studies have been published in low-latitude countries, which are assumed to have sufficient solar radiation to prevent vitamin D deficiency. However, the authors of these studies concluded that abundant sunlight exposure in these countries is not sufficient to prevent hypovitaminosis D. Therefore, they recommend that pregnant women be prescribed vitamin D supplements and consume vitamin D-fortified foods. For instance, one observational study assessed the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women at the Shanghai Changning District Maternal and Child Health Hospital. A total of 34,417 women were included in the study, and their vitamin D status was measured at week 16 of gestation. The results revealed that 98.4% of the pregnant women had hypovitaminosis D (28.4% were insufficient and 70% were deficient), and only 1.6% of the participants had adequate vitamin D levels [

43]. In contrast, a cross-sectional study conducted in the Obstetrics department of a tertiary care hospital in Chennai, India, estimated a 62% prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women in their third trimester. Linear regression analysis showed that sun exposure was a significant predictor of serum calcidiol levels among antenatal mothers [

44]. Additionally, a prospective cohort study was conducted at the KK Women's and Children's Hospital in Singapore. A total of 93 pregnant women in their first trimester (>15 weeks gestation) were recruited, and their vitamin D status was assessed. Only 2.2% of participants had sufficient vitamin D levels; the rest had hypovitaminosis D (insufficient: 49.5%; deficient: 48.4%) [

45]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional and observational studies of pregnant women in Indonesia has been conducted. This study examined 830 pregnant women and found that 78% suffered from hypovitaminosis D (25% had insufficient levels and 63% had deficient levels) [

46]. Both Singapore and Indonesia are equatorial countries located in Southeast Asia with no seasonal changes. Although ethnic and/or cultural reasons, such as higher skin pigmentation and traditional dress like the hijab or shari, have been given, the very high prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in such sunny countries is an enigma and a public health emergency.

4. Relationship Between Maternal and Neonatal Vitamin D Levels

In recent years, research has focused on the relationship between maternal and neonatal vitamin D levels. Several studies have shown a correlation between neonatal vitamin D levels at birth and maternal plasma vitamin D levels. Most studies support the idea that fetal vitamin D concentrations depend on maternal concentrations [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

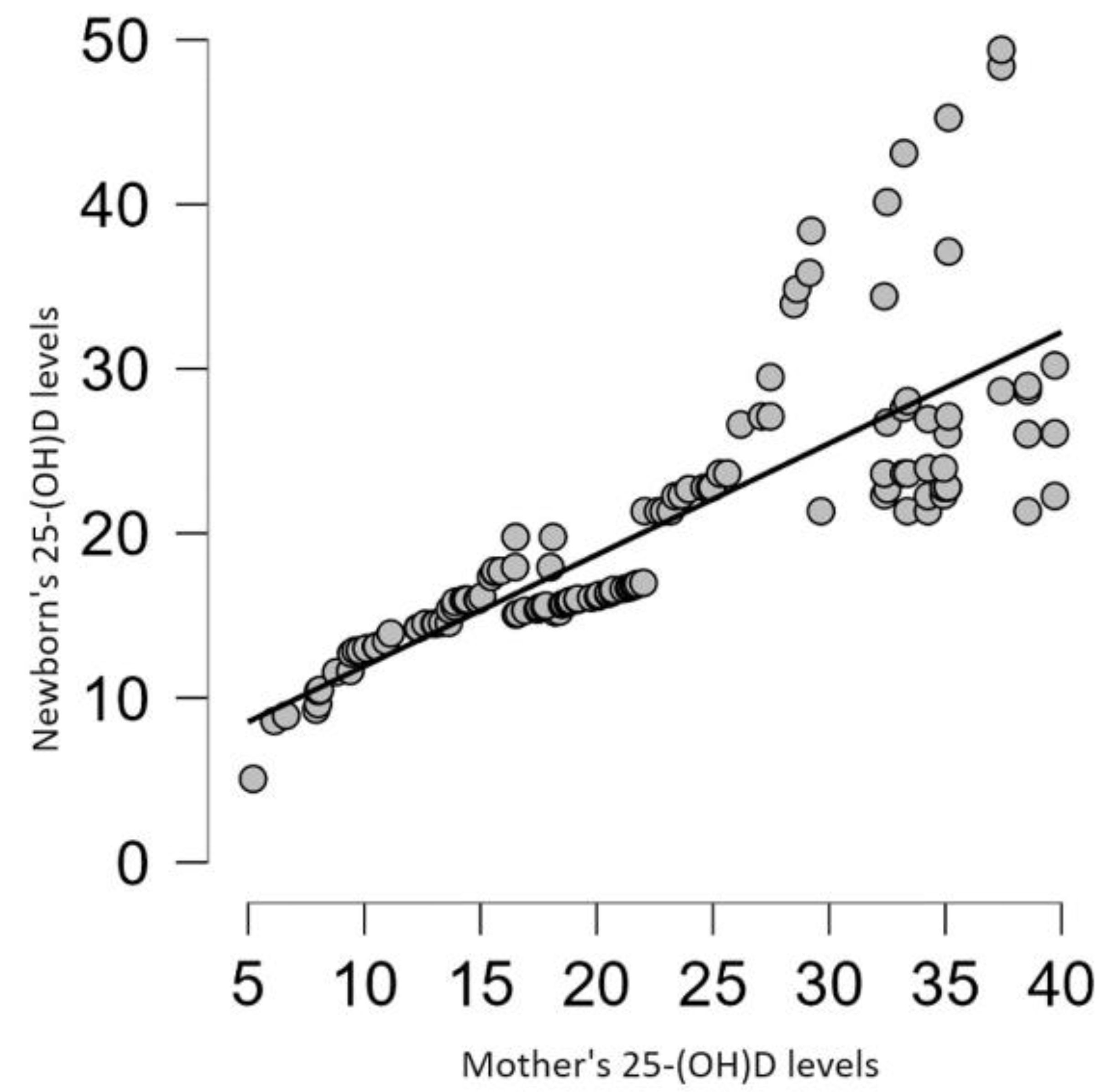

A prospective, multiethnic, population-based cohort study of 7,098 mother-child pairs in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, conducted as a part of the Generation R Study, stands out. Maternal blood samples were collected in the second trimester of pregnancy and umbilical cord blood samples were collected after delivery. A statistically significant correlation (r = 0.62) was found between maternal vitamin D concentrations in the second trimester and umbilical cord blood [

11]. Several studies have recently been published that corroborate the relationship between maternal and neonatal vitamin D levels. For example, an observational study conducted at the Obstetrics Clinic of the County Clinical Hospital in Târgu Mureș, Romania, included 131 mothers and their newborns at delivery (37–42 weeks of gestation). All of the mothers in the study had vitamin D insufficiency (26%) or deficiency (74%). The results clearly showed a positive linear correlation between maternal and neonatal serum vitamin D levels (Pearson's r = 0.96, p < 0.01) and underscore the importance of investigating the impact of vitamin D deficiency on neonatal health outcomes [

54]. Another descriptive-observational study was conducted with 102 mother-child pairs at a tertiary care center (Hind Institute of Medical Sciences, Barabanki, India). All of the included mothers had given birth to healthy, full-term babies. The study found that 65.7% of mothers and 78.4% of babies had insufficient vitamin D. There was also a clear link between the vitamin D levels of the mothers and babies. (Pearson's r = 0.68; p < 0.0001). The authors emphasize that even in regions with abundant sunlight, pregnant women and their newborns had inadequate serum vitamin D concentrations [

55].

Finally, a cross-sectional study conducted on 248 neonates and their mothers at Tzaneio General Hospital in Piraeus, Greece (a country with low latitudes where ultraviolet radiation is generally assumed to be sufficient to prevent vitamin D deficiency) is worth mentioning. The vitamin D status of the mothers before delivery and of the neonates in their umbilical cord blood was studied. Vitamin D deficiency was found in 58% of mothers, while 25% were vitamin D insufficient. Only 17% of pregnant women had normal vitamin D status. Among newborns, vitamin D deficiency was recorded in 66% of cases, while vitamin D insufficiency was recorded in 29% of cases. Only 5% of neonates had normal vitamin D status. Additionally, a strong direct correlation was observed between maternal and neonatal vitamin D concentrations based on the Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.8 [

56]. Similar results were obtained in a retrospective study conducted at a tertiary maternity hospital in Bucharest, Romania, involving 130 pregnant women and their newborns. A significant, strong, positive, direct correlation (r = 0.79) was observed between maternal and neonatal vitamin D status (

Figure 1) [

57]. One of the most interesting findings of both studies was that most newborns of mothers with severe vitamin D deficiency also had it. Additionally, an analytical cross-sectional study involving 150 normal pregnant women in labor at term (>37 weeks of gestation) at a tertiary center in the Bundelkhand region of India was published just a few months ago. Maternal and infant blood samples were obtained at the time of delivery. The results revealed a positive correlation between serum vitamin D levels in newborns and maternal vitamin D levels. This finding supports the idea that normal vitamin D status in pregnant women is necessary for the fetus. If the mother is deficient, the same condition occurs to the fetus [

58]. In other words, fetal and/or neonatal serum calcidiol levels are directly related to maternal calcidiol levels. Therefore, vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women could lead to decreased maternal calcium absorption and, consequently, decreased placental transfer.

5. Maternal Vitamin D Status and Fetal Growth Patterns

IUGR is defined as the inability of a fetus to achieve its genetic growth potential. This is caused by maternal, placental, fetal, or environmental factors. IUGR is commonly diagnosed by ultrasound during pregnancy or by a detection of fetal weight below the 10th percentile for sex and gestational age at birth (SGA). LBW is defined as a birth weight of less than 2,500 grams, regardless of gestational age [

59]. Numerous observational studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses have demonstrated an association between lower maternal vitamin D levels and adverse fetal growth outcomes, including LBW, shorter bone length, and SGA births (11, 20, 56, 60-65). However, other studies have found no influence of vitamin D status on fetal anthropometric parameters [

16,

18,

54,

66,

67,

68].

The biological basis of the association between maternal vitamin D status and fetal growth patterns remains unclear. Normal placental development requires implantation of the blastocyst. This process begins with the embryo attaching to the maternal endometrial epithelium. Then, the fetal trophoblast invades the maternal endometrium. This allows oxygen and nutrients to supply the fetus and waste products to be excreted. At the same time, it protects the fetus from maternal immune attack. Furthermore, the presence of VDR and CYP27B1 in placentas from early pregnancies suggests that vitamin D plays an important role in placental physiology. Maternal decidua and fetal trophoblasts, which are both components of the placenta (including the syncytiotrophoblast and the invasive extravillous trophoblast), express CYP27B1 and synthesize calcitriol. Coincident expression of VDR in the trophoblast and the decidua suggests that locally synthesized vitamin D could have an autocrine or paracrine function in the placenta. Ex vivo and in vitro analyses of trophoblast cells indicate that vitamin D plays a significant role in placental function. This includes the regulation of trophoblast differentiation and the invasion of the decidua and myometrium by invasive extravillous trophoblasts. Indeed, vitamin D appears to regulate genes responsible for trophoblast invasion and angiogenesis, both of which are essential for implantation and placental function and, consequently, fetal growth [

69]. In short, vitamin D deficiency could lead to abnormal placentation and cause significant pregnancy disorders such as spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction [

70].

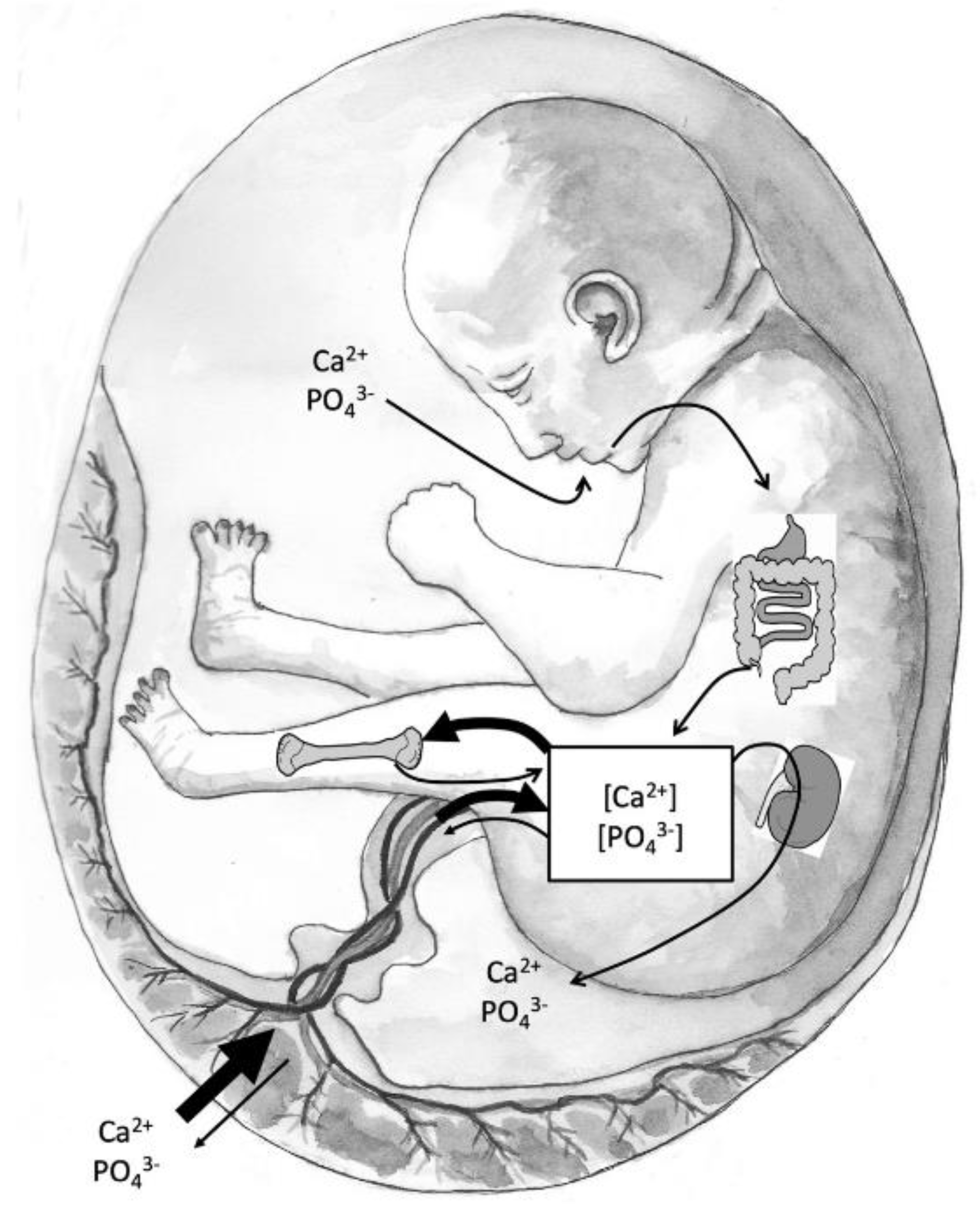

On the other hand, vitamin D appears to play an important role in the growth and mineralization of the fetal skeleton. Skeletal formation begins during the embryonic period, but the primary period of skeletal mineralization occurs in the third trimester [

37]. This period of fetal development is characterized by rapid growth, mineralization, and high serum mineral concentrations (calcium and phosphate). The placenta must supply the necessary minerals for adequate fetal skeletal mineralization through the active transport of calcium and phosphorus from the maternal circulation. Intrauterine skeletal mineralization is primarily determined by plasma ionic calcium concentration, which depends on placental calcium transfer and fetal calciotropic hormones, such as PTHrP, calcitriol, FGF23, calcitonin, and sex steroids. Active calcium transport across the placenta is regulated by the expression of plasma membrane calcium-dependent ATPases (PMCA1-4). Furthermore, PMCA3 gene expression predicts neonatal whole-body bone mineral content at birth. There is also experimental evidence that PMCA gene expression is mediated by calcitriol [

71]. In fact, serum calcium and phosphorus concentrations are higher in the fetus than in the mother to facilitate mineralization of the developing skeleton. In adults, this high mineral content would lead to serious consequences, such as soft tissue calcifications, coronary artery calcifications, and calciphylaxis.

Figure 2 shows the sources of minerals during fetal development. The main flow of calcium and phosphate occurs through the placenta and fetal circulation to the bone. The fetal kidneys filter blood with little active mineral reabsorption. The amniotic fluid, which is composed primarily of fetal urine, is swallowed and absorbed. However, the renal-amniotic-intestinal pathway plays a minor role in fetal mineral homeostasis because the placenta is the main supplier of minerals. Vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women is likely to be accompanied by maternal hypocalcemia. If placental calcium transfer is deficient, compensatory fetal hyperparathyroidism will occur because maternal PTH does not cross the placenta. This leads to calcium reabsorption from the fetal skeleton, resulting in decreased bone mineral content and potential fetal growth restriction. [

37].

We would like to highlight a series of recent studies that are methodologically rigorous despite their varied designs. We consider these studies worthy of mention because they provide novel scientific evidence in this field. The SCOPE (Screening for Pregnancy Endpoints) study was a large, international, prospective pregnancy cohort study of 1,786 women at 15 weeks of gestation. The study reported an inverse association between calcidiol concentrations greater than 30 ng/mL and uteroplacental dysfunction, as indicated by a composite outcome of SGA and preeclampsia. In other words, vitamin D status was associated with uteroplacental dysfunction, as indicated by preeclampsia and SGA birth [

72].

A recent experimental study using mouse models explored the underlying mechanism by which gestational vitamin D deficiency induces IUGR. The female mice were divided into vitamin D-deficient and control groups. The results showed that gestational vitamin D deficiency induces IUGR (the fetal weight and length were lower in the deficient mice than in the controls) and inhibits placental development (the placental weight and diameter were lower in the deficient mice than in the controls). Additionally, gestational vitamin D deficiency impaired placental function, as evidenced by severe damage to the placental labyrinth layer and reduced internal space of the placental vessels in vitamin D-deficient mice. Furthermore, gestational vitamin D deficiency caused placental inflammation, as demonstrated by higher levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including placental TNF-α, MCP-1, and KC mRNA, in maternal sera of vitamin D deficient subjects compared to controls. Thus, these findings provide experimental evidence that gestational vitamin D deficiency causes placental insufficiency and IUGR, possibly by inducing placental inflammation. Therefore, adequate vitamin D supplementation (cholecalciferol) could be a potential strategy to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes, particularly IUGR, in deficient pregnant women [

26].

A prospective cohort study within the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Fetal Growth Studies–Singletons, was conducted in 321 mothers-offspring pairs recruited fron 12 clinics across the US. Their aim was to analyze the association between longitudinal maternal vitamin D status during pregnancy and neonatal anthropometry a birth. Maternal concentrations of vitamin D were measured at 0–14, 15–26, 23–31, and 33–39 gestational week and neonatal anthropometric measures were collected after delivery. The association of maternal vitamin D status with neonatal anthropometry varied throughout pregnancy. Vitamin D deficiency at 10–14 gestational week was associated with lower birthweight and shorter length, at 23–31 gestational week was associated with shorter length and lower sum of skinfolds, and at 33–39 gestational week, with shorter length. If these findings are confirmed, it would be important to monitor vitamin D status during pregnancy, since vitamin D deficiency both at the beginning and end of pregnancy could affect fetal growth [

73].

The GraviD study is a prospective cohort study conducted in the Västra Götaland region of Sweden. The study included a total of 1,810 mother-child pairs and aimed to examine the association between vitamin D status trajectories during pregnancy and newborn size at birth. Maternal vitamin D status was measured from samples of each participant at two time points: first (8-12 gestational weeks) and third trimester (32-35 gestational weeks) of pregnancy. Lower vitamin D status in early pregnancy was associated with pregnancy loss. Additionally, higher vitamin D status in late pregnancy, but not early pregnancy, was associated with a lower probability of having a baby that is SGA or has LBW. In other words, vitamin D status in the third trimester of pregnancy, rather than the first, appears to be a good predictor of fetal growth restriction [

74].

A recent retrospective, population-based study was conducted at the Maternal and Child Health and Family Planning Service Center in Tumen City, Yanbian, China. The study included 510 healthy mother-newborn pairs. The study aimed to evaluate the correlation between maternal vitamin D deficiency and neonatal weight, as well as the predictive value of maternal vitamin D status in relation to fetal weight. Maternal vitamin D levels were measured at 16–20 weeks of gestation, and mothers with vitamin D deficiency were at an increased risk of delivering a baby that was SGA or had LBW. In other words, mid-pregnancy vitamin D levels could predict neonatal birth weight. Furthermore, receiver operating characteristic curve analysis indicated that vitamin D status could predict neonatal birth weight [

75].

In the large, population-based, prospective cohort study integrated into the Generation R Study, maternal blood samples were collected in the second trimester of pregnancy (median gestational age: 20.3 weeks) and fetal growth measurements were performed in the second and third trimesters (median gestational ages: 20.5 and 30.3 weeks, respectively) using ultrasound procedures. The results showed an association between maternal vitamin D concentrations during pregnancy and longitudinally measured fetal head circumference, length, and weight. These findings suggest that lower maternal vitamin D concentrations in the second trimester are associated with restricted fetal head, length, and weight growth in the third trimester, as well as an increased risk of LBW and/or SGA at birth. Obviously, these results support the use of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy to normalize vitamin D status [

11].

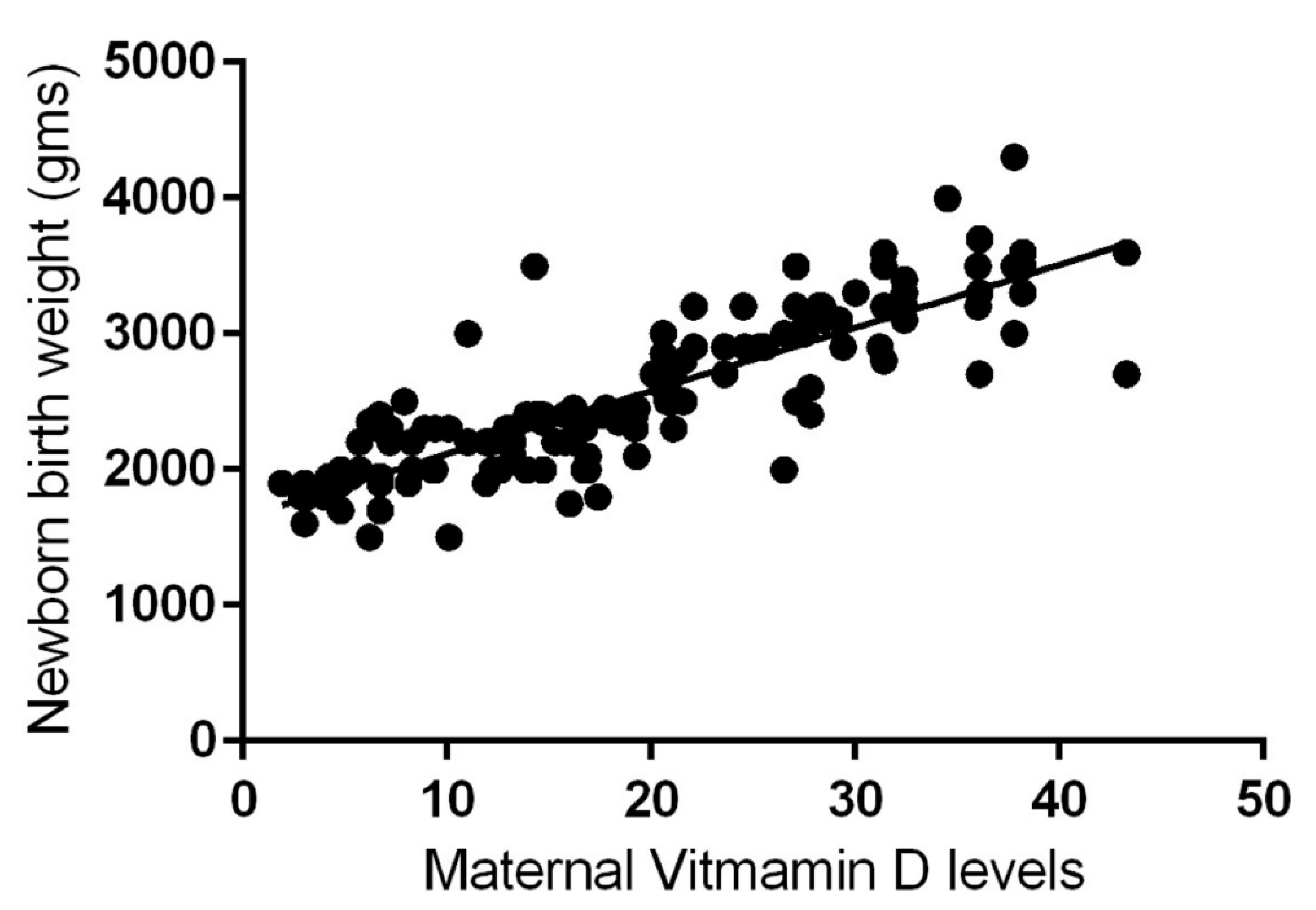

The results of the aforementioned analytical cross-sectional study, which was carried out with 150 mothers and their newborns in the Bundelkhand region of India, are remarkable. Newborns of mothers with maternal vitamin D deficiency were 96% more likely to have LBW (i.e., <2500 g) than newborns of mothers with sufficient vitamin D levels. (i.e., >2500 g). In short, a significant, strong, positive, direct correlation (Pearson's r = 0.83) was observed between maternal vitamin D status during pregnancy and birth weight (

Figure 3) [

58].

A secondary analysis using data and samples from a multisite prospective cohort study of nulliparous pregnant females conducted in the United States (Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study) was published just a few months ago. Vitamin D status was measured in 351 participants at 6–13 weeks and 16–21 weeks of gestation. Fetal growth was measured by ultrasound at 16–21 and 22–29 weeks of gestation, and neonatal anthropometric measurements were performed at birth. The results showed that first-trimester maternal vitamin D status was positively associated with fetal linear growth but not with growth patterns for weight or head circumference. However, second-trimester vitamin D status was not associated with fetal growth patterns. The authors suggest that vitamin D supplementation should begin in the preconceptional period and that future research should investigate the mechanisms by which vitamin D contributes to fetal growth [

28].

6. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation During Pregnancy on Birth Size

Given the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women and the potential consequences for maternal and fetal health, relying exclusively on sun exposure and vitamin D enriched foods to achieve adequate levels seems risky [

76]. Several studies have evaluated the benefits of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy. While vitamin D (cholecalciferol) supplementation may increase calcidiol levels in both mother and infant, it is unclear if it protects against intrauterine growth restriction due to study design heterogeneity, intervention type, and observational study design [

25,

53,

56,

61,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81]. Additionally, there is no universal agreement on the appropriate vitamin D dosage during pregnancy. For instance, the World Health Organization recommends only 200 IU per day for pregnant women diagnosed with vitamin D deficiency. The UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommends 400 IU/day [

82]. The Food and Nutrition Board at the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies recommends 600 IU per day [

83], while the U.S. Endocrine Society recommends 1,500–2,000 IU per day [

9]. However, historical vitamin D supplementation trials suggest that 400 IU/day of vitamin D during pregnancy is grossly inadequate. Studies have shown that supplementation of up to 4,000 IU per day is more effective in reducing deficiency and improving serum calcidiol levels in pregnant women and their neonates than 2,000 IU or 400 IU per day, with no adverse maternal or fetal effects [

8,

80,

84,

85,

86].

Inconsistent findings across studies could be the result from residual confounding factors. Maternal vitamin D status depends on diet, nutrition, vitamin supplementation, physical activity, socioeconomic status, and race, all of which can influence pregnancy outcomes independently. These contrasting results have led several researchers to conduct meta-analyses in recent years to clarify the potential effect of vitamin D supplementation on birth weight. However, we would like to highlight two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that were not included in the systematic reviews and meta-analyses. We will discuss the results of these trials later. One such trial, which was recently opened, was conducted with 164 pairs of pregnant mothers and their infants at King Fahad Medical City in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The pregnant women in the study were randomized into two groups according to vitamin D supplementation: 400 IU (Group 1) versus 4,000 IU (Group 2). The number of IUGRs was lower in Group 2 (9.6%) than in Group 1 (22.2%) [

87]. Another randomized controlled trial with 162 mother-infant pairs at a tertiary perinatal care center in Saudi Arabia determined the efficacy and safety of prenatal vitamin D supplementation at 2,000 and 4,000 IU/day versus 400 IU/day. The results showed that mean serum calcidiol concentrations at delivery and in cord blood were significantly higher in the 2,000 and 4,000 IU groups than in the 400 IU/d group, with the highest concentrations observed in the 4,000 IU/d group. There were no adverse events related to vitamin D supplementation. In short, vitamin D supplementation of 2,000 and 4,000 IU per day was safe during pregnancy. The 4,000 IU per day dose was the most effective in optimizing serum calcidiol concentrations in mothers and their infants [

84].

A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs showed that prenatal vitamin D supplementation was associated with increased maternal and cord serum calcidiol concentrations, increased mean birth weight, and a reduced risk of SGA. However, greater effects were not consistently found with higher effective doses. This is likely due to poor adherence to supplementation regimens or a lower vitamin D content than indicated on the supplement label. These factors reflect the low quality of many of the included trials [

88]. Another systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs found that vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy is safe and effective. It does not increase the risk of fetal or neonatal mortality or congenital abnormality. It reduces the risk of SGA and improves neonatal calcium levels, skinfold thickness, and fetal growth (greater weight and height at birth). Late supplementation (initiation at ≥20 weeks' gestation) improved birth weight, whereas early supplementation (initiation at <20 weeks' gestation) did not. However, the heterogeneity of the included RCTs requires that this result be interpreted with caution since there were differences in the characteristics of the studied population, ethnicity, geographical conditions, and the timing and dose of vitamin D administered during pregnancy [

89]. A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs assessed the effects of oral vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on neonatal anthropometric measurements and the incidence of LBW or SGA. Daily doses ranged from 200 to 4,000 IU, and single high-intensity intermittent interventions ranged from 35,000 to 600,000 IU. Compared to control groups, the risk of SGA was lower in the intervention groups. Most of the included studies demonstrated the benefits of supplementation at or above the recommended dose of 600 IU per day by the Institute of Medicine [

83]. However, the meta-regression analysis did not reveal a dose-dependent effect of vitamin D on birth size, likely because of the limited number of studies included (only thirteen RCTs). In short, the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis confirm that vitamin D is essential for fetal growth and development and has well-established effects on birth size. Further research is needed to evaluate the dose-dependent effects of vitamin D alone or in combination with other micronutrients [

90]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently recommended, based on strong evidence, pharmacological vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy of at least 2,000 to 4,000 IU per day to achieve blood vitamin D levels of at least 30 ng/mL, preferably 40 ng/mL. Additionally, the FDA established 4,000 IU/day as the tolerable upper limit for pregnant women [

91].

A quasi-experimental clinical trial was recently published by the Duhok Maternity Hospital in Iraqi Kurdistan. The objective was to investigate the effectiveness of combining vitamin D supplements with calcium compared to the use of vitamin D supplements alone on neonatal anthropometry. Pregnant women from 20 weeks of gestation until delivery were divided into two groups. One group received a daily dose of 1,000 IU of vitamin D (n = 41), and the other received a daily dose of 1,000 IU of vitamin D and 500 mg of calcium (n = 36). Compared with the vitamin D group, newborns in the vitamin D + calcium group were less likely to have low birth weight (5.71% vs. 31.58%; P = 0.0066) or short birth length (5.71% vs. 44.74%; P = 0.0007). Thus, this study provides evidence supporting the positive effects of daily co-supplementation of vitamin D and calcium during the third trimester of pregnancy on neonatal anthropometry [

92].

Finally, it should be noted that vitamin D status can affect several aspects of health other than metabolism, such as its anti-inflammatory and immuneregulatory action. A clinical trial was designed to evaluate the efficacy of two doses of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on maternal and cord blood vitamin D status, inflammatory biomarkers, and neonatal size. A total of 84 pregnant women with a gestational age of less than 12 weeks were randomly assigned to one of two groups that received different doses of vitamin D supplementation: 1,000 IU or 2,000 IU per day. Maternal biochemical assessments (calcidiol, IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α) were performed at the beginning of the study and at 34 weeks of gestation. After delivery, the same biochemical assessments and birth size were evaluated in the newborn. The results concluded that 2,000 IU/day of vitamin D supplementation from the first trimester of pregnancy is more effective than 1,000 IU/day in improving the vitamin D status of pregnant women and decreasing inflammatory biomarkers (TNF-α in the mother and IL-6 in the cord blood). Furthermore, 2,000 IU/day supplementation improved neonatal birth size (weight, length, and head circumference) compared to 1,000 IU/day [

93].

7. Conclusions

Vitamin D deficiency is a significant public health concern with numerous health consequences. Pregnant women and newborns are considered to be at high risk for vitamin D deficiency. During pregnancy, vitamin D plays a crucial role in placental function, calcium homeostasis, and fetal bone mineralization, all of which are essential for fetal development and growth.

This review demonstrates the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women and newborns worldwide, even in sunny countries. Furthermore, most studies indicate that fetal and/or neonatal vitamin D levels are directly related to maternal levels. Therefore, vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women may result in decreased calcium absorption and transfer to the placenta, as well as uteroplacental dysfunction. Monitoring vitamin D status in pregnant women and newborns should certainly be a global priority.

Several studies have shown an association between low maternal vitamin D levels and adverse fetal growth outcomes, such as IUGR. The association between maternal vitamin D status and neonatal anthropometry has been documented throughout pregnancy, though discrepancies have arisen due to heterogeneity in study design. Therefore, monitoring vitamin D status during pregnancy is important, as deficiency at the beginning and end of pregnancy could affect fetal growth.

The biological basis of the association between maternal vitamin D status and fetal growth patterns is unclear. However, several concurrent pathophysiological mechanisms have been suggested and could explain this association. For instance, the presence of VDR and CYP27B1 in placentas from early pregnancies suggests that vitamin D plays a significant role in implantation and placental function. Vitamin D deficiency could lead to abnormal placentation and cause pregnancy complications such as spontaneous abortion or intrauterine growth restriction. Conversely, the primary maternal-fetal flow of calcium and phosphate occurs through the placenta and fetal circulation to the bone. Vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women is likely accompanied by maternal hypocalcemia. If placental calcium transfer is deficient, compensatory fetal hyperparathyroidism leads to calcium reabsorption from the fetal skeleton, resulting in a decrease in bone mineral content and potentially causing intrauterine growth restriction. Additionally, experimental evidence suggests that gestational vitamin D deficiency causes placental insufficiency, uteroplacental dysfunction, and IUGR by inducing placental inflammation. Given its anti-inflammatory properties, adequate vitamin D (cholecalciferol) supplementation could potentially address the aforementioned pathophysiological mechanisms and prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes, particularly IUGR, in vitamin D-deficient pregnant women. Most authors suggest that vitamin D supplementation should begin during the preconception period and that future research should investigate the mechanisms by which vitamin D contributes to fetal growth.

Though results from intervention are inconclusive owing to various reasons already mentioned, there is substantial evidence suggesting that maternal vitamin D supplementation (cholecalciferol) may improve maternal and neonatal outcomes. In other words, although vitamin D is essential for fetal development and growth, there is insufficient evidence to make recommendations for the optimal amount of prenatal vitamin D supplementation to reduce the risk of IUGR. An immediate priority should be a coordinated effort to conduct large-scale randomized controlled trials investigating the dose-dependent effect of prenatal vitamin D supplementation on fetal growth patterns.

Compliance with ethical statements.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article (none declared).

Authors' contributions:

TDT and FGV participated in study design, data collection and analysis. Both authors participated in manuscript preparation and approved its final version.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article (none declared).

Abbreviation

25(OH) D: 25-hydroxicholecalciferol.

1,25 (OH)2D: 1,25-hydroxicholecalciferol

CYP27B1: enzyme 1α-hydroxylase CYP2R1: enzyme cholecalciferol-25-hydroxylase

CYP24A1: enzyme 24-hydroxylase

FDA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

FGF23: fibroblast growth factor

IFN-γ: interferon-gamma

IL: interleukin

LBW: low birth weight

PMCA 1-4: plasma membrane calcium-dependent ATPases

PTH; parathyroid hormone

PTH-rP: PTH-related peptide

RCTs: randomized controlled trials

SGA: small for gestational age

TGF: β transforming growth factor beta

TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alfa

VDBP: vitamin D binding protein

VDR: vitamin D receptor

References

- Wacker M, Holick MF. Sunlight and Vitamin D: A global perspective for health. Dermatoendocrinol. 2013, 5, 51–108.

- Hossein-Nezhad, A.; Holick, M.F. Vitamin D for health: A global perspective. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013, 88, 720–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotunde, O.F.; Laliberte, A.; Weiler, H.A. Maternal risk factors and newborn infant vitamin D status: A scoping literature review. Nutr. Res. 2019, 63, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios C, Gonzalez L. Is vitamin D deficiency a major global public health problem? . J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 144 Pt, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, K.D.; Sheehy, T.; O’Neill, C.M. Is vitamin D deficiency a public health concern for low middle income countries? A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Tuo, L.; Zhai, Q.; Cui, J.; Chen, D.; Xu, D. Relationship between Maternal Vitamin D Levels and Adverse Outcomes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth DE, Abrams SA, Aloia J, Bergeron G, Bourassa MW, Brown KH, Calvo MS, Cashman KD, Combs G, De-Regil LM, Jefferds ME, Jones KS, Kapner H, Martineau AR, Neufeld LM, Schleicher RL, Thacher TD, Whiting SJ. Global prevalence and disease burden of vitamin D deficiency: A roadmap for action in low- and middle-income countries. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2018, 1430, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M. Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention of Vitamin D Deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Med. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S.; Hewison, M. Extrarenal expression of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-hydroxylase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 523, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliku K, Vinkhuyzen A, Blanken LM, McGrath JJ, Eyles DW, Burne TH, Hofman A, Tiemeier H, Steegers EA, Gaillard R, Jaddoe VW. Maternal vitamin D concentrations during pregnancy, feal growth patterns and risk of adverse birth outcome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1514–1522. [CrossRef]

- Fiscaletti M, Stewart P, Munns CF. The importance of vitamin D in maternal and child health: a global perspective. Public Health Rev. 2017, 38, 19. [CrossRef]

- Sarma D, Saikia UK, Das DV. Fetal skeletal size and growth are relevant biometric markers in vitamin D deficient mothers: a North East India prospective cohort study, Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 22, 212–216. [CrossRef]

- Tamblyn, J.A.; Hewison, M.; Wagner, C.L.; Bulmer, J.N.; Kilby, M.D. Immunological role of vitamin D at the maternal-fetal interface. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 224, R107–R121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, R.; Morton, S.M.B.; Camargo, C.A.; Grant, C.C. Global summary of maternal and newborn vitamin D status—A systematic review. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pligt, P.; Willcox, J.; Szymlek-Gay, E.A.; Murray, E.; Worsley, A.; Daly, R.M. Associations of maternal vitamin D deficiency with pregnancy and neonatal complications in developing countries: A systematic review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrein K, Scherkl M, Hoffmann M, Neuwersch-Sommeregger S, Köstenberger M, Tmava Berisha A, Martucci G, Pilz S, Malle O. Vitamin D deficiency 2.0: an update on the current status worldwide. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1498–1513. [CrossRef]

- Christoph P, Challande P, Raio L, Surbek D. High prevalence of severe vitamin D deficiency during the first trimester in pregnant women in Switzerland and its potential contributions to adverse outcomes in the pregnancy. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2020, 150, w20238.

- Wei, S. , Qi H. , Luo Z., Fraser W. Maternal vitamin D status and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013, 26, 889–99. [Google Scholar]

- Aghajafari, F. , Nagulesapillai T. , Ronksley P., Tough S., O’Beirne M. & Rabi D. Association between maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. British Medical Journal 2013, 346, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, C.L.; Gernand, A.D.; Roth, D.E.; Bodnar, L.M. Maternal vitamin D status and infant anthropometry in a US multicentre cohort study. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2015, 42, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Ortiz, A.; Avila, E.; Duland-Carbajal, M.; Díaz, L. Regulation of calcitriol byosinthesis and activity: Focus on gestational vitamin D deficiency and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Nutrients 2015, 7, 443–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Yan, X.T.; Bai, C.M.; Zhang, X.V.; Hui, L.Y.; Yu, X.W. Decreased serum vitamin D levels in early spontaneous pregnancy loss. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1004–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Kovilam, O.; Agrawal, D.K. Vitamin D and its impact on maternal-fetal outcomes in pregnancy: A critical review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, C.; Kostiuk, L.K.; Peña-Rosas, J.P. Vitamin D supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 7, CD008873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen GD, Pang TT, Li PS, Zhou ZX, Lin DX, Fan DZ, Guo XL, Liu ZP. Early pregnancy vitamin D and the risk of adverse maternal and infant outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 465. [CrossRef]

- Arshad R, Sameen A, Murtaza MA, Sharif HR, Iahtisham-Ul-Haq, Dawood S, Ahmed Z, Nemat A, Manzoor MF. Impact of vitamin D on maternal and fetal health: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 3230–3240.

- Beck C, Blue NR, Silver RM, Na M, Grobman WA, Steller J, Parry S, Scifres C, Gernand AD. Maternal vitamin D status, fetal growth patterns, and adverse pregnancy outcomes in a multisite prospective pregnancy cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 121, 376–384.

- Palermo, N.E.; Holick, M.F. Vitamin D, bone health, and other health benefits in pediatric patients. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 7, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hii, C.S.; Ferrante, A. The Non-Genomic Actions of Vitamin D. Nutrients 2016, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, R.; Misra, M. Extra-Skeletal Effects of Vitamin D. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, J.; Machado, V.; Proença, L.; Delgado, A.S.; Mendes, J.J. Vitamin D deficiency and oral health: A comprehensive review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmijewski, M.A. Nongenomic Activities of Vitamin D. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, C.S. Maternal mineral and bone metabolism during pregnancy, lactation, and post-weaning recovery. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 449–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Shin, S.; Han, S.N. Multifaceted Roles of Vitamin D for Diabetes: From Immunomodulatory Functions to Metabolic Regulations. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, CS. Maternal Mineral and Bone Metabolism During Pregnancy, Lactation, and Post-Weaning Recovery. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 449–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds CS, Karsenty G, Karaplis AC, Kovacs CS. Parathyroid hormone regulates fetal-placental mineral homeostasis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 594–605. [CrossRef]

- Ryan BA, Kovacs CS. Calciotropic and phosphotropic hormones in fetal and neonatal bone development. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 25, 101062. [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D.; Schwartz, J. Vitamin D binding protein, total and free vitamin D levels in different physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyola-Martinez, N.; Diaz, L.; Avila, E.; Halhali, A.; Larrea, F.; Barrera, D. Calcitriol downregulates TNF-alpha and IL-6 expression in cultured placental cells from preeclamptic women. Cytokine 2013, 61, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyprian, F.; Lefkou, E.; Varoudi, K.; Girardi, G. Immunomodulatory Effects of Vitamin D in Pregnancy and Beyond. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, Y.; Daich, J.; Soliman, I.; Brathwaite, E.; Shoenfeld, Y. Vitamin D and autoimmunity. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 45, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogire RM, Mutua A, Kimita W, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e134–142.

- Li H, Ma J, Huang R, Wen Y, Liu G, Xuan M, Yang L, Yang J, Song L. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the pregnant women: an observational study in Shanghai, China. Arch. Public. Health. 2020, 78, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravinder SS, Padmavathi R, Maheshkumar K, Mohankumar M, Maruthy KN, Sankar S, Balakrishnan K. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among South Indian pregnant women. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2022. 11, 2884–2889. [CrossRef]

- Amelia CZ, Gwan CH, Qi TS, Seng JTC (2024) Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in early pregnancies– a Singapore study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300063. [CrossRef]

- Octavius GS, Daleni VA, Angeline G, Virliani C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among Indonesian pregnant women: a public health emergency. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2023, 3, 100189.

- Karras, S.N.; Shah, I.; Petroczi, A.; Goulis, D.G.; Bili, H.; Papadopoulou, F.; Harizopoulou, V.; Tarlatzis, B.C.; Naughton, D.P. An observational study reveals that neonatal vitamin D is primarily determined by maternal contributions: Implications of a new assay on the roles of vitamin D forms. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Goel, P.; Chawla, D.; Huria, A.; Arya, A. Vitamin D Status in Mothers and Their Newborns and Its Association with Pregnancy Outcomes: Experience from a Tertiary Care Center in Northern India. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India 2018, 68, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmeraldo, C.U.; Martins, M.E.P.; Maia, E.R.; Leite, J.L.A.; Ramos, J.L.S.; Gonçalves, J., Jr.; Neta, C.M.; Suano-Souza, F.I.; Sarni, R.O. Vitamin D in Term Newborns: Relation with Maternal Concentrations and Birth Weight. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 75, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafarzadeh, M.; Shakarami, A.; Tarhani, F.; Yari, F. Evaluation of the prevalence of Vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women and its correlation with neonatal Vitamin D levels. Clin. Nutr. Open Sci. 2021, 36, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, S.; Afaq, S.; Fazid, S.; Khattak, M.I.; Yousafzai, Y.M.; Habib, S.H.; Lowe, N.; Ul-Haq, Z. Correlation between maternal and neonatal blood Vitamin D level: Study from Pakistan. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsedendamba, N.; Zagd, G.; Radnaa, O.; Baatar, N.; Nemekhee, O. Correlation Between Maternal-Nonatal Vitamin D Status and it’s Related to Supplementation in Mongolian Pregnant Women. Int. J. Innov. Res. Med. Sci. 2022, 7, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu C-C, Huang J-P. Potential benefits of vitamin D supplementation on pregnancy. J. Formos Med. Assoc. 2023, 122, 557–563. [CrossRef]

- Stoica, A.B.; Marginean, C. The Impact of Vitamin D Deficiency on Infants’ Health. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal S, Bansal U, Rathoria E, Rathoria R, Ahuja R, Agarwa A. Association Between Neonatal and Maternal Vitamin D Levels at Birth. Cureus 2024, 16, e72261.

- Kokkinari, A.; Dagla, M.; Antoniou, E.; Lykeridou, A.; Kyrkou, G.; Bagianos, K.; Iatrakis, G. The Correlation between Maternal and Neonatal Vit D (25(OH)D) Levels in Greece: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, R.E.; Toader, D.O.; Gheoca Mutu, D.E.; Dogaru, I.A.; Răducu, L.; Tomescu, L.C.; Moleriu, L.C.; Bordianu, A.; Petre, I.; Stănculescu, R. Consequences of Maternal Vitamin D Deficiency on Newborn Health. Life 2024, 14, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh M, Shobhane H, Tiwari K, Agarwal S. To Study the Correlation of Maternal Serum Vitamin D Levels and Infant Serum Vitamin D Levels With Infant Birth Weight: A Single-Centre Experience From the Bundelkhand Region, India. Cureus 2024, 16, e68696. [CrossRef]

- Clayton PE, Cianfarani S, Czernichow P, Johannsson G, Rapaport R, Rogol AD. Consensus statement: management of the child born small for gestational age through to adulthood: a consensus statement of the international societies of pediatric endocrinology and the growth hormone research society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 92, 804–810.

- Leffelaar ER, Vrijkotte TGM, van Eijsden M. Maternal early pregnancy vitamin D status in relation to fetal and neonatal growth: results of the multi-ethnic Amsterdam Born Children and their Development cohort Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 108–117. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, F.R.; Pasupuleti, V.; Mezones-Holguin, E.; Benites-Zapata, V.A.; Thota, P.; Deshpande, A.; Hernandez, A.V. Effect of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on maternal and neonatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tous M, Villalobos M, Iglesias-Vázquez L, Fernández-Barrés S, Arija V. Vitamin D status during pregnancy and offspring outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 36–53.

- Deepa R, Schayck OCPV and Babu GR. Low levels of Vitamin D during pregnancy associated with gestational diabetes mellitus and low birth weight: results from the MAASTHI birth cohort. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1352617.

- M. -C. Chien, C.-Y. Huang, J.-H. Wang, C.-L. Shih, P. Wu, Effects of vitamin D in pregnancy on maternal and offspring health-related outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic review and meta-analyses, Nutr. Diabetes 2024, 14, 35.

- You Z, Mei H, Zhang Y, Song D, Zhang Y and Liu C (2024) The effect of vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy on adverse birth outcomes in neonates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1399615.

- Monier I, Baptiste A, Tsatsaris V, Senat MV, Jani J, Jouannic JM, Winer N, Elie C, Souberbielle JC, Zeitlin J, Benachi A. First Trimester Maternal Vitamin D Status and Risks of Preterm Birth and Small-For-Gestational Age. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 3042. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castillo ÍM, Rivero-Blanco T, León-Ríos XA, Expósito-Ruiz M, López-Criado MS, Aguilar-Cordero MJ. Associations of Vitamin D Deficiency, Parathyroid hormone, Calcium, and Phosphorus with Perinatal Adverse Outcomes. A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 3279. [CrossRef]

- Marçal VMG, Sousa FLP, Daher S, Grohmann RM, Peixoto AB, Araujo Júnior E, Nardozza LMM. The Assessment of Vitamin D Levels in Pregnant Women is not Associated to Fetal Growth Restriction: A Cross Sectional Study. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2021, 43, 743–748. [CrossRef]

- Chan SY, Susarla R, Canovas D, et al. Vitamin D promotes human extravillous trophoblast invasion in vitro. Placenta 2015, 36, 403–409. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly A, Tamblyn JA, Finn-Sell S, Chan SY, Westwood M, Gupta J, Kilby MD, Gross SR, Hewison M. Vitamin D, the placenta and early pregnancy: effects on trophoblast function. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 236, R93–R103. [CrossRef]

- Mansur, J.L.; Oliveri, B.; Giacoia, E.; Fusaro, D.; Costanzo, P.R. Vitamin D: Before, during and after Pregnancy: Effect on Neonates and Children. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely ME, Zhang JY, Kinsella M, Khashan AS, Kenny LC. Vitamin D status is associated with uteroplacental dysfunction indicated by pre-eclampsia and small-for-gestational-age birth in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Ireland with low vitamin D status. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 354–361.

- Francis EC, Hinkle SN, Song Y, Rawal S, Donnelly SR, Zhu Y, Chen L, Zhang C. Longitudinal Maternal Vitamin D Status during Pregnancy Is Associated with Neonatal Anthropometric Measures. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 1631.

- Bärebring L, Bullarbo M, Glantz A, Hulthén L, Ellis J, Jagner Å, Schoenmakers I, Winkvist A, Augustin H. Trajectory of vitamin D status during pregnancy in relation to neonatal birth size and fetal survival: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018, 18, 51. [CrossRef]

- Chen Q, Chu Y, Liu R, Lin Y. Predictive value of Vitamin D levels in pregnant women on gestational length and neonatal weight in China: a population-based retrospective study. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2024, 22, 102.

- Zhang X, Wang Y, Chen X, Zhang X. Associations between prenatal sunshine exposure and birth outcomes in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136472.

- Harvey, N.C.; Holroyd, C.; Ntani, G.; Javaid, K.; Cooper, P.; Moon, R.; Cole, Z.; Tinati, T.; Godfrey, K.; Dennison, E.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy: A systematic review. Health Technol. Assess. 2014, 18, 1–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Regil, L.M.; Palacios, C.; Lombardo, L.K.; Peña-Rosas, J.P. Vitamin D supplementation for women during pregnancy. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2016, 134, 274–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo S, McDermid JM, Al-Nimr RI, Hakeem R, Moreschi JM, Pari-Keener M, Stahnke B, Papoutsakis C, Handu D, Cheng FW. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: an evidence analysis center systematic review and meta-analysis, J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 898–924.

- Nausheen S, Habib A, Bhura M, Rizvi A, Shaheen F, Begum K, Iqbal J, Ariff S, Shaikh L, Raza SS, Soofi SB. Impact evaluation of the efficacy of different doses of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on pregnancy and birth outcomes: a randomised, controlled, dose comparison trial in Pakistan. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2021, 4, 425–434. [CrossRef]

- Irwinda R, Hiksas R, Lokeswara AW, Wibowo N. Vitamin D supplementation higher than 2000 IU/day compared to lower dose on maternal-fetal outcome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Womens Health (Lond). 2022, 18, 17455057221111066. [CrossRef]

- Hynes C, Jesurasa A, Evans P, Mitchell C. Vitamin D supplementation for women before and during pregnancy: an update of the guidelines, evidence, and role of GPs and practice nurses. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 67, 423–424.

- Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, 53–58.

- Dawodu, A.; Saadi, H.F.; Bekdache, G.; Javed, Y.; Altaye, M.; Hollis, B.W. Randomized controlled trial (RCT) of vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy in a population with endemic vitamin D deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 2337–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. A call to action: Pregnant women indeed require vitamin D supplementation for better health outcomes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litonjua, A.A.; Carey, V.J.; Laranjo, N.; Stubbs, B.J.; Mirzakhani, H.; O’Connor, G.T.; Sandel, M.; Beigelman, A.; Bacharier, L.B.; Zeiger, R.S.; et al. Six-year follow-up of a trial of antenatal vitamin D for asthma reduction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali AM, Alobaid A, Malhis TN, et al. Effect of vitamin D3 supplementation in pregnancy on risk of pre-eclampsia -Randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 557–563. [CrossRef]

- Roth DE, Leung M, Mesfin E, Qamar H, Watterworth J, Papp E. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: state of the evidence from a systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ. 2017, 359, j5237.

- Bi WG, Nuyt AM, Weiler H, Leduc L, Santamaria C, Wei SQ. Association Between Vitamin D Supplementation During Pregnancy and Offspring Growth, Morbidity, and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 635–645.

- Maugeri A, Barchitta M, Blanco I, Agodi A. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation During Pregnancy on Birth Size: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2019, 11, 442. [CrossRef]

- Adams JB, Kirby JK, Sorensen JC, Pollard EL, Audhya T. Evidence based recommendations for an optimal prenatal supplement for women in the US: vitamins and related nutrients. Matern. Health Neonatol. Perinatol. 2022, 8, 4.

- Abdulah DM, Hasan JN, Hasan SB. Effectiveness of Vitamin D supplementation in combination with calcium on risk of maternal and neonatal outcomes: A quasi-experimental clinical. Tzu. Chi. Med. J. 2023, 36, 175–187. [CrossRef]

- Motamed S, Nikooyeh B, Kashanian M, Hollis BW, Neyestani TR. Efficacy of two different doses of oral vitamin D supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers and maternal and neonatal outcomes. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12867. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).